Abstract

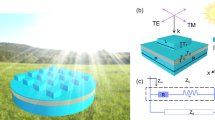

This research focuses on the design of broadband, polarization-insensitive absorber layers based on all-dielectric metasurfaces for use across the entire visible light spectrum, i.e., 400–800 nm, for applications in solar cells and photovoltaic devices. The patterned metasurfaces utilize InAs nanorods with two different radii and heights, whose size diversity generates optical resonances at diverse wavelengths and increases the absorption bandwidth. The nanorods are based on a substrate of the same material, which is, in turn, backed by a SiO2 layer. Two absorbers are designed for different purposes, utilizing an accurate and efficient artificial neural network (ANN) model. The first absorber exhibits an extremely high average absorption of 99.5% under normal incidence. The second structure provides the highest angular stability by maintaining high absorption above 90% up to an angle of 70o for both transverse electric (TE) and transverse magnetic (TM) polarizations. Parametric analysis shows that the performance of the designed absorbers is robust to fabrication tolerances. The ANN-predicted results are verified by analytical approaches based on the electric polarizabilities of the nanorods. Compared to previous plasmonic and dielectric-based counterparts, the proposed absorbers exhibit superior performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Light absorption is of great importance in photodetector devices1,2, solar cells3,4, sensors5,6, optical modulators7, and photovoltaic devices8. To date, absorbing layers have been fabricated based on various physical mechanisms. Narrowband absorbers have wide applications in sensors and modulators, while broadband absorbers are mostly used in solar cells and photovoltaic devices8. In various studies, different types of metamaterial and metasurface-based absorbers have been investigated. Metamaterials are engineered artificial structures with electrically small unit cells designed to achieve exotic electromagnetic properties. Metasurfaces are the two-dimensional version of metamaterials9. Metamaterials are classified into two categories: metal-based and dielectric-based10.

Plasmonic absorbers achieve light absorption in a metal-insulator-metal sandwich structure exploiting surface plasmon resonance (SPR)11. In12 a resonator-based sun shape metasurface absorber is proposed at the wavelength range 390–760 nm, incorporating the layers W-SiO2-W, with an average absorption rate of 96.43% and a peak absorption of 99.99% at 523.22 nm. Authors in13 introduce a metamaterial three-layer absorber composed of Manganese and Silica. With a total thickness of 190 nm, the absorber achieves an absorptance of about 94% across the visible spectrum and maintains an average absorption of 98.72%. The absorber presented in14 consists of a Ti top layer resonator, a silicon dioxide (SiO2) dielectric spacer, and a Ti bottom reflector. It exhibits an average absorption coefficient of 98.11% across the visible range. In15 a thin polarization-independent absorber is presented featuring a semiconductor nanoring array atop a uniform gold substrate, with an average absorption rate about 90% over the wavelength range 300–740 nm. A broadband absorber has been developed in16 using a thin metal-insulator-metal stack, featuring cross-shaped titanium resonators, a silica dielectric spacer, and an opaque titanium layer. It achieves over 90% absorption across the bandwidth of up to 2100 nm, spanning from the visible to the near-infrared spectrum.

A category of absorbers exhibits broadband absorption using multi-layer stacks. In17 a metamaterial absorber, which consists of a periodic arrangement of metallic-dielectric multilayered conical frustums, is reported, with an average absorption of about 90%, covering the visible and near-infrared spectrum 480–1480 nm. The absorptivity is maintained up to the incident angle 60°. Authors in18 developed a wideband absorber with absorption rate of about 90% across the visible light and near-infrared spectrum (405–1505 nm). It facilitates the simultaneous excitation of propagating surface plasmon resonance, local surface plasmon resonance, and Fabry-Perot cavity resonance. An average absorptivity of 95.14% within 405–1505 nm under normal incidence is obtained. In19, authors present an ultra-broadband metamaterial absorber based on photonic topological transition through metals with a significant real part of permittivity. The absorption rate exceeds 0.9 across 400–2832 nm.

The use of metal-based metamaterials in the visible and near-infrared ranges causes thermal losses. Therefore, researchers have turned to replacing metal with all-dielectric metamaterials, except possibly for a thin metal layer beneath the structure as a mirror20. In21, a broadband metamaterial absorber is proposed within the visible and near-infrared spectrum, comprising array of Ge2Sb2Te5 square resonators and a planar cavity. Its performance is attributed to the excitation of plasmon-like dipolar or quadrupole resonances from Ge2Sb2Te5 resonators, and the resonances produced by the cavity. In22 a subwavelength broadband thin metasurface absorber utilizing diamond Si arrays is proposed, with an absorption rate of about 90% for the near-ultraviolet to the visible spectrum, and an average absorption rate of 93.3% for the visible range. In23 an ultra-broadband and wide-angle GaAs absorber is reported within the visible and near-infrared spectra. An absorption exceeding 90% is attainable across the range of 0.39 μm to 2.09 μm, yielding a relative bandwidth of 137.1%. Authors in24 present a metamaterial absorber utilizing a GaAs pyramid nanostructure, capable of operating across the entire solar radiation spectrum. Its absorbance surpasses 85% throughout the full solar spectrum. In7 low-footprint nonmetallic broadband absorbers for visible light are proposed, utilizing alternating SiO2/InAs thin films on a SiO2 substrate, with an average absorption rate of 97% across 300–850 nm. In25 a flexible absorber is developed with an average absorbance of 97.4% across the visible light spectrum with an angular stability up to 50°. The broad absorption effect is attributed to a single broadband resonance in the highly lossy Fabry–Perot cavity. Authors in26 have developed a wideband absorber using nanopillar Mie resonators, leveraging the concept of degenerate critical coupling. This 1300 nm-thick absorber achieves an average absorptivity of over 94% across 300–1000 nm.

When designing metasurface absorbers, it is conventional to adjust geometric parameters based on time-consuming exhaustive search procedures to determine the optimal values. This is because the electromagnetic wave absorption in metasurfaces usually depends on complicated scattering patterns arising from several electric and magnetic multipoles which hardly give an insight to design such structures at optical frequencies11. It is well known that artificial neural networks (ANNs) have the ability to identify and model complex patterns in data. This tool can perform much better in nonlinear and multidimensional problems compared to empirical methods27. ANNs consist of a set of neurons located in different layers and connected to each other through weights and activation functions. The structure under test allows ANNs to learn complex relationships between inputs and outputs. Learning in ANNs is usually performed through the backpropagation algorithm using training data. Accordingly, the network’s prediction error is calculated with the actual output, and the weights are updated in such a way that the error is reduced27. ANNs are particularly successful in problems with a large number of independent and dependent variables, such as in this research.

