Abstract

In this study, we analyze a novel m-plane GaN Terahertz Quantum Cascade Laser (THz QCL) with a resonant phonon depopulation scheme using the Non-equilibrium Green’s Function (NEGF) approach. This design offers a more practical alternative to the previously proposed Two-Well (TW) GaN THz QCL, featuring significantly lower operating currents, reducing the risk of thermal damage, and greatly enhances the feasibility of experimental realization. The addition of an extra barrier also reduces leakage into the continuum and into the excited states. Accounting for leakage into excited states, a factor often neglected in prior works, a peak gain of ~ 76 cm⁻¹ was observed at low temperatures, decreasing to ~ 24 cm⁻¹ at 300 K, comparable to the expected losses, making the structure suitable for near -room-temperature applications. Our results predict promising high temperature operation at ~ 6.5 THz, surpassing the frequency coverage of standard GaAs-based THz QCLs. This work advances the development of GaN-based THz QCLs towards room-temperature performance and expanded frequency coverage compared to GaAs/AlGaAs THz-QCL, addressing key challenges in Terahertz technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Terahertz (THz) technology is revolutionizing various domains, spanning security1 healthcare2 and industrial sectors. THz imaging enhances threat detection capabilities without posing any risk to human health3 it facilitates safer diagnostic procedures by penetrating bodily tissues non-invasively4 and plays a fundamental role in non-destructive material analysis5 thereby augmenting manufacturing precision. Moreover, THz technology is instrumental in advancing disciplines such as chemistry6 astronomy7 materials science8 communication systems9 and physics research10. The exploitation of the THz frequency spectrum holds immense promise for transformative breakthroughs, opening avenues to yet unexplored realms of innovation.

The spectral region between microwave and infrared waves, typically spanning from about 0.1 to 10 THz has long been considered challenging to harness due to technological limitations. Often named the “THz gap,” it has historically presented obstacles for both generation and detection of THz radiation. The introduction of THz QCLs (Quantum Cascade Lasers) caused a considerable change, giving fresh insight on this frequency gap11. These efficient semiconductor devices have revolutionized the field by allowing precise manipulation and generation of THz radiation, addressing a critical technological gap. As scientists continue to push the boundaries of THz QCL capabilities, they are paving the way for realizing the full potential of this technology12,13,14,15,16.

Despite the numerous advantages offered by THz QCLs, they have yet to result in a commercially viable THz source. The need for cooling restricts THz QCLs to laboratory settings, frustrating the development of a compact and portable THz source. Consequently, increasing the maximum operating temperature (Tmax) remains the primary goal in the field.

A significant achievement was making a portable device, which could operate at a maximum temperature of ~ 250 K17 and after some optimizations reaching a record Tmax of ~ 261 K, using the GaAs/AlGaAs material system18. However, it is important to note that despite these advancements, getting THz QCLs to work at room temperature is still a challenge.

Conventional GaAs-based THz QCLs have been restricted to lasing frequencies experimentally demonstrated in the range of 1–6 THz19,20,21. While theoretical studies have indicated the possibility of reaching up to 6.6 THz22 practical operation beyond 6 THz remains challenging. This restriction is primarily due to the relatively low energy of the forbidden Reststrahlen bands in GaAs materials, between transverse optical phonon energy ETO = 34.5 meV and longitudinal optical phonon energy ELO = 36.0 meV (in practice due to the rapid dispersion of refractive index (dn/dE) the forbidden region is wider, approximately 25–45 meV), and the rapid non-radiative transitions facilitated by longitudinal optical (LO) phonons. To overcome these constraints, GaN-based devices have emerged as promising alternatives. GaN possesses a significantly larger LO-phonon energy of ~ 90 meV compared to GaAs’s ~ 36 meV. This characteristic offers potential solutions by mitigating thermal backfilling and depopulating the upper laser level (ULL) through thermally activated LO-phonon transitions23,24,25,26. In theory, GaN-based THz QCLs could effectively bridge the frequency gap while also enabling higher operating temperatures.

