Abstract

5G and 6G development aim to fulfil very low latency, low energy consumption, and great computation ability. In the present era, the number of devices is increasing daily, which requires more communication and computation. Device-to-device (D2D), relay server, and mobile edge computing (MEC) systems were developed to meet these objectives. By employing the Constraint Based Multi-Dimensional Flux Balance Analysis (CBMDFBA) approach, this work aims to provide optimized overall energy consumption. Each device in this system can partially offload tasks to the Relay Edge Server (RES), Edge Server (ES), and adjacent mobile helper. Reinforcement learning is utilized to optimize the Signal’s signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), decreasing transmission power between the helper, relay, and edge server. By employing CBMDFBA for path optimization, the approach reduces overall energy usage. In comparison to (1) Resource allocations using Q learning with considering parameter throughput-RA(QL-Munkres-TH), (2) Resource allocations using Q learning with considering parameter distance-RA(QL-Munkres-Dist), and (3) Resource allocation with considering maximum power-RA(Max-Power), the suggested method reduces energy consumption by 83.26%, 86.01%, and 88.34%, respectively. A comparison of energy efficiency and fairness index is also evaluated. According to simulation findings, the suggested algorithm outperforms baseline systems in terms of system performance and energy efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The worldwide mobile application market was estimated to be worth United States Dollar 206.85 billion in 2022. It is projected to expand at a compound annual growth rate of 13.8% between 2023 and 2030 for applications like social networking, gaming, mobile health, fitness, entertainment, retail, and e-commerce1. These new applications required high processing power, large battery capacities, and quick reaction times2. Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) is a viable paradigm for addressing these applications by offering cloud computing capabilities inside radio access networks3,4. It is possible to enhance computing performance by optimizing latency and energy consumption. This is done by performing computation tasks on MEC servers near Mobile Devices (MDs)5. MEC technology is developing; research has been done to minimize long-term time delay and energy consumption6. MEC helps applications like mobile augmented reality, which require significant bandwidth, low latency, and enormous connectivity7. The success of edge computing systems depends on resource scheduling, which has increased academic interest in this area8. Furthermore, through multidisciplinary intersection and practice, edge computing can be substantially integrated with technology in other areas, such as artificial intelligence, blockchain, 6G, and digital twins, unleashing the potential for mutual benefit. Additionally, edge computing offers robust support for application scenarios, including digital advertising, retail industries, and online gaming. All have significantly altered our way of living, working, and learning9,10. Although MEC has reduced latency, real-time applications still have room for improvement11. Devices-to-Devices (D2D) communication offers a novel approach to mobile networking that enables data sharing among physically close devices. Mobile operators gather short-range messages by D2D communication, which enhances network performance and validates proximity-based services12. By using D2D relaying, users can relay data to others, significantly reducing costs for mobile network operators since each user equipment (UE) has the potential to function as a relay13. Information forecasting adds a new dimension to fully utilize MEC’s potential in addition to looking for extra physical resources for performance enhancement, such as the D2D paradigm and Intelligent Reflecting Surface (IRS)14. Much research has been done to enhance the performance of MEC-related D2D systems (MECRD2D). Integrating MECRD2D with machine learning (ML) techniques is another method to improve the system’s performance in the current scenario15. Ze et al.15 proposed a multiobjective algorithm to enhance energy consumption using Lyapunov optimization. Xinyuan et al.16 a deep reinforcement learning optimization was proposed to maximize the utility factor and power allocation. Zivi et al.17 proposed a joint optimization using Lyapunov and reinforcement learning to minimize the system’s latency by considering content sharing. Chankun et al.18 proposed an incentive-based task offloading for socially connected users to enhance the system’s performance and efficiency. Zhaocheng et al.19 proposed a potential game approach for task offloading to optimize the energy usage and latency parameters. According to the above study, it is clear that the number of devices is increasing regularly, which is expanding the load on edge servers (ES) and enhancing interference for D2D communication. With the increasing number of devices, the need for task offloading increases essentially to minimize the latency factor. Considering the system’s dynamic nature and time-varying resources, allocating resources in ultra-dense networks to meet low latency demand with lesser energy consumption is essential.

Contributions

-

A novel scenario that combines Relay Edge Server (RES), ES, and D2D to reduce energy consumption has been considered. Several cellular devices can use D2D links to partially offload their computational task to neighbouring devices, RES and ES based on optimized SNR and availability of resources..

-

A Constraint-Based Multi-Dimensional Flux Balance Analysis (CBMDFBA) algorithm has been developed to adapt the dynamic environment and optimal path utilization to reduce the task processing delay. All the devices participating in D2D communication generate a network similar to a metabolic network for D2D communication and achieve significant reductions in overall energy consumption and latency.

-

A genome-scale reconstruction of metabolic networks has been adopted in this paper, and proposed novel task computation and offloading algorithm is compared with conventional algorithms. The simulation results show that proposed algorithm performs better in ultra-dense networks.

Biggest advantage of dynamic flux balance analysis (DFBA) is computation efficiency with large network. In addition, it predict the best optimal path utilization under different conditions for transferring the data. DFBA is suitable in multi agent system with varying load over time.

Related work

Data can be exchanged among surrounding devices, using D2D communication. In 5G and 6G, applications require high data rates, low latency, and quality of service (QoS)-specific communication. In these situations, D2D aids in boosting system performance. D2D communication has been studied in the unlicensed spectrum from 1G to 3G; later, it occurred in the licensed spectrum20. To enhance the scope of D2D communication, Doppler et al.21 introduced a mode selection algorithm. For D2D communications with cellular traffic, a mode is allocated a shared or dedicated channel under this method. Liu et al.22 focused more on the procedures for evaluating the performance of long term evolution (LTE) and D2D communication applications, services, current prototypes, and trials. Mach et al.23 concentrated on inband D2D communication and provide sufficient information on interference control and D2D mode selection. Nomikos et al.24 gave overview about relay selection studies that increase packet latency and enhance several performance indicators, including throughput, power reduction, and outage probability. Asadi et al.25 discussed main challenges with D2D underlay communication are interference management and power control between D2D and cellular users. The interference problem in overlay D2D communication is avoided since cellular and D2D resources do not overlap. D2D uses devices to maximize system capacity, optimize resource usage, and improve data rates and latency26. Zheyuan et al.27 proposed a reinforcement learning optimization for task offloading to optimize the cost of the system.

