Abstract

This study presents a systematic experimental evaluation of the thermal and rheological properties of Behran oil-based nanofluids formulated with three inexpensive and easily synthesized nitride nanoparticles: boron nitride (BN), carbon nitride (CN), and boron carbon nitride (BCN). Each nanoparticle was surface-functionalized to improve dispersion stability and dispersed at concentrations of 0.1–0.5 wt.%. Thermal conductivity, convective heat transfer coefficient, specific heat capacity, and viscosity were measured at 25 °C, 35 °C, and 50 °C. Structural and morphological characteristics of the nanostructures were confirmed through FTIR, XRD, SEM, TEM, and DLS analyses. The nanofluid containing BN showed the highest thermal conductivity enhancement (14.92% at 0.3 wt.% and 50 °C), while CN led to the greatest increase in specific heat capacity (414% at 25 °C). BCN exhibited moderate enhancements across both properties. All nanofluids exhibited minimal viscosity increases (< 1% at 50 °C), suggesting their potential suitability for high-performance thermal systems. These results highlight the potential of functionalized nitride nanostructures as effective additives for improving the heat transfer performance of industrial lubricants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanofluids, first introduced by Choi et al. in 19951, are engineered suspensions of particles in base fluids, offering tunable thermal and flow properties. Over the past two decades, nanofluids have demonstrated significant promise for improving heat transfer and energy efficiency in diverse industrial applications. Despite significant progress, identifying optimal nanoparticle compositions and dispersion strategies remains a major challenge, especially for oil-based systems operating under elevated temperatures. Researchers have developed nanoparticles dispersed in base fluids to enhance thermal transport and flow behavior in various applications, including electronics cooling, solar systems, and industrial lubrication2,3,4. Their enhanced thermal conductivity, heat transfer capability, and tunable viscosity make them attractive for high-efficiency thermal systems.

Suspending nanoparticles in base fluids enhances internal energy transport and imparts distinctive thermophysical properties, differing significantly from those of conventional fluids and including notable mechanical, chemical, electrical, thermal, and optical characteristics5,6. In response to the ongoing energy crisis, nanofluids have attracted extensive research attention for enhancing the performance and thermal efficiency of industrial systems, as frequently reported in the literature7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15.

Among the wide array of nanoparticles explored for nanofluid applications, materials such as metal oxides, nitrides, and carbides have demonstrated significant potential because of their superior thermal and mechanical characteristics16,17,18,19,20,21,22. Numerous nanoparticles—including oxides (e.g., Al2O3, TiO2), metals (e.g., Cu, Ag), nitrides (e.g., BN, AlN), and carbides (e.g., SiC)—have been investigated for nanofluid synthesis due to their superior thermophysical properties16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38. Recently, nitrides have gained attention for their thermal stability and unique bonding structures, making them ideal candidates for high-temperature and industrial oil-based systems24,29,30. However, nitride-based nanostructures such as CN and BCN remain underexplored, particularly in oil-based systems.

Oil-based nanofluids have gained particular attention. This is due to their applicability in high-temperature and industrial systems. Examples of such systems include transformer oils, turbine oils, and engine oils39,40,41,42. Improving the thermal and rheological properties of these industrial oils can significantly enhance energy efficiency and system performance.

Despite their potential, utilizing nanofluids presents major challenges, such as nanoparticle instability, aggregation, and poor dispersion, which hinder their performance and long-term usability46,47. Various methods, including functionalization and surfactant addition, have been employed to address these issues.

The increase in thermal conductivity with higher solid concentrations in mixtures can be attributed to several underlying mechanisms, primarily related to the structural and compositional characteristics of the materials involved. These mechanisms include enhanced phonon transport, and the influence of particle interactions within the matrix43,44. Ali et al. proved the thermal conductivity of suspensions increases with higher solid concentrations45. Similar trends were observed in functionalized MWCNT-silicone oil nanofluid44. For TiO2, ZnO, and CuO nanofluids show increases of up to 17.62%, 21.55%, and 24.32% respectively at a particle concentration of 1.5 wt.%45.

Asadi et al. experimentally studied Mg(OH)2/MWCNT-oil hybrid nanolubricants over a range of temperatures and solid concentrations46. Their experiments demonstrated a maximum thermal conductivity enhancement of 50%.

Sarvari et al. explored the effects of TiO2 and MWCNTs nanoparticles on the heat transfer properties of turbine meter oil47. The results revealed that the addition of nanoparticles improved both the heat transfer coefficient and the pressure drop.

In another study, Puspitasari et al. examined various thermophysical properties of lubricants enriched with nanoparticles such as fullerene, graphene, single-walled carbon nanotubes, double-walled carbon nanotubes, and multi-walled carbon nanotubes, using engine oil 10W-30 as the base fluid48. Their findings showed an increase in thermal conductivity compared to the base oil, with MWCNT-based lubricants exhibiting the highest viscosity.

Samylingam et al. recently conducted an experimental study on the thermal conductivity of palm oil/MXene nanofluid without using surfactants, across a temperature range of 25–70 °C49. Their findings revealed that the thermal conductivity of the nanofluid significantly improved with the addition of nanoplates and with increasing temperature. The highest enhancement, a 68.5% increase compared to the base oil, was observed at 25 °C with a nanoparticle concentration of 0.2 wt.%.

Mukhtar et al. experimentally examined the stability and thermal conductivity of kapok seed oil/MWCNT nanofluids in the presence of surfactants across different temperatures and concentrations50. Their results showed that the thermal conductivity increased from 0.35 to 1.485 K.m/W at a concentration of 0.8 wt.% MWCNTs and further intensified at higher temperatures.

Soltani et al. investigated the thermal conductivity of motor oil/MWCNT-3-WO nanofluids experimentally within a temperature range of 25–60 °C51. Their study indicated that the influence of solid particles was more pronounced than that of temperature. The highest thermal conductivity enhancement, an 85.19% increase compared to the base oil, was observed at a concentration of 0.6 vol.% and a temperature of 60 °C.

Viscosity is a fundamental rheological property that plays a critical role in predicting fluid behavior. It is essential for anticipating fluid flow patterns in various processes52. Nanofluids, which contain solid nanoparticles, exhibit higher viscosity than conventional working fluids. Therefore, viscosity measurement is crucial for applications such as thermal system design and pumping power estimation53,54,55. Many researchers have investigated the rheological properties of synthesized nanofluids in their studies.

Parvar et al. investigated the effects of ZnO nanoparticles on the thermal conductivity and dynamic viscosity of transformer oil56. Their results indicated that the nanofluid exhibited higher thermal conductivity compared to pure transformer oil at 25 °C. Moreover, as the temperature increased, the dynamic viscosity of both pure transformer oil and nano-oil decreased.

Ranjbarzadeh et al. carried out an experimental investigation using nanotechnology to improve the efficiency of engine oil57. Their findings revealed that the nanolubricant exhibited higher thermal conductivity than the base fluid. Moreover, the dynamic viscosity increased with variations in volume fraction, achieving a maximum enhancement of 36% compared to the base oil.

While extensive studies have explored oil-based nanofluids with metal oxides and carbides, comparative data on nitride-based nanostructures (BN, CN, and BCN) in hydrocarbon fluids are scarce. This study addresses a critical research gap by systematically evaluating BN, CN, and BCN in Behran oil, a common industrial lubricant. BN offers high thermal conductivity and chemical stability, CN provides high heat capacity, and BCN combines these traits for tunable properties. All are cost-effective and scalable, yet their performance in oil-based systems under consistent conditions remains underexplored. By synthesizing and functionalizing these nanoparticles under parallel protocols and testing them in a single experimental framework, this study provides novel insights into their thermal conductivity.

