Abstract

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after traumatic events is prevalent and can lead to negative consequences. While social media use has been associated with PTSD, little is known about the specific association of online hate speech on social media networks and PTSD, and whether such association is stronger among those with difficulties in emotion regulation, who may have a harder time coping with hate speech. In a general population sample of Jewish adults (aged 18–70) in Israel (N = 3,998), assessed about two months after the wide-scale terror attacks of October 7, 2023, regression analysis was used to explore the association of online hate speech and self-reported PTSD symptomology. Difficulties in emotion regulation (DER) was explored as a moderator of the association. Greater frequency of hate speech was significantly associated with increased PTSD symptomology, adjusting for problematic use of technology, terror and war exposure, and prior mental health issues. The association differed significantly by DER; as difficulties increased, the association was stronger. Public health campaigns could educate about the potential harms of hate speech to help individuals make informed choices, and clinicians could discuss possible hate speech effects with patients more vulnerable to PTSD, for example, those with emotion dysregulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a common result of trauma exposure, is prevalent worldwide, and can be severely disabling1. Thus, it is important to understand factors that are associated with increased vulnerability to PTSD. One such factor may be social media use, as many studies have explored the role of social media use in psychological distress, including PTSD2. Results suggest that specific aspects of social media use, such as problematic use or addiction and exposure to graphic depictions of traumatic events through social media are associated with psychological distress or PTSD3,4. Another aspect of social media that may be associated with psychological distress is online hate speech5. Hate speech is often defined as hostile communication against an individual or group based on a group characteristic, such as nationality, ethnicity, or religion6,7. Online forums can rapidly amplify hate speech by widening the range of exposure and removing inhibitions, as well as provide new forms such as trolling (persistent, deliberate harassment) and degrading memes8. Much has been written about the increasingly high prevalence of exposure to hate speech online worldwide9 and its potential to cause a wide range of negative consequences6,7,8 similar to the harms associated with other forms of hate speech, including psychological effects such as PTSD10,11.

In general population samples, only a few studies directly assessed the association of exposure to online hate speech and psychological distress, with most studies carried out in adolescents or young adults8. For example, in adolescents, experiencing online hate speech was associated with more depression symptoms; this effect was mitigated by resilience factors12. In a study of college students, online hate speech was positively associated with students’ stress13. Yet, large-scale studies in general adult population samples assessing the contribution of online hate speech to psychological distress, specifically PTSD symptomology, are lacking.

PTSD has also been shown to be associated with difficulties in emotion regulation14,15. Emotion regulation refers to the ability to influence emotion generation and experience16,17. The extended process model of emotion regulation posits that emotions can be affected by avoiding or modifying situations that generate emotions, distracting attention from the situation or emotions, cognitive reappraisal of the situation’s emotional meaning, or modifying the emotional response. Within this model, there is a 4-step framework for emotion regulation: (1) Identification of the need for regulation; (2) Selection of a regulatory strategy; (3) Implementation of the selected strategy; and (4) Monitoring the implementation, to determine efficacy and what should be changed. Difficulties in emotion regulation (DER) can occur in the processes delineated above, resulting in the failure to regulate effectively or using inappropriate regulatory strategies18. Lack of regulation can lead to emotional problems, either in type, intensity, frequency, or duration. Such difficulties may influence an individual’s reaction to stress and ability to deal with trauma, increasing risk for PTSD18. For example, PTSD symptoms, such as intense emotional distress, hyperarousal/persistent emotional state, or inability to express positive emotions may indicate emotional problems (overall dysregulation); intrusive distressing memories and flashbacks may limit ability to avoid or modify the situation or distract from emotion generating cues; physiological reactions may reflect problems with response modulation; and engagement in reckless behaviors may indicate selection and implementation of maladaptive regulatory strategies.

One study showed that adolescents’ ability to cope with online hate was related to emotional well-being19 suggesting that those with DER may cope less well with hate speech. Hate speech may evoke stronger, unregulated emotions, as well as more intense re-experiencing of previously unprocessed emotions, among those individuals, further increasing risk for PTSD. Thus, online hate speech may show a greater association with PTSD among those with higher levels of DER. Additionally, emotion dysregulation was found to predict problematic social media use at a daily level20 which could be associated with increased exposure to online hate speech, and then further contribute to psychological distress.

