Abstract

Bacterial infections are among the foremost causes of morbidity and mortality on a global scale. In this study, TiO2 layers were performed on Ti45Nb alloys by anodic oxidation (AO) process with low voltages. Thus, the aim of this research is to investigate the surface properties, wettability and antimicrobial properties of TiO2 layers fabricated at low AO voltages on Ti45Nb alloy. The phase structures, morphologies and elemental amounts and distribution of the surfaces were characterized by XRD, Micro-Raman, SEM and EDX. The existence of anatase-TiO2 was verified on AO layer on Ti45Nb alloy. The wettability of AO layers improved with increasing AO voltage and the surfaces became more and more hydrophilic with increasing voltage. For Escherichia coli as Gram-negative and Staphylococcus aureus as Gram-positive, the counting of both bacteria on TiO2 layers was less than ones on uncoated Ti45Nb. Moreover, the number of bacteria on the surface increased in direct proportion to the wettability result and increasing AO voltage. The AO layers produced at 25 V indicated maximum inhibition ratio. They inhibited both bacteria at the ratio of 93.3% (E. coli) and 96.7% (S. aureus).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent decades, titanium (Ti)-based materials have emerged as the predominant metallic materials utilized in the fabrication of load-bearing medical implants within the domains of orthopedics and dental surgery1,2,3. Titanium alloys are the preferred material due to their superior specific strength, corrosion resistance and biocompatibility when compared with 316 L stainless steels and cobalt-chromium (Co-Cr) alloys4,5. However, in recent years, the widespread use of Ti6Al4V alloy has been called into question on the basis of reports of vanadium as a potential cytotoxic element responsible for the occurrence of neurological disorders and allergic reactions6,7. Consequently, research in the field of biomedical implant materials is focused on the development of a new generation of β-type Ti-based alloys containing only non-harmful elements such as molybdenum (Mo)8tantalum (Ta)9zirconium (Zr)10 and niobium (Nb)11. These β-type Ti alloys exhibit low elastic modulus and good corrosion resistance, mechanical properties and biocompatibility. Consequently, they have become increasingly important for biomedical applications in comparison to other Ti alloys12.

The utilization of Nb alloys has been demonstrated to enhance the passivation behavior of the surface, achieved by decreasing the anion vacancy concentration within the protective layer of titanium oxide. Consequently, the most prevalent β-titanium alloys in recent years are Nb alloys, including Ti45Nb13,14. Furthermore, Nb is non-toxic. β-TiNb alloys are distinguished by their mechanical properties, particularly their lower Young’s modulus value when compared to Ti6Al4V. This characteristic renders them well-suited for utilization as implant materials15. Nb metals exhibit biological activity and have the capacity to bind biologically to bone16. However, the bio-inert nature of Ti has been demonstrated to differentiate osteogenesis-related cells. In the final analysis, this engenders inadequate osseointegration between the implant interface and the bone tissue17,18. Another important health risk is microbial colonization for implant applications, which can occur when microbes attach to the implant and begin to grow, potentially leading to infection or other health complications19,20,21. Consequently, there is a necessity to enhance the bioactivity and antimicrobial activity of Ti-based implants.

Surface modification processes improve the osseointegration, bioactivity and antimicrobial properties of the implant materials. A few surface modification processes such as micro arc oxidation1,13,22 and sol-gel23 have been employed to activate the Ti45Nb alloys so far, and these processes are expected to continue to be used in future. Anodic oxidation has been demonstrated to be a process that offers certain advantages, primarily due to its relatively low production cost and the ease with which it can be used to produce anodisation solutions with a variety of properties. It is evident that this method is to be preferred over other methods24.

There are many literature works about AO coatings on cp-Ti, Ti6Al4V and other Ti alloys25,26,27,28,29. However, the investigation about AO coatings on Ti45Nb alloy is very limited. Zorn et al. examined oxide formation mechanism on Ti45Nb at high voltages30. Senaslan et al. investigated wear resistance of nano/microporous TiO2 layer on Ti45Nb alloy at high voltages from 150 V to 300 V31. Acar et al. evaluated surface wettability and corrosion resistance of TiO2 nanotubes fabricated on Ti45Nb at high voltages such as 150 V and 200 V32. However, there is no report on fabrication, wettability and antimicrobial activity of TiO2 layer on Ti45Nb alloy at low voltages up to 100 V.

