Abstract

This paper explores the application of deep learning (DL) techniques in landscape design and plant selection, aiming to enhance design efficiency and quality through automated plant leaf image recognition (PLIR). A novel framework based on Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and Fully Convolutional Network (FCN) is proposed. This framework integrates multi-scale feature fusion, attention mechanisms, and object detection technologies to improve the recognition of landscape elements and the selection of plant leaves. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed DL framework significantly improves performance in landscape element classification tasks. Specifically, the enhanced FCN model achieves a 4.5% improvement in classification accuracy on the Sift Flow dataset, while fine-grained PLIR accuracy increases by 4.8%. Furthermore, the strategy combining object detection and FCN-based image segmentation further boosts accuracy, reaching 90.4% and 88.7%, respectively. These results validate the model’s effectiveness in practical simulations, highlighting its innovative contribution to the digitalization and intelligent advancement of landscape design. The key innovation of this paper lies in the first application of multi-scale feature fusion and attention mechanisms within the FCN model, effectively improving the segmentation capability of complex landscape images. Moreover, background noise interference is reduced by using object detection techniques. Additionally, a domain-adaptive transfer learning strategy and region-weighted loss function are designed, further enhancing the model’s accuracy and robustness in plant classification tasks. Through the application of these technologies, this paper not only advances the field of landscape design but also provides technical support for biodiversity conservation and sustainable urban planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid progress of deep learning (DL) artificial neural networks has propelled their extensive utilization in computer vision, drawing considerable interest from academic and industrial spheres. Within this wave, landscape design, an interdisciplinary field bridging art and science, is progressively embracing digitization trends. However, conventional landscape design methodologies predominantly hinge on manual expertise and intuitive sensibilities, such as subjectivity, reliance on experience, resource and time limitations, and sustainability issues1. The decisions made by landscape designers are often influenced by subjective aesthetic viewpoints and personal experiences, which can lead to a lack of objectivity and consistency in design outcomes. The landscape design process requires significant time and resources, including land, plants, materials, and labor. Achieving the ideal landscape within limited budgets and timeframes can be challenging. Given the threats posed by climate change and ecosystems, sustainability has become a key element of landscape design. However, assessing and optimizing the environmental impact of designs is often challenging.

In modern landscape design, the automated identification and selection of suitable plants are key to improving design efficiency and quality2. In the field of landscape design, plant selection traditionally hinges on manual annotation and expert knowledge, processes prone to subjectivity and time constraints. This paper centers on automating the recognition of plant leaf images, offering a scientific and efficient approach to plant selection. The automation not only streamlines the designer’s workload but also broadens the spectrum of available plant choices, thereby nurturing creative design possibilities. DL can provide designers and planners with new tools and methods to improve the design process and the final landscape outcomes. Plant selection is a critical component of landscape design, impacting not only the aesthetics and environmental sustainability of the landscape but also factors like plant growth, resilience, and maintenance difficulty. Traditional plant selection relies on expertise and professional knowledge, whereas DL can leverage large plant databases and image recognition technology to assist landscape designers in choosing plant species that are suitable for specific projects, considering factors such as climate, soil, and maintenance requirements, thereby enhancing plant survival rates and aesthetic value3. Traditional rule-based image processing methods are increasingly inadequate for meeting the demands of complex scenarios. DL, particularly Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and Fully Convolutional Network (FCN), has achieved remarkable results in image recognition tasks. However, existing methods still struggle with insufficient accuracy and interference from background noise when handling complex landscape images. To address these challenges, this paper proposes a novel DL framework based on CNN and FCN. It integrates multi-scale feature fusion, attention mechanisms, and object detection techniques to enhance the recognition of landscape elements and the selection of plant leaves. By effectively combining information across different scales, the proposed framework improves the segmentation capability of complex landscape images, while the attention mechanism increases the model’s focus on key features. Additionally, the strategy of integrating object detection with image segmentation significantly reduces background noise interference, thereby improving the accuracy of plant leaf image recognition (PLIR).

This paper proposes a novel framework based on CNN and FCN architectures. It integrates multi-scale feature fusion, attention mechanisms, and a hybrid approach combining image classification and object detection to enhance the recognition of landscape elements and plant selection. The multi-scale feature fusion module integrates information from convolutional feature maps at different levels. It combines multi-scale data through methods such as weighted averaging. This enhances the model’s ability to recognize and segment various elements in complex landscape images. The encoder of the FCN model incorporates a channel attention mechanism based on Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks. The decoder includes a spatial attention mechanism, further enhancing the model’s focus on critical features in landscape element recognition. Key landscape elements are identified using the Faster Region Convolutional Neural Network (Faster R-CNN), which generates candidate bounding boxes. These regions are then input into the FCN for fine-grained image segmentation. This approach reduces the impact of background noise, improves the accuracy of PLIR, and provides more precise boundary and detail handling for landscape elements. To address the unique characteristics of plant leaf images and the practical needs of landscape design, a domain-adaptive transfer learning (TL) strategy is developed. During the transfer process, in addition to traditional fine-tuning, multi-level adjustments are applied based on the visual features of plant leaves, resulting in higher accuracy and robustness of the model in plant classification tasks. In the design of the loss function, a region-weighted loss function is designed to assign different weights to various landscape elements. During training, rare landscape elements (like certain plant species) are given higher weights, allowing the model to focus more on these elements and enhance overall recognition performance. Through the optimization and innovation of these classical methods, a new DL framework is proposed. It aims to advance the intelligent process of digital landscape design, particularly in the segmentation of complex landscape images and plant recognition.

This paper consists of the following five sections. Section 1 is the introduction, which primarily presents the background and main issues of this paper, proposes the research methods and approaches, and outlines the main contributions of this paper. Section 2 is the related studies, which analyzes relevant literature on the use of DL in image recognition technology and highlights the novelty of this paper. Section 3 is the research method, which compares the advantages and disadvantages of traditional image segmentation algorithms and analyzes the working principles of CNN models. Additionally, Sect. 3 proposes a semantic segmentation model based on FCN and a TL-based PLIR model to achieve high-precision identification of plant leaves. Section 4 is the experimental performance evaluation, which examines the efficacy of the TL-based PLIR models through comparative experiments. Section 5 is the conclusion, which summarizes the research findings and the main contributions of this paper, discusses the study’s limitations, and provides prospects for future work.

Related studies

The method of using DL to process images has been studied in all walks of life. Ngo et al. (2021) proposed a method of deconvolution data to improve image quality, training a CNN. Satellites with specific patterns are used to calibrate the images collected at the site to estimate the parameters of the point spread function. Performing image deconvolution is used to obtain improvements in signal-to-oise ratio (SNR) and modulation transfer function4. There is no large data set for medical images. The DL algorithm model cannot be used to process images better. Chlap et al. (2021) used data enhancement to increase the training dataset size. They verified that this method could improve the model’s performance on a dataset that had not been seen before5. Sarp et al. (2021) introduced an automated approach for detecting and segmenting floods using mask area CNN and generative adversarial network. This approach is employed for identifying floods depicted in the image. They found that the CNN model’s flood detection and segmentation performance based on mask area was better6.

