Abstract

Cloud systems supply different kinds of on-demand services in accordance with client needs. As the landscape of cloud computing undergoes continuous development, there is a growing imperative for effective utilization of resources, task scheduling, and fault tolerance mechanisms. To decrease the user task execution time (shorten the makespan) with reduced operational expenses, to improve the distribution of load, and to boost utilization of resources, proper mapping of user tasks to the available VMs is necessary. This study introduces a unique perspective in tackling these challenges by implementing inventive scheduling strategies along with robust and proactive fault tolerance mechanisms in cloud environments. This paper presents the Clustering and Reservation Fault-tolerant Scheduling (CRFTS), which adapts the heartbeat mechanism to detect failed VMs proactively and maximizes the system reliability while making it fault-tolerant and optimizing other Quality of Service (QoS) parameters, such as makespan, average resource utilization, and reliability. The study optimizes the allocation of tasks to improve resource utilization and reduce the time required for their completion. At the same time, the proactive reservation-based fault tolerance framework is presented to ensure continuous service delivery throughout its execution without any interruption. The effectiveness of the suggested model is illustrated through simulations and empirical analyses, highlighting enhancements in several QoS parameters while comparing with HEFT, FTSA-1, DBSA, E-HEFT, LB-HEFT, BDHEFT, HO-SSA, and MOTSWAO for various cases and conditions across different tasks and VMs. The outcomes demonstrate that CRFTS average progresses about 48.7%, 51.2%, 45.4%, 11.8%, 24.5%, 24.4% in terms of makespan and 13.1%, 9.3%, 6.5%, 21%, 22.1%, 26.3% in terms of average resource utilization compared to HEFT, FTSA-1, DBSA, E-HEFT, LB-HEFT, BDHEFT, HO-SSA, and MOTSWAO, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The cloud is a virtual internet-based worldwide distribution of massive applications and computer resources, including memory, network, and processor. On a “pay as you go” basis, these distributed applications and resources are made available globally and shared with the users. As a request-response model, the cloud environment helps clients make requests for the many services and provide responses as needed. A well-designed network connects the underlying cloud infrastructure dispersed over a large geographic site to create a cloud environment. User requests are fulfilled using the combined power of all the dispersed VMs. The phenomena of VM allocation are dynamic and adaptable in the cloud environment. And there must be a clever scheduling system that expertly maps each job to the VM to meet the demands of the user. Additionally, several cloud-related elements must be considered to offer prompt and assured services. These elements are built on fault tolerance, scalability, availability, and security. The quality of equipping the cloud services to the users is ensured by SLA (Service Level Agreement). But in a cloud context, QoS also plays a big part1.

Since the cloud is a dynamic environment, any number of clients may request the services. As a result, cloud service providers must be able to fulfil the client’s demands on time. Appropriate scheduling techniques may do this by positioning the client requests on the suitable VMs. System performance can be improved if the workload is distributed across the computer nodes in accordance with their processing capabilities2. Moreover, the service providers must also ensure reliable services. This can be done by providing the successful execution of the tasks in a timely manner. However, the dynamic nature of the cloud makes it more prone to faults, which may lead to the illegal termination of the execution of the task. This can be handled by making the cloud fault-tolerant so that the affected task will be migrated to an alternative VM to continue execution3. For finding a suitable and effective sequence of task execution, the cloud scheduler should be responsible for performing the following main key functions:

-

Creating an effective and appropriate schedule for VM allocation for the arriving tasks.

-

Stopping the tasks from being terminated too soon. This can be done by including any of the efficient fault tolerance mechanisms and making the scheduling more efficient and fault-proof.

-

Effective and skilful migration.

Besides, the notion of Advance Reservation (AR), which has several benefits, is stable and established for reserving VM4. Since applications are often implemented on VMs, these machines may be simply moved or relocated anywhere to free up enough VMs for task execution5 using some of the migration techniques. However, the scheduler lacks precise knowledge of the task size and execution time in a dynamic system. Additionally, in a distributed environment like the cloud, the VM failure can cause the system to malfunction at any moment, and there may be multiple other reasons for the same. This is the reason that once the task is assigned to any VM, it might be terminated too soon without completing its execution6,7,8. If any VM switches its status from active to inactive or offline without being informed, a fault may arise unexpectedly. Furthermore, there are two sorts of faults: permanent faults and transitory faults. Until the defective VM is repaired, permanent faults persist in the environment. On the other hand, once transient faults enter the system, they cannot be accessed. Alternate VMs must be allocated to the tasks to manage this fault condition if one or more of the VMs fail to render the environment fault-tolerant9. Fault tolerance can be achieved by different techniques such as replication, re-submission, and recovery.

