Abstract

Nature-based solutions (NbS) can mitigate the climate crisis and provide co-benefits to biodiversity and human well-being. We identified opportunities for NbS in the US by mapping both critical habitat for birds under a changing climate and carbon stocks and sinks. We then investigated the alignment of these locations with areas important for human well-being and land-dependencies. Finally, we identified High Priority NbS areas that align with irrecoverable carbon to focus conservation efforts on places with significant long-term carbon storage potential. Although ~ 30% of US lands have some protection, < 3% of protected US lands align with priorities for birds, carbon, and human well-being. Of the 312 million acres of priority areas for birds, carbon, and human well-being identified, 71% lack legal protection or formal conservation plans (14% of US lands). Targeting such areas for NbS conservation and restoration would help achieve equitable climate benefits by guiding conservation investments to marginalized communities, while also ensuring maintenance of lands that are critical for biodiversity tracking a changing climate. At least 80% of all birds, carbon, and human well-being priorities co-occur with local communities who have cultural and socioeconomic ties to the land, making it imperative to work with these communities to achieve successful conservation outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Habitat loss and climate change are two of the most pervasive and detrimental threats to biodiversity globally1,2,3. Climate change contributes to species declines4,5,6,7as a consequence of range loss and/or exposure to climate change-related threats8,9,10,11,12. Furthermore, conversion of natural ecosystems has accelerated climate change by contributing up to 20% of the world’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions through released carbon into the atmosphere13.This number is expected to increase as continued warming leads to accelerated carbon loss13. These dual climate change and biodiversity global crises require urgent solutions. Conserving natural habitats through the implementation of Nature-based Solutions (NbS) is a promising strategy for simultaneously addressing both crises while providing additional ecosystem services14,15. The IUCN broadly defines NbS as actions that protect, sustainably manage, and restore both natural and modified ecosystems to address societal challenges and benefit both people and nature (https://iucn.org/our-work/nature-based-solutions). Restoring or maintaining natural ecosystems under an NbS framework can provide co-benefits to people, including clean and abundant drinking water from healthy watersheds; increased productivity from healthy soils; flood control from functioning wetlands; and temperature moderation from healthy forests15,16. Understanding where opportunities for NbS occur, including natural areas with high carbon sequestration and sinks that align with key areas for biodiversity currently and under future climate change, as well as the impacts they may have on human well-being in those areas, should be a priority in area-based conservation17. Global conservation area-based targets, such as Target 3 of the 23 targets under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF) to protect 30% of lands and water by 2030 (hereafter ‘30 × 30’), and the Global Deal for Nature to protect 50% by 2050 (‘Half-Earth’), are focused on reversing biodiversity loss through the conservation and restoration of natural areas18. Most protected areas in the US have been established for geological or scenic preservation, with little focus on biodiversity or climate change19,20,21. While ~ 30% of continental US lands (including Alaska) are considered formally protected, indicating we are already at the 30% target on paper, in practice, the majority of these lands are managed for multiple uses and were not established with biodiversity goals in mind. Moreover, the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities have historically been overlooked22,23. There is a growing consensus for the need to consider more than a nominal protection designation of pre-defined acreage targets, including elevated focus on simultaneous biodiversity conservation and ecosystem services such as carbon mitigation (i.e. protection of carbon stores and sinks) in conservation planning (see Target 3 under the KMGBF; https://www.cbd.int/gbf/targets/3). Thus, mapping areas of high value for NbS will guide area-based conservation efforts, and on-the-ground NbS implementation17,23,24.

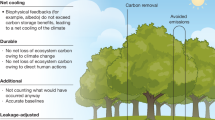

The few analyses that identify ‘optimal’ NbS focused conservation portfolios that maximize biodiversity and carbon benefits simultaneously often overlook the rights of people living in these areas, as well as the implications of traditional land conservation and protection designations for displacing people and current land uses. Currently, NbS implementation has been criticized for a lack of inclusive participation or capacity to foster change that is transformative25. Notably, area-based conservation targets, such as 30 × 30 and Half-Earth26,27,28, have the potential to perpetuate environmental injustices if consideration of human well-being and livelihoods are ignored29. Conservation without community co-development and support is likely to be ineffective30. In addition, consideration of other area-based conservation measures beyond protected and conserved lands, such as sustainable management, should be integrated into NbS planning efforts. This includes engaging local communities and private landowners in land governance and management activities that achieve positive and sustained outcomes for biodiversity and ecosystem services, while also respecting locally-relevant values and rights31. Given the interconnectedness of climate change, biodiversity loss, and human well-being, a holistic solution with an emphasis on the human communities at highest risk from climate change and land degradation who have historically been marginalized, and even victimized, is critical in conservation planning. Additionally, access to natural areas in the US has been shown to have disparities across race, socioeconomic status, and housing composition, with People of Color and low-income communities being grossly underrepresented32,33. Access to nature can influence overall human health and well-being and foster opportunities for green economic development32,34. Governing bodies have historically ignored social and environmental justice and disregarded how marginalized human communities (e.g., Indigenous groups and Black and brown communities) are included or engaged in setting large-scale conservation targets27,35. Understanding who lives in priority restoration areas and how they may be affected by NbS and land management decisions, is critical for reaching successful and equitable conservation outcomes36. This includes marginalized and historically excluded communities, as well as communities affected by changes in local land management, including those with land-dependent livelihoods, cultural importance factors such as sustenance and spirituality, or risk of green gentrification25; hereafter, these groups are referred to as Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs).Though nearly 30% of US lands are currently within the protected area network, it remains unclear how well these lands help us achieve goals for biodiversity and climate change, and to what extent they account for human well-being. We must identify where conservation action provides maximum return on investment for biodiversity and climate change and who will benefit or be engaged in the process37. Here, we propose a spatially-explicit, conservation framework for integrating multiple priorities into a spatial assessment of NbS-focused, area-based targets (Fig. 1). This framework identifies the spatial distribution of areas that are important for NbS (i.e., biodiversity and climate change mitigation) as well as the human communities whose well-being and land-dependent livelihoods could be impacted by conservation actions, within the context of area-based conservation targets. We focus on birds as representatives of biodiversity, as they are monitored globally and can be effective indicators of overall biodiversity when conservation planning spans many species, habitats, and environmental gradients38,39. We then focused in on areas within the human purview to manage that have high irrecoverable carbon stores40and where they coincide with high value areas for birds, carbon, and human communities, to identify locations prime for NbS action. We focused on the continental United States (US), but this framework can be applied at any scale from local to global. These national maps can be used in combination with local datasets and in partnership with IPLCs to identify what counts toward the 30% goal under 30 × 30 and to design local, state or regional conservation plans that simultaneously address biodiversity, climate change, and the needs of human communities. This approach identifies High Priority NbS Areas across the US to help guide conservation efforts where they are most needed, with social-ecological considerations at the forefront of decision-making41 (Fig. 1).

Conceptual diagram of how Bird, Carbon, and Human priorities (BCH priorities), areas of alignment between bird climate strongholds, areas important for carbon storage and sequestration, and vulnerable human communities facing inequities (opportunities to equitably improve human well-being), are classified as, (A) priorities to maintain and (B) priorities to restore, based on the overlap of conservation priorities for birds (pink), carbon (green), and human well-being (yellow). Priorities to maintain are areas where Climate Strongholds and existing carbon stores and sinks are actively benefiting bird species resilience and carbon mitigation. Priorities to restore are areas where Vulnerable Climate Strongholds and potential areas for additional carbon storage and sequestration have potential benefits to bird resilience and carbon mitigation if restored. In each scenario (A and B), we focus on two areas of NbS overlap (1) alignment of Climate Strongholds and carbon priorities (benefits to Bird and Carbon: BC priorities) and (2) alignment of all three priorities (benefits to birds, carbon, and humans: BCH priorities). For both BC and BCH priorities to maintain and restore, we also consider areas with IPLCs considerations (i.e., BC + IPLCs and BCH + IPLCs) as additional priority area types (not shown).