In this paper, two broadband absorbers based on all-dielectric metasurfaces are designed at the visible range. The metasurfaces utilize simple InAs nanorods with two different radii and heights, which are used to create optical resonances at different wavelengths and increase the absorption bandwidth. In28, we optimized the control parameters of the absorber under normal incidence using an exhaustive search procedure, under some constraints. But in this paper, all the constraints are removed and the independent control parameters are optimized using the powerful and efficient ANN tool. Due to independence of the control parameters, conventional exhaustive searching tools are prohibitive and demand huge resources. Two types of absorbers are proposed in this work: (a) A near-perfect absorber for normal incidence purposes with an extremely high average absorption rate of 99.5%, and (b) A wide-angle absorber with an average absorption higher than 90% for the incidence angles up to 70o.

ANN-assisted design of absorbers

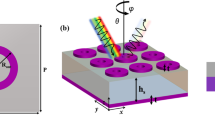

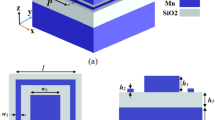

The proposed design for the absorbing metasurface is to use nanorods with two different radii and heights. Figure 1 shows the structure of the absorber. In this figure, \(\:{h}_{1}\) represents the thickness of the SiO2 layer, \(\:{h}_{2}\) the thickness of the InAs layer, \(\:{d}_{1}\) the height of the small-sized rods, \(\:{d}_{2}\) the height of the large-sized rods, and \(\:{r}_{1}\) and \(\:{r}_{2}\) represent the radii of the small-sized and large-sized rods, respectively. \(\:P\) represents the total period of the unit cell, and \(\:{P}_{1}\) and \(\:{P}_{2}\) represent the period of the nanorods. The absorbing layer is made of InAs. This material is a III-V group semiconductor that is used in many optoelectronic applications due to its unique optical and electronic properties, such as strong visible light absorption, high-temperature stability, compatibility with large-scale integration, and developed fabrication processes. SiO₂, or silica glass, is used as the substrate. It has high stability and is also transparent over a wide range of wavelengths which does not negatively affect the optical performance of the structure. The use of SiO₂ as a substrate is compatible with semiconductor fabrication processes and allows for mass production29.

The use of top-down etching methods based on electron beam lithography (EBL) and plasma dry etching (RIE or ICP-RIE) has recently been recognized as one of the main methods for fabricating vertical nanorods with high precision and control. In numerous articles, the success of this method in fabricating nanorods with dimensions very close to or even exactly matching our proposed structure has been reported. For example, III-V nanorods with a diameter of about 50 nm and a height of about 660 to 910 nm were uniformly fabricated on a silicon substrate30. Also, authors in31 successfully created arrays of GaAs nanorods with diameters of 30 to 400 nm and a height of more than 2 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) using EBL and plasma etching. These results indicate that the fabrication of nanorods with a diameter of about 50–65 nm, similar to our proposed structure, is feasible with current technologies in research and industrial centers.

For the fabrication of the designed metasurface structure, which includes InAs nanorods with two different radii and heights, a top-down approach based on electron lithography and dry etching is proposed, as it offers high precision and compatibility with common nanotechnology equipment. The substrate consists of a SiO2 wafer on which an InAs layer with a thickness of about 1.62 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) is grown by metal-organic vapor phase epitaxy (MOVPE) on the SiO2 substrate. This layer defines the maximum height of the nanorods and provides a single-crystal base for nanostructure patterning. In the next step, using EBL and a negative resist such as HSQ, the locations of the longer nanorods (with a radius of about 62 nm) are patterned (steps 4 and 5 in Fig. 2). Then, the RIE dry etching process is performed to a depth of 85 nm, which is equal to the height difference between the two types of nanorods. In the second step, a new layer of HSQ is placed on the structure, and with a second electron lithography, the areas corresponding to the shorter nanorods (with a radius of about 50 nm) are defined (steps 7 and 8 in Fig. 2). Subsequently, a second dry etch is performed to a depth of about 77 nm. As a result, the long nanorods are completed with a total etch depth of about 162 nm, and the short nanorods are formed with a height of about 77 nm. Finally, in step 11, the excess resists are removed, and the final structure appears30,31.

The absorption is simulated by the utility of Ansys Lumerical FDTD commercial package version 2023 R1 which is based on the finite difference time domain (FDTD) method. By computing the reflectance (\(\:R\)), the absorption is calculated using the relation \(\:A\:=\:1-R\). Note that the transmittance is zero since the resonance in between the nanorods traps the light and does not let it reach the SiO2 backing layer. Periodic boundary conditions are applied in the \(\:x\) and \(\:y\) directions, and Perfectly Matched layer (PML) boundary conditions are applied in the \(\:z\) direction to absorb scattered light. A plane wave source is applied towards the structure. The angle of incidence is defined as the angle between the incident wave vector and the normal to the \(\:xy\) plane. The initial polarization of the electromagnetic wave is defined as transverse magnetic (TM) with \(\:\varphi\:\:=\:0\), where \(\:\varphi\:\) is the angle of polarization of the radiation. As \(\:\varphi\:\) increases from \(\:{0}^{o}\) to \(\:9{0}^{o}\), the TM wave transforms into a transverse electric (TE) wave27.

The structure periods (\(\:{P}_{1}\), \(\:{P}_{2}\) and \(\:P\)) are determined based on lateral size constraints. Optimal values for the layers’ thicknesses (\(\:{h}_{1}\) and \(\:{h}_{2}\)) are found manually, due to their independence and lack of complex relationships, so as to maximize absorption for the corresponding bulk media. But the heights and radii of the rods have a complex relationship, making it impossible to manually find their optimal values for the highest average absorption. For this reason, a dataset is generated for the four parameters \(\:{r}_{1}\), \(\:{r}_{2}\), \(\:{d}_{1}\), and \(\:{d}_{2}\), and the optimization is performed using a neural network.

