Abstract

A hybrid methodology for bearing fault and severity analysis using param, eter-optimized variational mode decomposition (VMD) and deep learning (DL) algorithms is presented in this study. Different localized defects are artificially seeded at the contacting surfaces of a self-aligning bearings, and vibration data is generated (Case study II) under various radial-load and speed conditions for DL algorithm development. This data is pre-processed using the parameter-optimized VMD, where the intrinsic mode function with the highest kurtosis is processed using a deep learning (DL) algorithm. Particle swarm optimization is used for optimizing two VMD parameters. Further, seven different DL algorithms are implemented to classify various fault severity of rolling-element bearings. These algorithms are validated against the standard repository dataset of Case Western Reserve University (Case study I). The reliability of these algorithms is also tested using the generated dataset (Case study II) and the results show that 1D-CNN, WaveNet and gated recurrent unit have outperformed all other algorithms by achieving accuracies of 99.65%, 97.05% and 97.33%, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bearings are the essential elements of any rotating machinery and they develop many types of imperfections during their use. Each such imperfection exhibits vibrations of distinct characteristic frequency. Various studies have been presented to diagnose the bearing faults, these studies include mathematical models and soft computing techniques1,2,3,4. Later in5,6,7, support vector machine (SVM) and artificial neural network (ANN) were used to diagnose the bearing faults and concluded that these algorithms are highly effective for bearing diagnostics using vibration signals. The effect of shaft misalignment on the spindle vibration response using numerical simulations was investigated by Wang et al.8. It was found that the assembly errors increased with the increase in misalignment, causing the system to become unstable. Zhang et al.9 analysed the effect of local and extended defects on the time varying stiffness of the bearing. The results show that the load distribution is not necessarily continuous, and the maximum and minimum stiffness of the angular contact ball bearing can be located at either of the two boundary positions or even at non-boundary position under the effect of the contact angle. Further, a method was formulated to detect a slant crack in a rotor bearing system. The fundamental mode shapes of the rotor bearing systems were wavelet transformed to identify the crack location. It can be seen in10, that deep transfer learning (DTL) was used for identifying faults in rolling bearings under varying conditions. It integrates different types of networks, i.e., deformable convolutional neural networks (DCNN) and deep long short-term memory (DLSTM), to improve the local feature detection abilities of standard convolution neural networks (CNN). It encodes information, and the dense layers collect high-level features to extract the data points into different fault categories. The results of the testing demonstrate that this methodology is more useful and accurate than conventional methods. In11, multi-adversarial domain adaptation is used to build a fault diagnosis model for motor bearing. The model’s focus on relevant information was enhanced by incorporating global context network and selective kernel network to the employed improved residual network. It aligns conditional and marginal distributions by using multiple adversarial domain discriminators and multi-kernel maximum mean discrepancy. It provided better diagnostic results under various conditions and devices. Further, faults in the bearing were detected using a hybrid CNN12. In13, supervised joint matching and deep transfer CNNs were used to create a fault diagnosis framework for cross-domain. Two datasets were used to verify the performance, and the results validated the robust ability of fault diagnosis. A multi-image feature extraction and attention fusion method was developed using gramian angular difference field and gramian angular summation field for fault diagnosis14. The fusion weights of these fields are adjusted by developing attention fusion modules. The trust of users was improved by visualizing the attention weights and features of the model. Further, a solution for small sample data in fault diagnosis using a combination of CNN and support vector machine15 was applied in roller bearing fault diagnosis and improved results were compared to traditional methods. Also, in16, a technique combining multiscale transform features (MTF) and CNN was analysed to detect faults in rolling bearings. The MTF transformed time series data to images without significant losses, and then the CNN model was applied. Further, CNN was utilized with an attentive dense CNN (ADCNN) to address the challenge of training a DL model with limited data17. This model merged dense convolutional blocks with an attention mechanism, resulting in a streamlined model with fewer unknown learning parameters. Despite its simplicity, this method produced effective results. In18, 1D2D-EDL ensemble DL network based on the integration of 1D and 2D mechanisms was introduced. Later, 2D images were obtained by converting 1D time series and using relative angle matrix. Multi-head self-attention and long short-term memory (LSTM) were integrated into 2D network. 2D images were obtained after converting 1D data by selecting 2D conversion method. The superiority of the 1D2D-EDL was demonstrated by comparing it with other DL methods. A physics-based CNN model performed fault classification tasks in19, which improved the efficiency and accuracy of traditional CNN by guiding the design with physical characteristics of bearing acceleration signals. The gramain time frequency enhancement net (GTFE-net), a CNN model that utilized graph network representation (GNR) for fault classification, was introduced in20,21. The model effectively reduced unnecessary noise in vibrational signals and outperformed other methods. Likewise, a fault diagnosis method for rolling bearings used a CNN and power spectrum density of auto-regressive in21. It changed the original vibration signal into a power spectrum, and further, classified using CNN. It was compared with few fault diagnosis methods for testing the performance. High diagnostic accuracy was achieved by the model with minimum training samples under varied speeds and loads. In22, bidirectional LSTM (Bi-LSTM) and an optimized sparse deep autoencoder (DAE) were integrated to detect and classify faults in bearing. Robust feature reduction was achieved by combining BO-optimized deep autoencoder and PCA. The results indicated the efficiency of the presented method to classify faults in bearings. A DL model was used to learn physical laws of bearing failure23. A 15-degree-of-freedom kinetic physical model was introduced to ensure the real physical information. Particle filtering meets the sound-vibrational physical-information boundaries by self-calibration. Physical-information fusion constraint-guided enabled fault diagnosis by dual learning of data and physical features. Further, sensitivity analysis and feature visualization were used to analyse model explainability.

