Abstract

Western Australia (WA) experiences multiple climatic zones, influencing the epidemiology of respiratory viruses. We aimed to estimate the true incidence of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza hospitalizations across these different climatic regions using predictive modelling. We conducted a population-based cohort study using linked perinatal, hospitalization and microbiological data of children aged < 5 years, born in WA between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2021. We used multivariable logistic regression to develop and validate predictive models for RSV and influenza hospitalizations in three climatic regions: southern temperate, northern tropical, and central desert. We compared laboratory-confirmed hospitalization rates with model-predicted rates and determined under-ascertainment fractions. Our cohort comprised 466,037 hospital admissions (257,960 children), with 33,106 tested for RSV (23.4% positive) and 33,511 for influenza (3.6% positive). True hospitalization rates for RSV and influenza were highest in the central desert and northern tropical regions. Among infants, RSV rates were 36.71 versus 20.00 per 1,000 child-years, and influenza rates were 444.59 versus 144.40 per 100,000 child-years in central desert compared to southern temperate areas. Routine laboratory testing significantly underestimated RSV (by 45–69%) and influenza (by 34–52%) hospitalizations. Unlike the southern and desert regions, the northern tropics lacked clear seasonal patterns. The study highlights high under-ascertainment of RSV and influenza hospitalizations from routine viral testing. The findings suggest immunization programs should consider viral circulation timing in different climatic regions. Prediction models demonstrated reliability in estimating RSV and influenza burden across varying climates, supporting localized decision-making beyond Australia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza are two leading causes of acute lower respiratory infections (ALRI) in young children worldwide. In 2019, there were an estimated 3.6 million RSV–related ALRI hospitalizations globally1. Influenza virus was associated with 870,000 ALRI hospital admissions in children < 5 years of age worldwide in 20182. In Australia, the RSV-associated hospitalization rate for children < 5 years of age between 2006 and 2015 was 418 per 100,000 population3. In Western Australia (WA), higher incidence rates of RSV (247 per 100,000 child-years) and influenza (61 per 100,000 child-years) was reported in hospitalized children during 2000–20124.

Existing data indicate a significant under-diagnosis of RSV-associated ALRI in hospitalized children from routine viral testing5. Between 2000 and 2012 in WA, more than one–third of children who presented to the emergency department with RSV infection were coded with other infections6. These findings suggest viral testing practices might contribute to high under–ascertainment of RSV- and influenza-associated hospitalizations.

Accurate estimates of RSV- and influenza-associated hospitalizations are essential elements of monitoring progress in ALRI control interventions in the era of RSV and influenza immunization. The introduction of funded programs providing monoclonal antibodies for RSV and influenza vaccines provided great opportunities to prevent ALRI–hospitalizations. WA implemented funded RSV immunization in newborns and high-risk infants with nirsevimab in April 2024 and influenza immunization for children 6 months–4 years (2008), 5–11-year-olds (2020). Estimating the true burden of RSV and influenza hospitalization in the years leading up to this would provide valuable baseline data to evaluate the real-world impact of immunizations on preventing severe RSV or influenza disease.

The spatial and temporal dynamics of RSV and influenza are highly variable. Our recent population-based study identified a significant geographic variation in viral testing patterns, which may substantially correlate with the burden of respiratory viruses5. No other study has estimated geographic variations in respiratory virus–associated hospitalizations in WA. Previous modeling studies on RSV covered the whole of WA, but did climate differences were not modelled7. Given the differing seasonality across different regions of WA, it is crucial to estimate the burden of these two major causes of ALRI in children by geographic location and time to better understand disease burden to assist in guiding clinical decision making. This study aimed to estimate the true burden of RSV– and influenza–associated hospitalizations and measure the under-ascertainment fraction by geographic location in children under 5 years of age in WA.