Initially, a dataset for normal incidence is created. This dataset includes 2160 data points for four control parameters. The absorption spectrum for the dataset is calculated using the FDTD method. The output for each data point is an absorption spectrum in the wavelength range of 400 to 800 nm. To find the highest absorption across the entire wavelength range, the criterion is set as the average absorption. As a result, the output for each data point in the datasets is the average absorption, which will be a number between 0 and 1. After generating the normal incidence data, data for oblique incidence is also generated based on the normal incidence dataset. Data points with an average absorption higher than 0.9 are selected, and then absorption spectra are calculated for the incident angles 10o, 20o, 30o, 40o, 50o, and 60o. The number of data points with an average absorption higher than 0.9 is 835.

In this paper we aim to find a broadband and wide-angle structure. This means that this structure should have a near-perfect average absorption and also be able to maintain its high absorption up to very oblique angles. In research conducted in this field, it is common to consider absorption above 0.9 as the criterion for oblique incidence across the entire wavelength range. For this purpose, we have proposed two structures with different radii and heights. The first structure actually has the highest average absorption at normal incidence, and the second structure is able to maintain its absorption stability up to an angle of 70o.

To predict the highest absorption in the optical absorber system, the Neural Network Fitting program in MATLAB software is used. Initially, a set of input data including \(\:{r}_{1}\), \(\:{r}_{2}\), \(\:{d}_{1}\), and \(\:{d}_{2}\), as well as the system output which is the average absorption as the objective function, are fed into the ANN model. Therefore, the absorber design problem could be interpreted as a nonlinear optimization problem with boxed constraints, imposing physical bounds on \(\:{r}_{1}\), \(\:{r}_{2}\), \(\:{d}_{1}\), and \(\:{d}_{2}\). The total number of input data is 2165. After training and optimization, the model is able to predict the system’s absorption value under different input conditions. Then sequential quadratic programming (SQP) algorithm is utilized to exploit these predictions to find the optimal values for the radius and height corresponding to the highest average absorption (ideal average absorption equals to 1). The SQP algorithm is one of the most advanced and powerful methods for solving nonlinear optimization problems. This method is suitable for problems that involve nonlinear objective functions, nonlinear constraints, and also linear constraints32. Many standard optimization methods (like gradient descent or Nelder-Mead) struggle or require transformation tricks to handle nonlinear constraints. SQP methods typically have quadratic convergence, meaning they converge faster than gradient-based methods like steepest descent or Newton’s method, especially near the optimum. In addition, SQP constructs and solves a quadratic approximation of the Lagrangian at each iteration, giving a more accurate local model of the objective and constraints. Unlike evolutionary or heuristic algorithms (e.g. genetic algorithms, particle swarm), SQP is deterministic and typically requires fewer iterations for convergence. Finally, it incorporates constraints directly into its optimization process, ensuring feasible steps are taken at every iteration, reducing the risk of violating physical or design boundaries32.

Results and discussion

In this section, the results of optimizing structural parameters to achieve the highest light absorption for the following absorbers are presented and analyzed: (a) A near-perfect absorber for normal incidence purposes with an extremely high average absorption rate of 99.5%, and (b) A wide-angle absorber with an average absorption higher than 90% for the incidence angles up to 70o. The goal is to adjust the structural parameters such that the average light absorption approaches the maximum possible value. Figure 3 depicts the flowcharts of the steps to design the two absorbers. The steps are explained hereinafter. The Bayesian regularization algorithm is used to train the model. This algorithm helps the ANN learn effectively from the data and prevent overfitting. The input layer of the ANN includes 4 features for the control parameters \(\:{r}_{1}\), \(\:{r}_{2}\), \(\:{d}_{1}\), and \(\:{d}_{2}\), and uses 40 neurons in the hidden layer. The physical constraints and sampling steps for the inputs are considered as \(\:5\text{n}\text{m}\le\:{r}_{1}\le\:50\text{n}\text{m}\) (step: 9 nm), \(\:10\text{n}\text{m}\le\:{r}_{2}\le\:100\text{n}\text{m}\) (step: 10 nm), \(\:30\text{n}\text{m}\le\:{d}_{1}\le\:130\text{n}\text{m}\) (step: 20 nm), and \(\:30\text{n}\text{m}\le\:{d}_{2}\le\:130\text{n}\text{m}\) (step: 20 nm). The output layer includes one feature which is the average absorption. The data are randomly divided into training and test sets. 70% of the data are allocated to training and 30% of the data are allocated to testing.

Near-perfect absorber for normal incidence

Figure 4 shows the regression, error residuals and error histogram plots for normal incidence. In Fig. 4a the data points are uniformly distributed and closely fitted to the line, indicating the ANN’s ability to match the target data. A slope of unity and a y-intercept close to zero indicate very accurate predictions by the ANN in this case. In the scatter plot shown in Fig. 4b, the blue dots represent the error residuals in term of true data, the black dashed line denotes the zero residual, and the \(\:\pm\:\sigma\:\) red lines denote where the residuals equal to the standard deviation of the trained network. Standard deviation is a measure of the uncertainty of the model. Most data fall within the standard deviation range, which shows high precision of the network. No particular pattern is seen in the residuals (random scatter), indicating the absence of systematic bias. In the error distribution histogram bar plot in Fig. 4c the prediction error (blue bars), average error (red line), and standard deviation of the errors (green dashed lines) are illustrated. The distribution of errors is approximately normal and symmetrical, indicating that the model’s errors are uniformly distributed around zero. The mean error is close to zero, so the model does not suffer from significant bias. Therefore, the network successfully models the optical absorption characteristics for normal incidence.

Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Regression Coefficient (\(\:{R}^{2}\)) are two common metrics for evaluating the performance of ANN prediction models. MSE indicates the degree of deviation of predicted values from actual values, and \(\:{R}^{2}\) is a metric that shows how well the model can explain the variations in the actual data. The value varies between 0 and 1, where a value close to 1 indicates a better model fit.

In (1), \(\:n\) is the number of samples, \(\:{y}_{i}\) is the actual value of the \(\:i\)-th sample, \(\:{\widehat{y}}_{i}\) is the value predicted by the model, and \(\:\stackrel{-}{y}\) is the average of the actual values. The very small MSE value reported in Table 1 indicates that the model has learned the nonlinear relationships between the input parameters \(\:{r}_{1}\), \(\:{r}_{2}\), \(\:{d}_{1}\), and \(\:{d}_{2}\), and the output (average light absorption) properly. The \(\:{R}^{2}\) value close to unity indicates that the model’s predictions are very accurate. Finally, the optimal structural values that resulted in the highest light absorption for the normal incidence are shown in Table 2.