The proposed CRFTS involves a novel VM allocation strategy, i.e., a clustered allocation strategy. It initially sorts the tasks and VMs and then divides both tasks and VMs into three clusters, namely: low, mid, and high clusters. This clustering makes the allocation more efficient by narrowing the domain of mapping and allocating each task to the most suitable VM. The clustering restricts the domain of both tasks and VMs and thereby prevents the task from getting mapped with the VM, which is not appropriate. Furthermore, the proposed model is enforced with an effective fault-tolerant algorithm based on the prior reservation of VMs. The proposed model estimates the AR slot for the tasks and reserves the VM for tasks to guarantee task completion. The alternative VM is selected based on the previous load of the VM and the clustering approach. While evaluating the model, CRFTS was evaluated based on parameters like reliability, makespan, and average resource utilization by varying the number of tasks and the number of VMs.

Motivation and contribution

Some of the recent related fault-tolerant models like HEFT (Heterogeneous Earliest Finish Time), FTSA-1 (Fault Tolerant Scheduling Algorithm), and DBSA (Deadline Based Scheduling Algorithm) were proposed in10,11,12, respectively, and undoubtedly made noteworthy contributions. However, it is imperative to acknowledge their inherent limitations, creating a compelling need for targeted interventions to propel the field toward further advancements. Among all these proposed approaches, the reliability of DBSA was seen to be the most efficient. An innovative hybrid checkpointing and rollback recovery mechanism is also stated by the author in13. In addition, the author claims that the main requirement of today’s dispersed environment is the optimized utilization of resources. In contrast, the current fault-tolerant methods compromise makespan, which eventually results in increased task execution time. Moreover, the diverged environment raises the challenging concern regarding the total reliability of the system while effectively addressing the fault situations. In specific existing fault-tolerant approaches, inefficiencies in resource utilization may arise, resulting in performance degradation and increased resource utilization. This constraint holds particular significance in cloud environments, where the imperative of efficient resource allocation is fundamental in achieving high resource utilization and maintaining optimal service delivery. The cloud may undoubtedly introduce divergent fault scenarios because of its dynamic nature and support of diverse applications. Addressing them becomes a principal requirement for ensuring a seamless and reliable user experience and thereby meeting service level expectations. After studying the existing literature presented in Sect. 2, it was noted that the work on some scheduling parameters, like makespan and average utilization of the resources, can be addressed further. Here, we propose the novel fault-tolerant scheduling model, CRFTS, that uses clustering-based allocation and reservation-based fault tolerance. We compare CRFTS with HEFT, FTSA-1, DBSA, E-HEFT (Enhancement of Heterogeneous Earliest Finish Time)14, LB-HEFT (Load balancing- Heterogeneous Earliest Finish Time)15, BDHEFT, HO-SSA, and MOTSWAO, and were evaluated for makespan, average resource utilization, and reliability.

The outcomes demonstrate that CRFTS outperforms the compared state-of-the-art. Some of the enhancements of the contributed work are listed below:

-

Progress in Cloud Reliability.

-

Novel Task Scheduling.

-

Reduction of Service Interruptions and makespan.

-

Efficient Utilisation of Resources.

-

Fault-administration.

-

Scalable and Adaptable Fault Handling.

Additionally, the primary contributions of this paper can be encapsulated in the following manner:

-

To find ideal and optimized task scheduling of user tasks on the accessible VMs, we first introduce the problem of mapping between tasks and VMs.

-

Secondly, to handle dynamically failed or affected tasks, we adapt a proactive heartbeat mechanism and a reservation-based fault tolerance, and migrate the affected task to a healthy VM.

-

To address the two identified challenges, we introduce the CRFTS approach, incorporating two methodologies. Initially, it utilizes the clustered technique for scheduling, and subsequently, for managing faults, the model incorporates the reservation technique.

