Abstract

The study aims to investigate the behavioral and neural responses of a face transplant patient (FTP) to his pre-operative and post-operative faces. For this purpose, a control group (N = 15) and a single FTP were presented images of their past face, present face, and other unfamiliar faces and asked to identify whether these faces belonged to them or not. During the task, electrophysiological and behavioral responses were recorded. The FTP exhibited higher N170 amplitudes for his past face compared to the control group, suggesting increased visual processing due to its distinctiveness. N250 latency was shorter for his past face, indicating a profoundly ingrained self-identity. P300 amplitudes to his present face were significantly higher, potentially reflecting cognitive adaptation to his transplanted identity. Behaviorally, the control group identified their past faces more quickly, whereas the FTP demonstrated delayed and less accurate recognition of both his past and present faces. This study presents the first ERP-based comparison of an FTP with a control group, highlighting the dynamic nature of self-face perception and neural plasticity. The findings suggest that self-face identity is a flexible process influenced by past experiences and adaptation mechanisms, offering important implications for rehabilitation and psychological support in face transplantation cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The face, a unique part of the body, conveys identity, expression, and cues about gender, age, and race. Humans have a specialized system for face processing. fMRI studies show that it activates a distributed network including the fusiform face area (FFA), lateral inferior occipital gyri, and posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS)1. Parvizi and his colleagues2 provided evidence for two fusiform regions involved in face perception using electrical stimulation, fMRI, and electrocorticography. Stimulation of electrodes in the right fusiform area during surgery impaired a patient’s recognition of real faces.

Perceptions of oneself and one’s own face have also been studied3,4,5,6 since a person’s face constitutes an important part of his/her identity, much like other distinctive features such as name, race, and place of birth. In a seminal study by Turk et al.7morphs of participants’ own and other faces were shown to a split-brain patient. Both hemispheres could recognize faces, but the left hemisphere was more responsive to self-like faces, while the right specialized in other-like faces. In contrast, a Wada test study8 (hemispheric anesthesia) showed that self-face recognition deteriorates when the right hemisphere is deactivated but remains intact when the left hemisphere is disrupted. Similarly, TMS studies9,10,11 have demonstrated that disrupting the right parietal regions impairs self-face recognition. Neuropsychological evidence from patients with right hemisphere damage who often exhibit deficits in self-face recognition12,13,14 also supports the dominant role of the right hemisphere in self-face processing. This suggests that the right hemisphere is specialized for self-face recognition, integrating visual, proprioceptive, and cognitive information.

fMRI studies on self-face perception5,9,15 show greater right hemisphere activation (inferior frontal gyrus, inferior parietal lobule), typically by comparing responses to one’s own face versus familiar or unfamiliar others. It has been reported that both hemispheres are involved during self-face recognition, but there is a right-sided advantage, especially in the frontal and parietal areas16. In a self-identity fMRI study17participants were shown their own face and body photographs, as well as photographs of faces and bodies of others. It was shown that the occipito-temporal cortex was activated more or less depending on whether the perceived stimulus was a face or a body. By analyzing studies that employ various techniques and paradigms, Molnar-Szakacs and Uddin18 have determined that the brain network responsible for self-face recognition includes the right inferior frontoparietal cortices and bilateral regions of the inferior occipito-temporal cortices, regardless of the familiarity of the other faces used as controls.

There are also some EEG and ERP studies focusing on self-face/other-face distinction19,20,21. The most prominent ERP components associated to face perception are P100, N170, N250, P300, N400 and VPP. The N170 is a well-known ERP potential showing larger amplitudes for faces and face-like objects (paredolia) than for objects and other visual stimuli. Possible generators of N170 are lateral, basal temporal and extra-striate cortices, occipital lateral fusiform gyrus (FFG), inferior temporal gyrus (ITG), posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS), and lingual gyrus (LG)22. The N250r and N400-like responses may be linked to the mechanisms of accessing and retrieving face-related information stored in long-term memory. These event-related potentials are possibly generated in the basal temporal cortex and the anterior fusiform gyrus (FFG)22. Estudillo23 found that the N250 response is larger for familiar faces than unfamiliar ones and is exceptionally responsive to self-face recognition, exhibiting a greater amplitude for one’s own face than other faces. The P300 component occurs when a subject is actively engaged in the task of detecting the targets and it may represent the transferred information to consciousness involving many different regions of the brain24. P300 amplitudes for subject’s own face are higher than that for the other stimuli25. Self-face processing appears to capture the attention, possibly due to top-down control mechanisms. Tacikowski and Nowicka21 also observed that self-name and self-face elicited larger P300 amplitudes and shorter latencies when compared to famous and unknown names/faces.

Geng and colleagues12 investigated how self-face is processed in comparison to other faces subliminally and supraliminally. When presented subliminally self-faces were detected faster than famous-other faces. When presented supraliminally, self-faces elicited enhanced N170. In a one-back repetition task, Keyes et al.20 also found that self-face elicited larger N170 in comparison to friend’s and stranger’s faces. In addition, they observed reduced P2 amplitude for self-faces compared to other faces. A general right hemispheric dominance was observed for all faces however, less lateralization was found for self-face processing. In another self-face study26 inverted faces elicited larger and delayed N170 responses, indicating disrupted holistic processing. They found no difference in reaction times and N170 amplitudes between self and familiar faces. On the other hand, self-faces elicited a reduced P200 amplitude and shorter latency, indicating that self-faces are processed with increased attention.

Doi’s27 study used machine learning-based multivariate ERP analysis to examine neural responses to original, aesthetically enhanced, and degraded self-faces. Participants accurately recognized their own faces and rated enhanced versions as more attractive and self-like, despite similar reaction times across conditions. Degraded self-faces elicited stronger N170 responses, while familiar faces evoked larger N250 responses. Kotlewska and colleagues28 examined self-face and self-name recognition in married women using five stimulus categories (self, former self, friend, famous, unknown) and analyzed posterior theta activity. They identified a self-related N2 at 300 ms and a later P3b, but no self-related N170. A significant self-face effect was found, not extending to self-names. Elevated P3b amplitudes suggest enhanced attention to self-referential stimuli, and theta-band activity may help distinguish self from others.

Face transplantation has been an interesting step in mankind’s advancements in recent years, particularly in the scope of one’s own face and another person’s face. As of 2024, a cumulative number of 50 face transplant surgeries have been conducted globally since the inaugural operation in 200529. As a research group, we have conducted multiple studies on face transplant patients, exploring different aspects of transplantation, including neural plasticity30,31perception and emotional expressions32,33,34,35,36 and face perception37. However, to our knowledge, only one neuroimaging study38 has compared the neural responses of a face transplant patient to previous and recent self-face. Azevedo and colleagues38 examined how self-identification changes following face transplantation, testing a patient at five time points before and after surgery. Using a self-recognition task with morphed faces, they found stronger identification with the pre-injury face, while recognizing the post-injury face as “self” required higher self-trait content. fMRI data showed that pre-injury faces more strongly activated self-referential brain regions such as the medial frontal cortex (MFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and precuneus. However, 20 months post-surgery, these regions began responding to the transplanted face instead, suggesting neural integration of the new facial identity. The findings indicate that self-face representation is flexible and can adapt to substantial physical changes over time.

Recent theoretical models in cognitive neuroscience emphasize the distinction between the minimal self and the narrative self as core components of self-identity39. While the minimal self is associated with immediate, bodily experiences and a sense of agency and ownership, the narrative self represents a temporally extended identity shaped by personal memories and social context. These two dimensions are increasingly supported by neuroimaging findings, particularly involving the default mode network (DMN) and salience-related networks40,41. Integrating these models provides a conceptual foundation for interpreting how drastic changes to one’s facial appearance—such as those resulting from face transplantation—may influence different layers of self-representation. Building on this framework, the present study examines how facial transplantation affects self-representation at neural and behavioral levels.

