Abstract

The establishment of a robust faculty performance evaluation system has become a research hotspot, as it is crucial for the continuous improvement and sustainable development of higher education institutions. However, according to available literature, the need for an easy-to-use management tool for faculty performance evaluation—one that accounts for professional tracks—within the context of China’s application-oriented universities remains unaddressed. This study presents a new evaluation framework for measuring and ranking faculty performance, tailored to the characteristics of application-oriented universities. The proposed model applies hybrid multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) techniques through a three-step approach. First, a set of measurement indicators is developed based on a comprehensive review of existing literature and faculty assessment forms used by application-oriented universities in practice. Second, in line with the classification of faculty members’ career tracks, the MACBETH (Measuring Attractiveness by a Categorical Based Evaluation Technique) method is utilized to determine the weights of evaluation criteria for each professional track. Finally, the FFR (Fuzzy Filter Ranking) approach is employed to rank faculty performance and identify outstanding faculty award winners. The applicability and utility of the proposed methodology are validated through a case study of an application-oriented university in China, which demonstrates its value as an effective evaluation tool and decision-aiding reference for faculty performance assessment. This study offers an intuitive and readily applicable solution for university stakeholders, streamlining the processes of weight assignment and faculty ranking within performance evaluations. Moreover, it can be extended to address other evaluation problems in academia, thereby contributing to the enhancement of educational quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Faculty performance evaluation is a periodic and systematic process conducted within higher education institutions to measure and assess the effectiveness of faculty members in key aspects of their work, such as teaching, scholarship, and service. A proper evaluation of faculty performance generates mutual benefits for both faculty and institutions. Research has shown that an effective performance evaluation system can positively influence faculty members’ work enthusiasm, teaching quality, and research output; enhance the overall standing of universities and colleges; and foster a culture of continuous improvement and excellence within higher education institutions1. By identifying the strengths and weaknesses of its faculty members, an institution can also allocate resources more effectively, prioritize efforts in faculty recruitment and retention, and initiate appropriate faculty development programs.

Application-oriented universities in China have a distinct role in the higher education landscape. According to China’s Ministry of Education, there were 672 application-oriented higher education institutions in 2022, accounting for 52.9% of the country’s colleges and universities. These institutions primarily focus on undergraduate education, with an emphasis on practical skills and industry-relevant knowledge to prepare students for professional careers. Their goal is to cultivate talents who not only have a solid grasp of theoretical foundations but also possess practical skills and innovative abilities, enabling them to effectively meet the demands of industry and social development. Application-oriented universities differ from research-intensive universities in terms of educational objectives, teaching models, service areas, faculty capability requirements, and student development pathways. This makes them a valuable choice for students seeking a practical, career-oriented education. However, universities and colleges are currently dominated by research-based performance evaluation systems2, which may be detrimental to creativity and innovation in teaching3,4. Such systems are also not suitable for application-oriented universities.

How to effectively address faculty performance evaluation issues in the complex context of application-oriented universities is a challenging problem. In essence, faculty performance evaluation can be regarded as a complex multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) problem, involving multiple conflicting attributes, diverse stakeholder interests, and ambiguity. MCDM methods demonstrate significant potential in faculty performance evaluation, offering an effective approach to enhance the scientific rigor, comprehensiveness, and objectivity of the evaluation process. To promote the high-quality development of higher education and enhance the scientific decision-making of policymakers, this study proposes a technical tool for faculty performance evaluation that enables the precise expression and depiction of fuzzy and uncertain preference information in the evaluation process. This study adopts a combined method to assess faculty performance within the context of China’s application-oriented higher education institutions. Specifically, the Measuring Attractiveness by a Categorical Based Evaluation Technique (MACBETH) is applied to calculate the weights of performance evaluation criteria for different faculty career tracks. Subsequently, the Fuzzy Filter Ranking (FFR) approach is utilized to rank faculty performance based on the obtained weights, as well as individual ratings or actual achievements in each criterion. In this way, this study addresses the following research questions: (1) What constitutes an effective and transparent method for evaluating faculty performance? (2) What metrics and factors should be employed, considering the characteristics of application-oriented universities? (3) How should winners of the outstanding faculty award be selected?

The selection of the integrated MACBETH-FFR approach is justified as follows.

One of the key advantages of the MACBETH approach lies in its requirement for only qualitative judgments regarding the differences in relative attractiveness values between pairs of options. It can also handle situations where providing precise values is not feasible. In contrast, many other classic weighting methods in MCDM require the elicitation of numerical values, a task acknowledged as challenging5. Furthermore, the questioning mechanism of MACBETH is straightforward and intuitive. Each query in MACBETH involves only two options, facilitating a more tractable decision-making process. The approach also features a comprehensive procedure that is lacking in other techniques. For instance, it defines indicators associated with each criterion, ensures that criteria can be compared on a common scale, and maintains consistency in the judgments provided6. Additionally, the availability of M-MACBETH software streamlines the process by enabling decision makers to obtain results automatically.

Meanwhile, the FFR method offers several distinct advantages7. First, it functions as a more flexible tool for decision makers to manage ranking tasks, enabling manual adjustments to the filter threshold. Second, it reduces the difficulty of arithmetic calculations and the complexity of the ranking process, thereby significantly simplifying the practical application of MCDM methods. Third, it mitigates the influence of extreme alternatives on ranking outcomes. Fourth, it does not require verifying the consistency of estimates, while allowing comparisons even when criteria use different measurement units8. Additionally, this method can be easily programmed into a computer application to automatically rank alternatives, making it particularly suitable for handling large-scale ranking tasks involving numerous alternatives.

The paper makes the following threefold contributions:

First, this study proposes a practical methodology that avoids complex mathematical operations. It presents a multi-criteria decision support system for evaluating faculty performance and identifying outstanding faculty members through ranking-based solutions. The integration of the MACBETH and FFR methods ensures user-friendliness for university stakeholders. Bernroider and Schmöllerl9 surveyed Austrian companies and collected 114 completed questionnaires, finding that 71.9% of the companies were aware of MCDM methods, but only 33.3% actually used them in practice. Štilić and Puška10 noted that presenting intuitive processes, visualizations, and case study-based explanations is an effective way to promote the adoption of useful MCDM methods. This paper thus contributes to bridging the identified gap between known and applied MCDM methods by exploring user-friendly decision support tools.

