Abstract

High-harmonic generation (HHG) spectroscopy enables the observation of fundamental ultrafast phenomena in nature. Recent advances in laser technology have led to the development of wavelength tunable ultrashort light sources, allowing the study of a wide variety of systems-from complex molecules to condensed matter. However, achieving broad control in key laser parameters-such as wavelength, pulse duration, and peak intensity-remains a significant challenge. We present an advanced, optical parametric chirped pulse amplifier (OPCPA) source, pumped by a single Yb:YAG laser at 50 kHz, which generates simultaneous and fully independent outputs in both the short-wave infrared (SWIR) and mid-infrared (MIR). In the SWIR, the output is optimized for two distinct wavelengths, producing pulses with a peak power of up to 17 GW centred at 2.1 µm (350 µJ, 21 fs) or 10 GW centred at 1.75 µm (420 µJ, 40 fs). In the MIR, the OPCPA delivers up to 57 µJ, with pulse durations as short as 48 fs and tunability from 2.5 to 7.6 µm. We demonstrate the system’s versatility by tailoring the laser parameters to optimize high-harmonic generation across a broad range of band gap energies in solid-state materials. In the SWIR, XUV measurements are performed at high repetition rates, overcoming the typical challenges of operating in high-vacuum environments under such conditions. In the MIR, we demonstrate that temporal pulse shaping can optimize harmonic emission while simultaneously suppressing deleterious nonlinear effects induced by the strong driving field. With its unique combination of wavelength tunability and peak power at high repetition rates, this OPCPA opens up exciting possibilities for expanding the boundaries of strong-field physics and attosecond science.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Advances in strong-field physics are often closely linked to the development of novel high-intensity laser sources1. Since the early days of attosecond science2, chirped pulse amplifiers based on Titanium-Sapphire (Ti:Sa) have been the standard laser systems used by most researchers in the field3. Commercial Ti:Sa systems are capable of delivering pulse energies exceeding 10 mJ and typically operate at repetition rates of 1 to 10 kHz4,5,6. These systems are particularly effective for pumping optical parametric amplifiers (OPAs), enabling tunable laser output across the visible to mid-infrared spectral regions7,8. However, in recent years, a new paradigm in powerful femtosecond pulse generation has emerged as an alternative to these existing platforms9. Such systems, which use diode-pumped Ytterbium pumps, offer exceptional reliability, stability, and beam quality while operating at significantly higher repetition rates—ranging from tens to hundreds of kilohertz—compared to Ti:Sa systems. Yb-laser technology, combined with the development of high-power parametric amplification stages, has driven the rapid growth of optical parametric chirped pulse amplifiers (OPCPA) in the short-wave infrared and mid-infrared ranges10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19.

The advent of next-generation laser sources has the potential to revolutionize HHG spectroscopy, enabling access to a wide range of phenomena that were previously inaccessible. The starting point of the HHG process is field induced tunneling, initiating a sub-cycle electronic wavepacket which interacts with the strong laser field20. Ionization in the presence of a strong laser field is typically characterized by the well-known Keldysh parameter \(\gamma = \sqrt{(}\frac{I_{\text {p}}}{2U_{\text {p}}})\) where \(I_{\text {p}}\) is the ionization potential of the system and \(U_{p}\) is the ponderomotive energy. Both \(I_{\text {p}}\) and \(U_{\text {p}}\) are typically expressed in units of eV, with \(U_{\text {p}} \text {[eV]}= 9.33 I_{0} [10^{14} \text {W/cm}^{2}] \cdot \lambda _{0} [\upmu \text {m}]^{2}\) where \(I_{0}\) and \(\lambda _{0}\) are the laser peak intensity and the central wavelength, respectively. Field-induced tunneling is the dominant strong-field ionization mechanism for \(\gamma <1\), which scales favorably with wavelength, i.e. \(\gamma \propto \lambda _{0}^{-1}\). Therefore, control over fundamental laser characteristics—such as wavelength and intensity—serves as a key step toward advancing HHG spectroscopy.

The development of new laser sources operating in the short-wave infrared (SWIR) and mid-infrared (MIR) ranges opens up a new regime in HHG spectroscopy, enabling the exploration of a broad range of condensed matter systems21. Since the first observation of high harmonic generation (HHG) in a bulk crystal22, there have been considerable efforts in resolving ultrafast dynamics in increasingly complex solid-state materials23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. Such systems feature band gap energies which are commonly less than 5 eV. Although the Keldysh formula presented above is typically applied to gas-phase ionization, the underlying theory is applicable to condensed matter systems as well34,35. Therefore, in order to facilitate HHG spectroscopy in materials with these relatively low band gap energies, MIR laser drivers are essential to maintain operation within the tunnel ionization regime. At these wavelengths, tunnel ionization is achieved with intensities well below \(10^{13}\) W/cm\(\phantom{0}^{2}\), and experimental specifications can be met with pulses in the microjoule range. Wavelength tunable MIR OPCPAs are well suited to meet these requirements.

Solid-state materials with larger band gap energies (\(\gtrsim\) 7 eV) can require laser intensities on the order of 10\(\phantom{0}^{13}\) W/cm\(\phantom{0}^{2}\)36 to induce tunnel ionization. At such intensities, laser-induced damage is difficult to avoid and represents a major limitation for strong-field experiments. In this regard, Yb-doped lasers offer significant advantages compared with Ti:Sa amplifiers due to their exceptional power stability and excellent beam profile quality with minimal thermal aberrations37. These properties are crucial for conducting HHG measurements at high intensities with reduced risk of laser-induced damage. We note that in this parameter range, the pulse energies and intensities delivered by Yb-pumped OPCPAs are well-suited for both gas-phase and solid-state HHG, and may open new possibilities for HHG spectroscopy of bio-molecular systems38, as well as for optimizing HHG efficiency through macroscopic scaling39.

Furthermore, in strong-field physics, low signal levels often pose a fundamental challenge. For instance, photoelectron spectroscopy typically requires the accumulation of high statistics, pushing experimental capabilities to their limits. Yb-based laser systems provide flexible platforms for working at repetition rates of tens of kilohertz and higher, while still delivering ultrafast pulses with peak intensities (usually in excess of 10\(\phantom{0}^{13}\) W/cm\(\phantom{0}^{2}\)) required for such experiments. Working at SWIR or MIR wavelengths and high laser repetition rates provides an essential advantage in a wide range of experiments, including those involving chiral molecular targets40 and photoelectron imaging of atoms41,42 and molecules43.

In this paper, we report on a dual OPCPA with simultaneous and independent outputs in the SWIR and MIR. This laser system enables scientists to explore a wide range of HHG experiments across different systems, each requiring distinct laser parameters, all of which can be conducted entirely in parallel. This capability is achieved by driving both subsystems with a single industrial-grade Yb laser source. In the remainder of this paper, we first describe the design and performance of the MIR and SWIR subsystems. We then demonstrate their application in HHG spectroscopy using representative solid-state materials with both low (ZnO) and high (quartz, MgO) band gap energies. The unique capabilities of our OPCPA address major challenges in HHG spectroscopy by enabling advanced control and optimization of the harmonic signal, laying the foundation for high-throughput attosecond solid-state studies.

OPCPA general description

The system consists of a pump laser (Amphos 3102), and two distinct SWIR and MIR OPCPA modules arranged in parallel, with the entire arrangement fitting on a 1.5 m × 4.0 m optical table. Since each OPCPA requires only part of the total pump energy, this configuration allows both OPCPAs to be operated independently and simultaneously. The pump source is a Yb-based fibre and slab chirped pulse amplifier, delivering 4 mJ pulses at a 50 kHz repetition rate (200 W total power), with a central wavelength of 1030 nm. A spectral wave shaper controls the spectral phase (up to seventh order) of the stretched seed pulses from the fibre oscillator. This pre-compensation of the spectral phase enables amplification and subsequent compression of the pump pulses to 750 fs.