Exposure to traumatic events is a pre-condition for PTSD, with PTSD severity related to the type and extent of the trauma. On October 7, 2023, Israel suffered one of the most severe mass casualty terror attacks in modern history, perpetrated by Hamas-led militants, with greater than 1200 fatalities, 9000 injured and 250 hostages taken21,22. Additionally, Hamas engaged in digital terror, using digital technology to quickly spread graphic images and videos to millions of people, causing widespread horror and fear4,23. This exposure, which was mainly via social media, could also increase exposure to online hate speech. The terror attacks led to an ongoing war, with life-threatening situations and continuing traumatic exposures, both in real and digital life. As expected, these terror and war exposures were associated with increased post-traumatic stress symptomology and PTSD24,25,26 and emotion regulation was shown to be important for dealing with the psychological effects of the war24. Thus, the Israel-Hamas war provides an opportunity to explore the unique effects of online hate speech and DER on PTSD symptoms, in the context of additional factors that may be involved in these associations, i.e., war exposures, problematic use of technology (internet, smartphone, social media) and prior mental health issues4,27.

Therefore, in data from a cross-sectional, quasi-representative general population sample of Jewish adults in Israel, collected about two months after October 7th, three objectives were addressed. (1) Association of online hate speech and PTSD symptomology: we predict that increased exposure to online hate speech will be associated with increased PTSD symptom severity, even after accounting for other potentially related predictors (sociodemographic variables; exposure to the October 7th terror attacks; ongoing war exposures; problematic use of technology; and prior self-perceived mental health problems). (2) Moderation by difficulties in emotion regulation: we predict that the association between online hate speech and PTSD symptom severity will be stronger for those with greater difficulties in emotion regulation. (3) Other risk factors for PTSD: we predict that the predictors (listed above) will also be associated with PTSD severity. Providing further understanding of the risk factors for PTSD can inform prevention and intervention strategies on the population and individual level.

Methods

Sample and procedures

Data collection was described previously28 and is summarized here. Cross-sectional data were collected from a general population sample of adults in Israel, November 27-December 12, 2023, as the baseline timepoint for a planned longitudinal study of the effects of October 7th and the subsequent war on mental health issues, using methodology similar to a previous epidemiological study in Israel29. A quasi-representative sample of the adult (ages 18–70; mean = 41.4 years, SD = 14.8), Hebrew-speaking, Jewish population was constructed, by drawing a convenience sample from an online survey panel30 utilizing quotas based on Israel Census Bureau data for 202331 for age, gender, geographic area, and religiosity. Respondents were aged 18–70, since older people are less likely to participate in online surveys, and Jewish and Hebrew speaking, as different cultural groups require substantial adaptations. Invitations to participate were sent to all respondents surveyed previously29 and to a random sample of other panel members. Invitation acceptances were screened against the quotas until the target numbers were met. Identifying information was not available to the researchers and the survey company did not have access to survey responses, maintaining confidentiality. Survey methodology was consistent with the ICC/ESOMAR International Code on Market and Social Research32. Electronic informed consent was provided by all participants. The Institutional Review Board of the Reichman University approved the study. All experiments were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The online survey assessed sociodemographics, substance use and other addictive behaviors, psychopathology, and risk and protective factors, utilizing valid, widely used instruments. Confidential online surveys may be better for collecting sensitive information such as addictions33. Participants received online gift cards worth 20 ILS upon finishing the survey. Quality was assured by: inviting registered individuals; excluding respondents who failed any of 4 attention checks; and removing incomplete surveys. Of those invited (17,267), 6,765 agreed, 1,318 were excluded because of quotas, and 1,445 did not finish the survey (638 failed attention checks, 807 dropped out), for a sample of 4,002.

Measures (Table 1)

Outcome: Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptomology

The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist – DSM-5 version (PCL-5)34,35 was used to assess past month PTSD symptoms, due to the October 7th attacks and the ongoing war. The PCL-5 includes 20 items assessing how much respondent was bothered by PTSD-related problems (e.g., “Unwanted, recurring, and disturbing memories of the difficult experience”; “Strong negative emotions such as fear, terror, anger, guilt, and shame”), with 5 response options: (0) not at all; (1) a little bit (2) moderately; (3) quite a bit; (4) extremely. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.96, and items were summed for an overall score (range: 0–80).

Main predictor: online hate speech

Respondents were asked how often they experienced hate speech on social media networks since the start of the war, with a Likert scale of the following responses: 1 (not at all); (2) once/twice; (3) a few times; (4) each week; 5) few times a week; 6) (almost) every day; (7) (several times a day).