Chen and Jin (2022) utilized image recognition technology with intelligent sensors to establish a preschool education system for children, achieving interactive and visual learning. Compared to traditional preschool education systems, it achieved a higher recognition rate with an overall accuracy of 85.16%, demonstrating better teaching efficiency and interactivity7. This paper applied image recognition technology to education, harnessing its potential in a greater capacity. In plant disease identification, Jiang et al. (2021) collected 40 images of three types of rice leaf diseases and two types of wheat leaf diseases, enhancing the images and aiming to improve the Visual Geometry Group (VGG)-16 model based on multi-task learning. The results showed an accuracy rate of 97.22% for rice leaf diseases and 98.75% for wheat leaf diseases8. This paper provides a reliable approach to identifying various plant leaf diseases.

Especially concerning the recognition of plant leaves, traditional methods demand a large amount of sample data, whereas in reality, plant leaf databases are often limited to small samples. Thus, achieving accurate plant recognition in scenarios with small sample data becomes a challenge. Kaur et al. (2023) utilized a CNN model, specifically a modified InceptionResNet-V2, combined with TL methods to identify diseases in tomato leaf images9. This illustrates the potential and effectiveness of DL techniques in the field of plant disease detection. Min et al. (2023) proposed a data augmentation method based on image-to-image translation models and used experiments to demonstrate that this augmentation method could further enhance the performance of plant early diagnosis classification models10. Grondin et al. (2023) introduced two densely annotated image datasets for boundary box, segmentation mask, and keypoint detection to assess the potential of vision-based approaches11. Deep neural network (DNN) models trained by Grondin et al. achieved good performance on these datasets, with tree detection accuracy reaching 90.4%, tree segmentation accuracy reaching 87.2%, and keypoint estimation achieving centimeter-level accuracy. Khanna et al. (2024) developed a new model called PlaNet for plant disease identification and classification. The results suggested that the proposed PlaNet model performed efficiently in leaf identification and classification12. In various test experiments, the model’s average performance reached an accuracy of 97.95%. Their study indicated that DL-based systems could rapidly and accurately classify different types of plant leaves, all demonstrating excellent performance. Reddy et al. (2024) developed a plant leaf image extraction and evaluation model based on the DNN, which performed well on the validation dataset, achieving classification accuracies ranging from 96 to 99% for specific categories13. Furthermore, some early studies focused on exploring the performance of single models in plant recognition and landscape element recognition, but lacked in-depth research on comparing different models and the impact of TL on model performance. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a detailed analysis and comparison of the application of different TL models in plant recognition and landscape design. Lidberg et al. (2023) introduced a new DL-based method for mapping forest drainage ditches at a regional scale. The model correctly mapped 86% of drainage channels in test data14. Chen et al. (2024) expanded the indicators of traditional village public space landscape features by incorporating multidimensional indicators such as landscape visual attraction elements and landscape colors15. The research results demonstrated that the accuracy of the aesthetic perception assessment model integrated with multidimensional landscape feature indicators was significantly improved. In the open spaces of traditional villages, the public preferred scenes with a higher proportion of trees, relatively open spaces, mild and uniform tones, suitable mobility, and scenes that evoked restoration and tranquility. Their study provided assurance for effectively utilizing village landscape resources, optimizing rural landscapes, and accurately enhancing the traditional village living environment.

Regarding plant selection research, Campos-Leal et al. (2022) proposed a CNN-based plant classification method that achieved accurate species classification using a pre-trained VGG16 network16. However, this method exhibited weaknesses in capturing the fine-grained features of plant leaves, particularly in complex environmental settings, where background noise negatively affected the model’s classification accuracy. In contrast, this paper integrates multi-scale feature fusion and attention mechanisms into the FCN framework, which enhances the recognition of plant leaves in complex scenes. By incorporating contextual information and fine-grained regional focus, the model’s accuracy is significantly improved. In terms of image segmentation, Ozturk et al. (2020) demonstrated substantial advancements in pixel-level image segmentation using FCN, which had been widely applied to natural landscape and urban image segmentation tasks17. However, traditional FCN models struggle with complex landscape images, particularly in segmenting fine details such as plant edges and leaves. To address this, this paper incorporates SE blocks and spatial attention mechanisms into the FCN, improving its focus on critical regions and achieving enhanced fine-grained segmentation results. Wang et al. (2022) developed the Faster R-CNN object detection model, achieving notable results in identifying various plant parts18. However, when applied to complex backgrounds, Faster R-CNN may suffer from false positives or missed detections. This paper addresses this limitation by integrating Faster R-CNN with FCN. Faster R-CNN is used to generate candidate bounding boxes, which are then refined through fine-grained segmentation by FCN, effectively reducing the influence of background noise on recognition outcomes.

Although prior research has made significant contributions to plant recognition and image segmentation, several limitations persist. Most existing methods focus on coarse-grained classification and struggle to capture subtle differences in plant leaves, particularly under complex background conditions. This results in insufficient fine-grained recognition capabilities. To overcome this issue, this paper introduces multi-scale feature fusion and SE-based channel attention mechanisms to enhance the model’s ability to extract fine-grained features. Furthermore, traditional image segmentation methods are susceptible to interference from complex backgrounds, leading to unclear plant boundaries and reduced accuracy. To effectively reduce the impact of background noise, this paper combines Faster R-CNN with FCN. It not only enhances plant recognition accuracy but also improves the delineation of landscape element boundaries. In addition, many DL methods face computational bottlenecks, especially when processing large datasets, where inference speed and memory consumption become critical issues. Future research could enhance computational efficiency by integrating model compression and inference acceleration techniques. To resolve these issues, this paper proposes several innovations. By combining low-level and high-level features, the model enhances its capability to recognize and segment complex landscape elements. It achieves particularly notable results in diverse elements such as water features and vegetation. SE-based channel attention mechanisms are introduced into the FCN model, and spatial attention mechanisms are added to the decoder, further improving the model’s performance in fine-grained segmentation tasks. By integrating object detection (Faster R-CNN) with image segmentation techniques, the paper significantly reduces the impact of background noise and improves the accuracy of PLIR. Moreover, a domain-adaptive TL strategy is designed, involving multi-level fine-tuning based on the visual characteristics of plant leaves. It results in higher accuracy and robustness of the model in plant classification tasks. Through these innovations, this paper overcomes the limitations of previous methods in image segmentation and plant recognition, and provides a novel and intelligent solution for digital landscape design.

Research model

Image recognition technique and traditional image segmentation algorithm

The application of digital image processing techniques extends across various domains, including transportation, industry, biology, and other fields. Specifically within landscape design, these technologies are harnessed for the manipulation of natural landscape photographs19. First, landscape photos are transferred to the computer, and programs are obtained. Subsequently, the programming information is input into the landscape element recognition system to realize the automatic recognition of landscape elements. The core part of this process is the image recognition system20. An image recognition system is a system based on computer vision and machine learning technologies used to identify and classify objects, items, or scenes within images. The composition of the image recognition system is shown in Fig. 1.

