Abstract

The need for green innovation in the high-tech industry has become a critical path to sustainable economic development. However, evaluating green innovation efficiency (GIE) and its spatial characteristics within China’s high-tech industry remains underexplored. This study uses the three-stage undesirable SBM model to assess GIE in China’s high-tech industry from 2006 to 2022. Various spatial analysis methods, including the Theil index, Moran index, Standard Deviation Ellipse, Spatial Markov Chain, and β-convergence model, are applied to examine spatial differences, clustering patterns, and convergence trends of GIE across eight economic regions in China. The model adjusts input indicators to incorporate technological and environmental factors, providing a deeper understanding of the relationship between GIE and regional dynamics. The quantitative results show an increase in GIE from 0.350 to 0.566, with technological and environmental factors playing a significant role. The study highlights increasing spatial disparities in GIE, with the Northern Coastal Region achieving the highest levels. Spatial clustering analysis reveals distinct patterns: the Southern Coastal Region shows High-High clustering, while the Northeast Region exhibits Low-Low clustering. GIE demonstrates club convergence, β-convergence, and spatial spillover effects. These findings underscore the effectiveness of green innovation practices and offer insights into spatial dynamics, providing guidance for targeted interventions and promoting inclusive growth across regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Green innovation is a top priority in today’s industrial landscape, particularly high-tech industries. Given the global sustainability challenges and the urgent need for environmentally conscious economic development, evaluating the high-tech industry’s green innovation efficiency (GIE) has become crucial1,2. China, a key player in the global technological arena, is well-positioned to leverage its high-tech industry for economic growth and environmental protection3,4. However, achieving this dual goal requires a thorough understanding of how effective green innovation practices are within the country’s high-tech industry.

Previous research has extensively explored various aspects of innovation, including technological advancements and industrial competitiveness. However, the specific examination of GIE within the context of China’s high-tech industry, especially considering spatial characteristics, still needs to be explored. Therefore, our study fills this disparity by providing a comprehensive analysis that evaluates the GIE and delineates its spatial dynamics, offering valuable insights for policymakers, industry practitioners, and researchers. To measure GIE, we utilize a three-stage undesirable Slacks Based Measure (SBM) model. This model is particularly suited for evaluating the interplay between undesirable outputs like pollution and waste and desirable outputs like innovation and economic growth5,6. It allows for a dynamic efficiency assessment while accounting for these competing factors. Moreover, incorporating spatial analysis techniques allows for a more nuanced understanding of regional disparities and clustering effects, crucial for devising targeted interventions and fostering inclusive growth across diverse geographic contexts.

Literature review

Significant investments in research and development define the high-tech industry, the production of high-value-added outputs, and a strong strategic focus on innovation7,8. This sector faces increasing pressure to integrate sustainability imperatives due to rising environmental concerns. In this context, GIE has emerged as a critical paradigm, representing the sector’s capacity to generate environmentally sustainable innovations while optimizing resource allocation and minimizing negative ecological impacts3,9. GIE transcends firm-level environmental performance, encompassing systemic impacts across the entire value chain. It drives advancements in resource efficiency, pollution reduction, and low-carbon transitions while maintaining economic growth and technological progress10,11. This synergy enhances resilience to regulatory shifts, market volatilities, and growing consumer demand for eco-friendly products and services12.

Current methodologies for evaluating GIE predominantly rely on parametric approaches like Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA) or nonparametric techniques such as Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA). SFA typically quantifies inputs such as research and development, labor, and capital against desirable outputs like patents and new product revenue5,13. However, a critical limitation of this method is its neglect of undesirable outputs, including pollutants like carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide emissions14,15. While the DEA addresses this by explicitly incorporating pollutants as undesirable outputs, three significant limitations undermine the validity of prevailing assessments. First, conventional input frameworks remain oversimplified. Standard inputs such as research and development expenditure and personnel counts fail to account for technological environmental heterogeneity, specifically variations in capabilities related to technology absorption, adaptation, and support16. Second, standard DEA models exhibit statistical noise ignorance. They conflate genuine managerial inefficiency with the influence of exogenous environmental variables and statistical artifacts, leading to distorted efficiency estimates17. Third, these methods display spatiotemporal blindness. Existing research inadequately addresses the geographical interdependencies, agglomeration dynamics, and regional convergence trends inherent in GIE, essential factors for effective policy formulation in heterogeneous economies14.

While the spatial dimensions of innovation, including knowledge spillovers and regional clustering, are theoretically acknowledged, empirical studies of GIE remain predominantly aspatial and static18,19,20,21. Critical questions persist regarding the drivers of regional GIE disparities, the stability and directionality of spatial agglomeration patterns over time, and the convergence mechanisms across different developmental tiers. This substantial gap obstructs evidence-based policy development tailored to subnational industrial ecosystems and hinders understanding of GIE evolution across regions.

To resolve these deficiencies, our research introduces an integrated tripartite analytical framework. First, it advances efficiency modeling using a three-stage output SBM model. This approach removes the distorting effects of environmental variables and statistical noise from efficiency estimates. It also rectifies oversimplified input structures by integrating technology assimilation capacity, specifically absorption, learning, transformation, and support capabilities, directly into the model. Second, the study provides a comprehensive spatiotemporal analysis of GIE. It pioneers multidimensional spatial analysis employing Theil decomposition for inequality measurement, Moran’s I for spatial autocorrelation, Standard Deviation Ellipse for directional trends, Spatial Markov Chains for transition dynamics, and Beta convergence models for long-run equilibrium analysis. This suite of techniques addresses the field’s fragmented spatial methodology, offering insights into geographical distribution, diffusion trajectories, and dynamic equilibrium. Third, the research provides critical context by focusing on China’s high-tech sector. China’s global manufacturing role and regional inequalities make it paramount, yet its GIE spatial dynamics remain significantly underexamined. This focus yields detailed insights into how spatial factors and institutional frameworks shape GIE evolution, advancing theoretical discourse on sustainable industrial transition within emerging economies.

Materials and methods

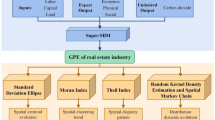

We propose a comprehensive research framework for evaluating the GIE of China’s high-tech industry and analyzing their spatial characteristics (Fig. 1). Beginning with defining GIE in the high-tech industry, this study selects input-output indicators and technological environmental variables, employing the three-stage undesirable SBM model for calculation. The Theil index is used to analyze the spatial differentiation characteristics of GIE, while the Moran index and Standard Deviation Ellipse are utilized to analyze the spatial clustering features. Additionally, the Spatial Markov Chain and β-convergence model are applied to analyze the spatial convergence characteristics.

Variable selection

The selection of variables for measuring GIE in the high-tech industry requires a robust theoretical foundation. Input variables must capture essential resources driving innovation and the green transition. Key input dimensions include research institutions, personnel, funding, and transformation resources. Output variables should reflect multiple innovation outcomes, including technological achievements, economic benefits, and environmental consequences. This captures both desirable and undesirable results of innovation2,7. The technological environment significantly shapes innovation effectiveness5,6. Variables representing technological importation, learning, transformation, and support are therefore critical. These capture external and internal mechanisms enabling an industry’s innovation capacity and shift toward sustainable practices, summarized in Table 1.

