Abstract

In highly dynamic vehicular networking scenarios, when Vehicle-to-Infrastructure links and Vehicle-to-Vehicle links share spectrum resources, the traditional distributed resource allocation method lacks global optimization and fails to respond to environmental changes in a timely manner, which leads to low spectral efficiency of the system. A resource allocation method based on federated multi-agent deep reinforcement learning is proposed for Vehicular Networking communication, by fusing Asynchronous Federated Learning (AFL) and Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (MADDPG). Synergistic optimization of resource allocation. First, vehicles as agent dynamically optimize spectrum access, power control, and bandwidth allocation based on local channel states through the collaborative policy of MADDPG to reduce cross-link interference. Second, the asynchronous federation architecture is designed, where vehicles independently upload local model parameters to the global server, dynamically adjust the aggregation weights according to the real-time channel quality, and optimize the update of global model parameters. Finally, the global model parameters are fed back to the vehicles to further optimize the local resource allocation strategy, thus improving the system spectrum efficiency. The simulation results show that the system spectrum efficiency is improved by 19.1% on average compared with the centralized DDPG, MADDPG, MAPPO and FL-DuelingDQN algorithms in the Vehicle Networking scenario, while the transmission success rate of the V2V link is improved by 9.3% on average, and the total capacity of the V2I link is increased by 16.1% on average.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of Intelligent Transportation System (ITS) and Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X1,2), efficient communication among vehicles and between vehicles and infrastructure has become an important support to achieve intelligent driving, vehicle-circuit coordination and traffic optimization. Vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) communication and vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) communication are two core modes in V2X communication. Among them, V2I links need to support high-bandwidth services such as video entertainment, while V2V links need to fulfill low-latency safety requirements such as collision avoidance3. Vehicular networking relies on fixed bandwidth resources in dedicated frequency bands, which is difficult to meet the growing demand for high-density vehicles and diversified services. In order to fully utilize the limited spectrum resources, V2V links need to dynamically multiplex the channel resources allocated to V2I links, which leads to interference and resource competition between the links. In this shared-channel Vehicular Networking environment, how to reasonably allocate communication resources has become an urgent problem to be solved4. In traditional distributed resource allocation methods, due to the lack of a global interference coordination mechanism, individual nodes or agents tend to base their resource allocation on local channel information only, and it is difficult to comprehensively consider the interference situation of the whole system. This leads to a serious impact on the efficiency and fairness of resource allocation in complex vehicular networking environments. Meanwhile, traditional methods usually cannot respond to dynamic changes in the network environment in a timely manner, such as rapid fluctuations in the channel state, sudden changes in user demand, and frequent movement of nodes. This lag makes it difficult for the system to re-optimize the resource allocation strategy in a short period of time, which in turn leads to a reduction in spectrum efficiency and fails to meet the high requirements of real-time and reliability of vehicular networking communication systems.

In recent years, Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) methods have shown great potential in resource allocation optimization in complex dynamic environments. Current research has formed three types of differentiated technology paths based on Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL): first, decentralized DRL architectures achieve local optimization by circumventing global information dependency. Literature5 models the resource allocation of V2I and V2V links as a decentralized DRL problem, which provides a fundamental framework for reducing cross-link interference by differentially designing the state-action space for unicast and broadcast scenarios, so that agents can autonomously select spectrum and power based on local information; Literature6 further extends the approach by introducing decentralized DRL to jointly optimize resource block and power allocation in V2X networks, but its policy stability is insufficient in high-mobility scenarios, and is prone to trigger spectrum resource allocation conflicts. Second, the centralized-distributed hybrid framework attempts to balance global optimization with local performance requirements. Literature7 adopts the “centralized training-decentralized execution” mechanism to solve the channel access and power control problem, and combines it with federated learning to reduce the communication overhead, but its centralized training phase still relies on the global channel state information, which makes it difficult to adapt to dynamic topology changes; Literature8 proposes a distributed multi-agent double-depth Q-learning algorithm for this defect, which realizes sub band-power joint optimization based on local channel information, but fails to effectively alleviate the resource competition contradiction due to the lack of inter-agent collaboration mechanism. Literature9 addresses communication overhead in resource sharing between V2I and V2V links by proposing a federated reinforcement learning framework, FRLPGiA, which achieves distributed aggregation of policy gradients and second-order moments through an inexact ADMM algorithm, enabling V2V links to jointly optimize sub-channel and power selection under conditions that rely only on local observations, and reducing cross-link interference while improving the total V2I rate; Literature10 further aims at spectrum-energy efficiency optimization for heterogeneous V2X networks and designs an action-aware federated multi-agent reinforcement learning framework, which dynamically balances the distribution of reward samples by observing neighborhood agents’ actions and combines random sampling of historical model parameters to enhance the generality of federated aggregation, but spectrum allocation conflicts still exist in high-density scenarios. Finally, the multi-agent collaboration mechanism enhances spectrum coordination by explicitly modelling inter-link interactions. Literature11 transforms the spectrum sharing problem into a multi-agent collaborative task using distributed empirical learning to enable V2V links to autonomously avoid interference, but with insufficient quality of service guarantees for V2I links; Literature12 introduces a heterogeneous QoS priority differentiation mechanism on this basis to optimize the performance of high-priority services through sub band-power allocation, but fails to address the spectral overload problem in high-density scenarios; Literature13 further introduces hysteresis Q-learning with concurrent experience replay (CERT) to capture the channel dynamic characteristics using LSTM networks, which still maintains a high V2V delivery rate in high-speed vehicle movement scenarios, but with limited cross-link interference suppression; Literature14 and literature15 reinforce resource allocation under low latency constraints via an integrated optimization framework and dueling double-depth Q networks, respectively, but neither of them fully considers the dynamic optimal allocation problem specific to resource sharing between V2I and V2V links.

In summary, although existing methods have made some progress in decentralized architecture, and multi-agent collaboration, they still have limitations: existing multi-agent reinforcement learning algorithms usually rely on local collaboration between agents, and lack global optimization, resulting in large fluctuations in spectrum efficiency. The traditional federation aggregation mechanism adopts fixed weights and lacks an effective dynamic adjustment mechanism, which cannot be dynamically adjusted according to the real-time channel conditions and node reliability, thus affecting the resource allocation efficiency and balance.

