Abstract

Individuals undergo bariatric surgery to achieve significant weight loss or improvement of comorbidities. Early identification of patients at risk for suboptimal clinical response is critical to enable timely intervention. This study evaluated the performance of TWL percentiles for predicting suboptimal clinical response after one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), and sleeve gastrectomy (SG). This retrospective cohort study included 5780 individuals undergoing bariatric surgery from 2008 to 2020. Suboptimal clinical response was defined as a %TWL < 20 at the first follow-up visit occurring between 24 and 36 months after surgery. The mean age of participants was 37 years for SG and 40 years for both OAGB and RYGB, with the majority being female (75–84%). From three months post-surgery, patients with suboptimal clinical response were consistently concentrated below the 25th percentile, suggesting this threshold may serve as a general early warning sign. Six months post-surgery, the 23rd percentile for SG, 29th for RYGB, and 33rd for OAGB emerged as the key predictive thresholds. TWL percentiles offer a valuable tool for predicting suboptimal clinical response. Incorporating TWL percentile monitoring into routine postoperative care may support timely detection, enabling earlier intervention with targeted strategies for better long-term outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the global prevalence of obesity continues to rise, it is expected that by 2050, nearly one in three adults over the age of 25, approximately 1.95 billion individuals, will be living with obesity.1. Bariatric surgery is a well-established and effective long-term treatment for individuals with severe obesity2. However, nearly 20% of patients show a suboptimal clinical response3,4. Although bariatric procedures are minimally invasive with comparable risks to common operations like cholecystectomy and appendectomy5, they may lead to significant physical and mental consequences6,7,8,9. Patients undergoing bariatric surgery endure the challenges with the expectation of achieving significant weight loss or improvement of comorbidities. Therefore, ensuring that patients achieve an optimal clinical response is critical. To better define optimal response after bariatric surgery, the International Federation for Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) recently proposed a consensus definition for suboptimal clinical response: a total body weight loss (TWL) of less than 20%, or insufficient improvement in an obesity-related complication that was a key indication for surgery10.

Although adherence to dietary guidelines, regular physical activity, and regular long-term follow-ups are associated with better weight loss outcomes after surgery, some patients still experience a suboptimal clinical response11. In this context, total weight loss (TWL) percentile charts have been presented as valuable tools for bariatric surgery, offering extensive information on patients’ typical weight loss12,13,14,15. These charts enable a quick evaluation of a patient’s weight loss at each follow-up solely on the TWL from that visit and establish neutral benchmarks for determining optimal weight loss over time15. However, TWL percentiles have not yet been investigated for their ability to predict suboptimal clinical response. By visualizing patients’ TWL percentiles during early follow-ups, these charts may help us identify patients with suboptimal clinical response earlier. Tracking a patient’s position on these charts during early follow-ups may allow for earlier detection of suboptimal clinical response, enabling timely assessments, closer monitoring, and targeted interventions to improve long-term results.

This study aims to examine the relationship between TWL percentiles and suboptimal clinical response and evaluate the predictive performance of TWL percentiles for suboptimal clinical response after one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), and sleeve gastrectomy (SG), using our previously developed TWL percentile charts12,13. Determining the best percentile thresholds for predicting suboptimal clinical response at each follow-up visit and identifying the optimal time for prediction helps us to identify suboptimal clinical response earlier and intervene appropriately.

Material and methods

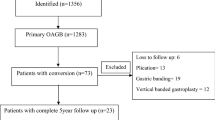

This retrospective cohort study included individuals who underwent OAGB, RYGB, or SG from 2008 to 2020. All patients aged 18–70 years old with a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 who underwent OAGB, RYGB, or SG as primary bariatric surgery by two expert surgeons and were followed up for two to three years were included in this study. Data was retrieved from the Iran National Obesity Surgery Database16. A multidisciplinary team, including general practitioners, nutritionists, psychologists, sports medicine specialists, and surgeons, followed up the patients 10 days, 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months after surgery.

The primary outcome of this study was to assess the %TWL percentile of individuals with suboptimal clinical response following bariatric surgery, using our previously presented total weight loss (TWL) percentile charts for SG13, OAGB, and RYGB12. Our secondary outcome was to present a percentile threshold that could help predict suboptimal clinical responses early after different types of surgery to enhance the timely identification of these patients.