Further, a hierarchical learning rate adaptive DCNN was proposed to identify bearing issues and assess their severity24. The model employed an improved method for automatic feature extraction, which was useful for diagnosing problems in rotating machinery, and achieved high accuracy. Iqbal and Madan25 proposed a methodology to diagnose the bearing faults using CNN where the vibration and acoustic signals were transformed into time-frequency maps using STFT. The proposed methodology classified the data with 100% accuracy and outperformed all other methods. Mishra et al.26 used both the CNN and SVM for feature extraction and classification, respectively, to diagnose the bearing faults. The proposed method consumed less computation time as compared to conventional methods.

In27, authors have systematically reviewed theories based on machine learning for fault diagnosis. Further, deep learning (DL) theories in fault diagnosis have been reviewed. Fine non-stationarities in signals were enhanced by developing a denoising filter in28. The mountain gazelle optimization (MGO) algorithm was used to optimize the filter coefficients estimated by calculating system impulse. The periodic impulses were characterized by developing a novel sparsity index NEKI. Further, industrial case studies were used to validate the efficacy of denoising filters. Later, these researchers have addressed the same issue in29 by acquiring the vectors of optimized spectral kurtosis using flow direction algorithm. The filter increased kurtosis by 2977.84% and 2575.92% for vibration signals and acoustic signals, respectively.

Based on the literature, it has been observed that there is a scope of improvement in the existing methods for detecting fault severity in bearings through experimental investigation and thus, the following contributions have been made in this study.

-

The variational mode decomposition (VMD) method is improvised by updating its parameters using particle swarm optimization (PSO). The improvised model performed better than the existing VMD for diagnosing bearing-faults.

-

The parameter-optimized VMD uses the PSO with maximization of spectral kurtosis as its fitness function for decomposing the raw signals into intrinsic mode functions (IMF). The IMF with the highest kurtosis value is selected from the parameter-optimized VMD and contains accurate fault information, thus characterizing the bearing signals for faults and their severity.

-

The selected IMF are fed into the seven different DL algorithms, i.e., 1D-CNN, WaveNet, gated recurrent unit (GRU), LSTM, temporal convolutional network (TCN), CNN and ANN. The results obtained from training and testing are presented in the result and discussion section.

-

Out of all the developed DL methods, the 1D-CNN has achieved the highest accuracy compared to the existing state-of-the-art techniques.

This paper consists of 5 sections as follow: introduction, methodology, experimentation – sample preparation and data acquisition, results and discussions, and conclusions.

Parameter optimized VMD

VMD is a self-adaptive method used for signal decomposition, which helps to decompose a time-series signal using Winger filtering, heterodyne demodulation, one-dimensional and Hilbert transform30. The decomposed signals from VMD are called IMF’s. The spectra of each IMF are obtained using Hilbert’s transform, which is then converted to fundamental frequency for evaluating the bandwidth of each mode and construct the constraint model against a variational problem. The constrained variational problem (\(\:{L}^{2}\) norm) is explained as shown in Eq. 131.

Where.

-

f = Signal in original form.

-

\(\:\delta\:\) = Distribution for Dirac.

-

k = Modes.

