Abstract

Accurate digital impressions are crucial in modern dentistry, particularly for capturing fine details of various dental preparations. This study aimed to evaluate the effect of variations in the sizes of crown and inlay specimen on the accuracy of three digital impression techniques. Nine crown and nine inlay specimens were fabricated according to American Dental Association Standard No. 132. Gold standard measurements were obtained using a coordinate-measuring machine. Digitized files were generated using three impression techniques (n = 10): intraoral scanner (IOS), extraoral scanner with alginate (EOS-A), and extraoral scanner with silicone rubber (EOS-S). Digital models from EOSs served as reference sets for three-dimensional (3D) fitting analysis. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s post-hoc test. Specimen size variations significantly affected the accuracy of all impression techniques (p < 0.05). IOS exhibited superior accuracy across all specimens, with most trueness values falling within the clinical threshold. EOS-S demonstrated moderate trueness, meeting the threshold for most indexes, except the ra index in A2 and C1 crowns. EOS-A met the threshold only for A3 crown. All techniques achieved clinical precision thresholds, except for the rd index of A1 in the EOS-A inlay specimens, for which a slight exceedance was observed. Additionally, 3D fitting analysis revealed more pronounced deviations in the EOS-A group. The accuracy of digital impressions technique is influenced by variations in the size of crowns and inlays. This study highlights the significant impact of specimen size on the accuracy of digital impression techniques, providing valuable insights for enhancing restorative dentistry outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dental impressions are essential for capturing both hard and soft tissues of the oral cavity, providing an accurate representation of anatomical structures1. Traditional impressions utilize trays with impression material to create negative molds, followed by plaster pouring for positive cast fabrication2. Commonly used materials include silicone rubber, alginate, and polyether3. However, dimensional instability of materials and multistep procedural errors may compromise the accuracy of impressions1,3,4,5, thereby affecting the fabrication of restorations.

CAD/CAM technology has revolutionized digital impressions, establishing them as essential components of modern restorative dentistry6. Digital impressions are generally classified into two categories: indirect and direct digital techniques7. Indirect digitization involves scanning a prepared impression with an extraoral scanner (EOS) to create a digital model8, whereas direct digitization employs an intraoral scanner (IOS) to capture digital data directly from the patient’s mouth9. Digital impressions surpass traditional methods in terms of accuracy, patient comfort, and efficiency, leading to their widespread adoption in clinical settings10,11.

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 5725-1:2023 defines “accuracy” as the combination of trueness and precision. Current dental digital impression technologies face significant challenges in accurately capturing complex oral structures. Optical interference can compromise the accuracy of IOSs, particularly in the presence of structural complexities12,13,14. Most studies evaluating the performance of IOS in capturing complex oral conditions have concentrated on concave areas, such as root canals and deep fissures. The structure of the inlay, particularly its depth, significantly affects the scanning accuracy. Studies by Gurpinar et al.15 and de Andrade et al.16 demonstrated that greater inlay depth correlates with reduced scanning accuracy. However, studies on the effects of other tooth preparation structures, particularly changes in crown dimensions, on the accuracy of IOSs remains underexplored. EOS captures a broader range of data than direct digital impression techniques, though material selection affects precision. Silicone-based materials outperform alginate in detail reproduction and dimensional stability due to reduced deformation and shrinkage during scanning17,18,19,20. Existing studies mainly focus on comparing the accuracy of these materials in conventional impression techniques. However, the impact of dimensional variations in crowns and inlays on the accuracy of indirect digital impression techniques remains underexplored, necessitating further research for clinical application.

International standards, including ISO 12836:2015, ISO 20,896, and American Dental Association (ADA) Standard No. 132, provide guidelines for evaluating scanning accuracy. ADA 132 introduces three test objects designed to assess the accuracy of 3D optical metrology systems, including crown and inlay specimens that represent crown and inlay preparations, respectively. In this study, the dimensions of the crown and inlay specimen were modified according to ADA 132 to assess the effect of variations in the size on the accuracy of one direct digital and two indirect digital impression techniques. Specimen dimensions were altered by ± 2 mm in height (or depth) and diameter to simulate clinical variations in permanent teeth. The null hypothesis was that variations in the size of the specimens would not affect the accuracy of the digital impression techniques.