To address the above problems, this paper proposes a federated multi-agent deep reinforcement learning framework (AFL-MADDPG). Dynamic aggregation of local model parameters with low communication overhead through asynchronous federated learning achieves global experience sharing under distributed architecture. Construct a centralized Critic-distributed Actor collaboration mechanism based on the MADDPG algorithm to learn a dynamic resource allocation strategy among vehicles to adapt to real-time changes in the vehicular network. Design a dynamic weight adjustment mechanism to optimize the global model parameter aggregation weights according to changes in the vehicle communication environment so as to improve the global and local performance.

System model

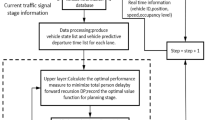

As shown in Fig. 1, the vehicular networking communication scenario considered in this paper consists of a single base station with multiple vehicle users, and according to the different service requirements of V2X communication, the V2I links obtain high-bandwidth services through the cellular interface, while the V2V links transmit security-sensitive data through the (Device-to-Device, D2D) sidechain16. The scenario consists of M V2I links K V2V links and some interference links. The V2I link set and V2V link set are denoted respectively as M = {1,2,…,M} and K = {1,2,…,K}. The system consists of a V2I link with pre-allocated orthogonal sub bands and a V2V link with dynamic access, in which the V2I is transmitted with a fixed power and the V2V needs to adaptively adjust the spectrum access and transmit power. The research objective is to design a continuous action spectrum-power-bandwidth joint optimization allocation scheme to maximize the total capacity of the V2I link and improve the transmission success rate of the V2V link under the premise of suppressing the cross-link interference, so as to enhance the overall spectral efficiency.

Assuming that the channel fading is approximately the same within the same sub band and that the sub bands are independent of each other, where the small-scale fading power component \(h_{k} [m]\) follows an exponential distribution and the frequency-independent large-scale fading is characterized by \(\alpha_{k}\). Then the channel power gain of the kth V2V link on the mth sub band during the coherence time is expressed as:

The Signal to Interference plus Noise Ratio (SINR) of the received signal on the mth channel for the mth V2I link and the kth V2V link are denoted as:

where: \(P_{m}^{c}\) and \(P_{k}^{d} [m]\) denote the transmit power of the mth V2I link and the kth V2V link, respectively; \(\sigma^{2}\) is the noise power; \(g_{k} \left[ m \right]\) denotes the channel gain of the kth V2V link on the mth channel; \(g_{{k,{\text{B}}}} [m]\) denotes the interference channel gain from the kth V2V link to the base station on the mth channel; \(g_{{k^{\prime } ,k}} \left[ m \right]\) denotes the interference channel gain from the k'th V2V link to the kth V2V link on the mth channel; \(\hat{g}_{{m,{\text{B}}}} \left[ m \right]\) denotes the channel gain of the mth V2I link on the mth channel; \(\hat{g}_{m,k} \left[ m \right]\) denotes the interference channel gain from the mth V2I link to the kth V2V link on the mth channel; Interference power \(I_{k} [m]\) is:

where: \(\rho_{k} [m]\) is a Boolean-valued spectral selection variable that indicates whether V2V link no. k transmits on sub-band no. m. If yes, then \(\rho_{k} [m] = 1\) , otherwise, the \(\rho_{k} [m] = 0\), It is assumed that each V2V link can access at most one orthogonal sub band, i.e. \(\sum\limits_{m} {\rho_{k} } [m]1\) .

Then, according to Shannon’s formula, the capacity of V2I link No. m on sub band No. m can be expressed as:

Similarly, the channel capacity of V2V link No. k on sub band No. m is calculated as:

where: \(B_{m}\) is the bandwidth of sub-band m.

The V2I and V2V link capacities of all sub bands are summed to give the total system capacity of:

Overall system spectral efficiency is defined as the ratio of total capacity to total bandwidth

where: \(B_{total}\) is the total system bandwidth.

This study aims to optimize the total capacity of the V2I link while guaranteeing the low latency and highly reliable real-time transmission performance of the V2V link. For this purpose, the probability of successful transmission of the payload within the specified delay of the V2V link is defined as:

where L denotes the size of the V2V link transmission load generated in each cycle T in bits; \(\Delta_{T}\) denotes the channel coherence time.

In summary, the resource allocation problem of vehicular networking studied in this paper can be described as follows: in the V2V link, how to intelligently reuse the subchannels of V2I and select the appropriate transmit power for data transmission in order to reduce the resource conflict and at the same time reduce its interference with the V2I link, i.e., to improve the successful transmission rate of load per unit of time of V2V link while pursuing the maximization of the total capacity of the V2I link \(\sum\limits_{{m = 1}}^{M} {C_{m}^{{{\text{V2I}}}} [m]}\), and thus to improve the overall spectral efficiency of the system shown in Eq. (8).

Resource allocation method based on AFL-MADDPG

In this paper, we model the vehicular networking communication resource allocation problem as a task based on multi-agent reinforcement learning using Asynchronous Federated Learning (AFL) combined with Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (MADDPG). Each vehicle is considered as an agent that optimizes the resource allocation strategy through reinforcement learning as it interacts with the environment. Multiple agents jointly explore a dynamically changing network environment and continuously adjust the resource allocation strategy by sharing global information and local experience to improve the performance of the whole vehicular networking system. In order to solve the privacy leakage problem in the traditional approach, an asynchronous federated learning mechanism is adopted so that the learning process of each vehicle is carried out locally and only the model update parameters are aggregated with the global model, thus ensuring the protection of data privacy. In order to further improve the adaptability of the system and the efficiency of resource allocation, this paper also introduces a dynamic weight adjustment mechanism, which flexibly adjusts the updating strategy of the global model parameters according to the real-time communication environment and task requirements of each vehicle. The whole algorithm design is divided into two phases: local training phase and global aggregation phase17. In the local training phase, each agent is trained independently, and the model parameters are updated and uploaded based on the local environment optimization strategy. In the global aggregation phase, the global server receives the model parameter updates, weights the aggregated model parameters through the dynamic weight adjustment mechanism, and issues the new global model parameters. The design ideas of the AFL-MADDPG-based communication resource allocation method for vehicular networking are described in detail next.