Moderator: difficulties in emotion regulation

The 18-item Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS-1836) was used. Respondents rated how often statements about emotion regulation were true about them (e.g., “I have no idea how I feel”; “When I am upset, it is hard for me to concentrate on other things”), with 5 response options: (1) almost never; (2) sometimes; (3) about half the time; (4) most of the time; (5) almost always. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91, and an overall score was calculated by summing all 18 items (range: 18–90), with higher scores indicating greater emotion dysregulation.

Other predictors

Problematic technological behaviors

Problematic social media use was assessed using the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS)37,38 with 6 items assessing frequency of social media behaviors in the past 12 months (e.g., “You felt the urge to use social media more and more”;"You used social media to forget about your problems”), from (1) very rarely to (5) very often. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91, and items were summed for an overall score (range: 6–30). Problematic smartphone use was assessed using the Smartphone Addiction Scale, short version (SAS-SV)39,40 with 10 items assessing degree of agreement with statements about current smartphone use (e.g., “I feel impatient and anxious when I don’t have my smartphone with me”; “I cannot bear the thought of not having a smartphone at my disposal”), with 6 response options, from very strongly disagree (1) to very strongly agree (6). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91, and items were summed for an overall score (range: 10–60). Problematic internet use was assessed using the Internet Addiction Test (IAT)41,42 with 20 items assessing frequency of internet use behaviors in the past month (e.g., “How often do you find yourself online more than you intended?“;"How often do you block troubling thoughts about your life with calming thoughts about the internet?“), from (0) not relevant to (5) always. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95, and items were summed for an overall score (range: 0-100).

Exposure to terror and war

Four items asked about exposure to the October 7th attacks: (1) being in an attacked area in the South; (2) exposure during duty in the security forces or emergency services; (3) being somewhere with widespread missile attacks; (4) severe injury or death due to the events. Three response options assessed whom exposure happened to: (1) respondent; (2) a close family member; or (3) someone respondent knew; it was possible to choose more than one response. Three scores were calculated (for respondent, close family, and friend) as a sum of the four items (1 = happened; 0 = didn’t happen, range 0–4), which were summed to a total October 7th exposure score (range 0–12).

Two items assessed direct war exposure, since October 7th, based on frequency of: (1) alarms, due to rocket or missile attacks, terrorist infiltration, or hostile aircraft infiltration; and (2) hearing explosions. Two items assessed indirect war exposure, based on frequency of (1) reading and (2) viewing uncensored materials about the October 7th attacks or the ongoing war. Uncensored materials would most likely have been accessed via online platforms, as most offline sources would be subject to censorship. For each war exposure measure, responses were on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (several times a day), and both items were summed to form a composite measure (range, 2–14).

Self-perceived mental health problems prior to October 7th

Respondents were asked if before October 7th, they had mental health problems in three categories. First, they were asked about (1) depression; (2) anxiety; (3) PTSD; and (4) other mood disorders; a positive response to any one was considered “yes” for mood, anxiety, or stress problems. Second, they were asked about problems with use of (1) alcohol; (2) cannabis; (3) prescription sedatives; (4) stimulants; (5) opioid painkillers; and (6) other illicit drugs; a positive response to any one was considered “yes” for substance use problems. Third, they were asked about problems with engagement in (1) gambling; (2) electronic gaming; (3) pornography; (4) compulsive sexual behaviors; (5) smartphone; (6) social media; (7) and internet; a positive response to any one was considered “yes” for addictive behaviors problems.

Sociodemographics included age, gender, religiosity, and area of residence.

Statistical analysis

Four respondents answered “other” for gender and were excluded from the analysis, for an analytical sample of 3,998. Sample descriptives were calculated. Cronbach’s alpha was estimated for score variables.

