Abstract

Monoamine neurotransmitters, such as serotonin and melatonin, are of significant scientific interest due to their widespread influence across various tissues. They play crucial roles in the hormonal and neuronal systems, controlling numerous physiological processes, including antioxidant, neuroprotective, anticancer, cardiovascular function, platelet aggregation, and psychiatric disorders. In this study, we present a direct analysis revealing the nonlinear optical properties of serotonin and melatonin under femtosecond (fs) pulsed laser excitation through the Z-scan and quantum chemical methods. Under the specified Z-scan experimental conditions, these monoamine neurotransmitters exhibit positive refractive and absorptive nonlinearities. Here, the origin of this nonlinearity is attributed to the electronic polarization effect. Specifically, nonlinear refraction is influenced by the self-focusing effect, while nonlinear absorption is governed by the reverse saturable absorption effect (RSA). The experimental data from the Z-scan method correlate with the quantum chemical method, and we observe that, at the highest experimental concentration (550 mM), the theoretical values of ⟨γ⟩ for serotonin and melatonin are approximately 15.78% and 33.84%, respectively, of the experimental values. Several novel chemical reactivity descriptors are calculated using the quantum chemical method to comprehend various aspects of pharmacological science. Furthermore, molecular docking simulations are carried out to conduct a thorough investigation into the binding affinity and poses of serotonin and melatonin with their receptors. The prediction of non-bonding weak interactions of serotonin and melatonin assures potent binding with their receptors. The findings of this research could provide valuable understanding, aiding in the development of novel therapeutic approaches focused on processes regulated by serotonin and melatonin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Serotonin and melatonin, commonly known as Indolamines, are two essential biogenic monoamine neurotransmitters that serve various biological functions across all kingdoms of life1,2. Tryptophan serves as the common precursor for both serotonin and melatonin. Their structures consist of a five-membered nitrogen-containing ring fused to a benzene ring (indole core). However, their functional groups differ: serotonin has a hydroxyl group (-OH) on the benzene ring and a primary amine (-NH2) on its ethyl side chain, whereas melatonin replaces the hydroxyl with a methoxy group (-OCH3) and the amine with an N-acetyl group (-NHCOCH3). The synthesis of serotonin involves the action of tryptophan hydroxylase, transforming the amino acid tryptophan into 5-hydroxytryptophan. This is then followed by a decarboxylation process, ultimately resulting in the formation of 5-hydroxytryptamine, commonly known as serotonin3. Melatonin synthesis begins with the conversion of serotonin into N-acetylserotonin. Subsequently, N-Acetylserotonin undergoes further transformation to yield melatonin4. The synthesis of serotonin and melatonin is interconnected, meaning that changes in serotonin levels can impact melatonin levels. Consequently, a deficiency in serotonin may lead to reduced levels of melatonin as well. Serotonin functions in both the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system. Although only 10% of serotonin is produced by neurons located in the central nervous system, it is for its function in the brain for which it is better known. Serotonin is stored in the presynaptic vesicles; upon the activation of the nerve cell, it is released into the synaptic cleft, where it binds to postsynaptic receptors. Moreover, Perinatal serotonin signaling plays a dynamic role in shaping the development of cortical GABAergic circuits, ultimately impacting sensory encoding throughout life5. Serotonin receptor function has been implicated in the pathophysiology of various psychiatric disorders6,7,8. The behavioral and neuropsychological processes in the central nervous system modulated by serotonin include mood, perception, reward, anger, aggression, appetite, memory, sexuality, and attention. Indeed, it’s challenging to identify a human behaviour that isn’t influenced by serotonin9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Serotonin also plays a key role in regulating cancer cell migration, metastasis, and angiogenesis16,17. An estimated 90% of the serotonin in the human body is stored in enterochromaffin cells located in the gastrointestinal tract, which has been increasingly recognized for its hormonal, autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine actions18. When serotonin is released from the enterochromaffin cell, it is frequently introduced to the bloodstream, where it interacts with blood platelets; the platelets absorb the serotonin, where it functions for haemostasis19. Liu et al. have shown that the serotonin signaling in the vascular niche plays a key role in regulating the immune response of the Drosophila lymph gland, a hematopoietic organ20. Changes in plasma serotonin levels have been linked to various cardiovascular conditions, such as coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular ischemia, and heart attacks21,22. Patients with hypertension often exhibit increased plasma levels of serotonin, along with a significant reduction in serotonin uptake and content within platelets23. Moreover, serotonin enhances hair follicle homeostasis by activating dermal papilla cells and upregulating hair growth-related genes24. On the other hand, melatonin, often referred to as the “hormone of darkness,” is produced by the pineal gland in response to darkness, particularly during nighttime25. It is also observed that bright light exposure from afternoon to early evening reduces subsequent melatonin production in adolescents26. Recently, Tamanna et al. have shown that Serum melatonin levels as a potential biomarker for assessing COVID-19 severity27. There is considerable interest in melatonin as a therapeutic approach for a range of conditions, especially sleep disorders28,29. This versatile molecule exhibits anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticoagulant properties, along with its ability to protect the endothelium30,31. Research indicates that melatonin demonstrates protective properties against specific neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease32,33,34. There is also increasing evidence supporting the significant role of melatonin in reproductive medicine35,36.

The optical and nonlinear optical properties of serotonin and melatonin have been extensively investigated due to their biological significance37,38,39,40. Serotonin exhibits characteristic absorption and emission features that are highly sensitive to the surrounding environment. Chattopadhyay et al. demonstrated that the fluorescence properties of serotonin, including its intensity, emission maximum, and fluorescence lifetime, are strongly dependent on pH37. Like other indole-containing molecules, serotonin displays fluorescence emission in the ultraviolet region. Its broad absorption spectrum extends from 200 to 320 nm in the UV region41. Notably, serotonin fluorescence has also been detected in living cells42demonstrating its potential as a biological probe, particularly under both mono- and multi-photon excitation conditions. Mendoza et al. have shown that the response of serotonin to multiphoton excitation is highly nonlinear41. In addition, Sakshi et al. reported that under continuous-wave laser excitation, serotonin exhibits negative nonlinear refractive and absorptive behavior39. Similarly, the fluorescence of melatonin has also been found to be solvent-dependent43. Moreover, melatonin exhibits positive nonlinear refractive and absorptive behavior under both continuous-wave and picosecond pulsed laser excitation40.

In view of the importance of these two monoamine neurotransmitters, researchers have employed a variety of techniques for their detection and quantification, which may serve as crucial pathways for developing diverse diagnostic tools to study neurological disorders arising from their imbalances or deficiencies. Photophysical methods have proven particularly valuable, leveraging the inherent optical properties of these molecules. Examples include fluorogenic detection of serotonin in live cells44, a sensitive and specific fluorescence assay for estimation of tissue serotonin45, genetically encoded fluorescent sensors for serotonin46, optical sensors for detecting melatonin47, ratiometric surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) based assay for detection of serotonin48, detection and quantification of melatonin and serotonin through SERS49, nanomaterials based optical sensors for the detection of melatonin and serotonin50. Beyond photophysical approaches, other established methods like high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)51, micro-dialysis52 and nuclear medicine tomographic imaging (such as positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)) also play significant roles for the detection and quantification of neurotransmitters53,54. Min et al. introduce PillTrek, a smart ingestible capsule capable of real-time monitoring of key gut biomarkers, including serotonin55. Zhao et al. have recently introduced implantable aptamer-functionalized field-effect transistor neuroprobes capable of monitoring neurotransmitter levels in vivo56. Each technique offers distinct advantages and limitations. Recently, there has been growing interest in nonlinear photophysical tools, especially for their application in biological contexts. Techniques like two-photon fluorescence microscopy enable noninvasive studies of biological specimens, offering unique benefits such as reduced photodamage and enhanced penetration depth57. These multi-photon absorption and emission strategies have been successfully applied to monitor neurotransmitters, evidenced by studies using three-photon excited fluorescence imaging in neuroscience, near-infrared catecholamine nanosensors for high spatiotemporal dopamine imaging, measuring serotonin distribution in live cells with three-photon excitation, three-photon microscopy used to image the 5-HT concentration and content of individual secretory granules, label-free imaging of neurotransmitters in live brain tissue by multi-photon ultraviolet microscopy58,59,60,61.