Second, this paper promotes interdisciplinary research in education by adopting a design science research process and demonstrates the application of MCDM methods in the educational field. Given the growing significance of decision-making in contemporary contexts, scholars have expressed a need for more MCDM techniques and approaches to be applied in higher education11. Yüksel et al.12 have also called for studies that employ MCDM techniques distinct from those used in existing research. This study integrates technical and managerial knowledge to develop a more practical and useful solution methodology. Based on existing literature, this paper represents the first application of the combined MACBETH and FFR methods in higher education.

Third, this research contributes to the literature on performance management by developing a multi-criteria evaluation index and extends educational research within the context of application-oriented universities in China. Notably, the evaluation framework incorporates criteria unique to Chinese universities (e.g., political and ideological performance). The study presents rankings for three faculty categories—teaching-focused, teaching-research balanced, and research-focused faculty—a distinction that has not been addressed in previous literature. It also serves as a reference for practitioners and software companies. With the proposed framework, each academic department can adopt simple quantitative methods to develop an evaluation system aligned with its objectives. Furthermore, human resource software companies can integrate the proposed model into the performance management module of their products to enhance functionality.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Literature review presents a literature review of performance measurement models and criteria in higher education, as well as the application of MCDM methods in faculty performance evaluation, followed by the methodological background in Methods. The proposed framework describes the proposed framework with detailed procedural steps. Case study includes a case study to implement the proposed methodology. Additionally, managerial insights are derived from the analysis and discussion of the results. Finally, Concluding remarks presents the conclusions and suggestions for future research.

Literature review

MCDM applications in higher education evaluation

MCDM techniques are primarily used to evaluate the efficiency and performance of higher education institutions and to inform decision-making processes. Systematic literature reviews on the application of MCDM techniques in higher education can be found in11,12,13,14,15,16,17.

Academic performance evaluation covers areas such as accreditation and quality assurance, institutional performance evaluation, university rankings, student performance evaluation, academic staff performance evaluation, and curriculum design and assessment. Table 1 presents representative references related to the application of MCDM in academic performance evaluation, with a focus on weight assignment and subsequent result evaluation.

Evaluation criteria are formulated based on the evaluation purpose and specific application contexts (e.g., country-specific contexts). Due to the limitations of stand-alone methods, the adoption of hybrid MCDM methods has become a trend in addressing academic performance problems. Among MCDM practices in higher education, traditional weighting and ranking methods are most prevalent, including AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process), DEA (Data Envelopment Analysis), VIKOR (VlseKriterijumska Optimizacija I Kompromisno Resenje), and TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to an Ideal Solution). In terms of illustrative examples of MCDM models, previous studies have primarily focused on research-oriented universities.

MCDM applications in faculty performance evaluation

An effective and robust faculty performance evaluation system is of importance to universities as it serves as a tool for measuring educational quality, identifying areas for improvement, and recognizing excellence. Consequently, there is a growing focus on measuring the performance of faculty members within higher education institutions. To enhance the effectiveness of evaluation, it is necessary to improve the transparency and quality of the evaluation process, increase faculty members’ recognition of and satisfaction with the results, and link evaluation results with their promotions, awards, and bonuses. Traditional performance measurement tools, such as the balanced scorecard and 360 feedback, have their limitations. MCDM methods, due to their ability to comprehensively consider multiple dimensions of factors, have received extensive attention in the field of faculty performance evaluation in recent years.

The AHP and TOPSIS methods, along with their fuzzy variants, are most widely used by scholars in constructing frameworks for faculty performance evaluation across various countries. For instance, Do33 proposed a method combining fuzzy AHP and fuzzy TOPSIS to assess and rank lecturers’ performance in the Vietnamese context. However, based on a comprehensive literature review, only 3 main criteria (i.e., teaching, research, and service) and 9 sub-criteria (e.g., quality of teaching content, success in securing external funding to support research, and service to the community) were identified for the evaluation, which is insufficient to assist evaluators in reviewing and measuring overall performance in detail. Karmaker et al.34 introduced AHP and TOPSIS methods to evaluate the performance of seven teaching staff in an academic institution in Bangladesh. The evaluation criteria included subject knowledge, communication, discipline, cooperation, and creativity, with 3 sub-criteria under each main criterion. To evaluate teacher performance in an Indonesian vocational school across 4 competencies (pedagogic, personality, social, and professional). Hafizah et al.35 designed a decision support system based on AHP and TOPSIS. Do et al.36 proposed a new dynamic fuzzy TOPSIS method and applied it to a Vietnamese university without specifying the criteria.

The AHP method has also been integrated with other MCDM methods to evaluate teaching performance. Thanassoulis et al.25 combined AHP and DEA to compare tutors’ teaching performance, illustrating the methods with a case study of a higher education institution in Greece. Daniawan37 used AHP and SAW (Simple Additive Weighting) to rank 28 lecturers at an Indonesian university based on 10 criteria of teaching quality (e.g., the updating and relevance of content to current conditions, overall assessment, and clarity in content delivery and example provision). Although both the AHP and MACBETH approaches employ pairwise comparisons, the scales used by decision makers to make judgments differ. AHP utilizes a 9-point ratio scale, whereas MACBETH adopts an ordinal scale with seven semantic values. For weight determination, AHP employs an eigenvalue method, while MACBETH relies on linear programming. In each matrix, AHP tolerates up to 10% inconsistency in judgments, whereas MACBETH does not permit any form of inconsistency6.

