Abstract

Ammonia (NH3) is a key precursor of secondary inorganic aerosols. During precipitation, NH3 in the atmosphere can be captured by rain and converted to NH4+, whereas during evaporation, NH4+ can become NH3 and be released again. The northeastern region of China experiences diverse precipitation types, making the study of the NH3 release flux and its influencing factors during evaporation highly significant. In this study, precipitation samples of haze (HZ), dust (DS), convective (CC), and monsoon (MN) events were collected three times in Changchun from March to September 2024 (a total of twelve rain events), and indoor simulation evaporation experiments were conducted. The results revealed significant differences in the NH4+ conversion rate (R), NH3 release flux (F) and release rate (V) across the precipitation types (P < 0.05). The NH3 flux released from precipitation evaporation was 20.33 µg/m2 in spring and 64.53 µg/m2 in summer, accounting for approximately 4.14% and 7.70%, respectively, of the corresponding atmospheric NH3 concentrations. Meteorological factors influenced NH3 release similarly across precipitation types. R peaked and then decreased with increasing temperature and was significantly negatively correlated with wind speed and precipitation amount (P < 0.05). In addition, this study calculates the temperature coefficient (K1), wind speed coefficient (K2), and precipitation amount coefficient (K3) by considering these factors. These findings provide valuable insights for estimating NH3 release fluxes from precipitation evaporation in different regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

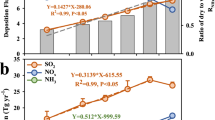

Ammonia (NH3), the most abundant alkaline gas in the atmosphere1 readily neutralizes acidic gases in the air, forming secondary inorganic aerosols such as ammonium sulfate, ammonium bisulfate, ammonium nitrate, and ammonium chloride2,3. Ammonium (NH4+) accounts for up to 57% of fine particulate matter (PM2.5)4,5,6 significantly affecting human health7 climate models8 nutrient cycling9 the atmospheric radiation balance and air quality10. Recent satellite monitoring has indicated a rise in global atmospheric NH3 concentrations, driven by factors such as decreased emissions of acidic gases (e.g., SO2 and NO2), rising temperatures, and increased fertilizer use11. This trend has transformed urban atmospheres into NH3-rich environments, raising widespread concern regarding NH3 sources and concentrations.

Previous studies have identified agricultural activities, such as fertilization and livestock farming, as the primary sources of atmospheric NH3>12,13. Other significant contributors include vehicle emissions14 coal and biomass combustion15 industrial and power plant NH3 emissions16 and dew volatilization17. NH3 released from these sources enters the atmosphere, and owing to its water-soluble properties, it can be absorbed during precipitation formation and settle to the surface with rainfall18,19 leading to high concentrations of NH4+ in atmospheric precipitation. For example, NH4+ was the most abundant ion in precipitation from Ya’an15 and Dalian, China20 with concentrations of 169.6 µEq/L and 107.76 µEq/L, respectively, accounting for 36% and 19.75% of the total ion concentration. High concentrations of NH4+ are likely to be re-emitted as NH3 during the evaporation of precipitation. Previous studies reported a rapid increase in near-surface NH3 concentrations 1–2 h after specific rainfall events in northern Colorado, USA17 as well as in Beijing1 and Nanchang, China21.

Precipitation serves as an indirect indicator of local air pollution levels, with its chemical composition and amount varying significantly on the basis of meteorological conditions, air mass trajectories, and pollution sources. For example, precipitation in Guiyang is influenced primarily by atmospheric circulation and terrain, with the majority occurring in summer as convective rain. In contrast, spring is dominated by persistent precipitation caused by stratiform clouds. The major ions in precipitation are SO42− and Ca2+, with NH4+ concentrations of approximately 50 µEq/L22. In comparison, Beijing experiences frequent dust storms in spring, and precipitation is mostly of the dust type23. The main ions in precipitation are SO42− and NH4+, with the NH4+ concentration reaching as high as 346 µEq/L24 approximately seven times higher than those observed in Guiyang. Unlike Guiyang and Beijing, precipitation in Changchun is mainly haze-type and dust-type during spring, whereas convective and monsoonal rainfall prevails in summer. Precipitation in Changchun contains high concentrations of SO42− and Mg2+, with an average NH4+ concentration of 104.54 ± 35.97 µEq/L25.

Although NH4+ concentrations in rain are relatively high in many regions15,20 systematic studies on the emission flux of NH3 during the evaporation process remain limited. Most existing research has focused on specific geographic areas22 with insufficient consideration of the combined effects of precipitation chemistry, precipitation amount, and key meteorological factors such as temperature and wind speed. In addition, some methods used to estimate NH3 fluxes lack validation under real environmental conditions, resulting in uncertainties. Therefore, a more comprehensive investigation is needed to characterize the emission patterns and driving mechanisms of NH3 under diverse precipitation types and meteorological conditions. The objectives of this study are as follows:

-

1.

To analyze the chemical composition of different types of precipitation in Changchun.

-

2.

To quantify the conversion rate (R), release flux (F), and release rate (V) of NH4+ to NH3 during evaporation.

-

3.

To assess the influence of key meteorological (temperature, wind speed, and precipitation amount) and chemical (ionic composition and pH) factors and to propose corresponding correction factors.

Materials and methods

Experimental site and sample collection

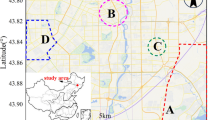

The experimental study was conducted in Changchun City, Jilin Province (Fig. 1(a)). Changchun, located in northeastern China (43.88°N, 125.35°E), is a central city in the Northeast Asia economic zone and is a former industrial hub. The city covers a total area of 24,744.6 km2 and has a population exceeding 9.1 million.

On the basis of air quality monitoring data collected during the 24 h preceding precipitation events (PM2.5 and PM10), backward air mass trajectories, and precipitation characteristics, the precipitation events in Changchun were classified into four types: haze type (HZ), dust type (DS), monsoon type (MN), and convective type (CC).