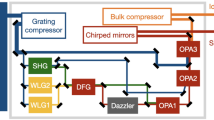

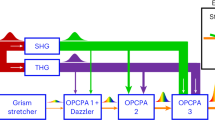

The spatial properties of the pump beam were characterized using an M\(\phantom{0}^{2}\) beam propagation analyzer (Ophir Beam Squared). The M\(\phantom{0}^{2}\) parameter was shown to be \(<1.25\) for both the x and y beam axes. The far-field focused beam profile is nearly circular with \(10 \%\) ellipticity in the beam diameter. The beam pointing direction is actively stabilized both internally and externally to the pump laser. The internal feedback loop stabilizes the beam alignment after the Yb slab amplifier and through the pulse compressor. In addition to preventing beam pointing fluctuations, such stabilization of the compressor ensures the consistency of the beam profile and pulse duration, both of which are critical for optimal OPCPA performance. Immediately after the pump laser, an active beam stabilization system, based on quadrant photodetectors (MRC systems), is implemented to stabilize the pump beam path before entering the OPCPA modules. Following a beamsplitter, 1.3 mJ is directed to pump the MIR system and 2.7 mJ to the SWIR system. This beamsplitter ratio is fixed by the specific pumping requirements for each OPCPA module. Block diagrams summarizing the architecture of each OPCPA are shown in Fig. 1. In the following sections, we describe the SWIR and MIR designs in detail.

Block diagrams of the (a) MIR, and (b) SWIR OPCPAs. The MIR module is based on filamentation and DFG/OPA processes. Broadband white light continuum is produced using a fraction of the 1030 nm pump light, producing a near-infrared seed pulse that is amplified in subsequent OPA stages pumped at 1030 nm and by its second harmonic at 515 nm. This creates a near-infrared seed pulse tunable at wavelengths between 1190 and 1600 nm. The MIR output, tunable from 2.5 to 7.6 µm, is produced in the final OPA stage via difference frequency generation between the seed and the pump, and is compressed using bulk materials. In the SWIR module, broadband passively carrier envelope phase (CEP) stable seed pulses are produced in a front end seeder box based on filamentation and DFG processes. The seed pulses are amplified in subsequent OPA stages pumped at 1030 nm, and are compressed using chirped mirrors.

MIR OPCPA

The schematic layout of the MIR OPCPA is shown in Fig. 1a. The OPCPA seed pulses are generated by focusing a portion of the pump into an undoped YAG crystal, producing a broadband supercontinuum in the SWIR. An iris is mounted on the lens to control the energy entering the YAG crystal and to ensure the generation of a single filament. The crystal is continuously translated in a cyclic periodic motion along the vertical axis at 0.2 mm/s, in order to minimize the risk of damage from accumulated thermal effects. For pumping the first two OPA stages, 16 W of the pump is frequency-doubled in an antireflection-coated BBO crystal (Type I phase matching, \(\theta =\) 23.4°, \(\phi =\) 90°), generating 0.18 mJ (9 W) at 515 nm. This pump energy is divided by a combination of a waveplate and a thin-film polarizer (TFP), with 5\(\%\) of the energy used to pump OPA1 and 95\(\%\) for pumping OPA2. In OPA1, the continuum seed is amplified in a collinear geometry in an 2.3 mm thick Type I LBO crystal, and the output is continuously tunable at wavelengths between 1190 and 1800 nm. The output power is wavelength-dependent, ranging from 20 mW at 1800 nm to 40 mW at 1190 nm.

Following OPA1, the beam is directed through an acousto-optic programmable dispersive filter (AOPDF, Dazzler, Fastlite)44,45,46,47. In the OPCPA, the Dazzler performs three essential functions: (1) chirping of the seed to ensure a good temporal overlap between the seed and pump pulses, (2) spectral selection of the highly broadband seed following the first OPA stage, and (3) pre-compensating the dispersion of the seed to control the spectral bandwidth throughout each subsequent OPA stage while enabling effective compression following the amplification stages. The Dazzler has previously been implemented in OPCPAs operating in both the SWIR48 and MIR10,11 spectral regions. In this system, the Dazzler selects the OPA2 seed wavelength from the OPA1 signal and provides spectral phase compensation within a 150 nm spectral window. The energy throughput is about 10\(\%\). The OPA2 crystal (BBO, Type I phase matching, 1 mm thick) is pumped at 515 nm in a quasi-collinear geometry, with a \(\sim\)5 degree angular separation between the pump and seed beams within the plane of incidence, allowing for effective spatial separation of pump from the seed following amplification. The power after amplification varies between 0.7 W at 1800 nm and 1.1 W at 1190 nm. In the OPA3 stage, a 1.5 mm thick Type I LiGaS\(\phantom{0}_{2}\) (LGS) crystal is pumped with 0.22 mJ (11 W) at 1030 nm in a quasi-collinear geometry. The gain factor is \(\sim\) 2.5 and the seed bandwidth is maintained throughout the tunability range. The output power in OPA3 ranges from 1.8 W at 1800 nm to 3.0 W at 1190 nm.

The final amplification stage (OPA4) is based on difference frequency generation (DFG) in a collinear geometry between the pump and seed beams. The pump energy (power) in this stage is 0.75 mJ (37 W). Here, the MIR output is produced in two separate wavelength ranges based on two different nonlinear crystals. From 2.5 to 4.0 µm (MIR1), a periodically poled Lithium Niobate (PPLN) crystal (Type 0 phase matching) generates the output, whereas a Type I Lithium Gallium Sulfide (LGS) crystal covers the 4.0 to 7.6 µm (MIR2) range. For the MIR1 option, the PPLN crystal has dimensions 1 mm (thickness) × 12 mm (width) × 3 mm (height) and uses a quasi-phase matched (QPM) fan-out design for wavelength tuning. Both sides are anti-reflection coated for the pump (1030 nm), seed (1300–1900 nm) and DFG (2200–4500 nm). For the MIR2 option, the LGS crystal (1.5 mm thickness) is cut for Type-I phase matching. Switching between the MIR1 and MIR2 outputs requires removing and replacing a few optical elements. These elements are mounted on magnetic bases, making the switch straightforward for a regular user of the system. Due to the substantially different pump and seed intensity requirements of PPLN and LGS crystals, the use of separate beam lines ensures the maximal pulse energies throughout the MIR1 and MIR2 tunability ranges.

Following OPA4, the beam passes through a bulk optical pulse compressor, consisting of Ge and/or Si plates whose thicknesses depend on the MIR wavelength selected. The plates are mounted on motorized wheels to enable hands-freealignment whenever the wavelength is changed. The compressor materials introduce positive group delay dispersion (GDD), compensating for the negative GDD of the MIR beam. The compressor throughput efficiency varies between 70 and 85\(\%\), depending on the quantity and type of plates required for a particular wavelength.

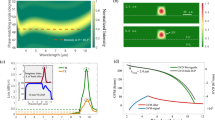

Table 1 summarizes the MIR energy and pulse duration performance of the OPCPA. The pulse durations were measured using a SH-FROG setup (Frozzer, Fastlite). For all wavelengths, the measured FWHM pulse duration is within 15\(\%\) of the Fourier transform limited (FTL) value based on the recorded MIR spectra (Fig. 2). All pulse durations correspond to \(\sim\) 5 optical cycles, highlighting the exceptionally large bandwidth obtained in the OPCPA over the entire tuning range. The MIR spectra (Fig. 2) were measured directly using a Fourier Transform interferometer (FTIRzz, Fastlite). The typical output power stability of the system is 1.7\(\%\) RMS, throughout the tuning range, over 12 h of continuous run time.

In the MIR1 range (2.5 - 4.0 μm), the maximum compressed pulse energy reaches 57 µJ at a central wavelength of 2.5 µm, corresponding to a pump-to-MIR energy conversion efficiency of 4.4\(\%\). The shortest FWHM pulse duration in the MIR1 range is 48 fs, achieved at a central wavelength of 2.9 µm. Fig. 3a shows the reconstructed SH-FROG trace at 2.9 µm, while the retrieved spectrum and spectral phase are presented in Fig. 3b. The SHG-FROG signals were measured using an extended InGaAs spectrometer (NIRQuest, OceanOptics). In the MIR2 range (4.0 - 7.6 μm), the maximum pulse energy after compression reaches 22 µJ (1.1 W) at 4.0 µm central wavelength, corresponding to a pump-to-MIR energy conversion efficiency of 1.7\(\%\). The pump-to-MIR photon conversion efficiency is nearly constant (averaging 6\(\%\)) throughout the MIR2 range. The system can be continuously tuned up to 7.6 µm, as shown in Fig. 2, with a pulse energy of 10 µJ before compression. Fig. 3c presents the temporal autocorrelation trace for 5.9 µm, 14 µJ pulses. For temporal measurements in the MIR2 range (> 4.0 µm), the spectrometer was replaced with an InAsSb photodetector (PDA10PT-EC, Thorlabs) and the SH-FROG was operated as an autocorrelator. At the 5.9 µm central wavelength, the retrieved pulse duration is 99 fs FWHM.