Results

Bird and carbon priorities

We identified 1.1 billion acres of Bird and Carbon (BC) priorities to maintain existing habitats or restore habitats using NbS across all seven ecosystems examined (Fig. 2). A total of 74% of BC priorities occur on unprotected land with no conservation mandate (see Supplementary Table S4). These are potential opportunities under 30 × 30 to conserve biodiversity and mitigate carbon, comprising 43% (980 million acres) of the US (Table 1; Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S5). Currently 13% (305 million acres) of the continental US is under strict formal protection (GAP 1–2), with an additional 18% (410 million acres) under multiple-use conservation protection (GAP 3, Table 1). Thus, nearly three-fourths of the US (69%) lacks any formal protection. Nearly 50% of current GAP 1–2 protected lands coincide with BC priorities (Table 1; Fig. 3), which equates to 6% of US lands (143 million acres) that could count towards the 30 × 30 target (Table 1; Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S5). Currently, 48% of GAP 3 managed lands overlap with BC priorities, equating to 9% of US lands (200 million acres) that provide additional opportunities for increased protection and could count towards 30 × 30 while benefiting birds and carbon (Table 1; Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S5).

US lands identified with the highest potential for NbS focused on birds and carbon (BC priorities), as well as potential to promote equitable human well-being (BCH priorities) if maintained or restored. Darker color tones indicate conservation priorities occurring in communities that rely on the land for cultural preservation and/or socioeconomic factors (BC + IPLCs and BCH + IPLCs). This map was created using ESRI ArcPro 3.2.2 (https://pro.arcgis.com/).

US lands identified with the highest potential for NbS focused on birds and carbon (BC priorities), as well as potential to promote equitable human well-being (BCH priorities) if maintained or restored according to their current GAP status. Darker color tones indicate conservation priorities occurring in communities that rely on the land for cultural preservation and/or socioeconomic factors (BC + IPLCs and BCH + IPLCs). This map was created using ESRI ArcPro 3.2.2 (https://pro.arcgis.com/).

Priorities for human Well-Being

A total of 19% of US lands (438 million acres) align with BC priorities and are also within communities identified as priorities for human well-being (BCH priorities; Table 1; Fig. 2). A quarter of the US population lives in communities with these BCH priorities (hereafter “BCH communities”). Less than 3% of US lands are currently protected BCH priorities (Table 1). Of the 438 million acres of BCH priorities, 71% are unprotected and 15% are within GAP 3 designation. These lands sum to 380 million acres of conservation opportunity across the continental US (or 14% and 3% of the US, respectively; Table 1) with potential co-benefits for people.

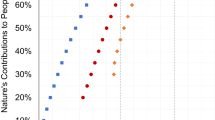

Furthermore, BCH communities had high community inequities, including less access to nature (91% of the population in BCH communities), followed by chronic health conditions (73%), pollution exposure (62%), and high exposure to climate change risk (47%) (Fig. 4b). Overall, 95% of populations in BCH communities face multiple inequities in each region of the US (Fig. 5). Community inequity was high in the Southern Great Plains, Northern Great Plains, and Southeast although the inequity patterns varied regionally (Figs. 4b and 5).

(A) The percent prevalence of Indigenous peoples’ and local communities’ (IPLCs) considerations (green gentrification potential, Indigenous land, or natural resource [NR] industry occupations) within populations of land-dependent communities that overlap Bird and Carbon priorities. (B) The percent prevalence of human inequities (climate, health, pollution, or nature access) within populations of socially vulnerable communities that overlap Bird and Carbon conservation priorities (priorities for birds, carbon, and human well-being [BCH]). Percentages are relative to the estimated populations summed across census tracts within each US region.

Bird and Carbon (BC) conservation priorities overlap with human communities experiencing co-occurring inequities. This map shows the number of co-occurring inequity indicators (including climate, pollution, health, and nature access) experienced by the human communities overlapping BC priority areas. Geographic region boundaries are shown in black line. This map was created using ESRI ArcPro 3.2.2 (https://pro.arcgis.com/).

IPLC considerations

Across all communities with BC Priorities, IPLCs considerations affected a greater percentage of the population (36%) than community inequities (30%). Of the 1.32 billion acres of BC priorities in the US, regardless of protection status, 80% (1.12 billion acres) also have indicators of IPLCs considerations (i.e., BC + IPLCs priorities) and 29% (387,083,039 acres) are in communities with inequitable human well-being in addition to having IPLCs considerations (i.e., BCH + IPLCs priorities; Supplementary Table S4). A total of 72% (764 million acres) of BC + IPLCs priorities and 69% (269 million acres) of BCH + IPLCs priorities are unprotected, with an additional 17% and 16% in GAP 3 lands, respectively (Supplementary Table S5). Across the continental US, 43% of GAP 3 lands coincide with BC + IPLCs areas and 15% coincide with BCH + IPLCs areas (the percentage of GAP3 in these priorities out of the total US GAP3 area, Table 1, Supplementary Table S5).

Of the population living within BC priorities and IPLCs, the majority depended on the natural resource industry (63%). Natural resource industry dependence was highest in the central and western regions, and lowest in the east (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Table S6). Green gentrification was the next most prevalent indicator, affecting 37% of the population across the US, but percentages were greatest in the Northeast (59% of population), Southwest (46% of population), and Southeast (43%; Fig. 4a, Supplementary Table S6). A total of 10% of this US population (BC + IPLCs, and up to 70% in Alaska) resides in communities that share a mix of legal boundaries belonging to tribal and non-tribal governments, and state and federally recognized American Indian lands. Populations with high potential for green gentrification were more prevalent in priorities to restore, while populations associated with Indigenous land and natural resource industry were higher in priority areas to maintain (Supplementary Table S6).

High priority NbS areas

We identified 261 million acres (11.7% of US lands) of High Priority NbS Areas (Fig. 6) as all combined BC priorities (BC, BCH, BC + IPLCs, and BCH + IPLCs) that align with areas of highest irrecoverable carbon density (i.e., areas of high value carbon stores that are under direct human influence and are crucial for climate mitigation success, thus providing an ideal data layer for prioritizing NbS action)40. We highlight these areas to differentiate regions of the highest priority to better support conservation decision-making within a NbS framework, and to direct efforts of highest potential climate mitigation value when conservation resources are limited. Looking across these High Priority NbS Areas, this includes 53 million acres (2.4% of US lands) of BC priorities, 121 million acres (5.4% of US lands) of BC + IPLC priorities, 10 million acres (0.5% of US lands) of BCH priorities, and 77 million acres (3.5%) of BCH + IPLCs priorities. High Priority NbS Areas are primarily distributed in the Northwest, Northeast, and Southeast regions, where forests, wetlands, and coastal areas contain large amounts of irrecoverable carbon (Fig. 6). A total of 80% of High Priority NbS Areas align with priorities for human well-being, with most of those areas (76%) with IPLCs considerations.

US lands identified as High Priority NbS Areas that align both with the highest potential for NbS focused on birds and carbon (BC priorities), as well as potential to promote equitable human well-being (BCH priorities) if maintained or restored and fall within the footprint of irrecoverable carbon density. These areas are the highest priority to better support conservation decision-making within an NbS framework. Darker color tones indicate conservation priorities located in communities that rely on the land for cultural preservation and/or socioeconomic factors (BC + IPLCs and BCH + IPLCs). This map was created using ESRI ArcPro 3.2.2 (https://pro.arcgis.com/).