Moreover, it is highly essential to explore some of their unknown photophysical properties that can be used in the context of various disease conditions. Therefore, in the present study, we have investigated the nonlinear optical properties of serotonin and melatonin under fs pulsed laser excitation using the Z-scan technique by varying the concentrations from 150 to 550 mM. Here, the nonlinear findings of Indolamines are also compared with the quantum chemical calculations. Besides, several novel chemical reactivity descriptors have also been calculated to comprehend various aspects of pharmacological sciences, as well as we have also predicted the binding poses and calculated the binding affinity of serotonin and melatonin to their all-receptor subtypes that might have various pharmacological significance. In contrast to other methods, the Z-scan technique emerges as a practical and advantageous approach for nonlinear photophysical investigations because of its high sensitivity and simple experimental geometry62. Over the past few decades, this method has been widely used for characterizing the nonlinear properties of a wide range of materials39,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74. Like in multiphoton absorption in amyloid protein fibers by Piotr Hanczyc et al. shown that amyloids, which, when in large aggregates, are responsible for diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, have strong nonlinear optical absorption, which is not present in native non-fibrillized protein75. Freitas et al. proposed the Z-scan method to determine the oxidative State of Low-density lipoprotein and its association with multiple cardiometabolic biomarkers76. Alves et al. have shown the Z-scan technique in detecting circulating free DNA for prostate cancer diagnosis and monitoring77.

Overall, we expect the findings of this study to open new avenues for the development of advanced diagnostic tools for investigating neurological disorders associated with disruptions of monoamine neurotransmitter levels. In particular, understanding the nonlinear optical (NLO) properties of serotonin and melatonin may enable the design of optical detection and monitoring platforms that exploit changes in NLO parameters and their sign as indicators of their imbalance. We anticipate that these parameters will undergo significant alterations in the event of neurotransmitter imbalance or deficiency.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

The neurotransmitters serotonin hydrochloride and melatonin were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry, Japan, and Sigma Aldrich, USA, respectively. Figures 1(A) and 1(B) show the chemical structures of serotonin hydrochloride and melatonin, respectively. We used Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with a pH of 7.4 as a solvent for serotonin to maintain physiological pH, while Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sisco Research Laboratories, India) was used as a solvent for melatonin. All the chemicals obtained were used as received. The UV-visible absorption spectra of the samples were recorded using a spectrophotometer from Shimadzu UV-2600, Japan.

Z-scan measurements

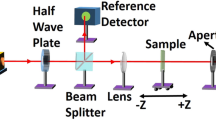

The Z-scan technique is based on the principle of spatial beam distortion. It is further classified into the closed-aperture (CA) Z-scan and the open-aperture (OA) Z-scan. The CA Z-scan is mainly sensitive to nonlinear refraction (NLR), while the OA Z-scan is sensitive to only nonlinear absorption (NLA). In the presence of any optical nonlinearity in the sample, the sample may behave as either a converging lens or a diverging lens. The obtained Z-scan curves will provide us with the nonlinear characteristics of the sample.

To calculate the nonlinear optical parameters of the sample, A Ti: Sapphire fs laser (Coherent Libra HE) with a wavelength of 800 nm, a pulse width of 50 fs, and a repetition rate of 1 kHz was used as the primary laser source. The output beam from the Ti-Sapphire laser system was utilized to pump an optical parametric amplifier (OPA, TOPAS-Prime) to generate a laser pulse of 100 fs at 530 nm and a repetition rate of 1 kHz for the CA and the OA Z-scan measurements. Figures 2(A) and 2(B) illustrate the experimental setups for the CA and OA Z-scan measurements, respectively. A plano-convex lens with a focal length of 20 cm was employed to focus the input beam. At the focus point, the beam converges where the beam waist (w0) was ~ 35 μm, and the associated Rayleigh range (Z0) was ~ 7 mm. The corresponding intensity at focus was ~ 52 GW/cm2. The sample was placed in a 1 mm quartz cuvette for scanning the sample (the thickness of the sample was less than the Rayleigh range to fulfill the thin sample approximation condition). A motorized translational stage (Newport, GST-150) connected to a motion controller (Newport, ESP-150) was used to scan the sample across the focal region of the laser beam. The laser beam was split into two components using a beam splitter with a 90% transmission and 10% reflection [90(T)/10(R)] and was simultaneously captured by two Si-photodiode detectors (Thorlabs, PDA100A-EC) for measuring laser fluctuations and CA Z-scan measurements.

The size of the aperture was 2 mm in diameter (it was chosen to keep the linear aperture transmittance (S) between 0.1 < S < 0.5). We removed the aperture for the OA Z-scan measurements. Neutral density filters (F2 and F3) were employed before the photodiodes to prevent any saturation. We used plano-convex lenses (L1 and L3) with a 15 cm focal length to focus the laser beam at the detectors. Lock-in amplifiers (7225 DSP) were employed to capture the data, ensuring a good signal-to-noise ratio. An optical chopper operating at 350 Hz was positioned in the beam path before the sample to provide a reference frequency for the lock-in amplifiers. Both the lock-in amplifiers and translational stage were integrated into LabVIEW 2012 software for data acquisition. Origin 9.0 was used for graph plotting and data analysis. It is important to note that the impact of the laser fluctuations (if any) was removed from the sample data (recorded by D2) by dividing the sample data by laser fluctuation data (recorded by D1).

Here we have used an ultrashort pulse with a pulse width of 100 fs and a repetition rate of 1 kHz; therefore, the Sheik-Bahae model (SBM) is a suitable choice for analyzing experimental data in this scenario. Sheik-Bahae et al. employed a novel Gaussian decomposition approach to analyze the nonlinear response of the sample at far-field intensity. A key aspect of this approach is the local interaction assumption between the radiation field and the sample, where susceptibility is considered dependent solely on local intensity62. However, in the CA Z-scan experiment, it is difficult to ignore the contribution of nonlinear absorption; therefore, Yin et al. modified the Sheik-Bahae theory by incorporating nonlinear refraction and nonlinear absorption for efficient data analysis78. For cubic nonlinearity and small phase change, the given equation can be used to fit the experimental CA Z-scan profiles64,78.

Where \(\:{\upzeta\:}\) = Z/Z0. The \(\:{{\Delta\:}\phi\:}_{0}\) and \(\:{{\Delta\:}{\uppsi\:}}_{0}\) are the phase shifts due to nonlinear refraction and nonlinear absorption, respectively, and defined as:

Where Leff represents the effective path length of the sample, while I0 denotes the intensity of the laser beam at its focus, λ stands for the wavelength of the laser light, OD indicates the optical density, and α0 represents the linear absorption coefficient.

The nonlinear absorption under both the effects of saturable absorption (SA) and RSA can be expressed as

Here, Is represents the saturation strength, and β is the nonlinear absorption coefficient.

The first term of Eq. 5 represents the SA, while the second term represents the two-photon absorption responsible for RSA. The normalized transmittance in OA Z-scan can be expressed as79

The real part of the third-order susceptibility (χR(3)) is quantified by the nonlinear refractive index, whereas the imaginary part (χI(3)) is measured by the nonlinear absorption coefficient. The overall third-order nonlinear optical response, denoted as χ(3), is the sum of these real and imaginary components.

Here, ε0 represents the permittivity of free space, c denotes the speed of light, and ω is the angular frequency of the optical wave. Furthermore, the parameter β is related to the molecular two-photon absorption cross-section (σ2p) by the following expression:

Where hν represents the photon energy (J/photon), and N₀ denotes the molecular concentration (molecules/m3).

The relationship between the third-order electric susceptibility χ(3) and the second-order hyperpolarizability can be expressed as80

Where f represents the Lorentz local field correction factor.

Computational methods

The quantum chemical calculations of serotonin and melatonin were carried out using the G09 software package. The initial molecular coordinates were taken from PubChem. The molecules were then optimized using the DFT method with the B3LYP/6-311 + + G(d, p) basis set. Frequency calculations were then performed on this optimized structure at the same level of theory. The absence of imaginary frequencies, indicating non-negative values, confirms the stability of the geometry optimization. The B3LYP hybrid functional combined with the 6-311 + + G(d, p) basis set is chosen for our DFT calculations, considering its proven reliability and applicability for predicting the electronic structure and molecular properties of organic molecules. Specifically, this combination has been shown to provide a good balance between computational cost and accuracy for evaluating molecular geometries, electronic properties, and hyperpolarizability calculations. This methodology is well-supported in the literature for the accurate prediction of hyperpolarizability and other electronic properties81,82,83. The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), and HOMO-LUMO gap for the isolated molecule and the molecule in solvent phases were also calculated. Furthermore, the hyperpolarizability calculations for isolated serotonin and melatonin molecules at 530 nm, along with serotonin in the water phase and melatonin in DMSO at 530 nm, were performed with the same functional and basis set using the finite field method to understand the molecular basis of the observed nonlinear optical properties.