-

We establish a system model to assess the effectiveness and efficacy of the proposed CRFTS approach by conducting comparisons with five other related approaches. The evaluation considered parameters such as reliability, makespan, and average resource utilization during the execution of a set of parallel applications on varying tasks and VM heterogeneity.

Organization of the paper

The rest of the manuscript is structured as follows: Sect. 2 is Related Literature that discusses pertinent research that has been proposed so far. The system architecture for the proposed CRFTS is discussed under the title “Proposed Work” in Sect. 3, which also includes the system model and problem formulation with pseudocode and algorithm. Performance metrics and a flowchart of the model have also been presented in Sect. 3. Section 3 also computes the computational complexity of the CRFTS. Additionally, Sect. 4 presents the Results and Observations, and finally, Sect. 5 concludes the work. Apart from this, Table 1 presents the comparative analysis that relates the proposed model to the current state of the art.

Related literature

The dynamic nature of the VMs in the cloud makes them unstable and fault-prone, which might lead to premature job termination. Any VM that fails or abruptly leaves the system without any prior notice might cause this instability. Furthermore, fault tolerance ensures the promised services are delivered on time even when system flaws or errors are reported. However, the suggested fault-tolerant approaches considered VM efficiency and reliability under typical circumstances. One method to make the cloud fault-proof is the advance reservation strategy in which we tie the virtual machine to a specific job for a predetermined amount of time. Following an examination of the literature, it was discovered that advance reservation has been used for a variety of task categories under various settings for static, dynamic, and distributed systems. However, the proposed fault-tolerant approaches considered VM efficiency and reliability under typical circumstances. This is how the relevant literature review is laid out.

Additionally, for a variety of task categories, including a batch of activities, priority-based tasks, autonomous tasks, and workflow applications, AR has been used in the literature. The live migration framework for numerous VMs with modified resource reservation mechanisms is detailed in16. The impact of modified resource reservation techniques on live migration in both the source machine and target machine was then investigated via a series of experiments. Besides, the effectiveness of the workload-aware and parallel migration techniques was examined. The PTAL approach was proposed in17 for effective job distribution and resource reallocation to get improved QoS outcomes. The dynamic task scheduling (DTS) algorithm is proposed in18 for minimizing makespan, which considers several task requests coming from various users dynamically. Multiple gridlets have been distributed to several resources in the DTS strategy in a highly parallel and dynamic way, with each resource having a specific number of tasks to complete. To examine several methods for creating and sustaining an energy-efficient cloud, a review has been carried out23. The review compares the QoS Metrics in cloud computing using graphs. Additionally, in19, traditional “on-demand provisioning” was combined with an elastic reserve strategy. As a result of this feature, resource effectiveness utilization (REU) and customer satisfaction will be increased by allowing cloud providers to accept over-reservation requests under specific circumstances. Later, in20, energy efficiency was considered while arranging VM reservations in cloud data centres. The goal is to non-pre-emptively schedule all reservations while considering the capacity of PMs and running time interval spans to reduce the overall energy consumption of all PMs, also known as MinTEC (Minimum Total Energy Consumption). The FTHRM, which was based on a prior reservation strategy, was proposed in21, with the primary emphasis being on turnaround time, and the model is entirely based on grid computing. Furthermore, in24, the author provides a generic model for allocating resources to a batch of computational tasks that must be completed on time. The author also suggested an online scheduling strategy that improves resource usage, flowtime, and tardiness while minimizing the adverse effects of the AR approach on the schedule’s quality. Additionally, this study investigated a static system model that was incapable of handling the dynamic behaviour of the resources25. The resources can only be made available for a set time following negotiation in a static setting. Initially, a Grid-sim Simulator was used to develop AR26. A similar concept was introduced by the author later in27 for scheduling jobs, ENARA with AR requests, as well as a batch of computing activities was developed. In some work on energy-efficient reliability scheduling28, focuses on precedence-constrained jobs with individual deadlines. But they did not consider communication time. Priority tasks were the subject of a fault-tolerance analysis by29 that can withstand several irreversible failures. But they did not take time constraints and reliability into account. The secure grid architecture model was built using the artificial neural network (ANN) proposed in30. To get beyond any restrictions brought on by resource failure, the proposed module offers a secure task for resource mapping. In this chain, the author assessed the performance of each kind of grid that the grid infrastructure could support. The installation of both problematic and secure scheduling modes is taken into consideration. A few further works have recently been mentioned in the literature. To execute the task efficiently and safely, the author of31 presented a hyper-heuristic strategy for resource appointments utilizing particle swarm optimization. Moreover, to provide different scheduling and fault-tolerance approaches, a survey was carried out32. In33, the author illustrates how fault tolerance is achieved through data representation and shows how regularising the vectors reduces the likelihood of fatal errors. The GMRES iterative solution in this study resolves observed failure. The resource K-means clustering approach was incorporated with the GA algorithm in22 for IoT allocation, offering a minimum error rate. In34, the authors provide an exhaustive overview by classifying resource management concerns and obstacles in the Fog/Edge paradigm into five categories: task scheduling, offloading, service placement, uniform load delivery, and resource provisioning. This study also provides an extensive overview of the subject. The application deployment problem in fog infrastructure is solved by proposing MOGA (Multi-Objective Optimization Genetic Algorithm) in35 with the main focus on resource utilization and wastage rate in bandwidth as objectives. Advance resource reservation is used to propose ARFTM in3 with the best reliability. Continuing this chain, Modified Harris-Hawks Optimisation (MHHO) and a two-stage method were proposed for resource allocation in36,37, respectively, aiming to minimize makespan. Continuing this, a reliable HGA (Hybrid genetic Algorithm) task scheduling model, proposed in38, works in different phases, with an important phase of applying new mutation and crossover operations for optimized global search. Apart from this, a QoS-based comparative analysis of the existing state of the art is presented in Table 2.