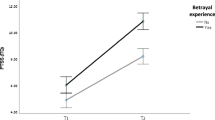

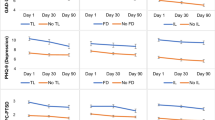

Linear regression analysis was carried out using the process package in R43. In primary analyses, the association of hate speech with PTSD symptomology (PCL-5 score) was estimated in a series of models, each adding more adjustments (Table 2), to distill the unique contribution of hate speech, after accounting for potential confounders or mediators. Since the goal in each model was to test significance of one predictor (hate speech), p < 0.05 was considered significant, as indicated by 95% confidence interval (CI) not overlapping with 0. To test if the association of hate speech and PCL-5 score was moderated by difficulties in emotion regulation, an interaction term for hate speech by DERS-18 score was added to the regression models, and the magnitude of the association was estimated for three levels of DERS-18 score: low (16th percentile), middle (50th percentile), and high (84th percentile) (Fig. 1a). As the goal in each model was to test significance of one predictor (interaction of hate speech and DER), p < 0.05 was considered significant, as indicated by 95% CI not overlapping with 0. In secondary analysis, other potential predictors of PTSD included in the final main effects model (besides online hate speech) were evaluated for association: Sociodemographic variables, DERS-18 score, problematic technology behaviors (BSMAS, SAS-SV, and IAT scores), exposure to October 7th attacks, war exposure, and self-perceived mental health problems prior to October 7th (Fig. 1b). Since that model included 15 predictors, the Bonferroni correction was applied, with significance at p < 0.05/15 = 0.0033. Count predictors (except age) were standardized before regression analysis. Multicollinearity was assessed by calculating the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for each predictor, using the vif function from the car package in R44; all VIF were < 3, indicating no concern about multicollinearity. To ensure that results were robust to possible violations of regression assumptions, permutation tests for the regression parameters were done for the final main effects and moderation models, using the lmperm function from the permuco package in R45.

Results

Sample descriptives (Table 1)

Of the sample, about half were women, lived in the Tel Aviv/Central region; and about 40% were aged 18–34, secular, finished high school. High PTSD symptom scores, indicating possible PTSD, was found in 25% of the sample, and 39% reported at least weekly exposure to hate speech on social media networks. Of the sample, prevalence of problematic technology use was 8% for social media and internet and 28% for smartphone; 39% reported at least one self-exposure to the October 7th attacks; and at least weekly war exposure was 62% for direct and 46% for indirect. Self-report of perceived mental health problems was 51% for mood, anxiety, or stress disorders; 20% for substances; and 53% for addictive behaviors.

Objective 1: association of hate speech and PTSD

Higher frequency of hate speech on social media networks was associated with increased average PTSD scores (Table 2). To distill out the unique association of hate speech with PTSD symptomology, after accounting for other variables (e.g., confounders or potential mediators), additional predictors were added sequentially. The magnitude of association was reduced but remained significant (p < 0.0001). For example, the unadjusted regression coefficient was 6.8, and decreased to 5.3 after including DERS-18 in the model; 3.5 after including problematic technology use; and 2.3 after including terror/war exposure. In the final model, a one standard deviation increase in hate speech exposure was associated with a 2.2 (p < 0.0001) point increase in average PTSD score, adjusting for sociodemographic variables, difficulties in emotional regulation, terror and war exposures, problematic technological behaviors, and perceived mental health problems prior to October 7th.

Objective 2: moderation by difficulties in emotion regulation

In all models, the association of hate speech and PTSD score differed by difficulties in emotion regulation (Table 2; p-values for interaction term all < 0.05); as DERS-18 increased, the magnitude of association increased (Table 3).

Objective 3: association of other factors with PTSD

Additionally, most of the predictors were associated with increased PTSD scores (Table 4). In the fully adjusted main effects model, women, on average, showed higher PTSD scores than men (6.5, p < 0.0001). Increased PTSD scores were associated with a one standard deviation increase in problematic technological behaviors scores (social media [2.4; p < 0.0001]; smartphone [1.8, p < 0.0001]; and internet [1.1, p = 0.0007]), terror/war exposure (October 7th attacks [1.6, p < 0.0001]; direct exposure [2.0, p < 0.0001]; and indirect exposure [1.3, p < 0.0001]), and difficulties in emotion regulation (4.0, p < 0.0001). Higher average PTSD scores were also observed among those with self-reported perceived problems with mood, anxiety, or stress (4.0, p < 0.0001) and substances (3.5, p < 0.0001). The permutation tests showed that all significant effects remained, confirming that results were robust to assumption violations.

Discussion

Data from a large, quasi-representative cross-sectional sample of adult Jews in Israel provide a unique opportunity to examine the role of hate speech over social media networks in PTSD symptomology, in the context of a mass casualty terror attack and ongoing war. Higher frequency of exposure to online hate speech was associated with increased PTSD symptomology, independent of other key correlates of PTSD: gender; difficulties in emotional regulation; problematic technological behaviors; terror and war exposure; and pre-existing problems with mental health. Additionally, those with higher levels of difficulties in emotional regulation showed stronger association between online hate speech and PTSD symptoms.

As predicted in Objective 1, higher frequency of online hate speech exposure was associated with greater PTSD severity. While no previous study assessed the association of online hate speech specifically with PTSD, these results provide additional evidence for the role of hate speech in psychological distress, similar to previous studies8,9,11,12,13. Online hate speech can exacerbate effects of traumatic events, or may itself be considered a form of trauma10. While studies have considered the digital spread of graphic media as a form of terror4,23 in this study, online hate speech showed an effect above and beyond exposure to uncensored media (likely to have occurred online). These results suggest that hate speech could also be considered an important aspect of digital terror.

