Abstract

Exposure to and consequent bioaccumulation of toxic hydrocarbons, particularly polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), are a significant concern for ocean health. This study reports the distribution of parental and alkylated PAHs in the liver and muscle tissues of sea turtles found stranded on locations in the NE coast affected by the largest oil spill in Brazil, which occurred in 2019. The field trips recovered nineteen animals along the shores of Pernambuco, Rio Grande do Norte, and Ceará between 2020 and 2021. Chelonia mydas represented 79% of all specimens. PAH determination in liver and muscle tissues involves extraction using a Soxhlet apparatus, purification by permeation chromatography, and subsequent analysis by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC–MS). Twenty-six of 37 individual PAHs were identified, including parent and alkylated compounds, totaling 67.87 ± 54.22 ng g−1 (ww) in muscle and 50.19 ± 42.74 ng g−1 (ww) in liver. Pyrene, phenanthrene, and their respective alkylated homologs were the most abundant PAHs. Tissues showed similar PAH concentrations, but pyrenes were much more abundant in muscle than in the liver. An overall prevalence of light (LMW; 2–3 rings) over heavy (HMW; 4–6 rings) PAHs was verified, particularly in liver samples. The 16 priority PAHs accounted for between 60 and 70% of the total PAHs in both tissues. The findings revealed relatively high contamination, with evidence of exposure to the oil spill in the region and other anthropogenic sources. More importantly, the results can be considered as short- to medium-term exposure indicators following the oil spill in the study areas, and it is essential to monitor the evolution of turtle exposure in the medium- to long-term on the NE coast of Brazil.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are contaminants of significant environmental concern, as they are ubiquitous, are produced by various anthropogenic sources, are persistent, and exhibit high mobility1. They are also toxic and display a high bioaccumulation tendency, particularly in invertebrates2. Furthermore, they are potentially carcinogenic when bioaccumulated and biotransformed by marine animals3,4,5 with the ability to modify the DNA structure6, leading to tumor development and potentially death7.

PAHs originate from natural sources, such as plant biogenesis, shale erosion, and natural fires. However, their primary sources are anthropogenic activities associated with producing and consuming fossil energy resources8. Anthropogenic PAH sources can be categorized as petrogenic when derived directly from petroleum and petroleum-derived products or pyrolytic when derived from fossil fuels and/or biomass burning or from various industrial processes conducted at high temperatures9. The diversity of PAH sources produces volatile and semi-volatile aromatic compounds. Monoaromatic PAHs, such as benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and o,m,p-xylenes, or BTEX, are abundant in petroleum and derivatives but are highly volatile and exhibit no bioaccumulation propensity. On the other hand, the semi-volatile fraction includes PAHs containing 2 to 6 aromatic rings, which are persistent and bioaccumulative. Parental and alkylated compounds are predominant in petroleum in the lighter range (2–4 rings). In contrast, pyrogenic compounds generally contain > 4 rings in their structures and no alkyl branch10.

Despite chronic contamination by anthropogenic hydrocarbons recorded throughout the biota of coastal and oceanic systems worldwide11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19 among many others, the effects of PAH biota contamination, including animal health and food insecurity effects, are usually put in the spotlight following significant oil spills13,20,21,22,23,24,25.

The trophic specificities of sea turtle species serve as the primary entry point for toxic substance contamination26. This occurs because certain detrimental food items can accumulate these compounds more effectively, promoting biomagnification27. During their hatchling stage, sea turtles generally inhabit pelagic environments, where they associate with floating clusters and maintain an omnivorous diet28. As they transition into juveniles, they develop specific dietary habits and begin migratory patterns, which significantly increase their exposure to contaminants6,29.

Additionally, sea turtles exhibit migratory reproductive patterns, traveling between their feeding and nesting grounds over a period of one to four years, depending on their species30. This behavior increases their dispersive potential and, as a result, raises their risk of encountering contaminated environments29,31. Therefore, sea turtles are highly vulnerable to environmental contamination due to their long lifespans and multiple ecological roles32. The release of oil, petroleum products, and industrial waste into the ocean threatens their development, reproduction, and feeding habitats. These pollutants can spread through the water, settle in sediments, and contaminate nesting areas, ultimately affecting their food sources, which may lead to bioaccumulation and increased exposure to harmful PAHs33,34,35,36.

The green turtle (Chelonia mydas) primarily consumes algae and marine phanerogams in its juvenile and adult phase30,31,32. Consequently, it often inhabits coastal regions, exposing it to human activities on land and the disposal of toxic waste33,34. The loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) lives in pelagic habitats as a juvenile, following a rather unvaried diet of fish, cnidarians, and algae, among others. When it matures, it migrates to the neritic zone, where it predominantly feeds on benthic organisms35, making it more susceptible to human impact29. The olive ridley turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) lives in neritic or oceanic surface waters during its juvenile stage and has an omnivorous diet36. As it transitions to adulthood, it frequents both pelagic and neritic areas, ranging from deep to shallow waters37,38, consuming mainly cnidarians, fish, and mollusks, among others39,40. While this species finds it tougher to forage along the coast, it remains vulnerable to pollution, as waste can be carried over vast distances by ocean currents41.

Additionally, sea turtles exhibit migratory reproductive habits, traveling between their feeding and nesting grounds over one to four years, depending on their species42. This behavior enhances their dispersive potential and, as a result, raises their risk of encountering contaminated environments29,43.

Therefore, sea turtles are highly susceptible to environmental contamination due to their long lifecycles and various ecological roles44. The releases of oil, oil products, and industrial waste into the ocean threaten their development, reproduction, and feeding habitats. These contaminants can spread through the water, settle in sediments, and pollute nesting areas, ultimately affecting their food source, which may result in bioaccumulation and increased exposure to harmful PAHs45,46,47,48.