Materials and methods

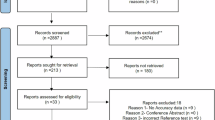

Fabrication of models

Nine crown and nine inlay specimens were designed in accordance with ADA Standard No. 132, with modifications to the upper diameter (ra or rc), lower diameter (rb or rd), and height (h) (or depth (d)) by ± 2 mm to simulate various clinical conditions (Fig. 1). A 2-mm notch was incorporated at one corner of the crown and inlay specimen bases to ensure accurate alignment during the fitting process. The specimens were fabricated using a computer numerical control milling machine (CK-0640, GSK, China) with dental milling blocks (304 stainless steel) via wet milling. The post-processing procedure comprised sequential oil contamination cleaning and burr removal, followed by final sandblasting treatment utilizing 50-µm alumina powders.

Schematic and physical representations of crown and inlay specimens. (Ⅰ) Schematic diagram of the crown specimen. (Ⅱ) Physical images of all crown specimens. (Ⅲ) Schematic diagram of the inlay specimen. (Ⅳ) Physical images of all inlay specimens. The crown models were designed with varying dimensions: A1: ra = 5 mm, rb = 6 mm, h = 4 mm; A2: ra = 7 mm, rb = 8 mm, h = 4 mm; A3: ra = 9 mm, rb = 10 mm, h = 4 mm; B1: ra = 5 mm, rb = 6 mm, h = 6 mm; B2: ra = 7 mm, rb = 8 mm, h = 6 mm; B3: ra = 9 mm, rb = 10 mm, h = 6 mm; C1: ra = 5 mm, rb = 6 mm, h = 8 mm; C2: ra = 7 mm, rb = 8 mm, h = 8 mm; C3: ra = 9 mm, rb = 10 mm, h = 8 mm. The inlay models were designed with varying dimensions: A1: rc = 5 mm, rd = 6 mm, d = 4 mm; A2: rc = 7 mm, rd = 8 mm, d = 4 mm; A3: rc = 9 mm, rd = 10 mm, d = 4 mm; B1: rc = 5 mm, rd = 6 mm, d = 6 mm; B2: rc = 7 mm, rd = 8 mm, d = 6 mm; B3: rc = 9 mm, rd = 10 mm, d = 6 mm; C1: rc = 5 mm, rd = 6 mm, d = 8 mm; C2: rc = 7 mm, rd = 8 mm, d = 8 mm; C3: rc = 9 mm, rd = 10 mm, d = 8 mm.

Measurement of the gold standard

A coordinate measuring machine (CMM, Axiom Too CNC, Aberlink, UK) with a probe head (PH10T, Aberlink, UK) was used to measure the indexes of the specimens, as shown in Fig. 1 (scale resolution: 0.5 μm). Each specimen was measured 10 times, and the mean values were established as the gold standard.

Acquisition of reference model data

Each crown and inlay specimen was scanned 10 times using an EOS (E4, 3Shape, Denmark). The acquired datasets were converted into the STL format and imported into Geomagic Control X 2020 (3D SYSTEMS, USA) for indicator measurement. The measurements from each dataset were compared with those obtained by the CMM, and the dataset with the closest match was designated as the reference models (RMs).

Acquisition of experimental group data

Two scanners were used for data collection: an IOS (TRIOS SERIES3, 3Shape, Denmark) and an EOS (E4, 3Shape, Denmark). All intraoral scans were conducted by a single trained operator under D65 illumination conditions. The scanning protocol utilized AI-assisted single-crown mode with 500 image captures per specimen. Prior to each scanning session, both color and orientation calibrations were performed using a Color Calibration Target (TRIOS SERIES3, 3Shape, Denmark). All impressions were made by another dental technician. The experimental groups were divided into three categories:

-

Group IOS: Each model was scanned using the IOS 10 times, with 30-s intervals between scans.