Methods

Study design

A population-based longitudinal study utilizing prediction modelling based on a birth cohort with linked perinatal, hospitalization and microbiological data for children < 5 years was conducted. All the methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Study setting

WA represents the western third of Australia, with a total population of approximately 2.9 million at September 20238. WA encompasses diverse climatic zones stretching from a tropical climate in the north and desert in the central regions to a temperate climate in the south. This study included all regions of WA, which were categorized into three climatic regions: southern temperate region (including Perth City, Wheatbelt, Southwest, and Great Southern), central desert region (Goldfields and Midwest), and the northern tropical (Kimberley and Pilbara) region (Supplementary Fig. S1). This classification was also informed by the viral testing patterns and disease burden observed in our recent study5. The transmission of respiratory viruses is influenced by climate factors. Previous studies have reported that the epidemiology of RSV varies across climatic regions in WA9. Moreover, meteorological variables such as humidity and rainfall show a strong temporal association with the incidence of RSV and other respiratory viruses10. Incorporating these meteorological conditions into prediction models is crucial for producing accurate estimates of RSV and influenza hospitalizations, identifying under-ascertainment rates by routine testing, and enhancing utilization of findings. The predictors of testing in these different climate regions could vary; hence understanding the under-ascertainment separately in each region is important.

Study population

We included children < 5 years of age born in WA between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2021 who were admitted to hospital for any diagnosis. Children were followed from birth until 31 December 2021 (date of censoring) or the date of death, whichever occurred earlier. A child could have more than one hospitalization episode and multiple RSV or influenza virus infections during the follow up period. We excluded children born outside WA who were hospitalized in one of the centers.

Data sources

Data were derived from the Respiratory Infection Data Linkage platform, previously described11, utilizing whole-of-population–based linked health data from the WA Department of Health. The birth cohort included Birth and Death registers, Midwives Notification. We obtained morbidity data from the Hospital Morbidity Data Collection (HMDC) and microbiological data from the PathWest Laboratory Medicine (PathWest) Respiratory Pathogens Surveillance database. We extracted RSV and influenza laboratory testing data from PathWest for all children tested for RSV or influenza (positive and negative results) using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) between 1 January 2010 to 31 December 202112.

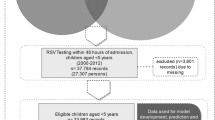

Geographical location was determined using postcode of residence at the time of hospital admission. For those children with no hospitalization records, the postcode of residence at the time of birth was used to assign the denominator cohort to each of the three climatic regions. Children residing outside of WA were excluded from analysis and inter-hospital transfers collapsed. Microbiological testing data were linked with hospitalization records with the date of specimen collection being within 4 days either side of the date of hospital admission (Fig. 1). A new RSV or influenza-associated hospitalization was defined as an RSV- or influenza-positive admission occurring more than 14 days after the prior confirmed hospitalization, and repeat tests within this period were excluded13,14. Bronchiolitis ICD diagnosis was limited to children two years of age or younger, as most of the disease occurs in this age group and management guidelines are defined for young children15.

Flowchart of the true RSV and influenza prediction study. The data sources presented in the figure are for development and validation of the prediction model as well as estimating the true incidence rates of RSV and influenza. HMDC, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection; PCR, Polymerase Chain Reaction; RSV, Respiratory Syncytial Virus.

Statistical analysis

Model development

To develop and validate the performance of the prediction model, we employed a logistic regression framework. We first identified children who had RSV or influenza testing using PathWest data and linked to hospitalization, and used this data to identify the predictors of RSV and influenza virus positivity (outcomes).

The selection of the minimum set of predictor variables was informed by developing Directed Acyclic Graphs (Supplementary Fig. S2), using DAGitty version 3.1, and illustrated the association between outcome and predictor variables16. DAGs are valuable tools for visualizing and understanding causal relationships between multiple predictors and outcome variables. DAGitty enhances variable selection by enabling the identification and mapping of proximal, intermediate and distal factors based on their causal proximity to the outcome variable16,17. We included an initial set of 27 predictor variables and computed the backward stepwise multiple logistic regression model separately for each climatic region (southern temperate, northern tropical, and central desert regions) for RSV and influenza positivity (6 models in total), with a cutoff probability of 0.2 for variable removal18. We included ICD–coded diagnoses for respiratory viral illnesses including bronchiolitis, acute bronchitis, and pneumonia (Table S1).