Spectral tunability of the MIR OPCPA. The central wavelength can be tuned from 2.5 to 7.6 µm. Normalized sample spectra are shown for central wavelengths of 2.5 µm, 3.0 µm, 3.3 µm, 3.8 µm (MIR1 range, with DFG in the PPLN crystal), and 4.0 µm, 4.8 µm, 5.6 µm, and 7.6 µm (MIR2 range, DFG in LGS). While the OPCPA enclosure was purged with nitrogen during the measurements, the MIR spectrometer remained outside the purged environment. Consequently, the recorded spectra exhibit some modulation, predominantly arising from water vapor absorption.

Spectral and temporal characterization of the MIR pulses. (a) Reconstructed SH-FROG trace for 2.9 µm, 47 µJ pulses with a retrieved 46 fs FWHM pulse duration. (b) Retrieved spectrum and phase for the SH-FROG trace in (a). (c) Intensity autocorrelation measurement for 5.9 µm, 14 µJ pulses with a retrieved 99 fs FWHM duration.

The selection of MIR crystals is a critical factor in the system’s performance. The high conversion efficiency achieved throughout the MIR2 range highlights the main advantage of using LGS crystals in high repetition rate MIR OPCPAs. We note that MIR crystals such as AgGaS\(\phantom{0}_{2}\), AgGaSe\(\phantom{0}_{2}\), and GaSe are commonly used in OPA/DFG cascades with low repetition rate (\(< 10\) kHz), 800-nm Ti:Sapphire pump sources7,8. However, all three crystals have low band gap energies that preclude pumping with high power 1-µm systems without a high risk of damage13,49. For example, AgGaS\(\phantom{0}_{2}\), commonly used for Ti:Sa-pumped OPAs, is known to degrade rapidly when pumped at high repetition rates19. Other MIR crystals, such as ZGP have high nonlinearities, but their low band gap energies (2.2 eV for ZGP) make pumping with 1-µm lasers problematic due to limitations from multiphoton absorption50. LGS, on the other hand, overcomes these challenges primarily due to its larger band gap (4.15 eV), providing a highly effective solution for tunable DFG at wavelengths > 4 µm with high repetition rate 1-µm pumps51,52. In the MIR1 range, we chose PPLN due to its high efficiency and wavelength tunability. We have previously shown that parasitic heating effects such as green-induced infrared absorption and photothermal blooming are manageable with PPLN at similar pump intensities and repetition rates10,53. Moreover, the combination of PPLN and LGS provides spectral overlap near 4 µm, ensuring continuous wavelength tunability without spectral gaps across the system’s operating range.

Fig. 4 shows the near- and far-field beam profiles for wavelengths in the MIR1 (2.9 µm) and MIR2 (5.9 µm) ranges. Notably, the beam profiles remain quite consistent throughout the entire OPCPA tuning range. These measurements demonstrate the high beam profile quality and excellent focusability for demanding strong-field experiments.

Beam profiles of the MIR beams. (a) Near-field, and (b) far-field profiles at \(\lambda =\) 2.9 µm, showing typical performance for the MIR1 beam line (based on PPLN crystal). (c, d) Corresponding near and far-field profiles for the MIR2 beam line (based on LGS crystal) at \(\lambda =\) 5.9 µm. The images were recorded using an IR camera (Pyroview 640-M, DIAS), operating over a 2–14 µm spectral range. The near-field profiles were measured at the compressor output, using the reflection from a CaF\(\phantom{0}_{2}\) wedge to sample the beam. The fitted beam diameters (1/e\(\phantom{0}^{2}\) intensity width) in (a) and (c) are 9.7 mm and 8.8 mm, respectively. These images show round, unstructured beams with no evidence of thermal blooming or other deleterious thermal-based effects across the MIR tuning range. The far-field profiles were measured at the focus of an f = 30 cm CaF\(\phantom{0}_{2}\) lens, and the fitted beam ellipticities in (b) and (d) are 0.13 and 0.08, respectively.

SWIR OPCPA

The schematic layout of the SWIR OPCPA appears in Fig. 1b. The core element of the SWIR OPCPA is the seeder box, based on a compact architecture thatprovides a stable front end for the subsequent amplification stages. A small portion of the pump (2.6 W) is directed through a spatial filter consisting of a 1:1 telescope with a 160 µm diameter Titanium pinhole in the focal plane of the first lens. The spatial filter stabilizes the filamentation process by suppressing pulse-to-pulse wavefront fluctuations in the pump beam. This reduces propagation-induced phase shifts in the white-light continuum and ensures power and carrier-envelope phase (CEP) stability in the seeder box output54. The throughput of the spatial filter is > 85\(\%\), which provides a 2.1 W pump beam for the seeder box. The box includes a patented inline DFG architecture and an OPA stage48. A beamsplitter divides the beam between the inline DFG seed path (20\(\%\)) and the pump beam of the OPA1 stage (80\(\%\)). For the seed, a calcite plate produces two orthogonally polarized pulses with a fixed delay, which are focused into a YAG crystal. The energy of the first pulse is below the filamentation threshold, while the second pulse produces a white-light supercontinuum through filamentation. The crystal is continuously translated in a cyclic periodic motion along the vertical axis at 0.2 mm/s, which is essential for reducing the risk of damage from accumulated thermal effects. A second calcite plate temporally recombines the visible supercontinuum and the low-energy pump beam replica. Both pulses are focused into a 1 mm thick Type I BBO crystal, where a CEP-stable pulse is generated through a DFG process55.

The DFG pulse covers the spectral range from 1500 to 2600 nm. In OPA1, the DFG seed and the pump beams are combined in a fan-out PPLN crystal, type 0 phase matching. Owing to the large bandwidth of the DFG seed and a range of poling periods in the fan-out PPLN crystal, the OPCPA is continuously tunable over the entire spectral range of the DFG. The seed can be tuned spectrally by tilting the DFG crystal phase matching angle to shift the central wavelength. However, we optimized its performance at two central wavelengths according to our experimental requirements —1.75 µm and 2.1 µm. For a seed centered at 2.1 µm, the seeder box output is 100 mW (2 µJ), whereas for 1.75 µm it is 30 mW (0.6 µJ). The highest output power in OPA1 is achieved at 2.1 µm, due to the operation near the degeneracy point where the nonlinear gain coefficient is maximal.

After leaving the seeder box, the beam undergoes spectral amplitude and phase shaping in a Dazzler. It then passes through a bulk silicon window to adjust the pulse dispersion, ensuring matched pump and seed pulse durations in the OPA3 and OPA4 stages for the optimal extraction efficiency. In the OPA2 stage, the seed is amplified in a second PPLN fan-out crystal (identical to OPA1) in a quasi-collinear geometry, pumped with 5.5 W of pump. The output of this stage is 500 mW at 2.1 µm, and 450 mW at 1.75 µm. The OPA3 stage employs a bulk 5\(\%\) MgO-doped Type I Lithium Niobate crystal operating in a non-collinear geometry. Since this configuration requires the seed polarization to be perpendicular to that of the pump (which is horizontal everywhere in the system), the seed is passed through a periscope that raises the beam height and rotates its polarization from horizontal to vertical. With 38 W of pump, the seed in OPA3 is amplified to 5.0 W at 2.1 µm and 5.8 W at 1.75 µm. In the final stage (OPA4), the pump beam is first spatially reshaped by a diffractive optical element (DOE, Holo/Or), resulting in a more uniform, flat-top beam profile that enhances the extraction efficiency56. Similar to OPA3, the OPA4 stage employs a bulk 5\(\%\) MgO doped Type I Lithium Niobate crystal operating in a non-collinear geometry. Following the DOE, OPA4 is pumped with 88 W and produces an uncompressed output power of 20.5 W at 2.1 µm, and 22.5 W at 1.75 µm. In OPA stages 2, 3, and 4, the non-collinear angle between the pump and the seed is \(\sim\) 3 degrees in the horizontal plane. Each of these crystals is housed in a temperature-stabilized oven with \(\pm 0.1^\circ\)C stability.