Until now, a substantial portion of scientific inquiry regarding the inter-subband (ISB) transitions in group III-nitride multi-quantum-wells (MQWs) has been focused on structures aligned with the polar c-axis. However, this particular crystallographic orientation brings about an internal electric field due to polarization effects27. The inherent electric field, caused by polarization effects, presents a substantial obstacle in the design of THz QCLs based on GaN in c-plane28. For semiconductor devices, understanding the energy levels of subbands is crucial for various processes like band alignment, which determines how different materials with differing electronic properties align when brought into contact. This alignment affects device performance, such as in the case of semiconductor heterojunctions or interfaces. The presence of internal electric fields resulting in a trapezoidal conduction band profile indeed poses challenges in determining subband state energies, particularly for the alignment process29. Despite concerted efforts to lessen this issue, such as incorporating complex multi-layer QW architectures30 the challenges persist. These complex designs are intended to partially offset the effects of the electric field. However, its impact remains a significant consideration and limitation in the domain of device design and optimization. Thus, addressing and effectively mitigating the influence of this electric field is imperative for advancing the practical utility and efficacy of THz QCLs based on GaN/AlGaN technology.

Employing nonpolar crystallographic orientations represents an alternative strategy to obtain GaN/AlGaN heterostructures, aimed at mitigating the presence of internal electric fields within the material system. By selecting nonpolar orientations, such as the m-plane, the inherent polarization-related electric fields commonly observed in polar crystal orientations can be effectively eliminated31. The adoption of nonpolar crystallographic orientations in the design of GaN/AlGaN heterostructures offers a promising pathway towards realizing advanced semiconductor devices with improved performance, reliability, and design flexibility32.

Methods

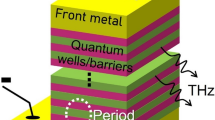

Within this study, we have theoretically analyzed a three quantum well period m-plane GaN/Al0.14Ga0.86N THz-QCL structure based on a resonant-phonon (RP) scattering scheme. Our main goal was to design a practical structure and to avoid the limitations previously observed in m-plane GaN. While Nitride structures grown on nonpolar crystal planes do not demonstrate inherent polarizations, their utilization in material growth presents its own set of challenges. These issues are mostly due to the high defect densities, pronounced anisotropy, susceptibility to cracking, formation of hillocks, and the occurrence of basal plane stacking faults33. We optimized the aluminum concentration in AlxGa1−xN barriers to x = 14% for optimal QCL design and34,35 and to prevent defects, dislocations, and surface degradation.

The design presented in this work has an additional barrier compared to the previously presented TW m-plane GaN-based THz QCL36. Adding another barrier to the structure could potentially lead to reduced leakage both to the continuum and to excited states and, consequently, to above room-temperature performance37,38.

Our investigation explored the carrier distribution and gain properties of the resonant phonon structure, employing a comprehensive analysis. To achieve this, we used simulations based on a self-consistent approach that incorporates techniques based on non-equilibrium Green’s functions (NEGF). These features enable a detailed investigation into the electronic transport properties and overall performance attributes of the scheme39,40,41. In our computational work, we considered various scattering mechanisms that influence carrier dynamics. These include elastic scattering processes such as ionized impurities (IIS), interface roughness (IFR), electron-electron (e-e) interactions, and alloy disorders, as well as inelastic scattering processes involving interactions with optical and acoustic phonons.

Throughout our simulations, we maintained consistency by setting the roughness height parameter at a constant value of 1 Å, coupled with a correlation length of 80 Å. These specific parameter values adhere to widely accepted standards in the field and approximate the interface roughness of one atomic layer42,43,44. In addition, our simulations include excited states, a factor often neglected in prior works45 including these levels in the simulation show the real feasibility of an experimental device46 whereas excluding them would result in an overestimation of the gain and would not reveal the actual extent of the leakages47,48.