The average light absorption predicted by the ANN is 0.9999. To verify the accuracy of the results, the absorption value is calculated using the FDTD method, wherein a result of 0.9950 is obtained. This high agreement between the simulation results and the ANN prediction indicates the high reliability and accuracy of the ANN. Figure 5a shows the calculated absorption spectrum for the optimized parameters shown in Table 2. It is evident that utilization of the metasurface structure results in a superior absorption performance, i.e. 99.50%, compared to the bare InAs, whose absorption is depicted in Fig. 5b with the average absorptance of 61.87%. In fact, the metasurface traps light by letting the nanorods resonate when the incident light impinges upon the absorber. Note that Fig. 5a and b are generated for TM incident polarization. However, in the proposed absorber the absorption spectra for the TE modes are almost the same as those for TM modes such that they are not distinguishable for normal incidence. This is a result of the near-symmetric structure of the unit cell. For bulk InAs, it is clear that the results are exactly the same for both polarizations since they could convert to each other by a rotation of the electric field by 90o. Sensitivity analysis of the designed absorber in terms of fabrication tolerances is given in Table 3. When a parameter is perturbed other parameters are kept fixed as in Table 2. Small variation of average absorption in terms of variations in the radii and heights of the nanorods denotes the robustness of the proposed absorber. Figure 6 shows the absorption spectra for TE and TM modes for the values in Table 2 at different angles of incidence. The absorption remains stable up to 50o, and its absorption is above 0.9 at all wavelengths. In addition, the structure turns out to be nearly insensitive to the incident polarization.

Figure 7 shows the transmission line model of the absorber. The electric and magnetic resonances of the nanorods should be represented by shunt electric admittance \(\:{Y}_{\text{e}\text{s}}\) and series magnetic impedance \(\:{Z}_{\text{m}\text{s}}\) in the circuit model33. Since the material used is InAs, being lossy at the wavelength range of interest, both \(\:{Y}_{\text{e}\text{s}}\) and \(\:{Z}_{\text{m}\text{s}}\) include a real part, in addition to the reactive imaginary part. The InAs of thickness \(\:{h}_{2}\) is modeled by a transmission line of electrical length \(\:{k}_{2}{h}_{2}\) and characteristic impedance \(\:{Z}_{2}={Z}_{0}/{n}_{\text{I}\text{n}\text{A}\text{s}}\), where \(\:{k}_{2}={n}_{\text{I}\text{n}\text{A}\text{s}}{k}_{0}\) is the propagation constant in InAs medium. In addition, \(\:{n}_{\text{I}\text{n}\text{A}\text{s}}\), \(\:{k}_{0}\) and \(\:{Z}_{0}\) are the refractive index of InAs, free space propagation constant, and free space intrinsic impedance, respectively. The SiO2 layer at the bottom of the absorber is modeled by transmission line of electrical length \(\:{k}_{1}{h}_{1}\) and characteristic impedance \(\:{Z}_{1}={Z}_{0}/{n}_{\text{S}\text{i}\text{l}\text{i}\text{c}\text{a}}\), where \(\:{k}_{1}={n}_{\text{s}\text{i}\text{l}\text{i}\text{c}\text{a}}{k}_{0}\) is the propagation constant in SiO2 medium and \(\:{n}_{\text{S}\text{i}\text{l}\text{i}\text{c}\text{a}}\) is the refractive index of silica. The transmission line is terminated by an open circuit load, since no light power reaches the back of the absorber. The absorptance of the absorber could be obtained from \(\:\text{A}=1-{\left|r\right|}^{2}\), where \(\:r\) is the reflection coefficient of the transmission line at the free-space/metasurface interface.

To make a comparison with analytical results, the concept of dielectric particle polarizability \(\:\alpha\:\) is utilized here. It is well known that the electric dipole \(\:p\) in a dielectric inclusion of electric permittivity \(\:\epsilon\:\) in a host medium of permittivity \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{0}\), i.e. air, induced by the incident electric field \(\:{E}^{\text{i}\text{n}\text{c}}\) is equal to34

wherein \(\:{E}^{\text{t}\text{o}\text{t}}\) is the total electric field at the dipole location. The integration is performed over the known quantity \(\:{E}^{\text{i}\text{n}\text{c}}\) inside the InAs nanorod volume \(\:V\). \(\:{E}^{\text{t}\text{o}\text{t}}\) should be calculated by averaging the simulated total electric field inside and around the nanorod over enough samples of electric field. In other words,

where \(\:{V}^{{\prime\:}}\) is the volume of a rectangular cube of side-length \(\:{P}_{1}\) for the small rods and \(\:{P}_{2}\) for the large rods (Fig. 1). Therefore, from (2) and (3) the electric polarizability could be numerically calculated as

To satisfy the perfect absorption condition, the Eq. 5 must govern the electric polarizability34,35

where \(\:\omega\:\) is the angular frequency, \(\:{R}_{0}={P}_{i}/1\text{.}438\) and \(\:{P}_{i}\) equals to \(\:{P}_{1}\) for the small rods and \(\:{P}_{2}\) for the large rods. To sum up, (4) and (5) yield numerical and analytical values for the electric polarizabilities. Figure 8 depicts these values (\(\:{\alpha\:}_{S}\) for small rods and \(\:{\alpha\:}_{L}\) for large rods), wherein analytical and numerical results show good agreement. Note that the incident and total electric fields are complex values, and thus the polarizabilities bear real and imaginary parts. The small discrepancy between the analytical and numerical results is due to the fact that (5) is exact only when the dielectric rods are infinitesimally small and only dipole modes are considered. However, the nanorods in the proposed absorber are not very small compared to the wavelength and thus higher order multipoles could be excited.