Most prior works have focused either on single nanoparticle types or on water-based systems, with little emphasis on how nanoparticle composition and functionalization affect both thermal and rheological behavior in oil matrices. Despite advancements in nanofluid research, significant gaps remain in the comparative evaluation of nitride-based nanostructures in oil-based systems. Most prior studies focus on single nanoparticle types (e.g., Al2O3, TiO2, or BN) or water-based fluids, with limited attention to oil-based matrices like Behran oil, which are critical for high-temperature applications such as transformer oils and engine lubrication. Additionally, inconsistent functionalization methods across studies hinder fair comparisons of nanoparticle performance. This study addresses these gaps by (i) synthesizing and characterizing three distinct nitride nanoparticles (BN, CN, and BCN), (ii) applying standardized functionalization protocols to ensure comparable dispersion stability, and (iii) evaluating their impact on thermal conductivity, specific heat capacity, viscosity, and convective performance in a single experimental framework. This approach provides novel insights into the structure–property relationships of nitride nanofluids, advancing their potential for scalable, high-efficiency thermal systems. This study experimentally evaluated the heat transfer, viscosity, and heat capacity of Behran thermal oil with three nitride nanoparticles added at 0.1–0.5 wt.% and tested at 25, 35, and 50 °C.

Experiments

Materials

All chemicals in this study were of analytical reagent grade, ensuring high purity for precise analysis without additional purification. The base fluid was engine oil (Behran-Pishtaz, Behran Oil Company, Iran). Other chemicals, sourced from Merck, are listed in Table 1.

Methods

Synthesis of boron nitride, carbon nitride and boron carbon nitride

The procedure for synthesizing boron nitride is illustrated in Fig. 1.

First, 9.28 g of melamine and 6.3 g of boric acid were dissolved in 500 mL of deionized water. The solution was then stirred at 85 °C for 12 h to evaporate the water. The mixture was placed in a tube furnace and heated at 1050 °C for 3.5 h under a nitrogen atmosphere. The resulting powder is commonly known as h-BNNFs58. The temperature of 1050 °C and 3.5-h were selected based on literature reports indicating optimal crystallinity for h-BN structures synthesized via melamine-boric acid pathways. Lower temperatures were found to yield amorphous or poorly crystalline products.

The synthesis of CN is depicted in Fig. 2. Initially, 15 g of dicyandiamide were placed in a covered crucible and heated to 550 °C for 4 h at a rate of 5°C·min⁻1. The resulting yellow g-C3N4 agglomerates were then milled using an agate mortar. Subsequently, 1 g of the bulk g-C3N4 powder was transferred to a crucible and heated to 500 °C for 2.5 h at the same rate of 5°C·min⁻1. Finally, a primrose-yellow powder was obtained59.

The synthesis of boron carbon nitride (BCN) follows a defined procedure (Fig. 3). First, urea and boric acid were mixed in a specific weight ratio and heated to 65 °C to form white boron nitride (BN) crystals. In the next step, these BN crystals are combined with glucose in a 1:1 weight ratio and ground finely using a mortar. Finally, the mixture is heated to 900 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere for one hour, leading to the formation of hexagonal boron carbon nitride nanosheets (h-BCNNS)60.

The yield of synthesized nanoparticles was calculated as the weight of the final product divided by the total precursor input, resulting in approximate yields of 73% for BN, 78% for CN, and 70% for BCN.

Functionalizing h-BNNFs, g-C3N4 Nanosheets and h-BCNNS

Among the modification methods, the use of silane coupling agents is an effective approach to introduce functional groups onto the surfaces of nanoparticles61,62. Due to the inherent instability of nanoparticles in oil, we also modified the surfaces of the nanoparticles to enhance their stability.

The silane agents were selected based on compatibility with each nanoparticle’s surface chemistry. KH550 (primary amine group) was used for BCN due to its mixed-phase nature, facilitating bonding with both B–N and C = N functionalities. KH560 (epoxy functionality) was more effective for CN due to its layered structure and nitrogen-rich surface.

For the functionalization of boron nitride (Fig. 4), 0.15 g of h-BNNFs was dispersed in 150 mL of Tris buffer solution (0.01 mol·L⁻1) and ultrasonicated for 20 min. Subsequently, 0.06 g of dopamine hydrochloride (DA) was added to the solution, followed by another 20 min of ultrasonication. Next, 0.2 mL of APTES was introduced into the solution, and the pH was adjusted to 8.5 by adding 0.1 M hydrochloric acid solution while stirring vigorously for 5 h. The resultant solution was then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm and washed with ethanol and deionized water. Finally, the reaction product was dried in an oven at 60 °C for 24 h to yield the functionalized h-BNNFs (FhBNNFs)58.

To functionalize carbon nitride (Fig. 5), 0.15 g of g-C3N4 nanosheets were dispersed in 0.15 L of Tris buffer solution (0.01 mol·L⁻1) and sonicated for 20 min. Subsequently, 0.06 g of dopamine hydrochloride was added to the solution, followed by an additional 20 min of ultrasonication. Next, 0.2 mL of KH560 was introduced into the mixture, and the pH was adjusted to 8.5 using a 10 wt.% sodium hydroxide solution, with vigorous stirring at 650 rpm for 5 h. Finally, the prepared hybrids were centrifuged at 8000 rpm and rinsed three times with deionized water. The obtained products were then dried using freeze-drying59.

To functionalize boron carbon nitride, as shown in Fig. 6, 0.484 g of Tris was dissolved in 300 mL of deionized water, and the pH was adjusted to 8.5 using 0.1 M hydrochloric acid. Then, 0.8 g of dopamine hydrochloride and 0.2 mL of KH550 were added under continuous stirring. Subsequently, 2 g of synthesized h-BCNNS was rapidly introduced into the mixture and stirred for 5 min. The solution was then ultrasonicated for 3 h and maintained at 60 °C for 24 h. The mixture was ultrasonicated for 3 h and maintained at 60 °C for 24 h. The resulting powder was then filtered, washed with deionized water until a colorless solution was obtained, and dried in an oven at 60 °C for 60 h to produce Fh-BCNNS60.

Instrumentation and analytical techniques

Various analytical techniques were employed to characterize the structural, morphological, stability, rheological, and thermal properties of the synthesized nanofluids. All property measurements were conducted in accordance with relevant ASTM or ISO standards, where applicable. The viscosity was measured according to ASTM D7042. Thermal conductivity was assessed using the ASTM D5334 THW method and specific heat capacity was determined based on ISO 11,357–4. The details of the instruments and measurement methods are provided below.

The chemical structure and functional groups of the synthesized BN, CN, and BCN nanoparticles were analyzed using a Bruker Tensor 27 FTIR spectrometer (Bruker, Germany). The spectra were recorded in the 4000–400 cm−1 range using the attenuated total reflectance (ATR) method with a spectral resolution of 4 cm⁻1.

The crystallographic structure of the nanoparticles was investigated using an X’Pert PRO MPD X-ray diffractometer (PANalytical, Netherlands) equipped with a Cu-Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5406 Å). Diffraction patterns were recorded over a 2θ range of 10°–80° with a step size of 0.02° and a scan speed of 2°/min. The crystal size was calculated using the Scherrer equation, D = Kλ/(β cos θ), where K = 0.9, λ = 1.5406 Å, and β is the FWHM of the peak.

The surface morphology and microstructure of the nanoparticles were characterized using a TESCAN MIRA3 field-emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, Czech Republic) operated at an accelerating voltage of 10–15 kV. High-resolution imaging was performed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with a JEOL JEM-2100 microscope (JEOL, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV.

The hydrodynamic diameter and particle size distribution in the nanofluids were measured using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Panalytical, UK) through dynamic light scattering (DLS) at a scattering angle of 173°. Measurements were performed at 25°C. Stability was classified based on the zeta potential threshold of ± 30 mV, indicating moderate stability for CN, high stability for BN, and low stability for BCN.

Viscosity measurements were conducted using a Brookfield DV3T rheometer (AMETEK Brookfield, USA) with a cone-and-plate geometry, covering nanoparticle concentrations of 0.1–0.4 wt.% at temperatures of 25–50 °C, with shear rates varying between 10 and 100 s⁻1. The viscosity values were recorded at different nanoparticle concentrations (0.1–0.4 wt.%). The upper limit of 0.4 wt.% was due to the rheometer’s sensitivity constraints, as higher concentrations led to inconsistent shear stress readings and potential shear-thinning behavior, which affected measurement accuracy.

