Abstract

The deteriorating and unevenly distributed Li reserves lead to the quest for Li-ion battery’s alternatives.Hybrid metal-ion batteries are gaining attention as they effectively address the limited diffusion of heavier ions into cathode materials, typically involving the combination of multi and mono-valent metal-ions.The unavailability of high-performance cathode materials restricts the use of heavier ion (e.g., Zn2+) intercalation batteries even though they offer more stable anodic behavior and good charge capacity. In the present study, bilayer V2O5 nanosheets demonstrate exceptional performance as a cathode material for Zn-ion battery and Zn/Li hybrid metal-ion battery facilitating a faster conduit of ion diffusion. The Zn-ion battery and Zn/Lihybrid metal-ion battery showed high specific capacities of 270 and 510 mAh/g with fast charging rates of 0.77, and 0.6 A/g, respectively. Li+ is a lighter ion with an ionic radius of 0.76Å compared to the Zn2+ ion that of 0.74Å and hence has shown higher diffusion into the crystal. The introduction of Li+ in the hybrid metal-ion battery showed good cyclic performance with high coulombic efficiency. Thus, this study presents bilayer 2D V2O5 as a favorable cathode material for Zn-ion and Zn/Li hybrid metal-ion batteries for the first time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent advancements have broadened research possibilities in battery technology, particularly for large-scale energy storage, revealing new avenues for innovation. The discovery of secondary batteries, particularly the rechargeable Li-ion batteries, led to a revolution in portable consumer electronics and electric vehicles1. The discovery of the Li-ion technology proffered batteries withhighcharge capacity, power density, and longer lifespan. However, the fast depletion of Li reserves on the earth’s crust, high cost, and uneven geographic distribution of lithium resources are the challenges in using Li-ion battery technology for energy storage in large-scale. Hence, the need for the development of safer, cost-effective and environment friendly alternatives like, Zn-ion batteries are on the surge2. However, the critical bottleneck of using the Zn-ion battery is the lower ion diffusion rate and the unavailability of high performance cathode materials to achieve reversible intercalation/de-intercalation3.

Two-dimensional layered materials are characterized by strong covalent bonds within the layers and weak van der Waals forces holding the layers together4,5. As a result of this non-bonding nature of interlayer interaction, foreign species can be inserted without heavily distorting the in-plane covalent bonds. Ion intercalation batteries working with a principle of the reversible intercalation/de-intercalation process of ions, making 2D layered materials suitable for energy storage applications. The intercalation of these layered materials with certain molecules like H2O, and CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) increases the interlayer separation and results in the formation of ‘bulk monolayers’ which behaves like a monolayer even though existing in a stacked structure6,7. Such materials offer an easier and shorter diffusion pathway for the intercalation/de-intercalation process8. In addition, the high mechanical stability and electrochemical activity also make 2D materials suitable for ion intercalation batteries9.

α-V2O5 is an orthorhombic polymorph with its ab-layers connected along the c-axis through van der Waals interaction. The crystal structure of the V2O5 comprises three chemically inequivalent oxygen atoms; vanadyl (OI), bridge (OII), and chain (OIII) oxygen10. The layers are interconnected through OI and OII connects the double V–OIII chains (along the a-axis) to form the crystal structure along the b-axis. The layered crystal structure of V2O5, low-cost synthesis, less toxicity, and abundance on the earth’s crust make it a popular cathode material for ion intercalation batteries. The advantage of using V-based cathode materials for ion intercalation batteries is their ability for ‘multi electron transfer’ and high charge capacity, making a suitable host material for multi-valent ion intercalation alongside mono-valencies11. In addition, the abundance of this element on earth, different possible compositions, chemical structures, and electrochemical properties are also in favor. V2O5, a layered and stable material is known to exhibit ion intercalation/de-intercalation properties12. However, the development of a V2O5 based battery was challenging due to the phase transition of V2O5 to its polymorphs observed as a result of intercalation by molecules13. Hence, water-intercalated structures were developed forimprovedbattery performance by introducing an easier diffusion channel without inducing polymorphic phase transition14,15. However, owing to the difficulty in retaining the crystal structure during the synthesis of 2D oxides, the potential of 2D materials for ion intercalation battery applications has not been thoroughly researched.

