Abstract

The relevance for a circular economy has been brought to light by the overuse of natural resources, especially when it comes to recovering valuable materials from secondary sources to support important technologies like renewable energy. Rare earth elements (REEs), which are indispensable for several cutting-edge applications, are found in considerable quantities in red mud, one of these sources. Target element speciation and thorough waste characterization are necessary for the effective recovery of REEs. Using citric acid as an environmentally benign leachant, this work aims to optimize the leaching parameters and comprehend the kinetics of REE extraction from red mud. The impact of leachant content, reaction temperature, and leaching time on REE leaching efficiency was assessed using a central composite design (CCD) in the context of response surface methodology (RSM). With a leaching efficiency of 90.16%, the ideal parameters were found to be 2 mol/L citric acid, 343 K, and 240 min. With an activation energy of 25.10 kJ/mol, kinetic study using a shrinking sphere model demonstrated that the leaching process is controlled by a diffusion-controlled mechanism. The findings show that citric acid could potentially be used to recover high REEs under moderate circumstances, offering a sustainable and effective way to recover key elements from red mud. This strategy improves the supply chain for valuable resources and encourages the effectiveness of resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The most prevalent industrial procedure for processing bauxite into alumina continues to be the Bayer process. During autoclave digestion, boehmite and gibbsite, composed of aluminum hydroxide, undergo dissolution using a NaOH solution mixed with calcined lime at elevated temperatures (150o–250 °C) and pressure (3.5 MPa). Because of their amphoteric nature, aluminum hydroxide dissolves, forming sodium aluminate (NaAlO₂), and impurities separate in the solid phase as “red mud” in the clarifying stage1. Bauxite’s silica minerals undergo pretreatment to create desilication products like sodalite and cancrinite, which retain soda in the red mud in addition to causing soda losses. For the production of metallurgical-grade alumina, the sodium aluminate solution is added to the mixture at about 60 °C, and then it is calcined at 1100 °C to precipitate aluminum hydroxide (gibbsite). The Hall-Héroult electrolytic method harnesses this alumina as a vital raw material to produce aluminum metal. The reactions (Eqs. 1–3) represent the production of alumina from Bauxite’s silica minerals2.

Step-I

Step-II

Step-III

Approximately 1–2 tons of bauxite waste, often referred to as red mud, are generated for every ton of alumina via the Bayer method3. The bauxite’s mineralogy and the processing environments decide the red mud’s composition and physical and chemical attributes. The generation of red mud that accompanies a rapid increase in aluminum consumption has grown to be a serious environmental issue. In 2018, India alone produced 3.4 million tons of aluminum, whilst worldwide red mud generation reached over 150 million tons per year in 2017, with accumulated inventories surpassing 4 billion tons4,5. Generally remaining as a muddy sludge having a highly alkaline pH of around 12, red mud creates major issues with the environment, such as the requirement to occupy large land areas and the potential for contamination6. Present-day disposal procedures, such as retaining waste in enormous tailing ponds, are inefficient and unsustainable. Large-scale usage of red mud is still rare despite extensive study, highlighting the urgent need for creative management techniques and high-volume utilization pathways to mitigate its environmental effect7. For metallurgical uses, the most suitable red mud utilization approach should effectively separate chemically bound minerals while consuming the least amount of energy and generating the minimum quantity of secondary waste.

Bauxite residue or red mud is a polymetallic material that comprises numerous precious metals. Red mud’s characteristic composition contains 48–54% iron oxide (Fe2O₃), 17–20% aluminum oxide (Al2O₃), 3–4% titanium dioxide (TiO₂), 4–6% silicon dioxide (SiO₂), 1–2% calcium oxide (CaO), and 3–5% sodium oxide (Na2O). Furthermore, apart from these major elements, it also comprises various trace elements in different quantities, including uranium, niobium, barium, strontium, potassium, phosphorus, magnesium, hafnium, zirconium, thorium, manganese, chromium, nickel, copper, lead, zinc, cadmium, and REEs in various amounts1,8. Based on the classification of bauxite ore, the mining location, and the Bayer process’s processing parameters, the exact composition of red mud might differ noticeably. The REEs’ concentration in the red mud in the course of the Bayer process is generally about two times greater than their original concentration in the bauxite ore9. REEs are considered as critical metals due to their increasing demands in current modern technology, and hence recovering them from secondary resources like bauxite waste provides encouraging prospects10. Enrichment of REEs in red mud and their high amounts produced worldwide may make it an efficient secondary supply of these strategically important elements11. Few investigations have been conducted on other rare earth elements (REEs), with the majority of the studies concentrating on scandium12,13. Moreover, investigations on utilizing organic acids for REE leaching from red mud are very limited. On the other hand, so as to construct further purification methods, it is vital to examine the leaching of the main constituents.

