Abstract

Ecological restoration has become a critical tool for mitigating ecosystem degradation and enhancing ecological health. Effective restoration efforts require regionalisation through identifying of social-ecological system (SES) that integrate socioeconomic and ecological characteristics. However, methodological gaps in clarifying interdimensional interplay often hinder coastal restoration planning. This study develops a spatial characterisation framework to identify coastal SESs for targeted ecological restoration in Zhejiang Province, China. Integrating socioeconomic data and land-marine ecological variables across 28 coastal counties, we employed principal component analysis and hierarchical clustering to delineate nine distinct SESs exhibiting significant heterogeneity: northern clusters (SES1/7/9) show high socioeconomic performance but suboptimal environmental indicators; southern systems (SES2/8) feature lower development but superior environmental conditions; central zones (SES5/6) demonstrate moderate socioeconomic-environmental profiles; while island systems (SES3/4) display low population density, high aging rates, and unique biogeophysical traits. Precise SES categorization enabled identification of primary degradation pressures and formulation tailored restoration strategies within each SES in Zhejiang. Critically, transcending administrative boundaries is essential to accommodate intra-city diversity and cross-city unity, given prevalent transboundary SESs and intra-city variations. We propose four management implications: ecosystem service conservation, pressure-specific interventions, cross-sector governance mechanisms, and participatory restoration incentivization. This framework establishes a transferable approach for sustainable coastal SES restoration management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past centuries, the uncontrolled exploitation and utilization of natural resources by humans have had tremendous impacts on the Earth system. Drastic changes in the global land use/cover patterns, along with the accumulation of resource and environmental pressures, have led to a series of problems and challenges such as environmental pollution, ecosystem degradation, and biodiversity loss, all of which threaten the sustainability of human well-being1. To emphasize the seriousness of this ecological crisis, the United Nations has declared 2020–2030 the Decade of Ecosystem Restoration2. Ecological restoration is defined as the effort to aid the recovery of a degraded, damaged, or destroyed ecosystem intending to restore its integrity, including individual, cultural, socioeconomic, and ecological values to enhance social–ecological resilience3. Consequently, extensive ecological restoration has become a global priority and is now regarded as essential for ensuring sustainability4. China is actively promoting ecological restoration nationwide, viewing it as a crucial component of its ecological civilization, and has achieved positive outcomes5. This makes China an excellent case study area for adaptive restoration efforts aimed at achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in the future.

Regionalisation is essential for ecological restoration and forms the basis for formulating relevant policies and planning6,7. Identifying priority areas for ecological restoration is currently a major focus in research8,9. Three primary methods are commonly used: (1) constructing a framework utilizing multiple indicators for ecological status assessment10,11; (2) conducting regionalisation according to ecological dynamics guided by ecosystem service theory12,13; and (3) identifying priority areas under multiple or simulated scenarios14,15. Most of these studies primarily consider the ecosystem itself. Various ecological variables are employed to simulate different stages of ecological progress, identifying areas vulnerable to degradation. For example, ecosystem services are assessed using various ecological models, identifying areas where values are low or declining as priority restoration areas16,17,18. However, these criteria often overlook the interaction between regional socioeconomic development and ecological conservation, a critical factor for effective local ecological restoration.

Social-ecological systems (SES) are complex adaptive systems where social and bio-geophysical dimensions interact across multiple temporal and spatial scales19,20,21. Understanding the interactions between ecological and social systems is crucial for achieving sustainability and plays a vital role in effective ecological restoration planning22,23. However, the diversity of SES, where social and biogeophysical dimensions interact on multiple spatial and temporal levels, makes it challenging to grasp the associations between social, economic, and ecological components24,25. Scholars tend to develop simple theoretical models to analyse aspects of SES and prescribe one-size-fits-all solutions, but frequently fails. Only a common, classificatory, and multilevel framework has been proposed to identify relevant variables for studying a single focal SES24,26. This framework includes core subsystems such as economic development, demographic trends, political stability, government policies, market incentives, and related ecosystems, etc. Coastal areas are home to hundreds of millions of people and the majority of the world’s cities. Humans have long enjoyed the benefits of coastal ecosystems, including food sources, disaster mitigation, and recreational experiences, etc27,28,29. At the same time, coastal systems face serious risks, including coastal erosion, contamination, and species decline, which jeopardise the ecosystem services they offer30,31. Restoring degraded coastal ecosystem services through sustainable strategy and planning requires a deep understanding of intricate interconnections within coastal social-ecological systems (SES)6. However, empirical evidence is lacking on how these relationships manifest spatially—specifically, the spatial composition and configuration of coastal SES. While several methods have been proposed to map ecosystem services or human impacts on coastal areas, only a limited number of studies have devised instruments to depict SES spatially22,32. The limited advancement in methodologies for spatial characterisation of SES is a major drawback to the use of the SES framework in ecological restoration management, potentially leading to mismanagement6,33. Additionally, evidence shows that marine environmental conditions strongly impact the structure and function of terrestrial SES, complicating the characterisation of coastal SES20. Given the interconnected nature land-marine ecosystems and socioeconomic systems, it is crucial to account for the linkages between marine and terrestrial elements in ecological restoration in coastal areas. Therefore, spatially identifying and characterising SES by analysing socioeconomic and land-marine ecological characteristics has become pivotal for ecological restoration, forming the core focus of this study.

