Abstract

Local Intensive Precipitation (LIP), intensified by climate change, has increasingly caused severe urban flooding. Although traditional hydrodynamic models such as SWMM and FLO-2D offer high accuracy in flood prediction, their computational demands hinder real-time application. This study introduces a rapid flood depth prediction model based on a Support Vector Machine (SVM), trained with data generated from a physically-based 1D–2D coupled simulation. The target area is the Jinheung Apartment intersection in Gangnam, Seoul—an area highly prone to flooding. Cumulative rainfall and manhole overflow data from 1 to 5 h scenarios were used as input variables to predict flood depth. Model validation consisted of two parts: (1) the 1D–2D hydrodynamic model (SWMM–FLO-2D) was validated using observed flood records from September 21, 2010, achieving a 64% match with NDMS inundation points. (2) The trained SVM model was verified by comparing its predictions against FLO-2D results generated using a 3-hour Huff-distributed rainfall scenario. The SVM model showed strong performance with R2 = 0.988, NSE = 0.987, % difference = 1.080, and RMSE = 0.098 m. The results confirm that integrating machine learning with physical simulation can provide fast and reliable flood predictions, supporting timely disaster response in urban areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Recently Due to global warming and abnormal climate LIP and typhoons frequently occur Causing flood damage in urban areas in addition, in Korea, The Pattern is changing according to climate change, and the frequency of floods is also increasing1.

In this study, LIP refers to short-duration, high-intensity rainfall concentrated in a small urban area, typically exceeding 30–50 mm/h over a spatial scale of less than 10 km2. Additionally, the term “Local Intense Precipitation” is used in nuclear safety engineering, such as by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) and OECD/NEA, to characterize design-basis rainfall events for external flooding assessments around critical infrastructure. However, in this paper, the term is used specifically in the context of Korean urban flood forecasting2.

On September 21, 2010, rainfall exceeding 100 mm per hour occurred in Seoul, Incheon, Gyeonggi, and Yeongseo region among cities located in Korea. As a result, 5700 households were damaged and 13,900 people were displaced3. On July 27, 2011, torrential rain of 110.5 mm per hour occurred in Seoul, Gangwon-do, Yeongseo, and Gyeongsangnam-do. As a result, damages such as landslides, manhole overflows, and river overflows occurred4. On October 5, 2016, due to rainfall of 139 mm per hour during Typhoon Chaba, houses, shops, and roads were flooded in Gyeongsangnam-do, Busan Metropolitan City, and Ulsan Metropolitan City, located in the south of Korea. In the same context, the occurrence of super typhoons on the Korean Peninsula is also increasing5. While Korea has faced several extreme rainfall events in recent years, similar patterns are observed globally under the influence of climate change. The following studies illustrate how other countries have approached flood risk analysis and adaptation. Tabari examined extreme precipitation trends under climate change, and Xie et al. developed a Bayesian-network-based approach for regional flood scenario development6,7. Additionally, the emergency response process for storms and floods was studied using Bayesian networks8. Similarly, in China, a flash flood risk assessment was conducted based on SSP scenarios9. And future flash flood inundation in coastal areas was assessed under climate change scenarios10. Therefore, there is a need for a technique capable of predicting and analyzing the damage caused by localized heavy rain in a short time.

To address these challenges, various countries, including Korea, have increasingly applied machine learning techniques to flood prediction and impact assessment. In Korea, models based on machine learning have been developed to forecast monthly inflow into multipurpose dams in the Han River basin11 and to predict localized extreme rainfall events12. Other studies have utilized Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and logistic regression to estimate inundation extent in urban areas13.

Internationally, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and LSTM architecture have demonstrated strong performance in predicting flood depth over large spatial and temporal scales using topographical and historical rainfall data14,15. Likewise,machine learning, especially SVM, has been widely applied in flood prediction research. Yu et al. successfully applied support vector regression (SVR) for real-time flood stage forecasting, demonstrating its effectiveness in modeling nonlinear hydrological processes16. Similarly, Han et al. employed SVM to predict flood peaks using rainfall-runoff data with high accuracy17. Furthermore, SVM-based models were used for hourly reservoir inflow forecasting during typhoon warning periods18, emphasizing their suitability in operational hydrology.

A broad review by Mosavi et al. introduced various machine learning models and highlighted SVM as a promising method for both short- and long-term flood predictions19. Nong et al. further explored support vector regression combined with feature engineering and optimization for dissolved oxygen forecasting, underscoring its potential for complex environmental prediction tasks20. In small mountainous catchments, SVM has proven effective in flash flood forecasting, as shown by Wu et al21.