-

Group EOS with alginate (EOS-A): Custom stainless steel cylindrical trays (25 mm diameter × 20 mm height) were fabricated with uniformly distributed perforations (1.5 mm diameter) across their surface. Alginate impressions were prepared using Heraplast alginate (KULZER, Germany), mixed at a ratio of 10 g powder to 23 mL distilled water as recommended by the manufacturer. Following 30 s of stirring to achieve homogeneity, the mixture was transferred to the tray and positioned on the specimen. A 10 N vertical force was applied for 3 min, after which the impression was directly scanned with EOS. Ten impressions were fabricated for each dimension.

-

Group EOS with silicone rubber (EOS-S): Two-step silicone impressions were obtained using a heavy-body and light-body silicone rubber system (3 M ESPE, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The heavy-body silicone was loaded into the tray and seated onto the specimen under a constant force of 10 N for 3 min. After removal, the impression was internally filled with light-body silicone using a mixing gun (HAITUO, China), reseated, and held under the same pressure for 6 min. Subsequently, the impression was directly scanned with EOS. Ten impressions were fabricated for each dimension.

All datasets were exported in the STL format and analyzed using Geomagic Control X 2020 (3D SYSTEMS, USA).

Data processing

According to ISO 5725-1:2023, accuracy is defined as a combination of trueness and precision. Trueness refers to the closeness of a measurement to the true value, whereas precision measures the consistency of repeated measurements. The correlation error was used to quantify both trueness (expressed as relative errors) and precision (expressed as relevant errors):

Relative errors: ∆dM = |(dR−dM)/dR|.

Relevant errors: ∆S(dM) = |S(dM)/dR|.

where dR is the reference value, dM is the measured value, and S is the standard deviation.

3D fitting analysis

The STL files from the experimental groups were designated as scanning models (SMs) and fitted to the RMs to assess the accuracy. The initial alignment was followed by a best-fit alignment to minimize deviations. 3D comparisons were conducted, and color-difference maps were generated. The accuracy range was set between − 0.01 and 0.01, with green used as the default color indicator.

Statistical analysis

A one‑way ANOVA was conducted to assess the effect of specimen size (nine levels corresponding to A₁–C₃) on the trueness values (the dependent variable) obtained for each scanning method and measurement parameter (ra, rb, or h), followed by Tukey’s post‑hoc multiple comparison test (α = 0.05). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of the data distribution. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS Statistics (v25, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Trueness

Figures 2, 3 and 4 present the relative errors (trueness) of the IOS, EOS-A, and EOS-S groups across the nine crown and inlay specimens. Statistically significant differences were observed between the different sizes (p < 0.05). The IOS group achieved the best trueness, followed by the EOS-S and EOS-A groups. In the IOS group, all measurements across various inlay and crown specimens were within the clinical threshold of 0.01. Regarding the “h” index for crowns, specimens with the smaller diameters at the same height (A1, B1, C1) demonstrated significantly better trueness (p < 0.05). In the EOS-S group, all specimens, except for crown specimens A2 and C1, were within the clinical threshold. In contrast, in the EOS-A group, only crown specimen A3 met the clinical threshold. In crown specimens, both “ra” and “rb” indexes showed improved trueness with increasing diameters at the same height (p < 0.05), whereas specimens with smaller diameters at the same height (A1, B1, C1) exhibited the worst trueness values for the “h” index (p < 0.05). The general trend of the inlay specimens is comparable to that of the crown specimens, and the overall trueness of the inlay specimens was lower than that of the crown specimens.

Precision

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the relevant errors (precision) for the IOS, EOS-A, and EOS-S groups across the nine crown and nine inlay specimens. The IOS group demonstrated the highest precision, followed by the EOS-S group, whereas the EOS-A group exhibited the lowest precision for both the crown and inlay specimens. Notably, all groups maintained precision values within the clinical threshold (0.01), except for the “rd” index of A1 in the inlay specimens of the EOS-A group, where the threshold was slightly exceeded.

3D fitting analysis

Figure 5 illustrates the results of the 3D fitting analysis of the crown and inlay specimens. The IOS group demonstrated the highest fitting accuracy, followed by the EOS-S and EOS-A groups. The crown specimens in the EOS-A and EOS-S groups primarily exhibited blue negative deviations on the upper surface, whereas the inlay models showed similar negative deviations on the lower surface. The sidewalls predominantly exhibited positive deviations, particularly in the EOS-A group.