The molecular docking was performed for serotonin and melatonin with respect to their corresponding receptors using the software Autodock Vina84,85. It uses the confluence of two algorithms, i.e., the genetic algorithm (GA), for global search to find the optimum binding region and iterative local optimization (ILO) to accurately refine the binding pose. These poses are scored by an empirically derived scoring function, including weak molecular interactions like van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic interactions. The scoring function returns the most energetically favorable (having the highest binding affinity) binding poses. The 3D structure of all serotonin receptors and serotonin were retrieved from the AlphaFold site and PubChem database, respectively (their respective source information is provided in the supplementary file (Table S1)). The same procedure was followed for melatonin and its receptors. All the serotonin and its receptors were prepared prior to docking. As the defined search space depends on the size of the receptors, different grid boxes for different receptors were demarcated, and for better electrostatic interaction, Gasteiger charges were computed and distributed to the receptors, and exhaustiveness was set to 30 for precise calculations. The docked complexes were analyzed, and their 2D and 3D interaction diagrams were obtained using LigPlot + and PyMOL version 2.5, respectively. The descriptors of the grid box and the magnitude of Gasteiger charges are also provided in the supplementary file (Table S1).

Results and discussion

Frontier molecular orbital analysis

The HOMO and LUMO, collectively termed frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs), significantly influence the optical properties of a molecule. The FMOs of serotonin and melatonin molecules were calculated using the B3LYP/6-311 + + G(d, p) method for the isolated molecule as well as in the solvent phase (water is used for serotonin, and DMSO is used for melatonin). Figure 3 displays the FMOs of serotonin and melatonin. The energy levels associated with the HOMO and LUMO, along with their energy gap, serve as indicators of the biological activity of a molecule. The HOMO can be conceptualized as the outer orbital electrons, making it prone to donate these electrons as an electron donor. Thus, the ionization potential is directly linked to the energy of the HOMO. Conversely, the LUMO has the capability to accept electrons, and its energy is directly associated with electron affinity. The HOMO-LUMO gap also explains the charge transfer within the molecule86,87. The polarizability and stability (Hardness and softness) of a molecule are correlated with the HOMO-LUMO gap. A larger HOMO-LUMO gap indicates that electrons are tightly bound to the molecule, making it less susceptible to external electric fields. As a result, the molecule exhibits lower polarizability. Furthermore, a low value of this parameter suggests a charge transfer interaction within the molecule, thereby impacting the molecule’s NLO activity88. Moreover, if the energy gap of a molecule is smaller, the chemical reactivity is stronger, and the kinetic stability is weaker. Several novel chemical reactivity descriptors have been introduced to comprehend various aspects of pharmacological sciences. By utilizing the energies of the HOMO and LUMO, the ionization energy (I) and electron affinity (A) can be represented as I = -EHOMO, A = -ELUMO. While the hardness (τ), chemical potential (µ), and global electrophilicity (ξ) are described by the following relationships: τ = (I-A)/2, µ = - (I + A)/2, and ξ = µ2/2τ88,89,90. All the parameters were calculated and summarized in Table 1.

Frontier orbitals of (a) Serotonin in the isolated state, (b) Serotonin in the water phase, (c) Melatonin in the isolated state, and (d) Melatonin in DMSO. The positive charge is depicted in dark red, while the negative charge is shown in green. For clarity, atoms are visually distinguished as follows: carbon (grey), hydrogen (white), oxygen (red), and nitrogen (blue).

We have noticed that the HOMO-LUMO gap of serotonin and melatonin displays slight variations in values depending on the environment (isolated vs. solvent). This suggests that the surrounding environment influences their behaviour to some extent, although no major change is observed based on the environment. When a molecule is dissolved in a solvent, it undergoes various interactions with the solvent molecules, including dipole-dipole interactions, hydrogen bonding, and general solvent–solute interactions. These interactions often stabilize the excited state (LUMO) more than the ground state (HOMO), resulting in a decreased HOMO-LUMO energy gap. This leads to molecules absorbing at longer wavelengths (lower energy) in solution compared to the gas phase. The HOMO-LUMO energy gap decreases more in water than in DMSO because water is far more polar (with a dielectric constant of ~ 80 compared to ~ 47 for DMSO) and forms much stronger hydrogen bonds. This strong hydrogen-bonding capability significantly stabilizes the excited state of serotonin, contributing to the observed decrease in the HOMO-LUMO gap. Although DMSO is a highly polar solvent, its ability to form hydrogen bonds is weaker compared to water. Therefore, the stabilization effect is more pronounced in water, leading to a greater reduction in the HOMO-LUMO gap for serotonin in aqueous solution. Compared to serotonin, melatonin exhibits slightly lower reactivity. We have also observed that the ionization potential, electron affinity, hardness, chemical potential, and global electrophilicity of serotonin are higher in the water phase compared to the isolated molecule. Conversely, melatonin in DMSO exhibits the opposite trends as per the description given above.

UV–Visible absorption spectra

The UV-visible absorption spectra of serotonin were examined for the isolated molecule and in an aqueous phase, while those of melatonin were studied for the isolated molecule and in DMSO. This analysis was conducted using a time-dependent approach at the B3LYP level of theory with the 6-311 + + G(d, p) basis set. The theoretical calculations in the solvent phase were performed with the Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM). Serotonin exhibits a peak at 218 nm (π → σ∗) and 274 nm (n → σ∗) for the isolated molecule, while in its aqueous phase, it demonstrates peaks at 219 nm (π → σ∗) and 275 nm (n → σ∗). Similarly, melatonin displays a peak at 217 nm (π → σ∗) and 271 nm (n → σ∗) in its isolated state, whereas in DMSO, it manifests two peaks, one at 219 nm (π → σ∗) and the other one at 273 nm (n → σ∗). In the brackets, we have assigned the possible transitions for the absorption maxima here; transitions from non-bonding orbitals (n) to antibonding orbitals (σ*) are represented by n → σ∗, and π bonding orbitals to σ* antibonding orbitals are denoted by π → σ∗. The computationally calculated absorption spectra of serotonin and melatonin in both the isolated state and the solvent phases are shown in Fig. 4(a).

The UV-visible absorption spectra of serotonin in PBS buffer (pH 7.4) and melatonin in DMSO were recorded at various concentrations by using a 1 mm thick quartz cuvette to calculate the optical density at 530 nm, which is the working wavelength for the nonlinear investigation. The absorption spectra of serotonin and melatonin in 1 mM concentration are shown in Fig. 4(b), and both are consistent with the previously reported ones41,91. The wide absorption spectrum of serotonin spans from 204 to 325 nm in the UV region, exhibiting absorption peaks at 204, 220, 276, 295, and 309 nm under a physiological pH of 7.4. On the other hand, melatonin displays peaks at 282 nm, 298 nm, and 312 nm, with its absorption spectrum ranging broadly from 252 to 328 nm. The presence of additional absorption peaks in the higher wavelength regions (more than 290 nm) in the UV-Vis spectra for both serotonin and melatonin could be due to the aggregation effect or the formation of photoproducts. Notably, both serotonin and melatonin show the major peaks at 276 nm and 282 nm, respectively, while showing insignificant absorption at 530 nm. The UV-Vis absorption spectra for all other concentrations (150 mM, 250 mM, 350 mM, 450 mM, and 550 mM) of both serotonin and melatonin are presented in the supplementary information (Fig. S1).

(a) UV-Vis absorption spectra of (A) Serotonin in the isolated state, (B) Serotonin in water, (C) Melatonin in the isolated state, (D) Melatonin in DMSO calculated from the DFT (PCM), B3LYP – 6311 + + G(d, p)). (b) The absorption spectra of serotonin in PBS buffer and melatonin in DMSO. The arrow indicates the working wavelength (530 nm).

The comparison between theoretical and experimental UV-visible absorption spectra reveals a better agreement for serotonin than for melatonin. For serotonin in water, the theoretical peaks at 219 nm and 275 nm align well with experimental peaks at 220 nm and 276 nm, validating the predicted π → σ* and n → σ* transitions. However, additional experimental peaks at 204 nm, 295 nm and 309 nm are not present in the theoretical spectra. The PCM-based calculations for melatonin in DMSO predict peaks at 219 nm and 273 nm, whereas the experimental data exhibit significantly red-shifted peaks at 282 nm, 298 nm, and 312 nm. These differences suggest that many factors influence the differences between the experimental and theoretical UV-Vis absorption spectra. These differences primarily arise due to the inherent limitations of the theoretical approach, which models an isolated molecule within a simplified solvent environment using the PCM. While this approach reasonably captures bulk solvent effects through dielectric polarization, it does not account for more complex phenomena present under experimental conditions. In the actual experimental environment, factors such as specific solvent–solute interactions, solute–solute interactions at higher concentrations, molecular aggregation, and temperature-dependent effects significantly influence the observed spectra. These effects can lead to additional peaks, spectral broadening, and red or blue shifts that the theoretical calculations, based on an idealized, isolated molecular model, can’t fully predict.