Discussion

Currently, of the 13% of US lands with a strict legal mandate for biodiversity protection (here, Gap 1 and Gap 2 lands), only 6% align with BC priorities and < 3% overlap with BCH priorities, revealing that we have not been successful to date at representing NbS priorities within our current protected area portfolio. Here, we identified an additional 980 million acres (43% of US lands) of unprotected land with potential opportunities for NbS to conserve BC priorities, and nearly 312 million acres (14% of US lands) representing opportunities to conserve BCH priorities. Here, NbS conservation efforts must go beyond traditional protection, and include actions such as sustainable land management and collaboration with private landowners14. Focusing NbS conservation efforts on these lands would meet 30 × 30 goals and help address the dual climate and biodiversity crises17,42, while simultaneously benefitting human communities.

Meeting 30 × 30 targets by increasing or adding protections to existing multiple-use areas (GAP 3) covering nearly 18% of US lands e.g.23 would fail to maximize the benefits of NbS and improve human equity, despite 49% of GAP 3 lands having high value for birds and carbon (totalling 9% of US lands). In addition, we found only 19% of US lands with conservation protection, and 17% of multiple-use lands that also align with BCH priorities (each covering just under 3% of US lands). Protected areas historically have not been designated with biodiversity, climate change or equitable human well-being in mind. More so, traditional conservation practices have been focused on optimizing resource extraction or preserving recreational, scenic, or geological value on land that has been colonized19,20,21,43. These same practices have also led to restricted access to protected lands and lack of inclusion in conservation decision-making, with the brunt of the inequity falling on communities of color, rural communities, and IPLCs43. Therefore, we must look beyond the current protected lands system to meet 30 × 30 targets with NbS in mind.

Here, we identified nearly 14% of currently unprotected US lands where NbS-focused conservation could improve equitable human well-being alongside BC priorities (i.e., BCH priorities). Our results indicate 95% of socially vulnerable populations located in BC priorities face multiple inequities, including 91% without adequate access to nature, and > 70% with chronic health conditions, which is consistent with other work demonstrating that communities of color in the US live in areas with more human modification33 and less access to nature32. Given that access to green spaces promotes increased physical activity and mental health, and thus improves human well-being32,34, prioritizing conservation efforts and NbS within these highly modified habitats would likely benefit human well-being in addition to biodiversity and climate mitigation. For example, NbS conservation and restoration action could focus on regions with relatively high community inequity, including areas in the Southern Great Plains, Northern Great Plains, and Southeast (Fig. 5). Focusing on NbS conservation and restoration actions in these regions can help fuel a ‘restoration economy’, providing localized social and economic benefits to local communities and economies44.

Conservation actions in these priority areas will necessitate working closely with IPLCs to develop conservation solutions that support their well-being and land dependency needs and count towards 30 × 30. We found 80% of BC priorities fall within IPLCs (BC + IPLCs priorities), and most of these lands are not currently protected. The high overlap of these areas is key for addressing biodiversity loss and climate change and highlights the importance of conservation actions that account for people’s cultural values and livelihoods. This includes strategies such as integrating ethical considerations into conservation triage, an approach which traditionally prioritizes areas based on conservation urgency where resources are finite45. However, this approach generally does not consider social-ecological connections46. The High Priority NbS Areas identified here allow conservation practitioners to focus on the areas of highest importance for birds, in conjunction with where irrecoverable carbon stores are at risk of being lost without conservation actions. However, 80% of these High Priority NbS Areas fall within areas of low human well-being and numerous IPLC considerations. Effective conservation triage in these areas needs to account for social-ecological challenges46. Adaptive governance and knowledge co-production are essential components of conservation planning that deliver effective and ethical outcomes for human well-being as well as biodiversity, and climate mitigation46.

We considered three IPLCs attributes that have been historically affected by conservation and land protection decisions, acknowledging that several more IPLCs attributes could be considered and thus, our estimates of conservation areas in need of IPLCs actions are likely an underestimate. 30 × 30 has set a target to inclusively conserve and restore, and explicitly recognizes many human uses of lands and waters can benefit natural systems including working lands47. This is an important framing, as even with expansion of protected areas, biodiversity loss and extinction rates continue to remain high48.Therefore, protection status alone does not guarantee conservation success without additional management actions49,50,51. Within the context of climate change, proactive management strategies need to be implemented to continuously adapt to changing environmental conditions52,53,54. As part of this approach, we must engage private landowners in conservation, NbS, and stewardship of the land in a manner that can sustain both nature and the people that depend on it31. This includes working closely with private landowners in rural and working lands, as 63% of our IPLCs within BC priorities (77% when only considering IPLCs with BC priorities to maintain, Supplementary Table S6) are employed in the natural resource industry across all regions and priorities in our study. Working lands, if managed appropriately, can be successful NbS and beneficial for both carbon sequestration14,15 and biodiversity conservation55. Conservation practitioners can help support communities in sustainable management of local natural spaces56 by developing and maintaining programs that incentivize NbS. Market-based approaches that encourage the restoration or maintenance of natural land cover, as well as provide guidance on extractive practices that minimize biodiversity and carbon loss, can be key strategies for tackling the climate and biodiversity crises in conjunction with supporting the livelihoods of local communities. For example, ranchers can implement grazing practices that are bird-friendly, thereby promoting resilient grassland bird communities57, while simultaneously increasing the market value of the beef produced via bird-friendly land certifications. These strategies will be particularly critical in the Northern and Southern Great Plains, Alaska, Northwest, and Midwest, where communities with BC priorities have high dependence on natural resources for livelihoods. Private lands are crucial for both sustaining biodiversity and climate change mitigation, and thus local and co-produced conservation solutions that move beyond singularly relying on traditional protected area mandates will be critical going forward31,37,55.

Focusing on collaborations supporting and enhancing Indigenous land management or community-led protected area establishment may offer a path towards reaching 30 × 30 conservation targets that benefits human well-being and elevates Indigenous land rights. First, Indigenous lands are home to 10% of the US population within IPLCs with BC priorities, but this proportion was as high as 70% in Alaska. Given dispossession and forced migration, Indigenous lands have been reduced by nearly 99% of their historic extent58. However, Indigenous-managed lands have been shown to have greater vertebrate species richness and threatened species richness than protected areas. This highlights the importance of Indigenous land management, stewardship, and knowledge to conservation59,60,61. The human impact of conservation decision-making will also be strong in priority areas to maintain, as we found both natural resource industries and Indigenous populations were higher within these areas. Given the legacy of displacement and protection of land without collaboration within areas of high conservation value such as these, key conservation opportunities should be identified in partnership with IPLCs.

Green gentrification - the greening of urban spaces that leads to increased property values and subsequent displacement of low-income residents62- warrants particular attention given the likelihood of human displacement associated with restoration or wilding efforts in urban settings63. Roughly 37% of BC + IPLCs communities across all regions were at risk of green gentrification, especially within the southern and eastern US. This risk was notably higher within priority areas to restore across all regions. Conservation practitioners must acknowledge that NbS restoration projects can both improve human well-being and have unintended consequences for local communities. New urban green areas have been associated with declines in populations of People of Color, indicating that in some cases, ecosystem restoration or natural climate solutions/NbS resilience projects may cause unintended consequences for vulnerable communities64. The risk of displacement may be highest in areas vulnerable to climate change (e.g. high sea-level rise risk areas), especially close to downtown locations and near active transportation lines64,65. The focus should be on identifying where urban neighborhoods align with areas for potential conservation and resiliency projects and working with local communities to understand where and how to undertake such efforts63. This includes identifying and implementing anti-displacement tools (e.g., community land trusts) to secure affordable housing in the vicinity of conservation projects and ensuring that conservation projects are desired by the local community prior to their commencement63,64.