-

HZ: PM2.5 > 50 µg/m3 and PM2.5/PM10 > 0.7;

-

DS: PM10 > 100 µg/m3 and PM2.5/PM10 < 0.4;

-

MN: precipitation duration > 5 h, total rainfall > 10 mm, with moisture trajectories originating from oceanic sources;

-

CC: precipitation duration < 1 h, accompanied by strong convection or thunderstorm activity.

Changchun is located in the high-latitude northern temperate zone and experiences a typical continental monsoon climate. Both precipitation types and meteorological conditions exhibit pronounced seasonal variations. In spring, inland airflow from the Eurasian continent dominated, leading to a higher frequency of DS and HZ events. In contrast, summer precipitation is influenced primarily by Pacific-sourced moisture transport and thermally induced surface convection, resulting in more frequent MN and CC events.

Precipitation samples were collected from March 15, 2024, to September 15, 2024, with three sampling events for each precipitation type. Although the number of events was limited, the sampling strategy was designed to reflect the dominant precipitation types and seasonal variation in Changchun during this period. This approach enabled a controlled comparative analysis under a consistent classification scheme and standardized indoor simulation conditions. For each precipitation type, the average outdoor temperature and wind speed during the evaporation period, as well as the total precipitation amount were recorded (Table 1). Specifically, the post-rainfall evaporation period was set to 5 h for DS and HZ events and 3 h for CC and MN events.

Precipitation samples were collected from a lawn located approximately 50 m from the main road on the campus of Jilin Jianzhu University. No industrial pollution sources or buildings exceeding 30 m in height were located in the vicinity, and the surrounding area lacked dense vegetation canopies or open water bodies, making this location representative of typical urban precipitation conditions. Importantly, the samples were collected directly during rainfall events using pre-cleaned glass beakers, without any contact with terrestrial or aquatic surfaces (e.g., forest litter, rivers, soil). This approach ensured that the chemical composition of the samples solely reflected atmospheric wet deposition, without influence from post-depositional surface interactions. Prior to use, the beakers were thoroughly rinsed with deionized water (18.25 MΩ cm) and dried in an oven to minimize dilution effects from residual water. The beakers were placed within 30 min before the onset of each precipitation event, and samples were collected within 30 min after the event ended. Under these conditions, the influence of dry deposition on the samples can be considered negligible. In addition, to meet the analytical requirements, the collected volume of each sample exceeded 20 mL.

Sample analysis and laboratory simulations

The samples were filtered within 30 min of collection via a 0.45 μm microporous membrane filter. The pH and electrical conductivity (EC) were measured using a Leici DZS-706-A multiparameter analyzer immediately after filtration to prevent alterations caused by contamination or storage (Fig. 1(b)). The concentrations of four anions (Cl−, NO2−, NO3−, and SO42−) and five cations (NH4+, Na+, K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+) in the precipitate were determined via ion chromatography (Thermo Fisher, USA). The anions were separated via an AS-19 column with 20 mM KOH as the eluent. Cations were separated via a CS-15 column with methanesulfonic acid as the isocratic eluent. All the samples were stored in the dark at ~ 4 °C until further analysis.

After analyzing the chemical compositions of the four types of precipitation, we quantified the NH3 release flux and rate through complete evaporation experiments. A single-factor experimental design was employed to examine the factors influencing the NH4+ conversion rate. On the basis of the seasonal characteristics of the precipitation types presented in Table 1, different evaporation conditions were set to compare the effects of temperature and wind speed on the NH4+ conversion rates during precipitation evaporation. The effect of the rainfall amount on NH3 release was assessed by adjusting the sample volume in the glass test tube to simulate different rainfall amounts.

The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 1(c). The samples were placed in a glass test tube, with one end connected to an air compressor pump supplying clean zero air and the other end linked to a URG-2000-30*150-3CSS annular denuder to collect the NH3 released during precipitation evaporation. The denuder was cleaned and coated before use, following a procedure detailed in previous studies25. During evaporation, some NH4+ can volatilize as gaseous NH3 and N2. The released NH3 is captured by the annular denuder, while N2 is released directly into the atmosphere. Moreover, some NH4+ remains as ammonium salts in the glass test tube. Once the solution fully evaporated, 20 mL of deionized water was added to the test tube, and the tube was thoroughly shaken to extract residual components remaining after complete evaporation. Subsequently, 10 mL of deionized water was added to the denuder, which was slowly rotated for ~ 30 s to extract trapped substances. (Fig. 1(d)). Both extracts were analyzed for NH4+ concentration via ion chromatography, and the data were used to calculate the NH4+ release ratio and residual rate during the precipitation evaporation phase.

(a) Sample collection location and method; (b) pretreatment prior to the experiment; (c) laboratory-simulated precipitation evaporation and experimental variable gradients (red bold text indicates the baseline experimental conditions used to investigate the effects of other variables on the NH4+ conversion rate); (1) glass test tube; (2) annular denuder; (d) sample testing.

Data analysis

The ion balance (ΔC) of the samples was determined via the following formula on the basis of the ion concentration (µEq/L) determined via ion chromatography26:

The NH4+ conversion rate (R) during evaporation was determined from the ratio of NH4+absorption by the denuder to the corresponding ion concentration in the precipitation. This conversion rate can be calculated via the following Eq27:

where Cg is the concentration of NH4+ in the denuder (mg/L), Ci is the concentration of NH4+ in the precipitation (mg/L), F is the daily flux of NH3 released during precipitation evaporation (µg/m2), I is the rainfall depth (mm), 1000 is a conversion factor, V is the rate of NH3 release during precipitation evaporation (ng/m2·s), and T is the evaporation duration (s).

The volume-weighted mean (VWM) of the chemical components of precipitation was calculated via the following formula28:

where Pi represents the depth of each rainfall event (mm), Mi represents the concentration of a given chemical element (µEq/L), the pH value or electrical conductivity (EC; µS/cm), and n represents the total number of rainfall events.