In the subsequent sections, this study will develop a comprehensive assessment framework based on socioeconomic and land-marine ecological data to characterise and spatially identify SES in coastal areas. We will test this framework on the coast of Zhejiang Province, China, to help delineate boundaries of ecological restoration. Accurate regionalisation of coastal areas can aid in prioritizing comprehensive management and planning tailored to each SES for effective ecological restoration.

Methods

Study area

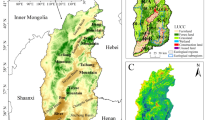

The study area is situated along the coast of the East China Sea in Zhejiang Province, eastern China (Fig. 1). This study examines 6,700 km of coastline, spanning 28 counties across 6 cities (Jiaxing, Shaoxing, Ningbo, Zhoushan, Taizhou, and Wenzhou) of Zhejiang Province. Zhejiang’s zigzagged coastlines feature diverse terrestrial and marine activities, ranging from conservation areas like Hangzhou Bay National Wetland Park in Ningbo to highly developed regions and fishing zones, including Ningbo-Zhoushan Port and the Zhoushan fishing ground. The coastline of Zhejiang exhibits significant environmental variability due to complex hydrodynamic conditions, influenced by the Yangtze River to the northwest, the Taiwan Warm Current to the southwest, and the Qiantang River in the middle. Consequently, the marine environment and ecological condition of the Zhejiang coastal area are strongly influenced by these three currents. As a result, the coastal area encompasses diverse ecosystems, including reed wetlands, aquaculture, farmland, forest, mangroves, salt pans, coastal sand land, rocky reefs, and seagrasses. These features make the East China Sea a global hotspot for marine biodiversity.

Since China’s economic reform and opening-up period began in the 1980 s, Zhejiang Province has undergone large-scale conversion of natural coastal ecosystems. Mirroring global trends, rural populations in the province have declined while urban populations have surged in coastal cities. Consequently, rapid construction land expansion has encroached upon ecological spaces such as woodlands, grasslands, wetlands, and water bodies, leading to the degradation of natural ecosystems in some regions. Furthermore, coastal cities have heavily relied on land reclamation as a primary strategy to expand terrestrial areas from the sea and wetlands to meet land demand. These demographic, economic, and sociopolitical drivers transform land use change into a direct driver of environmental change, causing ecological issues such as habitat loss and ecosystem degradation that pose significant risks to ecological health. Specifically, coastal cities in Zhejiang face ecosystem pressures due to unsustainable land use practices, manifested in the following key challenges:

-

1.

Intensive yet inefficient coastal development. Coastal development is characterized by large scale and high intensity but suffers from relatively low levels of utilization efficiency. The industrial layout along the coast is often suboptimal, lacking significant agglomeration effects. Construction land and aquaculture excessively occupy the coastal area. Currently, natural coastline accounts for only about 36% of Zhejiang’s total coastline length. Moreover, development activities frequently fail to adequately preserve ecological spaces such as green areas and water bodies.

-

2.

Prominent historical reclamation legacy. Historical land reclamation projects, such as coastal development, seawall construction, and industrial park establishment in cities like Taizhou and Ningbo, have led to significant reduction or complete loss of coastal wetlands. The area of coastal tidal flats has continuously decreased, destabilizing habitats, diminishing the bay area’s defence capacity against marine disasters, and causing a sharp decline in biodiversity.

-

3.

Degradation of critical coastal ecosystems. The total area of key coastal ecosystems, including mangroves and seagrass beds, has been continuously declining, accompanied by reduced species abundance. Pollution from industrial, agricultural, and domestic sources, coupled with the invasion of alien species like Spartina alterniflora, has further caused significant species loss, decreased biodiversity, and weakened the resilience of ecosystems.

Collectively, the pressures arising from these land use changes significantly alter coastal SES and the ecosystem services they provide. Given its ecological importance and high biodiversity value, Zhejiang has become a leading demonstration area for ecological civilization construction, necessitating high-quality ecological restoration. However, despite this need, no comprehensive zoning for coastal ecological restoration had been previously conducted, beyond the broad strategies outlined in the Planning for Ecological Restoration of Territorial Space of Zhejiang Province (2021–2035) (Ecological Plan for short) (https://zrzyt.zj.gov.cn/art/2023/9/25/art_1289924_59023378.html).