While our findings and conclusions offer a quantitative framework of the ongoing challenges facing equitable conservation planning, we acknowledge that conservation planning inherently requires many subjective decisions, values, and objectives. Variation in input values or threshold choice can yield different priority areas. While we recognize this introduces bias, an assessment of that bias was not our goal, and several other studies have addressed the effects of different weighting, thresholds, and valuation schemes in conservation assessments66,67,68,69,70. In addition, we used commonly applied and recommended thresholds in all analyses (see Methods). Our approach exemplifies only one potential avenue for the strategic implementation of NbS under 30 × 30. Other approaches may consider terrestrial biodiversity, climate corridors, climate velocity metrics67, or different societal values (e.g., natural capital assets, cultural services71 or IPLCs that are nature dependent72 and could be affected by conservation actions. Thus, we offer our analysis as a starting point for the continued development of a socio-environmental approach to conservation planning designed to address the most pressing human and environmental crises of our time.

Conclusions

Here, we provide a spatial framework for integrating values of both conservation and human communities within the context of NbS focused, area-based conservation41. To stabilize and reverse the biodiversity and climate crises, places of high value for birds that align with ecosystem carbon storage and sequestration are recommended as high priority for NbS conservation actions, particularly those located within High Priority NbS Areas. Yet, we recognize that local communities may be at odds with these identified priorities, especially those dependent on the land for their livelihoods and cultural practices. In such cases, conservation planning should account for the needs of the community and the desired conservation outcomes56,73, and should include ethical conservation triage practices. As progress is made towards 30 × 30 goals, the most successful conservation plans will promote human well-being alongside actions that restore and conserve nature and help stabilize our climate. We must shift away from historical practices that have excluded Indigenous communities for the sake of “protection” and perpetuated green gentrification that marginalizes people with low socioeconomic status (largely Black and Brown populations). Ongoing and future conservation within the current global context must be strategic, and ambitious, but also intentional and inclusive, ensuring local communities and conservation practitioners work together towards mutual goals.

Methods

Framework

We identified NbS priorities, or areas of opportunity to benefit biodiversity, climate mitigation, and human communities. Key terms and definitions for each are provided in Supplementary Table S1. These refer to areas identified by our method as priorities, a definition commonly used in literature on spatial prioritization for biodiversity conservation (see citations, all of which refer to areas identified by their methods as “priorities” or “priority areas”)42,66,67,74. These areas are a function of our analytical decisions and objectives and thus do not represent the only priorities to be considered in 30 × 30 conservation planning. First, to identify areas that meet dual conservation targets for both birds and carbon (BC priorities), we mapped Existing NbS Areas, or areas of high carbon storage and active carbon sinks that align spatially with Climate Strongholds, which we defined as areas important for birds today and under future climate change scenarios. We defined these NbS alignment areas as Bird and Carbon priority areas to maintain, where protection or sustainable management and conservation actions should be implemented to protect key carbon stores and sinks in areas of high value to birds (Fig. 1). We also identified Potential NbS Areas, or areas with high potential to act as carbon sinks if anthropogenic disturbance is minimized, which align with Vulnerable Climate Strongholds, defined as Climate Strongholds at high risk of conversion or with currently high levels of conversion and degradation. We refer to these NbS areas of alignment as Bird and Carbon priorities to restore, where restoration has the highest potential to improve carbon storage, sequestration, and bird habitat (Fig. 1). Together, these areas were identified as Bird and Carbon priorities (BC priorities). Next, we assessed the alignment of these BC priorities with spatial data on marginalized communities across the US to identify areas where conservation efforts could simultaneously benefit biodiversity, climate change, and equitable human well-being, and designated these areas Bird, Carbon, and Human priorities (BCH priorities; Fig. 1). These areas provide the greatest NbS co-benefit value. Here we identify opportunities to address human well-being by focusing on socially vulnerable communities, based on socio-economic considerations in addition to having at least one more inequity indicator in the following categories: climate change, pollution, health, and access to nature. Next, we assessed how these NbS priorities intersect with IPLCs, defined here as Indigenous peoples, and non-Indigenous communities with land-dependent livelihoods or cultural importance indicated by a prevalence of employment in the natural resources industry and lower-income urban households prone to displacement due to green gentrification (BC + IPLCs priorities and BCH + IPLCs priorities). The spatial analyses used to identify BC and BCH priorities were conducted using R statistical language (version R-4.1.3)75. Finally, we differentiated regions of the highest conservation priority to better support conservation decision-making by intersecting BC priority areas with areas of high irrecoverable carbon density (see High Priority NbS Areas, data description below). We defined these as High Priority NbS Areas, and provided a breakdown of BC, BCH, BC + IPLCs, and BCH + IPLCs that occur within the overlapping area. Irrecoverable carbon has elevated importance for climate mitigation and Nbs actions, as these locations host key carbon stores under direct human influence that, if lost, could not be recovered in a meaningful timeframe for addressing climate impacts40.

Bird priorities: climate strongholds

Data description

We identified Climate Strongholds and Vulnerable Climate Strongholds for birds in 17 biogeographical groups as per69 using an optimization approach implemented with Zonation conservation planning software76. Birds were represented by previously published species distribution models developed by Bateman et al.11 at a 1-km resolution across North America for a baseline period (1981–2010) and for three future time periods (2020s, 2050s, and 2080s) under Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 8.5. For a list of species associated with each biogeographical group, please see Supplementary Table S2. The 17 biogeographical groups were based on habitat affiliations for 557 bird species (see Supplementary Table S2) and NbS focus areas11, as per15,69 for seven ecosystems (forests, grasslands and rangelands, aridlands, interior wetlands, coastal wetlands, tundra, and urban and suburban systems) across four major regions of the continental US (eastern, central, western, and Alaska). For each biogeographical region (e.g. eastern forests), we calculated the spatial extent of each ecosystem in each time period based on both current and future land cover projections that incorporated climate change, sea level rise, and human population growth77,78,79,80,81,82,83.

Data analysis

We represented each species by its predicted suitability above a species-specific threshold as per11,69 and included projections from both breeding and nonbreeding seasons and all time periods under an ensemble of 15 GCMs as input features in Zonation. Following prior work to develop climate-informed bird prioritizations e.g.,1,69, we used the Core Area Zonation algorithm to rank the landscape based on current and future climate suitability for birds, habitat availability, and landscape condition. For all ecosystems we used the Global Human Modification Index84 to represent degradation due to human activities. For forests, we also incorporated the Forest Landscape Integrity Index85 by selecting the maximum value between the two indices to identify the greatest disturbance threat. We used the inverse of the index to represent landscape condition (i.e., high degradation = poor condition). We limited condition layers to the extent of each biogeographical group for each time-period, and associated species layers with the corresponding condition layer from each time-period using Zonation’s grouping function to capture habitat quality and availability. We used Zonation’s ecological interactions function to downweight locations farther than a species’ natal dispersal capacity for each time period1,86,87,88 up-weighted at-risk species (derived from NABCI conservation status scores and climate vulnerability scores; see Supplementary Table S2)11 and weighted present and near-future predictions higher than late-century predictions to address the increasing uncertainty of climate change projections over time89. To ensure that opportunities for conservation under 30 × 30 encompass ecologically distinct regions and are available across the continental U.S., we stratified rankings either by watershed boundaries (for coastal wetlands) or Bird Conservation Regions (for all other habitat groups; BCRs), the latter being distinct ecological regions with similar bird communities, habitats, and conservation issues90.

To identify Climate Strongholds, we selected the core (top 20%) and supporting biodiversity areas (top 40%-top 20%) of the landscape ranking91,92 within each ecosystem (with the exception of (sub)urban where we used the core area (20%) due to the broad footprint of this system and generalist nature of species included). We selected the top 20 and 40% thresholds as they have been shown to be robust thresholds that capture more individuals per species than areas of lower priority91,92. These top areas were predicted to have high climate suitability for birds and low human modification at present and/or under future climate change scenarios. To identify Vulnerable Climate Strongholds, we included both (1) areas not identified as Climate Strongholds but ranked in the top 40% of the prioritization when landscape condition was not considered (i.e., areas that have high climate suitability for birds but have been exposed to high amounts of human modification) and (2) areas in the top 40% of the difference between rankings with and without landscape condition (i.e., areas with the greatest potential to increase their value to birds if landscape condition was restored).