Thus, the aim of this work is to investigate surface properties, wettability and antimicrobial activity of TiO2 layer on Ti45Nb alloy at low voltages up to 100 V. In this work, TiO2 layers was fabricated on Ti45Nb alloy at low voltages was characterized by X-ray diffractometer (XRD), Raman spectrometer, scanning electron microscope (SEM), energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDX) and contact angle goniometer. Moreover, the antimicrobial activity of the surfaces was examined using the bacteria count method against two types of bacteria: Escherichia coli (E. coli: Gram-negative) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus: Gram-positive).

Experimental details

Metallographic preparations

In the present study, the authors utilized Ti45Nb rectangular-shaped substrates, measuring 10 mm × 10 mm × 3 mm, for the AO process. The Ti45Nb surfaces were then ground using sandpaper with grit levels ranging from 180 to 2000-grade SiC. Subsequently, all ground substrates were immersed in an acetone-based electrolyte and subjected to an ultrasonic cleaning bath. The final stage of the process involved desiccation, which was achieved by means of a heat gun. The items were then stored in a desiccator.

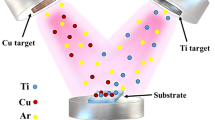

Anodic oxidation (AO) process

Rectangular Ti45Nb substrates were coated in NH4F (0.2 M), (NH4)2SO4 (1 M) and a deionized water-based solution below 30 °C using a direct current (DC) power supply (GW Instek PSU 400) by the anodic oxidation (AO) process, as schematically illustrated in Fig. 1. Ti45Nb substrates and Pt sheets were used as the anode and cathode, respectively. The AO process was conducted at 25 V, 50 V, 75 V and 100 V for 1 h. Subsequent to the AO process, which was undertaken to effect the transformation from amorphous to crystalline form, the heat treatment was applied to the AO surfaces at 450 °C for 1 h.

Characterization techniques

In order to determine the TiO2 structures fabricated at different voltages on the surface of samples, an investigation was conducted into the phase structures of all surfaces, with XRD (GNR Europe 600) analysis utilizing Cu-Kα radiation, at a scanning speed of 1° min−1 extending from 20° to 90°. Raman analyses were performed using a WITech alpha 300R micro-Raman spectrometer and a laser with a wavelength of λ = 532 nm was used in the analyses. The surface morphologies of the uncoated Ti45Nb and the AO layers were monitored by a scanning electron microscope (SEM: Quanta FEG 250). The elemental quantities on the surfaces were evaluated by EDX, which was attached to the SEM. For the purpose of contact angle measurements, 1µL of de-ionized water was deposited onto the surfaces. The mean contact angle (CA) values were examined within 60° using a sessile drop technique contact angle goniometer (Dataphysics OCA 15EC). The Neumann method is predicated on the assumption that there is a correlation between the surface free energy (SFE) of a solid (γS), the SFE of a liquid in contact with the solid surface (γL), and the SFE of the solid–liquid interface (γSL). This correlation can be expressed in a general form by the following state Eq. (1):

The SFE calculations were performed by the measurements of ACA values for deionized water. Subsequently, the Neumann method was employed to ascertain the surface energy (γS) in accordance with the equation of state. The final form of the equation is presented below Eq. (2)33:

where β = 0.0001247 (m2/mJ)2, γL = 72.8 mJ/m2 and θ (contact angle) are known for each sample. Numerical iteration was required in order to solve the Neumann equation.

