Abstract

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness. Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is the most common form globally and has been linked to mitochondrial dysfunction and energy deficiency. Plasma was used to investigate the energy metabolomic profiles of patients with POAG and controls, and to determine the metabolite flux within the core interconnected energy pathways. Targeted liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) was used to analyze plasma energy metabolism in POAG patients and controls. Differential metabolite expression analysis, correlation analysis, and pathway flux analysis were then conducted to elucidate the metabolic alterations and the mechanisms underlying POAG. Our findings reveal elevated levels of D-Glucose-6-phosphate(G6P), 6-Phosphogluconic acid(6PGA), Adenosine diphosphate(ADP), Adenosine monophosphate(AMP), Adenosine triphosphate(ATP), Guanosine diphosphate(GDP), Inosine monophosphate(IMP), Phosphoenolpyruvic acid(PEP), Phosphorylethanolamine(pEtN), and uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine(UDP-GlcNAc) in POAG patients. Conversely, POAG patients showed reduced ratios of ATP/ADP, Glycerol-3-phosphate(G3P)/ Dihydroxyacetone phosphate(DHAP), 1,3-Bisphosphoglyceric acid(BPG)/DHAP, PYR/PEP, Fumarate/Succinate, Arginine/ASA, and Citrulline/Ornithine. These findings collectively suggest disrupted flux in glycolysis, the TCA cycle, urea cycle, and tyrosine metabolism, offering new insights into POAG mechanisms and potential therapeutic strategies targeting energy metabolic pathways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is the most common form of glaucoma, accounting for approximately 74% of glaucoma cases globally1. POAG is characterized by the progressive degeneration of retinal ganglion cells and optic nerve damage, a process that occurs insidiously and results in irreversible vision loss. This silent progression poses significant challenges for early detection. Clinically, POAG is often linked to elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), and current treatment strategies predominantly aim at reducing IOP. However, advances in diagnostic methods have revealed a multifactorial basis for POAG, implicating vascular, genetic, anatomical, and immune factors in disease development2. Additionally, omics approaches—transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—have been utilized to elucidate the complex pathogenesis of POAG, yielding insights into associated pathways and potential biomarkers for POAG diagnosis3,4,5,6,43.

As a downstream readout of all omics processes, metabolomics offers unique biomarkers that can provide insights into disease progression and the pathophysiology of POAG at the final stages of molecular regulation. Previous studies have identified distinct metabolomic profiles in the aqueous humor and plasma of POAG patients6,42, utilizing both targeted and untargeted approaches. These studies have suggested potential pathological mechanisms involving amino acid metabolism6,7,8, phospholipid metabolism9,10, glucose metabolism11,12,13 and mitochondrial and energy-related dysfunctions7,14.

Energy metabolism, or central carbon metabolism, encompasses processes that generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP) from nutrients through aerobic and anaerobic respiration, supporting essential cellular functions. This metabolic network includes glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and the pentose phosphate pathway, and others. Recent studies have examined central carbon metabolism in primary angle-closure glaucoma (PACG) patients, focusing on metabolite biomarkers and their correlations with the gut microbiome15. Quantifying energy metabolism not only provides insight into cellular energy management but also allows for the investigation of metabolite flux within these interconnected pathways16,17,18.

Although mitochondrial dysfunction and energy metabolism disruptions have been observed in glaucoma, including altered mitochondrial substrates, gene mutations, and structural abnormalities7,12,19,20,21, a comprehensive energy metabolomics analysis in POAG has yet to be undertaken to illustrate the alterations in the energy metabolism landscape. In this study, we assessed plasma energy metabolism in 25 participants using targeted liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). By examining correlations and flux among plasma metabolites, we aim to elucidate potential pathogenic roles of altered energy metabolism in POAG.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the participants in POAG and control groups

Twenty-five participants were recruited for this study, including 10 POAG patients and 15 cataract controls. The basic information for each group is shown in Table 1. There were no statistical differences between the two groups in age(p = 0.06), gender(p = 1.0), IOP(p = 0.11), BCVA(p = 0.82), AL(p = 0.27) ACD(p = 0.23) and CCT(p = 0.94). POAG group has significantly higher cup/disc ratio(C/D) than control group.