Data sources

Following the methodology outlined by Lazzari et al.20we gathered socioeconomic and land-marine ecological data to classify and describe spatial categories that are uniform within but differ among the SESs. Based on assessments of pertinent research, expert input, and the unique study context, we selected four categories of variables: demography, economic factors, marine conditions, and terrestrial ecosystems (Table 1)33,34,35,36. The selection of these variables was grounded in both conceptual and empirical studies (Table S1).

Specifically, this study utilizes fundamental data, including:

-

1.

Marine ecological data from the period 2010–2020 obtained from the satellite database Bio-ORACLE, which offers extensive environmental data with global extent and uniform resolution for marine research and is freely accessible37. Nine marine variables essential for marine ecological health and biodiversity were considered: basic properties (mean salinity, surface temperature, and pH), inorganic carbon (mean calcite concentration), primary productivity (mean primary productivity and chlorophyll a), and nutrients (mean nitrate, phosphate, and silicate concentrations). The values of these nine variables were retrieved from ocean pixels adjacent to the coastline, with a spatial resolution of 0.05 degrees (approximately 5.8 km at the study area). Each county’s marine ecological value was derived by averaging the pixel values of each marine ecological variable within the county (Table S4).

-

2.

GlobeLand30 data for 2020, covering 10 categories of land cover: artificial surfaces, forest, shrubland, water bodies, grassland, cultivated land, wetland, tundra, bareland, and permanent snow) (http://www.webmap.cn/mapDataAction.do?method=globalLandCover) (Table S5). Based on the current land use in Zhejiang Province, the surface cover types were classified into six categories: cultivated land, forest, grassland, built-up, wetland, and water bodies. This classification enabled a quantitative assessment of terrestrial ecological conditions.

-

3.

Land ecological protection, environmental pressure, demography, and economic status data of counties, derived from the 2020 statistical yearbooks of each city (Jiaxing City, Ningbo City, Zhoushan City, Taizhou City, and Wenzhou City) (Table S5). The datasets are available for download from China’s Statistics database (https://www.shujuku.org/category/dongbu/zhejiang-statistical-yearbook/). The county was selected as the appropriate level for collecting statistical data because it represents the finest administrative unit with available official statistics.

Data analysis

The methodology comprised four phases (Fig. 2): (1) ecological regionalisation involves identifying and characterising spatially homogeneous units based on landscape types, ecological protection, environmental pressure, and adjacent marine variables; (2) socioeconomic regionalisation entails identifying and characterising counties that are homogeneous based on demographic and economic variables; (3) delineation of SES boundaries and characterisation of social-ecological units; and (4) validation of SES boundaries by comparing them with the ecological restoration areas in Ecological Plan.

Specifically, we first conducted a principal component analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation on the ecological and socioeconomic data to streamline variable dimensions and uncover predominant relationships among them. We chose PCA components based on the Kaiser criterion, specifically those with eigenvalues greater than 1. Secondly, we performed two hierarchical cluster analyses (HCA) on the PCA components of socioeconomic and ecological data to delineate homogeneous classes in each domain. Euclidean distance and Ward’s method were utilized as agglomerative hierarchical techniques38. Thirdly, we conducted one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine differences in the variables considered across the multiple classes identified by ecological and socioeconomic HCAs. Post-hoc Tukey tests were employed for pairwise comparisons. Initially, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality in all variables. Fourthly, we conducted a Chi-squared contingency table analysis to examine the association between the identified ecological and socioeconomic classes, which helped identify the SESs. Radar charts were utilized to visualize the impact of socioeconomic and ecological variables on each SES. These analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 26. Finally, using the map of ecological restoration areas in the Ecological Plan, the SESs were evaluated in terms of the fit between their spatial distribution patterns.

Results

Socioeconomic regionalisation

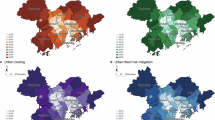

The PCA identified four components with eigenvalue > 1 that explained 84.91% of the variability (Table S2). Using these four PCA components in the HCA, we subsequently identified four socioeconomic classes (SCs) (Table 2). The distributions of SCs were mapped respectively (Fig. 3). It was observed that the counties within SC1 were concentrated in the northern region. Bordering SC1 to the south are the counties within SC4, which contains most of the islands in the study area. In contrast, the counties within SC2 and SC3 are scattered in the central and southern regions.