This study aimed to examine the behavioral and neural responses of a face transplant patient (FTP) to his faces before and after transplantation and to determine which face he adopts as his own-face. In this vein, using a face recognition task, we investigated behavioral and electrophysiological responses of both the FTP and a control group when they see their past and present faces, as well as other people’s faces. For electrophysiological examinations, we focused N170, N250, and P300 responses in the cortical areas those are known to be related to self-face perception. We focused on how accurately and quickly he distinguished his own face from other faces for behavioral examinations. We predicted that FTP would exhibit notable neural differences compared to controls, particularly in processing past and present faces. We also hypothesized that general weakness in self-recognition task performance compared to controls and that this weakness would be more pronounced in the past self-face and present self-face conditions.

Results

Behavioral findings

One-way repeated-measures ANOVAs were conducted on accuracy rates and reaction times to determine whether the participants in the control group differed in identifying different types of faces (self-past, self-present, other). The results revealed that face conditions did not significantly differentiate correct recognition rates (p =.099), but they did cause significant differences in reaction times (F(1, 28) = 3.58, p =.041, ηp2 = 0.20, see Fig. 1). According to Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons, whereas participants in the control group did not differ significantly in the speed of detecting their own present faces compared to the speed of detecting other faces (MD = −28.28, p =.158), or past faces (MD = −5.75, p = 1.000), they detected their past faces significantly faster than the other faces (MD = −22.53, p =.048).

Raincloud plots showing the reaction time distributions of the control group across different face conditions. The solid lines within the boxplots represent the median values of the respective distributions. Asterisks indicate the significance levels of the comparisons between conditions (* p <.05).

After revealing identification performances of the control group, we compared them to FTP’s using Crawford & Howell t tests42. As can be seen in the Fig. 2, control group identified their past and present faces more accurately than the FTP.Besides, they identified other faces significantly faster than the FTP (see Table 1; Fig. 2). The results of all comparisons between FTP and control group for identification accuracy and reaction times were shown in Table S1 in the Supplementary Material.

Raincloud plots showing the distributions of the behavioral measures in the conditions where significant differences were observed between the FTP and the control group. The specific conditions are provided in the titles above each plot. The distributions presented in the plots reflect the control group’s scores for the corresponding dependent variable that presented under each plot. The dashed lines labeled for the control group in each plot represent the median value of the respective distribution. The second dashed line indicates the value of the FTP participant, providing a visual reference for the position of the FTP value relative to the control group distribution. Asterisks in each raincloud indicate the significance level of the t-test comparing the FTP participant to the control group (*p <.05, ** p <.01).

Electrophysiological findings

The topographic map depicting the pattern of EEG recordings obtained during the presentation of different facial stimuli was shown in Fig. 3. The electrodes to be focused in the current study were determined based on these topographic maps and the electrodes examined in similar studies19,20,43. Accordingly, electrodes O1-O2, P7-P8, PO7-PO8 and TP9-TP10 for the N170 component, P7-P8, PO7-PO8 and TP9-TP10 for the N250 component, and finally P3-P4, P5-P6, CP3, CP4, AF3, AF4 for the P300 component were analyzed. The results of ERP analyses for all these components are shared separately.

N170 amplitudes

We examined the N170 amplitudes separately at electrodes in occipital (O1, O2), parietal (P7, P8), parieto-occipital (PO7, PO8) and temporo-parietal (TP9, TP10) regions. For all electrodes located in different regions, a 3 × 2 (face [past self-face, present self-face, other face] × hemisphere [right, left]) analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures was conducted to determine the effect of face and hemisphere on the amplitudes of the electrodes.

For electrodes located in the temporo-parietal regions (TP9-TP10), a significant main effect of hemisphere was found on N170 amplitudes (F(1, 28) = 7.59, p =.015, ηp2 = 0.35, see, Fig. 4). Accordingly, electrodes located in the right hemisphere produced higher amplitudes (M = −8.86, SD = 3.59) than in the left hemisphere (M = −7.52, SD = 3.74). However, no significant differences in N170 amplitudes were observed as a function of face (p =.809) or face*hemisphere interaction (p =.249).

Raincloud plots showing the N170 amplitude distributions in the left and right hemispheres at the electrodes located in temporo-parietal regions (TP9-TP10). The solid lines within the boxplots represent the median values of the respective distributions. Asterisks indicate the significance levels of the comparisons between conditions (* p <.05).

For occipital, parietal and parieto-occipital electrodes, the analysis revealed no significant differences in N170 amplitudes between the hemispheres (for occipital electrodes p =.930, for parietal electrodes p =.071, for parieto-occipital electrodes p =.111), or different face conditions (for occipital electrodes p =.220; for parietal electrodes p =.186, for parieto-occipital electrodes p =.608). The effect of face*hemisphere interaction also did not reach the significance level (for occipital electrodes p =.284, for parietal electrodes p =.700, for parieto-occipital electrodes p =.949).

After examining the N170 amplitude patterns in electrodes located in different brain regions of the control group, we compared these values with those of FTP (for all comparisons see Table S2 in Supplementary Material). Results of Crawford & Howell t tests42 revealed significant N170 amplitude differences between the control group and the FTP mostly in the past self-face condition (see, Table 2). Accordingly, amplitudes recorded in O1, P7, P8, PO7, PO8, TP9 and TP10 under the past self-face condition were higher in FTP than in the control group. For the P8 electrode, higher N170 amplitude was recorded in FTP compared to the control group also in the other face condition. The rainclouds showing the distribution of N170 amplitudes at the electrodes where significant differences were obtained between the control group and FTP and the traces of the relevant electrodes are shown in Fig. 5.

(a) Raincloud plots showing the distributions of N170 amplitudes recorded at electrodes where significant differences were found between the FTP and the control group across different face conditions. The relevant conditions and electrodes are indicated in the titles above each plot. The distributions represent the control group’s N170 amplitude values. Dashed lines labeled for the control group indicate the median of each distribution, while the second dashed line shows the FTP’s N170 amplitude value, providing a visual reference for the position of the FTP relative to the control group distribution. Asterisks indicate the significance level of the t-test comparing the FTP to the control group (* p <.05, ** p <.01) (b) Traces of the electrodes where significant differences in N170 amplitudes were observed between the FTP and the control group across different face conditions. The specific conditions and electrodes where these differences were found are indicated in the titles above each plot.

N170 latencies

In addition to amplitudes, we also examined the latency values of N170 responses in occipital (O1, O2), parietal (P7, P8), parieto-occipital (PO7, PO8) and temporo-parietal (TP9, TP10) regions. For all regions, to examine possible differences in N170 latencies in control group between the hemispheres and across face conditions, we conducted a 3 × 2 (face [past self-face, present self-face, other face] × hemisphere [right, left]) analyses of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures.

Raincloud plots showing the N170 latency distributions in the left and right hemispheres at the electrodes located in parietal (P7-P8), parieto-occipital (PO7-PO8), and temporo-parietal regions (TP9-TP10). The solid lines within the boxplots represent the median values of the respective distributions. Asterisks indicate the significance levels of the comparisons between conditions (* p <.05).

As depicted in Fig. 6, the electrodes located in parietal, parieto-occipital and temporo-parietal regions, significant hemisphere effect were found on N170 latencies (for parietal electrodes F(1, 28) = 4.74, p =.047, ηp2 = 0.25; for parieto-occipital electrodes F(1, 28) = 5.39, p =.036, ηp2 = 0.28; for temporo-parietal electrodes F(1, 28) = 6.75, p =.021, ηp2 = 0.32). Accordingly, significantly higher latencies were recorded in the left hemisphere compared to the right (for parietal electrodes Mleft = 180.27, SDleft = 16.52; Mright = 176,04, SDright = 14.42 for parieto-occipital electrodes Mleft = 179.64, SDleft = 16.32; Mright = 175.64, SDright = 14.25, for temporo-parietal electrodes Mleft = 185.29, SDleft = 13.05; Mright = 179,38, SDright = 14.27). However, no significant face effect (for parietal electrodes p =.342, for parieto-occipital electrodes p =.302, for temporo-parietal electrodes p =.411) or a face*hemisphere interaction (for parietal electrodes p =.122, for parieto-occipital electrodes p =.499, for temporo-parietal electrodes p =.157) were found on N170 latencies for these regions. As found in amplitude analyses, no main or interaction effects were found regarding N170 latencies recorded from occipital electrodes (pface = 0.219, phemisphere = 0.133, pface*hemisphere = 0.453).