In recent years, hybrid metal-ion batteries have gained attention as a potential replacement for single-ion batteries. Unlike conventional batteries, hybrid ion batteries utilize multiple types of metal-ions, such as Li, Zn, Na, and Mg, during charging and discharging, which sets them apart16,17,18. Generally, in a hybrid ion battery, the multi-valent cation undergoes deposition/dissolution on the anode and mono-valent cation intercalate/de-intercalate the lattice of cathode material16. As a result, hybrid ion batteries use dual salt electrolyteimproving the energy density and cycling stability16,19. Irrespective of the highest theoretical capacity (3860 mAh/g) of Li anode, the safety issues regulate the use of Li as anode material20. In addition, Li anode undergoes dendrite formation on the surface over recycling21. Whereas, Zn has higher volumetric capacity, abundance, smaller standard potential, low cost and toxicity22. But, the sluggish diffusion of Zn2+ into the host lattice generally results in lower discharge capacity and coulombicefficiency23. While using a hybrid ion battery offers the diffusion of lighter ions like Li+, using Zn as the anode, effectively improves the battery performance compared to Zn-ion battery. The hybrid metal-ion battery improvement in the discharge capacity, coulombic efficiency, and cycling stability24. The sole involvement of Li+ in the diffusion process in Zn/Li hybrid metal-ion battery due to the low diffusivity of Zn2+ is proven from the earlier operando X-ray diffraction studies23.While Zn/Li hybrid-ion batteries using porous V2O5 microplates as cathodes have demonstrated superior performance over conventional single-ion batteries19, the potential of ultra-thin 2D V2O5as cathode remains underexplored.The present study seeks to explore the applications of novel bilayer V2O5nanosheets in Zn-ion batteries and Zn/Li hybrid metal-ion battery systems.

Methods

Synthesis and characterization of 2D V2O5

Using chemical exfoliation technique, 2D V2O5 nanosheets were synthesized by controlling V2O5 concentration in the intercalating medium. Formamide is used as the intercalating agent following the previous studies25,26,27. For the synthesis, bulk V2O5 powder (Merck,99.99%) was added to formamide (Merck,99%) with a concentration of 1 mM. Following the insertion of formamide into the interlayer spaces of V2O5, which caused the crystal to swell. The dispersionwas then subjected to ultrasonic agitation at room temperature to exfoliate individual nanosheets from the bulk crystal. The suspension of exfoliated 2D V2O5 nanosheets was drop-coated onto carbon paper (used for creating the battery electrode) and subsequently heated at 100 °C to remove the formamidemolecules25.

The thickness of the exfoliated nanosheets deposited on a SiO2/Si substrate was measured, and the atomic force microscopy (AFM) topographic image was obtained using a multimode scanning probe microscope (NTEGRA, NT-MDT, Russia), operating in tapping mode. Atomic-resolution STEM images were captured using a probe aberration-corrected (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Themis Z) ultrahigh-resolution TEM at an acceleration voltage of 300 kV. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was conducted using a SPECS Surface Nano Analysis GmbH, Germany, system with a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (1486.7 eV). Raman spectroscopy was performed using an InVia instrument (Renishaw, UK) with a 532 nm Nd/YAG solid-state laser as the excitation source in back-scattering geometry. A thermoelectrically cooled charged-coupled device served as the detector, and an 1800 gr/mm grating was used for laser monochromatization. The optical band gap of the sample was determined through ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) absorption spectroscopy (Avantes) in absorption mode. Measurements were taken using a 1 cm wide cuvette to hold the sample in a reference medium, with Deuterium and Halogen lamps as the light sources.

Battery studies

A commercial potentiostat (PGSTAT 302 N, Metrohm Autolab e.v.) was used to investigate the battery performance of 2D V2O5 nanosheets at room temperature. The electrochemical cell for the aqueous Zn-ion battery was constructed using Zn metal as the counter electrode. The exfoliated V2O5 nanosheets were deposited onto carbon paper to create the working electrode. The carbon paper, with 2 cm length and 1.5 cm width, was uniformly coated with 3.6 ml of the sample dispersion solution (1 mM). The optical images of the bare carbon paper and 2D V2O5 coated carbon paper are shown in Figure S1a and b, respectively. The FESEM and EDS studies on the V2O5 coated carbon paper, showed a sufficient coating of 2D V2O5 on carbon (see supplementary Figure S2). From the amount of the coated solution, it can be calculated that, 0.648 mg of 2D V2O5 nanosheet sample was coated on the carbon paper. Aqueous solution of ZnSO4 with 1 M concentration is used as the electrolyte. The cyclic voltammogram (CV) was collected in the range of 0–2 V (V vs. Zn electrode). A schematic experimental arrangement is presented in the Fig. 1a.

The Zn/Li hybrid metal-ion battery with Zn metal anodewas made. Exfoliated V2O5 nanosheets on carbon paper was used as the cathode. Typically, a carbon paper with an area of 2 × 1.5 cm2was coated 4.8 ml of sample dispersion solution (1mM). Thus, the carbon paper was loaded with 0.864 mg of 2D V2O5 nanosheet sample. Zn(ClO4)2 with a 0.5 M concentration and LiClO4 with a 1 M concentration are combined to create a hybrid metal-ion electrolyte. The charging-discharging and cyclic voltammogram (CV) recording were performed in the range of 0.1–2.8 V (V versus Zn electrode) voltage range. Figure 1b shows the schematic of the experimental arrangement.