-

\(\:{u}_{k}\) = Signal corresponding to \(\:{k}^{th}\) mode.

-

\(\:{w}_{k}\) = Particular mode’s central frequency.

As per the Lagrange multipliers for solving the optimization problem, the augmented Lagrangian is given as shown in Eq. 2

Here \(\:\alpha\:\) defines penalty term. For a given input, the VMD method is significantly influenced by the parameters \(\:\alpha\:\) and k. Many methods have been used in previous studies in order to optimally find out the values of \(\:\alpha\:\) and k. This paper uses PSO with an objective/fitness function to maximize spectral kurtosis (SK). Thus, the bandwidth with the maximum kurtosis value is selected. Following the VMD-based signal decomposition, the envelope of the selected IMF is constructed and processed further. Therefore, the problem of optimization for optimized PSO can be written as shown in Eq. 332.

Deep learning models

The description of the models used in this study are as follows:

1D-CNN

At its core, a 1D-CNN consists of a series of layers, each with its own specific function. Figure 1 depicts the implemented 1D-CNN architecture. The first layer in the model is the convolutional layer, which performs the main feature extraction. This layer applies a set of filters or kernels to the input data, with each kernel extracting a specific feature. During the convolution operation, each kernel is applied to a segment of the input data, and the dot product of the kernel and the input data is calculated to produce a new feature. The output of this layer is a set of feature maps, which represent the presence of the extracted features from the input data.

The mathematical equation for the convolution operation is shown in Eq. 433:

where yi is the output at position i, wk is the weight or kernel value, xi−k is the input data, and b is used as the bias term. \(\:\sum\:k\) is a mathematical symbol that represents summation or adding up a series of terms. In the context of the equation yi = ∑ [ k wk xi−k ] + b, the term \(\:\sum\:k\) means that the kernel values (wk) are multiplied with the input data xi−k at different positions k and then added up to produce the output value yi33. The size of the output feature map depends on the size of the kernel and the stride, which determines the distance between each application of the kernel.

Next, the pooling layer is added to down sample the previous layer’s output. This reduces the feature maps’ spatial dimensionality and helps prevent overfitting. Feature maps are reduced by two common types of pooling techniques, i.e., max pooling and average pooling, thus reducing computations. The max pooling selects the maximum value from each local region of the feature map, while average pooling takes the average of the values. The output of the pooling layer is a smaller feature map with fewer dimensions. In this study, max pooling is used. The mathematical equation for max pooling is shown in Eq. 533:

where =yi is the output value, x[i∶i+k] is the input segment of length k, and max() returns the maximum value of the segment.

Finally, the output of the pooling layer is passed through a fully connected layer, which maps the features to a desired output. This layer performs a linear transformation of the features, followed by an activation function, such as ReLU or SoftMax. The output of the SoftMax function is a probability distribution over the classes, indicating the likelihood of each class given the input data34.

WaveNet

A deep generative model developed for producing raw audio waveforms, and it has also been adapted for various sequence modeling tasks. It employs stacks of causal and dilated convolutions to model complex temporal dependencies in data, allowing it to generate highly realistic audio signals by predicting one audio sample at a time35. The use of dilated convolutions enables WaveNet to achieve a large receptive field efficiently, making it particularly effective for tasks like speech synthesis and time-series forecasting, therefore making it suitable for this study. In the implementation phase for this work, it is observed that the use of Conv1D layers in a residual network of 5 layers made the model more efficient. The implemented WaveNet model for this work is depicted in Fig. 2.

GRU

It is a type of recurrent neural network (RNN) designed to efficiently handle sequential data, making it particularly useful for time-series analysis. Unlike traditional RNNs, GRU incorporates gating mechanisms, namely, update and reset gates that help regulate information flow. This allows the network to retain important patterns over long sequences while mitigating issues like vanishing gradients36. Because of its ability to learn complex temporal dependencies, GRU is widely used in applications such as stock market prediction, weather forecasting, and sensor-based anomaly detection, where historical trends play a crucial role in determining future outcomes. The implemented GRU is depicted Fig. 3.

LSTM

It is implemented based on RNN, designed to model sequential data by capturing long-range dependencies. Unlike traditional RNNs, LSTMs use gated mechanisms namely the input, forget, and output gates to regulate the flow of information and mitigate issues like vanishing and exploding gradients37. This architecture allows LSTMs to effectively learn patterns in time-series data, making them widely used in applications such as speech recognition, language modeling, and financial forecasting. The implemented LSTM model for this study is depicted in Fig. 4.

