Abstract

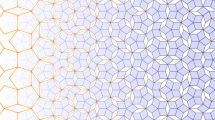

4-fold pentille tessellation is in two of the known eight classes of periodic tessellations with convex pentagons with side-to-side property and it is also known as Cairo pattern. In these tessellations, the tiles occur in four different orientations and each pentagon tile has five side-neighbors (neighbor pentagons such that a full side is shared) and seven corner-neighbors (pentagons such that there is at least one point shared on the boundary, i.e., at least a corner). Digital, i.e., path-based distances were recently computed on this grid for side-neighbor criteria in Kovács et. al.: Distance on the Cairo pattern. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 145: 141-146 (2021),1, where the tiles are addressed by coordinate six-tuples. In this paper our aim is twofold, on the one hand, we give a much less complex description of the grid based on coordinate pairs, on the other hand, we compute also the distance based on corner-neighbors. Our result applies to two of the classes of the known 8 periodic side-to-side pentagonal tessellations based on a sole convex pentagon tile.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There are various tessellations and tilings playing import roles in various fields of science and arts. Many of them occur in various places in nature, e.g., connected to crystallography2; and also various tilings are used in arts from the ancient time. In each of the 3 regular tilings, one regular polygon tessellates the plane in edge-to-edge manner. In semi-regular tilings, more than one regular polygons are used as tiles with the same side length. There are three regular and eight semi-regular tilings. Some of these tilings play various important roles in image processing and graphics, as, for instance, they could have better symmetrical or topological properties than the usual square grid has3,4. Already, in5, a semi-regular grid was proposed as image grid. From a tiling (and generally from a planar grid) its dual can be obtained by changing the roles of grid points and regions. The dual of the regular tilings are also regular, more precisely, the square grid is self-dual and the triangular and hexagonal tilings are dual of each other. On the other hand, the dual of the semi-regular grids are not regular or semi-regular, but they are built up by a single type of tile that is non-regular and it is used in more than one orientation. While the semi-regular tilings belong to the class of Archimedean tilings (together with the regular tilings), their dual tilings are called Catalan tilings in6. There are 11 Archimedean tilings and 8 Catalan tilings. No pentagon occurs in any regular and semi-regular tilings. In7 it is claimed that there are exactly 15 classes of convex pentagonal monotiles that are able to tile the whole plane. From these 15 known pentagonal monotiling types, eight of them are capable to do edge-to-edge tiling8 (see Figure 1). The types of the tilings are specified with some geometric conditions on the tile, thus each type of tiling is, in fact, a family of tilings. Since, for us the families represented by tilings shown in Figure 1 b and c are important, we recall the conditions for the pentagons that can be used in those8: either two pairs of non-neighbor sides must have the pairwise the same length and the sum of some angles is specified (case b) or two-two pairwise neighbor sides must have the same lengths such that there is a right angle between them in both cases (case c); see also Figure 2 for more precise specification. Notice also that the conditions do not contradict to each other, i.e., there are pentagons that belong into both classes at the same time. Some of these pentagonal tilings also appear as dual tilings of some semi-regular tilings; for instance, types a–d include such some Catalan tilings. One of the most known among them is the Cairo pattern (named after the street paving in Cairo), that is also called 4-fold pentille6 and MacMahon’s net9. This tiling is special among the pentagonal tilings, as together with a tiling belonging to the family shown in Fig. 1 a, it has tiles with the minimum possible perimeter among all pentagonal tilings with the same area pentagons (having two right angles and three \(120^\circ\) angles,10,11). The Cairo pattern is, in fact, the dual of the semi-regular snub quadrille tiling5,12, and thus it shares many of the symmetric properties of this semi-regular grid. In this paper, continuing the ideas of5 and4, we propose this grid as an image grid, as it is built up by a single type of tile, i.e. a pentagonal “pixel.” This special case belongs to both type b and c tilings (as this pentagon meets the conditions for both types). Since the neighborhood structure and the orientations of the pentagons are similar, our study covers not only the specific Cairo pattern, but also all type b and type c edge-to-edge pentagonal tilings. (They are type 2 and type 4 pentagons for tilings, respectively, in e.g.8, where type 2 pentagons have variants whose tiling is not edge to edge by releasing the \(c = e\) condition.)

The Cairo pattern as the most known representant belonging to both classes b and c, as a Catalan tiling, contains pentagons with the condition that four of the sides have the same length, i.e., \(a=c=d=e\) with \(b=(\sqrt{3}-1)a\) and there are two non-neighbor right angles: \(\gamma = \varepsilon = 90^\circ\), and the other three angles are equal: \(\alpha = \beta = \delta = 120^\circ\). The tiling types shown in Figure 1 b and c give the same tiling using these specific pentagons and this tiling is widely known as the Cairo pattern.

The geometry of the pentagons that can be used in type b and c tilings, respectively. Conditions both on side length equalities and on angles are shown. In case b (left) two sides (a and d) must have equal length, to able to do edge-to-edge tiling, also other two sides (c and e) must have equal length, moreover the sum of some angles must match. In case c (right) the lengths of two pairs of neighbor sides must match and there must be two right angles, as they are specified.

In Figure 3, we show some well-known images resampled with various resolutions both on the square and on the 4-fold pentille tessellations. The pictures next to each other have approximately the same resolution. As one may observe, images on this new image grid look not worse than on the usual grid.

Example pictures on the Cairo pattern (top) and on the usual square pixel-grid (bottom) with various resolution. Pictures in the same column have approximately the same resolution the difference of the numbers of pixels in the two pictures in a column is around 20-30. (The original images are from: https://sipi.usc.edu/database/database.php).

The structure of the paper is as follows. In Section 2 we give our new coordinate system based on coordinate pairs addressing the pentagon tiles, we describe the neighborhood relations by these coordinates, moreover we also recall the earlier used coordinate system using six-tuples and we show how one can go from one of the coordinate systems to the other. Section 3 is about digital distances, on the one hand, we reformulate the result of1, the distance based on side-neighborhood with our new coordinate system; on the other hand, we also prove formula for the distance when in each step any corner-neighbors can be used. Finally, some concluding statements close the paper.

Mathematical description of the grid

As we are working on a two-dimensional grid, it is essential to have a compact system to address the tiles. The coordinate system used in1,16 is based on the facts that, on the one hand, these pentagonal grids can be seen as intersections of two hexagonal grids, and on the other hand, the hexagonal grid can be written nicely by zero-sum integer coordinate triplets. These six-tuples will be recalled in Sect. 2.2. They were used in the distance calculations in16. It is also noted there that the coordinate system can easily be reduced to use only four-tuples by removing one of the first three and one of the last three coordinates (those make the other two coordinates of the given triplets to zero-sum and therefore easily be reproduced). However, as we show in the next subsection, there is an efficient way to use coordinate pairs to address the tiles of our pentagonal tilings.

The new coordinate system

We consider the grid from another point of view, not as intersections of hexagonal grids, but as a grid that is equivalent to a rectangular grid with the following property. Let us consider the square grid. It is a bipartite grid in the terms of17, i.e., half of the square tiles of the infinite chessboard can be seen as black tiles, while the others are white. Now, let us modify the square grid by cutting its tiles as follows. Every second square tile (let us say, every black one) is divided to two identical rectangles by their horizontal symmetry axes, and every other square (every white tile) by their vertical symmetry axis.

Figure 4 shows a segment of this grid with the assigned coordinate pairs. The idea is as follows: one may assign the value (0, 0) to a corner of the original square grid. This defines also the axes, i.e. the lines where we use virtually 0 for the first and second coordinate, respectively. Actually, all the values that are divisible by 4 represent values assigned to a line of the original square grid, thus these values do not occur as assigned values to any of the tiles. There are actually, for types of tiles by their orientation and respective position. There are two types of horizontal tiles (those rectangles that have longer horizontal side than their vertical sign) and two vertical tiles, respectively. The horizontal tiles form pairs (filling an original square), and thus, we may refer to them as U and D (up and down) tiles. The vertical tiles are next to each other, and we refer to them by L and R, as the left and right tiles (of the given square). Notice that the rectangles of this representation can also be seen as degenerated pentagons belonging to the classes of pentagons specified by tiling types b and c. In the former case, \(\alpha = \gamma = \delta = \varepsilon = 90^\circ\), \(\beta = 180^\circ\), \(a = d\), \(e=c=\frac{a}{2}\) and \(b=0\). In the latter case, \(\alpha ' = 180^\circ\), \(\beta ' = \gamma ' = \delta ' = \varepsilon ' = 90^\circ\), \(a'=b'=c'=e'\) and \(d'=2a'\).

(a) Pavement of a pedestrian street, (b) the coordinate system for the rectangle tiles. Every original \(4\times 4\) square is divided either into U–D pair or into L–R pair. The integers on the axes skip multiples of 4; e.g. tiles with \(x\equiv 2\pmod 4\), \(y\equiv 3\pmod 4\) are U tiles, etc. (c) The coordinate axes and the unit, the coordinates assigned to the tiles are the Cartesian coordinates of their midpoints.

One can easily see that horizontal tiles have first even and odd second coordinate values, while vertical tiles have odd first and even second coordinate values. Moreover, the coordinate pairs have the properties shown in Table 1, furthermore, every integer pair satisfying the properties given in the table addresses a tile and this tile is of the given type. Further, each of the tiles have 5 side-neighbors (i.e., other tiles such that they have a common line in their boundary which may not be a full side/edge at one of the neighbor pairs). One of them is the twin brother of the tile: they are in the same square and sharing a full long edge; these neighbor tiles share one of their coordinates, while the difference is exactly 2 in the other coordinate. The other 4 neighbor tile share an edge that is a full edge of one of the tiles but only half of the edge of the other tile. Furthermore, there are two additional corner-neighbors that share only a corner with the original tile.

Table 2 summarizes the coordinate differences of the neighbor tiles. We note here that there are various types of naming conventions for the neighbors, sometimes the number of the given type of neighbors induces the name, as 4- and 8-neighbors in the square grid; now, by this analogy 5- and 7-neighborhood could be used in our pentagonal structures. Other possibility is to use the dimension of the shared part implying 0-neighbor for corner-neighbors and 1-neighbor for neighbors that share a full side. In this paper we use the terms of side- and corner-neighbors, respectively. Note also that the rectangular domino representation has the same number of neighbors as the Cairo pattern, but it is not an edge to edge grid itself.

One can see that the neighborhood relations are symmetric and irreflexive (none of the tiles is neighbor of itself), but not transitive. It is also obvious that the coordinate values keep the property for each type of tiles shown in Table 1.

Two tiles are not in any of the neighborhood relations if and only if either in both coordinates their difference is at least 4, or in one of the coordinates their difference is more than 4.

As the grid shown in Figure 4 is isometric (from the neighborhood point of view, see, e.g.18) with the 4-fold pentille tiling, the coordinate system can also adapted for it.

In Figure 5 we show also how a part of this pentagonal grid looks with the assigned coordinate values. It is easy to see that we have four differently oriented pentagons in the grid and they are exactly in the roles of type L, R, U and D tiles.

Let us define mathematically the neighbor relations on our grid based on our coordinate system.

Definition 1

Let a tile (x, y) be given, and let \((x',y')\) be a different tile.

-

The tile \((x',y')\) is called the twin brother of (x, y) if \(|x-x'| + |y-y'| = 2\).

-

The tile \((x',y')\) is called a side-neighbor of (x, y) if \(|x-x'| + |y-y'|\le 4\).

-

The tile \((x',y')\) is called a corner-neighbor of (x, y) if \(|x-x'|\le 4\), \(|y-y'|\le 4\), and \(|x-x'| + |y-y'| \le 6\).

It is easy to see that the following conditions hold.

Proposition 1

For any tile (x, y):

-

There is exactly one twin brother.

-

There are exactly 5 side-neighbors (counting the twin as well).

-

There are exactly 7 corner-neighbors (counting the 5 side-neighbors plus 2 extra that share only a corner).

Figure 6 presents the neighborhood for each type of tiles (in the order R, U, L, D of the types).

Proposition 2

From any tile (x, y), the 8 closest tiles of the same type have coordinates:

Proof

This is obvious by the coordinate system. \(\square\)

We note here that neither the coordinate system we have described above, nor the earlier one we recall in the next subsection are compact, in the sense that there are integer tuples that do not address any tiles. Actually, our aim was not to find a coordinate system that is the most compact for these grids, but to have a relatively simple system, where we can address the tiles with integer pairs (as our grid is a 2-dimensional grid) and the neighborhood relations can be efficiently and simply defined based on the coordinates. We believe that the system we have just described gives a good description for both further theoretical studies and also for practical applications. On the other hand, a compact scheme could be obtained by the coordinates of the square grid (we used to divide its tiles) plus an additional bit. The meaning of the bit (L/R versus U/D) depends on the parity of the coordinate sum of the square, i.e., if it belongs to the black or the white partition.

The old coordinate system with six-tuples

As we mentioned, another description of the Cairo pattern (and of the pentagonal tilings we work here) with coordinate six-tuples was already done (1,16), thus it is important to see the connections between that and the new coordinate system by means of conversions. In Figure 7 we show a part of the grid with that 6-tuple coordinate system. In that system, by crossing any of the sides of a pentagon exactly two of the coordinates were changed, one with +1, other with -1 and thus that system was very adequate to compute distances based on side-neighbors. The two colors of the grid highlight the two hexagonal grids such that their intersection results in the Cairo pattern. The first three coordinates are inherited from the symmetric (zero-sum) coordinate frame of the red grid, while the last three coordinates from the purple colored hexagonal grid. To make our result more relevant and to allow the reader also to compare it to the previously known results, in the next subsection we show how one can move between the two types of coordinate systems.

Conversion between the coordinate systems

In this section we show both directions. First, we show how one can get the pairs of the new system from the six-tuples.

Proposition 3

Let the six-tuple \((x_1,x_2,x_3,y_1,y_2,y_3)\) be given. Then

Now, we present the way the six-tuples can be computed from the new system. Thus, let a pair (u, v) addressing a tile be given. Then, depending on the type of the tile (that can be easily identified by Table 1), the formula shown in Table 3 result in the values of the six-tuple. The brackets of type \(\lfloor y\rfloor\) are used to denote the floor function giving the value of the largest integer that is not larger than y.

Digital distances

Digital distances and their computations are closely connected to shortest path algorithms. In general, from graph theory, the well-known Dijkstra algorithm can be used. However, since we work with periodic tilings, results for periodic graphs can also be applied19,20. On the other hand, based on the coordinate system we use, for various grids, greedy algorithms can provide shortest paths, see, e.g.,21,22 for the triangular, face-centered cubic and body centered cubic grids, respectively; while on some other girds, e.g., on rhombille tiling, this is not the case23.

As we have already mentioned, digital distances are step based distances, where a step is understood between neighbor tiles. There are two types of natural neighborhood relation in the grid, thus in this section we define and compute two types of digital distances. In fact, the result based on side-neighbors is not entirely new, it can be seen as a reformulation of the main result of1 with our new coordinate system. On the other hand, the distance based on the corner-neighbor relation was not studied before to the authors’ knowledge.

Let us define formally how we compute the digital distances in the 4-fold pentille grid, first we adapt the concept of paths to our grid.

Definition 2

Let \(\text{X}\in \{\text {side},\text {corner}\}\) and p and q be two tiles of the grid. A move from a tile to one of its X neighbors is called an X-step. A sequence of tiles in which each two consecutive tiles are X neighbors with the property that the first tile of the sequence is p and the last tile is q is an X-path from p to q. The length of an X-path is the number of X-steps in it. The X-distance of p and q is defined as the length of (one of) the shortest X-path(s) from p to q.

We have already defined two types of neighborhood relations, when we fix one of them we get the appropriate paths and distances belonging to that neighborhood. When it is clear from the context we may simply use the words step, path and distance instead of X-step, X-path and X-distance. Notice that each tile has 5 side-neighbors and 7 corner-neighbors, therefore, as side-neighbors are also corner-neighbors, all side-steps (side-paths) are also corner-steps (corner-paths, resp.).

Since these concepts are closely related to the graph theoretic analog concepts, we have the following immediate properties.

Proposition 4

Let \(\text{X}\in \{\text {side},\text {corner}\}\) and p, q, r be tiles of the grid. The shortest X-path includes 0 steps, i.e. contain a point only, if and only if \(p = q\). In other cases the X-distance has a value of a positive integer. The reversal of any X-path from p to q, that is, the order the elements of the sequence in opposite order, is an X-path from q to p. Thus, the X-distance is symmetric. Further, the concatenation of an X-path from p to q, and an X-path from q to r (that is attaching the sequence of tiles of the second path to the end of the first path instead of it last element q) is, in fact, an X-path from p to r, thus, the X-distance fulfills the triangular inequality. Therefore, the X-distance is a metric.

Whenever, a path is considered, the types of its tiles can also be used for its description as a sequence or as a word over the alphabet R, U, D, L. In this way a side-path segment in upward diagonal direction starting with a tile of type L and finishing at a tile type D, can be written as a word of L(DL)*D with the usual regular expression notation (see Figure 8). Although this description itself does not define the path uniquely, together with its direction (i.e., horizontal left or right, vertical upward or downward, or one of the four diagonal directions) knowing its starting and/or ending points (or length) the path (or its segment) is well defined. Thus, whenever we use this type of description, we always provide also the direction. One can consider a line through tiles, that is horizontal, vertical, or one of the diagonal directions and the sequence of types of tiles in the order intersecting the line defines these regular patterns for the given direction of the path segments.

Figure 9 shows the tiles having small distances form the tile type R \((-1,2)\). On the left the side-distance (all tiles are highlighted that have distance at most 5), on the right the corner-distance is used. Yellow tiles have distance 1, orange tiles have distance 2, brown tiles have distance 3, green tiles have distance 4 and pink tiles have distance 5 from the grey tile \((-1,2)\). (Note that in the case of the corner distance, all tiles with distance at most 3 are shown, but some tiles with distance 4 and 5 are missing from the figure.) The figure also underlines the difference between the two distances.

The side-neighbor distance

In this section we present a result that is equivalent to the main result of1. Instead of formal proof of this result, we are giving some hints to understand it. As it is a reformulation of the distance formula using the new coordinate system, it can formally be checked by considering all \(4\times 4\) cases for the types of the tiles p and q and consulting Table 3.

Theorem 1

Let \(p=(x,y)\) and \(q=(u,v)\) be two tiles. Their side-distance is

where \(\langle z\rangle\) gives the value of z rounded to the nearest integer.

Since the value of the sum of the maximum and the minimum of two values is the same as their sum, the formula of the theorem can also be written as

This form shows that, in fact, this distance function can be seen as a combination of the \(L_1\) and \(L_\infty\) distances, the basic distance functions based on the two different neighborhood (i.e., the side and the corner neighborhood) on the square grid.

Based on the structure of the grid, one may use 3-step horizontal and vertical blocks of steps in the paths. E.g., from a type D tile in vertical upward direction DURD or alternatively, DULD, during these three steps one of the coordinates changes by \(\pm 8\), while the other remains the same, e.g., in our previous example the second coordinate increases by 8, while the first has the same value after the three steps as before (see also Figure 10). Observe that from any tile, for each of the four directions of upwards, downward, left and right there are 3-step blocks with this property. Analogously, there are 2-step blocks in each of the four diagonal directions, e.g., RUR and DLD in upward diagonal direction by changing both coordinates by \(\pm 4\) (see Figure 10). Thus, intuitively, one can have a shortest path by concatenating two path segments (maybe one or both are empty), where one is horizontal (if the absolute valued coordinate difference is larger in the first coordinate than in the second) or vertical (if the absolute valued coordinate difference is larger in the second coordinate than in the first one) and a diagonal segment. In the diagonal segment each coordinate changes by an average \(\pm 2\) in each step, while in the other segment only one, the coordinate corresponding to the larger coordinate difference changes by an average of \(\pm \frac{8}{3}\) in each step.

The corner-neighbor distance

In this subsection, we use corner-paths and corner-distance. Apart from the steps we could use already in the previous subsection, for each tile there are two new options: those corner-steps that are not side-steps (see, Figure 6). These new options may help to change the coordinates faster in some of the directions. Let us define the following concept based on these corner-steps.

Definition 3

A sequence of tiles (containing each tile at most once), where each two consecutive elements are corner-neighbors, but not side-neighbors, is called a “fast track”.

Figure 11 shows examples for such fast tracks. One may observe that there are two types of them. The fast tracks having alternating tiles of types L and R are vertical, while the ones having alternating tiles of types U and D are horizontal. By using regular expression, a vertical direction fast track segment starting with a tile of type L and finishing at a tile type R, can be written as a word of L(RL)*R. The fast tracks allow to change a coordinate by \(\pm 4\) stepwise, while the other coordinate is either the same as originally (if we did even number of corner-steps) or changed by \(\pm 2\), depending on the type of the tiles of the fast track and on the direction. (Remember that in the previous section for horizontal and vertical directions one needed to have 3-steps for a coordinate change of \(\pm 2\).) Thus, it is expected that the distance will be always around one fourth of the absolute valued coordinate difference of the tiles. Now our task is to determine when and what is the correction value we need to apply.

Now, based on some combinatorial investigation (checking the coordinate changes in few consecutive steps to various directions), we define three types of directions depending on how the first step can be made in a shortest path. Without loss of generality, we show the lucky and unlucky directions (see also Figure 12) for R type tiles.

Let \(p = (x, y)\) be a tile of type R. Then for a tile \(q = (u, v)\) that is of type R or L, the unlucky directions are the horizontal directions, i.e., if \(y = v\). On the other hand, if q is of type L, then lucky directions include the direction of the two corner-neighbor (but not twin neighbor) L type tiles of p, more precisely, these directions are \(u > x\) and either \(v > y\) or \(v < y\).

From \(p = (x, y)\) to a tile \(q = (u, v)\) of type D, the lucky direction is \(u > x\) and \(v > y\). In this direction, e.g., the tile \(q = (x + 3, y + 7)\) can be reached by two steps: from p to its L type corner-neighbor and then to q. Similarly (and symmetrically), from \(p = (x, y)\) to a tile \(q = (u, v)\) of type U, the lucky direction is \(u > x\) and \(v < y\). In this direction, e.g., the tile \(q = (x + 3, y - 7)\) can be reached by two steps: from p to its L type corner-neighbor and then to q. On the other hand, the opposite directions to a type D or a type U tile are unlucky directions, respectively. For a tile \(q = (u, v)\) of type D with \(u < x\) and \(v < y\), it is in an unlucky direction. In this direction, e.g., the tile \(q = (x - 1, y - 5)\) can be reached by two steps, but the average coordinate change is less than 4. For a tile \(q = (u, v)\) of type U with \(u < x\) and \(v > y\), it is the unlucky direction.

The other, unexplained directions are neutral.

Generally, we may think about this as follows: Lucky, if the tile is already on a fast track in the desired direction. Unlucky, if one of the coordinates does not need to be changed and the fast track including the tile would change the other coordinate with a larger value than this. Finally, the case is neutral otherwise. Observe that the luckiness depends on both the start and target tiles, p and q, as well as on their respective location (direction).

We will use the parameter \(\lambda\) as a correction value in our formula. In lucky directions, its value will be \(-1\), in unlucky directions \(+1\), and 0 in neutral directions. As we can see, the direction and the types of the two tiles together determine this correction parameter.

The idea of the proofs is to provide a shortest path that contains either one or two corner-path segments. These segments are a fast track and/or a diagonal direction path such that, in the latter case, they have \(135^\circ\) between their directions. These path segments make the stepwise maximal coordinate changes with absolute value 4, on average, and also their “junction” (if any) provides the most efficient concatenation of segments in these directions. The value of \(\lambda\) depends on the luckiness of the direction, i.e., the efficiency (in terms of coordinate difference changes) of the possible first and last steps (starting from and arriving at the given types of tiles).

Without loss of generality, we may assume that one of the tiles is an R type tile.

Theorem 2

Let two R type tiles \(p = (x, y)\) and \(q = (u, v)\) be given. If the two tiles are the same, then their distance is 0. Otherwise, their corner-distance is

Proof

As both tiles are type R, both of their coordinate differences are divisible by 4. Since both tiles are type R, we may assume that \(v \ge y\). Then there are the following cases for a shortest path between the tiles:

-

Case \(y = v\): a path of the form RUD(UD)*R connects the tiles in a horizontal fast track (from left to right), resulting the distance \(\frac{|x - u|}{4} + 1\) as the first coordinate is changing by 3 in the first, by 1 in the last and by 4 in every intermediate steps. See Figure 13, from the red tile \((-9, 10)\) to the dark blue tile (15, 10) containing the green tiles. (Notice that, as usual in digital geometry and, in general, in graphs, there are alternative shortest paths (e.g., having tile (13, 10) instead of (14, 13)), but none of the changes could lead to a shorter path.)

-

Case \(u - x> v - y > 0\): a path R(UR)*UD(UD)*R connects them from left to right, where the first part, belonging to R(UR)*U is an upward diagonal segment that is also side-connected path, the part belongs to U(DU)* is a horizontal fast track with a last step arriving to the target tile. The coordinate changes are the same, stepwise 2 in the average, in the two coordinates in the first segment together with the last step (also a step from type U to D at up-diagonal direction), and the first coordinate is changing by 4 in the fast track while the second coordinate is the same in the end as it was. Altogether, each step gives an average of 4 coordinate changes supporting the formula. See Figure 13, from the purple tile \((-21, -2)\) till the dark blue tile, the path is shown in turquoise, red and green tiles.

-

Case \(u - x = v - y > 0\): a path R(UR)* connects them from left to right. As this shortest path is side-connected, the distance is exactly the same in this case as at the side-connected case. See, e.g., the path from the already mentioned purple tile to the red tile or the yellow path from the orange tile \((3, -10)\) to the khaki tile (15, 2).

-

Case \(v - y> u - x > 0\): a path R(UR)*(LR)* connects them from left to right. The first part is similar to the previous case, then a vertical fast track finishes the path, again, the average coordinate change is 4 for each step of the path. See, e.g., the path from the orange tile to the dark blue tile (with tiles in yellow, khaki and steel blue).

-

Case \(v - y > u - x = 0\): a path R(LR)* connects them in a vertical fast lane, changing the second coordinate by 4 in each step. See, the path between the grey \((-9, -6)\) and red \((-9, 10)\) tiles (in light grey).

-

Case \(v - y> 0 > u - x\) and \(|v - y| > |u - x|\): a path R(DR)*(LR)* connects them from bottom-up direction, where the first part is a side connected diagonal in up-left direction, and then, a vertical fast track. Again, the average coordinate change is 4 by the steps. Example for such case is the path from the orange tile \((3, -10)\) to the red tile \((-9, 10)\) where the path includes the blue and then some of the light grey tiles.

-

Case \(v - y> 0 > u - x\) and \(|v - y| = |u - x|\): a path R(DR)* connects them. This path is also a side connected path, and the distance is same as the side-distance. An example is the path from the orange tile to the grey tile \((-9, 2)\) containing the blue tiles.

-

Case \(v - y> 0 > u - x\) and \(|v - y| < |u - x|\): a path R(DU)*D(RD)*R connects them in right to left direction, where the first part, after the first step is a horizontal fast track, and then the path is continuing as the previous case. See, the path from the khaki tile (15, 2) to the red tile containing the pink (DU)*, the purple D and the orange (RD) tiles.

Finally, as there is no way to change the coordinate values with more than 4 in average, in a path between same type of tiles, there is no way to make shorter paths than those which have been specified, and thus, the proof is completed. \(\square\)

Based on the symmetry of the grid (e.g., rotations by 90, 180 or 270 degrees), the result of Theorem 2 can be transformed to other types of tiles as follows.

Corollary 1

The corner-distance of two distinct tiles \(p = (x, y)\) and \(q = (u, v)\) is

if they are both type L. On the other hand, if both tiles are of type U or both are of type D, then

Now, let us consider the cases when the tiles are different, i.e., p is of type R, but the second tile q is of another type.

Theorem 3

Let two tiles \(p = (x, y)\) and \(q = (u, v)\) be given such that p is an R type tile and q is a D type tile. Their corner-distance is

where

Proof

There are the following cases for a shortest path between the tiles, starting from p:

-

Case \(u - x> v - y > 0\): A path RU(DU)*(DL)*D connects them from left to right, where the first part, after the first step, is a corner-path on a horizontal fast track, then (DL)*D is an upward diagonal segment that is also side-path. For these tiles, this is the lucky direction, as both in the first and last steps, both coordinates are changing to the direction of the tile q from p, i.e., increasing. The path can also be reordered to start as RUD, and then continues by parts with (UD)* and (LD)*. As in a 2-step path RUD in this direction, the change is \((+7, +3)\), this together with the concatenated shortest path between the reached type D tile \((x+7, y+3)\) and tile q, knowing from Corollary 1 (based on Theorem 1) that their shortest path in this direction changes the coordinates by 4 in the average leads to the proof of the formula with \(\lambda = -1\). Figure 14 (left) shows an example from the black tile \((-13,-10)\) to the orange tile (22, 5).

-

Case \(v - y> u - x > 0\): A path R(UR)*(LR)*LD connects them from left to right. The first part is side connected, then a vertical fast track can be used, till the last step from a type U tile to the tile q. This is still the lucky direction. The last 2 steps: RLD give \((+3, +7)\), while before that from R to R we can do by changing 4 values in the coordinates stepwise. Figure 14 (left) shows an example from the black tile \((-13,-10)\) to the green tile \((-2,13)\).

-

Case \(u - x> 0 > v - y\) and \(|v - y| > |u - x|\): A path R(LR)*(DR)*D connects them. The first part is a vertical fast track, and then a side connected diagonal. The average coordinate change is 4 by the steps. This case is neutral. An example path is in the picture on the right of Figure 14 from the grey tile \((-5,14)\) to the red tile \((2,-7)\).

-

Case \(u - x> 0 > v - y\) and \(|v - y| < |u - x|\): A path R(DU)*(DR)*D connects them. The first part, after the first step is a horizontal fast track, and then the path is continuing as the previous case leading to the formula of the neutral case again. See the path from the grey tile \((-5,14)\) to the blue tile (22, 5) in Figure 14 (right).

-

Case \(v - y> 0 > u - x\) and \(|v - y| > |u - x|\): A path R(LR)*(DR)*D connects them. The first part is a vertical fast track, and then a side connected diagonal may be applied. Again, the average coordinate change is 4 by the steps. An example is shown in Figure 15 (left), from the grey to the purple tile.

-

Case \(v - y> 0 > u - x\) and \(|v - y| < |u - x|\): A path R(DR)*(DU)*D connects them. The first part is a side-path, then a horizontal fast track may come. An example is shown in Figure 15 (left), from the grey to the brown tile.

-

Case \(0> v - y > u - x\): A path R(UR)*U(DU)*D connects them with a side connected first part and the horizontal fast track. However, here the pattern RUD gives \((-1, -5)\) coordinate changes showing the unlucky case (in these two steps only 6 changes, while in all other the average is 4). An example is shown in Figure 15 (right), from the grey to the yellow tile (the other tiles of the path are light blue and green).

-

Case \(0> u - x > v - y\): A path R(UR)*(LR)*LD connects them with a side connected first part and a vertical fast track. However, here the pattern RLD gives \((-5, -1)\) coordinate changes showing the unlucky case (in these two steps only 6 changes, while in all other the average is 4). An example is shown in Figure 15 (right), from the grey to the red tile (the other tiles of the path are light blue and purple).

As each case has been investigated, the theorem has been proven. \(\square\)

Theorem 4

Let two tiles \(p = (x, y)\) and \(q = (u, v)\) be given such that \(p\) is an R type tile and \(q\) is a U type tile. Their corner-distance is

where

Proof

When q is type U, the case is symmetrical to a horizontal symmetry axis to the case when q is of type D, thus the statement is “the mirror” of Theorem 3. \(\square\)

Theorem 5

Let two tiles \(p = (x, y)\) and \(q = (u, v)\) be given such that p is an R type tile and q is an L type tile. If p and q are not neighbors, then their corner-distance is

where

Proof

The proof goes by cases for a possible shortest path between the tiles starting from \(p\). On the other hand, we may assume that \(v \ge y\) by the symmetry of the grid (otherwise instead of \(q\) one can use the tile \(q' = (u, 2y - v)\) having the same distance from \(p\)).

-

Case \(u - x> v - y > 0\): A path R(UR)*(UD)*UDL connects them from left to right, where the first part is a side-path in upward diagonal direction, then a corner-path on a horizontal fast track, then (UD)* follows expanded by the last side-step to reach tile \(q\). For these tiles, this is the lucky direction, as the 3 steps included in the pattern RUDL (i.e., the first step of the described path with the last two steps) change the coordinates by \((+10, +4)\). The other steps give an average change of 4, and thus, the formula with \(\lambda = -1\) applies. Figure 16 (left) shows an example from the grey tile to the orange tile (the other tiles of the path are the purple and the yellow tiles).

-

Case \(v - y> u - x > 0\): A path R(LR)*(LD)*L connects them from left to right. The first part is on a vertical fast track, then a side connected part can finish the path. This is still the lucky direction, the first step: RL gives \((+2, +4)\), while after that from L to L we can do by changing average 4 values in the coordinates stepwise. Figure 16 (left) shows an example from the grey tile to the dark green tile (the other tiles of the path are green).

-

Case \(u - x > v - y = 0\): A path R(UD)*UL connects them. In this case, the tiles \(p\) and \(q\) are on the same horizontal position, thus the formula already gives \(+1\) for the value based on their coordinate difference: \((u - x)/4\). On the other hand, the first and the last steps (could be written together as a path RUL), give altogether \(+6\) coordinate changes, while the average for other steps is \(+4\). In this way, considering the \(+1\) value that is already added in the formula, \(\lambda = -1\) applies. Figure 16 (left) shows an example from the grey tile to the brown tile (the other tiles of the path are the purple and the red tiles).

-

Case \(v - y> 0 > u - x\) with \(|v - y| < |u - x|\): A path R(DU)*D(UL)*UL connects them. The first part is on a horizontal fast track to the left, then a side connected part can finish the path. The pattern RDUL includes the steps that change the coordinates by \((-6, +4)\), altogether by 10 in 3 steps. The average of the other steps is 4, and thus, \(\lambda = 1\) applies. Figure 16 (right) shows an example from the grey tile to the blue tile (the other tiles of the path are the light yellow and turquoise tiles).

-

Case \(v - y> 0 > u - x\) with \(|v - y| > |u - x|\): A path R(LU)*(LR)*L connects the tiles. The first part is a side-path, then a vertical fast track finishes. The first step RL changes the coordinates by 2, while on average, the other steps by 4, thus again, \(\lambda = 1\) applies in the formula. Figure 16 (right) shows an example from the grey tile to the red tile (the other tiles of the path are pink).

-

Case \(v - y = 0 > u - x\): A path R(DU)*DL connects them (using a horizontal fast track to the left), and as they are not neighbors, in fact the path consists of at least 4 steps that can be described by the pattern RDUDL. The first coordinate changes by \(-1\) in the first and also in the last step, while by \(-4\) in every other step, hence resulting in a \(+1.5\) correction value to the formula based only on the coordinate differences in the first coordinate. A correction 1 is already applied, as the second coordinates of the tiles \(p\) and \(q\) are the same, thus an additional \(+\frac{1}{2}\) applies resulting \(\lambda = 1\). Figure 16 (right) shows an example from the grey tile to the yellow tile of type \(L\) where the other tiles of the path are the light yellow.

Finally, we notice that the formula can also be used if \(p\) and \(q\) are corner-neighbors, but not side-neighbors. However, if they are twins, their distance is definitely 1, but the formula gives 2. This is the only exception, where the formula cannot be used, as the case would belong to the last case, where the first and the last step would be identical if the tiles are twins. With this note, the proof is completed. \(\square\)

By rotating the grid by 90, 180, and 270 degrees in the clockwise direction, distances from tiles of type D, L, and U can be obtained based on cases according to the type of the other tile and lucky, neutral, and unlucky directions.

Conclusions

We have provided a new coordinate system for the 4-fold pentille grid (aka. Cairo pattern) which addresses the tiles with integer coordinate pairs. We believe that this new coordinate system is very helpful for various communities including computer graphics, digital image processing, networking, and crystallography, since it gives a simple way to work with the grid in mathematical manner. This framework works also for other edge to edge pentagonal tessellations of type b and c (type 2 and 4 in8,14).

On the other hand, we have given (graph theoretical, i.e., digital) distances between any two tiles of the grid, where the distance is measured as the number of steps in a shortest path between the tiles. The result using the corner-neighborhood is entirely new and shows that there are directions where the corner-steps can help to connect the tiles with a shorter path than by only steps between side-neighbors.

We believe that this pentagonal grid can also be applied in various places, and our result can support these application areas including digital image processing (e.g. binary tomography24), computer graphics, crystallography and simulations in physics.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Kovács, G., Nagy, B. & Turgay, N. D. Distance on the Cairo pattern. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 145, 141–146 (2021).

Zhuang, H. L. From pentagonal geometries to two-dimensional materials. Comput. Mater. Sci. 159, 448–453 (2019).

Kaplan, C. S. Introductory Tiling Theory for Computer Graphics, (Synthesis Lectures on Computer Graphics and Animation) (Springer, 2022).

Nagy, B.: Non-traditional 2D Grids in Combinatorial Imaging – Advances and Challenges. In: IWCIA 2022: 21st International Workshop on Combinatorial Image Analysis, LNCS 13348, pp. 3–27 (2023).

Borgefors, G. A semiregular image grid. J. Vis. Commun. Image R. 1(2), 127–136 (1990).

Conway, J. H., Burgiel, H. & Goodman-Strauss, C. The Symmetries of Things (CRC Press, 2016).

Rao, M.: Exhaustive search of convex pentagons which tile the plane. arXiv preprint arXiv:1708.00274 (2017).

Sugimoto, T. Convex pentagons for edge-to-edge tiling. III. Graphs and Combin. 32(2), 785–799 (2016).

MacMahon, P. A. New Mathematical Pastimes (Cambridge University Press, 1921).

Chung, P. N. et al. Isoperimetric pentagonal tilings. Notices Amer. Math. Soc. 59(5), 632–640 (2012).

Chung, P. N., Fernandez, M. A., Shah, N., Vieira, L. S. & Wikner, E. Perimeter-minimizing pentagonal tilings. Involve 7, 453–478 (2014).

Saadat, M., Nagy, B.: Digital geometry on the dual of some semi-regular tessellations. In: Lindblad, J., Malmberg, F., Sladoje, N. (eds.) DGMM: First International Joint Conference on Discrete Geometry and Mathematical Morphology, LNCS 12708, pp. 283–295 (2021).

Reinhardt, K.: Über die Zerlegung der Ebene in Polygone. Dissertation, Universität Frankfurt (1918).

Kershner, R. B. On paving the plane. Amer. Math. Monthly 75(8), 839–844 (1968).

Schattschneider, D.: In praise of amateurs. In: The Mathematical Gardner, 140–166 (1981).

Turgay, N. D., Nagy, B., Kovács, G. & Vizvári, B. Weighted distances in the Cairo pattern. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 166, 105–111 (2023).

Kovács, G., Nagy, B., Stomfai, G., Turgay, N. D. & Vizvári, B. On chamfer distances on the square and body-centered cubic grids: An operational research approach. Math. Probl. Eng. 1, 5582034 (2021).

MacMillan, R. H. Pyramids and pavements: Some thoughts from Cairo. Math. Gazette 63(426), 251–255 (1979).

Höfting, F. & Wanke, E. Minimum Cost Paths in Periodic Graphs. SIAM J. Comput. 24, 1051–1067 (1995).

Fu, N.: A Strongly Polynomial Time Algorithm for the Shortest Path Problem on Coherent Planar Periodic Graphs. In: Chao, KM., Hsu, Ts., Lee, DT. (eds) Algorithms and Computation. ISAAC 2012. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 7676. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. 392–401 (2012).

Nagy, B. Weighted distances and distance transforms on the triangular tiling. Trans. GIS 27(7), 2042–2098 (2023).

Strand, R., Nagy, B.: Weighted Neighbourhood Sequences in Non-Standard Three-Dimensional Grids – Metricity and Algorithms. In: Coeurjolly, D. et al. (eds) 14th IAPR International Conference Discrete Geometry for Computer Imagery. DGCI 2008. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 4992, Springer 201–212 (2008).

Nagy, B. & Saadat, M. R. Digital geometry on a cubic stair-case mesh. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 164, 140–147 (2022).

Nagy, B. & Lukic, T. Binary tomography on the cairo pattern. In: Proceedings of IWCIA 2025: 23rd International Workshop on Combinatorial Image Analysis, Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Springer, 2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The problem was investigated by B.N. The literature was reviewed by B.N. and MR.S. The computations were done by B.N. and MR.S., while the formal proofs by B.N. The manuscript was written by B.N. and MR.S. MR.S. did also programming and visualization, B.N. has also supervised the project. Both authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nagy, B., Saadat, M. Digital distances on the 4-fold pentille tessellation. Sci Rep 15, 35601 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17010-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17010-4