Model validation

The performance of the model in predicting RSV or influenza virus–positive hospitalization was assessed using discrimination and calibration measures19,20. Model discrimination was evaluated by computing tenfold cross-validated area under the receiver operating characteristics (cvAUROC) curve, which provides the opportunity to evaluate model performance across multiple thresholds, making this method preferred for this study20,21,22. Additionally, model calibration was graphically evaluated using internal calibration belts with a corresponding test statistic; a P-value ≥ 0.05 indicated good calibration23.

The best performing predictive model was used to estimate predicted probabilities of RSV and influenza positivity and the coefficients were applied to all hospitalizations, with or without viral laboratory testing, to compute the predicted burden of RSV- and influenza-associated hospitalizations. Predicted RSV and influenza cases were determined using cutoff values derived from a list of predicted probabilities that provide the maximum percentage of correctly classified RSV– and influenza–associated hospitalizations, while maximizing sensitivity and specificity (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). Depending on the climate region and type of virus, different cutoff values were used. A predicted case of RSV or influenza hospitalization was defined as a child with predicted probabilities equal to or above the cutoff value for that specific virus and region.

Laboratory-confirmed and true incidence of influenza and RSV

We computed the incidence rates of RSV and influenza using survival analysis techniques, allowing for multiple hospitalizations and viral infections per child. The denominator population was the birth cohort of children born in each climate region of WA using the postcode at birth, and calculated using person-time at risk (PTAR). PTAR was computed from the date of birth to the date of death, age 5 years, time of hospitalization for RSV or influenza, or December 31, 2021, whichever happened first. Predicted and ‘true’ incidence rates were estimated for the years 2010 to 2019. We excluded the year 2020 and 2021 due to the significant drop in RSV and influenza incidence and hospitalization burden during the COVID-19 pandemic, as the altered epidemiology of these viruses did not allow us to provide reliable disease burden predictions24,25. Incidence rates for RSV were expressed per 1,000 child–years, and influenza incidence rates were reported per 100,000 child–years for interpretation and comparability with existing literature.

Under-ascertainment fraction

The under-ascertainment fraction of RSV and influenza incidence rates was calculated as the percentage difference between the ‘true’ incidence rate and the laboratory-confirmed incidence rate. A true case of RSV- and influenza-positive hospitalization was defined as laboratory-confirmed case (for children who had PCR tests) and predicted cases (for those not tested for RSV or influenza). True incidence rate of RSV or influenza hospitalization was computed as laboratory–confirmed cases plus predicted cases for those not tested per person-time at risk.

Transparency of reporting

This study followed the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) statement, which is used to standardize the development and validation reports of prediction models (Supplementary Table 4)26.

Results

Characteristics of the study cohort

Our cohort included 257,960 children, born in WA between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2021. From 466,037 hospitalizations in those aged < 5 years 33,106 were tested for RSV (23.4% positive) and 33,511 were tested for influenza (3.6% positive). Figure 1 presents the detailed participant selection, model development and validation process. The majority of hospitalizations were from southern temperate regions (82.9%, N = 27,439 RSV and 83%, N = 27,818 influenza). In northern tropical areas, 59% of RSV- and influenza-tested hospitalizations were of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin (Table 1).

RSV and influenza hospitalizations prediction models by climate region

Six prediction models were developed for each virus and region. RSV positivity was strongly associated with unspecified ALRI (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 3.70, 95% CI 3.09–4.40, southern temperate region), viral pneumonia (aOR 4.29, 95% CI 2.12–8.68), and bronchiolitis (aOR 8.74, 95% CI 6.57–11.54). For the influenza, an ICD-coded influenza diagnosis was the strongest predictor of laboratory-confirmed hospitalization (aOR 288.93, 95% CI 118.80–702.72, northern tropical region) (Supplementary Tables 5–10).

The tenfold cross-validated cvAUROC indicated a reliable predictive performance of the logistic regression models. For RSV, cvAUROC was 87% in the southern temperate, 77% in the northern tropical, and 84% in the central desert regions (Fig. 2a). Influenza models also demonstrated high accuracy: 92.5% in southern temperate regions, 90.0% in northern tropical, and 94.1% in the central desert regions (Fig. 2b). Model calibration belt graphs showed excellent agreement between observed and predicted RSV and influenza hospitalizations (Supplementary Figs. 3–8).