Wide-angle absorber

For oblique incidence, the ANN model includes four inputs and six outputs (corresponding to absorption at the incident angles 10o, 20o, 30o, 40o, 50o and 60o). In this case, Neural Network Fitting is also used because this tool provides multi-output modeling capability. In the wide-angle design process, an examination of the absorber’s behavior shows that as the angle of incidence increases, the absorption generally decreases. Therefore, by applying a larger weight to the 60o angle (the highest angle available in the dataset), an attempt was made to maximize absorption at this angle, thereby improving absorption at lower angles as well; because improving the response at the highest angle largely improves the structure’s behavior at intermediate angles. However, a closer examination of the results shows that this approach alone causes a drop in absorption at angles close to normal, such as the 10o angle. To make a balance between absorption at high and low angles, another weighting is assigned to the 10o angle to achieve an optimal balance across the angular range. Thus, prioritizing the 60o and 10o angles in the optimization process ensures that the absorber not only performs well at large angles but also exhibits balanced behavior across the entire angular range. As we will see in Fig. 9, interestingly the aforesaid optimization procedure yields an absorption above 0.9 even for the incident angle 70o, which is not included in the dataset. The goal of this optimization is to design an absorber that could ensure high optical absorption (above 0.9) across all wavelengths studied and at the most oblique angle possible. The proposed weighting scheme satisfies this objective. The ANN specifications are considered the same as in the previous subsection.

Figure 10 shows the regression, error residuals and error histogram plots for oblique incidence. In Fig. 10a the red line represents the fit line, indicating the linear relationship between the output and target values. The close proximity of the points to this line and a slope close to unity suggest that the network performs well in predicting optical absorption under oblique incidence. However, some points are more scattered from the fit line, which may indicate minor errors in learning. From the scatter plot in Fig. 10b, the majority of error residuals lie in between the standard deviation lines with a random pattern governing the residuals, showing an acceptable ANN performance with no systematic bias. In addition, from Fig. 10c, the prediction error bars in the histogram plot indicate an average error close to zero and an accumulation of errors within the standard deviation region. The deviation of the bar plots from the normal distribution is attributed to the highly nonlinear design procedure to satisfy acceptable absorption for a wide range of oblique incident angles. Due to the low number of data points for oblique incidence in this case, the MSE value, reported in Table 4, is larger than in the case of normal incidence, and consequently, the \(\:{R}^{2}\) value has also decreased. However, even with this model, we are able to obtain acceptable results in oblique incidence. The optimal structural parameters for the oblique incidence to yield the wide-angle design are shown in Table 5.

The FDTD results in Fig. 9a and b for TE and TM modes confirm that the designed structure can maintain light absorption above 0.9 up to an incidence angle of 70o. This indicates the structure’s excellent performance in maintaining absorption efficiency even at very oblique angles. Only at an angle of 80o does light absorption decrease below 0.9, which is due to the inherent limitations of the structure and strong light reflection at near-grazing angles. The insensitivity of the absorber to the incident polarization is evident, which denotes robustness against the changes in the light polarization. For comparison, Fig. 9c depicts the absorption at incident angles for the bare InAs. It exhibits much smaller absorption coefficients compared to when the metasurface is utilized. Due to the symmetry of the bare bulk structure, the absorption results are the same for both TE and TM polarizations, since they differ only by a 90o rotation of the electric and magnetic fields. In Fig. 9c, the absorbance increases monotonically with the incident angle at the wavelength range 440–490 nm. However, at the other spectral ranges depicted in the figure the monotonicity breaks down for the incident angles 70o and 80o, which is due to the appearance of the Brewster angle.

Compared to the first design, the stable wide-angle performance in the second design is achieved at the cost of a decrease in the absorbance over the spectral range. This is because in the first design, a near-perfect impedance matching is achieved between free space and the metasurface which lets the resonance modes strongly excited and localized around the nanorods. However, in the second design at large angles the horizontal component of the wavevector becomes significant and degrades the coupling of wave to the resonators. In other words, electric dipoles and possibly magnetic dipoles perpendicular to the dipoles pertaining to the vertical component of the wavevector arise, whose interference is partly destructive. In fact, impedance matching is harder to maintain across a wide angular range, so perfect absorption at all angles is not achievable with the same strength as in the single-angle-optimized design.

The sensitivity analysis in terms of the fabrication tolerances is given in Table 6. In most cases, the angular stability is maintained up to 70o, while in other cases the stability is observed up to 60o. Figure 11 shows the absorption spectrum for normal incidence with the values from Table 5. The absorption value for normal incidence when angular stability is prioritized is still above 90%, indicating that this structure can perform well in structures where both angular stability and normal incidence absorption are important. The periodic lattice of rods, i.e. 400 nm, creates optical diffraction modes and resonances at specific wavelengths, which has led to increased absorption across the entire visible range. The high absorption of the structure is due to the combination of two factors: (a) periodic supercells containing diverse resonant rods which provide high intensity spots of fields within the metasurface, and (b) high refractive index of InAs within the visible spectral range of interest, i.e. \(\:3.1\le\:n\le\:4.5\) which provides mode confinement36. These features result in light trapping, enhanced light-matter interaction, and reduced surface reflection.

In both designs, the broadband response is attributed to the high refractive index of the substrate and size diversity of utilized nanorods which excite multiple Mie-type electric and magnetic resonances at distinct wavelengths. The refractive index of InAs substrate within the visible band of operation is in between 3.1 and 4.5, which is relatively high36. For a substrate with high refractive index the electric and magnetic dipole resonance peaks become close to each other such that the former appears as a shoulder to the latter, resulting in spectral overlap and broadening of the resonance peaks. In this work, by exploiting two types of resonating rods the number of such adjacent broad peaks increases such that a nearly flat curve, i.e. broadband response, is observed in proximity of the resonance wavelengths37. The nanorods are designed such that the aforesaid broad resonance peaks occur within 400–800 nm band.

Discussion

Figures 12 and 13 show 2D absorption plots for polarization angles from 0o to 90o for the first structure (perfect absorber design at normal incidence) and the second structure (wide-angle design), respectively. The plots are drawn for normal incidence angle. They show that both structures are very nearly polarization-independent and can maintain their absorption at any polarization. The use of symmetrical nanostructures on the surface has helped the structure to have very low sensitivity to the polarization angle.

