Abstract

The detection of dental caries is typically overlooked on panoramic radiographs. This study aims to leverage deep learning to identify multistage caries on panoramic radiographs. The panoramic radiographs were confirmed with the gold standard bitewing radiographs to create a reliable ground truth. The dataset of 500 panoramic radiographs with corresponding bitewing confirmations was labelled by an experienced and calibrated radiologist for 1,792 caries from 14,997 teeth. The annotations were stored using the annotation and image markup standard to ensure consistency and reliability. The deep learning system employed a two-model approach: YOLOv5 for tooth detection and Attention U-Net for segmenting caries. The system achieved impressive results, demonstrating strong agreement with dentists for both caries counts and classifications (enamel, dentine, and pulp). However, some discrepancies exist, particularly in underestimating enamel caries. While the model occasionally overpredicts caries in healthy teeth (false positive), it prioritizes minimizing missed lesions (false negative), achieving a high recall of 0.96. Overall performance surpasses previously reported values, with an F1-score of 0.85 and an accuracy of 0.93 for caries segmentation in posterior teeth. The deep learning approach demonstrates promising potential to aid dentists in caries diagnosis, treatment planning, and dental education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oral diseases are a major public health problem, affecting nearly 3.5 billion people worldwide in 2022. Among the major oral diseases, untreated dental caries of permanent teeth are the most prevalent, with approximately 2 billion cases (29%), followed by severe periodontal disease, untreated dental caries of deciduous teeth, and edentulism1. Untreated dental caries can be difficult and costly to manage once they progressed into an advanced stage2. Diagnosing dental caries, especially in the initial stages, is crucial to dental care management3. Radiographic examination is one of the diagnostic tools for determining hidden proximal caries, their extent, progression, and classification according to the International Caries Classification and Management System4. Despite the use of radiography as a primary diagnostic tool for dental caries, diagnosis often depends on dentists’ subjective judgment, which varies with experience and can lead to inconsistencies in evaluation5. Implementing a standardized, automated caries evaluation method could help improve accuracy and consistency in radiographic assessments, reducing the error from tedious and repetitive diagnostic tasks.

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms, particularly deep learning (DL) models, has markedly driven AI integration into various aspects of everyday life. In dentistry, AI has found applications across numerous fields, including prosthodontics, customized computer-aided design and manufacturing of orthodontic and surgical appliances, oral cancer detection, implantology, periodontal disease management, endodontics, and cariology6,7. DL, an advanced type of machine learning, has been used to address three major challenges: classification, detection, and segmentation8. For AI classification of caries, the convolutional neural network called MobileNet V2 achieved an accuracy of 0.87 on cropped third molars from panoramic radiographs9. Studies on caries detection have explored various imaging modalities, including intraoral photographs (0.92 accuracy)10, smartphone color photographs (0.92 accuracy)11, bitewing radiographs (0.87 accuracy)12, and panoramic radiographs (0.86 accuracy)13. For caries segmentation, Ying et al. proposed a DL network for periapical radiographs, achieving a dice similarity score (DSC) of 0.7514. More recently, Zhu et al. introduced CariesNet, a novel DL architecture that delineates different caries degrees from panoramic radiographs, with a mean DSC and accuracy of 0.94 for segmenting three caries levels15.

The panoramic radiograph serves as an essential diagnostic tool, facilitating the screening and assessment of the maxillomandibular complex and optimizing dental interventions during initial appointments, particularly in vulnerable populations16. Commonly employed in clinical practice, panoramic radiographs offer a single comprehensive image of the entire dentition and jaws, making them particularly beneficial for orthodontic assessments and the evaluation of impacted teeth in young adults due to their convenience and patient comfort17. While bitewing radiographs—considered the gold standard for detecting proximal caries18—can assess early enamel caries, identifying caries on panoramic radiographs is more challenging due to their lower image resolution and multiple superimpositions19. This study aimed to assess the performance of AI in identifying and segmenting dental caries at multiple stages, including enamel, dentin, and pulpal involvement on panoramic radiographs, with the use of posterior bitewing radiographs to confirm the ground truth for expert labeling and annotation.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted following the Helsinki Declaration standards and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Mahidol University Multi-Faculty Cooperative IRB Review (MU-MOU CoA.2022/060.1511), approval date 15.11.2022.

Studied panoramic and bitewing radiographs

This study included 500 panoramic radiographs of patients with all posterior teeth bitewing radiographs taken on the same day, from January to August 2022 at the Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology Clinic, Dental Hospital, Faculty of Dentistry, Mahidol University. The inclusion criteria for panoramic radiographs were patients older than 13 years, with overlapping enamel less than the outer half of the proximal enamel, and at least one dental caries identified on the bitewing radiograph. The exclusion criteria included jawbone pathology, image distortion, noisy images, rotated teeth over 90°, amelogenesis imperfecta, dentinogenesis imperfecta, full mouth crown restorations, orthodontic brackets, and two or more implants in the same quadrant. All panoramic radiographs were taken using a CS9000C machine (Carestream Health, Inc., New York, USA) with a tube voltage of 68–72 kV, tube current of 8–10 mA, and exposure time of 15.1 s. All posterior teeth bitewing radiographs were taken, with at least four radiographs for each patient, using either a Planmeca ProX™ intraoral X-ray machine (Planmeca OY, Helsinki, Finland) or a Belmont PHOT-XIIS 505 intraoral X-ray machine (Takara Belmont Corporation, Osaka, Japan), and a VistaScan Mini Plus imaging plate scanner (DÜrr Dental Se, Bietigheim–Bissingen, Germany) with a resolution of 20 line-pairs/mm. All radiographs were anonymously exported as DICOM files by a radiological technologist (S.C.).

