Abstract

A gain-assisted atomic medium controls and modifies spatial solitons of reflection and transmission of structured light. Structured light pulses of reflection and transmission are generated and analyzed by azimuthal quantum numbers dependent on control driving fields in the medium. The study revealed the formation of spatial bright and dark solitons. The bright and dark soliton splitting regions are linearly increasing according to azimuthal quantum numbers of formula \(2\ell\). Two, four, six, and eight bright and dark soliton regions are investigated with the azimuthal quantum number of \(\ell _{1,2}=1,2,3,4\). The structured light of the reflection pulse maintained a constant shape, exhibiting weak nonlinearity along the x-axis and strong nonlinearity along the y-axis. However, the structured light transmission pulse displayed varying shapes, influenced by the balanced nonlinearities along both the x- and y-axes at higher azimuthal quantum number \(\ell _{1,2}=4\), leading to stable propagation of spatial bright solitons. These findings highlight the significant role of the structured light effect in controlling and stabilizing soliton dynamics, with potential applications in nonlinear optics, traffic flow, signal processing, plasma physics, quantum field theory, and optical soliton interferometry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A soliton is a stable, localized wave that retains its shape and energy while propagating through a nonlinear medium. Unlike ordinary waves that disperse and diminish over time, solitons are unique because of the stability amongst nonlinearity and dispersion, allowing them to travel over long distance without distortion. Nonlinear systems, where the linear superposition principle is not applicable, give rise to solitons. This nonlinearity is essential for the stability of solitons. Solitons may be involved in complex interactions with one another, but during interaction, solitons restore its original form and speed, though their positions may slightly alter1,2,3.

The spatial optical solitons are light beams that maintain their shape and size as it travel through a nonlinear medium. In these cases, spatial spread of the beam, width and height, remains constant as a result of a balance between the nonlinear effects of the medium and the natural tendency of the beam to diffract and spread out. Spatial solitons occur in nonlinear media, where the refractive index varies with light intensity, helping the beam stay focused. Unlike typical light beams that spread over distance, spatial solitons retain a consistent, localized shape. This is due to a balance between the beam’s natural tendency to spread and the nonlinear properties of the medium. As a result, spatial solitons can travel long distances without losing their structure4,5,6,7,8.

Spatial solitons of reflection and transmission of structured light through a gain-assisted atomic medium refer to the behavior of light beams with specific patterns that pass through a medium made of atoms, which amplifies the light9,10. As the light interacts with this medium, it either reflects or transmits while maintaining its stable, self-reinforcing shape due to the energy provided by the medium. The gain from the atomic medium helps to preserve the soliton properties of the light, preventing it from spreading out or losing intensity11,12,13.

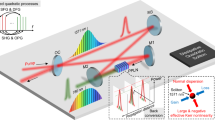

Structured light, with specific spatial properties like patterns or twisting motion, can significantly affect solitons in a gain-assisted atomic medium. The medium amplifies the light, helping solitons stay stable over longer distances by compensating for losses. When structured light interacts with the medium, it can shape the soliton, altering its propagation characteristics such as shape, velocity, and direction. The gain from the atomic medium provides the necessary energy to offset dispersion and diffraction, ensuring the soliton’s structure is maintained. This interaction is crucial in applications like optical communication and beam shaping, where maintaining the beam’s integrity is vital14,15,16,17.

The idea of solitons has advanced significantly over the years, evolving from a simple observation to a crucial topic in nonlinear dynamics and various scientific disciplines. The first soliton was identified in 1834 by John Scott Russell while observing a canal in Scotland. He saw a solitary wave traveling through the water without changing shape, which he termed the “wave of translation.” This marked the start of soliton studies18,19. In the 1870 s and 1880 s, scientists, particularly Boussinesq and Rayleigh, created mathematical theories about waves in shallow water, laying the foundation for a formal understanding of solitons20. In 1895, Korteweg and de Vries introduced the Korteweg-de Vries (KdV) equation, which became a key equation for understanding shallow water solitons and how waves maintain their shape in nonlinear environments21,22. In 1955, John Pasta, Stanislaw Ulam, and Enrico Fermi used early computers to simulate wave behavior in materials and were surprised to observe that the waves behaved in an unexpected repeating pattern23,24,25. In 1965, Norman Zabusky and Martin Kruskal coined the term “soliton” while studying the KdV equation and showed through numerical simulations that solitons could interact without changing shape26,27. More recently, solitons have been observed in Bose-Einstein condensates, ultra-cold quantum gases, to enhance the understanding of quantum nonlinear dynamics28,29,30,31.