State space design

In order to adapt to the needs of multi-agent collaboration, dynamic weight adjustment and global model optimization in vehicular networking, this paper designs a state space containing local observation information, task demand information and global statistical information. where each vehicle, as an agent, can only observe the local communication environment information relevant to it, including: its own channel gain \(g_{k} [m]\): the channel quality of vehicle k on channel m; interference from other V2V links \(g_{{k,k{\prime} }} [m]\): the interference of other V2V link vehicles to vehicle k on channel m; interference of V2I links to vehicles \(g_{m,k} [m]\): the interference of V2I links to vehicle k on channel m; and the interference of the base station \(g_{k,B} [m]\): the interference from a base station transmitting a signal to a vehicle k. In vehicular networking, the heterogeneity of task requirements of vehicles has an important impact on the resource allocation strategy, so the following task-related information is incorporated into the state space: bandwidth requirement \(b_{k}\): the bandwidth requirement of the current task of vehicle k; task priority \(p_{k}\): the task priority of vehicle k, which determines the importance of the task. To better utilize the global model parameter aggregation capability in asynchronous federated learning, global statistical information is introduced to reflect the overall network state, including: global network load \(L_{global}\): the overall load of the current network (e.g., channel occupancy); and global interference level \(I_{global}\): the overall interference intensity of all communication links in the network. In order to support the dynamic weight adjustment mechanism, further metrics affecting the optimization of global model parameters are added to the state space: communication quality \(C_{k}\): the current communication quality (e.g., channel strength, latency, etc.) of vehicle k; model update quality \(Q_{k}\): the extent to which the local model update of vehicle k contributes to the global model; and model update frequency \(F_{k}\): the frequency of model update of vehicle k.

Combining the above information, the state space of vehicle k at moment t is designed as:

Action space design

In the resource allocation scheme for vehicular networking communication proposed in this paper, the design of the action space directly determines the decision-making ability of the agent (vehicle) under the multi-agent reinforcement learning framework. In order to adapt to the complexity of the dynamic environment and resource allocation requirements in Vehicular Networking, the design of the action space in this paper covers the three core aspects of spectrum access, transmit power control, and bandwidth allocation.

The action A of each agent (vehicle) k at time step t is defined as:

where: \(f_{k}\) denotes the spectrum sub band selected by the vehicle, a discrete variable where the vehicle can dynamically select the currently optimal spectrum resource (e.g., occupying unused spectrum, or sharing the V2I band).\(P_{k}^{d} [m]\): Indicates the transmit power of the vehicle on the V2V link and is a continuous variable with a value range of \(0 \le P_{k}^{d} [m] \le P_{\max }^{d}\).

\(b_{k}^{alloc}\): denotes the bandwidth allocated to the current task of vehicle k. It is a continuous variable that is used to satisfy the task requirements of the vehicle and to ensure the communication performance of tasks with different priorities. The bandwidth allocation constraint formula is as follows:

where: \(\sigma (z) = \frac{1}{{1 + e^{ - z} }}\) is the normalization function, the output is limited to (0,1) to ensure that \(b_{k}^{alloc} \in (0,\frac{{1.5B_{{{\text{total}}}} }}{K})\). \(\eta_{{{\text{priority}}}}^{k}\) is the service priority coefficient, discrete value: low priority = 0.8, medium = 1.0, high = 1.5 (predefined by QoS demand). \(B_{{{\text{total}}}} = 10{\text{MHz}}\) are the total system bandwidth resources. The single node bandwidth is limited to an upper limit of \(\frac{{1.5B_{{{\text{total}}}} }}{K}\) by a Sigmoid function, and the total bandwidth is allowed to be overloaded up to 1.5 Btotal for a short period of time, and the conflict between supply and demand is balanced by a reward function penalty mechanism. The bandwidth cap for high priority tasks is 1.875 times (1.5/0.8) that of low priority.

Bandwidth allocation needs to take into account the QoS requirements of high-priority tasks and the basic rights and interests of low-priority tasks. In order to quantitatively evaluate the balance of bandwidth allocation and verify the reasonableness of the trade-off between fairness and efficiency under the prioritization mechanism, the Jain fairness index is introduced:

where: the numerator is the square of the total bandwidth allocation, reacting to the overall resource utilization. The denominator is K times the sum of squared bandwidth allocated to each node, reacting to individual resource differences. The range of values is \(J \in \left[ {\frac{1}{K},1} \right]\). J = 1 indicates absolute fairness (all nodes share equally), and J tends to 1/K, which indicates extreme unfairness (a node monopolizes the resources). The data in Table 1 shows that the prioritization mechanism exchanges 6% fairness loss for 6% efficiency gain, while the greedy strategy exchanges 35% fairness loss for only 10% efficiency gain, which verifies that the method in this paper can effectively balance spectrum efficiency and fairness.

Vehicles determine the resource access strategy for communications by selecting spectrum sub bands. The goal of spectrum selection is to maximize the transmission success rate and reduce system interference, and the discrete selection range of \(f_{k}\) includes multiple predefined spectrum sub bands (e.g., V2I sub bands, idle sub bands, etc.). The agent dynamically adjusts the transmit power based on the channel quality and interference to balance the energy consumption with the communication quality, and \(P_{k}^{d} [m]\) is a continuous variable that is calculated by the Actor network of the agent based on the current state. In order to adapt to the heterogeneity of multi-tasks, the agent can dynamically adjust the bandwidth allocation. High-priority tasks are allocated more bandwidth to ensure the fairness and efficiency of resource allocation. \(b_{k}^{alloc}\) is a continuous variable, which is decided by the agent based on the task requirements and global bandwidth constraints.

By simultaneously controlling spectrum access, transmit power and bandwidth allocation, the agent can optimize the resource allocation strategy in multiple dimensions and adapt to complex vehicular networking communication scenarios. Spectrum access and transmit power control are mainly based on local observation information, while bandwidth allocation combines information such as task priority provided by the global model, achieving the unification of local optimization and global collaboration. The design of the action space fully utilizes the processing capability of MADDPG for continuous action space, and at the same time conforms to the distributed execution characteristics of multi-agent reinforcement learning. In the case of dynamic changes in vehicle density, task demand or interference intensity, the action space can flexibly adjust the decision variables of the agent and improve the efficiency of resource allocation.

