Abstract

This cross-sectional study investigated the No-Apnea tool’s diagnostic ability to detect obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), across different severities (respiratory disturbance index [RDI] ≥ 5, ≥ 15, ≥ 30) compared to polysomnography (gold standard) in 2,087 consecutive patients attending a sleep clinic (age: 45.92 ± 13.46, male: 70.8%). We further compared the diagnostic performance of No-Apnea, NoSAS, and STOP-Bang tools. Across all RDI levels, No-Apnea showed superior sensitivity (96.9–99.0%, based on RDI thresholds), negative predictive value (NPV) (47.8–91.2%), negative likelihood ratio (0.10–0.22), and odds ratio (10.6–11.8). Across all RDI levels, NoSAS demonstrated the highest specificity (72.2–87.8%), positive predictive value (PPV) (67.5–97.4%), and positive likelihood ratio (2.21–3.87). No-Apnea achieved the highest accuracy and F1 scores at RDI ≥ 5 (90.37 and 94.8%) and ≥ 15 (74.75 and 84.8%). At RDI ≥ 5, NoSAS and STOP-Bang showed comparable areas under the ROC curve (AUC) (0.675 vs. 0.685, P > 0.05), exhibiting a significant advantage over No-Apnea (0.622, P = 0.004 and 0.002, respectively). At RDI ≥ 15 and ≥ 30, NoSAS had the highest (0.676 and 0.668), and No-Apnea had the lowest AUCs (0.566 and 0.543). STOP-Bang performance measures fell between No-Apnea and NoSAS across RDI levels. In our sleep clinic population, No-Apnea demonstrated high sensitivity, NPV, accuracy, and F1 score for detecting OSA, but low specificity, PPV, and AUC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), affecting 17% of women and 34% of men1. It is characterized by recurrent episodes of total or partial cessation of breathing during sleep, caused by an imbalance between anatomically imposed mechanical loads and compensatory neuromuscular responses2,3,4. Early diagnosis of OSA is of immense importance for several reasons; First, it is estimated that nearly 936 and 425 million adults worldwide experience mild to severe and moderate to severe OSA, respectively5. Second, untreated OSA can have serious health consequences and is usually accompanied by other comorbidities, including cardiovascular, respiratory, metabolic, and other sleep disorders6,7,8.

Polysomnography (PSG) is the gold standard method for OSA diagnosis, which is often provided in an attended setting (i.e., sleep laboratory)1,9,10. However, PSG is expensive and mostly unavailable in underserved countries9,10. Therefore, several screening tools have been developed, including the “Neck, Obesity, Snoring, Age, Sex” (NoSAS), “Snoring, Tiredness, Observed apnea, Blood Pressure” (STOP), “Snoring, Tiredness, Observed apnea, Blood Pressure, Body mass index (BMI), Age, Neck circumference, and Gender” (STOP-Bang), “Epworth sleepiness scale” (ESS), “Berlin questionnaire” (BQ), and the “No-Apnea” scale1,11. The optimal screening tool across diverse clinical settings and populations remains under debate due to conflicting research findings and variations in tool effectiveness across demographics. This includes the general population, medical populations, surgical patients, sleep clinics, commercial drivers, and even populations in different geographic regions12,13,14,15.

A high sensitivity and acceptable specificity are fundamental necessities for a screening tool16. Additionally, an ideal screening tool should be brief, simple to use, and devoid of time-consuming calculations or examination procedures16. Notably, many of the OSA screening tools mostly rely on subjective parameters17. However, objective-based scales are crucial for populations where self-reported data may be unreliable or unavailable. This includes individuals in occupational settings, those unable to report issues to healthcare providers (e.g., people with dementia or developmental disabilities), and those who sleep alone where subjective sleep information from a partner is unavailable. The No-Apnea is a recently developed and validated screening tool, consisting of merely two objective items, including the neck circumference (NC) and age. This simple objective approach holds particular value for populations such as commercial drivers17. Studies suggest almost similar performance of the “No-Apnea” compared to the “STOP-Bang” and “NoSAS” scales, despite its simplicity18.

Although the performance of other screening tools has been widely discussed in the literature, the screening performance of “No-apnea” requires further research17,18,19,20,21. Moreover, differences in anthropometric characteristics (i.e., NC) among specific populations necessitate further validation of this tool17,22. In this study, we evaluated the diagnostic performance of the No-Apnea, NoSAS, and STOP-Bang tools, compared to the gold standard of PSG, in detecting OSA with different severities among the Iranian sleep clinic population. Various diagnostic accuracy measures, including accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, F1 scores, likelihood ratios, area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC), and odds ratio (OR), were employed. Our primary focus was to assess the clinical utility of the No-Apnea screening tool, as it offers several potential advantages. It utilizes objective criteria, making it less susceptible to participant bias compared to questionnaires relying on self-reported symptoms. Additionally, its simplicity and ease of administration minimize the time spent on screening.

Materials and methods

Study setting and ethics statement

This cross-sectional clinic-based study of diagnostic accuracy was conducted at Baharloo Sleep Clinic, affiliated with the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, and approved by the University Institutional Review Board (IR.TUMS.IKHC.REC.1398.158). Electronic medical records of consecutive adult outpatients who were referred to the sleep clinic between March 1, 2017, and March 1, 2019, and underwent full overnight PSG were retrospectively analyzed. Data collection occurred after the completion of both the index tests (No-Apnea, STOP-Bang, and NoSAS) and the reference standard (PSG). Blinding procedures ensured that those performing the index tests were unaware of PSG results. Likewise, assessors interpreting PSGs were blind to index test findings. Sleep specialists, blinded to the research question, evaluated all sleep-related data. According to the Declaration of Helsinki, patients’ anonymity and confidentiality were protected, and written informed consent was obtained for participation and publication23. This diagnostic accuracy study is reported according to the “Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy Studies” (STARD) guideline (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2)24.

Study population

From a dataset comprising electronic health records, consecutive adult patients (≥ 18 years) who attended the sleep clinic during the study period and underwent a full overnight PSG were eligible for inclusion. Individuals with incomplete data entry, technically inadequate PSG recordings, those who were not surveyed for all three index tests, and those who did not provide informed consent were excluded.

Study objectives

The objective of this study was to identify and compare the diagnostic performance, including predictive performance and discriminative ability, of three index screening tests (the No-Apnea, STOP-Bang, and NoSAS) against RDI (the reference test, which is derived from PSG24) in a sleep clinic population. Our main research question was to determine whether the No-Apnea instrument possesses adequate diagnostic value for OSA detection, thus serving as a convenient, practical, and time-saving screening alternative in clinical settings.

Study measures and test methods

The following information was collected: (a) baseline demographic and clinical characteristics (age, sex, BMI, NC, and ESS questionnaire results), (b) screening tool results (No-Apnea, STOP-Bang, and NoSAS), and (c) in-lab full-night PSG results (total sleep time, sleep efficiency, sleep latency, rapid eye movement [REM] latency, percentages of all stages of sleep, O2 saturation (awake, mean, and minimum), and respiratory disturbance index [RDI]).

Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) is an eight-item questionnaire, ranging from 0 to 24, that subjectively evaluates daytime sleepiness25. Sleepiness is defined as a total score of ≥ 1025 (Supplementary Table S3).

Polysomnography (PSG) is the gold-standard approach for OSA diagnosis1. Several sleep and respiratory parameters, including RDI, are obtained from PSG during overnight sleep1,9.

Respiratory Disturbance Index (RDI) is the number of apneas, hypopneas, and respiratory-effort-related arousals (RERAs) per hour of sleep, measured during PSG9. RDI thresholds are categorized as RDI ≥ 5 (OSA of any severity), RDI ≥ 15 (moderate to severe OSA), and RDI ≥ 30 (severe OSA)26.

No-Apnea is a 2-item model developed and validated by Duarte et al. in 201817, with a total score ranging from zero to nine17,18. A maximum of six points is allocated for NC (cm): zero points for NC < 37, one point for 37 ≤ NC < 40, three points for 40 ≤ NC < 43, and six points for NC ≥ 43. A maximum of three points is allocated for age: zero points for age < 35, one point for 35 ≤ age < 45, two points for 45 ≤ age < 55, and three points for age ≥ 5517 (Supplementary Table S4). A total No-Apnea score ≥ 3 is graded as high risk for OSA17. To measure the NC, each subject was instructed to stand up straight with their head in the Frankfort horizontal plane. Subsequently, the superior border of a tape measure was attached perpendicularly to the long axis of the neck, just below the laryngeal prominence27.

STOP-Bang is an eight-item dichotomous questionnaire, originally developed for preoperative screening1. The evaluated parameters include snoring, tiredness, observed apnea, blood pressure, BMI, age, NC, and sex28 (Supplementary Table S5). Answering “yes” to at least three and five questions suggests an intermediate and a high risk of OSA, respectively29. A score of ≥ 3, which is also used as the STOP-Bang cutoff in our study, has shown a high sensitivity and diagnostic accuracy in detecting moderate to severe OSA14,29.

NoSAS is a five-item tool comprised of age, sex, snoring, BMI, and NC30. The NoSAS screening tool has demonstrated a high discriminative power for patients with OSA30. In the scoring system comprising 17 points, 4 points are allocated for a NC > 40 cm, 3 and 5 points for 25 ≤ BMI < 30, and BMI ≥ 30, respectively. The presence of snoring corresponds to 2 points, an age > 55 years results in 4 points, and being male contributes an additional 2 points30 (Supplementary Table S6). A score ≥ 8 is considered high risk for OSA30.

Screening performance measures

We evaluated standard screening performance metrics, including sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, F1 score, positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV), positive and negative likelihood ratios (PLR and NLR), and the area under the ROC curve (AUC). While accuracy and predictive values are affected by disease prevalence, sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratios, and AUC remain independent of it31,32,33,34. Definitions and detailed explanations of each metric are provided in Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S7.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 22.0, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) and R (version 4.4.0). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and quantile–quantile plot (Q–Q plot) were used to assess the distribution of numeric data. Descriptive statistics were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed numeric variables, median with interquartile range [Q1, Q3] for non-normally distributed numeric variables, and frequency (percentage) for categorical variables. To evaluate the predictive performance of the model, we employed logistic regression to estimate the OR and Area Under the Curve (AUC) for each model. The AUC and ROC curves were used to assess the model’s discriminatory ability, and 2 × 2 contingency tables were used to determine sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, PLR, NLR, and F1 scores. 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported for all estimates. DeLong’s test was used to compare the AUCs of the index tests35. A two-tailed P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic, clinical, and polysomnographic characteristics of participants

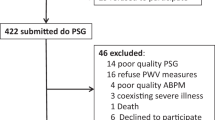

Of 2,505 adults who attended the sleep clinic and underwent PSG during the study period, 418 were excluded for the following reasons: incomplete data entry (n = 153), technically inadequate PSG (n = 78), not surveyed for all three index tests (n = 61), and lack of informed consent for the study (n = 126) (Fig. 1). Eventually, 2,087 participants (age: 45.92 ± 13.46, male: 70.8%) were included, of whom 90.6% (n = 1891), 71.7% (n = 1497), and 48.4% (n = 1011) were diagnosed with OSA of any severity (RDI ≥ 5), moderate to severe OSA (RDI ≥ 15), and severe OSA (RDI ≥ 30), respectively.

STARD diagram to report the flow of participants through the study. Dx, diagnosis; NoSAS, neck, obesity, snoring, age, sex; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PSG, polysomnography; STARD, standards for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies; STOP-Bang, snoring, tiredness, observed apnea, blood pressure, body mass index, age, neck circumference, and gender; neg, negative; pos, positive. The STARD diagram is available at: STARD-2015-flow-diagram.pdf (equator-network.org).

Table 1 summarizes the demographic, anthropometric, clinical, and polysomnographic characteristics of participants. The average BMI and NC were 29.73 kg/m2 and 40.37 cm, respectively. Excessive daytime sleepiness (ESS ≥ 10) was found in 41.3% of participants. A total of 94.6% (n = 1974), 80.0% (n = 1670), and 44.0% (n = 919) of participants tested positive on the No-Apnea, STOP-Bang, and NoSAS tools, respectively.

Correct classification, unnecessary sleep recordings, and missed diagnosis of index tests

The results of the performance analysis are summarized in the contingency Table 2. Considering the threshold of RDI ≥ 5 (90.6%, n = 1891), the No-Apnea, STOP-Bang, and NoSAS screening test results were positive in 96.9% (n = 1832), 83.5% (n = 1579), and 47.3% (n = 895) of patients, respectively. The corresponding values for RDI ≥ 15 (71.7%, n = 1497) were 98.3% (n = 1472), 87.5% (n = 1310), and 54.0% (n = 808), and for RDI ≥ 30 (48.4%, n = 1011) were 99.0% (n = 1001), 91.1% (n = 921), and 61.3% (n = 620), respectively. These percentages reflect the tests’ sensitivity.

For individuals with an RDI threshold of ≥ 5, the No-Apnea test demonstrated a correct classification rate (accuracy) of 90.37% (n = 1886), with 6.80% unnecessary sleep recordings (false positive results) and 2.83% missed diagnoses (false negative results). The STOP-Bang test achieved a correct classification rate of 80.69% (n = 1684), accompanied by 4.36% false positive results and 14.95% missed diagnoses. The NoSAS test exhibited a correct classification rate of 51.12% (n = 1067), with 47.72% missed diagnoses and 1.15% unnecessary sleep recordings.

Regarding individuals with RDI ≥ 15, the No-Apnea test yielded a correct classification rate of 74.75% (n = 1560), 24.05% unnecessary sleep recordings, and 1.20% missed diagnoses. For the STOP-Bang test, a correct classification rate of 73.79% (n = 1540) was observed, along with 17.25% false positive results and 8.96% missed diagnoses. The NoSAS test achieved a correct classification rate of 61.67% (n = 1287), with 5.32% unnecessary sleep recordings and 33.01% missed diagnoses.

When considering individuals with RDI ≥ 30, the No-Apnea test attained a correct classification rate of 52.90% (n = 1104), with 46.62% unnecessary sleep recordings and 0.48% missed diagnoses. The STOP-Bang test displayed a correct classification rate of 59.80% (n = 1248), along with 35.89% false positive results and 4.31% missed diagnoses. The NoSAS test demonstrated a correct classification rate of 66.94% (n = 1397), accompanied by 14.33% unnecessary sleep recordings and 18.74% missed diagnoses.

Performance measures of screening tools according to RDI thresholds

Table 3 summarizes the performance of index tests across various RDI thresholds. Figure 2 provides a visual representation of these measures, allowing for easy comparison of the performance of different tools. Across all RDI thresholds, the No-Apnea showed the highest sensitivity (RDI ≥ 5: 96.9% [95% CI: 96.0, 97.6]; RDI ≥ 15: 98.3% [97.5, 98.9]; and RDI ≥ 30: 99.0% [98.2, 99.5]), NPV (RDI ≥ 5: 47.8% [38.3, 57.4]; RDI ≥ 15: 77.9% [69.1, 85.1]; and RDI ≥ 30: 91.2% [84.3, 95.7]), and the lowest NLR (RDI ≥ 5: 0.22 [0.12, 0.35]; RDI ≥ 15: 0.11 [0.07, 0.17]; and RDI ≥ 30: 0.10 [0.05, 0.19]). Furthermore, the No-Apnea had the highest OR (RDI ≥ 5: 11.80 [7.88, 17.70]; RDI ≥ 15: 10.30 [6.57, 16.20], and RDI ≥ 30: 10.60 [5.56, 20.20]) across all RDI thresholds, and the highest accuracy and F1 score for RDI ≥ 5 (90.37% and 94.8%, respectively) and RDI ≥ 15 (74.75% and 84.8%, respectively).

Performance measures of the No-Apnea, NoSAS, and STOP-Bang tools for diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea at RDI ≥ 5, RDI ≥ 15, and RDI ≥ 30. NoSAS, neck, obesity, snoring, age, sex; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; STOP-Bang, snoring, tiredness, observed apnea, blood pressure, body mass index, age, neck circumference, and gender.

Conversely, the NoSAS displayed superior specificity (RDI ≥ 5: 87.8% [82.3, 92.0]; RDI ≥ 15: 81.2% [77.8, 84.3]; and RDI ≥ 30: 72.2% [69.4, 74.9]), PPV (RDI ≥ 5: 97.4% [96.1, 98.3]; RDI ≥ 15: 87.9% [85.6, 90.0]; and RDI ≥ 30: 67.5% [64.3, 70.5]), and PLR (RDI ≥ 5: 3.87 [2.65, 5.64]; RDI ≥ 15: 2.87 [2.41, 3.41]; and RDI ≥ 30: 2.21 [1.98, 2.46]), across all RDI thresholds. NoSAS exhibited the highest accuracy for RDI ≥ 30 (66.94%). STOP-Bang exhibited intermediary values between the No-Apnea and NoSAS across most measures.

Figure 3 illustrates the AUCs of the index tests at different RDI thresholds. At RDI ≥ 5, No-Apnea displayed a significantly lower AUC (0.622 [95% CI: 0.59, 0.65]), compared to the STOP-Bang (0.685 [0.64, 0.72]) and NoSAS (0.675 [0.65, 0.70]) (P = 0.002 and 0.004, respectively). There was no significant difference between STOP-Bang and NoSAS at RDI ≥ 5 (P = 0.661). For RDI ≥ 15, NoSAS outperformed STOP-Bang (0.676 [0.65, 0.69] vs. 0.632 [0.61, 0.65], P = 0.001) and No-Apnea (0.676 [0.65, 0.69] vs. 0.567 [0.55, 0.58], P < 0.001), and STOP-Bang outperformed No-Apnea (P < 0.001). Similar trends were observed at RDI ≥ 30 (NoSAS vs. STOP-Bang: 0.668 [0.64, 0.68] vs. 0.607 [0.59, 0.62], P < 0.001; NoSAS vs. No-Apnea: 0.668 [0.64, 0.68] vs. 0.543 [0.53, 0.55], P < 0.001; and STOP-Bang vs. No-apnea: 0.607 [0.59, 0.62] vs. 0.543 [0.53, 0.55], P < 0.001).

Receiver operating characteristic curves comparing the discriminative ability of the No-Apnea, NoSAS, and STOP-Bang tools for diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea at RDI ≥ 5, RDI ≥ 15, and RDI ≥ 30. NoSAS, neck, obesity, snoring, age, sex; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; STOP-Bang, snoring, tiredness, observed apnea, blood pressure, body mass index, age, neck circumference, and gender.

Discussion

Main findings

We compared the performance of the No-Apnea screening tool with two well-known questionnaires (NoSAS and STOP-Bang). Among the sleep clinic population of 2,087 individuals, 90.6%, 71.7%, and 48.4% had RDI ≥ 5, ≥ 15, and ≥ 30, respectively. Across all RDI thresholds, No-Apnea exhibited the most favorable performance in terms of minimizing false negatives (0.48–2.83%) and mitigating cases of missed diagnosis. However, as with expectation16,30, this was obtained at the cost of the highest proportion of false positives (6.80–46.62%), resulting in unnecessary sleep recordings. NoSAS demonstrated contrasting outcomes, displaying the highest rate of missed diagnoses (18.74–47.72%) alongside the lowest proportion of unnecessary sleep recordings (1.15–14.33%). STOP-Bang demonstrated intermediate values between the No-Apnea and NoSAS, offering a balanced trade-off between false negatives and false positives. In the same way, while the No-apnea showed the best sensitivity (96.9–99.0%, varying based on RDI thresholds), NPV (47.8–91.2%), and NLR (0.10–0.22), NoSAS exhibited the lowest values in these measures, counterbalanced by the highest values in specificity (72.2–87.8%), PPV (67.5–97.4%), and PLR (2.21–3.87), across all RDI thresholds. The highest accuracy at RDI ≥ 5 and ≥ 15 was achieved by No-Apnea (90.37 and 74.75%, respectively). Similarly, the No-Apnea had the highest F1 scores at RDI ≥ 5 and ≥ 15 (94.8 and 84.8%, respectively). For a sleep clinic’s screening measures, the F1 score is a highly valuable metric because it provides a single, comprehensive assessment of how well the tool balances the critical trade-off between identifying true cases and minimizing unnecessary referrals36. The No-Apnea also showed the highest OR at all RDI levels (10.6–11.8). Concerning the AUCs, at RDI ≥ 5, NoSAS and STOP-Bang demonstrated comparable performance (0.675 vs. 0.685), exhibiting a significant advantage over No-Apnea (0.622). At RDI ≥ 15 and ≥ 30, the highest AUC values were attributed to NoSAS (0.676 and 0.668, respectively), and the lowest were attributed to No-Apnea (0.566 and 0.543, respectively). STOP-Bang displayed intermediate values across most of the performance metrics. Overall, the No-Apnea score can be used as an easy-to-use, practical, and time-saving screening alternative in a sleep clinic population, mostly when minimizing missed diagnoses is the primary concern. This tool was able to effectively “rule out” OSA. Additionally, it offers the advantages associated with objective tools, such as suitability for large groups (including occupational settings37), applicability to individuals with dementia or developmental disabilities, and mitigating participant bias.

Understanding the clinical value of different screening tools

Selecting appropriate screening tools and interpreting their clinical value depends on understanding the overall health context38. Tests with high sensitivity, NPV, and NLR effectively rule out individuals who don’t have the condition and minimize missed diagnoses39. Conversely, tests with high specificity, PPV, and PLR accurately identify those who truly have the condition, reducing unnecessary interventions31,39. Several factors influence this choice, including disease prevalence, screening program goals, the seriousness of the condition being screened for, available medical resources, and the consequences of both false negatives (missed or delayed diagnoses, delayed or inappropriate treatment, patient’s anxiety, and legal issues) and false positives (unnecessary interventions, overtreatment, patient’s anxiety, cost burden, wasted resources, patient’s mistrust, stigmatization, and legal issues)31,38.

A key concern when evaluating screening test performance in referral settings (e.g., sleep clinics) is that the high pre-test probability can inflate the estimated sensitivity of screening tools. This phenomenon, known as spectrum bias40, occurs because clinic populations often present with more severe or classic disease manifestations, which are inherently easier to detect. Despite this, our study found that No-Apnea consistently demonstrated higher sensitivity compared to STOP-Bang and NoSAS, even under these conditions. Therefore, No-Apnea’s high estimated sensitivity likely stems from both its inherent design and the characteristics of a sleep clinic population, which typically includes older individuals and those with larger NCs. It’s important to note that most prior studies evaluating OSA screening tools have similarly investigated these tools in individuals already suspected of having SDB17,18,19,21,22,41,42,43,44. Future studies should evaluate No-Apnea in patients at an earlier stage, before their referral to a sleep clinic. Of note, we recently conducted a separate study evaluating the No-Apnea and STOP-Bang questionnaires in a pre-referral cohort of 581 commercial drivers, a population with significant occupational safety considerations37. In this cohort, the No-Apnea identified 65.7% of drivers as high risk for OSA, whereas the STOP-Bang identified 17.7%. Notably, 48.6% of drivers were flagged as high-risk by No-Apnea but not by STOP-Bang, and the agreement between the two tools was low37. Although definitive conclusions cannot be drawn in the absence of confirmatory PSG data, the marked differences in performance between No-Apnea and STOP-Bang in this pre-referral population further underscore the need for future studies to evaluate the utility of OSA screening tools in earlier-stage populations.

Prior research on different OSA screening tools

Supplemental Table S8 summarizes some recent studies comparing different OSA screening tools. Our results concerning most performance measures (i.e., sensitivity, specificity, accuracy) align with a previous large cross-sectional study (n = 4,072) on outpatients suspected of SDB, where the same screening tools were employed17. However, unlike their findings of similar discriminative ability (AUC) between No-Apnea with STOP-Bang and NoSAS17, our study revealed lower No-Apnea AUCs compared to NoSAS and STOP-Bang across all RDI thresholds. A year later (2019), to further validate the No-Apnea in morbidly obese patients, a total of 1,017 patients were evaluated in two independent groups, including the bariatric surgery and the non-bariatric surgery cohorts18. Accordingly, No-Apnea had non-inferior discriminative ability (AUC) to STOP-Bang and NoSAS in detecting 5 ≤ apnea–hypopnea index (AHI) < 15, 15 ≤ AHI < 30, and AHI ≥ 30, in both cohorts18. Similar findings were reported in other populations, including patients with self-reported insomnia21, individuals suspected of SDB (considering AHI ≥ 20)42, and a separate study of 214 patients undergoing bariatric surgery45. A year later, in 2020, the research team conducted a comparative study to evaluate the No-Apnea score in screening OSA by sex19. Among the 6,606 adults (53.8% men), No-Apnea reached a sensitivity of 83.9–93.0% and a specificity of 57.3–35.2%. Accordingly, No-Apnea reached higher sensitivity and lower specificity in men compared with women at all OSA severity levels. However, the discriminatory power of No-Apnea was similar between men and women19. Overall, the No-Apnea score exhibited strong discriminative power (AUC > 0.7) among individuals with OSA in both sexes19.

While the No-Apnea tool offers a simple approach to OSA screening, its limitations compared to more comprehensive tools should be considered. The No-Apnea score focuses solely on age and NC. In contrast, the NoSAS screening tool incorporates assessments of sex, snoring, and BMI alongside age and NC30. Furthermore, STOP-Bang evaluates patients using more related parameters, including self-reported (snoring, tiredness, observed apnea, blood pressure) and demographic items (BMI, age, NC, and gender), which may result in a more precise assessment28. In this regard, some studies have reported contradictory findings11,42,43 to the previously discussed studies17,18,19,21. According to a study comparing No-Apnea with five other screening tools (NoSAS, ESS, STOP-Bang, and BQ) in 221 patients with cerebral infarction, NoSAS and No-Apnea showed the highest and lowest efficacy, respectively43. While the AUCs did not significantly differ at AHI ≥ 15 and ≥ 30, NoSAS showed a superior AUC compared to the others at AHI ≥ 543. In another study comparing six screening tools (BQ, ESS, No-Apnea, STOP-Bang, NoSAS, and STOP) in 398 hypertensive patients with suspected OSA, No-Apnea performed the lowest (AUC < 0.6) in all OSA severity groups11. The authors hypothesized that this poor performance probably arises from the simplicity of the tool, potentially leading to the oversight of crucial predictive factors, including hypertension11. The authors also reported that the sensitivity and NPV of No-Apnea were inferior to those exhibited by STOP-Bang in hypertensive patients11, which contradicts our findings in a sleep clinic population. Variations in study populations, including differences in age, sex, BMI, comorbidities, and sample size, can justify the differences in the performance of screening tests across different studies22. These observations necessitate the need for further validation of screening tools while considering the overall health context.

Limitations, strengths, and future directions

The results of the present study should be interpreted in light of its limitations. Participants were recruited from a sleep clinic, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings to the broader population with sleep issues. A primary concern in assessing screening test performance measures within referral settings is that the elevated pre-test probability of OSA commonly found in sleep clinics can lead to an overestimation of the screening tools’ sensitivity. Additionally, there were disproportionately more men than women in our sample (as expected with a sleep clinic population), which may limit the applicability of the findings to women. The single-center design of the current study necessitates future multicenter studies to confirm the results. Furthermore, due to the anthropometric differences among Iranian patients and other populations, such as the Hispanic population, future studies should be conducted to evaluate the No-Apnea tool in different populations. Notably, a potential inherent limitation of the No-Apnea score is that simply being over 55 years old assigns 3 points, which can already categorize someone as high-risk for OSA. This may limit its ability to differentiate risk levels within older populations44. Finally, classifying OSA severity solely based on RDI might not fully capture the clinical heterogeneity of the disease, as patients with similar RDI values can have different degrees of hypoxemia or other adverse health outcomes. Future research should aim to validate the performance of OSA screening tools against a more comprehensive set of PSG parameters (e.g., oxygen desaturation index, nadir SpO2, etc.).

Another interesting avenue for future research involves evaluating the diagnostic value of combining two screening tools, such as No-Apnea, STOP-Bang, and NoSAS. Applying logical rules (e.g., ‘either positive’ or ‘both positive’) to their results might enhance overall diagnostic performance by improving sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. This approach would also better reflect real-world clinical decision-making, where multiple pieces of information are considered simultaneously. Furthermore, assessing combined performance offers insights into potential complementary or synergistic effects, informing the development of two-step screening strategies, especially in resource-limited or high-risk settings. Such analyses would also reveal if specific combinations create synergistic effects or simply provide redundant information.

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this is the first study to assess differences in No-Apnea, STOP-Bang, and NoSAS screening performance among a Middle Eastern population.

Conclusions

Our study suggested the No-Apnea score has high performance in terms of sensitivity, NPV, NLR, accuracy, and F1 score for detecting OSA in a sleep clinic population. This indicates its ability to reliably rule out OSA and minimize missed diagnoses. However, the score also had low specificity, PPV, PLR, and AUC. This translates to a high number of false positives, particularly at higher RDI thresholds (≥ 15 and ≥ 30), leading to unnecessary sleep studies.

The No-Apnea tool seems an appropriate choice to detect OSA in a sleep clinic population, particularly when the consequence of a missed diagnosis is considerable or when subjective information is not reliable or available. Nevertheless, this tool might not be as appropriate in conditions where the disease prevalence is low.

Data availability

Data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request, without undue reservation. Contact information: najafeeaz@gmail.com.

References

Gottlieb, D. J. & Punjabi, N. M. Diagnosis and management of obstructive sleep apnea: A review. JAMA 323(14), 1389–1400 (2020).

Spicuzza, L., Caruso, D. & Di Maria, G. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome and its management. Ther. Adv. Chronic. Dis. 6(5), 273–285 (2015).

Patil, S. P. et al. Adult obstructive sleep apnea: Pathophysiology and diagnosis. Chest 132(1), 325–337 (2007).

Jordan, A. S., McSharry, D. G. & Malhotra, A. Adult obstructive sleep apnoea. Lancet 383(9918), 736–747 (2014).

Benjafield, A. V. et al. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: A literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 7(8), 687–698 (2019).

Bonsignore, M. R. et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and comorbidities: A dangerous liaison. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 14(1), 8 (2019).

Amirifard, H. et al. Sleep microstructure and clinical characteristics of patients with restless legs syndrome. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 18(11), 2653–2661 (2022).

Rahimi, N., Amirifard, H. & Jameie, M. An unusual presentation of severe obstructive sleep apnea with nocturnal seizure-like movements: A case report. Clin. Case Rep. 12(6), e9004 (2024).

Secretariat, M. A Polysomnography in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: An evidence-based analysis. Ont. Health Technol. Assess. Ser. 6(13), 1–38 (2006).

Abrishami, A., Khajehdehi, A. & Chung, F. A systematic review of screening questionnaires for obstructive sleep apnea. Can. J. Anaesth. 57(5), 423–438 (2010).

Zheng, Z. et al. Comparison of six assessment tools to screen for obstructive sleep apnea in patients with hypertension. Clin. Cardiol. 44(11), 1526–1534 (2021).

Patel, D. et al. Validation of the STOP questionnaire as a screening tool for OSA among different populations: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 18(5), 1441–1453 (2022).

Chen, L. et al. Validation of the STOP-Bang questionnaire for screening of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population and commercial drivers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 25(4), 1741–1751 (2021).

Pivetta, B. et al. Use and performance of the STOP-Bang questionnaire for obstructive sleep apnea screening across geographic regions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 4(3), e211009 (2021).

Jonas, D. E. et al. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea in adults: Evidence report and systematic review for the us preventive services task force. JAMA 317(4), 415–433 (2017).

Maxim, L. D., Niebo, R. & Utell, M. J. Screening tests: A review with examples. Inhal. Toxicol. 26(13), 811–828 (2014).

Duarte, R. L. M. et al. Simplifying the screening of obstructive sleep apnea with a 2-item model, no-apnea: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 14(7), 1097–1107 (2018).

Duarte, R. L. M. et al. Comparative performance of screening instruments for obstructive sleep apnea in morbidly obese patients referred to a sleep laboratory: A prospective cross-sectional study. Sleep Breath. 23(4), 1123–1132 (2019).

Duarte, R. L. M. et al. Using the No-Apnea score to screen for obstructive sleep apnea in adults referred to a sleep laboratory: Comparative study of the performance of the instrument by gender. J. Bras. Pneumol. 46(5), e20190297 (2020).

Najafi, A., et al. The clinical significance of the No-Apnea score: A comparison study of three tools for screening obstructive sleep apnea. J. Sleep Res. 2022. WILEY 111 RIVER ST, HOBOKEN 07030-5774, NJ USA.

Duarte, R. L. M. et al. Predicting obstructive sleep apnea in patients with insomnia: A comparative study with four screening instruments. Lung 197(4), 451–458 (2019).

Chiu, H.-Y. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the berlin questionnaire, STOP-BANG, STOP, and Epworth sleepiness scale in detecting obstructive sleep apnea: A bivariate meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 36, 57–70 (2017).

Association, W. M. World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310(20), 2191–2194 (2013).

Cohen, J. F. et al. STARD 2015 guidelines for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ Open 6(11), e012799 (2016).

Johns, M. W. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 14(6), 540–545 (1991).

Force, A.A.O.S.M.T. Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. The Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep 22(5), 667–689 (1999).

WHO, Measuring obesity: classification and description of anthropometric data. Geneva: World Health Organization, (1989).

Chung, F., Abdullah, H. R. & Liao, P. STOP-Bang questionnaire: A practical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 149(3), 631–638 (2016).

Kline, L.R., Collop, N., Finlay, G. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. Uptodate. com [Internet], 2017.

Marti-Soler, H. et al. The NoSAS score for screening of sleep-disordered breathing: a derivation and validation study. Lancet Respir Med 4(9), 742–748 (2016).

Shreffler, J., Huecker, M.R. Diagnostic testing accuracy: Sensitivity, specificity, predictive values and likelihood ratios. (2020).

Glas, A. S. et al. The diagnostic odds ratio: A single indicator of test performance. J Clin Epidemiol 56(11), 1129–1135 (2003).

Deeks, J. J. Systematic reviews of evaluations of diagnostic and screening tests. BMJ 323(7305), 157–162 (2001).

Hajian-Tilaki, K. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis for medical diagnostic test evaluation. Caspian. J. Intern. Med. 4(2), 627–635 (2013).

DeLong, E. R., DeLong, D. M. & Clarke-Pearson, D. L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach. Biometrics 44(3), 837–845 (1988).

Cabot, J. H. & Ross, E. G. Evaluating prediction model performance. Surgery 174(3), 723–726 (2023).

Pour Hoseini Anari, S. A. et al. The comparison of STOP-BANG and no-apnea questionnaires in screening obstructive sleep apnea among commercial drivers. Traffic Inj. Prev. 26(4), 416–421 (2025).

Iragorri, N. & Spackman, E. Assessing the value of screening tools: Reviewing the challenges and opportunities of cost-effectiveness analysis. Public Health Rev. 39(1), 17 (2018).

Power, M., Fell, G. & Wright, M. Principles for high-quality, high-value testing. BMJ Evid.-Based Med. 18(1), 5–10 (2013).

Murad, M. H. et al. The association of sensitivity and specificity with disease prevalence: Analysis of 6909 studies of diagnostic test accuracy. CMAJ 195(27), E925-e931 (2023).

Miller, J. N. et al. Comparisons of measures used to screen for obstructive sleep apnea in patients referred to a sleep clinic. Sleep Med. 51, 15–21 (2018).

Sweed, R. A. & Mahmoud, M. I. Validation of the NoSAS score for the screening of sleep-disordered breathing: A retrospective study in Egypt. Egyptian J. Bronchol. 13(5), 760–766 (2019).

Chen, R. et al. The No-apnea score vs. the other five questionnaires in screening for obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome in patients with cerebral infarction. J Thorac Dis 11(10), 4179–4187 (2019).

Duarte, R. L. et al. Obstructive sleep apnea screening with a 4-Item instrument, named goal questionnaire: development, validation and comparative study with no-apnea, STOP-bang, and NoSAS. Nat. Sci. Sleep 12, 57–67 (2020).

Kreitinger, K. Y. et al. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea in a diverse bariatric surgery population. Obesity (Silver Spring) 28(11), 2028–2034 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the patients, clinicians, and staff whose contributions to electronic medical records made this work possible. The abstract of this study was presented at the 26th Congress of the European Sleep Research Society (Sept 2022) [20].

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies

During the preparation of this work, the authors used Gemini (Gemini (google.com)) and ChatGPT to improve language and readability, with caution. After using these tools, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Funding

No specific funding was received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.J.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft; M.B.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing—original draft; S.A.: Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing—review & editing; M.A.: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft; H.A.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—review & editing; Kh.S.H.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—review & editing; M.E.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—review & editing; R.H.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—review & editing; B.R.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing; A.N.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no financial and non-financial interests relevant to this work.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (IR.TUMS.IKHC.REC.1398.158).

Informed consent

All individuals gave their written informed consent for participation and publishing, according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jameie, M., Bayat, M., Akbarpour, S. et al. The No-Apnea score for early obstructive sleep apnea detection in a sleep clinic: a study of diagnostic accuracy and comparative performance of three screening instruments. Sci Rep 15, 41729 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16694-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16694-y