All the counties had high population densities, and the counties within SC2 had the highest population density (1669.51 inhabitants km−2), but they differed in population growth (Table 2). Counties within SC2 and SC3 observed the fastest population growth (3.56‰ and 2.17‰, respectively), while the population of counties within SC1 barely changed. Notably, negative population growth occurred in the counties within SC4, which were also characterised by the highest proportion of the population over 65 years old (17.07%). In terms of educational level, the counties within SC3 had the highest rate of illiterate people (8.26%). Economically, the primary sector in SC4 counties accounted for the highest proportion (12.21%) of the industrial structure, and the fishery accounted for the largest proportion (74.61%) of the output of the primary sector. In contrast, SC1 represented the counties with the highest proportion of GDP output in the secondary sector (56.60%). SC1 also had the highest GDP per capita (137,100 Yuan). Regarding the variables of tertiary sector and animal husbandry, all counties showed that the proportion of tertiary sector in the industrial structure was relatively high, while the proportion of animal husbandry in the primary sector was low, but no significant difference among the SCs was observed.

Ecological regionalisation

The first five components of the PCA accounted for over 78.84% of the ecological data variability in the study area. Table S3 presents the eigenvalue distribution and the explained variability of each PCA component for the respective case studies. Utilizing these five PCA components in the HCA enabled us to classify the ecological data into four distinct classes (ECs) (Fig. 4; Table 3). All ECs exhibited spatial agglomeration patterns at latitude (Fig. 4). The counties within EC1 and EC3 were concentrated in the Zhoushan Islands in the northeast and the plain around Hangzhou Bay in the north, respectively. EC2 represented 11 counties and was the most widely distributed ecological class from central to south, while EC4 was confined to the southeastern corner.

Regarding land uses, the counties of EC2, EC3, and EC4 were characterised by the largest area covered by forest (49.59%), cultivated land (53.18%) and built-up (33.6%), respectively (Table 3). EC1 represented the counties with the lowest proportion of cultivated land (20.79%) and a relatively high proportion of forest (36.66%), built-up (25.1%) and grassland (9.31%). Wetlands and water bodies all accounted for low proportions of land in the study area and had no significant difference among the ECs. For ecological protection, all the counties had a moderate green coverage rate in urban space, and the counties within EC2 demarcated the highest proportion of terrestrial ecological reserve area (18.76%). Regarding pressure, the counties of EC3 and EC4 faced greater challenges of environmental pollution and ecological degradation risks. EC4 engaged in extensive coastal land reclamation to satisfy the burgeoning need for land amidst rapid urbanisation. However, this practice has led to significant ecological concerns, including habitat fragmentation, wetlands degradation, and biodiversity decline. EC3 was characterised by the greatest annual wastewater discharge (22.28 million tons) and the highest mean PM2.5 concentrations (27.17 µg m−3). In addition, EC3 had the highest annual agricultural fertilizer usage (15,024 tons), resulting in a high risk of nitrogen and phosphorus runoff from agricultural land. In terms of marine ecological variables, the counties of EC3 were characterised by the highest concentrations of mean chlorophyll a (1.14 mg m−3), mean nitrate (47.17 mol m−3), mean primary productivity (0.04 g m−3day−1), and mean silicate (59.41 mol m−3), whereas EC4 was characterised by the highest values of mean salinity (27.55‰) and mean temperature (20.25 °C).

Characterisation of SESs

A notable link was identified between the socioeconomic and ecological classifications (χ2 = 31.37; p < 0.001), which resulted in nine SESs (Fig. 5). SC1 was associated by three ECs, i.e., EC1, EC2, and EC3, comprising SES1, SES7, and SES9. The other three SCs were linked to different pairs of ECs. Geographically, SES1 was situated in the plain around Hangzhou Bay in the north of the study area (Fig. 6) and was characterised by high levels of cultivated land proportion, PM2.5 concentrations, agricultural fertilizer usage in the land, along with high levels of chlorophyll a, nitrate, primary productivity, silicate in the marine environment (Fig. 7). SES7 was located centrally along the Ningbo coastline (Fig. 6), characterised primarily by counties exhibiting high GDP per capita. Additionally, these areas demonstrated significant secondary sector activity and substantial development in industrial structure and land utilization (Fig. 7). Environmentally, SES7 had a high level of wastewater discharge (Fig. 7). SES9 represented only Fenghua County (Fig. 6), which also had a high GDP output rate of the secondary sector and the highest representation of forest and terrestrial ecological reserves (Fig. 7).

SC2 and SC3 were associated with the same ECs (EC2 and EC4), comprising SES6, SES5, SES2, and SES8, respectively (Fig. 5). SES6 and SES5 shared similar socioeconomic attributes but diverged notably in ecological features, particularly concerning built-up areas and coastal land reclamation. As a result, they represented distinct coastal regions encompassing Wenzhou, Taizhou, and Ningbo (Fig. 6). It is remarkable that the counties within SES6 or SES5 did not border each other and were distributed across cities. For example, Yinzhou and Yueqing County within SES6 were located in Ningbo and Wenzhou City, respectively. SES2 and SES8 had similar characteristics due to the same socioeconomic variables of SC3 in terms of a low level of GDP per capita and a high percentage of illiterate people (Fig. 7). The differences between SES2 and SES8 in southern Taizhou and eastern Wenzhou also depended on ecological aspects. In contrast, SES2 exhibited a significant forest cover and the least amount of construction land, while SES8 shared similarities with SES5, particularly in having a substantial proportion of reclaimed coastal land. For marine variables, both SES2 and SES8 had a high level of mean salinity and mean temperature because they were in the southern of the study area (Fig. 6).