Ten-fold cross-validated, area under the receiver operating characteristics (cvAUROC) curve for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) (a) and influenza (b) prediction models in three climatic regions. The columns represent climatic regions namely southern temperate (first column), northern tropical (center column), and central desert (right column) regions. The figures’ lines represent the mean cvAUROC (solid red line) and cvAUROC for individual cut off values (dotted lines).

Under-ascertainment of RSV- and influenza-positive hospitalization burden

The true incidence rate of RSV–associated hospitalizations was higher in young infants compared to children 24–59 months of age (20 vs. 1.29 per 1000 child–years in the southern temperate regions) and higher in regional areas (36 vs. 20 per 1000 child–years in the central desert than in the southern temperate region for infants). The under–ascertainment fraction of RSV–positive hospitalizations in infants ranged from 45% in the central desert to 69% in northern tropical regions (Table 2).

The true incidence rate of influenza hospitalizations in infants was also higher in regional areas, with a rate of 426 (333.18–543.86) per 100,000 child–years in northern tropical areas compared with 144 (131.09–159.05) per 100,000 child–years in southern temperate regions. The true incidence of influenza–associated hospitalizations was 34–52% higher than observed hospitalizations (Table 2).

Incidence of RSV and influenza by selected characteristics

We found higher incidence rates of both laboratory–confirmed and true RSV and influenza–associated hospitalizations in children born preterm, and in Aboriginal children. True RSV hospitalization rate was higher in preterm than term children (125 vs. 45 per 1000 child–years in northern tropical region). The ‘true’ incidence rate of influenza–associated hospitalizations were higher in preterm children < 32 weeks of gestational age (3577.48 vs. 916.69 per 100,000 child–years in northern tropical areas). The detailed incidence rates of RSV- and influenza-associated hospitalization is presented in Table 3.

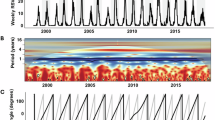

Incidence of RSV and influenza by epidemic week

In southern temperate and central desert regions, both predicted and laboratory-confirmed RSV incidence showed a seasonal pattern with a peak between July and August of each year. The predicted incidence of RSV in southern temperate regions peaked at 200 per 1000 child-years in 2012 and 150 per 1000 child-years in 2019. In northern tropical areas, no seasonal pattern in RSV incidence was observed, unlike the southern and central desert regions (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10). The highest incidence rate of influenza was observed in 2019, with predicted rates of 6,189 per 100,000 child–years in southern temperate regions and 31,430 per 100,000 child–years in the central desert regions (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12).

Discussion

We developed prediction models of RSV and influenza hospitalizations using multivariable logistic regression models for three climatic regions of WA, including northern tropical, central desert, and southern temperate regions to estimate the ‘true’ burden. Our prediction models demonstrated an excellent accuracy, ranging from 77 to 87% for RSV and 90–94% for influenza across different regions. RSV incidence rates were higher in young infants across all climatic regions, with children < 3 months experiencing rates between 39 and 60 per 1000 child–years. The true incidence rates of RSV and influenza hospitalizations in children < 12 months were highest in regional areas, with RSV rates as high as 37 per 1000 child-years and influenza rates up to 445 per 100,000 child-years in the central desert region. The model-predicted burden of RSV (45– 69%) and influenza (34–52%)-associated hospitalizations was significantly higher than laboratory-confirmed rates, with the highest under-ascertainment fraction in the northern tropical areas.

The logistic regression models demonstrated reliable accuracy for prediction of both RSV and influenza hospitalizations across different regions of WA, as indicated by the tenfold cross-validated, cvAUROC values and calibration belt graphs27. These findings suggest that the models are well-suited for estimating the true burden of RSV- and influenza-associated hospitalizations in both metropolitan and regional settings, and provide valuable tools for planning intervention strategies as also validated in other studies28,29. The development and validation of these prediction models to estimate the respiratory viral hospitalizations in different geographical settings is supported by our recent findings highlighting the differing viral testing patterns across diverse climate regions, which influence the epidemiological trends of these viruses5.