Following OPA4, the amplified beam is directed toward a chirped mirror compressor setup. The two SWIR wavelengths employ independent compressors, following which, both outputs are returned to a common beam path out of the OPCPA enclosure. At 2.1 µm, the beam makes 8 reflections in the single-pass chirped mirror compressor, with a GDD of – 250 fs\(\phantom{0}^{2}\) per reflection (UltraFast Innovations, PC1741). The compressed power is 17 W, or 350 \(\upmu\)J/pulse at 50 kHz, with 83\(\%\) compressor efficiency. At 1.75 \(\upmu\)m, the beam makes 16 reflections in a double-pass geometry, with a GDD of – 250 fs\(\phantom{0}^{2}\) per reflection (UltraFast Innovations, PC1710). The compressed power is 20.5 W at 50 kHz or 410 \(\upmu\)J/pulse, with 91\(\%\) compressor efficiency. Typical power stability for both SWIR wavelengths is 1.5\(\%\) RMS over 12 hours of continuous run time.

Fig. 5 presents the spectral and temporal characterization of the pulses. Spectral measurements were performed using a Mozza IR spectrometer (Fastlite), which captures spectra over the 1–5 \(\upmu\)m range. Pulse characterization was performed using a self-referenced spectral interferometry (SRSI) device (Wizzler, Fastlite), operated in conjunction with the Mozza spectrometer. The Wizzler generates a reference pulse with a flat spectral phase via cross-polarized wave generation (XPW)57. In order to optimize the compression, a feedback loop between the Wizzler/Mozza and the Dazzler is typically employed to fine-tune the spectral phase profile on the Dazzler. At 1.75 \(\upmu\)m, the retrieved pulse duration is 45 fs (FWHM), while at 2.1 \(\upmu\)m, it is 19.8 fs (FWHM), corresponding to approximately three optical cycles. For both SWIR wavelengths, the compressed pulse durations are within 4\(\%\) of the FTL. Beam profiles in the near-field and far-field are shown in Fig. 6. The fitted near-field beam diameters at the output along the x and y-axes are 4.8 and 4.1 mm (1/e\(\phantom{0}^{2}\) intensity), correspondingly. The far-field beam profile, measured at the focus of an f =20 cm CaF\(\phantom{0}_{2}\) lens, is nearly circular with \(\sim\)10\(\%\) ellipticity.

Spectral and temporal characterization of the SWIR pulses. (a) reconstructed spectral intensity and phase, and (b) temporal intensity for the 1.75 µm SWIR output. (c, d) corresponding reconstructions for the 2.1 µm SWIR output. The retrieved FWHM pulse durations are 45 fs at 1.75 µm, and 19.8 fs at 2.1 µm.. At both SWIR wavelengths, the compressed pulse durations are within 4\(\%\) of their FTL.

(a) Near-field, and (b) far-field beam profiles for the 2.1 µm SWIR pulses. The beams were measured using a Silicon CMOS camera (Basler Ace acA4024-29um). The far-field beam profile, measured at the focus of an f = 20 cm CaF\(\phantom{0}_{2}\) lens, is nearly circular with \(\sim\)10\(\%\) ellipticity. Both the near-field and far-field beam profiles were acquired in two-photon mode; the actual intensity distribution was retrieved by taking the square root of the recorded images.

The SWIR OPCPA also supports variable repetition rates , which are crucial for solid-state HHG experiments. For free standing crystals held under high vacuum—a common configuration for HHG in the XUV—residual heating and thermal induced stress on the sample can present a major experimental challenge. At laser intensities on the order of \(10^{13}\) W/cm\(\phantom{0}^{2}\), the sample may not withstand the combined effects of high pulse energy and high laser repetition rate. In such cases, the ability to reduce the repetition rate becomes essential. We control the OPCPA repetition rate by reducing the 50 kHz pump trigger, through frequency division, to trigger the Dazzler at a lower frequency. The Dazzler then functions as a pulse picker by diffracting seed pulses at the reduced trigger rate, which are amplified in subsequent OPA stages. We observe that the output pulse energy exhibits minimal dependence on the repetition rate. This allows for flexible control of the repetition rate during experiments without altering the intensity, pulse duration, or other factors that influence strong-field interactions.

HHG results and discussion

Shaping of HHG spectra using dispersion compensated MIR pulses

One of the most significant breakthroughs in attosecond science is the generation of HHG in solid-state media. This advancement, combined with the development of state-of-the-art laser systems described in this work, opens new possibilities for applying HHG spectroscopy to the study of a wide range of sub-cycle phenomena in condensed matter systems. The strong-field interaction in solids induces rich sub-cycle dynamics while imposing significant challenges. The strong laser field can drive additional nonlinear processes such as Kerr-type self focusing, self-phase modulation (SPM), and continuum generation. Such processes can strongly influence the characteristics of the laser field and, consequently, reshape the HHG spectrum.

The impact of nonlinear effects on the HHG process has been observed under various conditions. In bulk MgO crystals driven by near-infrared light, SPM has been shown to reshape the HHG spectrum58,59, prompting efforts to compensate for these distortions using tailored pulse shaping techniques60. In bulk ZnO crystals driven by MIR lasers, HHG peaks are spectrally broadened compared to those from ZnO nanofilms, where propagation effects are suppressed and bulk nonlinearities are absent61. Additionally, a white-light continuum emitted from bulk ZnO introduces a broadband spectral background that overlaps with the HHG spectrum, but is absent in ZnO nanofilms. Removing this unwanted background is challenging. Many commercial UV-VIS spectrometers that are commonly used for measuring HHG driven by MIR lasers are based on the Czerny-Turner configuration with a 1D silicon array detector. Such designs are often susceptible to stray light contamination due to the absence of an exit slit62. As a result, white-light continua co-propagating with the HHG are scattered inside the spectrometer, producing a uniform background across the entire detector that is not easily spectrally filtered. To date, effective strategies for optimizing HHG emission and detection in the presence of competing nonlinear effects have yet to be adequately explored.

In order to study the role of nonlinear processes that accompany the HHG mechanism, we performed a systematic study of the strong-field interaction in bulk ZnO crystals. Specifically, we resolved the HHG spectrum as we modify the pulse duration. MIR pulses centered at 3.8 \(\upmu\)m were focused into a 300 \(\upmu\)m thick c-cut ZnO crystal using a f = 15 cm uncoated CaF\(\phantom{0}_{2}\) lens. In all measurements, the laser polarization lies in the (11\(\bar{2}\)0) plane of the crystal and is parallel to the optical axis. This orientation leads to the emission of both even and odd high harmonics63. Following the crystal, the MIR light was filtered out using fused silica plates, which transmit the HHG signals with minimal losses. HHG signals were then collimated and focused by a pair of CaF\(\phantom{0}_{2}\) lenses into a fibre-coupled spectrometer (Avantes ULS2048). The pulse duration was controlled by varying the second order group delay dispersion (GDD) parameter on the Dazzler. This manipulation indirectly shapes the spectrum and spectral phases of the output pulses by modifying the temporal duration of the chirped seed pulses in the MIR OPCPA process. The output bandwidth is therefore controllable by pre-chirping the seed in the Dazzler, before the final three OPA stages. In the experiment, we thereby adjusted the FWHM pulse duration from 60 fs to 160 fs while keeping the pulse energy approximately constant at 3 \(\upmu\)J. For a FWHM focal spot diameter of 65 \(\upmu\)m, measured using the knife-edge method, this corresponds to peak intensities varying between \(6 \times 10^{11}\) W/cm\(\phantom{0}^{2}\) and \(1.5 \times 10^{12}\) W/cm\(\phantom{0}^{2}\). The pulse durations were measured using an SHG scanning autocorrelator, both at the output of the OPCPA and after propagation through the ZnO crystal. The corresponding MIR spectra were also recorded both at the laser output and after the ZnO crystal using a Fourier Transform spectrometer (Fastlite FTIRzz).