To see possible differences in N170 latencies of healthy controls and FTP, we applied Crawford & Howell t tests42 However, no significant differences in N170 latency between healthy controls and patients were obtained for any electrode under different face conditions. The results of all comparisons between FTP and control group for N170 latencies were shown in Table S3 in the Supplementary Material.

N250 amplitudes

We examined the N250 amplitudes separately at electrodes in the parietal (P7, P8), parieto-occipital (PO7, PO8) and temporo-parietal (TP9, TP10) regions. For all regions, a 3 × 2 (face [past self-face, present self-face, other face] × hemisphere [right, left]) analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures was conducted to determine the effect of face and hemisphere on the amplitudes of the electrodes.

Raincloud plots showing the N250 amplitude distributions at the electrodes located in parietal (P7-P8), parieto-occipital (PO7-PO8), and temporo-parietal regions (TP9-TP10). The solid lines within the boxplots represent the median values of the respective distributions. Asterisks indicate the significance levels of the comparisons between conditions (* p <.05, ** p <.01).

For electrodes located in parietal and parieto-occipital regions, while no significant hemisphere effect (for parietal electrodes p =.469, for parieto-occipital electrodes p =.436) or face*hemisphere interaction effect (for parietal electrodes p =.504, for parieto-occipital electrodes p =.949) were found on N250 amplitudes, significant main effect of face was found (for parietal electrodes F(1, 28) = 5.07, p =.013, ηp2 = 0.27; for parieto-occipital electrodes F(1, 28) = 4.15, p =.026, ηp2 = 0.23). As can be seen in Fig. 7, Bonferroni corrected pairwise comparisons revealed that N250 amplitudes were significantly higher in the present self-face condition compared to other face condition (for parietal electrodes Mpresent = −8.23, SDpresent = 5.06; Mother= −5.70, SD other = 4.15, p =.015, for parieto-occipital electrodes Mpresent = −7.61, SDpresent = 5.26; Mother = −5.59, SDother = 4.78, p =.043). However, differences in N250 amplitudes between past self-face and present self-face condition (for parietal electrodes p = 1.000, for parieto-occipital electrodes p = 1.000), and past self-face and other face condition (for parietal electrodes p =.074, for parieto-occipital electrodes p =.067) did not reach significance level.

For the electrodes located in the temporo-parietal region, while no significant hemisphere effect (p =.411) were found on N250 amplitudes, significant main effect of face was found F(1, 28) = 6.41, p =.005, ηp2 = 0.31 (see, Fig. 7). Bonferroni corrected pairwise comparisons revealed that N250 amplitudes were significantly higher in the present self-face condition (M = −9.44 SD = 5.49) compared to the other face condition (M = −6.34, SD = 4.94) (p =.008). Similarly, significantly higher amplitudes were recorded in the past self-face condition (M = −9.35, SD = 5.49) compared to the other face condition (p =.028). However, differences in N250 amplitudes between the past self-face and present self-face conditions did not reach significance level (p = 1.000). In Fig. 8, traces of electrodes with significant differences in N250 amplitude under different facial conditions in the control group were illustrated.

It was also found a significant face*hemisphere interaction effect on N250 amplitudes in temporo-parietal regions F(1, 28) = 4.91, p =.015, ηp2 = 0.26. Bonferroni corrected pairwise comparisons revealed that N250 amplitude differences between the present self-face condition (M = −10.12, SD = 6.19) and the other face condition (M = −6.38, SD = 5.62) were significant only in the electrode located in the right hemisphere (p =.008, see Fig. 9). No other pairwise comparisons reach the significance level (prange = 0.094 to 1.000).

After examining the N250 amplitude patterns of the control group under different facial conditions, we compared these values with those of FTP using Crawford & Howell t tests42 However, N250 amplitudes did not significantly differ between healthy controls and patients for any electrode under different face conditions. The results of all comparisons between FTP and control group for N250 amplitudes were shown in Table S4 in the Supplementary Material.

N250 latencies

To examine the effect of face and hemisphere on the N250 latencies of the electrodes in parietal (P7, P8), parieto-occipital (PO7, PO8) and temporo-parietal (TP9, TP10) regions, a 3 × 2 (face [past self-face, present self-face, other face] × hemisphere [right, left]) analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures was conducted for each region.

For all regions, no significant main effect of face, hemisphere, and face*hemisphere interaction were found in N250 latencies (for parietal electrodes pface = 0.794, phemisphere = 0.666, pface*hemisphere = 0.151; for parieto-occipital electrodes pface = 0.742, phemisphere = 0.366, pface*hemisphere = 0.559, for temporo-parietal electrodes pface = 0.877, phemisphere = 0.522, pface*hemisphere = 0.101).

To see possible differences in N250 latencies of healthy controls and FTP, we compared them using the Crawford & Howell t tests42 and found significant differences in the right temporo-parietal electrode (TP10) under the past self-face condition (see Table 3, for the results of all comparisons see Table S5 in Supplementary Material). The raincloud showing the distribution of N250 latencies at the electrodes where significant differences were obtained between the control group and FTP and the trace of the relevant electrode are shown in Fig. 10.

P300 amplitudes

(a) Raincloud plot showing the distribution of N250 latencies recorded at TP10, which was the only electrode where a significant difference between the FTP and the control group was found under the past self-face condition. The distributions represent the control group’s N250 latency values. Dashed lines labeled for the control group indicate the median of each distribution, while the second dashed line shows the FTP’s N250 latency value, providing a visual reference for the position of the FTP relative to the control group distribution. Asterisk indicates the significance level of the t-test comparing the FTP to the control group (* p <.05) (b) Trace of the TP10 where a significant difference between the FTP and the control group was found under the past self-face condition.

We examined the P300 amplitudes separately at electrodes in parietal (P3, P4 and P5, P6), centro-parietal (CP3, CP4) and anterior-frontal (AF3, AF4) regions. For all regions, a 3 × 2 (face [past self-face, present self-face, other face] × hemisphere [right, left]) analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures was conducted to determine the effect of face and hemisphere on the amplitudes of the electrodes.

For P3-P4 electrodes in the parietal region and CP3-CP4 electrodes in the centro-parietal regions, while no significant face*hemisphere interaction (for parietal electrodes/P3-P4 p =.133, for centro-parietal electrodes/CP3-CP4 p =.502) were found on P300 amplitudes, significant main effect of face (for parietal electrodes/P3-P4 F(1, 28) = 9.91, p <.001, ηp2 = 0.42; for centro-parietal electrodes/CP3-CP4 F(1, 28) = 6.53, p =.005, ηp2 = 0.32) and main effect of hemisphere (for parietal electrodes/P3-P4 F(1, 28) = 6.64, p =.022, ηp2 = 0.32; for centro-parietal electrodes/CP3-CP4 F(1, 28) = 13.31, p =.003, ηp2 = 0.49) were found.

As can be seen in Fig. 11, for the significant face effect, Bonferroni corrected pairwise comparisons revealed that P300 amplitudes were significantly lower in the present self-face condition compared to the other face condition (for parietal electrodes/P3-P4 Mpresent = 1.09, SDpresent = 3.38; Mother = 3.48, SDother = 2.72, p =.002, for centro-parietal electrodes/CP3-CP4 P4 Mpresent = 1.03, SDpresent = 2.42; Mother = 2.57, SDother = 1.67, p =.005). Besides, for P3-P4 electrodes, significantly lower amplitudes were found in the past self-face condition compared to the other face condition (Mpast = 1.59, SDpast = 3.16; Mother = 3.48, SDother = 2.72, p =.006). However, differences in P300 amplitudes between the past self-face and the present self-face condition did not reach the significance level for both parietal electrodes/P3-P4 (p = 1.000), and centro-parietal electrodes/CP3-CP4 (p = 1.000). In addition, for centro-parietal electrodes/CP3-CP4, P300 amplitudes did not significantly differ between the self-past and the other face condition (p =.055). Traces of electrodes with significant differences in P300 amplitude under different facial conditions in control group were shown in Fig. 12.