Based on the recent IFSO consensus on definitions and clinical practice guidelines for obesity management, suboptimal clinical response is considered a total body weight loss of less than 20% or inadequate improvement in an obesity complication that was a significant indication for surgery10. In the current study, suboptimal clinical response was defined as a %TWL < 20 at the first follow-up visit occurring between 24 and 36 months after surgery. %TWL was calculated as (initial weight − post-op weight) * 100/(initial weight).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted to summarize the baseline characteristics of participants. Continuous variables were reported as means with standard deviations, and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Group comparisons were performed using chi-square tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables.

We implemented an iterative logistic regression approach to evaluate the predictive performance of TWL percentiles for suboptimal clinical response. At each post-surgical visit, we defined the exposure variable as being below a given TWL percentile threshold. In contrast, the outcome variable was suboptimal clinical response at the end of the study period. Separate logistic regression models were fitted for each percentile threshold at each time point, and the odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported to quantify the association between early weight loss and suboptimal clinical response risk.

We constructed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to assess discriminative ability and calculated the area under the curve (AUC) for each model. The AUC values and their corresponding 95% CI were used to determine the percentile-time combination with the highest predictive performance. The optimal percentile threshold at each time point was identified as yielding the highest AUC. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.2). A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of Iran University of Medical Sciences (IR.IUMS.REC.1397.464). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants signed informed consent for their data on the Iran National Obesity Surgery Database to be used in future studies.

Results

We included 5,780 individuals in our study, of whom 2,579 underwent OAGB, 1,943 RYGB, and 1,258 SG. The mean age of participants was 37 years for SG and 40 years for both OAGB and RYGB. Patients’ baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The majority were female, with the proportion of women being highest in the RYGB group (84%), followed by SG (76%) and OAGB (75%). Most patients had a baseline BMI in the 40–50 kg/m2 range, with the mean baseline BMI being highest in the OAGB group (46.9 kg/m2), followed by RYGB (43.9 kg/m2) and SG (43.8 kg/m2). Similarly, the highest prevalence of type 2 diabetes was observed in the OAGB group (23%), followed by RYGB (15%) and SG (7.4%).

The prevalence of suboptimal clinical responses was 1.83% for SG, 1.39% for RYGB, and 1.05% for OAGB. As Fig. 1 illustrates, patients with suboptimal clinical response were more concentrated below the 25th percentile from three months onward, following SG, RYGB, and OAGB. However, some cases fell at even higher percentiles early in the follow-up period, becoming fewer as time progressed to later follow-ups. In all three procedures, weight loss follows a rapid decline within the first 6–12 months, after which the rate of change stabilizes. The weight loss trajectory for patients undergoing SG appeared more gradual than those undergoing bypass procedures. Following RYGB, the weight loss trajectory followed a structured decline before stabilizing, but there was slightly more variability in weight loss trajectories for OAGB. This graphical presentation provides an overview of the relationship between TWL percentiles and suboptimal clinical response. However, determining the best percentile-time threshold for predicting suboptimal clinical response requires a more detailed statistical approach. To address this, we conducted a more specific analysis using logistic regression models and ROC curves, as described in the next section.

Predictive performance of TWL percentiles for suboptimal clinical response

To identify the most effective percentile-time thresholds for predicting suboptimal clinical response, we conducted an iterative analysis using logistic regression models, where the exposure variable was below a given TWL percentile at a specific follow-up visit and the outcome was suboptimal clinical response at the end of the study. The predictive power of these thresholds was assessed using ROC curves and AUC values, as shown in Figs. 2–4 for SG, RYGB, and OAGB, respectively.

