Abstract

Vehicle re-identification (Re-ID) has become a challenging retrieval task due to the high inter-class similarity and low intra-class similarity among vehicles. To address this challenge, the self-attention mechanism has been extensively studied and applied, demonstrating its effectiveness in capturing long-range dependencies in vehicle Re-ID. Traditional spatial self-attention and channel self-attention assign different weights to each node (position/channel) based on pairwise dependencies at a global scale to model long-term dependencies, but this approach is not only computationally complex but also unable to fully mine refined features. In this paper, we propose a vehicle Re-ID network design based on a multi-axis compression fusion (MCF) attention mechanism. The MCF attention mechanism preserves feature information on different axes through compression operations while maintaining high computational efficiency. It utilizes single-axis self-attention calculations to update the weights and strengthens the regions of common interest across multiple axes by fusing information from multiple axes, thereby enhancing the effect of attention learning. On the basis of this mechanism, we propose a multi-axis compression fusion network (MCF-Net), which combines the spatial multi-axis compression fusion (S-MCF) module and the channel multi-axis compression fusion (C-MCF) module, and uses a rigid partitioning strategy to capture both global and fine-grained features. Experiments show that MCF-Net achieves state-of-the-art performance on the vehicle Re-ID datasets VeRi-776 and VehicleID.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vehicle re-identification (Re-ID)1,2,3,4,5 aims to match the same vehicle across multiple cameras, holding vast application potential in real-world scenarios. In recent years, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have made significant breakthroughs in various computer vision fields, covering tasks such as image classification6,7,8,9,10, semantic segmentation11,12,13,14 and Re-ID15,16,17,18,19,20. In vehicle Re-ID tasks, CNN-based approaches have dominated scenes, and researchers have designed a variety of CNN-based vehicle Re-ID architectures21,22,23 to enhance the effectiveness of vehicle Re-ID tasks. Despite notable advancements in vehicle Re-ID tasks, two major challenges remain: high inter-class similarity and low intra-class similarity. The former refers to high similarity in the appearance of different vehicles due to many similar attributes (colors, shapes, etc.) present among different vehicles, whereas the latter denotes high variation in the appearance of the same vehicle from different viewpoints or with different occlusions. These two challenges pose strict requirements for building robust vehicle Re-ID networks.

To address the above problems, many vehicle Re-ID methods24,25,26,27,28,29, such as keypoint detection and parsing networks, rely on auxiliary models to locate important cues. Wang et al.25 labeled 20 keypoints on each vehicle image in order to facilitate the extraction of local features. Zhu et al.26 used the YOLOV model to precisely locate regions that cover key details, such as windshields and headlights. However, implementation of these methods requires the assistance of additional models and labeled data, which are less efficient and cannot be adapted to real-world scenarios. In recent years, attention mechanisms10,30,31,32 have had an increasingly significant impact on various types of visual tasks, and these dynamic, adaptive mechanisms allow models to assign different weights according to the importance of features, improving efficiency and model performance.

Among the various types of attention mechanisms, the self-attention mechanism33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40 represents a unique approach that computes weighted sums of features at the global scale on the basis of pairwise dependencies to update the weights of each node (location/channel) for modeling long-range dependencies. Models based on self-attention mechanisms generate a global context by exploring interdependencies along spatial33,38,39,40 or channel dimensions35,37. We describe these two types of self-attention mechanisms as spatial self-attention (S-SA) and channel self-attention (C-SA). S-SA establishes pairwise dependencies between the query location and all other locations through dot product operations, forming an attention map. It then utilizes the weights derived from this attention map to aggregate the features of all locations through weighted sums. Finally, the aggregated feature vectors are added to the features of each query location to generate the final output. Unlike S-SA, C-SA focuses instead on pairwise dependencies between different channels. ViT38 mapped non-overlapping image blocks into tokens and used S-SA to establish long-range dependencies between them, demonstrating excellent performance. Maaz et al.37 used C-SA to apply dot product operations to the entire channel dimension instead of the spatial dimension, allowing the model to learn pairwise relationships between different channels to implicitly model the global context. However, traditional S-SA and C-SA not only are computationally complex but also fail to adequately mine refined features. When performing S-SA computation, it is necessary to calculate the similarity between the query vector at each position and the key vectors at all other positions, which leads to a complexity that is directly proportional to the square of locations. The computational complexity of C-SA is still high, although it exhibits a linear relationship with locations.

This paper introduces a novel attention mechanism dubbed multi-axis compression fusion (MCF). Specifically, the mechanism first obtains the robust feature responses of each row of elements on each channel through the horizontal direction compression operation, whereas the vertical direction compression operation generates the robust feature responses of each column of elements on each channel. Second, we update the weights via parallel self-attention computations in individual axis directions, which greatly reduces the complexity and mines the refined features in different directions while modeling the global context. Next, fusing the attention graphs of multiple axes aggregates feature information and strengthens the features of common interest on multiple axes to enhance the effect of attention learning. On the basis of this attention mechanism, we design two attention modules from spatial and channel aspects: the spatial multi-axis compression fusion (S-MCF) module and the channel multi-axis compression fusion (C-MCF) module. The S-MCF module focuses on the dependencies between the same coordinates of the positions in different directions when performing the attention computation. The C-MCF module focuses on the dependencies between channels when performing self-attention computations. We introduce the above two dimensions of the attention module into the CNN and propose the multi-axis compression fusion network (MCF-Net). The network consists of a global branch, a spatial branch and a channel branch. The global branch is used to learn the global features of the input image, and the spatial and channel branches utilize an attention module and a rigid partitioning strategy to extract subtle distinguishing details within vehicle imagery.

To conclude, the principal achievements presented in this paper are as follows:

-

(1)

We propose a novel MCF attention mechanism that retains global information on different axes through compression operations in different directions and performs self-attention computations on a single axis, which greatly reduces the computational complexity of traditional S-SA and C-SA and mines fine-grained features in different directions while modeling the global context.

-

(2)

We propose MCF-Net by combining the S-MCF module, C-MCF module and rigid partitioning strategy. It enhances the representation of key features through attention mechanism, while fusing attention information from different directions (vertical and horizontal) to capture both comprehensive and nuanced features.

-

(3)

We undertake extensive evaluations on the VehicleID and VeRi-776 datasets, revealing that MCF-Net model surpasses existing benchmarks while adeptly addressing the intricacies of large intra-class variations and small inter-class differences in vehicle Re-ID.