The total dissolved solids (TDS) in precipitation can be estimated from EC via the following Eq29:

where TDS is the total dissolved solids (mg/L), EC is the electrical conductivity (µS/cm), and Ke is an empirical correlation factor, which typically ranges from 0.55 to 0.8, with an average value of Ke ≈ 0.7.

A previous study showed that the proportion of NH4+ released as a gas during evaporation depends on the difference in concentration between nonvolatile ions and the concentration of NH4+itself. This value can be calculated via the following Eq17:

where Frac (NH3) is the theoretical fraction of NH4+ that is converted to NH3 during evaporation, [NH4+]i is the initial NH4+ concentration in solution (µEq/L), ∑nonvolatile anions is the sum of the concentrations of nonvolatile anions (e.g., SO42−, Cl−, and NO3−), and ∑nonvolatile cations is the sum of the concentrations of nonvolatile cations (e.g., Ca2+, K+, Mg2+, and Na+).

The coefficients Kn (n = 1,2,3), which represent the influence of various meteorological conditions on NH4+ conversion in precipitation, were calculated on the basis of the R value measured from the indoor simulated evaporation experiment and the theoretical conversion rate (Frac (NH3)) calculated via Eq. (7). The general formula for calculating the meteorological influence coefficient is as follows:

where K1, K2, and K3 denote the temperature coefficient, wind speed coefficient, and precipitation amount coefficient, respectively.

Statistical analysis was conducted via SPSS 25.0. Q‒Q probability plots were used to determine the distributions of cations (Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, K+, and NH4+) and anions (NO2−, Cl−, NO3−, and SO42−). Given the limited sample size for each event type (n = 3), nonparametric statistical methods were applied to assess differences between groups. A significance level of P < 0.05 was adopted for reference.

The 24-hour concentration data of air pollutants, including PM2.5 and PM10, in Changchun are freely available from the China National Environmental Monitoring Center (https://quotsoft.net/air/). Meteorological parameters for the study area, such as the wind speed, temperature, and precipitation, were obtained from the automatic weather station (MK-111-LR) at Jilin Jianzhu University. Airflow characteristics near the study area are analyzed via the hybrid single-particle Lagrangian integrated trajectory (HYSPLIT) model provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) (https://www.ready.noaa.gov/HYSPLIT_traj.php)30,31. This model uses an altitude of 500 m as the boundary layer height to generate 24-hour backward trajectories of air masses. Data on the atmospheric quality and fire hotspot distribution along air mass pathways can be obtained from the Fire Information for Resource Management System (FIRMS) (https://firms.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/).

Results and discussion

Chemical composition of different precipitation types

According to statistics, there were 20 precipitation days in spring in Changchun, with a total rainfall of 15.2 mm. Among them, HZ and DS occurred three times each, generally accompanied by low rainfall amounts. In summer, precipitation was predominantly classified as MN, which was influenced mainly by East Pacific circulation and typhoons. In addition, the concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 in spring were significantly higher than those in summer (P < 0.05). Different meteorological conditions and air quality levels can result in variations in the chemical compositions of different types of precipitation.

pH is a fundamental and widely recognized indicator for assessing precipitation acidity15. Fig 2 demonstrated that the pH values of the four types of rainfall ranged from 5.75 to 7.41, with significant differences (P < 0.05). The VWM pH, determined from rainfall data via Eq. (5), followed the sequence HZ < MN < CC < DS (P < 0.05). All the measured values exceeded the pH of natural precipitation in equilibrium with atmospheric CO2 (pH = 5.6)26. Consequently, the four types of precipitation were considered nonacidic and unlikely to cause acid damage to the environment, which is consistent with the findings of Wu et al.32.

EC is a crucial indicator of atmospheric pollution, with elevated values typically signifying increased pollution levels33. Figure 2 revealed that the EC of various types of precipitation followed the order DS > HZ > MN > CC (P < 0.05), with all values surpassing the average EC of 14.8 µS/cm at Waliguan Mountain, a background site in China34. Comparison analysis revealed notable seasonal differences, with the EC of spring precipitation being significantly greater than that of summer precipitation (P < 0.05). This trend reflects the improved air quality in summer compared with that in spring. On the one hand, the greater amount and frequency of rainfall in summer reduce the amount of suspended particulate pollutants in the atmosphere, resulting in lower EC values. On the other hand, the low temperatures and high atmospheric pressure characteristic of spring frequently create stagnant wind conditions, inhibiting the dispersion of atmospheric particulates and leaving more pollutants suspended in the air35.

According to Fig. 2, the predominant water-soluble ions in HZ, DS, CC, and MN were SO42−, NO3−, Ca2+, and NH4+, accounting for 74%, 75%, 74%, and 67% of the total ion concentrations in these types of precipitation, respectively. Although the major cation and anion components were the same, the ion concentrations in HZ and DS were significantly greater than those in CC and MN (P < 0.05), reflecting marked seasonal variation. This disparity can be attributed to the difference in rainfall amounts between spring and summer, which resulted in varying levels of ion dilution. Additionally, the intensification of anthropogenic activities in spring, such as agricultural practices, urban construction, transportation, and biomass burning (e.g., straw or waste combustion), significantly enhances the emission of sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter, thereby shaping the unique seasonal characteristics of the different precipitation types36. A comparative analysis of precipitation types within the same season indicated that HZ and DS presented similar ion compositions, as did CC and MN. This similarity can be explained by the shared sources of pollutants. Spring haze formation is predominantly affected by meteorological drivers, pollutant sources, and atmospheric circulation patterns rather than by coal burning or heating emissions, distinguishing it from the haze formation mechanisms observed in autumn and winter37,38. As a result, the ionic characteristics of HZ and DS were consistent. The ionic composition of precipitation driven by intense atmospheric convection under the strong influence of summer ocean monsoons is likely governed by marine air masses. Consequently, CC and MN exhibited analogous structural compositions.