Many other scholars have also employed other MCDM methods with more complex mathematical models to address faculty performance evaluation problems. For instance, Radovanović et al.38 implemented a hybrid MCDM model combining the Spherical Fuzzy AHP and Grey MARCOS (Measurement of Alternatives and Ranking According to Compromise Solution) methods to evaluate university professors based on seven criteria, including teaching quality, professor availability to students, student assessment, contribution to the university, competence, and ethics and professionalism. Aazagreyir et al.39 integrated two distinct methodologies, namely Fuzzy DEMATEL (Decision Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory) and SAW, to evaluate lecturers’ performance based on the criteria of teaching, research, service, and commercialization. Watrianthos et al.40 applied the PROMETHEE (Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment Assessment) and GAIA (Geometric Analysis for Interactive Aid) methods to assess lecturer performance based on 5 metrics that focus solely on various types of publications. Complex programming models and calculation processes may make it difficult for users to understand and interpret the results, particularly for those without a strong background in technology, mathematics, or statistics. Agrell and Steuer41 proposed a combined DEA and linear programming method for the performance review of individual faculty, considering research output, teaching output, external service, internal service, and cost as criteria. The proposed multi-criteria decision support system was applied to a university department where 30 faculty members were evaluated over a 3-year period. Qian et al.42 combined the Triangular Fuzzy DEMATEL with the Backpropagation Neural Network (BP) to construct and optimize a teacher evaluation index system comprising 20 indicators (e.g., classroom teacher-student interaction, enthusiasm for one’s own work), though its applicability and accuracy were not tested.

To summarize, there is a lack of research on comprehensive faculty performance evaluation across multiple dimensions in the context of application-oriented universities. Previous studies also apply a uniform set of measurement and evaluation weights to all faculty, ignoring the need to differentiate faculty roles (e.g., research faculty, clinical faculty) to ensure fair performance comparisons. In general, faculty members affiliated with a specific academic department have their own professional tracks. If the departmental assessment policy is not suitable for faculty engaged solely in teaching activities, their performance may be underestimated. Complicated models may also impede the application of decision support tools. To address these issues, this paper proposes an effective faculty performance evaluation system that employs integrated MCDM techniques to resolve problems related to criterion selection, weight determination, and data processing. This paper uses the performance of faculty members at a public application-oriented university as an example to facilitate a better understanding of the proposed model. The model aims to provide a fair and balanced performance assessment method that reflects actual performance, offering an easy-to-use, versatile, and objective methodology for prioritizing faculty members within an academic department for excellence awards, merit pay, tenure decisions, or other recognition schemes.

Methods

MACBETH

The MACBETH method has emerged as a prominent method for generating weights in the MCDM field. It was first proposed by e Costa and Vansnick43. Due to its humanistic, interactive, and constructive nature, it has attracted the attention of scholars in the decision-making research community since its inception. Ferreira and Santos44 conducted a bibliometric literature review on the application of the MACBETH technique.

When applying the MACBETH technique, decision makers (either an individual or a group) are invited to conduct pairwise comparisons among the options, actions, or alternatives in set A (where A = {a, b, …, n} represents a finite set of n alternatives). They are asked to make semantic judgments about the difference in attractiveness between these alternatives. The pairwise comparison is carried out according to 7 pre-defined semantic categories for the difference in attractiveness shown in Table 2. For example, if alternative a is considered more attractive than alternative b, and the difference between them is considered strong, then (a, b) ∈ E4. In contrast to some other methods like direct rating or bisection, where the decision maker must deal with significant cognitive effort due to the need to compare more than two alternatives, the MACBETH process involves only two alternatives at a time.

Through linear programming, the judgments of the decision maker derived from pairwise comparisons are converted into a MACBETH scale. Let \(\:v\left(x\right)\) represent the score given to option \(\:X\), where \(\:{x}^{+}\) is at least as attractive as another option within \(\:X\) and \(\:{x}^{-}\) is at most equally as attractive as another option within \(\:X\)6. The linear programming utilized is:

Subject to \(\:v\left({x}^{-}\right)=0\) (arbitrarily assigned)

Unlike other multicriteria methods, MACBETH does not allow any inconsistency. The method features an automated process that can identify inconsistencies, even in scenarios where arrays of value judgments are incomplete. When this linear program turns out to be unfeasible, the judgments are regarded as inconsistent. Conversely, if it is feasible, there may be multiple optimal solutions. After achieving consistent value judgments, linear programming techniques can formulate cardinal value functions, which enable the calculation of trade-offs among variables44. In this case, the mean is used as the MACBETH scale. This methodology allows for the generation of numerical scores for different alternatives and the determination of numerical values for criteria weights.

MACBETH also requires a descriptor to be defined for each criterion to be evaluated. A descriptor is an ordered set of possible impact levels associated with a criterion, whose purpose is to objectively depict the influence of the alternatives with respect to that specific criterion. The higher the degree of objectivity in creating the descriptor, the less ambiguity there will be, and the easier it will be for the model to be understood and accepted. Two of the descriptor’s levels are used as reference points. One is named “Good”, which the decision maker deems unquestionably satisfactory. The other is “Neutral”, representing a level that the decision maker considers neither satisfactory nor unsatisfactory. Experiments have verified that this approach notably enhances the intelligibility of the criterion.

Fuzzy filter ranking

The FFR method is a compromising method proposed by Chang and Ku7 to determine the ranking of alternatives. The basic concept of the FFR method is to combine the filtering method, discrete fuzzy score, and Likert scale. Based on the weights obtained from the MACBETH approach and the values of each criterion, faculty performance can be ranked following the FFR steps. This method offers a simple and flexible means of producing reliable ranking results. The calculation steps of the FFR method are as follows.

Step 1: Criterion value classification and fuzzy score mapping. Based on many random ranking experiments, Chang and Ku7 have demonstrated that a 5-point Likert scale seems to be the best choice for the scale of filtering. Hence, all criterion values for the alternatives are categorized into 5 groups, which are mapped to the discrete fuzzy score range [0, 1]. Specifically: (1) a strongly significant criterion corresponds to a fuzzy score of 1; (2) a significant criterion corresponds to a fuzzy score of 0.75; (3) a normal criterion corresponds to a fuzzy score of 0.5; (4) a non-significant criterion corresponds to a fuzzy score of 0.25; and (5) a strongly non-significant criterion corresponds to a fuzzy score of 0.