Nonlinear optical measurements

fs-induced nonlinear optical study of serotonin

In this study, we explored the nonlinear optical properties of serotonin in PBS buffer (pH ~ 7.4) under fs pulsed laser excitation. In order to record data on nonlinear refraction and absorption, we used the CA and OA Z-scan techniques, respectively. We recorded the Z-scan profiles for both CA and OA by varying the concentration (150 mM, 250 mM, 350 mM, 450 mM, and 550 mM) while maintaining a constant laser peak intensity (52 GW/cm2). The CA and OA Z-scan profiles are illustrated in Figs. 5 and 6, respectively. In the CA Z-scan profiles, a valley followed by a peak is observed, whereas we have a symmetric valley with respect to the focus (z = 0) in the OA Z-scan profiles. The valley followed by the peak pattern in the CA Z-scan profiles suggests a positive sign of the nonlinear refractive index, which is due to the self-focusing effect, whereas a decrease in transmittance with the increase in intensity is characteristic of the reverse saturable absorption (RSA) effect62. Here, the minimum transmittance at the focus signifies the positive absorptive nonlinearity62. The RSA effect seems to originate from the process of two-photon absorption (TPA). This TPA process can be explained on the basis of linear absorption, which is supported by the fact that serotonin shows minimal absorption at the excitation laser’s working wavelength (530 nm) but has a strong peak at 276 nm, which is close to half of the excitation wavelength. In addition, the measured ΔTP−V of the CA Z-scan profile is found to increase with the concentration [for instance, while increasing the concentration from 150 mM to 550 mM (~ 3.66 times), ΔTP−V increases from 0.962 to 1.123 (~ 1.17 times)]. Since we have used ultrashort pulses at a 1 kHz repetition rate, thermal effects are expected to be negligible; the increase in the nonlinearity with the concentration may be due to the fact that at higher concentrations, the density of electrons increases for the nonlinear interactions. This enhances the overall electronic polarization of the medium. Furthermore, we have also noticed that ΔTV is slightly higher than ΔTP in the CA Z-scan profiles for all concentrations of the sample. This further confirms the presence of the RSA effect. We have also examined the ΔTV of the OA Z-scan profile for all concentrations and found no significant correlation between ΔTV and the sample concentration. In the CA Z-scan profile, an easily measurable quantity is defined as the separation between the peak and valley positions given by ΔζP−V = ΔZP−V/Z0. This measurement is crucial for determining the order of nonlinearity. We have calculated ΔζP−V for all the concentrations of serotonin and found that the magnitude of ΔζP−V ~ 1.7. A magnitude of ΔζP−V = 1.7 signifies third-order nonlinearity62.

Principally, there are two primary sources of nonlinearity induced by either pulsed or CW laser irradiation: (1) The optical Kerr effect, which arises on a picosecond (ps) to the fs time scale, and (2) The thermo-optical effect or thermal effect, occurring within a timeframe of milliseconds to microseconds. The rise time of the thermal lens (ta) or acoustic transit time is defined as the ratio of acoustic velocity (vs) in a medium to the beam waist (w0). While the thermal relaxation time (tc) is defined as tc= (w02ρCP)/(4κ)64where ρ represents the density of the medium, CP denotes the specific heat at constant pressure, and κ is the thermal conductivity. In the calculation of tc and ta, we have employed physical constants specific to solvents, as very close values of the magnitude of the physical constant of the solvent and the sample make these constants applicable to our study. The parameters employed were w0 (35 μm), ρ (1 g/cm3), CP (4178.3 JK−1Kg−1)92κ (0.631 Wm−1 K−1)93and vs (1529 m/s)94the magnitude of ta and tc is found to be 23 ns and 2.02 ms, respectively. In principle, when tp ≤ ta < tc, the system is recognized to be in a transient regime. Conversely, if ta < tp < tc, then the system is recognized to be in a steady-state regime. The value of ta (= 23 ns) is less than tc (= 2.02 ms) and greater than tp (= 100 fs), i.e., the condition tp ≤ ta < tc is fulfilled, indicating that the nonlinearity is in the transient regime64.

CA Z-scan curves for serotonin in PBS buffer under fs pulsed laser excitation at various concentrations: (a) 150 mM, (b) 250 mM, (c) 350 mM, (d) 450 mM, and (e) 550 mM. Open circles denote the experimental data points, while continuous red lines represent the theoretical fits. The vertical lines shown on the data points are error bars.

To obtain the nonlinear parameters, we have utilized Eqs. 1 and 6 to fit the experimental CA and OA Z-scan profiles, respectively. Instead of using the divided Z-scan method, where the CA Z-scan is divided by the OA Z-scan to isolate the nonlinear refraction, we have followed an alternative approach. In our analysis, the experimental CA Z-scan data, which inherently contains the effects of both nonlinear refraction and nonlinear absorption, were fitted using a combined theoretical model that accounts for both contributions simultaneously. Through this fitting procedure, we were able to accurately extract the information related to pure nonlinear refraction from the CA Z-scan data, whereas a separate OA Z-scan is used to determine the nonlinear absorption parameters. The resulting theoretical fits are depicted by the solid red lines in Figs. 5 and 6. Further, the phase shift caused by nonlinear refraction was extracted as a fitting parameter. The obtained values serve as the basis for calculating various other nonlinear parameters (n2 and χ(3)). Moreover, Eq. 6 was used to calculate the β. Similarly, the experimental 〈γ〉 is calculated by using Eqs. 11 and 12. All the obtained values are listed in Table 2. We have observed from Table 2 that increasing the concentration increases the magnitudes of n2 and χ(3). A ~ 3.6 times increase in concentration increases the magnitude of n2 and χ(3) ~ 1.2 times, whereas 〈γ〉 decreases by ~ 3.05 times. It is observed that there is no significant relationship between β and sample concentration. The positive sign of n2 and β is due to the fact that the nonlinearity is due to the self-focusing and the RSA effect, respectively. The origin of nonlinear refraction may originate from various sources; however, the magnitudes of nonlinear values of serotonin under fs pulsed laser excitation suggest that an electronic polarization mechanism triggers the nonlinearity occurring in the transient regime95. We have also calculated the σ2p for serotonin, and the obtained values are on the order of 10−57 m⁴s/photon, which are in good agreement with previously reported values under femtosecond excitation96.

OA Z-scan curves for serotonin in PBS buffer under fs pulsed laser excitation at various concentrations: (a) 150 mM, (b) 250 mM, (c) 350 mM, (d) 450 mM, and (e) 550 mM. Open circles denote the experimental data points, while continuous red lines represent the theoretical fits. The vertical lines shown on the data points are error bars.

fs-induced nonlinear optical study of melatonin

The nonlinear optical properties of melatonin in DMSO were investigated using a similar experimental approach to that of serotonin. The laser peak intensity was maintained at 52 GW/cm2, while the melatonin concentration was varied from 150 mM to 550 mM. The Z-scan profiles obtained from the CA and OA Z-scans are shown in Figs. 7 and 8, respectively. Across all concentrations investigated in this study, we have observed that the valley-peak pattern in the CA Z-scan profile (Figs. 7(a-e)) and the valley at the focus in the OA Z-scan (Figs. 8(a-e)) are similar to those seen in serotonin. Again, we have identified positive refractive and absorptive nonlinearity, which is attributed to the self-focusing and RSA effects, respectively62. As previously discussed, the RSA effect also originates from a TPA process. The calculation of ΔTP−V for melatonin is carried out for all concentrations from the CA Z-scan curves, demonstrating a rise in ΔTP−V as the sample concentration increases. In particular, while increasing the concentration from 150 mM to 550 mM, the overall ΔTP−V increases from 0.88 to 0.90. This increment is evident because the overall polarization of the medium influences the nonlinearity; hence, increasing the number of molecules increases the strength of nonlinearity. Moreover, we have observed that ΔTV is slightly higher than ΔTP for all sample concentrations. As the curve is not symmetrical with respect to focus, and ΔTV exceeds ΔTP, this once again indicates the presence of the RSA effect64. Consistent with our findings for serotonin, the ΔTV showed no significant correlation with concentration. The separation between the valley and peak positions for melatonin is found within the range predicted for cubic nonlinearity62. Melatonin also exhibits nonlinear behaviour within the transient regime. This is again confirmed by the relation between ta, tp, and tc. Specifically, the condition tp ≤ ta ˂ tc is satisfied. Here, ta and tc are 24 ns and 3.64 ms, respectively. For calculating tc and ta, the following parameters are used: w0 (35 μm), ρ (1.1 g/cm3), CP (1978.4 JK−1Kg−1)92κ (0.1830 Wm−1 K−1)93and vs (1451 m/s)97.