Previous investigations have mainly scrutinized the use of inorganic acids in the leaching of REEs and key elements. The influence of different variables on the leaching efficiency, like temperature, liquid-to-solid ratio, leaching time, and acid type and concentration has been examined14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. Different acid leaching procedures to leach the REEs from red, have been investigated by various researchers. Inorganic acids including HCl, H₂SO₄, and HNO₃ have been extensively utilized because they are potent leaching agents. Borra et al. found that treatment of red mud with HCl resulted in the recovery of about 80% REEs16. Rivera et al. used a dry digestion technique followed by multistep acid leaching with HCl and H₂SO₄, which greatly improved the concentration of REEs23. Ochsenkühn-Petropoulou et al. investigated Greek red mud and obtained up to 80% scandium leaching and 25–65% recovery of other REEs with 6 M solutions of H₂SO₄, HNO₃, and HCl19. Sugita et al., with Jamaican red mud, obtained almost 80% leaching efficiency with a series of inorganic acids such as HCl, H₂SO₄, HNO₃, and H₃PO₄24. Though less aggressive, organic acids have also proven useful for environmentally friendly leaching. Ujaczki et al. studied oxalic acid (C₂H₂O₄) and citric acid (C₆H₈O₇) with efficiencies comparable to inorganic acid like HCl for leaching REEs, pointing toward their potential as clean alternatives for REEs’ extraction25. The process temperature was 90 °C.Shalchian et al. used 0.5 mol/L citric acid, although the percentage of leaching was less than 70%>26, but they have not informed about REE extraction. Atalay Kalsen et al. reported the leaching behavior of citric acid with lower efficiency27.

As mentioned above few reports are available in literature on the study of leaching of REEs from red mud using organic acids such as oxalic and citric acids showing low leaching efficiency, and under conditions of high operating temperature as well as very high pH. A large number of experiments with more consumption of chemicals has also been a great concern.In the present research, an attempt has been initiated to examine the leaching efficiency of low molecular weight environmentally benign compound like citric acid which can bind with rare earth metal ions to form stable complexes by tuning the parameters such as leachant concentration, temperature and leaching time simultaneously in order to obtain maximum efficiency. The optimized leaching condition has been designed with the help of statistical modeling approach using Response Surface Methodology (RSM) via Central Composite Design. The kinetics investigations have been carried out using different models in order to explore insights into the mechanism aspect of leaching process of REEs by citric acid.

Experimental

Materials and methods

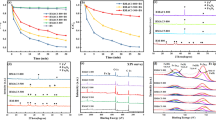

The Institute of Minerals and Materials Technology (CSIR-IMMT) in Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India, supplied the red mud sample used in the present research work. The sample was collected and then dried in a hot air oven at 105 °C for the overnight till it reached a steady weight16. After that, the sample was analyzed without further purification. After red mud collection, the material was mechanically milled in a ball mill to achieve higher specific surface area and reduced particle size. To increase the solid–liquid interfacial contact and facilitate better interaction among leaching agent and red mud particles, this pretreatment was essential. The average particle size (D[4,3]) was 7.17 μm, with distribution percentiles of D10 = 1.31 μm, D50 = 3.74 μm, and D90 = 16.9 μm, according to the analysis of the particle size distribution conducted using a Microtrac Sync particle size analyzer (Fig. 1a). This type of particle size reduction significantly enhances the leaching kinetics. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area, which is one of the most significant parameters on which the efficiency of leaching depends, especially when it comes to extracting REEs. It was assessed using a Belsorp Mini-X device. The red mud sample was pretreated with nitrogen as the adsorptive gas at a temperature of 120 °C under vacuum prior to analysis. A surface area of 23.151 m²/g, a total pore volume of 0.0118 cm³/g, and an average slit pore width of 1.0180 nm were all determined by the BET analysis (Fig. 1b)28,29.

XRD (X-ray diffraction) and scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) were used to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the composition. A BET surface area analyzer was used to calculate the surface area, and a Simultaneous Thermal Analyzer was used to inspect the thermal degradation. The preliminary leaching experiments used a number of acids, which were procured from Merck Life Science Ltd. These included nitric acid (69% assay), hydrochloric acid (35% assay), acetic acid (99% assay), ascorbic acid (99% assay), p-toluenesulfonic acid monohydrate (98% assay), and citric acid monohydrate (99% assay). For the leaching procedure, distilled water was used to prepare acid solutions of chosen concentrations.

Characterization of red mud

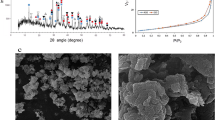

A Rigaku Ultima IV diffractometer was used for crystallographic study so as to recognize the solid-phase structures. Cu Kα radiation was used for the measurements, which covered a 2θ range of 100–90° and had a step size of 0.02°. HighScore software (PANalytical Highscore plus 3.0) was used to examine and evaluate the diffraction patterns that were acquired. XRD analysis shows that hematite is the main phase (Fig. 2) of the red mud scanned in this study. The main minerals found in the red mud were titanium dioxide, aluminum hydroxide, and hematite when compared to reference patterns30,31. A Carl Zeiss EVO-18 SEM-EDX device was used to analyze the sample in order to get insight into the solid phase morphology and REE distribution. The powdered samples were securely fastened to a specimen holder. To take pictures of the particles’ cross-section, the solid powders were put straight onto the support. The samples’ inherent conductivity meant that they didn’t need a metal coating. The SEM images (Fig. 3) demonstrate that the red mud is a very fine substance and aggregates develop, while the EDX plot verifies that iron and aluminum are the most available elements (Fig. 4).