SC4 was associated with EC1 and EC2 representing two coastal social-ecological systems: SES3 and SES4. Both SES3 and SES4 were characterised by numerous islands but were distinctively located in different regions: SES3 represented the Zhoushan Islands, and SES4 represented unique counties in Ningbo and Taizhou City (Fig. 6). Due to the geographical features of multiple islands, SES3 and SES4 had similar socioeconomic characteristics in terms of a low level of people density and a high proportion of people older than 65. The administrative differences also led to distinct socioeconomic traits. Whereas SES3 was characterised by the highest proportion of primary sector output and fishery output and the lowest rate of population growth and secondary sector output, SES4 exhibited moderate values across all socioeconomic indicators. In terms of land use, both SES3 and SES4 were characterised by a high proportion of forest and a low proportion of cultivated land and built-up. Ecologically, SES3 had the lowest terrestrial environmental pollution pressure, while SES4 had the best marine environment in the entire study area.

Socioeconomic and ecological variables that characterise the SESs. The peripheral numbers from 1 to 22 are codes for the variables: (1) population density, (2) population growth, (3) illiterate people, (4) people older than 65, (5) primary sector, (6) secondary sector, (7) GDP per capita, (8) Fishery output, (9) cultivated land, (10) forest, (11) built-up, (12) terrestrial ecological reserve, (13) coastal land reclamation, (14) wastewater discharge, (15) average PM2.5 concentration, (16) agricultural fertilizer usage, (17) mean chlorophyll a, (18) mean nitrate, (19) mean primary productivity, (20) mean salinity, (21) mean silicate, and (22) mean surface temperature.

Validation of the identification of SESs

Using the map of ecological restoration areas (ERAs) in the Ecological Plan (Fig. 8), the SESs were evaluated in terms of the fit between their spatial distribution patterns (Table 4). Regarding the Ecological Plan, the coast of Zhejiang Province was divided into four ERAs: Hangzhou Bay area (ERA1), Zhoushan Islands area (ERA2), Xiangshan Port area (ERA3), and Wenzhou-Taizhou coast area (ERA4), under the principle of spatial agglomeration. The SESs empirically identified had a generally satisfactory fit to the ERAs, especially in the northern area. However, there were a few conflicts between the SESs and ERAs in the central regions. Compared with the Ecological Plan that simply divided the study area into two ERAs: the Xiangshan Port area and the Wenzhou-Taizhou coast area, this empirical study accurately identified 3 and 5 SESs from these two ERAs, respectively.

Discussion

Ecological restoration under homogeneous social-ecological conditions

Recent research highlights the crucial role of comprehending the intricacies within social-ecological systems to achieve sustainability19,24. Ecological restoration, pivotal for sustainable development, is also intricately intertwined with social-ecological dynamics5. Prior investigations indicate that ecological restoration hinges on the interplay between ecosystems and socioeconomic structures, aiming to reinstate harmonious development in social ecosystems39,40. However, reaching this coordinated development state is becoming increasingly challenging due to social and ecological heterogeneity. Hence, in the planning of ecological restoration, it is essential to address how to manage and alleviate the impacts of variability in social and ecological conditions. Various studies have applied the Stress-Response framework and empirical data to assess and evaluate changes in social-ecological systems before and after interventions in coastal environments11,33. Furthermore, researchers have proposed refining the framework for ecological restoration to better respond to social-ecological transformations, though specific methodologies require further exploration41,42.

This study identifies nine SESs through integrated spatial characterisation of socioeconomic conditions and land-marine ecological change impacts. The specific marine ecological and socioeconomic drivers underlying SES similarities and differences are essential for designing effective management measures and evidence-based policies26.

For example, three SESs coexist in Taizhou City: SES4, SES5, and SES8. All fall under the Ecological Plan’s ERA4 restoration framework. However, management strategies must differ according to their unique characteristics. Ecologically, SES5 and SES8 share similar traits, whereas SES4 differs in both ecological and socioeconomic dimensions. These ecological distinctions stem from differential land use structures and conservation investments: SES4 features the largest forest coverage and highest proportion of terrestrial protected areas, while SES5 and SES8 are characterized by extensive built environments and coastal reclamation driven by rapid urbanisation. Consequently, SES5 and SES8 face greater environmental pollution and degradation risks than SES4. These areas should strictly demarcate urban development boundaries to prevent ecosystem disruption, optimize urban-rural spatial layouts, implement industrial land intensification policies, and conduct ecological restoration in historically reclaimed coastal areas through: (1) natural shoreline rehabilitation, (2) coastal wetland restoration, and (3) marine biota recovery. For SES4, the priority should be enhancing ecosystem functions through optimized tree species composition and strengthened forest ecosystem stability.