Results and discussion

Crystal tructure and morphology of chemically exfoliated V2O5

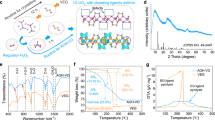

Atomic resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) images of the exfoliated nanosheets were collected for understanding the atomic structure and chemical composition. Figure 2a and b show dark field (DF) STEM image and atomic resolution integrated differential phase contrast(iDPC)-STEM image of 2D nanosheets. The DF-STEM image (Fig. 2a) shows the unsupported 2D nanosheets. The atomic resolution iDPC image (Fig. 2b) illustrates the arrangement of the VO5 square pyramidal structure in α-V2O5 along the (001) plane.

(a) Dark field STEM image of the 2D V2O5 sample, and (b) the atomic resolution iDPC (Integrated differential phase contrast)-STEM image of 2D nanosheets. (c) Raman spectrum of 2D V2O5 nanosheets. (d) AFM topography of 2D V2O5 nanosheets. The height profiles of the nanosheets obtained from the marked positions in the AFM images and the distribution of nanosheetthicknessesare also revealed in the figure. (e) XPS survey spectrum of the 2D V2O5 nanosheets. (f) Core level spectrum of the V2p state.

AFM studies were conducted on the exfoliated V2O5 sample to determine the thickness of nanosheets. An AFM image depicting the evenly dispersed layers can be seen in Fig. 2d. The Fig. 2d shows exfoliated nanosheets with lateral dimensions in the range of 100 to 300 nm. The step height is recorded using the experimental set-up with a standard deviation of 0.1 nm. According to the theoretical description of the crystal structure of monolayer, bilayer and, trilayer 2D V2O5, the layer thicknesses are ~ 0.43, 0.87 and, 1.3 nm, respectively25. The height profile of 2D V2O5 nanosheets (Fig. 2d) indicates that the experimentally measured thicknesses of the individual nanosheets fall between 1.0 and 1.5 nm. Figure 2d shows the thickness distribution of the nanosheets and it is evident that the ensemble of nanosheetsis majorly comprised of bilayer V2O5.

The Raman spectrum of the 2D V2O5 is collected to confirm the crystallographic phase of the material and is given in Fig. 2c. The sample exhibited nine vibrational modes corresponding to 2D V2O5. The theoretically predicted optic modes of monolayer V2O5 at the Γ point are, Γoptic = 3Au + 6B1u + 3B2u + 6B3u + 7Ag + 3B1g + 7B2g + 4B3g. Of these 39 vibrational modes, 21 are Raman active modes25. Out of the 21 Raman active modes, we have observed eight vibrational modes at 111 (A1g1), 162 (B1g1), 267 (B3g), 324 (B2g), 493 (A1g2), 539 (A1g3), 711 (B1g2), 1010 (A1g4) cm−1. The A1g1 and B1g1vibrational modes originate from the chain translation along crystallographic c and a-axes. The mode B3g is due to V‒OII‒V bending and deflection of V‒OI along a direction. The deflection of V‒OIII and V‒OIII′ along the c direction causes the vibrational mode B2g1. The origin of the A1g2 mode is the bending of V‒OII‒V in thec direction. The deflection of V‒OIII′ and V‒OIII along a direction results in the vibrational mode B1g2. The highest frequency A1g4 mode corresponds to the stretching vibration of V‒OI along the c-axis. This out-of-plane mode shows a considerable blue-shift in energy from the value corresponds to bulk V2O5, stems from the stiffening of V‒OI bond upon decrease in thickness25. The peak at 620 cm−1 is a surface mode that appears due to the presence of surface oxygen vacancies, leading to a local reduction of surface25,27.

The XPS survey spectrum of bilayer V2O5 is shown in Fig. 2e. The sample showed peaks at 517.4, 524.8, and 530.1 eV corresponding to V2p3/2,V2p1/2,and O1s, respectively, confirming the existence of V2O5phase28. The deconvolution of core level spectrum revealed two peaks at 517.4 and 516.3 eV(Fig. 2f), which correspond to the binding energy of V2p3/2 for V5+ and V4+ states, respectively.Similarly, 524.8 and 523.1 eV are the peaks characteristic of the binding energies of V2p1/2 for the V5+ and V4+ states, respectively28. The observation of the peaks corresponding to V4+ in XPS is an indicative of the presence of oxygen vacancy, which is also evident from the Raman spectrum. The oxygen vacancy defects in bilayer V2O5were calculated using the area under the curve, which is 17%. The surface activity and, hence, the catalytic property of the sample may be enhanced by the presence of these oxygen vacancy sites.