Here are some notable applications in diverse fields. such as soliton-based solitonic networks32, optical soliton interferometry33 optical communications34, fluid dynamics35, condensed matter physics, biophysics, plasma physics36,37,38, Bose-Einstein condensates and quantum field theory39,40, traffic flow41, cosmology and astrophysics42, magnetism43, optomechanics44, superconductivity45, acoustics46, earthquake modeling47, signal processing48, laser physics49, photonic crystals50, and data encryption51.

The optical soliton pulses have been extensively investigated. For example, the evolution of optical spatial solitons has been explained, tracing their discovery and development in nonlinear optics52. It highlighted key theoretical and experimental advancements that have shaped the understanding and applications of solitons in optical systems. Similarly, the formation and dynamics of spatial solitons have been explored within semiconductor microcavities53. It examined the interaction of light with nonlinear media in these structures, providing insights into their potential applications in optical devices and systems. The behavior of temperature solitons has been investigated in heat transfer processes within confined regions54. It focused on the motion, reflection, and interaction of these solitons, offering insights into their role in wave heat transfer phenomena. The theoretical foundations and physical properties of optical solitons have been discussed in fiber optics55. The authors explored how solitons can maintain their shape and velocity during transmission, providing insights into their applications in long-distance optical communication.

Here, we examine spatial solitons of transmission and reflection of the structured light in the gain-assisted four-level atomic medium. The structured light pulses of reflection and transmission are generated and analyzed by azimuthal quantum numbers dependent on control driving fields in the medium.

Model and interactions

As seen in Fig. 1, an N-type gain-assisted atomic configuration of four levels is considered. The ground level \(\left| d\right\rangle\) is integrated to the stimulated level \(\left| a\right\rangle\) through \(E_{1}\) (pump field) with frequency (Rabi) \(\Omega _{1}\), whereas the bottom level \(\left| c\right\rangle\) is integrated with two top excited levels \(\left| a\right\rangle\) and \(\left| b\right\rangle\) by control fields \(E_{p}\) and probe \(E_{c}\) of Rabi frequencies \(\Omega _p\) and \(\Omega _c\), respectively.

The detuning of pump and probe fields in the atomic states are associated with \(\Delta _p=\omega _{ac}-\nu _{p}\) and \(\Delta _1=\omega _{ad}-\nu _1\) that represent the resonance angular frequencies. To examine the governing model and related dynamical equations of motion, we used the subsequent Hamiltonian in the rotating wave estimation and dipole. The total energy is given as \(H=H_0+H_I\), where the Hamiltonian \(H_0\) is given as:

The Hamiltonian \(H_I\) for the above configuration can be written as

The governing model of a system at normal temperature can be obtained in the form:

where \(\kappa ^\dag (\kappa )\) are raising and lowering operators. The coherence of the probe field calculated in the second order \(\rho ^{(2)}_{ac}\) as

Equation of motion expands via inductive predictions like

The Rabi frequencies of structured light fields are written as

where W is the beam waist, \(G_{1,c}\) are the associated field strengths, \(\ell _{1,2}\) are the winding number which occur either positive or negative depends upon the twisted direction of the beam and \(r=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}\) and \(\varphi =\tan ^{-1}({y}/({x+\sqrt{x^2+y^2}}))\).

The approximated susceptibility of the Gain-assisted medium is expressed as

The reflection and transmission are described as

where \(\mu _{1\rightarrow 3}\) are given as

and, \(\epsilon _2=1+\chi\) and \(\zeta _{0\rightarrow 2}\) and \(\alpha _{1}\rightarrow 2\) are given as

The incident probe beam at plane (\(z=0\)) can be expressed as:

where \(A(\omega _p, k_y)\) is described as:

.