The largest oil spill recorded on the Brazilian coast affected over 3000 km of shoreline from September 2019 to January 202021. The Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) reported that turtles were the most impacted, with 105 animals covered in oil during the cleanup49. This study examined PAH compounds from 2 to 6 fused rings, including parent and alkylated homologs, in the liver and muscle tissues of sea turtles that stranded in Northeastern Brazil. The aim was to investigate the accumulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in liver and muscle tissues of sea turtles stranded along the Northeastern Brazilian coast after the 2019 oil spill, to identify potential sources of contamination, and to assess the toxicological implications for these sentinel marine species. The findings provide insight into the environmental consequences of oil pollution and support conservation efforts for vulnerable sea turtle populations affected by large-scale coastal contamination.

Material and methods

Study area and sample collection

The study was conducted along the northeastern coast of Brazil, which represents the most significant section of the Brazilian coastline, measuring 3317 km. This area stretches between the Bay of São Marcos in Maranhão and the Bay of Todos os Santos in Bahia50. The northeastern continental shelf is categorized into three segments: the inner shelf, the middle shelf, and the outer shelf51. A gentle topography, the presence of reefs, and influences from nearby channels and undulations characterize the inner shelf. In contrast, the middle shelf exhibits more varied elevations, while the outer shelf primarily features flat terrain that gradually slopes as it approaches the break52. The water masses in this region originate from the east and are carried by the South Equatorial Current, which divides into two branches when it reaches the Paraiba’s coast, forming the Brazil Current. In the northeastern coastal zone, the Brazil Current has an average temperature of 27 ºC and salinity of 37%53. Data collection took place in the states of Pernambuco, Rio Grande do Norte, and Ceará, with a focus on documenting strandings along the coast.

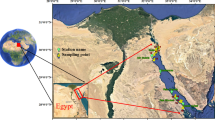

Nineteen sea turtle specimens were collected in 2020 and 2021 (Table S1-Supplementary Material). Sampling was carried out based on the strandings records from these states at the locations indicated in Fig. 1.

Map of sea turtle specimens stranding sites. Created using QGIS version 3.34.15, https://qgis.org/download/.

Turtle carcass conditions were analyzed prior to the samplings, and only specimens found in decomposition stages D1, D2 or D354 were used. The samplings carried out on the coast of Pernambuco were supported by the NGO ECOASSOCIADOS, and the specimens were transported to the Herpetological and Paleoherpetological Studies Laboratory at the Federal Rural University of Pernambuco (LEHP). The specimens from Rio Grande do Norte and Ceará were sampled and processed with the aid of the Center for Environmental Studies and Monitoring of the Cetaceans of Costa Branca Project (PCCB) team.

Laboratory procedures

The individuals were collected and sent to necropsy immediately after the stranding, followed by the recording of death, to avoid tissue decomposition. Biometric measurements, i.e., carapace curvature length (CCL) and carapace curvature width (CCW), were taken to identify sea turtle developmental stages55.

Necropsies were then performed to remove livers and skeletal muscle tissues, according to specific turtle techniques56, in a previously sanitized laboratory, using sterile materials or materials previously sanitized with 70% alcohol and filtered deionized water. No plastic equipment was used to handle or deposit the samples. After necropsy, tissue samples were stored in sealed glass containers and kept at –20ºC until chemical analysis in the Marine and Environmental Studies Laboratory (LabMAM) at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio).

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon determinations

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons were analyzed following the protocol outlined by Pinheiro et al. (2021)45. In short, aliquots of 0.25 g (wet weight; precision ± 0.001 g) of sea turtle liver and muscle tissue samples were chemically dried using approximately 10 g of decontaminated sodium sulfate (heated at 480 °C overnight), and 500 ng of p-terphenyl-d14 were added as a surrogate. Extraction of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons followed the EPA Method 3540C, which used a Soxhlet apparatus containing 80 mL of dichloromethane for 8 h. The crude extract volume was reduced to about 1 mL using a rotary evaporator for subsequent purification and isolation. Initially, the extract was eluted with 80 mL of a 1:1 (v:v) mixture of n-hexane and dichloromethane through a glass column (25 cm high × 1.5 cm internal diameter) filled with 8 g of silica gel (5% deactivated), over 16 g of alumina (5% deactivated), and 1 g of anhydrous sodium sulfate. The second purification involved a gel permeation exclusion column connected to a high-performance liquid chromatograph, with PAHs recovered after 30–40 min of each run, monitored via a UV/Vis detector.

The purified extracts were diluted to 1 mL and used 500 ng of naphthalene-d8, acenaphthene-d10, phenanthrene-d10, chrysene-d12, and perylene-d12 as internal quantification standards. The PAH determinations were conducted using the EPA 8270D method, based on the GC–MS technique. The equipment calibration considered a 12-point calibration curve (0,50; 1,0; 2,0; 5,0; 10; 20; 50; 100; 200; 400; 1000 and 2000 ng mL-1) comprising a solution containing the 16 PAHs controlled by the method (naphthalene, acenaphthylene, acenaphthene, fluorene, phenanthrene, anthracene, fluoranthene, pyrene, benzo(a)anthracene, chrysene, benzo(b)fluoranthene, benzo(k)fluoranthene, benzo(a)pyrene, indeno(1,2,3-c,d)pyrene, dibenzo(a,h)anthracene, benzo(ghi)perylene), dibenzothiophene, perylene and benzo(e)pyrene. The method also includes the following alkylated compounds: 1-methylnaphthalene, 2-methylnaphthalene, C2 naphthalenes, C3 naphthalenes, C4 naphthalenes, C1 fluorenes, C2 fluorenes, C3 fluorenes, C1 dibenzothiophenes, C2 dibenzothiophenes, C3 dibenzothiophenes, C1(phenanthrenes + anthracenes): C2(phenanthrenes + anthracenes), C3(phenanthrenes + anthracenes), C4(phenanthrenes + anthracenes), C1 pyrenes, C2 pyrenes, C1 chrysenes, and C2 chrysenes. The alkylated compounds were identified based on the curves of their corresponding parent compounds. A total of 37 parental and alkylated PAHs were identified and quantified. Quality of analysis and quality control (QA/QC) criteria consisted of analyzing laboratory blanks, surrogate standard recoveries (between 60 and 120%), precision better than 20%, and method accuracy through tissue doping with a mixture of PAH standards.