Related work

Vehicle Re-ID

In recent years, vehicle Re-ID has gained growing popularity in the field of computer vision. Some studies21,22,23 have used CNNs to learn the features of vehicle images. However, high inter-class similarity and low intra-class similarity remain challenging problems in vehicle Re-ID tasks. To enhance the performance of vehicle Re-ID networks, existing approaches24,25,26,29,41,42,43,44 employed auxiliary models including keypoint detection and parsing networks to extract discriminative features. Wang et al.25 used the locations of 20 vehicle keypoints to extract local features from various distinct regions within the images. Zhou et al.41 proposed a viewpoint-aware inference network to capture local features shared across viewpoints. Tang et al.42 inferred the attitude and shape of a target vehicle from keypoints and heatmaps. He et al.43 proposed a detection network branch to localize several key parts. Khorramshahi et al.29 adopted a two-stage model to predict the keypoints and orientations of vehicles, and then leveraged orientation cues to select the most salient keypoints for extracting discriminative features. Khorramshahi et al.44 employed a self-supervised residual generation module to produce vehicle samples devoid of detailed features and then subtracted them from the original vehicle samples to obtain discriminative detail information. Meng et al.24 introduced a parsing network that utilizes image segmentation techniques to dissect vehicle images into distinct viewpoints, subsequently representing the vehicles at a fine-grained level to mitigate the differences among vehicles. Zhu et al.26 proposed two parallel self-attention modules to locate critical regions in vehicle images, with the aim of extracting discriminative features.

However, these approaches suffer from inefficiency, high costs, and lengthy processing times because they rely on auxiliary models to localize the key regions while providing only limited and coarse detail information. In contrast to the above methods, the MCF-Net proposed in this paper uniquely identifies critical regions in vehicle images solely based on identity labels, without the reliance on additional models, and concurrently reduces computational complexity through its single-axis self-attention mechanism.

Attention mechanism

Since the attention mechanism is able to focus on important parts of the input data to improve the overall performance and efficiency of the network, it has been widely used in several fields, including image classification6,7,8,9,10,45,46,47, target detection48, semantic segmentation24,25,26,49, Re-ID15,16,17,18,19,20,50,51, and remote sensing image processing52,53,54. In the field of computer vision, attention mechanisms are mainly classified into two categories: channel attention and spatial attention, of which SENet32 and CBAM55 represent typical implementations of these two types of attention, respectively. SENet proposed by Hu et al.32 dynamically adjusts the weights of different channels through squeeze-excitation operation to focus on important feature channels while suppressing unimportant information. However, it only focuses on the channel dimension and ignores the modeling of the spatial dimension. To model spatial dimensional information, CBAM proposed by Woo et al.55 models both channel and spatial dimensions of attention, allowing the network to focus more precisely on key feature areas. Based on these two foundation studies, subsequent works have proposed further improvement methods. Li et al.45 first extracted multi-level local features by hierarchically sampling input feature maps at multiple scales. They then applied channel attention to model inter-channel correlations and spatial attention to capture location importance, finally integrating multi-scale features for richer discriminative representations. Jiao et al.51 preserved spatial information by compressing it into channel representations, then applied channel attention to enhance discriminative channels while suppressing background-related ones. CADANet54 proposed an attribute feature aggregation module and a contextual attribute-aware spatial attention module. These modules reduce intra-class feature inconsistencies through global and local context aggregation, while modeling long-range dependencies and mitigating inter-class differences by fusing pixel-level global context with relative location information.

The self-attention mechanism is a specialized form of attention mechanism that has received widespread attention and application in various fields, including natural language processing56,57,58. The key concept is to compute the affinity between the features to capture the long-range dependencies. The self-attention mechanism is mainly categorized into S-SA and C-SA, where S-SA focuses on the dependencies between different locations at the global scale and C-SA focuses on the global dependency relationships between different feature channels. S-SA is a core part of many transformer models, and the ViT architecture proposed by Dosovitskiy et al.38 achieves competitive performance. DeiT model59, which also has S-SA at its core, introduced integrated distillation tokens in the ViT architecture to significantly reduce the pre-training time. The idea of splitting depth-wise transpose attention blocks via C-SA introduced by Maaz et al.37 has shown excellent performance on many visual tasks. However, traditional S-SA and C-SA have non-negligible disadvantages. First, due to the fact that S-SA requires computing pairwise dependencies between every position and every other position in the input sequence, its computational complexity is proportional to the square of the number of positions in the input sequence. Compared with the complexity of S-SA, the complexity of C-SA, despite its linear relationship with the number of locations, still cannot satisfy the requirements of visual tasks. Second, although S-SA and C-SA can model the long-range dependencies between nodes, they cannot mine the fine-grained features.

In this paper, our proposed MCF attention mechanism uses horizontal and vertical compression operations to obtain robust feature responses in the row and column directions on each channel, retains the global information on different axes, and then updates the weights via self-attention computations to mine the fine-grained features in different directions while modeling the global context. Compared with traditional S-SA and C-SA, the single-axis parallel self-attention computation method significantly reduces complexity. On the other hand, we aggregate feature information and reinforce regions of common interest on multiple axes by fusing the attention maps of multiple axes to enhance the effect of attention learning.

Method

In this section, we provide a comprehensive overview of the proposed MCF-Net. Firstly, we introduce the designed S-MCF and C-MCF modules, then introduce the holistic architecture of the MCF-Net, and finally, discuss the loss function.

S-MCF module

The S-MCF module’s structure is illustrated in Figure 1. The S-MCF module first obtains the robust feature responses of each row element and each column element on each channel through compression operations in different directions. Second, after self-attention computation, the S-MCF module generates the dependencies between the same coordinates at each position to mine the refined features while modeling the global context of different axes. Finally, the spatial aspects of the vertical and horizontal directions of attention are fused to aggregate feature information and strengthen the features of common concern on different axes to amplify the effectiveness of attention mechanism.

Taking the output feature map \(F \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H \times W}\) of the res_conv5 layer as input, F obtains feature maps \(Q_s \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H \times W}\) through a 2D convolution with a convolution kernel of size 1 and through group convolution to obtain \(K_s \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H \times W}\) and \(V_s \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H \times W}\).

1DConv denotes a 1\(\times\)1 convolution, and GConv denotes group convolution. Group convolution divides the input feature map into multiple groups, performing convolution within each, allowing weights sharing. This effectively reduces the number of parameters and improves computational efficiency. We achieve feature map horizontal compression by taking the average of the above three feature maps in the horizontal direction to obtain feature maps \(Q_{s}^{h} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H \times 1}\), \(K_{s}^{h} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H \times 1}\), and \(V_{s}^{h} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H \times 1}\), which are deformed to obtain the matrices \(Q_{s}^{h'} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{H \times C}\), \(K_{s}^{h'} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H}\), and \(V_{s}^{h'} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{H \times C}\).

Similarly, the feature maps \(Q_{s}^{v} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times 1 \times W}\), \(K_{s}^{v} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times 1 \times W}\), and \(V_{s}^{v} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times 1 \times W}\) are obtained by computing the average of the three feature maps in the vertical direction, which is deformed to obtain the matrices \(Q_{s}^{v'} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{W \times C}\), \(K_{s}^{v'} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times W}\), and \(V_{s}^{v'} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{W \times C}\).