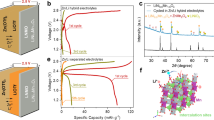

Aqueous Zn-ion battery using bilayer 2D V2O5 as cathode

Figure 3a displays the cyclic voltammogram (CV), recorded from the sample at a scanning rate of 10 mV/sec.The CV curves showed reduction and oxidation peaks at 0.56, 0.9 and1.1, 0.75 V, respectively. These peaks originate from redox reactions following the intercalation/de-intercalation of Zn2+ into the V2O5 nanosheets. When Zn2+ is intercalated into (the battery is discharged) the interlayer spacing of the nanosheets, the V5+ atoms in the crystal are reduced to V4+, whereas, de-intercalation (or charging) causes the reduced V4+ to oxidize to V5+.The half-cell reactions of the Zn-ion battery during the charging and discharging processes are as follows,

In discharging process, Zn → Zn2++ 2e−(Anode reaction).

V(5+)2O5+ Zn2+ + 2e− → ZnV(4+)2O5(Cathode reaction).

For charging, ZnV(4+)2O5 → V(5+)2O5+ Zn2++ 2e−(Cathode reaction).

Zn2++2e− → Zn (Anode reaction).

If there are ‘z’ number of electrons transferred, the theoretical specific charge capacity (SCC) of a material is,

Where, F is the Faraday’s constant and M is the molecular mass of the cathode material. When two electrons are transferred during intercalation, the V5+ reduces to V4+ and the theoretical charge capacity is 295 mAh/g. When further intercalation of ions happens, V5+ undergoes reduction to V3+ (or V2+), and there are four (or six) electrons are transferred during charging/discharging process. The maximum theoretical SCC for V2O5 with z = 4 and z = 6 are 590 mAh/g and 875 mAh/g, respectively. For bulk V2O5 cathode, reduction to V3+ (or V2+) is less likely to occur, due to the possible structural instability. But the stiffening of several in-plane and out-of plane bonds as observed from the Raman spectrum of 2D V2O525 indicates that the structure can be more stable upon redox reactions. The stiffening of the bonds results from the less screening and more localized bonding, providing more structural stability and a possible deeper reduction. In addition to that, a highly recyclable catalytic performance and enhanced gas sensing with excellent recovery by bilayer V2O527,29 also indicates the stability of 2D V2O5 upon redox reactions. Figure 3b shows the corresponding change in the SCC with different current densities. The SCC of the battery is calculated from the charge/discharge profile using the formula,

WhereI, t, and m are current and time of charging/discharging, and the mass of active material, respectively. The SCC decreases in the first few charge/discharge cycles before stabilizing after several cycles. The reduction in the SCC may result from the detachment of weakly bonded active material from the substrate. The exfoliated 2D V2O5 showed a discharge capacity of 263 mAh/g with a fast charging rate of 4 A/g. According to the existing studies, the Zn-ion battery with V2O5 under high current densities comparable to the present study showed a SCC of less than 200mAh/g. It is understood that the cathode material property determines the enhanced battery performance. The cathode material of 2D V2O5 nanosheets contains bilayer and trilayer nanosheets. The nanosheets thicknesses are in the 1.0-1.5 nm range. This material exhibits an optical band gap of 3.55 eV, as shown in supplementary Figure S3. Irrespective of the band gap value, electric conduction is possible for the material through an electron hopping mechanism in ab- plane of V2O5 with O-vacancy defects. Ion diffusion into the crystal results in the formation of reduced vanadium states to maintain charge neutrality, and as a result, electron-polarons are generated. The electron hopping between V2(+ 4)O4 and V2(+ 5)O5 (Polaron hopping) is least favorable along [010] direction30. Also, it is theoretically proven that the interlayer conductivity is lesser than the intralayer conductivity31,32.XPS studies confirm the existence of O-vacancy defects in the sample. The exfoliated 2D V2O5 shows a high electrochemically active specific surface area of 211 m2/g, which is ~ 30 times larger than that of bulk V2O529,33.

The Fig. 3b exhibits the SCC and columbic efficiency with the number of charge/discharge cycles. The value of coulombic efficiency (η) of a battery (the ratio of discharging and charging specific capacity) quantitatively indicates the number of Zn2+ that remains inside the active material in the duration of de-intercalation process. The Zn-ion battery showed a good η of ~ 96% during the first few cycles. The coulomb efficiency is observed to gradually increase from 96 to 99%, indicating that the active material forms a stable intercalation/de-intercalation characteristics after ~ 300 cycles. The columbic efficiency is observed to increase gradually from 96.7% to ~ 99% over first 300 cycles. From 500th cycle the columbic efficiency stayed consistently in the range of 98.5–100% with an average of 99%, where a capacity retention of ~ 85% is observed even with a lower columbic efficiency of 99%. The Zn2+ is a comparatively heavier ion with an ionic radius of 0.74Å. As a result, some of the intercalated ions form stronger chemical bonds with the host lattice and reside inside the crystal lattice of active cathode material during de-intercalation34. Hence, a lower columbic efficiency and capacity reduction is innate to Zn-ion batteries. A lower value of η is generally observed for Zn-ion batteries in comparison with Li-ion batteries, owing to the slow Zn2+desolvation and diffusion leading to poor Zn2+ kinetics23. Irrespective of this intrinsic limitation bilayer 2D V2O5 cathode showed a good η and cyclic performance as a result of an easier diffusion pathway, offered by the increased interlayer separation. In addition, the observations persuasively indicates the structural stability of the electrode material. The charge-discharge profiles for various cycles of the Zn-ion battery performance is provided in the Figure S4 in the supplementary information.