Jiang et al.28 explained how the long-term total task computation delay is reduced by resource allocation and partial computation offloading in the shared spectrum. The scope is limited to a fixed task size. The average offloading benefits are maximized for all compute-intensive users in the network by Fang et al.29. However, there is a lack of discussion on individual parameters like latency and energy consumption. Xiao et al.30 optimized latency and energy usage jointly. Task offloading in both serial and parallel modes is taken into account. The analysis is performed on the static scenario. Jiawei et al.31 a Lyapunov optimization-based resource allocation scenario was proposed to balance communication and computing to enhance energy efficiency. Huang et al.32 suggested a delay-based utility function created for each user, and the offline platform profit maximization problem has been discussed. However, the system needs prior information on D2D resource availability. Garg A et al.33the cost factor is considered for evaluating the system’s performance using the price elasticity log-log model. However, the study finds a static latency constraint. Chen et al.34 employed a cache replacement scheme to decrease the network latency. Every MD is supposed to be aware of the stuff that is cached on the network. However, in this paper, only latency is taken into account. The impact on energy consumption is not discussed here. MDs with less processing capacity, the MEC server helps to perform computation offloading35. Power constraints are considered for response time, but overall energy consumption has not been discussed. C You et al.3 devloped a priority function which dependent on channel gains and regional computing power. The base station (BS) selects mobile users for offloading based on priority. However, the latency has not been considered in this paper. To encourage socially linked D2D users to move about to offload chores, Jiang et al.18 concentrated on creating an honest reward system. Patel R et al.36 considered a social awareness concept for resource allocation to optimize energy consumption. Li et al.11 introduced a proficient D2D-assisted MEC task computation and offloading architecture using deep reinforcement learning (DRL). In this paper, an energy constraint has been considered for offloading the task. A Decentralized Federated learning (DFL) approach is presented by authors in37 to reduce energy consumption. The parameter’s accuracy has been analyzed by maintaining privacy. Only the accuracy parameter is considered. The tabu search-based method selects links for a large-scale network with minimal computing complexity38. The dynamic scenario has not been considered in this paper. A non-convex optimization problem is designed to lower the energy consumption during communication39. The scope is limited for real-time applications where latency is the most critical parameter. Wei et al.40 proposed a software-defined network MEC architecture for Island IoT that uses tidal energy and D2D cooperation. The writers concentrated on a few islands remote from the mainland with increasing computing needs for environmental monitoring and navigation safety. Fan et al.41 suggested a hybrid technique that breaks down the optimization issue into more minor problems and uses a DRL based algorithm to solve the problem effectively. However, there is no discussion on overall energy consumption. MEC systems also function in dynamic environments with shifting network loads, mobile users, and fluctuating computing demands. In this paper, the dynamic nature of the metabolic network has been adapted. Metabolic networks provide redundancy and durability by carrying out several metabolic activities concurrently. This benefit is also considered for resource and relay allocation to distribute the load between RES, ES, and D2D. DFBA handled time-dependent adaptation very well.

It is apparent from the description above that optimizing computing and communication resources is the primary focus of MEC’s work. As the number of devices increases, the load on the edge server also increases. As per the above discussion, D2D technologies have been playing an essential role in providing computation resources to reduce the burden of edge servers. Due to high device density in small areas, there are a lot of challenges to delivering computation resources, as follows:

-

a.

Increasing computation load on edge server: Although the D2D MEC system helps reduce the computational load on ES, the high density of devices in small areas increases resource demands. To accommodate these demands without increasing load on ES is a challenge.

-

b.

Adaptable energy consumption and latency in a dynamic environment: Optimizing the distance between MDs and MHs while preserving system performance is necessary to reduce latency and energy consumption when more devices are in a condensed, tiny space.

-

c.

Interference among devices is high: I n a small, dense area, interference among devices is high. To allocate resources while managing interference is a challenge.

Table 1 displays the state of the art, Table 2 lists the symbols used in this article, and Table 3 lists the abbreviations utilized.

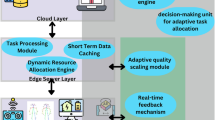

System model

In this work, task offloading in a small crowded area with RES, BS, ES and N number of UE is shown in figure-1. A MECRD2D system which consist RES for low computing task with N number of users, \(N=\{ 1,2,3,....,N\}\) and M number of MHs, \(M=\{ 1,2,3,....M\}\) for D2D communication. Many MDs can be served concurrently by an ES, and each MD can connect to BS via a cellular link. RES which is available in the middle on the top of the dense area for computation.

The entire bandwidth is divided into sub-channels among users in the network. Each MD can approach ES for task offloading depending on the size of the computation task and the availability of MHs. Because of MHs’ limited processing power, MD can only establish a link with one MH and conversely. MHs also can approach the RES directly for low-computation tasks to support other MDs. Each MH may get resources to one or many MDs for task offloading. Four computation offloading modes are: (1) Local computing- N users deal with computation tasks on their own; (2) D2D offloading, that is user N can offload the data to nearby MHs through D2D link; (3) Offloading through RES in case of low computation task if MHs are not available for offloading; and (4) Edge offloading, that is users offloads the computation tsk to edge server in case of high computation task.

