Abstract

Calcium fluoride crystals doped with europium (CaF\(_2\):Eu) have long been used as conventional inorganic scintillators. Their luminescence is primarily attributed to emission from Eu\(^{2+}\) centers, typically around 420 nm. However, it has been reported that increasing the Eu concentration leads to enhanced Eu\(^{3+}\) emission in the wavelength range of 590–700 nm. In this study, CaF\(_2\):Eu crystals with various Eu concentrations (0, 0.3, 1, 2, 3, and 5 mol%) were grown and irradiated with both X-rays and \(\alpha\)-particles from a 241Am source. Radioluminescence spectra were measured for each excitation condition and compared across samples. The results clearly show that the relative contribution of Eu\(^{3+}\) emission is approximately twice as high under \(\alpha\)-particle irradiation compared to X-ray excitation. This enhancement was found to be consistent for Eu concentrations above 1%, and independent of the crystal thickness or geometry. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating that the emission intensity ratio of Eu\(^{2+}\)/Eu\(^{3+}\) centers in CaF\(_2\):Eu scintillators depends on the type of incident radiation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Scintillators, materials capable of converting high-energy radiation into detectable ultraviolet to visible light, play an indispensable role in fundamental research and diverse technological applications. From Rutherford’s seminal alpha-ray scattering experiments employing ZnS scintillators more than a century ago1, scintillation detectors have evolved to become central in modern scientific instrumentation, including medical diagnostics, environmental radiation monitoring, and security systems2,3.

Europium-doped calcium fluoride (CaF\(_2\):Eu) crystals have garnered significant attention due to their chemical stability, excellent optical transparency, and high luminescence yield, emitting approximately 20,000 photons/MeV predominantly around 420 nm—well aligned with photomultiplier tube (PMT) sensitivities4. These crystals exhibit low density (3.18 g/cm\(^3\)), making them particularly suitable for low-energy gamma-ray detection. Their radiopurity and ease of synthesis into large single crystals have positioned them as promising candidates for rare-event searches, such as dark matter detection5 and neutrinoless double-beta decay experiments6. For these rare event searches, pulse shape discrimination (PSD) techniques are generally used to separate the signal from the background7,8,9. However, the application of CaF\(_2\):Eu in these sensitive experiments has been limited by challenges associated with conventional PSD techniques, which show limited efficacy in distinguishing electron from nuclear recoils10,11,12.

To overcome this constraint, we previously introduced an innovative particle discrimination method based on luminescence wavelength rather than waveform analysis, demonstrating its feasibility using Eu-doped LiCaI scintillators13. In the present study, we explore the potential of extending this wavelength-based approach to Eu-doped CaF\(_2\) crystals, examining whether their emission spectra differ in response to the type of incident radiation. Eu-doped CaF\(_2\) hosts both divalent (Eu\(^{2+}\)) and trivalent (Eu\(^{3+}\)) europium ions, each exhibiting distinct luminescence characteristics as evidenced by photoluminescence studies14,15. Both Eu\(^{2+}\) and Eu\(^{3+}\) can substitute Ca\(^{2+}\) sites within the lattice due to their comparable ionic radii (Eu\(^{2+}\): 1.25 Å, Ca\(^{2+}\): 1.12 Å, Eu\(^{3+}\): 1.07 Å). Notably, increasing europium doping levels significantly enhance the prevalence of Eu\(^{3+}\) ions, reducing the proportion of Eu\(^{2+}\) ions, and thereby altering emission intensities and spectral characteristics15,16. The shift in europium ion valence states and their distributions within the crystal matrix are governed by complex defect dynamics, lattice distortions, and charge compensation mechanisms involving interstitial fluoride ions and defect clustering17,18,19,20.

Despite detailed studies on europium valence states and distributions in CaF\(_2\), the dependency of emission characteristics on incident radiation types remains inadequately understood. Here, we systematically investigate the emission behavior of Eu-doped CaF\(_2\) crystals under both X-ray and alpha-ray irradiation across a range of europium concentrations. Our findings reveal radiation-dependent spectral variations, laying the groundwork for a novel luminescence-based particle identification strategy. This approach holds promise to circumvent current PSD limitations, potentially expanding the applicability of CaF\(_2\):Eu scintillators in advanced radiation detection and rare-event experimental physics.

Successful implementation of this luminescence wavelength-based particle discrimination method could significantly impact various scientific and technological domains. In fundamental physics, enhanced particle identification capabilities would improve the sensitivity and reliability of rare-event searches, enabling breakthroughs in understanding dark matter and neutrino properties. Environmental monitoring and homeland security could benefit from enhanced specificity in detecting radioactive contaminants and identifying nuclear materials, respectively. Thus, this novel method could foster advancements across multiple fields reliant on accurate radiation detection and particle identification technologies.

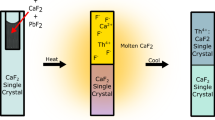

Crystal growth and sample preparation of CaF\(_2\):Eu

For the crystal growth preparation, the initial materials were procured and utilized in powdered form: CaF\(_2\) with a purity of 99% and EuF\(_3\) with a purity of 99%. These substances were combined in a ratio of (Ca\(_{1-x}\)Eu\(_x\))F\(_2\) (x = 0, 0.003, 0.01, 0.02, 0.03, and 0.05) and placed within a carbon crucible. The crucible was then positioned within a radio-frequency (RF) coil and subjected to induction heating, thereby melting the raw materials contained within. The carbon crucible featured a cylindrical shape, with an inner diameter of 26 mm and a height of 87 mm, including a tapered bottom to facilitate the formation of the crystal shoulder. At the base of the crucible, there existed a cylindrical section, approximately 3 mm in diameter and 15 mm in height, designed to accommodate the seed crystal. The growth atmosphere was controlled using CF\(_4\) gas and a high-purity argon gas mixture (CF\(_4\):Ar(G1)=3:7). The molten materials were allowed to mix thoroughly, and after a period of gradual cooling, CaF\(_2\) doped with Eu at atomic concentrations of 0%, 0.3%, 1%, 2%, 3%, and 5% was successfully obtained. The resulting CaF\(_2\) was then processed into the specified shapes as indicated in Table 1, polished to a mirror finish, and subsequently utilized as evaluation samples. Figure 1 presents a photograph of the CaF\(_2\):Eu samples following processing and polishing, under irradiation from a UV lamp.

Photograph of CaF\(_2\):Eu crystal samples grown, processed, and used in this study. Under UV illumination (black light), the characteristic luminescence of Eu is visible. At low Eu concentrations, the crystals emit violet light from Eu\(^{2+}\), while higher Eu concentrations result in dominant red emission from Eu\(^{3+}\).

Radio luminescence and transparency measurement

The spectrometer employed for radioluminescence measurements under X-ray and alpha-ray irradiation was assembled by integrating an ANDOR Shamrock163 Czerny-Turner type spectrometer with an ANDOR iDus420 scientific-grade CCD camera (Oxford Instruments, Oxfordshire, England). The grating utilized was ANDOR SR1-GRT-0150-0300 (Oxford Instruments, Oxfordshire, England), and the slit employed was ANDOR SR1-SLT-0200-3 (Oxford Instruments, Oxfordshire, England). The resolution of the spectrometer was \(\sim\)7 nm. For X-ray-excited radioluminescence measurements, the irradiation conditions were set at 40 kV and 30 mA, utilizing a tungsten target. For alpha-ray-induced radioluminescence measurements, a sealed \(^{241}\)Am source with an activity of 3 MBq was used. The radioluminescence emission from the CaF\(_2\):Eu samples was detected from the side opposite to the surface irradiated by the radiation source, using an optical fiber. The optical fiber was connected to the Shamrock163 spectrometer. The radioluminescence emission was spectroscopically analyzed by the Shamrock163, transmitted to the iDus420 CCD camera, and recorded as a wavelength spectrum on a PC.

Figure 2 illustrates the radioluminescence spectra obtained by irradiating each CaF\(_2\):Eu sample with X-rays and alpha rays, presented separately for each sample. The radioluminescence spectra are normalized and displayed relative to their maximum intensity values. The absolute light yield dependence on Eu concentration is also an interesting subject; however, because the crystals used in this study had different sizes and geometries, the light collection efficiency into the spectrometer fiber varied, making such an evaluation difficult with the current setup. We consider this an important issue and plan to investigate it in future work. In the \(\alpha\)-ray spectra (red curves), the apparent increase in noise with higher Eu concentration can be attributed to the reduced light yield of Eu\(^{2+}\), which makes the noise appear more significant in relative terms. Additionally, the transmittance for each sample are provided.

In the CaF\(_2\) sample without Eu doping, the radioluminescence emission intensity is minimal, leading to data with significant noise. Nevertheless, a broad emission band centered around 280 nm was observed, in agreement with previous reports. In the CaF\(_2\) samples doped with Eu, two distinct emissions were identified. The first is due to the 5d-4f transition of Eu\(^{2+}\), with an emission peak around 424 nm. The second is attributed to the 4f-4f transition of Eu\(^{3+}\), exhibiting emission peaks at 590, 613, 650, and 695 nm, corresponding to the 5D\(_0 \rightarrow\) 7F\(_J\) (J = 1, 2, 3, and 4) transitions21. As noted in prior studies15,22, altering the Eu concentration leads to a shift in the intensity ratio between the Eu\(^{2+}\) and Eu\(^{3+}\) emissions in the CaF\(_2\) luminescence. Specifically, an increase in Eu concentration resulted in a higher ratio of radioluminescence from Eu\(^{3+}\) transitions relative to that from Eu\(^{2+}\) transitions.

When comparing the radioluminescence induced by X-ray and alpha-ray excitation within the same sample, it is evident that the ratio of emission intensities for Eu\(^{2+}\) and Eu\(^{3+}\) differs significantly. For example, in the radioluminescence spectrum of Eu 3%, the intensity of Eu\(^{2+}\) luminescence (broad emission at 424 nm) remains relatively constant, whereas the intensity of Eu\(^{3+}\) luminescence (sharp emissions around 593 nm, 613 nm, 650 nm, and 695 nm) is approximately twice as high under alpha-ray excitation compared to X-ray excitation.

While the underlying mechanism responsible for the observed difference in Eu\(^{3+}\)/Eu\(^{2+}\) emission ratios is not yet fully understood, differences in ionization density between X-rays and alpha particles could be a key to understand the difference of Eu\(^{3+}\)/Eu\(^{2+}\) emission. However, the precise processes governing this effect remain unclear. Further systematic studies will be required to clarify the mechanism, including measurements with radiation sources of varying energy loss per unit length (dE/dX), as well as complementary investigations of scintillation properties such as time constants and light yield ratios. These future efforts are expected to provide a deeper understanding of how radiation–matter interactions shape the emission characteristics of Eu-doped CaF\(_2\).

It should be noted that the Eu\(^{3+}\)/Eu\(^{2+}\) ratio may also be affected by temperature. The measurements were carried out under room-temperature conditions stabilized by an air conditioner. However, the crystal temperature itself was neither directly measured nor actively controlled.

Color CMOS camera measurement

To verify the results obtained from the radioluminescence measurements described above, we conducted an independent measurement using a color Complementary Metal Oxide Semiconductor (CMOS) camera (CS-67C, Bitran Co., Ltd.). The wavelength sensitivity of the red, green, and blue (RGB) pixels of the camera is shown in the right panel of Fig. 3. For reference, the black dotted line indicates the radioluminescence spectrum of a CaF\(_2\) crystal doped with 3% Eu under \(\alpha\)-particle irradiation. The Eu\(^{2+}\) emission around 420 nm is primarily detected by the blue pixels, while the Eu\(^{3+}\) emission in the 590–700 nm range is effectively captured by the red pixels. For this measurement, we selected a CaF\(_2\) crystal doped with 3% Eu, which had shown a significant difference in emission characteristics between \(\alpha\)- and X-ray irradiation in the radioluminescence measurements. The crystal was optically coupled to the cover glass of the camera using optical grease (TSK5353), and a stainless-steel collimator and radiation source were placed on top of it. A schematic of the experimental setup is shown in the left panel of Fig. 3. We used \(^{241}\)Am as an \(\alpha\)-particle source and \(^{90}\)Sr as a \(\beta\)-particle source. Due to the experimental setup, a strong \(\gamma\)-ray or X-ray source could not be placed above the CMOS camera; \(\beta\)-particle source was used instead, as their electrons directly excite surrounding atoms similarly to the secondary electrons generated by X-rays, making \(\beta\)-rays a suitable substitute.

The camera exposure time was set to 600 s for each measurement. Figure 4 shows the distribution of pixel output counts for each RGB channel; the histogram colors correspond to the respective pixel types. In the absence of any radiation source, the output distributions of the RGB pixels were nearly identical. When irradiated with \(\alpha\)-particles from \(^{241}\)Am, the red pixel output increased noticeably. In contrast, under \(\beta\)-ray irradiation from \(^{90}\)Sr, the blue pixels exhibited relatively higher output levels compared to the other channels. These results are consistent with the radioluminescence measurements, in which \(\alpha\)-irradiation enhanced the red emission from Eu\(^{3+}\).

Overall, the CMOS camera measurements support the radioluminescence findings and confirm that the intensity ratio between Eu\(^{2+}\) and Eu\(^{3+}\) emissions depends on the type of incident radiation (\(\alpha\) or \(\beta\)).

In the future, we plan to combine this setup with a lens-based optical system to enable event-by-event color imaging of radiation tracks. If successful, it would be possible to distinguish the type of incident particle—such as \(\alpha\) particles or X-rays—based on the color of the recorded track. This approach could serve as the foundation for a novel radiation detection technique. Monochromatic imaging of radiation tracks has already been demonstrated 23, and color track imaging is not beyond the realm of possibility. However, the light yield of CaF\(_2\):Eu crystals is lower than that of Ce:Gd\(_3\)Ga\(_3\)Al\(_2\)O\(_{12}\) used in previous work 23, resulting in \(\alpha\)-particle tracks being buried in the noise of the current CMOS camera.

While the radioluminescence spectra are derived from the integration of a large number of events, leading to small statistical uncertainties, the CMOS camera measurements aim to capture single-event tracks, where the signal is much more susceptible to noise. Going forward, we aim to reduce the noise level of the detection system and achieve event-by-event color imaging of radiation tracks.

Discussion

An important consideration is that absorption within the scintillator may influence the shape of the emission spectrum. In this study, the luminescence from the samples was detected from the surface opposite to the one irradiated by the radiation source. Since X-rays and \(\alpha\)-particles have different penetration depths in the CaF\(_2\) samples, the distances that the emitted photons must travel through the crystal before reaching the optical fiber also differ. Consequently, the extent of absorption of the luminescence can vary depending on the type of incident radiation. In particular, the Eu\(^{2+}\) emission in the shorter-wavelength region may undergo self-absorption, which could lead to modifications in the observed spectra.

Figure 2 presents the transmittance of each sample, with CaF\(_2\):Eu exhibiting absorption below 400 nm. In this scenario, alpha rays are absorbed at the surface of the CaF\(_2\) sample, while X-rays penetrate deeper into the material. As a result, alpha rays traverse a greater distance through the crystal before reaching the optical fiber, resulting in more significant absorption of shorter-wavelength emissions.

To assess the effect of self-absorption, we calculated the attenuation depth of X-rays into the CaF\(_2\) sample. Figure 5 (left) illustrates the calculated attenuation length of X-rays as a function of X-ray energy using the WEB site of The Center for X-Ray Optics, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory24. The range of alpha particles in CaF\(_2\) is \(\sim\)20 \(\mu\)m, while the attenuation length in CaF\(_2\) corresponding to the mean energy of continuous X-rays generated at a tube voltage of 40 kV is estimated to be \(\sim\)400 \(\mu\)m. Considering the sample thickness of 5 mm, the impact of self-absorption within the sample is regarded as minimal.

We experimentally confirmed that the effect of crystal thickness on the radioluminescence spectrum is negligible. To verify this, a new CaF\(_2\):Eu crystal with 3% Eu doping was grown independently of those used in the main radioluminescence measurements. Two samples with different thicknesses (1 mm and 5 mm) were then prepared from this single crystal. Both samples were irradiated with \(\alpha\)-particles from a \(^{241}\)Am source, and their radioluminescence spectra were measured. As shown in Fig. 6 (right), the two spectra were nearly identical. These findings indicate that sample thickness—and consequently, internal absorption within the crystal—exerts minimal influence on the radioluminescence spectrum of CaF\(_2\):Eu. Furthermore, the results clearly demonstrate that differences in attenuation lengths between alpha particles and X-rays have a negligible impact on the Eu\(^{2+}\)/Eu\(^{3+}\) intensity ratio in the radioluminescence spectra.

(Left) Calculated penetration depth of X-rays in CaF\(_2\) as a function of energy24. (Right) Radioluminescence spectra of 3% Eu-doped CaF\(_2\) crystals with different thicknesses. The red and blue curves correspond to crystals with 1 mm and 5 mm thickness, respectively.

Based on the radioluminescence measurements, it was demonstrated that the emission intensity ratio of Eu\(^{3+}\)/Eu\(^{2+}\) differs depending on whether the excitation source is X-rays or \(\alpha\)-particles. Here, we further investigate the relationship between the Eu\(^{3+}\)/Eu\(^{2+}\) emission ratio and the europium concentration in the crystal.

Figure 6 (left) shows the area ratio of Eu\(^{3+}\) to Eu\(^{2+}\) emission components obtained from the radioluminescence spectra as a function of Eu concentration (0–5%). The emission areas were integrated over the wavelength ranges of 400–500 nm for Eu\(^{2+}\) and 550–750 nm for Eu\(^{3+}\). Red and blue markers represent data obtained under \(\alpha\)-particle and X-ray irradiation, respectively. The inset in the upper left corner zooms in on the lower concentration range (0.2–2%). It can be observed that, for both \(\alpha\)-particles and X-rays, the relative intensity of Eu\(^{3+}\) emission increases with increasing Eu concentration.

To quantitatively assess the extent of difference between \(\alpha\) and X-ray excitations, we calculated the ratio of the Eu\(^{3+}\)/Eu\(^{2+}\) value obtained under \(\alpha\)-particle irradiation to that obtained under X-ray irradiation for each Eu concentration. This corresponds to the point-wise division of the red and blue markers in Fig. 6 (left), and the result is plotted on the vertical axis of Fig. 6 (right). Note that the Eu concentration of 0% is excluded here, as the overall light yield was extremely low and significantly affected by noise. A larger value in this plot indicates a more pronounced difference in the Eu\(^{3+}\)/Eu\(^{2+}\) emission ratio between the two types of radiation.

The result shows that the maximum value appears at an Eu concentration of 0.3%. In the spectrum of Eu 0.3%, the Eu\(^{3+}\) peak is much smaller than the Eu\(^{2+}\) peak, and the baseline shows a slight difference between the red and blue spectra. Such small baseline variations could lead to apparent differences in the Eu\(^{3+}\)/Eu\(^{2+}\) ratio when summing very low-intensity peaks. Furthermore, for crystals with Eu concentrations above 1%, the ratio remains relatively constant, indicating that the difference in Eu\(^{3+}\)/Eu\(^{2+}\) ratio between X-rays and \(\alpha\)-particles is not significantly affected by Eu concentration or crystal geometry, including thickness. The statistical error is estimated to be about 1.6% for the weakest signal, namely the Eu\(^{3+}\) emission of the 0.3% Eu-doped crystal under X-ray irradiation. Since all other measurements correspond to larger photon yields, the statistical accuracy of the spectra presented here is considered sufficient.

(Left) Dependence of the Eu\(^{3+}\)/Eu\(^{2+}\) emission ratio on Eu concentration, obtained from radioluminescence measurements. Red and blue points represent data under \(\alpha\)-particle and X-ray irradiation, respectively. (Right) Ratio of the Eu\(^{3+}\)/Eu\(^{2+}\) emission intensity under \(\alpha\)-irradiation to that under X-ray irradiation, plotted as a function of Eu concentration. The ratio remains nearly constant for Eu concentrations above 1%.

A quantitative estimation of this particle identification methods will be an important subject for future work. Nevertheless, as an illustrative estimation, we considered the discrimination capability between \(\alpha\) and \(\gamma\) rays based on the observed Eu\(^{3+}\)/Eu\(^{2+}\) emission ratios. Suppose we employ a CaF\(_2\):Eu (3%) crystal with a light yield of approximately 10,000 photons/MeV, together with photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) coupled to optical filters that separate the Eu\(^{2+}\) and Eu\(^{3+}\) emissions. Under irradiation with a 662 keV gamma ray, the crystal would produce about 6620 photons. Assuming a photon detection efficiency of 20% for the PMTs and a 50% transmission loss from the optical filters, roughly 662 photoelectrons would be detected in total. From the radioluminescence spectra, the Eu\(^{3+}\)/Eu\(^{2+}\) intensity ratios are estimated to be 0.72 for alpha irradiation and 0.32 for \(\gamma\) irradiation. This corresponds to photoelectron distributions of (Eu\(^{2+}\), Eu\(^{3+}\)) = (385, 277) for \(\alpha\) rays and (502, 160) for \(\gamma\) rays. Considering the millisecond-scale decay constant of Eu\(^{3+}\) emission, a 10 ms integration gate was assumed. With a PMT dark count rate of 5 kHz, approximately 50 noise counts would be added to each PMT. Under these conditions, the effective Eu\(^{3+}\)/Eu\(^{2+}\) ratios become 0.75 ± 0.06 for \(\alpha\) rays and 0.38 ± 0.04 for \(\gamma\) rays. The statistical separation significance is calculated as about 5\(\sigma\), suggesting that efficient detection of Eu\(^{2+}\) and Eu\(^{3+}\) components could enable high discrimination capability. However, in order to detect Eu\(^{3+}\) luminescence, a light sensor sensitive to long wavelengths, such as a multi-alkali PMT, is required. Although this estimation involves several assumptions, it highlights the potential of spectral discrimination in Eu-doped CaF\(_2\) as a promising method for particle identification.

Here, it should be also noted that this difference in the Eu\(^{2+}\)/Eu\(^{3+}\) ratio is expected to affect not only the emission wavelength but also the scintillation decay constants. The decay constant of Eu\(^{2+}\) is approximately 1 \(\mu\) s, while that of Eu\(^{3+}\) is on the order of several milliseconds. The difference in time constants may also be applicable to particle identification in the future.

Conclusion and prospect

We investigated the radiation-induced luminescence behavior of Eu-doped CaF\(_2\) crystals with various Eu concentrations. Radioluminescence measurements under X-rays and \(\alpha\)-particles revealed that \(\alpha\)-irradiation significantly enhances Eu\(^{3+}\) emission relative to Eu\(^{2+}\). This Eu\(^{3+}\)/Eu\(^{2+}\) intensity ratio was nearly independent of Eu concentration (above 1%), as well as crystal thickness and geometry. Complementary color CMOS imaging confirmed that \(\alpha\)- and \(\beta\)-particles produce distinct spectral signatures, consistent with enhanced red emission from Eu\(^{3+}\) under \(\alpha\) excitation.

To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating that the Eu\(^{3+}\)/Eu\(^{2+}\) emission ratio can serve as a spectral marker for the type of incident radiation. This finding may provide a useful approach for radiation discrimination based on emission characteristics in a scintillation detector.

Such a technique may be especially valuable for spatially resolved dose measurements in complex environments, such as nuclear decommissioning sites. However, event-level color imaging remains technically challenging due to the modest light yield of CaF\(_2\):Eu. Cooling-based noise suppression or alternative high-yield materials may be required. However, finding new materials suitable for this study is not straightforward, and so far no other materials exhibiting a different Eu\(^{3+}\)/Eu\(^{2+}\) emission ratio have been identified.

Further studies with heavy-ion beams covering a wide range of dE/dX values, along with analysis of scintillation waveforms and \(\alpha /\beta\) light yield ratios, will be key to deepening our understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

Our results pave the way toward advanced, spectrally selective radiation detection technologies and improved insight into the luminescence physics of Eu-doped scintillators.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request

References

Geiger, H. On the scattering of the \(\alpha\)-particles by matter. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. A 81, 174–177. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1908.0067 (1908).

Nikl, M. Scintillation detectors for x-rays. Measur. Sci. Technol. 17, R37–R54. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-0233/17/4/R01 (2006).

Lecoq, P. Development of new scintillators for medical applications. Nuclear Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 809, 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2015.09.093 (2016).

Katagiri, H. et al. Development of an omnidirectional compton camera using caf2(eu) scintillators to visualize gamma rays with energy below 250 kev for radioactive environmental monitoring in nuclear medicine facilities. Nuclear Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accelerators Pectrometers Detectors Associated Equip. 996, 165133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2021.165133 (2021).

Shimizu, Y., Minowa, M., Suganuma, W. & Inoue, Y. Dark matter search experiment with caf2(eu) scintillator at kamioka observatory. Phys. Lett. B 633, 195–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2005.12.025 (2006) (astro-ph/0510390).

Umehara, S. et al. Neutrino-less double-beta decay of Ca-48 studied by Ca F(2)(Eu) scintillators. Phys. Rev. C 78, 058501. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.78.058501 (2008) (0810.4746).

Tamagawa, Y., Inukai, Y., Ogawa, I. & Kobayashi, M. Alpha-gamma pulse-shape discrimination in Gd3Al2Ga3O12 (GAGG):Ce3+ crystal scintillator using shape indicator. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 795, 192–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2015.05.052 (2015).

Mizukoshi, K. et al. Pulse-shape discrimination potential of new scintillator material: La-GPS:ce. J. Instrum. 14, P06037. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/14/06/P06037 (2019).

Yoshino, M. et al. Comparative pulse shape discrimination study for ca(br, I)2 scintillators using machine learning and conventional methods. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 1045, 167626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2022.167626 (2023).

Belli, P. et al. Search for alpha decay of natural europium. Nuclear Phys. A 789, 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2007.03.001 (2007).

Oguri, S., Inoue, Y. & Minowa, M. Pulse-shape discrimination of \(CaF_2(Eu)\). Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 622, 588–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2010.07.055 (2010) (1007.4750).

Tovey, D. et al. Measurement of scintillation efficiencies and pulse-shapes for nuclear recoils in nai(tl) and caf2(eu) at low energies for dark matter experiments. Phys. Lett. B 433, 150–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0370-2693(98)00643-1 (1998).

Iida, T., Yoshino, M., Kamada, K., Sasaki, R. & Yajima, R. Gamma and neutron separation using emission wavelengths in Eu:LiCaI scintillators. PTEP 2023, 023H01, https://doi.org/10.1093/ptep/ptad003 (2023). 2209.13189.

Barbin, V., Jouart, J. P. & Dalmeida, T. Cathodoluminescence and laser-excited luminescence spectroscopy of Eu3+ and Eu2+ in synthetic CaF2: a comparative study. Chem. Geol. 130(1–2), 77–86 (1996).

Yu, H. et al. Color-tunable visible photoluminescence of eu:CaF\(_{2}\) single crystals: variations of valence state and local lattice environment of eu ions. Opt. Express 27, 523–532. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.27.000523 (2019).

Cantelar, E., Sanz-García, J. A., Sanz-Martín, A., Muñoz Santiuste, J. E. & Cussó, F. Structural, photoluminescent properties and judd-ofelt analysis of Eu3+-activated CaF2 nanocubes. J. Alloys Compd. 813, 152194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.152194 (2020).

Cortelletti, P. et al. Luminescence of Eu\(^{3+}\) activated CaF\(_{2}\) and SrF\(_{2}\) nanoparticles: Effect of the particle size and codoping with alkaline ions. Cryst. Growth Des. 18, 686–694. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.7b01050 (2018).

Ito, H. et al. Optical evaluation of divalent and trivalent eu ions doped in CaF 2 crystals using multiphoton luminescence 3D distribution measurements. Phys. Status Solidi B Basic Res. 257, 1900477. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssb.201900477 (2020).

Hamers, R. J., Wietfeldt, J. R. & Wright, J. C. Defect chemistry in CaF2:Eu3+. J. Chem. Phys. 77, 683–692. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.443882 (1982).

Cirillo-Penn, K. M. & Wright, J. C. Identification of defect structures in Eu3+:CaF2 by site selective spectroscopy of relaxation dynamics. J. Lumin. 48–49, 505–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2313(91)90180-4 (1991).

Abdallah, R. A. A., Kroon, R. E., Coetsee, E., Hasabeldaim, E. H. H. & Swart, H. C. Stability investigation of Eu3+ doped CaF2 thin film with ZnO coating under electron beam irradiation. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 42, 033203. https://doi.org/10.1116/6.0003363 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. A neoteric approach to achieve CaF2:Eu2+/3+ one-dimensional nanostructures with direct white light emission and color-tuned photoluminescence. J. Alloys Compd. 851, 156784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.156784 (2021).

Yamamoto, S. et al. Development of an ultrahigh resolution real time alpha particle imaging system for observing the trajectories of alpha particles in a scintillator. Sci. Rep. 13, 4955. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31748-9 (2023).

Gullikson, E. X-ray attenuation length (2023). https://henke.lbl.gov/optical_constants/atten2.html.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Dr. Masanori Koshimizu of Shizuoka University and Dr. Shohei Kodama of Saitama University for their insightful discussions on the interpretation of the results obtained.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI grants (grant numbers JP23K17685 and JP25K22021), as well as by the Konica Minolta Science and Technology Foundation. The funders played no part in designing the study, conducting the experiment, analysing the results or writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.I. conceived the study. T.I. and M.Y. designed the methodology and performed the experiments. K.K. and K.J.K. provided the crystal samples. T.I. carried out the data analysis. T.I. and M.Y. wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iida, T., Yoshino, M., Kim, K.J. et al. Emission characteristics of Eu\(^{2+}\) and Eu\(^{3+}\) under x-ray and alpha irradiation in Eu-doped CaF\(_2\) crystals. Sci Rep 15, 32251 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17570-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17570-5