The useful lifetime of a battery is prevalently determined by its charge capacity retention. Capacity retention is the percentage of initial discharge capacity retained after a number of charge/discharge cycles. In the present study of Zn-ion battery using 2D V2O5, upto 500 cycles, a capacity retention of 53% is observed due to the gradual increase in the columbic efficiency from 96 to 99%. The next 500 cycles, showed an average columbic efficiency of 99% and capacity retention of 84%. The comparatively good capacity retention shown by the 2D V2O5-based Zn-ion battery indicates that the cathode material is highly stable under the intercalation/de-intercalation process.

Zn/Li hybrid metal-ion battery using bilayer 2D V2O5 as cathode

Figure 4a shows the cyclic CV corresponding to the Zn/Li hybrid metal-ion battery with a scanning rate of 10 mV/sec. The CV diagram evinced reduction peaks at 0.6, 0.9, and 1.2 V. The oxidation peaks were shown at 0.56, 1.1, 1.4, and 2.4 V. As, described earlier, the redox peaks are the implication of intercalation/de-intercalation of Li+ into the cathode material. The V5+ atoms in the crystal are reduced to V3+ (when the number of charges involved in intercalation/de-intercalation process, z = 4) or V4+ (for z = 2) when Li+ is intercalated into the crystal. Further, the reduced V3+ or V4+ ions are oxidized to V5+in the duration of de-intercalation process. From these information, one can represent the half-cell reactions of the battery for charging and discharging as33,

In the discharging process, xZn → xZn2++ 2xe̶ (Anode reaction).

V2O5 + 2xLi++2xe̶→ Li2xV((5−x)+)2O5 (Cathode reaction).

For charging, Li2xV((5−x)+)2O5 → V2O5 + 2xLi++2xe ̶. (Cathode reaction).

xZn2++ 2xe ̶ → xZn (Anode reaction).

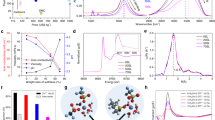

Figure 4b displays the charge/discharge characteristics for the Zn-ion and Zn/Li hybrid ion batteries. Equation 2 is used to determine the SCC of the battery.Along with the increase in operating voltage, Fig. 4b shows that, for Zn/Li hybrid metal-ion battery, the SCC has approximately doubled from that of the Zn-ion battery. This increase in specific capacity indicates a deeper reduction of V5+ to V3+ during ion intercalation. TheZn/Li hybrid metal-ion battery has a better power density compared to Zn-ion battery due to their higher operating voltage range, which is also a key parameter for characterizing the battery performance. The Fig. 4c shows SCC and ηof the battery as a function of the number of charge/discharge cycles. The augmented battery performance is because of the availability of Li+ for intercalation. Li+ is a lighter ion with an ionic radius of 0.76Å compared to the Zn2+ (ionic radius of Zn2+being 0.74Å). As a result, the ion diffusion into the crystal increases. With respective current densities of 5.7, 5.2, and 0.6 A/g, the specific charge capacities of the battery is determined to be 410.5, 450, and 510 mAh/g using Eq. 2. The SCC of the battery is higher with a lower current density. The observation is due to the enhanced interaction of the ion with the cathode materials at a slow charging rate (or lower current density). The working potential of the Zn/Li hybrid ion battery resembles that of a Li-ion battery with V2O5 cathode (Fig. 4b), which is higher than that of Zn-ion battery. A high working potential is necessary for achieving high energy density. The sole involvement of Li+in the intercalation/de-intercalation is proven by the XPS studies on the ion intercalated cathode material. The XPS survey spectrum shown in Fig. 5a did not show the signature of Zn2+ intercalation in the cathode material. The XPS peak at 56.2 eV in the high resolution spectrum (Fig. 5b) corresponded to the binding energy of Li1s (intercalated) state35, indicating the intercalation of Li-ion in V2O5. The very weak intensity of the peak is due to the low structure factor of Li. The working potential also indicates the intercalation of the Li+ in the cathode, not the Zn2+. The core level spectra of V are also studied to understand the changes in the valence states and the spectra are provided in the Figure S5 in the supplementary information. The analysis showed that the cathode material undergone reduction upon intercalation. The specific capacities from prior literature with comparable current densities (which is a measure of the charging/discharging rate) are compared with the present findings (Fig. 6).The comparison shows the specific capacity of the Zn/Li hybrid metal-ion battery is notably higher comparing to the vanadium oxide-based Zn-ion batteries with a fast charging current density of 0.6 mAh/g.

The η is calculated as described in the previous section of the Zn-ion battery. Figure 4c shows the values of η with increasing number of charge/discharge cycles. The charging-discharging upto 1000 cycles are carried out with the Zn/Li hybrid ion battery. The charge/discharge process is carried out with a current density of 5.7 A/g. A high ηof around 99% was demonstrated by the battery from the first cycle upto the 1000th cycle. The lighter Li ion generally shows high ηderived from the easier intercalation/deintercalation compared to other metal-ions50. Thus, a hybrid metal-ion battery improves all of specific charge-capacity along with ηand cyclic stability. In addition, as it was evident from the Zn-ion battery study, bilayer V2O5 cathode offers an energetically favorable diffusion pathway improving intercalation/de-intercalation process. An ex-situ structural characterization of the 2D V2O5 coated carbon paper was done using Raman spectroscopy, after 1000 charge/discharge cycles of Zn-ion and Zn/Li hybrid ion battery. The Raman spectra of 2D V2O5 after 1000 charge/discharge cycles of Zn/Li hybrid ion and Zn-ion battery are shown in Fig. 7a and b, respectively. It can be elucidated from the results that the 2D V2O5 exceeds bulk limits due to enhanced kinetics and structural stability. The charge-discharge profiles of the Zn/Li hybrid metal-ion battery for several cycles are shown in Figure S6 in the supplementary information.

Considering the discharging specific capacity of the Zn/Li hybrid ion battery, it showed an 89% capacity retention up to 14 cycles. After the 15th cycle, up to the 214th cycle, the SCC showed 98% retention and after the 215th cycle until the 1000th cycle the battery showed capacity retention of ~ 100%. A similar decrease in SCC observed in Zn-ion battery is also shown by Zn/Li hybrid metal-ion battery. The observations further supports the high structural stability upon intercalation process, as observed in the case of Zn-ion battery.

Conclusions

The bilayer 2D V2O5 nanosheets were tested for ion intercalation battery application. As the cathode in a Zn-ion battery, the two-dimensional V2O5nanosheets delivered a specific charge capacity of 263 mAh/g and supported fast charging at 4 A/g, showing a capacity retention ~ 50% over 1000 cycles. An increase in the interlayer separation, resulting with the increase in the bilayer thickness formed in the chemical exfoliation process provided an easier conduit for ionic diffusion. The charge transport through the V2O5 cathode is envisaged to be manifested through the polaron hopping mechanism. Additionally, the bilayer V2O5 nanosheets served as cathode material in a hybrid metal-ion battery, where Zn ions participated in dissolution (or deposition) while Li ions were involved in intercalation (or de-intercalation). The Zn/Li hybrid metal-ion battery demonstrated a notable specific capacity of 510 mAh/g at a charging rate of 0.6 A/g. By incorporating lighter Li⁺ ions, the battery exhibited excellent cycling stability, maintaining a high coulombic efficiency (η) of approximately 100% across 1000 charge/discharge cycles. It is observed in the present study that the novel bilayer V2O5 is stable under a deeper reduction and showed high-performance as the cathode material, which has high SCC with fast charging and long battery life.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Voronina, N., Sun, Y. K. & Myung, S. T. Co-Free layered cathode materials for high energy density Lithium-Ion batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 5 (6), 1814–1824. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.0c00742 (2020).

Liu, S. et al. Recent advances and perspectives of Battery-Type anode materials for potassium ion storage. ACS Nano. 15 (12), 18931–18973. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.1c08428 (2021).

Jia, X., Liu, C., Neale, Z. G., Yang, J. & Cao, G. Active materials for aqueous zinc ion batteries: synthesis, crystal structure, morphology, and electrochemistry. Chem. Rev. 120 (15), 7795–7866. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00628 (2020).

Chen, P., Zhang, Z., Duan, X. & Duan, X. Chemical synthesis of two-dimensional atomic crystals, heterostructures and superlattices. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47 (9), 3129–3151. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7CS00887B (2018).

Choi, W. et al. Recent development of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides and their applications. Mater. Today. 20 (3), 116–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mattod.2016.10.002 (2017).

McArdle, G. & Lerner, I. V. Electron-phonon decoupling in two dimensions. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 24293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03668-z (2021).

Kempt, R., Kuc, A., Han, J. H., Cheon, J. & Heine, T. 2D crystals in three dimensions: electronic decoupling of Single-Layered platelets in colloidal nanoparticles. Small 14 (51), 1803910. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201803910 (2018).

Riyanto, E., Kristiantoro, T., Martides, E., Dedi, Prawara, B. & Mulyadi, D. Suprapto. Lithium-ion battery performance improvement using two-dimensional materials. Materials Today: Proceedings 87, 164–171 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.02.392

He, Y., Shen, X. & Zhang, Y. Layered 2D materials in batteries. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 7 (24), 27907–27939. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.3c06242 (2024).

Jovanović, A. et al. Structural and electronic properties of V2O5 and their tuning by doping with 3d elements – modelling using the DFT + U method and dispersion correction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20 (20), 13934–13943. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8CP00992A (2018).

Ma, C. & Zhou, B. E. Properties and mechanical stability of Multi-Ion-Co-Intercalated bilayered V2O5. Materials 17 (13), 3364. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17133364 (2024).

Fu, Q., Zhao, H., Sarapulova, A. & Dsoke, S. V2O5 as a versatile electrode material for post-lithium energy storage systems. Appl. Res. 2 (3), e202200070. https://doi.org/10.1002/appl.202200070 (2023).

Ki, P. S. et al. Electrochemical and structural evolution of structured V2O5 microspheres during Li-ion intercalation. J. Energy Chem. 55, 108–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jechem.2020.06.028 (2021).

Yang, Y. et al. Li+ intercalated V2O5·nH2O with enlarged layer spacing and fast ion diffusion as an aqueous zinc-ion battery cathode. Energy Environ. Sci. 11 (11), 3157–3162. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8EE01651H (2018).

Tian, B., Tang, W., Su, C. & Li, Y. Reticular V2O5·0.6H2O xerogel as cathode for rechargeable potassium ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 10 (1), 642–650. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b15407 (2018).

Walter, M., Kravchyk, K. V., Ibáñez, M. & Kovalenko, M. V. Efficient and inexpensive Sodium–Magnesium hybrid battery. Chem. Mater. 27 (21), 7452–7458. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b03531 (2015).

Pan, W. et al. High-Performance aqueous Na–Zn hybrid ion battery boosted by Water-In-Gel electrolyte. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31 (15), 2008783. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202008783 (2021).

Koleva, V., Kalapsazova, M., Marinova, D., Harizanova, S. & Stoyanova, R. Dual-Ion intercalation chemistry enabling hybrid Metal-Ion batteries. ChemSusChem 16 (4). https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.202201442 (2023). e202201442.

Hu, P. et al. Zn/V2O5 aqueous Hybrid-Ion battery with high voltage platform and long cycle life. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 9 (49), 42717–42722. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b13110 (2017).

Pender, J. P. et al. Electrode degradation in Lithium-Ion batteries. ACS Nano. 14 (2), 1243–1295. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.9b04365 (2020).

Han, X. et al. Operando monitoring of dendrite formation in lithium metal batteries via ultrasensitive Tilted fiber Bragg grating sensors. Light: Sci. Appl. 13 (1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-023-01346-5 (2024).

Shinde, S. S. et al. Zn, al, and Ca anode interface chemistries developed by Solid-State electrolytes. Adv. Sci. 10 (32), 2304235. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202304235 (2023).

Hao, J. et al. Toward High-Performance hybrid Zn-Based batteries via deeply Understanding their mechanism and using electrolyte additive. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29 (34), 1903605. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201903605 (2019).

Yang, Z. et al. Rechargeable Sodium-Based hybrid Metal-Ion batteries toward advanced energy storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31 (8), 2006457. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202006457 (2021).

Reshma, P. R. et al. Electronic and vibrational decoupling in chemically exfoliated bilayer thin Two-Dimensional V2O5. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12 (40), 9821–9829. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c02637 (2021).

Rui, X. et al. Ultrathin V2O5 nanosheet cathodes: realizing ultrafast reversible lithium storage. Nanoscale 5 (2), 556–560. https://doi.org/10.1039/C2NR33422D (2013).

Reshma, P. R., Prasad, A. K., Dhara, S. Novel bilayer 2D V2O5 as a potential catalyst for fast photodegradation of organic dyes. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 14462. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65421-6 (2024).

Wu, Q. H., Thissen, A., Jaegermann, W. & Liu, M. Photoelectron spectroscopy study of oxygen vacancy on vanadium oxides surface. Appl. Surf. Sci. 236 (1), 473–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2004.05.112 (2004).

Reshma, P. R. & Prasad, A.K. Highly selective room temperature detection of NO. Enabled Vanadyl Oxygen Vacancies Novel Bilayer V2O5 Talanta Open. 12, 100497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talo.2025.100497 (2025).

Hu, B. et al. Bimetallic ions pre-intercalated hydrated vanadium oxides for high-performance aqueous zinc-ion batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 1008, 176801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.176801 (2024).

Watthaisong, P., Jungthawan, S., Hirunsit, P. & Suthirakun, S. Transport properties of electron small polarons in a V2O5 cathode of Li-ion batteries: a computational study. RSC Adv. 9 (34), 19483–19494. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9RA02923K (2019).

Watthaisong, P., Jungthawan, S., Hirunsit, P. & Suthirakun, S. Ab initio study of electron mobility in V2O5 via Polaron hopping. Solid State Electron. 198, 108455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sse.2022.108455 (2022).

