Abstract

Geological storage of carbon dioxide is critical to mitigate emissions; however, subsurface heterogeneity poses a major challenge. This study investigates the Jurassic Plover Formation in the Browse Basin, Northwest Australia, a region underexplored for carbon storage potential. An integrated petrophysical workflow was applied to the Kronos-1 and Poseidon-1 wells, combining borehole logs, petrographic analysis, and core measurements. The workflow included refined porosity–permeability modeling, shale volume estimation, water saturation calibration, and evaluation of top seal capacity under reservoir conditions. Results highlight that intraformational heterogeneity enables diverse trapping mechanisms. Poseidon-1 contains a vertically extensive, quartz-rich reservoir with average porosity of 0.10, permeability of 64.9 mD, and water saturation of 0.27, supporting strong injectivity and both structural and stratigraphic trapping. Kronos-1 exhibits compartmentalized high-quality zones influenced by lithological variability, showing an average porosity of 0.10, water saturation of 0.24, and permeability of 49 mD, favoring localized capillary trapping. Seal evaluation confirms excellent integrity, with column heights exceeding the reservoir thickness. These findings demonstrate how heterogeneity within the Plover Formation governs reservoir quality, injectivity, and seal performance, and directly support Australia’s strategic vision for advancing low-emissions technologies. Future work should integrate additional wells and dynamic modeling to optimize storage design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The intensifying threat of climate change is driving a global transition toward cleaner, low carbon energy futures1. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is facilitating that shift toward low or zero–carbon economies2,3,4. CCS refers to the process of isolating CO₂ emissions and storing them underground in formations like depleted reservoirs or saline aquifers5,6,7.

The long–term containment of CO₂ in storage sites is governed by a suite of geological trapping mechanisms. Solubility trapping facilitates the gradual dissolution of CO₂ into formation fluids, while residual trapping immobilizes CO₂ within pore spaces through capillary forces. Mineral trapping facilitates permanent CO₂ sequestration by promoting geochemical reactions that convert CO₂ into stable carbonate minerals; however, this process typically occurs over geological timescales. Structural and stratigraphic trapping physically isolate CO₂ beneath impermeable caprocks, providing an essential barrier to vertical migration8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. The security of geological CO₂ storage is governed by a set of reservoir and seal characteristics. Effective physical trapping requires sufficient storage capacity, favorable flow properties, and the structural integrity of the caprock to prevent leakage. In parallel, the mineralogical composition of the reservoir critically influences the potential for CO₂ mineralization and contributes to the long–term geochemical stability of the storage system16,17,18,19.

An integrated petrophysical analysis is essential for accurately evaluating reservoir quality, since heterogeneity in mineralogy and pore structure strongly influences storage potential20,21,22,23. Accordingly, the Poseidon area in the Browse Basin, an offshore hydrocarbon–rich region in northwestern Australia (Fig. 1)24,25 was investigated in this study to evaluate its potential for CO₂ storage. Stratigraphically, the Plover Formation is divided into a volcanic unit and a lithologically complex underlying reservoir interval. This study applies a comprehensive petrophysical assessment to characterize the reservoir’s storage capacity and sealing properties.

Previous studies in the Petrel Sub–basin of the adjacent Bonaparte Basin have demonstrated the suitability of the Plover Formation for geological CO₂ storage31,32,33. This study investigates whether the Plover Formation in the Browse Basin exhibits a comparable CO₂ storage potential. The outcomes of this study aim to inform the development of scalable CO₂ storage strategies that support long–term decarbonization pathways and reinforces the transition to cleaner and sustainable energy landscape.

Geological overview

The Browse Basin, located offshore on the Northwest Shelf (NWS) of Australia, is a northeast–southwest trending passive continental margin basin that spans an extensive offshore area of approximately 140,000 km² (Fig. 1)24,25,26,34,35,36. Structurally, the basin is interpreted as a margin–parallel half–graben depocenter, developed through complex, multi–phase tectonics and containing up to ~ 15 km of Paleozoic to Cenozoic sedimentary fill (Fig. 2)26. The basin is geographically framed by several structural heights and adjacent basins; it lies between the Scott Plateau and Argo Abyssal Plain to the northwest and the Kimberley Block to the southeast. Surrounding structural elements include the Yampi–Leveque Shelf to the southeast, the Rowley Sub–basin of the Roebuck Basin to the southwest, and the Vulcan Sub–basin of the Bonaparte Basin to the northeast25,34.

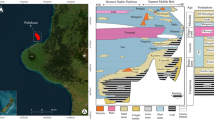

Tectonostratigraphically, six major phases of basin evolution have been identified (Fig. 3). Basin initiation in the Late Carboniferous to Early Permian, likely related to the rifting of Sibumasu from the northwestern Australian margin. The earliest sedimentary sequences include undifferentiated clastics of the Weather and Kulshill Groups, transitioning upward into the Kinmore Group and the Mt Goodwin Subgroup of the Hyland Bay Subgroup in the Early Permian. These units record a shift from fluvio–deltaic to marine environments during early extension26. The Triassic sequence reflects post–orogenic thermal subsidence and widespread sedimentation. The Sahul Group includes the Osprey, Pollard, and Challis Formations, along with the Nome Formation, representing coastal to shallow marine deposits with interbedded sandstones, shales, and siltstones36,37. Mild tectonic inversion during the Late Triassic introduced subtle structuring that controlled subsequent Jurassic deposition28.

The Early to Middle Jurassic was dominated by rifting and normal faulting, especially within the northeastern Caswell Sub–basin and along the Prudhoe Terrace. This phase resulted in deposition of the Plover Formation, part of the Troughton Group, which includes sandstones, shales, siltstones, minor carbonates, and volcanics (e.g., Ashmore Volcanics). Overlying the Plover, the Montara Formation and Vulcan Formation of the Swan Group represent marine transgressive sequences25,28. The Plover Formation is the key reservoir unit, with proven hydrocarbon potential in fields such as Ichthys, Brecknock, and Calliance.

Thermal subsidence continued in the Cretaceous, resulting in thick marine sedimentation. The Echuca Shoals of the Lower Cretaceous marks a widespread transgressive marine mudstone, forming a regional seal above the Jurassic reservoirs. Overlying formations within the Bathurst Island Group include the Woolaston, Gibson, Fenelon, Jamieson, and Heywood Formations, indicating a progression from shallow marine to more distal shelf environments. These units reflect ongoing eustatic sea–level fluctuations and depositional changes across the basin28,38. In the Upper Cretaceous, marine shales of the Puffin and Bassett Formations, along with the Johnson Formation, provided further sealing and potential source rock intervals, strengthening the petroleum system37,39.

The Cenozoic post–rift phase was marked by regional thermal subsidence, episodic tectonic reactivation, and the development of carbonate platforms. The Paleogene Woodbine Group, including the Cartier and Oliver Formations, along with undifferentiated carbonates, records initial carbonate ramp deposition. The Barracouta Shoals Formation of the Neogene reflects the transition to rimmed tropical platforms with barrier reef development before drowning during the Tortonian40,41. Tectonic inversion in the Miocene, due to convergence with Southeast Asia and subduction in the Timor Trough, reactivated Jurassic fault systems, especially along the Barcoo Fault Zone and Scott Reef Trend42,43. These structures facilitated vertical hydrocarbon migration, evidenced by features such as pockmarks, DHIs, and shallow gas anomalies44,45,46. From the Late Miocene to the present, hemipelagic sedimentation continued across the basin, influenced by regional oceanographic changes, including intensification of the Indonesian Throughflow, which contributed to carbonate platform drowning and reduced productivity47,48,49.

Simplified stratigraphic framework of the Browse Basin34.