Raincloud plots showing the P300 amplitude distributions at the electrodes located in parietal (P3-P4, P5-P6) and centro-parietal regions (CP3-CP4). The solid lines within the boxplots represent the median values of the respective distributions. Asterisks indicate the significance levels of the comparisons between conditions (* p <.05, ** p <.01).

For the significant hemisphere effect, pairwise comparisons revealed that P300 amplitudes were significantly higher in the right hemisphere compared to the left hemisphere (for parietal electrodes/P3-P4 Mleft = 1.66, SDleft = 3.00; Mright = 2.44, SDright = 2.76, p =.022, for centro-parietal electrodes/CP3-CP4 Mleft = 1.28, SDleft = 2.16; Mright = 2.10, SDright = 1.77, p =.003, see Fig. 13).

Raincloud plots showing the P300 amplitude distributions in the left and right hemispheres at the electrodes located in parietal (P3-P4), and centro-parietal regions (CP3-CP4). The solid lines within the boxplots represent the median values of the respective distributions. Asterisks indicate the significance levels of the comparisons between conditions (* p <.05).

For P5-P6 electrodes located in the parietal region, significant main effect of face was found F(1, 28) = 10.94, p <.001, ηp2 = 0.44. As depicted in Fig. 13, Bonferroni corrected pairwise comparisons revealed that P300 amplitudes were significantly lower in the present self-face condition (M = 0.94, SD = 3.80) compared to the other face condition (M = 3.73, SD = 3.44) (p =.002). Similarly, significantly lower amplitudes were recorded in the past self-face condition (M = 1.31, SD = 3.38) compared to the other face condition (M = 3.73, SD = 3.44) (p =.003). However, differences in P300 amplitudes between the past self-face and present self-face conditions did not reach significance level (p = 1.000). No significant hemisphere effect (p =.123) or face*hemisphere interaction effect (p =.218) were found on P300 amplitudes.

For AF3-AF4 electrodes located in the frontal region, no significant main effect of face (p =.187), hemisphere (p =.428), and face*hemisphere interaction (p =.178) were found on P300 amplitudes.

We compared P300 amplitudes of FTP and the control group using Crawford & Howell t tests42 and found significant differences in the right centro-parietal electrode (CP4) under the present self-face condition (for the results of all comparisons see Table S6 in Supplementary Material). Accordingly, FTP has significantly higher P300 amplitudes compared to healthy controls (see Table 4). The raincloud showing the distribution of P300 amplitudes at the electrodes where significant differences were obtained between the control group and FTP and the trace of the relevant electrode are shown in Fig. 14.

P300 latencies

(a) Raincloud plot showing the distribution of P300 amplitudes recorded at CP4, which was the only electrode where a significant difference between the FTP and the control group was found under the present self-face condition. The distributions represent the control group’s P300 amplitude values. Dashed lines labeled for the control group indicate the median of each distribution, while the second dashed line shows the FTP’s P300 amplitude value, providing a visual reference for the position of the FTP relative to the control group distribution. Asterisk indicates the significance level of the t-test comparing the FTP to the control group (* p <.05) (b) Trace of the CP4 where a significant difference between the FTP and the control group was found under the present self-face condition.

We examined the P300 latencies separately at electrodes in parietal (P3, P4 and P5, P6), centro-parietal (CP3, CP4) and anterior-frontal (AF3, AF4) regions. For all regions, a 3 × 2 (face [past self-face, present self-face, other face] × hemisphere [right, left]) analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures was conducted to determine the effect of face and hemisphere on the latencies of the electrodes.

For all electrodes except AF3-AF4, no significant main effect of face (for parietal electrodes/P3-P4 p =.888; for parietal electrodes/P5-P6 p =.068; centro-parietal electrodes/CP3-CP4 p =.476), hemisphere (for parietal electrodes/P3-P4 p =.090; for parietal electrodes/P5-P6 p =.639; centro-parietal electrodes/CP3-CP4 p =.236), and face*hemisphere interaction (for parietal electrodes/P3-P4 p =.460; for parietal electrodes/P5-P6 p =.826; centro-parietal electrodes/CP3-CP4 p =.654) were found on P300 latencies.

For AF3-AF4 electrodes located in the frontal region, while no significant hemisphere effect (p =.157) or face*hemisphere interaction effect (p =.479) were found on P300 latencies, significant main effect of face was found F(1, 28) = 3.71, p <.038, ηp2 = 0.22 (see, Fig. 15). However, after Bonferroni correction, no pairwise comparisons remained alive. Still, traces obtained from AF3 and AF4 under different face conditions were illustrated in Fig. 16.

After examining possible differences in P300 latencies among healthy controls, we compared these values with the FTP’s using Crawford & Howell t tests42. We found a significant difference in P300 latencies only in the right anterior-frontal electrode (AF4) under the other face condition (Table 5 for the results of all comparisons between FTP and control group, see Table S7 in the Supplementary Material). The raincloud showing the distribution of P300 latencies at the electrodes where significant differences were obtained between the control group and FTP and the trace of the relevant electrode are shown in Fig. 17.

(a) Raincloud plot showing the distribution of P300 latencies recorded at AF4, which was the only electrode where a significant difference between the FTP and the control group was found under the other face condition. The distributions represent the control group’s P300 latency values. Dashed lines labeled for the control group indicate the median of each distribution, while the second dashed line shows the FTP’s P300 latency value, providing a visual reference for the position of the FTP relative to the control group distribution. Asterisk indicates the significance level of the t-test comparing the FTP to the control group (* p <.05) (b) Trace of the AF4 where a significant difference between the FTP and the control group was found under the other face condition.

Discussion

The aim of this study is to examine the behavioral and neural responses of a face transplant patient (FTP) for his past and present faces nine years following the transplantation. Our goal is to understand whether the past or the present face is perceived as self-face by comparing his responses with a control group. Therefore, we measured both behavioral responses and the electrophysiological responses over the cortical areas those are known to be related to self-face perception.

The behavioral data indicated that the control group identified their own past faces more rapidly than the faces of others. It seems that the past self-face is the most distinctive stimulus among the three stimuli. It might be because they may have excelled at remembering their past faces over present or other faces due to the more cognitive space allocated to past faces in their memory. Upon comparing the self-face discrimination scores of the FTP and control group, it was discovered that the control group outperformed the FTP for both present and past self-faces. It appears that neither the present nor the past faces of the FTP are processed in the same way as those in the control group. In addition, the control group identified others’ faces more rapidly than the FTP.In a previous study involving the same patient37we observed that while his face discrimination score was not substantially different, his face recognition score was markedly inferior compared to the control group. The FTP appears to struggle with facial processing overall. This may be attributed to two factors: firstly, he may have a visual processing impairment, as the damage to the facial region could have impacted the functionality of his eyes. Secondly, owing to social isolation, his in-person interactions may have been fewer than those of others. Consequently, his face perception may not be enhanced to the same extent as that of the healthy group. We can elect the first explanation since in the previous study37 we observed that his object discrimination and recognition performance was not significantly poorer than the performance of the control group, but his face recognition performance was poorer.

N170 is a typical electrophysiological response associated with face perception. Consequently, it is essential to ascertain how the N170 responses of the FTP differ from those of the healthy cohort. Consistent with the previous literature5,9,15,18,20we found a typical right hemispheric lateralization of N170 responses (higher amplitudes in the right side comparing to the left) in the control group. The same pattern was also valid for the latency. The N170 latency was shorter in the right hemisphere. However, the amplitude or latency of N170 did not significantly distinguish across various faces. Although some studies indicated that self-faces produce larger N170 amplitude compared to other faces or friend’s faces19,20. Alzueta et al.26 reported no significant differences in reaction times or N170 amplitudes between self and familiar faces, aligning with our findings.

