Abstract

Motor Current Signature Analysis (MCSA) faces considerable challenges in diagnosing mechanical faults in motors, particularly in accurately detecting misalignment in rotating machinery. Traditional vibration-based methods often suffer from high hardware costs and difficulties associated with sensor installation. To address these limitations, this study proposes an intelligent diagnosis method for radial misalignment in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (PMSMs) based on Swin-BiGRU multimodal fusion using current signals. First, Adaptive Variational Mode Decomposition (AVMD) is applied to the collected three-phase current signals to eliminate high-frequency noise. Considering the inherent difficulty of fault feature extraction in current signals, Markov Transition Fields (MTF) are used to transform one-dimensional time-series current data into time–frequency images, thereby highlighting subtle or weak fault signatures. The proposed framework employs a dual-branch network: one branch utilizes the Swin Transformer to extract deep features from MTF images, while the other adopts a Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (BiGRU) with Global Attention (GATT) to model the original current time-series. After feature extraction, a bidirectional Cross-Attention mechanism is introduced to enable efficient interaction and enhancement between the multimodal features, improving both diagnostic accuracy and robustness. To validate the proposed method, ablation studies and comparative experiments were conducted before and after denoising. Experimental results demonstrate that under radial misalignment conditions ranging from 0.5 mm to 1.5 mm, the proposed method achieves an average diagnostic accuracy of 99.375%. Even without the AVMD denoising step, the method maintains a high accuracy of 98.125%, outperforming other benchmark methods. In industrial settings, this method can be integrated into automated equipment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (PMSMs), renowned for their high efficiency and reliability, are widely used in the fields of renewable energy and industrial drives1. However, during prolonged operation, their rotating mechanical systems are prone to mechanical faults such as misalignment. Misalignment faults often stem from installation errors, external impacts, or uneven thermal expansion during operation, leading to wear and damage in critical components such as bearings, couplings, and gears. These issues ultimately reduce system efficiency and may even result in catastrophic failures. Therefore, developing an intelligent diagnosis method for misalignment faults that is both efficient and cost-effective, and well-suited for practical industrial applications, holds significant engineering value.

At present, mainstream research on fault diagnosis of rotating machinery primarily relies on vibration analysis techniques2,3,4,5,6,7, such as acquiring vibration signals using accelerometers or proximity probes. While this approach offers high sensitivity in detecting mechanical faults, it faces several limitations in practical industrial applications. In particular, the reliance on external sensors increases hardware costs, complicates installation and maintenance, and the acquired signals are often affected by sensor placement errors8,9,10,11. As a non-intrusive alternative, Motor Current Signature Analysis (MCSA)12,13 has attracted significant attention. By integrating current sensors into motor drive control systems, MCSA enables low-cost, highly integrated data acquisition and real-time fault diagnosis. Common MCSA techniques include Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), wavelet transform, and load torque feature analysis14,15,16,17, which are used to isolate and identify fault-related features. For example, Yao et al.18 constructed a VPT spectrum based on load torque analysis to classify misalignment faults. Lee et al.19 applied FFT to analyze harmonic features in stator current signals for misalignment detection. Shi et al.20 proposed a non-intrusive load monitoring approach combining adaptive scaling recurrence plots with a Swin-Transformer, effectively enhancing the accuracy of load identification from current signals without additional vibration sensors. These developments demonstrate that MCSA can serve as an effective alternative to vibration-based methods, particularly when sensor deployment is constrained.