Figures 14 and 15 depict the distribution of the electric and magnetic fields above the first design under normal incidence. The observed field patterns indicate the symmetry and periodicity of the fields, which is due to the geometric and periodic structure of the InAs rods. The high electric field intensities indicate strong light absorption, which is due to the enhancement of resonance modes and strong light-matter interaction. In contrast, high magnetic field intensities denote a strong rotational change of the electric field. There is small electric field concentration inside the rods and they are mostly concentrated in the space between the rods. In fact, the rods with high dielectric constants form Fabry-Perot cavity resonators wherein the light is trapped inside the air medium. The electric dipoles (EDs) denoted by two spots of high electric field intensities, are formed in between several rods, as depicted in Fig. 14. At longer wavelengths, the EDs pertaining to small rods become more pronounced while those pertaining to large rods reduce in magnitude. In other words, at short wavelengths, the electric fields are concentrated around the large rods, while at longer wavelengths, the fields are confined in between the small rods. Therefore, the rods with large/small radii are effective in absorption at short/long wavelengths, respectively. At all investigated wavelengths an electric field null is observed at the middle symmetry planes of the large rods. In agreement with the variational theorem38, by increasing the wavelength the field concentration within the air medium becomes weaker and the interaction with dielectric rods gets stronger. From Fig. 15, at λ = 400 nm and λ = 509 nm a magnetic dipole (MD) and a magnetic quadrupole are created around the large rods, respectively, while at λ = 705 nm and λ = 800 nm, they overlap and make degenerate modes.

Figures 16 and 17 show the cross-sectional views of the electric and magnetic field distributions in a vertical slice of the structure. Strong electric field regions are formed at the edges and in between the rods, clarifying the trapping of light caused by multiple internal reflections in Fabry-Perot resonators. As the confinement time of light in the structure increases, the probability of photon absorption by the material increases. In a dielectric medium, a MD is formed by the displacement current, which is a result of an out of plane loop of the electric field37. As another interpretation, strong electric field intensities around the rods along with a null at the center of the rods indicate a MD. In the case of cylindrical rods, the height and/or diameter of the rods must be large enough so as to provide enough space inside the rod and to let retardation of the electric field, and thus forming an electric field loop. On the other hand, by increasing the dimensions of the rod, a larger portion of the displacement current is created inside the rod, resulting in an increase in the resonance wavelength37. This is in agreement with Fig. 16 wherein the MD appears inside the large rods at all wavelengths, while it appears inside the small rods only at larger wavelengths due to creation of a strong electric field between the small rods. At longer wavelengths smaller rods make a pronounced contribution to the resonance mechanism and at the same time, part of the field penetrates into the InAs substrate. From Fig. 17, the magnetic dipoles and quadrupoles are distinct at shorter wavelengths while they degenerate at longer wavelengths. In addition, in agreement with the variational theorem, at shorter/longer wavelengths the magnetic field concentrates mostly inside the air/dielectric media, respectively.

To be more specific on thermal stability, in InAs the thermal conductivity is ~ 27 W/m.K (at room temperature) and melting point is ~ 942 °C. For SiO2 these values amount to ~ 1.4 W/m.K and ~ 1713 °C, respectively. Under intense illumination, InAs nanostructures can accumulate heat, especially when strong optical resonances are excited (as in the proposed metasurface design). However, its high melting point and chemical stability allow it to maintain structural and functional integrity in many optical absorber configurations. SiO₂ acts as a thermally stable and optically passive substrate, but its low thermal conductivity means it doesn’t actively cool the InAs layer. This makes thermal management of the whole stack dependent on heat spreading through the InAs or via heat sinking to the surrounding environment. InAs maintains optical and structural performance under pulsed and CW laser illumination up to intensities used in most photodetector or solar cell applications. Thermal degradation becomes a concern only at extreme power densities, e.g., in concentrated photovoltaics or high-power laser systems. In high-power focused-beam environments, heat sinking or pulse-based operation may be necessary to prevent thermal damage. For more information, please see30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40.

For solar radiation applications, one should consider the temporal and spatial incoherence of the sun light. The former is due to the spectral width and the latter is due to the finite angular size of the sun. Temporal coherence affects how well narrowband resonances are excited41. The proposed absorbers are broadband and made from lossy, low-Q Mie-type resonances. Therefore, they do not rely on highly coherent excitation, and broadband incoherent light like sunlight is still efficiently absorbed. In other words, temporal incoherence of sunlight has minimal impact on the proposed absorbers performance due to the broad and overlapping resonances. Spatial incoherence means that different regions of the metasurface may be illuminated with different phases. In coherence-sensitive metasurfaces (e.g., Fano-resonant or interference-based designs), this would degrade performance. However, the proposed absorbers use localized resonances (Mie-type) in periodic arrays, which are not phase-sensitive across spatial domains42.

It is instructive to compare the angular stability of the proposed absorber with that of the phase gradient metasurfaces, where engineered phase profiles manipulate how incident light couples into resonant modes across a range of angles. In the proposed absorber the angular-insensitive absorption arises from multiple resonances with weak angular dispersion. To be more specific, in the proposed absorber the resonances are localized and non-directional, i.e., less sensitive to the in-plane wavevector. In addition, they are broad and overlapping, which smooths out the angular response. Thus, the proposed structure achieves angular insensitivity by spectral and geometric overlap of weakly dispersive modes, while phase-gradient designs achieve it through lateral phase engineering43.

For large incident angles the simulation time increases significantly, and thus designing absorbers by an exhaustive search procedure becomes computationally prohibitive even for a small number of \(\:{r}_{1}\), \(\:{r}_{2}\), \(\:{d}_{1}\), and \(\:{d}_{2}\) test samples. Table 7 compares the computational time demand for the brute force search and ANN-assisted method for both proposed absorbers, indicating significant time savings when utilizing ANNs. To find the optimized absorption in the brute force approach, it is necessary to take the search resolution as small as possible. In contrast, in the ANN approach there is no need to consider small resolutions since the ANN can predict optimal structural parameters through interpolation and thus the optimal solution may be outside the input dataset. Note that the simulation time increases with the incident angle. Therefore, the total simulation time is a weighted summation of simulations with different incident angles.

Table 8 compares the proposed structures in this study with previous works, where the two proposed absorbers in this study, have shown superior performance. In the first structure, the average absorption reached a remarkable 99.50%, which is the highest absorption value among all works presented in the table, including metal-based absorbers. This absorber consists of only two layers, which is more optimized and simpler compared to other absorbers that have more layers (such as the structure in7 with 6 layers). It exhibits good angular stability, similar to previous works, and also provides complete polarization independency in the 0o−90o range for TE and TM modes, which is considered one of its very important advantages. The second structure, with an average absorption of 92.46%, although lower in absorption than the first structure, has the best angular stability performance among all dielectric-based works. By providing very good angular and polarization stability in the 0o−90o range for TE and TM modes, the second absorber becomes a very suitable option for applications imposed by very oblique incidence angles. It has also been able to achieve a better angular response compared to plasmonic metal-based works. For example, only works13,14 have been able to report 70o of angular stability, which is only achievable in TM mode.