The higher incidence rate of RSV in younger infants indicates the significant burden of severe RSV disease in this age group, leading to increased hospitalizations rates. The findings underscore the necessity for targeted prevention strategies to protect infants, and enhanced testing to prevent severe outcomes. The findings from this study are consistent with epidemiological patterns of RSV and influenza reported in other Australian studies30. However, because we used prediction models and estimated the true hospitalization burden, our estimated hospitalization rates are significantly higher, pointing to previous rates being underestimated. Our model-predicted estimates of RSV and influenza hospitalizations aligned with findings from studies in other regions31,32, reinforcing the potential of such prediction models to precisely estimate the burden of respiratory virus hospitalizations across diverse populations, climatic conditions and socioeconomic contexts. With the recent introduction of RSV immunization program using a monoclonal antibody nirsevimab in WA and RSV maternal vaccination expected to be made available in 2025, these findings will be valuable to the prioritization and increased vaccination coverage of the most affected age group. The findings will also have vital contributions for future real-time evaluations of the impact of the prophylaxis in preventing severe RSV–associated ALRI hospitalizations.

The higher under-ascertainment fraction in RSV and influenza–associated hospitalizations, especially in the northern tropical regions, suggests that many cases are missed by routine testing in the hospital setting33. This is likely due to factors such as access to healthcare and lower health-seeking behavior, as highlighted in previous studies5,7,31. Higher under-ascertainment fractions also suggest the need for enhanced routine microbiological surveillance to better capture these viral infections to indicate the actual disease burden. This also underlines the critical importance of utilizing prediction models to estimate the true hospitalization burden for evidence-based decision making28,34. Higher hospitalization rates and under–ascertainment burden of RSV and influenza in regional areas might be related to socio-economic disparities, higher rates of preterm births, larger proportion of Aboriginal children (who bear a higher rate of both infections), and environmental factors that contribute to their susceptibility to severe viral respiratory infections. Addressing these disparities needs targeted interventions to reduce the burden of RSV and influenza hospitalizations in regional areas30,33.

The discrepancy between laboratory-confirmed and model-predicted incidence rates could be due to the low testing rates in children hospitalized for multiple causes. Our previous study showed the testing rates for respiratory viruses in the tertiary care centers were suboptimal, leading to lower incidence rates of RSV- and influenza-associated hospitalizations5, compared with the model-predicted rates. Another possible reason could be the coverage of testing by the public laboratory owing to testing from private laboratory. This study used public testing data only due to accessibility of the data; although PathWest is the major contributor to most of the laboratory testing in WA35, there is an increasing contribution of the private testing sector and some laboratory-confirmed cases from the private laboratory might not have been be included.

The seasonal pattern observed in RSV incidence in the southern and central regions of WA aligns with well-documented trends of RSV peaking during the winter months9. However, the lack of a clear seasonal pattern in northern tropical regions could be related to climatic factors, as tropical regions often exhibit more year-round viral circulation due to their warmer and more humid conditions10 and movement of people from subtropical areas to the North for local tourism. Understanding the varying seasonal patterns of RSV and influenza across different climate regions is essential for the localized decision-making to align immunization programs for both RSV and influenza to local virus circulation periods.

One of the strengths of our study is that we estimated the true incidence rate of influenza–associated hospitalizations by developing and validating a prediction model for different climate regions, which has not been addressed by previous studies. Additionally, we were able to produce RSV and influenza under-ascertainment rates by geographical location, by addressing variations in meteorological, healthcare access, availability of paediatricians, and healthcare-seeking behavior. These factors play a crucial role in the epidemiology of both RSV and influenza, making the laboratory–confirmed and predicted estimates more reliable for localized decision-making. However, this study also has a number of limitations. First, we were not able to predict for the years 2020 and 2021 due to the disruption caused by COVID, making estimates from laboratory testing data during this period unreliable. Second, the study utilized microbiological data from the public pathology provider (PathWest) due to availability of data. Although PathWest is still the major provider of laboratory tests in metropolitan and regional areas, there is an increasing contribution from the private laboratory testing sector,5 resulting in less virus-confirmed hospitalizations. However, this limitation further strengthens the rationale and utility of our prediction models.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight significant geographic, seasonal, and demographic disparities in the incidence of RSV- and influenza-associated hospitalizations among young children in WA. This study also highlights a substantial under-ascertainment in RSV- and influenza-associated hospitalizations by routine laboratory testing. The findings will have a valuable contribution to prioritize children for RSV immunization using nirsevimab and maternal vaccination and to align RSV and influenza immunization to local RSV and influenza circulation periods. Targeted interventions such as increased vaccination coverage, enhanced testing and early treatment strategies could help reduce the burden of RSV- and influenza-hospitalizations, particularly among infants, Aboriginal children, and preterm infants, where incidence rates are higher. Prediction models have proven to be accurate to estimate the true burden of influenza across different climatic regions.