Figure 2 presents the AUC values for different TWL percentiles at various post-surgical time points in SG patients. The predictive performance of TWL percentiles improved over time, with AUC values generally increasing from early visits to later follow-ups. At 10 days and 1 month post-surgery, AUC values were relatively low, indicating limited predictive ability. However, by 6 months, the predictive performance increased substantially, with AUC values peaking at 9 months and 1 year. This suggests that weight loss percentiles at these time points provide the most informative thresholds for suboptimal clinical response prediction. Similarly, Figs. 3 and 4 display the predictive performance of TWL percentiles for suboptimal clinical response in RYGB and OAGB patients, showing a similar pattern. As with SG, the predictive ability of early TWL percentiles for RYGB and OAGB was initially limited but improved progressively over time.

At each follow-up, following all procedures, as TWL percentiles increase, the AUC increases before reaching a peak. The decline in AUC after reaching its peak may be due to the stabilization of weight loss, reducing the variability in TWL percentiles and making them less predictive of long-term suboptimal clinical response risk. The pattern observed in the AUC curves, an initial rise as TWL percentiles increase, followed by a decline, reflects the evolving nature of weight loss trajectories after bariatric surgery. In the early postoperative period, weight loss is highly variable and not yet strongly associated with long-term outcomes, limiting predictive accuracy. As time progresses and inter-individual differences in weight loss become more pronounced, TWL percentiles gain predictive value, resulting in higher AUCs. However, once weight stabilizes and most cases of suboptimal clinical response have emerged, the added predictive value of percentiles diminishes, leading to a decline in AUC.

Optimal percentile thresholds for predicting suboptimal clinical response

To determine the most effective percentile thresholds for predicting suboptimal clinical response at each post-surgical visit, we identified the percentile with the highest predictive power at each time point using logistic regression models. Table 2 presents the optimal percentile thresholds, their associated odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and the AUC values for SG, RYGB, and OAGB patients.

At early post-surgical visits, the optimal percentile thresholds varied across procedures, with modest AUC values indicating limited predictive power. At 10 days, the 41st percentile was the best predictor for SG, the 33rd percentile for RYGB, and the 25th percentile for OAGB, though their predictive strength was relatively low, with AUC values near 0.6. By 1 month, the predictive ability improved slightly, with the 44th and 43rd percentiles emerging as the optimal threshold for SG and RYGB (AUC 0.65), while it remained weak for OAGB (AUC 0.57).

At 3 months, the optimal percentiles were 15th for SG, 56th for RYGB, and 30th for OAGB, indicating that patients with TWL below these levels were at significantly higher risk of suboptimal clinical response. The ORs for SG, RYGB, and OAGB at this time point were 5.16, 4.73, and 2.42, respectively, with AUC values ranging from 0.6 to 0.65, suggesting moderate predictive power.

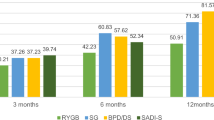

By six months post-surgery, the predictive performance of TWL percentiles improved substantially, with AUC values ranging from 0.71 to 0.79. The optimal thresholds at this time were the 23rd percentile for SG, the 29th for RYGB, and the 33rd for OAGB. SG demonstrated the strongest association with suboptimal clinical response (OR 16.08), followed by RYGB (OR 7.9) and OAGB (OR 5.85). Predictive power peaked at nine months, with AUCs of 0.89 for SG, 0.78 for RYGB, and 0.83 for OAGB. At this point, the most informative percentiles were the 23rd for SG, 16th for RYGB, and 24th for OAGB. The corresponding odds ratios were highest for SG (OR 66.41), followed by OAGB (OR 27.87) and RYGB (OR 14.88), indicating strong predictive value across all procedures.

At one-year post-surgery, the 23rd percentile remained the optimal threshold for SG, while the 20th percentile emerged for RYGB and the 18th for OAGB, with AUC values ranging from 0.85 to 0.86. The ORs remained high, with SG (OR 40.49), RYGB (OR 32.85), and OAGB (OR 37.42), indicating a strong association between 1-year weight loss percentiles and suboptimal clinical response risk.

Discussion

Individuals undergoing bariatric surgery do so with the expectation of achieving an optimal clinical response, despite the inherent challenges and potential complications. Therefore, early identification of patients at risk for suboptimal clinical response is critical to enable timely intervention and improve outcomes. This study evaluated the association between TWL percentiles and suboptimal clinical response across OAGB, RYGB, and SG. Our findings show that, from three months onward, patients with suboptimal clinical response were consistently concentrated below the 25th percentile, suggesting this threshold may serve as a general early warning sign. Six months post-surgery, the 23rd percentile for SG, 29th for RYGB, and 33rd for OAGB emerged as the most predictive thresholds. These findings highlight the potential of TWL percentiles to guide early identification and targeted intervention for patients at elevated risk.