TCN

It is a type of DL architecture specifically designed for sequence modeling tasks, offering an alternative to recurrent models like LSTMs. TCNs utilize 1D fully convolutional layers with causal convolutions to ensure that the output at any time step depends only on current and past inputs, preserving temporal order. Additionally, TCNs incorporate dilated convolutions, which expand the receptive field without increasing model complexity, enabling the network to capture long-range dependencies efficiently38. This architecture has demonstrated superior performance in various time-series forecasting and sequence classification tasks. The implemented TCN model in this study benefited from using Conv1D layers in first two layers and followed by the TCN layers. The implemented model architecture is depicted in Fig. 5.

CNN

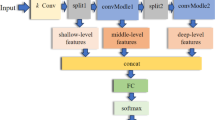

It is a specialized class of DL models designed for efficient processing of grid-like data, such as images. They leverage convolutional layers to automatically detect patterns, edges, and textures, significantly reducing the need for manual feature engineering. CNNs utilize pooling layers to minimize computational complexity while preserving essential features. Their hierarchical architecture enables them to learn increasingly complex representations, making them highly effective for tasks like image classification, object detection, and facial recognition39. Recent advancements incorporate attention mechanisms and transformer-based enhancements to further improve CNN performance in various domains40. The implemented architecture of CNN is shown in Fig. 6.

ANN

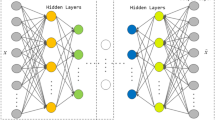

These are computational models inspired by the structure and functionality of the human brain. They consist of interconnected layers of artificial neurons that process information through weighted connections. ANNs learn patterns by adjusting these weights based on training data, enabling them to perform complex tasks like classification, regression, and pattern recognition. They are widely used in domains such as natural language processing, finance, and medical diagnosis due to their ability to model non-linear relationships and uncover hidden patterns in large datasets39. Recent advancements, including DL architectures, have significantly enhanced their predictive capabilities and scalability40. The implemented ANN model is depicted in Fig. 7.

Methodology

The overall methodology utilized in this study can be depicted in Fig. 8, which consists of 3 main parts, i.e., data acquisition, data preprocessing, and implementation with assessment of DL algorithms.

Data acquisition and preprocessing

The defective bearings were modeled in a lab environment and tested under different speed and radial load conditions, and the vibration signals were captured using accelerometers, which were further converted to digital form using the data acquisition system (DAQ). The data was pre-processed using parameter-optimized VMD and then used for DL models implementation. The steps involved in the preprocessing incl ude filtration of raw signal data using parameter-optimized VMD, choosing the IMF with the highest kurtosis, removing null values, labelling the data, preparing categorical data, and splitting the dataset into training and testing sets.

DL model implementation

A total of 7 DL models were implemented for the assessment of ball bearing fault severity, which are 1D-CNN, WaveNet, GRU, LSTM, TCN, CNN and ANN. These models are trained on vibration data obtained from a set of experiments. The data was pre-processed using a sliding window approach with a window length of 1000 and a stride of 50. To implement the DL models, necessary libraries such as scipy.io, seaborn, numpy, pandas, os, matplotlib.pyplot, and to_categorical function from tensorflow.keras.utils were imported. The data was loaded into a pandas dataframe using pd.read_csv, and rows with missing values were dropped using dropna(). The ‘data’ column was converted to a numeric datatype, and the ‘fault’ column to a string datatype. Data was then prepared for training the DL models. Unique values in the ‘fault’ column were looped through, and windows of length winlen were extracted from the corresponding fault data with a stride of stride. The extracted windows were stored in a numpy array X, and the corresponding fault types were stored in a numpy array Y. The Label Encoder() function is used to encode the fault types. The encoded fault types were then converted into one-hot encoded format using the categorical function from tensorflow.keras.utils. The developed models’ hyper-tuned parameters and properties are depicted in the Table 1.

Performance evaluation

This study uses two different datasets; however, as both are balanced in categorical or class numbers, the performance of the DL models were evaluated using accuracy metrics (refer Eq. 6). This metric is an ideal evaluation procedure for artificial intelligence classification-related problems for balanced dataset34. The following performance metric (refer Eq. 6) was used to evaluate the efficiency of the implemented models:

Here, TP = true positive, TN = true negative.