The ratio of total anions to total cations (ΔC) is commonly used as an indicator of the relative amounts of major ionic components39. The calculations indicated that the total ion concentration ratio of anions to cations in all the precipitation samples was 0.93 ± 0.07, suggesting a deficiency of anions. This anion deficiency could be attributed to unmonitored inorganic anions (e.g., F−, PO43−) and organic anions (e.g., HCOO−, CH3COO−) present in the precipitation40. Additionally, construction dust from nearby areas and the naturally alkaline properties of northern China’s soil likely contributed to the enrichment of cations such as Ca2+ and Mg2+41,42. Fig 2 demonstrated that the VWM of the total ion concentration in spring precipitation was approximately double that in summer precipitation. This observation was consistent with Rao et al. (2016), who reported that analyte concentrations were higher during dry periods than during wet periods, emphasizing the critical impact of climatic conditions on the composition of precipitation.

To examine the characteristics of airflow movement near the study area and identify the primary sources of ions in different precipitation types, specific dates were chosen to represent HZ, DS, CC, and MN: April 12, March 27, August 20, and July 22, respectively. Starting at an altitude of 500 m—selected to represent regional air mass transport while minimizing the effects of surface-layer turbulence—24-hour backward trajectories were calculated, as illustrated in Fig. 3. The trajectories for different precipitation types showed significant differences and distinct seasonal patterns: in spring, terrestrial input predominated with poorer air quality, whereas summer air masses mainly originated from marine sources. Air masses generally acquire pollutants as they pass through regions with emission sources43. The air masses associated with the HZ (Fig. 3(a)) followed long trajectories from the northeast, passing through areas with poor air quality, resulting in high concentrations of SO42− and NO3−. The air masses for DS (Fig. 3(b)) predominantly originated from eastern Russia, with long-range transport of soil dust resulting in the enrichment of terrestrial components such as Ca2+ and Mg2+44. CC air masses (Fig. 3(c))involve primarily localized transport between northeastern cities, with significant contributions from anthropogenic pollution45. MN air masses (Fig. 3(d)) are influenced by typhoon weather, characterized by long trajectories and fast-moving, clean marine airflow. After passing through regions of poor air quality in the Sea of Japan, these air masses carry some anthropogenic pollutants46.

Backward trajectories of air masses and air quality along their pathways for various types of rainfall events: (a) HZ (4.12); (b) HD (3.27); (c) CC (8.20); (d) MN (7.22).Map data source: Tianditu Map Import service via the original plugin (version 2021b (9.85)) (https://www.originlab.com).

NH4 + conversion rate, release flux and rate of NH3 in different precipitation types

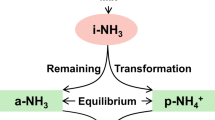

The transformation of NH4+ to NH3 during evaporation is governed primarily by the acid–base equilibrium between NH4+ and NH3 (NH4+ ⇌ NH3 + H+, pKa ≈ 9.25), which is highly sensitive to changes in pH and temperature47,48. Under near-neutral or slightly acidic conditions (pH < 7), inorganic nitrogen predominantly exists as NH4+, making NH3 volatilization thermodynamically unfavorable. However, as evaporation progresses, localized increases in pH may occur due to preferential water loss and ionic concentration effects, slightly shifting the equilibrium toward NH3. This shift can increase the volatilization of NH3. Additionally, the thermal instability and semi volatility of NH4NO3 at temperatures above 25 °C may further contribute to NH3 emissions49. Therefore, the observed unrecovered NH4+ (26.90 ± 13.21%) may have resulted from the combined effects of the NH4+/NH3 acid–base equilibrium and NH4NO3 volatilization under the experimental conditions.

The R values for the different precipitation types, ranked from high to low, were DS > HZ > CC > MN (P < 0.05), with average values of 61.67 ± 9.71%, 61.00 ± 1.73%, 45.67 ± 9.02%, and 38.67 ± 6.35%, respectively (Fig. 4). This indicates that approximately half of the NH4+ in the precipitation in the study area was released back into the boundary layer, facilitating nitrogen deposition. Assuming complete evaporation of all atmospheric precipitation, the NH3 release flux (F) and release rate (V) were calculated via Eqs. (3) and (4), considering the different precipitation amounts and evaporation durations. The results revealed significant differences in both the release flux (F) and release rate (V) among the different precipitation types. In spring, the F values for HZ and DS were 1714.85 ± 1662.88 µg/m2 and 4010.58 ± 2184.05 µg/m2, respectively, with corresponding V values of 93.34 ± 112.32 ng/m2·s and 216.43 ± 132.37 ng/m2·s, respectively. In summer, the F values for CC and MN were 905.39 ± 662.89 µg/m2 and 11192.50 ± 6580.20 µg/m2, respectively, whereas the V values were 52.45 ± 39.03 ng/m2·s and 714.44 ± 408.37 ng/m2·s, respectively. These differences may result from variations in precipitation characteristics and evaporation durations among the different rain types. Notably, within the same precipitation type, large variations in the amount of precipitation among individual events can lead to substantial fluctuations in F values, thereby contributing to the large standard deviations observed.

On the basis of the total precipitation during the study period and an actual evaporation ratio of approximately 6%50, the average NH3 release flux from rainfall evaporation was estimated to be 20.33 µg/m2 in spring and 64.53 µg/m2 in summer. To further assess the potential contribution of this flux to atmospheric NH3 levels, the atmospheric boundary layer was defined as 100 m, which more accurately represents the near-surface environment where NH3 volatilization and deposition predominantly occur. By comparing the estimated release with the average atmospheric NH3 concentrations in northeastern China51—4.83 µg/m3 in spring and 8.44 µg/m3 in summer—NH3 released through rainfall evaporation accounted for approximately 4.14% of the total NH3 concentration in spring and 7.70% of the total NH3 concentration in summer. This further corroborated the phenomenon whereby NH3 surges near the ground surface within 1–2 hours after precipitation.