Antimicrobial properties

Escherichia coli (E. coli: Gram-negative) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus: Gram-positive) are the two most common infectious bacteria and were utilized as model bacteria to study the antimicrobial behavior of uncoated Ti45Nb and AO layers. In order to ascertain the extent of microbial adhesion to the surfaces of all uncoated Ti45Nb and AO layers, it was necessary to immerse all surfaces in 5.0 mL of a bacterial suspension (1 × 108 CFU/mL). The interaction between the uncoated Ti45Nb/AO surface and the bacteria was then maintained at 37 °C for a period of 24 h. Subsequent to this incubation period, all uncoated Ti45Nb and AO coated samples were washed with phosphate buffer. In order to obtain bacteria adhering to the surface, all uncoated and coated surfaces transferred to sterile tubes were vortexed in physiological solution for 2 min and 100 µL of the solution was inoculated onto Mueller-Hinton agar plates. Following a 48 h incubation period at a temperature of 37 °C, the bacterial colonies were enumerated in accordance with the established literature protocols34. In order to guarantee the reliability of the experimental results, each experiment was carried out in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted utilizing the software program IBM SPSS Statistics 22 SP, with all results expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. A p-value of less than 0.05 was deemed to be statistically significant.

Result and discussion

XRD spectra of uncoated Ti45Nb and AO coatings produced at various voltages were seen in Fig. 2. Only, β-Ti (β-Ti: #96-900-8555) peaks on uncoated Ti45Nb surface were detected at around 38.43°, 55.59°, 69.79° and 82.74°. In addition to β-Ti peaks, anatase-TiO2 (A: #96-900-8217) and TiO2 (T: #96-153-2820) peaks on AO coatings were observed at 24.67° and 26.71°, respectively. The intensity of the β-Ti peaks decreased with increasing AO voltage, while the peaks became broader. This is the result of the Ti peaks being dominated by the increase of the oxide layer with increasing voltage. Also, it has been demonstrated that an increase in voltage results in greater oxygen entering the surface, and in turn, more oxides such as are formed by electrochemical reactions. Consequently, the intensity of oxides such as A and T on the surface is found to increase with increasing voltage.

Micro Raman spectra of AO coatings formed on Ti45Nb samples are shown in Fig. 3. When the figure is examined, it is seen that Anatase (A) peaks at around 141, 398, 525, 640 cm−1 have been observed in all samples35,36. It is also seen in the figure that as the anodization voltage increases, the peaks become narrower. This is especially evident for the peak observed at around 141 cm−1. As is known, sharp and narrow peaks indicate a crystalline structure, while broad peaks mean that the structure may be amorphous. Therefore, it is understood that TiO2 coatings tend to transform from amorphous to crystalline structure due to increasing anodization voltage1.

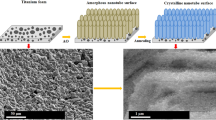

Surface morphologies of uncoated Ti45Nb alloy and AO coatings produced at various voltages were monitored by SEM as shown in Fig. 4. The grinding process was carried out to facilitate the formation of TiO2 layer by AO process. Thus, there are many parallel worn tracks on uncoated Ti45Nb alloy due to the sample preparation process by SiC paper at pre-AO coating process (Fig. 4a). At post-AO coating process, the worn tracks on Ti45Nb alloy were eliminated by TiO2 layer (Fig. 4b and e). In addition, nano-/micro-porous and crack structures were observed through TiO2 layer surface at all voltages. The cracks observed in AO coatings produced at different voltages may be due to the effect of stresses in the brittle TiO2 structure. The sizes of pore structures increased with increasing voltage from 25 V to 100 V. In this study, the formation of nano-tubular structure on the surface of Ti45Nb alloy at all potential values was prevented by using glycerin based electrolyte. The process of film formation is comprised of the following steps. Initially, the native TiO2 particles undergo growth and coalescence, resulting in the formation of a smooth region (Fig. 2(b)). Subsequent to this process, some regions undergo a transformation, manifesting fissures and acquiring a porous nature. With an increase in voltage, the film undergoes a process of local disintegration, with the original and modified film regions developing in tandem. As the voltage increases, the modified regions expand, encompassing a greater proportion of the surface area. The resulting film is characterized by a combination of flat and porous regions. In circumstances where the anodic voltage is elevated, the formation of a TiO2 film is observed. This phenomenon is attributable to the migration of O2− ions to the metal/film interface, concomitant with the migration of Ti4+ ions from the metallic Ti to the film/electrolyte interface. A plethora of reactions occur during the process, with the most pertinent reactions in terms of film growth being those that result in O2 and TiO237.