MD handles local computation and offloads it to MHs, RES and ES for processing. Cellular links are used for offloading to ES to communicate offloaded tasks, and D2D links are used for MHs and RES. MHs are heterogeneous devices, such as tablets, laptops, and idle MDs, etc. The device’s function \(r(r \in N)\) is represented as a tuple\(\{ {t_s},{C_r},{T_L}\}\), where \({t_s}\) is size and \({C_{r,}}\) is computational cycles required by each bit. \({T_L}\) is task performance latency. MDs, MHs, RES, and ES computation resources are indicated by the variables\({f_{MD}}\), \({f_{MH}}\), \({f_{RES}}\) and \({f_{ES}}\) (CPU- cycles per sec), respectively. Task offloading can be done based on the user’s demand. Based on computation, offloading can be done in four ways with the help of MD’s itself, via D2D, via RES or via BS.

Local computation

If user r computes task locally, the time taken to complete the computation process is indicated as:

In the meantime, energy usage for local computing is given by33:

Where \({C_\Psi }\)is system capacitance, \({C_{r,}}\) is number of CPU cycles, \({t_s}\)is task size.

Equation 4, Eq. 5 are involving for local computing. In case of only local computing, total energy consumption will be equal to\(e_{r}^{{local}}\).

D2D offloading

If rth MD is unable to perform its task locally, it can still finish the computation by connecting to MH nearby via a D2D communication link. The data rate is define by:

Where B is channel width, \({p^t}\)is transmitted power (TR) and \({d_m}\)is distance from \({r_{th}}\) user to \({m_{th}}\) helper, \(\alpha\) is path-loss exponent and \({N_0}\)is noise power for every sub-channel. In this case TR \(\Upsilon _{r}^{{loacl}}+\Upsilon _{r}^{{help}}=1\). In this case \(\Upsilon _{r}^{{loacl}}\) is TR for local and \(\Upsilon _{r}^{{help}}\)TR for mobile helper.

Where \(R_{r}^{{D2D}}\)id D2D communication rate and \(t_{r}^{{D2D}}\)is time which include D2D computation and communication. \(e_{r}^{{D2D}}\)is the energy factor during D2D task offloading.

RES offloading

If rth MD is unable to perform its task locally with in a given time constraint and MH is not accessible near MD, then in this case computation can be done by RES which is available at the top of the dense area via relay. In this case TR \(\Upsilon _{r}^{{loacl}}+\Upsilon _{r}^{{RES}}=1\) and here \(\Upsilon _{r}^{{RES}}\)is TR for RES. The data rate is define as:

Where \({d_{res}}\)is physical distance from \({r_{th}}\) user to RES.

Where \({t_r}\) is task size for computation and \({t^{RES}}\)is the time for RES for communication and computation.

The total energy consumption is given by-

Edge offloading

If rth MD is unable to perform task locally in a given time constraint and MH is not accessible near MD. RES is also not available for computation and communication, then computation is performed by ES which is available in proximity of BS. Then TR is given by \(\Upsilon _{r}^{{loacl}}+\Upsilon _{r}^{{ES}}=1\).Here \(\Upsilon _{r}^{{ES}}\) is the TR for ES.

Where \({t^{ES}}\)is computation time for RES.

Total energy is calculated by-

Local computing, D2D, RES and ES offloading

In this case TR is given by \(\Upsilon _{r}^{{loacl}}+\Upsilon _{r}^{{help}}+{\Upsilon ^{RES}}+\Upsilon _{r}^{{ES}}=1\). And total energy is calculated as

Local computation latency depends upon computation resources, \({C_r}\)and \({t_s}\). Latency also depends upon computation and communication through D2D, RES and ES. In the same manner, the energy consumption depends upon the parameters of computation resources, latency, task size and number of calculation cycles needed, \({C_\Psi }\)and transmitted power. Users may notice a reduced offloading distance with D2D offloading as opposed to relay edge server and edge offloading. Nevertheless, the neighbors’ processing power is inferior to RES and ES clouds. Additionally, if multiple users select the same offloading mode, D2D offloading, RES offloading, or edge offloading, they will have a negative experience because of a significant resource dispute. Considering these factors, we have to optimize the above parameters for lower latency and power consumption.

Problem formulation

The goal of this paper is to reduce energy usage. Following is a mathematical representation of the problem:

The task can be divided among local, MHs, RES, and ES according to constraint (17a1). MD’s finite computational capacity is ensured by constraint (17a2). The constraints (17a2), (17a3), (17a4), and (17a5) indicate that TR to MH, RES, or ES must be between 0 and 1, meaning that completed tasks can’t be assigned to MH, RES, or ES to maximize resource usage. Limitation (17a6) ensures that no more than one helper can handle MD’s load. The computation capabilities of the helper device, RES device, and ES is guaranteed by constraint (17a7). The calculation time is restricted by constraint (17a8) to be smaller than the delay restriction.

Decomposition of the problem

Optimizing total energy consumption is the primary goal of \({P_{r1}}\)‘s solution. \({P_{r1}}\) can be divided into two separate problems with optimization of transmission power and path optimization.

The transmission power between the helper, relay, and edge server is optimized to reduce SNR and energy consumption. The mathematical expression to optimize power can be defined as:

The problem \({P_{r2}}\) is optimized by optimizing transmission power to the relay, RES and ES. The constraint used in above problem are defined as:

Constraint (18a1) restricts the D2D communication between two devices if the distance between two devices is higher than\(d_{{\hbox{min} }}^{r}\). It can be between MD and helper or MD and RES. All users have equal access to the bandwidth, according to constraint (18a2).