As predicted in Objective 2, the association of hate speech and PTSD was stronger for those with difficulties in emotion regulation. Difficulties in emotion regulation was associated with PTSD symptomology, as found in many previous studies14,15,18 with emotion dysregulation related to the development, maintenance, and severity of PTSD, possibly because of difficulties in dealing with the strong emotions raised by the trauma and distress14,46. The emotional effects of hate speech could be exacerbated among those with difficulties in regulation, increasing risk of PTSD symptoms, similar to previous studies showing similar effects among those exposed to other forms of trauma or stress14. Furthermore, those with maladaptive emotion regulation strategies, who use addictive behaviors such as problematic social media to cope with stress and manage negative emotions47,48 may be at increased risk for PTSD. The social media use could increase distress, through exposure to graphic media and online hate speech, which could be related to increased risk for PTSD.

While it makes sense to consider that exposure to hate speech, especially for someone with a harder time regulating emotions, could bring up bad feelings and memories, and be associated with greater PTSD severity, this cross-sectional study cannot determine directionality. Alternatively, those with PTSD, especially with emotion dysregulation, might be at increased risk for hate speech exposure due to increased risk for problematic social media use14,16,42, might be more likely to consider online material as hateful, or might react more negatively to this kind of material. Furthermore, there may also be positive ways to cope with stress via social media, which can provide connection and support. Lastly, results showing that the magnitude of association between hate speech and PTSD severity got weaker with inclusion of additional predictors, e.g., problematic technology use, and terror/war exposure, suggest that these could be mediating the effect of hate speech. Longitudinal studies should further explore the potentially complex interactions between social media use, online hate speech, trauma exposure, emotion regulation, and PTSD.

In line with Objective 3, other factors were uniquely associated with PTSD as well. Similar to many previous studies worldwide and in Israel, for example, women showed higher PTSD scores49,50; problematic technology use and exposure to uncensored media (mostly via social media) were also associated with more severe PTSD symptomology3,4,27,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58. Problematic technology use may lead to re-exposure to the traumatic event and increase exposure to ongoing stress, worsening mental health28,59. Further studies should identify how these and additional aspects of technology use work together with online hate speech exposure to negatively impact well-being, so individuals can make informed choices about their behaviors. As expected, terror and war exposures were associated with increased PTSD symptomology. The association of indirect exposure (uncensored war media) suggests re-assessment of the criterion that excludes exposure through media as a traumatic event which may be able to lead to PTSD, similar to previous studies58,60. Furthermore, ongoing stressors should be accounted for in PTSD risk, as suggested previously61,62. Last, previous problems with mental health issues, such as mood and stress-related disorders, are known to increase risk for current PTSD4,27and PTSD and substance use problems are known to be associated63,64. Using substances to cope with trauma and stress may lead to negative, self-reinforcing spirals, culminating in increased mental health disorders28,65,66,67. Future studies should take these and other factors into account, using machine learning to more fully understand the complex relationships underlying vulnerability to PTSD.

Several possible implications of this study are discussed. Due to its ubiquitous and potentially damaging nature, online hate speech may be an important societal and public health issue5,6 akin to more general hate crimes and cyberbullying. Thus, hate speech may benefit from population wide interventions11 similar to overall problematic internet or social media use68.

Public health approaches take into account three aspects of risk: the agent (online hate speech), the environment (society), and the host (individual)68. Many studies have used machine learning to identify online hate speech5 and other studies explored the dynamics of perpetration, i.e., who, when, and why6, both of which are important for development of artificial intelligence and education methods to monitor and prevent hate speech11. On the societal level, due to the global reach of digital information, public health policies could be similar to the World Health Organization’s global monitoring system on alcohol, which recommends a standardized list of evidence-based policies worldwide11. Policies could be developed for regulating hate speech exposure, especially to protect vulnerable populations (children, minority groups); providing warnings; and education about possible negative effects of such exposure and how to reduce the impact23. On the individual level, those with difficulties in emotion regulation may be at increased risk for harms related to hate speech exposure. Clinicians who are aware of these risks could discuss this vulnerability with patients. Most importantly, informing people of potential harms could help them become more responsible consumers. People may choose to be exposed to hate speech online while engaged in activities that are important to them, such as ensuring that others are aware of what they are going through. Yet, people could be made aware that reducing exposure to all forms of digital terror may be protective for their health4.