A NETZSCH STA 449 F3 Jupiter thermo gravimetric analyzer (TGA) was used to examine the thermal decomposition of the red mud. The graphic illustrates the TGA profile’s progressive decomposition process (Fig. 5). It is estimated that the removal of adsorbed water causes an initial mass loss of 2.23% between 29.3 °C and 170.5 °C. Phase transitions, along with possible oxidation processes involving iron and aluminum oxides, are responsible for the subsequent mass losses that were detected at 321.0 °C, 423.5 °C, 490.3 °C, and 679.9 °C. The breakdown of the sample’s hydroxides is the primary cause of the weight loss that happens between 300 °C and 600 °C. A slight variation in mass between 821.3 °C and 998.3 °C indicates the presence of high-temperature reactions or an insignificant loss of material. The red mud’s thermal stability is demonstrated by its ultimate residual mass of 90.23% at 998.3 °C. DTA profile showing multiple endothermic peaks indicates various phase changes, transitions, and decomposition processes.

Chemical analysis

A mineralization procedure was performed using 1 g of red mud at 373.15 K for the purpose to figure out the REE content of the sample. About 1:50 solid-to-liquid ratio was subjected to digestion using aqua regia, followed by the addition of 2 ml of HF to assure complete leaching. Then the resulting liquor was diluted with distilled water to make up the volume to 50 mL. Using an inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES) from Thermo Fisher Scientific 7600 (iCAP 7000 series), the elemental analysis was performed. Two simultaneous leaching trials, including elemental analysis for the leaching experiments, were performed out in triplicate using ICP-OES for guaranteeing data reliability. For verification of the validity of the outcomes, the entire scrutiny was carried out again in several other trials. The following table (Table 1) provides an inventory of the average concentrations of REEs that were found. The leaching efficiency for different metals has been calculated with the help of Eq. 4.

Results and discussion

Preliminary experiments with different leaching agents

To figure out the most effective reagent for leaching REEs, an initial investigation was conducted using a number of organic acids including, citric acid, ascorbic acid, p-Toluenesulfonic acid (PTSA) and acetic acid. The red mud sample was agitated for 60, 120, and 180 min at 298 K while keeping the solid-to-liquid (S/L) ratio constant at 1:50 g/mL. In the first phase, acid concentrations of 1 mol/L and 2 mol/L were used. Amongst all the acids tested, citric acid had the highest leaching efficiency for REEs, which are shown in the figure (Figs. 6a and c and 7a and c). This may be due to higher complexing ability of citric acid with rare earths.Keeping in view the above findings, citric acid has been employed as leachant for further experimental studies.

On the basis of above mentioned preliminary experiments with different organic acids and varying leaching time, it has been observed that irrespective of experimental conditions, citric acid is the most effective one showing maximum leaching efficiency for REEs from red mud. Therefore, to examine the effect of temperature, leaching time and citric acid concentration on leaching efficiency of citric acid, at a fixed S/L ratio 1:50 g/mL, experiments were carried out ((Fig. 8. a-c). All the three variants have positive impact on the leaching efficiency of rare earths.Table 2 provides an overview of the experimental findings of all the preliminary studies.

Development of the model using RSM

Stat-Ease, Inc.‘s Design Expert (Version 12) statistical software program was used for developing a RSM model via CCD. To optimize the leaching of REEs from red mud, a statistical experimental design was constructed using CCD. RSM is ideal for the evaluation of variable interactions, fitting quadratic surfaces, and optimizing process parameters with the minimum possible trials32. This statistical and mathematical method is employed in process optimization, empirical development of models, and the investigation of the interrelationship between various contributing factors. RSM enhances response variables impacted by several independent input factors and aids in the establishment of regression models by employing quantitative experimental data33. CCD usually comprises of 2n factorial runs with 2n axial runs, and center runs (nc) have been employed to quantify the error caused by the experiment. 2n axial points have been included in the 2n factorial, which is denoted by ± 1 notation, generating this experimental design. The number of runs needed to build a whole replicate of the design rises quickly as the number of variables (n) enhances, since each variable is scrutinized at two levels. The quadratic impact was calculated by means of CCD, as 2n factorial designs are not able to estimate peculiar second-order effects individually. The model for the leaching of REEs from red mud was subsequently created using CCD. A model of the reaction with corresponding parameters was used in the statistical analysis to optimize the process conditions for the intended response34. Using response surface approaches, the statistical parameters are computed using ANOVA. Three primary procedures are involved in optimization using the RSM method: first, statistically established experiments; second, calculating the coefficients in a statistical model; and third, anticipating the response and ensuring that the model is adequate for the experiment setup. Temperature (K), leachant concentration (mol/L), and leaching time (min) were chosen as input variables. Depending on the design of the experiment, the parameters’ range and level fluctuated. Effective leaching of desired REEs from red mud has been demonstrated to rely on these three factors and the associated ranges. In accordance with the design, the assessments’ independent variables are supposed to be continuous and controlled by experiments with barely noticeable errors. The purpose of the experimental design was to determine a reasonable approximation for the fundamental interaction between independent variables and response in order to maximize the effectiveness of response variables. The randomization of data was implemented in the experiments in order to reduce oversights and the consequences of uncontrollable factors. An empirical model that correlates the experimental variables using a second-degree polynomial equation was developed utilizing the data that were collected. Table 3 below lists the range and coded levels of the experimental variables considered in this leaching investigation.

In Eq. 5, N indicates the total number of experimental runs, or the number of tests needed for the design. This comprises axial points, whose distance from the center is specified by (2n)25, which equals ± 1.681 for n = 3 in this investigation, center points at the origin, and conventional 2n factorial points. The axial points (2n) facilitate screening analysis and enhance model readability, while the variance of model prediction is constant at all sites distributed equally from the center. Equation 5, corresponding to the total number of experimental runs as 20 in this CCD design, taking into account eight factorial points, six axial points, and six center point replicates the configuration. In this investigation, the amount of REEs leached (measured in mg/L) is the response variable. CCD experimental design, along with the experimentally obtained response, has been provided in Table 4.