The N170 is generally observed in the occipital, parietal, and parieto-occipital electrodes. The N170 amplitude of FTP for his past face was greater than that of the control group at the electrodes O1, P7, P8, PO7, PO8, TP9, and TP10. His past face was distinctly dissimilar from the other facial stimuli: his nose was narrowed and entirely deviated to the left, while the lower lip and its commissure were significantly squeezed. Probably due to the distinctive properties of his past face, it elicited higher N170 responses. Similarly, Doi27 indicated that esthetically degraded self-faces provoked higher N170 responses in healthy subjects. On the other hand, he was injured at the age of 3 months and until 19 years old. Therefore, the injured face might become an essential part of his identity and has an extensive cognitive space in his memory. Nevertheless, we did not detect the same discrepancy between the control group and the FTP regarding his present face. The FTP appears to have begun recognizing his present face as though it were his original self-image. This pattern is also consistent with the findings of Azevedo et al.38showing that face transplant patient could incorporate his present face into his self-identity in a period of 20 months. In our study, as 9 years have passed since the operation in which the FTP acquired his present face, it is thought that he has enough time to adapt to his present face neurally and psychologically.

We also observed that FTP’s N170 amplitude recorded from the electrode P8 for the faces of others was higher than that of controls. The activity recorded from the electrode P8 probably corresponds to the activity of right STS and/or FFA which are the brain regions correlated to face processing. A combined fMRI and electrophysiology study44 conducted to find out the source of N170 response indicated that the fusiform gyrus was the most probable neural generator of the N170 and they found striking individual differences in the distribution of the scalp topographical potential maps for N170. Our study also demonstrates that the FTP has an individual difference, demonstrating a stronger lateralization pattern in processing other faces in comparison to the controls. As it might be expected N170 latency was shorter in the right hemisphere electrodes showing a right hemisphere dominance in face processing while FTP revealed no difference in this fashion.

N250 component is known to reflect the face familiarity effect in the face perception literature: it is higher for familiar compared to unfamiliar faces and larger for the own-face compared to other faces23. We observed that the control group showed higher N250 amplitude for their present faces when compared to the other faces. This effect was most prominent in the right hemisphere electrodes and over parieto-occipital regions. However, N250 amplitude in temporoparietal regions was also higher for both present self and past self-faces. We did not observe any significant differences between FTP and the control group in N250 amplitudes for any of the face categories. However, there was a significant difference in N250 latency in TP10 electrode. The FTP gave considerably faster N250 responses for his past face in comparison to the control group. This may be attributed to the significant variations between his pre-operational and post-operational faces. His pre-operational face is obviously different from the standard facial physiognomy. Therefore, it might evoke an earlier self-face related N250 response. However, it seems that FTP has grown acclimated to his transplanted face since we have not detected any difference in his N250 responses and the responses of the control group.

P300 is a well-known attention-related ERP component. Therefore, it is important to determine which face (past or present) of the FTP will attract his attention compared to the control group. In the control group we found a right hemispheric effect in parietal and centro-parietal electrodes for all faces. However, in contrast to the literature showing higher P300 amplitudes for subject’s own faces21,25other faces generated greater P300 responses when compared to the present faces in our control group. Probably, since their past and present faces were familiar and the other faces were interchanging, they attracted greater attention from participants. However, the P300 amplitude of the FTP in the electrode CP4 for his present face was higher than that of the control group. This may be owing to the substantial alteration due to the face transplantation. His present face actually belongs to another individual (the donor). Therefore, he might not respond to his current face in the same way as the control group. Tacikowski and Nowicka21 also observed that self-name and self-face elicited higher P300 amplitudes and shorter latencies when compared to famous and unknown names/faces. When we consider P300 latency of the controls, no difference was found among different face categories. However, the P300 latency of the FTP for other faces exceeded that of the control group. This may be associated with his diminished facial recognition capability previously discussed.

To further interpret the P300 findings, it is essential to place this component within its proven role in novelty detection and cognitive incongruity. We interpret the enhanced P300 to the transplanted face as a novelty-triggered orienting response (novelty P3a), which is consistent with Friedman et al.‘s45 findings that link higher P3a amplitude to unexpected or deviant stimuli. This is consistent with the classic oddball phenomenon46 in which low-probability events enhance P3b responses. Moreover, frontal P300 asymmetry observed with incongruence (e.g., Stroop-like tasks) supports the notion that self/face–identity mismatch, as in FTP’s donor-derived visage, disproportionately engages attentional orienting systems. The greater P300 delay found in reaction to other faces in the FTP (relative to the control group) may suggest increased cognitive load or slowed evaluative processing, which could be due to broader deficiencies in holistic facial recognition. This difference in latency and amplitude could be due to continuing brain adaptation processes, in which attentional and identity-related representations are gradually reconfigured after face transplantation. Future research using eye-tracking and behavioral response metrics could help determine whether attentional engagement or recognition difficulties is the primary driver of these brain changes.

To our knowledge there is only one study38 investigating neural changes in self-face identification before and after transplantation. Before the transplantation, fMRI data indicated that the pre-injury face activated self-referential brain regions, including the medial frontal cortex (MFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and precuneus, more strongly than the post-injury face. However, 20 months after the transplantation, the post-transplant face began to elicit activation in these regions, while the injured face lost its neural representation. Compared to Azevedo et al.38 study, the face defined as his past face, the time he spent with this face, and the ratio of the time he spent with his post-operative face to the pre-operative face in our current study are quite different from each other. In our case, the face injury transpired when the patient was only three months old. Consequently, after undergoing several surgeries, he had facial injuries till the age of 19. Therefore, the patient spent 19 years until the face transplant operation with this face, which morphologically did not reflect the usual features, and 9 years with the postoperative face. In this respect, it should be taken into consideration that our patient may have developed self-awareness, which is assumed to have started to develop at the age of 15 months47,48 through his own injured and structurally damaged face and that the process of changing the pre-operative facial representation may have taken longer and this may have been reflected in neural and behavioral responses. Therefore, probably in our study, the representation of his former face is still vivid and unlike the face transplant patient in the previous study38, the FTP in our study develops noticeably different responses to their past face in terms of neural components such as N170 and N250.

These findings represent the inaugural ERP data comparing a control group with a face transplant patient, highlighting the disparities in his responses to his past and present faces. Our findings indicated notable disparities in self-face identity between the control group and the FTP. The most notable discovery is that his previous face appears significantly different; yet, he has begun to acclimate to his present face nine years post-transplantation. Our findings demonstrate that the brain reactions (N170, N250) of the face transplant patient to their new visage have started to mirror those of the healthy control group. Nevertheless, perhaps because the present face was sourced from a different individual, it continues to be regarded as a prominent stimulus (P300), differentiating it from the control group. Conversely, despite the passage of nine years since the transplant, it seems the patient has not completely relinquished the depiction of their former appearance. This phenomenon can be elucidated by the past face integrating into the individual’s identity via the formation of visual, sensory, and emotional associations during the developmental process. The findings indicate a potential key phase for the development of self-face perception, suggesting that the attainment of full flexibility may necessitate an extended duration.

These findings are congruent with recent research by Borgomaneri et al.49, who demonstrated the importance of temporo-occipital back-projections in the visual processing of emotional facial cues. They found that improving associative plasticity between the early visual areas (V1/V2) and the posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS) improves the perception of emotional expressions, highlighting the crucial role that recursive processing pathways play in facial perception. In the context of face transplantation, our findings suggest that similar associative plasticity might occur gradually, contributing to the slow acclimation process observed in the FTP. It is possible that repeated exposure and neural plasticity mechanisms over extended periods facilitate the gradual neural integration of the transplanted face. Therefore, neuromodulation techniques can be used to improve plasticity and face perception of the transplantation patients during their adaptation process.