Although the proposed unit cells are larger in size than many works cited in Table 8, they include only two layers. In terms of compatibility with CMOS and nanofabrication techniques, the lateral size (~ 400 nm) is well within the resolution limits of electron beam lithography (EBL), nanoimprint lithography (NIL), and deep-UV photolithography. In addition, the vertical height (~ 1.26 μm) is achievable via thin-film deposition (e.g., MBE, sputtering, or ALD) and etching techniques common in semiconductor fabrication30. In terms of scalability to large-area devices, the periodicity of 400 nm enables dense tiling over large areas without introducing diffraction artifacts in the visible spectrum. Furthermore, structures with subwavelength periodicity are essential for maintaining homogeneous effective medium behavior, minimizing angular scattering and maximizing absorption. Thus, large-area fabrication (cm² to wafer-scale) is feasible using NIL or laser interference lithography, offering a clear path toward solar cells, photodetectors, and wearable optical devices31. In terms of mechanical integration into flexible platforms, t the first glance the height (~ 1.26 μm) may seem relatively thick compared to ultrathin films. On the other hand, conventional InAs wafers and SiO2 substrates are rigid and brittle, which is standard for laboratory or industrial photonic and photovoltaic devices. Although such material is not inherently bendable it’s still compatible with flexible electronics when embedded in soft polymer substrates or transferred via lift-off techniques. Nanostructured layers of this scale can be adapted to conformal substrates if built from discrete unit cells rather than continuous layers49.

Conclusions

This paper aims to design and optimize broadband optical absorbers at the visible spectrum 400–800 nm for use in ambient light harvesting. Thy are designed based on all-dielectric metasurfaces with InAs nanorods atop a substrate of the same material, which is backed by a SiO2 layer. All-dielectric absorbers exhibit high absorption and significant angular stability due to the elimination of ohmic losses. The first absorber can achieve extremely high average absorption, i.e. 99.50%, at normal incidence. The second absorber offers very good angular stability, i.e. up to 70o, for both TE and TM polarizations. The current research shows that all-dielectric metasurfaces can be a suitable alternative to plasmonic structures in broadband optical absorbers. The use of ANN reduced computational time and complexity and allowed for accurate modeling of the nonlinear relationships between design parameters and absorption results. The proposed absorbers are superior to previous counterparts due to their high absorption, suitable angular stability, independence from light polarization, and fewer layers. These features along with thermal stability and robustness to temporal and spatial incoherence of incident light have made the proposed absorbers a suitable option for light harvesting in applications such as solar cells and photovoltaics.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chen, Z. et al. Dual band perfect absorber for a mid-infrared photodetector based on a dielectric metal metasurface. Photonics Res. 9 (1), 27–33 (2021).

Chen, C. Y. et al. Ultra-broadband high-entropy oxide absorber layer for enhanced photodetector performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 15 (45), 52716–52723 (2023).

Bhattarai, S. et al. Perovskite solar cells with dual light absorber layers for performance efficiency. Energy Fuels. 37 (14), 10631–10641 (2023).

Sajid, M. et al. Boosting solar cell performance: optimization of WS2 absorber with Cu2o HTL & ZnSe ETL using SCAPS-1D simulation. J. Opt. (2024).

Shahbazi, M., Hosseini, K. & Razaghi, M. High-resolution prism/(TiO2/SiO2)3/MoSe2 Bloch surface wave biosensor based on Bragg structure. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 37 (17), 985–988 (2025).

Khani, A., Razaghi, M., Hosseini, K. & Fotouhi, B. Highly sensitive optical surface plasmon resonance biosensor based on BK7/Ag/TiO2/Al2O3 grating for cancer detection. Plasmonics (2025).

Yu, Y., Yu, Z. & Sun, X. Nonmetallic broadband visible-light absorbers with polarization and incident angle insensitivity. IEEE Photonics J. 12 (6), 1–7 (2020).

Cummins, C. et al. An ultra-thin near-perfect absorber via block copolymer engineered metasurfaces. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 609, 375–383 (2022).

Hosseini, K. & Atlasbaf, Z. PLRC-FDTD modeling of general GSTC-based dispersive bianisotropic metasurfaces. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 66 (1), 262–270 (2017).

Cui, T. J., Liu, S. & Zhang, L. Information metamaterials and metasurfaces. J. Mater. Chem. C. 5 (15), 3644–3668 (2017).

Hedayati, M. K., Faupel, F. & Elbahri, M. Review of plasmonic nanocomposite metamaterial absorber. Materials 7 (2), 1221–1248 (2014).

Shuvo, M. M. K. et al. A wide-angle, enhanced oblique incidence, bend-able metamaterial absorber employed in visible region with a sun shape resonator. IEEE Access. 9, 126466–126480 (2021).

Sayed, S. I., Mahmoud, K. R. & Mubarak, R. I. Design and optimization of broadband metamaterial absorber based on manganese for visible applications. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 11937 (2023).

Sayed, S. I., Mahmoud, K. R. & Mubarak, R. I. Strong and broadband visible absorption based on titanium patterned resonator. Plasmonics 19 (3), 1145–1152 (2024).

Huang, L. J. et al. Broadband visible light absorber based on ultrathin semiconductor nanostructures. Chin. Phys. B. 29 (1), 014201 (2020).

Zhou, J. et al. Cross-shaped titanium resonators based metasurface for ultra-broadband solar absorption. IEEE Photonics J. 13 (1), 1–8 (2021).

Hoa, N. T. Q., Lam, P. H., Tung, P. D., Tuan, T. S. & Nguyen, H. Numerical study of a Wide-Angle and Polarization-Insensitive ultrabroadband metamaterial absorber in visible and Near-Infrared region. IEEE Photonics J. 11 (1), 1–8 (2019).

Liu, J. et al. Numerical analysis of an ultra-wideband metamaterial absorber with high absorptivity from visible light to near-infrared. Opt. Express OE. 28 (16), 23748–23760 (2020).