CA Z-scan curves for melatonin in DMSO under fs pulsed laser excitation at various concentrations: (a) 150 mM, (b) 250 mM, (c) 350 mM, (d) 450 mM, and (e) 550 mM. Open circles denote the experimental data points, while continuous red lines represent the theoretical fits. The vertical lines shown on the data points are error bars.

To calculate the nonlinear parameters, the experimental data of melatonin is fitted with the theoretical curve using Eq. 1 for the CA Z-scan and Eq. 6 for the OA Z-scan. Calculated nonlinear parameters (n2, β, σ2p, χ(3), and 〈γ〉) are summarized in Table 3. Our results indicate that the concentration influences the nonlinear parameters. We haveobserved that n2 and χ(3) increase by ~ 1.1 times and 〈γ〉 decreases by ~ 3.33-fold with a rise in concentration by ~ 3.6 times. The calculated σ2p for melatonin is on the order of 10⁻⁵⁷ m⁴s/photon, which is in good agreement with previously reported values under fs excitation96. Similar to the case of serotonin under fs pulsed laser excitation, we did not find a significant correlation between the β and the concentration of the sample. The positive values of n2 and β suggest self-focusing and the RSA effect, respectively. The magnitudes of the nonlinear values observed in melatonin indicate that the nonlinearity, operating within the transient regime, is governed by an electronic polarization mechanism95. Comparing the data for indolamines (both serotonin and melatonin) under fs excitation shows that serotonin has stronger refractive nonlinearity than melatonin. However, melatonin exhibits stronger absorptive nonlinearity than serotonin. This may be attributed to the presence of additional functional groups in melatonin, which could make TPA more favourable.

OA Z-scan curves for melatonin in DMSO under fs pulsed laser excitation at various concentrations: (a) 150 mM, (b) 250 mM, (c) 350 mM, (d) 450 mM, and (e) 550 mM. Open circles denote the experimental data points, while continuous red lines represent the theoretical fits. The vertical lines shown on the data points are error bars.

In the Z-scan experiments, potential sources of experimental errors and uncertainties include laser intensity fluctuations, sample positioning inaccuracies, and uncertainties in determining the Rayleigh range and beam waist at the focal plane. To minimize these effects, a reference detector was used to normalize the transmitted signal and correct for fluctuations in laser intensity. The sample translation stage was motorized and computer-controlled to ensure precise and reproducible movement along the Z-axis. The experimental conditions satisfied the thin sample approximation to minimize additional uncertainties. The experimental errors were estimated from the error bars, and the error margins in all data are within 10%.

In our previous work40we reported negative refractive nonlinearity (self-defocusing) and positive absorptive nonlinearity (RSA effect) under continuous wave (CW) and picosecond (ps) laser excitations, primarily originating from thermo-optical effects governed by saturated atomic absorption and molecular orientation mechanisms, respectively. In contrast, the present study with fs excitation reveals positive refractive and absorptive nonlinearities attributed to self-focusing and TPA-induced RSA effect, respectively. The observed shift in the sign (refractive) and origin of nonlinearity under fs excitation is consistent with the well-established understanding that, under ultrafast excitation, nonlinearities are dominated by purely electronic processes rather than cumulative thermal effects. Furthermore, compared to the ps and CW regimes, the magnitude of refractive nonlinearity is lower under fs excitation. Besides, a comparison of the obtained NLO parameters with other reported values reveals good agreement and supports the validity of our results. Specifically, the n2, β, and σ2p, which are consistent under femtosecond excitation conditions96,98.

Computational insight into molecular hyperpolarizability

Quantum chemical calculations enhance our comprehension of the connection between molecular structure and its nonlinear optical behaviour. Hyperpolarizability calculations were carried out using the finite field approach to explore the nonlinear optical properties of the molecule81. The system’s energy, in the presence of an applied field, is a function of the electric field. The Taylor’s series expansion of the energy under the condition of a weak and homogeneous electric field can be written as89

Where E(0) represents the energy of the unperturbed molecule, Fi denotes the field at the origin, δi, Γij, ηijk, and γijkl are the components of dipole moment, polarizability, the first-order hyperpolarizability and second-order hyperpolarizability, respectively. In order to calculate the frequency-dependent second-order hyperpolarizability (〈γ(–ω; ω1, ω2, ω3)〉), which is associated with the nonlinear optical process of the intensity-dependent refractive index (IDRI), the second-order hyperpolarizability can be written as (for small frequencies)88

Conventionally, in the second-order hyperpolarizability (〈γ(–ω; ω1, ω2, ω3)〉), the first frequency within the parentheses, indicated by the negative sign, represents the emitted radiation frequency. The subsequent frequencies (positive) pertain to absorbed radiation, where ω = ω1 + ω2 + ω3. All numerical results for the hyperpolarizabilities are obtained as G09 output; further, ⟨γ⟩ for IDRI is calculated using Eq. 14. The average second-order hyperpolarizability (⟨γ⟩) of the serotonin and melatonin for isolated molecules and in the solvent phases are summarized in Table 4, and 5, respectively.

A comparative analysis of Tables 4 and 5 reveals that melatonin consistently exhibits higher third-order NLO responses than serotonin across all three hyperpolarizability components, i.e., ⟨γ(0;0,0,0)⟩ (static), ⟨γ(−ω; ω,0,0)⟩ (Kerr effect), and ⟨γ(−ω; ω, ω,− ω)⟩ (IDRI) in both isolated and solvent phase.

This enhanced response in melatonin is attributed to the presence of electron donor and acceptor groups with extensive π-conjugation that provides large intramolecular charge transfer in response to a highly intense laser beam. The effect of the medium is also significant; both molecules show a substantial increase in γ values when moving from the isolated molecules to the molecules in the solvent phase. For instance, serotonin’s ⟨γ⟩ IDRI increases from 0.530 × 10−59 C4m4J−3 to 0.744 × 10−59 C4m4J−3, while melatonin’s increases from 0.698 × 10−59 C4m4J−3 to 1.056 × 10−59 C4m4J−3. This solvent-induced enhancement is consistently observed across the Kerr and static values, highlighting the role of solute-solvent interactions in amplifying the NLO response. Notably, the trend ⟨γ(0;0,0,0)⟩ < ⟨γ(−ω; ω,0,0)⟩ < ⟨γ(−ω; ω, ω,− ω)⟩ is consistently observed for both molecules in both isolated and solvent media.

The theoretical results also show a good agreement with the experimental data from the Z-scan measurements. For serotonin, we observed a one-order difference in magnitude; this one-order difference in the magnitude can be attributed to the experimental conditions conducted in the PBS buffer, contrasting with the computational studies carried out on isolated molecules and serotonin in the water phase. Furthermore, factors such as laser repetition rate and pulse width play a significant role in determining the extent of thermal contributions or purely electronic responses in the measured nonlinearities. For instance, higher repetition rates or longer pulse widths can lead to cumulative heating, resulting in additional thermo-optical nonlinearities, which are not captured in theoretical calculations based purely on electronic structure. Similarly, solution concentration affects the density of active molecules contributing to the NLO response, potentially leading to saturation effects or aggregation at higher concentrations, which may slightly alter the magnitude of the experimental parameters. Beam intensity is also critical, as higher intensities may promote nonlinear processes like two-photon absorption more prominently. These factors collectively contribute to minor variations between experimental and theoretical results. In contrast, computational nonlinear optical results are solely dependent on the specified input frequency. We again noticed that the theoretical results of melatonin also closely align with the experimental data, with only slight variations in magnitude. As explained above, the experimental outcomes might be influenced by various factors.

While comparing the nonlinearity strength, expressed in terms ⟨γ⟩, obtained from experimental IDRI values and theoretical DFT calculations, we observed an interesting trend. The experimental data indicate that serotonin exhibits higher ⟨γ⟩ values compared to melatonin. However, the theoretical calculations performed using the B3LYP/6-311 + + G(d, p) level of theory predict that melatonin possesses a higher ⟨γ⟩ value than serotonin. This discrepancy may be due to the very similar structure of both molecules; hence, they are very competitive. In addition, the choice of different solvents (PBS buffer for serotonin and DMSO for melatonin) can also influence the molecular environment and, consequently, the nonlinear optical properties. Theoretical ⟨γ⟩ values are calculated for isolated molecules or implicit solvent models, which do not fully account for solvent effects, intermolecular interactions, or molecular aggregation that can occur in solution, especially at higher concentrations. In contrast, the experimental ⟨γ⟩ values inherently reflect the actual physical environment, including solute-solvent interactions and concentration-dependent effects, which can enhance or suppress the observed nonlinearity.