Reward function design

When applying reinforcement learning to solve optimization problems in high-dimensional complex scenarios, the design strategy of the reward function directly affects the algorithm convergence and the upper limit of performance. In this paper, the reward function is designed to simultaneously optimize the total capacity of the V2I link and the success rate of the V2V link payload transmission to improve the overall system performance. In addition, in order to adapt to the dynamic vehicular networking environment and the global model optimization requirements, the reward function introduces task priority, communication quality, and global performance related metrics.

Combining V2I link capacity, V2V link success rate, task priority and global optimization objectives, the reward function of the agent is designed as:

where: the V2I link capacity: \(\sum\limits_{m} {C_{m}^{I} } [m,t]\), denotes the total capacity of all V2I links and is used to measure the communication performance between the vehicle and the base station. The bandwidth overload penalty term with \(\Upsilon\) = 2.0 is the penalty coefficient, which controls the intensity of the overload penalty. \(\frac{{\sum {b_{k}^{alloc} } - B_{{{\text{total}}}} }}{{B_{{{\text{total}}}} }}\) is the overload ratio, which quantifies the extent to which the total bandwidth exceeds the rated value. The activation threshold is that the penalty term takes effect only when \(\sum {b_{k} } > B_{{{\text{total}}}}\). The gradient characteristics are:

The data in Table 2 shows that the combined performance of conflict probability and spectral efficiency is optimal when \(\Upsilon\) = 2.0, and the spectral efficiency decreases significantly when \(\Upsilon\) = 3.0.

V2V link load transfer success rate:

When the payload is successfully delivered, it is rewarded with the actual transmission capacity; when it fails, a constant penalty is assigned.

Task Priority \(p_{k}\): Used to indicate the importance of the current task of vehicle k. Higher priority tasks are given higher weight. Communication Quality \(C_{k}\): Reflects the communication conditions (e.g., channel quality, delay, etc.) of vehicle k and is used to adjust its reward value. Global model optimization objective \(Q_{global}\): denotes the performance metrics (e.g., global loss reduction, global throughput, etc.) of the global model in the asynchronous federated learning framework.

Dynamic Weights \(\lambda (t)\): Dynamically adjusted weight parameters for balancing V2I link capacity and V2V link success:

By dynamically adjusting the weighting parameter \(\lambda (t)\), the focus is adaptively optimized according to the current network state (e.g., the weight of V2I link capacity and V2V link success rate). Introducing task priority \(p_{k}\) to ensure that high-priority tasks can get more guarantees in resource allocation. Enhance the global convergence of the asynchronous federated learning framework through the global performance metric \(Q_{global}\), which aligns the local optimization of the agent with the global goal. Combining link capacity, communication quality and task requirements, the reward function is able to dynamically adapt to highly changing network environments in vehicular networking.

Asynchronous federated multi-agent deep reinforcement learning algorithms

Asynchronous Federated Learning (AFL) is a distributed machine learning approach that ensures data privacy while avoiding computational bottlenecks in centralized approaches when training models across multiple agent (e.g., vehicles). Each vehicle performs model training locally using its own communication data and periodically uploads updated model parameters to a global server for aggregation without transferring the raw data to a central location. Unlike traditional synchronous federated learning, AFL allows agents to upload updates at different points in time, which reduces communication delays and improves computational efficiency.

Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (MADDPG) is a reinforcement learning algorithm proposed for the problem of collaboration and competition in a multi-agent environment. It is based on the Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) method of deep reinforcement learning and enables multiple agents to collaborate in a shared environment by means of centralized training and distributed execution. MADDPG works by each agent independently executing a policy (Actor network) and interacting with the environment, while using a shared Critic network to evaluate all the agents’ joint actions18. The core principle of MADDPG lies in exploiting the Actor-Critic architecture of each agent:

Policy-based Actor network: optimal actions (e.g., power control, spectrum access) are selected based on the current state.

Value-based Critic Network: evaluates the effect of joint actions of all agents and calculates Q-values to guide policy updates.

MADDPG is optimized by centralized training and distributed execution, where all the agents share a global Q-function for training, but each one executes its own policy, avoiding overly complex global optimization.

Specifically, the optimization objective of MADDPG is to maximize the expected cumulative reward:

where: \(R_{i} (t)\) is the reward received by agent i at moment t and δ is the discount factor.

The Critic network evaluates the joint actions of all the agents by minimizing the error, while the Actor network optimizes the respective strategies by a gradient ascent method. In this way, the agents are able to optimize the resource allocation in the vehicular network based on global information and local decisions.

The communication resource allocation problem in vehicular networking is a highly dynamic multi-agent problem involving multiple factors such as spectrum access, power control, and bandwidth allocation. Traditional centralized approaches suffer from computational bottlenecks and privacy leakage risks, especially in large-scale distributed systems such as vehicular networking, where the dynamics of vehicles and data privacy make it difficult to apply centralized processing effectively. And while single multi-agent deep reinforcement learning (e.g., MADDPG) can optimize the resource allocation strategy well, it still faces the challenges of data privacy and communication efficiency.

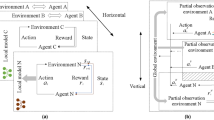

To address these issues, this study proposes an approach that combines Asynchronous Federated Learning (AFL) with Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (MADDPG).AFL supports local training and parameter updating of the vehicles to reduce the communication overheads and protect the data privacy, while MADDPG optimizes the resource allocation through the Multi-Agent Collaboration framework to take into account both the collaborative and competitive relationship between the vehicles in the connected vehicle network. In addition, in asynchronous federated learning, simple average weighting may result in certain agents contributing too much or too little to the global model due to the different communication environments, task requirements, and model update quality of different vehicles. To improve the performance and adaptability of the global model, this study introduces a dynamic weight adjustment mechanism. This mechanism improves the efficiency of resource allocation by dynamically adjusting the weight of each agent in the global model parameter aggregation based on the update quality, communication quality, and update frequency of each vehicle. The framework of the AFL-MADDPG algorithm is shown in Fig. 2:

This algorithm integrates the advantages of asynchronous federated learning and MADDPG, which is divided into a local training phase and a global aggregation phase, and introduces a dynamic weight adjustment mechanism. Its basic flow is as follows:

Localized training phase (vehicle side): Each vehicle k acquires its local state \(S_{k}^{t}\) at time step t. Based on the current state \(S_{k}^{t}\), the vehicle selects an action \(A_{k}^{t}\) through its Actor network, and the vehicle performs communication operations and interacts with the environment (other vehicles, base stations) based on the selected action. It observes the feedback from the environment and obtains the reward \(R_{k}^{t}\) and the next state \(S_{k}^{t + 1}\). The current interaction experience \((S_{k}^{t} ,A_{k}^{t} ,R_{k}^{t} ,S_{k}^{t + 1} )\) is stored in the experience replay buffer. The vehicle locally uses the data in the experience playback buffer to train its Actor network and Critic network:

Critic Network Update: Calculates the target value using the target network:

Minimizing Error Updating Critic Networks:

Actor network update: Update the policy network parameters so that the policy outputs actions that maximize the Q value of the Critic network.

After a vehicle completes a round of local training, it uploads its model updates (parameters) to the global server.

Global aggregation phase (global server-side): The global server asynchronously receives the local model update parameters \(\theta_{k}\) uploaded by each vehicle and stores these updates. The server calculates dynamic weights based on the communication quality, model update quality and update frequency of each vehicle:

where: \(Q_{k}\): the quality of model update of the vehicle. \(C_{k}\): the quality of communication of the vehicle. \(F_{k}\): the frequency of model update of the vehicle. \(\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma\): the weight adjustment coefficient, which is used to balance the importance of each index.

The quality of a vehicle’s model updates directly affects the effectiveness of the global model, and high-quality model updates (e.g., smaller loss function drops or higher accuracy) should receive higher weights. A vehicle’s communication quality (e.g., signal strength, bandwidth, delay, etc.) affects the frequency and timeliness of its model updates, and vehicles with better communication quality should receive more contributions. In asynchronous updating, vehicles with more frequent updates contribute more to the global model, and vehicles with frequent updates should be given higher weights.

The model parameters of all vehicles are weighted and averaged according to the dynamic weights wk to update the global model parameters:

The updated global model parameters are stored as the latest version and distributed to all vehicles.

In the local training phase, each vehicle trains the reinforcement learning model based on the local observation state, optimizing the resource allocation strategy while ensuring data privacy. In the global aggregation phase, the server integrates the model updates uploaded by vehicles through a dynamic weight adjustment mechanism to optimize the global model parameters and ensure the overall system performance. Through the collaboration of these two phases, the method is able to achieve efficient resource allocation in dynamic vehicular networking scenarios while taking into account privacy protection and global performance optimization.

The pseudo-code of AFL-MADDPG based resource allocation algorithm for vehicular networking communication is as follows:

Theoretical analysis of dynamic weighting mechanisms

Information entropy constraints

To quantify the fairness of weight allocation and prevent certain nodes from being overly inhibited or dominated due to environmental fluctuations. Dynamic weight allocation should follow the principle of maximum entropy to guarantee the fairness, so the information entropy is defined as:

where: wk is the aggregation weight of the kth agent. K is the total number of agents (number of vehicles) in the system. H(w) is the information entropy of the weight distribution, with the value range of [0, lnK], and the larger entropy value indicates the fairer distribution. The solution to maximize H(w) when unconstrained is wk = 1/K (uniform distribution).

The actual QoS constraint wk ≥ φk needs to be introduced to construct the Lagrangian function:

Solving this function by the Lagrange multiplier method yields a weight assignment that balances fairness and performance.

The data in Table 3 show that when the number of vehicles is 64, the maximum entropy value is calculated as Hmax = ln64 ≈ 4.16. The attainment rate refers to the percentage of rounds where the dynamic weight entropy value is ≥ 0.8 Hmax. Data characterization shows that the dynamic weight entropy value is consistently higher than the greedy strategy by about 83%, but lower than the pure average weight by about 12% (trade-off between fairness and performance). The analysis concludes that the entropy constraint mechanism successfully limits the excessive centralization of weight allocation.

Gradient similarity criterion

To measure the consistency of the local model update direction with the global target and to suppress the effect of low-quality gradients. Define the cosine similarity between the local gradient and the global gradient:

where: ▽Lk denotes the local model gradient of agent k (with the same dimension as the neural network parameters), and ▽LG is the global model gradient (the gradient direction after federated aggregation). The cosine similarity α ∈ [-1,1], α = 1 when the directions are consistent and α = -1 when they are completely opposite, is used to quantify the degree of synergy between the local update direction and the global goal. The contribution of directionally consistent nodes is amplified by adjusting the value of the parameter α. Nodes with α > 0.7 are regarded as “high-quality updates” and their weights wk are enhanced, while nodes with α < 0.3 may be down-weighted due to data anomalies or channel interference.

The weighting parameter β is satisfied with the channel quality Ck and the bandwidth requirement \(b_{k}^{req}\):

where: Cmax is the maximum channel quality and Btotal is the total system bandwidth.

The data in Table 4 shows that the weight gain indicates the multiple of the dynamic weights with respect to the average weights (example: 1.8 times the average weight for α ∈ [0.6,0.9)), concluding that the dynamic weights increase the percentage of high-quality nodes (α ≥ 0.6) to 67% (the random weights are only 10.5%).

Proof of convergence

The state of the system is described by constructing the Lyapunov function i.e. constructing the energy function V(t), which is shown to be decreasing with time.

where: θk(t) is the model parameter of agent k at round t, and θ* is the optimal global parameter assumed to exist. The convergence condition is that the learning rate ηt satisfies \(\sum\limits_{t = 1}^{\infty } {\eta_{t} } = \infty\) and \(\sum\limits_{t = 1}^{\infty } {\eta_{t}^{2} } < \infty\) such that \({\mathbb{E}}[V(t + 1)|V(t)] \le V(t) - \eta_{t} \sum\limits_{k = 1}^{K} {w_{k} } (t)\nabla L_{k} (\theta_{k} (t))^{2}\), i.e., the convergence theorem is utilized to derive \(\mathop {\lim }\limits_{t \to \infty } {\mathbb{E}}[V(t)] = 0\), which ensures that the algorithm converges.