Input variable

The count of research and development institutions measures the number of research institutions. These institutions are fundamental to technological and scientific progress22. This count quantifies the availability of specialized resources, knowledge infrastructure, and potential collaboration opportunities within the high-tech sector. R&D institutions serve as central hubs for cutting-edge research, advancing green technologies through partnerships across academia, government, and industry. Their regional or sectoral density directly indicates innovation capacity, particularly in domains critical for green transitions like energy efficiency and pollution control. Consequently, the R&D institution count is vital for assessing resources committed to green innovation.

The full-time equivalent of R&D personnel measures research personnel input. Human capital critically drives technological innovation23. This metric quantifies the workforce dedicated to research, reflecting human resource intensity in innovation. Skilled personnel are indispensable for translating concepts into viable green technologies. Quantifying the R&D workforce signifies available labor capacity to propel innovation and directly builds the knowledge base essential for high GIE. Greater R&D personnel concentration increases the potential for significant green technological breakthroughs.

R&D expenditure represents research funding. Financial resources allocated to R&D are paramount for sustaining innovation24. This expenditure quantifies financial support accessible to the high-tech industry for research, testing ideas, and developing green technologies. Investment levels signal public and private sector commitment to innovation, particularly in environmentally sustainable technologies. Higher R&D expenditure typically correlates with enhanced capacity for breakthrough green innovations. This funding underpins creating energy-efficient products, environmentally friendly production methods, and sustainable solutions, substantially influencing overall GIE.

Expenditure on new product development measures transformation funding. This funding, directly linked to commercializing innovations, represents resources directed toward converting research outputs into market-ready, environmentally sustainable products25. The high-tech industry requires significant investment not only in research but also in scaling and commercializing green innovations. This expenditure ensures research breakthroughs become sustainable solutions adopted by industries and consumers. It reflects the critical capacity to translate theoretical knowledge into tangible applications, necessary for achieving high GIE.

Output variable

The number of effective invention patents measures technological achievement. This achievement is a primary indicator of innovation success and impact in the high-tech sector26. The count of effective invention patents represents technological progress, as patents attest to the novelty and originality of inventions. The volume of in-force patents directly connects to developing new green technologies that enhance industrial sustainability. Patents provide formal recognition of innovation; their quantity reflects creative output and the market Significance of environmentally sustainable technologies. A higher number of effective invention patents signifies substantial technological advancement, a core green innovation output indicating successful conversion of research into valuable assets.

Sales revenue from new products measures economic benefit. This revenue quantifies the economic impact of green innovations and directly reflects market acceptance and commercial viability27. New product launches, especially environmentally sustainable ones, are major economic outputs in high-tech industries. They signal adoption by industries and broader markets. Sales revenue indicates economic growth and demonstrates proficiency in commercializing innovations. This variable is essential for evaluating financial returns on R&D investments and highlights how efficiently innovations yield sustainable economic benefits. Linking revenue to green products precisely assesses their contribution to profitability and growth.

An environmental pollution index weighted by emissions, carbon dioxide, chemical oxygen demand, ammonia nitrogen, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter quantifies environmental pollution9. Pollution is a non-desirable output, as high-tech industries generate negative environmental externalities despite progress. This index comprehensively measures industrial environmental impact through aggregated emissions. Including it explicitly acknowledges the trade-off between innovation and environmental degradation when balancing technological development with ecological sustainability. Industrial processes may still produce harmful emissions even as green innovations target pollution reduction. Measuring pollution is therefore essential for evaluating detrimental industrial byproducts and determining whether innovations genuinely advance environmental sustainability. Reducing pollution while enhancing technological and economic outputs defines the core challenge in assessing GIE.

Technological environment variable

Expenditure on technology introduction measures technological importation. This importation means spending to acquire foreign technologies, substantially augmenting national or industrial innovation capacity28. Such expenditure is vital for accessing advanced technologies, particularly in environmental sustainability. Importing foreign technologies enables industries to bypass traditional development and adopt more efficient, environmentally friendly solutions more quickly, thereby accelerating green innovation. Investment helps firms overcome knowledge deficits, adopt international best practices, and shorten internal R&D timeframes, leading to faster gains in GIE. Expenditure on technology introduction is therefore a key environmental factor for green innovation inputs.

Expenditure on digestion and absorption measures technological learning. This learning means how firms internalize, adapt, and enhance externally acquired technologies29. Such expenditure critically assesses how effectively high-tech industries adapt imported technologies to their contexts and innovate upon them. While importation provides immediate access, effective assimilation and modification are paramount for long-term success with green technologies. This spending reflects investments in human capital, training, and processes that maximize the absorption of foreign technologies. Strengthening learning capabilities improves firms’ ability to innovate and implement sustainable practices, making this variable essential for GIE.

Expenditure on technological transformation measures this process. Technological transformation converts new technologies or ideas into practical, scalable solutions30. This expenditure signifies resources allocated to turning research outputs, imported technologies, or novel ideas into operational, market-ready products. It ensures green innovations move beyond theory into production systems, advancing environmental sustainability. Achieving transformation often requires substantial investment in infrastructure, equipment upgrades, and organizational restructuring for new, greener technologies. This spending signals the industry’s dedication to converting innovation into tangible outcomes, aligning with economic and environmental objectives. Technological transformation expenditure is thus a key environmental factor influencing green innovation inputs that drive high-tech industry efficiency.

The number of high-tech enterprises measures technological support. This count reflects the prevalence of firms capable of advanced research and innovative technology adoption31. High-tech enterprises possess the infrastructure, expertise, and market orientation to drive technological innovation, including green technology development and deployment. A significant concentration creates a knowledge-sharing ecosystem, fostering collaborative ventures and competitive dynamics that enable green innovation. These firms pioneer emerging technologies and invest more readily in sustainable solutions. Therefore, their number constitutes an important environmental factor influencing the scale and scope of green innovation inputs. A larger population enhances collective innovation capacity, improving GIE.

Data source

The relevant data, delineated in Table 1, are sourced from the China Statistical Yearbook on Science and Technology (CSYST, 2007–2023), the China Statistical Yearbook on Environment (CSYE, 2007–2023), and the CEADs database (CEAD, www.ceads.net), by the specific variables considered.

Study area

The specific regional divisions are illustrated in Fig. 2. This study covers 30 provinces in China. Due to data availability constraints, the sample excludes Tibet, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau. The study encompassed 30 provinces in China, excluding Tibet, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macao. The Northeast Region comprises Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang. The Northern Coastal Region includes Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, and Shandong. The Eastern Coastal Region comprises Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang. The Southern Coastal Region includes Fujian, Guangdong, and Hainan. The Yellow River Middle Region includes Shaanxi, Shanxi, Henan, and Inner Mongolia. The Yangtze River Middle Region comprises Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, and Anhui. The Southwest Region includes Yunnan, Guizhou, Sichuan, Chongqing, and Guangxi. The Northwest Region includes Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Tibet, and Xinjiang.