Discussion

The results of this study indicated that dimensional variations in crowns and inlays significantly affect the accuracy of both indirect and direct digital impression techniques. Consequently, the null hypothesis is rejected.

Statistically, the average crown length of human permanent teeth ranges from 7.1 to 11.1 mm, whereas the average crown width ranges from 5.4 to 11.1 mm. Furthermore, an effective preparation design for crowns and inlays is essential to achieve optimal outcomes in restorative dentistry. This includes facilitating adequate support under stress conditions and ensuring a rational distribution of stresses to enhance fracture resistance21,22. The actual sizes of the prepared crowns and inlays can vary owing to differences in the dental conditions among clinical patients. Therefore, in this study, the model parameters were adjusted by ± 2 mm in accordance with ADA 132 to accurately simulate the various sizes of crowns and inlays that may be encountered in a clinical setting.

According to Schmidt et al.23, the larger scanning range of the IOS for crown models leads to an increase in the number of images, which, in turn, causes image-stitching distortion. Therefore, a higher-crown model corresponds to a larger scanning range and lower accuracy. For inlay specimens, Khaled et al.24 prepared inlays with gingival floor depths of 3 and 4 mm and found that the preparation depth had no significant effect on scanning accuracy. This suggests that within a certain depth range, the scanner’s ability to capture accurate data may not be compromised by depth variations. However, Park et al.25 observed the opposite, noting that precision decreased with increasing inlay depth, with depths tested from 1 to 2 mm. These discrepancies may stem from differences in the inlay depths, shapes, or experimental conditions. In the present study, inlay depth had no significant impact on scanning precision, which remained within clinically acceptable thresholds for all results. This is likely because the depths tested in this study were all within the focal depth range of the intraoral scanner. However, this does not imply that deeper inlays do not pose challenges. In fact, deeper areas showed greater deviations in the 3D fitting analysis, indicating that depth can affect scanning precision. This aligns with the findings of Emam et al.26, who showed that depth variations can influence scanning accuracy, emphasizing the need to consider the impact of depth in dental scanning. Furthermore, inlays with complex geometries can lead to increased deviations in scanning accuracy. This is due to intensified light reflection, attenuation, and scattering, which are particularly problematic in deep cavities and narrow channels. These optical phenomena disrupt light reflection and hinder the scanner’s ability to capture accurate data27.

The accuracy of both indirect digital impression techniques was lower than that of the direct digital impression technique. The results of this study indicated that EOS-S exhibited higher accuracy than EOS-A for both crowns and inlays. German et al.28 demonstrated that the detail reproduction ability of impression materials is closely related to their rheological properties. Specifically, higher fluidity is correlated with improved detail reproduction ability17. Silicone rubber exhibits superior fluidity compared with alginate, which is more susceptible to alterations in impression dimensions owing to factors such as dehydration shrinkage, evaporation, and water absorption29. This may explain the better trueness observed in the EOS-S group. Figure 3 and 4 demonstrates that both EOS-A and EOS-S follow a similar trueness trend: for “h”, an increase in diameter at a constant height leads to an increase in the value of trueness. Furthermore, Fig. 5 indicates that crowns of identical height but larger diameters exhibit greater deviation. This phenomenon can be attributed to the increased contact area between the impression material and the model, which results in a stronger hindering effect when the model is removed, leading to a dimensional change in height. In addition, silicone rubber exhibits superior stress tolerance and elastic recovery compared with alginate19,20. This explains why the EOS-S group was less affected by diameter size than the EOS-A group and why the EOS-S group demonstrated fewer deviation for both crowns and inlays, as illustrated in Fig. 5. For “ra” and “rb,” specimens with smaller diameters exhibited worse trueness at the same height. Notably, crown specimens created using the indirect digital impression technique were derived by scanning the recessed areas. The EOS generates a virtual 3D surface by projecting light onto the impression surface, with the reflected light captured by a sensor. However, a reduced diameter can obstruct light projection and reflection because of the narrow lumen, potentially resulting in inaccurate digitization of points30. Furthermore, the properties of the impression material, including fluidity and viscosity, critically influence its accuracy. These properties may limit the material’s ability to flow into narrow areas, thereby impairing its ability to capture fine details, and ultimately compromising impression precision20.