Study limitations are noted. First, although the direction modeled is logical, regression analysis of cross-sectional data cannot determine the directionality of the associations, which may be reciprocal. Longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the possibly complex temporal and causal relationship of online hate speech with PTSD. Second, these data were collected during ongoing war trauma, quite close to the mass terror event; associations may differ over time or in other populations with less trauma exposure. Third, a range of risk factors for PTSD were included in the model, but there may be other important measures that should be included for a more complete picture. Fourth, there may have been selection bias, as only those able to participate in the online survey could participate, but quotas were used to collect a quasi-representative sample of the adult, Jewish, Hebrew-speaking population of Israel. The sample was not representative of population sectors that would need methodological adaptations, e.g., those with cultural differences or less likely to complete online surveys. Additional studies in more diverse samples should confirm and build on these results. Fifth, while validated screening tools were used for PTSD symptomology and technology addiction, in-house measures were used for trauma exposures and perception of prior mental health issues. Specifically, a single item was used to assess frequency of hate speech (via social media), which is useful for initial assessment, but limited. Future studies should investigate more details, e.g., what is being targeted (respondent, community, country), why they are being targeted, the context of the hate speech, and which platforms they are on, to better define and validate a hate speech construct. Last, the distribution of most of the study variables differed by gender or age (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2); further studies should explore if the relationship between online hate speech exposure and PTSD differs by age or gender.

In conclusion, this study adds novel information about the potential role of online hate speech in PTSD vulnerability, in the context of other key PTSD risk factors. Results may have implications for public health, suggesting that policies could be developed to reduce the exposure to and impact of online hate speech on the societal and individual levels. It could be helpful for individuals exposed to traumatic events to be aware of the potential for hate speech to exacerbate their distress, especially if they have difficulties in emotion regulation. Clinicians seeing patients with vulnerability to psychopathology could discuss their social media use, specifically their reactions to online hate speech, and assist development of adaptive emotion regulation strategies. Ultimately, further understanding of the complex risks for PTSD can help the development of more precise prevention and intervention strategies.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Schincariol, A., Orrù, G., Otgaar, H., Sartori, G. & Scarpazza, C. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) prevalence: an umbrella review. Psychol. Med. 54, 1–14 (2024).

Valkenburg, P. M., Beyens, I., Meier, A. & Vanden Abeele, M. M. P. Advancing our understanding of the associations between social media use and well-being. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 47, 101357 (2022).

Nesi, J. et al. Social media use and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 87, 102038 (2021).

Holman, E. A., Garfin, D. R. & Silver, R. C. It matters what you see: graphic media images of war and terror may amplify distress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 121, e2318465121 (2024).

Parker, S. & Ruths, D. Is hate speech detection the solution the world wants? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 120, e2209384120 (2023).

Bührer, S., Koban, K. & Matthes, J. The WWW of digital hate perpetration: what, who, and why? A scoping review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 159, 108321 (2024).

Kansok-Dusche, J. et al. A systematic review on hate speech among children and adolescents: definitions, prevalence, and overlap with related phenomena. Trauma. Violence Abuse. 24, 2598–2615 (2023).

Walther, J. B. Social media and online hate. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 45, 101298 (2022).

Reichelmann, A. et al. Hate knows no boundaries: online hate in six nations. Deviant Behav. 42, 1100–1111 (2021).

Wypych, M. & Bilewicz, M. Psychological toll of hate speech: the role of acculturation stress in the effects of exposure to ethnic slurs on mental health among Ukrainian immigrants in Poland. Cultur Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 30, 35–44 (2024).

Nguyen, T. Merging public health and automated approaches to address online hate speech. AI Ethics. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-023-00281-w (2023).

Wachs, S., Gámez-Guadix, M. & Wright, M. F. Online hate speech victimization and depressive symptoms among adolescents: the protective role of resilience. Cyberpsychol Behav. Soc. Netw. 25, 416–423 (2022).

Saha, K., Chandrasekharan, E. & De Choudhury, M. Prevalence and psychological effects of hateful speech in online college communities. Proc. ACM Web Sci. Conf. 2019, 255–264 (2019).

Conti, L. et al. Emotional dysregulation and post-traumatic stress symptoms: which interaction in adolescents and young adults? A systematic review. Brain Sci. 13, 1730 (2023).

Tull, M. T., Barrett, H. M., McMillan, E. S. & Roemer, L. A preliminary investigation of the relationship between emotion regulation difficulties and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Behav. Ther. 38, 303–313 (2007).

McRae, K. & Gross, J. J. Emotion regulation. Emotion 20, 1–9 (2020).