The GIE of the high-tech industry is measured using the three-stage undesirable SBM model. In the first stage, the undesirable SBM model is used to measure the GIE of the high-tech industry without considering technological environmental factors while also obtaining the slack variables of the input indicators. In the second stage, a similar SFA model is applied to adjust the slack variables of the input indicators based on technological environmental factors. In the third stage, the undesirable SBM model is used again, incorporating the adjusted input indicators to measure the GIE of the high-tech industry while accounting for technological environmental factors. The key advantage of the three-stage undesirable SBM model lies in its ability to consider the impact of technological environmental factors on GIE, making the measurement results more accurately reflect the technological innovation characteristics of the high-tech industry3,5.

The three-stage undesirable SBM model consists of three components: the traditional undesirable SBM stage, the analogous SFA stage, and the adjusted undesirable SBM stage32,33. GIEi represents the GIE of the high-tech industry in the i-th (i = 1,3) stage. The settings for each stage of the model are outlined below.

Define the production possibility set \(P({\mathbf{x}},{\mathbf{y}}^{e} ,{\mathbf{y}}^{u} )\)

Where λ represents the weight vector, w− represents the input slack variable, we signify the desirable output slack variable, and wu denotes the undesirable output slack variable. The formula for calculating GIE in the high-tech industry based on input orientation is as follows:

An analogous SFA model mitigates the impact of environmental factors and random factors on input variables in the high-tech industry, where z represents the set of environmental factor variables. Adjusting input variables entails adjusting input slack variables, where environmental factors are considered independent variables and input slack variables are considered dependent variables in regression analysis.

In Eq. (3), the stochastic factors \(v_{i}\) and managerial inefficiency \(u_{i}\) are mutually independent, independently, and identically distributed as \(N(0,\sigma_{v}^{2} )\) and \(N(0,\sigma_{u}^{2} )\), respectively. Let \(\sigma^{{2}} = \sigma_{v}^{2} + \sigma_{u}^{2}\) and \(\gamma = {{\sigma_{u}^{2} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\sigma_{u}^{2} } {\sigma^{{2}} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\sigma^{{2}} }}\) denote the variables. A value of \(\gamma\) close to 1 indicates that managerial inefficiency predominantly influences input slack, whereas a value of \(\gamma\) close to 0 suggests that stochastic factors predominantly affect input slack.

By substituting the input vector x with the adjusted vector x* in Eq. (2), we can calculate the adjusted GIE of the high-tech industry.

Theil index

We use the Theil index to assess the disparity in GIE within China’s high-tech industry and analyze this variation across eight economic regions. The Theil index, a standard measure of inequality, is particularly suitable for evaluating GIE disparity because it decomposes total inequality into within-group and between-group components. This decomposition provides insights into whether intra-regional or inter-regional differences primarily drive the disparity18. The choice of the Theil index is based on its ability to handle varying inequality levels across subgroups, offering a comprehensive view of GIE distribution. It accounts for the extent of disparity and the relative contribution of each region to the overall inequality, allowing for a detailed analysis of how different regions contribute to the national GIE disparity34.

T represents the total disparity nationwide, where Tb and Tw denote the between-region disparity and within-region disparity within the eight economic regions, respectively, while Tk signifies the disparity within the k-th economic region34.

Where n represents the total number of provinces, K represents the number of delineated economic regions, and nk denotes the number of provinces within the k-th (\(k = 1,2, \cdot \cdot \cdot ,K\)) economic region; \(GIE_{i}\) represents the GIE of the i-th (\(i = 1,2, \cdot \cdot \cdot ,n\)) province, \(\overline{GIE}\) represents the average GIE of all provinces, \(GIE_{ki}\) represents the GIE of the i-th province within the k-th economic region, and \(\overline{{GIE_{k} }}\) represents the average GIE of all provinces within the k-th economic region.

Moran index

We use the Moran index to examine the spatial clustering characteristics of GIE in China’s high-tech industry. The Moran index is a widely used spatial statistic that measures spatial dependence, allowing us to assess the extent to which similar values cluster geographically14. This clustering reveals patterns of how GIE is distributed across regions. China’s high-tech industry shows significant spatial heterogeneity, with regional variations in technological capabilities, resource allocation, policy environments, and industrial development leading to uneven green innovation outcomes. By applying the Moran index, we can identify whether regions with high or low GIE values tend to cluster or if there is a random distribution. This information is crucial for policymakers to pinpoint areas where regional green innovation efforts complement or hinder one another.

The global Moran index is employed to test the overall spatial clustering effect.

Where s2 represents the variance of GIE across all provinces, and wij denotes the inverse distance spatial weights calculated using latitude and longitude data. Utilizing the local Moran index, we conduct a test for local spatial clustering effects, where the local Moran index for the i-th province is provided in Eq. (11). Combining the local Moran index enables the construction of LISA cluster maps.

Standard deviation ellipse

We use the Standard Deviation Ellipse (SDE) to illustrate the clustering center and range of GIE in China’s high-tech industry. The SDE provides a geometric representation of the spatial dispersion of GIE across regions, showing the extent to which GIE values deviate from the mean in both horizontal and vertical directions. The ellipse’s center corresponds to the mean GIE, serving as a reference for the central tendency. The ellipse’s orientation indicates the direction of GIE concentration, highlighting areas with higher or lower innovation efficiency. The axes represent the standard deviations in two dimensions, with the longer axis reflecting a greater spread of GIE and the shorter axis suggesting more uniformity in the data distribution14. This approach aids in understanding the geographical range of GIE performance within the high-tech industry.

Representing the geographical coordinates of the i-th province as \((x_{i} ,y_{i} )\), the geographical centroid of GIE in China’s high-tech industry is also denoted by \((x_{GIE} ,y_{GIE} )\).

Calculate the length of the significant semi-axis (standard deviation along the x-axis) and the minor semi-axis (standard deviation along the y-axis) of the SDE. Use \((\tilde{x}_{i} ,\tilde{y}_{i} )\) (\(\tilde{x}_{i} = x_{i} - x_{GIE}\), \(\tilde{y}_{i} = y_{i} - y_{GIE}\)) to represent the relative coordinates of the i-th province concerning the centroid position. Let

Finally, the standard deviations along the x-axis and the y-axis are obtained.

Spatial Markov chain

Using spatial Markov chain (SMC) to illustrate the dynamic transition trends and convergence characteristics of GIE in China’s high-tech industry. Spatial Markov chains allow for the examination of spatial dependencies by considering how regions’ GIE levels are influenced by their characteristics and those of neighboring regions. This is crucial for understanding the regional diffusion of green technologies and innovation practices within the high-tech industry. Markov chain effectively analyzes dynamic transitions by modeling the probabilistic movement of regions between different GIE states over time. The SMC model accounts for shifts in GIE states due to policy interventions, technological advancements, and regional economic changes. Using SMC, we can track the likelihood of these transitions and identify patterns of progress or stagnation in regional GIE performance, providing a comprehensive view of its dynamic behavior19.