Reshma, P. R. 2D V2O5 nanosheets for photocatalytic and advanced energy storage applications. IGC Newsletter 133, 4–8 (2022). https://www.igcar.gov.in/newsletter/igc133.pdf

Sun, D. et al. Oxygen-deficient znvoh@cc as high-capacity and stable cathode for aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 496, 154300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.154300 (2024).

Światowska-Mrowiecka, J., Maurice, V., Zanna, S., Klein, L. & Marcus, P. XPS study of Li ion intercalation in V2O5 thin films prepared by thermal oxidation of vanadium metal. Electrochim. Acta. 52 (18), 5644–5653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2006.12.050 (2007).

Xu, T. et al. Investigating architectured Na3V2(PO4)3/C/CNF hybrid cathode in aqueous zinc ion battery. Energy Fuels. 35 (19), 16194–16201. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.1c02586 (2021).

JoJ, H., Sun, Y. K. & Myung, S. T. Hollandite-type Al-doped VO1.52(OH)0.77 as a zinc ion insertion host material. J. Mater. Chem. A. 5 (18), 8367–8375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2023.156704 (2017).

Zhu, J. et al. A highly stable aqueous Zn/VS2 battery based on an intercalation reaction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 544, 148882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.148882 (2021).

Zhou, J. et al. Investigation of V2O5 as a low-cost rechargeable aqueous zinc ion battery cathode. Chem. Commun. 54 (35), 4457–4460. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8CC02250J (2018).

Pang, Q. et al. High-Capacity and Long-Lifespan aqueous LiV3O8/Zn battery using zn/li hybrid electrolyte. Nanomaterials 11 (6), 1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11061429 (2021).

Kaveevivitchai, W. & Manthiram, A. High-capacity zinc-ion storage in an open-tunnel oxide for aqueous and nonaqueous Zn-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 4 (48), 18737–18741. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6TA07747A (2016).

Qi, Z. et al. Harnessing oxygen vacancy in V2O5 as high performing aqueous zinc-ion battery cathode. J. Alloys Compd. 870, 159403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.159403 (2021).

Tong, Y. et al. Hydrated lithium ions intercalated V2O5 with dual-ion synergistic insertion mechanism for high-performance aqueous zinc-ion batteries. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 606, 645–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2021.08.051 (2022).

Javed, M. S. et al. W. 2D V2O5 nanosheets as a binder-free high-energy cathode for ultrafast aqueous and flexible Zn-ion batteries. Nano Energy. 70, 104573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2020.104573 (2020).

Yoo, G., Koo, B-R. & An, G. H. Nano-sized split V2O5 with H2O-intercalated interfaces as a stable cathode for zinc ion batteries without an aging process. Chem. Eng. J. 434, 134738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2022.134738 (2022).

Jiang, H. et al. Quench-tailored Al-doped V2O5 nanomaterials for efficient aqueous zinc-ion batteries. J. Energy Chem. 70, 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jechem.2022.02.030 (2022).

Song, Z. et al. Organic intercalation induced kinetic enhancement of vanadium oxide cathodes for Ultrahigh-Loading aqueous Zinc-Ion batteries. Small 20 (1), 2305030. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202305030 (2024).

Zhou, T., Du, X. & Gao, G. Revealing the role of calcium ion intercalation of hydrated vanadium oxides for aqueous zinc-ion batteries. J. Energy Chem. 95, 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jechem.2024.03.022 (2024).

Feng, Z. et al. Construction interlayer structure of hydrated vanadium oxides with tunable P-band center of oxygen towards enhanced aqueous Zn-ion batteries. Adv. Powder Mater. 3 (2), 100167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmate.2023.100167 (2024).

Memarzadeh, L. E. et al. ALD TiO2 coated silicon nanowires for lithium ion battery anodes with enhanced cycling stability and coulombic efficiency. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15 (32), 13646–13657. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3CP52485J (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank K Ganesan for the AFM studies and Shyam Kanta Sinha and Arup Das Gupta for the TEM studies. The authors also thank Tom Mathews for fruitful discussions.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Department of Atomic Energy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The central idea was conceived by R.P.R., L.C. and A. K. P. Sample synthesis, characterization, were carried out by R.P.R. The planning and excecution of electrochemical studies were carried out by R.P.R. and L.C. The data analysis and manuscript writting were done by R.P.R. All the authors discussed the results and the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary data

FESEM and EDS studies on the cathode (2D V2O5deposited on carbon paper), UV-Vis absorption study of bilayer V2O5,charge-discharge profile of Zn-ion battery, XPS studies on ion intercalated cathode of Zn/Li battery,and charge-discharge profile of Zn-ion battery.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reshma, P.R., Lakshmanan, C., Prasad, A.K. et al. High performance bilayer 2D V2O5 cathode for Zn-ion and Zn/Li hybrid metal-ion intercalation battery. Sci Rep 15, 31543 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17294-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17294-6