The Frac (NH3) for each precipitation event was calculated via Eq. (7). If Frac (NH3) ≥ 1, all NH4+ is released as NH3 into the atmosphere. If 0 < Frac (NH3) < 1, part of the NH4+ is released as NH3, while the remaining NH4+ forms ammonium salts with SO42−, Cl−, and NO3−, which are left as residues. If Frac (NH3) < 0, all NH4+ remains in the form of ammonium salts, with no NH3 released. The experimentally obtained relationship between R and Frac (NH3) is shown in Fig. 5. The fitting coefficient (R2 was 0.92, indicating a strong correlation. The observed discrepancy may be due to the failure to account for small amounts of formate, acetate, and other low-molecular-weight organic acids in the samples, which could slightly overestimate the theoretical values compared with the actual values17.

Factors influencing the NH4 + conversion rate during the evaporation of different types of precipitation

Solution evaporation is a complex process involving both chemical and physical mechanisms, with outcomes varying significantly depending on environmental conditions. Takenaka et al. (2009) reported that when an ammonium acetate solution rapidly evaporates at high temperatures (100 °C), the solute tends to deposit as a solid on the contact surface. In contrast, when the solution evaporates slowly at room temperature, the solute is released primarily in the gas phase, with minimal solid residue remaining on the surface. These findings indicate that the drying rate of the solution significantly influences the final fate of the solute; evaporation rates are affected by various meteorological factors, including temperature, wind speed, and droplet size19. To further investigate the effects of temperature, wind speed, and droplet size on the NH4+ conversion rate during the evaporation of different types of precipitation, this study utilized natural precipitation samples collected on April 15, April 24, August 22, and July 22, representing HZ, DS, CC, and MN, respectively. Indoor simulation experiments were conducted to measure the R value under various experimental conditions. The results provide new insights into the dynamic characteristics of nitrogen cycling during precipitation evaporation and its broader environmental implications.

Effects of temperature on the NH4 + conversion rate during the evaporation of different precipitation types

As shown in Fig. 6, the temperature significantly influenced R during the evaporation of different types of precipitation, with a consistent pattern across all types. Overall, R increased to a peak and then decreased with increasing temperature, suggesting that temperatures within a specific range promoted the conversion of NH4+ to NH3. However, excessively high temperatures may trigger adverse reactions, further increasing the conversion rate. At low temperatures (T ≤ 10 °C), R was generally low. As the temperature increased from 10 °C to 25 °C, R increased significantly, peaking at 25 °C. This increase was likely due to the high concentrations of NO3− and NH4+ in the precipitation, which, under optimal conditions, combined to form secondary ammonium salts (NH4NO3). These ammonium salts are thermally unstable and particularly sensitive to temperature changes. Studies have shown that when the temperature is between 5 °C and 25 °C and the relative humidity exceeds 40%, increasing the temperature accelerates the decomposition of ammonium salts, shifting the reaction equilibrium toward NH3 release, which significantly enhances the ammonia flux and increases R52. From a molecular dynamics perspective, higher temperatures increase molecular motion in solution, increasing the distance between molecules and weakening intermolecular interactions. This reduction in NH3 solubility in solution facilitated the conversion of NH4+ into NH3, allowing it to escape more readily from the solution53. However, as the temperature continued to rise, R decreased, reaching a minimum at 35 °C. This was likely due to the increased evaporation rate at higher temperatures, which caused water molecules to evaporate more rapidly48. Rapid evaporation increased the concentration of solutes in solution, leading to the precipitation of poorly soluble salts once their solubility limit was reached, removing them from the evaporation process. Concurrently, ions with higher solubilities, such as NH4+ and NO2−, remained dissolved and continued to react to form NH4NO2. NH4NO2 tends to decompose into N2 and H2O at relatively high temperatures19 leading to the consumption of NH4+ and a further decrease in R.

A comparison of different samples revealed significant systematic differences in R during evaporation across the entire temperature range. The conversion rates followed the order HZ > DS > CC > MN (P < 0.05), reflecting the varying effects of the chemical composition of different precipitation types on R. This difference can be attributed to the combined effects of pH, excess nonvolatile anions, and the initial concentration of NH4+ in the precipitation54. A relatively high pH typically favors the conversion of NH4+ to NH3. However, the presence of excess nonvolatile anions in precipitation shifts the chemical equilibrium, reducing R19. Additionally, the initial concentration of NH4+ has a complex effect on the conversion rate25. A higher initial concentration provides more NH4+ but also amplifies the inhibitory effect of nonvolatile anions, further decreasing R. Although the pH of HZ was lower than those of the other precipitation types, the presence of excess nonvolatile anions and a moderate NH4+ concentration contributed to its higher R value. In contrast, DS and CC exhibited a stronger inhibitory effect from excess nonvolatile anions, which prevented these samples from achieving high R values, despite having higher pH values. Finally, MN, with the lowest initial NH4+ concentration and a low pH, presented the lowest R value during evaporation.

Effect of wind speed on the NH4 + conversion rate during the evaporation of different precipitation types

As shown in Fig. 7, the R values during the evaporation of the four different types of precipitation ranged between 20% and 80%, exhibiting a significant decreasing trend with increasing WS. Specifically, R was negatively correlated with WS (P < 0.05). This trend indicated that wind speed had a pronounced inhibitory effect on the conversion of NH4+ to NH3 during precipitation evaporation. The main reason for this may be that an increase in the wind speed altered the microenvironment of the solution. On the one hand, higher wind speeds accelerated evaporation at the solution surface, and the cooling effect during evaporation lowered the surface temperature. Under these lower temperature conditions, NH4+ tends to combine with acidic substances in solution to form ammonium salts, which remain in the liquid phase rather than being released as a gas. This resulted in a significant decrease in R with increasing wind speed55. On the other hand, increased wind speed reduced the thickness of the stagnant boundary layer at the gas‒liquid interface, making it easier for water molecules to diffuse into the gas phase. This phenomenon accelerated evaporation, causing the concentration of solutes to gradually increase. As a result, some poorly soluble metal salts may have crystallized out due to supersaturation, limiting the escape of NH4+ to the gas phase and causing R to decrease progressively.