Classifying GIE in high-tech industry into L types, where \(n_{i}^{t}\) represents the number of provinces belonging to type i in year t, and \(n_{ij}^{t,t + T}\) represents the number of provinces belonging to type i in year t and transitioning to type j after T years, the state transition probability of high-tech industry GIE shifting from type i in year t to type j in year t + T nationwide is as follows.

Based on Eq. (14), incorporating the lagged term of GIE, we ultimately derive the \(L \times L \times L\) order SMC.

β-Convergence model

The β-convergence model is used to analyze the dynamic convergence trends of GIE in China’s high-tech industry. It helps determine whether GIE in different provinces is converging. If regions with lower initial GIE values experience faster growth, the β-convergence model suggests a reduction in spatial disparities, indicating a trend toward more efficient GIE over time35. Identifying β-convergence in China’s high-tech industry provides insights for policymakers, helping assess the effectiveness of strategies like green innovation promotion and sustainable development policies in narrowing regional gaps in GIE and supporting sustainable growth. The model allows for regional comparisons, serving as a benchmark to evaluate the impact of local environmental and innovation policies on GIE enhancement. Analyzing convergence trends can also reveal whether lagging areas are catching up with leading regions, potentially signaling successful innovation diffusion and policy interventions2.

Formulating a panel data model as follows:

In Eq. (15), β represents the convergence coefficient, where β < 0 indicates that the GIE of the high-tech industry is converging, with the corresponding convergence rate denoted by \(\phi = - \ln (1 + \beta )\). Conversely, β > 0 signifies a divergent state of GIE in the high-tech industry, while β = 0 denotes a state of relative equilibrium in GIE. The study employs a quantile regression method with temporal and spatial fixed effects for estimation to validate dynamic convergence trends across different efficiency levels.

Results

Calculation results of GIE in china’s high-tech industry

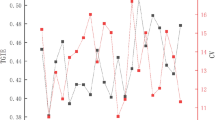

Comparing the GIE of the high-tech industry between the first and third phases reveals a significant improvement after incorporating the influence of the technological environment. At the national level, during the observation period, the GIE in phase one ranged between 0.138 and 0.350, while in phase three, it ranged between 0.290 and 0.566 (Fig. 3). The efficiency in phase three was notably higher than in phase one, indicating that the technological environment significantly enhances the GIE of the high-tech industry. At the level of eight economic regions, under the influence of the technological environment, the GIE in the Northeast Region, Northern Coastal Region, Eastern Coastal Region, Southern Coastal Region, Yellow River Middle Region, Yangtze River Middle Region, Southwest Region, and Northwest Region increased from 0.066, 0.402, 0.523, 0.423, 0.154, 0.171, 0.096, and 0.009 in the first phase to 0.322, 0.616, 0.555, 0.577, 0.386, 0.356, 0.436, and 0.378 in the third phase, respectively (Fig. 4). Comparatively, the impact of technological environmental factors was more pronounced in the Northwest Region, Northeast Region, and Southwest Region, while weaker in the Eastern Coastal Region, Southern Coastal Region, and Northern Coastal Region. From 2006 to 2022, China’s high-tech industry exhibited strong growth momentum in GIE. At the national level, the average annual growth rates of GIE in the first and third phases were 4.16% and 4.53%, respectively (Fig. 3). This indicates a growth trend in GIE regardless of technological environmental factors. The higher growth rate in the third phase compared to the first phase suggests that technological environmental factors can facilitate the growth of GIE in the high-tech industry. Focusing on the changes in GIE in the eight economic regions in the third phase, the Northwest Region, Yangtze River Middle Region, Eastern Coastal Region, and Yellow River Middle Region experienced rapid growth, with average annual growth rates exceeding 10%. At the same time, the Northern Coastal Region exhibited the slowest growth rate, with a growth rate of less than 1%.

This analysis examines the impact of technological environmental variables on input relaxation (Table 2). Based on four models, the regression results assess the effect of technological factors (technological importation, learning, transformation, and support) on four key input indicators (research institutions, research personnel, research funding, and transformation funding). All four models pass the LR test at the 1% significance level, confirming the robustness of the results. The coefficient η, representing the time-varying impact of the technological environment, is significantly positive in all models, indicating that the influence of the technological environment on GIE strengthens over time. The γ coefficients measure the extent to which technological variables influence input relaxation, with impacts of 85.0%, 90.7%, 95.1%, and 97.4% on the relaxation of research institutions, research personnel, research funding, and transformation funding, respectively. This suggests that the technological environment affects GIE by altering input indicators. Specifically, technological importation, learning, and transformation positively impact the reduction of resources in research institutions, research personnel, and transformation funding. Technological support shows mixed results. It reduces the need for research personnel and transformation funding but paradoxically increases research institutions and funding inputs. These findings suggest that policymakers can enhance GIE by promoting technological learning and support to optimize resource allocation in key sectors such as research institutions and funding. Technological importation and transformation also provide pathways to boost GIE by reducing reliance on physical inputs and fostering a more sustainable innovation ecosystem.

Spatial differentiation characteristics of GIE in china’s High-Tech industry

The spatial disparities in GIE in China’s high-tech industry are narrowing. The Theil index at the national level decreased from 0.488 in 2006 to 0.096 in 2022, with an average annual decline rate of 9.7% (Fig. 5). This result indicates that significant inter-provincial differences in GIE in China’s high-tech industry gradually diminish. Since 2012, China has been vigorously implementing the strategy of regional coordinated development, promoting the implementation of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei coordinated development strategy and the Yangtze River Economic Belt innovation development strategy, gradually forming vertical and horizontal economic axes dominated by coastal and along-the-river economic belts. Decomposing the overall differences from the perspective of the eight economic regions, the contribution rates of inter-regional differences among the eight economic regions range from 6.04 to 58.74%, with an average of 27.70%. In contrast, intra-regional differences within the eight economic regions are the primary source of overall differences.

Further investigation was conducted into spatial disparities in GIE within each economic region (Fig. 5). Throughout the entire study period, the mean Theil index was highest in the Northwest Region at 0.210, followed by the Yellow River Middle Region, Southern Coastal Region, Northern Coastal Region, Southwest Region, Northeast Region, and Eastern Coastal Region, with the lowest Theil index observed in the Yangtze River Middle Region at 0.035. These results indicate that the differences in GIE among provinces within the Northwest Region are the largest, while they are the smallest within the Yangtze River Middle Region. Regarding the temporal evolution trends of Theil indices within each economic region, the internal differences in the Northeast, Northern Coastal, Yellow River Middle, and Southwest regions show a declining trend. The internal differences in the Eastern Coastal Region and Southern Coastal Region exhibit an inverted U-shaped trend, initially rising and then declining, while those in the Yangtze River Middle Region and Northwest Region demonstrate a U-shaped trend, initially declining and then rising. Therefore, effectively controlling the regional disparities in GIE within the Northwest Region is urgent and essential. Comparing the contribution rates of internal differences among the eight economic regions, the contribution rate is highest in the Northern Coastal Region and lowest in the Yangtze River Middle Region, with average contribution rates of 16.10% and 1.86%, respectively. The contribution rate in the Northeast Region decreased from 12.18% in 2006 to 0.49% in 2022. The contribution rates in the Eastern Coastal Region, Southwest Region, Northwest Region, Yellow River Middle Region, and Southern Coastal Region are approximately 5.00%, 10.40%, 10.98%, 12.39%, and 12.51%, respectively.