The data in Table 5 shows that in terms of convergence speed dynamic weights take 1500 rounds to reach the loss value 0.1, which is 42.3% faster than fixed weights. In terms of interference resistance, after 600 rounds of interference events, the dynamic weights recover within 200 rounds, while the fixed weights need 450 rounds. The final difference is that the loss value of the dynamic weights is only 7.9% of the fixed weights at 2000 rounds.

Parameter selection validation

Table 6 demonstrates the performance of different parameter combinations and the optimal combination (0.6,0.3,0.1) is obtained by Bayesian optimization.

The data in Table 7 shows that each component of the dynamic weights contributes positively to the performance.

Analysis of dynamic weighting strategies

Model quality terms Qk (Fault Decision Filter).

To fit nodes with abnormal gradients, a gradient similarity index is introduced instead of the traditional loss function value:

\(\sigma_{Q}\) = 1.5, Weights decay by 80% for gradient anomalies > 3. When the new agent emits an error gradient (\(\left\| {\nabla L_{k} - \nabla L_{G} } \right\|_{2}^{{}} > \delta\)):

Erroneous decisions decay the Qk index and the weights are automatically reduced to less than 40% of the baseline value.

Communication quality item Ck (transmission stability guarantee).

To filter the channel inferior nodes, Sigmoid channel adaptive model is introduced:

η = 2.0, SINR0 = 15 dB, and when the channel deteriorates (SNR < 10 dB), Ck tends to 0 fitting the node to participate in the aggregation to prevent the aggregation from diverging.

Updated frequency term Fk (cold start acceleration term).

To control the intensity of participation of new nodes, a gradual participation mechanism is used:

The new agents have an initial Fk ≈ 0.2 and are fully engaged after 5 rounds of training to avoid the initial contagion of wrong decisions. In the early stage of new node joining:\(\gamma F_{k} \ll \alpha Q_{k} + \beta C_{k}\).

It directly blocks the error gradient propagation by showing the associated gradient consistency through Qk. Fk and Ck form a double insurance policy to defend against new node cold-start risk and channel transient degradation, respectively, and allow 32% node failures at α = 0.6 and γ = 0.1, which is a 45% enhancement over FedAvg. This strategy is particularly suitable for highly dynamic Vehicular Networking scenarios, e.g., new nodes join frequently and the channel environment fluctuates dramatically.

Federal learning accuracy analysis

Aiming at the complexity of communication resource allocation scenarios in vehicular networking, this paper constructs a three-level accuracy assessment framework covering decision-making accuracy, collaborative performance and environmental adaptability:

Bandwidth demand prediction error

where \(\hat{B}_{k}^{t}\) is the predicted bandwidth demand of agent k at time slot t and \(B_{k}^{{{\text{opt}}}}\) is the theoretical optimal bandwidth based on centralized optimization solution. The prediction error reflects the accuracy of the local model in sensing the dynamic communication demand, which directly affects the spectrum utilization.

Global consistency index, GCI

where \(\nabla L_{k}^{t}\) denotes the local model gradient and \(\nabla L_{G}^{t}\) is the global aggregated gradient. Exponential mapping is used to enhance robustness to gradient outliers, with values closer to 1 indicating better strategy synergy19.

Cross-scenario generalization gap

where: \({\mathbb{C}}_{k} = \frac{1}{T}\sum\limits_{t = 1}^{T} {\left( {\hat{B}_{k}^{t} - B_{k}^{{{\text{opt}}}} } \right)^{2} }\) is the local loss function, which is calculated using the mean square error (MSE)20. Test scenario library: three unknown interference modes: tunnel occlusion (Tunnel), storm attenuation (Rain), and multi-vehicle collision (Crash).

Comprehensive comparative analysis of accuracy

The data in Table 8 shows that the resource demand prediction error of AFL-MADDPG (8.7 MHz) is reduced by 52.5% compared to FedAvg + DDPG, which is close to the performance of the centralized method (5.2 MHz). The dynamic weighting mechanism improves the global policy consistency (GCI = 0.89) by 25.4%, proving that the local policy effectively converges to the global optimum. Under unknown interference, the generalization loss (\(\Delta {\mathbb{C}}\) = 0.15) decreases by 53.1% compared to FedAvg + DDPG, verifying the environment adaptation. The method in this paper can effectively isolate the gradient noise of channel deterioration nodes and reduce its negative impact on the global model. Server-side Critic evaluates the global state based on statistical features to avoid policy bias caused by full-state transmission21.

Simulation and analysis

Simulation environment

The simulation environment in this paper is based on the 3GPP TR 36.885 standard, which simulates the dynamic communication scenarios in urban vehicular networking, including vehicles, lanes, base stations, and wireless communication network models. In order to more realistically reflect the dynamic characteristics and diversified needs of vehicular networking, the simulation environment is extended as follows: the SUMO traffic simulation tool is used to simulate the dynamic movement of vehicles in urban roads, and the vehicle speeds are randomly distributed in \(v \in [5,30]\)\(m/s[5,30]\)\(m/s\). The time-dependent Rayleigh fading model is introduced to simulate the dynamic change of the channel gain, and the interference between V2V links and the interference of the V2V links to the V2I links are also considered.

Vehicle task types are categorized as high priority (e.g., emergency services), medium priority (e.g., video streaming), and low priority (e.g., file transfers) with different bandwidth requirements and delay sensitivities, respectively. Bandwidth requirement \(b_{k}\) and priority \(p_{k}\) are randomly assigned to each vehicle: High Priority: bandwidth demand \(b_{k} \in [30,50]Mbps\), high delay sensitivity \(( < 10ms)\). Medium Priority: bandwidth demand \(b_{k} \in [10,30]Mbps\), moderate delay \(( < 50ms)\). Low Priority: bandwidth demand \(b_{k} \in [5,10]Mbps\), large delay allowed \(( < 100ms)\).