Furthermore, in the context of nonlinear optics, higher hyperpolarizability values indicate stronger nonlinear optical responses, which translate to a greater ability of the material to alter its refractive index or absorb light under high-intensity excitation. As these molecules exhibit significant nonlinear optical responses, they can be effectively monitored using nonlinear optical techniques. The NLO-based techniques offer several advantages, including high spatial resolution, minimal photodamage, and deeper penetration, making them highly suitable for the monitoring and quantification of these molecules. Understanding the NLO properties of these molecules under fs excitation can thus aid in the development of advanced optical detection platforms for tracking these biomolecules in biological environments.

Molecular Docking

In addition to the nonlinear optical studies, we have performed molecular docking to investigate the interaction of serotonin and melatonin with their respective receptors. These molecules activate their receptors by binding to a specific site. Any alteration in the serotonin and melatonin-receptors cycle may lead to many pathological conditions such as depression, Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, and migraines99,100,101. The docking score (binding energy) and residue-specific interaction of the 7-family serotonin and melatonin receptor subtypes are provided in Table S2, along with their 2D and 3D interaction diagrams (Fig. S2(a-g). From Table S2, it is evident that 5HT2, 5HT4, 5HT6, and 5HT7 family receptor subtypes possess a binding affinity of ≥ −6.0 kcal/mol, whereas the rest of the family’s subtypes have ≤ −5.6 kcal/mol. 5HT1E and 5HT1F are the exceptions, which possess binding strengths of −6.0 and − 6.1 kcal/mol, respectively. Among all the serotonin receptor subtypes, 5HT2B possesses the highest binding strength of −7.0 kcal/mol (Fig. 9(a)). On the other hand, the melatonin receptor MT1 has the highest binding affinity, i.e.,−7.9 kcal/mol (Table S2, Fig. 9(b)) towards melatonin, followed by MT2, having a binding affinity of −6.0 kcal/mol (Table S2, Fig. S2(h)). A residue-wise description of interaction shows that hydrophobic interaction is predominant for each of the receptors. All these interaction types can be seen in the schematic interaction diagrams provided in the supplementary file. Understanding how serotonin and melatonin interact with their respective receptor subtypes provides intricate structural and functional insights for designing target-specific drugs to reduce the side effects and improve efficacy. Information regarding key residues and the exact orientation of serotonin and melatonin enables them to serve as templates for developing homologous series or modified structures as drug candidates. For instance, Lorcaserin, a selective 5-HT2C agonist, was crafted to treat obesity by exploiting receptor subtype differences102.

Conclusions

In summary, we provide a novel report on the fs-induced nonlinear optical properties of serotonin and melatonin at various concentrations through the CA and OA Z-scan techniques. Additionally, we have analyzed the frequency-dependent second-order hyperpolarizabilities at a wavelength of 530 nm using DFT and correlated these findings with Z-scan experimental data. The results are notably close to the experimental data. Under the specific experimental conditions employed in this study, both samples exhibit positive refractive and absorptive nonlinearities, which are attributed to phenomena such as self-focusing and the RSA effect, respectively. We found that n2 and β for serotonin in PBS buffer at a concentration of 150 mM are 3.865 × 10–19 m²/W and 1.343 × 10–12 m/W, respectively. For melatonin in DMSO at the same concentration (150 mM), the corresponding values are n2 = 3.417 × 10–19 m²/W and β = 1.355 × 10–12 m/W. The observed refractive nonlinearity is primarily influenced by electronic polarization, whereas the absorptive nonlinearity is attributed to the TPA process. Furthermore, we observed that the strength of refractive nonlinearity depends on the concentration, with the overall refractive nonlinearity being stronger for serotonin than melatonin. The difference in the nonlinear optical responses of serotonin and melatonin can be directly correlated with their molecular structures, where serotonin exhibits a planar structure that facilitates more efficient charge transfer through π-bond delocalization compared to melatonin. On the other hand, the absorptive nonlinearity did not exhibit any significant concentration-dependent trend. Investigating the nonlinear optical properties of serotonin and melatonin under fs excitation offers valuable insights into their electronic structure and nonlinear photophysical behaviour. These findings pave the way for exploring the molecular mechanisms behind neurological disorders associated with these neurotransmitters, potentially leading to new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Furthermore, several novel chemical reactivity descriptors have also been calculated to comprehend various aspects of pharmacological significance. Moreover, the docking analysis suggests a promising binding affinity between serotonin/melatonin and their respective receptors. Understanding the binding affinity to all receptors could be beneficial for drug development, enabling the design of molecules that selectively target specific receptors while avoiding others. This approach holds the potential for developing more effective and safer drugs that will prevent drug abuse and reduce the risk of drug addiction.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Amaral, F. G. D. & Cipolla-Neto, J. A brief review about melatonin, a pineal hormone. Archives Endocrinol. Metabolism. 62, 472–479. https://doi.org/10.20945/2359-3997000000066 (2018).

Back, K., Tan, D. X. & Reiter, R. J. Melatonin biosynthesis in plants: multiple pathways catalyze Tryptophan to melatonin in the cytoplasm or chloroplasts. J. Pineal Res. 61, 426–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpi.12364 (2016).

Chemchem, M., Chemchem, A., Aydıner, B. & Seferoğlu, Z. Recent advances in colorimetric and fluorometric sensing of neurotransmitters by organic scaffolds. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 244, 114820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114820 (2022).

Masters, A., Pandi-Perumal, S. R., Seixas, A., Girardin, J. L. & McFarlane, S. I. Melatonin, the hormone of darkness: from sleep promotion to Ebola treatment. Brain Disorders Therapy. 4, 1000151. https://doi.org/10.4172/2168-975x.1000151 (2014).

Ocana-Santero, G. et al. Perinatal serotonin signalling dynamically influences the development of cortical GABAergic circuits with consequences for lifelong sensory encoding. Nat. Commun. 16, 5203. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59659-5 (2025).

Di Giovanni, G. Serotonin in the pathophysiology and treatment of CNS disorders. Exp. Brain Res. 230, 371–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-013-3701-3 (2013).

van Zwieten, P. A. Pathophysiological relevance of serotonin. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 10 (Suppl 3), 19–25 (1987).

Borroto-Escuela, D. O. et al. The role of central serotonin neurons and 5-HT heteroreceptor complexes in the pathophysiology of depression: A historical perspective and future prospects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. (22 (4), 1661–6596 (2021).

Berger, M., Gray, J. A. & Roth, B. L. The expanded biology of serotonin. Annu. Rev. Med. 60, 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.med.60.042307.110802 (2009).

Young, S. N. & Leyton, M. The role of serotonin in human mood and social interaction: insight from altered Tryptophan levels. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 71, 857–865. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0091-3057(01)00670-0 (2002).

Harmer, C. J., Shelley, N. C., Cowen, P. J. & Goodwin, G. M. Increased positive versus negative affective perception and memory in healthy volunteers following selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake Inhibition. 161, 1256–1263, (2004). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1256

Kranz, G. S., Kasper, S. & Lanzenberger, R. Reward and the serotonergic system. Neuroscience 166, 1023–1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.01.036 (2010).

da Cunha-Bang, S. & Knudsen, G. M. The modulatory role of serotonin on human impulsive aggression. Biol. Psychiatry. 90, 447–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.05.016 (2021).

Blundell, J. E. Serotonin and appetite. Neuropharmacology 23, 1537–1551. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3908(84)90098-4 (1984).

Cowen, P. & Sherwood, A. C. The role of serotonin in cognitive function: evidence from recent studies and implications for Understanding depression. J. Psychopharmacol. 27, 575–583. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881113482531 (2013).

Sarrouilhe, D. & Mesnil, M. Serotonin and human cancer: A critical view. Biochimie 161, 46–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2018.06.016 (2019).

Balakrishna, P., George, S., Hatoum, H. & Mukherjee, S. Serotonin pathway in cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(3), 1268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22031268 (2021).

Mandić, A. D. et al. Clostridium ramosum regulates enterochromaffin cell development and serotonin release. Sci. Rep. 9, 1177. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-38018-z (2019).

Ivetic, N. et al. A platelet viability assay (PVA) for the diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Platelets 30, 1017–1021. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537104.2018.1562169 (2019).

Liu, X., Montemurro, M., Vanzo, N. & Crozatier, M. Serotonergic neurons regulate the drosophila vascular niche to control immune stress hematopoiesis. Nat. Commun. 16, 5152. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60493-y (2025).

Vikenes, K., Farstad, M. & Nordrehaug, J. E. Serotonin is associated with coronary artery disease and cardiac events. Circulation 100, 483–489. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.100.5.483 (1999).

Neumann, J., Hofmann, B., Dhein, S. & Gergs, U. Cardiac roles of serotonin (5-HT) and 5-HT-receptors in health and disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(5), 4765. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24054765 (2023).