Hyperparameter tuning

It is the process of selecting the best set of parameters that affect the performance of any DL model. It involves testing different combinations of hyperparameters, such as batch size and number of layers, to find the optimal set that results in accurate and effective models. Hyperparameter tuning is a critical step in building accurate and effective DL models. Careful consideration and experimentation are required to find the optimal set of hyperparameters for a given problem and dataset. The best possible results are obtained by iterative hyperparameter tuning of the models as shown in Table 1.

Cross-verification of models

Cross-verification is done to verify the performance and generalization ability of the models with two datasets for demonstrate robustness and real-world applicability.

Experimentation – sample preparation and data acquisition

Different defective self-aligning bearings were tested on a test-rig where the vibration signatures were captured for varying speed and load conditions (Fig. 9). The test-rig consists of a 3-phase electric motor which is connected to the bearing shaft through a flexible coupling. A variable frequency drive was used to control the rotational speed of the shaft. A hydraulic loading system is used to apply radial load on the test bearing. Two uniaxial accelerometers were used to acquire the vibration data from the test-bearing, and were placed in horizontal and vertical directions on the bearing pedestal at an angular separation of 900 to each other. Details of the experimental setup and DAQ are shown in Table 2.

Rectangular spalls (defects) were artificially seeded on the inner and outer races of the self-aligning bearings using electric discharge machining (EDM). Five different sizes of spalls were made for outer-race and inner-race (see Fig. 10). The self-aligning bearings were also tested for healthy conditions apart from the defective conditions. Here, OR stands for outer-race, and IR stands for inner-race defects. Table 3 represents details of various defect sizes.

Each defective bearing was tested for six different speeds and radial-load conditions, namely S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, and L1, L2, L3, L4, L5, L6. Thus, 36 sample files were collected for each bearing. A total of 10 defective bearings and one healthy bearing were tested for the same combination of speed and radial load as explained above. Thus, a total number of 396 raw vibration signals \(\:\left(36\times\:11=396\right)\) were acquired during the study. Each of these signals was acquired for 10 s and sampled at a sampling rate of 51 kHz. As an example, the nomenclature of all the 36 signals collected from one of the defective bearings (OR1) is mentioned in Table 4. Likewise, the same analysis can be shown for all the defects ranging from OR1 to OR5, IR1 to IR5, and one H i.e., healthy.

Results and discussions

Pre-processing

As discussed in the methodology, the raw data were initially pre-processed using parameter-optimized VMD, where the IMF with the highest spectral kurtosis value was selected and fed into the DL models. Kurtosis indicates impulsiveness of a time-series data; therefore, the IMF with its highest kurtosis value has been selected. Figure 11 compares one such raw vibration signal and its corresponding optimized IMF (with the highest kurtosis) for the OR defect in both time and frequency domains (using envelope spectrum). The characteristic-frequency peaks are clearly visible in the spectra; thus, the required information content of the signal has significantly increased.

Similarly, Fig. 12 compares raw vs. optimized IMF and their respective envelope spectra belonging to inner-race defects.

Figures 13 and 14 show the VMD optimization results along with its first three IMFs for outer and inner race defect signals. The kurtosis value of each IMF has been mentioned on the right-hand side of the y-axis. The IMF with the highest kurtosis value is further selected to be processed into the DL algorithm as it contains maximum information about the defects. The optimized values of parameters \(\:\alpha\:\) and k (using PSO) for one of the defect types (OR1) at different speed and radial load conditions have been provided in Table 5. Similarly, \(\:\alpha\:\) and k were calculated for all other defects also. With these optimized parameters, the VMD was found to perform better than the conventional VMD in terms of increasing the kurtosis value.

Validation of the model (Case-study I)

The proposed methodology was validated using the available online dataset at the Western Reserve University (CWRU) repository (available at https://engineering.case.edu/bearingdatacenter). Figure 15 represents the experimental setup of CWRU (Dataset I). A deep-groove ball bearing (SKF 6205) was used for this dataset, and spalls of various sizes were artificially seeded into the bearing races. It was then tested for various rotational speeds and radial-load conditions. The dataset was acquired at rotational speeds of 1797 rpm, 1772 rpm, 1750 rpm, and 1730 rpm and sampled at 48 kHz. The details of the defects and experimental conditions have been given in Table 6.

The confusion matrices of the applied model’s performance on the CWRU dataset are shown in Fig. 16. From the confusion matrix, all of the applied models classify the healthy and defective bearings to their right labels with an accuracy of 100%. 1D-CNN and GRU successfully classified all the faults correctly, and thus, both achieved a perfect accuracy of 100% for all labels. CNN also performed well and classified most of the labels correctly, with an accuracy of 100%.