EDX-mapping images of uncoated Ti45Nb alloy and AO layer produced at various voltages were illustrated in Fig. 5. Ti, Nb and O elements were monitored on AO coatings while Ti and Nb elements were observed on uncoated Ti45Nb substrate. In view of EDX-mapping images, all detected elements were homogenously distributed through whole surfaces. In addition to EDX-mapping images, the amounts of these detected elements were given in Table 1. The wt% amount of Ti and Nb was measured as 53.5 and 46.5 on Ti45Nb alloy, respectively. The difference of wt% of 1.5 is standard deviations of EDX-area analysis. Furthermore, as more oxygen reacts with the substrate during the AO process, the amount of element O increased with increasing AO voltage. Conversely, the quantity of Ti and Nb elements scanned diminished progressively as the coating layer expanded with elevated oxygen content.

Contact angle images, average contact angle (θ, CA) and surface free energy (γs, SFE) values of uncoated Ti45Nb alloy and AO layer produced at various voltages were given in Fig. 6; Table 2. CA results give information about wettability such as hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity. If the CA value is greater than 90°, the surface is hydrophobic. Similarly, if it is less than 90°, it shows hydrophilic properties38. According to the results, all uncoated Ti45Nb and AO layer surfaces indicated hydrophilic behavior. CA value of uncoated Ti45Nb was obtained as 61.4° ± 1.0°. CA values of AO surfaces decreased with increasing AO voltages. Moreover, the surfaces are indicated more and more hydrophilic property compared to uncoated Ti45Nb alloy and the coatings produced at low voltage. This can be explained the existence of TiO2 layer and hydroxyl groups on the surfaces. After the AO process, TiO2 layers were coated on Ti45Nb alloys surface. Moreover, the amount/intensity TiO2 layers enhance with increasing AO voltage. Depending on TiO2 layers, the hydroxyl groups naturally formed on the surface after AO process. It is well known that the hydroxyl groups possess highly polarity. The polarity is beneficial for hydrophilic properties since the interactions of hydroxyl groups and water molecules facilitate. The presence of hydroxyls and water molecules is indicated. Hydroxyl groups have the capacity to form hydrogen bonds with water molecules. This results in a stronger interaction between water molecules and the solid surface, which consequently leads to a reduction in the contact angle39. Thus, the hydroxyl groups formed on AO surfaces improve the wettability and hydrophilicity.

The antimicrobial activities of all surfaces were determined by counting the colonies formed on the Mueller-Hinton agar plates after re-culturation. Antimicrobial activities of uncoated Ti45Nb and AO coated TiO2 layers produced at various voltages against E. coli and S. aureus are indicated in Figs. 7 and 8, respectively. Compared to uncoated Ti45Nb surface, the number of E. coli colonies decreased between 46.7% and 93.3% on the AO surfaces produced at various voltages. In addition, compared to uncoated Ti45Nb surface, the number of S. aureus colonies decreased between 47.1% and 96.7% on the AO surfaces produced at various voltages. For both bacteria types, the strongest antimicrobial activity was obtained on AO layer produced at 25 V. Furthermore, AO layers with respect to S. aureus indicated greater antimicrobial activities than one to E. coli as seen in Table 3. It is clear that the antimicrobial activities for both bacteria types change depending on voltage through AO process. In view of these results, there are two possible reasons for enhancing antimicrobial activity of AO coated surfaces compared to uncoated Ti45Nb alloy. The first possible reason is that the results of the antimicrobial activity test are consistent with those of the contact angle measurement. It was demonstrated that an increase in voltage resulted in a decrease in contact angle and an increase in hydrophilicity of AO surfaces. The majority of a bacterial cell is composed of water (70–90%). The remaining 10–30% of the sample contains varying proportions of functional and structural molecules40. The quantity of bacteria adhering to the surface exhibited a direct proportionality to the decrease in the contact angle of the surfaces. It is well known that increased wettability provide antimicrobial activity41. These results are consistent with other literature studies. Eventually, antimicrobial activities of AO layers were improved from 100 V to 25 V for both bacteria types. Another possible antimicrobial activity reason is the existence of TiO2 phase on the surface. The photo catalytic process of TiO2 involves the formation of electron-hole pairs at post-exposed to light. Aggressive oxygen radicals are produced by electron attack, and the hole accelerates hydroxyl radical formation. These radicals ultimately attack bacteria or viruses by inhibiting the process of DNA cloning42. Moreover, it is well known that naturally formed passive TiO2 layer (∼3–10 nm) existed on Ti and its alloys43. However, antibacterial ability of this passive layer is very low since the photo catalytic effect is weak. Only, this layer provides passivation.

