Abstract

This study aimed to assess the psychological characteristics of patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD), focusing on perceived social support, self-efficacy, and emotional symptoms such as depression and anxiety. Additionally, we investigated whether perceived social support mediates the relationship between self-efficacy and these mood disorders. This cross-sectional survey involved 1,144 CVD patients drawn from the 2021 China Family Health Index Survey Report. Participants completed standardized measures including a Demographic Inventory, the Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS), the New General Self-Efficacy Scale (NGSES), the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). Nonparametric analyses, chi-square tests, linear regression, and mediation analyses using the PROCESS macro were performed. Among Chinese CVD patients, depression and anxiety prevalence were 19.6% and 47.1%, respectively. Median scores were 60 (IQR 50–69) for perceived social support and 29 (IQR 24–32) for self-efficacy. Regression analyses showed significant negative associations between perceived social support and depression (β=-0.092, p < 0.001) and anxiety (β=-0.075, p < 0.001). Mediation models indicated associated with emotional disturbances via support perception (indirect effects: depression=-0.113, anxiety=-0.092). These findings highlight the potential relevance of psychosocial resources in managing emotional well-being among CVD patients and suggest that perceived social support may be an important target for forthcoming psychosocial interventions. However, due to the cross-sectional design, causal reasoning is avoided, and longitudinal studies are needed to confirm these associations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a non-specific term describing coronary artery disease, heart failure, hypertension, and other related conditions, all of which contribute to high morbidity and mortality worldwide1. According to WHO, CVD contributes to 31% of global deaths, with psychological comorbidities recognized as key determinants of disease progression2. A bidirectional association exists between CVD and mental health disturbances, where disease-related stress exacerbates symptoms of depression and anxiety in affected individuals, while persistent depression and anxiety symptoms accelerate pathological deterioration in cardiac patient.

Among many subtypes of CVD, hypertension is a common condition with well- documented psychological outcomes. For instance, research confirms strong relationships between hypertension and affective disorders, with depression and anxiety disorders being 2.69 times as frequent among hypertensive compared to normotensive people3. Population-based analyses reveal 21% and 41% elevated coronary heart disease risks associated with depressive and anxious states respectively, compared to psychologically healthy cohorts4. Clinical evaluations identify concurrent mood disturbances in 31% of individuals diagnosed with coronary artery disease5.

Perceived social support is the individual’s subjective evaluation of support received from family, friends, and important others, and is usually been quantified by the Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS)6. Perceived social support is a protective element of mental health since it serves as a buffer against stress and enhances emotional resilience. Self-efficacy describes the confidence individuals have in their ability to perform actions necessary for achieving desired outcomes7. Evidence from multiple studies has shown that higher self-efficacy is linked to lower levels of depression and anxiety, and longitudinal research indicates that interventions enhancing self-efficacy can help alleviate these symptoms in patients with CVD8,9,10. From the perspective of social cognitive theory, individuals with limited self-efficacy often view themselves as less capable of handling the challenges posed by illness, which in turn heightens their risk of experiencing depressive and anxiety symptoms10. General self-efficacy, quantified by the New General Self-Efficacy Scale (NGSES), is a measure of an individual’s belief in their ability to manage a broad range of stressors, which is particularly valuable for patients with chronic diseases like CVD. People with a high level of perceived social support are more likely to experience a sense of connection, respect, and understanding, which can help foster a sense of belonging11.

Empirical evidence has consistently shown that subjective social support functions as a buffer to stress and is inversely related with depression and anxiety symptoms in CVD populations12. Interventions aimed at enhancing social support have also shown benefits in reducing depression and anxiety symptoms in CVD patients13. As such, perceived social support acts as an external resource, reducing psychological burden and alleviating depression and anxiety symptoms. Furthermore, evidence suggests social support can enhance self-efficacy, thereby indirectly mitigating depression and anxiety symptoms14. Despite these established associations, large-scale studies examining perceived social support as a mediator between self-efficacy and depression and anxiety symptoms in CVD patients remain scarce.This study uses data from the 2021 China Family Health Index Survey Report, a large, nationally representative sample of 23 provinces, 5 autonomous regions, and 4 municipalities in mainland China which comprised. Stratified quota sampling based on national census data ensured demographic and geographic representativeness. Focusing on 1,144 CVD adults, this study applies a mediation model to test the mediating role of perceived social support in self-efficacy and depression and anxiety symptoms. While earlier studies have explored associations between psychosocial variables and emotional symptoms in CVD patients, they are mostly based on Western samples and limited in scale, and few have explicitly examined the mediating mechanism linking self-efficacy, perceived social support, and emotional outcomes. To address this gap, the current study utilizes a large, nationally representative sample from China to investigate whether perceived social support mediates the association between self-efficacy and symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with CVD. In doing so, it offers new insight into culturally generalizable psychosocial mechanisms underlying mental health in chronic illness contexts. To our knowledge, this is among the first study to utilize rich, nationally representative data from China to uncover psychosocial mechanisms influencing mental health in CVD patients, thereby providing novel insights with strong generalizability beyond Western populations.