After obtaining the optimized transmission power for solving \({P_{r2}}\), further energy is optimized by path optimization. It is performed by optimizing overall path between MDs, RES, and ES. For both resource and relay allocation, here we used CBMDFBA. Mathematically, problem \({P_{r3}}\), a component of \({P_{r1}}\), can be expressed as follows:

By using maximum computing capacity of local device, the TR is optimized. Following formula can be used to determine TR between MH and local computing:

\(R_{r}^{{D2D}}\)is already calculated in Eq. (3). The work is split up between ES, RES, MH and MD to meet the time constraints. As stated in Eq. (20) TR for local computing is a function of parameters \({T_{tolerance}}\), \({f_{MD}}\), \({t_s}\) and \(Cr\). Apart from this task, the D2D connection data transfer rate also affects the splitting ratio for MH, as shown by Eq. (21). The edge server receives the remaining task to be processed. Equation (22) is used to calculate the job splitting ratio for the edge server.

Propose solution-constraint based multi-dimensional flux balance analysis (CBMDFBA)

The advantages of FBA is adopted in the proposed work. Limitation of FBA is improved by making it as a multi-dimensional with the help of reinforcement learning. DFBA model formulation combines mass conservation laws applied to the extracellular environment with genome-scale metabolic models. To enhance artificial microbial communities for various biotechnological applications, a novel framework named DFBA is being constructed42. This DFBA concept has been adapted in this paper to optimize the total energy consumption in D2D communication. For using dynamic FBA in D2D communication, we designed it as a non-linear programing with the help of different constraint. A stoichiometry matrix is updated based on optimized SNR. In stoichiometric matrix, each row represented by network link and each column is represented by routing of data transmission. Considering the abovementioned condition, we propose a CBMDFBA-based energy optimization for D2D communication. By continually resolving optimization issues under shifting network conditions, CBMDFBA makes it possible to allocate network resources dynamically. DFBA can aid in effectively balancing data flows in D2D communication, which involves devices communicating directly without first passing via a base station. With the aid of improving SNR for transmitting devices, CBMDFBA can dynamically predict energy usage and optimize power levels while maintaining network stability.

In this paper, we have compared our proposed work with RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist), and RA(Max-Power). In RA(QL-Munkres-TH), resource allocation has been done using Q-learning and Munkres algorithm. In this, throughput has been considered as a constraint for optimization. The second comparison has been done with RA(QL-Munkres-Dist). Q-learning has been integrated with Munkres, and the distance between seeking users has been considered. A third comparison has been done with RA(Max-Power). In this resource, allocation has been done based on maximum power. All three algorithms have been compared with the proposed CBMDFBA.

In proposed approach, Stoichiometric Matrix S is a \(m \times n\)matrix, which contains m number of resources and n number of resource allocation strategies and represented by:

Where \({s_{i,j}}\)represents the Stoichiometric Matrix coefficient of the \({i^{th}}\)metabolite in the \({j^{th}}\)reaction. Flux vector \(v(t)\) represents the data rate at which they are allocated for resource allocation. The dynamics of state transitions in DFBA may be expressed as follows:

where fluxes to state variables are mapped by the stoichiometric matrix S. The flux vector, denoted by\(v(t)\), is equivalent to data rate allocations in D2D. One way to explain DFBA-based optimization issue for MECD2D networks’ power allocation and rate control is as follows:

Here \({R_i}\)is data rate for \({i^{th}}\)MH and constraint defined as:

For dynamic environment \(S.V\)is not equal to zero. FBA for dynamic environment is shown in Fig. 2. Flux Vector V is a function of SNR and distance.

Simulations are also used to validate empirical convergence: average Q-values settle after a certain number of repetitions.

Computational complexity and convergence

-

1.

For algorithm-1: Algorithm 1 is include the number of iteration, number of users and number of actions. So computational complexity for the algorithm 1 will be\(O(M \times N \times T)\). If M and T are constant, in that case it will be simply\(O(N)\). This paper uses the resource allocation technique based on Q-learning that guarantees convergence under standard reinforcement learning assumptions. According to Watkins et al.43the Q-values converge to the optimal policy as state and action spaces are finite, and we choose an epsilon-greedy policy for adequate exploration.

-

2.

For algorithm-2: Algorithm 2 includes, adjacency matrix formation and stoichiometry matrix used for CBMDFBA. The path optimization has been done with algorithm 2. For initialization and adjacency matrix, complexity is\(O({N^2})\). The stoichiometry matrix formation is done with the help of adjacency matrix and eigen matrix calculation, so it has computation complexity\(O({N^3})\). The optimized SNR from algorithm 1 is using in algorithm 2. So total complexity has been calculated as\(O(M \times N \times T)+O({N^3})\). In addition to a flux-balancing concept, the CBMDFBA technique employs an exhaustive search across all possible task-to-helper mappings. Because the method is deterministic and the solution space is small, it converges after assessing every conceivable configuration, ensuring optimal task allocation within the specified boundaries.

Algorithms used

Q learning

The agent-environment interaction is taken into account by algorithm 1. In this algorithm discrete power is allocated as an action and the maximum SNR is achieved by using Bellman’s equation which is as follows42:

Where i is number of iteration, \({S_{i,}}\) is state, \({A_i}\)is action, \(\psi \in [0,1]\) is the learning rate, \({\phi _{i+1}}\)is the future reward, \({P_a}\)is any action that a state could take, and \(\delta \in [0,1]\) is the discount factor.

Algorithm for CBMDFBA

In algorithm 2, CBMDFBA is shown. Initialization of inputs, such as the position of the users inside the area, length and height of the dense area, transmission power, data rate, and data size, has been done. At the output, we get an optimized path in a matrix. The adjacency matrix for CBMDFBA is calculated by finding the distance between MDs and MHs. After that, the Stoichiometry matrix has been calculated for path optimization. This algorithm uses optimized SNR, which is coming from algorithm 1, Eq. no. (28), to make the algorithm multi-dimensional. In the end, latency and overall energy consumption are calculated.

Simulation results and discussions

This section showcases the accomplishment of the suggested approach CBMDFBA and validates it using simulation data. Overall, energy usage and latency parameters concerning MDs and MHs are calculated. The simulation setup described in the section below is used to test the effectiveness of CBMDFBA.