In addition, all types of precipitation presented different rates of decrease in R across the range of wind speeds, which were influenced mainly by the initial NH4+ concentration and solution saturation. Under calm wind or near-still conditions (wind speed = 0 m/s), the R value of CC was the highest and decreased most rapidly. When the wind speed increased to 3 m/s, R decreased to 19.12%, which was only one quarter of the rate under calm conditions. This suggested that CC was the most sensitive precipitation type to wind speed changes, with its evaporation highly dependent on disturbances at the gas‒liquid interface. Upon closer analysis, although CC had a low total ion concentration, resulting in low solution saturation, its significantly lower NH4+ concentration reduced the inhibitory effect of excess NH4+ on R25 allowing R to vary significantly with changes in wind speed. In contrast, MN exhibited a more stable decreasing trend under different wind speeds, with a difference of only 29.01% between the maximum and minimum conversion rates, indicating that MN was the precipitation type least affected by wind speed changes. This was likely due to the low NH4+ concentration and low solution saturation of MN, which weakened the impact of wind speed on its conversion rate. DS, with the highest solution saturation, showed a greater degree of wind speed-induced variation, although it was still lower than that of CC. Its decline pattern was characterized by an initial rapid decrease followed by a more gradual flattening. HZ, with NH4+ and total ion concentrations intermediate between those of DS and MN, displayed a relatively uniform decreasing pattern, and its response to wind speed changes was also intermediate. Overall, owing to differences in initial NH4+ concentration and solution saturation, the response of R to variations in wind speed differed among the precipitation types, with the order from high to low being CC > DS > HZ > MN (P < 0.05). These differences highlight the driving effect of wind speed on the conversion of NH4+ to NH3 during precipitation evaporation and its underlying mechanisms.

Effect of the precipitation amount on the NH4 + conversion rate during the evaporation of different types of precipitation

The factors influencing solution evaporation include not only meteorological conditions such as temperature, wind speed, relative humidity, and solar radiation but also solution factors such as droplet size and solute concentration56. As shown in Fig. 8, the NH3 release and R results for the different types of precipitation at different sample volumes revealed similar patterns across all precipitation types. Specifically, for 0.5 mL of precipitation, the amount of NH3 released after evaporation ranged from 0.4 to 1.4 mg/L, while the R values remained between 60% and 75%. However, as the sample volume increased to 5 mL, the NH3 release increased to 1.5–5.5 mg/L, whereas R significantly decreased to less than 30%. This suggested that increasing the sample volume significantly inhibited the conversion of NH4+ to NH3 during evaporation, with a negative correlation observed between the two factors (P < 0.05). By calculating the ratio of nonvolatile anions to nonvolatile cations in the samples, it was found that excess nonvolatile anions were present in all types of precipitation. As the sample volume increased, excess nonvolatile anions gradually accumulated in the solution, inhibiting the conversion of NH4+ and resulting in a decrease in R. Moreover, as evaporation progressed, the reduction in water molecules caused metal cations in the precipitate to combine with nonvolatile anions such as SO42−, NO3−, and Cl−, forming salts with low solubility that exited the evaporation system as crystals. This weakened the promoting effect of metal cations on NH4+ conversion, leading to the observed decline in R with increasing sample volume. On the other hand, NH3 release clearly increased with increasing sample volume, indicating a positive correlation between sample volume and NH3 release (P < 0.05). This resulted from the increased NH4+ concentration in the precipitate as the sample volume increased, leading to more NH3 being released after evaporation. Furthermore, the NH3 release levels for the different types of precipitation followed the order DS > HZ > CC > MN (P < 0.05), which was closely related to the initial NH4+ content in the precipitation.

Temperature coefficient, wind speed coefficient, and precipitation amount coefficient affect NH3 release

On the basis of the results of the indoor simulation experiments conducted under different meteorological conditions to determine R, as well as the Frac (NH3) values calculated via Eq. (7), the temperature coefficient (K1), wind speed coefficient (K2), and precipitation amount coefficient (K3) affecting NH4+ conversion during precipitation evaporation were further calculated via Eq. (8) (Table 2). The results showed that R was controlled not only by the chemical parameters of precipitation, such as ion concentration and pH but also by meteorological conditions. Specifically, with the same chemical parameter values, the total NH3 release during precipitation evaporation in moderate-temperature regions may be greater than that in colder or hotter regions, whereas the F value of precipitation in areas with mild winds and an arid climate may be lower than that in regions with strong winds and heavy rainfall. Therefore, the R values in different regions are constrained by both the chemical composition of precipitation and the local meteorological conditions, resulting in significant differences in the total NH3 flux released after the evaporation of precipitation across various regions.

By comprehensively considering the impacts of temperature, wind speed, and precipitation amount and quantitatively analyzing these factors, the changes in NH3 flux under different spatial and temporal conditions can be predicted more accurately. This study provides valuable data for subsequent research and serves as a scientific basis for optimizing environmental management measures.

Conclusions

This study revealed that all precipitation types exhibited nonacidic characteristics and were dominated by water-soluble ions such as SO42−, NO3−, Ca2+, and NH4+. Significant differences were observed in the NH4+ conversion rates among the precipitation types, and the release of NH3 exhibited clear seasonal pattern. Meteorological factors, including temperature, wind speed, and precipitation, play critical roles in influencing NH3 volatilization. In addition, the NH3 fluxes released from precipitation evaporation were 20.33 µg/m2 in spring and 64.53 µg/m2 in summer, accounting for approximately 4.14% and 7.70%, respectively, of the corresponding atmospheric NH3 concentrations.