Spatial agglomeration characteristics of GIE in china’s high-tech industry

From 2006 to 2022, the Moran index passed the significance test at the 5% level and displayed positive values, indicating a spatial positive clustering of GIE (Fig. 6). The Moran index fluctuated between 0.217 and 0.574 throughout the study period, averaging 0.412. This suggests a significant spatial radiation effect of GIE in the high-tech industry, wherein a 1% increase in local efficiency corresponded to an average increase of 0.412% in neighboring areas. Over time, the Moran index grew, particularly after 2019, when it exceeded 0.5, indicating an increasingly pronounced spatial clustering trend in GIE in China’s high-tech industry. Analysis of the LISA cluster map for GIE in China’s high-tech industry led to the following conclusions: High-High and Low-Low clustering are the primary trends in local GIE, with the number of provinces exhibiting High-High and Low-Low clustering increasing over time. Looking at specific regions, the Southern Coastal Region primarily exhibits High-High clustering. In contrast, the Northeast, Yellow River Middle, Southwest, and Northwest Region primarily exhibit Low-Low clustering. The Northern Coastal Region mainly shows Low-High clustering, while the Eastern Coastal Region and Yangtze River Middle Region mainly exhibit High-Low clustering. The reasons for these phenomena are twofold: Firstly, the improvement of GIE in the high-tech industry is inseparable from local solid policy support and reduced financial costs, achieved through increased innovation capacity and technological equipment innovation. Secondly, the high-tech industry possesses spatial solid spillover effects, as high-level provinces can provide technical support and management experience to adjacent low-level provinces, thereby driving up GIE in the high-tech industry in neighboring provinces.

The trajectory of the standard deviation ellipse centroid reveals the shifting geographic centroid of high-tech industry GIE in China over the years (Fig. 7). It moved from Yuncheng City, Shanxi Province, in a southeast direction to Nanyang City, Henan Province, covering a distance of 207.48 km between 2006 and 2010. Subsequently, from 2010 to 2014, the centroid shifted northeastward by 131.18 km to Pingdingshan City, Henan Province. From 2014 to 2018, it moved southeastward by 145.77 km to Xiangyang City, Hubei Province. Finally, between 2018 and 2022, it shifted northeastward again by 181.14 km to Zhumadian City, Hubei Province. Overall, the centroid of the high-tech industry GIE clustering in China exhibited a southeastward movement. Examining the evolution of the standard deviation ellipse contour, we consistently observed the significant axis oriented in the east-west direction throughout the study period. This suggests that the disparity in GIE between the east and west regions was more significant than that between the north and south. The short and long semi-axes of the ellipse for the years 2006, 2010, 2014, 2018, and 2022 were (659.25 km, 1237.84 km), (556.92 km, 1111.61 km), (531.84 km, 762.59 km), (464.75 km, 508.33 km), and (453.71 km, 454.47 km), respectively. This indicates a gradual reduction in spatial disparities in GIE, with the east-west disparity narrowing more rapidly. By 2022, the standard deviation ellipse had nearly become circular, signaling a more balanced distribution of high-tech industry GIE nationwide.

Spatial convergence characteristics of GIE in china’s high-tech industry

Following the quartile principle, we categorize the GIE of the high-tech industry in 30 provinces during the study period into four types: low, medium-low, medium-high, and high (Table 3). Disregarding spatial spillover effects of GIE, most of the main diagonal elements in the state transition probability matrix are more significant than other elements, indicating the presence of club convergence in China’s high-tech industry GIE. For instance, over one year, if a region’s GIE of high-tech industry is of a particular type in a given year, the probability that it remains the same type after one year ranges from 41.1 to 60.2%, highlighting the strong persistence of GIE in high-tech industry. Low and high probabilities exceed 50%, suggesting a tendency for polarization in GIE within the high-tech industry, known as the Matthew Effect. Most non-zero elements in the matrix are distributed on both sides of the main diagonal, indicating that transitions between different types mainly occur between adjacent levels. Specifically, transitions are more likely between medium-low and low levels and between medium-high and high levels. As the span period increases, this transition trend becomes more pronounced, suggesting a polarization trend between high and low levels of GIE in China’s high-tech industry. For instance, when extending the span period from one year to five years, the probabilities of maintaining the status of low, medium-low, medium-high, and high decrease from 60.2%, 41.1%, 53.0%, and 52.8–53.1%, 32.1%, 41.0%, and 46.0%, respectively, with the transition trend of the medium-high level being the most apparent. When incorporating spatial lag terms into the traditional Markov state matrix, most elements in the transition probability matrix change, indicating the presence of spatial spillover effects in the transition trends of GIE in China’s high-tech industry. Specifically, the development level of neighboring areas in preceding periods influences the current variation in GIE within a local area. Firstly, regardless of the type of spatial lag term, regions with low-level GIE exhibit consistently more robust stability. Compared to low-level and high-level neighbors, the probability of maintaining a low-level status in the local area is 62.5% and 87.5%, respectively. Adjacency to low-level regions increases the likelihood of remaining in a low-level state, while adjacency to high-level regions increases the likelihood of polarization. Secondly, the monopolistic phenomenon of high-level areas is alleviated by introducing spatial factors, and prolonging the span period impacts the club convergence of high-level areas. When adjacent to low-level areas, the probability of high-level regions maintaining their status is only 37.5%, indicating that high-level regions lack significant developmental advantages and are easily influenced by low-level areas.

The convergence coefficient β in Table 4 are all less than 0 and significant at the 1% level, indicating the presence of β-convergence characteristics in the GIE of China’s high-tech industry. Furthermore, it is observed that the β-convergence speed follows a U-shaped trend across quantiles, initially decreasing and then increasing. The convergence speed steadily declines from 0.492 at the 0.1 quantile to 0.172 at the 0.6 quantile before rising to 0.861 at the 0.9 quantile. This finding suggests that the convergence speed of GIE in the high-tech industry is faster in low-level and high-level regions but slower in moderate-level regions, reaffirming the existence of club convergence and polarization trends between high and low levels in China’s high-tech industry GIE. The sample period is divided into four time intervals: 2006–2010, 2010–2014, 2014–2018, and 2018–2022 (Fig. 8). β-convergence is observed in all four time intervals, with the convergence speed showing a U-shaped trend across quantiles. The convergence speed during 2006–2010 is significantly faster than that during 2010–2014, 2014–2018, and 2018–2022, with mean convergence speeds for the four-time intervals of 0.988, 0.344, 0.239, and 0.343, respectively, indicating a gradual slowdown in convergence speed over time. Employing the framework of technological diffusion, the phenomenon can be understood as an initial phase marked by the rapid dissemination of green innovation, attributable to proximate distances between innovators and adopters, facilitating low-cost information transmission and learning. However, as time progresses, impediments such as technological thresholds, knowledge transfer costs, and institutional constraints gradually impede the pace of diffusion, leading to a slowdown. Viewing through the lens of resource constraints offers insight into where the demands of green innovation necessitate substantial inputs encompassing human capital, financial resources, and technological support. Initially, these resources may be concentrated in locales or enterprises possessing advanced technology or abundant resources, fostering expedited progress in GIE36. However, over time, resources become increasingly scarce, escalating input costs and constraining further advancements in efficiency. The influence of institutional environments on green innovation merits consideration. Institutional environments, including legal frameworks, governmental policies, and industrial strategies, can bolster or impede innovation. Some regions may exhibit conducive institutional environments, propelling green innovation, while others may feature less supportive frameworks, curbing its development37. With time, alterations in institutional environments, whether ameliorative or deleterious, can impact the spatial convergence rate of GIE within the high-tech industry in China.