The only categories it mislabelled were 14_IR and 14_OR; even in those categories, an accuracy of 99.96% was achieved. Figure 11 shows the training loss and accuracy of the proposed models for case study I across 30 epochs. It can be seen from Fig. 17 that 1D-CNN and GRU reach an accuracy and loss of 100% and 0%, respectively, in fewer epochs as compared to CNN and ANN models. Figure 18 shows the performance of the applied models across accuracy and validation accuracy.

Case study II

This section uses a second dataset acquired from the test rig as input to the proposed 1D-CNN, WaveNet, GRU, LSTM, TCN, CNN, and ANN. These models were trained using the fit function. The training progress was monitored using accuracy and validation accuracy metrics for case study II across 30 epochs, as depicted in Fig. 19.

The performance of the models across different performance measures is summarized. It shows that the 1D CNN emerged as the best among all models by obtaining scores above 99.38% for all the evaluated metrics, GRU attained scores in the mid-90s range, and the ANN and CNN did not perform as well as they got scores in the early 80s.

Furthermore, it is seen that the convergence speed of the models is slower when compared to the performance on the CWRU dataset, which means that the models required more epochs to converge to a final score which is depicted in Fig. 20.

The confusion matrices for the top two performing models are given in Fig. 21. It can be observed that 1D-CNN proved to be the best among the applied classifiers. 1D-CNN correctly classified most faults to their correct labels with an accuracy of over 99% for most of the classes. OR5 category got the lowest accuracy for 1D-CNN, with 96.01% of the labels being marked correctly.

Accuracy and loss graphs for dataset II (a) 1D CNN accuracy graph, (b) 1D CNN loss graph, (c) ANN accuracy graph, (d) ANN loss graph, (e) CNN accuracy graph, (f) CNN loss graph, (g) GRU accuracy graph, (h) GRU loss graph, (i) WaveNet accuracy graph, (j) WaveNet loss graph, (k) LSTM accuracy graph, (l) LSTM loss graph, (m) TCN accuracy graph, and (n) TCN loss graph.

However, the ANN and CNN models failed to repeat the same performance they displayed for the CWRU dataset. ANN achieved an accuracy score of 81.16%, and it was especially poor for the categories IR2, IR3, IR4, IR5, OR1, and OR2. All of the mentioned categories had an accuracy lower than 83%, with IR5 being classified correctly only 54.49% of the time. CNN displayed similar results, with an accuracy of over 90% for only three of the eleven fault categories. Overall, CNN got an accuracy of 82.52%, making it slightly better than ANN but still worse than the proposed 1D-CNN model and GRU model. GRU again was the second-best classifier as it attained an accuracy of 96.05%. Similar to the proposed 1D CNN model, GRU got an accuracy of more than 99% for most of the classes, but for the class OR5, it attained an accuracy of 64.10%. Likewise, the results are in similar nature for LSTM, TCN and WaveNet.

Conclusions

The presented work focused on the detection and severity classification of faults in a self-aligning rolling-element bearing using DL techniques. DL methods such as 1D-CNN, WaveNet, GRU, LSTM, TCN, CNN and ANN are used for the classification. Different fault types of self-aligning ball bearings are modeled in the lab environment to simulate the dataset with various loads and speeds. Two different case studies were performed. Where Case study I was based on the CWRU’s standard dataset, case-study II was performed using dataset from test-rig. These signals are pre-processed using parameter-optimized VMD. PSO was used as the optimization technique. Based on the results obtained from DL methods using the CWRU dataset, it was found that all classifiers provided ideal performances (100% accuracy achieved by GRU and 1D-CNN), whereas for the test-rig dataset, the performance of models varied. ANN and CNN both achieved accuracies of 81.16% and 82.52%, respectively. However, 1D-CNN performed the best with 99.37% accuracy, and GRU attained an accuracy of 96.05%. Also, the experimental results indicate that while all applied models performed well on the standard CWRU dataset, their performance varied when applied to the lab generated Case study II dataset. Specifically, all the models did not perform well as they did on the CWRU dataset except 1D-CNN. Therefore, the proposed 1D-CNN model demonstrated good performance for both datasets, indicating its ability to handle single-dimensional datasets. This suggests that the 1D-CNN model may be more suitable for handling new datasets, while the other models may be more appropriate for standardized datasets such as the CWRU dataset. Thus, it can be concluded that 1D-CNN and GRU are more suitable for dealing with new datasets than ANN and CNN, which are more appropriate for standard datasets.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the first author on reasonable request.