Dataset and methods

Dataset

This study utilizes subsurface data acquired from two exploratory wells, Poseidon–1 and Kronos–1, drilled in the Poseidon area, offshore northwest Australia. The processed data were obtained from the publicly available ConocoPhillips archive, including well reports, wireline logs, and core measurements25. Available borehole logs comprise caliper (CAI), bit size (BS), bulk density correction (DRHO), natural gamma ray (GR), uranium corrected natural gamma ray (UCGR), deep resistivity (RD), bulk density (RHOB), neutron porosity (NPHI) and photoelectric absorption factor (PEF), along with advanced logs such as Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) and Elemental Capture Spectroscopy (ECS). Core data include Routine Core Analysis (RCA) parameters such as porosity (CPOR), permeability (CPerm), grain density (CGD), water saturation (CSW) and Special Core Analysis (SCAL) from mercury injection capillary pressure (MICP) test. Additional datasets include petrographic thin section descriptions and X–ray Diffraction (XRD). All data were integrated into the Schlumberger’s Techlog environment in standardized, quality–checked formats ensuring compatibility and reliability for subsequent analysis.

Methods

Lithology and shale content distribution

The petrophysical evaluation of the Plover Formation initiated with shale volume (Vsh) estimation (Fig. 4). Drilling records and cuttings analysis indicate that the formation exhibits a heterogeneous lithological composition, comprising interbedded siliciclastic, carbonate, and volcanic units25. Given this complexity, the Neutron–Density cross–plot technique (ND) was chosen over the GR–method for Vsh estimation (Eq. 1)50,51.

In Eq. 1, parameters ρf, ρsh, and ρma represent the densities of the fluid, shale, and matrix, respectively, with ρb referring to the measured bulk density (g/cm³). Neutron–porosity (NPHI) is provided as a volumetric fraction (v/v), where NPHIfl., NPHIsh, and NPHIma correspond to the neutron–porosity contributions of the fluid, shale, and matrix components.

The ND–approach offers improved sensitivity in identifying reservoir intervals within mixed lithologies. Conversely, GR readings may be affected by the presence of radioactive minerals which can result in overestimation of Vsh, especially in sections enriched with volcanic or carbonate materials50,51. Although the ND–method can produce misleading results in non–reservoir intervals where tight carbonate or volcanic layers may be misinterpreted as shale, it is generally more reliable for delineating porous, reservoir zones. To support and validate the Vsh estimates, the UCGR method was applied, as it excludes the uranium response and reduces overestimation in intervals enriched with radioactive minerals51.

Clay volume was evaluated using ECS logs, calibrated against mineralogical data from XRD and petrographic descriptions. Given that ECS outputs are reported on a dry weight basis, values were converted to wet volume fractions using porosity data from core measurements and log-derived profiles. While the initial Vsh estimate includes both clay and silt fractions, the ECS and petrographic methods specifically quantify clay content. Therefore, interpretations in this section are based on clay volume to maintain consistency with these datasets. This integrated approach enables more accurate, cross-validated delineation of clay-rich intervals, enhancing the reliability of petrophysical evaluation in the heterogeneous Plover Formation.

Porosity estimation

Porosity (ϕ) was initially derived from the environmentally corrected formation density log, (Eq. 2)

In Eq. 2, the porosity derived from the density log is given in volume fraction (v/v). Before Prior to applying this method, core–to–log consistency was checked to ensure the reliability of density–based porosity estimates. Core–derived bulk density was calculated using core grain density and core porosity as follows

In Eq. 3, CPOR refers to core porosity expressed as volumetric fraction (v/v), CGD is the core grain density (g/cm³), and CBD denotes the reconstructed core bulk density (g/cm³)52.

The reconstructed core bulk density (CBD) was systematically compared against the well log derived bulk density to assess interval–scale consistency and validate agreement between core and wireline measurements. Grain density from RCA was used to calibrate matrix density derived from the ECS log, enhancing the subsequent porosity computations. ρf was approximated through regression analysis using a cross–plot of core porosity (x–axis) against log–derived bulk density (y–axis), restricted to minimal Vsh intervals. A best–fit linear regression line was applied and constrained at zero porosity to intersect the mean matrix density.

Fluid density was estimated from the y–intercept of the fitted trend line corresponding to the 100% porosity condition. Given the gas–bearing characteristics of the Formation, a composite porosity approach was applied to enhance the reliability of porosity determination50. An empirical combination of NPHI and RHOB logs was applied to calculate porosity as outlined below

This combined approach compensates for the opposing biases of neutron and density logs in gas–bearing formations, where the neutron tool typically underestimates porosity and the density tool tends to overestimate it. The resulting porosity estimates were calibrated against gas–corrected NMR total porosity log provided in the dataset. This revised method was implemented in place of the operator’s classical approach to better account for the gas–bearing conditions of the formation.

Fluid saturation calculation

Water saturation (Sw) was determined using Archie’s Eq. 53. Although the Plover Formation presents a complex lithological assemblage, it exhibits low clay content. Therefore, the use of shaly–sand models such as Simandoux or Waxman–Smits unnecessary50,51. The Archie’s formula applied in this study is as follows

where Rt refers to the true formation resistivity (Ωm), and Rw is the resistivity of formation water (Ωm). The variable ϕ denotes effective porosity (v/v), while the empirical constants include the tortuosity factor (a), the cementation exponent (m), and the saturation exponent (n); all are dimensionless and typically derived through calibration against SCAL acquired under reservoir–representative stress conditions. Rw was not directly measured in this study. Instead, values were sourced from the formation evaluation reports provided by the operator. In both studied wells, the operator assumed a regional average salinity of 17,000 ppm NaCl equivalent. Using this salinity and the corresponding bottom–hole temperature (BHT) data, Rw was estimated.

Digitized MICP data were used to estimate irreducible water saturation (Sw, irr), a critical constraint during saturation modeling, preventing the generation of non–physical outcomes. Water saturation was subsequently calculated using Archie’s equation, incorporating the revised porosity estimates developed in this study and further validated through comparison with RCA measurements reinforcing the accuracy of the interpretation.

Permeability modeling

Permeability (K) was derived using empirical relationships derived from core porosity (CPOR) and permeability (CPerm) measurements. As a reference, the operator initially applied a dual–function model that utilized distinct equations for low and high porosity ranges, defined by a porosity threshold of 0.075. The formulations were as follows

To enhance the estimation accuracy, a custom dual–function model was developed based on a detailed cross–plot analysis of core data with logarithmic scaling to capture the full data range (Fig. 5). Data density visualization was employed to emphasize statistically representative clusters, suppress the impact of outliers and ensure that the fitted relationships reflected dominant trends in the dataset.

Two distinct porosity domains were identified: a linear correlation for samples with porosity below 0.09, and a nonlinear trend for samples exceeding this threshold. The following equations were derived to represent these porosity regimes

The predicted permeability was subsequently calibrated against core measurements, NMR–derived estimates, and the operator’s original dual–function model to validate the estimation result.

Reservoir evaluation and net–pay calculation

Cut–off sensitivity analysis was performed to quantify the effective storage potential of the Plover Formation, using Vsh, ϕ, and Sw as key petrophysical discriminators of reservoir quality. This approach involved systematically evaluating how variations in these parameters influence the delineation of net reservoir characteristics, particularly their effect on hydrocarbon pore volume distribution. By iteratively adjusting the cut–offs, the sensitivity of net–to–gross (NTG), net reservoir, and net pay intervals to each parameter was assessed. The final thresholds were applied to derive consistent reservoir metrics for subsequent volumetric and dynamic flow assessment.

Seal capacity and CO₂ column height calculation

The sealing capacity of the upper clay rich interval within the reservoir unit was quantified by calculating the maximum supercritical CO₂ column height retained prior to capillary breakthrough. Column heights were estimated from the measured entry pressures and three saturation thresholds (5%, 7.5%, and 10%) to capture a range of possible sealing scenarios. MICP tests was obtained under an air–mercury system. A fluid substitution correction was applied to account for the contrast in interfacial tension and wettability between laboratory and in–situ CO₂–brine conditions53,54. The corrected capillary pressure denoted Pc, Co2 was computed as follows

where γair/hg and γCO2/brine are the interfacial tensions of the air–mercury and CO₂–brine systems, respectively (N/m), and cos βair/hg and cos βCO2/brine represent the respective contact angles with the rock surface in radians. Quantity Pc, air/hg denotes the capillary pressure measured under laboratory air mercury conditions (psi).

According to Daniel and Kaldi53\(\:{{\:{\upbeta\:}}_{\text{a}\text{i}\text{r}\text{}\:/\:\text{h}\text{g}}\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:{\upgamma\:}}_{\:\text{a}\text{i}\text{r}\:\text{}/\:\text{h}\text{g}\:}\) were set at 140° and 481 mN/m, respectively. For the CO₂ brine system, interfacial tension values typically range between 21 and 27 mN/m. In this study, a representative value of 24 mN/m was applied. A contact angle of 0° was assumed to reflect a water–wet reservoir condition. These parameters were applied to correct capillary pressure data to subsurface conditions relevant for CO₂ storage. The corresponding CO₂ column height above the water level, HC, was calculated by the buoyancy–based capillary entry pressure Eq.

where HC represents the CO₂ column height (m), ρw and ρCO2 denote the density of brine and supercritical CO₂, respectively, expressed in (kg/m³). The pressure gradient of water due to gravity (g) is taken as 0.433 psi/ft. For these calculations, supercritical CO₂ density (0.42–0.74 g/cm³) and brine density (0.97–1.05 g/cm³) were considered, with average values of 0.58 g/cm³ and 1.01 g/cm³ used respectively55,56. Breakthrough pressure (Pb), was determined from the capillary pressure curve as the inflection point associated with a marked increase in mercury saturation. The corresponding value, adjusted for CO₂ brine conditions, was interpreted as the threshold pressure governing capillary entry and vertical migration potential

In Eq. 12, Pb is the break through pressure in the seal and Hmax is the maximum supercritical CO₂ column height. This calculation provied a critical measure of the caprock’s integrity and its suitability for long–term CO₂ storage applications.

Results

Lithological characteristics of plover formation

The Plover Formation comprises interbedded sandstones and mudstones arranged in successive coarsening-upward cycles (Fig. 6). The sandstones exhibit both blocky- and bell-shaped gamma-ray log motifs, characterized by sharp basal and upper contacts. These log signatures, together with the abrupt bounding surfaces, are indicative of deposition within channelized settings, representing either discrete in-channel deposits or amalgamated channel-fill bar complexes. The ND cross–plot method demonstrated high efficiency in differentiating reservoir–quality sandstones from non–reservoir facies. In the Kronos–1 well, key sandstone–bearing intervals were identified between approximately 5000 m and 5050 m. Beyond these zones, the ND cross–plot consistently indicated shale–dominated intervals (Fig. 6).

Sandstone intervals show strong agreement across all independent measurement techniques. Vsh estimates from ND and UCGR methods are internally consistent and align closely with the quartz–dominated mineralogy confirmed by point–count analysis. ECS–derived clay volume is similarly low in these zones, with only sporadic carbonate occurrences. A pronounced ND crossover is observed only in the upper sandstone segment. Apart from these intervals, inconsistencies are observed: ND–derived Vsh tends to be higher than UCGR estimates, while ECS data reflect elevated clay content accompanied by variable carbonate and siderite signatures. These responses diverge notably from point–count analysis, which consistently confirms quartz as the dominant framework mineral, with only moderate contributions from carbonate and minimal clay content (Fig. 6).

The ND cross–plot in Kronos–1 (Fig. 7a) exhibits a well–defined cluster of data points aligned with the sandstone trendline, with slight dispersion toward lower RHOB and NPHI values, is corresponding to porosity range between 0.14 and 0.24 v/v. Additional, groupings appear near the limestone and dolomite trendlines, with mostly low to moderate GR values. A few outliers are distributed across the plot. The PE factor versus RHOB cross–plot (Fig. 7b) shows most points between the sandstone and dolomite trendlines, with PE values range from approximately 2.5 to 3.5 barn/e and RHOB values from 2.3 to 2.7 g/cm³. A separate cluster, trending toward the limestone trendline, with elevated PE values (3.5–4.5 barn/e) and moderate GR readings. Additionally, a few isolated points show very high PE values (> 5.0 barn/e), moderate RHOB (2.35–2.55 g/cm³) and low to moderate GR.

Petrophysical and mineralogical analysis of Poseidon–1 well indicates a more homogeneous reservoir character than the lithologically variable Kronos–1. The 4955–5079 m interval shows a predominantly clean reservoir, with minor shale interbeds sporadically distributed throughout. Vsh estimates from ND and GR method are consistently low, with GR values slightly higher. XRD data confirm quartz dominance in low Vsh zones, with minimal clay and carbonate content. In intervals with slightly elevated Vsh, XRD indicate modest carbonate increase, while clay concentrations remain low (Fig. 8).

The ND cross–plot for Poseidon–1 (Fig. 9a) shows a tight cluster of data points along the sandstone trendline, with minimal dispersion toward the dolomite and limestone regions. Within this cluster, a subtle shift toward lower RHOB values is observed. GR color scale reveals internal variation: most data points display low GR values and correspond to an average porosity of ~ 0.12 v/v, whereas a smaller subset shows moderate to high GR. The PEF–RHOB cross-plot (Fig. 9b) similarly shows most points cluster around the sandstone field, with PEF values between 1.0 and 1.5 barn/e and RHOB from 2.3 to 2.8 g/cm³. GR responses are mostly low to moderate, indicating compositional consistency. A few points extend slightly towards the dolomite and limestone trendlines, with no significant clustering in those regions.

Storage capacity of plover formation

Initial porosity within the Plover Formation was computed from RHOB logs, employing a ρma calibrated using CGD and ECS measurements. Comparisons between CBD and RHOB log revealed a strong consistency (Fig. 10). In the upper cored interval (5020–5030 m), RHOB values ranged from 2.35 to 2.55 g/cm³, closely matching core data. In contrast, the lower section, especially above 5050 m, exhibited higher RHOB values and greater variability, while CGD remained stable around 2.65 g/cm³. ECS derived ρma values were cross-validated with CGD, showing strong agreement in the upper reservoir and slight deviation in the lower interval (Fig. 10). The ECS–based ρma was ultimately used for porosity estimation.

Quantity ρf was determined by applying a linear regression to a cross-plot of CPOR and RHOB within of low Vsh intervals. The regression line was constrained to intersect ρm at 0% ϕ and ρf at 100% ϕ. This method allowed the extrapolation of ρf, at approximately 0.85 g/cm³ (Fig. 11).

CPOR plotted against \(\:{{\upvarphi\:}}_{\text{D}}\) shows moderate overestimation (0.05-0.20v/v) with a correlation coefficient (r) of 0.54 (Fig. 12a). The QLS method showed the best match with core data (r = 0.62), with values clustered between 0.05 and 0.15 v/v along the y = x line (Fig. 12b). The operator’s ND averaging method shows similar clustering and moderate correlation (r = 0.59) (Fig. 11c). NMR-derived total porosity, calibrated to core data, mostly ranged from 0.05 to 0.20 v/v, with some values exceeding 0.20. The cross-plot (Fig. 12d) shows a positive correlation (r = 0.55), indicating good agreement with core porosity. NMR porosity also aligns closely with QLS-derived values (0.05–0.15 v/v) and shows minimal scatter (Fig. 12e).

Porosity histograms (Fig. 13) show most values between 0.04 and 0.16 v/v, peaking at 0.06–0.08 v/v. \(\:{{\upvarphi\:}}_{\text{D}}\) had the widest range, while CPOR was narrower and more symmetric. QLS and ND methods were intermediate, with QLS showing better alignment with core data. For Poseidon–1, porosity was estimated using the modified QLS method, which showed better agreement with NMR data than the operator’s density-based estimate (Fig. 14).

Fluid saturation analysis

Quantity Sw in the Kronos–1 was determined using Archie’s equation, calibrated with SCAL parameters including cementation exponent (m) of 1.92, saturation exponent (n) of 1.80, and tortuosity factor (a) of 1.0. Formation water resistivity (Rw) of 0.08 Ω·m was used, corresponding to 17,000 ppm NaCl at 180 °C, in line with operator data. Irreducible water saturation (Sw, irr) was estimated at ~ 0.08 based on MICP data under air–brine conditions (Fig. 15). In Poseidon–1, core data were not available for calibration; therefore, standard Archie’s parameters were used: a = 1, m = 2, and n = 2. The Rw was set at 0.09 Ω·m, corresponding to the same formation water salinity.

In Kronos–1 well, Sw varies notably across the Plover Formation (Fig. 16). The upper reservoir zone (~ 5000–5016 m), shows low Sw values (< 0.3), coinciding with moderate–high porosity, low Vsh, elevated NMR porosity and strong free fluid signal. Between 5020 and 5030 m, Sw remains low (0.05–0.19 v/v) despite slight increase in RHOB and Vsh, supported by relatively high NMR porosity and free fluid index. 5030 m to ~ 5060 m, Sw increases gradually, often exceeding 0.6, corresponding to reduced effective porosity, higher Vsh, and declining NMR responses. Sw values from logs and core data generally align well between 5020 and 5030 m but diverge below 5030 m. The mismatch is most evident from 5039 to 5050 m, where core and log-derived Sw differ markedly (Fig. 16). Fluid distribution in Kronos–1 shows distinct vertical variation, reflected by RD values and ND porosity separation. In the upper interval (5000–5007 m), resistivity exceeds 500 Ω·m, with pronounced ND separation—density porosity reads notably lower than NPHI. In contrast, the 5020–5030 m interval shows reduced RD(150–250 Ω·m) and a gradual convergence of the porosity curves.

In Poseidon–1, Sw remains uniformly low across the Plover Formation (4974–5060 m), with most values falling below 0.2 (Fig. 17). This corresponds to consistently elevated porosity readings (> 0.10) throughout the interval. Slight Sw increases occur at thin shale interbeds, which are identifiable by subtle log variations. Low Sw is further supported by elevated RD readings, often exceeding 500 Ω·m, with notable decreases only at shale-rich depths. In Poseidon–1, RHOB remains low across the main reservoir interval, consistent with the overall low Sw trend. Localized RHOB increases, along with slight Sw elevations, are associated with thin shale-rich interbeds within the sequence.

Permeability modeling

Quantity K in the Plover Formation was estimated using a modified dual–function model calibrated from CPOR and CPerm. Unlike the operator’s model, with a fixed CPOR breakpoint at 0.075, the proposed model uses a 0.09 threshold to separate a linear trend at low CPOR from a logarithmic trend at higher values. The modified model (Fig. 18a) shows better agreement with core measurements than the operator’s model (Fig. 18b), evidenced by the tighter clustering around the identity line. Correlation between CPerm and NMR permeability confirmed the reliability of the NMR dataset (Fig. 18c) and supported its use for validating log–derived K. The comparison between NMR and log-derived K also shows good agreement, reinforcing the robustness of the modified model (Fig. 18d).

In Kronos–1, K is highly heterogeneity with limited vertical continuity, confined to clean sandstone intervals (Fig. 16). Elevated K values occur where average ϕ exceeds 0.09, Vsh is below 0.2, and Sw is less than 0.2. Conversely, higher Vsh and Sw correlate with reduced K (Fig. 16). In Poseidon–1, K profile shows more vertically continuous high–K zone, typically associated with porosity between 0.09 and 0.12, low Vsh, and moderate Sw (Fig. 17).

Reservoir summary and net–pay evaluation

Cut–off sensitivity analysis was applied to define net reservoir and pay intervals within the Plover Formation, using revised thresholds based on newly derived ϕ, Vsh and Sw values. Unlike the operator’s fixed cut–off criteria (Vsh< 0.40, ϕ > 0.05, and Sw < 0.70), this study applied well specific thresholds. In Kronos–1, cut-offs of Vsh < 0.44, ϕ > 0.03, and Sw < 0.68 yielded a net reservoir thickness of 51.22 m (average ϕ = 0.10, Vsh = 0.20, Sw = 0.28), and a net pay of 46.25 m with slightly improved properties (ϕ = 0.10, Vsh = 0.19, Sw = 0.25) (Fig. 19) (Table 1).

In Poseidon–1, a higher Vsh cut-off (< 0.56) was required, while ϕ (> 0.03) and Sw (< 0.68) remained similar. The resulting net reservoir was 174.91 m (ϕ = 0.09, Vsh = 0.14, Sw = 0.41), and the net pay measured 121.55 m (ϕ = 0.103, Vsh = 0.08, Sw = 0.27) (Table 1). Quantity K was also applied as a filter to further exclude low–K intervals. In Kronos–1, the average K in the net pay interval was 45.5 mD versus 29.8 mD from the operator. In Poseidon–1, average K reached 64.9 mD, though no operator values were available for comparison.

.

Seal capacity and column height calculation

MICP analysis of two top–seal claystone samples revealed distinct capillary behavior. Sample A recorded a Pb of ~ 800 psi, corresponding to a CO₂ Hmax of 1092 m. At saturation thresholds of 5%, 7.5%, and 10%, Hmax increased to 1837 m, 2275 m, and 2757 m, respectively. Sample B exhibited a higher Pb of 946 psi, yielding a CO₂ Hmax of 1282 m under conservative conditions, increasing to 2178 m, 2832 m, and 3484 m at the same saturation levels (Fig. 20).

MICP profiles provide insight into pore throat architecture, showing progressive intrusion pattern into finer pores with increasing pressure. Both samples have dominant pore throat sizes are mostly below 0.3 μm and critical pore throat size under 0.01 μm. K is extremely low, measured at 0.0013 mD for Sample B and 0.0062 mD for Sample A, consistent with the fine pore structure. Incremental intrusion curves show broad, non-peaked distributions, reflecting heterogeneity in pore throat sizes (Fig. 21).

Discussion

Lithological controls on reservoir quality

Lithological heterogeneity is widely recognized as a key challenge in deriving accurate reservoir properties from well logs57,58,59. This complexity is evident in Kronos–1, where discrepancies between ND and UCGR Vsh highlight the influence of uranium content. Even after correction, carbonate and volcanic lithologies continue to affect gamma-ray responses, limiting Vsh reliability in non-reservoir facies. Despite these limitations, Vsh calculation remains essential for effective porosity (ϕeff) estimation.

Cross–plot analyses highlight the internal heterogeneity of the reservoir unit. The ND cross–plot confirms the sandstone lithology in sandy intervals. While clusters near dolomite and limestone trendlines indicate localized carbonate interbeds (Fig. 7a). RHOB variations within the sandstone indicate intra-sandstone heterogeneity, influencing fluid distribution —gas in the upper part and condensate in the lower, as observed in similar geological contexts60,61,62. Outliers, due to poor borehole conditions, emphasize the need for rigorous quality control. The PEF-RHOB cross-plot (Fig. 7b) further highlights lithological heterogeneity, showing a sandstone-dominated reservoir with carbonates interbeds. Moderate GR imply minimal clay, while high PEF and moderate RHOB values indicate volcanic influence rather than true clay-rich lithologies, as supported by literature60,61,62.

In Kronos–1, petrographic point-copunting and ECS data confirm quartz-rich sandstones with minor illite, mica, and carbonates (Fig. 6). Discrepancies between petrography and log are attributed to broader sensitivity of logs to fine grained material, leading to overestimated clay content in complex zones60,61,62. Poseidon–1 by contrast, shows a cleaner, more homogeneous reservoir with limited carbonate and clay development, supporting the interpretation of a more uniform reservoir fabric and stronger gas effect relative to Kronos–1 (Fig. 9).

Petrophysical influence on reservoir behavior

Petrophysical analysis is widely recognized as a key constraint on reservoir performance63,64,65. In Korons–1, strong agreement between core and log data in the 5020–5030 m interval indicates good reservoir quality (Fig. 10). This is supported by low RHOB, clear ND crossover, and low Vsh from the UCGR method (Fig. 6). Below 5030 m, increasing heterogeneity reduces consistency. Quantity ϕ estimation highlights the utility of the QLS method in the gas bearing plover formation. Density-derived ϕ tends to be overestimated due to gas lowering RHOB, while lithological heterogeneity affects ρma and porosity response. ECS-calibrated ρma improved ϕ estimates, and ρf (~ 0.85 g/cm³, Fig. 11) suggests a gas-dominated system, likely influencing log responses50,65,66. Integrating NPHI, the QLS method compensates for this bias60,61,62and shows a stronger correlation with CPOR (Fig. 12b). While the operator’s classical ND averaging method also showed positive correlation with CPOR, its equal weighting of NPHI and \(\:{{\upvarphi\:}}_{\text{D}}\) may not sufficiently correct for gas–related distortions or lithological variability.

NMR–derived ϕ provides an independent benchmark that reinforces the reliability of the QLS method. The consistency between NMR and QLS derived ϕ in sandstone intervals supports the reliability of both methods (Fig. 12e). However, NMR accuracy may be compromised in suboptimal borehole conditions, requiring careful quality control during interpretation50,62. Histogram analysis highlights the sensitivities of each method to formation conditions. ϕD shows a broader, higher range, reflecting overestimation due to gas and lithological effects. In contrast, QLS more closely matches core values, indicating better handling of such complexities (Fig. 13). This alignment enhances reservoir characterization, enabling better predictions of storage capacity and flow performance.

Quantity Sw variations reflect the interplay of lithology, porosity, and fluid composition50,62. In Kronos–1, low Sw in the upper reservoir (~ 5000–5016 m) corresponds with moderate ϕ, low Vsh, and elevated NMR porosity and free fluid index, indicating good reservoir quality (Fig. 16). Between 5020 and 5030 m, hydrocarbon potential persists but with slightly reduced quality. Below 5030 m, rising Sw, decreasing ϕ, and higher Vsh suggest increased heterogeneity and declining quality (Fig. 16). Fluid distribution trends further confirm this vertical heterogeneity. High RD (> 500 Ω·m) and pronounced ND crossover in the upper section indicate gas presence, while moderate RD (150–250 Ω·m) and minimal ND separation in the 5020–5030 m interval suggest a transition to condensate-bearing zones50,53. The variation in correlation between log–derived Sw and core–measured Sw across the Kronos–1 reservoir highlights both formation heterogeneity and petrophysical modeling (Fig. 16). A good match in the 5020–5030 m interval suggests well-calibrated models and relatively homogeneous reservoir properties. In contrast, the 5030–5050 m section, particularly 5038–5050 m, shows growing discrepancies—likely due to increased lithological complexity and suboptimal borehole conditions affecting log reliability. In Poseidon–1, Sw remains consistently low across the reservoir, indicating strong hydrocarbon presence and moderate to high ϕ (Fig. 17). Minor Sw increases from shale interbeds have limited effect, as shown by strong agreement between log- and NMR-derived ϕ. Minimal CAL variation confirms good borehole conditions, reinforcing confidence in the accuracy of NMR-based estimates (Fig. 17).

Permeability is governed by lithological and petrophysical characteristics that shape pore structure and connectivity67,68,69. The modified dual–function model improves alignment with CPerm, better reflecting flow capacity (Fig. 18). Capturing the shift from linear to nonlinear trends is essential in heterogeneous lithologies, where conventional models fall short70. This approach enhances K estimation by distinguishing variable flow behaviors within the formation. In Kronos–1, permeability (K) is highly variable and compartmentalized, reflecting heterogeneity and limited vertical connectivity, especially in shale-prone zones (Fig. 16). High K aligns with localized low Vsh and high ϕ. In contrast, Poseidon–1 shows more continuous K distribution, supported by broader zones of low Vsh and moderate ϕ (Fig. 17), indicating better vertical flow and reservoir uniformity. These differences highlight the importance of well-specific petrophysical calibration to capture reservoir complexity. Future work has to integrate rock typing to link these permeability trends with specific lithofacies–microfacies associations, thereby refining the understanding of how mineralogy and pore geometry control flow and improving the predictive accuracy of permeability models.

Cut–off sensitivity analysis is essential for defining net reservoir and pay zones62,71. In the Plover Formation, results show clear differences between Poseidon–1 and Kronos–1. Poseidon–1 has a thicker and more continuous reservoir interval with low Vsh, indicating a uniform siliciclastic system. Despite slightly lower average ϕ and higher Sw, reservoir quality remains preserved due to minimal argillaceous input. In contrast, Kronos–1 shows higher ϕ but reduced thickness and greater heterogeneity, with elevated Vsh suggesting localized development. However, its lower Sw values reflect cleaner sands and more favorable saturation. Overall, Poseidon–1 exhibits better vertical continuity, while Kronos–1 offers higher-quality reservoir conditions within more confined zones.

Capillary sealing and containment potential

Seal efficiency is critical for assessing caprock integrity and its capacity to retain subsurface fluids72,73,74. MICP-derived CO₂ column height estimates from the Plover Formation show distinct seal performance variations across saturation thresholds. Conservative Pb-based estimates offer higher confidence, while higher saturation thresholds yield more optimistic projections, reflecting sensitivity to pressure and fluid distribution75,76. Sample B consistently exhibits greater sealing capacity than Sample A, supported by its higher Pb (946 psi), lower permeability (0.0013 mD), and reduced incremental intrusion (Figs. 20 and 21b). Both samples show dominant pore throat sizes < 0.3 μm and critical pore throats < 0.01 μm, placing them in the capillary-bound flow unit class per Pittman (1992). These features indicate tight pore structures and high sealing efficiency across both samples77,78,79.

Implications for CO₂ storage feasibility

Petrophysical evaluation of the Plover Formation in the Browse Basin indicates strong CO₂ storage potential. Both Kronos–1 and Poseidon–1 wells are dominated by quartz-rich sandstones, but Poseidon–1 shows greater lithological homogeneity, with minimal clay and carbonate interbeds. This clean siliciclastic fabric corresponds to moderate ϕ (0.103), high K (89.9 mD), and low Sw (0.27), with a thick net pay interval of 121.55 m—parameters indicative of favorable for structural and stratigraphic trapping, consistent with the mechanisms discussed in previous studies79,80,81. The unit’s vertical continuity enhances pore connectivity and supports stable CO₂ migration and immobilization. While capillary trapping is limited due to low heterogeneity, minor clay and carbonate layers promote stratigraphic trapping by acting as vertical flow barriers, aiding pressure dissipation and long-term storage security. Kronos–1 displays higher heterogeneity with volcanic and carbonate interbeds, confining reservoir quality to localized zones. It has a thinner net pay (46.25 m) but maintains good ϕ (0.10 v/v), moderate K (45.8 mD), and low Sw (0.25). The heterogeneity may restrict CO₂ plume migration but supports selective injection strategies. Volcanic and carbonate layers could enhance stratigraphic and mineral trapping through geochemical interaction, depending on their reactivity and pore structure, as supported by mechanisms discussed in prior studies82,83,84,85,86. Additionally, fine-scale lithological variation may promote capillary trapping by immobilizing CO₂ in low-permeability zones11,87,88,89,90,91. Given these characteristics, Poseidon–1 supports broad injection, whereas Kronos–1 favors localized CO₂ storage with close monitoring.

In terms of storage integrity, Poseidon–1, shows calculated Hc significantly exceed the net pay interval across all saturation scenarios. This indicates strong sealing capacity, minimizing vertical leakage risk and allowing flexible plume management and storage design. However, injection performance can still be affected by reservoir-scale processes. Residual gas saturation may reduce CO₂ mobility and raise injection pressures, while interactions with carbonates or volcanics could further limit injectivity. Strong seal integrity helps manage these risks by containing pressure buildup, and operational techniques like Water Alternating Gas (WAG) injection or pressure pulsing can mitigate these risks11,83,89.

Conclusions

This study aimed to evaluate the CO₂ storage potential of the Plover Formation using an integrated petrophysical approach applied to the Kronos–1 and Poseidon–1 wells in the Browse Basin. Results highlight significant heterogeneity in reservoir quality, permeability distribution, and sealing capacity. Poseidon–1 exhibits a more vertically extensive and homogeneous reservoir interval, whereas Kronos–1 is characterized by compartmentalized intervals due to lithological variability. The integration of core-calibrated petrophysics, a newly developed dual-function permeability model, and MICP-based seal analysis adapted for CO₂–brine conditions emphasizes the critical role of formation-scale variability in determining injectivity and containment. The incorporation of QLS-calibrated porosity estimations further improves the reliability of the petrophysical model. These insights support the development of tailored injection strategies aimed at enhancing plume control and pressure management. Strong capillary seal capacity, in Poseidon–1, reinforces containment confidence. Despite limitations arising from well data resolution and the absence of seismic constraints, the methodology adopted here is well-suited for early-stage screening of CO₂ storage sites. Overall, this study presents a robust, field-calibrated framework for assessing CO₂ storage potential in data-limited offshore basins, bridging the gap between static characterization and practical deployment.

Data availability

The datasets utilized and/or analyzed during the current study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

International Energy Agency (IEA). Net zero roadmap: A global pathway to keep the 1.5°C goal in reach (Updated edition). https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-roadmap-a-global-pathway-to-keep-the-15-0c-goal-in-reach (2023).

Cameron, L. & Carter, A. Why carbon capture and storage is not a net–zero solution for canada’s oil and gas sector. International Institute for Sustainable Development. (2023). https://www.iisd.org/articles/deep-dive/carbon-capture-not-net-zero-solution

Mu, H., Li, S., Wang, X., Zhang, Y. & Chen, L. Numerical simulation of CO₂ geological storage and CH₄ replacement. Pure. Appl. Geophys. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-025-03784-1 (2025). Advance online publication.

Miocic, J. M., Heinemann, N., Edlmann, K., Alcalde, J. & Schultz, R. A. Enabling secure subsurface storage in future energy systems: An introduction. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 528(1), 1–14. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1144/SP528-2023-5?ref=pdf&rel=cite-as&jav=VoR.

Xiao, T. et al. Uncertainty reduction of potential leakage from geologic CO₂ storage reservoirs. Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2025.137734 (2025).

Michael, K. et al. Geological storage of CO₂ in saline aquifers—A review of the experience from existing storage operations. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control. 4 (4), 659–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2009.12.011 (2010).

Ma, J. et al. Carbon capture and storage: history and the road ahead. Engineering 14, 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2021.11.024 (2022).

Bakhshian, S. Dynamics of dissolution trapping in geological carbon storage. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control. 106, 103263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2021.103520 (2021).

Black, J. R., Carroll, S. A. & Haese, R. R. Rates of mineral dissolution under CO₂ storage conditions. Chem. Geol. 399, 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2014.09.020 (2015).

Hesse, M. A., Orr, F. M. Jr. & Tchelepi, H. A. Gravity currents with residual trapping. Energy Procedia. 1 (1), 3275–3281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2009.02.113 (2009).

Kelemen, P. B., Matter, J. M. & Teagle, D. A. H. Carbon dioxide storage in basaltic rocks: geochemical processes and reservoir behavior. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control. 109, 103378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2021.103378 (2021).

Khandoozi, S., Hazlett, R. & Fustic, M. A critical review of CO₂ mineral trapping in sedimentary reservoirs – from theory to application: pertinent parameters, acceleration methods and evaluation workflow. Earth Sci. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2023.104515 (2023). 244, Article 104515.

Krevor, S. et al. Capillary trapping for geologic carbon dioxide storage – From pore scale physics to field scale implications. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control. 40, 221–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2015.04.006 (2015).

Nisbet, H., Buscarnera, G., Carey, J. W., Chen, M. A., Detournay, E., Huang, H., …and Viswanathan, H. S. (2024). Carbon mineralization in fractured mafic and ultramafic rocks: A review. Reviews of Geophysics, 62(2), e2023RG000815. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023RG000815.

Punnam, P. R., Krishnamurthy, B. & Surasani, V. K. Investigation of solubility trapping mechanism during geologic CO₂ sequestration in Deccan volcanic provinces, saurashtra, gujarat, India. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control. 120, 103769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2022.103769 (2022).

Humez, P. et al. CO₂–water–mineral reactions during CO₂ leakage: geochemical and isotopic monitoring of a CO₂ injection field test. Chem. Geol. 368, 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2014.01.001 (2014).

Matter, J. M. et al. Permanent carbon dioxide storage into basalt: the carbfix pilot project, Iceland. Energy Procedia. 1 (1), 3641–3646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2009.02.160 (2009).

Ringrose, P. How to store CO₂ underground: insights from early–mover CCS projects. Springer https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33113-9 (2020).

White, C. M., Smith, D. H., Jones, K. L. & Goodman, A. L. Reconstructing the temperature and origin of CO₂ mineralization in basalt. Chem. Geol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2024.105925 (2020).

Al–Amri, M., Mahmoud, M., Elkatatny, S., Al–Yousef, H. & Al–Ghamdi, T. Integrated petrophysical and reservoir characterization workflow to enhance permeability and water saturation prediction. J. Afr. Earth Sc. 131, 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2017.04.014 (2017).

Elbalawy, M. A., Balash, M., Eid, M. H., Takács, E. & Velledits, F. Innovative method integrates play fairway analysis supported with GIS and seismic modeling for geothermal potential evaluation in a basement reservoir. Sci. Rep. 15, 1325. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79943-6 (2025).

Nabawy, B. S., Abudeif, A. M., Masoud, M. M. & Radwan, A. E. An integrated workflow for petrophysical characterization, microfacies analysis, and diagenetic attributes of the lower jurassic type section in Northeastern Africa margin: implications for subsurface gas prospection. Mar. Pet. Geol. 140, 105678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2022.105678 (2022).

Nasr–El–Din, H. A., Al–Yousef, H. Y. & Ahmed, M. Integrated petrophysical and rock physics characterization of heterogeneous reservoirs. Sci. Rep. 15, 4782. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88639-4 (2025).

Le Poidevin, S. R., Kuske, T. J., Edwards, D. S. & Temple, P. R. Australian petroleum accumulations, Report 7: Browse Basin – Western Australia and Territory of Ashmore and Cartier Islands adjacent area (2nd ed.). Geoscience Australia, Canberra. Geoscience Australia Record 2015/10. (2015).

ConocoPhillips. Poseidon 3D marine surface seismic survey internal report (Unpublished report). Retrieved April 18, 2020, from (2012). https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/0B7brcf-eGK8Cbk9ueHA0QUU4Zjg

AGSO Browse Basin Project Team et al. Browse Basin High Resolution Study, Interpretation Report (Australian Geological Survey Organisation, 1997).

Blevin, J. E., Boreham, C. J., Summons, R. E., Struckmeyer, H. I. M. & Loutit, T. S. An effective Lower Cretaceous petroleum system on the Northwest Shelf: Evidence from the Browse Basin. In P. G. Purcell and R. R. Purcell (Eds.), The sedimentary basins of Western Australia 2: Proceedings of the Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia Symposium (pp. 397–420). Perth: Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia. (1998).

Rollet, N. et al. A Regional Assessment of CO₂ Storage Potential in the Browse Basin (Results of a study undertaken as part of the National CO₂ Infrastructure Plan. Geoscience Australia, 2016).

Van Tuyl, J., Alves, T. M. & Cherns, L. Geometric and depositional responses of carbonate build–ups to miocene sea level and regional tectonics offshore Northwest Australia. Mar. Pet. Geol. 94, 144–165 (2018).

Symonds, P. A., Collins, C. D. N. & Bradshaw, J. Deep structure of the Browse Basin: Implications for basin development and petroleum exploration. In P. G. Purcell and R. R. Purcell (Eds.), The sedimentary basins of Western Australia: Proceedings of the Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia Symposium (pp. 315–331). Perth: Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia. (1994).

Consoli, C. P. et al. Regional assessment of the CO₂ storage potential of the Mesozoic succession in the Petrel Sub–basin, Northern Territory, Australia: Summary report (Record 2014/11). Geoscience Australia, Canberra. (2013). https://doi.org/10.11636/Record.2014.011

Johnstone, R. & Stalker, L. The petrel Sub–basin: A world–class CO₂ store – Mapping and modelling of a scalable and commercially viable CCS development. APPEA J. 62 (1), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1071/AJ21092 (2022).

Nicholas, W. A. et al. Seabed environments, shallow sub–surface geology and connectivity, Petrel Sub–basin, Bonaparte Basin, Timor Sea: Interpretative report from marine survey GA0335/SOL5463 (Record 2015/24). Geoscience Australia, Canberra. (2015). https://doi.org/10.11636/Record.2015.024

Department of Mines and Petroleum. Western Australia’s petroleum and geothermal explorer’s guide: 2014 edition. Western Australian Government – Department of Industry and Resources. Retrieved April 12, 2020, from (2014). https://www.dmp.wa.gov.au/Documents/Petroleum/PD-RES-PUB-100D

Stephenson, A. E. & Cadman, S. J. Browse basin, Northwest australia: the evolution, palaeogeography and petroleum potential of a passive continental margin. Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Paleoecology. 111, 337–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(94)90071-X (1994).

Struckmeyer, H. I. M. et al. Structural evolution of the Browse Basin, Northwest Shelf: New concepts from deep–seismic data. In P. G. Purcell and R. R. Purcell (Eds.), The sedimentary basins of Western Australia 2: Proceedings of the Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia Symposium (pp. 345–367). Perth: Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia. (1998).

Rosleff–Soerensen, B., Reuning, L., Back, S. & Kukla, P. The response of a basin–scale miocene barrier reef system to long–term, strong subsidence on a passive continental margin, Barcoo Sub–basin. Australian Northwest. Shelf Basin Res. 28, 103–123 (2016).

Elliott, R. M. L. Browse basin. In Geology and Mineral Resources of Western Australia: Geological Survey of Western Australia, Memoir 3 (535–547). Perth: Geological Survey of Western Australia. (1998).

Apthorpe, M. Cainozoic depositional history of the Northwest Shelf. In P. G. Purcell and R. R. Purcell (Eds.), The Northwest Shelf, Australia: Proceedings of the Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia Symposium (pp. 55–84). Perth: Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia. (1988).

Reuning, L. et al. June 8–11). Seismic expression of sedimentary processes on a carbonate shelf and slope system, Browse Basin, Australia – Part I: Non-tropical carbonates, Eocene to Lower Miocene. In Proceedings of the 71st EAGE Conference & Exhibition (pp. xx–xx). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: EAGE. (2009).

Harrowfield, M. & Keep, M. Tectonic modification of the Australian North–West shelf: episodic rejuvenation of long–lived basin divisions. Basin Res. 17 (2), 225–239 (2005).

Keep, M., Bishop, A. & Longley, I. Neogene wrench reactivation of the Barcoo Sub–basin, Northwest australia: implications for neogene tectonics of the Northern Australian margin. Pet. Geosci. 6, 211–220 (2000).

Hovland, M. & Judd, A. G. Seabed Pockmarks and seepages – Impact on Geology, Biology and the Marine Environment (Graham and Trotman Ltd, 1988).

O’Brien, G. W. & Woods, E. P. Hydrocarbon–related diagenetic zones (HRDZs) in the Vulcan Sub–basin, Timor sea: recognition and exploration implications. APPEA J. 3, 220–252. https://doi.org/10.1071/AJ94015 (1995).

Ligtenberg, J. H. Unravelling the petroleum system by enhancing fluid migration paths in seismic data using a neural network–based pattern recognition technique. Geofluids 3 (4), 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-8123.2003.00072.x (2003).

Gallagher, S. J., Wallace, M. W., Hoiles, P. W. & Southwood, J. M. Seismic and stratigraphic evidence for reef expansion and onset of aridity on the Northwest shelf of Australia during the pleistocene. Mar. Pet. Geol. 57, 470–481 (2014).

Karas, C., Nürenberg, D., Tiedemann, R. & Garbe–Schönberg, D. Pliocene Indonesian throughflow and Leeuwin current dynamics: implications for Indian ocean Polar heat flux. Paleoceanography 26, PA2217 (2011).

Howarth, V. & Alves, T. M. Fluid flow through carbonate platforms as evidence for deep–seated reservoirs in Northwest Australia. Mar. Geol. 380 (1), 17–43 (2016).

Asquith, G. & Krygowski, D. Basic well log analysis (2nd ed.). AAPG Methods in Exploration Series, No. 16. (2004).

Rider, M. & Kennedy, M. The Geological Interpretation of Well Logs 3rd edn (Rider–French Consulting Ltd., 2011).

Tiab, D. & Donaldson, E. C. Petrophysics: Theory and Practice of Measuring Reservoir Rock and Fluid Transport Properties 4th edn (Gulf Professional Publishing, 2015).

Archie, G. E. The electrical resistivity log as an aid in determining some reservoir characteristics. Trans. AIME. 146 (1), 54–62. https://doi.org/10.2118/942054-G (1942).

Daniel, R. F. & Kaldi, J. G. Evaluating seal capacity of caprocks and intraformational barriers for the geo–sequestration of CO₂. Proceedings of the PESA Eastern Australian Basins Symposium III, Sydney, 14–17 September 2008, 475–484. (2008).

Amadi, U. D., Enyi, G. C. & Mohammed, N. Mathematical models for predicting CO₂ density and viscosity for enhanced gas recovery and carbon sequestration. J. Eng. Res. 29 (4), 85–97. https://doi.org/10.52968/72014018 (2025).

Span, R. & Wagner, W. A new equation of state for carbon dioxide covering the fluid region from the triple–point temperature to 1100 K at pressures up to 800 MPa. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 25 (6), 1509–1596 (1996).

Leila, M., Ramadan, F., Eweda, S. & Eysa, E. A. Linking petrophysical heterogeneity and reservoir rock–typing of the post–rift shallow marine siliciclastics to their depositional setting: the upper cretaceous Bahariya reservoirs, North Western desert, Egypt. J. Afr. Earth Sc. 219, 105401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2024.105401 (2024).

Ma, Y. Z. Multiscale Heterogeneities in Reservoir Geology and Petrophysical Propertiespp. 175–200 (Springer, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-17860-4_8

Manzoor, U. et al. Harnessing advanced Machine–Learning algorithms for optimized data conditioning and petrophysical analysis of heterogeneous, thin reservoirs. Energy Fuels. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.3c01293 (2023).

Luthi, S. M. Geological Well Logs: their Use in Reservoir Modeling (Springer, 2001).

Rider, M. The Geological Interpretation of Well Logs 2nd edn (Whittles Publishing, 2002).

Serra, O. Well Logging and Reservoir Evaluation (Editions Technip, 2007).

Desport, O., Copping, K. & Johnson, B. L. November 15–17). Accurate porosity measurement in gas bearing formations (SPE–147305–MS). Paper presented at the Canadian Unconventional Resources Conference, Calgary, Alberta, Canada. (2011). https://doi.org/10.2118/147305-MS

ElMahdy, O. A. & Hamada, G. M. Integrated NMR and density logs for evaluation of heterogeneous Gas–Bearing Shaly sands. Pet. Sci. Technol. 32 (8), 958–964. https://doi.org/10.1080/10916466.2011.621500 (2014).

Xiao, L., Mao, Z. Q. & Li, G. R. Calculation of porosity from nuclear magnetic resonance and conventional logs in gas–bearing reservoirs. Acta Geophys. 60, 1030–1042. https://doi.org/10.2478/s11600-012-0015-y (2012). [continue list of authors].

Abid, M., Ba, J., Markus, U. I., Tariq, Z. & Ali, S. H. Modified approach to estimate effective porosity using density and neutron logging data in conventional and unconventional reservoirs. J. Appl. Geophys. 233, 105571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jappgeo.2024.105571 (2025).

Abuseda, H. H., El Sayed, A. M. A. A. & Elnaggar, O. M. Permeability modeling of upper cretaceous Bahariya formation rocks, Abu Sennan field, Western desert, Egypt. Arab. J. Geosci. 16, 211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-023-11218-2 (2023).

Hajibolouri, E. et al. Permeability modelling in a highly heterogeneous tight carbonate reservoir using comparative evaluating learning–based and fitting–based approaches. Sci. Rep. 14, 10209. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60995-7 (2024).

Sheykhinasab, A. et al. Prediction of permeability of highly heterogeneous hydrocarbon reservoir from conventional petrophysical logs using optimized data–driven algorithms. J. Petrol. Explor. Prod. Technol. 13, 661–689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-022-01593-z (2023).

Szabó, N. P., Abordán, A. & Dobróka, M. Permeability extraction from multiple well logs using particle swarm optimization based factor analysis. GEM – Int. J. Geomathematics. 13 (10). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13137-022-00200-x (2022).

Qassamipour, M., Khodapanah, E. & Tabatabaei–Nezhad, S. A. Determination of cutoffs by petrophysical log data: A new methodology applicable to oil and gas reservoirs. Energy Sour. Part A Recover. Utilization Environ. Eff., 46(1), 7784–7797. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2020.1759733 (2020).

Andreani, M., Gouze, P., Luquot, L. & Jouanna, P. Changes in seal capacity of fractured claystone caprocks induced by dissolved and gaseous CO₂ seepage. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35 (14), L14404. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GL034467 (2008).

Brosseta, D. Assessing seal rock integrity for CO₂ geological storage purposes. In G. Pijaudier–Cabot & J.–M. Pereira (Eds.), Geomechanics in CO₂ storage facilities (Chap. 1). Wiley. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118577424.ch1

Missenard, Y. et al. Fracture–fluid relationships: implications for the sealing capacity of clay layers – Insights from field study of the blue clay formation, Maltese Islands. Bull. De La. Société Géologique De France. 185 (1), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.2113/gssgfbull.185.1.51 (2014).

Purcell, W. R. Capillary pressures—their measurement using mercury and the calculation of permeability therefrom. Trans. AIME. 186, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.2118/949039-G (1949).

Swanson, B. F. A simple correlation between permeabilities and mercury capillary pressures. J. Petrol. Technol. 33 (12), 2498–2504. https://doi.org/10.2118/8234-PA (1981).

Daniel, R. F. Boggy creek carbon dioxide seal capacity study, Otway basin, victoria, Australia (CO2CRC publication no. RPT05–0045). (2005). Cooperative Research Centre for Greenhouse Gas Technologies (CO2CRC).

Ferer, M., Bromhal, G. S. & Smith, D. H. Pore–level modelling of carbon dioxide sequestration in Brine fields. J. Energy Environ. Res. 2, 120–132 (2002).

Washburn, E. W. A note on the method of determining the distribution of pore sizes in a porous material. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 7(4), 115–116. (1921). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.7.4.115

Ajayi, T., Gomes, J. S. & Bera, A. A review of CO2 storage in geological formations emphasizing modeling, monitoring and capacity Estimation approaches. Pet. Sci. 16, 1028–1063. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-019-0340-8 (2019).

Cao, S. C., Jung, J. W. & Hu, J. W. CO 2–brine displacement in geological CO 2 sequestration: microfluidic flow model study. Appl. Mech. Mater. 752–753, 1210–1213. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.752-753.1210 (2015).

Krevor, S., Pini, R., Zuo, L. & Benson, S. M. Capillary trapping for geologic carbon dioxide storage. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control. 40, 221–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2015.04.006 (2015).

Azin, R., Mehrabi, N., Osfouri, S. & Asgari, M. Experimental study of CO₂–saline aquifer–carbonate rock interaction during CO₂ sequestration. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 15, 413–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeps.2015.08.023 (2015).

Matter, J. M. & Kelemen, P. B. Permanent storage of carbon dioxide in geological reservoirs by mineral carbonation. Nat. Geosci. 2, 837–841. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo683 (2009).

Aradóttir, E. S. P., Sonnenthal, E. L., Björnsson, G. & Jónsson, H. Multidimensional reactive transport modeling of CO₂ mineral sequestration in basalts at the Hellisheidi geothermal field, Iceland. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control. 9, 24–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2012.02.006 (2012).

Amann–Hildenbrand, A., Bertier, P., Busch, A. & Krooss, B. M. Experimental investigation of the sealing capacity of generic clay–rich caprocks. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control. 19, 620–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2013.10.016 (2013).

Amann, A. et al. Sealing rock characteristics under the influence of CO₂. Energy Procedia. 4, 5170–5177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2011.02.488 (2011).

Leila, M. & Mohamed, A. Diagenesis and petrophysical characteristics of the shallow pliocene sandstone reservoirs in the Shinfas gas field, onshore nile delta, Egypt. J. Petroleum Explor. Prod. Technol. 10, 1743–1761. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-020-00873-w (2020).

Hassan, A., Radwan, A., Mahfouz, K. & Leila, M. Sedimentary facies analysis, seismic interpretation, and reservoir rock typing of the syn–rift middle jurassic reservoirs in Meleiha concession North Western desert, Egypt. J. Petroleum Explor. Prod. Technol. 13, 2171–2195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-023-01677-4 (2023).

Krevor, S. C. M., Pini, R., Zuo, L. & Benson, S. M. Relative permeability and trapping of CO₂ and water in sandstone rocks at reservoir conditions. Water Resour. Res. 48, W02532. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011WR010859 (2012).

Snæbjörnsdóttir, S. Ó. et al. CO₂ storage potential of basaltic rocks in Iceland and the oceanic ridges. Energy Procedia. 63, 4585–4600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2014.11.491 (2014).

Leila, M. et al. Concomitant generation of hydrogen during carbon dioxide storage in ultramafic massifs- state of the Art with implications to decarbonization strategies. Carbon Capture Storage Technol. 16, 100481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccst.2025.100481 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mansoura University and the University of Miskolc for their support throughout this work. We’re also grateful to Geoscience Australia for the subsurface data from the Poseidon Field, and to Schlumberger for providing Techlog access through the University of Miskolc.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Miskolc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Y. conceptualized the study, conducted analysis, and wrote the original draft. I.S. supervised the petrophysical analysis and validated the results. M.B. contributed to structural interpretation and supervision. A.A.R., K.K., and M.L. supervised and reviewed the manuscript. N.P.S. provided major input in editing, interpretation, and overall guidance. All authors contributed to discussions and final revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yahia, M., Szabó, I., Badawi, M. et al. Integrated petrophysical and seal characterization of the heterogeneous jurassic plover formation for CO2 storage assessment in Northwest Australia. Sci Rep 15, 35416 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17135-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17135-6