Statistical analyses

Data normality in the PAH distribution was evaluated by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov method using the Stat 3.0 program. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between PAH concentrations and analyzed tissues were considered using Student’s t (parametric) and Mann–Whitney (nonparametric) statistical tests. Hierarchical cluster analysis involved using Euclidean distances and the Ward method on a normalized data matrix. The total sample concentrations underwent normalization and Z-score standardization. R Studio draws the data visualization graphs.

Results

Sea turtle species and general characteristics

A total of 19 sea turtle specimens found stranded between January 2020 and August 2021 were collected, 12 along the coastal strip of Pernambuco, three along the northern coast of Rio Grande do Norte, and four on the southern coast of Ceará. Twelve were identified as Chelonia mydas, four as Lepidochelys olivacea, and three as Caretta caretta (Table S1-Supplementary Material). The mean CCL and CCW values and standard deviations for each of the sampled species are depicted in Table S2-Supplementary Material.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon concentrations in sea turtle liver and muscle tissues

Table 1 presents the concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the muscle and liver of all sampled sea turtles, showing the means and minimum and maximum values. Detailed values for each species are displayed in Table S2–Supplementary Material. The table includes the total amounts of identified PAHs, distinguishing between low molecular weight PAHs (LMW PAHs, parental compounds with 2–3 rings) and high molecular weight PAHs (HMW PAHs, parental compounds with 4–6 rings) as well as their ratio (LMW/HMW).

Fourteen out of the sixteen EPA priority PAHs were detected in at least one sample, namely naphthalene (N), acenaphthene (ACF), acenaphthylene (ACE), fluorene (F), anthracene (A), phenanthrene (Ph), fluoranthene (Fl), pyrene (Py), benzo(a)anthracene (BaA), chrysene (Ch), benzo(b)fluoranthene (BbFl), benzo(k)fluoranthene (BkFl), benzo(a)pyrene (BaPy) and benzo(ghi)perylene (BghiPe). In addition, twelve alkylated PAHs were detected: C1-naphthalene (C1N), C2-naphthalene (C2N), C3-naphthalene (C3N), C1-fluorene (C1F), C2-fluorene (C2F), C3-fluorene (C3F), C1-phenanthrene-anthracene (C1Ph), C2-phenanthrene-anthracene ( C2Ph), C3-phenanthrene-anthracene (C3Ph), C1-pyrene (C1Py), C2-pyrene (C2Py) and benzo(e)pyrene (BePy).

The 16 priority PAHs and the total of 37 PAHs were more concentrated in muscle (∑16PAHs = 48.20 ± 55.71 ng g-1; ∑37PAHs = 67.87 ± 54.22 ng g-1) compared to the liver (∑16PAH = 27.04 ± 18.71 ng g-1; ∑37PAHs = 50.19 ± 42.74 ng g-1). The 37 main PAHs represented 63.35 ± 20.93% of the total PAHs in muscle tissue and 68 ± 25.67% in liver tissue. In addition to differences in concentrations, the LMH/HMH ratio was lower in the muscle (1.02 ± 0.98) compared to the liver (2.55 ± 3.65 ng g-1), with the percentage of alkylated PAHs of 18.8 ± 19.4% in the muscle and 16.1 ± 22.8% in the liver.

The highest PAH concentration in the muscle was for Py (22.6 ± 45.8 ng g-1), followed by Ph (7.46 ± 5.79 ng g-1). On the other hand, Ph was the most predominant compound in the liver (Ph = 7.89 ± 5.67 ng g-1), followed by BePy (7.02 ± 24.1 ng g-1) and Fl (6.45 ± 11.6 ng g-1). In addition, Py and Ph were also the most frequently detected in the analyzed samples, present in 90 and 84.8% of all samples, respectively (Fig. 2).

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon distribution among sea turtle species and sampling sites, and biometric measurement classes

No significant differences (p < 0.05) between liver and muscle PAH concentrations were observed in the sea turtle specimens sampled from PE (p = 0.673) and CE (p = 0.286). In addition, no differences between liver (p = 0.46) and muscle (p = 0.90) tissues were noted when comparing the same sampling regions. The comparison between specimens from RN and other states was not performed due to the low sample size (N = 2) for each tissue (Fig. 3). Furthermore, no significant differences were observed when comparing the liver and muscle samples (p = 0.2014) (Fig. 4). This statistical analysis was not conducted separately for each species due to the limited number of Caretta caretta and Lepidochelys olivacea individuals; instead, data were combined across all specimens analyzed.

Box plots representing the relationship between sea turtle sampling sites (x-axis), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon sums (y-axis), and analyzed tissue (box plots). Horizontal line – median; Whiskers – minimum and maximum values; ∑PAHs (ng g-1) – the sum of the 37 PAHs identified in the samples; CE – Ceará; PE – Pernambuco; RN – Rio Grande do Norte.

Regarding biometric measurements, the Student’s t-test showed no difference between PAH concentrations in the liver and muscle with CCL (p = 0.6933) or CCW (p = 0.8924) measurement (see detailed data in Supplementary Material). This specific statistical analysis of PAH tissue retention was conducted only for Chelonia mydas, as most samples were from this species, and there were few specimens of Caretta caretta and Lepidochelys olivacea.

Multivariate statistical analysis

The cluster analysis identified three groups based on accumulation patterns (Fig. 5). Group 1 included 10 samples (six from CE and four from RN) with a strong presence of pyrene (Py) and fluorene (Fl). Group 2 contained five samples (two from CE and three from PE), showing greater diversity in PAHs. It featured high concentrations of pyrene (Py) and phenanthrene (Ph), along with their alkylated compounds, and a “bell” distribution of naphthalene (N) and alkylated homologs, with C3N being the most abundant. Group 3 comprised 15 samples —14 from PE and one from CE—and was characterized by a strong influence of phenanthrene (Ph), C1-phenanthrene (C1Ph), C1-fluorene (C1F), and naphthalene with alkylated homologs arranged in decreasing order: C0, C1, C2, and C3. While Group 3 contained some Pyrene, the concentrations were lower than in the other groups. Details on Fig. 6.