Data availability

All data used to develop and validate the prediction model or estimates generated in this study are included in this published article and its supplementary material. The data within the WA Respiratory Infections Data Linkage Platform cannot be shared publicly. Access to the data is subject to approval by relevant data custodians and provided by WA Data Linkage Services at the WA Department of Health (https://www.datalinkageservices.health.wa.gov.au/contact-us/). The use of the data is restricted to named researchers only on the approved ethics protocols.

References

Li, Y. et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 399, 2047–2064. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00478-0 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Global burden of respiratory infections associated with seasonal influenza in children under 5 years in 2018: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 8, e497–e510. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30545-5 (2020).

Saravanos, G. L. et al. Respiratory syncytial virus-associated hospitalisations in Australia, 2006–2015. Med J Aust 210, 447–453. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50159 (2019).

Lim, F. J., Blyth, C. C., Fathima, P., de Klerk, N. & Moore, H. C. Record linkage study of the pathogen-specific burden of respiratory viruses in children. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 11, 502–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/irv.12508 (2017).

Taye, B. W. et al. Respiratory viral testing rate patterns in young children attending tertiary care across western Australia: A population-based birth cohort study. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 18, e70005. https://doi.org/10.1111/irv.70005 (2024).

Moore, H. C. et al. Assessing the burden of laboratory-confirmed respiratory syncytial virus infection in a population cohort of Australian children through record linkage. J Infect Dis 222, 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa058 (2020).

Gebremedhin, A. T., Hogan, A. B., Blyth, C. C., Glass, K. & Moore, H. C. Developing a prediction model to estimate the true burden of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in hospitalised children in Western Australia. Sci. Rep. 12, 332. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04080-3 (2022).

Australian Bureau of Statistics. National, State and Territory Population. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/national-state-and-territory-population/latest-release (September 2023 ).

Hogan, A. B. et al. Time series analysis of RSV and bronchiolitis seasonality in temperate and tropical Western Australia. Epidemics 16, 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epidem.2016.05.001 (2016).

Morley, C., Grimwood, K., Maloney, S. & Ware, R. S. Meteorological factors and respiratory syncytial virus seasonality in subtropical Australia. Epidemiol Infect 146, 757–762. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268818000614 (2018).

Sarna, M. M. et al. Cohort profile: A population-based record linkage platform to address critical epidemiological evidence gaps in respiratory syncytial virus and other respiratory infections. Int. J. Popul. Data Sci. 9, 2376 (2024).

PathWest Laboratory Medicine Western Australia. PathWest Annual Report 2022–23 (2023).

Price, O., Birrell, F. A., Mifsud, E. J. & Sullivan, S. G. Epidemiology of repeat influenza infection in Queensland, Australia, 2005–2017. Epidemiol. Infect. 150, e144. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268822001157 (2022).

Carrat, F. et al. Time lines of infection and disease in human influenza: a review of volunteer challenge studies. Am J Epidemiol 167, 775–785. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwm375 (2008).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Bronchiolitis in Children: Diagnosis and Management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2021 Aug 9. (NICE Guideline, No. 9.) (2021).

Textor, J., Hardt, J. & Knuppel, S. DAGitty: A graphical tool for analyzing causal diagrams. Epidemiology 22, 745. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e318225c2be (2011).

Byeon, S. & Lee, W. Directed acyclic graphs for clinical research: a tutorial. J. Minim. Invasive Surg. 26, 97–107. https://doi.org/10.7602/jmis.2023.26.3.97 (2023).