Results and discussions

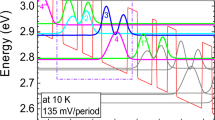

Figure 1 illustrates the conduction band diagram of an m-plane GaN THz-QCL including three quantum wells based on a resonant phonon scheme. The structure consists of four subbands within each module. The layer sequence within one period, starting from the injection barrier, is as follows: 15/60/18/33/13/30 Å, with the barriers indicated in bold font. A sheet doping density of 2.7 × 1011 cm−2 is applied, the doped region’s width is 3 nm and positioned in the center of the widest well34. In the diagram, the upper laser level (ULL) (level 2 in the scheme) is aligned with the injector of the preceding module, facilitating resonant tunneling with an anticrossing energy of ∼ 8 meV. The radiative transition occurs between the ULL (level 2 in the scheme) and the lower laser level (LLL) (level 3 in the scheme), with an oscillator strength value of f23∼ 0.3. Following this transition, the LLL is depopulated by the extraction level (level 4 in the scheme), and electrons are rapidly relaxed into the injector level (level 1’ in the scheme) via LO-phonon scattering. Subsequently, these electrons are injected into the next period. To accelerate depopulation through LO-phonon scattering relaxation, the energy difference between the LLL and the injector level is ∼95 meV, about the LO phonon energy. The high anticrossing energy of ∼ 8 meV is attributed to the strong LO phonon coupling strength, which is 16 times stronger than that of GaAs44. In efforts to enhance the device’s performance, gain optimization for room temperature operation was conducted using NEGF calculations34.

Our research includes optimization of doping levels, a strategy that has proved to lead to successful outcomes36. The assumption that higher doping density significantly enhances gain performance is not always true43. The increased doping density can result in stronger Coulomb scattering effects within the device49,50. However, in our research, we achieved a significant increase in doping levels while still observing an improvement in gain. Interestingly, we managed to achieve doping levels one order of magnitude higher than those typically seen in GaAs devices. The driving force behind this enhanced doping lies in the considerable energy difference (~ 95 meV) between the LLL and the injector level within our GaN-based structure. This energy difference is significantly larger compared to the ~ 36 meV typically found in GaAs. This energy difference plays a critical role in suppressing the thermal backfilling effect, allowing us to increase the doping density significantly within our structure. By mitigating thermal backfilling, we were able to raise the doping levels considerably, leading to an increase in gain. However, high doping also increases current, which can eventually cause the device to burn out. A key achievement of this work, compared to the previous TW structure36 is the addition of another barrier, which significantly reduces the high current density.

Figure 2 represents the current density as a function of voltage in different temperatures in the TW and resonant phonon (RP) schemes. At elevated bias levels, the energy separation between subbands increases, which facilitates resonant tunneling and thermionic emission of carriers into higher-lying or continuum states. As the temperature rises, carriers gain more thermal energy, increasing the probability of leakage over barriers. These processes contribute to an increase in current density with temperature. As can be seen from the figure, Although the doping density is identical in both the RP and TW designs, the current density is reduced by almost a factor of two in the RP scheme in comparison to the TW scheme36. This reduction arises from the insertion of an additional barrier which introduces an additional tunneling step. This slows down carrier transport, effectively reducing the current density. Moreover, the added barrier enhances electron confinement, suppresses leakage into higher energy states, and promotes a more uniform electric field distribution. These combined effects enable efficient lasing at lower current densities, an important advantage for high-temperature operation. This is a major achievement that improves the feasibility of an experimental device and lowers the risk of thermal damage.

The current density level within this work should be within a practical range for achieving pulsed laser operation, marking an encouraging and meaningful step forward for GaN-based THz QCL development. This design demonstrates a significantly higher feasibility of experimental success compared to our previous work36.

While the current density in our work remains high and represents a key challenge, we view this as a promising foundation, and further efforts will focus on optimizing the design to reduce current density, with the aim of enabling continuous-wave operation and enhancing device efficiency.

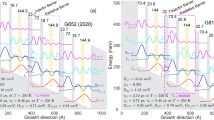

Figure 3a and b represents the optical gain versus photon frequency with bias voltage of 145 mV/module in various temperatures with and without the inclusion of excited states respectively. The bias point of 145 mV/module represents a trade-off that ensures optimal overlap of wavefunctions and transition energies, maximizing optical gain. This bias point was validated through a systematic voltage sweep.

In Fig. 3a, the peak of the curve corresponds to a photon frequency of ~ 6.5 THz. Our simulation shows that at 20 K and in 300 K the gain values are 76 cm−1 and 24 cm−1 respectively, which is in the range of estimated losses even at 300 K (αloss = 30 cm−1)36,51 and shows the practicality for room temperature operation. Our simulation includes all the scattering mechanisms and the excited states in order to show the feasibility of a realistic device. However, not including excited states in the calculation would result in higher gain values. While material-related losses due to doping and temperature are inherently captured through this method, our gain simulations do not directly account for waveguide-related losses such as absorption, mirror losses, and confinement efficiency. To address this, we relied on literature values51 which reports loss values ranging from 15 to 30 cm⁻¹ for GaN-based THz QCLs, depending on waveguide design and frequency. To maintain a conservative estimate and ensure our conclusions are robust, we adopted the upper bound of 30 cm⁻¹ as a constant loss value in our threshold analysis.