Carbon priorities

Data description

To identify existing and potential carbon priority areas, we identified locations with active (i.e., areas that currently function as significant carbon stores or sinks) and potential (i.e., areas that could have high carbon sequestration value if disturbance is minimized) carbon mitigation capacity. We used datasets from the Integrated Biosphere Simulator (IBIS) model to map carbon storage and flux (i.e., sequestration rate, or the annual amount of carbon exchange between an ecosystem and the atmosphere) in the contiguous US93. To map areas of high carbon storage, we used Total Ecosystem Carbon (TEC) from the latest year available (2015), which measures aboveground and belowground carbon up to two meters. To map areas of high carbon sequestration, we used Net Biome Productivity (NBP), which measures the realized annual rate of carbon exchange, incorporating human and natural disturbances. To identify areas with high potential for increased carbon sequestration, we mapped annual Net Ecosystem Productivity (NEP), or carbon flux in the hypothetical absence of natural or human disturbance, and calculated the difference between NBP and NEP. We recognize this may overestimate the area with potential for increased carbon sequestration given some ecosystems require natural disturbances; however, data distinguishing natural and anthropogenic carbon losses were not available.

To map carbon storage and flux in Alaska, we used data from the Scenarios Network for Alaska and Arctic Planning (SNAP) program based on the Terrestrial Ecosystem Model simulations for Alaska and Northwestern Canada, averaged during 2001-201094.

Data analysis

We summarized flux rates across the lower 48 from 1980 to 2015 to obtain the average and maximum sequestration rate over time (measured in tons of carbon per year). We summarized high and low estimates of flux rates, calculated as the difference between carbon sequestration continuing at average historical rates from 1980 to 2015 (low) versus maximum historical rates (high).

To calculate flux rates in Alaska, we subtracted heterotrophic respiration (HR) from vegetation Net Primary Productivity (NPP) to obtain NEP (net flux without accounting for loss due to disturbance (C/m2/yr). To calculate NBP (gC/m2/yr), we subtracted emissions due to disturbance (fire emissions from organic layer and vegetation burning) from NEP. Total carbon was calculated by summing the decadal average of soil and vegetation carbon pools (gC/m2).

We extracted carbon estimates within the biogeographical extent of the Climate Strongholds for each of the 17 biogeographical groups. We included all areas also mapped in the corresponding IBIS time series dataset of the dominant land cover class (i.e., forests, grasslands and rangelands, and aridlands) to ensure the carbon data aligned with the appropriate habitat. Existing NbS areas included areas in the top 20% of TEC for each ecosystem or that had a positive flux based on NBP, indicating these areas currently have high carbon storage capacity or are actively sequestering more carbon than they emit. We chose the 20% threshold for carbon to be comparable, and for assessing potential spatial overlap, with our Climate Strongholds, based on best practices in prioritization assessments looking at multiple conservation values17,95,96. Potential carbon priority areas included areas where NEP was greater than NBP, indicating these areas could sequester more carbon if disturbance was minimized. We did not adjust carbon sequestration estimates for albedo, but acknowledge that in some ecosystems, especially high latitude conifer forests, reduced albedo can lead to a warming effect that offsets carbon storage benefits97.

Bird and carbon priorities

Within each ecosystem, we identified NbS priorities as Bird and Carbon priorities to maintain (BC priorities, maintain), where Climate Strongholds overlap with Existing Carbon Priority Areas (Fig. 1). We considered these areas to have the greatest conservation benefit as they simultaneously help birds adapt to climate change while mitigating further carbon emissions. We also identified Bird and Carbon priorities to restore (BC priorities, restore) where Vulnerable Climate Strongholds aligned with Potential Carbon Priority Areas (Fig. 1). In Alaska, we only calculated BC priorities to maintain due to lack of available carbon data incorporating human disturbance. We merged each ecosystem level BC priority layer across the US into a single layer of priorities to maintain and a single layer of priorities to restore. We then overlaid BC maintain and restore priorities to create a single layer of BC priorities. As there was some overlap among habitats, any overlap between priorities to maintain and restore were considered priorities to maintain so as not to double count areas. Lastly, we assessed the current protected status within the different priorities within the context of US progress towards meeting the area-based conservation goal under 30 × 30.

Priorities for human well-being

Data description

We included five indicators of inequitable human well-being (hereafter “inequity indicators”) to identify where BC priorities aligned with opportunities for establishing equitable outcomes for human communities. We considered locations to have opportunities for improving equitable human well-being (hereafter “priorities for human well-being”) if communities were identified as socially vulnerable based on socio-economic considerations98 in addition to having at least one more inequity indicator in the following categories: climate change, pollution, health, and access to nature99. We obtained social data for human well-being from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) PLACES database100 and Social Vulnerability Index (SVI)98 which considers socio-economic status, household composition and disability, minority status and language barriers, housing type and transportation availability, the Council on Environmental Quality’s (CEQ) beta version of their Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST)99 and the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) environmental justice screening and mapping tool, EJScreen101. Data from these sources come from a range of multi-year estimates (i.e., American Community Survey 2014–2018 and 2015–2019 estimates), analyses, and collection years that fell within 2014–2021. In addition, health inequity indicators were based on 2019 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System community surveys that assessed both the present status of individuals (i.e., physical inactivity and mental health as of 2019) and health history of individuals (e.g., history of heart disease and diabetes throughout the individual’s lifetime). All our human well-being analyses were calculated within 2010 US Census Tract units (hereafter, “communities”).

Data analysis

To identify priorities for human well-being, we applied the methodologies used by the EPA and CEQ to highlight disadvantaged communities which they define as communities that are both (1) at or above the 65th national percentile for SVI, and (2) at or above the 80th national percentile for one (or more) inequity indicators. These thresholds were set by the EPA and the CEQ and are recommended to be used with their data products.

We created a health inequity indicator, which considered the four health conditions (crude prevalence of asthma, coronary heart disease, diabetes, and low life expectancy which were included in CEJST and two additional health conditions from the PLACES database: the prevalence of physical inactivity and poor mental health. We added the latter two conditions because physical activity and mental health have been directly linked to access to greenery and outdoor spaces102. If a community was ranked within the 80th percentile (as per EPA, see above) for any of these six health conditions, the tract was classified as having a health inequity.

To create a pollution inequity indicator, we combined several CEJST environmental burden indicators that focused on sources of pollution and non-clean infrastructure. These CEJST indicators were obtained from the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) EJSCREEN environmental indicators101. Communities were classified as having this indicator if they were above the 80th percentile for any of the following conditions: wastewater discharge, proximity to hazardous waste facilities, Superfund National Priorities List (NPL) sites, Risk Management Plan (RMP) sites, diesel particulate matter (PM) exposure, traffic proximity and volume, or PM 2.5 in the air.

To create an indicator of climate change risk inequity, we kept the same indicators used to measure climate burdens in CEJST: a community was classified as having climate inequities if it was within the 80th percentile for expected agricultural, building, or population losses due to natural hazards103. For an access to nature indicator, we intersected census tracts with the US Protected Areas Database (PADUS version 2.1)104 to identify communities without access to land formally protected for biodiversity (i.e., census tracts that did not intersect areas listed as GAP status 1–2 and Open Access in PADUS)104.

To identify BCH priorities, areas where priorities for birds, carbon, and human well-being overlapped, we intersected our priorities for human well-being with our BC priorities.

IPLCs considerations

Data description

We focused on IPLCs, a subset of human communities having the potential to be negatively affected by protected area designations and other conservation actions, given these communities depend on the land for cultural preservation and livelihoods. Such communities include those of Indigenous peoples, those with a high percentage of their population employed in the natural resources industry, and marginalized and low-income urban communities who are particularly prone to displacement due to green gentrification. Green gentrification is a complex issue, but a large component of long-term displacement is increased housing costs associated with green infrastructure63. Despite the variation in land-dependencies existing within and between these three groups (e.g., economic living standards, subsistence living, health and wellness, culture, and spirituality), all of these dependencies are linked to overall human well-being and are reasons for mandating the inclusion of these communities in land management decisions105,106.