Similarly, for inlays, the data obtained from indirect digital impression techniques were derived by scanning the raised areas of the specimens. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the EOS-A group exhibited a yellow deviation on the sidewalls and a blue deviation on the bottom surface. During the solidification of alginate, pressure applied to the tray may induce stress, which, when released upon model removal, can lead to dimensional changes in the impression18. In this study, the failure rate of inlay impressions was higher than that of crown impressions. Most failures occurred at the fracture point of the raised portion of the negative mold, where it connected to the bottom surface. This can be attributed to the properties of alginate, a viscoelastic material with rubber-like pliability that adheres tightly to the surface of the models, making its removal challenging. Even in the absence of fractures, the raised section of the negative mold tended to shift from its original position owing to suction, resulting in misalignment.

The results of this study indicated that the relevant errors (precision) were within clinical thresholds for all groups, except for the rd index of A1 in the inlay specimens of the EOS-A group, which slightly exceeded the clinical threshold. This finding suggests that variations in the dimensions of crowns and inlays do not significantly affect the digital reproducibility of the impression techniques. However, no significant correlation was observed between precision and trueness. For example, the rb index of C1 in the crown specimens of the EOS-A group exhibited trueness well above the clinical threshold; however, its precision was measured at 0.001792. This indicates that the discrepancies between the specimen and standard model were not owing to human factors, such as operator-related errors in the impression or scanning process.

The alignment process in Geomagic Control X software employs the least-squares method. First, the centroid of the point cloud is calculated based on the geometric features of the model. Subsequently, the macroscopic orientation of the model is determined through translation and rotation in space by aligning the measured model with the reference model. This approach maximizes the overlap of corresponding microscopic point clouds to ensure optimal alignment. However, for regular geometries with symmetric and repetitive characteristics, these alignment methods may fail to accurately identify and align key features, resulting in misfitting between the surfaces. To address this, a 2-mm notch was introduced in the design of the model used in this study. In the initial alignment phase, the software efficiently determines the spatial orientation of the model through rapid identification of notch positions and morphological characteristics. During the subsequent best-fit phase, the three-dimensional coordinate data of the notches significantly enhance the precision of point cloud matching calculations when employing the least squares method. This computational approach ensures rigorous directional alignment and precise positional correspondence between the experimental model and the reference model within the three-dimensional coordinate system. This design contrasts with the regular model used in previous studies31.

Furthermore, when employing the commonly used fitting error ranges of − 0.05 to 0.05 and − 0.1 to 0.132,33,34, most areas appeared green without significant bias. To capture and analyze smaller errors more sensitively, the fitting error range was reduced to −0.01 to 0.01 in this study. Notably, the 3D comparison results reflected the maximum deviation observed across each part of the 10 samples. Although these results provide valuable insights, they do not represent the absolute accuracy of any individual specimen34.

The present study has some limitations. For instance, the in vitro methods used cannot fully replicate clinical factors such as saliva, tongue, and lips, or environmental conditions such as light, temperature, and humidity35,36. Additionally, this study focused on single-tooth preparations, which may not fully represent clinical scanning conditions where neighboring structures could affect accessibility or introduce scanning artifacts. The stainless steel standard model differs significantly from natural dentin and enamel in terms of surface characteristics, including roughness and light reflectivity. Furthermore, this study focused on one IOS, one EOS, and one type each of alginate and silicone. Future research should explore various scanner models and a broader range of impression materials to improve the reliability of these findings.

Conclusion

The size of the crown and inlay specimens significantly influence the accuracy of digital impression techniques. The IOS method demonstrated the highest accuracy, outperforming the other two techniques, with all specimens meeting the clinical threshold. The EOS-S met the clinical threshold for most specimens, exhibiting intermediate accuracy, although the ra index in the A2 and C1 crown specimens exceeded this threshold. In contrast, the EOS-A met the clinical threshold only for A3 in the crown specimen, indicating its limited suitability for scanning crown and inlay specimens, particularly those with small-caliber regions.