To illustrate the impact of excited-state inclusion, Fig. 3b shows the optical gain versus photon frequency in various temperatures with the elimination of the excited states and demonstrates gain values of 110.3 cm−1 and 55. 4 cm−1 at temperatures of 20 K and 300 K respectively. Our simulations were carried out using the Schrödinger–Poisson solver under the single-band effective mass approximation. Within this framework, a cutoff is applied to restrict the number of quantized energy levels considered in each quantum well, thereby controlling the inclusion of higher-energy (excited) states. This is done by specifying an energy range parameter that defines the interval above the conduction band edge in which eigenstates are computed. By selecting a reduced energy window, states located near or above the barriers, typically corresponding to excited levels, are excluded from the eigenstate spectrum, enabling targeted investigation of ground-state transport and optical transitions.

To further understand the impact of the broadening levels and the impact of the temperature we presented the spectral functions in Fig. 4, these calculations were done using NEGF simulations and include all elastic and inelastic scattering mechanisms, as explained before. Figure 4a and b display the spectral functions of the injector, ULL, and LLL at temperatures of 10 K and 300 K, respectively, under equivalent conditions. Observing the figures, it becomes apparent that elevating the temperature yields minimal impact on the LLL and injector, with the curves exhibiting only marginal expansion. The ULL broadens more significantly, indicating a decrease in its lifetime. However, even at room temperature, we observe performance improvements surpassing losses. From these figures, we can also see that the line width of the LLL is narrower compared to the TW scheme at low temperatures36. This distinction stems from the different depopulation mechanisms employed in each scheme. In the TW scheme, the LLL involved in the radiative transition and also depopulated directly via LO phonon scattering, which leads to strong inelastic broadening. In contrast, in the RP scheme, the LLL is primarily used for lasing, while depopulation occurs via resonant tunneling to an extraction level, which is then depopulated by LO phonon emission. This design decouples the LLL from strong LO phonon interactions, resulting in reduced linewidth broadening.

At a lattice temperature of 10 K, our simulations show that the LLL linewidth in the TW scheme is approximately 34 meV, whereas in the RP scheme it is reduced to 25 meV. This ̴26% reduction in linewidth is significant, as it indicates lower dephasing and improved spectral coherence in the RP scheme. The narrower linewidth can lead to higher peak gain and a sharper gain spectrum, which are critical factors for efficient lasing and stable frequency operation.

Figure 5 illustrates the normalized population distribution within our system, in the injector, ULL, LLL, and extractor level, and population inversion, Δn, all as functions of temperature at a bias of 145 mV/period. A closer examination reveals a slight decline in the ULL and injector populations. This population drop in the ULL can be attributed to electron leakage into higher excited states. Additionally, the LLL population also increases to some extent probably due to thermal backfilling. The population inversion remains relatively stable, experiencing only a minor reduction, transitioning from a value of 0.29 to 0.25. This marginal decline indicates a stable population inversion, also at room temperature. This figure shows a comprehensive view of the intricate population dynamics within our system. This deeper understanding is invaluable for refining our design and optimizing its performance.

In our pursuit of refining the optimization of our design, we have initiated a meticulous examination of the discrete scattering mechanisms and their respective implications on optical gain. Figure 6 stands as a crucial visual aid in this effort, depicting the relationship between optical gain and photon frequency as we systematically eliminate each scattering mechanism individually.

Our investigation has produced compelling findings. Firstly, alloy scattering emerges as having a negligible effect on optical gain. Intriguingly, even in the presence of a high doping level, IIS does exert a discernible impact on optical gain, although to a lesser extent. Our comprehensive analysis underscores that the scattering mechanisms predominantly influencing gain are electron e-e scattering, attributable to elevated doping levels, and IFR. These two mechanisms emerge as pivotal determinants shaping the optical gain characteristics of our design.