Discussion

The analysis revealed PAH contamination in all sampled sea turtle specimens (detailed data as Supplementary Material). In muscle tissue, pyrene, phenanthrene, and benzo(b)fluoranthene were most prevalent, while in the liver, phenanthrene, benzo(e)pyrene, and fluoranthene were dominant. Previous studies by Rossi et al.57 and Yaghmour et al.58 have documented similar findings in liver and muscle samples from sea turtles in Brazil and the Gulf of Oman, respectively (see Table 2).

The alkylated-to-total PAHs ratio was low, representing 33.5 ± 21.2% in the muscle and 25.9 ± 19.2% in the liver. These values indicate a pyrogenic contamination profile59, although some samples exhibited alkylated PAH concentrations exceeding 50% of those of the parental compounds. Rossi et al.57 and Ylitalo et al.47 quantified the frequency of alkylated homologs in sea turtle samples. It is common for PAHalk to be more concentrated in organisms that have been in contact with petrogenic residues, as these are essential petroleum components60,61. Alkylated homologs are also more resistant to degradation and lipophilic, facilitating their accumulation in fatty tissues, such as the liver62,63.

Research on the comparative analysis of alkylated and parental polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in marine tetrapods, particularly sea turtles, is limited. For instance, Waszak et al. (2021) conducted a study on seabird tissue samples and found that 60 to 70% of the PAHs present were alkylated, indicating contamination from petroleum sources. Additionally, some studies involving invertebrates have shown that elevated concentrations of alkylated PAHs are associated with increased toxicity64,65.

Although there is overlap between the area assessed in this study and that studied by Rossi et al.57, the concentrations reported by those authors are at least two orders of magnitude higher for the total polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (∑PAHs), measuring 1154 ± 2232 ng g-1 (as shown in Table 2). Rossi et al.57 collected their samples between 2015 and 2018, before the 2019 oil spill in Northeast Brazil. While their values indicate contamination by anthropogenic hydrocarbons in the study area prior to the oil spill, they are not comparable to those presented in other studies in Table 2. The reasons for the considerably increased concentrations observed in their samples remain unclear. One potential explanation is the limited number of samples collected each year (only five), which may have introduced bias in the data distribution. Additionally, the prevalence of naphthalene and its alkylated homologs in their samples, which were absent in ours, suggests exposure to lighter PAHs. These discrepancies in the occurrence of PAHs in turtles stranded on Northeast Brazilian beaches underscore the importance of increasing the frequency of sampling and evaluating organic contamination in these animals, including other contaminants.

In addition to the elevated PAH concentrations reported by Rossi et al.57, those authors also differentiated specimens presenting tumors caused by the Chelonid alphaherpesvirus 5 (ChHV5), the causative agent of fibropapillomatosis (FP) in sea turtles, identifying a correlation between the presence of tumors and benzo(b)fluoranthene, indene(1,2,3-c,d)pyrene and C1–C3-dibenzothiophene concentrations. Fibropapillomatosis is an immunosuppressive disease that affects marine testudines, with evidence that occurrence is higher in individuals exposed to contaminants46,57,67. Herein, the presence/absence of fibropapillomatosis was not linked to PAH concentrations, as the number of animals with tumors was not relevant. However, it is noteworthy that IPy, C1-DBT, and C3-DBT, related to the presence of fibropapillomatosis in Chelonia mydas by Rossi et al.57, were below the limit of quantification for the present study. Vilca et al.46 identified higher PAH concentrations in the liver of Chelonia mydas specimens presenting fibropapillomas, with concentrations lower than those reported in this assessment (Table 2). On the other hand, Arienzo et al.66 did not consider the presence of FP but indicated results at least twice as high as those reported herein (Table 2). Thus, it appears that further research is necessary to establish a correlation between PAH concentrations and the occurrence of fibropapillomatosis in turtles stranded on Brazilian beaches.

No significant difference (p = 0.2014) was observed between PAH concentrations and analyzed tissues. However, muscle tissue presented slightly higher concentrations of individual PAHs (∑37PAH = 67.87 ± 54.22 ng g-1), priority PAHs (∑16PAH = 48.20 ± 55.71 ng g-1), and high molecular weight PAHs (∑HMW = 34.24 ± 50.64 ng g-1) when compared to the values found in the liver tissue. The concentrations of LMW PAHs, on the other hand, were similar between muscle and liver (∑LMW muscle = 13.9 ± 12.4 ng g-1; ∑LMW = 12.1 ± 10.3 ng g-1).

The relative fluoranthene levels in the liver were relevant for the LMW/HMW ratio in this tissue since fluoranthene was detected at much higher concentrations in this tissue than in the muscle (Flliver = 6.45 ± 11.6 ng g-1; Flmuscle = 2.75 ± 5.15 ng g-1). The liver is the primary organ for metabolizing PAHs68, although degradation efficiency is associated with molecular weight, where HMW compounds are more easily degraded than LMW ones9,16,69.

The findings reported by Yaghmour et al.58 indicated that the concentration of PAHs was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in the liver (∑PAHliver = 15.0 ± 5.00 ng g⁻1) compared to the muscle (∑PAHmuscle = 1.39 ± 0.85 ng g⁻1) of sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) sampled from the coast of the Gulf of Oman. This contrasts with the current results. Conversely, Kuzukiran et al.70 observed a slightly increased concentration of PAHs in the muscle (84.2 ± 21.3 ng g⁻1) compared to the liver (75.8 ± 28.5 ng g⁻1) of male Caretta caretta turtles, but the opposite was noted for female specimens of the same species. This trend may reflect individual physiological variations or those associated with the time of exposure and metabolization of the compounds; however, we also do not exclude any bias in data distribution caused by the relatively low number of turtles analyzed on Brazilian beaches, which highlights the need for further investigation.

The relative contributions of LMW PAHs such as naphthalene, phenanthrene, fluoranthene, and acenaphthylene in the analyzed samples indicate petrogenic contamination71. The presence of these compounds has also been identified in other studies investigating the presence of PAHs in biological samples from animals in Northeastern Brazil after the 2019 oil spill20,71, including a study concerning sea turtle feces72. Magalhães et al.20 determined PAHs in mollusks, crustaceans, and fish affected by the spill in Pernambuco, NE Brazil, identifying high concentrations of naphthalenes and alkylates, followed by pyrene, phenanthrene, and fluoranthene, while HMW PAHs were rare. Soares et al.71 investigated PAHs in the muscle tissue of fish and mollusks collected from the coast of the states of Alagoas and Sergipe in NE Brazil, reporting a predominance of fluoranthene, fluorene, and acenaphthylene in fish, and phenanthrene, fluoranthene, and naphthalene in mollusks. It is important to note that both studies aimed at a short-term analysis of the oil spill event in the Brazilian Northeast and comprised preliminary contamination assessments.

Furthermore, the analyzed biological matrices mentioned above focused on animals presenting limited, sometimes non-existent, locomotion (sessile animals). This characteristic, alongside the biology of the indicator biota, indicates different levels from those reported herein, as sea turtles are migratory animals and naturally accumulate substances due to their slow metabolism73. However, the qualitative similarity between the detected LMW PAH may indicate that the sample contamination verified herein is related to the Northeast Brazil oil spill event of 2019. Additionally, a study recently published by Feitosa et al.74 reported the presence of oily residues in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) of sea turtles necropsied following this oil spill, with the leading cause of death comprising topical inflammation caused by the GIT petroleum.

The HMW PAHs dispersed in oceans, known as pyrogenic, generally originate from incomplete combustion of fossil fuels75. However, some HMW PAHs can be directly associated with contamination by petroleum residues when concentrated in biological matrices10. Pyrene (four aromatic rings) is an example of HMW PAH associated with petroleum dumping in aquatic systems20. This compound was one of the most abundant detected in the animals analyzed herein. Despite high concentrations in the liver, Py values more than tripled in the muscle, possibly due to the lower metabolic capacity of this tissue9. The high concentrations of Py influence petrogenic contamination indicators, such as PAHalk to total PAHs ratio.

Previous studies have investigated PAH bioaccumulation in sea turtle tissues following oil spill accidents. For example, Ylitalo et al.47 analyzed PAH concentrations in livers from 2010 to 2011, following the Deep-Water Horizon (DWH) blowout, which is recognized as the largest oil spill event in the world. The authors investigated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in visibly oiled and non-oiled sea turtles, detecting naphthalene, phenanthrene, and their alkylated derivatives as the most predominant PAHs. Herein, all specimens were visibly not oiled, although our results exceeded the concentrations reported by Ylitalo47 for non-oiled specimens (Table 2). Camacho et al.76 monitored PAHs in the blood tissue of sea turtles (Caretta caretta) from the Canary Islands and reported elevated concentrations of naphthalene and phenanthrene over the years (2007–2010). Although no recent oil spills were documented at the time, the illegal circulation of oil tankers in the region was commonly reported, resulting in the uncontrolled dumping of oil waste into the sea77.

The cluster analysis separated all analyzed samples (muscle and liver) into three profiles (Fig. 5). Although quantitative distinctions in concentrations were observed between the three groups, no significant differences (p > 0.05) in the qualitative composition of PAHs were noted in general, which further supports the indication of petrogenic contamination due to the relevant presence of N, Ph, Fl, and Py10,20. The influence of some pyrogenic PAHs was observed in Groups 1 and 2, i.e., Ch, BaA, BePy, and BaPy. BbFl appears at high concentrations in all three groups. Although relevant for the obtained profiles, pyrogenic compounds were detected at much lower concentrations than petrogenic compounds. Furthermore, group 3, as defined by the cluster analysis (Fig. 6), encompassed most of the analyzed samples and was virtually unaffected by pyrogenic PAHs.

There are differences in the ecological profiles of the species, but these were not related to the sampling criteria used in this study. Importantly, no significant variation was observed in PAH retention between tissue types (muscle and liver), nor between sampling locations—whether at the state level (Pernambuco, Rio Grande do Norte, and Ceará) or among municipalities. This absence of difference could be due to the small number of samples collected from each location and the sampling process itself, which only identifies the stranding point rather than the actual site of death for the sea turtle.

Interspecific differences in PAH concentrations were not significant, likely because there were fewer individuals of Lepidochelys olivacea and Caretta caretta compared to Chelonia mydas. For future studies, it is advised to balance the number of specimens collected across species to enable more reliable comparisons.

Although no significant differences in PAH concentrations were observed in the present study, it is plausible that each species’ feeding ecology may influence contamination levels. While all species share similar diets during their early life stages28, their feeding habits diverge significantly as they reach juvenile and adult stages. Therefore, in addition to trophic level, the habitat occupied by individuals may also be closely linked to PAH bioaccumulation67.

The green turtle (Chelonia mydas), for example, mainly feeds on algae and marine phanerogams during its juvenile and adult stages68,69,70. As a result, it often inhabits coastal areas, which increases its exposure to human activities and land-based sources of toxic waste71,72. Caretta caretta lives in pelagic zones during its juvenile phase, feeding on fish, cnidarians, and algae. When it reaches maturity, it migrates to neritic zones and adopts a benthic diet73, making it more vulnerable to coastal pollution29. In contrast, the olive ridley turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) inhabits neritic or oceanic surface waters during its juvenile stage and has an omnivorous diet74. As adults, these turtles use both pelagic and neritic zones, ranging from shallow to deep waters75,76. While this species has a harder time foraging along the coast, it still remains vulnerable to pollution, as waste can be transported over long distances by ocean currents77.

Because few studies report PAH contamination in sea turtle tissues (as shown in Table 2), it is currently impossible to determine a clear contamination scenario based solely on ecological habits. However, species-specific trophic and habitat traits are likely important factors affecting PAH bioaccumulation and should be explored in future research.

It is also important to recognize that contamination levels are closely linked to other factors, including the type of exposure—such as duration, volume, density, residue composition, water column distribution, and contact method (like direct contact, ingestion, and inhalation)35,58,78,79. Additionally, the ontogenetic and physiological traits of the animals—such as the presence of enzymes that metabolize specific contaminants—should also be considered80.

The similarities observed in tissue samples, species, and collection sites—along with high levels of PAHs—also indicate significant contamination of sea turtles. Therefore, while identifying the exact sources of petrogenic and pyrogenic PAHs in sea turtles and other marine organisms remains difficult, conducting short- and medium-term investigative studies after events that cause substantial environmental impacts, such as the 2019 oil spill on the Northeast coast, is essential. This approach will generate valuable data that can serve as a baseline for long-term environmental monitoring.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the widespread presence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the liver and muscle tissues of three sea turtle species (Chelonia mydas, Caretta caretta, and Lepidochelys olivacea) found stranded after the 2019 oil spill that impacted Brazil’s northeastern coastline. A total of 37 PAHs, including both parent and alkylated forms, were analyzed, with pyrene and phenanthrene emerging as the most frequently detected compounds.

Although muscle tissues showed higher average PAH concentrations than liver tissues, the difference was not statistically significant (p < 0.05). This result contrasts with findings from previous studies, which often report higher hepatic accumulation, and suggests a more complex pattern of PAH distribution that warrants further investigation.

The chemical profile—dominated by low-molecular-weight compounds and a relatively low presence of alkylated PAHs—suggests a predominantly petrogenic source, in line with the characteristics of the 2019 spill. Furthermore, the lack of significant variation across species, collection sites, or individual measurements supports the interpretation of diffuse and widespread contamination, likely amplified by the turtles’ migratory behavior and the broad dispersal of pollutants in marine environments.

These findings underscore the critical role of sea turtles as sentinels of environmental health in tropical coastal ecosystems. The presence of toxic hydrocarbons in their tissues not only reflects the lingering impact of the oil spill but also signals ongoing exposure to pollution from multiple sources.

These findings highlight the importance of ongoing coastal monitoring, which has been vital in assessing marine wildlife health along Brazil’s northeastern coast. However, their limited coverage leaves key areas—such as some regions where turtles were found and nearby marine protected zones—unmonitored. To address these gaps, expanding efforts to track pollutant exposure, especially from persistent contaminants like PAHs, is essential. Broader, integrated programs will help guide conservation, strengthen policies, and protect vulnerable species like sea turtles and the coastal ecosystems supporting local communities.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sinaei, M., Araghi, P. E., Mashinchian, A., Fatemi, M. & Riazi, G. Application of biomarkers in mudskipper (Boleophthalmus dussumieri) to assess polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) pollution in coastal areas of the Persian Gulf. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 84, 311–318 (2012).

Ware, G. W. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology Vol. 143 (Springer-Verlag, 1995).

Lourenço, R. A. et al. Monitoring of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in a produced water disposal area in the Potiguar Basin, Brazilian equatorial margin. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23, 17113–17122 (2016).

Baird, C. & Cann, M. Química Ambiental (Bookman, 2011).

Manahan, S. E. Environmental Chemistry (Lewis Publisher, 2000).

Cocci, P. et al. Investigating the potential impact of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) on gene biomarker expression and global DNA methylation in loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) from the Adriatic Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 619–620, 49–57 (2018).

Ukaogo, I. J. C. P. O. Environmental Effects of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. J. Nat. Sci. Res. 5, (2015).

Ossai, I. C., Ahmed, A., Hassan, A. & Hamid, F. S. Remediation of soil and water contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbon: A review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 17, 100526 (2020).

Zychowski, G. V. & Godard-Codding, C. A. J. Reptilian exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and associated effects. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 36, 25–35 (2016).

Boehm, P. D., Pietari, J., Cook, L. L. & Saba, T. Improving rigor in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon source fingerprinting. Environ. Forensics 19, 172–184 (2018).

Lourenço, R. A., Lube, G. V., Jarcovis, R. D. L. M., da Silva, J. & de Souza, A. C. Navigating the PAH maze: Bioaccumulation, risks, and review of the quality guidelines in marine ecosystems with a spotlight on the Brazilian coastline. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 197, 115764 (2023).

Costa, G. K. A. et al. Concentration of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and histological changes in Anomalocardia brasiliana and Crassostrea rhizophorae from Pernambuco, Brazil after the 2019 oil spill. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 192, 115066 (2023).

Pérez, C., Velando, A., Munilla, I., López-Alonso, M. & Daniel, O. Monitoring polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon pollution in the marine environment after the Prestige oil spill by means of seabird blood analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 707–713 (2008).

Billah, M. M., Bhuiyan, M. K. A., Amran, M. I. U. A., Cabral, A. C. & Garcia, M. R. D. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) pollution in mangrove ecosystems: Global synthesis and future research directions. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 21, 747–770 (2022).

Shen, H., Grist, S. & Nugegoda, D. The PAH body burdens and biomarkers of wild mussels in Port Phillip Bay, Australia and their food safety implications. Environ. Res. 188, 109827 (2020).

Sinaei, M. & Zare, R. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and some biomarkers in the green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 146, 336–342 (2019).

Rimayi, C. & Chimuka, L. Organ-specific bioaccumulation of PCBs and PAHs in African sharptooth catfish (Clarias gariepinus) and common carp (Cyprinus carpio) from the Hartbeespoort Dam, South Africa. Environ. Monit. Assess 191, 700 (2019).

RanjbarJafarabadi, A. et al. Distributions and compositional patterns of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and their derivatives in three edible fishes from Kharg coral Island, Persian Gulf, Iran. Chemosphere 215, 835–845 (2019).

Hong, W. J. et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and alkylated PAHs in the coastal seawater, surface sediment and oyster from Dalian, Northeast China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 128, 11–20 (2016).

Magalhães, K. M. et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in fishery resources affected by the 2019 oil spill in Brazil: Short-term environmental health and seafood safety. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 175, 113334 (2022).

Soares, M. O. & Rabelo, E. F. Severe ecological impacts caused by one of the worst orphan oil spills worldwide. Mar. Environ. Res. 187, 105936 (2023).

Magris, R. A. & Giarrizzo, T. Mysterious oil spill in the Atlantic Ocean threatens marine biodiversity and local people in Brazil. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 153, 110961 (2020).

Barron, M. G., Vivian, D. N., Heintz, R. A. & Yim, U. H. Long-term ecological impacts from oil spills: Comparison of Exxon Valdez, Hebei Spirit, and Deepwater Horizon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 6456–6467 (2020).

Carls, M. G., Short, J. W. & Payne, J. Accumulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by Neocalanus copepods in Port Valdez, Alaska. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 52, 1480–1489 (2006).

Snyder, S. M., Pulster, E. L., Wetzel, D. L. & Murawski, S. A. PAH Exposure in Gulf of Mexico demersal fishes, post- deepwater horizon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 8786–8795 (2015).

Franzellitti, S., Locatelli, C., Gerosa, G., Vallini, C. & Fabbri, E. Heavy metals in tissues of loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta) from the northwestern Adriatic Sea. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 138, 187–194 (2004).

Shilla, D. J. & Routh, J. Distribution, behavior, and sources of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon in the water column, sediments and biota of the Rufiji Estuary, Tanzania. Front. Earth Sci. (Lausanne) 6, 70 (2018).

Esposito, M. et al. Levels of non-dioxin-like PCBs (NDL-PCBs) in liver of loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta) from the Tyrrhenian Sea (Southern Italy). Chemosphere 308, 136369 (2022).

Arienzo, M. Progress on the impact of persistent pollutants on marine turtles: A review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 11, 266 (2023).

Lutz, P. L., Musick, J. A. & Wyneken, J. Adult migrations and habitat use. In The Biology of Sea Turtles Vol. 2 (ed. Lutz, P. L.) 225–241 (CRC Press, 2002).

Almeida, A. P. et al. Avaliação do estado de conservação da tartaruga marinha Chelonia mydas (Linnaeus, 1758) no Brasil. Biodiversidade Brasileira 1, 18–25 (2009).

Reisser, J. et al. Feeding ecology of the green turtle (Chelonia mydas) at rocky reefs in western South Atlantic. Mar. Biol. 160, 3169–3179 (2013).

Villa, C. A. et al. Trace element reference intervals in the blood of healthy green sea turtles to evaluate exposure of coastal populations. Environ. Pollut. 220, 1465–1476 (2017).

Barraza, A. D. et al. Persistent organic pollutants in green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) inhabiting two urbanized Southern California habitats. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 153, 110979 (2020).

Cammilleri, G. et al. Survey on the presence of non–dioxine-like PCBs (NDL-PCBs) in loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta) stranded in south Mediterranean coasts (Sicily, Southern Italy). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 36, 2997–3002 (2017).

Colman, L. P., Sampaio, C. L. S., Weber, M. I. & de Castilhos, J. C. Diet of Olive Ridley Sea Turtles, Lepidochelys olivacea, in the Waters of Sergipe, Brazil. Chelonian Conserv. Biol. 13, 266–271 (2014).

Polovina, J. J. et al. Forage and migration habitat of loggerhead (Caretta caretta) and olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) sea turtles in the central North Pacific Ocean. Fish Oceanogr. 13, 36–51 (2004).

Bowen, B. W. & Karl, S. A. Population genetics and phylogeography of sea turtles. Mol. Ecol. 16, 4886–4907 (2007).

Limpus, C. J. A Biological Review of Australian Marine Turtles (Qld Government, 2009).

Maruyama, A. S., Botta, S., Bastos, R. F., da Silva, A. P. & Monteiro, D. S. Feeding ecology of the olive ridley turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) in southern Brazil. Mar. Biol. 170, 131 (2023).

Liu, M. et al. PAHs in the North Atlantic Ocean and the Arctic Ocean: Spatial distribution and water mass transport. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 127, e2021JC018389 (2022).

Pritchard, P. Una nueva interpretación de las tendencias poblacionales de las tortugas golfinas y loras en México. Noticiero de Tortugas Marinas 76, 12–14 (1997).

Luschi, P. et al. A review of migratory behaviour of sea turtles off southeastern Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 102, 51–8 (2005).

Shigenaka, G., Lutz, P. & Milton, S. Oil toxicity and impacts on sea turtles. In Oil and Sea Turtles: Biology, Planning, and Response (ed. Shigenaka, G.) 35–47 (NOAA, 2003).

Camacho, M. et al. Potential adverse effects of inorganic pollutants on clinical parameters of loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta): Results from a nesting colony from Cape Verde, West Africa. Mar. Environ. Res. 92, 15–22 (2013).

Vilca, F. Z. et al. Concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in liver samples of juvenile green sea turtles from Brazil: Can these compounds play a role in the development of fibropapillomatosis?. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 130, 215–222 (2018).

Ylitalo, G. et al. Determining oil and dispersant exposure in sea turtles from the northern Gulf of Mexico resulting from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Endanger Species Res. 33, 9–24 (2017).

Lawal, A. T. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. A review. Cogent. Environ. Sci. 3, 1339841 (2017).

IBAMA. Boletim Fauna Atingida: Manchas de Óleo, Nordeste Brasileiro. (2020).

Silveira, J. Di. Morfologia do litoral. in Brasil: a terra e o homem vol. 1 253–235 (Companhia Editora Nacional, São Paulo, 1964).

Martins, L. R. & Coutinho, P. N. The Brazilian continental margin. Earth Sci. Rev. 17, 87–107 (1981).

Oliveira, P. R. A. Caracterização morfológica e sedimentológica da plataforma continental brasileira adjacente aos municípios de Fortim, Aracati e Icapuí-CE (Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, 2009).

Trujillo, A. P. & Thurman, H. V. Oceánografie (Computer Press, 2005).

Flint, M. et al. Postmortem Diagnostic Investigation of Disease in Free-Ranging Marine Turtle Populations: A Review of Common Pathologic Findings and Protocols.

Bolten, A. B. Techniques for measuring sea turtles. IUCN Res. Manag. Tech. Conserv. Sea Turtles 4, 110–114 (1999).

Wyneken, J. Guide to the Anatomy of Sea Turtles. Jacksonville, NOAA Technical Memorandum, MNFS-SEFSC, 470. (2001).

Rossi, S. et al. Concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in liver samples of green turtles Chelonia mydas stranded in the Potiguar Basin, northeastern Brazil. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 193, 115264 (2023).

Yaghmour, F., Samara, F. & Alam, I. Analysis of polychlorinated biphenyls, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and organochlorine pesticides in the tissues of green sea turtles, Chelonia mydas, (Linnaeus, 1758) from the eastern coast of the United Arab Emirates. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 160, 111574 (2020).

Collier, T. K. Forensic ecotoxicology. In From Sources to Solution (ed. Collier, T. K.) 503–506 (Springer Singapore, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4560-70-2_90.

Tobiszewski, M. & Namieśnik, J. PAH diagnostic ratios for the identification of pollution emission sources. Environ. Pollut. 162, 110–119 (2012).

Abdel-Shafy, H. I. & Mansour, M. S. M. A review on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Source, environmental impact, effect on human health and remediation. Egypt. J. Pet. 25, 107–123 (2016).

Wu, W. J. et al. Levels, distribution, and health risks of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in four freshwater edible fish species from the Beijing market. Sci. World J. 2012, 156378 (2012).

Moon, Y. et al. Toxicity and bioaccumulation of petroleum mixtures with alkyl PAHs in earthworms. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 19, 819–835 (2013).

Ito, K. et al. Distribution of parent and alkylated PAHs in Bivalves collected from Osaka Bay, Japan. Jpn. J. Environ. Toxicol. 18, 11–24 (2015).

Cong, Y. et al. Lethal, behavioral, growth and developmental toxicities of alkyl-PAHs and non-alkyl PAHs to early-life stage of brine shrimp, Artemia parthenogenetica. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 220, 112302 (2021).

Arienzo, M. et al. Comparative study of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in salt gland and liver of loggerhead turtle Caretta caretta (Linnaeus, Cheloniidae) stranded along the Mediterranean coast, Southern Italy. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 263, 115355 (2023).

Miguel, C. et al. Health condition of Chelonia mydas from a foraging area affected by the tailings of a collapsed dam in southeast Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 821, 153353 (2022).

Beyer, J., Jonsson, G., Porte, C., Krahn, M. M. & Ariese, F. Analytical methods for determining metabolites of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) pollutants in fish bile: A review. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 30, 224–244 (2010).

Romero, I. C. et al. Decadal assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in mesopelagic fishes from the gulf of mexico reveals exposure to oil-derived sources. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 10985–10996 (2018).

Kuzukiran, O. et al. An investigation of some persistent organic pollutants in loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 205, (2024).

Soares, E. C. et al. Oil impact on the environment and aquatic organisms on the coasts of the states of Alagoas and Sergipe, Brazil—A preliminary evaluation. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 171, 112723 (2021).

de Souza Dias da Silva, M. F. et al. Traces of oil in sea turtle feces. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 200, (2024).

Finlayson, K. A., Leusch, F. D. L. & van de Merwe, J. P. The current state and future directions of marine turtle toxicology research. Environ. Int. 94, 113–123 (2016).

Feitosa, A. F. et al. The impact of chronic and acute problems on sea turtles: The consequences of the oil spill and ingestion of anthropogenic debris on the tropical semi-arid coast of Ceará, Brazil. Aquatic Toxicol. 269, 106867 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Source diagnostics of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban road runoff, dust, rain and canopy throughfall. Environ. Pollut. 153, 594–601 (2008).

Camacho, M. et al. Comparative study of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in plasma of Eastern Atlantic juvenile and adult nesting loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 64, 1974–1980 (2012).

Particularly Sensitive Sea Areas (PSSA). (2007).

Meire, R. O., Azeredo, A. & Torres, J. P. M. Aspectos ecotoxicológicos de hidrocarbonetos policíclicos aromáticos. Oecologia brasiliensis 11, 188–201 (2007).

Bucchia, M. et al. Plasma levels of pollutants are much higher in loggerhead turtle populations from the Adriatic Sea than in those from open waters (Eastern Atlantic Ocean). Sci. Total Environ. 523, 161–169 (2015).

Swartz, C. D. et al. Chemical Contaminants and Their Effects in Fish and Wildlife from the Industrial Zone of Sumgayit, Republic of Azerbaijan. Ecotoxicology 12, 509–21 (2003).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Foundation for Research, Science and Technology Support of the State of Pernambuco—FACEPE, for the master’s scholarship granted to student Giulia de Andrade Lima Bertotti, the Postgraduate Program in Biodiversity and Conservation of the Federal Rural University of Pernambuco, the Laboratory of Herpetological and Paleoherpetological Studies—UFRPE, the Laboratory of Marine and Environmental Studies—PUC-Rio, NGO ECOASSOCIADOS and the Cetaceans of Costa Branca Project—UERN. RSC is a CNPq research fellow (proc. no. 312697/2021-0). The comments provided by three anonymous reviewers are greatly acknowledged and contributed to enhancing the final version of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.A.L.B.: investigation, methodology, formal analysis, writing-original draft; writing-review and editing; R.S.C.: conceptualization, supervision, resources, funding acquisition, writing-review and editing; G.J.B.M.: conceptualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, writing-review and handling; C.G.M., F.C.M. and K.C.G.: methodology, validation, formal analysis; S.A.G. and L.R.S.P.: performed material preparation, data collection, and analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was carried out following Brazilian legislation based on SISBio authorization no. 76577, valid from November/2020 to November/2022.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Andrade Lima Bertotti, G., da Silva Carreira, R., de Moura, G.J.B. et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in tissues of sea turtles stranded on oil impacted beaches in Northeastern Brazil. Sci Rep 15, 31549 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17129-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17129-4