First, we examine the effect of propagation on the properties of the strong laser field. As the magnitude of the GDD on the Dazzler increases (i.e. becomes more negative), the pulse duration is shortened, and the peak intensity increases. We observe that for the same input pulse energy, shorter and more intense pulses experience greater spectral modulation due to propagation through the sample. This is illustrated in Fig. 7, which compares MIR spectra measured at the laser output and after the ZnO crystal for two different values of the applied GDD. In the top figure, the Dazzler GDD is – 2.3 \(\times 10^{4}\) fs\(\phantom{0}^{2}\), which produces near-FTL pulses for the laser output at 3.8 \(\upmu\)m (\(\sim 2650\) cm\(\phantom{0}^{-1}\)) central wavelength, with a FHWM pulse duration of 60 fs. Following the interaction in the ZnO crystal, the center of the MIR spectrum appears highly depleted (dashed blue curve), which results in an effective blue-shifting of the laser’s peak frequency by about 100 cm\(\phantom{0}^{-1}\). The origin of this effect is likely due to space-time focusing and self-steepening64,65 of the MIR driving pulse within the bulk laser crystal. The intense laser generates a plasma (clearly visible by eye within the laser focus), which temporally reshapes the pulse and creates a steep intensity gradient on the trailing edge of the pulse. These phenomena lead to the temporal modulation of the intensity-dependent refractive index, and thereby the spectral phase of the pulse, leading to a blue shift in its spectrum. The plasma itself can provide an additional source for the blue shift66. In contrast, in the bottom figure, the Dazzler GDD is – 1.9 \(\times 10^{4}\) fs\(\phantom{0}^{2}\), generating a narrower input laser bandwidth and longer pulse duration (160 fs). However, due to the lower peak intensity, the reshaping of the MIR is less pronounced. This points to a significantly reduced role of nonlinear processes occurring in parallel with HHG.

Such modulation of the pulse duration-and the resulting suppression of competing nonlinearities-has a pronounced effect on the HHG spectrum. Fig. 8 presents the dispersion-dependent HHG spectra, focusing on two harmonic peaks. Harmonic 9 is emitted at an energy below the band gap energy of ZnO, and is dominated by intraband emission, whereas harmonic 13 is emitted above the band gap energy, dominated by interband recombination23. We vary the magnitude of the GDD on the Dazzler between – 1.9 \(\times 10^{4}\) fs\(\phantom{0}^{2}\) and – 2.45 \(\times 10^{4}\) fs\(\phantom{0}^{2}\), covering pulse durations from 160 to 60 fs. As the magnitude of the GDD on the Dazzler increases (i.e. becomes more negative), the peak intensity increases,and a continuous blue shift of the HHG peaks toward higher energies is observed. Over this range of applied GDD, the shift in HHG peak energy is 0.10 eV for H9 and 0.15 eV for H13. These shifts are significant when compared to the laser output frequency of 0.33 eV (3.8 \(\upmu\)m centre wavelength).

Modulated MIR spectra following HHG in the ZnO crystal. Top figure: spectra at the output of the laser (green solid curve) and at the output of the ZnO crystal (blue dashed curve) for a GDD of – 2.3 \(\times 10^{4}\) fs\(\phantom{0}^{2}\) applied to the Dazzler. This optimal value of dispersion produces 60 fs near-transform limited pulses. Bottom figure: corresponding spectra for GDD of – 1.9 \(\times 10^{4}\) fs\(\phantom{0}^{2}\) applied to the Dazzler (160 fs pulses). For the same input pulse energy, shorter and more intense pulses experience greater spectral modulation due to propagation through the sample.

Pulse duration dependent spectral shifts of HHG peaks. A bulk ZnO single crystal (c-cut, 300 um thickness) was driven by MIR pulses with a central wavelength of 3.8 \(\upmu\)m, and HHG spectra were recorded for varying second order spectral phases applied to the Dazzler. In the figure we highlight the 9th and 13th harmonic order peaks. The pulse duration is lengthened from 60 fs to 160 fs as the dispersion is increased from – 2.4 \(\times 10^{4}\) fs\(\phantom{0}^{2}\) to – 1.9 \(\times 10^{4}\) fs\(\phantom{0}^{2}\). The optimal, near-FTL pulses are produced with a GDD near – 2.3 \(\times 10^{4}\) fs\(\phantom{0}^{2}\). As the magnitude of the dispersion increases, the temporal duration of the pulse is lengthened and the spectral peaks shift toward higher energies.

Further insight into the origin of the HHG shifts is gained by linking them with the spectral content of the MIR pulses after propagation through the bulk ZnO sample. For each value of the Dazzler GDD, we recorded the MIR spectrum following the ZnO crystal, as shown in the example of Fig. 7, and extracted its peak frequency. We then calculate an “estimated” HHG peak energy value by multiplying the MIR peak frequency by the harmonic number. The findings are summarized in Fig. 9. Here we compare, for each Dazzler GDD value, the measured peak HHG energies of harmonics 9 and 13, with the “estimated” peak energies for each GDD value. As can be clearly observed, both follow the same trend, with HHG peaks shifting to higher energies as a result of the propagation-dependent effective blue shift of the MIR laser frequency. For higher magnitude GDD, the agreement between the “estimated” and experimentally observed HHG peak energies is excellent, i.e. the harmonic peaks are emitted almost precisely at integer multiples of the MIR peak frequency. For lower-magnitude GDD, the situation changes subtly. The Dazzler applies a net positive GDD to the OPCPA seed (relative to the FTL value), resulting in a negatively chirped MIR pulse after the DFG stage. Consequently, the bluer frequency components arrive on the leading edge of the MIR driving pulse, potentially causing HHG peaks to appear at somewhat higher energies than the estimated values.

In Fig. 10, we show how the modulation of the pulse duration affects the complete HHG spectrum. We compare the measured spectra for two applied Dazzler GDD values. In the near-FTL case (GDD of – 2.3 \(\times 10^{4}\) fs\(\phantom{0}^{2}\)), the broader MIR bandwidth results in wider harmonic peaks and reduced peak visibility due to spectral overlap between adjacent peaks. These observations highlight significant limitations for HHG spectroscopy, particularly in above-band gap emission where both even and odd harmonics are present and signal levels are weak. Additionally, HHG spectra generated by shorter laser pulses and higher peak intensities are accompanied by a more pronounced noise background from competing nonlinear effects, ultimately degrading the signal-to-noise ratio. In contrast, for spectrally shaped pulses with an applied GDD of –1–9 \(\times 10^{4}\) fs\(\phantom{0}^{2}\) in the Dazzler, the individual HHG peaks are sharper and better resolved, and the signal-to-noise ratio is improved owing to a significantly reduced noise background.

Pulse duration dependent HHG spectra in ZnO. Top figure: measured HHG spectra for a GDD of – 2.3 \(\times 10^{4}\) fs\(\phantom{0}^{2}\) applied to the Dazzler, producing near-transform limited 60 fs pulses. Bottom figure: corresponding measured spectra for GDD of – 1.9 \(\times 10^{4}\) fs\(\phantom{0}^{2}\) applied to the Dazzler (160 fs pulses). Due to the large difference in signal magnitude, below-band gap and above-band gap HHG are plotted with separate vertical axes to facilitate comparison.

A central challenge in practical HHG spectroscopy is optimizing the harmonic emission while simultaneously minimizing deleterious nonlinear effects induced by the strong driving field. In bulk solid-state media, both phenomena are typically present and must be carefully managed to ensure experimental success. Our MIR OPCPA system addresses these challenges by incorporating spectral phase shaping via the Dazzler, allowing precise control over pulse characteristics with minimal impact on energy efficiency or system stability during parametric amplification. This capability allows for precise tailoring of solid-state HHG spectra and enhanced spectral clarity and tunability.

High repetition rate HHG in the XUV regime

Strong-field light-matter interactions in solids may involve the excitation of multi-band currents via tunnel ionization and subsequent interband transitions25. Typically, the required intensities for such processes are comparable to the damage threshold of the sample67, which poses considerable experimental challenges. The damage process is complex and depends not only on the material, but also on laser parameters such as the wavelength, pulse duration, repetition rate and spatial beam profile. For femtosecond pulses, the key source of damage originates from multi-photon absorption that produces free electrons whose energy is transferred to the lattice after the pulse has passed68,69. Any residual absorption or heating of the samples is exacerbated in a vacuum environment. Without an effective route to conduct heat out of the sample, thermal-induced stress can lead to distortion or breakage.

This mechanism is highly dependent on the incident laser power, which in turn is the product of the pulse energy and the laser repetition rate. Avoiding damage can limit the experimentally feasible repetition rate for OPCPAs driving free-standing crystals in vacuum, as is the norm for detection of XUV high harmonics. To mitigate such effects, pulse compression to the few-cycle regime29,70 and the use of multi-colour pulse synthesis71 have been employed. Both methods exercise control over the ionization rate by reshaping the intensity envelope of the pulse. In general, the ability to perform HHG experiments while overcoming the onset of laser-induced damage—in vacuum and at laser high repetition rates—remains a persistent bottleneck in the advancement of solid-state HHG techniques.