Previous studies have underscored early postoperative weight loss as a critical factor in predicting long-term suboptimal response17. Weight loss within the first 3–6 months is significantly associated with 2-year outcomes18, with over half of the maximum TWL typically achieved within the first 6 months19. A multi-center prospective study in the Netherlands showed that patients with lower TWL at 3 months had lower weight loss trajectories over 5 years20. Additionally, patients who did not reach 66% of their predicted TWL by 6 months failed to achieve their 1-year target weight21. Our findings emphasize the importance of the 6-month follow-up as a critical time point for identifying patients at risk of suboptimal clinical response. By 6 months, the predictive performance of TWL percentiles improved substantially, with the 23rd percentile emerging as the best predictor for SG, the 29th for RYGB, and the 33rd for OAGB.

During the first few weeks after surgery, patients follow a restricted diet, with solid foods started only after one month. This dietary transition can be challenging, and food tolerance varies. By 6 months, most patients’ postoperative symptoms and food tolerances improve, allowing them to eat larger meals again22,23. Thus, adherence to dietary and behavioral recommendations becomes critical in this period. A study on food cravings after bariatric surgery reported a reduction in total food cravings, high-fat cravings, sweet cravings, carb cravings, and consumption of craved foods at 3 months, followed by an increase from 3 to 6 months24. Notably, by 6 months, consumption of high-fat foods did not differ from the pre-operation phase. Therefore, 6 months becomes an important time point for monitoring patients’ diet and providing appropriate interventions through nutritional counseling and behavioral support.

Close observation of patients falling below the percentile thresholds in early follow-ups by a multidisciplinary team may facilitate early detection and management of contributing factors. A wide range of factors may contribute to suboptimal clinical response, including psychological factors, such as depression, anxiety, alcohol and substance abuse, personality disorder, and low self-esteem11,25,26, eating behaviors including binge eating, loss of control eating, and emotional eating11,27,28, low socio-economic status, low social support, low education, physical inactivity, hormonal factors, genetic factors, anatomical and surgical factors11,26, biochemical factors such as low albumin levels and elevated HbA1c29, and older age30. Early identification and effective intervention for these risk factors are essential for enhancing long-term outcomes.

Beyond TWL percentile thresholds, the pattern of weight loss percentiles over time, whether increasing, stable, or decreasing, can provide valuable information on patients’ progress. A downward trend in an individual’s TWL percentile might indicate adverse changes in behavior, lifestyle, adherence, or overall health, potentially indicating the onset of a suboptimal clinical response. Even patients initially above threshold percentiles may be at risk if their percentile consistently declines across follow-up visits. Therefore, it is important to monitor not only TWL percentiles but also patterns of change. We recommend that clinicians pay close attention to patients with high initial percentiles who show a downward trend, as early intervention may help prevent suboptimal clinical responses.

Regular follow-up, especially within the first year after surgery, is important for timely screening of patients and long-term success31. We should educate patients before the operation about the importance of early postoperative weight loss in predicting long-term outcomes and the significance of regular follow-up with a multidisciplinary team for timely detection.

In our study, the predictive performance of TWL percentiles increased over time, with AUC values generally rising from early postoperative visits to later follow-ups. Predictive ability was limited at 10 days and 1 month, but improved significantly by 6 months, peaking at 9 months and 1 year. It’s clear that as weight loss progresses and differences between patients become more apparent, the prediction ability of TWL percentiles improves. However, at later follow-ups (1 year), most patients with suboptimal clinical response have already been identified, reducing the added value of percentiles at that stage. Therefore, 6 months appears to be an optimal time point for earlier identification of suboptimal clinical response, balancing predictive power with clinical utility.