Guicheney, P. et al. Platelet 5-HT content and uptake in essential hypertension: role of endogenous digitalis-like factors and plasma cholesterol. J. Hypertens. 6, 873–879. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004872-198811000-00005 (1988).

Kageyama, T., Seo, J., Yan, L., Hamano, S. & Fukuda, J. Serotonin activates dermal papilla cells and promotes hair growth. Sci. Rep. 15, 24525. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10716-5 (2025).

Srinivasan, V. et al. Melatonin and human reproduction: shedding light on the darkness hormone. Gynecol. Endocrinology: Official J. Int. Soc. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 25, 779–785. https://doi.org/10.3109/09513590903159649 (2009).

Lazar, R. et al. Afternoon to early evening bright light exposure reduces later melatonin production in adolescents. Npj Biol. Timing Sleep. 2 https://doi.org/10.1038/s44323-025-00040-6 (2025).

Tamanna, S. et al. Serum melatonin as a potential biomarker for COVID-19 severity. Sci. Rep. 15, 25720. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07170-8 (2025).

Auld, F., Maschauer, E. L., Morrison, I., Skene, D. J. & Riha, R. L. Evidence for the efficacy of melatonin in the treatment of primary adult sleep disorders. Sleep Med. Rev. 34, 10–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2016.06.005 (2017).

Jan, J. E., Espezel, H., Appleion, R. E. & THE TREATMENT OF SLEEP DISORDERS WITH MELATONIN. 36, 97–107, (1994). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.1994.tb11818.x

Hu, Z. P. et al. Melatonin ameliorates vascular endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and atherosclerosis by suppressing the TLR4/NF-κB system in high-fat-fed rabbits. J. Pineal Res. 55, 388–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpi.12085 (2013).

Wirtz, P. H., Spillmann, M., Bärtschi, C. & Ehlert, U. Känel, R. Oral melatonin reduces blood coagulation activity: a placebo-controlled study in healthy young men. J. Pineal Res. 44, 127–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00499.x (2008). von.

Srinivasan, V. et al. Therapeutic potential of melatonin and its analogs in parkinson’s disease: focus on sleep and neuroprotection. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 4, 297–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756285611406166 (2011).

Pandi-Perumal, S. R. et al. Melatonin antioxidative defense: therapeutical implications for aging and neurodegenerative processes. Neurotox. Res. 23, 267–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12640-012-9337-4 (2013).

Srinivasan, V., Pandi-Perumal, S. R., Cardinali, D. P., Poeggeler, B. & Hardeland, R. Melatonin in alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Behav. Brain Functions: BBF. 2, 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-9081-2-15 (2006).

Yong, W. et al. Roles of melatonin in the field of reproductive medicine. Biomed. Pharmacother. 144, 112001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112001 (2021).

Jiang, Y., Shi, H., Liu, Y., Zhao, S. & Zhao, H. Applications of Melatonin in Female Reproduction in the Context of Oxidative Stress. 6668365, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6668365 (2021).

Chattopadhyay, A., Rukmini, R. & Mukherjee, S. Photophysics of a neurotransmitter: ionization and spectroscopic properties of serotonin. Biophys. J. 71, 1952–1960. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79393-1 (1996).

Sarkar, P., Kumar, G. A., Pal, S. & Chattopadhyay, A. in In Serotonin. 3–22 (eds Pilowsky, P. M.) (Academic, 2019).

Sakshi, Swain, B. C., Das, A. K. & Tripathy, U. Probing third-order nonlinearity in serotonin: A Z-scan study. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 223, 117319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2019.117319 (2019).

Pathak, N. K., Sahoo, P. & Tripathy, U. Nonlinear study of indolamines: A hidden property that might have possible implications in neurodegeneration. Talanta 272, 125808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2024.125808 (2024).

Hernández-Mendoza, G. A. et al. Fluorescence of serotonin in the visible spectrum upon multiphotonic photoconversion. Biomed. Opt. Express. 11, 1432–1448. https://doi.org/10.1364/boe.380412 (2020).

Udenfriend, S., Bogdanski, D. F. & Weissbach, H. Fluorescence characteristics of 5-Hydroxytryptamine (Serotonin). 122, 972–973, doi: (1955). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.122.3177.972

Rath1, M. C., Mahal, H. S. & Mukherjee, T. Photophysics of melatonin in different environments. 69 294-300 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-1097.1999.tb03289.x (1999).

Bera, K. et al. Fluorogenic detection of monoamine neurotransmitters in live cells. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 9, 469–474. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00391 (2018).

Snyder, S. H., Axelrod, J. & Zweig, M. A sensitive and specific fluorescence assay for tissue serotonin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 14, 831–835. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-2952(65)90102-4 (1965).

Kubitschke, M. et al. Next generation genetically encoded fluorescent sensors for serotonin. Nat. Commun. 13, 7525. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35200-w (2022).

Khan, Z. A., Jung-Soo, H. P., Hayoung, L. C., Hong, Y. & and Recent advances in electrochemical and optical sensors for detecting Tryptophan and melatonin. Int. J. Nanomed. 16, 6861–6888. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S325099 (2021).

Fan, M. et al. Ratiometric SERS-based assay with sandwich structure for detection of serotonin. Microchim. Acta. 190, 100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00604-023-05634-0 (2023).

Moody, A. S. & Sharma, B. Multi-metal, Multi-wavelength Surface-Enhanced Raman spectroscopy detection of neurotransmitters. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 9, 1380–1387. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00020 (2018).

Duhan, J., Kumar, H. & Obrai, S. Recent advances in nanomaterials based optical sensors for the detection of melatonin and serotonin. J. Fluoresc. 35, 1315–1333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10895-024-03647-3 (2025).

Sasa, S. & Blank, C. L. Determination of serotonin and dopamine in mouse brain tissue by high performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Anal. Chem. 49, 354–359. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac50011a008 (1977).

Rocher, C. et al. Microdialysis monitoring of variations in extracellular levels of serotonin, GABA and excitatory amino acids in the frontal cortex of awake rats in response to a single peripheral or central administration of Dexfenfluramine. Brain Res. 737, 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(96)00735-4 (1996).

Zhao, S. & Piatkevich, K. D. Techniques for in vivo serotonin detection in the brain: state of the Art. J. Neurochem. 166, 453–480. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.15865 (2023).

Slifstein, M. & Abi-Dargham, A. Detecting Pharmacologically induced serotonin release in depression with positron emission tomography imaging: A new approach. Biol. Psychiatry. 93, 1056–1058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2023.04.008 (2023).

Min, J. et al. Continuous biochemical profiling of the Gastrointestinal tract using an integrated smart capsule. Nat. Electron. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-025-01407-0 (2025).

Zhao, C. et al. Implantable aptamer–field-effect transistor neuroprobes for in vivo neurotransmitter monitoring. 7, eabj7422, doi: (2021). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abj7422

Mao, L., Han, Y., Zhang, Q. W. & Tian, Y. Two-photon fluorescence imaging and specifically biosensing of norepinephrine on a 100-ms timescale. Nat. Commun. 14, 1419. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36869-3 (2023).

Xiao, Y., Deng, P., Zhao, Y., Yang, S. & Li, B. Three-photon excited fluorescence imaging in neuroscience: From principles to applications. Volume 17– (2023). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2023.1085682 (2023).

Yang, S. J., Del Bonis-O’Donnell, J. T., Beyene, A. G. & Landry, M. P. Near-infrared catecholamine nanosensors for high Spatiotemporal dopamine imaging. Nat. Protoc. 16, 3026–3048. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-021-00530-4 (2021).

Maity, B. K. & Maiti, S. Label-free imaging of neurotransmitters in live brain tissue by multi-photon ultraviolet microscopy. Neuronal Signal. 2 https://doi.org/10.1042/ns20180132 (2018).

Maiti, S., Shear, J. B., Williams, R. M., Zipfel, W. R. & Webb, W. W. Measuring serotonin distribution in live cells with Three-Photon excitation. 275, 530–532, (1997). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.275.5299.530

Sheik-Bahae, M., Said, A. A., Wei, T. H., Hagan, D. J. & Stryland, E. W. V. Sensitive measurement of optical nonlinearities using a single beam. IEE J. Quantum Electron. 26, 760–769. https://doi.org/10.1109/3.53394 (1990).

Ganeev, R. A. et al. Nonlinear refraction in CS2. Appl. Phys. B. 78, 433–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00340-003-1389-y (2004).

Tripathy, U. & Bisht, P. B. Influence of pulsed and Cw pumping on optical nonlinear parameters of laser dyes probed by a closed-aperture Z-scan technique. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B. 24, 2147–2156. https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSAB.24.002147 (2007).