The products of matrices \({Q_{s}^{h'}}\) and \({K_{s}^{h'}}\) are calculated, the spatial vertical axis relationship matrix \(X_{s}^{h} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{H \times H}\) is derived by employing the softmax activation function, and each row of \({X_{s}^{h}}\) represents the relationship between a certain position and other H positions. Next, a weighted summation with matrix \(V_{s}^{h'}\) is performed to obtain the spatial vertical axis attention map \(P_{s}^{h} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{H \times C}\), which is calculated as follows:

where \(\otimes\) denotes matrix multiplication, the columns of the matrix \(X_{s}^{h}\) are normalized using the softmax function, and \(d_{c}\) is the scaling factor.

Similarly, each row in the spatial horizontal axis relationship matrix \(X_{s}^{v} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{W \times W}\) represents the relationship of a particular location to the other W locations, and the spatial horizontal axis attention map \(P_{s}^{v} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{W \times C}\) is denoted as follows:

The traditional self-attention mechanism needs to compute the relationship between query vectors and key vectors for all positions, resulting in a computational complexity that is squarely proportional to the number of positions. The S-MCF module propagates the information over only two compressed axial features; thus, the computational complexity is relatively low. Separating the attention computation in the vertical and horizontal directions allows for more parallelized operations and therefore improves the computational efficiency to some extent.

Single-direction attention may ignore or weaken the information in other directions, whereas multi-direction fusion can alleviate the limitation of single-direction attention and utilize the relevant information in images more comprehensively. After obtaining the spatial vertical axis attention map and the spatial horizontal axis attention map, we broadcast them to \({H \times W \times C}\) dimensions and fuse them to obtain the spatial multi-axis fusion attention map \(A\in {\mathbb {R}}^{H \times W \times C}\). This process is calculated as follows:

where \(\oplus\) denotes element-by-element addition. Attention map A not only contains information from multiple axes but also, by summing and fusing the attention maps of multiple axes, can strengthen the regions of common attention on multiple axes, regard these regions as more important features and help improve the ability of the model to recognize and use key information.

The attention map A is deformed and masked onto the input feature map F, and the result is summed with F to produce \(W_{s} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H \times W}\). Then, batch normalization (BN) and the gaussian error linear unit (GELU) activation function are implemented sequentially to obtain the final output feature map \(R_{s} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H \times W}\). This process is calculated as follows:

where \(\odot\) represents element-wise multiplication.

C-MCF module

The C-MCF module obtains the robust feature response of each row element and each column element on each channel separately after performing compression operations in different directions. Unlike the S-MCF module, the C-MCF module performs C-SA computations on different axes separately to obtain the dependencies of each channel with other channels in different directions. Finally, the vertical attention and horizontal attention on the channel side are fused to infer the importance of the channel. Its structure is shown in Figure 2.

The input feature map \(F \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H \times W}\) is passed through a 2D convolution with a kernel size of 1 to obtain the feature map \(Q_{c} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H \times W}\), and through group convolution to obtain \(K_{c} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H \times W}\) and \(V_{c} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H \times W}\).

Next, we take the average of the above feature maps in the horizontal direction to obtain the feature maps \(Q_{c}^{h} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H \times 1}\), \(K_{c}^{h} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H \times 1}\), and \(V_{c}^{h} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H \times 1}\), which are deformed to obtain the matrices \(Q_{c}^{h'} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H}\), \(K_{c}^{h'} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{H \times C}\), and \(V_{c}^{h'} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{H \times C}\).

Similarly, the three feature maps deformed by vertical compression yield the matrices \(Q_{c}^{v'} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times W}\), \(K_{c}^{v'} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{W \times C}\), and \(V_{c}^{v'} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{W \times C}\).

After matrix multiplication and use of the softmax activation function, the vertical axis relationship matrix \(X_{c}^{h} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times C}\) of the channel and the horizontal axis relationship matrix \(X_{c}^{v} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times C}\) of the channel are obtained. Unlike the S-MCF module, the C-MCF module is designed to capture the relationships between channels in different directions. The element \(X_{i,j}\) at position (i, j) of the relationship matrix represents the correlation between channels i and j. The \(i \text {-th}\) row of matrix \(X_{i,*}\) indicates the relationship between each and to the \(i \text {-th}\) channel. Although the two \(C \times C\) matrices are identical in size, they have different meanings. \(X_{c}^{h}\) reflects the correlation between channels in the feature map in the horizontal direction, whereas \(X_{c}^{v}\) reflects the correlation between channels in the feature map in the vertical direction.

\(X_{c}^{h}\) and \(X_{c}^{v}\) are weighted and summed with matrices \(V_{c}^{h'}\) and \(V_{c}^{v'}\), respectively, to obtain the vertical axis attention map of the channel \(P_{c}^{h} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{H \times C}\) and the horizontal axis attention map of the channel \(P_{c}^{v} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{W \times C}\), which are computed as follows:

After the channel vertical axis attention map and the channel horizontal axis attention map are obtained, we broadcast them to \({H \times W \times C}\) dimensions and the two are fused to obtain the multi-axis fusion attention map \(B\in {\mathbb {R}}^{H \times W \times C}\) of the channel. This process is calculated as follows:

where \(\oplus\) denotes element-by-element addition. The attention map B is deformed and masked onto the input feature map F, and the result is summed with F to produce \(W_{c} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H \times W}\). The final output feature map \(R_{c} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{C \times H \times W}\) is obtained by sequentially implementing the BN and GELU activation functions in succession. This process is calculated as follows:

Overall network structure

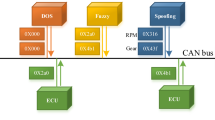

As shown in Figure 3, MCF-Net consists of the ResNet-5060 backbone and three independent branches. Specifically, we divide the portion after res_conv4_1 into three branches and remove the downsampling operation of the res_conv5_1 residual block to maintain high spatial resolution. These three branches are the global branch, spatial branch and channel branch.

Schematic diagram of the overall network structure. S-MCF represents the spatial multi-axis compression fusion module, while C-MCF stands for the channel multi-axis compression fusion module. Reduce refers to the dimensionality reduction operation, and GAP denotes global average pooling. The reduced-dimensional features from the three branches are concatenated to form the final feature in the testing phase.

The global branch is used to learn the global features of the input images. We first condense the output features of the global branch through a global average pooling (GAP) operation, yielding a 2048-dimensional feature vector. Then, we perform dimensionality reduction of this feature vector by applying a 1\(\times\)1 convolution, BN layer and rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function and finally obtain a 256-dimensional feature vector. We add S-MCF and C-MCF modules after the res_conv5 layer in the spatial and channel branches, respectively. The spatial branch uses the S-MCF module to highlight important spatial locations, and the C-MCF module within the channel branch dynamically adjusts the weights of individual channels, enabling the extraction of crucial features. In addition, we use the rigid partitioning strategy to horizontally divide the final output feature maps of the spatial and channel branches into two parts, enabling the two branches to capture the fine-grained features within each image. The subsequent structure of the spatial branch and channel branch is the same as that of the global branch, and the feature maps after rigid partitioning are pooled and dimensionality-reduced to obtain 256-dimensional feature vectors. The 256-dimensional feature vectors obtained from each branch serve as inputs for the triplet loss training procedure and are transformed by the fully connected layer to be used for the training of cross-entropy loss.