Socioeconomically, SES5 and SES8 face different challenges. Management actions directed to develop education programmes may result in increased awareness about the importance of the coast and the marine ecosystems conservation in SES8, which has a high percentage of illiterate people. Illiteracy-adaptive communication such as pictograms, flowcharts, and photo-based guides for restoration techniques and livelihood-linked incentives would be preferred in ecological restoration policy design8. In contrast, a greater potential challenge for SES5 might be dealing with human pressure, as this is the SES with the highest population density. This region requires strengthened governance of human settlements, including expanding urban green spaces through a networked system with community parks as hubs and regional green corridors as connectors, while elevating construction standards for wastewater and solid waste treatment facilities and promoting public adoption of eco-lifestyles such as low-carbon living practices and waste sorting initiatives. These examples illustrate how categorizing SESs can aid in formulating tailored management strategies and policies for ecological restoration that address the diverse human-environment dynamics.

Moreover, our findings suggest city-scale governance initiatives may prove ineffective, given that five SESs span multiple administrative boundaries (Fig. 6): SES1 (Jiaxing-Shaoxing-Ningbo), SES2/SES5 (Taizhou-Wenzhou), SES4 (Ningbo-Taizhou), and SES6 (Ningbo-Wenzhou). Simultaneously, significant intra-city SES diversity exists (e.g., four SESs in Taizhou, three in Wenzhou). Current city-based restoration planning fails to address either cross-jurisdictional SES homogeneity or intra-city heterogeneity. Effective regionalization requires transcending administrative boundaries to align management with ecological-economic realities, accommodating municipal diversity while harnessing cross-city synergies.

Management implications for coastal ecological restoration

Considering the above findings, we argue that ensuring sustainable coastal ecological restoration requires systematically understanding how management strategies can be tailored to each SES by addressing key supporting variables26. Beyond continuing current efforts, we recommend four interlinked policies: (a) prioritize conservation of coastal ecosystem services, (b) identify principal ecological degradation pressures, (c) establish coordinated organizational leadership mechanisms, (d) enhance public participation.

First, Sect. “Characterisation of SESs” demonstrates that differential proportions of land use types across SESs indicate diverse ecosystem service provisions. For example, SES1 contains the highest proportion of cultivated land while SES4 has maximal forest coverage. SES1 and SES4 demonstrate contrasting values: food production versus ecological regulation. This distinction must guide future management decisions. However, SES1 simultaneously faces pressure from agricultural fertilizer overuse and nitrogen/phosphorus water pollution, while SES4 contends with economic development constraints from ecological protection. Minimizing trade-offs and ensuring synergistic ecosystem services should therefore be primary considerations in land use planning formulation.

Second, Sect. “Characterisation of SESs” reveals that characteristic socioeconomic and ecological variables define each SES. Urban population shifts, economic development, and urbanisation drive significant land use changes (Sect. “Study area”), making land use activities direct drivers of ecosystem degradation. Consequently, single solutions are unlikely to resolve restoration challenges. Instead, identifying primary SES pressures provides essential entry points for comprehensive solutions. For example, addressing nutrient pollution in SES1 waters (Variables 16–19 in Fig. 7) requires integrated measures: reducing agricultural chemical inputs, controlling livestock waste discharge, and enhancing forest/wetland buffering capacity.

Third, clarifying stakeholder responsibilities within governance systems is essential for managing ecological pressure variables. We propose that provincial governments lead cross-jurisdictional restoration efforts, establishing coordination mechanisms across land resources, ecological environment, urban development, agriculture, industry, water management, and finance sectors (addressing variables in Table 2). This body should oversee implementation, monitoring, assessment, and adaptive management of restoration initiatives.

Fourth, leveraging new media platforms can amplify the visibility and demonstration effects of restoration work. Existing education and awareness efforts provide important foundations. However, achieving wider impacts demands linking outreach to incentive mechanisms. This is particularly crucial in contexts with competing interests. For example, integrating awareness programs with ecological compensation and financial incentives could strengthen collaboration in lower-GDP regions like SES2.