In Fig. 1, typically, an image recognition system consists of four main components: image pre-processing, image feature extraction, scene element recognition, and output results. Image pre-processing is the first step in an image recognition system aimed at converting the raw image into a form suitable for analysis. Pre-processing tasks include noise removal, resizing and adjusting the image’s resolution, contrast enhancement, color normalization, and more. The enhancement of image feature extraction and recognition accuracy in subsequent stages is facilitated through pre-processing. Subsequently, during the image feature extraction phase, the system isolates valuable features from the pre-processed image. These features can include information such as edges, corners, textures, color histograms, shapes, and more. The goal of feature extraction is to convert image information into numerical or vector form, making it understandable and processable by machine learning algorithms. Scene element recognition is the core part of an image recognition system and an area where DL technologies shine. In this stage, machine learning algorithms use the extracted features from the image to identify objects, items, or scenes within the image. This may cover multiple categories, such as animals, traffic signs, buildings, natural landscapes, and more. DL models such as CNN and Recurrent Neural Network models are frequently employed for proficient image classification and recognition tasks. The Output Result is the final step, where the recognition results are presented to users or other applications. This is typically presented in the form of text or visualization, indicating what objects or scenes have been identified in the image. The output results can be integrated with other information for automated decision-making, system monitoring, or enhanced user experiences21. An image recognition system goes through these four steps, transforming visual information into understandable and useful data, enabling automated image recognition and classification, and can excel in the field of landscape design and plant selection.

Traditional landscape image segmentation algorithms are based on These methods aim to partition images into different regions or objects. Common traditional segmentation algorithms include threshold segmentation, region growing, region segmentation, and edge detection22. Table 1 illustrates the comparison between various algorithms23.

In Table 1, these traditional segmentation algorithms typically rely on features such as brightness, color, and texture of the image for segmentation. However, they may be sensitive to noise and changes in lighting conditions and often require manual selection of parameters or seed points. With the development of DL technologies, modern segmentation methods, especially CNN and semantic segmentation models, have made significant advancements in image segmentation tasks. This is because they can automatically learn complex image features, thereby improving segmentation accuracy and robustness.

Image semantic segmentation model of FCN

CNN is a class of artificial neural network models used for image processing, pattern recognition, and DL tasks. CNN draws inspiration from the human visual system and has achieved significant breakthroughs in the field of image processing. They have demonstrated outstanding performance in various applications, including image classification, object detection, semantic segmentation, and facial recognition. In CNN, one neuron can correspond to others within its coverage to achieve weight sharing and process large images24. The neural network can effectively reduce the number of learning parameters in training and improve the algorithm’s performance. The structure of CNN is shown in Fig. 225.

In Fig. 2, the CNN represents a hierarchical architecture comprising multiple convolutional, pooling, and fully connected layers, mirroring the cognitive processes involved in visual information processing within the human brain. Firstly, the convolutional layer, serving as the foundational element of the CNN, employs convolutional kernels to filter the input image, extracting pertinent features. This operation is instrumental in capturing local information and spatial relationships, facilitating the effective learning of features for visual tasks. Secondly, the pooling layer diminishes the spatial dimensions of the image, concurrently mitigating computational complexity and enhancing resilience to image features. Common pooling operations, such as max pooling and average pooling, sample the output of convolutional layers to distil more significant features. Lastly, the fully connected layer maps the features extracted by convolutional and pooling layers to the output layer, culminating in the final classification or recognition of the image. Each neuron in the fully connected layer establishes connections with all neurons in the preceding layer, forming a comprehensive perception structure. The amalgamation and stacking of these layers within CNN construct its deep architecture, empowering the model to make substantial strides in comprehending intricate image features and abstract representations. Convolutional layers execute filtering operations through defined convolutional kernels—small windows or filters sliding over the input image, transforming it into a series of feature maps. This process involves element-wise multiplication of the convolutional kernel with the corresponding region of the input image, followed by accumulation to yield the output of the convolution operation. A pivotal characteristic of this operation is weight sharing, where the weight parameters of the convolutional kernel remain consistent throughout its traversal of the entire input image. This weight-sharing mechanism minimizes network parameters, enhances model efficiency, and imparts translational invariance to the network. The convolutional layer employs diverse convolutional kernels to learn various features of the image, including edges, textures, and shapes. These acquired features undergo progressive abstraction as the network’s depth increases, culminating in higher-level representations that afford the network an abstract understanding of the input image. Following the convolutional layer, an activation function, such as the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU), is commonly integrated to introduce non-linearity and amplify the expressive capacity of the network. Furthermore, pooling layers are consistently interleaved with convolutional layers, facilitating the downsampling of feature maps. This process serves to systematically diminish data dimensions, enhance computational efficiency, and retain crucial features in the network26. The working process of the convolution layer is shown in Eq. (1).

In Eq. (1), l is the number of convolution layers. \(\:f\) is a nonlinear activation function. \(\:{t}_{b}^{l}\) is the b-th characteristic map of convolution layer l. \(\:{s}_{ab}^{l}\) is the convolution kernel. \(\:{A}_{b}\) is the set of input characteristic graphs. \(\:{\alpha\:}_{b}^{l}\) is the offset term. The pooling layer functions by specifying the size of a pooling window and systematically traversing it over the feature map. This window, a fixed-size region, moves incrementally across the feature map, conducting an aggregation operation on the values within each window. Commonly employed pooling operations include Max Pooling and Average Pooling. In Max Pooling, values within the pooling window are substituted with the maximum value, while Average Pooling replaces them with the average value within the window. The primary objective of pooling is to retain crucial information while diminishing the dimensions of the feature map, thereby enhancing computational efficiency. The pooling layer’s operations enable the network to reduce data size without compromising features. This reduction is instrumental in minimizing the number of network parameters, mitigating computational complexity, preventing overfitting, and bolstering the model’s robustness. Moreover, the pooling layer contributes to imparting a degree of invariance to translation and small deformations within the network. In the CNN structure, convolutional layers and pooling layers conventionally alternate. The iterative stacking of these layers facilitates the network’s progressive acquisition of increasingly abstract feature representations. Its working process is shown in Eq. (2)27.

In Eq. (2), \(\:{x}_{b}^{i}\) is the b-th feature map in pooling layer i. \(\:{u}_{b}^{l}\) is the value after sampling. down (*) denotes the subsampling function. Each neuron within the fully connected layer establishes connections with all neurons in the preceding layer, creating a globally connected structure that allows the network to consider all features in the input image and amalgamate them into a reduced-dimensional output. Each connection is assigned a weight parameter throughout this connectivity process, signifying its significance. These weight parameters are iteratively learned during the network’s training using optimization algorithms such as backpropagation and gradient descent. This implies the automatic adjustment of connection weights to better align with the training data. Furthermore, the output of each neuron is computed by multiplying the output of neurons in the preceding layer by the weights of their connections and adding a bias. This introduces non-linearity by applying an activation function, thereby enhancing the network’s capacity to learn intricate features and relationships. The ultimate output of the fully connected layer undergoes processing through the Softmax function. This transformation converts neuron outputs into a distribution representing various categories’ probabilities. Consequently, the network is equipped to perform multi-class classification on input images, furnishing the probability associated with each category. The principal role of the fully connected layer is to integrate features extracted by convolutional and pooling layers, culminating in a high-level abstract representation of the input image. Subsequently, it conducts classification based on the learned weight parameters. This pivotal process facilitates the network’s ability to discern and categorize complex patterns, contributing to its overall effectiveness in image classification tasks28. In applications such as landscape design and plant selection, which necessitate the preservation of spatial structures and detailed information, CNN models employ convolution and pooling operations in image processing. However, this approach often leads to the loss of information regarding the original image size29. The fundamental innovation of the FCN model lies in replacing the fully connected layers of traditional CNN models with a fully convolutional structure. Within the FCN framework, the concluding layers of the network employ transposed convolution operations. This strategic choice serves to restore the spatial dimensions of the feature maps to the size of the original input image. This design ensures that the network retains crucial spatial information in the output, thereby better aligning with the demands for detailed image representation. Furthermore, FCN introduces the concept of skip connections, integrating features from intermediate layers with upsampled features. This approach proves instrumental in capturing features at different hierarchical levels more effectively, thereby enhancing the model’s perceptual capabilities. The FCN’s innovative design addresses the limitations associated with traditional CNN models, particularly in tasks requiring nuanced spatial information and detailed image analysis. The structure of FCN is illustrated in Fig. 330.