Simulation setup

The geographical distribution of MDs is uniform inside the small dense area. Parameters used in simulation are shown in Table 4. BS is situated at a distance of 200 m from the area. 72 MDs are randomly located inside the small dense area of 20 m in length and 4.5 m in width. Out of 72 MDs, up to 20 available MHs can be selected randomly for computation offloading. For D2D connectivity, range for communication with MHs is 5 m. For both MDs and MHs, the maximum transmit power \({P_{\hbox{max} }}\) is 24 dBm. The network can tolerate a latency of 0.2 s. MDs and MHs have the following set of compute resources: \({f_{MD}}\)∈1 × 109 CPU cycles/sec and \({f_{MH}}\)∈1 × 109 CPU cycles/sec. For RES computation resource \({f_{RES}}\)∈15 × 109 CPU cycles/sec and for ES is \({f_{ES}}\) ∈40 × 109 CPU cycles/sec. To compute 1-bit task,\(Cr\) ranges from 1500 to 2000. The devices effective system capacitance is \({C_\Psi }\) =10−28. The channel noise and path loss exponent are \({N_0}\) = −174 dBm and \(\alpha\) = 4 respectively. The data size for each user with high computational demands is uniformly distributed in \({L_r}\) ∈ [1 2.5] Mbits. MATLAB 2023a version was used to perform simulation outcomes. The system features Intel(R) Core (TM) i5-8250 CPU running at 1.6 GHz, 16 GB RAM, and 64-bit Windows 11.

Simulation results

The results of various computing demands are discussed in this section. The performance is measured based on two parameters: latency and energy consumption. Total energy consumption is calculated by Eq. (16). Equations (1), (4), and (5). The difference in latency is vast between the proposed work and the existing work. So, latency is plotted on a logarithmic scale to differentiate the simulation results.

In Figs. 3 and 72 users have been considered when considering the ideal case of a dense area. And out of 72 users, five users are seeking task computation. A total of four schemes have been compared in Fig. 3 name as (1) Resource allocations using Q learning with considering parameter throughput- RA(QL-Munkres-TH), (2) Resource allocations using Q learning with considering parameter distance- RA(QL-Munkres-Dist), (3) Resource allocation with considering maximum power- RA(Max-Power), (4) Proposed scheme for resource allocation using CBMDFBA. The results have shown that the latency calculated in Fig. 3(a) for 1Mbps task size in the proposed scheme is reduced by 99.87% in comparison with RA(QL-Munkres-TH) scheme, 99.89% in comparison with RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) scheme and 99.73% in comparison with RA(Max-Power) scheme. The average latency has been calculated at 2.13ms only in the proposed scheme CBMDFBA. In Fig. 3(a), it is clear that the proposed algorithm is showing that the latency is reducing with increasing the number of users. In Fig. 3(b), the task size has been considered 1.5Mbps, and it found that 99.86% has reduced the latency, 99.88%, and 99.71%, respectively, to the scheme RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and RA(Max-Power). The average latency has been calculated at 3.75ms only in the proposed scheme CBMDFBA. Figure 3(b) shows that the proposed method decreases latency as the number of user increases. In addition, it is performing well, even with an increment in task size.

Figure 3(c) shows that when compared to schemes RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and RA(Max-Power) with task size of 2Mbps resulted in a 99.87%, 99.89%, and 99.74% reduction in latency. According to the proposed CBMDFBA scheme, the average latency is 4.34 ms. It also indicates that the proposed algorithm’s latency is decreasing with increasing users. Figure 3(d) demonstrates that a task size of 2.5Mbps led to a 99.84%, 99.87%, and 99.68% reduction in latency when compared to schemes RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and RA(Max-Power). The average delay, as per the proposed CBMDFBA scheme, is 6.69ms. Also, the latency is decreasing with the number of users.

In Fig. 4, Energy consumption is calculated, and simulation results are compared. In Fig. 4(a), the average energy consumption is 973.4 J for the proposed CBMDFBA scheme, which is 53.56% less than a comparison of scheme RA(QL-Munkres-TH). And 61.20% less in comparison with scheme RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and 67.67% less with scheme RA(Max-Power) for the task size of 1Mbps. Figure 4(b) demonstrates that a task size of 1.5Mbps led to a 72.82%, 75.62%, and 79.69% reduction in energy consumption when using CBMDFBA as compared to RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and RA(Max-Power).

The average energy consumption is calculated at 899.1 J in the proposed scheme CBMDFBA. In Fig. 4(c), task size 2Mbps is considered, and it found that the energy consumption is reduced by 76.31%, 80.21%, and 83.51%, respectively, to the scheme RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and RA(Max-Power). The average energy consumption is 917.4 J only in the proposed scheme CBMDFBA. Figure 4(d) shows that, when the proposed scheme is compared to schemes RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist), and RA(Max-Power) with taking task size 2.5Mbps, it resulted in 83.26%, 86.01%, and 88.34% reduction in energy consumption. According to the proposed CBMDFBA scheme, the average energy consumption is 841 J. From Fig. 4, it is clear that energy consumption is increasing with the increasing number of users.

In next scenario, we have considered the 52 MDs and 20 MHz are available in dense areas. We have increased the number of MHs to see the variation in simulation results. In Fig. 5, latency has been calculated with varying numbers of MHs. Figure 5(a) shows that the CBMDFBA scheme lowers latency by 99.86% when compared to the RA(QL-Munkres-TH), 99.88% when compared to the RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) scheme, and 99.71% when compared to the RA(Max-Power) strategy for a 1Mbps task size.