Methodological discussion

This study presents an effective approach to characterize and spatially identify the SESs in coastal areas, helping to delineate boundaries for ecological restoration to solve one of the key issues in territorial space restoration6. Although we identified multiple pressures and drivers responsible for ecosystem degradation, we did not quantitatively capture how these variables operate or interact. Instead, we identified potential variables that can serve as entry points for implementing comprehensive solutions. Insights from coastal Zhejiang should form the foundation for implementing sustainable ecological restoration policies to achieve synergies between economic prosperity and ecological security. However, several limitations warrant attention. First, due to the absence of key data, biological factors including wild species richness, ecosystem diversity, species endemism, invasive alien species, and threatened species were not considered. We suggest the identified SESs may also exhibit biodiversity variations. Efforts are underway to refine the SES framework to address this gap. Second, the presented framework suits restoration planning at county or municipal administrative scales but lacks sufficient detail for project or pixel level analysis, which requires more comprehensive perspectives. Finally, this study examined the social-ecological state circa 2020 without considering long-term historical dynamics that may have influenced system conditions. Future research should trace the analysis back to a longer historical period to gain a more comprehensive understanding.

Conclusion

This research develops a feasible methodology to characterize and spatially identify SESs in coastal areas, which helps delineate boundaries for ecological restoration and aids in formulating tailored management strategies and policies that address diverse human-environment dynamics. Focusing on the coast of the East China Sea in Zhejiang Province, we identified nine SESs. SES1, SES7, and SES9 are concentrated in the northern region and represent the highest performing counties socioeconomically, though some land and marine environmental indicators are suboptimal. SES2 and SES8 exhibit lower socioeconomic development levels but better environmental conditions. SES5 and SES6 demonstrate similar moderate levels of socioeconomic development and environmental conditions. Both SES3 and SES4 feature typical island geographical environments with comparable socioeconomic characteristics, including low population density and high aging rates.

By precisely categorizing SESs, this approach aids in formulating tailored ecological restoration strategies addressing the primary degradation pressures within each SES. Furthermore, our findings suggest that breaking constraints of administrative boundaries is necessary to accommodate both intra-city diversity and cross-city unity in restoration management, given the prevalence of transboundary SESs and intra-city variations. In addition to current restoration efforts, we recommend four management implications: emphasizing conservation of coastal ecosystem services, identifying principal ecological degradation pressures, establishing organizational leadership mechanisms, and encouraging public participation. The proposed methodology effectively combines different knowledge types to serve as a mutually acceptable approach for sustainable ecological restoration management of coastal SESs.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Pereira, H. M. et al. Global trends and scenarios for terrestrial biodiversity and ecosystem services from 1900 to 2050. Science 384, 458–465 (2024).

UNEA. Resolution 73/284: united nations decade on ecosystem restoration (2021–2030) (2019). https://undocs.org/A/RES/73/284

Jackson, S. T. & Hobbs, R. J. Ecological restoration in the light of ecological history. Science 325, 567–569 (2009).

Wortley, L., Hero, J. M. & Howes, M. Evaluating ecological restoration success: a review of the literature. Restor. Ecol. 21, 537–543 (2013).

Fu, B., Liu, Y. & Meadows, M. E. Ecological restoration for sustainable development in China. Natl. Sci. Rev. 10 (7). https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwad033 (2023).

Peng, J. et al. Ten key issues for ecological restoration of territorial space. Natl. Sci. Rev. 11 (7). https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwae176 (2024).

Lv, T. et al. Towards an integrated approach for land Spatial ecological restoration zoning based on ecosystem health assessment. Ecol. Indic. 147, 110016 (2023).

Peng, J. et al. Regarding reference state to identify priority areas for ecological restoration in a karst region. J. Environ. Manage. 348, 119214 (2023).

Tang, B. T. et al. Identification of ecological restoration priority areas integrating ecological security and feasibility of restoration. Ecol. Indic. 158, 111557 (2024).

Lei, K., Pan, H. & Lin, C. A landscape approach towards ecological restoration and sustainable development of mining areas. Ecol. Eng. 90, 320–325 (2016).

Liao, C. et al. Ecological restoration enhances ecosystem health in the karst regions of Southwest China. Ecol. Indic. 90, 416–425 (2018).

Bai, Y. et al. Developing china’s ecological redline policy using ecosystem services assessments for land use planning. Nat. Commun. 9, 3034 (2018).

Sitotaw, M., Willemen, T., Tsegaye Meshesha, L., Nelson, A. & D. & Empirical assessments of small-scale ecosystem service flows in rural mosaic landscapes in the Ethiopian highlands. Ecosyst. Serv. 67, 101622 (2024).

Acosta, A. L., d’Albertas, F., de Souza Leite, M., Saraiva, A. M. & Walter Metzger, J. P. Gaps and limitations in the use of restoration scenarios: a review. Restor. Ecol. 26, 1108–1119 (2018).

Li, M. et al. The cost–benefit evaluation based on ecosystem services under different ecological restoration scenarios. Environ. Monit. Assess. 193, 398 (2021).

Zhang, D. et al. Assessing the coordination of ecological and agricultural goals during ecological restoration efforts: A case study of Wuqi county, Northwest China. Land. Use Policy. 82, 550–562 (2019).