By integrating chemical composition analysis with meteorological analysis, this study offers a novel approach to quantify NH3 release from precipitation evaporation at local scales. These findings underscore the importance of precipitation evaporation as a nonnegligible source of atmospheric NH3 and provide a scientific basis for improving ammonia emission inventories and atmospheric nitrogen management strategies.

This study is limited by a relatively small sample size and the absence of surface-level interactions under field conditions. Key environments factors such as relative humidity and photochemical processes were not considered, which may constrain the spatial applicability of the results. Moreover, in natural settings, post-depositional interactions with land, vegetation, and water bodies can alter NH4+ concentrations and pH, thereby influencing NH3 volatilization. Future research should incorporate field observations, large datasets, and coupled modeling approaches to capture a broader range of environmental variables and improve the mechanistic understanding of NH4+ to NH3 conversion under complex atmospheric and surface-mediated conditions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Meng, Z., Lin, W., Zhang, R., Han, Z. & Jia, X. Summertime ambient ammonia and its effects on ammonium aerosol in urban beijing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 579, 1521–1530 (2017).

Gunthe, S. S. et al. Enhanced aerosol particle growth sustained by high continental Chlorine emission in India. Nat. Geosci. 14, 77–84 (2021).

Hu, M. et al. Acidic gases, ammonia and water-soluble ions in PM2.5 at a coastal site in the Pearl river delta, China. Atmos. Environ. 42, 6310–6320 (2008).

Huang, R. J. et al. High secondary aerosol contribution to particulate pollution during haze events in China. Nature 514, 218–222 (2014).

Sun, Y. et al. Investigation of the sources and evolution processes of severe haze pollution in Beijing in January 2013. JGR Atmos. 119, 4380–4398 (2014).

Tao, J. et al. Chemical and optical characteristics of atmospheric aerosols in Beijing during the Asia-Pacific economic Cooperation China 2014. Atmos. Environ. 144, 8–16 (2016).

Lelieveld, J., Evans, J. S., Fnais, M., Giannadaki, D. & Pozzer, A. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature 525, 367–371 (2015).

Höpfner, M. et al. Ammonium nitrate particles formed in upper troposphere from ground ammonia sources during Asian monsoons. Nat. Geosci. 12, 608–612 (2019).

Galloway, J. N. et al. Nitrogen cycles: past, present, and future. Biogeochemistry 70, 153–226 (2004).

Fuzzi, S. et al. Particulate matter, air quality and climate: lessons learned and future needs. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 8217–8299 (2015).

Warner, J. X. et al. Increased atmospheric ammonia over the world’s major agricultural areas detected from space. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 2875–2884 (2017).

Chang, Y. et al. Assessing contributions of agricultural and nonagricultural emissions to atmospheric ammonia in a Chinese megacity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 1822–1833 (2019).

Fu, H., Luo, Z. & Hu, S. A temporal-spatial analysis and future trends of ammonia emissions in China. Sci. Total Environ. 731, 138897 (2020).

Suarez-Bertoa, R., Zardini, A. A. & Astorga, C. Ammonia exhaust emissions from spark ignition vehicles over the new European driving cycle. Atmos. Environ. 97, 43–53 (2014).

Li, Y. C. et al. Chemical characteristics of rainwater in Sichuan basin, a case study of ya’an. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 23, 13088–13099 (2016).

Pan, Y. et al. Fossil fuel Combustion-Related emissions dominate atmospheric ammonia sources during severe haze episodes: evidence from15 N-Stable isotope in Size-Resolved aerosol ammonium. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 8049–8056 (2016).

Wentworth, G. R., Murphy, J. G., Benedict, K. B., Bangs, E. J. & Collett, J. L. Jr. The role of dew as a night-time reservoir and morning source for atmospheric ammonia. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 7435–7449 (2016).

Ravan, P., Ahmady-Birgani, H., Solomos, S., Yassin, M. F. & Abasalinezhad, H. Wet Scavenging in Removing Chemical Compositions and Aerosols: A Case Study Over the Lake Urmia. JGR Atmospheres 127, eJD035896 (2022). (2021).

Takenaka, N. et al. The chemistry of drying an aqueous solution of salts. J. Phys. Chem. A. 113, 12233–12242 (2009).

Zheng, L. Study on the Chemical Characteristics and Sources of Acid Precipitation in Dalian (Dalian University of Technology, 2013). (in Chinese with English abstract).

Liang, Y., Jiang, H. & Liu, X. Characteristics of atmospheric ammonia and its impacts on SNA formation in PM2.5 of nanchang, China. Atmospheric Pollution Res. 15, 102059 (2024).

Zeng, J. et al. Chemical evolution of rainfall in china’s first eco-civilization demonstration city: implication for the provenance identification of pollutants and rainwater acid neutralization. Sci. Total Environ. 910, 168567 (2024).

Huang, R. J. et al. Contrasting sources and processes of particulate species in haze days with low and high relative humidity in wintertime Beijing. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 9101–9114 (2020).

Xu, Z. et al. Chemical composition of rainwater and the acid neutralizing effect at Beijing and Chizhou city, China. Atmos. Res. 164–165, 278–285 (2015).

Dou, Y. Study on the release process of NH3 during dew evaporation stage, Jilin Jianzhu University, (2023). doi:10.27714/d.cnki.gjljs.2022.000213. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Wang, L. et al. Water-soluble ions and oxygen isotope in precipitation over a site in Northeastern Tibetan plateau, China. J. Atmos. Chem. 76, 229–243 (2019).

Xu, Y., Jia, C., Dou, Y., Yang, X. & Yi, Y. Flux of NH3 release from dew evaporation in downtown and suburban changchun, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 30, 85305–85317 (2023).