In Fig. 3, the FCN image semantic segmentation model comprises three primary steps: image pre-processing, feature extraction and fusion, and classification. This discussion focuses particularly on the feature extraction and fusion section, where the FCN model employs specific structures to achieve this process. The feature extraction and fusion section is intricately composed of three main components: the feature extraction network, upsampling layers, and skip connections. Within the FCN model, the core responsibility of the feature extraction network is to discern essential features from the input image. This stage typically incorporates a sequence of convolutional layers meticulously designed to capture semantic features inherent in the image. Each convolutional layer transforms the original image into feature maps, where each map corresponds to specific semantic features such as edges, textures, and shapes. Upsampling layers play a crucial role in enlarging low-resolution feature maps to match the size of the input image through upsampling operations. Simultaneously, skip connections facilitate the fusion of feature information from different levels, allowing for the amalgamation of high-level and low-level features. This concurrent capture of local and global semantic information contributes significantly to enhancing the performance of the segmentation model, ensuring a more comprehensive understanding of the input image’s intricate features.

A fundamental distinction between the FCN and traditional CNN lies in FCN’s unique capacity to operate without a fixed input image size, directly classifying individual pixels within the image. Notably, FCN diverges from conventional CNN models by featuring a final layer that is a convolutional layer rather than a fully connected layer, resulting in a segmented image as the output. In this context, the convolutional layer assumes the role of the fully connected layer, a process referred to as convolution. Subsequent to convolution and pooling layers, the downsized image undergoes a progressive restoration to its original size by incorporating upsampling layers, specifically transpose convolution. The conclusive prediction for each pixel in the output image is determined by selecting the maximum value, denoting probability, across all pixels at that position across all images for classification. The FCN model is trained via supervised learning, utilizing the ReLU activation function. To forestall overfitting, a Dropout layer is integrated into the model, zeroing certain neuron outputs, thereby enhancing the model’s generalization and robustness. This comprehensive process encapsulates the core concept and workflow of the FCN image semantic segmentation model, showcasing its unique adaptability to varying input sizes and its ability to classify individual pixels precisely.

The variants of FCN include FCN-8s, FCN-16s, and FCN-32s, aimed at improving the performance and accuracy of the segmentation model. The numbers 32s, 16s, and 8s represent the upsampling strides, meaning the feature maps are enlarged by a factor of 32, 16, and 8, respectively. A lower stride typically implies higher-resolution segmentation results but also requires more computational resources. FCN-32s is one of the earliest variants of FCN, utilizing a fully convolutional structure and upsampling to enlarge low-resolution feature maps to the size of the input image. It uses skip connections to fuse feature information from different levels, making the segmentation results smoother. FCN-16s builds upon FCN-32s by introducing more feature fusion layers to enhance segmentation quality. It merges feature maps from both shallow and deep levels through skip connections, allowing the model to capture semantic information from different levels. FCN-8s is an extension of FCN-16s, introducing additional feature fusion layers and upsampling operations. It fuses feature information from more levels through skip connections to improve segmentation accuracy. These models have achieved significant success in image semantic segmentation tasks, especially in fields such as autonomous driving, medical image analysis, remote sensing image analysis, and real-time segmentation. However, their application in the field of landscape design is relatively limited. Therefore, this paper applies three variants of FCN to landscape design to create outdoor environments that are more innovative, sustainable, and aesthetically valuable.

Building upon traditional CNN and FCN models, this paper introduces a multi-scale feature fusion module. This module effectively integrates multi-scale information by combining convolutional feature maps from different layers. Specifically, through operations such as weighted averaging and max pooling, information is consolidated between low-level and high-level feature maps, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to recognize and segment various elements in complex landscape images. For instance, when processing water landscape elements, low-level feature maps focus more on texture and edge information, while high-level feature maps are better at capturing semantic details. By fusing both, the model can more accurately identify and segment water features. In the encoder section of the FCN model, a channel attention mechanism based on SE blocks is introduced. The SE block adaptively recalibrates the weights of each channel, enabling the model to focus on more important feature channels. Additionally, a spatial attention mechanism is incorporated in the decoder section, allowing the model to focus on spatial features in important areas of the image. This enhanced attention mechanism significantly improves the model’s focus on complex landscape elements, particularly in fine-grained segmentation tasks. To further improve the accuracy of landscape element recognition, this paper combines object detection technology (Faster R-CNN) with the FCN image segmentation model. First, Faster R-CNN is used to detect key landscape elements in the image by generating candidate bounding boxes to mark the locations of these elements. Then, these candidate regions are input into the FCN model for fine-grained image segmentation. This method effectively reduces the interference of background noise while enhancing the model’s accuracy in capturing the boundaries and details of landscape elements, showing particularly high accuracy in PLIR.

TL-based PLIR model

In landscape design, plant selection is an important step, and the prerequisite for successful plant selection is the accurate identification of plants. Traditional plant recognition methods require tedious pre-processing steps, followed by feature extraction for classification. However, the extracted features often lack consistent quality standards, leading to classification inaccuracies31. In contrast, CNN can directly take raw plant images as input without the need for cumbersome pre-processing. However, CNN requires a large number of training samples to perform well, while plant leaf databases are typically small-sample data. Therefore, the experiment chooses to use TL methods for classification32. TL is a machine learning approach that leverages existing knowledge to solve problems in different but related domains, with the goal of effectively transferring knowledge to relevant domains33,34,35. The applied TL-based network models are AlexNet, VGG-16, and Inception V3 models36, as shown in Fig. 4.

In Fig. 4, AlexNet consists of 5 convolutional layers and three fully connected layers. Max-pooling layers are placed between the convolutional layers to reduce the size of feature maps. It uses the ReLU activation function and applies Dropout in the first two fully connected layers to prevent overfitting. The final fully connected layer uses softmax for classification37. VGG-16, on the other hand, comprises 13 convolutional layers and three fully connected layers. Similar to AlexNet, it employs max-pooling layers between convolutional layers. VGG-16 is characterized by its simple hierarchical structure, where all convolutional and fully connected layers use the same-sized convolutional kernels (typically 3 × 3 kernels). It employs the ReLU activation function and enhances the network’s non-linearity by stacking multiple convolutional layers, thereby improving image classification performance38. Inception-V3 consists of multiple Inception modules, each containing different-sized convolutional kernels, such as 1 × 1, 3 × 3, and 5 × 5 kernels, as well as pooling layers. It uses Dropout to prevent overfitting. The design of Inception modules allows the network to have greater width and depth, effectively capturing features at various scales and levels, resulting in outstanding performance in image classification and recognition tasks39. All three of these models have achieved significant success in the field of computer vision. TL can leverage the pre-trained model weights of these models and adapt them to specific tasks through fine-tuning, thereby improving the model’s performance on new tasks. These models have been widely applied in various image processing tasks, including image classification, object detection, and image segmentation. In this paper, these three TL-based models are applied to PLIR to accurately select the desired plants for landscape design through improved PLIR.