A key strength of our study is the identification of TWL percentile thresholds for predicting suboptimal clinical response among three common bariatric procedures. While most previous studies focus on RYGB or SG, data on OAGB remain limited. Therefore, our findings on OAGB add valuable insight to the literature. However, a limitation of our study is that we were not able to account for all potential confounding variables, such as psychological factors, eating behaviors, and adherence to postoperative protocols, which influence weight loss outcomes. Future studies should incorporate these variables to validate and refine TWL percentile thresholds and present a more comprehensive model. Another limitation is that this study did not include patients without 2-year follow-up data. It is more plausible that individuals with suboptimal clinical responses who were unsatisfied with their outcomes were less likely to return for follow-up visits. This may have resulted in an underrepresentation of suboptimal clinical responses and a lower observed prevalence in our study. Future research should aim to include more diverse and representative populations with more patients experiencing suboptimal clinical response.

Conclusion

In conclusion, TWL percentiles offer a valuable tool for predicting suboptimal clinical response after bariatric surgery. Incorporating TWL percentile monitoring into routine postoperative care may support the timely detection of suboptimal clinical response, allowing for earlier intervention with personalized care strategies, ultimately ensuring better long-term outcomes. Patients with suboptimal clinical response were more frequently below the 25th percentile from three months onward, following all three procedures, indicating this threshold as a general early warning sign. The 6-month follow-up emerged as a critical time point, with the 23rd percentile threshold for SG, 29th for RYGB, and 33rd for OAGB as key predictors of suboptimal clinical response. Patients falling below these thresholds or with consistent declines in their TWL percentile should be closely monitored and considered for early intervention strategies to reduce the risk of suboptimal clinical response. Future research should validate these thresholds in larger, more diverse populations and explore targeted strategies to address modifiable risk factors.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kerr, J. A. Global, regional, and national prevalence of adult overweight and obesity, 1990–2021, with forecasts to 2050: a forecasting study for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet 405, 813–838. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(25)00355-1 (2021).

O’Brien, P. E. et al. Long-term outcomes after bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of weight loss at 10 or more years for all bariatric procedures and a single-centre review of 20-year outcomes after adjustable gastric banding. Obes. Surg. 29, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-018-3525-0 (2019).

Brissman, M., Beamish, A. J., Olbers, T. & Marcus, C. Prevalence of insufficient weight loss 5 years after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: metabolic consequences and prediction estimates: a prospective registry study. BMJ Open 11, e046407. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046407 (2021).

Cadena-Obando, D. et al. Are there really any predictive factors for a successful weight loss after bariatric surgery?. BMC Endocr. Disord. 20, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-020-0499-4 (2020).

Kovar, A. & Azagury, D. E. Bariatric surgery: Overview of procedures and outcomes. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North. Am. 54, 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2024.10.003 (2025).

Kassir, R. et al. Complications of bariatric surgery: Presentation and emergency management. Int. J. Surg. 27, 77–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.01.067 (2016).

Schulman, A. R. & Thompson, C. C. Complications of bariatric surgery: what you can expect to see in your GI practice. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 112, 1640–1655. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2017.241 (2017).

Law, S. et al. Bariatric surgery and mental health outcomes: An umbrella review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 14, 1283621. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1283621 (2023).

Francois, Z. & Rizvi, A. in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC, 2025).

Salminen, P. et al. IFSO consensus on definitions and clinical practice guidelines for obesity management—An international Delphi study. Obes. Surg. 34, 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-023-06913-8 (2024).

Kim, E. Y. Definition, mechanisms and predictors of weight loss failure after bariatric surgery. J. Metab. Bariatr. Surg. 11, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.17476/jmbs.2022.11.2.39 (2022).

Mokhber, S. et al. Weight reduction percentile charts: 2-Year follow-up results of OAGB and RYGB post bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 33, 3944–3950. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-023-06899-3 (2023).

Mokhber, S. et al. A representative percentile chart for prediction of weight loss trend after sleeve gastrectomy. Obes. Facts. 16, 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1159/000527721 (2023).