Differentially expressed metabolites in targeted energy metabolomic analysis

Plasma energy metabolomics was conducted to uncover metabolic discrepancies between POAG patients and controls. A total of 57 metabolites were targeted, with 42 detected across most samples. Figure 1A provides an overview heatmap of all detected metabolites, and Fig. 1B presents averaged metabolite expression between the groups. To define the discriminatory metabolomic profile between POAG and control groups, a supervised ortho-PLS-DA (Orthogonal Partial Least Squares - Discriminant Analysis) model was applied, effectively separating the groups (Fig. 2A). Despite a limited sample size, this model explained most variance (R²=0.717) and demonstrated robust leave-one-out cross-validation quality (Q²=0.32) (Fig. 2B and C).

To identify key metabolites, variable importance in projection (VIP) scores were derived from the ortho-PLS-DA model, as shown in Fig. 3A & Figure S1. Eighteen metabolites exhibited VIP scores exceeding 1, with 12 upregulated and 6 downregulated in POAG. Further analysis of fold change (FC) and p-values of all metabolites is presented in Fig. 3B, identifying 11 upregulated and 2 downregulated differentially expressed metabolites (DEMs) in POAG (FC > 1.2, p < 0.05). For validation, significance analysis of metabolites (SAM, which uses permutation-based testing with a modified rank statistic, focusing on false discovery rate (FDR) control to identify significant metabolites) and empirical Bayesian analysis of metabolites (EBAM, which is particularly effective for small sample sizes and addressing variance instability) were employed, confirming DEMs (Fig. 3C and D). SAM identified 13 DEMs with FDR < 0.05, and EBAM revealed 11 upregulated and 3 downregulated DEMs in POAG (FDR < 0.05). A Venn diagram illustrated overlap among the identified DEMs, resulting in a core set of 10 DEMs common to all methods and a comprehensive set of 21 DEMs (Fig. 3E). Notably, the core set included D-Glucose-6-phosphate (G6P), 6-Phosphogluconic acid (6PGA), ADP, AMP, ATP, GDP, IMP, Phosphoenolpyruvic acid (PEP), Phosphorylethanolamine (pEtN), and UDP-GlcNAc, with the remaining DEMs providing additional biological insights (Glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P), BPG, Argininosuccinic acid (ASA), Succinic acid, D-Glucose-1-phosphate, D-Glutamine, L-Arginine, L-Citrulline, Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, D-Ribulose-5-phosphate and Phenyllactate). By selecting the comprehensive set DEMs for OPLSDA for adjustment, the new model yields a better prediction capability Q² = 0.419 (as shown in Figure S2).

Differentially expressed metabolites in POAG and control groups. (A) The DEMs with VIP score>1. Red means high in POAG and blue means low in POAG. (B) The DEMs with fold changes >1.2 and p value<0.05 in volcano plot. (C) The DEMs with FDR<0.05 in SAM plot. (D) The DEMs with FDR<0.05 in EBAM plot (DEMs are shown in green dots). (E) The Venn map showing the overlapped DEMs by the above four methods.

Correlation and flux of the energy metabolism related metabolites

In addition to the expression of DEMs, metabolite correlations are also critically important for understanding changes in energy metabolism. The correlation heatmap is shown in Fig. 4A, revealing a central, highly correlated core of metabolites in the purine and glycolysis pathways, as well as phosphorylated compounds. This core exhibited positive correlations with glycolysis and TCA cycle metabolites and negative correlations with urea cycle and phenylalanine metabolism metabolites, including downstream glycolysis products (e.g., G3P, BPG). Representative metabolite correlations are illustrated in Fig. 4B. Additionally, debiased sparse partial correlation (DSPC) network analysis was conducted via MetaboAnalyst 6.0 to condition on all other metabolites (Fig. 4C). DSPC, particularly suitable for smaller samples and high-dimensional data, revealed distinct correlations such as a positive association between D-Glutamine and inosine. Significant negative correlations, such as L-Citrulline/Lysine, L-Cystine/Inosine, and Ornithine/L-Glutamate were also observed and may need further investigation.