Discussion

The critical role of the technological environment

Empirical analysis confirms the technological environment as a fundamental determinant of GIE within China’s high-tech industry (Table 2). The elevation of efficiency values in the third stage, compared to the initial stage measured solely by the undesirable SBM model, demonstrates the significant positive impact of accounting for technological environment factors. This methodological progression employs SFA to adjust input indicators for environmental influences before reapplying the undesirable SBM model, effectively isolating and quantifying the environment’s contribution32,33. The findings reveal that technological environment factors significantly enhance GIE primarily by mitigating input redundancies.

Three key mechanisms drive this enhancement. First, technological learning fosters efficiency gains in deploying research institutions, personnel, and funding. The cumulative acquisition of knowledge and refinement of skills enable researchers to utilize resources more strategically, reducing research cycle durations, lowering operational costs, increasing project success probabilities, minimizing research failures, and optimizing funding allocation for both research and technological transformation38. Second, technological importation generates cost savings by facilitating access to and integration of external technological resources. Acquiring advanced technologies externally allows research institutions to circumvent substantial internal research and development expenditures. This accelerates technological progress, improves research efficiency, enhances output quality, and lets researchers focus on core innovation activities rather than foundational development, decreasing redundant investments and optimizing transformation funding39. Third, technological transformation achieves cost savings by updating and deploying existing technologies to address new challenges, thereby avoiding the need for heavy investment in entirely new research and development initiatives. Streamlining workflows and resource utilization allows institutions to focus resources on core research areas and allocate transformation funding flexibly towards the most promising projects, maximizing overall resource utilization40.

The Spatial heterogeneity of GIE

Significant regional disparities in GIE exist across China’s eight major economic regions, stemming from distinct economic structures, geographical constraints, and industrial focuses (Figs. 3 and 5). The Northeast Region exhibits relatively low efficiency with minimal internal variation, linked to historical agricultural specialization, necessitating industrial revitalization through increased research funding. Conversely, the Northern and Eastern Coastal Regions demonstrate higher efficiency with limited internal variation, benefiting from high-tech industries and diversified manufacturing; policy should expand high-tech enterprise networks and amplify sectoral influence. The Northwest Region suffers from low efficiency compounded by significant internal disparity, influenced by geography and environment; development strategies must leverage the Silk Road Economic Belt, enhance international technological cooperation, and promote foreign technology integration. The Yellow River Middle Region displays moderate efficiency but notable internal disparities, requiring targeted technological support and financial backing to reduce inequality. The Yangtze River Middle Region has a strong high-tech base, but it faces uneven development. To address this, policies must focus on rational research fund allocation and enhance technological and environmental infrastructure. The Southwest Region should prioritize elevating efficiency by fostering deep integration between high-tech industries and sectors like tourism. The Southern Coastal Region’s outward-oriented economy requires increased technological investment and export expansion to mitigate internal disparities41,42.

China’s high-tech industry displays pronounced spatial agglomeration of GIE, increasingly concentrated in the southeastern regions (Figs. 6 and 7). This clustering aligns with neoclassical economic principles and the critical mass required for robust innovation ecosystems. Firms strategically locate based on production costs, market accessibility, and co-location benefits. The southeast offers superior talent density, readily available funding, and robust technological infrastructure43. High-tech enterprises benefit significantly from proximity to collaborative networks involving firms and research institutions, particularly under strong environmental awareness and supportive policy frameworks. Key drivers of this southeastern agglomeration include advanced infrastructure facilitating market expansion, high digitalization levels enhancing collaboration, a deep talent pool supported by leading universities, rising consumer demand for eco-friendly products, and a favorable policy environment emphasizing environmental protection. This solidified hub attracts substantial investment, reinforcing industrial clustering44.

Analysis further reveals a convergence trend in GIE across Chinese regions, primarily driven by technological spillovers inherent to the high-tech industry (Table 3; Fig. 8). These spillovers originate from the sector’s advanced technological and knowledge repositories, creating synergistic effects within green innovation processes across industrial chains. High-tech innovations possess high foresight and impact, particularly regarding environmental challenges through new materials, energy sources, and processes. Their diffusion beyond originating firms benefits other industries and regions, fostering convergence. Collaboration among high-tech firms, research institutions, and government agencies promotes vital technology exchange, enhancing industrial chain capabilities. Substantial sectoral innovation investments amplify this synergy, generating powerful technological spillover effects that help bridge regional efficiency disparities. These spillovers transcend geographical boundaries via skilled personnel mobility, integrated supply chains, and patent licensing, driving regional convergence45,46. While disparities persist due to factors such as infrastructure quality and industrial structure, ongoing green innovation advancement and its inherent spillover effects facilitate narrowing these gaps, promoting more equitable technological development and national efficiency alignment47.

Conclusion and suggestion

Conclusion

This study uses the three-stage undesirable SBM model to evaluate the GIE in China’s high-tech industry from 2006 to 2022. It examines the spatial differentiation characteristics of GIE across eight economic regions in China’s high-tech industry using Theil index analysis. Furthermore, Moran’s index and Standard Deviation Ellipse are employed to analyze the spatial clustering trends and evolution of GIE. Spatial Markov Chain and β-convergence model are utilized to analyze the convergence trends and speeds of GIE. The main conclusions drawn are as follows:

-

(1)

The GIE of China’s high-tech industry has increased from 0.350 to 0.566, with varying growth trends observed across economic regions. Technological environmental factors significantly enhance GIE by influencing input indicators in the high-tech industry. Technological learning leads to savings in research institutions, personnel, research funding, and transformation funding inputs. Additionally, technological importation and transformation result in savings in research institutions, research personnel, and transformation funding inputs, while technological support leads to savings in research personnel and transformation funding inputs.

-

(2)

Spatial unevenness is pronounced in the GIE of China’s high-tech industry, with a widening absolute difference between high and low levels, indicating a growing trend of polarization. Relative differences among the eight economic regions constitute the primary source of overall differences. The ranking of GIE across economic regions, from high to low, is as follows: Northern Coastal Region, Southern Coastal Region, Eastern Coastal Region, Southwest Region, Yellow River Middle Region, Northwest Region, Yangtze River Middle Region, and Northeast Region.