Conclusions

In this study, the fabrication of TiO2 layers was performed on Ti45Nb alloy at low voltages up to 100 V. The surface properties, wettability and antimicrobial properties of the anodic oxide TiO2 layers were investigated in detail. The anatase-TiO2 and TiO2 phases formed on Ti45Nb alloy from 25 V to 100 V and the amount of them increased with increasing voltage values. Moreover, micro-Raman verified the existence of anatase-TiO2 phase for all voltage values. The TiO2 layer morphologies were observed on AO coatings produced at low voltages. All elements such as Ti, Nb and O were homogenously distributed through whole surface. The wettability of AO layers improved with increasing AO voltage and the surfaces became more and more hydrophilic with increasing voltage. For Escherichia coli as Gram-negative and Staphylococcus aureus as Gram-positive, the counting of both bacteria on TiO2 layers was less than ones on uncoated Ti45Nb. The number of bacteria on the surface increased in direct proportion to the wettability result and increasing AO voltage.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kovacı, H., Şenel, K., Acar, M. T., Bozkurt, Y. B. & Çelik, A. Comparative investigation of structural, morphological, mechanical, tribological and electrochemical properties of TiO2 films formed on Cp-Ti, Ti6Al4V and Ti45Nb alloys. Surf. Coat. Technol. 487, 131024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2024.131024 (2024).

Han, J. et al. The current status of stimuli-responsive nanotechnologies on orthopedic titanium implant surfaces. J. Nanobiotechnol. 21, 277. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-023-02017-8 (2023).

Pandey, L. M. Design of biocompatible and self-antibacterial titanium surfaces for biomedical applications. Curr. Opin. Biomedical Eng. 25, 100423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobme.2022.100423 (2023).

Niinomi, M. Recent research and development in titanium alloys for biomedical applications and healthcare goods. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 4, 445–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stam.2003.09.002 (2003).

Aslan Çakır, M. Investigations of the wettability and electrochemical corrosion behavior of Nb2O5 thin films on a Ti45Nb alloy. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 32, 9198–9205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-023-08655-1 (2023).

Geetha, M., Singh, A. K., Asokamani, R. & Gogia, A. K. Ti based biomaterials, the ultimate choice for orthopaedic implants - A review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 54, 397–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmatsci.2008.06.004 (2009).

Li, Y., Wong, C., Xiong, J., Hodgson, P. & Wen, C. Cytotoxicity of titanium and titanium alloying elements. J. Dent. Res. 89, 493–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034510363675 (2010).

Xu, J. et al. Preparation and bioactive surface modification of the microwave sintered porous Ti-15Mo alloys for biomedical application. Sci. China Mater. 61, 545–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40843-017-9098-2 (2018).

García-Robledo, H. et al. Ti/Ta-based composite polysaccharide scaffolds for guided bone regeneration in total hip arthroplasty. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 271, 132573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.132573 (2024).

Kim, K. M. et al. Synthesis and characterization of a Ti–Zr-Based alloy with ultralow young’s modulus and excellent biocompatibility. Adv. Eng. Mater. 24, 2100776. https://doi.org/10.1002/adem.202100776 (2022).