References

Mishra, R. K., Choudhary, A., Fatima, S., Mohanty, A. R. & Panigrahi, B. K. Multi-fault diagnosis with wavelet assisted stacked image fusion and dual branch CNN. Applied Soft Computing, 113183, (2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2025.113183 (2025).

Nayana, B. R., Subha, R., Radhakrishnan, R. & Geethanjali, P. Scalable bearing fault diagnosis using metaheuristic feature selection and machine learning for diverse operating conditions. Syst. Sci. Control Eng., 13(1), 2469606, (2025). https://doi.org/10.1080/21642583.2025.2469606 (2025).

Patil, A. P., Mishra, B. K. & Harsha, S. P. A mechanics and signal processing based approach for estimating the size of spall in rolling element bearing. Eur. J. Mechanics-A/Solids. 85, 104125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euromechsol.2020.104125 (2021).

Parmar, V., Saran, V. H. & Harsha, S. P. Effect of an unbalanced rotor on dynamic characteristics of double-row self-aligning ball bearing. Eur. J. Mechanics-A/Solids. 82, 104006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euromechsol.2020.104006 (2020).

Ma, Z. & Zhang, Y. A study on rolling bearing fault diagnosis using RIME-VMD. Sci. Rep. 15, 4712. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89161-3 (2025).

Ji, Y., Gao, J., Shao, X. & Wang, C. Multi-scale quadratic convolutional neural network for bearing fault diagnosis based on multi-sensor data fusion. Nonlinear Dyn. 113, 14223–14244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-025-10918-6 (2025).

Nie, G. et al. A novel intelligent bearing fault diagnosis method based on image enhancement and improved convolutional neural network. Measurement, 242, 116148; (2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2024.116148

Wang, P. et al. Numerical and experimental analysis of vibration characteristics of spindle system under bearing assembly errors. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 52 (8), 4811–4838. https://doi.org/10.1080/15397734.2023.2237689 (2023).

Cheng, H., Zhang, Y., Lu, W. & Yang, Z. Effect of boundary position and defect shape on the mechanical properties of ball bearings. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 51 (3), 1645–1665. https://doi.org/10.1080/15397734.2021.1875329 (2021).

Wang, Z., Liu, Q., Chen, H. & Chu, X. A deformable CNN-DLSTM based transfer learning method for fault diagnosis of rolling bearing under multiple working conditions. Int. J. Prod. Res. 59 (16), 4811–4825. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2020.1808261 (2020).

Liu, X. M. et al. A motor bearing fault diagnosis model based on multi-adversarial domain adaptation. Sci. Rep. 14, 29078. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80743-1 (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. A hybrid deep-learning model for fault diagnosis of rolling bearings. Measurement 169, 108502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2020.108502 (2020).

Liu, C., Dong, F., Ge, K. & Tian, Y. A new bearing fault diagnosis method based on deep transfer network and supervised joint matching. IEEE Photonics J. 16(3), 1–17, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/JPHOT.2024.3392392 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. A novel interpretable fault diagnosis method using multi-image feature extraction and attention fusion. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 189, 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patrec.2025.01.006 (2025).

Yuan, L. et al. Rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on convolutional neural network and support vector machine. IEEE Access. 8, 137395–137406. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3012053.s (2020).

Wang, M., Wang, W., Zhang, X. & Iu, H. H. C. A new fault diagnosis of rolling bearing based on Markov transition field and CNN. Entropy, 24(6), 751; (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/e24060751 (2022).

Plakias, S. & Boutalis, Y. S. Fault detection and identification of rolling element bearings with attentive dense CNN. Neurocomputing, 405, 208–217 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2020.04.143(2020).

Wang, L. & Zhao, W. An ensemble deep learning network based on 2D convolutional neural network and 1D LSTM with self-attention for bearing fault diagnosis. Appl. Soft Comput. 172, 112889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2025.112889 (2025).

Ruan, D., Wang, J., Yan, J. & Gühmann, C. CNN parameter design based on fault signal analysis and its application in bearing fault diagnosis. Adv. Eng. Inf. 55, 101877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2023.101877 (2023).