Hybrid and ensemble approaches have also emerged. Anaraki et al. analyzed flood frequency uncertainty under climate change using hybrid ML methods22, and Islam et al. proposed novel ensemble models like Dagger and Random Subspace (RS) that combine ANN, RF, and SVM23. In addition, Dhara et al. applied SVM with multi-satellite imagery to reconstruct flood patterns in Vietnam, showcasing its versatility in remote sensing-based flood mapping24. As such, various machine learning techniques have been employed in flood analysis. In our study, we employed an SVM model to predict flood depth in real time for flood-prone areas.

To clearly articulate the logical basis and originality of this study, a conceptual framework is presented in Fig. 1. This diagram shows the chain of causality from climate change and extreme rainfall to urban flooding, highlights the computational limitations of conventional 1D–2D models such as SWMM and FLO-2D, and visually explains the rationale for introducing a SVM-based real-time flood depth prediction model.

Therefore, the objective of this study is to develop a real-time flood depth prediction model for urban areas that are frequently affected by flooding. The proposed model aims to estimate flood depth over time with a level of accuracy comparable to that of physically based simulations. To achieve this, a three-step methodology is employed. First, a one-dimensional–two-dimensional (1D–2D) hydrodynamic flood simulation model (SWMM–FLO-2D) is constructed and validated using a historical rainfall event. Second, the simulation results—specifically, cumulative rainfall and overflow—are used to generate synthetic training data. Finally, a SVM model is trained to predict time-series flood depth at a designated target point.

The novelty of this study lies in the integration of physically based hydrodynamic modeling with machine learning in forecasting framework. Unlike conventional machine learning approaches that rely on large volumes of observational data, the proposed model uses simulation-generated flood data from a verified 1D–2D numerical model to train the SVM. This enables rapid and reliable flood depth prediction without the need to rerun complex numerical simulations for each new rainfall input. The model therefore retains the physical interpretability of traditional hydrodynamic approaches while significantly reducing computational burden, making it well-suited for real-time applications in data-scarce but flood-prone urban environments.

Furthermore, this study contributes a practical solution for urban areas where observed flood data are limited or unavailable. By training the model on physically consistent simulation outputs, the framework offers a robust alternative to data-driven models that require extensive historical records. The SVM-based prediction model can produce flood depth forecasts within seconds, enabling timely dissemination of flood information during extreme rainfall events. Ultimately, the proposed approach supports early warning systems and facilitates effective flood risk mitigation by minimizing potential damage to life and property.

Methodology

The overall content of this study is as follows. First, rainfall events and runoff data in the study area were collected. Second, based on the collected data, a one-dimensional (1D) numerical model was built to calculate the amount of overflow in the manhole. Third, inundation analysis was conducted by constructing a two-dimensional (2D) numerical analysis model using the calculated overflow and terrain data. After that, calibration was performed by comparing the 2D flooding analysis result with the observed flooding extent. The calibration of the 2D hydraulic model was performed by comparing the simulated flood extent from the FLO-2D model with observed inundation points obtained from the National Disaster Management System (NDMS). The Manning’s roughness coefficient was iteratively adjusted based on the spatial agreement between simulated and observed flood extents to ensure that the numerical model realistically captured the observed flood behavior. Fourth, the probability of rainfall events for various scenarios was calculated to build a real-time inundation prediction model. After that, inundation analysis was conducted for each scenario through verified 1D-2D numerical analysis of the calculated design storm rainfall. Fifth, the flood depth data calculated through flood analysis was applied as training data for SVM. The trained SVM model was then used to predict the hourly flood depth for the flood-prone area. Finally, the model’s validity was verified by comparing the results predicted by the SVM model with the results of the verified numerical model. The flow chart of this study is shown in Fig. 2.

1D and 2D Model. In this study, SWMM was used as the 1D model. The SWMM model, a stormwater management model developed by the U.S. Environmental Conservation Agency, reflects the physical characteristics of surface flow runoff analysis. It is a model widely applied in complex hydrology, hydraulics, and water quality caused by stormwater in urban areas. Also, it calculates the amount of flooding that causes backflow in the pipe when rainwater is not drained correctly due to a rise in water level at the final outflow point, such as a rise in river water level. The SWMM model is more suitable for applying hydraulic flow calculations through dynamic tracking than the ILLUDAS model, which uses storage equations.

To integrate surface inundation with subsurface overflow dynamics, this study employed a one-way coupling approach between the SWMM and FLO-2D models. Specifically, overflow discharges at selected manholes—calculated by the 1D SWMM simulation—were extracted and used as point inflow boundary conditions in the 2D FLO-2D model. The temporal discharge data were mapped to the corresponding spatial locations of each manhole within the FLO-2D grid. This method allowed for the surface flooding caused by sewer surcharge to be dynamically simulated while maintaining computational efficiency. The data transfer was handled externally and manually, without using FLO-2D’s built-in SWMM interface.