Zhang, K. et al. The ecological conservation redline program: a new model for improving china’s protected area network. Environ. Sci. Policy. 131, 10–13 (2022).

Zhang, W. & Xu, D. Benefits evaluation of ecological restoration projects based on value realization of ecological products. J. Environ. Manage. 352, 120139 (2024).

Leslie, H. M. et al. Operationalizing the social-ecological systems framework to assess sustainability. The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 5979–5984 (2015).

Lazzari, N., Becerro, M. A., Sanabria-Fernandez, J. A. & Martín-López, B. Spatial characterization of coastal marine social-ecological systems: insights for integrated management. Environ. Sci. Policy. 92, 56–65 (2019).

Chakraborty, S., Gasparatos, A. & Blasiak, R. Multiple values for the management and sustainable use of coastal and marine ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 41, 101047 (2020).

Le Roy, M., Sawtschuk, J., Bioret, F. & Gallet, S. Toward a social-ecological approach to ecological restoration: a look back at three decades of maritime clifftop restoration. Restor. Ecol. 27, 228–238 (2019).

Virapongse, A. et al. A social-ecological systems approach for environmental management. J. Environ. Manage. 178, 83–91 (2016).

Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 325, 419–422 (2009).

Partelow, S. A review of the social-ecological systems framework applications, methods, modifications, and challenges. Ecol. Soc. 23, 36 (2018).

Chakraborty, S. et al. Systematizing ecosystem change in coastal social-ecological systems: perspectives from a multi-stakeholder approach in Nakatsu mudflat, Japan. Ocean. Coast Manage. 243, 106729 (2023).

Qiu, L. et al. Chronosequential changes in soil-related ecosystem services after coastal reclamation: insights for coastal cropland protection. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 363, 108877 (2024).

Murray, N. J. et al. The global distribution and trajectory of tidal flats. Nature 565, 222–225 (2019).

Chakraborty, S. & Gasparatos, A. Community values and traditional knowledge for coastal ecosystem services management in the Satoumi seascape of Himeshima island, Japan. Ecosyst. Serv. 37, 100940 (2019).

Murray, N. J. et al. High-resolution mapping of losses and gains of earth’s tidal wetlands. Science 376, 744–749 (2022).

Ju, H. et al. Spatiotemporal patterns and modifiable areal unit problems of the landscape ecological risk in coastal areas: A case study of the Shandong peninsula, China. J. Clean. Prod. 310, 127522 (2021).

Qiu, L. et al. Economic and ecological trade-offs of coastal reclamation in the Hangzhou bay, China. Ecol. Indic. 125, 107477 (2021).

Gari, S. R., Newton, A. & Icely, J. D. A review of the application and evolution of the DPSIR framework with an emphasis on coastal social-ecological systems. Ocean. Coast Manage. 103, 63–77 (2015).

Martín-López, B. et al. Delineating boundaries of social-ecological systems for landscape planning: A comprehensive Spatial approach. Land. Use Policy. 66, 90–104 (2017).

Liu, J. G., Cui, W. H., Tian, Z. & Jia, J. L. Theory of Stepwise ecological restoration. Chin. Sci. Bulletin-Chinese. 66, 1014–1025 (2021).

Baker, S. & Eckerberg, K. Ecological restoration success: a policy analysis Understanding. Restor. Ecol. 24, 284–290 (2016).

Assis, J. et al. Bio-ORACLE v3.0. Pushing marine data layers to the CMIP6 Earth system models of climate change research. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 33, e13813 (2024).

Ward, J. H. Jr Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 58, 236–244 (1963).

Fischer, J., Riechers, M., Loos, J., Martin-Lopez, B. & Temperton, V. M. Making the UN decade on ecosystem restoration a social-ecological endeavour. Trends Ecol. Evol. 36, 20–28 (2021).

Nilsson, C. et al. Evaluating the process of ecological restoration. Ecol. Soc. 21, 41 (2016).

Lu, W., Xu, C., Wu, J. & Cheng, S. Ecological effect assessment based on the DPSIR model of a polluted urban river during restoration: A case study of the Nanfei river, China. Ecol. Indic. 96, 146–152 (2019).

Chen, H. et al. New insights into the DPSIR model: revealing the dynamic feedback mechanism and efficiency of ecological civilization construction in China. J. Clean. Prod. 348, 131377 (2022).

Funding

This research was funded by the Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China [22YJC630110].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Y.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing- Original draft preparationX.Z.: Visualization, InvestigationK.W.: SupervisionL.Q.: Funding acquisition, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, Z., Zhao, X., Wang, K. et al. Spatial characterisation of social-ecological systems for ecological restoration along the coast cities of Zhejiang, China. Sci Rep 15, 30156 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16182-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16182-3