For our IPLCs considerations, we used several data sources and retained our 80th percentile threshold for consistency with our inequity indicators. For the Indigenous land indicator, we identified communities intersecting Indigenous land boundaries from the US Census Bureau’s 2019 National American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian Areas (AIANNH) dataset107. These boundaries represent federally recognized American Indian reservations, off-reservation trust lands, state-recognized American Indian reservations, and state designated tribal areas. For the natural resources industry indicator, we included communities within the 80th percentile for the percent of their working population in the natural resources industry from the US Census Bureau’s 2016–2020 American Community Survey (ACS) 5-Year Estimates of Selected Economic Characteristics108. Natural resources industries include agriculture, forestry, fishing, hunting, and mining. Finally, for the green gentrification indicator, we included communities within urbanized area boundaries classified by the 2010 US Census109 that were also in the 80th percentile for the housing cost burden variable used in CEJST. Housing cost burden is the percent of households in each tract earning < 80% of the Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Area Median Family Income by county110 and are spending > 30% of their income on housing costs.

Data analysis

To identify priorities that may require IPLCs engagement in conservation planning, we identified communities having at least one IPLCs indicator (i.e., Indigenous land, natural resource industry, or green gentrification). We intersected these communities with our BC priorities and our BCH priorities and refer to these coincident areas as BC + IPLCs priorities and BCH + IPLCs priorities, respectively.

Protection status

Data description

To assess protected status for all priorities, we used GAP status, a measure of intent to conserve biodiversity classified as follows: GAP 1–2 are under permanent protection for conservation, GAP 3 is under protection but allows multiple uses and extraction, and GAP 4 has no known legal conservation mandate. Here, we classify GAP 1 and 2 lands as highly protected, given the mandate to protect biodiversity and natural land cover and exclude human resource extraction22,66,111. USGS Gap Analysis Project, 2018). Gap 3 and 4 designated lands as they currently are managed may be inadequate to conserve lands in a way that maintains biodiversity, carbon mitigation values, and/or support human well-being22. However, Gap 3 and 4 lands have the potential to be beneficial to biodiversity, climate mitigation value, and human well-being with some adjustments, such as changes in management practices, restoration efforts, and/or increased access to nature23.

Data analysis

We flattened the PADUS GAP status data layer104 across overlapping areas by retaining the highest level of protection for each area (i.e., the lowest GAP score), following methods in Dreiss & Malcom23 and considered non-PADUS lands as GAP 4 since their protected status is unknown. Although we designate GAP 4 as “unprotected”, we acknowledge these areas may have local mandates or private land ownership and management that are not captured by PADUS. We calculated the percent of the total land area within the continental US, within sub-national regions determined by the US Global Change Research Program (National Climate Assessment Regions (NCA4)112 and within the identified areas for each of our priorities classified as GAP 1–3.

High priority NbS areas

Data description

To identify High Priority NbS Areas that, if lost, would have the greatest negative impact relative to carbon storage, we identified Bird and Carbon Priority Areas with the highest levels of irreplaceable carbon reserves. We accessed high value irrecoverable carbon density from Noon et al.40. Irrecoverable carbon is defined as ecosystem carbon reserves that: (1) would not recover by mid-century if lost, (2) would benefit from human management, and (3) are vulnerable to land-use conversion40. Therefore, losing carbon in these areas would negatively impact our capacity to prevent worse-case scenario climate impacts. We did not include irrecoverable carbon as our original carbon dataset as it only covers areas that are ‘within ecosystems that are within human purview to manage’40 and thus did not give us full spatial coverage to identify areas of priority for carbon or biodiversity across the full continental US.

Data analysis

We clipped the global map of irrecoverable carbon to the continental US and calculated the median pixel value based on this extent (median value, 22 MgC \(\:{\text{h}\text{a}}^{-1}\)). We then extracted all pixel values above the median, creating a layer with the upper 50% of irrecoverable carbon areas in the continental US. We used this layer as a mask applied to the Bird and Carbon Priority Areas, with all data within the mask representing the priority areas with the highest amount of irrecoverable carbon. We then categorized this layer by Bird and Carbon Priority type and calculated total acreages. The resulting map depicts High Priority NbS Areas across the continental US.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available at Audubon Hub Link: https://gis.audubon.org/datalibrary/ and can be viewed interactively and data can be accessed and downloaded through Audubon’s Natural Climate Solutions online viewer: https://gis.audubon.org/naturalclimatesolutions Additionally, Bird and Carbon Priority areas to maintain or restore by habitat type can be accessed at https://services1.arcgis.com/lDFzr3JyGEn5Eymu/arcgis/rest/services/Audubon_Natural_Climate_Solutions_Master_Layer/FeatureServer.

References

Grand, J., Wilsey, C., Wu, J. X. & Michel, N. L. The future of North American grassland birds: incorporating persistent and emergent threats into full annual cycle conservation priorities. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 1, e20 (2019).

Jetz, W., Wilcove, D. S. & Dobson, A. P. Projected impacts of climate and Land-Use change on the global diversity of birds. PLOS Biol. 5, 1211–1219 (2007).

Segan, D. B., Murray, K. A. & Watson, J. E. M. A global assessment of current and future biodiversity vulnerability to habitat loss–climate change interactions. Global Ecol. Conserv. 5, 12–21 (2016).

Stephens, P. A. et al. Consistent response of bird populations to climate change on two continents. Science 352, 84–87 (2016).

Baranov, V., Jourdan, J., Pilotto, F., Wagner, R. & Haase, P. Complex and nonlinear climate-driven changes in freshwater insect communities over 42 years. Conserv. Biol. 34, 1241–1251 (2020).

Iknayan, K. J. & Beissinger, S. R. In transition: avian biogeographic responses to a century of climate change across desert biomes. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 3268–3284 (2020).

Soroye, P., Newbold, T. & Kerr, J. Climate change contributes to widespread declines among bumble bees across continents. Science 367, 685–688 (2020).

Bellard, C., Bertelsmeier, C., Leadley, P., Thuiller, W. & Courchamp, F. Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 15, 365–377 (2012).

Warren, R., Price, J., Graham, E., Forstenhaeusler, N. & VanDerWal, J. The projected effect on insects, vertebrates, and plants of limiting global warming to 1.5°C rather than 2°C. Science 360, 791–795 (2018).

Wilsey, C. et al. Climate policy action needed to reduce vulnerability of conservation-reliant grassland birds in North America. Conservation Science and Practice CSP2-18-0014, (2019).

Bateman, B. L. et al. North American birds require mitigation and adaptation to reduce vulnerability to climate change. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2, e242 (2020).

Bateman, B. L. et al. Risk to North American birds from climate change-related threats. Conservation Sci. Practice. 2 (8), e243 (2020).

IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5°C. (2018). http://www.ipcc.ch/report/sr15/

Griscom, B. W. et al. Natural climate solutions. PNAS 114, 11645–11650 (2017).

Fargione, J. E. et al. Natural climate solutions for the united States. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat1869 (2018).

Drever, C. R. et al. Natural climate solutions for Canada. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd6034 (2021).

Carroll, C. & Ray, J. Maximizing the effectiveness of national commitments to protected area expansion for conserving biodiversity and ecosystem carbon under climate change. (2020).

Dinerstein, E. et al. A global deal for nature: guiding principles, milestones, and targets. Sci. Adv. 5 (4), eaaw2869 (2019).

Aycrigg, J. L. et al. Representation of ecological systems within the protected areas network of the continental united States. PLoS One. 8, e54689 (2013).

Venter, O. et al. Targeting global protected area expansion for imperiled biodiversity. PLoS Biol. 12, e1001891 (2014).