The pulses structure of transmission and reflection is represented as

where \(S_R(x,y)\) represent pulse variation of reflection beam and \(S_T(x,y)\) represent pulse variation of transmission beam. The intensities of reflection and transmission beams are \(I_T(x,y)=|S_T(x,y)|^2\) and \(I_T(x,y)_R=|S_R(x,y)|^2\).

Results and discussion

The light that depends upon the azimuthal quantum number is called structured light. The structure light effect is introduced in probe light by azimuthal quantum numbers dependent on control fields. Structured light is amplitude, phase, and polarization modulation in specific ways and can be shaped into various patterns like vortices and holograms. Structured light is used in data transmission rate and security, super-resolution microscopy, quantum entanglement and cryptography, enhanced precision, and increased information capacity. In this work, reflection and transmission solitonic pulses are generated by azimuthal quantum number dependents of control fields in a gain-assisted atomic medium.

In a gain-assisted atomic medium, results are shown for the spatial solitons of reflection and transmission pulse intensities employing control fields of structured fields. Using \(\gamma =36.1GHz\) as the decay rate, other frequency parameters are adjusted to this level. Further \(\omega =1000\gamma\), \(d=2d_1+d_2\), \(\lambda =2\pi c/\omega\), \(r=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}\). \(\epsilon _1=2.2\), \(\epsilon _2=1+4\pi Re(\chi )\), \(d_1=1.5\lambda\), \(d_2=15\lambda\), \(k_0=\omega /c\) and \(z=0.1\lambda\), where \(k_z=\frac{2\pi }{\lambda }\cos \theta\), \(w_y=w\sec \theta\), \(W=1\lambda\).

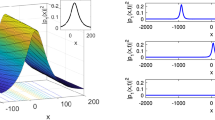

The reflection and transmission pulse intensities versus spatial coordinates \(x/\lambda\) and \(y/\lambda\). The proposed parameters are, \(\gamma _{ab,cd,bd,ad}=2.05\gamma\), \(\Delta _{1}=2\gamma\), \(\Delta _{3}=0\gamma\), \(\Delta _{p}=0\gamma\), \(G _{1}=3.5\gamma\), \(G_{c}=4\gamma\), \(\theta =\pi /3\), \(\phi =0\), \(\tau _0=1/\gamma\), \(\ell _{1,2}=1\).

Plots of reflection and transmission pulse intensity against spatial coordinates \(x/\lambda\) and \(y/\lambda\) via a four-level gain atomic medium are shown in Fig. 2. The spatially bright optical solitons in reflection and transmission pulses are controlled by structured light beams. The reflection pulse exhibits a bright optical soliton with weak spatial x-axis nonlinearity and strong spatial y-axis nonlinearity. The bright optical solitons reveal two maxima in reflection due to the structured light effect of azimuthal quantum number at \(l_{1,2}=1\) in the range of 0.4 as revealed in Fig .2a. The transmission pulse exhibits a bright optical soliton with strong spatial x-axis nonlinearity and strong spatial y-axis nonlinearity. The bright optical solitons reveal two maxima in transmission due to the structured light effect of azimuthal quantum number at \(l_{1,2}=1\) in the range of 0.03 as revealed in Fig. 2b. Furthermore, the density plots below each graph provide additional information about the spatial bright solitons structured light effect of azimuthal quantum number at \(l_{1,2}=1\) in the transmission and reflection pulses as presented in Fig. 2c, d.

The reflection and transmission pulse intensities versus spatial coordinates \(x/\lambda\) and \(y/\lambda\). The plots are traced at the same parameters as considered for Fig. 2, except at azimuthal quantum number \(\ell _{1,2}=2\).

