Abstract

Chronic liver diseases (CLD) are closely linked to an increased load of conjugated bile acids (BAs), which contribute to liver damage and inflammation, although many aspects remain unclear. This study investigated the relationships between serum conjugated BAs, BA-related gene expression in the liver and ileum, and survival outcomes in both human and rat models of CLD. Serum BA levels, including tauro- and glyco-conjugated BAs such as taurochenodeoxycholic acid (TCDCA), were measured in 73 CLD patients and in carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced CLD rat models using LC‒MS/MS. A higher conjugated-to-free BA ratio, elevated TCDCA levels, and a lower glycine-to-taurine ratio were significantly associated with impaired liver function, increased fibrosis markers, and worse survival rates in patients. Hepatic expression levels of BA-related genes were also associated with liver damage and survival rates in CLD rat models. The rat study suggested that increased serum conjugated BAs result from reduced intestinal excretion and enhanced bloodstream flow. These findings suggest that elevated serum conjugated BAs reflect disease severity and could serve as potential biomarkers for prognosis in CLD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Altered bile acid (BA) homeostasis has been implicated in various chronic liver diseases (CLD)1. Exposure to elevated BA levels in diseased livers increases the risk of hepatotoxicity by activating inflammatory and necrotic cell death pathways2. Higher serum BA levels are associated with worse clinical outcomes; for example, serum BAs are correlated with portal hypertension and the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, and they can predict decompensation and transplant-free survival3.

BA conjugation processes produce less toxic and more water-soluble BA species, providing protection against damage caused by more toxic, hydrophobic BAs4. It is estimated that 98% of hepatic BAs are conjugated to either taurine or glycine by the enzymes such as including BA-CoA:amino acid N-acyltransferase (BAAT), which catalyzes the final step in conjugated synthesis5. However, recent studies have highlighted the involvement of tauro- and glyco-conjugated BAs in the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome, dementia and cancer cachexia6,7. In addition, elevated concentrations of conjugated BAs have been shown to significantly contribute to liver fibrosis and portal hypertension8,9. However, in CLD, the associations between BA conjugation, including changes in Baat activity, and patient prognosis remain unclear. Furthermore, the mechanism underlying the marked increase in conjugated BA levels in CLD has yet to be clarified.

This study aimed to elucidate the associations between serum conjugated BA levels, the ratio of conjugated BA to free BA, the glycine-to-taurine (G/T) ratio, hepatic BA-related gene expression levels (including Baat), and survival rates in patients with CLD and in a rat model of CLD. To further investigate the mechanism underlying the increase in conjugated BAs, we examined the expression levels of genes involved in BA reabsorption in the ileum.

Results

Patient characterization

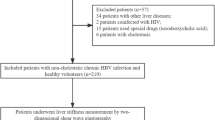

A total of 73 CLD patients, with average age 71.0 years, including 58 men and 15 women, were enrolled in the study. Diabetes was observed in 34 individuals (46.5%), hypertension in 42 (57.5%), dyslipidemia in 5 (6.8%), and hyperuricemia in 12 (16.4%). Atrial fibrillation, ischemic heart disease, emphysema, and cerebral infarction were reported in 4, 6, 4, and 2 individuals, respectively. Due to malignant tumors, three patients had a history of gastrectomy, and two had a history of colectomy. The cohort comprised patients with various underlying etiologies: 13 with hepatitis B virus (HBV), 21 with hepatitis C virus (HCV), 21 with metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), 16 with alcohol-related liver disease (ALD), and 2 with other causes. Patients infected with HBV or HCV were treated with direct-acting antivirals for HCV or nucleos(t)ide analogs for HBV as needed, and viral control was achieved. According to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system, 11 patients were classified as Stage 0, 29 as Stage A, 13 as Stage B, 19 as Stage C, and 1 as Stage D.

Serum BA levels, including conjugated BAs, showed no association with different CLD etiologies (Supplementary Fig. 1), except for GCDCA, which was significantly higher in CLD patients with ALD patients compared to those with HBV.

Correlation between BAs and laboratory variables

Glyco- and tauro-chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) were positively correlated with transaminases such as aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma-glutamyltransferase (γ-GT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (p < 0.05–0.0001); hepatic functional reserve, including albumin (Alb), albumin‒bilirubin (ALBI) score and prothrombin time (PT) (p < 0.001–0.0001); and platelet count (Plt) (p < 0.01), ammonia (NH3) (p < 0.05–0.01), sodium (Na) (p < 0.05) and fibrosis index based on 4 factors (FIB-4) index (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1a, b and Supplementary Fig. 2). The relationships between glyco- and tauro-cholic acid (CA), and taurochenodeoxycholic acid (TDCA) with transaminases, hepatic functional reserve, NH₃, Na, and the FIB-4 index were similar to those observed between GCDCA, TCDCA, and these test values (Fig. 1a, b and Supplementary Fig. 2). The serum conjugated BA levels were not significantly correlated with the renal function test results. In addition, the serum conjugated BA level was not significantly correlated with tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage or maximum tumor size (Fig. 1c).

(a) Correlations between BAs and laboratory variables; (b) Scatter plot between conjugated BAs and the ALBI or FIB4 index; (c) Correlations between BAs and the TNM stage or maximum tumor size. Positive correlations are shown with varying shades of red, whereas negative correlations are represented with varying shades of blue, according to their strength. The values in the figure represent the correlation coefficients, and * indicates statistical significance. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001. BA, bile acid; CDCA, chenodeoxycholic acid; CA, cholic acid; DCA, deoxycholic acid; LCA, lithocholic acid; G, glyco; T, tauro; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; γ-GT, gamma-glutamyltransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; Alb, albumin; T-Bil, total bilirubin; ALBI, albumin‒bilirubin; Plt, platelet count; PT, prothrombin time; NH3, ammonia; FIB-4, fibrosis index based on 4 factors; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cre, creatinine; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Na, sodium; TNM, tumor node metastasis.

In the relationship between primary BAs and laboratory variables, several correlations were observed: Alb (rs = − 0.457, p < 0.0001), AST (rs = 0.284, p < 0.05), ALP (rs = 0.294, p < 0.05), Plt (rs = − 0.234, p < 0.05), PT (rs = − 0.410, p < 0.001), and ALBI score (rs = 0.414, p < 0.001).

In contrast, no significant relationships were found between secondary BAs and laboratory variables.

Correlation between the ratio of conjugated to unconjugated BAs and laboratory variables

The correlation between the ratio of conjugated to unconjugated BAs and laboratory variables was similar to the correlation mentioned above for conjugated BA values. In brief, this ratio (GCDCA/CDCA, TCDCA/CDCA, GCA/CA, TCA/CA, GDCA/CA, and TDCA/DCA) was correlated with transaminases such as AST, ALT, γ-GT and ALP; hepatic functional reserve, including Alb, ALBI score and PT; and the Plt, NH3, Na and FIB-4 index (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). The ratio of conjugated to unconjugated BAs was not significantly correlated with the maximum tumor size or TNM stage (Supplementary Fig. 3c).

Correlation between the G/T ratio of conjugated BAs and laboratory variables

The G/T ratios of CDCA, CA, and DCA were negatively correlated with transaminases such as AST, ALT, γ-GT and ALP (p < 0.05–0.0001); hepatic functional reserve, including Alb, ALBI score and PT (p < 0.05–0.0001); and NH3 (p < 0.05), Na (p < 0.05–0.01) and the FIB-4 index (p < 0.01–0.001) (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 4). The G/T ratio of conjugated BAs was not significantly correlated with TNM stage or maximum tumor size (Fig. 2b).

(a) Correlation between the G/T ratio of conjugated BAs and laboratory variables; (b) Correlation between the G/T ratio of conjugated BAs and TNM stage or maximum tumor size. Positive correlations are shown with varying shades of red, whereas negative correlations are represented with varying shades of blue, according to their strength. The values in the figure represent the correlation coefficients, and * indicates statistical significance. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001. G/T, glycine-to-taurine; BA, bile acid; G, glyco; T, tauro; CDCA, chenodeoxycholic acid; CA, cholic acid; DCA, deoxycholic acid; LCA, lithocholic acid; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; γ-GT, gamma-glutamyltransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; Alb, albumin; T-Bil, total bilirubin; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; Plt, platelet count; PT, prothrombin time; NH3, ammonia; FIB-4, fibrosis index based on 4 factors; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cre, creatinine; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Na, sodium; TNM, tumor node metastasis.

Correlation between BAs and laboratory variables in the non-cholestatic group

When defining the non-cholestatic group as cases meeting the criteria of total BA < 10 μmol/L and T-Bil < 1.2 mg/dL, 19 cases (26% of all cases) were identified. In this group, an analysis of the relationships between various BAs and laboratory variables revealed significant correlations between GCDCA and γ-GT (rs = 0.477, p < 0.05), TCDCA and γ-GT (rs = 0.576, p < 0.01) as well as ALBI (rs = 0.461, p < 0.05). GCA showed significant correlations with AST (rs = 0.555, p < 0.05), ALT (rs = 0.614, p < 0.01), γ-GT (rs = 0.740, p < 0.001), and ALP (rs = 0.563, p < 0.05). Additionally, TCDCA/CDCA was correlated with γ-GT (rs = 0.459, p < 0.05). GCA/CA and TCA/CA were correlated with γ-GT (rs = 0.556, p < 0.05; rs = 0.394, p < 0.1, respectively) and with ALP (rs = 0.463, p < 0.05; rs = 0.432, p < 0.1, respectively). The G/T ratios of CDCA were negatively correlated with γ-GT (rs = − 0.402, p < 0.1) and ALBI score (rs = − 0.484, p < 0.05). In contrast, no associations were observed between CDCA or CA and laboratory variables. These findings suggest that even in non-cholestatic CLD, conjugated BAs undergo alterations.

Serum conjugated BAs, the ratio of BAs to their free forms and the G/T ratio are prognostic factors for survival

The significant correlation between serum conjugated BAs and liver function led us to further investigate whether conjugated BA levels are associated with survival. Among the 73 patients, 23 (31.5%) died during the average follow-up period of 1005 ± 471 days after the study period. All causes of death were considered liver related, except for one case of pancreatic cancer and one case of pneumonia. Patients with high TCAs or low GCA/TCA ratios (≥ 0.20 μmol/L, < 6.1) had significantly worse overall survival than those with lower or higher levels (p < 0.05, p < 0.01) (Fig. 3a). Patients with high TCDCA, GCDCA, and the ratio of TCDCA to its free form (TCDCA/CDCA) or low GCDCA/TCDCA levels (≥ 0.15, ≥ 1.33 μmol/L, ≥ 0.25, < 11.3, respectively) had significantly worse overall survival than those with lower or higher levels (p < 0.01, p < 0.01, p < 0.05, p < 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 3b). Patients with high TDCA/DCA or low GDCA/TDCA levels (≥ 0.045, < 8.2) had significantly worse overall survival than those with lower or higher levels (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3c).

(a–c) Serum conjugated BAs, the ratio of BAs to their free forms and the G/T ratio are prognostic factors for survival. BA, bile acid; G/T, glycine-to-taurine; GCDCA, glycochenodeoxycholic acid; TCDCA, taurochenodeoxycholic acid; GCA, glycocholic acid; TCA, taurocholic acid; TDCA, taurodeoxycholic acid.

The contribution of, BA, ALBI score, and FIB-4 index to overall survival was evaluated by univariate analysis using a Cox proportional hazards model. Significant predictors of overall survival included TCDCA (p < 0.001) and TCA (p < 0.001), as well as ALBI score (p = 0.001) and FIB-4 index (p < 0.001) (Table 1). However, no factors were identified as significant in the multivariate analysis.

Correlations between BAs and liver function parameters, as well as fibrotic and inflammatory genes, in CLD rats (animal sample 1)

To explore the association between conjugated BAs and liver function, we measured BAs in CLD rats treated with CCl4. The levels of serum total BAs and liver BAs were increased compared to wild-type (WT); however, the differences were not statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Similarly, serum primary BAs, secondary BAs, and the primary/secondary BA ratio were elevated compared to WT, but these differences were also not statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Muricholic acid (MCA) (β) or MCA (ω) was correlated with AST and ALT (p < 0.05–0.001). Glyco- and tauro-CDCA, CA, DCA, and tauro-MCA (TMCA, α + β) were correlated with transaminases such as AST and ALT (p < 0.05–0.001) and hepatic functional reserve, including ALB and total bilirubin (T-Bil) (p < 0.05–0.001) (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 6). Notably, Glyco- and tauro-CDCA, CA, DCA, and TMCA were positively correlated with the expression of genes involved in liver fibrosis and inflammation, such as alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-Sma) (p < 0.05 or 0.01), collagen type I alpha 1 chain (Col1a1) (p < 0.001 or 0.0001), connective tissue growth factor (Ctgf) (p < 0.05–0.001), metallopeptidase inhibitor 1 (Timp1) (p < 0.01–0.0001), nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (Nlrp3) (p < 0.01–0.0001), and cysteine aspartate-specific protease 1 (Casp1) (p < 0.01–0.0001). MCA (β) exhibited a correlation with Timp1 (p < 0.01) (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 7). The levels of glyco- and tauro-CDCA, CA, and DCA were significantly greater (TCA and TDCA; p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively) or tended to be greater (GCDCA, GDCA, and TMCA; p < 0.1, r = 0.51, 0.56, and 0.51, respectively) in the CLD rats than in the WT rats (Fig. 4c).

(a) Correlation between BAs and liver function in rats treated with CCl4; (b) Correlation between BAs and hepatic expression of fibrosis or inflammation markers in rats treated with CCl4. Positive correlations are shown with varying shades of red, whereas negative correlations are represented with varying shades of blue, according to their strength. The values in the figure represent the correlation coefficients, and * indicates statistical significance. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001; (c) Comparison of BA between wild-type and CCl4-treated rats; (d) Comparison of ileal expression of BA reabsorption markers between wild-type and CCl4-treated rats. BA, bile acid; CDCA, chenodeoxycholic acid; CA, cholic acid; DCA, deoxycholic acid; LCA, lithocholic acid; MCA, muricholic acid; G, glyco; T, tauro; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; Alb, albumin; T-Bil, total bilirubin; α-Sma, alpha-smooth muscle actin; Col1a1, collagen type I alpha 1 chain; Ctgf, connective tissue growth factor; Timp1, metallopeptidase inhibitor 1; Nlrp3, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3; Casp1, cysteine aspartate-specific protease 1; Slc51a, solute carrier family 51 member a; Slc51b, solute carrier family 51 member b; Slc10a2, solute carrier family 10 member 2;

Expression levels of genes involved in BA reabsorption in the ileum (animal sample 1)

Furthermore, we examined the expression of genes involved in BA reabsorption, including solute carrier family 51 alpha/beta (Slc51a/Slc51b) and the solute carrier family 10 member 2 (Slc10a2), in the rat ileum. Corresponding to serum conjugated BA levels, the expression of Slc51a, Slc51b and Slc10a2 genes was significantly enhanced compared to WT rats (p < 0.01) (Fig. 4d), suggesting that BA reabsorption in the ileum is elevated in CLD. However, there was little correlation between the expression levels of these genes and the serum BA levels or liver function test results (data not shown).

Correlations between hepatic BAs, BA-related genes, and prognosis, as well as fibrotic and inflammatory genes, in CLD rats (animal sample 2)

To further explore the associations between hepatic BAs, BA-related genes, and prognosis, we analyzed the changes in hepatic BAs and BA-related genes in CLD rats. In the livers of CLD rats, the gene expression of solute carrier family 10 member 1 (Slc10a1), which is involved in BA uptake, sterol 12α-hydroxylase (Cyp8b1), which is involved in BA synthesis, Baat, ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 11 (Abcb11), multidrug resistance-associated protein (Mrp) 2, which are involved in BA excretion, and farnesoid X receptor (Fxr), which regulates BA composition, was downregulated, whereas oxysterol 7α-hydroxylase (Cyp7b1) was upregulated compared with that in WT rats (p < 0.05). There were no significant changes in the gene expression of small heterodimer partner (Shp), cholesterol 7 alpha-hydroxylase (Cyp7a1), sterol 27-hydroxylase (Cyp27a1), and Mrp4 (Fig. 5a). There were no changes in liver BA levels compared to WT (Fig. 5b). The liver gene expression of Slc10a1, Baat, Abcb11, Mrp2, and Mrp4 was decreased in the deceased group, whereas the expression of Cyp8b1 and sterol Cyp27a1, which is involved in BA synthesis, was elevated compared with that in the survival group (p < 0.05–0.01). The liver gene expression of Shp and Cyp7b1 tended to decrease in the deceased group (p < 0.1, r = 0.47 and 0.42, respectively). On the other hand, there was no correlation between the gene expression of Cyp7a1 and Fxr and subsequent survival or death (Fig. 5c). Moreover, liver BAs were significantly decreased in the deceased rats (p < 0.001) (Fig. 5d). The hepatic gene expression of Baat was strongly negatively correlated with the expression of genes involved in liver fibrosis and inflammation, such as Ctgf (p < 0.0001), Timp1 (p < 0.0001), hyaluronan synthase (Has) 3 (p < 0.0001), interleukin-6 (Il-6) (p < 0.0001), and toll-like receptor 4 (Tlr4) (p < 0.0001). Additionally, hepatic Baat gene expression showed a strong negative correlation with serum AST (p < 0.01) and T-Bil (p < 0.01).

(a, b) Comparison of hepatic BA-related gene expression (a) and BA concentrations (b) between wild-type and cirrhotic livers in rats. (c, d) Comparison of hepatic BA-related gene expression (c) and BA concentrations (d) between the survival and dead (deceased) groups of rats. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. BA, bile acid; Slc10a1, solute carrier family 10 member 1; Shp, small heterodimer partner; Cyp7a1, cholesterol 7 alpha-hydroxylase; Cyp7b1, oxysterol 7α-hydroxylase; Cyp8b1, sterol 12α-hydroxylase; Cyp27a1, sterol 27-hydroxylase; Baat, bile acid coenzyme A: amino acid N-acyltransferase; Abcb11, ATP-binding cassette subfamily b member 11; Fxr, farnesoid X receptor; MRP, multidrug resistance-associated protein.

Discussion

Detailed serum BA analysis has reinforced previous findings of elevated serum conjugated BA levels and an increased ratio of conjugated BAs to unconjugated BAs in patients with CLD, with these changes being more pronounced in advanced stages of the disease10,11. Some of these relationships were observed even in patients without cholestasis, and changes in conjugated BAs occurred even in the early stages of CLD. Furthermore, we are the first to find that an increase in these conjugated BAs is significantly associated with an increased mortality rate in patients with CLD. In a CLD rat model, serum conjugated BAs correlated with liver function test values and liver fibrotic or inflammatory gene expression. Baat mRNA levels also correlated with liver fibrotic and inflammatory genes and were linked to survival rates. In rodents such as mice and rats, most of the CDCA is converted into MCAs by the enzyme Cyp2c70. As a result, MCAs along with CA are the predominant BAs found in the liver and bile of these species, while CDCA levels remain low. Therefore, it is appropriate to consider that MCAs in rodents is comparable to CDCA in human12. These findings have not been previously reported; however, further validation is needed to confirm them. In this study, we found that in rats with end-stage liver failure, the intrahepatic BA concentration was decreased, associated with a reduction in BA synthesis. Additionally, in rats, the expression of Abcb11 and Mrp2 in the liver was significantly decreased, while Mrp4 expression was preserved. This suggests a reduction in BA excretion into the intestines and an increased flow into the bloodstream. The elevated BAs in the bloodstream are reabsorbed by the kidneys and return to the damaged liver. These processes are considered to contribute to the increased serum levels of conjugated BAs in CLD patients and rats. Although multiple studies have suggested an association between conjugated BAs and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)13,14,15, we observed a limited correlation with liver cancer in this cohort. Instead, elevated conjugated BAs appear to result primarily from the progression of underlying liver disease.

We found that Slc51a, Slc51b and Slc10a2 expression was upregulated in the ileum of CLD rats. This is consistent with the findings of a previous study reporting increased expression of these genes16 and is presumed to be a compensatory response to the reduced BA levels in the intestinal lumen, as described above. Interestingly, SLC10A2 inhibitors have been reported to improve experimental nonalcoholic steatohepatitis or cholestatic disease by targeting SLC10A2 function in the intestine and liver, resulting in the clearance of circulating BAs and protection of the liver17,18. Conversely, our study observed a decrease in hepatic Slc10a1 expression, which encodes NTCP. This reduction in hepatic BA uptake leads to increased plasma conjugated BA levels. This elevation may contribute to the exacerbation of liver injury and inflammation. Consequently, the potential therapeutic application of Slc10a1 inhibition in CLD is currently under investigation19. These reports also indirectly support the findings of the present study.

In addition, a shift toward taurine conjugation rather than glycine conjugation in patients with CLD, which becomes more pronounced in advanced stages of the disease, is consistent with previous findings10,11,20. In the present study, the G/T ratios of conjugated BAs, such as GCA/TCA, GCDCA/TCDCA, and GDCA/TDCA, were determined to be associated with patient survival. BAAT-mediated amino acid conjugation with either glycine or taurine is the final step in BA synthesis21. Baat-/- mice are almost completely devoid of taurine-conjugated BAs in the liver, suggesting that BAAT is the primary taurine-coupled enzyme22. In the present study, Baat expression in the liver decreased in CLD model rats; however, the ratio of taurine conjugation increased in parallel with the progression of liver disease in CLD patients. Thus, it can be inferred that its function in taurine conjugation may be maintained until the terminal stage of liver failure. Furthermore, given that BAAT has a lower affinity for glycine than taurine does21, the reduced influx of unconjugated BAs from the blood into the liver may lead to a lower demand for conjugation and thus a relatively greater reduction in glyco-conjugated BAs. However, the precise mechanism underlying the preferential suppression of glyco-conjugated BAs in CLD is not clear and requires further investigation.

In this study, TCDCA, GCDCA and TCA were identified as BAs that determine the prognosis of patients with CLD. TCDCA has been reported to activate a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K)-mediated survival pathway, which induces liver damage and hepatocyte apoptosis23. Another report suggested that a progressive increase in TCDCA, GCDCA and TCA in parallel with disease severity in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis24. Furthermore, a strong association between serum TCDCA levels and the hepatic venous pressure gradient has also been reported25. Multiple reports indicate that TCDCA, GCDCA and TCA are deeply involved in the pathogenesis of liver diseases and that their levels can serve as biomarkers for predicting the progression of these diseases. However, further elucidation of the mechanisms by which these two conjugated BAs affect the liver is needed.

Studies have reported that BAs induce hepatic fibrosis and inflammation. For example, Feng et al. reported that GCDCA induces hepatic fibrosis via the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway, and FXR inhibits NLRP3 activity by restraining its phosphorylation26. Furthermore, Ali et al. reported that taurine-conjugated BAs, especially TCDCA and TCA, are the most biologically active BAs in HCV and may contribute to liver disease pathogenesis through hepatic spingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 (S1PR2)-mediated hepatic inflammation27. Indeed, serum conjugated BAs, the ratio of conjugated BAs to free BAs, and the G/T ratio were correlated with transaminases and the FIB-4 index in patients with CLD in our study. Additionally, TCDCA, GCDCA, and TCA, which have been implicated in the development of hepatic fibrosis, were identified in our study as well. The observed decrease in hepatic Fxr expression revealed in this study may also contribute to hepatic fibrosis. Conjugated BAs can promote cell survival and antiapoptotic pathways, which are thought to mitigate their inherent toxicity28. Therefore, the accumulation of taurine-conjugated BAs observed in CLDs is conventionally interpreted as an adaptive compensatory response to increase the elimination and detoxification of BAs. However, as mentioned above, conjugated BAs themselves may contribute to the progression of hepatic fibrosis. These findings suggest that the profibrotic effects of conjugated BAs may negatively impact patient outcomes.

Another interesting observation was that, as liver fibrosis progressed, while the gene expression of Slc10a1, Cyp8b1, Baat, Abcb11, Mrp2, and Fxr decreased, whereas Cyp7b1 expression increased, and Cyp7a1 expression showed a tendency to increase, which was associated with the reduction in Fxr expression. The extent of the expression of these genes was strongly associated with the survival rate of the rats. In CLD, BA synthesis is maintained while BA conjugation and enterohepatic circulation appear to be impaired, with decreased mRNA levels of Slc10a1, Baat, Abcb11, Mrp2, and Mrp4, which is consistent with the findings of a recent study27.

Despite our important findings, the present study has several limitations. First, this retrospective study at a single institution involving human subjects does not exclude the potential influence of HCC on BAs. Prospective studies of CLD patients without HCC are anticipated in the future. Second, we were unable to obtain human liver tissues or fecal samples (gut microbiota), so the relationships among these factors, BA metabolism, and prognosis could not be examined. Additionally, the relationship between the serum BA concentration and survival rate could not be evaluated in the rat study. The limitations of this study include the limited inclusion of advanced CLD with cholestasis and the inability to demonstrate a direct causal relationship between conjugated BAs and CLD progression.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that the ratio of serum conjugated BAs to free BAs increases, whereas the G/T ratio decreases in parallel with liver damage, fibrosis and inflammation. Furthermore, the increase in conjugated BAs is associated with subsequent survival rates in both humans and rat models of CLD.

Methods

Patient cohort

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Review Committee of Mie University Hospital (H2019-063). This study was performed retrospectively on stored samples, and subjects were allowed to opt out of their data being used. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects at the time of blood sampling. This cohort has been previously described in detail29. Briefly, a total of 73 treatment-naïve patients with HCC with CLD were included in this retrospective study. BCLC and TNM stages were determined on the basis of the criteria for TNM staging of HCC presented by the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan and were used to evaluate tumor progression. All the treatments were performed in accordance with the Japanese practical guidelines for HCC30. Posttreatment follow-up for HCC patients included laboratory tests, such as measurements of tumor markers, at least every 3 months, and dynamic CT or MRI scans, at least every 6 months.

Blood preparation

The blood collection was performed in the early morning after an overnight fast. Clinical records, including AST, ALT, γ-GT, ALP, Alb, T-Bil, Plt, PT, NH3, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (Cre), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and Na, were retrospectively evaluated. The ALBI score31 and fibrosis index based on FIB-432 were calculated. Serum was separated from blood at 1500 g for 10 min and stored at − 80 °C until the measurement of the BA composition.

BA concentrations were determined blindly as described by Ando et al.33 with minor modifications. A mixture of internal standards (ISs) consisting of 41.6 ng of [2H4]CA, 57.5 ng of [2H4]CDCA, 32.8 ng of [2H4] DCA, 22.4 ng of [2H4]LCA, 100 ng of [2H3]TCA, and 20 µl of ethanol–water (9:1, v/v) was added to 20 µl of serum. After the addition of ISs and 2 mL of 0.5 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), BAs were extracted via Bond Elut C18 cartridges (200 mg, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). After washing the cartridge with 1.6 mL of water, BAs were eluted in 3 mL of ethanol–water (9:1, v/v). The eluate was evaporated to dryness at 100 °C under a nitrogen stream and redissolved in 20 mM ammonium acetate buffer (pH 7.5)-methanol (1:1, v/v). After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 1 min, an aliquot of the supernatant was injected into the liquid chromatography‒mass spectrometry (LC‒MS/MS) system for analysis. The LC–MS/MS system consisted of a TSQ Vantage triple stage quadrupole mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with an HESI-II probe and a Prominence ultra-fast liquid chromatography (UFLC) system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Chromatographic separation was performed via a Hypersil GOLD column (150 × 2.1 mm, 3.0 μm; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 40 °C. The mobile phase consisted of (i) 20 mM ammonium acetate buffer (pH 7.5)-acetonitrile-methanol (70:15:15, v/v/v) and (ii) 20 mM ammonium acetate buffer (pH 7.5)-acetonitrile-methanol (30:35:35, v/v/v). The following gradient program was used at a flow rate of 200 μL/min: 0–100% B for 20 min, 100% B for 10 min, and 100% A for 8 min. The linearity and reproducibility of BA analyses in human serum were shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Animal samples 1

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Our animal protocol (HKD43046) was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Hokudo Co., Ltd. (Sapporo, Japan). This rat model of CLD has been previously described in detail34. Briefly, Wister male rats (SRF, CLEA Japan, Tokyo, Japan) aged 7 weeks were fed a solid normal diet, CE2 (CLEA Japan), under conventional conditions and were orally administered carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) at 1.0 mL/kg twice a week for 4 weeks to induce advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis. The CLD state was maintained with two weekly administrations of 0.5 mL/kg CCl4 for 6 weeks (10 weeks total). The analysis included 17 out of 20 rats that died from CCl4 during the experimental period. Ten-week-old male Wistar rats were used as controls, along with three WT rats. All rats were sacrificed at the conclusion of our treatment protocol under anesthesia with isoflurane (DS-pharma, Osaka, Japan). The depth of anesthesia was confirmed by the absence of the pedal withdrawal reflex, followed by euthanasia via exsanguination. Liver and ileum tissues were collected and stored at − 80 °C for the analysis of BA concentrations and BA-related genes. Serum was separated from blood at 1500 g for 10 min and stored at − 80 °C. Serum was used for measurement of AST, ALT, ALB, and T‐Bil at Hokudo Co., Ltd. Serum BAs were measured at CMIC Pharma Science Co., Ltd. and hepatic BAs were measured using commercially available Total Bile Acid Assay kits (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Animal samples 2

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Our animal protocol (HKD10-CAM-01) was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Hokudo Co., Ltd. (Sapporo, Japan). This rat model of CLD has been previously described in detail35. Briefly, Wister male rats (SRF, CLEA Japan, Tokyo, Japan) aged 6 weeks (n = 21) were orally administered 1.0 ml/kg CCl4 twice a week for 5 weeks to establish a rat model of advanced fibrosis. To maintain the cirrhotic state, the rats received 0.5 ml/kg CCl4 orally twice a week for 16 weeks (total of 21 weeks). We divided the rats into a survival group and a deceased group. The survival group included rats that survived for 21 weeks after CCl4 administration, whereas the deceased group included rats that died within 21 weeks of CCl4 administration. The control designation indicates advanced fibrotic rats 5 weeks after CCl4 administration. For the rats that died, we checked their condition every day, sacrificed them under anesthesia with isoflurane just before death. All rats were sacrificed at the conclusion of our treatment protocol under anesthesia with isoflurane. The depth of anesthesia was confirmed by the absence of the pedal withdrawal reflex, followed by euthanasia via exsanguination. Serum was used for measurement of AST, ALT, ALB, and T‐Bil at Hokudo Co., Ltd. Liver tissues were collected and stored at − 80 °C for the analysis of BA concentrations and BA-related genes. Hepatic BAs were measured using commercially available Total Bile Acid Assay kits (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Gene expression

Total RNA was isolated from rectus abdominis muscle using TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized from total RNA via a cDNA synthesis kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan). Real-time PCR quantification was performed using the SYBR Green PCR mixture (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and Quantstudio1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The PCR primers used to amplify each gene are listed in Supplementary Table 2. The mean values of the mRNAs were normalized to those of beta 2 microglobulin (β2 m).

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± SEM or median (minimum‒maximum), and categorical variables are presented as the number of patients. Continuous data were compared between two groups via the Mann‒Whitney U test. The correlation between the serum BA levels and clinical data was examined via Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. The categorical data were compared via the chi-square test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and the corresponding receiver operating characteristic curves (AUCs) were used to obtain cutoff values for the outcomes. The Youden index was applied to calculate the optimal cutoff point. Overall survival was measured via the Kaplan‒Meier method and compared via the log-rank test. Associations between predictor variables and overall survival were determined using Cox proportional hazards regression. All the statistical analyses were performed via SPSS 23.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) or Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, Inc., CA, USA). Differences were considered to be significant at p < 0.05. Along with p values, effect sizes for the Mann‒Whitney U test were calculated and expressed as r. Effect sizes were interpreted as small (0.1 ≤ r < 0.3), medium (0.3 ≤ r < 0.5), and large (r ≥ 0.5).

Data availability

The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions. However, data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of Ethics Committee of Mie University.

References

Tajima, K. et al. Total bile acids levels as a stratification tool for screening portopulmonary hypertension in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Hepatol. Res. Off. J. Jpn. Soc. Hepatol. https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.14059 (2024).

Allen, K., Jaeschke, H. & Copple, B. L. Bile acids induce inflammatory genes in hepatocytes: A novel mechanism of inflammation during obstructive cholestasis. Am. J. Pathol. 178, 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.026 (2011).

Horvatits, T. et al. Serum bile acids as marker for acute decompensation and acute-on-chronic liver failure in patients with non-cholestatic cirrhosis. Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver 37, 224–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13201 (2017).

Delzenne, N. M., Calderon, P. B., Taper, H. S. & Roberfroid, M. B. Comparative hepatotoxicity of cholic acid, deoxycholic acid and lithocholic acid in the rat: In vivo and in vitro studies. Toxicol. Lett. 61, 291–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4274(92)90156-e (1992).

Russell, D. W. The enzymes, regulation, and genetics of bile acid synthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 137–174. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161712 (2003).

Chen, T. et al. Metabolic phenotyping reveals an emerging role of ammonia abnormality in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun. 15, 3796. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47897-y (2024).

Feng, L. et al. Bile acid metabolism dysregulation associates with cancer cachexia: Roles of liver and gut microbiome. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 12, 1553–1569. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12798 (2021).

Xie, G. et al. Conjugated secondary 12alpha-hydroxylated bile acids promote liver fibrogenesis. EBioMedicine 66, 103290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103290 (2021).

Wiese, S. et al. Altered serum bile acid composition is associated with cardiac dysfunction in cirrhosis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 58, 453–462. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.17533 (2023).

Puri, P. et al. The presence and severity of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is associated with specific changes in circulating bile acids. Hepatology 67, 534–548. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29359 (2018).

Brandl, K. et al. Dysregulation of serum bile acids and FGF19 in alcoholic hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 69, 396–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.031 (2018).

Wahlstrom, A. et al. Induction of farnesoid X receptor signaling in germ-free mice colonized with a human microbiota. J. Lipid Res. 58, 412–419. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M072819 (2017).

Xing, L. et al. A dual coverage monitoring of the bile acids profile in the liver-gut axis throughout the whole inflammation-cancer transformation progressive: Reveal hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24054258 (2023).

Sydor, S. et al. Altered microbiota diversity and bile acid signaling in cirrhotic and noncirrhotic NASH-HCC. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 11, e00131. https://doi.org/10.14309/ctg.0000000000000131 (2020).

Petrick, J. L. et al. Prediagnostic concentrations of circulating bile acids and hepatocellular carcinoma risk: REVEAL-HBV and HCV studies. Int. J. Cancer 147, 2743–2753. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.33051 (2020).

Xie, G. et al. Dysregulated bile acid signaling contributes to the neurological impairment in murine models of acute and chronic liver failure. EBioMedicine 37, 294–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.10.030 (2018).

Matye, D. J. et al. Combined ASBT inhibitor and FGF15 treatment improves therapeutic efficacy in experimental nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12, 1001–1019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmgh.2021.04.013 (2021).

Caballero-Camino, F. J. et al. A3907, a systemic ASBT inhibitor, improves cholestasis in mice by multiorgan activity and shows translational relevance to humans. Hepatology 78, 709–726. https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000000376 (2023).

Salhab, A., Amer, J., Lu, Y. & Safadi, R. Sodium(+)/taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide as target therapy for liver fibrosis. Gut 71, 1373–1385. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323345 (2022).

Chen, W. et al. Comprehensive analysis of serum and fecal bile acid profiles and interaction with gut microbiota in primary biliary cholangitis. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 58, 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-019-08731-2 (2020).

Falany, C. N., Johnson, M. R., Barnes, S. & Diasio, R. B. Glycine and taurine conjugation of bile acids by a single enzyme. Molecular cloning and expression of human liver bile acid CoA: Amino acid n-acyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 19375–19379 (1994).

Alrehaili, B. D. et al. Bile acid conjugation deficiency causes hypercholanemia, hyperphagia, islet dysfunction, and gut dysbiosis in mice. Hepatol. Commun. 6, 2765–2780. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep4.2041 (2022).

Rust, C., Bauchmuller, K., Fickert, P., Fuchsbichler, A. & Beuers, U. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent signaling modulates taurochenodeoxycholic acid-induced liver injury and cholestasis in perfused rat livers. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 289, G88-94. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00450.2004 (2005).

Yang, Z. et al. Serum metabolomic profiling identifies key metabolic signatures associated with pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease in humans. Hepatol. Commun. 3, 542–557. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep4.1322 (2019).

Zizalova, K. et al. Serum concentration of taurochenodeoxycholic acid predicts clinically significant portal hypertension. Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver 43, 888–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.15481 (2023).

Feng, S. et al. Bile acids induce liver fibrosis through the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway and the mechanism of FXR inhibition of NLRP3 activation. Hepatol. Int. 18, 1040–1052. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-023-10610-0 (2024).

Ali, R. O. et al. Taurine-conjugated bile acids and their link to hepatic S1PR2 play a significant role in hepatitis C-related liver disease. Hepatol. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1097/HC9.0000000000000478 (2024).

Hirano, F., Haneda, M. & Makino, I. Chenodeoxycholic acid and taurochenodexycholic acid induce anti-apoptotic cIAP-1 expression in human hepatocytes. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21, 1807–1813. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04363.x (2006).

Tamai, Y. et al. Association of lithocholic acid with skeletal muscle hypertrophy through TGR5-IGF-1 and skeletal muscle mass in cultured mouse myotubes, chronic liver disease rats and humans. eLife https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.80638 (2022).

Kokudo, N. et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hepatocellular carcinoma: The Japan society of hepatology 2017 (4th JSH-HCC guidelines) 2019 update. Hepatol. Res. Off. J. Jpn. Soc. Hepatol. 49, 1109–1113. https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.13411 (2019).

Johnson, P. J. et al. Assessment of liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A new evidence-based approach-the ALBI grade. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 33, 550–558. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.57.9151 (2015).

Sterling, R. K. et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology 43, 1317–1325. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.21178 (2006).

Ando, M. et al. High sensitive analysis of rat serum bile acids by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 40, 1179–1186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2005.09.013 (2006).

Tamai, Y. et al. Branched-chain amino acids and l-carnitine attenuate lipotoxic hepatocellular damage in rat cirrhotic liver. Biomed. Pharmacother. 135, 111181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111181 (2021).

Iwasa, M. et al. Branched-chain amino acid supplementation reduces oxidative stress and prolongs survival in rats with advanced liver cirrhosis. PLoS One 8, e70309. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0070309 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the members of the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 22K08011 to MI and AMED under Grant Numbers JP21fk0210090 and JP22fk0210115 to HN.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of study: AE and MI; Acquisition of data: TM, MT, MI, YT, RS, MW; Interpretation of data: YK, AH, MW, TI and HN; Drafting of the manuscript: AE and MI. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

H2019-063.

Informed consent

Opt out.

Human and animal resource

HKD43046

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eguchi, A., Iwasa, M., Miyazaki, T. et al. Conjugated bile acids in serum reflect disease severity and predict survival in chronic liver disease of humans and rats. Sci Rep 15, 32911 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17560-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17560-7