The correlations of the energy metabolism metabolites. (A) The paired correlation matrix heatmap. (B) The correlation for specific metabolites (e.g. G6P, G3P and L-Arginine). (C) Debiased Sparse Partial Correlation (DSPC) Network. Metabolites are represented as nodes, and the edges depict the partial correlation of DSPC between two metabolites after conditioning on all other metabolites. The red lines show positive correlations, while blue lines show negative correlations between metabolites.

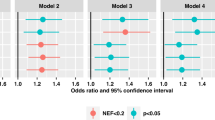

To assess pathway disruptions, the average metabolite expression along the pathway were shown in Fig. 5A. Analysis revealed three flux breakpoints: at G3P and BPG, phenyllactate-tyrosine, and within the urea cycle. To illustrate the flux disruption, 28 metabolite fluxes were calculated and visualized as a heatmap in Fig. 5B as previous reported22(fluxes were estimated as the ratio between two metabolites), with t-scores and significant changes highlighted in Fig. 5C. The POAG group exhibited lower ratios of R5P/6PGA, AMP/IMP, ATP/ADP, BPG/DHAP, G3P/DHAP, PYR/PEP, Fumarate/Succinate, Arginine/ASA, and Citrulline/Ornithine compared to controls, indicating metabolic bottlenecks and a potential energy deficiency in POAG.

The alteration of the energy metabolism pathway in POAG. (A) Illustration of the energy metabolism pathway. Red: upregulated DEM (core set) in POAG compared to controls; Orange/Cyan: Up-/downregulated metabolites of interest from the comprehensive DEMs set that did not meet strict statistical significance thresholds. Gray labels: undetected. (B) The heatmap of the fluxes in selected metabolite-pairs. (e.g. ATP/ADP ratio) (C) Corresponding t-statistics of these fluxes. Asterisks (*) indicate |t-score| > 2.

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the plasma energy metabolism profile in POAG patients, identifying significant differences in metabolite expression, correlations, and pathway fluxes compared to controls. Our findings reveal several critical metabolic flux breakpoints in the pathways of glycolysis, the TCA cycle, and the urea cycle. Notably, dysregulation was observed in the production of BPG, ATP, G3P, PYR, fumarate, arginine, and citrulline, shedding light on potential mechanisms of POAG pathophysiology at the metabolic level.

The differential metabolites identified in this study were consistently selected using multiple criteria, including fold change, p-value, VIP scores, SAM, and EBAM, which strengthens confidence in their biological relevance. Notably, several core metabolites (such as D-glucose-6-phosphate, ADP, ATP, phosphoenolpyruvate, AMP, and succinic acid) exhibited both high predictive (t-VIP) and orthogonal (o-VIP) scores in the OPLS model. These metabolites are tightly connected in central energy metabolism pathways such as glycolysis, TCA cycle, and nucleotide metabolism, suggesting a tightly coordinated metabolic shift in POAG. While high t-VIP scores highlight their importance in group separation, elevated o-VIP values may reflect biological heterogeneity due to limited sample size or systematic variation unrelated to the disease classification. This orthogonal variance could arise from latent metabolic subtypes, adaptive metabolic rewiring, or early-stage compensatory mechanisms. Importantly, the strong correlations and clustering patterns observed among these metabolites support a coherent biological signal rather than technical artifacts. These findings underscore the metabolic complexity underlying POAG and highlight the need for integrative interpretation of multivariate modeling outputs in biomarker discovery.