Calibration for dental caries detection

Here, 100 out of 500 panoramic radiographs were randomly selected for intrarater and interrater reliability. Radiologist #1, and Radiologist #2, a 21-year-experienced oral and maxillofacial radiologist (J.K.), independently recorded the tooth number and tooth surfaces revealing dental caries, including its classification as enamel caries (radiolucent area limited to the enamel), dentine caries (a radiolucent area extending beyond dentoenamel junction to dentine), or dental caries with pulp involvement (a large radiolucent area reaching the pulp chamber resulting in widening apical periodontal ligament space and/or thickening apical lamina dura). All radiographs were displayed on a diagnostic radiology monitor with a resolution of 2560 × 1600 (Eizo RadiForce RX430, EIZO Corporation, Ishikawa, Japan) under low ambient light conditions. Both radiologists reviewed and discussed the disagreed results together; if consensus could not be reached, a 25-year-experienced oral and maxillofacial radiologist (R.A.), Radiologist #3, was asked to independently determine the presence and classification of dental caries. The consensus data were considered ground truth. Two months later, a 27-year-experienced oral and maxillofacial radiologist (S.P.D.) repeated 100 panoramic radiographs, comprising 469 dental caries, in the same manner. The reliability values of Radiologist #1 and Radiologist #2 compared to the ground truth were 0.832 and 0.864, respectively. The intrarater correlation coefficient with a 95% confidence level of Radiologist #1 was 0.734. The interrater correlation coefficient with a 95% confidence level for Radiologist #1 and Radiologist #2 was 0.707. Figure 1 shows a schematic illustration of the study workflow, including ground truth and AI for dental caries segmentation on panoramic radiographs.

Dental caries labeling

After calibration, the 500 anonymous panoramic radiographs together with bitewing radiographs of the same individuals were imported to an annotation and image markup (AIM) workstation version 4.6.0.7 (Faculty of Information and Communication Technology, Mahidol University) and were displayed on a diagnostic radiology monitor with a resolution of 2560 × 1600 (Eizo RadiForce RX430, EIZO Corporation, Ishikawa, Japan) under proper ambient light conditions. Annotation information was stored using the AIM20 standard, following guidelines for comprehensive and consistent annotation. The 27-year-experienced oral and maxillofacial radiologist, (S.P.D.), meticulously identified and labeled the regions of interest on panoramic radiographs using information from intraoral bitewing radiographs of the same individuals, which offer higher spatial resolution due to the image receptor’s proximity to the teeth and eliminate image distortion or overlapping of teeth. This process included documenting the number of teeth and tooth structures affected by dental caries.

Artificial intelligence system for dental caries segmentation

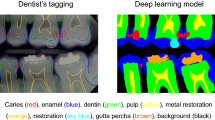

The caries detection system relies on semantic segmentation within image processing techniques. It operates by taking a panoramic radiograph as input and classifying and segmenting the regions of detected caries pixel by pixel. The process involves applying a tooth detection model to the panoramic radiograph to identify individual teeth. The model delineates the boundary of each tooth within the panoramic radiograph, subsequently extracting each tooth into a separate image. These separated tooth images are then input into the caries segmentation model to identify the caries regions. Once the caries regions are determined, the resulting segmented map is overlaid onto the separated tooth images and then reassembled to visualize a predicted panoramic radiograph (Fig. 2).

Deep learning models

The system comprises two DL models. One model is responsible for locating each tooth within a panoramic radiograph, while the other focuses on segmenting the caries regions on each identified tooth.

The tooth detection model operates within the framework of image object detection, aiming to isolate each tooth into individual images to mitigate the influence of large, uninteresting areas of panoramic radiographs, which can impede caries segmentation efficiency. The model architecture employed was the you only look once version 5 (YOLOv5) object detection model21, renowned for its compactness and high performance in detecting anomalies or specific structures within medical images. The YOLOv5s architecture was utilized specifically with approximately 7.2 million parameters. This model was trained on the substantial public dataset called “DENTEX CHALLENGE 2023”22,23. In this study, the efficacy of the trained YOLOv5s model in identifying tooth areas is impressive, yielding a precision of 99.6%, a recall of 98.9%, a mean average precision (mAP) of 99.5% at mAP50, and 79.9% at mAP50-95. Figure 2 shows a sample output of tooth detection generated by the model.

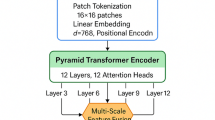

The semantic segmentation model of dental caries employed in this study was Attention U-Net24, adapted from the U-Net model25, which is a high-performance segmentation architecture tailored for medical imaging. The Attention U-Net has been repurposed for caries segmentation in dental radiographs. The Attention U-Net architecture (Supplementary Fig. 1), incorporates Attention Gates as key modules integrated into the main U-Net structure. These Attention Gates enhance model efficiency by selectively focusing on relevant features during the segmentation process.

In this study, 14,997 individual tooth images were extracted from 500 panoramic radiographs to train a segmentation model. Of these, 2,161 images with annotated dental caries were randomly selected for model training, while 737 images were set aside for validation and testing. Intensity normalization was applied in preprocessing, as image acquisition conditions were consistent. The remaining images were reserved for overall system evaluation conducted by dental experts. The segmentation model was trained to classify pixels into two binary classes: caries and non-caries.