Jia, L., Chow, T. W. & Yuan, Y. GTFE-Net: A Gramian time frequency enhancement CNN for bearing fault diagnosis. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 119, 105794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105794 (2023). (2023).

Zhang, K. et al. A multi-fault diagnosis method for rolling bearings. SIViP 18, 8413–8426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11760-024-03483-9 (2024).

Yousaf, M. Z., Guerrero, J. M. & Sadiq, M. T. Optimizing machine learning algorithms for fault classification in rolling bearings: A bayesian optimization approach. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 150, 110597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2025.110597 (2025).

Keshun, Y., Puzhou, W., Peng, H. & Yingkui, G. A sound-vibration physical-information fusion constraint-guided deep learning method for rolling bearing fault diagnosis. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 253, 110556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2024.110556 (2025).

Guo, X., Chen, L. & Shen, C. Hierarchical adaptive deep Convolution neural network and its application to bearing fault diagnosis. Measurement 93, 490–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2016.07.054 (2016).

Iqbal, M. & Madan, A. K. CNC machine-bearing fault detection based on convolutional neural network using vibration and acoustic signal. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 10 (5), 1613–1621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42417-022-00468-1 (2022).

Mishra, R. K., Choudhary, A., Fatima, S., Mohanty, A. R. & Panigrahi, B. K. A fault diagnosis approach based on 2D-vibration imaging for bearing faults. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 11 (7), 3121–3134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42417-022-00735-1 (2023).

Vashishtha, G. et al. A roadmap to fault diagnosis of industrial machines via machine learning: a brief review. Measurement 116216 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2024.116216 (2024).

Chauhan, S. et al. Optimal filter design using mountain gazelle optimizer driven by novel sparsity index and its application to fault diagnosis. Appl. Acoust. 225, 110200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2024.110200 (2024).

Vashishtha, G. et al. Optimization of spectral kurtosis-based filtering through flow direction algorithm for early fault detection. Measurement 241, 115737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2024.115737 (2025).

Patil, A. P., Mishra, B. K. & Harsha, S. P. Fault diagnosis of rolling element bearing using autonomous harmonic product spectrum method. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part K: Journal of Multi-body Dynamics, 235(3), 396–411, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1177/1464419321994986

Wang, Z. et al. Application of parameter optimized variational mode decomposition method in fault diagnosis of gearbox. IEEE Access. 7, 44871–44882. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2909300 (2019).

Yi, C., Lv, Y. & Dang, Z. A fault diagnosis scheme for rolling bearing based on particle swarm optimization in variational mode decomposition. Shock Vib. 2016 (1), 9372691. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/9372691 (2016).

Kiranyaz, S. et al. 1D convolutional neural networks and applications: A survey. Mech. Syst. Signal. Process. 151, 107398–. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2020.107398 (2021).

Gao, B. & Pavel, L. On the properties of the softmax function with application in game theory and reinforcement learning. Preprint at https://arXiv/org/1704.00805 (2017).

Van Den Oord, A. et al. Wavenet: A generative model for raw audio. Preprint at https://arXiv/org/1609.03499, 12 (2016).

Kumar, R. & Anand, R. S. A deep learning-based CNN-GRU prediction model for early fault diagnosis in rolling ball bearings. Neural Comput. Applic. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-025-11293-4 (2025).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9 (8), 1735–1780 (1997).

Bai, S., Kolter, J. Z. & Koltun, V. Convolutional sequence modeling revisited (2018).

Rumelhart, D. E., Hinton, G. E. & Williams, R. J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 323 (6088), 533–536 (1986).

Bengio, Y., Courville, A. & Vincent, P. Representation learning: A review and new perspectives. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 35 (8), 1798–1828 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by FEDER/Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities/Junta de Andalucía/State Research Agency/CDTI under the following grants: Data-pl (PID2022-138486OB-I00), TASOVA PLUS Research Network (RED2022-134337-T), and AquaIA (GOPG-SE-23-0011). Also, part of this work was partially supported by a grant from the University of Seville under the VI PPIT-US 2020.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Manipal University Jaipur.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VP: conceptualization, supervision, methodology, formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft. SL: methodology, Investigation, formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft. MB: methodology, Investigation, supervision, writing review and editing. SSM: investigation, visualization and validation. SPH: supervision, writing review and editing. AKS: writing review and editing, Investigation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Parmar, V., Layek, S., Bhushan, M. et al. Advanced deep learning approach for the fault severity classification of rolling-element bearings. Sci Rep 15, 34353 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16895-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16895-5