The plots of reflection and transmission pulse intensity against spatial coordinates \(x/\lambda\) and \(y/\lambda\) across a four-level gain atomic medium are displayed in Fig. 3 at the same parameters but putting \(l_{1,2}=2\). The spatially bright optical solitons in reflection and transmission pulses are controlled by structured light beams. The reflection pulse exhibits a bright optical soliton with weak spatial x-axis nonlinearity and strong spatial y-axis nonlinearity. The bright optical solitons reveal four maxima in reflection due to the structured light effect of azimuthal quantum number at \(l_{1,2}=2\) in the intensity range of 0.4. The equilibrium condition of dispersion and nonlinearity gives stability for the formation of four bright soliton peaks of transmission pulse intensity as displayed in Fig. 3a. The transmission pulse exhibits a bright optical soliton with weak spatial x-axis nonlinearity and strong spatial y-axis nonlinearity at the same parameters. The balancing of dispersion and nonlinearity generated stability for the formation of four bright soliton peaks in transmission pulse intensity. The bright optical solitons reveal four maxima in transmission due to the structured light effect of azimuthal quantum number at \(l_{1,2}=2\) in the range of 0.006 as illustrated in Fig. 3b. Furthermore, the density plots below each graph provide clear four-peak information about the spatial bright solitons structured light effect of quantum number (azimuthal) at \(l_{1,2}=2\) in reflection and transmission pulses as displayed in Fig. 3c, d. The modified controlled solitons of reflection and transmission are useful for radar technology.

The reflection and transmission pulse intensities versus spatial coordinates \(x/\lambda\) and \(y/\lambda\). The plots are traced at the same parameters considered for Fig. 2, except using azimuthal quantum numbers, \(\ell _{1,2}=3\).

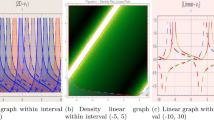

The plots of reflection and transmission pulse intensity against spatial coordinates \(x/\lambda\) and \(y/\lambda\) through four-level gain atomic medium are traced in Fig. 4 at the same parameters but \(\ell _{1,2}=3\). The spatially bright optical solitons in reflection and transmission pulses are controlled by structured light beams. The reflection pulse exhibits a bright optical soliton with weak spatial x-axis nonlinearity and strong spatial y-axis nonlinearity. The bright optical solitons reveal six maxima in reflection due to the structured light effect of azimuthal quantum number at \(l_{1,2}=3\) in the intensity range of 0.4 as illustrated in Fig. 4a. The transmission pulse exhibits bright optical solitons with strong spatial x-axis nonlinearity and strong spatial y-axis nonlinearity. The bright optical solitons reveal six maxima in transmission due to the structured light effect of azimuthal quantum number at \(l_{1,2}=3\) at the intensity range of 0.06 as given in Fig. 4b. Furthermore, the density plots below each graph provide additional information about the spatial bright solitons structured light effect of quantum number (azimuthal) at \(l_{1,2}=3\) in reflection and transmission pulses. In this case solitons stability is achieved by the equilibrium condition of dispersion and nonlinearity as shown in Fig. 4c, d. The modified results are useful for communication systems, signal processing, data transmission, and other areas in optics and photonics.

The reflection and transmission pulse intensities versus spatial coordinates \(x/\lambda\) and \(y/\lambda\). The plots are traced at the same parameters used for Fig. 2, except azimuthal quantum numbers, \(\ell _{1,2}=4\).

Plots of the intensity of reflection and transmission pulses against spatial coordinates \(x/\lambda\) and \(y/\lambda\) via a four-level gain atomic medium are demonstrated in Fig. 5. The spatially bright optical solitons in reflection and transmission pulses are controlled by structured light beams. The reflection pulse exhibits a bright optical soliton with weak spatial x-axis nonlinearity and strong spatial y-axis nonlinearity. The bright optical solitons reveal eight maxima in reflection due to the structured light effect of azimuthal quantum number at \(l_{1,2}=4\) in the intensity range of 0.4 as displayed in Fig. 5a. The transmission pulse exhibits a bright optical soliton with the balance between strong spatial x-axis nonlinearity and strong spatial y-axis nonlinearity. The bright optical solitons reveal eight maxima in transmission due to the structured light effect of azimuthal quantum number at \(l_{1,2}=4\) in the range of 0.05 as shown in Fig. 5b. Furthermore, the density plots below each graph provide additional information about the spatial bright solitons structured light effect of the quantum number at \(l_{1,2}=4\) in transmission and reflection pulses as shown in Fig. 5c, d. These solitons of reflection and transmission pulses arise due to the balancing of nonlinear refractive effect and dispersion as well as diffraction in the medium. In optical fibers, the modified transmission solitons are key rules to maintain their shape without loss of energy over a long travelling distance. These multiple peaks of solitons of reflection and transmission are modified from soliton trapping dynamics and cross-phase modulation and are useful for optical switching and optical analogs of gravity, like potential generation.

Conclusion

The spatial solitons of reflection and transmission of structured light are coherently controlled in a four-level gain-assisted atomic medium. The second-order electric probe field coherence term for the suggested gain-assisted atomic medium is computed using density matrix formalism. The coherence term is then used to determine the electric susceptibility, which directly validated the approximation of the dielectric function of the gain-assisted medium. The dielectric function of both the gain-assisted medium and the coupled cavity was subsequently used to calculate the reflection and transmission coefficients. Furthermore, these coefficients were applied to calculate the structured light pulses of reflection and transmission beams. The resulting pulses exhibited distinct behaviors, revealing the formation of spatial bright solitons of reflection and transmission in the spatial position of \(-5\lambda \le x \le 5\lambda\) and \(-5\lambda \le y \le 5\lambda\) with maxima regions of topological charge, driven by the structured light fields of the gain-assisted atomic medium. The maxima of both reflection and transmission pulses of the structured light fields increase with the azimuthal quantum number \(\ell _{1,2}=1,2,3,4\) following the \(2\ell\) dependence. The bright and dark soliton splitting regions are linearly increasing according to azimuthal quantum numbers of formula \(2\ell\). For \(\ell =1\), two peaks; for \(\ell =2\), four peaks; for \(\ell =3\), six peaks; and for \(\ell =4\), eight peaks are investigated and clearly shown in the density plots. The reflection pulse remains a constant shape with a weak x-axis nonlinearity and a strong y-axis nonlinearity. On the other hand, the transmission pulse exhibits varying shapes due to changing x- and y-axis nonlinearities. The nonlinearities along the x and y-axes balance at \(\ell _{1,2}=4\), resulting in the most stable propagation. The findings demonstrate the critical role of structured light reflection and transmission with azimuthal quantum numbers in enhancing soliton control and stability, advancing applications in nonlinear optics, optomechanics, signal processing, and optical soliton interferometry.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Scott, A. C., Chu, F. Y. & McLaughlin, D. W. The soliton: a new concept in applied science. Proceedings of the IEEE 61(10), 1443–1483 (1973).

Lamb Jr, G.L. Elements of soliton theory. New York, 29 (1980).

Lomdahl, P. S. What is a soliton. Los Alamos Science 10, 27–31 (1984).

Chen, Z., Segev, M. & Christodoulides, D. N. Optical spatial solitons: historical overview and recent advances. Reports on Progress in Physics 75(8), 086401 (2012).

Trillo, S. & Torruellas, W. eds., “Spatial solitons (Vol. 82). Springe (2013).

Walid, E., Abdul, M. & Zeeshan, A. Amir, A, Dragan Pamucar, Periodic Dark and Bright Optical Soliton Dynamics in Atomic Medium Governed by Control Fields of Milnor Polynomial and Super-Gaussian Beam. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 64, 141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10773-025-06007-4 (2025).

Zhou, G., Xu, J., Hu, H., Liu, Z., Zhang, H., Xu, C. & Zhao, Y. Off-Axis Four-Reflection Optical Structure for Lightweight Single-Band Bathymetric LiDAR. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 61 (2023).

Zhou, G. et al. A Coupling Method for the Stability of Reflectors and Support Structure in an ALB Optical-Mechanical System. Remote Sensing 17(1), 60 (2025).

Yang, X. et al. uLiDR: An inertial-assisted unmodulated visible light positioning system for smartphone-based pedestrian navigation. Information Fusion 113, 102579 (2025).

Dong, C. et al. The model and characteristics of polarized light transmission applicable to polydispersity particle underwater environment. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 182, 108449 (2024).

Alvarado-Méndez, E., Torres-Cisneros, G. E., Torres-Cisneros, M., Sánchez-Mondragón, J. J. & Vysloukh, V. “Internal reflection of one-dimensional bright spatial solitons. Optical and quantum electronics 30, 687–696 (1998).

Chen, Z., Segev, M. & Christodoulides, D. N. Optical spatial solitons: historical overview and recent advances. Reports on Progress in Physics 75(8), 086401 (2012).

Zharova, N. A., Shadrivov, I. V., Zharov, A. A. & Kivshar, Y. S. Nonlinear transmission and spatiotemporal solitons in metamaterials with negative refraction. Optics Express 13(4), 1291–1298 (2005).

Rosanov, N. N., Fedorov, S. V., Nesterov, L. A. & Veretenov, N. A. Extreme and topological dissipative solitons with structured matter and structured light. Nanomaterials 9(6), 826 (2019).

Imdad, U., Abdul, M., Amir, A. & Zareen, A. K, Reflection and transmission solitons via high magneto optical medium. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 191, 115881 (2025).

Song, Y., Shi, X., Wu, C., Tang, D. & Zhang, H. Recent progress of study on optical solitons in fiber lasers. Applied Physics Reviews, 6(2) (2019).

Zhou, G. et al. PMT gain self-adjustment system for high-accuracy echo signal detection. International Journal of Remote Sensing 43(19–24), 7213–7235 (2022).

Russell, J.S. Report on Waves: Made to the Meetings of the British Association in 1842-43 (1845).

Russell, J.S. “The wave of translation in the oceans of water, air, and ether”. Trübner and Company (1885).

Bois, P. A. Joseph Boussinesq (1842–1929): a pioneer of mechanical modelling at the end of the 19th Century. Comptes Rendus. Mécanique 335(9–10), 479–495 (2007).

Miles, J. W. The Korteweg-de Vries equation: a historical essay. Journal of fluid mechanics 106, 131–147 (1981).

Allen, J. E. The early history of solitons (solitary waves). Physica Scripta 57(3), 436 (1998).

Zabusky, N.J. “ Fermi–Pasta–Ulam, solitons and the fabric of nonlinear and computational science: History, synergetics, and visiometrics”. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science, 15(1) (2005).

Porter, M. A., Zabusky, N. J., Hu, B. & Campbell, D. K. Fermi, Pasta, Ulam and the birth of experimental mathematics: a numerical experiment that Enrico Fermi, John Pasta, and Stanislaw Ulam reported 54 years ago continues to inspire discovery. American Scientist 97(3), 214–221 (2009).

Guan, Y., Yang, L., Chen, C., Wan, R., Guo, C. & Wang, P. Regulable crack patterns for the fabrication of high-performance transparent EMI shielding windows. iScience, 28(1), 111543 (2025).

Kruskal, M. “ Nonlinear wave equations. Dynamical Systems, Theory and Applications”: Battelle Seattle 1974 Rencontres, 310-354 (2005).

Scott, A.C. “ Solitons”. The Nonlinear Universe: Chaos, Emergence, Life, 43-61 (2007).

Ketterle, W., Durfee, D.S. & Stamper-Kurn, D.M. “Making, probing and understanding Bose-Einstein condensates”. In Bose-Einstein condensation in atomic gases ( 67-176). IOS Press (1999).

Anglin, J. R. & Ketterle, W. Bose-Einstein condensation of atomic gases. Nature 416(6877), 211–218 (2002).

Luo, K. et al. Study of polarization transmission characteristics in nonspherical media. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 174, 107970 (2024).

Ma, P. et al. A 7-kW narrow-linewidth fiber amplifier assisted by optimizing the refractive index of the large-mode-area active fiber. High Power Laser Science and Engineering 12, e67 (2024).

Ahmad, J., Mustafa, Z. & Habib, J. Analyzing dispersive optical solitons in nonlinear models using an analytical technique and its applications. Optical and Quantum Electronics 56(1), 77 (2024).

Martin, A. D. & Ruostekoski, J. Quantum dynamics of atomic bright solitons under splitting and recollision, and implications for interferometry. New Journal of physics 14(4), 043040 (2012).

Mollenauer, L.F. & Gordon, J.P. “Solitons in optical fibers: fundamentals and applications”. Elsevier (2006).

Munteanu, L. & Donescu, S. “Introduction to soliton theory: applications to mechanics (Vol. 143)”. Springer Science and Business Media (2004).