Cvijović-Alagić, I., Rakin, M., Laketić, S. & Zagorac, D. Microstructural study of Ti45Nb alloy before and after HPT processing using experimental and Ab initio data mining approach. Mater. Charact. 169, 110635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2020.110635 (2020).

Sharan, J., Lale, S. V., Koul, V., Mishra, M. & Kharbanda, O. P. An overview of surface modifications of titanium and its alloys for biomedical applications. Trends Biomaterials Artif. Organs. 29, 176–187 (2015).

Tasdemir, M. & Alsaran, A. Tribocorrosion behaviour of porous anatase and rutile phases formed on surface of anodised Ti45Nb alloy. Lubr. Sci. 32, 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1002/ls.1495 (2020).

More, N. S., Diomidis, N., Paul, S. N., Roy, M. & Mischler, S. Tribocorrosion behavior of β titanium alloys in physiological solutions containing synovial components. Mater. Sci. Eng. C-Materials Biol. Appl. 31, 400–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2010.10.021 (2011).

Jirka, I. et al. On the role of Nb-related sites of an oxidized β-TiNb alloy surface in its interaction with osteoblast-like MG-63 cells. Mater. Sci. Engineering: C. 33, 1636–1645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2012.12.073 (2013).

Tan, J. et al. Accelerated fracture healing by osteogenic Ti45Nb implants through the PI3K–Akt signaling pathway. Bio-Design Manuf. 6, 718–734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42242-023-00250-6 (2023).

Tao, B. et al. Regulation of TiO2 nanotubes on titanium implants to orchestrate osteo/angio-genesis and osteo-immunomodulation for boosted osseointegration. Mater. Design. 233, 112268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2023.112268 (2023).

Chen, L. et al. Synergistic effects of immunoregulation and osteoinduction of ds-block elements on titanium surface. Bioactive Mater. 6, 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.08.001 (2021).

Cardoso, G. C. et al. Silver containing antimicrobial coatings on innovative Ti-30Nb-5Mo β-Alloy prepared by Micro-Arc oxidation for biomedical implant applications. Coatings 14, 214 (2024).

Jairam, S. A review on biomedical and dental applications of cerium oxide nanoparticles ― unearthing the potential of this rare Earth metal. J. Rare Earths. 41, 1645–1661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jre.2023.04.009 (2023).

Ashok, D. et al. Superhydrophobic surfaces to combat bacterial surface colonization. Adv. Mater. Interfaces. 10, 2300324. https://doi.org/10.1002/admi.202300324 (2023).

Vangolu, Y. S. et al. Tribocorrosion and antibacterial behaviour of boron-embedded oxide coated Ti45Nb by plasma electrolytic oxidation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 709, 163668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2025.163668 (2025).

Çomaklı, O., Yazıcı, M., Demir, M., Yetim, A. F. & Çelik, A. Effect of bilayer numbers on structural, mechanical, tribological and corrosion properties of TiO2–SiO2 multilayer film-coated β-type Ti45Nb alloys. Ceram. Int. 49, 3007–3015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.09.285 (2023).

Hou, X., Aitola, K. & Lund, P. D. TiO2 nanotubes for dye-sensitized solar cells—A review. Energy Sci. Eng. 9, 921–937. https://doi.org/10.1002/ese3.831 (2021).

Durdu, S. et al. Surface characterization and antibacterial efficiency of well-ordered TiO2 nanotube surfaces fabricated on titanium foams. Sci. Rep. 14, 618. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51339-6 (2024).

Durdu, S., Atasoy, S., Aktas, S., Yalcin, E. & Cavusoglu, K. Surface characterization and antibacterial efficiency of TiO2 nanotubes on Ti15Mo alloy. Surf. Innovations. 12, 504–512. https://doi.org/10.1680/jsuin.24.00042 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Anodic growth of TiO2 nanotube arrays: effects of substrate curvature and residual stress. Surf. Coat. Technol. 469, 129783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2023.129783 (2023).

Rios, J. et al. Self-organized TiO2 nanotubes on Ti-Nb-Fe alloys for biomedical applications: synthesis and characterization. Electrochem. Commun. 138, 107280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elecom.2022.107280 (2022).