This paper proposes a domain-adaptive TL strategy, specifically designed for PLIR tasks. In addition to the traditional fine-tuning operations, the strategy involves multi-level fine-tuning of the visual features of plant leaves. Specifically, during the TL process, different network layers are fine-tuned for the image features of different plant categories, further enhancing the model’s performance in plant classification tasks. Compared to traditional TL methods, this strategy effectively improves the model’s accuracy and robustness in new domains, such as PLIR in landscape design. To improve the model’s accuracy in recognizing rare landscape elements, a region-weighted loss function is introduced. In this loss function, different weights are assigned to landscape elements based on their rarity. For rare landscape elements (such as certain plant species), higher weights are given, ensuring that the model focuses more on recognizing these rare elements during training. This approach helps the model effectively address the class imbalance problem in landscape element recognition, thereby enhancing the overall recognition accuracy.

In the experiment, all samples in the plant leaf image dataset are randomly horizontally and vertically flipped, resulting in a dataset expanded by three times its original size. Subsequently, the expanded dataset is divided into training and testing sets proportionately. Then, the pre-trained parameters of the AlexNet, VGG-16, and Inception-V3 models on ImageNet are transferred to the plant leaf image dataset, with only the last fully connected layer being replaced.

Landscape elements and plant leaf classification evaluation indicators

Landscape elements are divided into six categories: sky, water, mountains, animals and plants, buildings, and roads. The FCN is compared with the actual results, the model is analyzed for performance accuracy, and the pixel error in the landscape image is counted. Then, the result of the feature classification in the landscape image is judged. The overall precision of the model is calculated, as shown in Eq. (3)40.

In Eq. (3), \(\:{n}_{aa}\) refers to the number of pixels belonging to class a and judged correctly. \(\:{s}_{a}\) is the total number of pixels belonging to class an element, \(\:{s}_{a}=\sum\:_{a}{n}_{ab}.\) \(\:{n}_{ab}\) is the number of pixels belonging to class a but judged to be class b elements. The accuracy of class a landscape element is that they belong to class a landscape element, and those results are correct, as shown in Eq. (4)41.

The calculation method of average accuracy Q is shown in Eq. (5).

In Eq. (5), \(\:{n}_{z}\) is the total number of landscape element categories, \(\:{n}_{z}=6\). IoU is used to predict the intersection of the correct landscape and the union of category and original pixels, as shown in Eq. (6).

The performance of the TL-based PLIR model is evaluated by the accuracy of the test set, as shown in Eq. (7).

In Eq. (7), M is the number of correct plant leaf images tested. N is the total number of leaf images of tested plants.

Experimental results and discussion

Datasets collection

The dataset used in this landscape image recognition experiment is the Sift Flow dataset. It is a standard dataset for scene understanding and image segmentation tasks, used to evaluate and compare the performance of different algorithms. The Sift Flow dataset was created by researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles. The dataset’s images were collected from the internet, including urban landscapes, streets, indoor, and outdoor scenes. It comprises approximately 2,688 color images, each of which has been semantically annotated at the pixel level. Each pixel has been assigned a semantic category, such as ‘sky,’ ‘road,’ ‘tree,’ and so on. There are a total of 33 different semantic categories, covering common objects and regions in urban scenes. Among them, 2388 images are used as training sets, and the remaining 300 images are used as test sets.

Plant selection is a crucial step in landscape design as it directly influences the aesthetics, ecological balance, and functionality of the landscape. The process of plant selection typically involves several steps: First, based on the requirements of the landscape design and the environmental conditions, the desired plant characteristics are determined. This includes considering the height, shape, color, growth habits, and adaptability to soil and climate of the plants. For example, in areas requiring dense greenery, rapidly growing and lush foliage plants may be chosen. In places where color contrast is desired, plants with vibrant flowers or foliage can be selected. Moreover, plants that match the theme and style of landscape design are chosen in accordance with the design concept. Different plants convey different feelings and emotions through their morphology and characteristics, so selection should be based on the design objectives. For instance, for a natural, wild landscape style, wildflowers or native plants may be chosen, while for a modern minimalist style, plants with simple, clean lines may be preferred. Additionally, it is essential to consider the growth characteristics and maintenance requirements of the plants to ensure they can thrive in the environment and are easy to manage and maintain. This includes factors such as cold hardiness, drought tolerance, and light and water requirements.

Image recognition technology can serve as an auxiliary tool to assist designers in quickly and accurately identifying and selecting suitable plants. After capturing or collecting plant images, image recognition algorithms can swiftly identify the species, characteristics, and attributes of plants. For example, image recognition technology can be used to analyze the shapes of plant leaves and the colors of flowers, thereby assisting designers in plant selection. Common criteria for plant selection in landscape design include compatibility with the design style, harmony with the surrounding environment, and ease of maintenance and management, among others. By comprehensively considering these factors, designers can choose plants that not only meet the design requirements but also thrive and enhance the aesthetic appeal of the actual environment, thereby achieving the desired effects of landscape design.

The plant leaf image dataset is a database collected from the Intelligent Computing Laboratory (ICL) of the Hefei Institute of Machinery, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The database includes 220 plant leaf images. Each plant leaf has a different number of images. In the experiment, 42 plant leaves containing more than 50 images are selected as the training set, totaling 4772 images. Additionally, the selected blade image is flipped horizontally and vertically to augment the dataset. Finally, the total number of expanded dataset samples is 14,322. The data set is divided into the training set and test set in a 4:1. The training set consists of 11,457 leaf images, and the test set consists of 2865 leaf images.

To enhance the model’s generalization ability in real-world landscape design scenarios, this paper builds upon the existing Sift Flow and ICL datasets by incorporating several more complex and diverse landscape design datasets. In addition to the Sift Flow and ICL datasets, it introduces large-scale datasets such as ADE20K and Cityscapes, which cover more complex landscape elements and various scene layouts. This makes the model more closely aligned with the practical needs in real-world landscape design. Regarding data augmentation, in addition to traditional image-flipping operations, more complex and diverse augmentation strategies are introduced. The specific augmentation techniques include random rotation, random cropping, color transformations (such as random variations in brightness, contrast, and saturation), adding Gaussian noise, random scaling, and affine transformations, among others. These augmentation methods help the model learn a wider range of scene features under different environmental conditions, thereby improving its robustness for real-world applications.

To ensure the effectiveness and generalization capability of the proposed DL model in landscape design and plant selection tasks, a systematic validation process is conducted in the experimental section. Specifically, model training and testing follow a standard supervised learning protocol, with datasets split into training and testing sets at a 4:1 ratio. Randomized partitioning is adopted to mitigate the risk of overfitting. The model is validated from the following aspects: First, accuracy and Intersection over Union (IoU) are employed as the primary evaluation metrics to assess overall classification performance and segmentation precision, respectively. Second, a confusion matrix is constructed based on the test set to analyze category-wise prediction bias and recognition accuracy, thereby identifying errors in class-specific recognition. Third, to evaluate the model’s generalization ability across different tasks and scenarios, transfer and comparative evaluations are conducted on multiple benchmark datasets. The classification and segmentation performance of the model before and after improvement are compared to further demonstrate its adaptability in complex environments. In addition, for the task of plant leaf recognition under limited sample conditions, a TL approach is adopted. A multi-level fine-tuning process is performed on a model pretrained on ImageNet to enhance classification performance in the target domain. To further improve model robustness, data augmentation strategies—such as rotation, flipping, cropping, and noise perturbation—are applied, and the original leaf image dataset is expanded, significantly enhancing the model’s testing performance. In summary, through data partitioning, performance metrics, cross-model and cross-dataset evaluations, this paper systematically validates the proposed model from multiple perspectives, ensuring the reproducibility and scientific rigor of the experimental results.