Step 2: Construction of filters. Four filters are constructed as boundaries for the above five scales, forming five regions. Filter 1, denoted as \(\:{A}_{i}^{Ll}\), serves as the threshold distinguishing between strongly non-significant and non-significant criteria. Similarly defined are \(\:{A}_{i}^{Lh}\), \(\:{A}_{i}^{Ul}\), and \(\:{A}_{i}^{Uh}\), where \(\:{A}_{i}^{Ll}\) <\(\:{A}_{i}^{Lh}\) <\(\:{A}_{i}^{Ul}\)<\(\:{A}_{i}^{Uh}\). \(\:{A}_{i}^{Lh}\) acts as the boundary between non-significant and normal criteria, \(\:{A}_{i}^{Ul}\:\)separates normal and significant criteria, and \(\:{A}_{i}^{Uh}\) provides a boundary between significant and strongly significant criteria. Given the difficulty in analyzing the criterion dataset to derive the probability distribution, a simple method—outlined in Eq. (1) to (4)—is proposed by Chang and Ku7 to obtain the respective filter for the \(\:i\)th criterion. In this method, the average value of the criteria is set as the center, and then the boundaries are deployed on both sides. The lower area [\(\:{A}_{i}^{min}\), \(\:{A}_{i}^{avg}\)] is divided into three subareas using \(\:{A}_{i}^{min}-{A}_{i}^{Ll}\) =\(\:{A}_{i}^{Ll}-\) \(\:{A}_{i}^{Lh}\) and \(\:{A}_{i}^{Lh}-{A}_{i}^{avg}\) =0.5(\(\:{A}_{i}^{Ll}\) \(\:-{A}_{i}^{Lh}\)). The upper area [\(\:{A}_{i}^{avg}\), \(\:{A}_{i}^{max}\)] is divided into three subareas using \(\:{A}_{i}^{max}-\) \(\:{A}_{i}^{Uh}\) =\(\:{A}_{i}^{Uh}\) \(\:-{A}_{i}^{Ul}\) and \(\:{A}_{i}^{Ul}\:{-A}_{i}^{avg}\) =0.5(\(\:{A}_{i}^{Uh}-\) \(\:{A}_{i}^{Ul}\)). The notations\(\:\:{A}_{i}^{avg}\), \(\:{A}_{i}^{max}\), and \(\:{A}_{i}^{min}\) represent the average value, maximum value, and minimum value of the alternatives in the \(\:i\)th criterion, respectively.

Step 3: Creation of a transition decision matrix. A transition decision matrix, \(\:{m}_{ij}\) (transition value of the \(\:i\)th criterion in the \(\:j\)th alternative), is created. By quantifying each region with constant values of 1, 0.75, 0.5, 0.25, and 0, this matrix reflects the discontinuous perception of decision makers in most MCDM problems. Specifically, if the value of the \(\:i\)th criterion for the \(\:j\)th alternative is less than the first filter of the \(\:i\:\)th criterion, it is mapped to 0; if the value lies between the first and second filters, the output value of the transition decision matrix \(\:{m}_{ij}\) equals 0.25; likewise, if the value lies between the second and third filters, it is mapped to 0.5; if the value lies between the third and fourth filters, it is mapped to 0.75; finally, if the input value is above the fourth filter, the output value equals 1.

Step 4: Calculation of weight correctors. The weight correctors are calculated using Eq. (5). Since the output values of the transition decision matrix \(\:{m}_{ij}\) may not be equal across criteria, and this inequality affects the weight deviation of the criteria, a correction value is used to ensure that the sum of the output values for each criterion equals 1.

Step 5: Setting the effect factor. The effect factor \(\:{f}_{i}\) is set to 1 for benefit criteria and − 1 for cost criteria.

Step 6: Generation of the weighted and corrected decision matrix \(\:{s}_{ij}\). According to Eq. (6), it is obtained by multiplying the weight \(\:{w}_{i}\) by the effect factor \(\:{f}_{i}\), the weight corrector \(\:{w}_{i}^{m}\), and the transition decision matrix \(\:{m}_{ij}\), where \(\:{w}_{i}\) is the weight of the \(\:i\)th criterion derived from the MACBETH approach in this study, and \(\:{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{I}{w}_{i}\)=1. Finally, the ranking of the alternatives is determined according to the sum of \(\:{s}_{ij}\) for each alternative.

The proposed framework

Faculty performance evaluation is a complex and multifaceted endeavor that demands meticulous consideration of diverse factors and stakeholders. It can be viewed as a systematic process, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The inputs to the entire process are a list of faculty members and their job responsibilities, taking into account individual strengths and weaknesses. Based on these inputs, each faculty member can be classified into an applicable group (or career track). The core of this system lies in obtaining the actual performance results of each faculty member and the performance evaluation criteria. Information sources include university and college strategies (e.g., annual objectives) and administrative software (e.g., lists of publications, student satisfaction surveys, registered service hours). All faculty members within the same group are then compared and ranked. The final output is a proposal for outstanding faculty award winners from each group.

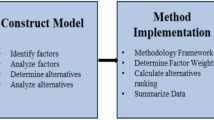

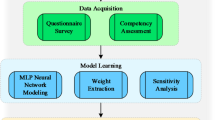

To assist decision makers in making more informed decisions during the faculty performance evaluation process, we propose a multi-phase framework that integrates multiple methods, as depicted in Fig. 2. This framework is designed around the essential elements of a comprehensive evaluation and consists of three primary steps: (1) identifying and selecting evaluation criteria based on a literature review and real-world evaluation forms collected from application-oriented universities; (2) determining the criteria weights by categories of faculty career tracks using the MACBETH approach; and (3) assessing faculty performance with the FFR method to establish the ultimate ranking. The following subsections elaborate on the implementation steps of the illustrated framework, aiming to provide a general understanding of the proposed faculty performance evaluation process.

Determination of evaluation criteria

The determination of assessment metrics is of great significance in the evaluation of faculty performance. Evaluation indicators and metrics used in faculty performance evaluations vary widely across higher education institutions. In general, the evaluation framework should encompass diverse aspects such as teaching, research, social contributions, and professional ethics. Meanwhile, it should align with the university’s strategic positioning and characteristics, ensuring coherence, scientific rigor, and comprehensiveness.

Drawing on the criteria from the prior research reviewed in Sect. 2 and referencing other faculty performance evaluation models45,46,47, we synthesized general faculty performance evaluation criteria for higher education institutions. In addition, we collected evaluation forms from 16 application-oriented universities in China, including the case-study university, to identify the most frequently used evaluation elements unique to application-oriented universities in China (e.g., political and ideological performance). Ultimately, we developed an evaluation framework consisting of 24 individual criteria grouped into 5 clusters, designated as C11, C12, …, Cmn, as shown in Table 3. Given the nature of application-oriented universities, it is not surprising that they place significant emphasis on teaching-related activities, which is reflected in the greater number of dimensions in this area.