Sheppes, G., Suri, G. & Gross, J. J. Emotion regulation and psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 11, 379–405 (2015).

Gross, J. J. & Jazaieri, H. Emotion, emotion regulation, and psychopathology. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2, 387–401 (2014).

Gámez-Guadix, M., Wachs, S. & Wright, M. 'Haters back off!’ Psychometric properties of the coping with cyberhate questionnaire and relationship with well-being in Spanish adolescents. Psicothema 32, 567–574 (2020).

Rogier, G., Muzi, S. & Pace, C. S. Social media misuse explained by emotion dysregulation and self-concept: an ecological momentary assessment approach. Cogn. Emot. 38, 1261–1270 (2024).

Goldman, S. et al. October 7th mass casualty attack in israel: injury profiles of hospitalized casualties. Ann. Surg. Open. 5, e481 (2024).

Jaffe, E. et al. Managing a mega mass casualty event by a civilian emergency medical services agency: lessons from the first day of the 2023 Hamas-Israel war. Int. J. Public. Health. 69, 1606907 (2024).

Roe, D., Gilboa-Schechtman, E. & Baumel, A. Digital terror: its striking impact on public mental health. Psychiatr Serv. 76, 99–101 (2025).

Enav, Y., Shiffman, N., Lurie, I. & Mayer, Y. Navigating the battlefield within: exploring the interplay of political armed conflict, mental health, and emotion regulation. J. Affect. Disord. 368, 16–22 (2025).

Levi-Belz, Y., Groweiss, Y., Blank, C. & Neria, Y. PTSD, depression, and anxiety after the October 7, 2023 attack in israel: a nationwide prospective study. EClinicalMedicine 68, 102418 (2024).

Feingold, D., Neria, Y. & Bitan, D. T. PTSD, distress and substance use in the aftermath of October 7th, 2023, terror attacks in Southern Israel. J. Psychiatr Res. 174, 153–158 (2024).

Thompson, R. R., Jones, N. M., Holman, E. A. & Silver, R. C. Media exposure to mass violence events can fuel a cycle of distress. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav3502 (2019).

Shmulewitz, D. et al. Comorbidity of problematic substance use and other addictive behaviors and anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder: a network analysis. Psychol Med Dec. 6, 1–11 (2024).

Shmulewitz, D., Eliashar, R., Levitin, M. D. & Lev-Ran, S. Test characteristics of shorter versions of the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST) for brief screening for problematic substance use in a population sample from Israel. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Policy. 18, 58 (2023).

Fricker, R. D. Sampling methods for online surveys. In The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods (eds Fielding, N. G. et al.) 184–202 (SAGE, 2016).

Central Bureau of Statistics. (2023). www.cbs.gov.il/he/Pages/default.aspx

iPanel. Available from: www.ipanel.co.il/en/

Belackova, V. & Drapalova, E. Web Surveys as a Method for Collecting Information on Patterns of Drug Use and Supply. (2022). Available from: www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/insights/web-surveys/web-surveys-method-collecting-information-patternsdrug-use-supply_en

Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K. & Domino, J. L. The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J. Trauma. Stress. 28, 489–498 (2015).

Forkus, S. R. et al. The posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) checklist for DSM-5: A systematic review of existing psychometric evidence. Clin. Psychol. (New York). 30, 110–121 (2023).

Victor, S. E. & Klonsky, E. D. Validation of a brief version of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale (DERS-18) in five samples. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 38, 582–589 (2016).

Andreassen, C. S. et al. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 30, 252–262 (2016).

Casale, S., Akbari, M., Seydavi, M., Bocci Benucci, S. & Fioravanti, G. Has the prevalence of problematic social media use increased over the past seven years and since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic? A meta-analysis of the studies published since the development of the Bergen social media addiction scale. Addict. Behav. 147, 107838 (2023).

Kwon, M., Kim, D. J., Cho, H. & Yang, S. The smartphone addiction scale: development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS One. 8, e83558 (2013).

Bouazza, S., Abbouyi, S., El Kinany, S., El Rhazi, K. & Zarrouq, B. Association between problematic use of smartphones and mental health in the middle East and North Africa (MENA) region: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 20, 2891 (2023).

Young, K. S. Internet addiction: the emergence of a new clinical disorder. CyberPsychology Behav. 1, 237–244 (1998).

Pawlikowski, M., Altstötter-Gleich, C. & Brand, M. Validation and psychometric properties of a short version of Young’s internet addiction test. Comput. Hum. Behav. 29, 1212–1223 (2013).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction To Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (The Guilford Press, 2022).