Due to the critical impact of IFR scattering on the device performance, a comparative analysis was carried out, keeping all other scattering parameters constant, as depicted in Fig. 7 which represents the optical gain as a function of photon frequency. The simulations were performed at 10 K and bias voltage of 145 mV. The gain curve reveals intriguing insights: when the in-depth roughness height parameter is set to 0, the gain reaches an impressive value of 142.3 cm⁻¹. However, as this parameter is increased, the gain experiences a noticeable decline. These findings underscore the remarkable sensitivity of this structure to IFR. This heightened sensitivity underscores the high necessity of engineering of an interface of the highest quality52. This necessity arises from the substantial penetration of wave functions deep into the barriers, demanding the utmost precision in managing IFR. The presence of a large LO phonon coupling strength, which induces line broadening, further accentuates the need for strong coupling. The line broadening results in the penetration of the wave functions tails into the barriers, ultimately resulting in a device characterized by exceedingly high IFR. In essence, these insights emphasize the non-negotiable requirement for meticulous interface design and underscore the intricate interplay of factors that shape the performance of our device.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study presents a theoretical exploration of a novel resonant phonon, three-well, m-plane GaN scheme for THz QCLs. We show careful and detailed calculations for carrier transport and gain properties, employing self-consistent NEGF method. Our scheme exhibits a peak gain of ~ 76 cm−1 at a temperature of 10 K and 24 cm−1 even at room temperature. These results surpass the results previously obtained for the TW scheme36 where the maximum operating temperature expected was ~ 280 K. A significant achievement in our work has been the successful enhancement of doping levels, improving the performance of THz QCLs based on GaAs by an order of magnitude. The addition of an extra barrier significantly mitigated the high current density caused by the high doping density and led to reduced leakage to excited states and continuum. The current density in the RP scheme is reduced by nearly a factor of two compared to the TW scheme with the same doping level. This substantial reduction marks a significant achievement, greatly improving the feasibility of realizing a functional experimental device, reducing the risk of thermal damage. In addition, our simulations have unequivocally identified e-e scattering, attributed to the high doping levels, as the primary limiting mechanism within our structure. Moreover, we have demonstrated the structure’s remarkable sensitivity to minimal variations in IFR parameters, owing to the deep penetration of wave functions into the barriers. Further improvements can be achieved by optimizing laser performance through a reduction in leakage to excited states. Our findings strongly indicate the feasibility of operation frequency at ~ 6.5 THz, a frequency range beyond the capabilities of traditional GaAs THz QCLs with room temperature performance operation. GaN-based THz QCLs have demonstrated significant promise, offering a potential solution for bridging the entirety of the THz frequency spectrum, in high-temperature operation and striving toward developing future practical use devices.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kemp, M. C. et al. SPIE,. Security applications of terahertz technology. in Terahertz for Military and Security Applications (eds. Hwu, R. J. & Woolard, D. L.) vol. 5070 44–52 (2003).

Gezimati, M. & Singh, G. Terahertz imaging and sensing for healthcare: current status and future perspectives. IEEE Access. 11, 18590–18619 (2023).

Liu, H. B., Zhong, H., Karpowicz, N., Chen, Y. & Zhang, X. C. Terahertz spectroscopy and imaging for defense and security applications. Proc. IEEE. 95, 1514–1527 (2007).

Wang, J., Lindley-Hatcher, H. & Chen, X. & Pickwell-MacPherson, E. THz Sensing of Human Skin: A Review of Skin Modeling Approaches. Sensors 21, (2021).

Tao, Y. H., Fitzgerald, A. J. & Wallace, V. P. Non-Contact, Non-Destructive testing in various industrial sectors with Terahertz technology. Sensors 20, 712 (2020).

Fischer, B. M., Helm, H. & Jepsen, P. U. Chemical Recognition With Broadband THz Spectroscopy. Proc. IEEE 95, 1592–1604 (2007).

Kawano, Y. Terahertz waves: a tool for condensed matter, the life sciences and astronomy. Contemp. Phys. 54, 143–165 (2013).

Yang, L., Guo, T., Zhang, X., Cao, S. & Ding, X. Toxic chemical compound detection by Terahertz spectroscopy: a review. Rev. Anal. Chem. 37, 20170021 (2018).

Elayan, H., Amin, O., Shihada, B., Shubair, R. M. & Alouini, M. S. Terahertz band: the last piece of RF spectrum puzzle for communication systems. IEEE Open. J. Commun. Soc. 1, 1–32 (2020).

Du, W., Huang, Y., Zhou, Y. & Xu, X. Terahertz interface physics: from Terahertz wave propagation to Terahertz wave generation. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 55, 223002 (2022).