Chowdhury, M. Z. I. & Turin, T. C. Variable selection strategies and its importance in clinical prediction modelling. Fam. Med. Community Health 8, e000262. https://doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2019-000262 (2020).

Tan, Y. L., Saffari, S. E. & Tan, N. C. K. A framework for evaluating predictive models. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 150, 188–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.08.005 (2022).

Steyerberg, E. W. et al. Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology 21, 128–138. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c30fb2 (2010).

Cabot, J. H. & Ross, E. G. Evaluating prediction model performance. Surgery 174, 723–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2023.05.023 (2023).

Luque-Fernandez, M. A., Redondo-Sánchez, D. & Maringe, C. cvauroc: Command to compute cross-validated area under the curve for ROC analysis after predictive modeling for binary outcomes. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata 19, 615–625. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867x19874237 (2019).

Nattino, G., Lemeshow, S., Phillips, G., Finazzi, S. & Bertolini, G. Assessing the calibration of dichotomous outcome models with the calibration belt. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata 17, 1003–1014. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867x1801700414 (2018).

Cong, B. et al. Changes in the global hospitalisation burden of respiratory syncytial virus in young children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 24, 361–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00630-8 (2024).

Saravanos, G. L. et al. RSV Epidemiology in Australia Before and During COVID-19. Pediatrics 149, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-053537 (2022).

Collins, G. S., Reitsma, J. B., Altman, D. G. & Moons, K. G. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. TRIPOD group. Circulation 131, 211–219. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.114.014508 (2015).

Mandrekar, J. N. Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. J. Thorac. Oncol. 5, 1315–1316. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ec173d (2010).

Shipe, M. E., Deppen, S. A., Farjah, F. & Grogan, E. L. Developing prediction models for clinical use using logistic regression: An overview. J. Thorac. Dis. 11, S574–S584. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2019.01.25 (2019).

Steyerberg, E. Clinical prediction models: A practical approach to development, validation, and updating. 19 (2009).

Homaira, N. et al. High burden of RSV hospitalization in very young children: A data linkage study. Epidemiol. Infect. 144, 1612–1621. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268815003015 (2016).

Nazareno, A. L. et al. Modelled estimates of hospitalisations attributable to respiratory syncytial virus and influenza in Australia, 2009–2017. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 16, 1082–1090. https://doi.org/10.1111/irv.13003 (2022).

Fonseca, M. J., Hagenaars, S., Bangert, M., Flach, C. & Hudson, R. D. A. Respiratory syncytial virus hospital admission rates and patients’ characteristics before the age of 2 years in England, 2015–2019. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 43, 909–915. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000004467 (2024).

Martinon-Torres, F. et al. Clinical and economic hospital burden of acute respiratory infection (BARI) due to respiratory syncytial virus in Spanish children, 2015–2018. BMC Infect. Dis. 23, 385. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08358-x (2023).

Rankin, D. A. et al. Diagnostic models predicting paediatric viral acute respiratory infections: A systematic review. BMJ Open 13, e067878. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-067878 (2023).

PathWest Laboratory Medicine WA. PathWest Annual Report 2022–23 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Sanofi–Aventis Australia through the Respiratory Viral Testing Patterns Across Western Australia project (#FLU00200). The funders had no role in the design, analysis or interpretation of the data used to produce this publication. The authors acknowledge the Western Australian Data Linkage Services and relevant Data Custodians of Births and Deaths Registry, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection, Midwives Notification System, and PathWest Laboratory Medicine for providing the study data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation, methodology: BT, HM; Data management: BT, MS, HL; Data curation, model development and validation, formal analysis: BT; Preparation of images, maps and figures: BT; Writing original draft: BT; Manuscript review and update: BT, MS, HL, AL, CM, RM, PR, CB, & HM; Funding: HM. All the authors reviewed the manuscript and approved it for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the WA Department of Health Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC RGS Reference: 4675). Due to retrospective nature of the study informed consent was waived by the WA Department of Health Human Research Ethics Committee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Taye, B., Levy, A., Sarna, M. et al. Predicting regional and temporal incidence of RSV and influenza hospitalizations in a birth cohort of young Australian children. Sci Rep 15, 31369 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16802-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16802-y