In the CBMDFBA scheme, the average latency is calculated at 2.27 ms. Figure 5(b) shows that, when comparing proposed scheme with scheme RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and RA(Max-Power), the latency is decreased by 99.84%, 99.87%, and 99.70%, respectively, with 1.5Mbps. In the proposed CBMDFBA system, the average latency is determined at 3.59ms. Task size of 2Mbps is examined in Fig. 5(c), and it is found that, in comparison to Schemes RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist), and RA(Max-Power), the latency in the proposed scheme is decreased by 99.87%, 99.89%, and 99.72%, respectively. In the proposed CBMDFBA system, the average latency is 4.89 ms. Figure 5(d) shows that, when comparing scheme RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist), and RA(Max-Power) with proposed CBMDFBA, the latency is decreased by 99.88%, 99.90%, and 99.78%, respectively with task size 2.5Mbps. The proposed CBMDFBA technique yielded an average delay of 5.10 ms. From Fig. 5, it is evident that the latency is decreasing with the increase in the number of helpers, and it also shows better results for larger task sizes.

Figure 6 presents the energy consumption calculation and a comparison of the simulation results. Figure 6(a) shows that the proposed CBMDFBA scheme’s average energy consumption is 955.9 J, 53.91% less than scheme RA(QL-Munkres-TH). Additionally, there was a 60.82% decrease from scheme RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and a 67.35% decrease from scheme RA(Max-Power). In Fig. 6(a), the task size is considered 1Mbps.

Compared to schemes RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist), and RA(Max-Power), Fig. 6(b) shows that a task size of 1.5Mbps resulted in a reduction of 68.93%, 74.05%, and 78.37% in energy usage for the proposed scheme. The proposed approach calculates the average energy usage at 943.7 J. When comparing the proposed scheme CBMDFBA to schemes RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and RA(Max-Power), Fig. 6(c) shows that a task size of 2Mbps resulted in a reduction in energy consumption of 78.29%, 81.87%, and 84.89% with schemes RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and RA(Max-Power) respectively.

The total average energy consumption in the proposed scheme is 908.3 Joules. Comparing the CBMDFBA to schemes RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and RA(Max-Power) with a task size of 2.5Mbps, Fig. 6(d) shows that the reduction in energy usage is reduced by 79.45%, 82.83%, and 85.69% respectively for schemes RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and RA(Max-Power) with proposed scheme. The average energy usage is 1036 J for the CBMDFBA scheme. In Fig. 6, it is clearly shown that the energy consumption is increasing with the increasing number of helpers due to the increment of the interference between the devices.

Figure 7 presents simulation results for latency vs. RES computation (cycle/sec). Figure 7(a) shows that the proposed CBMDFBA scheme’s average latency is 2.09ms, 99.88% less than scheme RA(QL-Munkres-TH). Additionally, there is a 99.90% reduction from scheme RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and a 99.76% reduction from scheme RA(Max-Power). In Fig. 7(a), the task size is considered to be 1Mbps. Figure 7(b) shows that, when comparing the proposed scheme with scheme RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist), and RA(Max-Power), the latency is decreased by 99.88%, 99.90%, and 99.75%, respectively with considering task size 1.5 Mbps. In the proposed CBMDFBA scheme, the average latency is determined to be 3.05ms. The task size of 2Mbps is examined in Fig. 7(c), and it is found that, in comparison to Schemes RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist), and RA(Max-Power), the latency in the proposed scheme is decreased by 99.86%, 99.88%, and 99.71%, respectively. The average latency in the proposed CBMDFBA system is calculated at 4.61 ms. Figure 7(d) shows that, when comparing scheme RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and RA(Max-Power) with CBMDFBA, the latency is decreased by 99.86%, 99.88%, and 99.72%, respectively, when the task size selected 2.5 Mbps. The proposed CBMDFBA technique yielded an average delay of 5.93ms. Figure 7 shows that the proposed scheme performs well even if the task size increases. Latency is decreasing; even RES computation is expanding.

Figure 8 presents the energy consumption calculation and a comparison of the simulation results for RES computation. Figure 8(a) shows that the proposed CBMDFBA scheme’s average energy consumption is 1114 J, 46.52% less than scheme RA(QL-Munkres-TH). Additionally, there is a 55.31% reduction from scheme RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and a 62.76% reduction from scheme RA(Max-Power). In Fig. 8(a), the size of the task is considered 1Mbps. Compared to schemes RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist), and RA(Max-Power), Fig. 8(b) shows that a task size of 1.5Mbps resulted in a reduction of 66.36%, 71.89%, and 76.58% in energy usage for the proposed scheme.

The proposed approach determines the average energy usage as 989.4 J. When comparing the proposed scheme CBMDFBA to schemes RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and RA(Max-Power), Fig. 8(c) shows that a task size of 2Mbps resulted in a reduction in energy consumption of 76.65%, 80.49%, and 83.74%. The total average energy consumption in the proposed scheme is 937.7 Joules. Comparing the CBMDFBA to schemes RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist), and RA(Max-Power) with a task size of 2.5Mbps, Fig. 8(d) shows that the reduction in energy usage is 81.63%, 84.66%, and 87.21%. The average energy usage is 933.4 J per the planned CBMDFBA system. In Fig. 8, it is clearly shown that the energy consumption increases with the increase in the RES computation due to the increase in the interference between the devices.