Recent findings in cognitive neuroscience suggest that self-identity involves both a minimal self and a narrative self39. The minimal self refers to the immediate, pre-reflective sense of self grounded in bodily ownership and agency, whereas the narrative self entails the autobiographical and temporally extended identity formed through personal memories and social narratives. These conceptualizations align with neural correlates observed in self-face perception. For example, the default mode network (DMN)—including regions like the medial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex—is associated with narrative self-processing and autobiographical memory, while the salience and sensorimotor networks are more closely tied to bodily awareness and agency, reflecting aspects of the minimal self40,41. Integrating these models helps explain our findings: the patient’s strong N170 and N250 responses to the preoperative face may reflect a deeply embedded minimal self grounded in long-term somatosensory experience, while the elevated P300 response to the present face may indicate ongoing narrative reconstruction and attentional allocation toward a newly forming self-image. In this sense, studies on facial transplantation significantly enrich cognitive neuroscience models of self-identity by shedding light on the neural and temporal mechanisms of self-recognition and adaptation.

This study highlights significant social implications, particularly in addressing face transplant patients’ psychological and social challenges. Adapting to a present face is not solely a physiological process but also involves complex social and emotional aspects. Patients often encounter societal stigma, altered self-identity, and difficulties in social integration. Years after transplantation, neural responses may indicate lingering attachment to the pre-transplant face. These findings emphasize the importance of comprehensive rehabilitation programs integrating medical, psychological, and social support to improve patients’ long-term well-being.

Limitations and future directions

It is crucial to acknowledge several considerations that may guide future research and contribute to the improvement of the field. While the present study offers significant contributions, there are still some limitations. First, the relatively limited number of trials during electrophysiological recordings may have reduced the signal-to-noise ratio, potentially affecting the sensitivity and stability of the observed effects. Second, the single-case design inherently limits the generalizability of the findings, as all behavioral and neural results are based on one face transplant patient. As face transplantation is still a relatively new and rare procedure, data collection from larger groups of patients has not yet been feasible.

Additionally, the absence of pre-transplant baseline data prevents direct comparisons of neural adaptation before and after surgery. Future research should seek to address these restrictions by including larger and more diverse samples as more patients become available. Therefore, the number of trials can be increased, multiple recording sessions can be utilized to improve statistical power, and, where possible, longitudinal designs that track neural and psychological adaptation over time can be implemented. Such efforts will help enhance the reliability, stability, and generalizability of the findings and will provide a more extensive understanding of the processes underlying self-face recognition following face transplantation. Future research should systematically assess these psychosocial factors using validated tools and qualitative methods to guide the development of more effective interventions aimed at supporting the long-term well-being and quality of life for face transplant patients.

Method

Participants

The control group consisted of fifteen male subjects between the ages of 18–26 years (M = 21.6, SD = 1.45). Based on their self-reported baseline data, none of the participants had a history of neurological or psychological disorders, nor were they undergoing any medical treatment during the study. All of the participants were right-handed.

The face transplant patient (FTP) was harmed in a fire accident when he was just 3 months old. Despite undergoing eight surgeries, he was unable to create any facial expressions. The lower lip and its commissure were significantly contracted, and his nose was excessively crooked to the left. By the approval of the national ethical board, he underwent a full-face transplant in January 2012 when he was 19 years old excluding the eyelids, from a 37-year-old donor. Nine years following the procedure, at the age of 28, he underwent testing. The FTP was also right-handed.

The study was approved by the Akdeniz University Ethical Committee for Social Sciences. Controls and the FTP provided informed consent to participate in the study. In addition, informed consent to publish identifying information or images was obtained from the participants.

Materials and procedure

Face stimuli

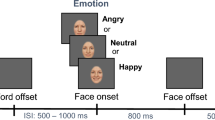

Three different facial stimuli were used in the study. These were a past photograph of the participant’s own face (past self-face), a recently captured photograph of the participant’s own face (present self-face), and photographs of stranger faces (other face).

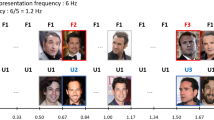

Photographs of the participants were taken in the laboratory settings using a Canon DSLR camera under standard lighting and distance conditions. For past self-face category, participants were asked to bring a passport photo of their face from at least one year ago. For the other face category, male facial stimuli from the Bogazici Face Database50 were chosen. Considering whether the participants had beards, we selected half of the unfamiliar faces with beards and half without. Facial accessories, such as piercings, earrings, etc., which could potentially affect attention and face processing were removed from the photographs. Unlike the other participants, the “past face” photograph of the face transplant patient refers to an image taken prior to his face transplant surgery. Therefore, the “present face” photograph corresponds to the current photo taken for the research after the surgery. Using the Adobe Photoshop software, all facial stimuli were placed on a black background in an oval frame, excluding hair and neck (Fig. 18), and they were processed using the SHINE toolbox in MATLAB to control luminance and spatial frequency51.

Procedure

When the participants arrived at the laboratory, they were informed about the study and their consent was obtained, and the participant was taken to the room where the EEG recording would be taken and the experimental task would be performed. After the placement of the EEG electrodes was completed, the face recognition task was initiated and the EEG signals were recorded simultaneously.

In this task, participants were asked to identify which of the presented face photographs belonged to them and which did not. Similar tasks were used in previous literature10,20. As previously mentioned, participants viewed a past face photograph of themselves (preoperative face for the FTP), a present face photograph of themselves (postoperative face for the FTP), and photographs of other individuals’ faces. The task started with a fixation cross lasting 200 ms. A stimulus was then presented on the screen for 1000ms, followed by a gray screen during the inter-stimulus interval averaging 2200 ms. Participants were asked to press either “1” or “2” within 1000 ms of the stimulus presentation. Participants had to press “1” when they saw their own facial photographs and “2” when they saw photographs of others (for task sequence see Fig. 19). A total of 10 different face stimuli were selected for the other face category and these stimuli were presented twice in the task. In order to be equal in number with the total of 20 other-face presentations, the participant’s past self-face photograph and his/her own present face photograph were presented 20 times each. Thus, the task consisted of 60 trials in total. Stimuli were presented pseudo-randomly, with the participant’s own photographs presented non-consecutively. In addition, a practice phase consisting of a total of 6 trials (4 other-face, 1 self-past and 1 present self-face) was presented at the beginning of the task. Since all participants, including the face transplant patient (FTP), were right-handed, a bimanual response format was employed in the experiment. The participants were instructed to press the “1” key on the keyboard with their left hand for their own faces, and the “2” key with their right hand for other faces. To minimize confusion, the task was intentionally kept as simple as possible; therefore, a counterbalancing procedure for hand use was not implemented.

EEG procedures

The experiments were conducted in a dark, sound-attenuated room. Brain activity was recorded using a 64-channel BrainVision Active Electrode EEG system. The FCz electrode served as the reference, and the Iz electrode was positioned below the right eye to detect ocular artifacts. Electrode impedances were maintained below 25 kΩ. EEG signals were amplified using a BrainAmp EEG/EP Amplifier (Brain Products, Munich, Germany) and digitized at a sampling rate of 1000 Hz with BrainVision Recorder software (Brain Products, Munich, Germany). Active shielding was applied to minimize noise during the recording process. The participant’s chair was positioned to match their height, with the computer screen set at a distance of 75 cm. They were instructed to remain as still as possible throughout the experiment and avoid blinking or speaking while the stimulus was presented. The participants’ heads were positioned on a chinrest throughout the experiment to ensure stability. The experimental session began once the participant was fully prepared. E-Prime 3 software was used to deliver the stimuli, collect behavioural data, and send triggers to the EEG computer.

EEG preprocessing

The EEG data were processed offline using BrainVision Analyzer software (BrainProducts GmbH, Munich), with the signals downsampled to 250 Hz and filtered using a band-pass filter. (0.01–80 Hz). In addition, a 50 Hz notch filter was employed to prevent noise from electrical sources.