The training environment consisted of an Ubuntu 22.0 operating system, running on an AMD Ryzen 9 3950 × 16-Core Processor with an Nvidia GeForce RTX 2080 SUPER GPU. Key training parameters included a learning rate of 1 × 10−4, a batch size of 8, and the Adam optimizer. Binary cross-entropy loss was used, and the training concluded after 100 epochs.

For preliminary model selection, we conducted direct experiments on our own dataset rather than relying on published results from different sources. We randomly selected 100 radiographic images from our dataset to evaluate several state-of-the-art segmentation architectures under identical conditions, which allowed us to compare multiple models fairly while saving time and computational resources. The architectures we tested include U-Net25, Nested U-Net26, Swin U-Net27, Attention U-Net24, TransUNet28, and R2U-Net29. Each model was trained from scratch on this 100-image subset and evaluated using the Intersection-over-Union (IoU) metric on a per-cropped-image basis. This consistent evaluation on the same data (instead of comparing against results from different datasets in literature) ensured a fair performance comparison in our specific context.

The results of this comparative experiment, summarized in Table 1, showed a clear difference in performance among the models. Attention U-Net achieved the highest IoU score on our dataset, outperforming the other competitive architectures in this test. Based on these results, we selected Attention U-Net as the segmentation backbone for our proposed system. This choice is grounded in the superior performance of Attention U-Net on our own data, confirming that it is the most effective model for our radiographic image segmentation task under the given conditions.

Evaluation metrics

The dental caries segmentation on the panoramic radiograph was compared to the ground truth labeled by the radiologists. The difference in the number of teeth with dental caries identified by AI and ground truth was recorded. The classification of dental caries—enamel caries, dentine caries, and caries with pulp involvement—was also recorded and compared. Four variables were obtained from a comparison of labeled dental caries between the ground truth and AI:

-

a)

TP: Pixels that are correctly segmented compared to the labeled ground truth segmentation on posterior teeth. The smaller segmented region labeled by AI was counted as a true positive.

-

b)

TN: Pixels that are not labeled by either the AI or the ground truth.

-

c)

FP: Pixels that are labeled by the AI but are not labeled in the ground truth.

-

d)

FN: Pixels that are not labeled pixel by AI but are labeled in ground truth.

Based on these variables, the following metrics were analyzed to determine AI performance in dental caries segmentation on panoramic radiographs:

-

a)

IoU: Represents the ratio of the area of overlap between the AI-segmented caries and the ground truth, divided by the union area of both the AI segmentation and the ground truth. \(\:IoU=\frac{TP}{TP+FP+FN}\)

-

b)

DSC: Quantifies how closely the AI segmentation matches the ground truth by calculating the ratio of twice the area of overlap between AI-segmented caries and the ground truth, divided by the sum of the areas of both AI-segmented caries and the ground truth. \(\:DSC=\frac{2TP}{2TP+FP+FN}\)

-

c)

Precision: Represents the fraction of correctly AI-segmented caries among all the segmented caries by AI. \(\:Precision=\frac{TP}{\begin{array}{c}TP+FP\end{array}}\)

-

d)

Recall or sensitivity: Represents the rate of correctly AI-segmented caries by AI among the labeled actual caries on ground truth. \(\:Recall=\frac{TP}{TP+FN}\)

-

e)

F1-score: Quantifies the weighted average of dental caries between the precision and recall rates. \(\:F1-score=2\:x\frac{Precision\:X\:Recall}{Precision\:+Recall}\)

-

f)

Specificity: Represents the rate of correctly AI-unlabeled healthy teeth among healthy teeth. \(\:Specificity=\frac{TN}{TN+FP}\)

-

g)

Accuracy: Represents the rate of correctly AI-segmented caries and AI-unlabeled healthy teeth among all detected teeth. \(\:Accuracy=\:\frac{TP+TN}{TP+TN+FP+FN}\)

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc for Windows, version 22.023 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). To compare AI performance in segmenting various degrees of dental caries, the linear weighted kappa was analyzed. The kappa values were defined as follows: values of ≤ 0 indicate no agreement; 0.01–0.20 as none to slight; 0.21–0.40 as fair; 0.41–0.60 as moderate; 0.61–0.80 as substantial; and 0.81–1.00 as strong agreement30. To analyze the agreement in caries segmentation between the ground truth and AI, the Bland–Altman analysis31 was used to represent the mean difference between the two analyses and display it as a scatterplot. To determine AI performance in dental caries segmentation, the IoU, DSC, precision, recall, specificity, and accuracy were analyzed.

Results

Patient demographics and dental caries classification

A dataset of 500 panoramic radiographs was obtained from 317 females with a mean age of 25.7 years and 183 males with a mean age of 26.2 years. Within this dataset, 1,792 out of 9,053 posterior teeth were confirmed to have dental caries through bitewing radiographs. When detecting both anterior and posterior teeth from panoramic radiographs, a total of 14,997 teeth were analyzed. The ground truth for caries classification was established based on three stages: 519 surfaces (27.1%) with enamel caries, 1,163 surfaces (60.7%) with dentine caries, and 234 surfaces (12.2%) exhibiting pulp involvement.

Agreement of tooth number with dental caries on panoramic radiograph

An analysis comparing AI caries segmentation to oral and maxillofacial radiologists (ground truth) revealed strong agreement (weighted kappa = 0.943, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.927–0.958) between the two methods (Italic number, Table 2). The most frequent agreement involved both AI and radiologists identifying two teeth with caries per case (123 cases), followed by the identification of three teeth with caries per case (75 cases). Figure 3 shows an example of 13 posterior teeth with dental caries. The upper image displays the ground truth segmentation, labeled by an oral and maxillofacial radiologist, while the lower image presents the AI model’s segmentation, perfectly matching the ground truth for all 13 caries. However, discrepancies existed in 56 cases (11.2% of all evaluated cases). These disagreements are Bold and Underline numbers in Table 2. Notably, in most disagreements, the radiologist identified one more tooth with caries than the AI system. The most significant discrepancy involved a ground truth evaluation of five teeth with caries, while the AI system identified only two (Underline number, Table 2).

Agreement of tooth surfaces with enamel caries

An analysis comparing AI segmentation to ground truth for enamel caries revealed strong agreement (weighted kappa = 0.907, 95% CI: 0.871–0.943) as Italic number, Table 3. The most frequent agreement involved both AI and radiologists identifying one tooth surface with enamel caries per radiograph (100 cases), followed by two enamel caries surfaces per radiograph (77 cases). However, discrepancies existed in 24 surfaces out of 249 surfaces (9.64%), where the AI detected fewer caries surfaces (Bold number, Table 3). In two cases, the radiologist identified three enamel caries surfaces, whereas the AI system only detected one surface. In another case, the AI could detect only two surfaces of enamel caries from four surfaces identified by the radiologist. Conversely, in two cases, the radiologist identified three enamel caries surfaces while the AI system identified four surfaces (Underline number, Table 3). This discrepancy occurred because the ground truth of these two cases was dentine caries, but AI segmented them as enamel caries.

Agreement of tooth surfaces with dentine caries

An analysis comparing AI segmentation to ground truth for dentine caries revealed strong agreement (weighted kappa = 0.948, 95% CI: 0.930–0.966) as Italic number, Table 4. The most frequent agreement involved both AI and radiologists identifying one dentine caries surface per radiograph (130 cases), followed by two dentine caries surfaces per radiograph (114 cases). However, discrepancies existed in 33 out of 436 surfaces (7.57%), where the AI detected fewer dentine caries surfaces than the radiologist (Bold number, Table 4). In one case, the radiologist identified nine surfaces with dentine caries, whereas the AI system detected only six. Conversely, in three cases, the AI system identified one more dentine caries surface than the radiologist (Underline number, Table 4). These discrepancies likely occurred because, in one case, the AI segmented pulp involvement as dentine caries, and in the other two cases, the AI segmented enamel caries as dentine caries.

Agreement of teeth with dental caries with pulp involvement

An analysis comparing AI segmentation to ground truth for dental caries with pulp involvement revealed almost perfect agreement (weighted kappa = 0.981, standard error = 0.013, 95% CI: 0.956–1.000) as Italic number in Table 5. The most frequent agreement involved both AI and radiologists identifying one tooth with pulp involvement per radiograph (128 cases), followed by two teeth with pulp involvement per radiograph (22 cases). However, in 2 out of 168 cases (1.19%), the AI system identified one fewer tooth with pulp involvement than the radiologist, as Bold number in Table 5.

Agreement of dental caries segmentation by AI and ground truth (Bland–Altman analysis)

Bland–Altman scatter plots (Fig. 4) were used to assess the agreement between the ground truth and AI systems for dental caries segmentation. The x-axis of the graph shows the mean number of teeth with dental caries per radiograph from ground truth and AI. The y-axis of the graph shows the difference between the number of teeth with dental caries identified by the ground truth and the AI. The mean difference between the two methods was 0.13 teeth per radiograph, with a 95% CI of 0.098–0.170. Limits of agreement (dash lines) ranged from − 0.66 to 0.93 teeth per radiograph (Fig. 4a). These results suggest good agreement between the AI and the radiologist, with most of the differences falling within the expected range. When considering various dental caries classifications, the mean difference between the two methods was highest for enamel caries (0.10 tooth surfaces per radiograph), followed by dentine caries (0.08 tooth surfaces per radiograph), and lowest for dental caries with pulp involvement (0.01 tooth per radiograph) (Fig. 4b and d).

Bland–Altman plots of the mean difference between the mean ground truth and the mean AI: (a) Total teeth with dental caries per radiograph, (b) Tooth surfaces with enamel caries, (c) Tooth surfaces with dentine caries, and (d) Teeth with dental caries with pulp involvement. Positive values indicate that the radiologist detected dental caries more than the AI system.

Confusion matrix analysis

To evaluate the diagnostic performance of the AI model at the per-tooth level, we employed a confusion matrix framework. Although commonly used for classification tasks, the confusion matrix was adapted in this study to assess the segmentation model’s ability to identify dental caries on a tooth-by-tooth basis. This approach provides clinically relevant performance indicators—such as true positives (TP), false negatives (FN), false positives (FP), and true negatives (TN)—allowing us to interpret whether the model correctly identifies carious or non-carious teeth. It also facilitates the calculation of key diagnostic metrics, such as specificity and accuracy, which are particularly meaningful in the context of dental diagnosis.

Figure 5 presents the confusion matrix for dental caries segmentation on posterior teeth and on all teeth. Since dental caries in the ground truth were confirmed through bitewing radiographs for all posterior teeth, the TP count was 1,725 teeth and the FN count was 67 teeth, were identical. Anterior teeth were not labeled due to a lack of confirmatory diagnostic data from other techniques. For posterior teeth, the number of FPs (519 teeth) exceeded the number of FNs, indicating that the AI model tended to overpredict caries in healthy posterior teeth. Nevertheless, the high number of TNs suggests that the model performs well in correctly identifying non-carious teeth.

Although semantic-segmentation performance is principally conveyed through intersection over union (IoU) and the dice similarity coefficient (DSC), we further derive a tooth-level confusion matrix by thresholding each predicted mask and assigning a binary label to every one of the 14,997 teeth. This step reframes the task as a clinically relevant classification problem that contrasts carious teeth with healthy teeth, enabling the direct computation of specificity and the area under the receiver-operating-characteristic curve, alongside established overlap metrics.

Quantitative performance evaluation

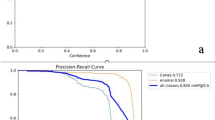

AI performance in segmenting dental caries was evaluated using IoU, DSC, precision, recall, specificity, and accuracy for posterior teeth and all teeth (Table 6). IoU scores ranged from 0.66 to 0.75, and DSC/F1 scores ranged from 0.79 to 0.85, indicating moderate performance in segmenting caries. A precision of 0.77 suggests that the model has a moderate ability to distinguish caries from non-carious teeth, particularly in posterior teeth. High recall (0.96) highlights the model’s effectiveness in identifying most carious lesions. A specificity of 0.93 to 0.94 indicates a good ability to correctly classify non-carious teeth. Overall accuracy was also high at 0.93 to 0.94, suggesting satisfactory overall performance.

Discussion

This study introduces a novel approach for dental caries segmentation in panoramic radiographs utilizing the DL approach of the AI system. We depart from prior studies that relied solely on ground truth established through single radiographic techniques, such as bitewing radiographs32, periapical radiographs14, or panoramic radiographs15,33,34,35. This study presents a unique approach by leveraging complementary information from two distinct modalities, high-resolution bitewing and panoramic radiographs, to create ground truth image annotation data. Bitewing radiographs provide detailed views of posterior teeth, making them ideal for capturing dental caries and remain the gold standard for detecting proximal caries18. Panoramic radiograph, a common imaging modality for new dental patients, offers a broader overview of dentition, which is convenient and comfortable to use. By combining information from both modalities, an experienced oral and maxillofacial radiologist meticulously labeled 1,792 dental caries lesions on the corresponding panoramic radiographs, establishing a more robust ground truth for AI segmentation.

The results revealed promising agreement between the AI system and ground truth for caries segmentation. Kappa statistics for both the number of teeth with caries and individual caries classifications (enamel, dentine, and pulp involvement) were ≥ 0.9, signifying “strong” agreement according to Conger AJ30. This high level of concordance between the AI and radiologists suggests good potential for the model’s clinical utility. For the challenging enamel caries, the AI system also showed promising potential to be detected on panoramic radiographs with strong agreement with the experts. Additionally, the agreement observed in the Bland–Altman plots indicates that all mean differences are below one tooth or one surface in depicting multistage caries. This underscores the strong agreement between the AI system and radiologists in identifying dental caries. Notably, the highest agreement was observed for caries with pulp involvement. This might be attributed to the distinct radiographic features associated with this stage, such as the large radiolucent area at the coronal dentine and changes in the apical lamina dura and/or PDL spaces, which could facilitate easier identification and segmentation using the AI model.

Despite the high level of agreement, some discrepancies emerged, particularly for enamel caries. The AI system tended to underestimate the number of enamel caries surfaces compared to radiologist evaluations (Table 3). This underestimation could be attributed to limitations in detecting smaller enamel lesions on radiographs compared to lesions with dentine or pulp involvement. Previous studies have also shown that even dentists demonstrate low sensitivity in detecting enamel caries on radiographs36,37. Furthermore, the AI model exhibited misclassifications in both directions, dentine caries misclassified as enamel caries (Underline number, Table 3; Fig. 6a and b), or enamel caries misclassified as dentine caries (Underline number, Table 4; Fig. 6c and d). In one case, the AI model predicted caries with pulp involvement as dentine caries (Underline number, Table 4; Fig. 6e). However, discrepancies were only observed in 5 out of 500 cases with no specific trend, and detecting caries on panoramic radiographs remains challenging even for experts19,38.

Examples of caries misclassification: cropped bitewing radiographs, cropped panoramic radiographs, ground truth, and artificial intelligence (AI)-segmented caries. (a) and (b) AI-predicted dentine caries as enamel caries; (c) and (d) AI-predicted enamel caries as dentine caries; (e) AI-predicted caries with pulp involvement as dentine caries.

Understanding how the AI system interprets data is crucial for ensuring its effectiveness and reliability in clinical applications. Analysis of the confusion matrix (Fig. 5) revealed a bias toward overprediction of caries in non-carious teeth, as indicated by a higher number of FPs —teeth incorrectly identified as carious by the AI— compared to FNs. These FPs were associated with various anatomical structures, including the palatoglossal space, pulp chamber, corners of the mouth opening, cervical burnout, buccal pits, oropharynx, inter-radicular bone, and pulpal horns (Fig. 7). The high FPs contributed to a moderate precision (0.77), indicating that while the model successfully identifies most areas with caries, it occasionally includes healthy tooth structures as well. Importantly, general dentists can usually distinguish these FPs from actual caries. However, FNs—missed carious lesions—pose a risk of underdiagnosis, which may delay appropriate intervention. In our study, the FP rate exceeded the FN rate, suggesting that the model is more sensitive than it is specific. When uncertainty arises, additional clinical examination or bitewing radiographs are typically employed to confirm the diagnosis. Therefore, while the AI system shows strong potential to support dentists’ clinical decision-making, it is not yet suitable as a standalone diagnostic tool.

Panoramic radiographs are a common imaging modality used for new patients and markedly contribute to the early diagnosis and prompt treatment of dental caries. Early intervention helps prevent the need for more time-consuming and expensive procedures, such as root canals, crown restorations, tooth extractions, and dental implants2. Therefore, our AI model prioritizes minimizing FNs, which occur when caries are present but not detected by the model. This is reflected in our high recall value of 0.96, indicating strong effectiveness in identifying most dental caries on panoramic radiographs. This supports the use of AI as an aid in the challenging task of detecting caries on panoramic radiographs38.

Recent studies have explored various DL models for caries segmentation on panoramic radiographic images, each demonstrating distinct strengths and limitations (Table 7). Dayi et al. proposed DCDNet, achieving moderate performance in segmenting occlusal, proximal, and cervical caries but showing room for improvement in recall values34. Chen et al. utilized an atrous spatial pyramid pooling-integrated U-Net, which excelled in recall, indicating better detection sensitivity, although precision needed enhancement39. Haghanifar et al. developed PaXNet, which performed well in precision but had lower recall, suggesting challenges in detecting milder caries forms13. Zhu et al. introduced CariesNet, demonstrating excellent performance across all metrics, indicating a well-balanced model for caries detection and classification15. Alharbi et al. used U-Net3+, achieving high accuracy but lower IoU and DSC scores, pointing to potential improvements in segmentation precision40. Lian et al. employed nnU-Net and DenseNet121, achieving high precision and specificity, although DSC and recall required further enhancement35.

To assess the overall performance of our AI model, the F1-score was analyzed, which considers both precision and recall. This study achieved an F1-score of 0.85 for caries segmentation in posterior teeth (Table 6). This score surpasses previously reported values by Dayi et al.34 (0.68–0.71), Chen et al.39 (0.78), Haghanifar et al.13 (0.78), but falls short of the scores by Zhu et al.15 (0.93) and Lian et al.35 (0.90). This discrepancy might be attributed to the smaller sample size of dental caries in our study and the potential differences in the AI model algorithms employed. Our study employed YOLOv5 and Attention U-net models, achieving high recall and balanced performance across other metrics, indicating strong detection capabilities and segmentation accuracy. Compared to previous studies, our models demonstrated superior recall, highlighting effective caries detection. Our research contributes to the existing literature by offering a robust solution for caries segmentation, with potential areas for future enhancement identified through comparative analysis. IoU and DSC are standard metrics for evaluating semantic segmentation performance. Our model achieved a DSC of 0.85 for caries segmentation in posterior teeth, exceeding the results of previous studies by Dayi et al.34 (0.68–0.71), Lian et al.35 (0.66), and Alharbi et al.40 (0.60) (Table 6). Nevertheless, it remains lower than the score reported by Zhu et al.15 (0.94). This difference might be explained by the smaller sample size of dental caries in our study, which was approximately two-thirds the size used by Zhu et al.15.

Despite the promising performance of our AI model, segmenting dental caries on panoramic radiographs presents inherent difficulties19,37,38. Several factors contribute to this challenge. Unequal X-ray exposure can lead to inconsistencies in how dental caries and normal tooth structures appear across images. Variations in tooth properties, such as density and thickness, as well as superimpositions from surrounding structures, can obscure dental caries. Additionally, panoramic radiographs provide a flattened view of the jaws, introducing geometric distortions such as overlapping premolars, which further complicate segmentation. These factors collectively introduce noise and artifacts into radiographic images, hindering the ability of conventional segmentation techniques to precisely locate and delineate dental caries.

This study advances the field of deep learning-based caries detection by addressing key limitations in previous research through clinically grounded, multistage segmentation on panoramic radiographs. Unlike earlier studies that rely on limited datasets, binary classification, or single-image modalities, our study integrates panoramic radiographs with gold-standard bitewing confirmations to ensure accurate ground truth labeling. Furthermore, the use of a two-model architecture, YOLO for tooth detection and Attention U-Net for caries segmentation, enables precise localization and differentiation of caries stages (enamel, dentine, and pulp). This level of granularity and clinical validation is rarely seen in prior works. The model also achieves high recall (0.96), emphasizing its focus on minimizing missed diagnoses, which is critical in clinical settings. Overall, this study contributes a robust, validated, and clinically applicable system that not only outperforms many prior models in accuracy and F1-score but also aligns closely with real-world diagnostic workflows.

Multistage deep learning can provide notable benefits for caries segmentation, particularly in panoramic radiographs, where caries regions are often very small and occupy only a tiny fraction of the image. Single-stage models tend to overlook these fine details due to limited pixel resolution and the dominance of unrelated structures, such as the jaw or soft tissue. A multistage framework, where the first stage localizes individual teeth and the second stage performs focused segmentation, allows the model to operate on higher-resolution regions of interest. This not only improves the ability to capture small carious lesions but also mitigates the class imbalance problem by excluding irrelevant areas and concentrating learning on diagnostically significant regions.

Future development of the AI system aims to enhance its capabilities and applicability. Studying the efficiency of general dentists and dental students in identifying caries with and without AI assistance could yield valuable insights. Incorporating additional data with more complex panoramic radiographs—such as those with increased tooth overlap—with accurate annotations could further enhance the model’s robustness. Furthermore, the inclusion of external data from multiple centers and imaging devices could enhance the model’s generalizability and adaptability across diverse imaging conditions.

Since this study did not confirm dental caries on anterior teeth through additional methods, expert annotations for these were not included. Nevertheless, despite the absence of specific annotations, the AI system was still able to identify caries on anterior teeth in panoramic radiographs, indicating a promising direction for further refinement.

In addition, future studies should explore how dentists and radiologists interact with the AI system in real-world clinical settings. Evaluating user experience, decision-making behavior, diagnostic confidence, and workflow integration will provide critical insights into how AI can effectively support, rather than replace, clinical judgment. This line of research is essential to ensure that AI tools are both clinically useful and seamlessly integrated into everyday dental practice.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated the significant potential of AI-based DL system for dental caries segmentation in panoramic radiographs. By leveraging complementary data from both high-resolution bitewing and panoramic radiographs, we established a more robust and accurate ground truth for AI training, addressing the limitations of prior studies relying on single radiographic technique. The implementation of YOLOv5 for tooth detection and Attention U-Net for caries segmentation has shown exceptional performance, achieving high accuracy, precision, recall, and specificity. This system enhances the detection of caries often overlooked in panoramic evaluations and offers a practical, efficient tool for dental practitioners. The results underscore the effectiveness of our AI solution in improving diagnostic accuracy and consistency, leading to better clinical decision-making and patient outcomes. Our approach represents a significant advancement in dental radiology, offering a reliable and scalable solution for dental caries detection and segmentation in everyday clinical practice.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Organization, G. W. H. Global oral health status report: towards universal health coverage for oral health by 2030. (2022). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Petersen, P. E., Bourgeois, D., Ogawa, H., Estupinan-Day, S. & Ndiaye, C. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull. World Health Organ. 83, 661–669 (2005).

Abdelaziz, M. Detection, diagnosis, and monitoring of early caries: the future of individualized dental care. Diagnostics (Basel). 13, 3649. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13243649 (2023).

Pitts, N. B. et al. ICCMS™ Guide for practintioners and educators. (2014). https://www.iccms-web.com/uploads/asset/59284654c0a6f822230100.pdf

Dabiri, D. et al. Diagnosing developmental defects of enamel: pilot study of online training and accuracy. Pediatr. Dent. 40, 105–109 (2018).

Ghaffari, M., Zhu, Y. & Shrestha, A. A review of advancements of artificial intelligence in dentistry. Dent. Rev. 4, 100081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dentre.2024.100081 (2024).

Ren, R., Luo, H., Su, C., Yao, Y. & Liao, W. Machine learning in dental, oral and craniofacial imaging: a review of recent progress. PeerJ 9, e11451. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.11451 (2021).

Majanga, V. & Viriri, S.(2022) A survey of dental caries segmentation and detection techniques. Sci. World J. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8415705

Vinayahalingam, S. et al. Classification of caries in third molars on panoramic radiographs using deep learning. Sci. Rep. 11, 12609. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92121-2 (2021).

Kühnisch, J., Meyer, O., Hesenius, M., Hickel, R. & Gruhn, V. Caries detection on intraoral images using artificial intelligence. J. Dent. Res. 101, 158–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345211032524 (2022).

Duong, D. L., Kabir, M. H. & Kuo, R. F. Automated caries detection with smartphone color photography using machine learning. Health Inf. J. 27, 14604582211007530. https://doi.org/10.1177/14604582211007530 (2021).

Estai, M. et al. Evaluation of a deep learning system for automatic detection of proximal surface dental caries on bitewing radiographs. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 134, 262–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oooo.2022.03.008 (2022).

Haghanifar, A. et al. Tooth segmentation and dental caries detection in panoramic X-ray using ensemble transfer learning and capsule classifier. Multimed Tools App. 82, 27659–27679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-023-14435-9 (2023).

Ying, S., Wang, B., Zhu, H., Liu, W. & Huang, F. Caries segmentation on tooth X-ray images with a deep network. J. Dent. 119, 104076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2022.104076 (2022).

Zhu, H. et al. CariesNet: a deep learning approach for segmentation of multi-stage caries lesion from oral panoramic x-ray image. Neural Comput. Appl. 35, 16051–16059. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-021-06684-2 (2023).

Almeida, F. T., Gianoni-Capenakas, S., Rabie, H., Figueiredo, R. & Pacheco-Pereira, C. The use of panoramic radiographs to address the oral health needs of vulnerable Canadian populations. Can. J. Dent. Hyg. 58, 19–25 (2024).

Mohammad, R. Orthodontic evaluation of impacted maxillary canine by panoramic radiograph-A literature review. J. Res. Med. Dent. Sci. 9, 220–227 (2021).

Schwendicke, F. & Göstemeyer, G. Conventional bitewing radiography. Clin. Dent. Rev. 4, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41894-020-00086-8 (2020).

Kamburoğlu, K., Kolsuz, E., Murat, S., Yüksel, S. & Özen, T. Proximal caries detection accuracy using intraoral bitewing radiography, extraoral bitewing radiography and panoramic radiography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 41, 450–459. https://doi.org/10.1259/dmfr/30526171 (2012).

Mongkolwat, P., Kleper, V., Talbot, S. & Rubin, D. The National cancer informatics program (NCIP) annotation and image markup (AIM) foundation model. J. Digit. Imaging. 27, 692–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10278-014-9710-3 (2014).

Jocher, G. et al. ultralytics/yolov5: v7.0 - YOLOv5 SOTA realtime instance segmentation. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7347926 (2022).

Hamamci, I. E. et al. DENTEX: an abnormal tooth detection with dental enumeration and diagnosis benchmark for panoramic x-rays. ArXiv abs/2305.19112 (2023).

Hamamci, I. E. et al. in International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention.

Oktay, O. et al. Attention U-Net: learning where to look for the pancreas. ArXiv (2018). abs/1804.03999.

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-Net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. ArXiv Abs. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1505.04597 (2015). /1505.04597.

Zhou, Z., Siddiquee, M. M. R., Tajbakhsh, N., Liang, J. & UNet++: A nested U-Net architecture for medical image segmentation. Deep Learn. Med. Image Anal. Multimodal Learn. Clin. Decis. Support. 11045, 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00889-5_1 (2018).

Cao, H. et al. Swin-Unet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. ArXiv arXiv:2105 05537. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2105.05537 (2021).

Alom, M. Z., Hasan, M., Yakopcic, C., Taha, T. M. & Asari, V. K. Recurrent residual convolutional neural network based on U-Net (R2U-Net) for medical image segmentation. ArXiv arXiv. 180206955. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1802.06955 (2018).

Chen, J. et al. TransUNet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. ArXiv. arXiv:2102.04306, (2021). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2102.04306

Conger, A. J. Kappa and rater accuracy: paradigms and parameters. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 77, 1019–1047. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164416663277 (2017).

Dogan, N. O. Bland-Altman analysis: A paradigm to understand correlation and agreement. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 18, 139–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjem.2018.09.001 (2018).

Bayrakdar, I. S. et al. Deep-learning approach for caries detection and segmentation on dental bitewing radiographs. Oral Radiol. 38, 468–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11282-021-00577-9 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Children’s dental panoramic radiographs dataset for caries segmentation and dental disease detection. Sci. Data. 10, 380. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02237-5 (2023).

Dayı, B., Üzen, H., Çiçek, İ. B. & Duman, Ş. B. A novel deep learning-based approach for segmentation of different type caries lesions on panoramic radiographs. Diagnostics 13, 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13020202 (2023).

Lian, L., Zhu, T., Zhu, F. & Zhu, H. Deep learning for caries detection and classification. Diagnostics 11, 1672. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11091672 (2021).

Keenan, J. R. & Keenan, A. V. Accuracy of dental radiographs for caries detection. Evid. Based Dent. 17 https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401166 (2016).

Schwendicke, F., Tzschoppe, M. & Paris, S. Radiographic caries detection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dent. 43, 924–933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2015.02.009 (2015).

Terry, G. L., Noujeim, M., Langlais, R. P., Moore, W. S. & Prihoda, T. J. A clinical comparison of extraoral panoramic and intraoral radiographic modalities for detecting proximal caries and visualizing open posterior interproximal contacts. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 45, 20150159. https://doi.org/10.1259/dmfr.20150159 (2016).

Chen, Q. et al. Automatic and visualized grading of dental caries using deep learning on panoramic radiographs. Multimedia Tools Appl. 82, 23709–23734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-022-14089-z (2023).

Alharbi, S. S., AlRugaibah, A. A., Alhasson, H. F. & Khan, R. U. Detection of cavities from dental panoramic x-ray images using nested U-Net models. Appl. Sci. 13, 12771. https://doi.org/10.3390/app132312771 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Assoc. Prof. Supanee Thanakun, College of Dental Medicine, Rangsit University, and Ms. Pairin Tonput, Academic Statistician, Research Office, Faculty of Dentistry, Mahidol University for their statistical analysis.

Funding

This paper was supported by Mahidol University and the Office of the Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation under the Reinventing University project: the Center of Excellence in AI-Based Medical Diagnosis (AI-MD) sub-project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.P.D. contributed to the conceptualization of work, design, data acquisition, data validation, data analysis, writing-original draft, writing & editing manuscript, final approval of the version to be published; S.V. contributed to the conceptualization of work, design, writing AI model algorithm, data analysis, writing & editing manuscript; D.P. contributed to the design, data analysis and interpretation, editing manuscript; J.R. contributed to the design, data acquisition and calibration, editing manuscript; S.C. contributed to data acquisition and methodology, editing manuscript; R.W. contributed to the design, data acquisition and calibration, editing manuscript; P.M. contributed to the conceptualization of work, design, data analysis, critically revised the manuscript and figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participates were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The need for informed consent to participate was waived by the Ethics Committee of Mahidol University Multi-Faculty Cooperative IRB Review (MU-MOU CoA.2022/060.1511).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pornprasertsuk-Damrongsri, S., Vachmanus, S., Papasratorn, D. et al. Clinical application of deep learning for enhanced multistage caries detection in panoramic radiographs. Sci Rep 15, 33491 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16591-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16591-4