-

(3)

Spatial clustering characteristics are observed in the GIE of China’s high-tech industry, with the Southern Coastal Region exhibiting High-High clustering and the Northeast Region, Yellow River Middle Region, Southwest Region, and Northwest Region exhibiting Low-Low clustering. The Northern Coastal Region demonstrates Low-High clustering, while the Eastern Coastal Region and Yangtze River Middle Region exhibit High-Low clustering. The centroid of GIE clusters shifts towards the southeast, with the standard deviation ellipse indicating more significant differences in GIE along the east-west direction than the north-south direction. Over time, spatial differences in GIE along the east-west direction gradually diminish, leading to a balanced distribution of high-tech industry GIE nationwide by 2022.

-

(4)

The GIE of China’s high-tech industry exhibits club convergence and β-convergence characteristics. Transfers of GIE predominantly occur between adjacent levels among different provinces, with transfer trends becoming increasingly apparent over time. Convergence rates are faster between high and low levels but slow down with time. Additionally, there are spatial spillover effects in the transfer trends of GIE, with the development advantages of high-level regions being constrained by neighboring low-level regions. Regardless of the level of adjacency, regions with lower levels exhibit consistently more robust stability.

Suggestion

Based on the findings of this study, the following recommendations are proposed to promote the green and sustainable development of high-tech industry and foster cross-regional collaboration:

-

(1)

Strengthen technological environmental factors. Enhance the role of technological factors, such as technological learning, technology adoption, and support, which significantly influence GIE. Governments should prioritize increasing R&D funding mechanisms at national and regional levels to support the development of advanced technologies that improve production efficiency and reduce environmental impact. Policies should incentivize private sector investment in green technologies and provide subsidies for cleaner, more efficient production processes.

-

(2)

Promote regional coordinated development. The spatial imbalance in GIE, particularly between the eastern and underdeveloped central, western, and northeastern regions, requires targeted interventions. Policies should focus on improving infrastructure and technological capabilities in these regions. For instance, the government could establish innovation hubs and offer tax incentives to attract high-tech industry. Public-private partnerships for regional development projects can help bridge technological gaps and enhance industry competitiveness.

-

(3)

Support industrial agglomeration. Given the spatial clustering of high-tech industries, enhancing industrial agglomeration is vital to promoting synergies and economies of scale. The government should support the development of industrial clusters by improving innovation ecosystems, such as providing access to shared R&D facilities, fostering collaboration between businesses, universities, and research institutions, and encouraging venture capital investment. Special economic zones with policies favorable to green industries could also attract leading high-tech companies.

-

(4)

Foster interregional cooperation. China’s high-tech industry’s GIE shows significant spatial spillover effects. To leverage these synergies, the government should create platforms for collaboration, particularly for joint research, talent exchange programs, and sharing best practices. Cross-regional alliances, such as innovation clusters, should be encouraged to facilitate knowledge transfer, resource sharing, and joint R&D efforts, thus improving efficiency and sustainability in the high-tech industry.

-

(5)

Enhance technological innovation and talent development. Technological innovation is key to green and sustainable industrial development. The government should increase R&D investments, establish innovation-driven policies, including grants and low-interest loans for green innovation projects, and ensure access to advanced research infrastructure. Talent development should focus on education and training in emerging technologies, such as green manufacturing, AI, and renewable energy while creating a supportive environment for high-tech professionals.

Data availability

The·datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Gao, K. & Yuan, Y. J. Spatiotemporal pattern assessment of china’s industrial green productivity and its Spatial drivers: evidence from city-level data over 2000–2017. Appl. Energy. 307, 118248 (2022).

Liu, K., Dong, S. M., Wang, Y. L. & Chen, Z. F. The green innovation efficiency of Chinese cities: regional differences, distribution dynamics, and convergences. J. Environ. Planning Manage., 2197555. (2023).

Liu, C. Y., Gao, X. Y., Ma, W. L. & Chen, X. T. Research on regional differences and influencing factors of green technology innovation efficiency of china’s high-tech industry. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 369, 112597 (2020).

Yang, W. L., Tan, J. B., Liu, D. H. & Tang, F. Research on the coupling relationship between urban innovation efficiency and economic High-quality development and its Temporal and Spatial characteristics. J. Stat. Inform. 36 (6), 104–119 (2021).

Chen, X. Q., Liu, X. W., Gong, Z. W. & Xie, J. T. Three-stage super-efficiency DEA models based on the cooperative game and its application on the R&D green innovation of the Chinese high-tech industry. Comput. Ind. Eng. 156, 107234 (2021).

Liu, F. M., Li, L., Ye, B. & Qin, Q. D. A novel stochastic semi-parametric frontier-based three-stage DEA window model to evaluate china’s industrial green economic efficiency. Energy Econ. 119, 106566 (2023).

Tu, W. J., Zhang, L. X., Sun, D. Y. & Mao, W. Q. Evaluating high-tech industries’ technological innovation capability and Spatial pattern evolution characteristics: evidence from China. J. Innov. Knowl. 8 (1), 100287 (2023).

Sun, Y. F., Zhang, S. H. & Wang, Y. Research on configuration path of regional collaborative innovation efficiency improvement from the perspective of innovation ecosystem. J. Stat. Inform. 40 (4), 89–100 (2025).

An, B. W., Liu, W., Basang, T. X., Li, C. Y. & Xiao, Y. Energy and air? The impact of energy efficiency improvement on air quality in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30 (38), 89661–89675 (2023).

Xu, D., Yu, B. & Liang, L. N. High-tech industrial agglomeration and Urban innovation in China’s Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration: From the Perspective of Industrial Structure Optimization and Industrial Attributes. Complexity, 2022, 2555182. (2022).

Ghosh, D., Mehta, P. & Avittathur, B. Supply chain capabilities and competitiveness of high-tech manufacturing start-ups in India. Benchmarking-An Int. J. 28 (5), 1783–1808 (2021).

Yang, C., Hua, Y. & Hua, Z. S. R&D investment along the firm life-cycle: new evidence from high-tech industries. Int. J. Technol. Manage. 88 (2–4), 353–388 (2022).

Gan, Q. Q. Financial system and technology innovation in an emerging economy: can innovation efficiency be increased? Kybernetes 52 (12), 6049–6062 (2023).

An, B. W., Xu, P. Y., Li, C. Y., Zhang, L. Y. & Guo, Q. P. Assessing green production efficiency and Spatial characteristics of china’s real estate industry based on the undesirable super-SBM model. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 16367 (2024).

Chen, N. X. & Wang, L. T. Reassessment and diversified decomposition of low-carbon transformation process of china’s industry. J. Stat. Inform. 39 (5), 73–89 (2024).

Xu, W., Zhang, M. T. & Wang, F. Financing efficiency and influencing factors of High-Tech small and Medium-Sized enterprises of information technology industry in the China Yangtze river delta. Sage Open. 13 (4), 21582440231201704 (2023).