Loss functions

To boost the model’s effectiveness, we leverage both cross-entropy loss and triplet loss for network training. Cross-entropy loss precisely directs the model to correctly classify inputs by associating them with their appropriate class labels. Conversely, triplet loss concentrates on refining the distances within the feature space to strengthen the discriminability and robustness of the features.

Cross-entropy loss function

Cross-entropy loss is one of the commonly used loss functions in vehicle Re-ID tasks and reflects the degree of discrepancy between the predictions and the true labels of the models. A lower cross-entropy loss usually indicates that the model predicts the data more accurately. The following formula expresses the cross-entropy loss:

where M denotes the total count of vehicles within the training set, y is the true identity label of the input image, \(p_{i}\) represents predicted probability that the input image is classified as class i, while \(q_{i}\) represents the target probability.

Triplet loss function

The core idea of triplet loss is in terms of three samples, including anchor points, positive samples, and negative samples. Minimizing the distance between anchor points and positive examples while maximizing the distance between anchor points and negative examples drives the network to learn better feature representations. In this paper, we use batch-hard triplet loss from61, which is expressed in the following formula:

where P and K denote the number of randomly selected vehicles from the training set and the number of images selected per vehicle, respectively. \(f_{a}^{(i)}\), \(f_{p}^{(i)}\), and \(f_{n}^{(j)}\) represent the features extracted from anchor points, positive samples, and negative samples, respectively. \(\alpha\) is a hyperparameter used to control the difference between interior distances. In all the experiments in this paper, we set \(\alpha\) to 1.2.

Total loss function

The total loss is the sum of the above two losses, expressed as follows:

where \(N=5\). \(\eta\) and \(\omega\) are two hyperparameters that balance the two loss terms. In this paper, we set both \(\eta\) and \(\omega\) to 1.

Experiment

To evaluate the efficacy of MCF-Net in vehicle Re-ID, we compared it with other state-of-the-art vehicle Re-ID methods on the VeRi-77662 and VehicleID63 datasets. Additionally, we performed extensive ablation studies to evaluate the impact of each component in MCF-Net on performance.

Datasets and evaluation protocols

VeRi-776

The VeRi-776 dataset contains over 50,000 images, encompassing 776 unique vehicle images captured under varying real-world conditions. Specifically, 37,778 images of 576 vehicles constitute the training set, while the remaining vehicle images are organized into the test set, which is further divided into query images and gallery images. These images were captured by 20 surveillance cameras spanning a 24-hour period. The dataset not only provides comprehensive global information on vehicles but also enhances its practicality and research value by incorporating annotations of keypoints and vehicle orientations.

VehicleID

The VehicleID dataset contains 221,763 images of 26,267 vehicles captured by real surveillance cameras. Among them, the images of 13,134 vehicles form the training set, while the remaining form the test set. The VehicleID dataset offers three test subsets of varying sizes for evaluating the performance on different data sizes. In addition, a total of 250 segmented vehicle model attributes and 7 color attributes are included in the VehicleID dataset.

Evaluation protocols

We choose the cumulative matching characteristic (CMC) curve and mean average precision (mAP) as evaluation metrics. The CMC curve measures the probability that, after sorting the database images by similarity to the query image, the top K results include images with the same identity as the query image. In this paper, we use the Rank-1 accuracy and Rank-5 accuracy as the evaluation metrics. On the other hand, mAP is an indicator that describes the precision and recall of all the retrieval results. Unlike the CMC curve, the mAP focuses more on the average performance of each class or query. It is obtained by first calculating the average precision (AP) for each query image, and then averaging the AP values across all query images.

where L signifies the total number of items in the resulting list. \(N_{gt}\) represents the count of images in the sorted list that have the same identity as the query. P(k) is the precision at cutoff point k. The indicator function gt(k) is 1 if the \(k\text {-th}\) image has the same identity as the query.

In the testing phase, the VeRi-776 dataset evaluates its performance through the image-to-track retrieval task, focusing on three core indicators: mAP, Rank-1 and Rank-5 accuracy. These indicators are used to measure the retrieval efficiency and accuracy of the method. The query images are composed of vehicle images selected by each camera, and the track is constituted by a sequence of multiple images of the same vehicle captured continuously by a single camera within a short period of time, in which the query images need to be compared with the target images to measure their similarity. For the VehicleID dataset, we evaluate the performance of MCF-Net in terms of Rank-1 accuracy and Rank-5 accuracy. All reported results represent averages from three independent experimental trials.

Implement details

Our proposed method and experiments are conducted on an RTX 3090 GPU using the PyTorch framework. In the experiments, the weight parameters of the ResNet-50 network pre-trained on ImageNet64 are used to initialize the backbone of MCF-Net and the res_conv_4 to res_conv_5 layers on each branch. The size of all vehicle images was set to 256 \(\times\) 256 and randomly flipped horizontally for data enhancement before being input into MCF-Net. We set the batch size to 64 (\(P = 16\), \(K = 4\)), where P represents the number of randomly selected vehicles from the training set and K denotes the number of instances selected for each vehicle for training. The training process lasted 450 epochs, and we chose Adam65 as the optimizer. The learning rate is initially set to \({2\times 10}^{-4}\) and is reduced by a factor of 10 at the 150th, 250th and 300th epochs.

Comparison with state-of-the-art methods

MCF-Net is evaluated alongside other state-of-the-art methods for comparison. The PVEN24 utilizes a parsing network to achieve precise segmentation of vehicle parts, and then employs view-aware feature alignment and a universal visible feature enhancement mechanism to address the issue of viewpoint variations in vehicle Re-ID tasks. The DSN26 learns important detail information by localizing regions such as windshields and headlights. AAVER29 adaptively selects the most discriminative keypoints based on the vehicle’s orientation information and learns discriminative features from them. VehicleNet21 introduces a large-scale dataset to address data limitations and uses data from other datasets to train the model. RAM66 divides the feature map into multiple overlapping regions along the horizontal direction to learn robust localized features. The PRN43 detects vehicle windows, headlights, and brands to capture differences between vehicle instances. TransReID67 establishes a strong transformer-based baseline and introduces the jigsaw patch module and side information embedding to enhance the robustness and discriminability of features. CFSA68 breaks down the self-attention process into a coarse-grained stage and a fine-grained stage to capture the dependencies between similar vehicle components and the detailed information of the vehicle parts, respectively. MUSP69 introduces multiple spatial attention and channel attention mechanisms to learn important discriminative regions. The MVAN70 distributes each branch to learn viewpoint-specific features for front, rear and side views and introduces a spatial attention module in each branch to learn local cues. PSA71 proposes a two-branch network that leverages a pyramid structure and a spatial attention module to learn local and global features respectively. VANet72 learns to explicitly model viewpoint differences through viewpoint classification loss and viewpoint-aware metrics so that features from different viewpoints of the same vehicle are aligned in the metric space. LAPNet73 reinforces key local features through a local perceptual attention mechanism, and facilitates information exchange and fusion between different local features through a local alignment module. Tables 1 and 2 present the experimental outcomes for the VeRi-776 and VehicleID datasets, respectively.