As a demonstration of solid-state HHG spectroscopy, we perform an orientation-dependent measurement that resolves structural anisotropy encoded in the harmonic spectrum. This angular dependence, observed in earlier pioneering studies, highlights the high spatial sensitivity of the HHG process72. In Fig. 11, we describe orientation-dependent HHG spectra for (a) MgO and (b) \(\alpha\)-quartz, driven by 2.1 \(\upmu\)m, 20 fs pulses from the SWIR OPCPA. In MgO, the incident pulse energy was 27 \(\upmu\)J at a 50 kHz repetition rate, with the peak intensity at the crystal estimated to be approximately \(5 \times 10^{12}\) W/cm\(\phantom{0}^{2}\). Under these experimental conditions, we observe no signs of laser induced damage in the vacuum despite the high peak intensity and repetition rates. This contrasts with our previous experience using shorter-wavelength drivers from Ti:S-pumped OPAs, where similar intensities led to damage in the same samples. We observe odd harmonics in MgO covering the 17th to 37th orders (10-22 eV), with each harmonic order displaying a four-fold symmetry pattern with respect to orientation. In Fig. 11a we show the angular dependence for the three strongest peaks in the HHG spectrum. As expected, we observe maxima at \(0^{\circ }\), \(90^{\circ }\), \(180^{\circ }\), and \(270^{\circ }\) that correspond to the nearest neighbour Mg–O bonding directions of the cubic lattice. Weaker maxima appear along the \(45^{\circ }\), \(135^{\circ }\), \(225^{\circ }\), and \(315^{\circ }\) orientations for some harmonic orders, e.g. H23, corresponding to the Mg–Mg or O–O directions. These observations are consistent with results from prior works25,72. However, the ability to perform XUV experiments at 50 kHz paves the way for more efficient, accelerated HHG spectroscopy.

Orientation-dependent HHG emission for (a) MgO, and (b) quartz. In (a), a free-standing, 50 \(\upmu\)m thick MgO single crystal (\(<100>\)) was driven at 2.1 \(\upmu\)m, 20 fs pulses from the SWIR OPCPA. The incident pulse energy was 27 \(\upmu\)J, the repetition rate was 50 kHz, and the beam was focused by an f \(=40\) cm CaF\(\phantom{0}_{2}\) lens. The peak intensity is estimated as \(\sim 5 \times 10^{12}\) W/cm\(\phantom{0}^{2}\). The plot shows the three strongest harmonic orders: 23, 25, and 27. In (b), a free-standing, 20 \(\upmu\)m thick z-cut, \(\alpha\)-quartz single crystal was driven by 2.1 \(\upmu\)m, 20 fs, 230 \(\upmu\)J pulses at 10 kHz, and focused with a f \(=20\) cm CaF\(\phantom{0}_{2}\) lens, to an intensity \(\sim 2 \times 10^{13}\) W/cm\(\phantom{0}^{2}\). The plot shows two pairs of adjacent odd and even harmonic orders: one in the plateau region (H22, H23) and another near the cutoff (H35, H36). For both crystals, the orientation of the crystal axes with respect to the laser polarization was controlled by a rotation motor perpendicular to the beam propagation direction. For MgO, the zero-degree (45-degree) alignment corresponds to the laser polarization aligned along the \(\Gamma - X\) (\(\Gamma -K\)) direction. For \(\alpha\)-quartz, the zero-degree (30-degree) alignment corresponds to the laser polarization along the \(\Gamma - K\) (\(\Gamma -M\)) direction. The HHG emissions were measured in transmission with a flat field spectrometer consisting of an aberration-corrected laminar-type replica diffraction grating (Shimadzu) that focuses the harmonics onto a micro channel plate (MCP) coupled to a phosphor screen, which are then imaged with a CCD camera. With fixed crystal orientation, HHG RMS stability is around 5 \(\%\) for MgO and 15\(\%\) for \(\alpha\)-quartz.

We attribute the ability to perform HHG spectroscopy at 50 kHz to the long central wavelength of 2.1 \(\upmu\)m, which reduces the likelihood of multiphoton absorption—a primary mechanism of damage in solids. Although we observe weak plasma generation at the laser focus in the crystal, there is no evidence of strong filaments and spatiotemporal collapse of the pulse that can easily result in sample damage. In this regard, the excellent far-field spatial profile of the SWIR beam (see Fig. 6), characterized by the absence of localized hot spots, significantly reduces the risk of damage from focused, high-intensity femtosecond pulses.

In \(\alpha\)-quartz, we applied an incident pulse energy of 230 \(\upmu\)J at a 10 kHz repetition rate, with the peak intensity at the crystal estimated to be approximately \(2 \times 10^{13}\) W/cm\(\phantom{0}^{2}\). Due to the crystal’s broken inversion symmetry, we observe both even and odd harmonics covering the 17th to 37 orders. In Fig. 11b we show the angular dependence for two pairs of adjacent even/odd harmonics in the plateau region and near the cutoff energy. Quartz possesses a threefold rotational symmetry, but exhibits six-fold symmetry in its HHG response when driven by a linearly polarized field36,73,74. This response is clearly seen in our experimental measurements. Compared to MgO, quartz has a higher band gap energy (9.6 eV vs. 7.9 eV for MgO) and significantly lower thermal conductivity. Thus, it is necessary to apply higher pulse energies and tighter focusing conditions to reach sufficient peak intensities for HHG. Although operating at such high intensities requires a reduced repetition rate of 10 kHz to avoid damage, this nonetheless highlights the flexibility of our OPCPA system in enabling HHG spectroscopy at both high intensities and high data acquisition rates under appropriate conditions.

Conclusions

In this work, we have presented a 50 kHz dual-output OPCPA system, pumped by a single Yb:YAG laser, that delivers simultaneous and independently tunable outputs in both the SWIR and MIR spectral regions. This configuration enables parallel exploration of distinct regimes in attosecond and strong-field science using a single, integrated laser platform. Each OPCPA arm offers unique strengths tailored to different experimental demands: the SWIR output provides high pulse energies (up to 420 \(\upmu\)J at 1.75 \(\upmu\)m and 350 \(\upmu\)J at 2.1 \(\upmu\)m) and high peak powers, supporting few-cycle pulse durations as short as 20 fs at 2.1 \(\upmu\)m -- sufficient for driving HHG in both high-band gap solids and gas-phase targets. The MIR output offers broad tunability from 2.5 to 7.6 \(\upmu\)m, enabling solid-state HHG spectroscopy across a diverse set of materials with widely varying band gap energies.

We demonstrated the functionality and versatility of the system by implementing a spectral-phase shaping strategy in the MIR to control the HHG while simultaneously suppressing deleterious nonlinear effects that often arise in bulk solid-state media. In the SWIR, we demonstrated the ability to drive high-repetition-rate XUV HHG in vacuum from free-standing crystals without observable damage -- highlighting the system’s suitability for high-throughput solid-state spectroscopy.

In future experiments, we hope to take advantage of the capabilities of our system to drive state-of-the-art experiments involving both OPCPA outputs. Both OPCPA outputs originate from a common source—the 1-\(\upmu\)m pump laser that drives both systems. As a result, the timing jitter between the two is expected to be less than one optical cycle, and potentially as low as tens of attoseconds75, enabling new experimental directions that rely on their combined outputs. One promising direction is to probe lattice dynamics in solids with HHG spectroscopy. This could be achieved by using the SWIR output to excite the sample -- either through stimulated impulsive Raman excitation at 1.7 or 2.1 \(\upmu\)m, or by generating THz pulses to resonantly drive phonons76. The resulting dynamics could then be tracked using the tunable MIR OPCPA as an HHG probe. This approach effectively combines the complementary strengths of both systems: the high pulse energy of the SWIR OPCPA (crucial for THz generation) and the broad tunability of the MIR OPCPA, which is well-suited for HHG spectroscopy across a wide range of materials.

Another possibility is to drive HHG using a synthesized, bichromatic field by combining the outputs of both OPCPAs. Driving HHG with incommensurate fields—rather than a fundamental field combined with its second or third harmonic—offers a straightforward pathway to generating isolated attosecond pulses77 and can enhance the efficiency of solid-state HHG by orders of magnitude71. Such schemes also pave the way toward resolving attosecond dynamics in solids by studying the HHG spectral response with respect to variations in shaped laser fields.