Weight generation through MACBETH

The evaluation is extremely sensitive to the selection of weights. Prior research has demonstrated that in numerous instances, even slight fluctuations in weights can lead to different rankings of faculty performance48. Moreover, the duties and responsibilities of faculty members in different career tracks vary significantly, and thus the focus areas of evaluation must be differentiated accordingly. Therefore, different weights should be determined for each criterion based on the classification of career tracks proposed in Table 4.

When using the MACBETH approach to calculate weights, the initial step is to formulate value functions for each criterion. The decision maker provides judgments between the scale levels of each descriptor using the MACBETH semantic scale. When it is impossible to precisely determine the difference in attractiveness between scale levels, a positive category can be utilized. This characteristic of MACBETH is highly beneficial for representing the decision maker’s uncertainty when making judgments. The MACBETH questioning process should be employed to populate the judgment matrix. First, compare the most attractive level of each descriptor with the least attractive one. Subsequently, compare the second most attractive level with the least attractive level, and so forth. Next, compare the most attractive level with the remaining options in descending order of attractiveness. Then, finalize the judgments that form the diagonal boundary of the upper triangular part of the matrix. Finally, provide the remaining judgments from the upper diagonal. Through linear programming, the M-MACBETH software generates a value function that assigns a value of 100 to the “Good” level and a value of 0 to the “Neutral” level. The decision maker should review the resulting value functions to ensure they accurately reflect the relative magnitude of their judgments. To complete the weighting process across criteria, an additional alternative must be created. This alternative should include all criteria at the “Neutral” level in every descriptor. The decision-maker should then use the MACBETH semantic categories to make judgments that assess the increase in attractiveness resulting from a shift from the “Neutral” level to the “Good” level in one of the descriptors. This step enables the criteria to be ranked from the most attractive to the least attractive. Following this, compare the most attractive swing with the second most attractive swing, then the most attractive swing with the third most attractive swing, and so on. This process continues row by row until the matrix is fully completed.

Based on the judgments, the M-MACBETH software calculates the weightings for each criterion and presents the values as percentages. A set of weighting values aligns with the decision maker’s judgements. These values form ranges that serve as the thresholds (maximum and minimum values) of the fuzzy numbers. The value assigned and verified by the decision maker is adopted as the modal value. The M-MACBETH decision support system and its user guide can be accessed at https://www.m-macbeth.com.

Faculty ranking through FFR

The FFR method selects the average value as the center of the criterion and then divides the upper and lower areas into subareas. Let us take criterion C1 with five alternatives (A1, A2, …, A5) as an example. These five alternatives are then placed into a funnel-shaped model featuring four filters. The boundaries of these filters are determined according to Eq. (1) to (4). Due to the distinct thresholds of the filters, these alternatives may stop at different layers, as shown in Fig. 3. In fact, for different criteria, different funnel-shaped models can be designed to meet diverse requirements. If the probability distribution (such as the normal or uniform distribution) of the criteria is known beforehand, the decision maker can select suitable thresholds for the filters. This enables the generation of a more precise ranking of the alternatives.

Based on the position of alternatives in all criteria and corresponding criteria weights, an overall score can be obtained and alternatives are ranked accordingly.

Funnel-shaped model (reproduced from Chang and Ku7).

Case study

To demonstrate the implementation procedure of the proposed framework, a real-life case is presented to evaluate faculty performance at College X, which is part of an application-oriented university in China. The university has a long-standing history, tracing back to a school founded in 1927. As a public institution, it focuses on undergraduate education, with only a small number of graduate programs. It comprises 15 academic colleges and offers 47 undergraduate majors, catering to 18,000 full-time undergraduate students, while jointly cultivating over 130 graduate students with other research-oriented universities. The university employs 1,450 faculty members. College X, the subject of this study, is the second largest college in the university in terms of both faculty and student numbers. Currently, it has 61 full-time academic staff, approximately 80% of whom hold doctoral degrees, and offers 5 undergraduate majors with around 1,400 enrolled students. The current evaluation process at College X simply calculates a total score for each faculty member based on pre-defined criteria and corresponding scales. Outstanding faculty awards are then granted to the top 10 faculty members in the college. However, this process fails to account for the relative importance of different criteria through weight assignment and does not categorize faculty members based on their characteristics and responsibilities. Consequently, concerns regarding fairness and comparability have arisen.

For this case study, an online focus group was formed as the expert panel, consisting of three members (1 dean and 2 associate deans). The decision-making group reviewed and validated the criteria identified in Table 3 and their associated scales. Given that all key evaluation items currently used by the college were already included, no modifications were proposed. In the following subsections, the proposed set of criteria will be applied to construct a multi-criteria evaluation framework that reflects the priorities of the studied college.

Weighting the performance evaluation indicators

To determine the weights of the criteria, we first requested the decision-making group to categorize all faculty members into one of the three career tracks outlined in Table 4, considering their characteristics and responsibilities. Among the 61 faculty members at College X, 57% were identified as teaching-research balanced faculty, 33% were classified as teaching faculty, and the remaining percentage comprised research faculty. The following example demonstrates the MACBETH-based process for generating criteria weights to evaluate teaching faculty.

The first step is to rank the criteria in terms of their overall attractiveness. The 24 proposed evaluation indicators were ranked from the most important to the least important, with the aim of improving the performance of teaching faculty. After ordering all the performance evaluation criteria, the M-MACBETH weighting judgment matrix is to be filled out. The decision makers made qualitative judgments to assess the difference in attractiveness between the neutral and good levels of performance for different indicators, using the MACBETH scale. The results are presented in Figure A1 of the Supplementary Figures.

During the evaluation process, when the decision makers held divergent opinions, they engaged in constructive communication and exchanged ideas until reaching a consensus. This approach streamlined the decision-making process and facilitated agreement. The M-MACBETH software conducted an automated consistency check on the matrix. In the event of detected issues, it provided modification suggestions. Upon completion of the consistency check, the software generated an initial weighting scale proposal, which was then verified by the expert group. Decision makers could adjust the weight of a criterion within an interval generated by the software while ensuring it remained compatible with the judgment weighting matrix. The final weights are presented in Fig. 4. From a management perspective, the top three criteria for evaluating teaching faculty performance are student evaluation (C32), first-class curriculum development (C43), and teaching skill competitions (C46).