However, traditional MCSA methods often struggle in diagnosing misalignment faults in rotating machinery due to the influence of load disturbances and electromagnetic coupling on current signals. These factors result in extremely weak fault characteristics, making it difficult for conventional signal processing techniques to accurately and reliably extract and identify meaningful features, thus limiting diagnostic accuracy. To overcome this technical bottleneck, recent studies have explored the integration of deep learning with advanced signal processing techniques to enhance diagnostic robustness and precision. For instance, Wang et al.21 proposed a convolutional neural network–support vector machine (CNN-SVM) approach based on motor current signals, achieving high-accuracy diagnosis of rolling bearing faults. Verma et al.22 employed a combination of multiscale entropy (MSE) and a backpropagation neural network (BPNN) to detect shaft misalignment faults in asynchronous motors using both vibration and current signals. Similarly, Li et al.23 developed an adaptive convergent view-graph contrastive learning framework for multi-sensor fusion in wind turbine bearing fault diagnosis, effectively enhancing generalization under complex operating conditions. Li et al.24 further proposed an energy-propagation graph neural network (EPGNN) to improve out-of-distribution fault analysis by modeling energy transfer across system components, demonstrating strong adaptability to unseen fault types. Li et al.25 proposed a graph causal intervention–based adaptive expert ensemble (GCI-ODG) framework that learns stable, environment-invariant features without explicit environmental labels, significantly improving out-of-distribution generalization and diagnostic robustness in complex industrial conditions. Shang et al.26 introduced a cross-domain motor fault diagnosis method using bimodal inputs of vibration and current signals with a Resformer architecture, achieving high robustness and noise resistance under variable load conditions. Chen et al.27 developed an instantaneous square current value–Vision Transformer (ISCV-ViT) framework to enhance rolling bearing fault diagnosis solely from current signals, addressing the low signal-to-noise ratio challenge and achieving high accuracy across multiple datasets. Dai et al.28 developed a bearing fault diagnosis framework that integrates Pelican Optimization Algorithm–based Variational Mode Decomposition (POA-VMD) with a Gram Angular Difference Field (GADF)–Swin Transformer transfer learning model, significantly improving diagnostic performance under limited training data. Liu et al.29 presented a gearbox fault diagnosis method leveraging Markov Transition Fields and Swin Transformer networks, enabling precise extraction of temporal–spatial features from vibration signals for robust classification. Nevertheless, despite the rapid progress of deep learning, the adoption of multi-modal fusion approaches that combine Transformer architectures with sequence modeling remains relatively limited in the MCSA domain—particularly for diagnosing PMSM misalignment faults. There is a pressing need for further research into effective strategies for integrating time–frequency features with sequential representations to enhance diagnostic accuracy and robustness.

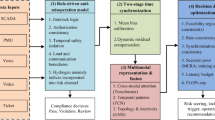

To address the limitations of traditional MCSA approaches in diagnosing mechanical faults—particularly the low diagnostic accuracy and sensor deployment challenges—this study proposes a novel intelligent diagnosis method for radial misalignment faults in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (PMSMs) based on Swin-BiGRU multimodal fusion using current signals. Built upon real-world three-phase current data collected from PMSMs under various misalignment conditions, the proposed method is capable of accurately identifying and classifying subtle mechanical faults without relying on additional vibration sensors. This significantly reduces hardware complexity and cost while enhancing system integration and practical applicability. The core contributions of this work are fivefold. First, we develop a multimodal intelligent diagnostic framework that eliminates the need for external vibration sensors by solely utilizing current signals, thereby simplifying the electromechanical system architecture and improving industrial scalability. Second, we design an integrated preprocessing pipeline that combines Adaptive Variational Mode Decomposition (AVMD) for effective denoising and Markov Transition Field (MTF) transformation for time–frequency representation. This pipeline enhances the extraction of weak misalignment features embedded in noisy current signals, improving the model’s sensitivity to subtle fault patterns. Third, we construct a dual-branch neural architecture, in which a Swin Transformer is employed to extract deep hierarchical features from MTF images, while a Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (BiGRU) network, equipped with a Global Attention mechanism, captures the temporal dynamics of the raw current time series. This parallel design enables comprehensive modeling of both spatial and temporal information inherent in the current signals. Fourth, we introduce a bidirectional Cross-Attention mechanism to fuse the features extracted from the image and time-series modalities. This mechanism facilitates deep interaction and complementarity between heterogeneous feature spaces, significantly boosting the robustness and accuracy of radial misalignment fault detection in PMSMs. Fifth, the proposed method incorporates a mechanism-constrained structured integration strategy, in which each network module is aligned with the physical mechanisms and statistical properties of radial misalignment faults. This design ensures architectural coherence and improves the discriminability of fault-related features.

The structure of this paper is as follows: section "Methods" presents the theoretical background; section "Experiments" details the experimental design and validates the performance advantages of the proposed method; Sect. 4 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

Methods

Markov transition field

Markov Transition Field (MTF)30 is a technique for transforming a one-dimensional time series into a two-dimensional matrix, where image pixels are encoded using Markov transition probabilities.

Assume a time series \(X = \left\{ {x_{1} ,x_{2} , \ldots ,x_{t} , \ldots ,x_{N} } \right\}\) where \(x_{i} \left( {i = 1,2, \ldots ,N} \right)\) (\(x_{i}\)) represents the amplitude of the current signal at time i. The first step involves discretizing the time series X into Q quantile bins. Each value xi is mapped to a corresponding quantile unit \(q_{j} \left( {q_{j} \in \left[ {1,,Q} \right]} \right)\) according to its amplitude. Using the single-step and multi-step transition probabilities defined in the Markov chain to characterize the sequential relationships, as expressed in Eq. (1):

In the equation, \({P}_{ij}\) denotes the multi-step transition probability, representing the probability that an element currently located in the quantile region \({q}_{j}\) will, after multiple steps, transition to the quantile region \({q}_{i}\). By mapping the amplitude of the time-series signal into Q discretized quantile units distributed across the entire amplitude range, the continuous time series can be represented as a quantile sequence \({\{q}_{{j}_{1}}{,q}_{{j}_{2}}{,\dots ,q}_{{j}_{N}}\}\). By statistically analyzing the transitions between quantile units at each time step, the specific transition probabilities can be obtained. Arranging all possible transition probabilities in the Markov chain in accordance with their transition rules yields a Q × Q weighted adjacency matrix (i.e., the Markov transition probability matrix), as shown in Eq. (2). The construction of the Markov transition probability matrix is fully determined by the Markov chain’s multi-step transition probabilities, indicating a strong correspondence between the two.

A Markov chain has the property of being memoryless: the probability of transitioning to the current state depends only on the previous state, i.e., it satisfies \(p\left( {x_{t} \in \mathop \sum \limits_{j = 1}^{Q} q_{j} |x_{t - 1} \in \mathop \sum \limits_{j = 1}^{Q} q_{j} , \ldots ,x_{1} \in \mathop \sum \limits_{j = 1}^{Q} q_{j} } \right) = p\left( {x_{t} \in \mathop \sum \limits_{j = 1}^{Q} q_{j} |x_{t - 1} \in \mathop \sum \limits_{j = 1}^{Q} q_{j} } \right)\). Therefore, the Markov transition probability matrix constructed from a Markov chain is also memoryless, which completely ignores the temporal dependency of the sequence X. If we directly use the Markov transition probability matrix, it will lead to the loss of a large amount of information from the multi-dimensional time-domain sequence X. In contrast, the improved Markov transition field arranges the sequence according to its temporal order, effectively utilizing the temporal information and overcoming the problem of losing time-related information. The specific definition of the Markov transition field is given by Eq. (3):

In the equation, \({p}_{i,j}\) denotes the transition probability corresponding to the quantile relationship between \({q}_{i}\) and \({q}_{j}\) in the Markov transition probability matrix T, where the diagonal elements represent the self-transition probabilities. Consequently, the probabilistic information in the Markov transition probability matrix T, constructed from the Markov chain, can be directly mapped onto the Markov transition field M, which is generated according to the data length. However, the resulting Markov transition field inevitably contains a considerable amount of redundant information. To address this, it is necessary to downsample the transition field before visualization, thereby producing a two-dimensional image that retains the essential fault-related information. The specific transformation process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Through this transformation, the key temporal and frequency features embedded in one-dimensional electrical current signals are preserved. The resulting two-dimensional MTF image not only reflects the magnitude patterns and dependencies within the signal but also provides strong support for feature extraction and classification tasks in downstream deep learning models.

Compared with simpler transformation methods, MTF not only minimizes information loss and ensures the integrity of time-dependent features but also outperforms common transformations such as the Gramian Angular Field (GAF) and Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) in both efficiency and robustness. Unlike GAF, which involves trigonometric mapping that may distort amplitude information, MTF preserves the original magnitude relationships with lower computational overhead. In contrast to CWT, which requires selecting wavelet functions and incurs higher computational costs, MTF is parameter-free, simpler to implement, and retains temporal ordering without sacrificing resolution. Furthermore, its use of quantile-based discretization contributes to enhanced robustness against perturbations and noise, making it highly suitable for noisy or unstable signal environments.

Swin transformer feature extraction mechanism

The Swin Transformer adopts a hierarchical dual-attention fusion mechanism, as shown in Fig. 2. Initially, the input MTF-based time–frequency images are divided into multiple non-overlapping local windows, and feature interactions are performed independently within each window using the Window-based Multi-Head Self-Attention (W-MSA) module. This windowed processing enables precise extraction of local time–frequency features while significantly reducing computational complexity—from the quadratic complexity \({\rm O}(n^{2} )\) of conventional full-attention Transformers to a linear complexity of \({\rm O}(n)\), making it more suitable for high-resolution inputs. To capture global dependencies across windows, the Swin Transformer introduces a Shifted Window-based Multi-Head Self-Attention (SW-MSA) mechanism in the deeper layers. By cyclically shifting window positions between consecutive layers, SW-MSA effectively enables inter-window feature interactions and facilitates global contextual modeling. Each Transformer block follows a pre-norm architecture, where Layer Normalization (LN) is applied before the self-attention operations to stabilize training and improve convergence. Additionally, each block incorporates a residual connection followed by a feed-forward network composed of two multilayer perceptrons (MLPs), enabling nonlinear transformation and deep representation learning of high-level features. This architectural design allows the Swin Transformer to hierarchically and efficiently extract both local and global semantic patterns from complex time–frequency images, making it particularly well-suited for fault diagnosis tasks involving subtle and spatially distributed features in electrical current signals.

BiGRU network enhanced with global attention

To enhance the extraction of critical features from temporal current signals, this study proposes the integration of a Global Attention mechanism with a Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (BiGRU) network, enabling dynamic modeling of global contextual information and precise focus on key moments.

Basic principle of BiGRU

BiGRU (Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit) is a recurrent neural network architecture specifically designed for modeling sequential data. By leveraging both forward and backward directions, BiGRU captures dependencies from both past and future time steps, thereby enhancing the model’s capability to represent long-term temporal dependencies. This is particularly advantageous for analyzing dynamic characteristics in current signals and predicting health conditions in industrial systems.

The BiGRU structure, as illustrated in Eqs. (4)–(7), operates based on a gating mechanism that dynamically regulates the information flow. At each time step t, the model receives the input current sequence \(X\left( t \right)\), and first updates the update gate, which controls the influence of the previous hidden state \(h\left( {t - 1} \right)\) on the current state. The equation is given by:

Where Vz and Wz are weight parameters, and σ denotes the sigmoid activation function. The output \(z\left( t \right) \in \left[ {0,1} \right]\) determines the extent to which past information is retained.

Next, the model calculates the reset gate to determine how much historical information should be forgotten when incorporating new inputs:

where Vr and Wr are the corresponding weight parameters.

By combining the output of the reset gate with the current input and past state, the model performs a nonlinear transformation to generate the candidate memory content c(t):

Here, tanh is the hyperbolic tangent activation function, and \(\odot\) denotes the Hadamard product (element-wise multiplication), which enables selective forgetting and updating of past information.

Finally, the hidden state at time t is computed by blending the previous hidden state \(h(t - 1)\) with the newly computed candidate memory c(t), using the update gate z(t) as weights:

When modeling sequential current signals, BiGRU leverages its gating mechanism to effectively integrate dynamic changes that occur at different times. The forward GRU path captures cumulative feature information from historical operations, while the backward GRU path models future temporal context. This bidirectional output fusion enhances the capacity to recognize abnormal trends and health states of industrial equipment.

Moreover, this structure circumvents the gradient vanishing issues commonly faced by traditional RNNs during sequential modeling. Consequently, it significantly improves the ability to extract and represent deteriorating characteristics in industrial current signals, thereby boosting the prediction accuracy of equipment operational status and fault diagnosis.

Global attention mechanism

To further enhance the ability to model the global temporal dependencies of the sequential current signal, a Global Attention mechanism is introduced, as shown in Fig. 3. This mechanism performs dynamic attention alignment across all hidden states of the BiGRU at each time step, effectively enhancing the model’s focus on key features and events. As a result, it improves the ability to capture critical information such as equipment health anomalies and fault dynamics.

Specifically, the BiGRU network first performs bidirectional modeling on the original one-dimensional current signal, yielding a set of hidden states denoted as \(\left\{ {{\mathbf{h}}_{s} } \right\}_{s = 1}^{T}\). On this basis, the Global Attention mechanism computes the relevance between the current target hidden state \({\mathbf{h}}_{t}\) and all historical hidden states \({\mathbf{h}}_{s}\), to obtain a time-variant attention vector \(\alpha_{t}\) as:

Here, the function \({\text{score}}\left( {{\mathbf{h}}_{t} ,{\mathbf{h}}_{s} } \right)\) evaluates the similarity between hidden states and can adopt forms such as dot-product, general, or concatenation (concat), depending on the specific task. In the context of sequential current signals, this scoring function effectively quantifies the relevance between the current state and past states, thereby dynamically allocating attention resources.

Based on the attention weights above, the model further computes the global context vector \({\mathbf{c}}_{t}\) as:

This global context vector aggregates the BiGRU outputs from all time steps and adaptively strengthens the representation of the most task-relevant feature segments. Subsequently, the current hidden state \({\mathbf{h}}_{t}\) and the global context \({\mathbf{c}}_{t}\) are concatenated and passed through a nonlinear projection layer to produce the final attention-enhanced feature representation \({\mathbf{h}}_{t}\):

where \({\mathbf{W}}_{c}\) is a trainable parameter matrix, and \(\left[ { \cdot ; \cdot } \right]\) denotes the concatenation operation between vectors.

Multimodal fusion and bidirectional cross-attention mechanism

The Cross-Attention Mechanism facilitates interactive learning between features from different modalities, achieving more efficient fusion and capturing mutual information across modalities. This enhances multi-modal classification performance. In this study, a bidirectional cross-attention mechanism is employed to enable deep fusion and interaction between time–frequency image features and time-series signal features.

Assume that the features from the time–frequency domain and the sequential domain are represented as \(X_{1} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{B \times N_{1} \times C}}\) and \(X_{2} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{B \times N_{2} \times C}}\), respectively. These features are first projected linearly to obtain the Query, Key, and Value matrices:

where \(W^{Q} ,W^{K} ,W^{V} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{C \times d_{k} }}\), and \(d_{k} = \frac{C}{h}\), with h representing the number of attention heads. B denotes the batch size, Ni represents the sequence length of the i-th modality, and C is the hidden feature dimension.

Through reshaping and permutation operations, multi-head attention inputs are constructed, and attention scores from X1 to X2 and vice versa are computed as follows:

where \(\sqrt {d_{k} }\) is a scaling factor. The bidirectional cross-attention outputs are concatenated and passed through a linear projection layer, followed by a classifier for downstream fault recognition tasks. This process significantly enhances the model’s capability to represent and classify multi-modal features through effective feature interaction and deep fusion across modalities.

Module compatibility and design rationale

Radial misalignment is a common mechanical fault in PMSMs, whose electrical manifestations are often weak and easily obscured by background noise and irrelevant signal components during operation. To address this challenge, this paper proposes a Swin-BiGRU multimodal diagnostic framework that integrates information from multiple feature domains, enhancing the specificity and robustness of feature extraction through complementary collaboration between modules.

In the image branch, the Swin Transformer employs a hierarchical shifted-window attention mechanism to extract pattern features that combine local detail with global structure from the MTF-transformed time–frequency representation, enabling the effective capture of subtle disturbances occurring in the early stages of misalignment. In the time-series branch, the BiGRU, augmented with a global attention mechanism, models bidirectional temporal dependencies in the raw current sequence, highlighting periodic variations and gradual drifts associated with the fault. During the fusion stage, the bidirectional cross-attention mechanism facilitates targeted interaction between features from the two branches, reinforcing cross-domain correlations while suppressing irrelevant information and amplifying fault-relevant signals.

This integration strategy ensures that each module operates optimally within its respective feature domain while leveraging the strengths of the others, thereby substantially improving diagnostic accuracy and stability, even in high-noise industrial environments.

Experiments

Introduction to the experimental platform and dataset

The experimental setup consists of multiple components:(1) Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor (PMSM), (2) Permanent Magnet DC Generator, (3) Signal Conditioning Board, (4) Servo Motor Driver, (5) Data Acquisition Card, (6) Rigid Coupling, and (7) Nylon Sleeve. The experimental apparatus used in this study is shown in Fig. 4. A laptop is connected to the communication port of the servo driver, and control commands for the internal speed mode are issued via the host computer. These commands enable the PMSM to drive the permanent magnet DC generator at different rotational speeds. The three-phase current of the PMSM is measured using a closed-loop Hall current sensor (model: CHB-6MP, accuracy ± 0.7%, measurement range ± 19.2A) mounted on the signal Conditioning board, and the current signals are subsequently collected through the data acquisition card (model: USB-1252A, 12-bit ADC resolution, input range: ± 5 V / 0–10 V).

The experiment was conducted under a single operating condition of the PMSM at 1500 rpm, during which the three-phase current of the PMSM was collected with a sampling rate of 10,000 samples per second. As shown in Fig. 5, the motor position can be adjusted via the experimental platform to simulate three levels of radial misalignment: 0.5 mm, 1.0 mm, and 1.5 mm. For each degree of radial misalignment, data were collected four times, each lasting 25 s, resulting in a total of 119,808 sampling points. To ensure the comprehensiveness and effectiveness of training, validation, and testing, the dataset was divided into training, validation, and test sets in a 7:2:1 ratio, as detailed in Table 1. The first 1024 time-domain samples under different levels of radial misalignment are shown in Fig. 6, revealing noticeable waveform variations correlated with the severity of the misalignment.

Data preprocessing

To isolate the coupled interference components within the current signal and accurately locate the misalignment fault features—while avoiding mutual interference between the electrical and mechanical systems—the original three-phase current signals (Ia, Ib, Ic) were subjected to signal preprocessing. First, zero-mean normalization was applied to the three-phase current signals to eliminate DC bias. Then, Adaptive Variational Mode Decomposition (AVMD) was used for denoising to remove high-frequency noise. The results before and after denoising are shown in Fig. 7.

In this study, the original Ia current signal is processed using a sliding window segmentation method, followed by normalization, slicing, and label assignment to construct the dataset. Subsequently, time–frequency features are extracted using the Markov Transition Field (MTF) method, as illustrated in Fig. 8. These features serve as the input to the subsequent multimodal fusion heterogeneous model.

Model architecture selection

The model designed in this study, as illustrated in Fig. 9, consists of a dual-branch feature extraction architecture. The first branch leverages the Swin Transformer with a shifted window mechanism to hierarchically extract features from the input MTF time–frequency images, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to capture both local and global spatial relationships. The key parameters of the Swin Transformer module are configured as follows: input image size of 20 × 20, patch partition size of 2, embedding dimension of 32, Transformer depths of 2 for each stage, number of attention heads set to 4 and 8, and a window size of 5.

In the second branch, a two-layer stacked BiGRU architecture is employed to extract temporal features from the one-dimensional raw current signals. A customized global attention mechanism is further incorporated to dynamically aggregate relevant fault-related information. Each BiGRU layer contains 64 hidden units, and the outputs are fused through the global attention mechanism to emphasize critical temporal patterns.

To fully exploit the complementary strengths of the two branches, the model incorporates a customized bidirectional cross-attention mechanism, enabling deep interaction and fusion between image-based and sequential features. Fusion is applied after both branches complete feature extraction and before the classifier. The channels or hidden units from each branch are treated as a sequence of feature elements, and both outputs are rearranged into a unified representation format so that their lengths and dimensions match for alignment. Queries, Keys, and Values are parameterized separately for each direction and modality; in other words, when the image branch queries the sequence branch and when the sequence branch queries the image branch, each uses its own Q, K, and V weight matrices. This design preserves the distinct characteristics and complementary strengths of both feature types during fusion. The fused features are subsequently passed through a fully connected classification layer with DropPath regularization, and a Softmax activation function outputs the probability distribution across four classes, enabling accurate diagnosis of different levels of radial misalignment faults.

Model evaluation

During the model training process, a two-phase optimization strategy was employed. In the first 20 epochs, a learning rate of 0.0002 was used for parameter pre-training to achieve initial convergence in the feature space. In the subsequent 80 epochs, the same learning rate was maintained to further refine the network parameters. All experiments were repeated five times with different random seeds to assess stability and reproducibility of the results. As shown in Fig. 10, the convergence curves of validation loss and accuracy indicate that the model achieved 100% accuracy on the training set and 99.375% on the validation set. Additionally, the accuracy and loss trends of the test set closely followed those of the training set, suggesting that the model was well-trained without signs of overfitting.

To evaluate the model’s feature extraction capability, t-SNE visualization was performed. Figure 11 displays the original input data before model processing, while Fig. 12 presents the data after being processed by the model. As shown in Fig. 11, the original data points from different classes are heavily mixed and indistinguishable. In contrast, Fig. 12 reveals that the processed data clearly form four distinct clusters, with very few misclassifications, demonstrating the model’s strong ability to extract discriminative features.

Furthermore, a confusion matrix and an F1-score table were introduced to analyze the classification performance on the test set in more detail. The confusion matrix is shown in Fig. 13, and the F1-scores are listed in Table 2. Only the categories corresponding to radial misalignment levels 1 and 2 had accuracies slightly below 97%, while all other fault types achieved 100% classification accuracy. These results confirm the high diagnostic capability of the proposed method.

Ablation study

To investigate the contribution of each component within the proposed method to fault recognition performance, a series of ablation experiments were conducted. Each component was tested individually, with experiments labeled from A1 to A8, to evaluate their roles in the diagnosis of misalignment faults in permanent magnet synchronous motors (PMSMs). The ablation experiments are as follows: A1-removal of bidirectional cross-attention; A2-removal of global attention; A3-MTF combined with Swin Transformer; A4-time-series signal with BiGRU and global attention; A5-replacing MTF with Gramian Angular Field (GAF); A6-replacing MTF with Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT); A7-replacing MTF with Recurrence Plot (RP); and A8-the complete method proposed in this study. Figure 14 compares the fault recognition accuracy of each ablation configuration. As shown in the figure, the proposed method outperforms all other variants, demonstrating its superior capability in fault identification.

Comparative experiments on noise resistance capabilities of different models

To validate the superior performance of the proposed method in fault diagnosis, comparative experiments were conducted under two settings: with AVMD denoising and without AVMD denoising. Several baseline methods, including MTF + CNN-2D, CNN-LSTM, 1D-CNN, LSTM, and Transformer, were evaluated for comparison, as illustrated in Fig. 15.

All methods were trained directly using single-phase current signal Ia. Under denoised conditions, as shown in the comparative experiments in Fig. 15, the proposed method in this study achieved a fault recognition accuracy of 99.375%, which is significantly higher than those of MTF + CNN-2D, CNN-LSTM, 1D-CNN, LSTM, and Transformer, which achieved 87.50%, 91.88%, 88.13%, 85.94%, and 82.125%, respectively. Under non-denoised conditions, the proposed method still achieved a high fault recognition accuracy of 98.125%, which clearly outperformed the other comparison methods, whose accuracies were 75.85%, 86.375%, 75.1%, 73.125%, and 79.375%, respectively. These results demonstrate the outstanding performance of the proposed method for intelligent diagnosis of radial misalignment faults in motors, especially its ability to maintain high diagnostic accuracy and robustness in high-noise environments.

Finally, to better analyze the classification performance of the proposed method across different fault categories, we used the trained model to classify the test set data and visualized the final predicted labels versus the ground truth using a confusion matrix. In addition to the previously described confusion matrix under denoised conditions, this paper also provides the visualization results of the confusion matrix under non-denoised conditions, as shown in Fig. 16, where the horizontal axis represents the predicted labels by the model and the vertical axis represents the actual labels in the test set.

Conclusion

This study integrates the Markov Transition Field (MTF) to enhance time–frequency features, thereby improving the extraction of subtle fault information. A dual-branch parallel network, which incorporates a mechanism-constrained structured integration strategy, is constructed, where the Swin Transformer and BiGRU-GATT modules are employed to perform deep feature modeling on time–frequency images and sequential data, respectively. These multimodal features are then efficiently fused via a bidirectional cross-attention mechanism, significantly enhancing the accuracy and robustness of the diagnostic system. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method consistently achieves superior diagnostic performance under various operating conditions and outperforms traditional approaches even without prior denoising, validating its strong capability in identifying motor misalignment faults. Moreover, the method eliminates the need for additional vibration sensors, reducing hardware costs and simplifying system architecture, which enhances its engineering feasibility for motor fault diagnosis. The performance of the proposed method requires further systematic evaluation in complex industrial environments. Future work will focus on extending its diagnostic capabilities to other common mechanical faults, such as bearing wear and rotor imbalance, assessing its robustness under varying load conditions and noisy environments, and exploring domain adaptation and transfer learning techniques to enhance cross-scenario generalization. Additionally, deployment challenges such as real-time processing requirements, integration with existing monitoring systems, and hardware resource constraints will be addressed to facilitate large-scale industrial adoption. These efforts will further enhance the method’s generalizability and practical engineering value, advancing intelligent health management technologies for motors.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due [REASON WHY DATA ARE NOT PUBLIC] but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Piotrowski, J. Shaft Alignment Handbook 3rd edn. (CRC Press, 2006).

Nembhard, A. D., Sinha, J. K. & Yunusa-Kaltungo, A. Experimental observations in the shaft orbits of relatively flexible machines with different rotor related faults. Measurement 75, 320–337 (2015).

Yang, W. X. & Tavner, P. J. Empirical mode decomposition, an adaptive approach for interpreting shaft vibratory signals of large rotating machinery. J. Sound Vib. 321(3–5), 1144–1170 (2009).

Jalan, A. K. & Mohanty, A. R. Model based fault diagnosis of a rotor–bearing system for misalignment and unbalance under steady-state condition. J. Sound Vib. 327(3–5), 604–622 (2009).

Saavedra, P. N. & Ramirez, D. E. Vibration analysis of rotors for the identification of shaft misalignment Part 1: Theoretical analysis. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 218(9), 971–985. (2004).

Ramirez, D. E. Vibration analysis of rotors for the identification of shaft misalignment Part 2: experimental validation. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 218(9), 987–999 (2004).

Umbrajkaar, A. M., Krishnamoorthy, A., & Dhumale, R. B. (2020). Vibration analysis of shaft misalignment using machine learning approach under variable load conditions. Shock and Vibr. (2020).

da Silva Tuckmantel, F. W. & Cavalca, K. L. Vibration signatures of a rotorcoupling-bearing system under angular misalignment. Mech. Mach. Theory 133, 559–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2018.12.014 (2019).

Patel, T. H. & Darpe, A. K. Experimental investigations on vibration response of misaligned rotors. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 23(7), 2236–2252 (2009).

Jung, J. H. et al. Omnidirectional regeneration (ODR) of proximity sensor signals for robust diagnosis of journal bearing systems. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 90, 189–207 (2017).

Wang, J., Peng, Y. & Qiao, W. Current-aided order tracking of vibration signals for bearing fault diagnosis of direct-drive wind turbines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 63(10), 6336–6346 (2016).

Jung, J.-H., Jong-Jae, L. & Kwon, B.-H. Online Diagnosis of Induction Motors Using MCSA. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 53(6), 1842–1852 (2006).

Acosta, G., Verucchi, C. & Celso, E. A current monitoring system for diagnosing electrical failures in induction motors. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 20(4), 953–965 (2006).

Schoen, R. R., & Habetler, T. G. Effects of time-varying loads on rotor fault detection in induction machines. In Conference Record of the 1993 IEEE Industry Applications Conference Twenty-Eighth IAS Annual Meeting 324–330 10.1109/ ias.1993.298943 (1993). .

Lin, J.-L., Liu, J.-Y.-C., Li, C.-W., Tsai, L.-F. & Chung, H.-Y. Motor shaft misalignment detection using multiscale entropy with wavelet denoising. Expert Syst. Appl. 37(10), 7200–7204 (2010).

Ortiz, A., Garrido, J., Hernandez-Escobedo, Q., & Escobedo-Trujillo, B. Detection of misalignment in motor via transient current signature analysis. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Engineering Veracruz (ICEV) 1–5 10.1109/ icev.2019.8920719 (2019).

Verucchi, C., Bossio, J., Bossio, G. & Acosta, G. Misalignment detection in induction motors with flexible coupling by means of estimated torque analysis and MCSA. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 80, 570–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2016.04.035 (2016).

Yao, Y., Li, Y. & Yin, Q. A novel method based on self-sensing motor drive system for misalignment detection. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 116, 217–229 (2019).

Lee, J., Lee, Y. & Kim, N. Detection and analysis of shaft misalignment in application of production and logistics systems using motor current signature analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 217, 119463 (2023).

Shi, Y. et al. Non-intrusive load monitoring based on swin-transformer with adaptive scaling recurrence plot. Energy Rep. 8, 13109–13118 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. The research on fault diagnosis of rolling bearing based on current signal CNN-SVM. Meas. Sci. Technol. 34(12), 125021 (2023).

Verma, A. K., Sarangi, S. & Kolekar, M. Misalignment faults detection in an induction motor based on multi-scale entropy and artificial neural network. Electr. Power Components and Syst. 44(8), 916–927 (2016).

Li, C. et al. Multi-sensor fusion fault diagnosis method of wind turbine bearing based on adaptive convergent view-graph contrastive learning. Measurement 230, 114494 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Energy-propagation graph neural networks for enhanced out-of-distribution fault analysis in intelligent manufacturing. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 206, 110843 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Adaptive expert ensembles for fault diagnosis: a graph causal framework addressing distributional shifts. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 223, 110556 (2025).

Shang, Y. et al. A new cross-domain motor fault diagnosis method based on bimodal inputs. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 73, 1–10 (2024).

Chen, S. et al. Instantaneous square current signal analysis for motors using vision transformer for the fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 70(8), 7896–7906 (2023).

Dai, X. et al. Bearing fault diagnosis based on POA-VMD with GADF-Swin Transformer transfer learning network. Measurement 238, 115328 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. A gearbox fault diagnosis method based on Swin Transformer and Markov transform fields. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 136, 108134 (2025).

Wang, Z. & Oates, T. Encoding time series as images for visual inspection and classification using tiled convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the Workshops at the Twenty-Ninth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Beijing Institute of Graphic Communication-level Key Teaching Reform Project (No.22150122009). Junhao Guo provided partial funding for this study.

Funding

This work was supported by Beijing Institute of Graphic Communication-level Key Teaching Reform Project (No.22150122009). Junhao Guo provided partial funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hao Yu designed the study and wrote the manuscript text. Junhao Guo participated in part of the experimental work and provided partial funding for this study. Hao Zhang supervised the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript. Hao Yu and Hao Zhang contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, H., Guo, J. & Zhang, H. An intelligent diagnosis method for PMSM radial misalignment based on current signal and Swin-BiGRU multimodal fusion. Sci Rep 15, 33306 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17297-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17297-3