Comparison on the VeRi-776 dataset

In Table 1, we evaluate MCF-Net versus other state-of-the-art vehicle Re-ID models on VeRi-776, focusing on metrics such as mAP, Rank-1 and Rank-5 accuracy. MCF-Net significantly surpasses network architectures that use auxiliary models (PVEN24, DSN26, AAVER29 and VehicleNet21). Its uniqueness lies in the fact that it dispenses with the need for external models or additional annotated data, achieving performance improvement with only the attention mechanism used. Compared with rigid partitioning-based approaches (RAM66 and PRN43), MCF-Net can efficiently assess feature significance and localize key cues while possessing significant performance advantages. Compared to VANet72, a viewpoint tagging-based approach, MCF-Net accurately captures both comprehensive and subtle features of an image, while enhancing the representation of key features through an attention mechanism. The performance of MCF-Net also demonstrates significant advantages over typical attention mechanism-based approaches (TransReID67, CFSA68, MUSP69, MVAN70, PSA71 and LAPNet73). In addition, we have analyzed the proposed method in comparison with existing methods in terms of computational cost. The experimental results show that our method requires only 23.02 GFLOPs and 83.41M parameters, which is a significant advantage in terms of computational efficiency. For example, compared to DSN, our method reduces the number of parameters by 8.39M while maintaining the performance. Although CFSA has fewer parameters (34.53M) than our method, its computational cost is 470 GFLOPs, which is much higher than our computational cost. These results demonstrate that our method achieves higher computational efficiency with a better performance parameter trade-off, further highlighting the superiority of our approach in balancing model complexity with computational overhead.

Comparison on the VehicleID dataset

To validate the efficacy of MCF-Net, we conducted experiments on the VehicleID dataset, showcasing its performance via Rank-1 and Rank-5 accuracy scores across the small, medium and large test subsets. The experimental results are presented in Table 2.

Ablation experiments

To evaluate the impact of each component of MCF-Net on the overall model performance, we conducted component ablation studies on VeRi-776, and optimized the network architecture accordingly for enhanced model efficacy.

Influence of the MCF attention modules

The MCF attention mechanism introduced in this paper retains the feature information in different axes through horizontal and vertical compression operations so that the network can focus on the important information in different directions while improving the computational efficiency and uses the relevant information in the image more comprehensively by fusing the attention maps of multiple axes to strengthen the region of common concern in multiple axes. On the basis of this attention mechanism, we design attention modules from different dimensions. To analyze the impact of the S-MCF and C-MCF modules on model performance, we first design a baseline, which consists of a ResNet-50 backbone and a global branch, and then add the S-MCF and C-MCF modules after the res_conv5 layer of the baseline to obtain “Baseline+S-MCF” and “Baseline+C-MCF”. “Baseline+S-MCF+C-MCF” represents the addition of S-MCF and C-MCF modules to the spatial branch and channel branch respectively.

Table 3 shows that “Baseline+S-MCF” achieves 2%, 0.9% and 0.4% higher mAP, Rank-1 accuracy and Rank-5 accuracy, respectively, than “Baseline”. “Baseline+C-MCF” achieves 2.3%, 1.4% and 0.5% higher mAP, Rank-1 accuracy and Rank-5 accuracy, respectively, than “Baseline”. This indicates that the proposed modules based on the MCF attention mechanism with two different dimensions are effective. When both S-MCF and C-MCF modules are incorporated, the performance of “Baseline+S-MCF+C-MCF” is significantly improved. Specifically, compared to “Baseline+S-MCF”, it achieves improvements of 3.9%, 1.8%, and 0.5% in mAP, Rank-1, and Rank-5 accuracy, respectively. When compared with “Baseline+C-MCF”, it increases by 3.6%, 1.3%, and 0.4% respectively. These results indicate significant complementarity between the S-MCF and C-MCF modules. When combined, the model can optimize both spatial and channel dimensions simultaneously, thus modeling features more comprehensively. In addition to comparing the performance with that of Baseline to validate the efficacy of our two attention modules, we further conduct ablation studies on MCF-Net. “MCF-Net (w/o S-MCF)” and “MCF-Net (w/o C-MCF)” denote the networks that remove the S-MCF module and the C-MCF module from the three-branch MCF-Net, respectively. “MCF-Net (w/o S-MCF+C-MCF)” denotes the simultaneous removal of both modules from the three-branch architecture of MCF-Net. As shown in Table 3, the mAP, Rank-1 accuracy and Rank-5 accuracy of “MCF-Net (our method)” are 83.9%, 96.9% and 99.0%, respectively. The mAP, Rank-1 accuracy and Rank-5 accuracy of “MCF-Net (w/o S-MCF)” decreased by 1.4%, 1.7% and 0.3%, respectively. The three evaluation metrics of “MCF-Net (w/o C-MCF)” are lower by 1.7%, 1.6% and 0.3%, respectively, compared to those of “MCF-Net (our method)”. The “MCF-Net (w/o S-MCF+C-MCF)” with both modules removed simultaneously had the lowest performance, achieving only 81.3%, 95.2%, and 98.5% on mAP, Rank-1, and Rank-5 accuracy. The above experimental results further demonstrate that S-MCF and C-MCF have strong complementarity and can significantly improve the overall network performance.

Importance of the MCF operation

In the S-MCF and C-MCF modules, the weights are learned from the fusion of the vertical and horizontal vertical axis attention maps. The compression operation along different axes directions makes the network focus on feature information from different directions of the feature map, whereas the fusion operation compensates for the limitations of single-direction attention and also strengthens the region of common attention on multiple axes. Moreover, the use of feature information in different directions can promote attention learning. To verify the role of the MCF operation in facilitating attention learning, we constructed four different networks, namely, “Baseline+S-MCF (VC)”, “Baseline+S-MCF (HC)”, “Baseline+C-MCF (VC)”, and “Baseline+C-MCF (HC)”. Here, “VC” and “HC” represent vertical compression and horizontal compression operations, respectively. “Baseline+S-MCF (VC)” and “Baseline+C-MCF (VC)” are networks that remove the horizontal compression operation and utilize only the information in the direction of the compressed vertical axis for attention learning. In contrast, “Baseline+S-MCF (HC)” and “Baseline+C-MCF (HC)”, which utilize information only in the direction of the compressed horizontal axis for attention learning, were developed by Baseline and the S-MCF and C-MCF modules, which remove the vertical compression operation.