Experimental environment

The experiment is conducted on a Windows 10 operating system with an Intel(R) Core (TM) i7-7700CPU@3.60 GHz central processing unit, 32 GB of memory, and an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1050Ti GPU. The programming environment used is JetBrains PyCharm Community Edition, and the programming language used is Python. The model construction is done using the open-source Caffe framework with the Python interface.

Hyperparameters setting

The learning rate for the FCN model is set to 10− 10, and the weight decay coefficient is set to 0.005. The parameter settings for the TL-based PLIR model are shown in Table 2.

Experimental results

Analysis of experimental results for landscape element recognition

In the training process, a single different landscape element is used as the main scene of the image training model. Each main scene element must occupy 60% of the image. The landscape images are divided into four categories: waterscape, ground scenery, biological scenery, and skyscape. Figure 5 displays the accuracy of semantic segmentation of four categories of landscape elements sampled on three types.

In Fig. 6, in the FCN-8s architecture, the semantic segmentation accuracy for each category is noteworthy: water landscapes achieve 91.79%, ground landscapes attain 90.24%, biological landscapes register 86.24%, and sky landscapes demonstrate an accuracy of 94.22%. These results signify the commendable performance of FCN-8s in accurately delineating various landscape elements. Subsequently, under the FCN-16s configuration, the semantic segmentation accuracy for each category is as follows: water landscapes 90.33%, ground landscapes 88.41%, biological landscapes 88.99%, and sky landscapes 91.48%. Although FCN-16s exhibits a slight decrease in performance for ground and biological landscapes compared to FCN-8s, it maintains high accuracy in water and sky landscapes. Lastly, within the FCN-32s structure, the semantic segmentation accuracy for each category is water landscapes 87.86%, ground landscapes 85.68%, biological landscapes 83.05%, and sky landscapes 89.37%. FCN-32s demonstrates lower accuracy across all categories in comparison to the other two structures. In summary, FCN-8s emerges as the most adept structure for semantic segmentation tasks related to landscape elements, achieving relatively high accuracy across all four categories. FCN-16s follows closely, demonstrating robust performance with a slight decrease in certain landscape categories. FCN-32s, on the other hand, exhibits comparatively lower accuracy in all categories, suggesting its limited suitability for the specified semantic segmentation tasks in this paper. The average IoU results of semantic segmentation of four categories of landscape elements sampled on three types are shown in Fig. 6.

In the FCN-8s configuration, the average IoU for each category is as follows: water landscapes attain 74.25%, ground landscapes achieve 76.15%, biological landscapes register 74.34%, and sky landscapes demonstrate an IoU of 76.38%. These results underscore that FCN-8s has achieved a commendably high average IoU for each landscape element category. Moving to the FCN-16s structure, the average IoU for each category is as follows: water landscapes 73.93%, ground landscapes 73.66%, biological landscapes 75.37%, and sky landscapes 75.3%. In comparison to FCN-8s, FCN-16s exhibits a slight decrease in IoU for water and ground landscapes but showcases improved performance in biological and sky landscapes. Lastly, within the FCN-32s structure, the average IoU for each category is: water landscapes 72.44%, ground landscapes 72.43%, biological landscapes 72.69%, and sky landscapes 74.18%. FCN-32s manifests lower average IoU in all categories compared to the other two structures. In summary, FCN-8s emerges as the more suitable structure for semantic segmentation tasks related to landscape elements, achieving a relatively high average IoU for each category. Following closely, FCN-16s demonstrates competitive performance, excelling in certain landscape categories. Conversely, FCN-32s exhibits comparatively lower average IoU across all categories, indicating its limited suitability for the specified semantic segmentation tasks in this paper. This suggests that, in terms of average IoU, FCN-8s excels in preserving and restoring object contour information for each category in the context of landscape element segmentation. The data show that the model with FCN-8s structure has the best performance. Table 3 presents the segmentation accuracy and average IoU results of different model structures across different semantic categories.

Three hundred images are tested and classified, as shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7 depicts the test set accuracy of three up-sampling structures—FCN-8s, FCN-16s, and FCN-32s. Notably, FCN-32s exhibits the lowest accuracy, representing 82.42% in mountain classification. The highest accuracy rate is 91.88% under FCN-8s. The accuracy of FCN-16s for animal and plant classification is 2.32% higher than that of FCN-8s. Except for the classification of animals and plants, FCN-8s are higher than FCN-16s in other categories, with the highest being 2.93%. The data indicates that the performance of FCN-8s is generally better than FCN-16s and FCN-32s.

In addition, Fig. 8 conducts an analysis of variance on the accuracy of landscape element classification to validate their statistical significance using three up-sampling structures: FCN-8s, FCN-16s, and FCN-32s. Through the analysis of variance, the accuracy of these three models on six landscape element classifications yielded a p-value of 0.0454, which is less than 0.05. The data indicates that there is a significant difference in the performance of these three models in landscape element recognition. Specifically, in landscape element recognition, the use of FCN-8s outperforms FCN-16s and FCN-32s. Figure 8 illustrates the changes in the loss function during the training process for different model structures. It can be observed that the loss values of all three models gradually decrease as the training iterations increase, indicating an improvement in performance during the learning process. However, it is worth noting that there are differences in the loss values among different model structures. For the FCN-8s model, the loss value decreases from an initial 0.345 to a final 0.062 as the training iterations increase. This indicates that the FCN-8s model can quickly and effectively reduce the loss during the training process, demonstrating good convergence performance. In contrast, the loss values of the FCN-16s and FCN-32s models are slightly higher than that of the FCN-8s model at the same number of training iterations. For example, after 400 iterations, the loss values of the FCN-16s and FCN-32s models are 0.128 and 0.281, respectively. This suggests that the FCN-16s and FCN-32s models have slower convergence speeds in terms of the loss function, and their performance may be slightly inferior to that of the FCN-8s model. In summary, by observing the changes in the loss function, it can be concluded that the FCN-8s model demonstrates superior performance in terms of the speed of loss reduction and convergence compared to the FCN-16s and FCN-32s models.

Analysis of the experimental results of PLIR

In order to get the effect of migration learning on the accuracy of the test set and keep other parameters the same, CNN and the three migration models are tested on the ICL database. The CNN model adopts a typical architecture consisting of 3 convolutional layers and 2 fully connected layers. Each convolutional layer is followed by a max-pooling layer. The number of filters in the convolutional layers is 32, 64, and 128, respectively, with a kernel size of 3 × 3 for all layers and a pooling kernel size of 2 × 2. The fully connected layers have output nodes of 256 and 128, respectively. The CNN model uses the ReLU activation function and performs classification through a softmax layer. During training, cross-entropy is used as the loss function, and the Adam optimizer is employed for model optimization. The experimental results are shown in Fig. 9.