Data availability

The data of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

07 January 2026

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34097-x

References

Shah, N. et al. Validation of Digital Impressions’ Accuracy Obtained Using Intraoral and Extraoral Scanners: A Systematic Review. J Clin. Med ;12(18). (2023).

Gjelvold, B., Chrcanovic, B. R., Korduner, E-K., Collin-Bagewitz, I. & Kisch, J. Intraoral digital impression technique compared to conventional impression technique. A randomized clinical trial. J. Prosthodont. 25 (4), 282–287 (2016).

Kong, L., Li, Y. & Liu, Z. Digital versus conventional full-arch impressions in linear and 3D accuracy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of in vivo studies. Clin. Oral Investig. 26 (9), 5625–5642 (2022).

Lee, S. J., Kim, S-W., Lee, J. J. & Cheong, C. W. Comparison of intraoral and extraoral digital scanners: evaluation of surface topography and precision. Dent J (Basel) ;8(2). (2020).

Mejia, J. B. C., Wakabayashi, K., Nakamura, T. & Yatani, H. Influence of abutment tooth geometry on the accuracy of conventional. And digital methods of obtaining dental impressions. J. Prosthet. Dent. 118 (3), 392–399 (2017).

Kim, J-E., Amelya, A., Shin, Y. & Shim, J-S. Accuracy of intraoral digital impressions using an artificial landmark. J. Prosthet. Dent. 117 (6), 755–761 (2017).

de Gonzalez, P., Martinez-Rus, F., Garcia-Orejas, A., Paz Salido, M. & Pradies, G. In vitro comparison of the accuracy (trueness and precision) of six extraoral dental scanners with different scanning technologies. J. Prosthet. Dent. 116 (4), 543–550 (2016).

Marques, S. et al. Digital impressions in implant dentistry: A literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health ;18(3). (2021).

Hou, X. et al. An overview of three-dimensional imaging devices in dentistry. J. Esthet Restor. Dent. 34 (8), 1179–1196 (2022).

Ahmed, S. et al. Digital impressions versus conventional impressions in prosthodontics: A systematic review. Cureus 16 (1), e51537–e51537 (2024).

Punj, A., Bompolaki, D. & Garaicoa, J. Dental impression materials and techniques. Dent. Clin. North. Am. 61 (4), 779–796 (2017).

Gimenez-Gonzalez, B., Setyo, C., Picaza, M. G. & Tribst, J. P. M. Effect of defect size and tooth anatomy in the measurements of a 3D patient monitoring tool. Heliyon ;8(12). (2022).

Park, J-M., Choi, S-A., Myung, J-Y., Chun, Y-S. & Kim, M. Impact of Orthodontic Brackets on the Intraoral Scan Data Accuracy. Biomed Res Int. ;2016. (2016).

Albayrak, B., Sukotjo, C., Wee, A. G., Korkmaz, I. H. & Bayindir, F. Three-Dimensional accuracy of conventional versus digital complete arch implant impressions. J. Prosthodont. 30 (2), 163–170 (2021).

Gurpinar, B. & Tak, O. Effect of pulp chamber depth on the accuracy of endocrown scans made with different intraoral scanners versus an industrial scanner: an in vitro study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 127 (3), 430–437 (2022).

de Andrade, G. S. et al. Impact of different complete coverage onlay Preparation designs and the intraoral scanner on the accuracy of digital scans. J. Prosthet. Dent. 131 (6), 1168–1177 (2024).

Baxter, R. T. et al. Evaluation of outgassing, tear strength, and detail reproduction in alginate substitute materials. Oper. Dent. 37 (5), 540–547 (2012).

Sharif, R. A. et al. The accuracy of gypsum casts obtained from the disinfected extended-pour alginate impressions through prolonged storage times. Bmc Oral Health ;21(1). (2021).

Saini, R. S. et al. Properties of a novel composite elastomeric polymer vinyl polyether siloxane in comparison to its parent materials: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Bmc Oral Health ;24(1). (2024).

Abdelraouf, R. M., Bayoumi, R. E. & Hamdy, T. M. Effect of powder/water ratio variation on viscosity, tear strength and detail reproduction of dental alginate impression material (In vitro and clinical Study). Polymers (Basel) ;13(17). (2021).