Sakshi, Swain, B. C., Das, A. K., Pathak, N. K. & Tripathy, U. Z-scan analysis and theoretical studies of dopamine under physiological conditions. Spectrochim. Acta A. 271, 120890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2022.120890 (2022).

Tripathy, U. & Bisht, P. B. Simultaneous Estimation of optical nonlinear refractive and absorptive parameters by solvent induced changes in optical density. Opt. Commun. 261, 353–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optcom.2005.12.012 (2006).

Ghosh, S. et al. A novel tool to investigate the early and late stages of α-Synuclein aggregation. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 11, 1610–1619. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00068 (2020).

Sakshi, Swain, B. C., Das, A. K., Pathak, N. K. & Tripathy, U. Norepinephrine exhibits thermo-optical nonlinearity under physiological conditions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 23, 23473–23477. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1CP03534G (2021).

Pathak, N. K., Sharma, L., Sakshi, Panda, B. & Tripathy, U. Synthesis, characterization, and investigation of nonlinear property of fly ash-red mud-Ag: A low-cost sustainable nanocomposite. Opt. Mater. 126, 112230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2022.112230 (2022).

Sahoo, P., Pathak, N. K., Scott Bohle, D., Dodd, E. L. & Tripathy, U. Hematin anhydride (β-hematin): an analogue to malaria pigment hemozoin possesses nonlinearity. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 310, 123902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2024.123902 (2024).

Pal, I. et al. Solvent-Driven Variations of Third-Order Nonlinear Thermo-Optical Features of Glutaric Acid-Directed Self-Healing Supramolecular Ni(II) Metallogels. Langmuir 39, 16584–16595, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.3c02572

Pradhan, A. K., Kumar, S., Ballav, S., Priyam, A. & Datta, P. K. Plasmon-enhanced optical nonlinearity in pyramidal silver nanocrystals. Opt. Lett. 49, 5985–5988. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.541804 (2024).

Paul, D. et al. Revealing the importance of the C(1) position to modulate the photophysics and Z-scan responses of o-locked GFP chromophores. J. Chem. Phys. 162 https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0274692 (2025).

Pradhan, A. K. et al. Intensity-driven resurgence of reverse saturable absorption and vibrational modes in hexagonal silver nanoplates. J. Mater. Chem. C. 13, 12013–12023. https://doi.org/10.1039/D5TC00212E (2025).

Hanczyc, P., Samoc, M. & Norden, B. Multiphoton absorption in amyloid protein fibres. Nat. Photonics. 7, 969–972. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2013.282 (2013).

de Freitas, M. C. P. et al. Z-Scan analysis: a new method to determine the oxidative state of Low-Density lipoprotein and its association with multiple cardiometabolic biomarkers. Braz. J. Phys. 46, 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13538-015-0395-y (2016).

Alves, S. et al. Application of Z-scan technique in detecting Circulating free DNA for prostate cancer diagnosis and monitoring. Lasers Med. Sci. 40, 114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-025-04357-3 (2025).

Yin, M., Li, H., Tang, S. & Ji, W. J. Determination of nonlinear absorption and refraction by single Z-scan method. P B. 70, 587–591 (2000).

Ali, M. et al. Measuring the nonlinear optical properties of indium Tin oxide thin film using femtosecond laser pulses. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B. 37, A139–A146. https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSAB.396327 (2020).

Sutherland, R. L. Handbook of Nonlinear Optics (Taylor & Francis, 2003).

Mathew, E., Salian, V. V., Hubert Joe, I. & Narayana, B. Third-order nonlinear optical studies of two novel chalcone derivatives using Z-scan technique and DFT method. Opt. Laser Technol. 120, 105697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2019.105697 (2019).

Ayare, N. N. et al. Z-scan and DFT approach for investigating the NLO properties of imidazole fused anthraquinone dyes. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A. 390, 112327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2019.112327 (2020).

Shinde, S. S. et al. DFT and Z-scan approach to study linear and nonlinear optical properties of disperse red 277. Opt. Mater. 99, 109536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2019.109536 (2020).

Eberhardt, J., Santos-Martins, D., Tillack, A. F. & Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: new Docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 61, 3891–3898. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00203 (2021).

Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock vina: improving the speed and accuracy of Docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455–461. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21334 (2010).

Ravikumar, C., Joe, I. H. & Jayakumar, V. S. Charge transfer interactions and nonlinear optical properties of push–pull chromophore benzaldehyde phenylhydrazone: A vibrational approach. Chem. Phys. Lett. 460, 552–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2008.06.047 (2008).

Padmaja, L. et al. Density functional study on the structural conformations and intramolecular charge transfer from the vibrational spectra of the anticancer drug combretastatin-A2. J. Raman Spectrosc. 40, 419–428. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrs.2145 (2009).

Valverde, C. et al. Third-Order nonlinear optical properties of a carboxylic acid derivative. Acta Chim. Slov. 65, 739–749 (2018).

Mary, Y. S. et al. Molecular conformational analysis, vibrational spectra, NBO, NLO analysis and molecular Docking study of bis[(E)-anthranyl-9-acrylic]anhydride based on density functional theory calculations. Spectrochim Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 151, 350–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2015.06.075 (2015).

Borah, M. M. & Devi, T. G. Vibrational study and natural bond orbital analysis of serotonin in monomer and dimer States by density functional theory. J. Mol. Struct. 1161, 464–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.02.055 (2018).

Rath1, M. C., Mahal, H. S. & Mukherjee, T. Photophysics of melatonin in different environments. Photochem. Photobiol. 69, 294–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-1097.1999.tb03289.x (1999).

Lankford, J. I. & Criss, C. M. Partial molar heat capacities of selected electrolytes and benzene in methanol and dimethylsulfoxide at 25, 40, and 80°C. J. Solution Chem. 16, 885–906. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00650993 (1987).

Zhou, J. C., Che, Y. Y., Wu, K. J., Shen, J. & He, C. H. Thermal conductivity of DMSO + C2H5OH, DMSO + H2O, and DMSO + C2H5OH + H2O mixtures at T = (278.15 to 338.15) K. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 58, 663–670. https://doi.org/10.1021/je301171y (2013).

Jamal, M. A. et al. Investigations to explore molecular interactions and sweetness response of polyhydroxy compounds with amino acids in aqueous systems. ACS Omega. 7, 40950–40962. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c04102 (2022).

Boyd, R. W. in In Nonlinear Optics (Third Edition). 207–252 (eds Boyd, R. W.) (Academic, 2008).

Wei, J., Yang, J., Yang, L., Li, Y. & Song, Y. Nonlinear absorption and optical limiting performance of broad-band multi-branched aniline derivatives in the near-infrared region. Dyes Pigm. 222, 111876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dyepig.2023.111876 (2024).

Baluja, S., Talaviya, R. M. & Density Sound speed, and viscosity of dihydropyridine derivatives in dimethyl sulfoxide at different temperatures. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 61, 1431–1440. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jced.5b00627 (2016).

Ali, H., Anjum, A. & Goswami, D. Investigating the third-order nonlinear optical properties of a schiff base (DBAP) and its co/cu metal complex using Z-scan and DFT methodology. J. Mol. Struct. 1307, 138039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.138039 (2024).

Dresler, T. et al. Understanding the nature of psychiatric comorbidity in migraine: a systematic review focused on interactions and treatment implications. J. Headache Pain. 20 https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-019-0988-x (2019).

Morera-Fumero, A. L. & Abreu-Gonzalez, P. Role of melatonin in schizophrenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 9037–9050. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14059037 (2013).

Cardinali, D. P., Furio, A. M. & Brusco, L. I. Clinical aspects of melatonin intervention in alzheimer’s disease progression. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 8, 218–227. https://doi.org/10.2174/157015910792246209 (2010).

Higgins, G. A. et al. The 5-HT2C receptor agonist Lorcaserin reduces nicotine Self-Administration, discrimination, and reinstatement: relationship to feeding behavior and impulse control. Neuropsychopharmacology 37, 1177–1191. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2011.303 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB), DST, New Delhi, India (EMR/2017/003759) for financial assistance. The authors thank the UPM (SGDRI) project of IIT Kharagpur for providing the femtosecond laser facility. We are also thankful to Prof. Sridhar Sahu, IIT (ISM), Dhanbad, for providing us with the computational facility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Nitesh Kumar Pathak: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.Nandeshwar: Writing - Review & Editing, Investigation, Validation, Formal analysis.Priyadarshi Sahoo: Writing - Review & Editing, Investigation, Validation, Formal analysis.Amit Kumar Pradhan: Investigation, Validation, Formal analysis.Tara Singha: Investigation, Validation, Formal analysis.Prasanta Kumar Datta: Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition.Umakanta Tripathy: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions