Abstract

In magnetic-fusion devices, magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) disturbances such as edge-localized modes (ELMs) have interesting similarities to explosive dynamical events observed in space. Various models for the mechanisms triggering such disturbances have been proposed. However, current studies have focused on developing methods for controlling such effects based on empirical scaling. Although unanswered questions remain regarding ITER, diverse viewpoints beyond the current paradigm can provide a deeper understanding, even for widely accepted answers. Herein, we define the triggering time of an ELM using precise diagnostics to eliminate the uncertainty that can accompany the determination of causal relationships. This has enabled us to identify a precursor MHD with tearing parity (poloidal/toroidal mode numbers m/n = 4/1) as the cause of an ELM; it leads to the development of a macroscopic ELM when the magnetic perturbation exceeds a threshold of ~ 10 Gauss within \(\:\le\:\)100 \(\:\mu\:\)s, providing a consistent representation of this phenomenon that extends from the precursor to the collapse. The explosive growth timescale from the triggering time is consistent with a hyper-resistive model of magnetic braiding and stochasticity. This approach to solving the triggering problem provides valuable scientific insights into diverse magnetized-plasma-explosion physics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large-scale explosive phenomena in the Sun’s atmosphere (e.g., solar flares1,2,3,4,5,6) are well-known examples of abrupt phenomena that occur in highly magnetized plasmas on widely different scales (ranging from the Sun to stars, galaxies, and cluster of galaxies). When the charged plasma particles emitted by solar flares reach Earth and collide with the upper atmosphere in Earth’s polar regions, they emit light that we see as the aurora. This is a topic of interest to many readers. The large-scale electromagnetic noise from solar flares can also cause damage to sensitive electronic devices (e.g., producing global communications outages)7. It is therefore essential to predict such events accurately and prepare for them before they occur and result in serious incidents.

In addition, a huge international project (ITER8,9,10) is underway with the goal of achieving nuclear-fusion reactions on Earth similar to thos that make the Sun and stars shine, and projects have been proposed to demonstrate the controlled use of nuclear-fusion energy (i.e., DEMO11,12). Although research and development has been ongoing around the world for several decades, recent increased efforts by venture companies use innovative ideas aiming to achieve power-generation demonstrations quickly13.

Interestingly, abrupt magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) phenomena have been observed in experimental magnetic-confinement nuclear-fusion devices14 that exhibit similarities with magnetized-plasma-explosion events in space15. Although they do not necessarily share a unifying physics, various MHD phenomena, such as edge-localized modes (ELMs), have been distinguished phenomenologically16,17,18,19,20,21,22. However, the occurrence of such MHD phenomena cannot be fully predicted either in space or on the ground. The development of highly advanced fine-tuning control methods (e.g., ELM-control coils)23,24,25 is continuing for ITER, in which the self-heated/self-organized burning plasmas differ from those in previous systems.

Numerous models have been proposed to explain the mechanisms that trigger abrupt events in solar and laboratory plasmas. Currently, researchers across various fields are collaborating to uncover the fundamental physical processes underlying these phenomena. High-precision observations from laboratory experiments and fusion devices, and their careful interpretation, are expected to play a significant role in advancing our understanding of this complex issue. Here, we discuss a possible mechanism for triggering magnetized-plasma explosions. Although we analyze only one discharge from a single tokamak and provide evidence for a tearing trigger in this discharge, other mechanisms may well be involved in other discharges. While our focus is on ELMs in experimental fusion devices, this issue is also relevant to explosive phenomena in space. It can be defined as a sudden (short-term) increase in the growth rate of some phenomenon that occurs more rapidly than a typical timescale in the system26,27. In addressing this issue, it is essential to maintain a consistent perspective from the precursor up to the triggering time of a large-scale event. This perspective can help to prevent a big project from falling into the pitfall where a commonly accepted method for controlling a sudden explosive dynamical event does not work well in a burning plasma (which has not yet been achieved).

Results

The Japan Atomic Energy Research Institute Tokamak-60 Upgrade (JT-60U)28 is a single-null-divertor tokamak device with major and minor plasma radii of 3–3.5 m and 0.6–1.1 m, respectively. The maximum toroidal magnetic field, ≤ 4 T, occurs at a plasma radius of 3.32 m (using normal conducting coils for both the toroidal and poloidal coils). It is categorized as a large tokamak like the Joint European Torus (JET)29 in the UK and the Tokamak Fusion Test Reactor (TFTR)30 in the US. Notably, ITER is being designed using data obtained from these three large tokamaks, as well as from results scaled up from smaller and medium-sized devices around the world.

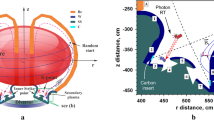

In this paper, we analyze ELM precursors and their nonlinear dynamics for a Type-I ELM in JT-60U discharge E049217, with particular attention to the triggering problem. We used the unique magnetic-diagnostics techniques installed on JT-60U, which are suitable for detecting lower-m/n modes (where m and n are the poloidal and toroidal mode numbers, respectively) with the fast temporal resolution of 500 kHz (Fig. 1). An unprecedented set of eight saddle-loops detect the radial component of the magnetic perturbations, while the poloidal components are measured simultaneously using a set of 16 poloidally distributed magnetic sensors. Other diagnostics (synchronized with the magnetics) include a detector for the deuterium-alpha (\(\:{D}_{\alpha\:}\)) emission from the divertor region (1 MHz), a soft X-ray (SX) array (500 kHz), electron-cyclotron-emission (ECE) radiometry (50 kHz), and reflectometer diagnostics (1 MHz).

JT-60U tokamak and its diagnostics. (a) Three-dimensional (3D) view of the vacuum vessel (the donut-shaped chamber), the plasma shape (the last closed flux surface, LCFS), and the rational flux surface at the safety factor q = m/n = 4 (including the magnetic-field-line on the surface q = 4 that performs one poloidal turn for every four toroidal turns). The toroidal arrangement of the diagnostics is illustrated by the clockwise arrow projected in the X–Y plane at Z = − 6 m. (b) A poloidal cross-section of the plasma, indicating the arrangement of the diagnostics. The zero position (φ = 0) for the toroidal angle is shown in (a), where the scale begins to rotate clockwise between φ = 0° and 360° in the direction of the plasma current IP and the toroidal magnetic field BT.

For the discharge analyzed here, the plasma current was Ip = 1.6 MA, the toroidal magnetic field was BT = 4 T, the safety factor at the 95% flux surface was q95 ~ 4.42, and the discharge was sustained using a neutral-beam-injection (NBI) power PNBI = 14 MW (see Supplementary Fig. 1). At a normalized electron collisionality \(\:{\nu\:}_{e}^{*}\) ~ 0.25 \(\:\pm\:\) 0.15 at the top of the pedestal, the corresponding ELM energy loss from the pedestal, normalized by the energy stored in the pedestal region, was \(\:{\varDelta\:W}_{ELM}^{Avg.}/{W}_{Ped}\) ~ 10% \(\:\pm\:\) 2% [Fig. 2(a)], which is consistent with empirical scaling from Type-I ELMs in conventional tokamaks. The operating point in the pressure gradient \(\triangledown\:p_{ped}\) and the current density jped—with error bars of ~ 20% [Fig. 2(b)] that we calculated using some available profile-measurement data [Figs. 2(c)\(\:-\)(d)]—are close to (but still below) the marginal-stability boundary predicted for a peeling–ballooning (PB)-driven ideal kink mode with an intermediate/high-n-value (see Methods: “PB-mode and linear-MHD stability analysis”)31,32,33,34,35,36,37.

Characterization of the Type-I ELMs in JT-60U discharge E049217. (a) Normalized ELM size vs. normalized electron collisionality, along with data from the international database (IDB) from AUG, DIII-D, JET, and JT-60U. (b) Stability diagram calculated using the MARG2D code. Radial profiles of (c) the measured ion and electron temperatures Ti and Te and the electron density ne, and (d) the calculated total pressure P, current density j, and safety factor q.

Previous studies have shown that multiple plasma filaments are ejected in an ELM. In MAST18,38,39 photographs, up to 10 filaments were ejected in a single ELM. Similar observations were reported for NSTX40, AUG38,39,41, and DIII-D42. These observations indicate that the ELM is an intermediate-n phenomenon. A single filament was observed in NSTX43stimulating further investigation into the role of the n = 1 mode as a potential trigger for Type-I ELMs (see the Methods: “Comparison with previous observations at various tokamaks around the world”).

The problem of triggering an ELM cycle in a tokamak is not clearly obvious, however. In fact, the temporal evolution of the pedestal parameters almost saturates just before the ELM onset, when the growth rate itself increases abruptly within a very short timescale. “When, where and how it was triggered” are described in the following sections.

The mechanism of explosive growth in ELMs is vitally important. Such growth is a characteristic of nonlinear ideal ballooning theory, which predicts explosive behavior as a consequence of a finite-time singularity in the model44. Although our analysis focuses on one discharge (i.e., E049217) in one tokamak (i.e., JT-60U), we report experimental observations of explosive growth of a tearing-parity mode.

Definition of ELM-onset time

The definition of the ELM-onset time, denoted by \(\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\equiv\:0\), is crucial, particularly in addressing the triggering problem. Defining the time \(\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\equiv\:0\) properly enables a detailed look at the complex interrelationships of causation leading to the ELM onset.

In the present work, rather than relying on the \(\:{D}_{\alpha\:}\) emission itself, we use its time derivative, \(\:d{D}_{\alpha\:}/dt\), determining \(\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\equiv\:0\) to be the time at which the value of \(\:d{D}_{\alpha\:}/dt\) exceeds a certain level. We determined the threshold value of \(\:d{D}_{\alpha\:}/dt\)—expressed as \(\:d{D}_{\alpha\:}/dt\) ≥ 1 in units of the arbitrary value of the \(\:{D}_{\alpha\:}\) signal normalized to the time in milliseconds, \(\:{\delta\:D}_{\alpha\:}\)/ms—by comparing it to a statistically significant number of ELMs that occur periodically under a constant input-power level with a fixed position for the divertor hit-point. The minimum detectable level for an ELM spike is typically \(\:\left|d{D}_{\alpha\:}/dt\right|\) ≤ 0.5. Notably, this definition applies to a majority of cases in discharge E049217. Hence, the time at which \(\:d{D}_{\alpha\:}/dt\) ≥ 1 is a more accurate indicator of the ELM onset rather than the \(\:{D}_{\alpha\:}\) value.

As shown in Figs. 3(a) and (d), the conditional-average \(\:{D}_{\alpha\:}\) signal, \(\:{I}_{{D}_{\alpha\:}}^{AVG}\), exhibits an explosive increase from the ELM onset (i.e., from \(\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\equiv\:\) 0) to its local maximum value at \(\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\approx\:\) 53 µs (\(\:\equiv\:{\tau\:}_{ELM}^{{D}_{\alpha\:}}\)). However, there is a relatively small increase in \(\:{I}_{{D}_{\alpha\:}}^{AVG}\) at \(\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\approx\:\) 0 ms—only a few percent of its local maximum value—from its base level during the precursor phase (e.g., within the range − 1 ms \(\:\le\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\le\:\) 0 ms, corresponding to 97–100% of the inter-ELM phase. As shown in Figs. 3 (b) and (e), the conditional-average \(\:d{D}_{\alpha\:}/dt\) signal (\(\:{I}_{{dD}_{\alpha\:}/dt}^{AVG}\)) reaches its local maximum at \(\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\approx\:\) 29 µs (\(\:\equiv\:{\tau\:}_{ELM}^{{dD}_{\alpha\:}/dt}\)) following the ELM trigger.

Definition of time relative to the ELM onset and the timescale for ELM collapse. The temporal evolution of (a), (d) the \(\:{\text{D}}_{{\upalpha\:}}\) signal, (b), (e) the absolute value of its time derivative \(\:\left|d{D}_{\alpha\:}/dt\right|\), and (c), (f) the soft-X-ray signals from both the chord passing through the SOL to the pedestal (Channel 6) and the chord from the separatrix to the inner hit-point (Channel 5) during an ELM cycle were constructed by organizing the data with respect to the time relative to the closest ELM; at this point, the time from the start of the ELM (\(\:\varDelta\:{\text{t}}_{\text{E}\text{L}\text{M}}\equiv\:0\)) is defined by \(\:\text{d}{\text{D}}_{{\upalpha\:}}/\text{d}\text{t}\) ≥ 1. (Left column) Full-time trace for ± 50% of an inter-ELM cycle. (Right column) Expanded time trace for ± 1.5% of the inter-ELM cycle, showing the typical time constants for the rise in the \(\:{\text{D}}_{{\upalpha\:}}\) signal and its time derivative at the ELM, as well as for the collapse of the pedestal observed in the SX signals.

The use of this criterion for the ELM onset time guarantees that the explosive dynamical event is triggered consistently despite variations in divertor conditions (e.g., minor differences in the hit-point that result in changes in the value of \(\:{D}_{\alpha\:}\)). Although a few microseconds of uncertainty may still exist, the criterion \(\:d{D}_{\alpha\:}/dt\) ≥ 1 defines the ELM onset effectively. Figures 3(c) and (f) show the conditional-average SX signals from the chords passing through the scrape-off layer (SOL) to the pedestal, \(\:{I}_{SX-Ch.6}^{AVG}\), and from the separatrix to the inner hit-point, \(\:{I}_{SX-Ch.5}^{AVG}\). Both quantities are nearly stationary until the ELM onset (i.e., throughout the range \(\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\le\:0\) ms). At the time of ELM onset, \(\:{I}_{SX-Ch.6}^{AVG}\) begins to decrease, demonstrating that the pedestal begins to collapse after a timescale \(\:{\tau\:}_{ELM}^{SX}\approx\:\) 228 µs. Conversely, \(\:{I}_{SX-Ch.5}^{AVG}\) begins to increase at the ELM onset (similar to the behavior of the \(\:{D}_{\alpha\:}\) signal in the range 0 \(\:\le\:\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\le\:\) 100 µs), and it then decreases as \(\:{I}_{SX-Ch.6}^{AVG}\) decreases until \(\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\:\sim\) 200 µs (\(\:{\tau\:}_{ELM}^{SX}\)). Notably, the value of \(\:{\tau\:}_{ELM}^{SX}\) is roughly comparable the values of \(\:{\tau\:}_{ELM}^{{D}_{\alpha\:}}\) and \(\:{\tau\:}_{ELM}^{{dD}_{\alpha\:}/dt}\). The former corresponds to the timescale of transport in the confined plasma following the ELM-crash, while the latter indicates the start of ejection at the plasma surface. The latter is a more typical MHD timescale for the triggering of a sudden explosive plasma phenomenon.

Observations of the m/n = 4/1 mode across the elms

In this study, we begin by examining two Type-I ELMs with similar visual appearances: case A (t = 8097.074 ms) and case B (t = 8271.890 ms), which are shown in Fig. 4. The multiplexed magnetic perturbations observed by the saddle-loops (i.e., the time-derivative values for the radial components of the magnetic-field fluctuations at the wall, \(\:{dB}_{r}^{FFT}/dt\)) provide insights into the ELM-induced low-n MHD modes for both case A and case B, as shown in Figs. 4(b) and (b'), where the n = 1 mode is particularly noticeable. Here, we identify each toroidal mode separately via a fast-Fourier-transform (FFT) analysis. For both cases, the values of \(\:{dB}_{r}^{FFT}/dt\)—especially for n = 1—begin to grow rapidly at \(\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\approx\:\) 0 ms, while the trends in their growth rates across the triggering time are subtly different for each case, as displayed in the \(\:{\text{D}}_{{\upalpha\:}}\) signal; we have therefore selected these two cases for examination in more detail. Notably, the value of \(\:{\tau\:}_{ELM}^{{D}_{\alpha\:}}\) for case A (B) is longer (shorter) than the conditional-average value of 53 µs; it is \(\:\approx\:80\:\mu\:s\) for case A and \(\:\approx\:30\:\mu\:s\) for case B.

The low-n MHD modes during ELMs. (a) Temporal evolution of the stored energy, Wdia, and of the Dα intensity at the lower divertor. The lower two panels show the expanded temporal evolution of the radial magnetic perturbation, \(\:{dB}_{r}^{FFT}/dt\), as a function of the toroidal mode number, n, evaluated using FFT analysis, and of the Dα intensity across the ELM during (b) t = 8,097.074\(\:\:\pm\:\:\)0.25 ms and (b') t = 8,271.890\(\:\:\pm\:\:\)0.25 ms. Additional details are presented in Figs. 5, 6, 7 and 9. The levels of the contour plots in panels (b) and (b') are auto-scaled.

Figure 5 shows the spatiotemporal evolution of the magnetic-perturbation amplitudes during the ELM event for case A (the two left columns) and case B (the two right columns). We evaluated the change in the radial component of the amplitude for the n = 1 mode (\(\:{\delta\:B}_{r,n\:=\:1}^{FFT}\)) using an FFT analysis, as shown in Figs. 5(a), 5(c), and 5(e) for case A and Figs. 5(a'), 5(c'), and 5(e') for case B, whereas we used the raw data for the poloidal component (\(\:{\delta\:B}_{\theta\:}\)), as shown in Figs. 5(b), 5(d), and 5(f) for case A and Figs. 5(b'), 5(d'), and 5(f') for case B. For both cases, Fig. 5 reveals a rapid expansion of the poloidal-mode structure, with four peaks in the value of \(\:{\delta\:B}_{\theta\:}\) that are synchronized with an abrupt growth in the n = 1 mode approaching the ELM onset; this indicates a poloidal-mode number m = 4 corresponding to the MHD mode with n = 1. The timescale for the growth of the m/n = 4/1 mode for case A is longer than that for case B, as shown by the corresponding values of \(\:{\tau\:}_{ELM}^{{D}_{\alpha\:}}\) and/or \(\:{\tau\:}_{ELM}^{{dD}_{\alpha\:}/dt}\), while the magnetic-perturbation amplitudes for both cases exhibit similar values when compared at the time of ELM onset (i.e., at \(\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\approx\:0\) ms). Notably, the toroidal and poloidal angles at which the mode has local maximum and minimum values at the ELM onset differ between cases A and B, indicating that this observational result is independent of the resonance conditions specific to the device (if such exist).

Magnetic perturbations with m/n = 4/1 during two ELMs. The amplitudes of the radial (i.e., the n = 1 component evaluated using FFT analysis) and poloidal magnetic perturbations on the wall for \(\:{\delta\:B}_{\text{r},\text{n}\:=\:1}^{\text{F}\text{F}\text{T}}\) (upper row) and \(\:{\delta\:B}_{\theta\:}\) (middle row) as a function of (a, a'), (b, b') toroidal/poloidal position and time, (c, c'), (d, d') toroidal/poloidal position, and (e, e'), (f, f') top/cross-section view. We obtained the values in (e, e'), (f, f') by integrating the measured values of \(\:{dB}_{r,\theta\:}/dt\) starting at a time corresponding to the left boundary of the displayed time interval. The left column corresponds to the ELM triggered at t = 8,097.074 ms [case A: (a)–(f)] and the right column (separated by a vertical dash-dot line) to the ELM triggered at t = 8,271.890 ms [case B: (a')–(f')]. The levels of the contour plots are auto-scaled for each case, while the vertical (angles) and horizontal (time) axes are in the same range for both cases.

These observations suggest that the MHD mode with m/n = 4/1 that triggers an ELM is present at the low-order rational surface with q = m/n = 4, which is located at approximately the normalized radius\(\:\:{\:\rho\:}_{q\:=\:4}\:\approx\:\) 0.92 in the middle of the region just outside the top of the pedestal at \(\:{\rho\:}_{ped.}\approx\:\) 0.89 (qped. ~ 3.75) and inside the q95 surface (i.e., \(\:{\rho\:}_{ped.\:<\:}{\rho\:}_{q\:=\:4\:<}\:{\rho\:}_{{q}_{95}}\)).

Magnetic diagnostics have the well-known limitation that only lower-n mode numbers can be measured due to the coarse resolution at positions away from the plasma. Thus, determining the dominant modes is difficult because intermediate and higher-n mode numbers cannot be detected. Nevertheless, lower-n modes were present not only in cases A and B but also in almost all ELMs during discharge E049217 and in other similar experimental conditions at JT-60U (see Supplementary Fig. 2). Variations within the physical mechanism that causes the ELM phenomenon may therefore be present in the Type-I ELM regimes, at least in JT-60U. In the present research, we therefore focus on the lower-n MHD modes, moving beyond the current paradigm for the triggering problem. However, in this study, we are unable to assess the high-n activity in detail using complementary diagnostic methods (e.g., ECE-based toroidal mode analysis). However, the specific shot discussed in this paper has been examined previously45and that analysis supports the usual hypothesis that PB modes become unstable shortly before the onset of an ELM (i.e., in the precursor phase), with a dominant n-value of 15 (the range n = 12–17 is marginally unstable) based on linear MHD calculations. The n-value has also been evaluated as n = 8–10 or 14–16 using two ECE diagnostics installed 60° apart along the toroidal direction (which is suitable for identifying larger n-values, such as n ≥ 6). These n-values were determined assuming that the precursor rotates with the same toroidal rotation speed as the carbon-impurity ions; in addition, the mode parity (as well as direct identification of the n-value using magnetic diagnostics) was not considered then (see Methods: “Comparison with previous observations at various tokamaks around the world”).

Identification of tearing-parity modes as ELM precursors

In various tokamaks, ELM precursor activities have long been observed, and fluctuations in the edge density, temperature, and magnetic-field strength have been observed over a wide range of frequencies (see Methods: “Additional observations about the turbulence near collapse”)45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52.

Figures 6(a, a')–(c, c') present the fluctuations in the electron temperature (and its gradient, measured using ECE) and in the density (measured using reflectometers) around the q = 4 surface in the middle of the pedestal. Notably, the ECE data determined the optical thickness to be ~10 or higher at \(\:{\rho\:}_{ECE}\le\:0.95\). Therefore, the power radiated from the pedestal region and used for this analysis was directly proportional to the local electron temperature.

Spatiotemporal evolution of the tearing-parity mode, accelerating at the ELM onset. This figure shows the temporal evolution (a, a') of the electron-temperature profile measured using ECE and of the \(\:{\text{D}}_{{\upalpha\:}}\) emission, (b, b') of the gradient of the electron-temperature profile and the time derivative of the \(\:{\text{D}}_{{\upalpha\:}}\) emission, and (c, c') of the density fluctuations measured by the relative phase-change of the reflectometer signals at 34 and 36 GHz (corresponding to the cutoff densities 1.4 and 1.6\(\:\:\times\:\:\)1019 m−3, respectively), and of the n = 1 magnetic perturbation \(\:\left|{dB}_{r}^{n\:=\:1}/dt\right|\) (the absolute maximum value of the difference signal between the saddle-loops facing each other). The levels of the contour plots are the same for both cases, while the horizontal (time) axes are different in case A and case B. The X- and O-point timings are indicated by the vertical dashed and solid lines, respectively. Radial profiles are shown for (d, d') the electron temperature and the reconstructed safety factor q and (e, e') the electron-temperature gradient and the ELM-averaged electron density. The left and right columns (separated by the vertical dash-dot line) correspond to the ELM triggered at t = 8,097.074\(\:\:\pm\:\:\)0.175 ms [case A: (a)–(e)] and at t = 8,271.890\(\:\:\pm\:\:\)0.175 ms [case B: (a')–(e')], respectively. In Figs. 6(d, d') and 6(e, e'), as guides to the eye, the normalized minor radius at the q = 4 surface is indicated by the vertical dashed line, and the radial width of the magnetic island \(\:{w}_{ECE}\approx\:0.07\pm\:0.01\) (corresponding to a half-width of ~ 3 cm) is indicated by the pair of vertical dotted lines.

These fluctuations occur irregularly and with varying phases over a frequency range of ~ 10 kHz, and they become significant before the ELM onset. In case A, the fluctuations begin to grow at \(\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\approx\:\) −0.85 ms, and the mode growth saturates between \(\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\approx\:\:\)−0.75 ms and −0.25 ms, resulting in a quasi-stationary state. In this phase, the base level of the \(\:{D}_{\alpha\:}\) signal remains elevated, and the mode exhibits rapid growth beginning at \(\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\approx\:\:\)−0.25 ms up to the ELM onset. The mode exhibits quasilinear growth over time, like that seen in case B. During these precursor phases, the magnetic signal [the n = 1 component shown in Fig. 6(c)] fluctuates by up to 0.01 T/s, and it is weakly correlated with the ECE and/or reflectometer data; e.g., at \(\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\approx\:\:\)−0.65 ms for case A and \(\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\approx\:\:\)−0.08 ms for case B.

A crucial observation is the radial phase inversion observed in the temperature profile \(\:{T}_{e}^{ECE}\) [Fig. 6(d, d')] across the q = 4 surface in the middle of the pedestal during the precursor phase. We observed this in both cases A and B, and it provides clear evidence of a tearing-parity mode as a precursor to an ELM (see Supplementary Fig. 3). In particular, the ECE data indicate that the amplitude of the tearing-parity mode increases marginally as the ELM onset approaches. The behavior of the mean temperature gradient \(\:{-\nabla\:T}_{e}^{ECE}\) [Fig. 6(e, e')] at q ~ 4 supports the presence of a tearing-parity mode in which \(\:{-\nabla\:T}_{e}^{ECE}\) increases at the X-point time and decreases at the O-point time, in both cases A and B. We estimate the normalized radial width of the magnetic island during the precursor phase to be \(\:{w}_{ECE}\approx\:0.07\:\pm\:\:0.01\) (corresponding to a half-width of ~ 3 cm for the island), with \(\:{-\nabla\:T}_{e}^{ECE}\) just outside the q = 4 surface becoming steeper at the X-point of the tearing mode than at the O-point.

Unfortunately, it is difficult for ECE to trace the temperature and its fluctuations immediately after an ELM due to the generation of nonthermal electrons in the pedestal region, as illustrated in Figs. 7(a)–7(b) and Supplementary Fig. 4. The generation of nonthermal electrons at the ELM onset also supports the hypothesis that a tearing-parity mode exists that is characterized by a strong electric field aligned parallel to the magnetic-field-line at the X-point (where fast reconnection takes place), which can accelerate electrons to produce a higher-energy component in the tail of the distribution function.

Precursor signals with tearing parity and the evolution of the nonthermal component across the ELMs. This figure shows the temporal evolution of the electron temperature on a log-scale at \(\:{\rho\:}_{ECE}\:=\:\)0.92 (q ≤ 4) and at \(\:{\rho\:}_{ECE}\:=\:\)0.95 (q ≥ 4), as measured using ECE, together with the \(\:{\text{D}}_{{\upalpha\:}}\) emission just before the onset of the ELM triggered at (a) t = 8,097.074 ms (case A) and (b) t = 8,271.890 ms (case B), respectively. The vertical dashed and solid lines correspond to the X- and O-point timings, respectively; they are the same as those shown in Figs. 6(a)–(c).

The hypothesis that an ELM is triggered by a tearing-parity mode differs from the conventional view that a Type-I ELM is triggered by a kink/peeling-parity mode and demonstrates that variations exist within the physical mechanism of the ELM phenomenon. Whether the tearing mode actually remains dominant during the final collapse phase remains an open question for future research.

It is well established that when magnetic reconnection occurs, the strong parallel electric field at the X-point accelerates electrons along magnetic field lines. If fast reconnection is indeed taking place, as in the present case, strong electron acceleration is expected. This is supported by the strong ECE emission shown in Figs. 7(a) and 7(b) and Supplementary Fig. 4. However, due to the current time resolution, quantitatively linking this strong ECE emission to the energetic electron energy with precise error bars is not possible. While we consider this to be suggestive evidence, it may still be regarded as speculative. With future improvements in ECE diagnostics—such as ECE from a tangential field of view, or another techniques—more direct evidence may become available. From this perspective, we believe that the present study offers a meaningful basis to inspire further experiments and analyses.

Onset criteria and timescale for a tearing-parity mode

To investigate the evolution of an m/n = 4/1 tearing-parity mode across the ELM, we calculated the amplitude of the radial-field perturbation at q = 4, \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{n}^{q\:=\:4}\), using a current-filament model (Fig. 8). We used a static model with a constant background plasma, and we determined the filament current by comparing the measured and calculated values of the perturbed magnetic field at the wall position (see Methods: “Analysis of the magnetics”).

Comparing experiment and calculations for magnetic perturbations at the ELM. (a) Radial and (b) poloidal components of the amplitude of the magnetic perturbations due to the m/n = 4/1 mode at the diagnostic locations. The eight sets of saddle-loops for Br are indicated by the magenta rectangles along \(\:{\uptheta\:}\:=\:0^\circ\:\) in (a), and the 16 sets of magnetic sensors for the Bθ measurements are shown by the yellow-filled black circles along \(\:{\upvarphi\:}\:=\:288^\circ\:\) in (b). To obtain these results, we employed a set of finite current filaments with phases differing by δφ = π radians to the magnetic-equilibrium field on the q = 4 surface. The angular diagrams show the experimental measurements and calculated values for (c) the radial and (d) the poloidal components (normalized to their maximum absolute values) at the ELM onset for tELM = 8,271.890 ms (case B). (e) Poincaré plot for a filament current of 400 A (determined by comparing the amplitudes of the poloidal magnetic perturbations between experiment and calculation at the ELM onset). This plot exhibits four magnetic-island structures at the poloidal angles χ = 0, ±90°, and 180° in the straight-field-line coordinate system (solid green lines). The poloidal coordinate θ used in (a)–(d) is also shown in (e), where the radial coordinate starts at the geometrical axis (R = 3.32 m, Z = 0 m) and ends at the wall.

As shown in Fig. 9, we compared the onset criteria for the mode it to a statistically significant number of cases selected from discharge E049217, including cases A and B (see also Supplementary Figs. 1–2 and 4). This shows that the magnetic-perturbation threshold exceeds ~ 10 \(\:\pm\:\) 5 Gauss at the ELM onset. The timescale for the development of magnetic braiding and stochasticity in a hyper-resistive tearing mode—which causes explosive growth and triggers an ELM—has been modeled in Ref. 53; for the present parameters, it is estimated to be \(\:{\tau\:}_{braid}\) ~ 80 \(\:\mu\:s\) (see Methods: “Estimating the timescale of the explosion”). This value is comparable to the experimental observations that an ELM collapses between 30 \(\:\mu\:s\) and 100 \(\:\mu\:s\) (for the fastest and slowest cases discussed here), which provides partial support for this theoretical model of the triggering and collapse of an ELM. This validation is based on the results from two independent tests: the condition for the onset of magnetic braiding and the timescale leading to the explosive collapse.

The onset criteria and the timescale for the tearing-parity mode. This figure shows the temporal evolution of (a) the absolute value of the time derivative of the \(\:{\text{D}}_{{\upalpha\:}}\) signal, \(\:d{D}_{\alpha\:}/dt\), and (b) the amplitude of the radial-field perturbation at q = 4, \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{n}^{q\:=\:4}\), for six cases selected from discharge E049217, including cases A and B. The dashed lines shown in (b) indicate the temporal evolution of the modeled value of \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{n}^{q\:=\:4}\propto\:{\left\{1-\left(\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}/{\tau\:}_{braid}\right)\right\}}^{-2}\), with various time constants for the magnetic braiding and stochasticity of the hyper-resistive tearing mode that causes explosive growth and triggers the ELM. (c) The relationship between \(\:d{D}_{\alpha\:}/dt\) and \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{n}^{q\:=\:4}\) during the time span \(\:-100\:\mu\:s\le\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\le\:100\:\mu\:s\); the color key is shown in panel (a).

Visualization of a stochastic edge magnetic field associated with the ELM onset

The behavior of the normalized radial width of the magnetic island obtained from the Poincaré plot of the magnetic field lines for the m/n = 4/1 mode is shown in Figs. 10 (see Methods:”A coordinate system based on straight field lines”). This figure shows that the width of the island saturates at \(\:{w}_{mag}^{Poincare^{\prime}}\) \(\:\approx\:0.065\pm\:\:0.015\). In contrast, the cylindrical model shows that \(\:{w}_{mag}^{Cylinder}\) continues to increase as the value of \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{n}^{q\:=\:4}\) increases, reaching the value \(\:{w}_{ECE}\) \(\:\approx\:0.07\pm\:0.01\) during the precursor phase prior to the ELM onset, when \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{n}^{q\:=\:4}\) exceeds ~10 Gauss.

Structure of the magnetic field lines across the ELM. (a) Relationship between the width of the magnetic island and the amplitude of the magnetic perturbation at the q = 4 surface, \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{\text{B}}}_{\text{n}}^{\text{q}\:=\:4}\). The black dashed line is obtained from the cylindrical model, while the blue solid line is from the Poincaré plot. The vertical dotted line corresponds to the time of the ELM onset, while the horizontal dotted lines are eye-guides for the size of the magnetic island at the threshold for stochastization. (b)–(g) A net-drawing of the Poincaré plot using the straight-field-line coordinate system in the \(\:\rho\:-\chi\:\) (radial\(\:-\)poloidal) plane at a specific toroidal angle, with filament currents of 50, 200, 400, 600, 1000, and 2000 A (corresponding to \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{\text{B}}}_{\text{n}}^{\text{q}\:=\:4}\) = 1, 4, 8, 13, 21, and 42 Gauss) from the bottom to the top panels, respectively. The radial width of the magnetic island is \(\:{w}_{mag.}\approx\:0.065\), as evaluated from the Poincaré plot for the saturated phase; it is shown at the top of Fig. 10 (b) as a guide to the eye.

These simulation results provide a semiquantitative understanding of the threshold condition for the emergence of a stochastic edge magnetic field associated with the ELM onset, as discussed above. In Fig. 10(b)–(g), the nested magnetic island changes into a weakly stochastic configuration in the pedestal region, with the value of \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{n}^{q\:=\:4}\) exceeding the threshold of ~ 10 G during this transition. The error in identifying the threshold size of the island required to accelerate the tearing mode toward a stochastic edge magnetic field at the ELM onset is ~ 30% or less. This suggests that a value within the range \(\:{w}_{mag}^{Poincare^{\prime}}\:=\:0.065\:\pm\:\:0.015\) may result in rapid reconnection triggered by the overlap of multiple islands and/or by the reconnection of sub islands surrounding the main island (see the Methods: “Model for the stochastization of magnetic field” and Discussion for more detail)53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61.

These simulated features—including the presence of an n = 1 structure and inferred stochastization near the edge as indications of a tearing mode—seem ubiquitous in nonlinear PB-mode simulations62,63,64,65,66,67,68while the nonlinear ELM dynamics are complex and remain an area of active study. The n = 1 structures seen in the nonlinear PB-mode simulations are produced by the interaction of the nearest unstable modes and the magnetic perturbations associated with the stochastic parts of the edge region during ELMs triggered by the PB-instability. Although the n = 1 island appears in conventional models, a distinctive feature of the present ELM collapses is that it is a tearing-parity mode (not a kink/peeling-parity mode) with m/n = 4/1 that triggers the ELM.

Discussion

A low-n mode that grows explosively at the ELM onset, with the tearing-parity mode as a precursor—as identified in the present study—is a solid incremental addition to the body of work on ELM studies. The most important point of this paper is that—under the conditions in the lower-\(\:{\nu\:}_{e}^{*}\) regime of Type-I ELMy H-mode discharges at the JT-60U (E049217)—it regards ELMs as a triggering problem for a magnetized-plasma explosion and presents it as a consistent phenomenon in the evolution of a tearing-parity mode with m/n = 4/1from the precursor to the collapse; in other words, the ELM precursor and its trigger are not two separate phenomena.

Notably, the findings of this study may significantly influence control strategies for next-generation fusion devices. If the nonlinear evolution of the tearing mode can indeed trigger ELM onset, it will be necessary to develop control methods based on the nonlinear conditions of the tearing mode—alongside those currently being considered for the PB-mode model. Control strategies require both the selection of a measurable quantity and an actionable control knob. In next-generation fusion devices, (a) the availability of control knobs and (b) the diagnostic observation window are limited. Measurement capabilities are expected to be more constrained than at present. Therefore, the diversity of ELM-triggering mechanisms could substantially impact control strategy decisions—depending on how we prioritize (a) and (b), and whether the PB and tearing modes must be accounted for, rather than the PB-mode alone.

The characteristic mechanisms underlying this observation can be divided into (1) the emergence and slow growth of a tearing-parity mode (the so-called precursor), (2) a rapid increase in the growth rate in a very short period (the so-called triggering problem), and (3) the subsequent rapid growth of the n = 1 mode. Steps (2) and (3) cannot be explained by classical electrical resistivity. Based on this division, we discuss the findings of this paper and organize the evidence, hypotheses, and remaining issues that need to be verified in the future.

First, Connor69 has shown theoretically for a classical resistive tearing mode that a current gradient causes instability when an H-mode pedestal current is formed. In the present experiment, we observed the electron-temperature fluctuations \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{T}}_{e}^{ECE}\) associated with the precursor. At electron temperatures ~ 1 keV, it is not a bad approximation to assume that the electrons follow the magnetic field lines. There is an antisymmetric fluctuation of \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{T}}_{e}^{ECE}\) (i.e., a phase inversion) at the plane q = 4 during the precursor, which supports the judgment that it is a weak n = 1 tearing mode up to the triggering time [phase (1)]. Notably, the possibility of a tearing-parity mode as a precursor to ELMs has previously been suggested69. Compared to those earlier studies, our study provides clear advances, including: (a) experimental clarification of the relationship between ELM generation and the tearing-parity mode, (b) experimentally quantification of its the nonlinear evolution, and (c) observation of quasi-quantitative agreement between the nonlinear evolution and theoretical models.

Next, we consider the rapid increase in the growth rate in a very short time [phase (2)]: the so-called triggering problem. It has been pointed out that the current-diffusion coefficient increases in a plasma due to electromagnetic fluctuations and other reasons54,55and it has been thought that destabilization of the tearing mode due to current diffusion56 may be the main cause when the electrical resistance is small at high temperatures. When the threshold is reached—due to multiple islands overlapping57,58—and magnetic-surface breakdown occurs, the growth rate increases rapidly due to the current-diffusion coefficient59,60,61. In the scenario presented in this paper, however, we hypothesize that a magnetic-surface breakdown is the trigger. The direct experimental verification of this hypothesis is currently difficult (except for a few indirect examples)70. From the experimental observations mentioned above, however, the deformation of the magnetic surface in the m/n = 4/1 mode can be determined and compared with the amplitude that causes the magnetic-surface breakdown. We determined the threshold width of the island for the m/n = 4/1 mode that causes magnetic-surface breakdown by superimposing a resonant m/n = 4/1 magnetic field on the magnetic-field structure reconstructed from the experiment. The half-width of ~ 3 cm is comparable to the width of the island obtained from the ECE diagnostic just before triggering occurs. This does not contradict the hypothesis that stochastization of the m/n = 4/1 island is the ELM trigger. As shown in this study, magnetic field calculations simulating JT-60U conditions indicate that the magnetic field lines become stochastic under these conditions. The lowest-order effect on Ohm’s law in such a situation can be expressed as hyper-resistivity as described previously55.

Finally, we examine the stage of rapid growth [phase (3)]. Once the conditions for this phase are satisfied, a positive feedback loop is activated in which the increase in the current-diffusion coefficient accelerates the growth of the tearing mode, which in turn increases the current-diffusion coefficient. This results in phase (3), in which the tearing mode grows rapidly to a large amplitude. Of course, fast reconnection occurs simultaneously, so a strong electric field develops along the magnetic-field lines near the X-point of the magnetic island, accelerating the electrons. The overflow observed in the ECE measurement is consistent with reconnection accompanying the fast growth of the m/n = 4/1 mode, although the specific mechanism responsible for accelerating the electrons is not fully understood.

Strictly speaking, the perturbation cannot be definitively identified as a tearing-parity mode for \(\:\varDelta\:{t}_{ELM}\ge\:-10\:\mu\:s\), as the ECE signal is influenced by energetic electrons. However, the tearing-parity mode appeared to continue to grow rapidly, as evidenced by the fact that the growth rate of the n = 1 mode in Fig. 9(b) closely follows a curve with the same shape as predicted by Eq. (a3). This smooth and continuous evolution of the growth rate indicates that an alternative interpretation—namely, that the discharge first transitions through a resistive-instability boundary to drive the tearing mode, which then saturates, followed by a transition to an ideal MHD boundary that triggers the standard peeling-ballooning mode and an ELM—is unlikely.

In this paper, we have thus examined one possible mechanism for phases (1)–(3) of the ELM phenomenon. Although we have provided a quasi-quantitative verification using the conditions of the magnetic-surface breakdown, in the future we will be able to test this scenario more rigorously by examining the reconnection electric field in the magnetic-field line direction, both from MHD calculations and from observations such as electron acceleration along the magnetic-field-line direction.

In conclusion, we have revisited the study of ELM precursors and their nonlinear dynamics in a JT-60U discharge using fast and synchronized diagnostics and improved analysis techniques, and we have found that an explosive low-n mode with a tearing-parity precursor mode is present in Type-I ELM events. Numerical calculations using a hyper-resistive model for magnetic braiding and stochasticity reveal that the size of the magnetic island at the ELM onset reaches a critical value, at which magnetic stochasticity is generated near the separatrix at the X-point of the tearing mode. At this point, the mode amplitude exceeds a critical threshold of ~ 10 G at q = 4, triggering an ELM event within a few tens of microseconds. The experimental duration of the collapse phase is comparable to the timescale predicted by a preexisting theoretical model for large-scale deformations. These results suggest that the onset of magnetic stochasticity acts as the catalyst for the ELM and thus that the subsequent nonlinear and rapid magnetic reconnection induces the collapse. Although this conclusion is based on the analysis of one discharge in one tokamak, this article provides a new paradigm for understanding Type-I ELMs, demonstrating that various possibilities exist for the triggering mechanism. Although the present results do not challenge the predictive capability for ITER—which certainly needs to be considered later in a larger international effort—we have obtained valuable insights by presenting a consistent method for analyzing the problem of triggering a magnetized-plasma explosion.

Finally, we discuss future prospects. In particular, it is important to consider the trade-off between the detailed, high-resolution analysis of a single discharge (E049217) and the broad insights that could be gained from statistical analysis across multiple discharges (see also Methods, subsection “Generalizability and statistical robustness of conclusions”). While focusing on a single discharge allows for precise temporal and spatial diagnostics, it inherently limits the generalizability of the findings. Addressing this balance may help contextualize the study’s contributions and guide future research directions.

Methods

PB-mode and linear-MHD stability analyses

The conventional idea for a Type-I ELM is that its nonlinear evolution is triggered when the linear MHD stability limit defined for an ideal PB mode with an intermediate-n number is exceeded (see also Ref. 31–37 and therein). Models like EPED34 have been rigorously validated in predicting pedestal width and height, and they can be used in turn to help predict the overall confinement and performance of ITER. Furthermore, the correlation between the onset of a Type-I ELM and the PB instability has been noted across more than two orders of magnitude in the dimensionless parameters for existing devices, such as the collisionality \(\:{\nu\:}_{e}^{*}\).

To evaluate the n-value analytically, the utilized values of \(\triangledown\:p_{ped}\text{ and }\:j_{ped}\) need to be imposed in the stability calculation. By considering various non-ideal effects—such as ion diamagnetic drift36, the influence of the separatrix geometry33, finite resistivity37, etc.—in linear MHD-mode calculations, it is possible to bring the operating point as close as possible to the marginal-stability boundary without artificially adjusting the evaluated operating point in\(\triangledown\:p_{ped}\text{ vs. }\:j_{ped}\) space. Even if the values of \(\triangledown\:p_{ped}\text{ and }\:j_{ped}\) could be evaluated with higher accuracy (e.g., with an error of 1% or less, by means of statistical analyses of datasets with high-resolution measurements), the marginal-stability boundary itself would still be uncertain, as it depends on the growth rate of the expected instability being fixed at a certain value. These approaches show that deviations from the ideal MHD picture are to be expected. In particular, the classical resistive instability (the so-called peeling/tearing mode) does not depend critically on the edge value of q, exhibiting almost the same kink-like mode structure—except close to the separatrix, where the displacement changes sign—that is typical of a tearing-like mode. Notably, a peeling/tearing mode with a lower growth rate can be discussed only in a theoretical framework, so it is likely to be invisible when other stabilizing effects are considered. On the other hand, it seems self-evident that ideal MHD current-driven modes—including the peeling mode (Ref.71 and therein)—are strongly stabilized in a plasma with an X-point at the divertor configuration that depends on the position of the plasma boundary (i.e., the last closed-flux surface, LCFS) defined by each calculation.

Comparison with previous observations at various Tokamaks around the world

Our understanding of these plasma phenomena can be refined by comparing this observation with examinations of ELM precursors in various tokamaks that use a Mirnov coil, ECE radiometry, and reflectometer diagnostics, as well as SX cameras.

Precursor mode numbers cover the wide range from n = 1–13 on JET50. Precursors with the low values n = 1–3 have been observed regularly in so-called hot-ion H-mode discharges72and they are also observed in some conventional ELMy H-mode discharges. Such hot-ion H-modes are characterized by very high ion temperatures, which are achieved by applying NBI heating to a low-density target. These experimental conditions seem to be similar to those in discharge E049217 in JT-60U presented here, with lower-n modes present up to the ELM onset, while there are similarities and differences between them for the MHD modes that systematically precede the ELMs. In hot-ion H-mode discharges, giant ELMs were generally preceded by so-called outer modes (OMs)73although these have not been explicitly labeled as precursors. The low mode numbers (mostly n = 1–2) and frequencies (f ∼ 5–15 kHz) seen in the OMs are similar to those seen in discharge E049217 on JT-60U. On the other hand, OMs can be very long-lived, occasionally existing for up to hundreds of milliseconds, while the precursors seen in discharge E049217 on JT-60U exist for at most a few milliseconds or less (and the growth rate accelerates rapidly prior to the ELM and acts as its trigger). Furthermore, OMs have been identified as low-n external kink-parity modes74while the precursors seen in discharge E049217 on JT-60U have a tearing-parity with m/n = 4/1 at q = 4 in the middle of the pedestal.

Furthermore, on JET, the precursor oscillations that were found prior to Type-I ELMs in general (not restricted to giant ones) showed no phase inversions between channels in the ECE diagnostic, in contrast to that seen at JT-60U. This confirms that the mode has a kink-like radial structure (i.e., twisting parity) and is not a magnetic island; hence, tearing modes must be excluded for JET due to the absence of radial phase inversions. The presence of a lower-n mode is also ubiquitous not only in observations of the ELMs in large tokamaks with lower collisionality but also in small/medium-sized ones with higher collisionality, such as ASDEX46, COMPASS-D47, ASDEX-Upgrade48, TCV49,52, NSTX51, etc. Earlier work includes a report for ASDEX, which describes less of the underlying physics of the precursor, as well as a similar study on TCV, and a work examining ELMs, including a previous publication on ELM precursors at JT-60U45. Moreover, a study of ELM precursors in NSTX using gas-puff imaging suggests that the precursor plays some role in the ELM-crash, although it is difficult to illuminate the physical process by which the precursor participates in the crash, while the deformation of the edge is qualitatively like disturbances due to ballooning or peeling instabilities. Accordingly, this feature may indicate an instability driven by the edge pressure or edge currents.

However, an ELM event is a complicated nonlinear process likely involving the interaction of several physical processes, even in existing devices.

Additional observations about the turbulence near collapse

Regarding turbulence near the ELM onset, we observed incoherent broadband density fluctuations in the hundreds of kHz range in data obtained from the reflector system. The cutoff frequencies of these signals are 34 and 36 GHz, measured in the pedestal region where the tearing-parity mode in the tens of kHz range—identified in this study—was also observed. It is known that the density fluctuation signals, which suggest turbulence, grow during the precursor phase with a time constant similar to that of the tearing-parity mode. However, evaluating the influence of turbulence is not straightforward with the current analysis. Therefore, we believe that a more detailed analysis should be conducted in future studies. In particular, if the direct coupling between turbulence and global perturbation is neglected (as the simplest approximation for the first step), then the contribution of turbulence to magnetic stochasticity becomes additive. This could have an additional correction that could lower the threshold for stochastic onset compared with predictions from static models.

Analysis of the magnetics

To validate the experimental identification of the m = 4 poloidal-mode structure, we evaluated the expected amplitude distribution of the magnetic perturbations in the radial (\(\:{B}_{r,wall}^{Cal.}\)) and poloidal (\(\:{B}_{\theta\:,wall}^{Cal.}\)) directions. We performed these calculations by employing a set of finite current filaments with phase differences δφ = π radians along the magnetic-equilibrium field on the q = 4 surface. This configuration ensures that the total plasma current does not increase or decrease under a given magnetic equilibrium. As shown in Fig. 8, we carried out this evaluation at the ELM onset in a realistic magnetic geometry that included an elongated cross-sectional shape with an X-point. In this analysis, we applied a numerical filter with n = 1 to \(\:{B}_{r,wall}^{Cal.}\) and \(\:{B}_{\theta\:,wall}^{Cal.}\), which generated a sheet-like current on the q = 4 surface while reducing the higher-order harmonics observed at n = 2, 3, 4,\(\:\cdots\:\). To compare the experimental results with the calculated results, (i) we adjusted the starting toroidal angle for the current filament on the q = 4 surface to match the measured radial magnetic perturbation for the dominant n = 1 component along the toroidal angle on the midplane of the low-field side (LFS), as shown in Fig. 8(c). We fitted the mode structure calculated for the n = 1 mode to the experimental data using their normalized values (i.e., relative amplitudes). (ii) After determining the starting toroidal angle for the current filament on the q = 4 surface, we compared the measured and calculated amplitudes of the magnetic perturbations for the poloidal component along the poloidal angle at the measured toroidal angle (i.e., φ = 288°), as shown in Fig. 8(d). (iii) We determined the absolute value of the filament current for the modeled m/n = 4/1 mode at the q = 4 surface by comparing the calculated and measured values at the poloidal array. At these points, we corrected for the damping in the poloidal magnetic perturbations, \(\:\delta\:{B}_{\theta\:}\), measured at the conducting wall by multiplying the measured value by a factor of ~ 2 (depending on the location of the detectors relative to the q = 4 surface); i.e., \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{\theta\:,\:wall}^{Mes.}\:=\:\frac{2}{1\:+\:{\left(\frac{{r}_{s}}{b}\right)}^{2m}}\delta\:{B}_{\theta\:}\)75. Here, rs and b represent the minor radius of the q = 4 surface and of the detector, respectively, and we obtained the value of \(\:{\delta\:B}_{\theta\:}\) by integrating the measured values of \(\:{dB}_{\theta\:}/dt\) starting at \(\:{{\Delta\:}t}_{ELM}\:=\:\)−22 µs. The corresponding amplitude of the radial-field perturbation at q = 4 due to the magnetic island can also be calculated using the absolute value of an identified current filament (\(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{n}^{q\:=\:4}\propto\:{I}_{filament}^{0.5}\)), and it is consistent with the value estimated using a cylindrical approximation: \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{n}^{q\:=\:4}\cong\:{\left(\frac{b}{{r}_{s}}\right)}^{m\:+\:1}{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{\theta\:,\:wall}^{Mes.}\)76. The experimental observation of the poloidal-mode structure at the ELM onset agrees well with that calculated using Ifilament ~ 380 ± 70 A and \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{n}^{q\:=\:4}\) = 8.0 ± 1.5 Gauss. One of the four magnetic islands (O-points) on the q = 4 surface exists at the midplane on the LFS (χ = 0°), while the other three exist at the high-field side (HFS; χ = 180° and ±90°), as shown in Fig. 8(e), which is an example of a Poincaré plot with a filament current of 400 A.

Estimating the timescale of the explosion

Here, we provide a concise summary of the explosive-growth hypothesis53. If the current diffusivity is significant, Ohm’s law can be expressed as\(\:\:E\:+\:V\:\times\:\:B\:=\:\eta\:j-\lambda\:{\nabla\:}^{2}j\), where λ is the current resistivity (the classical resistivity η is not considered in the following arguments.). Reference 56 has derived the nonlinear evolution of the width of the magnetic island in the Rutherford regime. By rewriting Eq. (7) of Ref. 56 for the island width in terms of the normalized magnetic-perturbation amplitude, \(\:{B}_{n}\:=\:R{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{r}/{r}_{s}{B}_{\varphi\:0}\) (where R is the major radius, rs is the minor radius at the q = 4 rational surface, and \(\:{B}_{\varphi\:0}\) is the toroidal magnetic-field strength), we obtain

where the numerical coefficient for the case m = 4 is C3/2 = 77, the magnetic shear parameter s is O(1), \(\:{\mu\:}_{0}\) is the vacuum magnetic permeability, and \(\:{\varDelta\:}^{{\prime\:}}\) is the tearing mode index. Once magnetic braiding occurs, the current diffusivity λ is controlled by the magnetic perturbation. This has been evaluated in the quasilinear limit as

where \(\:{v}_{A}\) is the Alfvén velocity, and \(\:{{\Gamma\:}}_{0}\:=\:{\pi\:}^{3/2}{\left(\frac{c}{{\omega\:}_{p}{r}_{s}}\right)}^{2}{v}_{e}/{v}_{A}\) (where \(\:{\omega\:}_{p}\) is the plasma frequency, and \(\:{v}_{e}\) is the thermal velocity of the electrons). To estimate the timescale of rapid reconnection after the triggering—which is defined by the onset of magnetic braiding—we solve the time evolution of the magnetic perturbation Bn, keeping all other parameters constant. Combining equations (a1) and (a2) yields an explosive increase in the magnetic perturbation, as follows:

In Eq. (a3), the time t = 0 represents the onset of magnetic braiding, and \(\:{B}_{n0}\) is the normalized amplitude \(\:{B}_{n}\:=\:R{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{r}/r{B}_{\varphi\:0}\) at t = 0. In Eq.(a3) the rate coefficient is \(\:\gamma\:\:={\left(Cs\right)}^{3/2}{{\Gamma\:}}_{0}{\varDelta\:}^{{\prime\:}}{r}_{s}{\tau\:}_{A}^{-1}/2\). The time τbraid at which the explosion occurs is given by the vanishing of the denominator. This is the same as the time t = τbraid, which thus represents an order-of-magnitude estimate for the time elapsed after the trigger at which the large-scale collapse occurs. It is given by \(\:1/\left(\sqrt{{B}_{n0}}\gamma\:\right)\); i.e.,

In the present case, the parameters are Bn0−1/2 ~ 30, Γ0 ~ 10−5, (Δ’rs) ~ 100, and R/vA ~ 0.2 µs. Consequently, Eq.(a4) yields the estimate τbraid ~ 80 µs.

A coordinate system based on straight field lines

The Poincaré plot mapped in the R–Z-plane [Fig. 8(e)] can be understood using a coordinate system based on straight field lines77where the poloidal angle χ is defined by \(\:\chi\:\left(l\right)\:=\:2\pi\:{\int\:}_{{l}_{0}}^{l}\left[1/\left({r}^{2}{B}_{\theta\:}\right)\right]dl/\oint\:\left[1/\left({r}^{2}{B}_{\theta\:}\right)\right]dl\), where \(\:dl\) is the poloidal component of the vector element of a magnetic-fieldline. Given the value of \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{n}^{q\:=\:4}\), the radial width of the magnetic island (i.e., the distance between the separatrices on either side of the O-point, normalized by the minor radius of the plasma, \(\:{a}_{LCFS}\) = 0.94 m) can be computed using a cylindrical approximation78; \(\:{w}_{mag}^{Cylinder}\:=\:4{\left(\frac{{r}_{s}\:q\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{n}^{q\:=\:4}\:}{m\:{q}^{{\prime\:}}\:{B}_{\theta\:}}\right)}^{0.5}\), where \(\:{q}^{{\prime\:}}\:=\:\frac{\partial\:q}{\partial\:r}\), and all quantities are to be evaluated at the radius \(\:{r}_{s}\) of the surface q = 4. In this way, we evaluated the normalized radial width of the magnetic island at the ELM onset to be \(\:{w}_{mag}^{Cylinder}\) = 0.068 ± 0.006, which is only slightly larger than that estimated using the Poincaré plot: \(\:{w}_{mag}^{Poincare^{\prime}}\) = 0.060 ± 0.002.

Model for the stochastization of magnetic field

In a toroidal system, when a mode with a given poloidal mode number m appears, sideband modes with m ± 1 generally also emerge. Consequently, magnetic islands can be observed not only on the q = 4 surface but also on the q = 3 and q = 5 surfaces. As reported in a previous study57overlapping of magnetic islands between the m = 4 mode and the m = 3 (and/or m = 5) mode can occur. In addition, theoretical studies have revealed a mechanism in which a single island creates a secondary island through nonlinear effects, leading to overlap among these secondary islands58. When applying the stochastization model—originally discussed for the plasma core region—to the pedestal, it is difficult to determine which of these mechanisms is operational based on the current experimental observations. Nevertheless, in both scenarios, we presented semiquantitative evidence for the stochastization threshold using the island amplitude, which plays a critical role in the process. To develop this discussion, we focused on the width of a single island and the magnetic field strength. We expect that future comparisons with nonlinear simulations68 will be key to resolve this issue.

Generalizability and statistical robustness of conclusions

Regarding the generalizability of the findings presented in herein (i.e., the manifestation of the lower-n tearing-parity mode as the trigger mechanism of Type-I ELMs), similar lower-n MHD modes are found to be almost universally observed at the ELM onset in other discharges in JT-60U. For example, even when the external torque input is changed from co- to balanced or counter-NBI (even if the ELM size is changed) under the same experimental operating conditions (same Ip/BT and same plasma cross-sectional shape) and the same q95 value as discharge E049217, the lower-n MHD mode is still observed at the ELM onset. Hence, we have considerable confidence in the universality, including the reproducibility, of this characteristic lower-n MHD mode. Furthermore, even in the case of q95 = 3 or 5, which represent different experimental operating conditions from discharge E049217 (although the plasma cross-sectional shapes are slightly different due to differing Ip/BT combinations and a systematic comparison is not possible), it is known that, in the large-amplitude Type-I ELM region, MHD modes with similar lower-n are associated with the ELM onset on a similar timescale. However, in these cases, the ECE measurement position was not optimized in the pedestal due to the change in the magnetic field, making it difficult to identify the tearing parity and the poloidal mode number. In contrast, a statistical analysis of the threshold conditions and time scales related to the magnetic stochasticity that leads to the occurrence of ELMs has not yet been performed. However, as shown in this paper, the range of time constants for ELMs in six different cases in the same discharge has been statistically analyzed. Again, we are confident that this discharge (i.e., E049217) is not special and is a typical discharge in which Type-I ELMs appear, as far as macroscopic parameters are concerned (see Fig. 2(b)). From this point of view, we are confident about the universality of this characteristic lower-n MHD mode, including its reproducibility. Incidentally, no lower-n MHD modes have been observed in the operational region of Type-III ELMs, including precursor phenomena. However, this may also be due to the difficulty in detecting weak modes because of limitations in the S/N ratio of the measurements. As for how commonly a similar n = 1 mode is observed in other devices, as mentioned in the Methods section, subsection “Comparison with previous observations at various tokamaks around the world,” it will be necessary to reevaluate and retest the mode parity, as well as accurately identify the number of poloidal modes.

Data availability

Any relevant data are available from the authors upon reasonable request after proper procedure at the JT-60 Data Analysis Server (http://falcon.naka.qst.go.jp/index.html), and Kensaku Kamiya (one of the authors of this paper) can be contacted in order to access these data.

References

Shibata, K. & Magara, T. Solar flares: magnetohydrodynamic processes. Living Rev. Solar Phys. 8, 6 (2011).

Zhang, J., Cheng, X. & Ding, M. D. Observation of an evolving magnetic flux rope before and during a solar eruption. Nat. Commun. 3, 747 (2012).

Benz, A. O. Flare observations. Living Rev. Solar Phys. 14, 2 (2017).

Inoue, S. et al. Formation and dynamics of the solar eruptive flux tube. Nat. Commun. 9, 174 (2018).

Kusano, K. et al. A physics-based method that can predict imminent large solar flares. Science 369, 587–591 (2020).

Yan, X. et al. Fast plasmoid-mediated reconnection in a solar flare. Nat. Commun. 13, 640 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Solar flare effects in the earth’s magnetosphere. Nat. Phys. 17, 807–812 (2021).

Shimada, M. et al. Chapter 1: overview and summary. Nucl. Fusion. 47, S1–S17 (2007).

Hassanein, A. & Sizyuk, V. Potential design problems for the ITER fusion device. Sci. Rep. 11, 2069 (2021).

Tobita, K. et al. Conceptual design of japan’s fusion DEMO reactor (JADEMO) and superconducting coil issues. J. Phys. : Conf. Ser. 1293, 012078 (2019).

Barucca, L. et al. Pre-conceptual design of EU DEMO balance of plant systems: objectives and challenges. Fusion Eng. Des. 169, 112504 (2021).

Waldrop, M. Plasma physics: the fusion upstarts. Nature 511, 398–400 (2014).

Wesson, J. A. Hydromagnetic stability of the Tokamaks nucl. Fusion 18, 87 (1978).

Gombosi, T. I. et al. Extended MHD modeling of the steady solar Corona and the solar wind. Living Rev. Solar Phys. 15, 4 (2018).

Connor, J. W. Edge-localized modes-physics and theory. Plasma Phys. Control Fusion. 40, 531 (1998).

Wilson, H. R. et al. Ideal magnetohydrodynamic stability of the Tokamak high-confinement-mode edge region. Phys. Plasmas. 6, 1925 (1999).

Kirk, A. et al. Evolution of filament structures during edge-localized modes in the MAST Tokamak. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 185001 (2006).

Fundamenski, W., Naulin, V., Neukirch, T., Garcia, O. E. & Rasmussen, J. J. The relationship between ELM filaments and solar flares. Plasma Phys. Control Fusion. 49, R43–R86 (2007).

Kamiya, K. et al. Edge localized modes: recent experimental findings and related issues. Plasma Phys. Control Fusion. 49, S43–S62 (2007).

Park, H. K. Newly uncovered physics of MHD instabilities using a 2-D electron cyclotron emission imaging system in toroidal plasmas. Adv. Phys. X. 4, 1633956 (2019).

Herrmann, A. et al. Stationary and transient divertor heat flux profiles and extrapolation to ITER. J. Nucl. Mater. 313, 759–767 (2003).

Evans, T. E. et al. Edge stability and transport control with resonant magnetic perturbations in collisionless Tokamak plasmas. Nat. Phys. 2, 419–423 (2006).

Park, J. K. et al. 3D field phase-space control in Tokamak plasmas. Nat. Phys. 14, 1223–1228 (2018).

Ham, C., Kirk, A., Pamela, S. & Wilson, H. Filamentary plasma eruptions and their control on the route to fusion energy. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 159–167 (2020).

Wesson, J. A., Edwards, A. W. & Granetz, R. S. Spontaneous m = 1 instability in the JET Sawtooth collapse. Nucl. Fusion. 31, 111–116 (1991).

Itoh, S. I., Itoh, K., Zushi, H. & Fukuyama, A. Physics of collapse events in toroidal plasmas. Plasma Phys. Control Fusion. 40, 879–929 (1998).

Kikuchi, M. The large Tokamak JT-60: a history of the fight to achieve the Japanese fusion research mission. Eur. Phys. J. H. 43, 551–577 (2018).

Keilhacker, M. et al. The scientific success of JET. Nucl. Fusion. 41, 1925 (2001).

Hawryluk, R. J. Results from deuterium-tritium Tokamak confinement experiments. Rev. Mod. Phys. 70, 537 (1998).

Snyder, P. B. et al. Edge localized modes and the pedestal: a model based on the coupled peeling-ballooning modes. Phys. Plasmas. 9, 2037 (2002).

Wilson, H. R., Cowley, S. C., Kirk, A. & Snyder, P. B. Magneto-hydrodynamic stability of the H-mode transport barrier as a model for edge localized modes: an overview. Plasma Phys. Control Fusion. 48, A71 (2006).

Huysmans, G. T. A. & Czarny, O. MHD stability in X-point geometry: simulation of elms. Nucl. Fusion. 47, 659–666 (2007).

Snyder, P. B. et al. A first-principles predictive model of the pedestal height and width: development, testing and ITER optimization with the EPED model. Nucl. Fusion. 51, 103016 (2011).

Leonard, A. W. Edge-localized-modes in Tokamaks. Phys. Plasmas. 21, 090501 (2014).

Aiba, N. et al. Analysis of ELM stability with extended MHD models in JET, JT-60U, and future JT-60SA Tokamak plasmas. Plasma Phys. Control Fusion. 60, 014032 (2018).

Kleiner, A., Ferraro, N. M., Diallo, A. & Canal, G. P. Importance of resistivity on edge-localized mode onset in spherical Tokamaks. Nucl. Fusion. 61, 064002 (2021).

Kirk, A. et al. The Spatial structure of type-I elms at the midplane in ASDEX upgrade and a comparison with data from MAST. Plasma Phys. Control Fusion. 47, 995 (2005).

Kirk, A. et al. Comparison of the filament behaviour observed during type I elms in ASDEX upgrade and MAST. J. Phys. : Conf. Ser. 123, 012012 (2008).

Maingi, R. et al. H-mode pedestal, ELM and power threshold studies in NSTX. Nucl. Fusion. 45, 1066 (2005).

Eich, T. et al. Nonaxisymmetric energy deposition pattern on Asdex upgrade divertor target plates during type-I edge-localized modes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 195003 (2003).

Boedo, J. A. et al. ELM-induced plasma transport in the DIII-D SOL. J. Nucl. Mater. 337–339, 771 (2005).

Maqueda, R. J. & Maingi, R. NSTX team. Primary edge localized mode filament structure in the National spherical torus experiment. Phys. Plasmas. 16, 056117 (2009).

Wilson, H. R. & Cowley, S. C. Theory for explosive ideal magnetohydrodynamic instabilities in plasmas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 175006 (2004).

Oyama, N. et al. Characteristics and control of the type I edge localized mode in the JT-60U. Nucl. Fusion. 51, 033009 (2011).

ASDEX Team. The H-mode of ASDEX. Nucl; Fusion. 29, 1959 (1989).

Colton, A. L. et al. ELM studies on the COMPASS-D Tokamak. Plasma Phys. Control Fusion. 38, 1359–1365 (1996).

Kass, T., Günter, S., Maraschek, M., Suttrop, W. & Zohm, H. ASDEX upgrade team. Characteristics of type I and type III ELM precursors in the ASDEX upgrade. Nucl. Fusion. 38, 111 (1998).

Reimerdes, H., Pochelon, A. & Suttrop, W. Toroidally asymmetric ELM precursors in TCV. Nucl. Fusion. 38, 319 (1998).

Perez, C. P. et al. Type-I ELM precursor modes in the JET. Nucl. Fusion. 44, 609 (2004).

Sechrest, Y., Munsat, T., Battaglia, D. J. & Zweben, S. J. Two-dimensional characterization of ELM precursors in NSTX. Nucl. Fusion. 52, 123009 (2012).

Wenninger, R. P., Reimerdes, H., Sauter, O. & Zohm, H. Non-linear magnetic perturbations during edge-localized modes in TCV dominated by low n mode components. Nucl. Fusion. 53, 113004 (2013).

Itoh, K. & Kamiya, K. Why the ELM-control-coils are effective in suppressing type-I elms. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 93, 025001 (2024).

Schmidt, J. & Yoshikawa, S. Anomalous viscosity as a possible explanation for an anomalous plasma skin effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 26, 753 (1971).

Strauss, H. R. Hyper-resistivity produced by tearing mode turbulence. Phys. Fluids. 29, 3668 (1986).

Kaw, P. K., Valeo, E. J. & Rutherford, P. H. Tearing modes in a plasma with magnetic Braiding. Phys. Rev. Lett. 43, 1398 (1979).

Waddell, B., Carreras, B., Hicks, H. R., Holmes, J. A. & Lee, D. K. Mechanism for major disruptions in Tokamaks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 41, 1386 (1978).

Lichtenberg, A. J. Stochasticity as the mechanism for the disruptive phase of the m = 1 Tokamak oscillations. Nucl. Fusion. 24, 1277 (1984).

Diamond, P. H., Hazeltine, R. D., An, Z. G., Carreras, B. A. & Hicks, H. R. Theory of anomalous tearing mode growth and major Tokamak disruption. Phys. Fluids. 27, 1449 (1984).

Lichtenberg, A. J., Itoh, K., Itoh, S. I. & Fukuyama, A. The role of stochasticity in Sawtooth oscillations. Nucl. Fusion. 32, 495 (1992).

Itoh, K., Itoh, S. I., Fukuyama, A., Tsuji, S. & Lichtenberg, A. J. Model of the major disruption in Tokamaks. Nucl. Fusion. 32, 1851 (1992).

Snyder, P. B., Wilson, H. R. & Xu, X. Q. Progress in the peeling-ballooning model of edge localized modes: numerical studies of nonlinear dynamics. Phys. Plasmas. 12, 056115 (2005).

Xu, X. Q., Dudson, B., Snyder, P. B., Umansky, M. V. & Wilson, H. R. Nonlinear simulations of peeling-ballooning modes with anomalous electron viscosity and their role in edge localized mode crashes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 175005 (2010).

Krebs, I., Hölzl, M., Lackner, K. & Günter, S. Nonlinear excitation of low-n harmonics in reduced magnetohydrodynamic simulations of edge-localized modes. Phys. Plasmas. 20, 082506 (2013).

Bécoulet, M. et al. Mechanism of edge localized mode mitigation by resonant magnetic perturbations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 115001 (2014).

Kim, M. et al. BOUT + + nonlinear simulation for a comparative study with the measured 2D ELM structures in the KSTAR H-mode plasma. Phys. Plasmas. 26, 052502 (2019).

Cathey, A. et al. Non-linear extended MHD simulations of type-I edge localized mode cycles in ASDEX upgrade and their underlying triggering mechanism. Nucl. Fusion. 60, 124007 (2020).

Seto, H., Xu, X. Q., Dudson, B. D. & Yagi, M. Two-stage crash process in resistive drift ballooning mode driven ELM crash. Phys. Plasmas. 31, 032513 (2024).

Connor, J. W., Hastie, R. J., Marchetto, C. & Roach, C. M. A one-dimensional tearing mode equation for pedestal stability studies in Tokamaks. J. Plasma Phys. 84, 725840301 (2018).

Tanabe, H. et al. Electron and ion heating characteristics during magnetic reconnection in the MAST spherical Tokamak. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 215004 (2015).

Kamiya, K. et al. Unveiling the structure and dynamics of the peeling mode in quiescent high-confinement Tokamak plasmas. Commun. Phys. 4, 141 (2021).

The JET Team (presented by Jones, T. T. C.). The route to high performance on the JET. Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 37, A359. (1995).

Nave, M. F. F. et al. An overview of MHD activity at the termination of JET hot ion H modes. Nucl. Fusion. 37, 809 (1997).

Huysmans, G. T. A. et al. Identification of the external kink modes in JET. Nucl. Fusion. 38, 179 (1998).

Takechi, M., Toi, K. & CHS Group. Movable magnetic probe array for the toroidal Alfven eigenmodes study in the compact helical system heliotron/torsatron. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 70, 442–444 (1999).

Buttery, R. J. et al. Contributors to the EFDA-JET work program. Onset of neoclassical tearing modes on the JET. Nucl. Fusion. 43, 69 (2003).

Matsunaga, G. et al. In-vessel coils for magnetic error field correction in JT-60SA. Fusion Eng. Des. 98, 1113–1117 (2015).

Fitzpatrick, R. Interaction of tearing modes with external structures in cylindrical geometry (plasma). Nucl. Fusion. 33, 1049 (1993).

Acknowledgements

The authors express sincere gratitude to the entire JT-60 team for their continued research and operational efforts. The authors also acknowledge the support by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (JP24K06997, JP21K03513, JP20K03913) and collaboration initiatives between QST and Chubu University. The authors wish to dedicate this article to the memory of the late Prof. Sanae-I. Itoh.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.K analyzed the experimental data. K.I discussed the data based on theoretical insight. G. M developed the model for the magnetic perturbation. N.A analyzed the MHD stability. K.K, G. M., A.I. and N.O discussed the accuracy of the diagnostics for fluctuation measurements and the physics associated with these diagnostics. K.K and K.I wrote the manuscript, and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kamiya, K., Itoh, K., Matsunaga, G. et al. Identification of a magnetohydrodynamic trigger for plasma explosions in magnetic fusion beyond existing paradigms. Sci Rep 15, 30958 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16713-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16713-y