In Fig. 9, the training time and accuracy of the three migration models are much higher than that of the CNN model. FCN has an FCN structure. First, in the task of image semantic segmentation, the FCN model can perform pixel-level classification and segmentation of input images end-to-end. In contrast, traditional CNN models in image classification tasks often only output category labels for the entire image, without providing fine-grained information at the pixel level. This allows the FCN model to more accurately capture detailed features of different elements when processing image recognition tasks in landscape design, thereby improving recognition accuracy. Next, in terms of training time, the FCN model trains faster. This is because the FCN model uses a lightweight network structure, avoiding the problem of too many parameters and high computational complexity caused by fully connected layers in traditional CNN models. Additionally, the FCN model adopts an end-to-end training approach, which allows it to directly learn feature representations from raw image data without the need for cumbersome manual feature extraction and preprocessing. Therefore, the FCN model can converge to better model performance more quickly within the same training time.

The model’s performance is compared across different datasets and models. To validate the generalization ability of the improved model in various scenarios, experiments are conducted on the ADE20K, Cityscapes, and Sift Flow datasets. The performances of the traditional FCN-8s, the improved FCN model (which incorporates multi-scale feature fusion, SE channel attention mechanism, and spatial attention mechanism), and the FCN + Faster R-CNN combined model (which integrates object detection and image segmentation) are compared in landscape element classification and fine-grained PLIR tasks. Table 4 presents the performance comparison of different models on various datasets. It is evident that the improved FCN model outperforms the traditional FCN-8s model in both landscape element classification and fine-grained PLIR tasks across all datasets. On the Sift Flow dataset, the improved FCN model achieves a 4.5% increase in landscape element classification accuracy and a 4.8% increase in fine-grained PLIR accuracy. This indicates that the introduction of multi-scale feature fusion and attention mechanisms effectively enhances the model’s ability to recognize complex scenes. For the more challenging ADE20K and Cityscapes datasets, the improved FCN model also shows stable improvement in both landscape element classification and fine-grained PLIR tasks. Especially on the Cityscapes dataset, the improved FCN model’s landscape element classification accuracy increases by 4.3%, and the fine-grained PLIR accuracy increases by 3.1%. This result demonstrates that, despite these datasets containing more complex scenes and background information, multi-scale feature fusion and attention mechanisms can still improve the model’s recognition accuracy. When using the combined framework of object detection (Faster R-CNN) and FCN image segmentation, the model’s performance further improves. On the Sift Flow, ADE20K, and Cityscapes datasets, the FCN + Faster R-CNN combined model achieves the highest accuracy in landscape element classification and fine-grained PLIR tasks. For instance, on the Sift Flow dataset, this combined model reaches 90.4% in landscape element classification accuracy, which is 0.7% higher than the improved FCN. In fine-grained PLIR, the accuracy reaches 88.7%, which is 2.2% higher than the improved FCN. This shows that the combination of object detection and image segmentation can effectively reduce the interference of background noise and enhance the accuracy of plant leaf boundary and detail recognition.

In order to get the effect of the number of datasets on the accuracy of the test set, the original ICL and the expanded ICL-2 datasets are trained with three migration models under the same other parameters. The experimental results are shown in Fig. 10.

In Fig. 10, the accuracy of the three migration models on the expanded dataset is higher than that of the original ICL database. After the expansion, the accuracy of the three migration models, AlexNet, VGG-16, and Inception-V3, is 5.08%, 4.79%, and 1.59% higher than before. The data show that the performance of the migration model can be improved by expanding the training data set.

Plant image classification results

Using TL methods, this paper employs TL models such as AlexNet, VGG-16, and Inception V3 to classify and recognize plant leaf images. The experiment utilizes a dataset of 220 plant leaf images collected by the ICL, involving training on 42 different types of plant leaves, totaling 4772 images. Figure 11 illustrates the classification results of different models in plant image classification. First, in terms of classification accuracy, the FCN-8 model performs the best, achieving 95.74%, followed by the CNN Inception-V3 model with an accuracy of 98.69%. This indicates that the FCN model achieves high accuracy in plant leaf classification tasks, while the CNN model also demonstrates good classification capability. Besides, regarding training loss, the FCN-8 model has the lowest training loss at 0.19, while the CNN AlexNet model has the highest training loss at 0.58. This suggests that the FCN model has lower loss during training, indicating relatively stable model training, while the CNN model has slightly higher training loss, possibly indicating some training difficulties. Lastly, in terms of average IoU value, the CNN Inception-V3 model achieves the highest IoU value at 87.29%, closely followed by the FCN-8 model with an IoU value of 85.64%. This indicates that these two models can accurately identify the contours of plant leaves in image segmentation and better preserve and restore the contour information of objects. In conclusion, based on the provided data, the FCN-8 and CNN Inception-V3 models perform excellently in plant leaf classification tasks, with high classification accuracy and average IoU values, while also having lower training loss. It makes them suitable for PLIR and image segmentation tasks in the landscape design field.

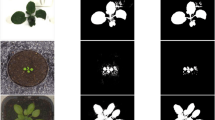

Figure 12 displays the landscape elements and PLIR results under the FCN-8s and FCN-16s models. It reveals that FCN-8s performs the best in recognizing landscape elements and plant leaves, while the category recognition of FCN-16s is slightly lower than that of FCN-8s.

Confusion matrix analysis

In this section, the confusion matrices generated by the FCN model and the Inception-V3 model on the test set are provided to evaluate the predictive accuracy of the models on each category. Table 5 shows the confusion matrix of the FCN model. The intersections between actual categories and predicted categories can be observed. In the aquatic category, 279 samples are correctly predicted as aquatic, 12 samples are incorrectly predicted as terrestrial, 5 samples are incorrectly predicted as biogenic, and 4 samples are incorrectly predicted as sky. Similarly, the prediction results for other categories are also listed in the table. Overall, the FCN model performs well in predicting different categories, with the majority of samples being correctly classified. However, there are still some misclassifications, particularly in the biogenic and sky categories.

Table 6 presents the confusion matrix for the Inception-V3 model. The intersections between actual categories and predicted categories can be observed. For example, there are 100 mountain samples correctly predicted as mountains, 5 incorrectly predicted as plains, 3 incorrectly predicted as plants, and 2 incorrectly predicted as animals. The prediction results for other categories are also listed in the table. Overall, the Inception-V3 model also demonstrates good classification performance, with the majority of samples correctly classified. However, there are some misclassifications, particularly in the plant and animal categories.

Landscape element classification and fine-grained PLIR

The improved model undergoes multiple experimental validations, mainly comparing the performance of different methods in landscape element recognition and plant leaf selection tasks. Table 7 presents the experimental results of different model architectures in landscape element classification and fine-grained PLIR tasks. It suggests that in the landscape element classification task, the traditional FCN-8s model achieves an accuracy of 85.2%. The improved FCN model, after incorporating multi-scale feature fusion and attention mechanisms, reaches an accuracy of 89.7%, showing a 4.5% improvement. This indicates that through multi-scale feature fusion and attention mechanisms, the model is able to capture more detailed features of different landscape elements, thus enhancing classification accuracy. In the fine-grained PLIR task, the improved FCN model also shows a significant increase in accuracy, from 81.7 to 86.5%, a 4.8% improvement over the FCN-8s. Notably, in fine-grained recognition tasks, the model captures subtle differences in plant leaves better, improving recognition accuracy. Furthermore, by combining object detection (Faster R-CNN) and FCN image segmentation, the accuracy improves further. The FCN + Faster R-CNN combined framework achieves accuracies of 90.4% and 88.7% in landscape element classification and fine-grained PLIR, respectively, which is approximately 5.2% and 7% higher than the traditional FCN model. This demonstrates that the combination of object detection and image segmentation effectively reduces the impact of background noise, making the model more accurate in recognizing plant leaves.