Köhler, R. et al. Terahertz semiconductor-heterostructure laser. Nature 417, 156–159 (2002).

Albo, A. & Hu, Q. Investigating temperature degradation in THz quantum cascade lasers by examination of temperature dependence of output power. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 131108 (2015).

Albo, A., Hu, Q. & Reno, J. L. Room temperature negative differential resistance in Terahertz quantum cascade laser structures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 081102 (2016).

Albo, A., Flores, Y. V., Hu, Q. & Reno, J. L. Two-well Terahertz quantum cascade lasers with suppressed carrier leakage. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 111107 (2017).

Lander Gower, N., Piperno, S. & Albo, A. Self-consistent gain calculations and carrier transport analysis for split-well direct-phonon Terahertz quantum cascade lasers. AIP Adv. 10, 115319 (2020).

Levy, S. et al. Split-well resonant-phonon Terahertz quantum cascade laser. Opt. Express. 31, 22274–22283 (2023).

Khalatpour, A., Paulsen, A. K., Deimert, C., Wasilewski, Z. R. & Hu, Q. High-power portable Terahertz laser systems. Nat. Photonics. 15, 16–20 (2021).

Khalatpour, A. et al. Enhanced operating temperature in Terahertz quantum cascade lasers based on direct phonon depopulation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 161101 (2023).

Lander Gower, N. et al. Two-well injector direct-phonon Terahertz quantum cascade lasers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 061109 (2023).

Albo, A., Flores, Y. V., Hu, Q. & Reno, J. L. Split-well direct-phonon Terahertz quantum cascade lasers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 191102 (2019).

Shahili, M. et al. Continuous-wave gaas/algaas quantum cascade laser at 5.7 THz. Nanophotonics 13, 1735–1743 (2024).

Ushakov, D. V. et al. Feasibility of gaas/algaas quantum cascade laser operating above 6 THz. J. Appl. Phys. 135, 133108 (2024).

Bellotti, E., Driscoll, K., Moustakas, T. D. & Paiella, R. Monte Carlo study of GaN versus GaAs Terahertz quantum cascade structures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 101112 (2008).

Terashima, W. & Hirayama, H. Design and fabrication of Terahertz quantum cascade laser structure based on III-nitride semiconductors. Phys. Status Solidi C. 6, S615–S618 (2009).

Gower, N. L. et al. Extraction of the electron excess temperature in Terahertz quantum cascade lasers from laser characteristics. Nanophotonics https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2023-0617 (2024).

Albo, A. & Flores, Y. V. Temperature-Driven enhancement of the stimulated emission rate in Terahertz quantum cascade lasers. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 53, 1–5 (2017).

Fiorentini, V., Bernardini, F. & Ambacher, O. Evidence for nonlinear macroscopic polarization in III–V nitride alloy heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 1204–1206 (2002).

Yu, E. T., Dang, X. Z., Asbeck, P. M., Lau, S. S. & Sullivan, G. J. Spontaneous and piezoelectric polarization effects in III–V nitride heterostructures. J. Vac Sci. Technol. B Microelectron. Nanometer Struct. Process. Meas. Phenom. 17, 1742–1749 (1999).

Morkoç, H., Cingolani, R. & Gil, B. Polarization effects in nitride semiconductors and device structures. Mater. Res. Innov. 3, 97–106 (1999).

Lim, C. B. et al. Effect of al incorporation in nonpolar m-plane gan/algan multi-quantum-wells using plasma-assisted molecular-beam epitaxy. Phys. Status Solidi A. 214, 1600849 (2017).

Monavarian, M. et al. Structural and optical properties of nonpolar m- and a-plane gan/algan heterostructures for narrow-linewidth mid-infrared intersubband transitions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 201103 (2020).

Moustakas, T. D. & Paiella, R. Optoelectronic device physics and technology of nitride semiconductors from the UV to the Terahertz. Rep. Prog Phys. 80, 106501 (2017).

Heber, J. D., Gmachl, C., Ng, H. M. & Cho, A. Y. Comparative study of ultrafast intersubband electron scattering times at ∼1.55 µm wavelength in gan/algan heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 81, 1237–1239 (2002).