Liao, Y. L., Zhou, J., Chen, Z., Zhou, X. & Zhao, Y. Ultra-broadband absorber based on photonic topological transition with large-ε′ metals. Results Phys. 57, 107378 (2024).

Moitra, P., Slovick, B. A., Gang Yu, Z., Krishnamurthy, S. & Valentine, J. Experimental demonstration of a broadband all-dielectric metamaterial perfect reflector. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104 (17), (2014).

Tian, X. & Li, Z. Y. Visible-near infrared ultra-broadband polarization-independent metamaterial perfect absorber involving phase-change materials. Photonics Res. 4 (4), 146–152 (2016).

Li, C. et al. Multipole resonance in arrays of diamond dielectric: A metamaterial perfect absorber in the visible regime. Nanomaterials 9 (9), (2019).

Cai, B., Wu, L., Zhu, X., Cheng, Z. & Cheng, Y. Ultra-broadband and wide-angle plasmonic light absorber based on all-dielectric gallium arsenide (GaAs) metasurface in visible and near-infrared region. Results Physics 58, 107509 (2024).

Wu, L., Yang, L., Zhu, X., Cai, B. & Cheng, Y. Ultra-broadband and wide-angle plasmonic absorber based on all-dielectric gallium arsenide pyramid nanostructure for full solar radiation spectrum range. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 201, 109043 (2024).

Zhao, J., Wang, Y., Zhu, Y., Zhang, W. & Yu, Y. Lithography-free flexible perfect broadband absorber in visible light based on an all-dielectric multilayer structure. Opt. Lett. 45 (19), 5464–5467 (2020).

Xu, R. & Takahara, J. Stacked all-dielectric absorber based on degenerate critical coupling for visible to near-infrared light. Appl. Phys. Express. 15 (12), 122006 (2022).

Ding, Z. et al. Machine learning in design of broadband terahertz absorbers based on composite structures. Mater. Design 233 112215. (2023).

Sharifi, E., Razaghi, M. & Hosseini, K. Broadband all-dielectric metasurface absorber for VLC applications. In 6th Iranian International Conference on Microelectronics (IICM) 1–5, (2024).

Razeghi, M. Fundamentals of Solid State Engineering 3rd edn (Springer, 2009).

Lecestre, A., Martin, M., Cristiano, F., Baron, T. & Larieu, G. Large scale monolithic fabrication of III-V vertical nanowires on a standard Si(100) microelectronics substrate. ACS Omega. 7 (7), 5836–5843 (2022).

Dhindsa, N. et al. Highly ordered vertical GaAs nanowire arrays with dry etching and their optical properties. Nanotechnology 25 (30), (2014).

Fu, Z., Liu, G. & Guo, L. Sequential quadratic programming method for nonlinear least squares Estimation and its application. Math. Probl. Eng. 1, 3087949 (2019).

Khan, M. S., Varshney, G. & Giri, P. Altering the multimodal resonance in ultrathin silicon ring for tunable THz biosensing. IEEE Trans. Nanobiosci. 20 (4), (2021).

Tretyakov, S. Analytical Modeling in Applied Electromagnetics (Artech House, 2003).

Ra’di, Y., Simovski, C. R. & Tretyakov, S. A. Thin perfect absorbers for electromagnetic waves: theory, design and realizations. Phys. Rev. Appl. 3 (3), 037001 (2015).

Aspnes, D. A. & Studna, A. A. Dielectric functions and optical parameters of Si, Ge, GaP, GaAs, GaSb, InP, InAs, and InSb from 1.5 to 6.0 eV. Phys. Rev. B. 27, 985–1009 (1983).

Groep, J. V. D. & Polman, A. Designing dielectric resonators on substrates: combining magnetic and electric resonances. Opt. Express. 21 (22), 26285 (2013).

Joannopoulos, J. D., Johnson, S. G., Winn, J. N. & Meade, R. D. Photonic Crystals: Molding the Flow of Light 2nd edn (Princeton University Press, 2008).

Madelung, O. Semiconductors: Data Handbook 3rd edn (Springer, 2004).

Zograf, G. P., Petrov, M. I., Makarov, S. V. & Kishwar, Y. S. All-dielectric thermonanophotonics. Adv. Opt. Photonics. 13 (3), 643–702 (2021).

Ricketti, B. V., Gauger, E. M. & Fedrizzi, A. The coherence time of sunlight in the context of natural and artificial light harvesting. Sci. Rep. 12, 5438 (2022).

Sarrazin, M., Herman, A. & Deparis, O. First-principle calculation of solar cell efficiency under incoherent illumination. Optics Express 21 (S4), A616-A630, (2013).

Ding, F., Pors, A. & Bozhevolnyi, S. I. Gradient metasurfaces: a review of fundamentals and applications. Rep. Prog. Phys. 81 (2), 026401 (2017).

Berka, M. et al. Nano-resonator based broadband metamaterial absorber with angular stability operating in visible light spectrum for solar energy harvesting applications. Opt. Mater. 149, 115043 (2024).

Sayed, S. I., Mahmoud, K. R., Mubarak, R. I. Circuit modeling and hybrid optimization of a lithography-free visible metamaterial absorber. Discover Appl. Sci. 7 (790), (2025).

Daliran, N. & Hassanzadeh, A. Broadband MXene-based metasurface absorber for visible region. Plasmonics 20, 2921–2930 (2025).

Kumar, R. et al. Engineering of Ultra-Wide bandwidth metamaterial absorber with various shaped resonators in the visible to far-infrared spectrum. Plasmonics 1–18. (2025).

Kumar, R. et al. Wide-angle and polarization insensitive perfect metamaterial absorber. Mod. Phys. Lett. B. 38 (18), 2450105 (2024).

Wolf, I. D. Micro-Raman spectroscopy to study local mechanical stress in silicon integrated circuits. Semiconductor Sci. Technol. 11 (2), (1996).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conceived the idea, E.S. performed the numerical simulations, M.R. and K.H. conducted the theoretical work, E.S. and K.H. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sharifi, E., Razaghi, M. & Hosseini, K. ANN assisted design of broadband near perfect metasurface absorbers exploiting InAs nanorods for visible light harvesting. Sci Rep 15, 31060 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16731-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16731-w