Case design

The proposed improved model (which combines multi-scale feature fusion, attention mechanisms, and object detection) not only achieves significant experimental performance improvements in theory but also plays a crucial role in practical landscape design. To better illustrate the practical application of these techniques, the model’s effectiveness is demonstrated in the following specific landscape design cases.

Case 1: Landscape design for urban park.

In the project of landscape design for an urban park, the designer needs to quickly and accurately identify the plant elements in different areas for optimal vegetation layout. Using the improved FCN model to process satellite images of the park, the model successfully performs fine-grained segmentation of plant leaves and accurately classifies them based on plant species.

Case 2: Landscape restoration in the scenic area.

In a scenic area landscape restoration project, designers need to restore or replace damaged plant areas to ensure the integrity of the original ecological landscape. Traditional methods often rely on manual surveys and classification, but due to the variety of plant species and their similar morphology, misjudgments can easily occur. Applying the combined technique of object detection and FCN image segmentation in this project can automatically identify the distribution of various plants in the scenic area, accurately extract plant regions, and provide fine-grained restoration suggestions. Particularly in the identification of rare plants, the model is further optimized using a region-weighted loss function, ensuring that the protection and restoration of rare plants are prioritized.

The multi-scale feature fusion, attention mechanism, and the combined framework of object detection and image segmentation proposed can effectively address issues in landscape design like plant species identification difficulties, background noise interference, and fuzzy element boundaries. Through the fine recognition and segmentation of different landscape elements, designers can improve the accuracy of plant selection and quickly identify key elements in complex landscape images, providing strong data support for landscape design. Additionally, the strategy combining TL and region-weighted loss functions effectively tackles the class imbalance problem in landscape design, especially showing its advantage in the identification of rare plants. The application of these technologies can promote the intelligentization of landscape design, and further enhance the efficiency of designers and the scientific nature of design decisions.

Discussion

This paper proposes a DL framework that combines multi-scale feature fusion, attention mechanisms, and object detection for landscape element recognition and plant selection. Experimental results show that the improved model achieves significant performance improvements in multiple tasks. However, despite these advancements, the model still faces some limitations in certain complex scenarios and requires further optimization and refinement. First, although this paper utilizes the FCN model and enhances its performance in landscape element recognition through the introduction of attention mechanisms and multi-scale feature fusion, the model’s performance remains suboptimal in some complex scenes. For instance, when processing scenes with substantial background noise or multiple similar plant species, the model may still experience misclassification or missed detection. This aligns with the findings of Zhang et al. (2023), who noted that while the FCN model performed well in image segmentation tasks, it still required further optimization to meet the demands of different application scenarios42. Future research could explore additional optimization strategies, such as the introduction of an adaptive threshold adjustment mechanism or the integration of more contextual information to reduce misclassification rates. Besides, although this paper combines object detection (Faster R-CNN) and FCN image segmentation, the model’s computational efficiency remains a concern, especially in application scenarios that require high processing speed. As Stefenon et al. (2022) pointed out, Inception-V3 reduced computational burdens through network structure optimization while maintaining high accuracy43. Similarly, the computational complexity of the FCN and object detection models used here is relatively high, particularly when processing large-scale image datasets. To address this issue, future research could consider incorporating model compression techniques or adopting more efficient network structures, such as MobileNet or EfficientNet, to improve computational efficiency and reduce resource consumption in practical applications. Moreover, as Meena et al. (2023) highlighted TL could accelerate the training process by leveraging knowledge from pre-trained models and enhance the model’s generalization capability44. Although TL has been applied, there remain shortcomings in recognizing specific plant species or rare landscape elements during the transfer process. To further improve model accuracy, future work could involve more detailed domain-adaptive adjustments during TL and incorporate fine-tuning strategies at various levels to enhance the model’s performance in specific domains.

In recent years, a growing body of research has explored the application of DL techniques in landscape design and plant recognition. For example, Chen et al. (2023) proposed an environmental landscape design system based on computer vision and DL, utilizing a conventional CNN architecture to classify environmental images45. However, their method lacked a multi-scale feature fusion strategy, which limited its recognition accuracy in complex landscape backgrounds. Liu et al. (2022) employed a machine learning model to generate urban greening plant configuration schemes. Although the concept of automated generation was introduced, their modeling approach remained rule-based and was ineffective in handling diverse plant morphologies and background interference46. Cong et al. (2025) developed an improved DL model for plant image recognition and landscape design using remote sensing images. The key innovation lay in the integration of remote sensing data; nevertheless, their method proved inadequate in extracting fine-grained features of plant leaves47. Zhang et al. (2023) introduced a Lightweight Deep Learning Model to enhance inference speed. Despite its practicality, the model compromised recognition accuracy in semantic segmentation tasks48. Yu et al. (2022) constructed a garden design system based on Multimodal Intelligent Computing and DNN, with a primary focus on system architecture while offering limited analysis of model performance and complex image processing49. In addition, Zhang and Kim (2023) investigated plant configuration in rooftop gardens for sustainable urban development by incorporating computer vision–based interactive technologies. However, their work primarily emphasized interactive design, with limited optimization of plant recognition techniques50. Compared with the above studies, this paper introduces several key innovations and advancements: (1) a multi-scale feature fusion module and dual channel/spatial attention mechanism are incorporated into the FCN architecture, significantly enhancing the model’s segmentation capability for complex landscape images with diverse elements; (2) object detection is performed using Faster R-CNN to improve accuracy and reduce background interference, thereby enabling more precise recognition of landscape features and plant leaves; (3) in the plant selection task, a domain-adaptive transfer learning strategy and a region-weighted loss function are proposed to enhance the recognition of rare plant categories and address class imbalance issues; and (4) the model is validated across multiple real-world datasets, demonstrating broad applicability and strong generalization capability. Therefore, in comparison to existing research, the proposed model not only integrates multiple advanced mechanisms within its architecture but also exhibits superior experimental performance, offering a more practical solution for achieving high-precision and robust intelligent landscape design and plant selection.

The application prospects of this paper are broad, particularly in fields such as sustainable urban planning and biodiversity conservation. In urban greening and landscape design, precise identification of different landscape elements and plant species improves the quality of landscape design and provides essential data support for ecological conservation and plant biodiversity monitoring. Furthermore, with the widespread adoption of intelligent technologies, digital landscape design is poised to become a key direction for future urban development. The framework proposed here offers a practical solution for such applications. However, challenges and areas for improvement remain. Future research could explore the following aspects. First, the model’s computational efficiency should be further optimized to enhance its performance in large-scale scenarios; second, the model’s ability to recognize complex backgrounds and rare plants needs to be enhanced, thereby reducing misclassification and missed detection. Through these optimizations, this paper holds the potential for wider application and can provide stronger technical support for intelligent landscape design and ecological conservation.

Conclusion

Through an in-depth study of DL applications in landscape design and plant selection, this paper proposes a DL framework that integrates multi-scale feature fusion, attention mechanisms, and object detection. Experimental results demonstrate that the framework performs exceptionally well in landscape element recognition and plant leaf selection tasks, significantly improving accuracy compared to traditional methods. Notably, after introducing domain-adaptive TL strategies and a region-weighted loss function, the model has shown greater robustness in addressing class imbalance issues and identifying rare plant species. This paper not only advances the intelligent process of digital landscape design but also provides technical support for plant biodiversity conservation and sustainable urban planning.