In regulated biochemical networks, reaction fluxes are as informative as metabolite concentrations, particularly within well-characterized metabolic pathways. We observed elevated concentrations of several metabolites upstream in glycolysis and purine metabolism, while decreased levels appeared midstream in glycolysis and the urea cycle (Fig. 5A). These findings suggest a production-uptake imbalance and impaired metabolic conversion or clearance, leading to a bottleneck effect in these pathways. A buildup of intermediates indicates the presence of a bottleneck, where certain enzymes in glycolysis or purine metabolism may be inhibited, potentially due to genetic mutations, post-translational modifications, or external inhibitors. Flux analysis confirmed this hypothesis, revealing markedly decreased fluxes in glycolysis, the TCA cycle, and the urea cycle (Fig. 5C). Mitochondrial defects, such as Complex I dysfunction, have been consistently reported in glaucoma (including lymphoblasts, TM cells, and RGCs), leading to diminished ATP production, increased ROS, and oxidative damage in RGCs and trabecular meshwork23.

Similar disruptions in energy metabolism have been reported in glaucoma animal models. RGCs are particularly active in metabolism and vulnerable to energy insufficiency24. For example, elevated glucose and G6P in retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) of DBA2J mice and BN rats under high IOP conditions coincide with findings in the tears and plasma of POAG patients12,13,25. These accumulations, often associated with poor outcomes in brain injury and neurodegenerative diseases26,27, may reflect mitochondrial remodeling and reduced cristae density28. This aligns with our findings that G6P levels are highly elevated.

The accumulation of purine metabolites such as ATP and ADP also point to an increased energy demand in POAG, likely exceeding ATP generation capacity by mitochondria, which is common under oxidative stress, hypoxia, or mitochondrial dysfunction conditions. Despite the elevations in FBP, 6PGA, R5P, AMP, ADP and ATP, reduced flux ratios involving ATP and NAD (e.g., FBP/G6P, 6PGA/G6P) further imply high ATP demand and mitochondrial dysfunction in glaucoma patients. Feedback mechanisms regulate energy metabolism by sensing metabolic changes and adjusting enzyme activity. Elevated energy demand further amplifies disruptions in metabolic and energy supply pathways. Interestingly, key metabolites supporting energy homeostasis, including BPG, arginine, citrulline and G3P were also disrupted in POAG patients. For example, The 2,3-BPG pathway is critical in supporting the balance of ATP generation for metabolism and hemoglobin’s oxygenation/deoxygenation status by enhancing hemoglobin deoxygenation29.

Decreased ratios of urea cycle metabolites in POAG patients, such as citrulline/ornithine and arginine/ASA, suggest a disruption in ATP-dependent urea cycle and impaired nitrogen disposal in POAG. This disruption may contribute to increased IOP and inflammation. Additionally, this arginine deficiency is suggested to be the result of a decreased arginine uptake and an impaired arginine de novo synthesis from citrulline, in combination with an enhanced arginine catabolism by the upregulation of arginase and the inflammatory nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in the immune response30, thus leading to chronic inflammation30.

G3P, a key intermediate at the intersection of several metabolic pathways, has gained interest as a critical regulator of cellular energy31,32. In the current study, reduced G3P/DHAP ratio in POAG was observed, which could inhibit the Glycerol-3-phosphate shuttle, potentially reducing mitochondrial efficiency and ATP production. Furthermore, as G3P initiates the glycerolipid/free fatty acid (GL/FFA) cycle, which is essential for energy homeostasis. Reduced G3P could increase the reliance on fatty acid oxidation for energy, often seen during periods of fasting, chronic stress, or metabolic dysfunction31,33. Altered lipid metabolism, including dysregulated fatty acid profiles and lipid peroxidation, can contribute to cellular injury and RGC apoptosis34.

Elevated pEtN which is critical for cell division, membrane integrity, and mitochondrial respiratory function35 was also observed in POAG. The accumulation of pEtN has been observed in senescence cells32 and frail older adult36. pEtN has also been proposed to inhibit mitochondrial activity through competition with succinate at complex II (or succinate dehydrogenase) of the mitochondrial respiratory chain37. Consequently, elevated pEtN levels in POAG in the present study might suggest mitochondrial dysfunction and chronic inflammation.