By following the aforementioned steps for the other two faculty career tracks, the criteria weights for the studied college can be derived, as shown in Table 5. Correspondingly, the top three most significant criteria in performance evaluation for research faculty are publication records and patent (C51), scientific research projects (C52), and scientific research awards (C53). In terms of teaching-research balanced faculty, the key evaluation indicators with higher weights include first-class curriculum development (C43), publication records and patent (C51), teaching achievement awards (C41), and scientific research awards (C53).

Ranking the evaluation results

In College X, the director of the Teaching and Research Office is responsible for collecting data related to the performance criteria of all faculty members and verifying the accuracy of the results. Subsequently, all faculty members are ranked in a single pool based on their total scores to determine the recipients of outstanding faculty awards. The disadvantage of the current method is that it fails to differentiate the importance of various criteria and lacks a basis for an apples-to-apples comparison in ranking.

For illustrative purposes, we take 20 teaching faculty members from the college as an example to demonstrate the proposed ranking procedure. The evaluated faculty members are denoted as F1, F2, … F20. Their performance data for 2024 were provided by the director of the Teaching and Research Office. Regarding missing data resulting from the additional criteria in the proposed framework, we requested the decision-making group to conduct an evaluation to ensure data completeness.

Based on the collected data, the boundaries were calculated in accordance with Step 2 in Subsection 3.2, and the results are presented in Table 6. It was noted that none of the faculty members had achievements in three areas in 2024, including outstanding graduation thesis awards (C48), laboratory construction (C49), and scientific research projects (C52). Consequently, the boundaries were not applicable to these three criteria and 0 was used as the result for each. Next, by following Steps 3 to 5 in Subsection 3.2, a restricted transition decision matrix \(\:{m}_{ij}\) was created, as depicted in Figure A2 of the Supplementary Figures. Using the weights obtained from the MACBETH approach, a weighted and corrected decision matrix \(\:{s}_{ij}\) was generated, along with the final ranking, in accordance with Step 6 in Fuzzy filter ranking . These are presented in Figure A3 of the Supplementary Figures. Ultimately, faculty members F11, F16, and F19 identified as the top three performers in the teaching faculty track, as shown in Fig. 5.

Similarly, teaching-research balanced faculty are denoted as F21, F22… F55, and research faculty as F56, F57… F61. By repeating the process elaborated above, the ranking results for these two faculty tracks can be obtained, as shown in Fig. 5. This ranking procedure is highly user-friendly, as it merely requires the use of pre-defined formulas, eliminating the need for manual calculations. Based on the faculty population in each track, outstanding faculty awards can be granted to the top 3 teaching faculty, top 1 research faculty, and top 6 teaching-research balanced faculty. These results align with the dean’s perceptions, thereby validating the effectiveness of the proposed model.

Sensitivity analysis

To verify the robustness of the solution, a sensitivity analysis is conducted to examine how changes in the weights of evaluation criteria affect the performance evaluation results for teaching faculty. Among all main criteria, teaching achievements (C4) have the highest relative weight, so they are likely to significantly influence the global weights of the performance criteria. For the sensitivity analysis, following the suggestion by Talib et al.49, the weight of the most important criterion (teaching achievements) is varied from 0.1 to 0.9 in increments of 0.1, with a proportionate adjustment made to the weights of all other criteria. The changes in the weights of the main criteria during the sensitivity analysis are presented in Table 7.

The changes in the weights of the main criteria result in adjustments to the global weights and rankings of the performance criteria, presented in Tables 8 and 9, respectively. As evident from Tables 8 and 9, when the weight of the main criterion “teaching achievements” ranges from 0.1 to 0.4, the sub-criterion “student evaluation” (C32) ranks first. In Scenarios 1–3, where the main criterion “teaching activities” (C3) holds the highest weight, its sub-criteria C32, C33, and C35 are among the top three. In Scenario 4, the top three performance criteria are C32, C43, and C46. However, when the weight of “teaching achievements” (C4) ranges from 0.5 to 0.9, the performance criteria C43, C46, and C41 rank 1st, 2nd, and 3rd. This shift in the order of key indicators is logical, as their parent criterion “teaching achievements” (C4) carries the highest relative weight in these scenarios.

Changes in the global weights of the criteria also lead to changes in the performance rankings of teaching faculty, as shown in Table 10. As observed, the top-ranked faculty member (F11) and the bottom three (F18, F13, and F17) remain unchanged despite weight adjustments. Generally, these faculty members are regarded as the top performer and the weakest performers, respectively, with weight changes having no impact on their rankings. In Scenarios 1–4, faculty member F16 ranks 2nd but drops to 3rd to 7th in Scenarios 5–9. This result is reasonable because this faculty member performs stronger in the criterion “teaching activities” (C3) yet weaker in the criterion “teaching achievements” (C4). Consequently, her ranking is higher in the first four scenarios, where the main criterion C3 carries the highest weight.

Discussion

The results of this case study, which applies the integrated MACBETH-FFR framework, demonstrate its effectiveness in evaluating faculty performance at application-oriented universities. The MACBETH method, with its capacity to process qualitative judgments and account for the relative importance of criteria, provides a more nuanced approach to weight determination. This is particularly crucial given that faculty members in different career tracks have distinct priorities. For instance, teaching faculty may place more emphasis on teaching-related criteria, while research faculty focus more on research outputs, which is reflected in the relatively higher weights assigned to the corresponding criteria. The FFR method, on the other hand, offers a simple yet reliable means of ranking faculty performance. Its use of discrete fuzzy scores and filters streamlines the ranking process, making it accessible even to individuals without a strong mathematical background. A significant advantage is its ability to accommodate diverse measurement units across criteria and bypass verification of the consistency of estimates. Higher education institutions can also set minimum achievement thresholds for specific criteria and adjust boundaries as needed.