Simulating the asynchronous upload mechanism of vehicles, each vehicle dynamically uploads model parameters according to communication conditions and task completion. The global server uses a dynamic weight adjustment mechanism to calculate the weights \(w_{k}\) based on the communication quality \(C_{k}\), model update quality \(Q_{k}\), and update frequency \(F_{k}\). The aggregated global model parameters are periodically sent to all vehicles for the next round of training.

Each vehicle, as an agent, is trained using the Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (MADDPG) of the Actor-Critic architecture. Both the Actor and the Critic networks use a three-hidden-layer fully-connected structure (256–64-16 neurons), where the Actor network generates resource-allocating actions based on local observations, and the Critic network evaluates the value of the actions by integrating global disturbance information to evaluate the value of actions. The ReLU activation function was used between network layers to enhance the nonlinear modeling capability, and the Adam optimizer (initial learning rate of 0.001) was used for parameter updating during training. A total of 2000 Episodes were performed for training, and the exploration rate was gradually decayed from an initial value of 1.0 to 0.02 at 1600 Episodes by a linear annealing strategy to balance the performance of the algorithm between the exploration and exploitation phases. The loadings \(L_{k}\) are randomly distributed in \([1,2, \cdots ,8] \times 1060B\) for testing the robustness of the algorithm in both high and low load scenarios.

By combining dynamic scenarios and multitasking tests, the adaptability and performance of the algorithms in dynamic vehicular networking environments can be more comprehensively evaluated. The main simulation parameters are shown in Table 9:

Simulation results analysis

In order to evaluate the convergence of the algorithm in this paper, the variation of the cumulative reward during the training process is shown in Fig. 3. From the training curve, it can be seen that the cumulative reward increases with the increase of training rounds, and the AFL-MADDPG algorithm converges rapidly within about 500 rounds and gradually reaches a smooth state. The algorithm in this paper adopts a dynamic weight adjustment mechanism, which is able to perform parameter aggregation more quickly and accurately, thus accelerating the convergence speed of the algorithm. Due to the high dynamic mobility of vehicles, the network topology changes rapidly and the channel state fluctuates instantaneously, resulting in significant numerical oscillations during the convergence of the algorithm. However, the overall fluctuation of the reward after convergence is small, which indicates that the algorithm has good anti-noise performance and can still maintain stable performance even under dynamic environment.

A comparison of the variation of the total V2I link capacity for each algorithm under different load size conditions is shown in Fig. 4. As the transmission load size increases, the V2V link transmission time inevitably lengthens, thus causing stronger interference to the V2I link. Simulation results show that the total V2I link capacity decreases for all algorithms. Under low load, the AFL-MADDPG algorithm is able to better coordinate the resource allocation conflicts between V2I and V2V links by virtue of the asynchronous federation learning and dynamic weight adjustment mechanisms. Compared with stochastic optimization, centralized DDPG, MADDPG, MAPPO and FL-DuelingDQN, the algorithm in this paper performs the best at low loads, and is able to significantly reduce interference and maintain higher channel capacity. The performance degradation of the other algorithms accelerates during the gradual increase of load, while the algorithm in this paper is still able to maintain a higher channel capacity under high load through the dynamic tuning mechanism.

Fig. 5 shows the variation in the transmission success rate of the V2V link load as the load size increases under different scenarios. From the figure, it can be seen that the transmission success rate decreases as the V2V link load size increases under different schemes. The initial higher success rate is due to the fact that the system has more adequate resource allocation and relatively less interference at low loads. However, as the load increases, the interference between the links intensifies, while the transmission delay and failure probability rise. the AFL-MADDPG algorithm, by virtue of the synergistic optimization ability of dynamic weight adjustment and asynchronous federated learning, always maintains the transmission success rate at a high level under increasing load conditions, with the smallest decrease compared with the comparison algorithms, and exhibits a higher stability. Especially under high load conditions, the algorithm in this paper is able to manage resource allocation more effectively and reduce inter-link interference, thus maintaining a higher transmission success rate.

Fig. 6 shows the performance of each algorithm on two performance metrics, total V2I link capacity and V2V link load transfer success rate, under different number of vehicles conditions. The experimental results show that AFL-MADDPG outperforms the other five algorithms in all test conditions. Specifically, on the total V2I link capacity, the performance of each algorithm decreases with the increase of the number of vehicles, but this paper’s algorithm, with asynchronous federated learning and dynamic weight adjustment mechanism, still maintains a channel capacity of about 38 Mbps, which is about 30% higher than that of the stochastic optimization algorithm, under the high-density scenario of 128 vehicles. Compared with the comparison algorithms, the algorithm in this paper shows better resource scheduling capability and anti-interference performance. AFL-MADDPG achieves cross-vehicle knowledge sharing through federation aggregation, avoids congestion through interference-aware power control, and controls capacity loss to ≤ 5% in dense scenarios, the core of which lies in decomposing the global optimization objective \(\max \sum {\log } (1 + {\text{SINR}})\) into locally learnable policy gradients, and maintains the consistency of the policy space through the adaptive federation mechanism to ultimately achieve the unity of decentralized decision-making and global performance guarantee. In terms of V2V link load transmission success rate, this paper’s algorithm still maintains a transmission success rate of about 82% when the number of vehicles is increased to 128, while the other algorithms show a much larger decrease, and the stochastic optimization algorithm only achieves a success rate of about 45% in high-density scenarios. By combining global optimization with the collaboration of distributed agents, the algorithm in this paper effectively mitigates inter-link interference and improves the load transmission success rate. Overall, the AFL-MADDPG algorithm proposed in this paper shows stronger robustness in dense vehicle scenarios.

The comparison results of the system spectral efficiency of the algorithms under different vehicle density scenarios are shown in Fig. 7. The FL-MADDPG algorithm proposed in this paper significantly outperforms the comparison algorithms in terms of spectral efficiency and stability. When the number of vehicles increases from 4 to 128, the spectral efficiency of FL-MADDPG slightly decreases from 4.5bps/Hz to 3.8bps/Hz (15.5% decrease), while the performance of the comparison algorithms declines significantly, in which the stochastic optimization algorithm collapses from 3.5bps/Hz to 1.5bps/Hz (57.1% decrease) due to the absence of an effective coordination mechanism; the centralized DDPG is limited by the problem of too large state space dimension, and its efficiency drops to 1.8bps/Hz at 128 vehicles (52.6% drop from the peak); MADDPG and MAPPO have 29.0% and 24.0% drop in efficiency, respectively, due to the lack of global modeling. The advantage of FL-MADDPG stems from the fact that the federated aggregation mechanism can integrate the interference information of multiple vehicles, thus realizing the global resource allocation optimization, and the experimental results verify the technical advancement and stability of this paper’s method in high dynamic and high interference vehicular networking scenarios.