A notable finding in POAG was the accumulation of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and the low PYR/PEP ratio. Pyruvate kinase activity regulates PEP-to-PYR conversion, a rate-limiting step that generates ATP and fuels the TCA cycle, enabling further ATP synthesis. Decreased conversion may lead to energy imbalances. Pyruvate (PYR) can be derived from various carbon sources and amino acids, and its supplementation has been shown to protect against neurodegeneration in animal models of glaucoma12. Moreover, PEP can convert to oxaloacetate, and its accumulation could create bottlenecks in the TCA cycle. Genetic mutations or pharmacological inhibition affecting enzymes like PCK2 may contribute to this imbalance38,39.

Another interesting finding is the reduced fumarate/succinate ratio in the TCA cycle in POAG patients, suggesting succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) dysfunction and possible disruption in mitochondrial Complex II activity40,41. This fumarate impairment may also be a downstream effect of disrupted tyrosine catabolism. Since fumarate can be produced from tyrosine, a precursor for neurotransmitters, its dysregulation could significantly impact neurotransmission.

In conclusion, the energy metabolism profile in the plasma of POAG patients in the present study suggest mitochondrial dysfunction, hypoxia and metabolic flux disruptions as potential contributors to POAG pathology. These findings underscore the need for larger multi-center studies to extend the observations so as to unveil the puzzle of the energy metabolism mechanism underlying POAG as we realize that we have limitations as the sample size in the present study is small so that the results may not be able to generalize to all. Besides, metabolomics can be very sensitive, which may be affected by patients’ systematic status and particularly diet. Although we set up very strict exclusion criteria to exclude patients with systematical diseases and collect all the plasma in fixed time range, there might still be some variances. Nevertheless, these findings enhance the current understanding of energy metabolism in POAG and provide valuable insights into the energy metabolic landscape of POAG as well as potential therapeutic strategies in the future.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Eye & ENT Hospital of Fudan University (Shanghai, China) and conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment in the research.

Study participants

Individuals were recruited from the Department of Ophthalmology in Eye & ENT Hospital of Fudan University. In metabolic phenotyping, there is currently no available approach for the estimation of sample size. Therefore, the sample size in the present study was estimated based on previous studies6,44. POAG was diagnosed by experienced ophthalmologists with the same criteria. The diagnostic criteria were: (1) intraocular pressure > 21 mmHg, (2) glaucomatous optic nerve damage with progressive optic disc cupping45, (3) open iridocorneal angles determined by gonioscope examination. Patients with isolated ocular hypertension, normal tension glaucoma, secondary glaucoma, previous glaucoma surgery including laser surgery, other ocular diseases, and systemic diseases including diabetes, renal diseases, cardiac disease and immune diseases have been excluded from our study. No previous intraocular surgery including cataract surgery was performed in the patients recruited in our study. Patients with POAG underwent ancillary tests including fundus photography, visual field testing (Humphrey field analyzer, SITA full-threshold programs 30 − 2; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA), retinal never fiber layer thickness, and ganglion cell complex evaluation using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (Avanti RTVue-XR, Optovue, CA). Controls were sex- and age-matched individuals undergoing cataract surgery at the same department of ophthalmology. The inclusion criteria for the control group were age-related cataract with no ocular conditions except for cataract. The exclusion criteria were family history of glaucoma, ocular hypertension, retinal disorders and any ocular surgery. All the patients recruited in the study were above 40 years old.

Sample collection

The blood was collected in the fixed time range (8am-12pm) one day prior to the surgery when patients were admitted to the hospital. Each participant provided a single blood sample during this time window to ensure consistency in circadian-related variations. Blood samples from participants were collected in heparin tubes at least six hours after the last meal. The tubes were immediately transported on ice and immediately processed for centrifugation for 10 min at 3000 g at 4 °C. Then the supernatant was collected and immediately stored at − 80 °C until metabolomic analysis.

Targeted metabolomics detection

The preparation of samples, extract analysis, metabolite identification and quantification were performed in MetWare Biotechnology Co., Ltd. following their standard procedures. Briefly, samples were thawed on ice and vortexed for 30 s to mix homogeneously, centrifuged at 3000 r/min for 5 min at 4 °C. 50 µL of the sample was transferred to a centrifuge tube, and mixed with 250 µL of 20% acetonitrile methanol, vortexed for 3 min, centrifuged at 11,304 g for 10 min at 4 °C. Take 250 µL of supernatant into a new centrifuge tube and placed in −20 °C refrigerator for 30 min, centrifuged at 11,304 g for 10 min at 4 °C. After centrifugation, transfer 180 µL of supernatant for further LC-MS analysis.