Additionally, both OPCPAs support passive CEP-stable operation. In the SWIR OPCPA, the initial seed is generated via a DFG process, while in the MIR OPCPA, passive CEP stability is achieved through DFG in the final OPA stage, where the MIR output is produced55,78. In our current system, active CEP stabilization can be achieved through modifications to the Dazzler electronics, without altering the optical layout. Indeed, CEP-stable operation at high repetition rates has been demonstrated across the wavelength ranges covered by our system10,48 paving the way for future implementation of phase-sensitive measurements and CEP control of attosecond processes. Looking forward, the modular and upgradeable design of the system offers exceptional flexibility as experimental demands evolve. With its combined performance, tunability, and stability, this dual-OPCPA platform is well positioned to drive future advances in strong-field physics and attosecond science.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Brabec, T. (ed.) Strong Field Laser Physics (Springer, 2009).

Corkum, P. B. & Krausz, F. Attosecond science. Nat. Phys. 3, 381–387. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys620 (2007).

Biegert, J., Calegari, F., Dudovich, N., Quéré, F. & Vrakking, M. Attosecond technology(ies) and science. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 54, 070201. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6455/abcdef (2021).

Backus, S., Durfee, I., Charles, G., Murnane, M. M. & Kapteyn, H. C. High power ultrafast lasers. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 69, 1207–1223. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1148795 (1998).

Golinelli, A. et al. CEP-stabilized, sub-18 fs, 10 kHz and TW-class 1 kHz dual output Ti: Sa laser with wavelength tunability option. Opt. Express 27, 13624–13636. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.27.013624 (2019).

Langdon, B. et al. Carrier-envelope-phase stabilized terawatt class laser at 1 kHz with a wavelength tunable option. Opt. Express 23, 4563–4572. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.23.004563 (2015).

Cerullo, G. & De Silvestri, S. Ultrafast optical parametric amplifiers. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 74, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1523642 (2003).

Manzoni, C. & Cerullo, G. Design criteria for ultrafast optical parametric amplifiers. J. Opt. 18, 103501. https://doi.org/10.1088/2040-8978/18/10/103501 (2016).

Fattahi, H. et al. Third-generation femtosecond technology. Optica 1, 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1364/OPTICA.1.000045 (2014).

Thiré, N. et al. Highly stable, 15 W, few-cycle, 65 mrad CEP-noise mid-IR OPCPA for statistical physics. Opt. Express 26, 26907–26915. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.26.026907 (2018).

Thiré, N. et al. A versatile high-average-power ultrafast infrared driver tailored for high-harmonic generation and vibrational spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 13, 18874. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46325-3 (2023).

Qu, S. et al. 9 \(\upmu\)m few-cycle optical parametric chirped-pulse amplifier based on LiGaS2. Opt. Lett. 44, 2422–2425. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.44.002422 (2019).

Namboodiri, M. et al. Versatile few-cycle high-energy MID-IR OPCPA for nonlinear optics, spectroscopy and imaging. Opt. Continuum 1, 1157–1164. https://doi.org/10.1364/OPTCON.451879 (2022).

Buss, J. H. et al. Few-cycle OPCPA at 2 µm with up to 100 W average power. In: OSA High-brightness Sources and Light-driven Interactions Congress 2020 (EUVXRAY, HILAS, MICS), HF1B.3. https://doi.org/10.1364/HILAS.2020.HF1B.3 (Optica Publishing Group, 2020).

Buss, J. H. et al. High-power OPCPAs at 1450–2400 nm wavelength. In: Schunemann, P. G. & Schepler, K. L. (eds.) Nonlinear Frequency Generation and Conversion: Materials and Devices XX, vol. 11670, 116700Y. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2578795. International Society for Optics and Photonics (SPIE, 2021).

Seeger, M. F. et al. 49 W carrier-envelope-phase-stable few-cycle 2.1 \(\upmu\)m OPCPA at 10 kHz. Opt. Express 31, 24821–24834. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.493326 (2023).

He, L. et al. Dual-wavelength spectrum-shaped mid-infrared pulses and steering high-harmonic generation in solids. Ultrafast Sci. 3, 0022. https://doi.org/10.34133/ultrafastscience.0022 (2023).

Dubietis, A. & Matijošius,. A. Table-top optical parametric chirped pulse amplifiers: Past and present. Opto-Electron. Adv.6, 220046-1–220046-27. https://doi.org/10.29026/oea.2023.220046 (2023).

Budriūnas, R., Jurkus, K., Vengris, M. & Varanavičius, A. Long seed, short pump: converting Yb-doped laser radiation to multi-µJ few-cycle pulses tunable through 2.5–15 µm. Opt. Express30, 13009–13023. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.455180 (2022).

Calegari, F., Sansone, G., Stagira, S., Vozzi, C. & Nisoli, M. Advances in attosecond science. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 49, 062001.https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-4075/49/6/062001 (2016).

DiChiara, A. D., Ghmire, S., Reis, D. A., DiMauro, L. F. & Agostini, P. Strong-Field and Attosecond Physics with Mid-infrared Lasers 81–98 (Springer, 2013).

Ghimire, S. et al. Observation of high-order harmonic generation in a bulk crystal. Nat. Phys. 7, 138–141. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys1847 (2011).

Vampa, G. et al. All-optical reconstruction of crystal band structure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 193603. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.193603 (2015).

Vampa, G. et al. Linking high harmonics from gases and solids. Nature 522, 462–464 (2015).

Uzan, A. J. et al. Attosecond spectral singularities in solid-state high-harmonic generation. Nat. Photon. 14, 183–187 (2020).

Uzan-Narovlansky, A. J. et al. Observation of interband Berry phase in laser-driven crystals. Nature 626, 66–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06828-5 (2024).

Uchida, K. et al. High-order harmonic generation and its unconventional scaling law in the Mott-insulating Ca\(\phantom{0}_{2}\)RuO\(\phantom{0}_{4}\). Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 127401. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.128.127401 (2022).

Lv, Y.-Y. et al. High-harmonic generation in Weyl semimetal \(\beta\)-WP\(\phantom{0}_{2}\) crystals. Nat. Commun. 12, 6437. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26766-y (2024).

You, Y. S. et al. High-harmonic generation in amorphous solids. Nat. Commun. 8, 724 (2017).

Li, J. et al. Attosecond science based on high harmonic generation from gases and solids. Nat. Commun. 11, 2748 (2020).

Luu, T. T. et al. Extreme ultraviolet high-harmonic spectroscopy of solids. Nature 521, 498–502 (2015).

Nagai, K., Okamoto, T., Shinohara, Y., Sanada, H. & Oguri, K. High-harmonic spin-orbit angular momentum generation in crystalline solids preserving multiscale dynamical symmetry. Sci. Adv. 10, eado7315. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ado7315 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. High-harmonic spectroscopy probes lattice dynamics. Nat. Photon. 18, 792–978. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-024-01457-4 (2024).

Kruchinin, S. Y., Krausz, F. & Yakovlev, V. S. Colloquium: Strong-field phenomena in periodic systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 021002. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.90.021002 (2018).

Keldysh, L. V. Ionization in the Field of a Strong Electromagnetic Wave, 56–63 (1964). https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/pdf/10.1142/9789811279461_0008.

Luu, T. T., Scagnoli, V., Saha, S., Heyderman, L. J. & Wörner, H. J. Generation of coherent extreme ultraviolet radiation from \(\alpha\)-quartz using 50 fs laser pulses at a 1030 nm wavelength and high repetition rates. Opt. Lett. 43, 1790–1793. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.43.001790 (2018).

Chénais, S., Druon, F., Forget, S., Balembois, F. & Georges, P. On thermal effects in solid-state lasers: The case of ytterbium-doped materials. Prog. Quantum Electron. 30, 89–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pquantelec.2006.12.001 (2006).

Marangos, J. P. Development of high harmonic generation spectroscopy of organic molecules and biomolecules. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 49, 132001. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-4075/49/13/132001 (2016).

Heyl, C., Arnold, C. L., Couairon, A. & L’Huillier, A. Introduction to macroscopic power scaling principles for high-order harmonic generation. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 50, 013001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6455/50/1/013001 (2016).

Comby, A. et al. Relaxation dynamics in photoexcited chiral molecules studied by time-resolved photoelectron circular dichroism: Toward chiral femtochemistry. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 4514–4519. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b02065 (2016).

Sanchez, A. et al. Tailoring quantum trajectories for strong-field imaging. Optica 10, 1729–1736. https://doi.org/10.1364/OPTICA.494719 (2023).