As shown in Table 4, the mAP, Rank-1 accuracy and Rank-5 accuracy of “Baseline+S-MCF (VC)” decrease by 0.6%, 0.8% and 0.2%, respectively, compared with those of “Baseline+S-MCF”. The three evaluation metrics of “Baseline+C-MCF (VC)” are 1.0%, 0.6% and 0.2% lower than those of “Baseline+C-MCF”. When only the information in the horizontal axis direction is utilized, the mAP, Rank-1 accuracy and Rank-5 accuracy of “Baseline+S-MCF (HC)” and “Baseline+C-MCF (HC)” are also reduced to a certain extent compared with those of “Baseline+S-MCF” and “Baseline+C-MCF”. This illustrates the importance of utilizing multi-axis information simultaneously to facilitate attention learning.

Optimized network structure

The MCF-Net proposed in this paper is a three-branch network, which consists of a global branch (Bg), spatial branch (Bs), and channel branch (Bc), and we demonstrate the importance of each of its branches and the rigid partitioning (RD) operation through ablation experiments. As shown in Table 5, “Bg+Bs (w/o RD)” is a two-branch network consisting of a backbone, a global branch, and a spatial branch that removes rigid partitioning. Compared with the “Baseline” model incorporating the ResNet-50 backbone and global branch, the mAP, Rank-1 accuracy and Rank-5 accuracy of the “Bg+Bs (w/o RD)” model are improved by 4.4%, 1.9% and 0.7%, respectively. “Bg+Bc (w/o RD)” consists of a backbone network, a global branch, and a channel branch with rigid partitioning removed, and compared with “Baseline”, “Bg+Bc (w/o RD)” achieves the same improvement in the three evaluation metrics. These two sets of experimental results highlight the importance of spatial branch and channel branch in improving network performance. Moreover, compared with those of “Baseline+S-MCF” and “Baseline+C-MCF” without the global branch, the mAP, Rank-1 accuracy and Rank-5 accuracy of “Bg+Bs (w/o RD)” and “Bg+Bc (w/o RD)” with the global branch are improved, which demonstrates the necessity of the global branch for improving network performance by capturing the global information of vehicle images.

Compared with “Baseline+S-MCF” and “Baseline+C-MCF”, the dual-branch network consisting of spatial branch and channel branch achieves improvements in mAP, Rank-1 accuracy and Rank-5 accuracy, which indicates that the modular combination strategy can effectively extract and integrate diverse and distinctive information across various dimensions. The incorporation of a global branch into “Bs+Bc (w/o RD)” to create “MCF-Net (w/o RD)” surpasses the two-branch network, which indicates that the combination of three branches can capture the global image context while learning the discriminative information.

To further validate the effectiveness of rigid partitioning, we constructed ablation experiments by dividing the feature maps generated by the S-MCF and C-MCF modules into varying numbers of horizontal blocks, as shown in Table 6. “RD (block-2) (our method)” achieves mAP, Rank-1 accuracy, and Rank-5 accuracy values of 83.9%, 96.9%, and 99.0%, which demonstrates an increase in performance of 0.8%, 1.4%, and 0.2%, respectively, compared to the network that does not implement a rigid partitioning strategy. However, the performance degrades progressively as the number of blocks increases. For instance, with 3 blocks, the mAP, Rank-1 and Rank-5 accuracy decrease by 0.5%, 0.2% and 0.2%, respectively. This suggests that moderate rigid divisions (\(\text {block}=2\)) facilitates the attention module’s ability to capture both prominent and nuanced discriminative features, whereas excessive division (\(\text {block}\ge 3\)) disrupts long-range dependencies among features, leading to weaker integration of global information.

Balance parameters

Following the parameter settings from literature24,74 for cross-entropy loss and triplet loss, we experimentally evaluated the impact of the balance parameters \(\eta\) and \(\omega\). As shown in Figure 4, the model achieves optimal performance when \(\eta = \omega = 1\), reaching 83.9% mAP and 96.9% Rank-1 accuracy. The experimental results demonstrate that cross-entropy loss can effectively improve the vehicle identity recognition ability, while triplet loss enhances the model’s ability to distinguish differences between vehicles. The joint optimization of these two loss functions enables the model to more accurately identify the target image.

Comparison of computational complexity

Given an input feature of size \(H\times W\times C\), the computational complexities of the S-SA, C-SA, S-MCF, and C-MCF modules are respectively:

where G represents the number of groups in grouped convolution. The complexity of the S-SA module is directly proportional to the square of the total number of positions (HW) in the image, whereas the complexities of the C-SA, S-MCF, and C-MCF modules all exhibit a linear relationship with the total number of positions (HW) in the image. Nonetheless, compared to the C-SA module, regardless of the value of G, the computational complexity of the S-MCF and C-MCF modules is significantly lower. Furthermore, we present their respective computational costs in Table 7. The results showed that S-MCF reduced the computational cost by 1.07 GFLOPs compared to S-SA, and C-MCF reduced the computational cost by 1.07 GFLOPs compared to C-SA. This demonstrates that our proposed S-MCF and C-MCF modules effectively reduce the computational complexity of the model.

Visualization analysis

Visualization of feature distribution

To further illustrate the effectiveness of our method, we employ t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) feature map visualization. The t-SNE algorithm reduces high-dimensional data to a two- or three-dimensional space while preserving the local structural information of the original data, facilitating visual analysis. To visually demonstrate the feature distributions of ResNet-50, Baseline, and MCF-Net, we randomly extracted 1198 samples from 20 classes within the VeRi-776 dataset for visualization. The visualization results are presented in Figure 5. Figure 5(a) shows the distribution of features extracted by ResNet-50, where the features of various samples exhibit an overlapping distribution, making it difficult to distinguish the boundaries between classes. Figure 5(b) and (c) respectively display the distributions of features extracted by Baseline and MCF-Net. A notable aggregation of sample features within each class can be observed, with clearer boundaries between classes. Moreover, compared to Figure 5(b), the features of the same class extracted by MCF-Net are more tightly clustered, while the features of distinct classes are further separated or distanced from each other. This demonstrates that MCF-Net proficiently addresses the issues with high inter-class similarity and low intra-class similarity. Each subplot in Figure 6 showcases one image selected from each class, where it is noticeable that some vehicles exhibit high similarities in appearance and color, further highlighting the feature extraction and discrimination capabilities of our proposed method, MCF-Net, in complex scenarios.

Heatmap visualization

In this section, we utilize Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) to generate attention heatmaps for vehicle images. The attention heatmap comparison experiment can be utilized to evaluate the performance of different models. As an intuitive visualization tool showcasing the regions of interest for models, it presents the attention distribution across different input parts in a visual manner. By contrasting the color intensity or brightness variations in attention heatmaps generated by different models, we can gain insights into the model’s effectiveness in capturing key regions and further assess its performance in vehicle Re-ID tasks.