The continuity equation in the sub-basin is as follows.

Here, \({V}_{o}\)= Volume of flow (m3) = \({A}_{surf}\times d\)

\(\text{d}\)= Depth of surface flow (m)

\(\text{t}\)= Time (sec)

\({A}_{surf}\)= Surface area (m2)

\({i}^{*}\)= Excess rainfall (m/s)

\(\text{Q}\)= Flow rate (m3/s)

The runoff volume is expressed using Manning’s formula.

Here, \(\text{W}\)= Sub-basin width (m)

n = Manning roughness coefficient

\({d}_{p}\)= Ground storage depth (m)

\(\text{S}\) = Slope (m/m)

The nonlinear differential equation by substituting Eq. (2) into Eq. (1) to calculate the unknown value d is as Eq. (3). Here, the basin width, slope, and roughness coefficient are determined and replaced with one parameter.

Here, \(\text{WCON}\)= \(-\frac{W\times {S}^{1/2}}{A\times n}\)

Equation (3) can be solved using the finite difference method in each calculation time interval. When applying the difference method, the inflow and outflow in the right-hand term are average values over a time interval. The excess rainfall i* is the average value at each time interval and is given by the program as input data in each calculation section. The average outflow is calculated using the average of the water depths at the beginning and end of the calculation. If d1 is defined as the water depth at t time and d2 is the water depth at t+△t, Eq. (3) can be expressed as the following difference equation.

In the above equation, d2 is solved using the Newton-Raphson iteration method. Given d2, the runoff is calculated for each time interval using Manning’s equation. The results are also used as input data (Q) for the nodes and links of the drainage system.

FLO-2D was used for the 2D model. The two-dimensional finite difference model FLO-2D is a numerical model that tracks non-Newtonian flood flow in areas. The purpose of developing this model is to evaluate the range of possible flow characteristics of flow speed and depth, predict flood extent, and even identify flood interruption situations. This model has been applied to various flood flow analyses, such as the 1983 Rudd Creek mudflow.

The advantage of this model is that it can track various flood and inundation events in urban areas. Also, it is possible to predict the amount of flooding in a waterway and the flow in a floodplain with a complex topographical structure using various river channel cross-sectional characteristics. This model is designed to evaluate the flow considering obstacles such as buildings. Therefore, it can be effectively applied to flood analysis in urbanized or floodplain areas.

The constitutive equations of the two-dimensional model consist of continuity equations and equations of motion.

Here, h is the water depth of the flow, \({V}_{x,} {V}_{y}\) is the average flow velocity in the x and y directions, and \(i\), the excess rainfall in the target basin, may not be 0. The friction slope in Eqs. (6) and (7) is described in channel bottom slope, pressure slope, convection, and local acceleration terms.

The diffusion-type approximate solution to the equation of motion is considered by ignoring the latter three terms of Eqs. (6) and (7). If the pressure term is omitted, the previous motion wave equation is derived. This model was constructed to enable approximate solutions for both kinematic and diffusive waves.

Support Vector Machine (SVM). SVM is a supervised learning algorithm used primarily for classification and regression tasks. As a kernel-based method introduced by Vapnik25, SVM employs the Structural Risk Minimization (SRM) principle26, which enables it to minimize generalization errors more effectively than conventional neural networks. One of the key advantages of SVM is its robustness in situations with limited training data, where it can still deliver high prediction accuracy. Given the nature of the flood simulation dataset in this study—where the data are computationally expensive to generate and limited in quantity—SVM is a suitable choice. Furthermore, its ability to capture nonlinear relationships between input variables through kernel functions and its relatively fast computation speed make it well-aligned with the objectives of real-time flood depth prediction. The theory of SVM is as shown in Eq. (8).

Each training data sample is given an output value from the hyperplane. To find the optimal hyperplane, the following Eq. (9) is minimized and expressed as Eq. (10).

However, errors generally occur as most input data is classified according to the binary method. In this case, the goal is to classify the training data by minimizing errors. To this end, a slack variable with a positive value and a penalty function were introduced. In this case, it should be optimized to be minimized as shown in Eqs. (11–12).

Here C is a penalty function and control variable with a trade-off relationship between maximizing margin and minimizing classification error. C is a variable that acts as a penalty for unseparated data. As the C value increases, the optimal hyperplane minimizes the classification error.