Thermal conductivity measurements, performed using a Decagon KD2 Pro analyzer (METER Group, USA), via the transient hot wire method, extended to 0.5 wt.% concentrations, as this method remained reliable at higher particle loadings due to its insensitivity to particle interactions under the tested conditions.

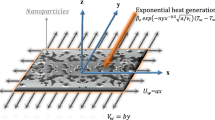

The convective heat transfer coefficient (h) was determined through forced convection experiments conducted in a custom-built test loop with a horizontal stainless-steel tube.

The stainless-steel test section had an inner diameter of 8 mm and a heated length of 300 mm, with a cartridge heater inserted axially and insulation applied externally to minimize heat loss. The nanofluid was circulated using a peristaltic pump (Masterflex L/S, USA) at controlled flow rates corresponding to Reynolds numbers ranging from 200 to 2000. The Reynolds number was calculated using the expression Re = ρuD/μ, with viscosity (μ) corrected for each temperature using experimental data obtained for the nanofluids at 50°C. The heat flux was applied using a cartridge heater, and temperatures were recorded using K-type thermocouples connected to a data acquisition system (NI DAQ, National Instruments, USA). The convective heat transfer coefficient was calculated using h = q/(A·ΔT), where q is the applied heat flux, A is the surface area of the heated section, and ΔT is the fluid temperature difference. Nusselt number correlations were also used to validate laminar flow assumptions (200 < Re < 2000).

The specific heat capacity (Cp) of the nanofluids was determined using a Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC 8000, PerkinElmer, USA). The measurements were performed over a temperature range of 25–200°C, with heating rates of 10°C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere. For DSC tests conducted in this study, the sample mass was maintained at 10 mg to ensure consistent thermal analysis. The samples were placed in aluminum chamber, which provided optimal thermal conductivity and minimized sample interaction with the chamber material. These conditions were carefully chosen to enhance the reproducibility of the results and facilitate accurate thermal characterization of the materials.

Results

Characterization

A comprehensive characterization of the synthesized BN, CN, BCN nanoparticles was performed using FTIR, XRD, SEM, TEM, and DLS analyses to confirm their structural integrity, morphology, and dispersion properties.

Figure 7 presents the results of the FTIR analysis, which provided detailed insights into the vibrational properties and chemical bonding of BN, CN, and BCN.

Figure 8 shows the results of XRD analysis. XRD analysis revealed distinctive structural characteristics for BN, CN, and BCN. The BN pattern exhibited a prominent peak between 26° and 28° 2θ, corresponding to the (002) plane of h-BN, indicative of its layered structure. The sharpness of this peak suggests a high degree of crystallinity, while broader subsidiary peaks indicate potential defects or structural disorder.

The calculated crystallite sizes of BN, CN, and BCN nanoparticles are summarized in Table 2 using the Scherrer equation.

Morphological analysis

The SEM images shown in Fig. 9 provide insights into the structural characteristics of BN, CN, and BCN at various magnifications.

Figure 10 shows the results of TEM analysis, highlighting the morphology of BN, CN, and BCN nanoparticles at various magnifications.

Particle size distribution and stability

The particle size distributions obtained from DLS measurements are shown in Fig. 11.

The zeta potential analysis results were reported in Table 3. An absolute zeta potential value greater than ± 30 mV generally indicates a stable nanosuspension, while values exceeding ± 45 mV correspond to excellent stability63,64.

Viscosity measurements

Various factors, like temperature, nanoparticle concentration, pH value, dispersion stability, and particle shape, influence the viscosity of nanofluids65,66. Since nanofluids typically exhibit higher viscosity than base fluids due to nanoparticle interactions, understanding these variations is essential for optimizing heat transfer applications.

In this study, the viscosity of nanofluids containing BN, CN, and BCN nanoparticles was measured as a function of temperature (25–50°C) and nanoparticle concentration (0.1–0.4 wt.%). The obtained viscosity data reported in Table 4.

The standard deviation for viscosity measurements was < 4.5% indicating suitable repeatability.

Thermal conductivity measurement

The enhancement of nanofluid thermal conductivity depends on multiple factors that influence its properties. These factors include stability67, temperature68,69, particle size70, viscosity71, particle shape72, and Brownian diffusion73. Additionally, the results indicate that increasing nanoparticle concentration and temperature leads to a further increase in thermal conductivity74.

Some studies report that increasing temperature enhances thermal conductivity75,76. The results indicate that nanofluids exhibit higher thermal conductivity than the base fluid across all tested temperatures and concentrations, as summarized in Table 5.

These results are presented in Fig. 12.

The convective heat transfer coefficient for various nanofluids was also determined within the Reynolds number range of 200–2000 and is presented in Fig. 13.

The standard deviation for viscosity measurements was < 7.5% indicating suitable repeatability.

Heat Capacity (CP) by Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

The results of heat capacity tests for different nanoparticles have shown varying outcomes61,77. In this study, the Cp analysis graph at different temperatures for the base oil and its nanofluids, formulated by incorporating BN, CN, and BCN nanoparticles, is presented in Fig. 14.

c.

Figure 15 illustrates the percentage increase in Cp for various nanofluids compared to the base oil.

The increase at room temperature for each nanofluid is reported in Table 6.

Discussion

The FTIR spectrum of BN (Fig. 7) exhibited a sharp absorption band at ~ 800–900 cm⁻1, corresponding to the in-plane B-N-B stretching vibration characteristic of hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN). The absence of strong absorptions above 1400 cm⁻1 suggests minimal contributions from out-of-plane bending modes, consistent with the symmetric sp2-bonded structure of h-BN. No significant peaks were observed beyond 2000 cm⁻1, confirming the lack of functional group contamination (e.g., -OH or -NH2).

For CN, the spectrum displayed prominent absorption bands in the 1200–1600 cm⁻1 range, assigned to C = N and C-N stretching vibrations in graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N₄), with a peak near 1560 cm⁻1 attributed to aromatic C = N stretching. A broad absorption around 2100 cm⁻1, if present, may indicate minor nitrile (C≡N) or alkyne (C≡C) impurities, while the 3000–3500 cm⁻1 region likely arises from residual N–H stretching modes.

The BCN spectrum combined features of both BN and CN, with the B-N stretching peak (~ 800 cm⁻1) confirming BN retention and the 1200–1600 cm⁻1 absorptions indicating C-N/C = N incorporation. The broad high-wavenumber absorption (2000–3500 cm⁻1) suggests complex bonding interactions, though overlapping contributions from B-C, N–H, and C≡N cannot be definitively resolved by FTIR alone.

The XRD pattern in Fig. 8 of CN showed a broad peak centred around 27° to 28°, attributed to the (002) plane of graphitic CN (g-C3N4, JCPDS #87–1526). This peak’s narrower profile compared to BN implies fewer defects and a more regular stacking of layers, suggesting a well-ordered, graphite-like layered structure with nitrogen atoms integrated into the graphitic planes.

Boron carbon nitride exhibited characteristics between those of BN and CN. Its dominant peak around 27° was associated with the h-BN (JCPDS #34–0421) phase but modified by carbon incorporation. Broadening and slight shifts in this peak, relative to pure BN, suggest structural distortions and reduced crystallinity due to the incorporation of carbon and nitrogen atoms within the BN framework.

In summary, XRD patterns show a trend in crystallinity, increasing from BN (pattern a) to CN (pattern b) and then decreasing in BCN (pattern c). Carbon incorporation into the BN lattice led to peak shifts and sharpening, indicating enhanced crystallinity. However, the broader peaks observed in BN and BCN reflect a more disordered structure than that of CN.

Purity of synthesized material were evaluated using XRD phase analysis, which confirmed the absence of secondary crystalline phases (e.g., no peaks corresponding to oxides or other impurities), and FTIR spectra, which showed no significant contamination peaks (e.g., -OH or -NH2 beyond expected functional groups). These results indicate high phase purity for all samples, supporting their suitability for nanofluid applications.

The SEM images demonstrated in Fig. 9. At a scale of 200 nm (a-1), BN exhibits elongated, rod-like structures with well-defined edges and a relatively uniform size distribution, suggesting a crystalline nanorod formation. The smoothness of these structures indicates high BN purity. When viewed at 500 nm (a-2), these rod-like structures are more prominent, showing clear aggregations likely resulting from synthesis conditions that favor clustering. At the 1 μm scale (a-3), a dense network of intertwined rods is observed, indicating significant self-assembly or aggregation, forming a network of BN nanorods.

Carbon nitride SEM images reveal a markedly different morphology. At 200 nm (b-1), a rough, layered structure with irregular, sheet-like formations is visible, characteristic of a graphitic CN structure formed from nitrogen-containing carbon precursors. At 500 nm (b-2), these sheets show extensive aggregation, forming a dense, nearly compact mass, suggesting a more amorphous, less crystalline structure than BN. At 1 μm (b-3), this aggregation becomes even more pronounced, with larger, tightly clustered formations and indistinct boundaries, indicating high levels of aggregation.

At 200 nm (c-1), BCN displays particles with rough, irregular surfaces, likely consisting of boron, carbon, and nitrogen elements. These particles are smaller than the BN structures and have pronounced surface roughness, indicative of carbon-based components. In image (c-2) at 500 nm, a heterogeneous mixture of larger and smaller particles is visible, suggesting the coexistence of BN and CN phases. At 1 μm (c-3), dense particle clusters form a porous network with large spacing, reflecting the incorporation of boron, carbon, and nitrogen elements into a composite material with low crystallinity.

In summary, BN displays a highly crystalline nanorod structure, while CN appears more amorphous with densely packed sheet-like formations. BCN combines these features, showing non-uniform particle distribution and a porous morphology, indicating successful incorporation of both boron and carbon-based components. SEM analysis of these three materials reveals unique structural characteristics that reflect the distinct synthesis processes and material properties of each.

In Fig. 10, the nano-scale TEM image of BN reveals large, elongated, and likely multi-layered structures with distinct edges. The pronounced contrast between the layers indicates the presence of stacked BN sheets, with darker areas corresponding to thicker regions of the material. These well-defined edges suggest a relatively high degree of crystallinity. Based on the scale, these BN structures measure several tens of nanometres in size. Smaller-scale observations show a degree of agglomeration, suggesting the formation of larger particles with stacked layers, alongside a mass of smaller BN particles.

At the micro-scale, TEM images of CN reveal particles with uneven edges and a sponge-like texture, characteristic of a porous structure. Internal pores are evident, which aligns with the g-C3N4 structural framework typical of CN. The darker regions indicate denser areas, likely due to the stacking of CN layers. In nano-scale images, small, irregular CN particles display a highly amorphous texture, with darker areas highlighting denser particles. At finer scales, the porous structure and sheet-like morphology of CN become more distinct, reaffirming the layered g-C3N4 arrangement. At a scale of 100 nm, spherical CN particles cluster together, likely formed during synthesis, with a uniformity that suggests controlled synthesis conditions.

The micro-scale TEM image of BCN shows a dense particle with a smooth surface and darker contrast, indicating significant thickness and a high degree of crystallinity. At 500 nm, spherical clusters of BCN particles display smooth surfaces, indicative of an ordered internal structure. The uniformity of these particles suggests a controlled synthesis process that favored spherical formation. At a scale of 300 nm, smaller, irregular agglomerates with uneven, textured surfaces appear, lacking distinct spherical shapes. This suggests lower crystallinity, possibly due to the incorporation of both boron and carbon, which can influence the material’s crystallinity.

In summary, BN exhibits a tubular and layered morphology, with a crystalline order apparent in some regions, while clustered agglomerates suggest amorphous areas. TEM analysis of CN highlights its primarily amorphous, sponge-like structure with a porous framework. The TEM images of BCN suggest dense, agglomerated particles with both spherical and irregular shapes, implying that the incorporation of boron and carbon may result in diverse morphologies, including both crystalline and amorphous regions.

The particle size distribution plot in Fig. 11 for CN and BCN show similar overall trends. BN exhibits a narrow distribution peak centred around 650–750 nm, reflecting the uniform rod-like structures seen in the SEM and TEM images. This narrow distribution indicates good dispersion and consistent particle sizes across the sample.

For CN, the particle size distribution is broader and shorter than that of BN, with a peak centred between 1000–1150 nm. This wider distribution aligns with SEM observations of agglomerated, sheet-like structures, suggesting a higher tendency for CN particles to form aggregates within the nanosuspension.

BCN has the broadest and lowest peak in its particle size distribution, centred around 1150–1200 nm. This wide distribution is consistent with SEM images, indicating varying degrees of agglomeration among particles.

Several methods have been employed to evaluate the stability of nanofluids, including sedimentation photography78, UV–Vis spectrophotometry79, zeta potential analysis79, and spectrophotometry80 among others. While commonly used, this method is less precise for nanofluids with dark colors. In such cases, the most reliable method is Zeta potential analysis81.

According to the data reported in Table 3, BN exhibited the highest stability with a zeta potential of + 66.4 mV, indicating strong electrostatic repulsion and minimal aggregation. This result aligns well with the uniform particle structure observed in SEM and TEM images, as the strong positive charge aids in preventing agglomeration through electrostatic repulsion.

CN exhibited moderate stability with a zeta potential of −31.2 mV, as it is close to the stability threshold of ± 30 mV. The negative charge correlates with the nitrogen-rich functional groups observed in the FTIR spectra.

BCN exhibited the lowest stability (+ 13.2 mV), likely due to increased structural disorder and weaker electrostatic repulsion, making it more prone to clustering. This lower positive value is consistent with the heterogeneous morphology and increased agglomeration noted in the SEM images. The intermediate zeta potential between BN and CN reflects the composite nature of BCN, in agreement with the findings from XRD and FTIR analyses.

The viscosity results in Table 4, show that the addition of nanoparticles increased viscosity compared to the base oil, with variations depending on nanoparticle type and concentration. Consequently, the highest viscosity was observed at the maximum nanoparticle concentration (0.3 wt.%).

Table 7 presents a comprehensive summaries of the thermal and rheological performance of Behran oil-based nanofluids containing functionalized BN, CN, and BCN nanoparticles. The analysis of the thermal and rheological performance of Behran oil-based nanofluids reveals distinct characteristics among the functionalized BN, CN, and BCN nanoparticles. The FTIR spectra confirm the successful functionalization of the nanoparticles, while the zeta potential measurements indicate varying levels of stability, with BN demonstrating superior stability due to its high positive zeta potential. The DLS results suggest that BN nanoparticles are smaller in size compared to CN and BCN, which may influence their dispersion and thermal conductivity. Furthermore, the PDI values equal one indicate that the nanoparticles have uniform size distribution, which could enhance its performance in specific applications.

All nanofluids demonstrated near-linear shear stress–shear rate relationships, indicating Newtonian behavior across the tested shear rate range (10–100 s−1). No shear-thinning or thickening was observed, even at higher concentrations. The results indicated that viscosity decreases with increasing temperature; however, the nanofluids still have higher viscosity than the base fluid.

The observed maximum thermal conductivity in Table 5 enhancement for BN at 0.3 wt.% suggests the onset of a thermal percolation threshold. Beyond this concentration, particle agglomeration likely reduces effective conductivity by limiting phonon pathways. This behavior is consistent with percolation theory in particulate composites and highlights the importance of optimizing concentration.

Figure 12 illustrates the absolute thermal conductivity of the base oil and nanofluids as a function of nanoparticle concentration (0.1–0.5 wt.%). BN nanofluids exhibit the highest absolute thermal conductivity (0.1494 W/m·K at 0.3 wt.%), followed by CN (0.1409 W/m·K at 0.3 wt.%) and BCN (0.1367 W/m·K at 0.4 wt.%), compared to the base oil’s 0.1300 W/m·K. These trends indicate promising thermal performance of BN, suggesting its potential for application in high-efficiency thermal systems.

The results indicated that the highest thermal conductivity was observed at a concentration of 0.3 wt.% for BN and CN, while for BCN, the optimal concentration was 0.4 wt.%. At higher concentrations, nanofluids are more susceptible to nanoparticle clustering, which increases the effective surface contact area and reduces thermal resistance.

Another important parameter for evaluating the heat transfer performance of fluids is the heat transfer coefficient, which was examined as a function of Reynolds number and nanoparticle concentration. The Reynolds number range 200–2000 confirms laminar flow, with the upper bound approaching transition. However, no turbulence was observed, and the laminar flow assumption remains valid for our analysis. Studies on forced convection using nanofluids are limited and exhibit divergent results. The convective heat transfer behavior of a medium depends on its thermophysical properties, including thermal conductivity, density, viscosity, specific heat capacity, and thermal expansion coefficient82.

Our test results demonstrated that an increase in nanoparticle concentration and Reynolds number enhances the convective heat transfer coefficient.

According resulted data in Fig. 13, BN exhibited the highest heat transfer coefficient, attributed to its unique morphology and surface structure. Research indicates that rod-shaped nanoparticles generally achieve higher heat transfer coefficients compared to spherical nanoparticles83,84,85.

Specific heat capacity (Cp) enhancement is another crucial parameter for nanofluid performance evaluation. The highest increase in Cp was observed for CN nanofluids, with a remarkable 309% improvement at 50 °C, significantly outperforming MXene-based soybean oil nanofluids, which exhibited only a 24.49% increase86. This superior heat capacity enhancement in CN nanofluids can be attributed to their unique structural characteristics, including a high surface area and functionalized surfaces that enhance interaction with the base fluid.

Overall, the results suggest that BN, CN, and BCN nanofluids could provide a balance between thermal conductivity enhancement, limited viscosity increase, and improved heat capacity. Compared to previous studies, the findings highlight the effectiveness of these nanofluids for industrial applications where both heat transfer efficiency and fluid stability are critical.

Moreover, while the experimental results highlight the significant thermal and rheological improvements achieved through functionalized BN, CN, and BCN nanostructures, practical implementation must consider scale-related challenges. While laboratory-scale synthesis and dispersion were effective, scaling up nanofluid preparation may pose challenges including nanoparticle agglomeration, batch consistency, and long-term dispersion stability. Addressing these issues will be critical for industrial adoption. Future work should therefore include pilot-scale trials and stability assessments over extended operational periods.

The Cp analysis graph in Fig. 14 indicates significant changes in the specific heat capacity of the base oil upon the addition of nanoparticles. The pure base oil shows the lowest Cp value. A remarkable increase in specific heat capacity is observed with the addition of BN, CN, and BCN nanoparticles, with CN exhibiting the highest increase. The Cp graph demonstrates a nearly linear upward trend across the temperature range of 25 °C to 200°C. The variations in Cp for the base oil, BCN, and BN nanofluids remain almost consistent and linear across the entire range. The rod-like shape of BN (confirmed by SEM and TEM) contributes to its superior thermal conductivity through aligned phonon pathways and increased surface area. In contrast, CN’s layered morphology enhances Cp by promoting fluid structuring at interfaces, as also evidenced by FTIR and zeta potential results. Particle agglomeration, particularly observed in CN and BCN samples via SEM and DLS analyses, significantly impacts thermal performance. Agglomeration disrupts continuous phonon pathways by forming clusters that reduce the effective surface area available for heat transfer, thereby increasing thermal resistance and limiting thermal conductivity enhancements. For CN, despite its remarkable specific heat capacity increase (414% at 25 °C), agglomeration hinders uniform heat distribution, resulting in a lower-than-expected thermal conductivity enhancement (5.6% at 0.3 wt.%). Similarly, BCN’s broader particle size distribution (1150 ± 80 nm) and lower zeta potential (+ 13.2 mV) indicate increased clustering, contributing to its moderate thermal conductivity (5.12% at 0.4 wt.%). These findings align with prior studies, which report that nanoparticle clustering reduces thermal bridging efficiency and phonon transport in nanofluids2,3. In contrast, BN’s rod-like morphology and high zeta potential (+ 66.4 mV) minimize agglomeration, supporting its superior thermal conductivity (14.92% at 0.3 wt.%) through aligned phonon pathways.

The crystallite sizes of the nanoparticles, calculated using the Scherrer equation based on XRD data, were 9.76 nm for BCN, 27.00 nm for CN, and 15.37 nm for BN. These sizes provide insight into the structural order and its influence on thermal and rheological performance. CN’s larger crystallite size (27.00 nm) corresponds to its sharper (002) peak in XRD patterns, indicating a more ordered, graphite-like layered structure with fewer defects, as evidenced by SEM images showing sheet-like formations. This enhanced crystallinity likely contributes to CN’s superior specific heat capacity (Cp) enhancement (414% at 25 °C), as larger crystallites facilitate efficient phonon confinement and fluid structuring at interfaces. In contrast, BCN’s smaller crystallite size (9.76 nm) aligns with its broader XRD peaks, reflecting greater structural disorder due to the incorporation of carbon into the BN lattice. This disorder may explain BCN’s lower zeta potential (+ 13.2 mV) and broader particle size distribution (1150 ± 80 nm), which contribute to its moderate thermal conductivity (5.15% at 0.4 wt.%) and Cp (324% at 25 °C) enhancements. BN, with an intermediate crystallite size (15.37 nm), exhibits a balance between crystallinity and disorder, as seen in its rod-like morphology and high zeta potential (+ 66.4 mV). This structural characteristic supports BN’s superior thermal conductivity (14.92% at 0.3 wt.%), driven by aligned phonon pathways in its nanorods.

For the base oil at 25 °C, the Cp value is approximately 0.42 J/g·K, which increases to about 0.63 J/g·K at 50°C. This gradual increase reflects the natural behavior of the base oil, where its ability to absorb thermal energy improves with temperature. The relatively mild slope of the graph (approximately 0.0084 per degree Celsius) indicates the favorable thermal stability of the base oil.

The specific heat capacity analysis results reveal that the addition of nanoparticles to the base oil significantly alters the thermal behavior of the fluid. At room temperature (25 °C), the base oil’s specific heat capacity is about 0.42 J/g.K.

A comparison of the graphs in Fig. 15 reveals that the addition of nanoparticles to the base fluid increases the Cp values across all temperature ranges. Moreover, the variations for BN and BCN remain nearly similar throughout the range. Based on this, it can be concluded that the Cp graph for BN is consistently higher than that of BCN. A notable observation in the curves of Fig. 15 is that, with increasing temperature, the difference in specific heat capacity between the nanofluids and the base oil decreases. This behavior could be attributed to increased molecular mobility at higher temperatures and the reduced influence of nanoparticles on the fluid’s structure.

The exceptional Cp enhancement observed in CN nanofluids (up to 414% at 25 °C) exceeds predictions from the rule of mixtures, which typically assumes linear contributions from the base fluid and nanoparticles. This remarkable increase can be attributed to CN’s layered morphology, as observed in SEM and TEM images, which maximizes the interfacial contact area with the Behran oil, promoting phonon confinement and fluid structuring at the nanoparticle-fluid interface. The nitrogen-rich surface of CN, confirmed by FTIR peaks at 1200–1600 cm⁻1 (C = N and C-N stretching), enhances molecular interactions with the oil, facilitating microstructural ordering that significantly boosts thermal energy storage capacity. These effects align with prior studies on carbon-based nanostructures, where high surface area and functional groups contribute to enhanced specific heat capacity4,5. In contrast, BN and BCN, with rod-like and mixed morphologies, respectively, exhibit lower Cp enhancements (309% and 324% at 25 °C), likely due to less pronounced interfacial effects and higher agglomeration tendencies, as supported by DLS and zeta potential results.”

The thermal capacity behavior of these nanofluids can be further interpreted based on their structure. As noted, the thermal capacity behaviors of BN and BCN are similar. This similarity can be attributed to their comparable crystallinity, as observed in XRD analyses. The XRD results indicate that BN and BCN exhibit low crystallinity. In contrast, CN shows a prominent peak, indicative of higher crystallinity. Although the lower crystallinity structure facilitates heat transfer, the percentage increase in Cp for BN and BCN is significantly lower compared to CN.

Overall, the results demonstrate that CN nanoparticles have the greatest impact on enhancing the specific heat capacity of the base oil, owing to their regular crystalline structure, high colloidal stability, and uniform morphology. These findings can be applied to the design of nanofluids with superior thermal performance.

FTIR analysis also confirms the presence of various functional groups on the surface of CN, which may contribute to heat transfer. The FTIR results reveal that CN has a layered structure with C-N and C = N bonds. This layered structure, combined with diverse functional groups, creates more surface contact with the base oil, leading to a greater increase in Cp. The layered structure of CN, observed in TEM images, expands the interfacial contact area with the base oil, thereby reducing interfacial thermal resistance. This reduction in interfacial thermal resistance is the primary factor driving the higher Cp increase in CN-containing nanofluids.

In summary, the increasing trend in Cp follows the order CN > > BN > BCN, which correlates with the structural, morphological, and surface characteristics of the nanoparticles. The lower zeta potential of BCN (+ 13.2 mV) compared to BN (+ 66.4 mV) and CN (−31.2 mV) indicates a greater tendency for aggregation, which may reduce the nanoparticle’s effectiveness in enhancing Cp.

Comparison with previous studies

To assess the significance of our findings, we compared the thermal, rheological, and heat capacity properties of Behran oil-based nanofluids containing BN, CN, and BCN nanoparticles with those reported in previous studies on oil-based nanofluids. Table 8 provides a summary of the key results from this study alongside relevant literature.

In terms of thermal conductivity enhancement, our study achieved a maximum increase of 14.92% for BN at 0.3 wt.% and 50 °C, which surpasses the 2.08% improvement reported for h-BN in SAE 5W-30 lubricant at 40 °C and 0.15% volume fraction87. Unlike reference87, which focuses solely on non-functionalized h-BN and measures thermal conductivity at a single temperature, our study employs functionalized BN, CN, and BCN nanoparticles in Behran oil, testing a broader concentration range (0.1–0.5 wt.%) and temperature range (25–50°C). Additionally, our work includes specific heat capacity (up to 414% enhancement for CN) and viscosity measurements, providing a more comprehensive evaluation of nanofluid performance. The use of standardized functionalization protocols further ensures consistent dispersion stability, enabling a robust comparison of the three nitrides’ thermal and rheological properties, which is a novel contribution to the field. However, compared to MXene nanoparticles in soybean oil, which exhibited a remarkable enhancement of 60.82% at 0.125 wt.% and 55°C86, the results for BN, CN, and BCN were lower. This difference can be attributed to the superior thermal conductivity of MXene-based nanofluids and the inherently different base fluids used.

Regarding viscosity changes, our results indicated minimal increases across all nanofluids, with CN showing the lowest viscosity alteration (0.04%), followed by BCN (0.48%) and BN (0.83%). This suggests that our synthesized nanofluids maintain favorable flow characteristics, a key advantage over many other oil-based nanofluids. For instance, MXene-based soybean oil nanofluids exhibited a viscosity increase of 13.28%86, which can significantly impact pumping power requirements and fluid handling.

Conclusions

This study systematically evaluated the thermal and rheological performance of Behran oil-based nanofluids containing BN, CN, and BCN nanoparticles. The functionalization of nanoparticles significantly improved their dispersion stability, as confirmed by zeta potential measurements. Thermal conductivity and convective heat transfer coefficient analysis indicated that BN nanoparticles provided the most substantial improvement in heat transfer performance, while CN nanoparticles exhibited the highest enhancement in specific heat capacity. BCN nanofluids displayed a balanced combination of both properties. Importantly, all nanofluids exhibited less than 1% viscosity increase at 50 °C operational temperatures, a distinct advantage over many high-performance nanofluids that compromise fluidity. A comparative analysis with previous studies suggests that BN, CN, and BCN nanofluids can offer competitive thermal performance in thermal systems. The results offer valuable insights for optimizing oil-based nanofluids to achieve enhanced heat transfer and lubrication performance. These nanofluids may be promising for applications such as transformer oils, heat exchangers, and engine cooling systems. Given their relatively low synthesis cost and minimal loading requirements, BN, CN, and BCN offer economically viable alternatives to rare or metal-based additives. Their thermal performance and benign chemical composition also make them attractive from an environmental perspective. Future studies should include long-term thermal cycling, dispersion stability under real flow conditions, and assessments to evaluate wear resistance in dynamic systems.

Data availability

Data availability: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Choi, S. U., & Eastman, J. A. (1995). Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles.

Khan, S. A., Hayat, T. & Alsaedi, A. KHA model comprising MoS 4 and CoFe 2 O 3 in engine oil invoking non-similar Darcy-Forchheimer flow with entropy and Cattaneo-Christov heat flux. Nanoscale Adv. 5(22), 6135–6147 (2023).

Guo, Y., Liu, H., Gong, L. & Shen, S. The physical mechanism of heat transfer enhancement for Al2O3-water nanofluid forced flow in a microchannel with two-phase lattice Boltzmann method. Multidiscip. Model. Mater. Struct. 20(5), 891–911 (2024).

Mohite, D. D., Goyal, A., Singh, A. S., Ansari, M., Patil, K., Yadav, P. D., Patil, M., & Londhe, P. (2024). Improvement of thermal performance through nanofluids in industrial applications: A review on technical aspects. Materials Today: Proc..

Walshe, J. et al. Nanofluid development using silver nanoparticles and organic-luminescent molecules for solar-thermal and hybrid photovoltaic-thermal applications. Nanomaterials 10(6), 1201 (2020).

Bakthavatchalam, B. et al. Optimization of thermophysical and rheological properties of mxene ionanofluids for hybrid solar photovoltaic/thermal systems. Nanomaterials 11(2), 320 (2021).

Behera, U. S., Sangwai, J. S. & Byun, H.-S. A comprehensive review on the recent advances in applications of nanofluids for effective utilization of renewable energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 207, 114901 (2025).

Samylingam, L. et al. Green engineering with nanofluids: Elevating energy efficiency and sustainability. J. Adv. Res. Micro Nano Eng. 16(1), 19–34 (2024).

Jaiswal, P., Kumar, Y., Das, L., Mishra, V., Pagar, R., Panda, D., & Biswas, K. G. (2023). Nanofluids guided energy-efficient solar water heaters: Recent advancements and challenges ahead. Materials Today Communications, 107059.

Sundar, L. S. Synthesis and characterization of hybrid nanofluids and their usage in different heat exchangers for an improved heat transfer rates: A critical review. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 44, 101468 (2023).

Bretado-de los Rios, M. S., Rivera-Solorio, C. I., & Nigam, K. An overview of sustainability of heat exchangers and solar thermal applications with nanofluids: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 142 110855. 2021

Eshgarf, H., Kalbasi, R., Maleki, A., Shadloo, M. S. & Karimipour, A. A review on the properties, preparation, models and stability of hybrid nanofluids to optimize energy consumption. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 144, 1959–1983 (2021).

Elsaid, K., Olabi, A., Wilberforce, T., Abdelkareem, M. A. & Sayed, E. T. Environmental impacts of nanofluids: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 763, 144202 (2021).

Mohammed, A. A., Dawood, H., & Onyeaka, H. N. (2023). A review paper on properties and applications of nanofluids. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science,

Chkhartishvili, L., & Dekanosidze, S. (2020). Obtaining of boron carbide based titanium-containing nanocomposites (Mini-review). Nano Studies 7–18.

Tuok, L. P. et al. Experimental investigation of copper oxide nanofluids for enhanced oil recovery in the presence of cationic surfactant using a microfluidic model. Chem. Eng. J. 488, 151011 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Obtaining an accurate prediction model for viscosity of a new nano-lubricant containing multi-walled carbon nanotube-titanium dioxide nanoparticles with oil SAE50. Tribol. Int. 191, 109185 (2024).

Borda, F. L. G., de Oliveira, S. J. R., Lazaro, L. M. S. M. & Leiróz, A. J. K. Experimental investigation of the tribological behavior of lubricants with additive containing copper nanoparticles. Tribol. Int. 117, 52–58 (2018).

Guo, J., Barber, G. C., Schall, D. J., Zou, Q. & Jacob, S. B. Tribological properties of ZnO and WS2 nanofluids using different surfactants. Wear 382, 8–14 (2017).

Wang, X., Liu, H., Zhao, Q., Wang, X. & Lou, W. Viscosity variations and tribological performances of oleylamine-modified Fe3O4 nanoparticles as mineral oil additives. Lubricants 11(3), 149 (2023).

Tamrat, S., Ancha, V. R., Gopal, R., Nallamothu, R. B. & Seifu, Y. Emission and performance analysis of diesel engine running with CeO2 nanoparticle additive blended into castor oil biodiesel as a substitute fuel. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 7634 (2024).

Ali, A. et al. Thermal and rheological behavior of hybrid nanofluids containing diamond and boron nitride in thermal oil for cooling applications. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 49(6), 7811–7828 (2024).

Alhamd, S. J., Manteghian, M., Dehaghani, A. H. S. & Rashid, F. L. An experimental investigation and flow-system simulation about the influencing of silica–magnesium oxide nano-mixture on enhancing the rheological properties of Iraqi crude oil. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 6148 (2024).

Duvvarapua, A., Reddy, P. S., Suresh, D., & Kumar, R. J. Experimental analysis of variations in the properties of transformer oil by adding aluminium nitride nanopowder. Advances in Thermodynamics and Heat Transfer 62. 2020

Zhang, L., Zhu, Z., Zhao, D., Gao, X. & Wang, B. Tribological performance of ZrO2 nanoparticles as friction and wear reduction additives in aviation lubricant. Mater. Res. Express 11(9), 095006 (2024).

Jamshidi, A., Hajilary, N. & Hajilari, M. Insight into the investigation of applying MXene nanoparticles to enhance the properties of transformer oil. Nano-Struct. & Nano-Objects 37, 101078 (2024).

Razavi, R., Amiri, M., & Khajouei, G. SiO2-based nanofluids. In Nanofluids (pp. 129–162). Elsevier. 2024

Mousavi, S. B., Heris, S. Z. & Estellé, P. Viscosity, tribological and physicochemical features of ZnO and MoS2 diesel oil-based nanofluids: An experimental study. Fuel 293, 120481 (2021).

Raghav, R. & Mulik, R. S. Effects of temperature and concentration of nanoparticles on rheological behavior of hexagonal boron nitride/coconut oil nanofluid. Colloids Surf., A 694, 134142 (2024).

Vallejo, J. P., del Río, J. M. L., Fernandez, J. & Lugo, L. Tribological performance of silicon nitride and carbon black Ionanofluids based on 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium methanesulfonate. J. Mol. Liq. 319, 114335 (2020).

Gokul, V., Swapna, M. N. S. & Sankararaman, S. I. Eco-conscious nanofluids: Exploring heat transfer performance with graphitic carbon nitride nanoparticles. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung A 78(12), 1163–1171 (2023).

Agonafir, M. B., Aadnøy, B. & Saasen, A. Effect of titanium nitride (tin) nanoparticles on the lubricity and viscosity of water-based drilling fluid. Ann. Trans. Nordic Rheol. Soc. 32, 37–52 (2024).

Kandasamy, G., Paramasivam, S., Varudharajan, G. & Dhairiyasamy, R. Optimization of silver nanoparticle-enhanced nanofluids for improved thermal management in solar thermal collectors. Matéria (Rio de Janeiro) 29(3), e20240363 (2024).

Angayarkanni, A., & Philip, J. (2022). Synthesis of nanoparticles and nanofluids.

Hafeez, A., Liu, D., Khalid, A. & Du, M. Melting heat transfer features in a Bo¨ dewadt flow of hybrid nanofluid (Cu− Al2O3/water) by a stretching stationary disk. Case Stud.Thermal Eng. 59, 104554 (2024).

Rasool, G., Shafiq, A., Wang, X., Chamkha, A. J. & Wakif, A. Numerical treatment of MHD Al2O3–Cu/engine oil-based nanofluid flow in a Darcy-Forchheimer medium: Application of radiative heat and mass transfer laws. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 38(09), 2450129 (2024).

Algehyne, E. A., Alamrani, F. M., Saeed, A. & Bognár, G. A numerical exploration of the comparative analysis on water and kerosene oil-based Cu–CuO/hybrid nanofluid flows over a convectively heated surface. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 2540 (2024).

Kumar, M. D., Dharmaiah, G., Chamorro, V. F. & Palencia, J. L. D. Investigating the thermal efficiency of Al2O3–Cu–CuO–cobalt with engine oil tetra-hybrid nanofluid with motile gyrotactic microorganisms under suction and injection scenarios: Response surface optimization. Nano 19(08), 2450041 (2024).

Ndlovu, B. A. (2021). Effects of surface partial discharges on the dielectric strength of ester oil-impregnated pressboard insulation in power transformers faculty of engineering and the built environment, University of …].

Siddique, A., Tanzeela, Aslam, W., & Siddique, S. Upgradation of highly efficient and profitable eco-friendly nanofluid-based vegetable oil prepared by green synthesis method for the insulation and cooling of transformer. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 1–10. 2024

Sudhakar, T., Muniraj, R., Jarin, T. & Sumathi, S. Nanofluid-enhanced vegetable oil blends: A sustainable approach to breakthroughs in dielectric liquid insulation for electrical systems. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 15(6), 9011–9034 (2025).

Esmaeili-Faraj, S., Bijhanmanesh, M., Alibak, A., Pirhoushyaran, T. & Vaferi, B. Experimental measurement and modeling analysis of the heat transfer in graphene oxide/turbine oil non-newtonian nanofluids. Nanomater. Nanotechnol. 2024(1), 5572387 (2024).

Wanatasanappan, V. V., Rezman, M. & Abdullah, M. Z. Thermophysical properties of vegetable oil-based hybrid nanofluids containing Al2O3-TiO2 nanoparticles as insulation oil for power transformers. Nanomaterials 12(20), 3621 (2022).

Premalatha, M., Preetha, N., Padmavathi, S. & Jeevaraj, A. Enhanced thermal conductivity of carboxyl (–COOH) functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT)-silicone oil based nanofluids. Sens. Lett. 18(1), 52–54 (2020).

Ali, B., Qayoum, A., Saleem, S., & Mir, F. Q. (2023). Experimental investigation of nanofluids for heat pipes used in solar photovoltaic panels. Journal of Thermal Engineering 9(2).

Asadi, A., Asadi, M., Rezaniakolaei, A., Rosendahl, L. A. & Wongwises, S. An experimental and theoretical investigation on heat transfer capability of Mg (OH) 2/MWCNT-engine oil hybrid nano-lubricant adopted as a coolant and lubricant fluid. Appl. Therm. Eng. 129, 577–586 (2018).

Sarvari, A. A., Heris, S. Z., Mohammadpourfard, M., Mousavi, S. B. & Estellé, P. Numerical investigation of TiO2 and MWCNTs turbine meter oil nanofluids: Flow and hydrodynamic properties. Fuel 320, 123943 (2022).

Puspitasari, P., Permanasari, A. A., Abdullah, M. I. H. C., Habibi, I. A. & Pramono, D. D. A comparative study on stability, thermal conductivity, and rheological properties of nanolubricant using carbon-based additive. J. Tribologi. 42, 33–48 (2024).

Samylingam, L. et al. Thermal and energy performance improvement of hybrid PV/T system by using olein palm oil with MXene as a new class of heat transfer fluid. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 218, 110754 (2020).

Mukhtar, A. et al. Experimental and comparative theoretical study of thermal conductivity of MWCNTs-kapok seed oil-based nanofluid. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer 110, 104402 (2020).

Soltani, F., Toghraie, D. & Karimipour, A. Experimental measurements of thermal conductivity of engine oil-based hybrid and mono nanofluids with tungsten oxide (WO3) and MWCNTs inclusions. Powder Technol. 371, 37–44 (2020).

Bhattad, A. Review on viscosity measurement: devices, methods and models. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 148(14), 6527–6543 (2023).

Monalisha, B., Sasmita, B., & Jayashree, N. A critical analysis of nanofluid usage in shell and tube heat transfer systems. 2024

Graish, M. S. et al. Prediction of the viscosity of iron-CuO/water-ethylene glycol non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluids using different machine learning algorithms. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 11, 101180 (2025).

Shijina, S. S., Akbar, S. & Sajith, V. Graphene functionalized nano-encapsulated composite phase change material based nanofluid for battery cooling: An experimental investigation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 259, 124893 (2025).

Parvar, M., Saedodin, S. & Rostamian, S. H. Experimental study on the thermal conductivity and viscosity of transformer oil-based nanofluid containing ZnO nanoparticles. J. Heat Mass Transf. Res. 7(1), 77–84 (2020).

Ranjbarzadeh, R. & Chaabane, R. Experimental study of thermal properties and dynamic viscosity of graphene oxide/oil nano-lubricant. Energies 14(10), 2886 (2021).

Mirzaee, M. et al. Amino-silane co-functionalized h-BN nanofibers with anti-corrosive function for epoxy coating. React. Funct. Polym. 174, 105244 (2022).

Xia, Y. et al. Co-modification of polydopamine and KH560 on g-C3N4 nanosheets for enhancing the corrosion protection property of waterborne epoxy coating. React. Funct. Polym. 146, 104405 (2020).

Mirzaee, M. et al. Investigating the effect of PDA/KH550 dual functionalized h-BCN nanosheets and hybrided with ZnO on corrosion and fouling resistance of epoxy coating: Experimental and DFT studies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10(6), 108746 (2022).

Ganesh, E. Investigation of Doubling heat capacity of storage fluids through nanomaterials. Indian Journal of Advanced Chemistry, 1 (3),1, 4. 2022

Yari, H. & Rostami, M. Investigation of surface treatment with various silane coupling agents on photocatalytic activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles. J. Color Sci. Technol. 12(2), 93–105 (2018).

Aberoumand, S. & Jafarimoghaddam, A. Experimental study on synthesis, stability, thermal conductivity and viscosity of Cu–engine oil nanofluid. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 71, 315–322 (2017).

Wei, B., Zou, C. & Li, X. Experimental investigation on stability and thermal conductivity of diathermic oil based TiO2 nanofluids. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 104, 537–543 (2017).

Patra, A., Nayak, M. & Misra, A. Viscosity of nanofluids-A Review. Int. J. Thermofluid Sci. Technol 7(2), 070202 (2020).

Mohaideen, M. M., Sai, P., & Lahari, M. Assessment of Temperature and Nanoparticle Concentration on the Viscosity of Glycerine-water Based SiO2 Nanofluids. 2022

Chakraborty, S. & Panigrahi, P. K. Stability of nanofluid: A review. Appl. Therm. Eng. 174, 115259 (2020).

Yaw, C. T. et al. An approach for the optimization of thermal conductivity and viscosity of hybrid (graphene nanoplatelets, GNPs: cellulose nanocrystal, CNC) nanofluids using response surface methodology (RSM). Nanomaterials 13(10), 1596 (2023).

Mei, X., Sha, X., Jing, D. & Ma, L. Thermal conductivity and rheology of graphene oxide nanofluids and a modified predication model. Appl. Sci. 12(7), 3567 (2022).

Ambreen, T. & Kim, M.-H. Influence of particle size on the effective thermal conductivity of nanofluids: A critical review. Appl. Energy 264, 114684 (2020).

Murshed, S. S. & Estellé, P. A state of the art review on viscosity of nanofluids. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 76, 1134–1152 (2017).

Liu, C., Chen, M., Zhou, D., Wu, D. & Yu, W. Effect of filler shape on the thermal conductivity of thermal functional composites. J. Nanomater. 2017(1), 6375135 (2017).

Cui, X., Wang, J. & Xia, G. Enhanced thermal conductivity of nanofluids by introducing Janus particles. Nanoscale 14(1), 99–107 (2022).

Moradi, A., Zareh, M., Afrand, M. & Khayat, M. Effects of temperature and volume concentration on thermal conductivity of TiO2-MWCNTs (70–30)/EG-water hybrid nano-fluid. Powder Technol. 362, 578–585 (2020).

Apmann, K., Fulmer, R., Soto, A. & Vafaei, S. Thermal conductivity and viscosity: review and optimization of effects of nanoparticles. Materials 14(5), 1291 (2021).

Hamid, K., Azmi, W., Nabil, M., & Mamat, R. Improved thermal conductivity of TiO2–SiO2 hybrid nanofluid in ethylene glycol and water mixture. IOP Conference series: materials science and engineering 2017

Anand, T., & Mallick, S. S. (2021). Specific heat of nanofluids—An experimental investigation. fluid mechanics and fluid power: Proc. of FMFP 2019,

Oemar, B. et al. Experimental investigation on thermophysical and stability properties of TiO2/virgin coconut oil nanofluid. Sci. Technol. Indonesia 8(2), 178–183 (2023).

Kumar, P. M., Palanisamy, K., & Vijayan, V. (2020). Stability analysis of heat transfer hybrid/water nanofluids. Materials today: Proc. 21 708-712.

Sofiah, A., Samykano, M., Shahabuddin, S., Kadirgama, K. & Pandey, A. An experimental study on characterization and properties of eco-friendly nanolubricant containing polyaniline (PANI) nanotubes blended in RBD palm olein oil. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 145, 2967–2981 (2021).

Asadi, A. et al. Heat transfer efficiency of Al2O3-MWCNT/thermal oil hybrid nanofluid as a cooling fluid in thermal and energy management applications: An experimental and theoretical investigation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 117, 474–486 (2018).

Mohammed, H., Al-Aswadi, A., Shuaib, N. & Saidur, R. Convective heat transfer and fluid flow study over a step using nanofluids: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 15(6), 2921–2939 (2011).

Onishi, T. & Yamamoto, T. Numerical analysis of effects of aspect ratio of rod-like nanoparticles on thermal and flow behavior of nanofluids in backward-facing step flows. Nihon Reoroji Gakkaishi 50(4), 323–332 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Heat transfer enhancement of nanofluids with non-spherical nanoparticles: A review. Appl. Sci. 12(9), 4767 (2022).

Hosseini, S. M. S., Sadeghipour, A. M., & Shafiey Dehaj, M. Synthesis and application of ZnO rod-shaped nanoparticles for the optimal operation of the plate heat exchanger. Physics of Fluids 34(9) 2022

Rubbi, F. et al. Performance optimization of a hybrid PV/T solar system using Soybean oil/MXene nanofluids as A new class of heat transfer fluids. Sol. Energy 208, 124–138 (2020).

Asmoro, R. K., Puspitasari, P., Permanasari, A. A. & Abdullah, M. Identification of thermophysical and rheological properties of SAE 5w–30 with addition of hexagonal boron nitride. Transmisi 19(1), 41–48 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Institute of Petroleum Industry (RIPI). The authors would like to thank RIPI for providing financial support, experimental facilities, and technical guidance during the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Fatemeh Abdolahi: Manuscript Writing, Data Analysis, Provide Figures/Illustrations, Study Design Amir Heydarinasab, Alimorad rashidi: Correspond and supervisor, Revision and Final Approval Mehdi Ardjmand, Mehdi Moayed mohseni: conducted the data analysis and statistical evaluations, participated in the study design and oversaw the experimental work. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdolahi, F., Heydarinasab, A., rashidi, A. et al. Thermal and rheological performance of behran oil-based nanofluids with functionalized BN, CN, and BCN nanoparticles. Sci Rep 15, 31662 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16956-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16956-9