The data were segmented between − 200 and 1000 ms according to the stimulus onset. Baseline correction was applied in the range of −200 to 0. After this stage, the data were subsequently re-segmented based on the visual stimulus onset (0–2000 ms). Semiautomatic artifact rejection was performed to exclude trials containing ocular or muscular artifacts, based on predefined amplitude thresholds and visual inspection. Event-related potentials (ERPs) were analyzed using the semiautomatic peak detection method in BrainVision Analyzer, which enables automated identification of component peaks with the possibility of manual verification for accuracy. Since increased eye movements were detected in the FTP, an extraocular correction (EOG correction) was applied to remove artifacts resulting from eye movements in the EEG recordings. Average amplitude values were calculated for each ERP component across trials. Only clean trials that passed artifact rejection procedures were included in the analyses to guarantee the validity of the results. After preprocessing for all participants, including the FTP, an average of 90% of trials were kept. For the FTP, an average of 19.6 trials per condition remained after 1 out of 60 trials were eliminated because of artifacts from muscle noise. To reduce fatigue and increase compliance during EEG recording, longer trial times or more trials were avoided. Extended trial durations or increased trial counts were avoided to minimize fatigue and maximize compliance during EEG recording. This constraint is consistent with previous ERP studies involving clinical or single-case participants, where shorter tasks are often necessary for valid and artifact-free data collection.

The analysis focused on three ERP components of interest: N170, N250, and P300. The time windows used for quantifying these components were 100–210 ms for N170, 211–370 ms for N250, and 250–600 ms for P300, based on prior literature and observed waveform morphology. We calculated the mean amplitude within the selected time windows.

Statistical approach

In behavioral examinations, we focused on how accurately they were able to identify whether the presented faces were theirs or not (hits and correct rejections), and on reaction times on correctly responded trials.

Prior to the main analyses, a data cleaning procedure was applied to the accuracy rates and reaction times (RTs) obtained for each face condition. Specifically, z-scores were calculated for each participant’s accuracy and RT values within each condition to identify potential outliers. Data points falling outside the ± 1.96 z-score range were considered candidates for exclusion. Since there were three face conditions, six z-scores (three for accuracy, three for RTs) were computed per participant.

The results showed that for 14 out of 15 participants, all accuracy and RT scores across all face conditions were within the acceptable ± 1.96 range. For one participant, the z-score for the reaction time in the “present self-face” condition slightly exceeded this threshold (z = 1.98). However, as this value was on the borderline of the cut-off and the participant’s other accuracy and reaction time scores across all conditions fell well within the acceptable range, this participant’s data were retained and not classified as an outlier.

Since the primary aim of the study was to investigate neural responses, a deliberately simple behavioral task was used to ensure participant engagement without introducing excessive cognitive load. In this task, participants were asked to identify whether the face presented belonged to themselves. As expected, the error rates were very low due to the simplicity of the task. Therefore, tests of normality were applied specifically to the distribution of reaction times, as the accuracy data were not suitable for normality testing due to the insufficient variability in the distributions. Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests of normality conducted on RTs indicated that the data were normally distributed across all conditions (for all conditions p >.05).

After data curation phase, we performed repeated measures ANOVAs separately for the accuracy rates and reaction times to determine whether the recognition performance of the control group varied across the different facial conditions. Next, we analyzed whether the behavioral findings of FTP differed from the control group in each face condition. For this, we adopted the recommended single-case method developed by Crawford et al.42 instead of the more liberal one-sample t-test.

The Crawford-Howell t-test is specifically designed for single-case comparisons and has become a widely accepted method in neuropsychology and neuroimaging research. Unlike standard one-sample t-tests, which tend to inflate Type I error rates, particularly when control group sizes are small, the Crawford-Howell approach maintains accurate Type I error control, as demonstrated through extensive simulations52. This method appropriately accounts for the uncertainty in estimating the control group’s mean and variance, making it particularly suitable for single-case analyses. Given these advantages, the Crawford-Howell t-test has been frequently used in recent neuroimaging studies to provide statistically valid inferences when comparing individual cases to normative samples53.

For electrophysiological investigations, we first calculated the latency and amplitude values at the electrodes located in certain regions. We then examined the amplitude and latency differences in N170, N250, and P300 potentials in control group in response to different facial stimuli using repeated measures ANOVAs. Then, we compared the data of control group to FTP’s with Crawford-Howell t-tests42.

For ANOVAs and graphical representations of all comparisons, we utilized JASP v0.19.1, and Jamovi v2.6.19. We used Singlims_ES54 software for single case t tests. For all analyses, Type I error probability was set at 0.05. For repeated measures ANOVAs, sphericity assumption was checked by Mauchly’s test of sphericity, and in cases where the assumption of sphericity was violated, results were reported using Greenhouse-Geisser (if the epsilon value was less than 0.75) or Huynh-Feldt correction (if the epsilon value was greater than 0.75). Bonferroni correction was applied specifically to the ANOVA-based post-hoc comparisons within the control group, where we tested whether behavioral and electrophysiological responses varied across conditions. This correction aimed to avoid family-wise error and to maintain a constant Type I error probability across multiple comparisons that were conceptually tied to a single inferential conclusion. In contrast, p-value adjustment was not applied to most of the Crawford-Howell t-tests comparing the FTP and control group. These individual t-tests were conducted on distinct dependent measures, each addressing a separate, pre-specified hypothesis. The aim was not to derive a unified conclusion from these comparisons, but rather to evaluate and interpret specific group differences independently. Thus, despite the presence of multiple dependent variables, the fact that only a single independent variable with two levels (FTP and control) was involved, and that there was no intention to draw an aggregated inference, p-value was not adjusted, as recommended in previous literature55,56. However, since P300 latencies and amplitudes in the parietal regions were obtained from two adjacent electrodes rather than a single one, the critical p-value was adjusted by dividing the alpha level by the number of tests conducted to assess P300 differences between the FTP and control groups in the parietal regions.

A part of this study was presented as poster presentation at the 20th National Neuroscience Congress being held October 19 – 22, 2022 at Acibadem University in Istanbul Türkiye.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Haxby, J. V., Hoffman, E. A. & Gobbini, M. I. The distributed human neural system for face perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 4 (6), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01482-0 (2000).

Parvizi, J. et al. Electrical stimulation of human fusiform face-selective regions distorts face perception. J. Neurosci. 32 (43), 14915–14920. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2609-12.2012 (2012).

Northoff, G. Brain and self–a neurophilosophical account. Child. Adol Psyc Men. 7, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-7-28 (2013).

Platek, S. M. & Kemp, S. M. Is family special to the brain? An event-related fMRI study of familiar, familial, and self-face recognition. Neuropsychologia 47 (3), 849–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.12.02 (2009).

Sugiura, M. et al. Cortical mechanisms of visual self-recognition. Neuroimage 24 (1), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.063 (2005).

Sugiura, M. et al. Face-specific and domain-general characteristics of cortical responses during self recognition. Neuroimage 42 (1), 414–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.054 (2008).

Turk, D. J. et al. Mike or me? Self-recognition in a split-brain patient. Nat. Neurosci. 5 (9), 841–842. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn907 (2002).

Keenan, J. P., Wheeler, M., Platek, S. M., Lardi, G. & Lassonde, M. Self-face processing in a callosotomy patient. Eur. J. Neurosci. 18 (8), 2391–2395. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02958.x (2003).

Uddin, L. Q., Kaplan, J. T., Molnar-Szakacs, I., Zaidel, E. & Iacoboni, M. Self-face recognition activates a frontoparietal mirror network in the right hemisphere: an event-related fMRI study. Neuroimage 25 (3), 926–935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.018 (2005).

Uddin, L. Q., Molnar-Szakacs, I., Zaidel, E. & Iacoboni, M. rTMS to the right inferior parietal lobule disrupts self–other discrimination. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neur. 1 (1), 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsl003 (2006).

Zeugin, D., Notter, M. P., Knebel, J. F. & Ionta, S. Temporo-parietal contribution to the mental representations of self/other face. Brain Cognition. 143, 105600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2020.105600 (2020).

Breen, N., Caine, D. & Coltheart, M. Mirrored-self misidentification: two cases of focal onset dementia. Neurocase 7 (3), 239–254. https://doi.org/10.1093/neucas/7.3.239 (2001).