Fox, J., Wiesberg, S. & Price, B. car: Companion to Applied Regression. Available at: https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.car

Frossard, J. & Renaud, O. permuco: Permutation Tests for Regression, (Repeated Measures) ANOVA/ANCOVA and Comparison of Signals. Available at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=permuco

Haws, J. K. et al. Examining the associations between PTSD symptoms and aspects of emotion dysregulation through network analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 86, 102536 (2022).

Wolfers, L. N. & Utz, S. Social media use, stress, and coping. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 45, 101305 (2022).

Schivinski, B. et al. Exploring the role of social media use motives, psychological well-being, self-esteem, and affect in problematic social media use. Front. Psychol. 11, 617140 (2020).

Tolin, D. F. & Foa, E. B. Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: a quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 132, 959–992 (2006).

Olff, M., Langeland, W., Draijer, N. & Gersons, B. P. R. Gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol. Bull. 133, 183–204 (2007).

Peng, P. et al. The prevalence and risk factors of mental problems in medical students during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 321, 167–181 (2023).

Contractor, A. A., Frankfurt, S. B., Weiss, N. H. & Elhai, J. D. Latent-level relations between DSM-5 PTSD symptom clusters and problematic smartphone use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 72, 170–177 (2017).

Lee, J. Y. et al. Relationship between problematic internet use and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among students gollowing the Sewol ferry disaster in South Korea. Psychiatry Investig. 14, 871–875 (2017).

Melca, I. A., Teixeira, E. K., Nardi, A. E. & Spear, A. L. Association of internet addiction and mental disorders in medical students: A systematic review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 25, 22r03384 (2023).

Tullett-Prado, D., Doley, J. R., Zarate, D., Gomez, R. & Stavropoulos, V. Conceptualising social media addiction: a longitudinal network analysis of social media addiction symptoms and their relationships with psychological distress in a community sample of adults. BMC Psychiatry. 23, 509 (2023).

Pe’er, A. & Slone, M. Media exposure to armed conflict: dispositional optimism and self-mastery moderate distress and post-traumatic symptoms among adolescents. Int J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19, 11216 (2022).

Levaot, Y., Palgi, Y. & Greene, T. Social media use and its relations with posttraumatic symptomatology and wellbeing among individuals exposed to continuous traumatic stress. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 59, 6–14 (2022).

Slone, M., Peer, A. & Egozi, M. Adolescent vulnerability to internet media exposure: the role of self-mastery in mitigating post-traumatic symptoms. Int J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 22, 589 (2025).

Naim, S. & Gigi, A. The role of alexithymia and maladaptive coping in long-term trauma: insights from the aftermath of the October 7th attacks. J. Psychiatr Res. 187, 254–260 (2025).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Pat-Horenczyk, R. & Schiff, M. Continuous traumatic stress and the life cycle: exposure to repeated political violence in Israel. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 21, 71 (2019).

De Schryver, M., Vindevogel, S., Rasmussen, A. E. & Cramer, A. O. J. Unpacking constructs: A network approach for studying war exposure, daily stressors and post-traumatic stress disorder. Front. Psychol. 6, 1896 (2015).

María-Ríos, C. E. & Morrow, J. D. Mechanisms of shared vulnerability to post-traumatic stress disorder and substance use disorders. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 14, 6 (2020).

Smith, N. D. L. & Cottler, L. B. The epidemiology of post-traumatic stress disorder and alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Res. 39, 113–120 (2018).

Levin, Y. et al. The association between type of trauma, level of exposure and addiction. Addict. Behav. 118, 106889 (2021).

Starcevic, V. & Khazaal, Y. Relationships between behavioural addictions and psychiatric disorders: what is known and what is yet to be learned? Front. Psychiatry 8, 53 (2017).

Turner, S., Mota, N., Bolton, J. & Sareen, J. Self-medication with alcohol or drugs for mood and anxiety disorders: A narrative review of the epidemiological literature. Depress. Anxiety. 35, 851–860 (2018).

Chung, S. & Lee, H. K. Public health approach to problems related to excessive and addictive use of the internet and digital media. Curr. Addict. Rep. 10, 69–76 (2023).

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.S. came up with the idea for the study, was responsible for the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript text, and prepared the tables and figure. M.D.L helped with the methodology and interpretation of results. V.S. and M.V. were responsible for data curation. M.M. helped with interpretation of results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shmulewitz, D., Levitin, M.D., Skvirsky, V. et al. Exposure to online hate speech is positively associated with post-traumatic stress disorder symptom severity. Sci Rep 15, 29869 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16168-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16168-1