Due to the cross-sectional design of this study, we could not differentiate between primary anxiety (arising independently) and secondary anxiety (resulting from a medical condition). The focus was on recent severity of anxiety symptoms, regardless of etiology, to identify its associations with psychosocial constructs such as self-efficacy and perceived social support. All participants reported a self-reported diagnosis of CVD, but the nature and cause of anxiety symptoms were not differentiated. Though we did not differentiate anxiety by its etiology, previous research shows that both primary and secondary anxiety in the chronic illness contexts respond similarly to psychosocial interventions15. Correspondingly, perceived social support and self-efficacy then would have equivalent protective effects regardless of the origin of anxiety symptoms. These protective effects may act through several psychological mechanisms, including enhanced emotional regulation, increased perceived control, and more adaptive coping strategies. These pathways have been implicated in both the emergence and alleviation of depression and anxiety symptoms in patients with chronic illnesses. In addition, a previous history of depression or anxiety was not employed as an exclusion criterion, to enroll a broad and ecologically valid spectrum of psychological experiences among CVD patients, aligned with the study’s aim to reflect real-world clinical populations16. Whereas the anxiety scale used in this study specifically assesses generalized anxiety disorder, previous evidence indicates that it is capturing central anxiety symptomatology that substantially overlaps with other anxiety disorders in chronic illness contexts. These design choices, while enhancing generalizability, are acknowledged as methodological limitations, and are discussed in detail in the Discussion section. The following hypotheses to be tested are as follows: (1) Higher self-efficacy is associated with lower depression and anxiety symptoms; (2) Perceived social support mediates the relationship between self-efficacy and depression symptoms; (3) Perceived social support mediates the relationship between self-efficacy and anxiety symptoms; (4) Both mediation effects remain significant after controlling for sociodemographic variables.

Objects and methods

Objects

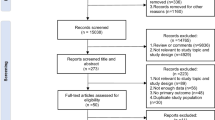

From July 10 to September 15, 2021, a cross-sectional survey was carried out throughout mainland China, including the capital cities of 23 provinces, 5 autonomous regions, and 4 municipalities directly governed by the central government. Multi-level sampling technique was employed, with 2–6 urban centers randomly chosen from each non-provincial prefecture-level division, ultimately comprising 120 surveyed cities. Demographic-stratified quota sampling was implemented according to the 20th National Population Census data to ensure collected samples matched gender ratios, age groups, and urban-rural distributions aligned with census-reported population parameters17,18. Following informed consent acquisition, electronic questionnaires were administered through personalized interviews using Questionnaire Star platform. Investigators facilitated digital responses via internet-accessible links while substituting participants lacking sufficient cognitive capacity to independently complete surveys, despite possessing basic comprehension abilities. Eligible participants comprised Chinese nationals meeting these criteria: (1) Individuals aged above 18 years; (2) Permanent mainland residents (annual absence duration ≤ 1 month); (3) Voluntary engagement with signed consent documentation; (4) Capacity for independent or assisted digital questionnaire completion; (5) Full comprehension of survey items. Exclusion conditions included: 1) Subjects with diagnosed cognitive disorders (e.g., dementia) or psychotic conditions (e.g., schizophrenia);2) Current participation in psychological intervention trials; 3) non-cooperative participants. Ethical approval was granted by Shaanxi Provincial Research Center for Health Culture (JKWH-2021-01). Participants provided informed consent not only for participation but also for the secondary analysis of their data, including psychological assessments, ensuring ethical compliance with data usage.