Zhou, S. Z., Deng, Q. Z. & Peng, F. Effect of international technology transfer on the technical efficiency of high-tech manufacturing in China: A RAGA-PP-SFA Analysis. Complexity 6633484. (2021).

Yang, T., Zhou, K. L. & Zhang, C. Spatiotemporal patterns and influencing factors of green development efficiency in china’s urban agglomerations. Sustainable Cities Soc. 85, 104069 (2022).

Chen, Q., Chen, W. X., Wu, D., Zheng, L. & Li, J. F. Spatiotemporal evolution and influencing factors of tourism development efficiency in the Yangtze river economic belt, China. J. Clean. Prod. 379, 134722 (2022).

Zhou, Y. X. & Lu, Y. Spatiotemporal evolution and determinants of urban land use efficiency under green development orientation: insights from 284 cities and eight economic zones in china, 2005–2019. Appl. Geogr. 161, 103117 (2023).

An, B. W., Xu, P. Y., Pan, D., Li, X. T. & Wang, D. Calculation and structural analysis of total factor energy efficiency in high carbon sectors. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 3618 (2025).

Mishra, A. R., Rani, P., Alrasheedi, A. F. & Tirkolaee, E. B. Assessing the challenges of collaborative innovation systems in public higher education: Interval-valued intuitionistic fuzzy combined compromise solution approach. Group Decis. Negot. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-025-09941-0 (2025).

Naskar, S. T., Hota, P. K. & Gupta, V. The efficiency paradox: how high-performance work systems interact with entrepreneurial orientation in hostile environments to impact firm performance in US firms. Int. Entrepreneurship Manage. J. 21 (1), 59 (2025).

Ding, Y. J., Li, B., Lan, D. H., Yu, C. R. & Zhang, X. Q. Research on wage distortion in R&D and innovation activities -- evidence from china’s listed manufacturing enterprises. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance. 102, 104342 (2025).

Edeh, J. & Prévot, F. Beyond funding: the moderating role of firms’ R&D human capital on government support and venture capital for regional innovation in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 203, 123351 (2024).

Zhang, B. & Chen, P. Digital technology innovation and common prosperity within enterprises: destruction or creation. Environ. Dev. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-024-05912-8 (2025).

Zhang, H. J. Benefit evaluation of economic management and green environment construction from the perspective of innovation-driven. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 23 (7), 119 (2024).

Yang, B., Lin, C. & Chen, W. Governance mechanism of the excess capacity of the photovoltaic enterprises from the perspective of technological innovation. Light Eng. 25 (3), 44–50 (2017).

Hu, B. L. Linking business models with technological innovation performance through organizational learning. Eur. Manag. J. 32 (4), 587–595 (2014).

Li, T. H., Wen, J. Y., Zeng, D. W. & Liu, K. Has enterprise digital transformation improved the efficiency of enterprise technological innovation? A case study on Chinese listed companies. Math. Biosci. Eng. 19 (12), 12632–12654 (2022).

Wan, Q. C., Ye, J. F., Zheng, L., Tang, S. Y. & Tang, S. Y. The impact of government support and market competition on china’s high-tech industry innovation efficiency as an emerging market. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 192, 122585 (2023).

Fried, H. O., Lovell, C. A. K., Schmidt, S. S. & Yaisawarng, S. Accounting for environmental effects and statistical noise in data envelopment analysis. J. Prod. Anal. 17, 157–174 (2002).

Avkiran, N. K. & Rowlands, T. How to better identify the true managerial performance: state of the Art using DEA. Omega-International J. Manage. Sci. 36 (2), 317–324 (2008).

Wang, R., Wang, Q. Z. & Yao, S. L. Evaluation and difference analysis of regional energy efficiency in China under the carbon neutrality targets: insights from DEA and theil models. J. Environ. Manage. 293, 112958 (2021).

Barro, R. J. & Sala-i-martin, X. Regional growth and migration: a Japan-United States comparison. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 6 (4), 312–346 (1992).

Sun, Z. J., Pellegrini, M. M., Wang, C. Z. & Yu, Z. How does government support promote firms’ intellectual capital? An empirical analysis of micro-mechanisms. J. Intellect. Capital. 22 (6), 1000–1029 (2021).

Yang, N. N., Liu, Q. M. & Chen, Y. E. Does industrial agglomeration promote regional innovation convergence in china?? Evidence from High-Tech industries. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manage. 70 (4), 1416–1429 (2023).

Yap, X. S. & Rasiah, R. Catching up and leapfrogging in a high-tech manufacturing industry: towards a firm-level taxonomy of knowledge accumulation. Knowl. Manage. Res. Pract. 15 (1), 114–129 (2017).

Amanzou, N. A. A., Diarrassouba, A. S., Kouassi, A. E. & Konan, K. J. Knowledge as determinant of total factor productivity in West African economic and monetary union (WAEMU). J. Knowl. Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01609-x (2023).

Xu, Y. et al. Making technological innovation greener: does firm digital transformation work? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 197, 122928 (2023).

Liu, F., Tang, L., Liao, K. C., Ruan, L. J. & Liu, P. S. Spatial distribution and regional difference of carbon emissions efficiency of industrial energy in China. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 19419 (2021).

Zhang, Y. T., Chen, H. C. & He, Z. M. Regional green innovation efficiency and dynamic evolution of Chinese industrial enterprises: a three-stage super-efficiency DEA method based on cooperative game. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29 (59), 89387–89410 (2022).

Gómez-Antonio, M. & Sweeney, S. Testing the role of intra-metropolitan local factors on knowledge-intensive industries’ location choices. Annals Reg. Sci. 66 (3), 699–728 (2021).

Li, E. J. & An, Z. W. Does transportation infrastructure construction enhance enterprise innovation resilience in china?? Sustainability 16 (7), 2931 (2024).

Lee, A. H. I., Chen, S. C. & Kang, H. Y. A decision-making framework for evaluating enterprise resource planning systems in a high-tech industry. Qual. Technol. Quant. Manage. 17 (3), 319–336 (2020).

Aydin, A. & Parker, R. P. Innovation and technology diffusion in competitive supply chains. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 265 (3), 1102–1114 (2018).

Holm, J. R. et al. Labor mobility from R&D-intensive multinational companies: implications for knowledge and technology transfer. J. Technol. Transfer. 45 (5), 1562–1584 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bo-Wen An: Formal analysis, Writing-review & editing, Roles/Writing-original dra, Validation, Visualization, Software, Supervision; Pei-Yuan Xu: Visualization, Conceptualization, Investigation; Long-Zhan Liu: Visualization, Software, Data curation, Conceptualization, Investigation; Chun-Bo Li: Visualization, Software, Data curation, Conceptualization, Investigation; Qiu-Ping Guo: Project administration, Resources, Methodology, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

An, BW., Xu, PY., Liu, LZ. et al. Assessing green innovation efficiency and spatial characteristics of China’s high tech industry based on the three stage undesirable SBM model. Sci Rep 15, 29917 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16189-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16189-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The evaluation of true green technology innovation efficiency in China's provinces based on the improved three-stage SBM-SE-DEA model

Environment, Development and Sustainability (2025)