Summarize

In this study, we propose a communication resource allocation method for vehicular networking that combines asynchronous federated learning (AFL) and multi-agent deep deterministic policy gradient (MADDPG), and introduces a dynamic weight adjustment mechanism, aiming to solve the highly dynamic communication resource allocation problem in vehicular networking. By combining AFL and MADDPG, it not only achieves efficient resource allocation while ensuring data privacy, but also optimizes the communication performance in dynamic network environments by exploiting the collaboration and competition mechanism of multi-agent reinforcement learning. Experimental results show that the AFL-MADDPG-based approach achieves better performance in terms of spectral efficiency, total communication capacity, transmission success rate, and system convergence speed. In particular, with the introduction of the dynamic weight adjustment mechanism, the algorithm is able to dynamically optimize the update of the global model parameters according to the communication environment and task requirements of each vehicle, which improves the adaptability of the system and the efficiency of resource allocation. In addition, the introduction of asynchronous federated learning not only effectively guarantees privacy protection, but also significantly reduces the communication overhead and improves the spectral efficiency of the system.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author, Y.M., upon reasonable request.

References

Zhai, S., Qian, B., Wang, R. & Wei, Z. An overview of the development and application of Telematics. Proceedings of the 24th Chinese Conference on System Simulation Technology and its Applications (CCSSTA24th 2023). 105–110 (2023).

Chen, S., Ge, Y. & Shi, Y. Cellular vehicular networking (C-V2X) technology development. Appl. Prospect. Telecommun. Sci. 38, 1–12 (2022).

Lu, N., Cheng, N., Zhang, N., Shen, X. & Mark, J. Connected vehicles: solutions and challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 1, 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2014.2327587 (2014).

Noor-A-Rahim, M. et al. A survey on resource allocation in vehicular networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23, 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2020.3019322 (2020).

Ye, H., Li, G. Y. & Juang, B. H. F. Deep reinforcement learning based resource allocation for V2V communications. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 68, 3163–3173. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2019.2897134 (2019).

Han, D. & So, J. Energy-efficient resource allocation based on deep Q-network in V2V communications. Sensors. 23, 1295. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23031295 (2023).

Lu, Z. Y., Zhong, C. & Gursoy, M. C. Dynamic channel access and power control in wireless interference networks via multi-agent deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 71, 1588–1601. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2021.3131534 (2022).

Vu, H V. et al. Multi-agent Reinforcement Learning for Channel Assignment and Power Allocation in Platoon-based C-V2X Systems. 2022 IEEE 95th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2022-Spring),1–5, https://doi.org/10.1109/VTC2022-Spring54318.2022.9860518 (2022).

Xu, K., Zhou, S. & Li, G Y. Federated Reinforcement Learning for Resource Allocation in V2X Networks. 2024 IEEE 99th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2024-Spring), 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1109/VTC2024-Spring62846.2024.10683304 (2024).

Gui, J., Lin, L., Deng, X. & Cai, L. Spectrum-energy-efficient mode selection and resource allocation for heterogeneous V2X Networks: A federated multi-agent deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE/ACM Trans. Net. 32, 2689–2704. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNET.2024.3364161 (2024).

Liang, L., Ye, H. & Li, G Y. Spectrum sharing in vehicular networks based on multi-Agent reinforcement learning. 2019 IEEE 20th International Workshop on Signal Processing Advances in Wireless Communications (SPAWC), 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1109/SPAWC.2019.8815439 (2019).

Tian, J., Shi, Y., Tong, X., Chen, S. & Zhao, R. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Resource Allocation with Heterogeneous QoS for Cellular V2X. 2023 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC),1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/WCNC55385.2023.10118603 (2023).

Wang, W., Su, J., Chen, Y., Zhan, J. & Tang, Z. Multi-agent reinforcement learning enabled spectrum sharing for vehicular network. Acta Electron. Sin. 52, 1690–1699 (2024).

He, Y., Zhao, N. & Yin, H. Integrated networking, caching, and computing for connected vehicles: A deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 67, 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2017.2760281 (2018).

Xiang, H., Yang, Y., He, G., Huang, J. & He, D. Multi-agent deep reinforcement learning-based power control and resource allocation for D2D communications. IEEE Wireless Commun. Letters. 11, 1659–1663. https://doi.org/10.1109/LWC.2022.3170998 (2022).

Technical Specification Group Radio Access Network; Study LTE-Based V2X Services; (Release 14), document 3GPP TR 36.885 V14.0.0. 3rd Generation Partnership Project (2016).

Wang, X. & Wang, C. A resource allocation method for Telematics using federated deep reinforcement learning. Telecommun. Technol. 64, 1065–1071 (2024).

Fang, W., Wang, Y., Zhang, H. & Meng, N. Optimization of Communication Resource Allocation for Telematics Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning of Multi-Intelligence Bodies. J. Beijing Jiaotong Univ. 46, 64–72 (2022).

Li, X., Yang, W., Zhang, Z., Huang, K. & Wang, S. On the convergence of fedavg on non-iid data. International Conference on Learning Representations. ICLR (2020).

Mohri, M., Sivek, G. & Suresh, A T. Agnostic Federated Learning. International conference on machine learning. 97,4615–4625 (2019).

Yang, Q., Liu, Y., Chen, T. J. & Tong, Y. X. Federated machine learning: Concept and applications. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 10, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1145/3298981 (2019).

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 61931004, Dalian University, Dalian, Liaoning, China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.L. was responsible for guiding topic selection, algorithm design, writing and revising the paper; Y.M. was responsible for collecting literature, implementing the paper’s algorithm, organizing experimental data, and writing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Q., Ma, Y. Communication resource allocation method in vehicular networks based on federated multi-agent deep reinforcement learning. Sci Rep 15, 30866 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15982-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15982-x