Durdu, S. et al. Characterization and investigation of properties of copper nanoparticle coated TiO2 nanotube surfaces on Ti6Al4V alloy. Mater. Chem. Phys. 292, 126741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2022.126741 (2022).

Zorn, G., Lesman, A. & Gotman, I. Oxide formation on low modulus Ti45Nb alloy by anodic versus thermal oxidation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 201, 612–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2005.12.009 (2006).

Şenaslan, F., Taşdemir, M., Çelik, A. & Bozkurt, Y. B. Enhanced wear resistance and surface properties of oxide film coating on biocompatible Ti45Nb alloy by anodization method. Surf. Coat. Technol. 469, 129797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2023.129797 (2023).

Acar, M. T., Kovacı, H. & Çelik, A. Comparison of the structural properties, surface wettability and corrosion resistance of TiO2 nanotubes fabricated on Cp-Ti, Ti6Al4V and Ti45Nb. Mater. Today Commun. 33, 104396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2022.104396 (2022).

Li, D. & Neumann, A. W. Equation of state for interfacial tensions of solid-liquid systems. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 39, 299–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8686(92)80064-5 (1992).

Aktug, S. L., Durdu, S., Aktas, S., Yalcin, E. & Usta, M. Surface and in vitro properties of Ag-deposited antibacterial and bioactive coatings on AZ31 Mg alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 375, 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2019.07.013 (2019).

Cao, G. & Yi, N. Quantitative analysis of Anatase-Rutile mixtures by Raman spectroscopy. ChemistrySelect 5, 11530–11533. https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202002931 (2020).

Aldabergenova, S. B., Ghicov, A., Albu, S., Macak, J. M. & Schmuki, P. Smooth Titania nanotubes: Self-organization and stabilization of anatase phase. J. Non-cryst. Solids. 354, 2190–2194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2007.10.037 (2008).

Kuromoto, N. K., Simão, R. A. & Soares, G. A. Titanium oxide films produced on commercially pure titanium by anodic oxidation with different voltages. Mater. Charact. 58, 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2006.03.020 (2007).

Mei, J., Guo, R. & Sun, Z. Tunable wettability on metal oxide surfaces for future applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 510, 215843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2024.215843 (2024).

Zheng, W., Sun, C. & Bai, B. Molecular dynamics study on the effect of surface hydroxyl groups on Three-Phase wettability in Oil-Water-Graphite systems. Polym. (Basel). 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/polym9080370 (2017).

Zhou, X. (ed) in Atlas of Oral Microbiology (Yuqing Li) 1–14 (Academic Press, (2015).

Mahanta, U., Khandelwal, M. & Deshpande, A. S. Antimicrobial surfaces: a review of synthetic approaches, applicability and outlook. J. Mater. Sci. 56, 17915–17941. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-021-06404-0 (2021).

Chung, C. J., Lin, H. I., Tsou, H. K., Shi, Z. Y. & He, J. L. An antimicrobial TiO2 coating for reducing hospital-acquired infection. J. Biomedical Mater. Res. Part. B: Appl. Biomaterials. 85B, 220–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.30939 (2008).

Fuentes, E., Alves, S., López, A. & Mendizabal, L. & Sáenz De Viteri, V. in Biomaterial-supported Tissue Reconstruction or Regeneration (eds Mike Barbeck, Ole Jung, Ralf Smeets, & Tadas Koržinskas) (IntechOpen, 2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was not supported by any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.D: conceptualization; investigation; methodology; data curation; formal analysis; software; visualization; writing-review and editing and supervising.K.O: data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; writing-review.S.A: data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; writing-review.Y.B.B: investigation; data curation; formal analysis; writing-review and editing.H.K: investigation; data curation; formal analysis; software; writing-review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Durdu, S., Özcan, K., Atasoy, S. et al. Surface characterization, wettability and antimicrobial ability of anodic oxide TiO2 layers on Ti45Nb alloy. Sci Rep 15, 32974 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16330-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16330-9