Ichikawa, Y. H. Topics on solitons in plasmas. Physica Scripta 20(3–4), 296 (1979).

Inchauspe, A. Á. Solitons: A Cutting-Edge scientific proposal explaining the mechanisms of acupuntural action. Chinese Medicine 9(01), 7 (2018).

Bishop, A. R., Krumhansl, J. A. & Trullinger, S. E. Solitons in condensed matter: A paradigm. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 1(1), 1–44 (1980).

Gu, C. ed., “Soliton theory and its applications”. Springer Science and Business Media (2013).

Kengne, E., Liu, W. M. & Malomed, B. A. Spatiotemporal engineering of matter-wave solitons in Bose-Einstein condensates. Physics Reports 899, 1–62 (2021).

Komatsu, T. S. & Sasa, S. I. Kink soliton characterizing traffic congestion. Physical Review E 52(5), 5574 (1995).

Marsh, D. J. & Pop, A. R. Axion dark matter, solitons and the cusp–core problem. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 451(3), 2479–2492 (2015).

Baumgärtel, K. Soliton approach to magnetic holes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 104(A12), 28295–28308 (1999).

Chen, Z., Segev, M. & Christodoulides, D. N. Optical spatial solitons: historical overview and recent advances. Reports on Progress in Physics 75(8), 086401 (2012).

Tong, D. “TASI lectures on solitons”. arXiv preprint hep-th/0509216 (2005).

Gu, C. ed., “Soliton theory and its applications”. Springer Science and Business Media (2013).

Marin, F. “Solitons: Historical and physical introduction”. In Solitons ( 237-255). New York, NY: Springer US (2022).

Bigo, S., Leclerc, O. & Desurvire, E. All-optical fiber signal processing and regeneration for soliton communications. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 3(5), 1208–1223 (1997).

Haus, H. & Islam, M. Theory of the soliton laser. IEEE journal of quantum electronics 21(8), 1172–1188 (1985).

Blanco-Redondo, A. et al. Observation of soliton compression in silicon photonic crystals. Nature communications 5(1), 3160 (2014).

Sadegh Amiri, I., Alavi, S.E., Mahdaliza Idrus, S., Sadegh Amiri, I., Alavi, S.E. & Mahdaliza Idrus, S. Introduction of fiber waveguide and soliton signals used to enhance the communication security. Soliton Coding for Secured Optical Communication Link, 1-16 (2015).

Stegeman, G. I., Christodoulides, D. N. & Segev, M. Optical spatial solitons: historical perspectives. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 6(6), 1419–1427 (2000).

Spinelli, L., Tissoni, G., Brambilla, M., Prati, F. & Lugiato, L. A. Spatial solitons in semiconductor microcavities. Physical Review A 58(3), 2542 (1998).

Formalev, V. F., Kartashov, É. M. & Kolesnik, S. A. “On the dynamics of motion and reflection of temperature solitons in wave heat transfer in limited regions. Journal of Engineering Physics and Thermophysics 93, 10–15 (2020).

Hasegawa, A. Optical solitons in fibers. In Optical solitons in fibers ( 1-74). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg (1989).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Research Project under grant number RGP2/457/46.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Széchenyi István University (SZE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A, Ali, M. M. Alam, D. Pamucar, A. Majeed, Z. Ali Formal analysis: A, Ali, M. M. Alam, D. Pamucar, A. Majeed, Z. Ali Investigation: A, Ali, M. M. Alam, D. Pamucar, A. Majeed, Z. Ali Methodology: A, Ali, M. M. Alam, D. Pamucar, A. Majeed, Z. Ali Project administration: D. Pamucar, A. Ali Software: A, Ali, M. M. Alam, D. Pamucar, A. Majeed, Z. Ali Supervision: D. Pamucar, A. Ali Validation: A, Ali, M. M. Alam, D. Pamucar, A. Majeed, Z. Ali Writing - original draft: A. Majeed, A, Ali, Writing - review editing: M. M. Alam, D. Pamucar, A. Majeed, Z. Ali

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, A., Alam, M.M., Pamucar, D. et al. Coherent control of reflection and transmission solitons of structured light via a gain-assisted medium. Sci Rep 15, 34274 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16538-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16538-9