Moreover, analyzing the results helps the university identify areas for improvement in faculty management, such as enhancing faculty training in research or encouraging more active participation in teaching skill competitions. If a large number of faculty members fail to meet the first filter—for example, first-class curriculum development (C43)—it indicates that the college may need to intensify efforts in this area by organizing experience-sharing sessions and knowledge transfer workshops. This not only helps faculty improve their teaching skills but also enriches teaching content, better preparing students for their professional careers.

From the decision-making group’s perspective, the integrated model provides a robust and adaptable assessment framework for faculty performance evaluation, enabling the school to navigate complexities strategically and effectively. The user-friendliness of the tools and the streamlined process enhance the practicality of this framework. The decision-making group also expressed interest in implementing the proposed methodology in the faculty performance evaluation to be conducted next year.

Concluding remarks

Faculty performance evaluation in higher education institutions is critical for ensuring teaching quality, enhancing student learning outcomes, and fostering continuous professional development. Reforming and innovating faculty performance evaluation systems in application-oriented universities is vital to the sustainable development of such institutions. This paper proposes an integrated multi-criteria evaluation framework, providing an alternative methodology for evaluating faculty performance in application-oriented universities. The proposed assessment methodology combines two components: the MACBETH method, which determines a weighting scheme based on semantic scales, and the FFR approach, which uses the weights generated by MACBETH to rank faculty members. By considering the unique characteristics of application-oriented universities and differentiating evaluation focuses according to faculty career tracks, the framework addresses the limitations of traditional evaluation methods.

The case study validates the effectiveness of the proposed framework. It provides a more scientific, comprehensive, and objective evaluation of faculty performance, enabling universities to make more informed decisions in aspects of faculty management, such as recruitment, retention, and professional development. This study contributes to the field of faculty performance evaluation in application-oriented universities by providing a practical and effective evaluation tool. Notably, the framework can be extended to research-oriented universities, thereby facilitating the high-quality development of higher education. Additionally, the methodology can be adapted to address problems such as university ranking and academic staff selection. The combination of MACBETH for weight determination and FFR for ranking offers a user-friendly and reliable solution that is easy to implement.

In terms of future research, given that faculty evaluation systems may vary across countries, further studies can be conducted to refine and supplement the initial set of indicators by incorporating insights and perspectives from a broader pool of experts. Additionally, future research could develop a mini-program that can either be embedded into a module of the university’s administrative software or operate independently to facilitate the performance evaluation process. Furthermore, researchers may explore integrating this framework with other emerging evaluation methods or technologies to enhance its accuracy and adaptability. For instance, big data analytics could be incorporated to include more diverse data sources in the evaluation process.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are partially included in this article. The complete data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Khurram, R. & Ata, M. Evaluating the effectiveness of performance appraisal systems in higher education: A Faculty-Centric study. Propel J. Appl. Manag. 4 (1), 1–25 (2024).

Cadez, S., Dimovski, V. & Zaman Groff, M. Research, teaching and performance evaluation in academia: the salience of quality. Stud. High. Educ. 42 (8), 1455–1473 (2017).

Besancenot, D., Faria, J. R. & Vranceanu, R. Why business schools do so much research: A signaling explanation. Res. Policy. 38 (7), 1093–1101 (2009).

Ter Bogt, H. J. & Scapens, R. W. Performance management in universities: effects of the transition to more quantitative measurement systems. Eur. Acc. Rev. 21 (3), 451–497 (2012).

Goodwin, P. & Wright, G. Decision Analysis for Management Judgment (Wiley, 2014).

Carnero, M. C. Developing a fuzzy TOPSIS model combining MACBETH and fuzzy Shannon entropy to select a gamification app. Mathematics 9 (9), 1034 (2021).

Chang, T. Y. & Ku, C. C. Y. Fuzzy filtering ranking method for multi-criteria decision making. Comput. Ind. Eng. 156, 107217 (2021).

Wang, X., Ferreira, F. A., Tao, M. & Chang, C. T. A hybrid AHP–FCE–WMCGP approach for internal auditor selection: A generic framework. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 24 (5), 2229–2249 (2022).

Bernroider, E. W. N. & Schmöllerl, P. A technological, organisational, and environmental analysis of decision making methodologies and satisfaction in the context of IT induced business transformations. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 224 (1), 141–153 (2013).

Štilić, A. & Puška, A. Integrating Multi-Criteria Decision-Making methods with sustainable engineering: A comprehensive review of current practices. Eng 4 (2), 1536–1549 (2023).

Badiee, A., Moshtari, M. & Berenguer, G. A systematic review of operations research and management science modeling techniques in the study of higher education institutions. Socio-Econ. Plann. Sci. 93, 101889 (2024).

Yüksel, F. Ş., Kayadelen, A. N. & Antmen, F. A systematic literature review on multi-criteria decision making in higher education. Int. J. Assess. Tools Educ. 10 (1), 12–28 (2023).

Afriadi, B. Multiple criteria decision making (MCDM) for quality education management in higher education: systematic review. Int. J. Bus. Law Educ. 3 (2), 173–180 (2022).

Johnes, J. Operational research in education. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 243 (3), 683–696 (2015).

Malik, D. A. A., Yusof, Y., Na’im, K. & Khalif, K. M. A view of MCDM application in education. In J. Phys. Conf. Series (Vol. 1988, No. 1, p. 012063). IOP Publishing. (2021), July.

Smilowitz, K. & Keppler, S. On the use of operations research and management in public education systems. Pushing Boundaries: Front. Impactful OR/OM Research, 84–105. (2020).

Sinuany-Stern, Z. Operations research and management science in higher education: an overview. Handbook of Operations Research and Management Science in Higher Education, 3–34. (2021).

Badri, M. A. & Abdulla, M. H. Awards of excellence in institutions of higher education: an AHP approach. Int. J. Educational Manage. 18 (4), 224–242 (2004).

Feng, Y. J., Lu, H. & Bi, K. An AHP/DEA method for measurement of the efficiency of R&D management activities in universities. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 11 (2), 181–191 (2004).

Bougnol, M. L. & Dulá, J. H. Validating DEA as a ranking tool: an application of DEA to assess performance in higher education. Ann. Oper. Res. 145, 339–365 (2006).

Nikoomaram, H., Mohammadi, M., Taghipourian, M. J. & Taghipourian, Y. Training performance evaluation of administration sciences instructors by fuzzy MCDM approach. Contemp. Eng. Sci. 2 (12), 559–575 (2009).