Figure 9 presents simulation results for latency vs. ES computation (cycle/sec). Figure 9(a) shows that the proposed CBMDFBA scheme’s average latency is 2.47 ms, 99.86% less than scheme RA(QL-Munkres-TH). There are 99.88% and 99.71% reductions, respectively, to scheme RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and RA(Max-Power). In Fig. 9(a), the size of the task is considered to be 1Mbps. Figure 9(b) shows that, when comparing the proposed scheme with scheme RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist), and RA(Max-Power), the latency is decreased by 99.87%, 99.89%, and 99.72%, respectively with task size 1.5 Mbps. In the proposed CBMDFBA scheme, the average latency is calculated at 3.53ms. The task size of 2Mbps is examined in Fig. 9(c), and it is found that, in comparison to Schemes RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist), and RA(Max-Power), latency in the proposed scheme is decreased by 99.86%, 99.89%, and 99.72%, respectively. In the proposed CBMDFBA scheme, the average latency is determined at 4.73 ms. Figure 9(d) shows that, when comparing scheme RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and RA(Max-Power) with CBMDFBA, the latency is decreased by 99.88%, 99.90%, and 99.75%, respectively with task size 2.5 Mbps. The proposed CBMDFBA technique yielded an average delay of 4.94ms. Figure 9 shows that the proposed scheme performs well even if task size increases. Latency also decreases even with ES computations increasing.

Figure 10 presents the energy consumption calculation and a comparison of the simulation results for ES computation. Figure 10(a) shows that the proposed CBMDFBA scheme’s average energy consumption is 974.4 J, which is 53.33% less than scheme RA(QL-Munkres-TH), 61.01% less than scheme RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and a 67.51% less from scheme RA(Max-Power) for 1Mbps task size. Compared to schemes RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist), and RA(Max-Power), Fig. 10(b) shows that a task size of 1.5Mbps resulted in a reduction of 68.54%, 73.71%, and 78.09% in energy usage for the proposed scheme. The proposed approach determines the average energy usage as 964.8 J. When comparing the proposed scheme CBMDFBA to schemes RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist) and RA(Max-Power), Fig. 10(c) shows that a task size of 2Mbps resulted in a reduction in energy consumption of 75.96%, 79.92%, and 83.26%. The total average energy consumption in the proposed scheme is 982.4 Joules. Comparing the CBMDFBA to schemes RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist), and RA(Max-Power) with a task size of 2.5Mbps, Fig. 10(d) shows that the reduction in energy usage is 78.44%, 81.99%, and 84.99%. The average energy usage is 1037 J, as per the CBMDFBA. In Fig. 10, it is clearly shown that the energy consumption increases with enlarge in the RES computation due to surge in the interference between the devices.

Fairness index is calculated with the help of:

A high fairness index means resources are distributed efficiently in the system. A comparison between all the baseline algorithms and the proposed algorithm is shown in Fig. 11. The figure shows that the proposed algorithm has the highest fairness index.

Figure 12 represents a plot between energy efficiency and edge server computation for the all baseline algorithms and proposed algorithm for varying MUs, MHs, \({f_{RES}}\)and\({f_{ES}}\). The figure shows that the energy efficiency is highest for the proposed algorithm compared to baseline algorithms.

Convergence of the proposed algorithm CBMDFBA is shown in Fig. 13. Average Q-values settle after a certain number of repetitions.

Conclusion

This work addresses task computation based on constraints like SNR and distance to fulfill the demands of real-time applications. The communication and computation in an ultra-dense area have been analyzed. RES, ES, and D2D are used for communicating and computation to reduce energy usage. To reduce the energy consumption problem in the proposed system, the model is formulated as CBMDFBA. The problem is handled by splitting into two more minor problems: problem\({P_{r2}}\), which involves optimizing transmission power using reinforcement learning, and problem \({P_{r3}}\) involves path optimizing to minimize overall energy consumption using CBMDFBA. The findings proved the proposed CBMDFBA algorithm performed better than the benchmark schemes. The proposed approach performs better than RA(QL-Munkres-TH), RA(QL-Munkres-Dist), and RA(Max-Power) in terms of reducing energy consumption and latency. The fairness index in the proposed algorithm is the highest, showing the resources are optimized and distributed efficiently. It also satisfies the need for real-time applications. The proposed work covers SNR, distance, and static latency-constrained applications for computations. Subsequent research will introduce a model applicable to mobile vehicles like trains and ships while considering the interferences.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Theodoridis, T. & Kraemer, J. Mobile Application Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Store Type, By Application (Gaming, Music & Entertainment, Health & Fitness, Social Networking, Retail & E-Commerce, Travel & Hospitality, Learning & Education), And Region, And Segment For. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/mobile-application-market

Li, Q., Zhao, J., Gong, Y. & Zhang, Q. Energy-efficient computation offloading and resource allocation in fog computing for internet of everything. China Commun. 16, 32–41 (2019).

You, C., Huang, K., Chae, H. & Kim, B. H. Energy-Efficient resource allocation for Mobile-Edge computation offloading. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 16, 1397–1411 (2017).

Xie, J., Jia, Y., Wen, W., Chen, Z. & Liang, L. Dynamic D2D multihop offloading in Multi-Access edge computing from the perspective of learning theory in games. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 20, 305–318 (2023).

Chen, J. et al. IRAF: A deep reinforcement learning approach for collaborative mobile edge computing IoT networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 6, 7011–7024 (2019).

Saeik, F. et al. Task offloading in edge and cloud computing: A survey on mathematical, artificial intelligence and control theory solutions. Comput. Networks. 195, 108177 (2021).

Siriwardhana, Y., Porambage, P., Liyanage, M. & Ylianttila, M. A. Survey on mobile augmented reality with 5G mobile edge computing: architectures, applications, and technical aspects. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials. 23, 1160–1192 (2021).

Luo, Q., Hu, S., Li, C., Li, G. & Shi, W. Resource scheduling in edge computing: A survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials. 23, 2131–2165 (2021).

Attar, H. et al. B5G applications and emerging services in smart IoT. Environ. Int. J. Crowd Sci. J. 9, 79–95 (2025).

Kong, X., Wu, Y., Wang, H. & Xia, F. Edge computing for internet of everything: A survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 9, 23472–23485 (2022).

Li, K. et al. Task computation offloading for Multi-Access edge computing via attention communication deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 16, 2985–2999 (2023).