The sample extracts were analyzed using an LC-ESI-MS/MS system (UPLC, ExionLC AD; MS, QTRAP® 6500 + System). The analytical conditions were as follows, HPLC: column, ACQUITY UPLC BEH Amide (i.d.2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm); solvent system, water 10mM Ammonium acetate and 0.3% Ammonium hydroxide (A), acetonitrile with 90% ACN/water(V/V)(B); The gradient was started at 95% B (0–1.2 min), decreased to 70% B (8 min),50% B (9–11 min), finally ramped back to 95% B (11.1–15 min); flow rate, 0.4 mL/min; temperature, 40 °C; injection volume: 2 µL.

Linear ion trap (LIT) and triple quadrupole (QQQ) scans were acquired on a triple quadrupole-linear ion trap mass spectrometer (QTRAP), equipped with an ESI Turbo Ion-Spray interface, operating in positive and negative ion mode and controlled by Analyst 1.6 software (Sciex).

The ESI source operation parameters were as follows: ion source, turbo spray; source temperature 550 °C; ion spray voltage (IS) 5500 V(Positive), −4500 V(Negative); curtain gas (CUR) were set at 35.0 psi; DP and CE for individual MRM transitions was done with further DP and CE optimization. A specific set of MRM transitions were monitored for each period according to the energy metabolism eluted within this period. Pooled standards solution was used as the QC, and instrument stability was assessed by overlaying the TICs from repeated QC runs. Standards were used to confirm the identity of metabolites based on the self-built target standard database MWDB (metware database) by widely target UPLC-MS/MS platform of Metware Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Analysis of mass spectrometric data was conducted based on the Metware database (MWDB) and the analysis of raw mass spectrometry data was processed using Analyst 1.6.3 software (AB Sciex). Identification was achieved based on standard compounds and their characteristic ion pairs (Q1/Q3) along with retention times (RT) in accordance with Level 1 identification criteria of the Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI)1. Quality criteria in this study include: R2 > 0.99, accuracy 80–120%, retention time shift < 0.1 min, precision (CV%) < 30% as well as S/N ratio > 10.

Data processing and statistical analysis

Univariate analysis of clinical quantitative data was performed with parametric test (Welch’s t-test) or nonparametric test (Wilcoxon-Mann Whitney test) according to the normality assessed by Shapiro Wilk’s test. Analysis of clinical qualitative gender data was performed with Fisher’s exact test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistics univariate analyses of DEMs was processed with non-parametric rank test. Orthogonal Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis(orthoPLS-DA), non-parametric Significance Analysis of Metabolites(SAM) with Delta = 1.25, non-parametric Empirical Bayesian Analysis of Metabolites(EBAM) with Delta = 0.95 and Spearman correlation analysis was conducted using MetaboAnalyst v6.0 (www.metaboanalyst.ca46. The data were processed by log transformation and auto scaling. The Debiased Sparse Partial Correlation (DSPC) network analysis with raw p-cutoff < 0.1 was conducted using MetaboAnalyst v6.0. The Flux(ratio) analysis was done with python 3. t-score was calculated for each flux. t-score > 2 (equals to p < 0.05) was considered significant.

Data availability

The raw data of metabolomics in all participants has been deposited at Mendeley Data (data.mendeley.com/datasets/tybzw7zsng/1). All other supporting data are included in the manuscript and files.

References

Quigley, H. A. & Broman, A. T. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 90 (3), 262–267 (2006).

Zhang, N. et al. Prevalence of primary angle closure glaucoma in the last 20 years: A Meta-Analysis and systematic review. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 7, 624179 (2020).

Bhattacharya, S. K. et al. Molecular biomarkers in glaucoma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54 (1), 121–131 (2013).

Funke, S. et al. Glaucoma Relat. Proteomic Alterations Hum. Retina Samples Sci. Rep., 6: 29759. (2016).