Mensz, M. Piotr. Prospects for THz AxlGa1-xN/GaN TW-QCL Structure, Date: 16.11.2022 (Internal Report No5, unpublished). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1BUhxGkU1hyQ-vXgN-fTkMIOj841OE1qj/view?usp=drive_link

Mensz, M. Piotr. Prospects for THz AxlGa1-xN/GaN TW-QCL Structure, Date: 30.12.2022 (Internal Report No. 4, unpublished). https://hackmd.io/@uq4cs5pTRlij3lOBGh99Iw/BJocUEdBkl

Levy, S., Gower, N. L., Piperno, S. & Albo, A. Addressing broadening challenges in m-plane GaN two-well Terahertz quantum cascade laser. Opt. Express. 32, 39306–39317 (2024).

Kumar, S., Hu, Q. & Reno, J. L. 186 K operation of Terahertz quantum-cascade lasers based on a diagonal design. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 131105 (2009).

Williams, B. S. et al. Apr. Resonant-Phonon Terahertz Quantum-Cascade Laser Operating at 2.1 THz ([Lamda] = 141 Μm). Electronics Letters, vol. 40, no. 7, 1 pp. 1–2. ProQuest Central, (2004). https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/resonant-phonon-terahertz-quantum-cascade-laser/docview/1625329709/se-2. Accessed 28 Sept. 2022.

Grange, T. Electron transport in quantum wire superlattices. Phys. Rev. B. 89, 165310 (2014).

Lee, S. C. & Wacker, A. Nonequilibrium green’s function theory for transport and gain properties of quantum cascade structures. Phys. Rev. B. 66, 245314 (2002).

Wacker, A., Lindskog, M. & Winge, D. O. Nonequilibrium green’s function model for simulation of quantum cascade laser devices under operating conditions. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 19, 1–11 (2013).

Flores, Y. V. & Albo, A. Impact of interface roughness scattering on the performance of GaAs/AlxGa1–xAs Terahertz quantum cascade lasers. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 53, 1–8 (2017).

Wang, L., Lin, T. T., Chen, M. X., Wang, K. & Hirayama, H. Engineering of electron–longitudinal optical phonon coupling strength in m-plane GaN Terahertz quantum cascade lasers. Appl. Phys. Express. 14, 112003 (2021).

Wang, K. et al. Broadening mechanisms and self-consistent gain calculations for GaN quantum cascade laser structures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 113, 061109 (2018).

Ye, F. et al. M-plane GaN Terahertz quantum cascade laser structure design and doping effect for resonant-phonon and phonon-scattering-injection schemes. Sci. Rep. 13, 11394 (2023).

Lander Gower, N., Piperno, S. & Albo, A. Comparison of THz-QCL designs supporting clean N-Level systems. Photonics 8, 248 (2021).

Wang, L., Lin, T. T., Wang, K. & Hirayama, H. Parasitic transport paths in two-well scattering-assisted Terahertz quantum cascade lasers. Appl. Phys. Express. 12, 082003 (2019).

Albo, A. & Flores, Y. V. Carrier leakage dynamics in Terahertz quantum cascade lasers. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 53, 1–8 (2017).

Levy, S. et al. Analyzing the effect of doping concentration in split-well resonant-phonon Terahertz quantum cascade lasers. Opt. Express. 32, 12040–12053 (2024).

Lander Gower, N., Piperno, S. & Albo, A. The Effect of Doping in Split-Well Direct-Phonon THz Quantum-Cascade Laser Structures. Photonics 8, (2021).

Wang, K., Lin, T. T., Wang, L. & Terashima, W. Hirayama. Controlling loss of waveguides for potential GaN Terahertz quantum cascade lasers by tuning the plasma frequency of doped layers. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 57, 081001 (2018).

Lander Gower, N., Levy, S., Piperno, S., Addamane, S. J. & Albo, A. Exploring the effects of molecular beam epitaxy growth characteristics on the temperature performance of state-of-the-art Terahertz quantum cascade lasers. Sci. Rep. 14, 17411 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Israel Innovation Authority for its grant provided through the Academic Applied Research Program, the Israel Ministry of Science and Technology for their grant for proposal 0007465, and the Israel Science Foundation for its grant (ISF 1755/23).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Levy, S., Lander Gower, N., Mensz, P. et al. Practical implementation of m-Plane GaN resonant-phonon Terahertz quantum cascade laser. Sci Rep 15, 30797 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16793-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16793-w