Jenkins, C. N., Van Houtan, K. S., Pimm, S. L. & Sexton, J. O. US protected lands mismatch biodiversity priorities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 5081–5086 (2015).

Dreiss, L. M. et al. Targeting current species ranges and carbon stocks fails to conserve biodiversity in a changing climate: opportunities to support climate adaptation under 30 × 30. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 024033 (2022).

Dreiss, L. M. & Malcom, J. W. Identifying key federal, state, and private lands strategies for achieving 30 × 30 in the United States. Conserv. Lett. 15, e12849 (2022).

Goldstein, A. et al. Protecting irrecoverable carbon in earth’s ecosystems. Nat. Clim. Change. 10, 287–295 (2020).

Melanidis, M. S. & Hagerman, S. Competing narratives of nature-based solutions: leveraging the power of nature or dangerous distraction? Environ. Sci. Policy. 132, 273–281 (2022).

Büscher, B. et al. Half-Earth or whole earth?? Radical ideas for conservation, and their implications. Oryx 51, 407–410 (2017).

Schleicher, J. et al. Protecting half of the planet could directly affect over one billion people. Nat. Sustain. 2, 1094–1096 (2019).

Napoletano, B. M. & Clark, B. An ecological-marxist response to the half-earth project. Conserv. Soc. 18, 37–49 (2020).

Menton, M. et al. Environmental justice and the sdgs: from synergies to gaps and contradictions. Sustain. Sci. 15, 1621–1636 (2020).

Armitage, D., Mbatha, P., Muhl, E. K., Rice, W. & Sowman, M. Governance principles for community-centered conservation in the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2, e160 (2020).

Naugle, D. E., Allred, B. W., Jones, M. O., Twidwell, D. & Maestas, J. D. Coproducing Science to Inform Working Lands: The Next Frontier in Nature Conservation. BioScience 70, 90–96 (2020).

Wolch, J. R., Byrne, J. & Newell, J. P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: the challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landsc. Urban Plann. 125, 234–244 (2014).

Landau, V. A., McClure, M. L. & Dickson, B. G. Analysis of the Disparities in Nature Loss and Access to Nature. (2020).

Romagosa, F., Eagles, P. F. J. & Lemieux, C. J. From the inside out to the outside in: exploring the role of parks and protected areas as providers of human health and well-being. J. Outdoor Recreation Tourism. 10, 70–77 (2015).

Tallis, H. & Lubchenco, J. Working together: A call for inclusive conservation. Nature 515, 27–28 (2014).

Fleischman, F. et al. Restoration prioritization must be informed by marginalized people. Nature 607, E5–E6 (2022).

Lamb, R. L. & Schmidt, J. Nature-Based climate solutions require Us to answer the where and the who. J Sci. Policy Gov 18, (2021).

Fraixedas, S. et al. A state-of-the-art review on birds as indicators of biodiversity: advances, challenges, and future directions. Ecol. Ind. 118, 106728 (2020).

Lewandowski, A. S., Noss, R. F. & Parsons, D. R. The effectiveness of surrogate taxa for the representation of biodiversity. Conserv. Biol. 24, 1367–1377 (2010).

Noon, M. L. et al. Mapping the irrecoverable carbon in earth’s ecosystems. Nat. Sustain. 5, 37–46 (2022).

Vucetich, J. A. et al. Just conservation: what is it and should we pursue it? Biol. Conserv. 221, 23–33 (2018).

Stralberg, D. et al. Climate-change refugia in boreal North america: what, where, and for how long? Front. Ecol. Environ. 18, 261–270 (2020).

Rudd, L. F. et al. Overcoming racism in the twin spheres of conservation science and practice. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 288, 20211871 (2021).

BenDor, T. K., Livengood, A., Lester, T. W., Davis, A. & Yonavjak, L. Defining and evaluating the ecological restoration economy. Restor. Ecol. 23, 209–219 (2015).

Bottrill, M. C. et al. Is conservation triage just smart decision making? Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 649–654 (2008).

Martínez-Harms, M. J., Estévez, R. A. & Álvarez-Miranda, E. Conservation triage in action: planning, governance and knowledge co-production for biodiversity protection. J. Appl. Ecol. 61, 2328–2334 (2024).

Conserving and Restoring ‘America the Beautiful’. (2021).

Crist, E. et al. Protecting half the planet and transforming human systems are complementary goals. Frontiers Conserv. Science 2, 761292 (2021).

Wood, E. M. et al. Housing development erodes avian community structure in U.S. Protected areas. Ecol. Appl. 24, 1445–1462 (2014).

Michel, N. L., Saunders, S. P., Meehan, T. D. & Wilsey, C. B. Effects of Stewardship on Protected Area Effectiveness for Coastal Birds (Conservation Biology n/a, 2021).

Wauchope, H. S. et al. Protected areas have a mixed impact on waterbirds, but management helps. Nature 1–5 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04617-0 (2022).

Schuurman, G. et al. Resist-Accept-Direct (RAD)—a Framework for the 21st-Century Natural Resource Manager. https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2283597 (2020). https://doi.org/10.36967/nrr-2283597

Wu, J. X., Wilsey, C. B., Taylor, L. & Schuurman, G. W. Projected avifaunal responses to climate change across the U.S. National park system. PLoS ONE. 13, e0190557 (2018).

Wu, J. X. et al. U.S. National wildlife refuge system likely to see regional and seasonal species turnover in bird assemblages under a 2°C warming scenario. Ornithological Appl. 124, duac016 (2022).

Brockington, D. et al. Working governance for working land. Science 362, 1257–1257 (2018).

Fraser, E. D. G., Dougill, A. J., Mabee, W. E., Reed, M. & McAlpine, P. Bottom up and top down: analysis of participatory processes for sustainability indicator identification as a pathway to community empowerment and sustainable environmental management. J. Environ. Manage. 78, 114–127 (2006).

Michel, N. L. et al. Metrics for conservation success: using the Bird-Friendliness index to evaluate grassland and aridland bird community resilience across the Northern great plains ecosystem. Divers. Distrib. 26, 1687–1702 (2020).

Farrell, J. et al. Effects of land dispossession and forced migration on Indigenous peoples in North America. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abe4943 (2021).

West, P., Igoe, J. & Brockington, D. Parks and peoples: the social impact of protected areas. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 35, 251–277 (2006).

Garnett, S. T. et al. A Spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation. Nat. Sustain. 1, 369–374 (2018).

Schuster, R., Germain, R. R., Bennett, J. R., Reo, N. J. & Arcese, P. Vertebrate biodiversity on indigenous-managed lands in australia, brazil, and Canada equals that in protected areas. Environ. Sci. Policy. 101, 1–6 (2019).

Anguelovski, I. et al. Green gentrification in European and North American cities. Nat. Commun. 13, 3816 (2022).

Anguelovski, I. et al. Why green climate gentrification threatens poor and vulnerable populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 26139–26143 (2019).

Shokry, G., Connolly, J. J. & Anguelovski, I. Understanding climate gentrification and shifting landscapes of protection and vulnerability in green resilient Philadelphia. Urban Clim. 31, 100539 (2020).

Rigolon, A. & Németh, J. Green gentrification or ‘just green enough’: do park location, size and function affect whether a place gentrifies or not? Urban Stud. 57, 402–420 (2020).

Belote, R. T. et al. Options for prioritizing sites for biodiversity conservation with implications for 30 by 30. Biol. Conserv. 264, 109378 (2021).

Carroll, C. et al. Scale-dependent complementarity of Climatic velocity and environmental diversity for identifying priority areas for conservation under climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 4508–4520 (2017).

Karimi, A., Tulloch, A. I. T., Brown, G. & Hockings, M. Understanding the effects of different social data on selecting priority conservation areas: social opportunities and constraints. Conserv. Biol. 31, 1439–1449 (2017).