Wu, H. Y., Chen, J. K., Chen, I. S. & Zhuo, H. H. Ranking universities based on performance evaluation by a hybrid MCDM model. Measurement 45 (5), 856–880 (2012).

Kiarazm, A. & Koohkan, F. Performance evaluation in higher education institutes with the use of combinative model AHP and BSC. J. Basic Appl. Sci. Res. 3 (4), 940–944 (2013).

Aly, M. F., Attia, H. A. & Mohammed, A. M. Prioritizing faculty of engineering education performance by using AHP-TOPSIS and balanced scorecard approach. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Innovative Technol. 3 (1), 11–23 (2014).

Thanassoulis, E., Dey, P. K., Petridis, K., Goniadis, I. & Georgiou, A. C. Evaluating higher education teaching performance using combined analytic hierarchy process and data envelopment analysis. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 68 (4), 431–445 (2017).

El Gibari, S., Gómez, T. & Ruiz, F. Evaluating university performance using reference point based composite indicators. J. Informetrics. 12 (4), 1235–1250 (2018).

Blasco-Blasco, O., Liern-García, M., López-García, A. & Parada-Rico, S. E. An academic performance indicator using flexible multi-criteria methods. Mathematics 9 (19), 2396 (2021).

Ma, Z., See, K. F., Yu, M. M. & Zhao, C. Research efficiency analysis of china’s university faculty members: A modified meta-frontier DEA approach. Socio-Economic Plann. Sci. 76, 100944 (2021).

Villegas, J. G., Castañeda P, C. & Castañeda Gómez, E. Planning and performance measurement in higher education: three case studies of operational research application. Revista Facultad De Ingeniería Universidad De Antioquia. 100, 97–112 (2021).

Petrudi, S. H. H., Ghomi, H. & Mazaheriasad, M. An integrated fuzzy Delphi and best worst method (BWM) for performance measurement in higher education. Decis. Analytics J. 4, 100121 (2022).

Ayyildiz, E., Murat, M., Imamoglu, G. & Kose, Y. A novel hybrid MCDM approach to evaluate universities based on student perspective. Scientometrics 128 (1), 55–86 (2023).

Karahan, M. & Karahan, M. S. Comparative analysis of the academic performance of research universities in Türkiye using MCDM techniques. Yükseköğretim Dergisi. 15 (1), 195–208 (2025).

Do, Q. H. Evaluating lecturer performance in vietnam: an application of fuzzy AHP and fuzzy TOPSIS methods. Heliyon 10, e30772 (2024).

Karmaker, C. L. et al. A framework of faculty performance evaluation: A case study in Bangladesh. Int. J. Res. Adv. Eng. Technol. 4 (3), 18–24 (2018).

Hafizah, H., Napitupulu, D., Adiyarta, K. & Windarto, A. P. Decision support system for teacher performance assessment of SMK Nusantara 1 Ciputat based on AHP and TOPSIS. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 1255, No. 1, p. 012055). IOP Publishing. (2019), August.

Do, A. D. et al. A dynamic fuzzy multiple criteria decision-making approach for lecturer performance evaluation. J. Manage. Inform. Decis. Sci. 22 (3), 250–261 (2019).

Daniawan, B. Evaluation of lecturer teaching performance using AHP and SAW methods. bit-Tech 1 (2), 74–83 (2018).

Radovanović, M., Jovčić, S., Petrovski, A. & Cirkin, E. Evaluation of university professors using the spherical fuzzy AHP and grey MARCOS Multi-Criteria Decision-Making model: A case study. Spectr. Decis. Mak. Appl. 2 (1), 198–218 (2025).

Aazagreyir, P. et al. B. I. S. M. A. R. K. Fuzzy DEM-SAW: A novel hybridized model of fuzzy DEMATEL-SAW in lecturers’ performance evaluation based on teaching, research, service and commercialization (TRSC) criteria for promotion. Journal Theoretical Appl. Inform. Technology, 102(11). (2024).

Watrianthos, R., Ritonga, W. A., Rengganis, A., Wanto, A. & Indrawan, M. I. Implementation of PROMETHEE-GAIA Method for Lecturer Performance Evaluation. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 1933, No. 1, p. 012067). IOP Publishing. (2021), June.

Agrell, P. J. & Steuer, R. E. ACADEA—A decision support system for faculty performance reviews. J. Multi-Criteria Decis. Anal. 9 (5), 191–204 (2000).

Qian, J., Zhou, G., He, W., Cui, Y. & Deng, H. Optimization of teacher evaluation indicator system based on fuzzy-DEMATEL-BP. Heliyon, 10(13). (2024).

e Costa, C. A. B. & Vansnick, J. C. MACBETH—An interactive path towards the construction of Cardinal value functions. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 1 (4), 489–500 (1994).

Ferreira, F. A. F. & Santos, S. P. Two decades on the MACBETH approach: A bibliometric analysis. Ann. Oper. Res. 296, 901–925 (2021).

e Costa, C. A. B. & Oliveira, M. D. A multicriteria decision analysis model for faculty evaluation. Omega 40 (4), 424–436 (2012).

Purwani, F. An analytic network process method approach to design models of lecturers performance evaluation. Inter. J. Artif. Intell. Res., 6(1.2). (2024).

Retnowati, T. H., Mardapi, D., Kartowagiran, B. & Hamdi, S. A model of lecturer performance evaluation: sustainable lecturer performance mapping. Int. J. Instruction. 14 (2), 83–102 (2021).

Buyukdagli, O. & Yeralan, S. How do weights affect faculty performance evaluations? Sustain. Eng. Innov. 2 (2), 89–101 (2020).

Talib, F., Asjad, M., Attri, R., Siddiquee, A. N. & Khan, Z. A. Ranking model of total quality management enablers in healthcare establishments using the best-worst method. TQM J. 31 (5), 790–814 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.T. and Q.C. led the analysis and writing of the paper, W.Y. prepared figures and operated software , and X.W. led the project and oversaw the project progress. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Compliance with ethical standards

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tao, M., Chen, Q., Yan, W. et al. A faculty performance evaluation model based on MACBETH and fuzzy filter ranking methods. Sci Rep 15, 31566 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17537-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17537-6