Waqas, M. et al. A comprehensive survey on Mobility-Aware D2D communications: principles, practice and challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials. 22, 1863–1886 (2020).

Mach, P. & Becvar, Z. Device-to-Device relaying: optimization, performance perspectives, and open challenges towards 6G networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials. 24, 1336–1393 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Adaptive task offloading for mobile edge computing with forecast information. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 74, 4132–4147 (2025).

Wei, Z., He, R., Liu, H. & Song, C. Joint computation offloading and resource allocation in green MEC-Assisted Software-Defined Island internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 12, 140–162 (2025).

Zhu, X. et al. DRL-Based joint optimization of wireless charging and computation offloading for Multi-Access edge computing. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 18, 1352–1367 (2025).

Teng, Z., Fang, J. & Liu, Y. Combining Lyapunov optimization and deep reinforcement learning for D2D assisted heterogeneous collaborative edge caching. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 21, 3236–3248 (2024).

Jiang, C., Luo, Z., Gao, L. & Li, J. A. Truthful incentive mechanism for Movement-Aware task offloading in crowdsourced mobile edge computing systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 11, 18292–18305 (2024).

Niu, Z., Liu, H., Ge, Y. & Du, J. Distributed hybrid task offloading in Mobile-Edge computing: A potential game scheme. IEEE Internet Things J. 11, 18698–18710 (2024).

Feng, D. et al. Device-to-device communications underlaying cellular networks. IEEE Trans. Commun. 61, 3541–3551 (2013).

Doppler, K., Yu, C. H., Ribeiro, C. B. & Jänis, P. Mode selection for device-to-device communication underlaying an LTE-advanced network. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Netw. Conf. WCNC. https://doi.org/10.1109/WCNC.2010.5506248 (2010).

Liu, J., Kato, N., Ma, J. & Kadowaki, N. Device-to-Device communication in LTE-Advanced networks: A survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials. 17, 1923–1940 (2015).

Mach, P., Becvar, Z. & Vanek, T. In-Band Device-to-Device communication in OFDMA cellular networks: A survey and challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials. 17, 1885–1922 (2015).

Nomikos, N. et al. A survey on Buffer-Aided relay selection. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials. 18, 1073–1097 (2016).

Asadi, A., Wang, Q. & Mancuso, V. A survey on device-to-device communication in cellular networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials. 16, 1801–1819 (2014).

Jameel, F., Hamid, Z., Jabeen, F., Zeadally, S. & Javed, M. A. A survey of device-to-device communications: research issues and challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials. 20, 2133–2168 (2018).

Hu, Z., Niu, J., Ren, T., Liu, X. & Guizani, M. SITOff: enabling Size-Insensitive task offloading in D2D-Assisted mobile edge computing. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 24, 1567–1584 (2025).

Jiang, W. et al. Joint computation offloading and resource allocation for D2D-Assisted mobile edge computing. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 16, 1949–1963 (2023).

Fang, T., Yuan, F., Ao, L., Chen, J. & Joint Task Offloading D2D pairing, and resource allocation in Device-Enhanced MEC: A potential game approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 9, 3226–3237 (2022).

Xiao, Z. et al. Multi-Objective parallel task offloading and content caching in D2D-Aided MEC networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 22, 6599–6615 (2023).

Su, J., Liu, Z., Li, Y., Lee, J. & Guan, X. Communication and computing balanced resource allocation in D2D-Based vehicular MEC networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 11, 40689–40701 (2024).

Huang, X., Ji, G., Zhang, B. & Li, C. Platform profit maximization in D2D collaboration based Multi-Access edge computing. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 22, 4282–4295 (2023).

Garg, A., Arya, R. & Singh, M. P. Price elasticity log-log model for cost optimization in D2D underlay mobile edge computing system. Journal of Supercomputing vol. 79Springer US, (2023).

Chen, C. L., Brinton, C. G. & Aggarwal, V. Latency minimization for mobile edge computing networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 22, 2233–2247 (2023).

Zhang, T. & Chen, W. Computation offloading in heterogeneous mobile edge computing with energy harvesting. IEEE Trans. Green. Commun. Netw. 5, 552–565 (2021).

Patel, R. & Arya, R. Trust-based resource allocation and task splitting in ultra-dense mobile edge computing network. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 18, 1–17 (2025).

Al-Abiad, M. S., Obeed, M., Hossain, M. J. & Chaaban, A. Decentralized aggregation for Energy-Efficient federated learning via D2D communications. IEEE Trans. Commun. 71, 3333–3351 (2023).

Liu, S. et al. Communication and energy efficient decentralized learning over D2D networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 22, 9549–9563 (2023).

Yin, R., Lu, X., Chen, C., Chen, X. & Wu, C. Energy-Efficient mutual learning over D2D communications. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 72, 16711–16724 (2023).

Wei, Z., He, R., Liu, H. & Song, C. Joint computation offloading and resource allocation in green MEC-Assisted Software-Defined Island internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 12, 140–162 (2024).

Fan, W. Hybrid deep reinforcement Learning-Based task offloading for D2D-Assisted Cloud-Edge-Device collaborative networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 23, 13455–13471 (2024).

Mahadevan, R., Edwards, J. S. & Doyle, F. J. Dynamic flux balance analysis of Diauxic growth in Escherichia coli. Biophys. J. 83, 1331–1340 (2002).

Watkins, C. J. C. H. & Dayan, P. Q-learning. Mach. Learn. 8, 279–292 (1992).

Acknowledgements

There is no acknowledgement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors ContributionR.P.- Rachit PatelR.A.- Rajeev AryaR.P.: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Software and Methodology R.A.: Validation, Project administration, Supervision, Investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, R., Arya, R. Multi-dimensional flux balance analysis to optimized resources and energy efficiency in MEC aided 5G networks. Sci Rep 15, 30987 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16847-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16847-z