Wolter, B. et al. Strong-field physics with mid-IR fields. Phys. Rev. X 5, 021034. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.5.021034 (2015).

Rajak, D. et al. Laser-induced electron diffraction in chiral molecules. Phys. Rev. X 14, 011015. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.14.011015 (2024).

Tournois, P. Acousto-optic programmable dispersive filter for adaptive compensation of group delay time dispersion in laser systems. Opt. Commun. 140, 245–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0030-4018(97)00153-3 (1997).

Fuji, T. et al. Parametric amplification of few-cycle carrier-envelope phase-stable pulses at 2.1 \(\upmu\)m. Opt. Lett. 31, 1103–1105. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.31.001103 (2006).

Verluise, F., Laude, V., Cheng, Z., Spielmann, C. & Tournois, P. Amplitude and phase control of ultrashort pulses by use of an acousto-optic programmable dispersive filter: Pulse compression and shaping. Opt. Lett. 25, 575–577. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.25.000575 (2000).

Maksimenka, R. & Jousselin, H. Dazzler–25 years in control of light. In: Yurish, S. Y. (ed.) 7th International Conference on Optics, Photonics and Lasers, 195–197 (IFSA Publishing, 2024).

Maksimenka, R., Jargot, G., Thiré, N., Pertot, Y. & Forget, N. Ultra-stable OPCPA at 2 \(\upmu\)m, 16 fs, sub 100 mrad CEP noise. In: OSA High-brightness Sources and Light-driven Interactions Congress 2020 (EUVXRAY, HILAS, MICS), MM1C.3. https://doi.org/10.1364/MICS.2020.MM1C.3 (Optica Publishing Group, 2020).

Namboodiri, M. et al. Optical properties of Li-based nonlinear crystals for high power mid-IR OPCPA pumped at 1 \(\upmu\)m under realistic operational conditions. Opt. Mater. Express 11, 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1364/OME.414478 (2021).

Tian, K., He, L., Yang, X. & Liang, H. Mid-infrared few-cycle pulse generation and amplification. Photonics 8, 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics8080290 (2021).

Smetanin, S. N. et al. 50 \(\upmu\)J level, 20-picosecond, narrowband difference-frequency generation at 4.6, 5.4, 7.5, 9.2, and 10.8 \(\upmu\)m in LiGaS\(\phantom{0}_{2}\) and LiGaSe\(\phantom{0}_{2}\) at Nd:YAG laser pumping and various crystalline Raman laser seedings. Opt. Mater. Express10, 1881–1890. https://doi.org/10.1364/OME.395370 (2020).

Zhou, L., Novák, O., Smrž, M. & Mocek, T. Analysis of broadband mid-infrared optical parametric amplification based on LiGaS\(\phantom{0}_{2}\), LiGaSe\(\phantom{0}_{2}\), LiInS\(\phantom{0}_{2}\), and LiInSe\(\phantom{0}_{2}\) crystals. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 39, 1174–1185. https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSAB.454372 (2022).

Thiré, N. et al. 4-W, 100-kHz, few-cycle mid-infrared source with sub-100-mrad carrier-envelope phase noise. Opt. Express 25, 1505–1514. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.25.001505 (2017).

Maingot, B., Forget, N. & Jullien, A. Spatial-to-spectral phase coupling mechanisms in bulk continuum generation. J. Phys. Photonics 6, 035002. https://doi.org/10.1088/2515-7647/ad41ac (2024).

Baltuška, A., Fuji, T. & Kobayashi, T. Controlling the carrier-envelope phase of ultrashort light pulses with optical parametric amplifiers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 133901.https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.133901 (2002).

Thai, A., Tajahuerce, E., Andrés, P., Bates, P. K. & Biegert, J. OPCPA using beams shaped by diffractive optical elements. In: CLEO/Europe and EQEC 2011 Conference Digest (2011).

Moulet, A., Grabielle, S., Cornaggia, C., Forget, N. & Oksenhendler, T. Single-shot, high-dynamic-range measurement of sub-15 fs pulses by self-referenced spectral interferometry. Opt. Lett. 35, 3856–3858. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.35.003856 (2010).

Vampa, G. et al. Attosecond synchronization of extreme ultraviolet high harmonics from crystals. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 53, 144003.https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6455/ab8e56 (2020).

Orenstein, G. et al. Shaping electron-hole trajectories for solid-state high harmonic generation control. Opt. Express 27, 37835–37845. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.27.037835 (2019).

Kim, Y. W. et al. Compensation of laser propagation effects within solids for high harmonic generation of extreme ultraviolet radiation. Opt. I Laser Technol. 145, 107507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2021.107507 (2022).

Journigan, T. et al. High harmonic generation in epitaxially grown zinc oxide films. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 41, B1–B6. https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSAB.503550 (2024).

Domanchin, J.-L. & Gilchrist, J. R. Size and spectrum. Photon Spec. 35, 112–118 (2001).

Gholam-Mirzaei, S., Beetar, J. & Chini, M. High harmonic generation in ZnO with a high-power mid-IR OPA. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 061101. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4975362 (2017).

Gaeta, A. L. Catastrophic collapse of ultrashort pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 3582–3585. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.3582 (2000).

Couairon, A. & Mysyrowicz, A. Femtosecond filamentation in transparent media. Phys. Rep. 441, 47–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2006.12.005 (2007).

Chin, S. L. Femtosecond laser filamentation. In: Volume 55 of Springer Series on Atomic, Optical, and Plasma Physics, (Springer, 2010).

Park, J., Subramani, A., Kim, S. & Ciappina, M. F. Recent trends in high-order harmonic generation in solids. Adv. Phys. X 7, 2003244. https://doi.org/10.1080/23746149.2021.2003244 (2022).

Stuart, B. C., Feit, M. D., Rubenchik, A. M., Shore, B. W. & Perry, M. D. Laser-induced damage in dielectrics with nanosecond to subpicosecond pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 2248–2251. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.2248 (1995).

Wood, R. M. Laser-Induced Damage of Optical Materials (CRC Press, 2003).

You, Y. S. et al. Laser waveform control of extreme ultraviolet high harmonics from solids. Opt. Lett. 42, 1816–1819. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.42.001816 (2017).

Bruner, B. D. et al. Control and enhancement of multiband high harmonic generation by synthesized laser fields. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 54, 154001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6455/ac1b67 (2021).

You, Y. S., Reis, D. & Ghimire, S. Anisotropic high-harmonic generation in bulk crystals. Nat. Phys. 13, 345–349.https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3955 (2017).

Heinrich, T. et al. Chiral high-harmonic generation and spectroscopy on solid surfaces using polarization-tailored strong fields. Nat. Commun. 12, 3723. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23999-9 (2021).

Jürgens, P. et al. Linking high-harmonic generation and strong-field ionization in bulk crystals. ACS Photonics 11, 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.3c01436 (2024).

Schubert, O. et al. Rapid-scan acousto-optical delay line with 34 kHz scan rate and 15 as precision. Opt. Lett. 38, 2907–2910. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.38.002907 (2013).

Giorgianni, F. et al. Terahertz displacive excitation of a coherent Raman-active phonon in V\(\phantom{0}_2\)O\(\phantom{0}_3\). Commun. Phys. 5, 103. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-022-00882-7 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. Attosecond pulses from a solid driven by a synthesized two-color field at megahertz repetition rate. ACS Photonics 12, 2819–2827. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.5c00410 (2025).

Fan, G. et al. Hollow-core-waveguide compression of multi-millijoule CEP-stable 3.2 \(\upmu\)m pulses. Optica 3, 1308–1311. https://doi.org/10.1364/OPTICA.3.001308 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank Yossi Pilas for his valuable assistance in maintaining the laser system. N.D. is the incumbent of the Robin Chemers Neustein Professorial Chair. N.D. acknowledges the Minerva Foundation, the Israeli Science Foundation and the European Research Council for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.M., N.T., and Y.P. built the laser. R.M. and N.T. installed the laser and performed the diagnostic measurements with B.D.B. and L.F. B.D.B., L.F., R.W., N.C., and T.A.-P. performed the HHG measurements and analyzed the data. The manuscript was written by B.D.B. with input from all authors. N.T., Y.P., and N.D. led the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bruner, B.D., Maksimenka, R., Thiré, N. et al. High power, dual SWIR-MIR OPCPA source for high-order harmonics generation. Sci Rep 15, 34438 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17540-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17540-x