Michaud, P-L. & Dort, H. Do onlays and crowns offer similar outcomes to posterior teeth with mesial-occlusal-distal preparations? A systematic review. J. Esthet Restor. Dent. 36 (2), 295–302 (2024).

Saker, S. et al. The influence of ferrule design and pulpal extensions on the accuracy of fit and the fracture resistance of Zirconia-Reinforced lithium silicate endocrowns. Materials (Basel) ;17(6). (2024).

Klussmann, S. A., Woestmann, L. & Schlenz, B. MA. Accuracy of digital and conventional Full-Arch impressions in patients: an update. J Clin. Med ;9(3). (2020).

Khaled, M., Sabet, A., Ebeid, K. & Salah, T. Effect of different Preparation depths for an inlay-Retained fixed partial denture on the accuracy of different intraoral scanners: an in vitro study. J. Prosthodont. 31 (7), 601–605 (2022).

Park, Y., Kim, J-H., Park, J-K. & Son, S-A. Scanning accuracy of an intraoral scanner according to different inlay Preparation designs. Bmc Oral Health ;23(1). (2023).

Emam, M., Ghanem, L. & Abdel Sadek, H. M. Effect of different intraoral scanners and post-space depths on the trueness of digital impressions. Dent. Med. Probl. 61 (4), 577–584 (2024).

Park, J-M., Kim, R. J. Y. & Lee, K-W. Comparative reproducibility analysis of 6 intraoral scanners used on complex intracoronal preparations. J. Prosthet. Dent. 123 (1), 113–120 (2020).

German, M. J., Carrick, T. E. & McCabe, J. F. Surface detail reproduction of elastomeric impression materials related to rheological properties. Dent. Mater. 24 (7), 951–956 (2008).

Imbery, T. A., Nehring, J., Janus, C. & Moon, P. C. Accuracy and dimensional stability of extended-pour and conventional alginate impression materials. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 141 (1), 32–39 (2010).

Jacob, H. B., Wyatt, G. D. & Buschang, P. H. Reliability and validity of intraoral and extraoral scanners. Progress Orthodontics ;16. (2015).

Cui, N. et al. Bias Evaluation of the Accuracy of Two Extraoral Scanners and an Intraoral Scanner Based on ADA Standards. Scanning. ;2021. (2021).

Dohiem, M. M., Emam, N. S., Abdallah, M. F. & Abdelaziz, M. S. Accuracy of digital auricular impression using intraoral scanner versus conventional impression technique for ear rehabilitation: A controlled clinical trial. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 75 (11), 4254–4263 (2022).

Schlenz, M. A., Vogler, J., Schmidt, A., Rehmann, P. & Woestmann, B. New intraoral Scanner-Based chairside measurement method to investigate the internal fit of crowns: A clinical trial. Int J. Environ. Res. Public. Health ;17(7). (2020).

Kosago, P., Ungurawasaporn, C. & Kukiattrakoon, B. Comparison of the accuracy between conventional and various digital implant impressions for an implant-supported mandibular complete arch-fixed prosthesis: an in vitro study. J. Prosthodont. 32 (7), 616–624 (2023).

Alkadi, L. A comprehensive review of factors that influence the accuracy of intraoral scanners. Diagnostics (Basel) ;13(21). (2023).

Abduo, J. & Elseyoufi, M. Accuracy of intraoral scanners: A systematic review of influencing factors. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 26 (3), 101–121 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by [Science and Technology Plan Project of Taizhou City, Zhejiang Province (20ywb155)].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.W. contributed to the conceptualization, data analysis, data validation and funding acquisition of the study. H.S. were involved in conceptualization, data analysis, writing and reviewing the manuscript. Y.Q., X.W., J.K., M.C., and Y.X. performed the experiments, collected data and wrote the manuscript. Q.H. conducted visualization. H.B.J. was responsible for data validation. J.M.L. contributed to conceptualization, supervision and revised the manuscript. Q.C. contributed to writing and revising the manuscript and funding acquisition. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error, where a figure and its in-text citation was omitted. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, X., Shao, H., Qi, Y. et al. Impact of crown and inlay size variations on the accuracy of various digital impression techniques. Sci Rep 15, 30487 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15912-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15912-x