The survey initiative administered 11,709 questionnaires, achieving 11,031 completed responses with 90.34% validity rate. Among these, 9,966 participants aged ≥ 18 years met inclusion criteria, comprising 4,591 (46.1%) male and 5,375 (53.9%) female respondents, exhibiting mean participant age of 38.02 years. Screening based on self-reported diagnoses of coronary artery disease and hypertension identified 1,144 individuals with CVD, including 658 males (57.5%) and 486 females (42.5%).

Methods

Research instruments

-

(i)

Demographic Survey: A self-report demographic instrument captured socioeconomic parameters encompassing gender, age, BMI, tobacco/alcohol use, marital status, employment status, household income, and insurance coverage.

-

(ii)

PSSS: Zimit and colleagues initially introduced this Scale in 1987 to quantify perceived external assistance across familial and community dimensions19. This 12-item tool comprises two subscales comprises two subscales: Family Support (items 3, 4, 8, 11) and Friend/Other Support (items 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12), reflecting a two-factor structure commonly confirmed in psychometric analyses. Each item employs a 7-point Likert scale. Cumulative scores < 50 indicate suboptimal support levels. Psychometric evaluations demonstrated excellent reliability in this study (total α = 0.922; family α = 0.851; external α = 0.913).

-

(iii)

NGSES: Chen et al.‘s (2001) scale incorporates eight items utilizing 5-point Likert metrics (maximum = 40). Higher scores reflect greater self-efficacy20. The scale showed good internal consistency (α = 0.85–0.90) and temporal stability (r = 0.62–0.65) in validation studies.

-

(iv)

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): This validated instrument screens for depression severity based on DSM-IV criteria using nine items scored 0–3 (total range: 0–27). Thresholds categorize severity: mild (10–14), moderate (15–19), and severe (20–27) based on two-week symptom profiles21. A score ≥ 10 was used to indicate clinically relevant depression.

-

(v)

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7): Anxiety symptoms were measured with this 7-item questionnaire, using a 4-point frequency scale ranging from “never” (0) to “nearly every day” (3)22. A total score of 5 or higher indicates the presence of anxiety. The scale showed high internal reliability in this study (α = 0.912).

Quality assurance

Protocols incorporated personalized in-person interviews to maximize data validity and reliability. Exclusion parameters comprised: (i) questionnaires completed in less than 240 s, which was determined as the minimum reasonable time to thoughtfully complete the survey, thereby ensuring data quality; (ii) inconsistent response patterns detected through internal consistency verification; (iii) missing critical data fields; (iv) duplicated response sets; (v) patterned selection sequences. Missing data were handled using listwise deletion; questionnaires with incomplete or missing critical variable responses were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical processing

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0, Normally distributed continuous variables satisfying χ² assumptions were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while non-normally distributed continuous variables were reported as median (interquartile range: Q1–Q3). For variables following a normal distribution, between-group comparisons were carried out using independent t-tests for two-group analyses and ANOVA for comparisons involving more than two groups. When data did not follow a normal distribution, non-parametric tests were used, including the Mann–Whitney U test for comparisons between two groups and the Kruskal–Wallis H test for comparisons among multiple groups. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, and group differences were evaluated using the χ² test. Associations between multiple variables were evaluated using linear regression models. Mediation effects were analyzed with the PROCESS macro (version 4.0), employing 5,000 bootstrap resamples to obtain 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals23.

Results

Sample characteristics and prevalence

Among the 1,144 Chinese CVD patients, the prevalence rates of comorbid depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) and anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 5) were 19.6% and 47.1%, respectively. Measurements revealed median scores of 60 (IQR:50–69) for perceived social support and 29 (IQR:24–32) for self-efficacy metrics. Comparative analysis of perceived social support scores across demographic subgroups indicated non-significant variations by gender, age, or alcohol consumption history (all p > 0.05). However, statistically significant differences emerged for place of residence, per capita household income, educational attainment, marital status, employment status, type of health insurance, smoking history, and body mass index classifications (p < 0.05). Comprehensive comparative data are presented in Table 1.

Factors influencing perceived social support

Logistic regression analysis was performed to predict high perceived social support (PSSS ≥ 50; reference: low support, PSSS < 50). The model incorporated nine explanatory factors: gender, age, BMI category, smoking history, alcohol consumption frequency, employment status, marital status, health insurance type, and per capita household income. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05 (two-tailed). Detailed regression coefficients and odds ratios (OR) are presented in Table 2.

Mediation analysis: self-efficacy, perceived social support, and depression

Regression models

Hierarchical linear regression modeling was conducted in three steps. The initial model regressing depression on self-efficacy identified self-efficacy as a significant negative predictor (β=−0.101, p = 0.001). The second model regressing perceived social support on self-efficacy revealed a significant positive association (β = 1.223, p < 0.001). The final model regressing depression on both self-efficacy and perceived social support showed that self-efficacy was no longer a significant predictor (β = 0.012, p = 0.736), while perceived social support maintained a significant negative predictor (β=−0.092, p < 0.001). Modeling parameters are presented in Table 3.

Mediation effect test

The hypothesized competence-support-depression pathway was analyzed through mediation procedures using SPSS’s PROCESS macro (Model 4) with 5000 bootstrap resamples. The indirect effect was significant, as evidenced by a 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval excluding zero (point estimate = −0.113, SE = 0.021, CI [−0.156, −0.074]). This confirms the mediating role of perceived social support. Complete mediation statistics are detailed in Table 4 Fig. 1.

Mediation analysis: self-efficacy, perceived social support, and anxiety

Regression models

A similar three-phase hierarchical linear regression approach was used for anxiety. The initial model showed self-efficacy as a significant negative predictor of anxiety (β = −0.120, p < 0.001). The second model confirmed the positive associations between self-efficacy and perceived social support (β = 1.223, p < 0.001). In the final model, the effect of self-efficacy on anxiety was no longer statistically significant (β = −0.028, p = 0.325), whereas perceived social support continued to act as a significant negative predictor (β = −0.075, p < 0.001). Full regression results are detailed in Table 5.

Mediation effect test

The mediation effect was tested using SPSS PROCESS macro (Model 4) with 5,000 bootstrap resamples. The indirect effect was significant (β = −0.095, SE = 0.023, 95% CI [−0.142, −0.052]), as the confidence interval did not include zero. Full mediation results are presented in Table 6; Fig. 2.

Discussion

Current clinical models of cardiovascular care overemphasize biometric monitoring and clinical outcomes and underrepresent psychological comorbid conditions. Three principal results arose from this multicenter study of 1,144 CVD patients: (1) High rates of psychological comorbidity (depression: 19.6%, anxiety: 47.1%); (2) Significant negative associations between perceived support/self-efficacy and emotional symptoms; (3) Perceived social support mediated 90.4% of self-efficacy’s association with depression.

Earlier studies have shown that social support can boost self-efficacy and improve mental health outcomes24. Expanding on this evidence, our research demonstrates that perceived social support serves as a mediator between self-efficacy and symptoms of depression and anxiety. In particular, higher levels of perceived social support were linked to greater self-efficacy and lower levels of both depressive and anxiety symptoms. Our findings extend previous research by (1) quantifying the mediation effect of perceived support in a large CVD cohort; (2) proving social support to be a stronger mechanism, accounting for 90.4% of the self-efficacy–depression association; (3) providing effect size estimates for the design of future intervention studies.

These results provide evidence for the incorporation of routine psychological assessment and psychosocial evaluation into cardiovascular management of particularly low self-efficacy patients. Clinicians should consider introducing specific interventions for enhancing self-efficacy and social support networks to promote emotional well-being and treatment adherence. Based on the median scores reported for self-efficacy and perceived social support, our participants recorded a median NGSES score of 29 (IQR: 24–32), representing a moderate level of self-efficacy consistent with previous findings in similar adult populations20. The median perceived social support score was 60 (IQR: 50–69), in excess of the commonly used clinical cutoff of 50, reflecting overall adequate support in this cohort. However, subgroup analyses revealed significant disparities in perceived support by demographic factors such as residence, income, education, and marital status. These findings underscore the importance of the creation of targeted psychosocial interventions responsive to particular needs within diverse demographic groups.

The pathophysiological link between mental health and cardiovascular disease is probably bidirectional through a variety of mechanisms. Chronic psychological distress may activate the renin-angiotensin system, increase oxidative stress, and accelerate atherosclerosis25. Our findings agreed with earlier research that showed social support to moderate the effect of psychological distress in patients with chronic illness26,27. Importantly, our study is among the first to demonstrate that perceived social support mediates the influence of self-efficacy on the emotional symptoms of CVD patients, thus emphasizing the clinical importance of psychosocial factors among this population.

Despite these contributions, there are some limitations worth mentioning. The cross-sectional design of our research makes it impossible to infer causality. According to Maxwell & Cole, mediation analyses based on cross-sectional data may not replicate under longitudinal designs due to temporal ambiguity28. Future research should verify these relationships using prospective designs with time-sequenced assessments.

In addition, our models explained only a small percentage of the variance in depression and anxiety symptomatology, indicating the potential for unmeasured psychological or contextual influences. All assessments were based on self-report, therefore risking the likelihood of recall and reporting biases. Furthermore, our research also did not distinguish between CVD subtypes, potentially obscuring subtype-specific psychosocial patterns. Cultural factors may also influence the interpretation of constructs like social support and self-efficacy, limiting the external validity of our findings beyond Chinese populations. Notably, we did not screen our participants for current anxiety or depression, which may have been influencing current symptom levels This approach was intentional in capturing a broad and ecologically valid spectrum of psychological experiences among CVD patients, thereby enhancing the external validity of our results. In addition, assessment of anxiety only measured generalized anxiety disorder, potentially missing other forms of anxiety (e.g., panic disorder, social anxiety). Despite these limitations, our results have broad importance for the management of cardiovascular care. These findings highlight pragmatic implications for clinicians, demonstrating the need for routine psychosocial assessments and tailored interventions that can be effectively integrated into existing cardiovascular care pathways to improve patient well-being and adherence. Considering the considerable psychological symptoms observed in this population, routine screening for depression, anxiety, and psychosocial factors such as perceived social support and self-efficacy could promote improved patient outcomes. Interventions aimed at strengthening social support systems could serve as effective adjuncts to conventional treatment, potentially improving patients’ psychological resilience and treatment adherence.

Conclusion

This research revealed elevated emotional symptoms among patients with cardiovascular disease and showed that both perceived social support and self-efficacy had negative associations with depression and anxiety. Notably, perceived social support was found to play a strong moderating role in the link between self-efficacy and emotional symptoms, explaining a substantial portion of its association with depression. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate this mediation effect in a large cohort of patients with cardiovascular disease, offering new perspectives on the psychosocial pathways contributing to emotional distress in this group. The results suggest that strengthening perceived social support could be a promising intervention strategy for improving emotional well-being in CVD patients. Nevertheless, the cross-sectional nature of the study precludes causal inference, and the directionality of the observed relationships remains unclear. Furthermore, reliance on self-reported measures and the absence of analyses stratified by CVD subtype may restrict the generalizability of the conclusions. Future longitudinal and interventional studies are needed to confirm these findings and determine whether increasing perceived social support can directly improve emotional outcomes in this population.

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Benjamin, E. J. et al. Heart disease and stroke Statistics—2019 update: A report from the American heart association. Circulation 139 (10), e56–e528. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659 (2019).

Pogosova, N. et al. Psychosocial risk factors in relation to other cardiovascular risk factors in coronary heart disease: results from the EUROASPIRE IV survey. A registry from the European society of cardiology. Eur J. Prev. Cardiol Sep. 24 (13), 1371–1380. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487317711334 (2017).

Du, C. et al. Increased resilience weakens the relationship between perceived stress and anxiety on sleep quality: A moderated mediation analysis of higher education students from 7 countries. Clocks Sleep Sep. 2 (3), 334–353. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep2030025 (2020).

Gan, Y. et al. Depression and the risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Psychiatry Dec. 24, 14:371. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0371-z (2014).

Palacios, J., Khondoker, M., Mann, A., Tylee, A. & Hotopf, M. Depression and anxiety symptom trajectories in coronary heart disease: associations with measures of disability and impact on 3-year health care costs. J Psychosom. Res Jan. 104, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.10.015 (2018).

Cohen, S. & Wills, T. A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull Sep. 98 (2), 310–357 (1985).

Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev Mar. 84 (2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.84.2.191 (1977).

Chirico, A. et al. A meta-analytic review of the relationship of cancer coping self-efficacy with distress and quality of life. Oncotarget May. 30 (22), 36800–36811. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.15758 (2017).

Johansson, P., Lundgren, J., Andersson, G., Svensson, E. & Mourad, G. Internet-Based cognitive behavioral therapy and its association with self-efficacy, depressive symptoms, and physical activity: secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial in patients with cardiovascular disease. JMIR Cardio. 6 (1), e29926. (2022). https://doi.org/10.2196/29926

Maciejewski, P. K., Prigerson, H. G. & Mazure, C. M. Self-efficacy as a mediator between stressful life events and depressive symptoms: differences based on history of prior depression. Br. J. Psychiatry. 176 (4), 373–378. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.176.4.373 (2000).

Muigg, F., Rossi, S., Kühn, H. & Weichbold, V. Perceived social support improves health-related quality of life in cochlear implant patients. Eur Arch. Otorhinolaryngol Sep. 281 (9), 4757–4762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-024-08706-w (2024).

Dour, H. J. et al. Perceived social support mediates anxiety and depressive symptom changes following primary care intervention. Depress Anxiety May. 31 (5), 436–442. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22216 (2014).

Tsuchihashi-Makaya, M., Kato, N., Chishaki, A., Takeshita, A. & Tsutsui, H. Anxiety and poor social support are independently associated with adverse outcomes in patients with mild heart failure. Circ J Feb. 73 (2), 280–287. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.cj-08-0625 (2009).

Liu, Q., Mo, L., Huang, X., Yu, L. & Liu, Y. Path analysis of the effects of social support, self-efficacy, and coping style on psychological stress in children with malignant tumor during treatment. Medicine (Baltimore) Oct. 23 (43), e22888. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000022888 (2020).

Cimpean, D. & Drake, R. E. Treating co-morbid chronic medical conditions and anxiety/depression. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci Jun. 20 (2), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1017/s2045796011000345 (2011).

Salmasi, V., Lii, T., Humphreys, K., Reddy, V. & Mackey, S. A literature review of the impact of exclusion criteria on generalizability of clinical trial findings to patients with chronic pain. PAIN Reports 11/01. 7, e1050. https://doi.org/10.1097/pr9.0000000000001050 (2022).

Wu, Y., Fan, S., Liu, D. & Sun, X. Psychological and behavior investigation of Chinese residents: Concepts, practices, and prospects. Chin. Gen. Pract. J. 1(3):149–156. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgpj.2024.07.006

Yang, Y., Fan, S., Chen, W. & Wu, Y. Broader open data needed in psychiatry: practice from the psychology and behavior investigation of Chinese residents. Alpha Psychiatry Aug. 25 (4), 564–565. https://doi.org/10.5152/alphapsychiatry.2024.241804 (2024).

Zimet, G. D., Powell, S. S., Farley, G. K., Werkman, S. & Berkoff, K. A. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers. Assess Winter. 55 (3–4), 610–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095 (1990).

Chen, G., Gully, S. M. & Eden, D. Validation of a new general Self-Efficacy scale. Organizational Res. Methods. 4 (1), 62–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810141004 (2001).

Levis, B. et al. Accuracy of the PHQ-2 alone and in combination with the PHQ-9 for screening to detect major depression: systematic review and Meta-analysis. Jama Jun. 9 (22), 2290–2300. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6504 (2020).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. & Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern. Med May. 22 (10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 (2006).

Hayes, A. F. & Rockwood, N. J. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav Res. Ther Nov. 98, 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001 (2017).

Harandi, T. F., Taghinasab, M. M. & Nayeri, T. D. The correlation of social support with mental health: A meta-analysis. Electron Physician Sep. 9 (9), 5212–5222. https://doi.org/10.19082/5212 (2017).

Geng, Y-J. Mental stress contributes to the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic heart and brain diseases: A Mini-Review. Heart Mind. 7 (3), 157–163. https://doi.org/10.4103/hm.HM-D-23-00039 (2023).

Franqueiro, A. R., Yoon, J., Crago, M. A., Curiel, M. & Wilson, J. M. The interconnection between social support and emotional distress among individuals with chronic pain: A narrative review. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 16, 4389–4399. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.S410606 (2023).

Ozbay, F. et al. Social support and resilience to stress: from neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont) May. 4 (5), 35–40 (2007).

Maxwell, S. E. & Cole, D. A. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychol Methods Mar. 12 (1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989x.12.1.23 (2007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.BW: Writing – review & editing. HH: Writing – review & editing.Data availability :The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance for this study was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Shaanxi Provincial Research Center for Health Culture (approval number: JKWH-2021-01). Written informed consent was obtained from every participant prior to data collection. All study procedures complied with the ethical standards set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, M., Wang, B. & Hui, H. Perceived social support mediates the relationship between self-efficacy and depression/anxiety in patients with cardiovascular disease. Sci Rep 15, 31603 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17559-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17559-0