Feinberg, T. E. & Shapiro, R. M. Misidentification–reduplication and the right hemisphere. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 2 (1), 39–48 (1989).

Yun, J. Y. et al. Dysfunctional role of parietal lobe during self-face recognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 152 (1), 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.010 (2014).

Platek, S. M. et al. Neural substrates for functionally discriminating self-face from personally familiar faces. Hum. Brain Mapp. 27 (2), 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20168 (2006).

Devue, C. & Brédart, S. The neural correlates of visual self recognition. Conscious. Cogn. 20 (1), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2010.09.007 (2011).

Devue, C. et al. Here I am: the cortical correlates of visual self-recognition. Brain Res. 1143, 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.055 (2007).

Molnar-Szakacs, I. & Uddin, L. Q. Laterality and hemispheric specialization of self-face recognition. Neuropsychologia 186, 108586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2023.108586 (2023).

Geng, H., Zhang, S., Li, Q., Tao, R. & Xu, S. Dissociations of subliminal and supraliminal self-face from other-face processing: behavioral and ERP evidence. Neuropsychologia 50 (12), 2933–2942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.07.040 (2012).

Keyes, H., Brady, N., Reilly, R. B. & Foxe, J. J. My face or yours? Event-related potential correlates of self-face processing. Brain Cognition. 72 (2), 244–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2009.09.006 (2010).

Tacikowski, P. & Nowicka, A. Allocation of attention to self-name and self-face: an ERP study. Biol. Psychol. 84 (2), 318–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.03.009 (2010).

Olivares, E. I., Iglesias, J., Saavedra, C., Trujillo-Barreto, N. J. & Valdés-Sosa, M. Brain signals of face processing as revealed by event-related potentials. Behav. Neurol. 2015 (1), 514361. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/514361 (2015).

Estudillo, A. J. & Commentary My face or yours? Event-related potential correlates of self-face processing. Front. Psychol. 8, 608. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00608 (2017).

Picton, T. W. The P300 wave of the human event-related potential. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 9, 456–456. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004691-199210000-00002 (1992).

Ninomiya, H., Onitsuka, T., Chen, C. H., Sato, E. & Tashiro, N. P300 in response to the subject’s own face. Psychiat Clin. Neuros. 52 (5), 519–522. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1819.1998.00445.x (1998).

Alzueta, E., Kessel, D. & Capilla, A. The upside-down self: one’s own face recognition is affected by inversion. Psychophysiology 58 (12), e13919. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.13919 (2021).

Doi, H. & Multivariate ERP analysis of neural activations underlying processing of aesthetically manipulated self-face. Appl. Sci. 12 (24), 13007. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122413007 (2022).

Kotlewska, I., Panek, B., Nowicka, A. & Asanowicz, D. Posterior theta activity reveals an early signal of self-face recognition. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 13823. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41071-y (2023).

Homsy, P. et al. An update on the survival of the first 50 face transplants worldwide. JAMA Surg. 159 (12), 1339–1345. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2024.3748 (2024).

Süzen, E. et al. Delta waves as a sign of cortical plasticity after full-face transplantation. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 16454. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67469-w (2024).

Şavklıyıldız, A. et al. Adaptive analysis of cortical plasticity with fMRI in full face and arm transplants. Brain Imaging Behav. 15, 1788–1801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-020-00374-8 (2021).

Bedeloglu, M. et al. Image-based analysis of emotional facial expressions in full face transplants. J. Med. Syst. 42, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-018-0895-8 (2018).

Gülbetekin, E., Bayraktar, S., Özkan, Ö. & Özkan, Ö. Subjective recognition of emotional expressions in face transplant patients. J. Nonverbal Behav. 41, 325–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-017-0259-y (2017).

Topçu, Ç. et al. Assessment of emotional expressions after Full-Face transplantation. Neural Plast. 2017 (1), 8789724. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/8789724 (2017).

Topçu, Ç. et al. Recovery of facial expressions using functional electrical stimulation after full-face transplantation. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 15, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-018-0356-0 (2018).

Uysal, H. et al. ID 382–Electrophysiological evaluation of emotional expressions in the facial transplantation patients. Clin. Neurophysiol. 127 (3), e127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2015.11.431 (2016).

Gülbetekin, E., Bayraktar, S., Özkan, Ö., Uysal, H. & Özkan, Ö. Face perception in face transplant patients. Facial Plast. Surg. 35 (05), 525–533. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1666786 (2019).

Azevedo, R. T. et al. Re-cognizing the new self: the neurocognitive plasticity of self-processing following facial transplantation. P Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 120 (14), e2211966120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2211966120 (2023).

Gallagher, S. Philosophical conceptions of the self: implications for cognitive science. Trends Cogn. Sci. 4 (1), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(99)01417-5 (2000).

Northoff, G. et al. Self-referential processing in our brain—a meta-analysis of imaging studies on the self. Neuroimage 31 (1), 440–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.002 (2006).

Seth, A. K. Interoceptive inference, emotion, and the embodied self. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17 (11), 565–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.09.007 (2013).

Crawford, J. R., Garthwaite, P. H. & Howell, D. C. On comparing a single case with a control sample: an alternative perspective. Neuropsychologia 47 (13), 2690–2695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.04.011 (2009).

Abreu, A. L., Fernández-Aguilar, L., Ferreira-Santos, F. & Fernandes, C. Increased N250 elicited by facial familiarity: an ERP study including the face inversion effect and facial emotion processing. Neuropsychologia 188, 108623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2023.108623 (2023).

Gao, X., Vuong, Q. C. & Rossion, B. The cortical face network of the prosopagnosic patient PS with fast periodic stimulation in fMRI. Cortex 119, 528–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2018.11.008 (2019).

Friedman, D., Cycowicz, Y. M. & Gaeta, H. The novelty P3: an event-related brain potential (ERP) sign of the brain’s evaluation of novelty. Neurosci. Biobehav R. 25 (4), 355–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-7634(01)00019-7 (2001).

Sutton, S., Braren, M., Zubin, J. & John, E. R. Evoked-potential correlates of stimulus uncertainty. Science 150 (3700), 1187–1188. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.150.3700.1187 (1965).

Anderson, J. R. The development of self-recognition: A review. Dev. Psychobiol. 17 (1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.420170104 (1984).

Brownell, C. A., Zerwas, S. & Ramani, G. B. So big: the development of body self-awareness in toddlers. Child. Dev. 78 (5), 1426–1440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01075.x (2007).

Borgomaneri et al. Increasing associative plasticity in temporo-occipital back-projections improves visual perception of emotions. Nat. Commun. 14 (1), 5720. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-41058-3 (2023).

Saribay, S. A. et al. The Bogazici face database: standardized photographs of Turkish faces with supporting materials. PloS One. 13 (2), e0192018. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192018 (2018).

Dal Ben, R. SHINE color and Lum_fun: A set of tools to control luminance of colored images (Version 0.2)[Computer software] (2019).

Crawford, J. R. & Howell, D. C. Comparing an individual’s test score against norms derived from small samples. Clin. Neuropsychol. 12 (4), 482–486. https://doi.org/10.1076/clin.12.4.482.7241 (1998).

Faghel-Soubeyrand et al. Neural computations in prosopagnosia. Cereb. Cortex. 34 (5), bhae211. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhae211 (2024).

Crawford, J. R. & Garthwaite, P. H. Investigation of the single case in neuropsychology: Confidence limits on the abnormality of test scores and test score differences. Neuropsychologia 40(8), 1196–1208. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0028-3932(01)00224-X (2002).

Rubin, M. When to adjust alpha during multiple testing: A consideration of disjunction, conjunction, and individual testing. Synthese 199 (3), 10969–11000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-021-03276-4 (2021).

Rubin, M. Inconsistent multiple testing corrections: the fallacy of using family-based error rates to make inferences about individual hypotheses. Methods Psychol. 10, 100140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metip.2024.100140 (2024).

Funding

This study was supported by the Akdeniz University, Scientific Research Project Coordination Unit. Project Number SBA-2019-4254.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions