Abstract

A central tenet of human performance posits that past success is a key predictor of future outcomes. This principle underpins selection processes in various human endeavors, shaping opportunity, wage, and winner-take-all inequalities. Here we systematically examine the future performance of previous winners and non-winners across two sports contexts using two different empirical strategies. First, we track young athletes participating in world-class track and field competitions and compare the future performance of bronze medalists to those finishing just shy of the podium. Next, we study a novel natural experiment in tennis, where we compare future performances of ‘lucky losers’—players who advanced to the main draw due to last-minute withdrawals from others—to those who just missed advancing. Our findings reveal that although past performance generally correlates with future outcomes, there appear to be notable exceptions at the margins. Interestingly, individuals initially classified as non-winners, despite being objectively outperformed, can surpass the future performance of their winning counterparts. These results not only reinforce the conventional wisdom of basing talent selection on past success but also introduce important nuances. They highlight the importance of recognizing both winning and non-winning experiences in talent scouting and assessment, with implications for nurturing diverse potential within talent pools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the most robust findings in social and behavioral sciences is that past achievement predicts future achievement1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. Competitive achievement may reflect distinguishing characteristics that render past winners more likely to outperform their non-winning counterparts in future competitions22,23. Further, the Matthew effect suggests that past victories bring reputation and recognition that can translate into tangible assets, again favoring past winners for future victories1,5,6,7. These mechanisms are further supported by widespread evidence from diverse domains ranging from the arts5,11,20 and sciences1,2,4,7,9,12,13,14,15,16 to sports8,15,17,18,19 and business8,10,21. Collectively, the literature underscores one fundamental principle: past winners are generally more likely than nonwinners to achieve future victories.

While these success-breeds-success dynamics may align resources with merit, they generally lead to “winner-take-all” and Yule-like processes that result in sharp inequality in opportunity, wage, and status5,6,7,24. These contrasting outcomes have stimulated a strand of literature that probes the role of setbacks in future achievements25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35beginning to unearth evidence that sometimes appears in tension with the traditional belief about success. For example, recent research compared near-miss and narrow-win junior NIH grant applicants25 whose proposals fell just below and just above an arbitrary funding cutoff, showing that PIs who were near-misses had stronger research records than narrow-winners in the longer run. This result is consistent with the behavioral literature, which suggests that failure may teach valuable lessons that are otherwise difficult to learn29,30,31,32,33 as well as motivate individuals to increase their effort in their future endeavors25,26,27,28,34,35,−36.

While the NIH study offers compelling evidence of performance reversals in the long run, it leaves open several important questions. First, the domain of science is subject to its own dynamics37, norms38,39,40,41, and biases42,43,44,45,46,47, raising the question of whether the findings apply to other domains. Second, in many real-world settings, past and future performance is measured objectively. By contrast, the NIH context features many known peculiarities around grant-making7,25,48,49,50, peer reviews51,52,53,54, and citation dynamics in science9,25,37,42. Third, and perhaps most importantly, prior studies25 define the winner and nonwinner groups based on exogenous factors, meaning the two groups are similar a priori in both observable and unobservable ways. Yet, in many real-world competitive environments, winners possess meaningful endogenous performance advantages from the outset. It thus remains unclear whether motivational or developmental benefits from narrowly missing victory can overcome the inherent advantages enjoyed by past winners. Overall, these open questions hold important implications for how best to identify and nurture talents, amidst longstanding debates about whether great success is indicative of great potential1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,,22,55.

This debate has also extended into studies exploring short-term motivational effects in performance-driven contexts such as sports. For example, Berger and Pope27 found that basketball teams trailing slightly at halftime were more likely to win, attributing this to an immediate motivational surge. However, subsequent analysis by Teeselink et al.59, using a larger dataset across multiple sports, found limited support for such short-term reversals, highlighting important distinctions between transient psychological momentum and longer-term developmental resilience60. Thus, existing evidence from competitive sports offers mixed insights focused largely on short-term horizons, underscoring the need to clearly differentiate immediate motivational boosts from sustained long-term improvements.

To address these open questions, our research investigates the long-term consequences of narrowly missing success within the domain of professional individual sports. Sports provide an ideal empirical environment, as athlete performance is objectively, transparently, and consistently measured across events. By examining contexts in which winners were objectively better than non-winners, we explicitly introduce endogenous performance differences at baseline. Our central research question thus becomes: Given clear initial differences in objective ability, who performs better over the long run—narrow winners or those who narrowly miss victory? This approach allows us to evaluate whether the advantages conferred by early success outweigh the motivational and developmental benefits of narrowly missing victory. In doing so, our study generalizes and extends prior work, probing how initial success and setback shape long-term achievement, thus offering broader insight into the mechanisms driving cumulative advantage, resilience, and talent development across diverse competitive contexts.

Empirical strategies and results

Our first study harnesses the fact that rewards in real-world competitions often have predefined cutoffs. For example, in many sports, only the first three finishers are awarded a medal (i.e., the podium cutoff), creating a categorical difference between bronze medalists and fourth-place finishers. Given that bronze medalists objectively outperformed their fourth-place counterparts, an intriguing question arises: who performs better in the future? To answer this question, we collected data from the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF, now World Athletics) which capture all major track and field competitions (Table S1). We focus on athletes under the age of 21 who first appeared in competition finals between 1987 and 2009 (n = 5,101). We first categorize them based on their rank in the first final appearance and then trace their future performance in terms of the number of medals won over the next four years (Fig. 1a). We find that athletes who started as gold medalists won 3.18 medals on average. By contrast, the silver medalists won 1.85 medals on average, and the bronze medalists won fewer medals still (1.35). These results suggest that future achievements follow an overall decreasing trend as a function of the initial rank. Indeed, a similar trend continues for the fifth- and sixth-place finishers, who averaged 0.91 and 0.87 medals, respectively. Overall, these results support the principle of selecting past winners, indicating that the initial placement alone offers substantial predictive power for future achievements. Yet, when we conduct the same analysis for the fourth-place finishers, we find that their future performance appears to deviate from the overall trend. Indeed, the fourth-place finishers received on average 1.72 medals, which appear to violate the overall relationship between the past and future achievements observed for other ranks.

Comparison of future performance of bronze medalists vs. fourth-place finishers in track and field competitions. Panels (a–c) show the average number of medals earned by athletes over three post-competition periods: (a) 1–4 years, (b) 1–2 years, and (c) 3–4 years. Sample sizes for each group in the 1–4 year period are n = 213, 226, 246, 241, 234, 231 for gold, silver, bronze, No. 4s, No. 5s, No. 6s, respectively. Red line indicates curve fitting to data excluding No. 4s using the ansatz \(\:y=\:\frac{a}{x}+b\) as a guide to the eye. The results show anomalous performance improvement exhibited by the fourth-place finishers. (d–f) To test if the observed performance difference can be explained by the differential attrition rate across the groups, we perform a conservative estimation by removing the athletes who have the worst ranks ex post from the group of gold, silver, and bronze medalists, such that after removal these groups have the same attrition rate as the fourth-place finishers. Even after this adjustment, the performance advantage of fourth-place finishers remains evident. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

To understand if the observed patterns hold not just for winning medals but for other levels of future performance, we measure the cumulative distribution of ranks achieved by athletes in each group in the four-year period (Fig. 2a). Consistent with results shown in Fig. 1a, we find that initial gold medalists achieved overall better ranks than initial silver medalists (Mann-Whitney U Test, p-value = 1.9 × 10− 7), who in turn were better than the bronze medalists (Mann-Whitney U Test, p-value = 0.0005). Similarly, the fourth-place finishers performed better than their fifth-place counterparts. However, comparing bronze medalists with the fourth-place finishers, we find the latter outperformed the former (Mann-Whitney U Test, p-value = 0.04), again violating the canonical relationship between past and future performance. These findings generalize the performance reversal across rank distributions, not just medal counts.

Performance trajectories, record-breaking, and pairwise comparisons reveal performance improvements for fourth-place finishers. (a) Distribution of ranks achieved over the next four years in track and field competitions. (b) Probability of breaking records (world, Olympic, or championship) as a function of the initial rank. Note that most of the records broken are championship records (81%). (c) For athletes with record-breaking performance in our sample, the probability that they started their career at a certain rank. We employ a one-sided proportion test, finding that the initial ranks of significant proportions are gold medalists and fourth-place finishers (p-value = 0.0002 and 0.02, respectively). (d) Illustration for the pairwise comparison. We pick the young athlete who began his career at rank i and pair him with the athlete who was ranked immediately before him (rank i − 1), who may or may not be a young athlete. For example, we pair a silver medalist with the corresponding gold medalist at that competition. We then calculate the winning probability between the two when they compete again directly in the same competition. More specifically, if both athletes in a pair appeared in the final, we compare their ranks directly. If one of them advanced to the final but the other did not, the one who was in the final wins. If neither of them made it to the final, we compare their best performances across various stages of the event (qualification, heats, quarterfinals, semifinal, etc.). (e-i) The above-mentioned winning probabilities between adjacently ranked pairs: (e) gold vs. silver medalists; (f) silver vs. bronze medalists; (g) bronze medalists vs. no. 4s; (h) no. 4s vs. no. 5s; and (i) no. 5s vs. no. 6s. (j) Upset probability measured as the probability that the initially lower-ranked athletes outperformed the higher-ranked athletes during the pair-wise comparisons. Among all pairs, only the fourth vs. bronze match exhibits an upset probability significantly above chance. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

We test the robustness of these results across several dimensions. First, recognizing the cyclic nature of competitions such as the Olympics, we separate the four-year window into the first (Fig. 1b and Fig. S1a) and second two-year period (Fig. 1c and Fig. S1b) and repeat our analyses in each, uncovering the same patterns. We further aggregate performance records over the next eight years and the rest of their careers, and we arrive at similar conclusions (Fig. S2). Also, we repeat our analyses using other performance measures, calculating the number of gold, silver, and bronze medals received, respectively (Fig. S3a-c), the average number of appearances in the finals (Fig. S3d) and the probability of winning a medal (Fig. S3e). To further test the generality of our findings across disciplines, we stratify the track and field events into two broad categories: running events and field events (jumps and throws) and repeat our analyses within each category (Fig. S6ab). Across all these variations, we obtain broadly consistent patterns. To understand if the observed difference is driven by outliers, we divide our samples into four quartiles by the athlete’s median rank in the following four years and examine their future performance separately (Fig. S4). We find that the fourth-place finishers outperform their bronze-medal counterparts in all but the bottom quartile. We further examine the temporal stability of our results, grouping our samples by cohorts, and again find consistent conclusions (Fig. S5). The reversal persists across multiple timeframes, metrics, and cohorts, suggesting that it is a systematic phenomenon rather than a statistical artifact.

To test if the observed performance outcomes extend beyond winning medals, we measure the occurrence of record-breaking performances (including world records, Olympic records, and championship records). We take the same groups of athletes analyzed so far and calculate instead their probability of breaking records in the four-year period. We find that the initial gold medalists have the highest probability of breaking records (9.86%), demonstrating that the athletes ranked number one disproportionately dominate the sports in which they engage (Fig. 2b). The group with the second highest probability of record-breaking performance averaged 5.81%. Interestingly, however, this group is neither the silver nor the bronze medalists, but those who initially finished fourth. We also find that the largest share of record breakers in this sample, 29.2%, began their careers as gold medalists, and the second-highest share, 19.4%, is again athletes who started their careers in fourth place (Fig. 2c). We repeat our analyses by tracing the performance of these athletes for their entire careers, arriving at consistent conclusions (Fig. S1c, d).

One possible explanation for these observations is that athletes may choose to participate in competitions with variable intensity, which may influence their rank and performance. To control for this, we pick pairs of athletes with adjacent ranks (gold vs. silver, silver vs. bronze, bronze vs. fourth place, etc.), and we compare their performance when they directly compete again. More specifically, we pick one athlete studied in our sample and pair them with the athlete who finished just before them in the same final (Fig. 2d). We then trace all future competitions in which the two compete directly against each other and count the number of times one outperforms the other. We find that, in terms of future winning probability, silver medalists perform significantly worse than their gold-medal counterparts (Fig. 2e, Binomial test, p-value = 0.0005). This again supports the notion that past winners are more likely to win again. We observe similar patterns when comparing bronze medalists with their silver-medal counterparts (Fig. 2f, Binomial test, p-value = 0.007), fifth-place finishers with fourth-place finishers (Fig. 2h, Binomial test, p-value = 0.009), or sixth-place finishers with fifth-place finishers (Fig. 2i, Binomial test, p-value = 0.10). However, this relationship reverses when we compare the fourth-place finishers with their bronze-medal counterparts; the fourth-place finisher won 59.2% of the time when the two competed again directly (Fig. 2g, Binomial test, p-value = 0.0001).

To visualize these results across different pairs of comparison, we calculate the “upset probability,” measuring the likelihood that the initially lower-ranked athlete outperforms their higher-ranked counterparts in future direct competitions. Figure 2j shows that the fourth-place finisher vs. bronze medalist is the only pair with an upset probability that is greater than zero. These direct matchups strengthen the inference of a true performance reversal, beyond aggregate trends. These findings further contest the hypothesis of regression toward the mean, as the reversal only occurs for the pair around the podium cutoff but not for other pairs of athletes. We compute several different measures to test the robustness of these results, including rank differences, differences in performance improvement, and the average number of medals, finding consistent conclusions (Fig. S7). Furthermore, we test the robustness of these results under alternative pair selection method, consistently observing the same patterns (Fig. S8).

Another possible explanation for the performance reversal is the differential survival rates across groups. Indeed, the screening mechanism56 suggests that, if past failure screens out less-determined individuals, non-winners who persevere could, by selection, end up outperforming their winning counterparts. Here we find that the survival rate indeed decays as a function of initial rank (Fig. S16a), which raises the question of whether the screening effect alone can account for the observed performance dynamics. To answer this question, we remove athletes from the gold, silver and bronze medal groups such that the attrition rate following removal is the same as the fourth-place finishers. We perform a conservative removal procedure by removing athletes who, ex post, perform worst within each group in terms of average ranks in future competitions. We find that while this procedure provides artificial upward adjustments to the performances of the medalists (Fig. S17a-c), it appears insufficient to account for the anomalous performance improvement exhibited by the fourth-place finishers (Fig. 1d-f). We further follow a similar procedure to adjust the attrition rate across the groups for our pair-wise comparison measurements in Fig. 2g, finding the conclusions remain the same (Fig. S18).

Overall, these results suggest that across different measures of performance, young athletes who begin their careers in fourth place tend to outperform their third-place counterparts in the future. We further find that these results are not explained by self-selection in easy competitions, attrition rates across groups, or regression toward the mean. Given that the bronze medalists initially outperform the fourth-place finishers, with the two groups separated along a pre-defined cutoff, these results extend beyond prior studies25showing a statistically significant performance reversal between past winners and non-winners, despite their prior performance differences.

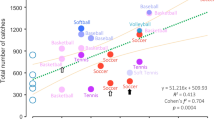

To test the generalizability of these findings and to further improve causal interpretations, we next study the same question in a different context using a quasi-experimental approach, where individuals are artificially shifted into the positions of just above and just below a cutoff. Specifically, we study ATP Tour tennis matches (2007–2018, n = 2688) (SI 1.2). This dataset is unique in that it records the qualifying rounds for the main draw of the tournaments. Indeed, while the top ranked players enter the main draw automatically, a large number of players must compete in knockout qualifying rounds before the main event, and only the winners in the last qualifying round enter the main draw. However, between the qualifying rounds and the main competition, players who have qualified may withdraw unexpectedly due to illness, injury, or other reasons. In such cases, players who were initially disqualified (lost in the last qualifying round) are unexpectedly admitted to the main draw based on their prior ranking (SI S1.2). Since such players advanced to the main tournament due to vacancies created exogenously by others (i.e., the treatment condition), they are commonly referred to as “lucky losers”57,58. At the same time, each “lucky loser” also left behind an “unlucky loser,” who ranked immediately below the lucky loser and was artificially shifted to the position just below the entry cutoff (see Fig. 3a, b for an illustration). By analogy to our first study, the lucky loser in tennis is similar to the bronze medalist in track and field competitions and the unlucky loser is analogous to the fourth-place contestant. Given that lucky losers were better than unlucky losers based on their prior ATP rankings, we are prompted to ask: who performs better in future tournaments?

Illustration for the treatment and control condition for lucky losers vs. unlucky losers in tennis. (a) The treatment condition: when someone from the main draw withdraws due to injury, illness, or other reasons, it artificially shifts lucky losers (LL) and unlucky losers (UL) into the positions of just above or below the entry cutoff. (b) The control condition: in the absence of player withdrawal, we identify the hypothetical lucky loser (LL(C)) and hypothetical unlucky loser (UL(C)). n = 223, 172, 185, 196 for the lucky losers, unlucky losers, hypothetical lucky losers, hypothetical unlucky losers, respectively.

To better understand the performance baseline between lucky losers and unlucky losers, we first examine the control condition, in which no player withdrawal took place. In such cases, while the disqualified players were not ranked explicitly, we can nevertheless calculate their rankings to identify the hypothetical lucky loser and hypothetical unlucky loser—the would-have-beens, should the treatment have occurred. We compare the future performances of the two groups by measuring the match-winning probability in future tournaments (Fig. 4a). We find that in the control condition, the hypothetical lucky losers tend to outperform their hypothetical unlucky loser counterparts (p-value = 0.0049), which again supports the conventional wisdom that past performance predicts future performance. However, when repeating the same analysis for the treatment condition, we find that the unlucky losers had a significantly higher future winning probability than the lucky losers (p-value = 8.67 × 10− 8) (Fig. 4a), suggesting a performance reversal between the two groups. Indeed, we calculate the match-winning probability for their prior contests (i.e., before the treatment occurred) and find that, as expected, lucky losers used to perform systematically better than unlucky losers prior to treatment (Fig. 4b). We further examine a range of additional performance metrics and reach similar conclusions (Fig. S14). These findings provide evidence that narrowly missing an opportunity can, under certain conditions, lead to superior future performance—even among those with initially lower baseline rankings.

Comparing long-term performance of Lucky losers vs. unlucky losers in tennis. (a) Match winning probability in future contests for lucky losers (LL), unlucky losers (UL), hypothetical lucky losers (LL(C)), and hypothetical unlucky losers (UL(C)). (b) Match winning probability but for prior contests. (c) Probability of reaching quarterfinal or higher in a future tournament. (d, e) We further compare LL(C)s, UL(C)s, LLs, and ULs with their respective winners in the last qualifying round and look at the performance in future matches based on (d) match winning probability and (e) probability of reaching quarterfinal or higher in a tournament. Results show that unlucky losers consistently outperform the lucky losers in future tournaments. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

To check the robustness of these results, we vary our performance measures by calculating the probability of reaching quarterfinals or beyond (Fig. 4c). We also measure separately the probability of advancing to semi-finals, finals, or winning the tournaments (Fig. S10). We run further tests to ensure our results are not affected by cases of having multiple lucky losers in one tournament (Fig. S12 and Fig. S13). Across all these measures, we find that under the treatment condition, unlucky losers consistently outperform the lucky losers in future tournaments. To further examine these effects over time, we analyze performance trends pre- and post-treatment, again arriving at consistent results (Fig S15).

To understand if the observed performance dynamics are related to the lucky losers getting worse, we compare the lucky and unlucky losers with the players that beat them in the last qualifying round of the tournament. We find that those who beat the lucky losers significantly outperform them in future tournaments (Fig. 4d, e). Comparing the unlucky losers with those who beat them in the last qualifying rounds, however, we find a lack of difference between the two in terms of future performance, with suggestive evidence for a reversal of performance. This suggests that an unlucky loser’s future performance appears at least on par with that of the player who previously beat them (Fig. 2f, g & Fig. S11). We further perform the conservative removal procedure to adjust for differential attrition rates between the lucky loser and unlucky loser groups (Fig. S16b), removing players with the lowest ATP rankings ex-post, finding that the conclusions remain the same (Fig. S17d). To rule out any characteristic difference, we consider age, height and weight of the players belonging to different groups, finding no significant difference among the hypothetical lucky loser and unlucky loser. Additionally, to rule out baseline differences in player characteristics, we compare age, height, and weight across groups and find no significant differences (Fig. S9). Taken together, these robustness checks are consistent with the hypothesis that narrowly missing success can generate gains that manifest in higher long-term performance.

Discussion

Taken together, this paper examines two different domains of sports and shows that while past performance is overall predictive of future performance, there are important nuances to the overall picture. In particular, we find that when measuring the performance of past winners and nonwinners in objective and uniform ways within each sport, nonwinners can exhibit atypical performance dynamics that propel them to greater success, despite the prior performance differentials between the winners and nonwinners. Overall, these results contribute to a nascent strand of literature probing the link between setbacks and achievements25,31 with implications for the nurturing and broadening of potential talent pools.

These results also raise key questions for future investigations. First, what are the boundary conditions under which the observed performance dynamics might occur? The empirical evidence presented in this paper not only extends the prior literature into new domains but also shows that performance reversal can occur even when past winners were objectively better than the non-winners. However, given the endogenous differences between past winners and nonwinners, and the Matthew effect that tends to favor past winners, the occurrence of performance reversal requires that the performance boost associated with not winning is great enough to offset the gross advantages conferred by winning25. It thus suggests that the reversal may only be detectable in certain populations and domains (SI S3). For example, the existence of prior performance differentials may explain why the performance reversal was not detected between the gold and the silver32given the convex relationship between rank and performance shown in Fig. 1a, d, suggesting a larger performance gap between the gold and silver than between the third and fourth place. We also find that in the track and field data, the performance reversals mainly hold for early-career athletes (Fig. S19 and S20), which is consistent with the literature on performance and motivation25,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35as early setbacks may be more potent and may identify problems early while allowing for more space to grow.

Beyond early-career stage and narrow rank gaps, additional contextual factors may moderate the occurrence and magnitude of performance reversals. One such factor is the distinction between individual and team sports. In individual sports, outcomes are more directly attributable to a single athlete’s actions, and feedback from competition is immediate and personally salient. This may intensify the psychological impact of narrowly missing a win, increasing the likelihood of motivational rebound and performance improvement. In contrast, team sports involve shared agency and outcome attribution, where individual underperformance may be masked—or reinforced—by collective dynamics. These factors could dilute the personal salience of a near miss, potentially weakening its consequences. While our current data are primarily from individual sports, future work may investigate how team-based structures and interpersonal dependencies shape the effectiveness of setbacks as a developmental experience.

While our analysis controls for several key observable factors—such as prior performance, event type, and competition level—we acknowledge important limitations related to unobserved heterogeneity. Factors such as access to elite coaching, training intensity, recovery resources, and psychological support can meaningfully influence athlete trajectories but remain outside the scope of our dataset. These unobservable confounders may contribute to performance variation and limit causal interpretations. As such, our findings should be viewed as identifying robust patterns rather than isolating causal effects.

Further, the data-driven nature of our studies leaves open the important questions of mechanisms underlying the performance dynamics between past winners and non-winners. Conceptually, the observed patterns may flow from a range of individual, social, or institutional factors, and may operate according to multi-dimensional or domain-specific mechanisms. A promising explanatory framework is provided by the theory of grit28which highlights the role of sustained passion and perseverance in achieving long-term goals. Our findings are consistent with the idea that near-miss experiences intensify motivation and goal commitment in gritty individuals, leading to long-run performance improvements. These outcomes may also be understood in light of Sitkin’s framework29 on learning through failure, which argues that small, non-fatal setbacks—such as narrowly missing a win—can serve as strategic learning opportunities. Near-miss experiences may deliver valuable performance feedback while preserving motivation, particularly when situated within psychologically safe environments30 that support risk-taking and resilience. In parallel, goal-setting theory61 suggests that specific, challenging but attainable goals boost motivation and performance by focusing attention and enhancing persistence. A near-miss may act as a psychologically salient reference point that implicitly sets a new, reachable goal—thereby catalyzing renewed effort and sharpening performance focus.

Our findings may also be explained through the lens of growth mindset theory62which suggests that individuals who view abilities as malleable are more likely to see setbacks as opportunities for learning and development. A near-miss may reinforce a belief in the value of effort and improvement, particularly for individuals with a growth-oriented mindset. Relatedly, the psychological resilience literature suggests that the ability to recover from adversity is a key determinant of long-term success. Resilient individuals may leverage near-miss experiences to build adaptive coping strategies and future-facing motivation, amplifying the performance rebound effect we observe. This interpretation is supported by an extensive body of research demonstrating that resilience can be developed through ordinary adaptive processes63is shaped by social and contextual factors64and plays a significant role in high-performance settings, including sports65,66.

This perspective aligns closely with recent longitudinal studies that track athletic performance development. For instance, studies on young sprinters67 demonstrate that athletic progression is highly individual and non-linear, establishing that developmental trajectories are not fixed hence might be altered by significant events such as a salient near-miss experience. Similarly, research on elite swimmers68 shows that athletes can remain on a viable path to success by staying within a broad “performance corridor” rather than needing to win consistently; a near-miss can thus act as powerful confirmation that an athlete is competitive, fueling the motivation needed to ascend within that corridor. Moreover, the dynamic of overcoming a persistent disadvantage, as seen in studies where younger athletes eventually surpass their relatively older peers69 further reinforces that the psychological and behavioral adaptations required to overcome a setback might drive superior future achievement.

These theoretical lenses suggest several testable hypotheses for future research: for instance, that individuals high in grit or those operating in psychologically safe or growth-oriented environments may be more likely to translate near-miss experiences into future success. Alternatively, the extent to which individuals interpret small failures as developmental feedback—as opposed to ego threat—may mediate post-setback performance. While our current data do not permit testing of these mechanisms, future work may illuminate how these drivers shape long-term achievement trajectories.

By showing that similar patterns may occur across different settings, our paper suggests that these psychological drivers, including effort and grit factors following failures28,29,30,31 and other domain-agnostic mechanisms may be particularly worthy of investigation. Isolating these drivers, however, requires additional experimentation and goes beyond the scope of this work. As such, the performance dynamics observed in this paper should be treated in a phenomenological sense, highlighting the importance of past nonwinning experiences in predicting future achievements without implying any associated drivers for the phenomena. Crucially though, the findings presented in this paper hold the same, regardless of the underlying drivers.

More broadly, the implications of our findings extend beyond sports and into domains such as education, workforce development, and organizational talent management. Rather than treating early failures as signals of low potential, educators and institutions might recognize them as inflection points that, if met with appropriate encouragement and resources, could catalyze personal growth, persistence, and future success. Similarly, in workforce development and talent management, early-career employees who are passed over for promotions, awards, or selective opportunities may, under certain conditions, outperform their peers in the long run. This suggests a need to reexamine traditional evaluation frameworks that prioritize early winners, potentially overlooking individuals whose resilience and adaptive capacity emerge more clearly after initial setbacks. Organizations might benefit from identifying and supporting these “near-miss” individuals through coaching, feedback, or development programs while further leveraging the motivational energy generated by narrowly missing success.

Ultimately, our findings encourage a shift in how performance potential is assessed and nurtured across competitive environments. They underscore the importance of viewing early-stage failure not solely as a risk factor but also as a possible predictor of exceptional long-term performance, particularly when accompanied by mechanisms that foster resilience and sustained effort. This perspective opens the door to more equitable and forward-looking approaches to talent development across broad domains.

Materials and methods

Data collection and filtering

We collected the track and field dataset from the IAAF (International Association of Athletics Federations, now World Athletics), which is the international governing body for athletics covering track and field events. The official website of the IAAF (formerly, https://www.iaaf.org/competition, now https://www.worldathletics.org/) contains the data of all major track and field events. The dataset consists of 40,816 athletes and 43 Track and Field disciplines (see SI 1.1). We exclude certain categories based on the following criteria: (i) sports held only sporadically; (ii) events with a high number of participants in the finals, such as long-distance events (marathon, half-marathon, and racewalks) and combined events (heptathlon, pentathlon, decathlon); (iii) sports conducted exclusively indoors. The detailed description of the dataset is presented in Table S2 (SI 1.1).

We collected the tennis dataset from https://www.atptour.com/. The dataset consists of 194,840 matches played in various ATP Tour tournaments and Grand Slam events over four different surfaces (hard, clay, grass, and carpet) spanning the period of 1915–2019 (Table S3). To examine “lucky losers,” we focus on tournaments after 2007, since data for earlier tournaments do not contain information regarding the qualifying rounds. In total, our dataset captures 2,688 tennis players participating in 825 tournaments (hard − 452, clay − 286, grass − 83, carpet − 4) and playing 54,084 matches during the period of 2007–2019 (see SI 1.2 for more details).

Upset probability

Upset probability is measured as the likelihood that the initially lower-ranked athlete outperforms the higher-ranked athlete in direct future competitions.

where \(\:{\:p}_{l\:>\:h}\)refers to the probability that lower-ranked athletes (l) are better than higher-ranked athletes (h). Similarly, \(\:{\:p}_{h\:>\:l}\) refers to the probability that higher-ranked athletes (h) are better than lower-ranked athletes (l).

Data availability

We have used data corresponding to public sports events. Our code and data are available at https://osf.io/pe7cg/.

References

Merton, R. K. Matthew effect in science. Science 159, 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.159.3810.56 (1968).

Price, D. d. S. A general theory of bibliometric and other cumulative advantage processes. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 27, 292–306 (1976).

Barabási, A. L. & Albert, R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science 286, 509–512 (1999).

Allison, P. D., Long, J. S. & Krauze, T. K. Cumulative advantage and inequality in science. Am. Sociol. Rev. 47, 615–625. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095162 (1982).

Salganik, M. J., Dodds, P. S. & Watts, D. J. Experimental study of inequality and unpredictability in an artificial cultural market. Science 311, 854–856 (2006).

Van de Rijt, A., Kang, S. M., Restivo, M. & Patil, A. Field experiments of success-breeds-success dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 6934–6939 (2014).

Bol, T., de Vaan, M. & van de Rijt, A. The Matthew effect in science funding. P Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 115, 4887–4890. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1719557115 (2018).

Gladwell, M. Outliers: The story of successHachette UK,. (2008).

Wang, D. & Barabási, A. L. The Science of Science (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Barabási, A. L. The formula: The universal laws of auccess. (Little, Brown, and Company, (2018).

Fraiberger, S. P., Sinatra, R., Resch, M., Riedl, C. & Barabasi, A. L. Quantifying reputation and success in Art. Science 362, 825–. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau7224 (2018).

Petersen, A. M. et al. Reputation and impact in academic careers. P Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111, 15316–15321. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1323111111 (2014).

Newman, M. E. J. The first-mover advantage in scientific publication. Epl-Europhys Lett. 86 https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/86/68001 (2009).

Azoulay, P., Stuart, T., Wang, Y. B. & Matthew Effect or fable? Manage. Sci. 60, 92–109. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2013.1755 (2014).

Petersen, A. M., Jung, W. S., Yang, J. S. & Stanley, H. E. Quantitative and empirical demonstration of the Matthew effect in a study of career longevity. P Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108, 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1016733108 (2011).

Agarwal, R. & Gaule, P. Invisible geniuses: could the knowledge frontier advance faster? Am. Economic Review: Insights. 2, 409–424 (2020).

Radicchi, F. Universality, limits and predictability of gold-medal performances at the olympic games. Plos One. 7, e40335 (2012).

Epstein, D. J. The Sports Gene: Inside the Science of Extraordinary Athletic Performance (Penguin, 2014).

Syed, M. & Clamp, J. BounceHarperCollins New York, NY,. (2010).

Galenson, D. W. Old Masters and Young Geniuses (Princeton University Press, 2011).

Porter, M. E. Competitive Advantage of Nations: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance (Simon and Schuster, 2011).

Rosen, S. The economics of superstars. Am. Econ. Rev. 71, 845–858 (1981).

Frank, R. H. & Cook, P. J. The winner-take-all Society (Free, 1995).

Merton, R. K. Matthew effect in science. Science 159, 56–. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.159.3810.56 (1968).

Wang, Y., Jones, B. F. & Wang, D. Early-career setback and future career impact. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–10 (2019).

Yin, Y., Wang, Y., Evans, J. A. & Wang, D. Quantifying the dynamics of failure across science, startups and security. Nature 575, 190–194 (2019).

Berger, J. & Pope, D. Can losing lead to winning? Manage. Sci. 57, 817–827. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1110.1328 (2011).

Duckworth, A. Grit: The power of passion and perseveranceScribner,. (2016).

Sitkin, S. B. Learning through failure: the strategy of small losses. Res. Organizational Behav. 14, 231–266 (1992).

Edmondson, A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 44, 350. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999 (1999).

Taleb, N. N. Antifragile: Things that Gain from DisorderVol. 3 (Random House Incorporated, 2012).

Medvec, V. H., Madey, S. F. & Gilovich, T. When less is more: counterfactual thinking and satisfaction among olympic medalists. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 69, 603 (1995).

Roese, N. J. & Epstude, K. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology Vol561–79 (Elsevier, 2017).

Atkinson, J. W. An introduction to motivation. (1964).

Carver, C. S. & Scheier, M. F. On the self-regulation of Behavior (Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Burnette, J. L., O’Boyle, E. H., VanEpps, E. M., Pollack, J. M. & Finkel, E. J. Mind-sets matter: A meta-analytic review of implicit theories and self-regulation. Psychol. Bull. 139, 655 (2013).

Wang, D., Song, C. & Barabási, A. L. Quantifying long-term scientific impact. Science 342, 127–132 (2013).

Merton, R. K. The normative structure of science. The Sociol. Science: Theoretical Empir. Investigations, 267–278 (1979).

Mulkay, M. J. Norms and ideology in science. Social Sci. Inform. 15, 637–656 (1976).

Macfarlane, B. & Cheng, M. Communism, universalism and disinterestedness: Re-examining contemporary support among academics for merton’s scientific norms. J. Acad. Ethics. 6, 67–78 (2008).

Kim, S. Y. & Kim, Y. The ethos of science and its correlates: an empirical analysis of scientists’ endorsement of mertonian norms. Sci. Technol. Soc. 23, 1–24 (2018).

Fortunato, S. et al. Sci. Sci. Science 359, eaao0185 (2018).

Nissen, S. B., Magidson, T., Gross, K. & Bergstrom, C. T. Publication bias and the canonization of false facts. Elife 5, e21451 (2016).

Moss-Racusin, C. A., Dovidio, J. F., Brescoll, V. L., Graham, M. J. & Handelsman, J. Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 16474–16479 (2012).

Wessely, S. Peer review of grant applications: what do we know? Lancet 352, 301–305 (1998).

Huang, J., Gates, A. J., Sinatra, R. & Barabási, A. L. Historical comparison of gender inequality in scientific careers across countries and disciplines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 4609–4616 (2020).

Clauset, A., Arbesman, S. & Larremore, D. B. Systematic inequality and hierarchy in faculty hiring networks. Sci. Adv. 1, e1400005 (2015).

Azoulay, P. & Li, D. Scientific grant funding. Vol. 26889 (2020).

Jacob, B. A. & Lefgren, L. The impact of research grant funding on scientific productivity. J. Public. Econ. 95, 1168–1177 (2011).

Azoulay, P., Graff Zivin, J. S. & Manso, G. Incentives and creativity: evidence from the academic life sciences. RAND J. Econ. 42, 527–554 (2011).

Pier, E. L. et al. Low agreement among reviewers evaluating the same NIH grant applications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, 2952–2957 (2018).

Kotchen, T. A., Lindquist, T., Malik, K. & Ehrenfeld, E. NIH peer review of grant applications for clinical research. Jama 291, 836–843 (2004).

Kotchen, T. A. et al. Outcomes of National institutes of health peer review of clinical grant applications. J. Investig. Med. 54, 13–19 (2006).

Li, D. & Agha, L. Big names or big ideas: do peer-review panels select the best science proposals? Science 348, 434–438 (2015).

van de Rijt, A. Self-correcting dynamics in social influence processes. Am. J. Sociol. 124, 1468–1495 (2019).

Elton, E. J., Gruber, M. J. & Blake, C. R. Survivor bias and mutual fund performance. Rev. Financial Stud. 9, 1097–1120. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/9.4.1097 (1996).

Gilsdorf, K. F. & Sukhatme, V. A. Testing rosen’s sequential elimination tournament model: incentives and player performance in professional tennis. J. Sports Econ. 9, 287–303 (2008).

Okholm Kryger, K. et al. Medical reasons behind player departures from male and female professional tennis competitions. Am. J. Sports Med. 43, 34–40 (2015).

Klein Teeselink, B., van den Assem, M. J. & van Dolder, D. Does losing lead to winning? An empirical analysis for four sports. Manage. Sci. 69, 513–532 (2023).

Morgulev, E. Streakiness is not a theory: on momentums (hot hands) and their underlying mechanisms. J. Econ. Psychol. 96, 102 (2023).

Locke, E. A. & Latham, G. P. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. Am. Psychol. 57, 705 (2002).

Dweck, C. S. Mindset: the New Psychology of Success (Random House, 2006).

Masten, A. S. Ordinary magic: resilience processes in development. Am. Psychol. 56, 227 (2001).

Southwick, S. M., Bonanno, G. A., Masten, A. S., Panter-Brick, C. & Yehuda, R. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology. 5, 25338 (2014).

Fletcher, D. & Sarkar, M. Psychological resilience. Eur. Psychol. 18, 12–23 (2013).

Sarkar, M. & Fletcher, D. Psychological resilience in sport performers: a review of stressors and protective factors. J. Sports Sci. 32, 1419–1434 (2014).

Romann, M. et al. Longitudinal performance trajectories of young female sprint runners: A new tool to predict performance progression. Front. Sports Act. Living. 6, 1491064 (2024).

Born, D. P., Stöggl, T., Lorentzen, J., Romann, M. & Björklund, G. Predicting future stars: probability and performance corridors for elite swimmers. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 27, 113–118 (2024).

Rüeger, E., Javet, M., Born, D. P., Heyer, L. & Romann, M. Why age categories in youth sport should be eliminated: insights from performance development of youth female long jumpers. Front. Physiol. 14, 1051208 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.W., B.U. and S.K.M. conceived the project and designed the experiments; S.K.M. collected data and performed empirical analyses; all authors discussed and interpreted results; S.K.M. and D.W. wrote the manuscript; all authors edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maity, S.K., Wang, Y., Dehmamy, N. et al. Early career setback and future achievement in professional sports. Sci Rep 15, 33505 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17271-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17271-z