Shiga, Y. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies seven novel susceptibility loci for primary open-angle glaucoma. Hum. Mol. Genet. 27 (8), 1486–1496 (2018).

Tang, Y. et al. Metabolomics in primary open angle glaucoma: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Neurosci. 16, 835736 (2022).

Kouassi Nzoughet, J. et al. A data mining metabolomics exploration of glaucoma. Metabolites 10 (2), 49 https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo10020049 (2020).

Myer, C. et al. Differentiation of soluble aqueous humor metabolites in primary open angle glaucoma and controls. Exp. Eye Res. 194, 108024 (2020).

Edwards, G. et al. Phospholipid profiles of control and glaucomatous human aqueous humor. Biochimie 101, 232–247 (2014).

Buisset, A. et al. Metabolomic profiling of aqueous humor in glaucoma points to taurine and spermine deficiency: findings from the Eye-D study. J. Proteome Res. 18 (3), 1307–1315 (2019).

Barbosa Breda, J. et al. Metabolomic profiling of aqueous humor from glaucoma patients - The metabolomics in surgical ophthalmological patients (MISO) study. Exp. Eye Res. 201, 108268 (2020).

Harder, J. M. et al. Disturbed glucose and pyruvate metabolism in glaucoma with neuroprotection by pyruvate or Rapamycin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 117 (52), 33619–33627 (2020).

Botello-Marabotto, M. et al. Tear metabolomics for the diagnosis of primary open-angle glaucoma. Talanta 273, 125826 (2024).

Burgess, L. G. et al. Metabolome-Wide association study of primary open angle glaucoma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 56 (8), 5020–5028 (2015).

Gong, H. et al. The profile of gut microbiota and central carbon-related metabolites in primary angle-closure glaucoma patients. Int. Ophthalmol. 42 (6), 1927–1938. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-021-02190-5(2022).

Wu, X. et al. Dysregulated energy metabolism impairs chondrocyte function in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 31 (5), 613–626 (2023).

Su, G. et al. Enteric coronavirus PDCoV evokes a non-Warburg effect by hijacking pyruvic acid as a metabolic hub. Redox Biol. 71, 103112 (2024).

Xie, Z. et al. Integration of proteomics and metabolomics reveals energy and metabolic alterations induced by glucokinase (GCK) partial inactivation in hepatocytes. Cell. Signal. 114, 111009 (2024).

Tang, Y. et al. Nicotinamide ameliorates energy deficiency and improves retinal function in Cav-1. J. Neurochem. 157 (3), 550–560 (2021).

Williams, P. A. et al. Vitamin B3 modulates mitochondrial vulnerability and prevents glaucoma in aged mice. Science 355 (6326), 756–760 (2017).

Leruez, S. et al. A metabolomics profiling of glaucoma points to mitochondrial dysfunction, senescence, and polyamines deficiency. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 59 (11), 4355–4361 (2018).

Molnos, S. et al. Metabolite ratios as potential biomarkers for type 2 diabetes: a DIRECT study. Diabetologia 61 (1), 117–129 (2018).

He, Y. et al. Mitochondrial complex I defect induces ROS release and degeneration in trabecular meshwork cells of POAG patients: protection by antioxidants. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 49 (4), 1447–1458 (2008).

Liu, H. & Prokosch, V. Energy metabolism in the inner retina in health and glaucoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (7), 3689.https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22073689 (2021).

Cimaglia, G. et al. Oral nicotinamide provides robust, dose-dependent structural and metabolic neuroprotection of retinal ganglion cells in experimental glaucoma. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 12 (1), 137 (2024).

An, Y. et al. Evidence for brain glucose dysregulation in alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 14 (3), 318–329 (2018).

Shi, J. et al. Review: traumatic brain injury and hyperglycemia, a potentially modifiable risk factor. Oncotarget 7 (43), 71052–71061 (2016).

Dlasková, A. et al. 3D super-resolution microscopy reflects mitochondrial Cristae alternations and MtDNA nucleoid size and distribution. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1859 (9), 829–844 (2018).