Figure 7 displays the final visual heatmaps for vehicle images processed by “Baseline”, “Baseline+S-MCF”, and “Baseline+C-MCF” under varying perspectives, illumination environments and occlusion scenarios. Through comparative observation, it becomes evident that both “Baseline+S-MCF” and “Baseline+C-MCF” demonstrate superior abilities compared to the “Baseline” model in focusing on crucial vehicle components. They are not only capable of capturing the basic contours and primary features of vehicles but also pay closer attention to details such as the windshield, roof, and interior decorations. This detailed focus on vehicle components enables the models to acquire richer and more comprehensive discriminative information when identifying vehicles. Furthermore, the image features learned by the S-MCF and C-MCF modules synergize, significantly enhancing the recognition capabilities of the models.

Sorting visualization analysis

In this section, to further demonstrate the effectiveness of MCF-Net, we conducted a visual comparison with the Baseline on the VehicleID dataset. We selected 3 vehicle query images and displayed the top-10 retrieval results for each. The results in Figure 8 showcase that MCF-Net can leverage both global and fine-grained features from vehicle images to accurately identify the target image in complex environments.

Conclusion

In this study, we propose a multi-axis compression fusion network (MCF-Net) for vehicle Re-ID that can learn global and fine-grained discriminative features of vehicle images without relying on an auxiliary model by means of attention modules and the rigid partitioning strategy. The core idea of the S-MCF and C-MCF modules is the multi-axis compressed attention mechanism, which updates the weights through compression operations in the vertical and horizontal directions and through parallel self-attention computations in individual axis directions, modeling the global context while also mining the refined features in different directions. By fusing the attention of multiple axes to aggregate feature information and strengthen the features that are commonly focused on multiple axes, the effect of attention learning can be enhanced. Finally, many experiments conducted on the VeRi-776 and VehicleID datasets affirm the efficacy of our proposed method.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Shen, F. et al. GIT: Graph interactive transformer for vehicle re-identification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 32, 1039–1051. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2023.3238642 (2023).

Qian, W., Luo, H., Peng, S. et al. Unstructured feature decoupling for vehicle re-identification. In Avidan, S., Brostow, G., Ciss , M., Farinella, G. & Hassner, T. (eds.) European Conference on Computer Vision, vol. 13674, 336–353, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-19781-9_20 (Springer, Cham, 2022).

Yu, Z. et al. Multi-attribute adaptive aggregation transformer for vehicle re-identification. Inf. Process. Manag. 59, 102868 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Attribute and state guided structural embedding network for vehicle re-identification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 31, 5949–5962. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2022.3202370 (2022).

Khorramshahi, P., Shenoy, V. & Chellappa, R. Robust and scalable vehicle re-identification via self-supervision. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, 5295–5304 (2023).

Gulzar, Y. Fruit image classification model based on mobilenetv2 with deep transfer learning technique. Sustainability 15, 1906. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031906 (2023).

Narayan, V., Mall, P. K., Awasthi, S. et al. Fuzzynet: Medical image classification based on glcm texture feature. In 2023 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Smart Communication (AISC), 769–773, https://doi.org/10.1109/AISC56616.2023.10085348 (IEEE, Greater Noida, India, 2023).

Arco, J. E. et al. Uncertainty-driven ensembles of multi-scale deep architectures for image classification. Inf. Fusion. 89, 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2022.08.010 (2023).

Roy, S. K. et al. Multimodal fusion transformer for remote sensing image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 61, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2023.3286826 (2023).

Ding, Y. et al. Multi-scale receptive fields: Graph attention neural network for hyperspectral image classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 223, 119858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.119858 (2023).

Mo, Y. et al. Review the state-of-the-art technologies of semantic segmentation based on deep learning. Neurocomputing 493, 626–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2022.01.005 (2022).

Yuan, Y. et al. OCNET: Object context for semantic segmentation. Int. J. Comput. Vision 129, 2375–2398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-021-01465-9 (2021).

Yuan, X., Shi, J. & Gu, L. A review of deep learning methods for semantic segmentation of remote sensing imagery. Expert Syst. Appl. 169, 114417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2020.114417 (2021).

Guo, M.-H. et al. Segnext: Rethinking convolutional attention design for semantic segmentation. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 1140–1156 (2022).

Ye, M. et al. Deep learning for person re-identification: A survey and outlook. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 44, 2872–2893. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2021.3054775 (2021).

Bai, X. et al. Deep-person: Learning discriminative deep features for person re-identification. Pattern Recogn. 98, 107036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2019.107036 (2020).

Huang, N. et al. Deep learning for visible-infrared cross-modality person re-identification: A comprehensive review. Information Fusion. 91, 396–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2022.10.024 (2023).

Liu, F., Kim, M., Gu, Z. et al. Learning clothing and pose invariant 3d shape representation for long-term person re-identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 19617–19626 (2023).

Yao, Y. et al. A sparse graph wavelet convolution neural network for video-based person re-identification. Pattern Recogn. 129, 108708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2022.108708 (2022).

Soni, K. et al. Person re-identification in indoor videos by information fusion using graph convolutional networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 210, 118363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118363 (2022).

Zheng, Z. et al. Vehiclenet: Learning robust visual representation for vehicle re-identification. IEEE Trans. Multimedia 23, 2683–2693. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2020.3014488 (2020).

Dilshad, N. & Song, J. Dual-stream siamese network for vehicle re-identification via dilated convolutional layers. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Smart Internet of Things (SmartIoT), 350–352, https://doi.org/10.1109/SmartIoT52359.2021.00065 (Jeju, Korea, Republic of, 2021).

Zhu, X., Luo, Z., Fu, P. et al. Voc-reid: Vehicle re-identification based on vehicle-orientation-camera. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, 602–603 (2020).

Meng, D., Li, L., Liu, X. et al. Parsing-based view-aware embedding network for vehicle re-identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 7103–7112 (2020).

Wang, Z., Tang, L., Liu, X. et al. Orientation invariant feature embedding and spatial temporal regularization for vehicle re-identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 379–387 (2017).

Zhu, W. et al. A dual self-attention mechanism for vehicle re-identification. Pattern Recogn. 137, 109258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2022.109258 (2023).

Hu, Z. et al. Vehicle re-identification based on keypoint segmentation of original image. Appl. Intell. 53, 2576–2592. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10489-022-03192-1 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Global-local discriminative representation learning network for viewpoint-aware vehicle re-identification in intelligent transportation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 72, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2023.3295011 (2023).

Khorramshahi, P., Kumar, A., Peri, N. et al. A dual-path model with adaptive attention for vehicle re-identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 6132–6141 (2019).

Wang, Q., Wu, B., Zhu, P. et al. Eca-net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 11534–11542 (2020).

Guo, M.-H. et al. Beyond self-attention: External attention using two linear layers for visual tasks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 45, 5436–5447. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2022.3211006 (2022).

Hu, J., Shen, L. & Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 7132–7141 (2018).

Zhao, H., Jia, J. & Koltun, V. Exploring self-attention for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 10076–10085 (2020).