Muselli, M. et al. Chemical and biological characteristics of dew and rainwater during the dry season of tropical Islands. Atmosphere 12, 69 (2021).

Atekwana, E., Atekwana, E., Rowe, R., Werkemajr, D. & Legall, F. The relationship of total dissolved solids measurements to bulk electrical conductivity in an aquifer contaminated with hydrocarbon. J. Appl. Geophys. 56, 281–294 (2004).

Rolph, G., Stein, A. & Stunder, B. Real-time environmental applications and display sYstem: READY. Environ. Model. Softw. 95, 210–228 (2017).

Stein, A. F. et al. NOAA’s HYSPLIT atmospheric transport and dispersion modeling system. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 96, 2059–2077 (2015).

Wu, D. et al. The influence of dust events on precipitation acidity in China. Atmos. Environ. 79, 138–146 (2013).

Su, Z. et al. Acid deposition and meteorological factors together drive changes in vegetation cover in acid rain areas. Ecol. Ind. 167, 112720 (2024).

Tang, J., Xu, X., Ba, J. & Wang, S. Trends of the precipitation acidity over China during 1992–2006. Chin. Sci. Bull. 55, 1800–1807 (2010).

Li, Z. J., Song, L. L., Ma, J. & Li, Y. The characteristics changes of pH and EC of atmospheric precipitation and analysis on the source of acid rain in the source area of the Yangtze river from 2010 to 2015. Atmos. Environ. 156, 61–69 (2017).

Zhang, L. et al. Chemical characteristics of long-term acid rain and its impact on lake water chemistry: A case study in Southwest China. J. Environ. Sci. 138, 121–131 (2024).

Song, L. et al. Distinct evolutions of haze pollution from winter to the following spring over the North China plain: role of the North Atlantic sea surface temperature anomalies. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 1669–1688 (2022).

Chen, S. et al. Inter-annual variation of the spring haze pollution over the North China plain: roles of atmospheric circulation and sea surface temperature. Int. J. Climatol. 39, 783–798 (2019).

Al-Khashman, O. A. Ionic composition of wet precipitation in the Petra region, Jordan. Atmos. Res. 78, 1–12 (2005).

Facchini Cerqueira, M. R. et al. Chemical characteristics of rainwater at a southeastern site of Brazil. Atmospheric Pollution Res. 5, 253–261 (2014).

Huang, L., Yuan, C. S., Wang, G. & Wang, K. Chemical characteristics and source apportionment of PM10 during a brown haze episode in harbin, China. Particuology 9, 32–38 (2011).

Qu, R. & Han, G. A critical review of the variation in rainwater acidity in 24 Chinese cities during 1982–2018. Elementa: Sci. Anthropocene. 9, 00142 (2021).

Rao, P. S. P. et al. Sources of chemical species in rainwater during monsoon and non-monsoonal periods over two mega cities in India and dominant source region of secondary aerosols. Atmos. Environ. 146, 90–99 (2016).

Masood, S. S. et al. Influence of urban–coastal activities on organic acids and major ion chemistry of wet precipitation at a metropolis in Pakistan. Arab. J. Geosci. 11, 802 (2018).

Huang, K., Zhuang, G., Xu, C., Wang, Y. & Tang, A. The chemistry of the severe acidic precipitation in shanghai, China. Atmos. Res. 89, 149–160 (2008).

Luo, B. & Liu, X. Study on the sources of atmospheric pollution in Hefei based on backward trajectory model. J. Univ. Sci. Technol. China. 49, 321–328 (2019). (in Chinese with English abstract).

Sutton, M. A. et al. Towards a climate-dependent paradigm of ammonia emission and deposition. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 368, 20130166 (2013).

Seinfeld, J. H. & Pandis, S. N. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: from Air Pollution To Climate Change (Wiley, 2016).

Mozurkewich, M. The dissociation constant of ammonium nitrate and its dependence on temperature, relative humidity and particle size. Atmospheric Environ. Part. Gen. Top. 27, 261–270 (1993).

Nakayoshi, M., Moriwaki, R., Kawai, T. & Kanda, M. Experimental study on rainfall interception over an outdoor urban-scale model. Water Resour. Res. 45, W04415 (2009).

Dou, Y. & Xu, Y. Research progress on atmospheric ammonia concentration, sources, and hazards. Petrochemical Technol. 29, 178–180 (2022). (in Chinese with English abstract).

Allen, A. G., Harrison, R. M. & Erisman, J. W. Field measurements of the dissociation of ammonium nitrate and ammonium chloride aerosols. Atmospheric Environment () 23, 1591–1599 (1989).) 23, 1591–1599 (1989). (1967).

Atkins, P. W., Paula, J. D. & Keeler, J. Atkins’ Physical Chemistry (Oxford University Press, 2018).

Liu, L. et al. Ammonia volatilization as the major nitrogen loss pathway in dryland agro-ecosystems. Environ. Pollut. 265, 114862 (2020).

Wang, S. et al. Atmospheric ammonia and its impacts on regional air quality over the megacity of shanghai, China. Sci. Rep. 5, 15842 (2015).

Dao, V. D., Vu, N. H., Dang, T., Yun, S. & H.-L. & Recent advances and challenges for water evaporation-induced electricity toward applications. Nano Energy. 85, 105979 (2021).

Funding

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province (YDZJ202401369ZYTS) and National Nature Science Foundation of China (42175140).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in the conception and design of the study. Xiaoteng Liu, Yingying Xu and Hongsheng Jia were responsible for material preparation, data collection, and analysis. Xiaoteng Liu took the lead in drafting the manuscript, while all authors provided critical comments on previous versions. Yachao Zhang, Yunze Zhao and Haodong Hou offered editorial suggestions. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Xu, Y., Jia, H. et al. NH3 release during the evaporation of different types of atmospheric precipitation: A case study in Changchun, China. Sci Rep 15, 31117 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15872-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15872-2