Mulquiney, P. J. & Kuchel, P. W. Model of 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate metabolism in the human erythrocyte based on detailed enzyme kinetic equations: computer simulation and metabolic control analysis. Biochem. J. 342 (Pt 3), 597–604 (1999).

Wijnands, K. A. et al. Arginine and citrulline and the immune response in sepsis. Nutrients 7 (3), 1426–1463 (2015).

Mugabo, Y. et al. Identification of a mammalian glycerol-3-phosphate phosphatase: role in metabolism and signaling in pancreatic β-cells and hepatocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 113 (4), E430–E439 (2016).

Tighanimine, K. et al. A homoeostatic switch causing glycerol-3-phosphate and phosphoethanolamine accumulation triggers senescence by rewiring lipid metabolism. Nat. Metab. 6 (2), 323–342 (2024).

Possik, E. et al. New mammalian Glycerol-3-Phosphate phosphatase: role in β-Cell, liver and adipocyte metabolism. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 12, 706607 (2021).

Ana, R. D. et al. Precision medicines for retinal lipid Metabolism-Related pathologies. J. Pers. Med., 13 (4), 635.https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13040635 (2023).

St Germain, M., Iraji, R. & Bakovic, M. Phosphatidylethanolamine homeostasis under conditions of impaired CDP-ethanolamine pathway or phosphatidylserine decarboxylation. Front. Nutr. 9, 1094273 (2022).

Rashidah, N. H. et al. Differential gut microbiota and intestinal permeability between frail and healthy older adults: A systematic review. Ageing Res. Rev. 82, 101744 (2022).

Fontana, D. et al. ETNK1 mutations induce a mutator phenotype that can be reverted with phosphoethanolamine. Nat. Commun. 11 (1), 5938 (2020).

Xu, M. et al. A novel mutation in PCK2 gene causes primary angle-closure glaucoma. Aging (Albany NY). 13 (19), 23338–23347 (2021).

Waygood, E. B., Mort, J. S. & Sanwal, B. D. The control of pyruvate kinase of Escherichia coli. Binding of substrate and allosteric effectors to the enzyme activated by Fructose 1,6-bisphosphate. Biochemistry 15 (2), 277–282 (1976).

Hass, D. T. et al. Succinate metabolism in the retinal pigment epithelium uncouples respiration from ATP synthesis. Cell. Rep. 39 (10), 110917 (2022).

Bisbach, C. M. et al. Succinate can shuttle reducing power from the hypoxic retina to the O. Cell. Rep. 31 (5), 107606 (2020).

Tang, Y. et al. Metabolomic profiling of aqueous humor and plasma in primary open angle glaucoma patients points towards novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategy. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 621146 (2021).

Rossi, C. et al. Multi-Omics approach for studying tears in Treatment-Naïve glaucoma patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (16), 4029.https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20164029 (2019).

Pan, C. W. et al. Differential metabolic markers associated with primary open-angle glaucoma and cataract in human aqueous humor. BMC Ophthalmol. 20 (1), 183 (2020).

Jonas, J. B. et al. Glaucoma Lancet, 390(10108): 2183–2193. (2017).

Chong, J. et al. MetaboAnalyst 4.0: towards more transparent and integrative metabolomics analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 46 (W1), W486–W494 (2018).

Funding

This work was supported by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7232025), Beijing Hospitals Authority Youth Programme (QML20230203), Clinical Research Plan of SHDC (SHDC2020CR6029), PloyU Internal Grant(1-YWC5) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.82201174 and No.82203375). The authors declared no conflict of interest and no financial disclosures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: XHS, YZT; Methodology: YZT, JYL, MYX, QRW; Formal analysis and investigation: YZT, XQZ, XXC, YHZ; Writing: YZT, XQZ; Funding acquisition: XHS, YZT, CWD, MYX; Resources: XHS; Supervision: XHS, CWD.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, Y., Zhang, X., Chen, X. et al. Targeted LC-MS profiling reveals dysregulated glycolytic flux and TCA cycle stalling in POAG plasma. Sci Rep 15, 34212 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15836-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15836-6