Taylor, L. et al. Choice of prioritization method impacts recommendations for climate-informed bird conservation in the United States. Ecography 12, e06401 (2022).

Whitehead, A. L. et al. Integrating biological and social values when prioritizing places for biodiversity conservation: conservation planning with social data. Conserv. Biol. 28, 992–1003 (2014).

Bryan, B. A., Grandgirard, A. & Ward, J. R. Quantifying and exploring strategic regional priorities for managing natural capital and ecosystem services given multiple stakeholder perspectives. Ecosystems 13, 539–555 (2010).

Fedele, G., Donatti, C. I., Bornacelly, I. & Hole, D. G. Nature-dependent people: mapping human direct use of nature for basic needs across the tropics. Glob. Environ. Change. 71, 102368 (2021).

Redpath, S. M. et al. Understanding and managing conservation conflicts. Trends Ecol. Evol. 28, 100–109 (2013).

Dorji, S. et al. Identifying conservation priorities for threatened Eastern Himalayan mammals. Conserv. Biol. 32, 1162–1173 (2018).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021).

Moilanen, A. Landscape zonation, benefit functions and target-based planning: unifying reserve selection strategies. Biol. Conserv. 134, 571–579 (2007).

Rehfeldt, G. E., Crookston, N. L., Sáenz-Romero, C. & Campbell, E. M. North American vegetation model for land-use planning in a changing climate: a solution to large classification problems. Ecol. Appl. 22, 119–141 (2012).

Sohl, T. L. The relative impacts of climate and Land-Use change on conterminous united States bird species from 2001 to 2075. PLoS ONE. 9, e112251 (2014).

Sohl, T. et al. Modeled historical land use and land cover for the conterminous united States. J. Land. Use Sci. 11, 476–499 (2016).

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Updates to the Demographic and Spatial Allocation Models to Produce Integrated Climate and Land Use Scenarios (ICLUS). (2017). https://iclus.epa.gov/

NOAA Office for Coastal Management. Sea Level Rise Wetland Impacts and Migration. (2019).

Alaska Center for Conservation Science. Alaska Vegetation and Wetland Composite. (2020).

U.S. Fish and wildlife service.National Wetlands Inventory website. U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C. (2020).

Theobald, D. M. et al. Earth transformed: detailed mapping of global human modification from 1990 to 2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 12, 1953–1972 (2020).

Grantham, H. S. et al. Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity. Nat. Commun. 11, 5978 (2020).

Rayfield, B., Moilanen, A. & Fortin, M. J. Incorporating consumer–resource Spatial interactions in reserve design. Ecol. Model. 220, 725–733 (2009).

Carroll, C., Dunk, J. R. & Moilanen, A. Optimizing resiliency of reserve networks to climate change: multispecies conservation planning in the Pacific northwest, USA. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 891–904 (2010).

Moilanen, A. et al. Zonation Spatial Conservation Planning Framework and Software v. 4.0, User manual. (2014).

Knutti, R. & Sedláček, J. Robustness and uncertainties in the new CMIP5 climate model projections. Nat. Clim. Change. 3, 369–373 (2013).

Bird Studies Canada and NABCI. Bird Conservation Regions. Published by Bird Studies Canada on behalf of the North American Bird Conservation Initiative. Bird Conservation Regions (2014). https://www.birdscanada.org/bird-science/nabci-bird-conservation-regions/

Veloz, S. et al. Improving effectiveness of systematic conservation planning with density data: improving systematic conservation planning. Conserv. Biol. 29, 1217–1227 (2015).

Jalkanen, J., Toivonen, T. & Moilanen, A. Identification of ecological networks for land-use planning with Spatial conservation prioritization. Landsc. Ecol. 35, 353–371 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Critical land change information enhances the Understanding of carbon balance in the united States. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 3920–3929 (2020).

Genet, H. et al. Decadal Averages of Ecosystem Carbon Balance, Snow Cover and Soil Moisture by Landscape Conservation Cooperative Regions for Alaska and Northwestern Canada. (2015).

Morán-Ordóñez, A. et al. Analysis of Trade-Offs between biodiversity, carbon farming and agricultural development in Northern Australia reveals the benefits of strategic planning. Conserv. Lett. 10, 94–104 (2017).

Reside, A., Vanderwal, J. & Moran, C. Trade-offs in carbon storage and biodiversity conservation under climate change reveal risk to endemic species. Biol. Conserv. 207, 9–16 (2017).

Naudts, K. et al. Europe’s forest management did not mitigate climate warming. Science 351, 597–600 (2016).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & for, A. T. S. and D. R. R., Analysis, and Services Program. CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index 2018 US Database. (2018).

U.S. Council on Environmental Quality. Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool Technical Support Document Version 1.0. (2022). https://www.whitehouse.gov/ceq/news-updates/2022/02/18/ceq-publishes-draft-climate-and-economic-justice-screening-tool-key-component-in-the-implementation-of-president-bidens-justice40-initiative/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PLACES: Local Data for Better Health. (2021). https://www.cdc.gov/places/index.html

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). EJSCREEN Technical Documentation. (2019). https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2021-04/documents/ejscreen_technical_document.pdf

James, P., Banay, R. F., Hart, J. E. & Laden, F. A review of the health benefits of greenness. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2, 131–142 (2015).

Zuzak, C. et al. National Risk Index Technical Documentation. (2021).

Geological Survey, U. S. Protected areas database of the united States (PAD-US) 2.1. U S Geol. Surv. https://doi.org/10.5066/P92QM3NT (2020).

McKinnon, M. C. et al. What are the effects of nature conservation on human well-being? A systematic map of empirical evidence from developing countries. Environ. Evid. 5, 8 (2016).

Burnette, C., Clark, C. & Rodning, C. Living off the land: how subsistence promotes Well-Being and resilience among Indigenous peoples of the southeastern united States. Soc. Serv. Rev. 92, 369–400 (2018).

U.S. Census Bureau. The American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian (AIANNH) Areas Shapefile. (2019). https://catalog.data.gov/dataset/tiger-line-shapefile-2019-nation-u-s-current-american-indian-alaska-native-native-hawaiian-area

Census Bureau, U. S. 2016–2020 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates Data Profiles, DP03 Selected Economic Characteristics. (2020). https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?d=ACS%205-Year%20Estimates%20Data%20Profiles&tid=ACSDP5Y2020.DP03

U.S. Census Bureau. Urban and Rural Classification and Urban Area Criteria. (2010). https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=069b5cafe3e34a2585e24ba63cd12b9e

Office of Policy Development and Research (PD&R) Department of Housing & Urban Development (HUD). 2014–2018 Comprehensive Housing Affordability Strategy (CHAS) Data. (2021). https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/cp.html

USGS Gap Analysis Project. Protected Areas Database of the United States (PAD-US). (2018). https://doi.org/10.5066/P955KPLE

USGCRP. Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume I [Wuebbles, D.J., D.W. Fahey, K.A. Hibbard, D.J. Dokken, B.C. Stewart, and T.K. Maycock (Eds.)]. 470 (2017). https://science2017.globalchange.gov/

Acknowledgments

We thank Geoff LeBaron and all Audubon staff who reviewed bird species lists. We thank Pedro Hernandez, Gabriel Watson, and Robert Harris for reviewing and providing comments on the manuscript. We thank Benjamin M Sleeter, Western Geographic Science Center, USGS, for contributions to and support of the carbon science components. We thank the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation for funding to support this work (G-1511-150388).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BB, MF, LT, JG, JW, SS, and CBW conceived the idea and BB, MF, LT, JG, JW, and SS designed the methodology. MF, LT, JW, SR collected and analysed the data. MF, SS, SR developed data visualization. BB and MF led the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bateman, B.L., Feng, ML.E., Grand, J. et al. A nature-based conservation framework that aligns opportunities for bird biodiversity, climate mitigation, and human equity. Sci Rep 15, 32096 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16693-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16693-z