Conversely, a smaller value of C indicates a tendency to optimize under conditions that maximize margin. Also, if SVM does not linearly perform binary classification, linear classification is possible by applying a kernel function using a non-linear method25. The choice of kernel function could greatly affect classification performance using SVM. Types of kernel functions include Linear kernel, Polynomial kernel, Gaussian kernel, and sigmoid kernel.

Model application

The Gangnam drainage area suffered a lot of flooding damage due to torrential rain on September 21, 2010. Therefore, a 1D urban runoff analysis model was constructed using the rainfall and stormwater pipeline at that time for the study area. The calibration and validation of the coupled 1D–2D hydrodynamic model were based on two major historical rainfall events that resulted in observed flood damage in the study area. However, since the model structure and validation results were consistent across both events, the manuscript presents only one representative case (September 21, 2010) in detail to avoid redundancy. This approach ensures that model credibility is preserved while maintaining a clear and concise presentation of the methodology. Based on the constructed model, the overflow in the manhole was calculated through a 1D urban runoff analysis. The goodness of fit analysis of the model was performed by comparing the results of the flood analysis, which applied this overflow as the point sources of the 2D flood inundation model, with the observed flood extent.

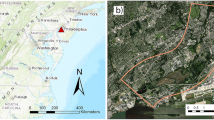

Study Area. The study area is the Gangnam area of Seoul, Korea as shown in Fig. 3. The topographic elevation of the Gangnam Station area is 12 m lower than that of the nearby Seocho area and about 18 m lower than that of the Yeoksam Station area. Among them, the intersection of Jinheung Apartment near Gangnam Station is the lowest area and is a habitually flooded area. Based on both historical flood records and municipal reports, this area has experienced recurrent inundation events. In addition, the surrounding zone includes high-density commercial and residential facilities, making it a critical area in terms of potential economic damage. Therefore, the manhole at this location was selected as the representative point for predictive modeling.

Satellite images of the study area: a Korea; b Gangnam Area, map generated in the ArcGIS 10.1 (Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI), https://www.esri.com/).

Construction and Application of SWMM. To incorporate the observed rainfall into the 1D urban runoff model, the Automatic Weather System (AWS) data of the Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA) was used. Among the data from the KMA, the 24-hour rainfall that caused flooding in the Gangnam area on September 21, 2010, was time-distributed at 10-minute intervals and configured as SWMM input data, as shown in Fig. 4. The 24-hour cumulative rainfall is 293 mm, and the hourly peak rainfall is 64.5 mm/hr on September 21, 2010. In addition, according to the National Institute of Meteorological Sciences (NIMS), with rainfall of 20 mm and 40 mm/hr, the disaster rate increases to 50 % and 80 %, respectively.

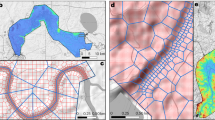

To simulate the 1D urban runoff analysis for the Gangnam drainage area, the entire Gangnam area was divided into 771 sub-basins. Each sub-basin was classified based on data such as roads and contours. In addition, the SWMM model was constructed with 774 manholes, 1060 conduits, and 772 junctions using the pipe network data of the Gangnam drainage area as shown in Fig. 5.

Watershed and drainage network: a Watershed; b Drainage network, map generated in the ArcGIS 10.1 (ESRI, https://www.esri.com/).

Runoff analysis was performed in the study area with the SWMM constructed with the data described above. As a result of the SWMM simulation, overflow occurred in a total of 8 manholes. Fig. 6 shows the amount of overflow in 5 manholes with an overflow of 1 m3/s or more among the 8. As shown in Fig. 6, the overflow at manhole No. 3 was the largest at a maximum of 22.8 m3/s.

2D Flood Inundation Modeling. To construct the topographical data for the application of the 2D surface inundation model, the Digital Elevation Model (DEM) based on aerial Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) was used. Fig. 7 shows the DEM and boundaries of the study area. For the 2D flood inundation analysis, the size of the grid was generated as 5 × 5 m.

DEM and boundary for study area, map generated in the ArcGIS 10.1 (ESRI, https://www.esri.com/).

The urban area is densely populated with roads and buildings. These facilities increase the building-to-land ratio in urban areas, so they have a great influence on flooding. Therefore, it is necessary to construct topographical data considering roads and buildings for urban flood modeling. The effects of buildings and roads on the flow direction and flow speed in urban flood modeling were quantitatively analyzed, and the simulation results considering facilities showed higher accuracy27,28. In this study, to consider the building-to-land ratio in urban areas, not only the grid reflecting roads and buildings, but also the composite roughness coefficient was applied. Equations are shown in (13) and (14).

where, \(n\) is the composite roughness coefficient, \({n}_{0}\) is the bottom roughness coefficient, \(\theta\) is the building-to-land ratio (%), \({n}_{1}\)=0.060, (farmland), \({n}_{2}\)=0.047 (road), \({n}_{3}\)=0.050 (other), \({A}_{1}\) is the farmland area, \({A}_{2}\) is the road area, \({A}_{3}\) is other land use area, and \(h\) is water depth (m).

Building-to-land ratio and water depth are the most important variables in calculating the composite roughness coefficient26. Building-to-land ratio in urban areas can be calculated using GIS Tool, but it is not easy to calculate water depth because it changes according to rainfall and manhole overflow. In this study, the maximum flooding depth was identified as 0.8m in the photograph of the flooding that occurred in the study area on September 21, 2010, and 0.025 was calculated as a composite roughness coefficient.

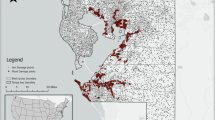

As a result of the 2D flooding analysis, the deepest flooding depth occurred at the intersection of Jinheung Apartment near Gangnam Station as shown in Fig. 8. To compare the results of 2D flooding analysis with the actual flooding, the NDMS data was used. The NDMS includes the points where flood damage occurred as reported by residents, and is indicated as points, not as areas. Therefore, the area around the NDMS point was flooded (yellow circle in Fig. 9). In addition, the goodness of fit was estimated by applying Eq. (15) and shown in Table 1. Since NDMS only exists as point data, the goodness of fit was estimated by the number of reported points within the calculated inundation area.

Maximum flood depth result on Sep. 21, 2010, map generated in the ArcGIS 10.1 (ESRI, https://www.esri.com/).

Comparison of NDMS data and calculated flood extent on Sep. 21, 2010, map generated in the ArcGIS 10.1 (ESRI, https://www.esri.com/).

NDMS data includes problems such as aggregation delay and duplication between field surveys and office inputs. In addition, GPS inaccuracies and spatial mismatches have been reported27. Especially in downtown areas with dense infrastructure, it is difficult to achieve high spatial accuracy due to reporting limitations. Moreover, because the data are based on citizen reports collected via mobile devices, the most severely flooded zones—such as underground roads or areas with deep water—may be inaccessible and thus unreported. As a result, NDMS data are more suitable for validating general flood extent rather than detecting flood intensity or exact depth distribution. Considering these limitations, the 1D and 2D model results still showed a reasonably good match with reported flood points.

Development of flood depth prediction model over time

Estimation of precipitation under given return periods. The frequency-based precipitation values used in this study were derived from the Seoul (108) meteorological station. Rainfall frequency analysis was performed using maximum observed rainfall depths for durations ranging from 10 minutes to 24 hours. The analysis was conducted using the Frequency Analysis for Rainfall Data software(FARD 2006), developed by the National Disaster Management Research Institute (NDMI) of Korea. The software is freely available at the official NDMI website: https://www.ndmi.go.kr (in Korean). FARD 2006 supports the application of 13 different probability distributions (e.g., Gumbel, GEV, Lognormal) and performs statistical goodness-of-fit tests29. Based on evaluation criteria including the chi-squared (χ2) test, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, Cramer–von Mises test, and PPCC, the Gumbel distribution was selected as the most suitable model. This approach follows the methodology presented in the national guideline “Improvement and Supplementation of Probable Rainfall Maps” by the Ministry of Land, Transport and Maritime Affairs30.

It is a fact that there is no measurement data available to directly predict flood depth based on actual rainfall. Therefore, to predict flood depth using the SVM model, the probability of precipitation according to the return period was estimated as shown in Table 2.

The temporal rainfall distribution was determined using the 3rd quartile of the Huff method, which divides a storm event into four quartiles based on the timing of peak rainfall. The method expresses cumulative rainfall and time in dimensionless ratios, allowing generalization across storm durations. The 3rd quartile reflects mid-duration peak rainfall, which is representative of typical urban storm events.

To construct the dimensionless cumulative rainfall curve, two ratios are defined. The dimensionless cumulative time at an arbitrary time step \(T(i)\) is given as:

where \(T(i)\) denotes the elapsed time from the beginning of the rainfall to the \(i\)-th interval, and \(TO\) is the total rainfall duration.

Likewise, the dimensionless cumulative rainfall is calculated as:

where \(R(i)\) is the cumulative rainfall up to time \(T(i)\), and \(T(O)\) is the total rainfall over the entire storm event. These non-dimensional expressions enable the application of the Huff method to diverse design scenarios and support the generation of realistic synthetic hyetographs.

The estimated precipitation was used as input data and applied to SWMM, a runoff analysis model. As a result, overflow occurred in 22 manholes at the 30-year return period, 25 manholes at the 50-year return period, and 31 manholes at the 100-year return period. Finally, based on the results of the runoff analysis, the critical manhole points that most affect the flood depth are shown in Table 3.

After applying the results of the runoff analysis as the boundary condition of the 2D flood model, the flood analysis was performed. As a result, it was confirmed that flooding occurred around Gangnam Station and the intersection of Jinheung Apartment, which is a regularly flooded area, as seen in the previous flooding patterns based on actual rainfall in Fig. 10.

Flood for probabilistic precipitation, map generated in the ArcGIS 10.1 (ESRI, https://www.esri.com/).

SVM model application. In this study, the prediction model of the SVM model was used. The parameters were calculated through pattern search, and flood depth was predicted based on precipitation and manhole overflow using the training process and verification.

As a result of the 2D inundation analysis, the intersection of Jinheung Apartment in Gangnam, where the inundation depth was the largest, was selected as the target basin. The results of the 2D inundation analysis with a return period of 100 years were used to predict the depth of flooding. To establish the basic data for the SVM model, rainfall durations ranging from 1 to 5 hours, corresponding to the 100-year return period of precipitation, were selected. Additionally, the amount of manhole overflow based on rainfall time was converted into data through runoff analysis. Subsequently, flood depth data at the intersection of the Jinheung Apartment were calculated through 2D flood analysis, and the results were converted into usable data. Compared to the 2D hydraulic model, which required approximately 3 hours to complete a single simulation including pre-processing and post-processing, the trained SVM model was able to predict flood depth at the target location within a few seconds. This significant reduction in computation time demonstrates the practical efficiency of the proposed framework for near real-time flood forecasting in urban areas. Finally, the estimated data were applied to the SVM model, and the training and verification process was repeated, enabling prediction of flood depth at intersection of the Jinheung Apartment over time.

In this study, the term “real-time prediction” refers to the rapid simulation process of a pre-trained SVM model, which generates flood depth predictions within seconds. Unlike online learning models that require continuous updating and may introduce latency, the pre-trained architecture is intentionally designed for fast and stable deployment in real-time forecasting systems. This approach ensures consistent performance and minimal computation time when responding to imminent rainfall events in urban flood-prone areas.

Since detailed observed flood depth time-series data were not available for the study area, the 1D–2D hydraulic model (SWMM–FLO-2D) was not used as a real-time prediction tool, but instead to generate physically consistent datasets for training the machine learning model.

The training input and verification input data were configured to predict the flood depth. The input variables of the SVM model are cumulative rainfall and cumulative overflow, while the output variable is flood depth. The training dataset was generated from 1-hour to 5-hour rainfall scenarios based on the Huff 100-year return period distribution, recorded at 1-minute intervals. As a result, 190 time-step samples were used for training, and an additional 48 time-step samples were used for model validation. Each time-step sample is structured as a one-dimensional vector, where the cumulative rainfall and overflow serve as input features and the corresponding flood depth serves as the target output.

Firstly, the training data, which includes cumulative precipitation, shows the precipitation duration ranging from 1 to 5 hours according to the 100-year return period in Fig. 11. The amount of overflow at each hour for the manhole at point 3, which significantly influences the intersection of Jinheung Apartment, was calculated through the runoff analysis, and presented in Fig. 12. Finally, through the 2D inundation analysis, the time-dependent inundation depth at the intersection of Jinheung Apartment was computed in Fig. 13. In other words, as can be seen in Figs. 11, 12 and 13, the training data used are hourly rainfall, manhole overflow, and flood depth data for 1 hour, 2 hours, 4 hours, and 5 hours.

Second, for the verification data, the cumulative precipitation for a 3 h rainfall duration according to the 100-year return period was selected. Additionally, the overflow and flood depth of the manhole at point 3, which significantly influences the intersection of Jinheung Apartment, were also selected in Fig. 14.

Finally, in the SVM model, the cumulative precipitation and cumulative overflow for each hour of precipitation duration from 1 to 5 hours were applied as training data, and the flood depth was repeatedly learned in Fig. 15. Subsequently, the cumulative rainfall and cumulative overflow for each hour of the 3 h rainfall duration in the target basin were input as predicted data, and the flood depth in the target basin was predicted and verified over time in Fig. 16. In Figs. 15 and 16, the X-axis represents time, and the Y-axis represents flood.

The results of applying the SVM model showed a similar pattern to the results of the 2D inundation analysis in Fig. 15. Additionally, the predictions of flood depth over time in the target watershed were also similar.

In the results of flood depth prediction over time in Fig. 16, some fluctuations in the measured values occurred at the end. These fluctuations were attributed to the influence of topography, such as buildings and roads. To verify the SVM prediction results from Fig. 17. The average flood depth of the observed values for that segment was 1.87 m, and the average flood depth of the predicted result was 1.86 m, confirming a slight error of 1 cm. Fig. 17a presents the results before calibration, while (b) shows the results after calibration.

Review of the suitability of the SVM model. To assess the suitability of the SVM prediction model, Coefficient of Determination (R2), Nash and Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE), % Difference, and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) analyses were performed. The coefficient of determination ranges from 0.0 to 1.0, with higher values indicating a stronger correlation between the measured and simulated values. NSE value approaches 1 when the simulated value is a perfect fit and approaches 0 when the simulated value is merely the average of the measured values. % difference is a statistical value used to compare actual and simulated values mathematically and indicates the reliability of repeated measurements where identical results are expected in Table 4.

where, \({P}_{i}\): Simulated value; \({O}_{i}\): Measured value; \(n\): Number of data; \({O}_{Ai}\): Average of Measured value

As a result of error analysis on the training results, the coefficient of determination was 0.997, the NSE was 0.997, and the % Difference was 0.195, indicating that the confidence interval and acceptable range were very good. The RMSE was 0.044, suggesting the model accurately reflected the measured and simulated values in Table 5.

Regarding the verification results, the coefficient of determination was 0.988, the NSE was 0.987, and the % Difference was 1.080, indicating that the confidence interval and acceptable range were still very good. The RMSE was 0.098, validating the appropriateness of the actual measured values and predicted results of the SVM model in Table 6.

Conclusion

This study developed a flood forecasting framework that integrates a physically based 1D–2D flood simulation model with a SVM to enable rapid and accurate real-time prediction of flood depth in urban areas.

Using observed precipitation data and a validated SWMM–FLO-2D model, various rainfall scenarios were simulated to generate training data. The SVM model was then trained to predict hourly flood depth at critical flood-prone locations. The developed model successfully reproduced flood behavior with high accuracy (R2 = 0.988, NSE = 0.987), achieving a mean absolute error of less than 1 cm, while significantly reducing computational time to within seconds.

The developed SVM-based model provides a balance between physical accuracy and real-time responsiveness. Its light-weight computation allows for flood depth prediction within seconds, and it is structurally ready for integration with real-time rainfall observation systems. This approach not only enhances predictive performance but also ensures physical interpretability, which is often lacking in black-box data-driven models. Importantly, the model structure allows for seamless integration with real-time rainfall monitoring systems and can be deployed in early warning frameworks for urban flood risk management.

Although the current SVM model operates in an offline training mode, it is designed to accommodate online data updates, supporting continuous learning and long-term adaptability. These findings demonstrate the feasibility and practical value of the proposed model for flood response systems, especially in data-scarce urban environments where rapid decision-making is critical.

Data availability

The data used in this study are included in the submitted manuscript. For any further inquiries, please contact the corresponding author.

References

National Institute of Meteorological Sciences (2020) Global Climate Change Forecast Report; South Korea.

Nuclear Energy Institute (2015) NEI 15-05, Warning Time for Local Intense Precipitation Events, Rev. 6. Nuclear Energy Institute, Washington, DC. Available at:

Yu, C. S. Heavy rain damage on september 21, 2010. Water for Future 44(1), 67–72 (2011).

Kim, H. J. Lessons from heavy rain in the metropolitan area in July 2011. Water Future 44(10), 56–60 (2011).

Kim, J. T. Typhoon chaba and super typhoon prospects on the korean peninsula. Water Future 49(10), 46–51 (2016).

Tabari, H. Extreme value analysis dilemma for climate change impact assessment on global flood and extreme precipitation. J. Hydrol. 593, 125932 (2021).

Xie, X., Tian, Y. & Wei, G. Deduction of sudden rainstorm scenarios: integrating decisio’ makers’ emotions, dynamic Bayesian network and DS evidence theory. Natural Hazards. 116(3), 2935 (2022).

Xie, X., Huang, L., Marson, S. M. & Wei, G. Emergency response process for sudden rainstorm and flooding: Scenario deduction and Bayesian network analysis using evidence theory and knowledge meta-theory. Natural Hazard 117(3), 3307–3329 (2023).

Chen, L., Yan, Z., Li, Q. & Xu, Y. Flash flood risk assessment and driving factors: A case study of the Yantanxi River Basin, Southeastern China. Int. J. Disast. Risk Sci. 13(2), 291–304 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Chen, Yu., Liang, F. & Liu, H. Assessment of future flash flood inundations in coastal regions under climate change scenarios—A case study of Hadahe River basin in northeastern China. Sci. Total Environ. 693, 133550 (2019).

Kang KS, Heo JH (2002) A comparative study of daily inflow prediction methods on major multi-purpose dams in HAN river Basin. In: Proceedings of the KSCE Conference, pp 1375-1378.

Lee JD, Park JH, Kim JK, Lee JH, Lee YH, Kim DS, Park KH (2011) Development of heavy rain situation prediction method using SVM. In: proceedings of the KMS Conference, pp 96-97.

Kim, H. I., Han, K. Y. & Lee, J. Y. Prediction of urban flood extent by LSTM model and logistic regression. J. Korean Soc. Civ. Eng. 40(3), 273–283 (2020).

Wang, H. W., Lin, G. F., Hsu, C. T., Wu, S. J. & Tfwala, S. S. Long-term temporal flood predictions made using convolutional neural networks. Water 14(24), 4134. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14244134 (2022).

Situ, Z. et al. Improving urban flood prediction using LSTM-DeepLabv3+ and Bayesian optimization with spatiotemporal feature fusion. J. Hydrol 630, 130743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.130743 (2024).

Yu, P. S., Chen, S. T. & Chang, I. F. Support vector regression for real-time flood stage forecasting. J. Hydrol 328, 704–716 (2006).

Han, D., Chan, L. & Zhu, N. Flood forecasting using support vector machines. J. Hydrol 9, 267–276 (2007).

Lin, G. F., Chen, G. R., Huang, P. Y. & Chou, Y. C. Support vector machine-based models for hourly reservoir inflow forecasting during typhoon-warning periods. J. Hydrol 372, 17–29 (2009).

Mosavi, A., Ozturk, P. & Chau, K. W. Flood prediction using machine learning models: Literature review. Water 10(11), 1536 (2018).

Nong, X. et al. Prediction modelling framework comparative analysis of dissolved oxygen concentration variations using support vector regression coupled with multiple feature engineering and optimization methods: A case study in China. Ecolog. Indicat. 146, 109845 (2023).

Wu, J. et al. Flash flood forecasting using support vector regression model in a small mountainous catchment. Water 11(7), 1327 (2019).

Anaraki, M. V., Farzin, S., Mousavi, S. F. & Karami, H. Uncertainty analysis of climate change impacts on flood frequency by using hybrid machine learning methods. Water Res. Manag. 35, 199–223 (2021).

Abu, I. et al. Flood susceptibility modelling using advanced ensemble machine learning models. Geosci. Front. 12(3), 101075 (2021).

Dhara, S., Dang, T. & Parial, K. Lu XX (2020) Accounting for uncertainty and reconstruction of flooding patterns based on multi-satellite imagery and support vector machine technique: A case study of can tho city. Vietnam. Water. 12(6), 1543 (2020).

Vapnik V, Guyon I, Hastie T (1995) Support vector machines (Vol. 20).

Burges, C. J. C. A tutorial on support vector machines for pattern recognition. In data mining and knowledge discovery. Springer 2, 121–167 (1998).

Cho, W. H., Han, K. Y., Hwang, T. J. & Son, A. L. 2-D inundation analysis in urban area considering building and road. J. Korean Soc. Hazard Mitigat. 11(5), 159–168 (2011).

Son, A. L., Kim, B. & Han, K. Y. A study on prediction of inundation area considering road network in urban area. J. Korean Soc. Civ. Eng 35(2), 307–318 (2015).

Kim BJ (2016) Urban Inundation Analysis Using Deteministic Approach and Data-Driven Model. Master’s thesis, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Republic of Korea.

Ministry of Land, Transport and Maritime Affairs (2011) Study on the improvement and supplementation of probable rainfall maps. Prepared by MLTM, Water Resources Policy Division, Republic of Korea.

Donigan Jr. AS (2000) HSPF training workshop handbook and CD. Lecture #19. Calibration and verification issues, Slide #L 19-22. Presented at the EPA Headquarters, Washington Information Center, 10-14 January 2000. Prepared for U.S. EPA, Office of Water, Office of Science and Technology, Washington, DC.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Science and ICT), and by Korea Environment Industry & Technology Institute (KEITI) through R&D Program for Innovative Flood Protection Technologies against Climate Crisis Project funded by Korea Ministry of Environment (MOE) (No. RS-2022-00144493, 2022003470001).

Funding

National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (No. RS-2022-00144493) and Korea Environment Industry & Technology Institute (KEITI) through R&D Program funded by Korea Ministry of Environment (MOE) (2022003470001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and Methodology, B.K; validation, B.J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, B.J.K., M.K., J.H.Y.; writing—review and editing, B.J.K. and B.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, BJ., Kim, M., Yoo, J. et al. Rapid simulation for real-time flood depth prediction using support vector machine. Sci Rep 15, 31818 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17090-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17090-2