Sabench Pereferrer, F. et al. Analysis of mid-term weight loss after roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: proposed percentile charts for total weight loss percentages to be used in daily clinical practice. Cirugía Española (Engl. Edn.) 98, 72–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cireng.2020.01.014 (2020).

van de Laar, A. W. & Acherman, Y. I. Weight loss percentile charts of large representative series: A benchmark defining sufficient weight loss challenging current criteria for success of bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 24, 727–734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-013-1130-9 (2014).

Kermansaravi, M. et al. The first web-based Iranian national obesity and metabolic surgery database (INOSD). Obes. Surg. 32, 2083–2086. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-022-06014-y (2022).

Manning, S. et al. Early postoperative weight loss predicts maximal weight loss after sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg. Endosc. 29, 1484–1491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3829-7 (2015).

Manning, S. et al. Early postoperative weight loss predicts maximal weight loss after sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg. Endosc. 29, 1484–1491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3829-7 (2015).

Boustani, P., Sheidaei, A., Mokhber, S. & Pazouki, A. Assessment of weight change patterns following Roux en Y gastric bypass, one anastomosis gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy using change-point analysis. Sci. Rep. 14, 17416. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68480-x (2024).

Tettero, O. M., Monpellier, V. M., Janssen, I. M. C., Steenhuis, I. H. M. & van Stralen, M. M. Early postoperative weight loss predicts weight loss up to 5 years after roux-En-y gastric bypass, banded roux-en-y gastric bypass, and sleeve gastrectomy. Obes. Surg. 32, 2891–2902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-022-06166-x (2022).

Varban, O. A. et al. Am I on track? Evaluating patient-specific weight loss after bariatric surgery using an outcomes calculator. Obes. Surg. 31, 3210–3217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-021-05397-8 (2021).

Budny, A., Janczy, A., Szymanski, M. & Mika, A. Long-term follow-up after bariatric surgery: Key to successful outcomes in obesity management. Nutrients 16, 4399 (2024).

Lynch, A. “When the honeymoon is over, the real work begins:” Gastric bypass patients’ weight loss trajectories and dietary change experiences. Soc. Sci. Med. 151, 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.12.024 (2016).

Leahey, T. M. et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on food cravings: do food cravings and the consumption of craved foods “Normalize” after surgery?. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 8, 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2011.07.016 (2012).

Geerts, M. M. et al. Behavioral and psychological factors associated with suboptimal weight loss in post-bariatric surgery patients. Eat. Weight Disord. 26, 963–972. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00930-7 (2021).

El Ansari, W. & Elhag, W. Weight regain and insufficient weight loss after bariatric surgery: Definitions, prevalence, mechanisms, predictors, prevention and management strategies, and knowledge gaps-a scoping review. Obes. Surg. 31, 1755–1766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-05160-5 (2021).

Crozet, J., Pasquer, A., Pelascini, E. & Robert, M. Factors influencing bariatric surgery outcomes. J. Visc. Surg. 160, S7–S11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2022.12.001 (2023).

Jacobs, A. et al. Influence of mental and behavioral factors on weight loss after bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Rev. 25, e13729. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13729 (2024).

Salazar-Rios, E., Martínez Ortíz, C. A., Salazar-Rios, M. E. & Gutiérrez Rojas, C. A. Preoperative risk factors for suboptimal initial clinical response or weight regain in patients undergoing bariatric surgery, a retrospective cohort study from a high-volume center. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 410, 136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-025-03700-0 (2025).

Almasi, M. H. et al. Insufficient weight loss after bariatric surgery and its predictors: Tehran obesity treatment study (TOTS). Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 410, 114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-025-03682-z (2025).

Budny, A., Janczy, A., Szymanski, M. & Mika, A. Long-term follow-up after bariatric surgery: Key to successful outcomes in obesity management. Nutrients 16, 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16244399 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.B. and A.S. wrote the main manuscript. A.S. and S.M. designed the study. P.B. participated in data interpretation. A.S. performed data management and data analysis. S.M. and A.P. supervised the study and were involved in the recruitment and care of patients. S.M., A.S., and P.B. revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boustani, P., Sheidaei, A., Mokhber, S. et al. Early prediction of suboptimal clinical response after bariatric surgery using total weight loss percentiles. Sci Rep 15, 33173 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17320-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17320-7