Model fitting and ANOVA analysis

As illustrated by the provided table (Table 5), the model’s statistical significance has been assessed using crucial variables such the F-value, P-value, correlation coefficient (R2, and analysis of variance (ANOVA). According to this investigation, the model that was most appropriate for the experimental data was identified as the two-factor interaction (2FI) model.

Statistical analysis is critical for assessing the significance and viability of the model. The importance of the model has been established by a high F-value and a very low P-value. The F-value greater than unity shows that the experimental data’s variability is comprehensively clarified, which enhances the significance of the influences of numerous factors35. By determining the extent to which the independent variables and interactions among them explain the variations in the experimental response values, the correlation coefficient (R2 was applied in judging the model’s goodness of fit. A model is considered well-fitted if the R2 is close to unity36. Here, a robust model fit was revealed by the R2 value of 0.97. Moreover, the model’s reliability was reinforced by the higher value of adjusted R2 (0.96). The validity of the model has been further demonstrated by the expected correlation coefficient. The findings suggest that the independent factors account for 97% of the variation in leaching efficiency, leaving just around 6% (0.96–0.90) of the variability unaccounted for. A 2FI model equation based on the optimal design was successfully used to fit the experimental data following an ANOVA and multiple regression analysis. The ANOVA equation in coded form has been symbolized with the help of Eq. 6. The statistical parameters are shown in Table 6. Figure 9 displays the actual and anticipated amounts of REE leaching.

Leachant concentration (Factor A) is the most prominent factor in the model, accounting for almost 63% (224.48 out of 357.42) of the overall model variance, corresponding to the statistical analysis. Leaching time (Factor C), which contributes around 7%, and reaction temperature (Factor B), which contributes roughly 27%, come next. The remaining ~ 3% is made up of the aggregate contribution of the interaction terms (AB, AC, and BC), demonstrating that although interactions do occur, their overall impact is rather small in comparison to the significant implications. With p-values < 0.0001 and high F-values (A = 387.85, B = 165.15, and C = 43.08), all three fundamental factors-A (leachant concentration), B (temperature), and C (time)-are statistically significant, demonstrating their major impact on the leaching performance. The adoption of a 2FI model to capture both individual and interacting effects in the process is supported by the interaction terms (AB, AC, and BC), which similarly exhibit significance, although at lower F-values and p-values below 0.05. Some of the vital observations from Table 4 are mentioned below.

-

1.

With 13 degrees of freedom, the residual sum of squares in the present scenario is 7.52, yielding a mean square residual of 0.579. This low residual value indicates that there is little unexplained variation between the model predictions and the experimental outcomes.

-

2.

The lack-of-fit test assesses if the model is inadequately capturing the response surface or is missing higher-order variables. In our instance, the model fits the experimental data well, and the included terms adequately explain the variance, as seen by the lack-of-fit being not significant (F = 2.52, p = 0.1625).

-

3.

The inherent uncertainty in the experimental system is represented by pure error, which results from repetitious runs. The consistent and repeatable nature of the experimental setup is confirmed by the low pure error (0.299).

-

4.

The overall variance in the dataset is represented by the sum of squares i.e. 364.95. The model accounts for 357.42% of this, meaning it captures more than 97.9% of the variability. The residual error is the remaining 7.52. A high R2 value further supports this, confirming the model’s significant ability to anticipate.

ANOVA was employed to assess the statistical significance of the regression equation’s significant parameters. The model only included terms that have significant p-values (p < 0.05). As part of the RSM study, Design Expert software was used to calculate the coefficients by least squares regression in Eq. 6. The estimated REE leaching at the center point (coded level 0 for all variables) is shown by the intercept (11.90). As all other factors remain constant, the primary effects-4.05 A for concentration, 2.65B for temperature, and 1.35 C for time-show the change in REE leaching (in mg/L) as each factor rises from its coded center level to + 1. For instance, leaching increases by around 4.05 mg/L when concentration is increased from 0.75 to 2 mol/L. When both factors increase at the same time, the additional effect is represented by interaction terms such as 0.7991AC; in this case, concentration and time together increase leaching by about 0.80 mg/L over their respective effects.

Surface and contour plots

To demonstrate the implications and interconnections of the three variables on REE leaching from red mud using citric acid, three-dimensional surface plots were constructed (Figs. 10, 11 and 12)37. Observations from ANOVA (Eq. 6) and Table 4 demonstrate that, leachant concentration (A) and reaction temperature (B) had greater impact on the REE leaching than the leaching time (C). The order of the interaction effects was AC > BC > AB. The simultaneous effects of leachant concentration and reaction temperature on REEs’ leaching are depicted in Fig. 10 (a and b). REE leaching improved when the temperature rose from 298 K (leaching efficiency 58.8%) to 343 K (leaching efficiency 90.16%) with 2 mol/L citric acid concentration and 240 min leaching time. On increasing the citric acid concentration increased from 0.75 mol/L to 2 mol/L, the REE leaching efficiency enhanced from 35.47 to 64.56% at 343 K and 90 min leaching time. Simultaneous increase in citric acid concentration and temperature has a positive impact on the leaching efficiency of REEs. Surface and contour plots showing the impact of leaching time (90 to 240 min) and leachant concentration (0.75 to 2 mol/L), both of which improved REE leaching, are shown in Figs. 11 (a and b). Similarly, REE leaching efficiency rose from 64.56 to 90.16% when leaching reaction time increased from 90 min to 240 min with 2 mol/L citric acid concentration and temperature 343 K. Leaching time and rise in temperature simultaneously, affect leaching efficiency in a positive manner as shown in Figs. 12 (a and b).

Optimization of the independent variables

The three basic phases of optimization utilizing RSM via CCD are response prediction with model validation inside the experimental framework, mathematical model coefficient estimation, and statistical experiment design38,39. The optimum conditions for the leaching of REEs from red mud were effectively determined by this study. The maximum REE leaching efficiency was achieved using 2 mol/L citric acid, reaction temperature of 343 K, and a leaching time of 240 min, as evident from the 3D surface and contour plots (Fig. 13). The predicted value of REE leaching was estimated as 22.09 mg/L as against the experimental value of 22.5 mg/L which shows an error percentage of 1.82.

FTIR and SEM-EDX studies post leaching

The FTIR profiles of the red mud sample prior to leaching (Sample-1) and the after leaching sample (Sample-2), obtained under optimum conditions of REE leaching, were undertaken and shown in Fig. 14. There are a few clear shifts in the peak positions and intensity variations, corresponding to different functional groups. During leaching with citric acid, a blue shift in the O-H stretching vibration was observed, changing from 3370 cm⁻¹ to 3366 cm⁻¹40. Likewise, there was a shift from 2355 cm⁻¹ to 2360 cm⁻¹ in the asymmetric stretching vibration of CO₂, which is generally seen in FTIR spectra because of contamination41. Furthermore, a variation in the C = O vibration from 1712 cm⁻¹ to 1714 cm⁻¹ was noticed, signifying that the leaching process had changed the structure42. Moreover, a clear peak at 1217 cm⁻¹ was seen, which is due to the C–O stretching vibration43. These spectrum changes indicate that the leaching process produced noticeable modifications in the chemical environment of the sample, probably on account of interactions between the red mud matrix and citric acid. A potential complexation of REEs with citric acid is indicated by a change in the O-H stretching vibration. The C = O stretching band indicates complexation between REEs and carboxyl groups of citric acid. In both the samples, the C = O stretching vibration is still noticeable at 1217.83 cm⁻¹, but its intensity varies, suggesting possible complexation between REEs and citric acid functional groups took place during leaching.

The constituent composition after citric acid leaching has been displayed as EDX analysis in Fig. 15. Effective leaching is indicated from the sample’s EDX spectrum following leaching at the optimization stage, which clearly indicates a sharp drop in the intensities of La as compared with Fig. 4 and presence of elements like Al and Fe which are not leached. This provides us with proof of the rare earth elements’ depletion in the solid residue and supports the leaching efficiency determined by our quantitative measurements. This characterization provides information about the residue’s surface-level modification and supports the anticipation on the migration of components during the leaching process.

These findings describe how efficiently citric acid dissolves REEs, showing its extracting ability. Citric acid’s leaching efficiency is due to its complexation with REEs present in red mud. Citric acid primarily ionizes into H+ ions and citrate anions in the multi-step leaching mechanism (Eqs. 7–10). The hydrogen ions and citrate anions are first released upon dissociation of citric acid44. The formation of soluble rare earth-citrate complexes takes place in the presence of H⁺ ions which assist the displacement of REE ions45,46. These results provide vital information on the potential application of citric acid as an environmental friendly leaching agent for the REEs’ recovery from industrial waste.

Kinetics analysis of leaching

The establishment of quantitative measurement of citric acid leaching kinetics can confirm the leaching process of REEs from red muds. A standard kinetic model that demonstrates the relationship between solid-liquid extraction (leaching) rate and mechanism. The Shrinking Core Model (SCM) has been employed to evaluate the experimental results. As the leaching reaction proceeds by gradual disintegration of a solid particle, the unreacted core diminishes and the SCM offers a basis for understanding the leaching mechanism. Internal diffusion administers the leaching process in this study, and SCM may be used to elucidate the proper leaching kinetics. These model equations offer vital insights into the rate-determining step of the leaching process by permitting the quantitative valuation of reaction rates and diffusion controls, the equations of leaching kinetics (Eqs. 11 and 12) listed below are used to know the mechanism of leaching of REEs47,48,49.

Nonetheless, the following formula may be used for the leaching kinetic model if the chemical reaction governs the leaching process.

Where x = fraction leached of REEs from the red mud, t = time of reaction in min, kc or kd =Rate constants for surface chemical reaction and diffusion, respectively.

According to the SCM, the rate-governing phase in the leaching process was determined to be reagent diffusion across the boundary layer. Based on the literature and depending on the reaction circumstances, the surface chemical reaction may also function as the rate-controlling step. The findings have been displayed in Figs. 16a and b. The results showed that boundary layer diffusion dominated acid leaching of REEs, and the model’s dependability was confirmed by R2 value of more than 0.98. Table 7 summarizes the R2 and reaction rate constant (Kc/Kd) for REE leaching with citric acid, which were calculated for both diffusion and reaction-controlled models. To determine how temperature changes affected the leaching rate, kinetic tests were conducted at varied temperature range, 298–343 K. Important characteristics like temperature, leachant concentration, and leaching time do influence the rate constant substantially as evident from in the model’s equation. When addressing the leaching of non-porous spherical particles, the assumption of constant particle size holds whereas the particle core reduces during the leaching process. For modeling purposes, the total REE content was taken into account because the majority of the REEs in the red mud indicate comparable kinetic behaviour. The leaching agent’s slow diffusion across the boundary layer was verified as the rate-governing step, offering crucial information for maximizing the extraction of REEs from red mud.

Determination of activation energy (Ea)

Arrhenius equation (Eq. 13) was used to calculate the leaching reaction’s apparent activation energy (Ea). Arrhenius plot was created to investigate how temperature affected the leaching reaction rate50. Figure 17 shows plot of lnk versus 1000/T and the activation energy (Ea) was calculated from the slope of linear plot. Activation energy of 25.10 kJ/mol for REE leaching was obtained when REEs were leached in the citric acid medium with temperature varying from 298 K to 343 K. A diffusion-controlled reaction usually has a lower activation energy (Ea) (< 40 kJ/mol), while a chemically controlled reaction usually has an Ea larger than 40 kJ/mol. Consistent with the above criteria, the process is mostly diffusion-controlled instead of chemical reaction-controlled since the activation energy is 25.10 kJ/mol51,52. The notion that the rate-controlling stage in the leaching of REEs from red mud is the slow diffusion of leaching agents across the boundary layer is further supported by this study.

Techno-economic assessment and environmental considerations

Regarding the leaching of rare earth elements from red mud, a comparison of citric acid and conventional inorganic acids (HCl, H2SO4) reveals some important trade-offs. Citric acid has a leaching effectiveness for REEs that is quite equivalent to that of inorganic acids like H₂SO₄ and HCl, although it generally has a slightly higher reagent expenditure. Because inorganic acids are corrosive, they require high-quality, acid-resistant equipment and protective measures, which raises the operating costs and the complexity of the infrastructure. Citric acid has the advantage from environmental and safety standpoint because it is biodegradable, generates fewer corrosive residues, and minimizes the neutralization load. Additionally, neutralization of waste acid streams produces a large amount of waste sludge, which raises disposal costs and adds environmental risks. From the perspective of process design, citric acid is easier for workers to handle, and compatible with standard reactors walled with polymers or stainless steel, which in turn reduces capital and maintenance costs. Its application also has long-term sustainability benefits and aligns with concepts of the circular economy and green chemistry. Citric acid provides a feasible and not-so-distant alternative to inorganic acids, which are more established at the industrial level. This is particularly true for small- to medium-sized, decentralized REE recovery applications, given the lifetime and collateral costs associated with their use.

Conclusion

The leaching of REEs from red mud using environmentally benign citric acid has been studied varying three significant independent factors such as citric acid concentration, leaching time, and reaction temperature. Design of experiments followed by use of RSM through CCD for process optimization was executed to minimize the number of experiments, reduce chemical consumption, and preserve energy. The observations revealed that REE leaching was 90.16% under the ideal leaching conditions, which were found to be a citric acid concentration of 2 mol/L, temperature of 343 K, and leaching time of 240 min. By modulating the leaching time as well as temperature, the leaching kinetics was scrutinized using a shrinking core kinetic model. The activation energy of 25.10 kJ/mol obtained from the Arrhenius plot showed that, under the investigated conditions, the leaching process proceeds by diffusion-controlled mechanism. As a final point, the present process offers encouraging results for more development of eco-friendly feasible procedure for REEs leaching from red mud. For the sustainable leaching of REEs from red mud, scaling up the process to pilot and industrial levels could be beneficial attributable to its high efficiency and characterized kinetics. This work offers a novel pathway and may be escalated to large scale for the sustainable recovery of REE from red mud which is an important step towards circular economy in metallurgical waste treatment. The following advantages, challenges and requirements are concluded from the above investigations.

-

i.

Advantages of Industrial Integration: In conjunction with the concepts of sustainable and green chemistry, citric acid is non-toxic, biodegradable, and safer to handle than inorganic acids. Gentle operating conditions: Lower energy and equipment expenses result from the process’s operation at comparatively low temperatures (298–343 K) and atmospheric pressure.

-

ii.

Challenges to Be Overcome: Recycling or regeneration strategies might prove essential to large-scale citric acid use in order to preserve economic viability. After leaching, the solid residue needs to be identified and handled carefully, particularly if big amounts are produced.

-

iii.

Essential Requirements for Scaling Up: Process flow development with leaching systems or continuous stirred-tank reactors (CSTRs) on a pilot scale. Cost-benefit analysis and life cycle assessment (LCA) are used to compare against conventional REE extraction techniques.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Shrey, A. & Nikhil, D. Evaluation of red mud as a polymetallic source – A review. Min. Eng. 171, 107084. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2021.107084 (2021).

Archambo, M. & Kawatra, S. K. Red mud: Fundamentals and new avenues for utilization. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 42, 427–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/08827508.2020.1781109 (2021).

Kumar, S., Kumar, R. & Bandopadhyay, A. Innovative methodologies for the utilisation of wastes from metallurgical and allied industries. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 48, 301–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2006.03.003 (2006).

Evans, K. The history, challenges, and new developments in the management and use of red mud. J. Sustain. Metall. 2, 316–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40831-016-0060-x (2016).

Wang, L., Sun, N., Tang, H. & Sun, W. A review on comprehensive utilization of red mud and prospect analysis. Minerals 9, 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/min9060362 (2019).

Power, G., Gräfe, M. & Klauber, C. Red mud issues: I. Current management, disposal and storage practices. Hydrometallurgy 108, 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2011.02.006 (2011).

Pontikes, Y. & Angelopoulos, G. N. Red mud in cement and cementitious applications: current status and a possible way forward. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 73, 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2013.01.005 (2013).

Gu, H., Wang, N. & Liu, S. Characterization of bayer red mud from guizhou, China. Min. Metall. Explor. 29, 169–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03402256 (2012).

Borra, C. R., Blanpain, B., Pontikes, Y., Binnemans, K. & Van Gerven, T. Recovery of rare earths and other valuable metals from red mud (bauxite residue): A review. J. Sustain. Metall. 2, 365–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40831-016-0068-2 (2016).

Nilam, S. & Sujata, M. A review on the recovery and separation of rare earths and transition metals from secondary resources. J. Clean. Prod. 220, 884–898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.094 (2019).

Aditya Ranjan, R. & Sujata, M. Hydrometallurgical technique as a better option for the recovery of rare earths from mine tailings and industrial wastes. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 36, 101311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scp.2023.101311 (2023).

Gabrielle, G., Eric, W. & Alexandra, L. Rare Earth metals from secondary sources: review of potential supply from waste and byproducts. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 167, 105213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105213 (2021).

Duo-rui, Z. et al. Extraction of al and rare earths (Ce, gd, sc, Y) from red mud by aerobic and anaerobic bi-stage bioleaching. Chem. Eng. J. 401, 125914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2020.125914 (2020).

Shivendra, S., Manish Kumar, S. & Banshi Dhar, P. Extraction of lanthanum and cerium from Indian red mud. Int. J. Min. Process. 127, 70–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.minpro.2013.12.009 (2014).

Zhaobo, L. & Hongxu, L. Metallurgical process for valuable elements recovery from red mud—A review. Hydrometallurgy 155, 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2015.03.018 (2015).

Chenna Rao, B., Yiannis, P., Koen, B. & Tom Van, G. Leaching of rare earths from bauxite residue (red mud). Min. Eng. 76, 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2015.01.005 (2015).

Wang, K. Q., Yu, Y. B., Wang, H. & Chen, C. Study of hydrochloric acid leaching scandium from red mud. Chin. Rare Earths. 31, 95–98 (2010).

Zhang, J., Deng, Z. & Xu, T. Experimental investigation on leaching metals from red mud. Light Metals (2005).

Maria Th, O. P., Konstantinos, S., Leonidas, H., Constantinos, E. & N., M. & Pilot-plant investigation of the leaching process for the recovery of scandium from red mud. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 41 (23), 5794–5801. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie011047b (2002).

Weiwei, W., Yoko, P. & Chu Yong, C. Recovery of scandium from synthetic red mud leach solutions by solvent extraction with D2EHPA. Sep. Purif. Technol. 108, 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2013.02.001 (2013).

Boudreault, R., Fournier, J., Primeau, D. & Labrecque-Gilbert, M. M. Processes for treating red mud. USPatent US20150275330, (2015).

An, X., Xiao-hu, C. & Xiao-ning, T. The technological study and leaching kinetics of scandium from red mud. Nonferrous Met. Extr. Metall. 2, 51–53 (2010).

Rodolfo Marin, R., Brecht, U., Ghania, O., Koen, B. & Tom Van, G. Extraction of rare earths from bauxite residue (red mud) by dry digestion followed by water leaching. Min. Eng. 119, 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2018.01.023 (2018).

Sugita, K. et al. Method of recovering rare-earth elements. US Patent US20150086449 (2015).

Éva, U., Yannick-Serge, Z., Viktória, F. & Markus, L. Recovery of rare earth elements from Hungarian red mud with combined acid leaching and liquid-liquid extraction. In Proc. Bauxite Residue Valorisation and Best Practices Conf., Leuven, Belgium, 339–345 (2015).

Hossein, S., Mohsen Hajizadeh, N., Ionela, B., Abolfazl, B. & Francesco, V. A comparison study on the recovery of REEs from red mud by sulfation roasting–water leaching and citric acid leaching. Minerals 14 (10), 1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/min14101044 (2024).

Atalay, K., Tuğba Selcen, S., Hakan Burak, K., Yasin Ramazan, E. & Işıl, K. Chemical composition simplification of the Seydişehir (Konya, Turkey) alumina plant waste. J. Sustain. Metall. 5 (4), 482–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40831-019-00236-8 (2019).

Zheng, R. et al. Effect of particle size refinement on the leaching behavior of mixed rare-earth concentrate using hydrochloric acid. ACS Omega. 4 (6), 9813–9822. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b01141 (2019).

Fei, C. et al. Treating waste with waste: activated bauxite residue (ABR) as a potential wastewater treatment. ACS Omega. 9 (45), 45251–45262. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c06699 (2024).

Wanyan, L., Zehai, L., Ning, W. & Hannian, G. Selective extraction of rare Earth elements from red mud using oxalic and sulfuric acids. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10 (6), 108650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2022.108650 (2022).

Sasmita, P. REE-mineral phases in Indian red mud from the East Coast bauxite deposit. Curr. Sci. 124 (6). https://doi.org/10.18520/cs/v124/i6/753-757 (2023).

Azargohar, R. & Dalai, A. K. Production of activated carbon from luscar char: experimental and modeling studies. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 85 (3), 219–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2005.06.018 (2005).

Douglas, C. M. Design and Analysis of Experiments. John Wiley & Sons (2017).

George, E. P., Stuart, J. & B. & Multi-factor experimental designs for exploring response surfaces. Ann. Math. Stat. 28, 195–241 (1957).

Shouliang, Y., Yi, S., Benkun, Q., Zhiguo, S. & Yinhua, W. Application of response surface methodology and central composite rotatable design in optimizing the Preparation conditions of vinyltriethoxysilane modified silicalite/polydimethylsiloxane hybrid pervaporation membranes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 71 (2), 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2009.12.005 (2010).

Somayeh, K. & Ahad, G. Optimization of atmospheric leaching parameters for cadmium and zinc recovery from low-grade waste by response surface methodology (RSM). Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 1490. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52088-2 (2024).

Aditya Ranjan, R., Bankim Chandra, T. & Sujata, M. Leaching of neodymium from hard disk drive magnet waste using citric acid – design of experiments and optimization. ChemistrySelect 9(32), e202402192 https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202402192 (2024).

Arash, A. N., Ashri, W. M., Farouq, W. D., Faisal, S. M., Mohammad Saleh, S. & A. & Production of microporous palm shell based activated carbon for methane adsorption: modeling and optimization using response surface methodology. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 90 (6), 776–784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cherd.2011.10.001 (2012).

Sushanta Kumar, B., Himanshu, M. & Sudipto, C. Application of response surface methodology (RSM) for optimization of leaching parameters for Ash reduction from low-grade coal. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 28 (4), 621–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2018.04.014 (2018).

Rafał, J. et al. Spectroscopic and structural investigations of blue afwillite from ma’ale adummim locality, Palestinian autonomy. Spectrochim Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 227, 117688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2019.117688 (2020).

Thomas, S., Bobby, P. & Boris, M. Monitoring dissolved carbon dioxide and methane in Brine environments at high pressure using IR-ATR spectroscopy. Anal. Methods. 8 (4), 756–762. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5AY02744F (2016).

Ewa, G., Paulina, K. & Janusz, D. The green approach to the synthesis of bio-based thermoplastic polyurethane elastomers with partially bio-based hard blocks. Materials 14 (9), 2334. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14092334 (2021).

Abulikemu, A., Guo-Hai, Y. & Jun-Jie, Z. One-step simple sonochemical fabrication and photocatalytic properties of Cu₂O–rGO composites. Ultrason. Sonochem. 21 (1), 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2013.07.013 (2014).

Li, L. et al. Recovery of Cobalt and lithium from spent lithium ion batteries using organic citric acid as leachant. J. Hazard. Mater. 176 (1–3), 288–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.11.026 (2010).

McDonald, R. G. & Whittington, B. I. Atmospheric acid leaching of nickel laterites review. Part II. Chloride and bio-technologies. Hydrometallurgy 91 (1–4), 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2007.11.010 (2008).

Brown, M. A., Kropf, A. J., Paulenova, A. & Gelis, A. V. Aqueous complexation of citrate with neodymium (III) and americium (III): a study by potentiometry, absorption spectrophotometry, microcalorimetry, and XAFS. Dalton Trans. 43 (17), 6446–6454. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4dt00343h (2014).

Sabrina, F., Marcos, L., Samuel, L. S. O., Luis, R. W. & Tito, F. O. S. Guilherme L., D. Leaching of rare Earth elements from phosphogypsum. Chemosphere 301, 134661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134661 (2022). Jr.

Aditya Ranjan, R., Bankim Chandra, T. & Sujata, M. Leaching of rare Earth elements from phosphogypsum via citric acid medium: optimization through central composite design and kinetics studies. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 32 (7), 4076–4089. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-025-35908-4 (2025).

Joni, N., Manu, L. & Siiri, P. Acetic acid leaching of neodymium magnets and iron separation by simple oxidative precipitation. Clean. Eng. Technol. 10, 100544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clet.2022.100544 (2022).

Clotilde, M., Mapilane, S. & A. & Leaching kinetics and predictive models for elements extraction from copper oxide ore in sulphuric acid. J. Taiwan. Inst. Chem. Eng. 121, 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2021.04.005 (2021).

Abdel-Aal, E. A. & Rashad, M. M. Kinetic study on the leaching of spent nickel oxide catalyst with sulfuric acid. Hydrometallurgy 74 (3–4), 189–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2004.03.005 (2004).

Chul-Joo, K. et al. Leaching kinetics of lanthanum in sulfuric acid from rare Earth element (REE) slag. Hydrometallurgy 146, 133–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2014.04.003 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors (A. R. Ray and S. Mishra) express their gratitude to Siksha ‘O’ Anusandhan (Deemed to be University) for their generous support in facilitating this research work. The author Dr. B. C. Tripathy extends his sincere thanks to IMMT for granting permission to publish this work.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed To Be University)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors Contributions Aditya Ranjan Ray: Conceptualization, Data curation Investigation Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft.Bankim Chandra Tripathy: Formal analysis, Resources, Supervision.Sujata Mishra : Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ray, A.R., Tripathy, B.C. & Mishra, S. Investigation on process optimization and kinetics for leaching of rare earth elements from red mud using citric acid. Sci Rep 15, 36533 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17134-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17134-7