Wang, X., Girshick, R. & Gupta, A. Non-local neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 7794–7803 (2018).

Cao, Y., Xu, J., Lin, S. et al. Gcnet: Non-local networks meet squeeze-excitation networks and beyond. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) workshops, 0–0 (2019).

Yin, M., Yao, Z., Cao, Y. et al. Disentangled non-local neural networks. In Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T. & Frahm, J. (eds.) European Conference on Computer Vision, vol. 12360, 191–207, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58555-6_12 (Springer, Cham, 2020).

Maaz, M., Shaker, A., Cholakkal, H. et al. Edgenext: efficiently amalgamated cnn-transformer architecture for mobile vision applications. In Karlinsky, L., Michaeli, T. & Nishino, K. (eds.) European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), vol. 13807, 3–20, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25082-8_1 (Springer, Cham, 2022).

Dosovitskiy, A., Beyer, L., Kolesnikov, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (2021).

Li, G. et al. Recaptured screen image identification based on vision transformer. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 90, 103692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvcir.2022.103692 (2023).

Wang, W., Xie, E., Li, X. et al. Pyramid vision transformer: A versatile backbone for dense prediction without convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 568–578 (2021).

Zhou, Y. & Shao, L. Aware attentive multi-view inference for vehicle re-identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 6489–6498 (2018).

Tang, Z., Naphade, M., Birchfield, S. et al. Pamtri: Pose-aware multi-task learning for vehicle re-identification using highly randomized synthetic data. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 211–220 (2019).

He, B., Li, J., Zhao, Y. et al. Part-regularized near-duplicate vehicle re-identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 3997–4005 (2019).

Khorramshahi, P., Peri, N., Chen, J.-c. et al. The devil is in the details: Self-supervised attention for vehicle re-identification. In Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T. & Frahm, J. (eds.) European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), vol. 12359, 369–386, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58568-6_22 (Springer, Cham, 2020).

Li, Y. Shark fine-grained image classification based on feature fusion and attention mechanism. In 2024 2nd International Conference on Algorithm, Image Processing and Machine Vision (AIPMV), 171–175, https://doi.org/10.1109/AIPMV62663.2024.10692236 (IEEE, China, 2024).

Imani, M. Attention based multi-level and multi-scale convolutional network for polsar image classification. Adv. Space Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2025.03.051 (2025).

Wang, L. et al. SAT-GCN: Self-attention graph convolutional network-based 3d object detection for autonomous driving. Knowl.-Based Syst. 259, 110080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2022.110080 (2023).

Hu, H., Gu, J., Zhang, Z. et al. Relation networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 3588–3597 (2018).

Qiu, Y. et al. SATS: Self-attention transfer for continual semantic segmentation. Pattern Recogn. 138, 109383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2023.109383 (2023).

Xiang, X., Ma, Z., Zhang, L. et al. Lka-reid: Vehicle re-identification with large kernel attention. In ICASSP 2025-2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP49660.2025.10889524 (IEEE, Hyderabad, India, 2025).

Jiao, Y., Qiu, S., Sun, L. et al. Dsa-scgc: A dual self-attention mechanism based on space-channel grouped compression for vehicle re-identification. In 2024 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1109/IJCNN60899.2024.10650480 (IEEE, Yokohama, Japan, 2024).

Li, Z. et al. Adjacent-atrous mechanism for expanding global receptive fields: An end-to-end network for multi-attribute scene analysis in remote sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2024.3422007 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Local feature acquisition and global context understanding network for very high-resolution land cover classification. Sci. Rep. 14, 12597. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63363-7 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Comprehensive attribute difference attention network for remote sensing image semantic understanding. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Rem. Sens. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2024.3516501 (2024).

Woo, S., Park, J., Lee, J.-Y. et al. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 3–19 (2018).

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N. et al. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. arXiv:1706.03762 (2017).

Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K. et al. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding, arXiv:1810.04805 (2018).

Wu, F., Fan, A., Baevski, A. et al. Pay less attention with lightweight and dynamic convolutions, arXiv:1901.10430 (2019).

Touvron, H., Cord, M., Douze, M. et al. Training data-efficient image transformers & distillation through attention. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 10347–10357, arXiv:2012.12877 (2021).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. et al. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 770–778 (2016).

Hermans, A., Beyer, L. & Leibe, B. In defense of the triplet loss for person re-identification, arXiv:1703.07737 (2017).

Liu, X., Liu, W., Ma, H. et al. Large-scale vehicle re-identification in urban surveillance videos. In 2016 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICME.2016.7553002 (IEEE, Seattle, WA, USA, 2016).

Liu, H., Tian, Y., Yang, Y. et al. Deep relative distance learning: Tell the difference between similar vehicles. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2167–2175 (2016).

Deng, J., Dong, W., Socher, R. et al. Large-scale vehicle re-identification in urban surveillance videos. In 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 248–255, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2009.5206848 (IEEE, Miami, FL, USA, 2009).

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization, arXiv:1711.05101 (2017).

Liu, X., Zhang, S., Huang, Q. et al. Ram: a region-aware deep model for vehicle re-identification. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICME.2018.8486589 (IEEE, San Diego, CA, USA, 2018).

He, S., Luo, H., Wang, P. et al. Transreid: Transformer-based object re-identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 15013–15022 (2021).

Huang, F., Lv, X. & Zhang, L. Coarse-to-fine sparse self-attention for vehicle re-identification. Knowl.-Based Syst. 270, 110526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2023.110526 (2023).

Lee, S., Woo, T. & Lee, S. H. Multi-attention-based soft partition network for vehicle re-identification. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 10, 488–502. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcde/qwad014 (2023).

Teng, S. et al. Multi-view spatial attention embedding for vehicle re-identification. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 31, 816–827. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSVT.2020.2980283 (2020).

Yang, J. et al. A two-branch network with pyramid-based local and spatial attention global feature learning for vehicle re-identification. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 6, 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1049/cit2.12001 (2021).

Chu, R., Sun, Y., Li, Y. et al. Vehicle re-identification with viewpoint-aware metric learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 8282–8291 (2019).

Qin, L. & Cui, P. Lapnet: Local aware permutation network for vehicle re-identification. In 2024 IEEE 4th International Conference on Electronic Technology, Communication and Information (ICETCI), 581–586 (IEEE, 2024).

Zhuge, C., Peng, Y. & Li, Y. Attribute-guided feature extraction and augmentation robust learning for vehicle re-identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, 618–619 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Focus on Research and Development Plan in Shandong Province, China NO. 2019GGX101055.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, X.P.; Methodology, T.M. and K.S.; Design of experiments and interpretation of results, T.M. and K.S.; Validation, W.S.; Data recording and analysis, T.L.; Writing-original draft preparation, T.M.; Writing-review and editing, X.P. and C.W. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, T., Sun, K., Pang, X. et al. Multi-axis compression fusion network for vehicle re-identification. Sci Rep 15, 30541 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15854-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15854-4