Proposed work

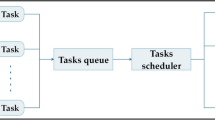

This section explains the proposed CRFTS model, which uses a clustering approach for allocation and the advance reservation of VMs to handle the failure in a dynamic, computationally intensive cloud system. The proposed cluster-based allocation technique can be represented as a bipartite graph between the task set and VM set, as shown in Fig. 1. Additionally, the notions used are presented in Table 3. The System Model and Problem Formulation are illustrated in the subsection below. In this section, we introduced the fault-tolerant-based scheduling algorithm. The incoming tasks are represented as set T= {t1, t2, t3… tn} and the VMs are represented as set V= {v1, v2, v3… vk}. At any decision point (t), only subset Tk of T, i.e., Tk ⊆ T, is known. Since the entire task set T is unknown, the scheduler must make decisions without prior knowledge of tasks, which models the problem as online scheduling. The proposed scheduling assigns each arriving task to a VM based only on the current system state.

System model

The CRFTS system architecture includes several components, as illustrated in Fig. 2. User tasks are submitted to the Application Layer. Besides, in the cloud, the tasks may come from any geographical location at any point in time. The Task Sorter sorts the incoming tasks in ascending order of task size. Similarly, the Host/VM Layer contains a variety of resources with varying processing abilities. VM Sorter sorts the available VMs in ascending order of their processing abilities. Additionally, the sorting of both tasks and VMs is followed by a clustering mechanism where both tasks and VMs are separated into three different clusters, i.e., low, mid, and high clusters, as discussed in the algorithm section. The clustering will further ensure the best-suited task and VM mapping by limiting the task and VM domain of mapping. Furthermore, the VM allocator is responsible for choosing the relevant VM from the cluster for task completion.

Each VM periodically sends a simulated heartbeat signal at a fixed interval δ. The heartbeat controller records the last received time Hj of the signal. If the difference between current time τ and Hj exceeds a threshold “Δ”, the VM is considered faulty and the tasks on it are marked as failed and rescheduled accordingly.

The AR Module/Fault Handler collaborates with the VM Allocator and the Heartbeat Monitor to detect and manage VM and task failures, initiating reservations to ensure the uninterrupted execution of tasks. This coordination guarantees fault-tolerant execution with minimal downtime. The VM allocator also communicates the generated schedule to the AR Module. In response, the AR Module’s Time Manager component predicts the AR slot as given in Eq. 3 based on the schedule produced by the VM allocator. The Reservation Producer component provides the alternative VM for the computed AR slot in case of a fault, thereby initiating the reservation.

Problem formulation

The section presents a foundation for the rest of the work, facilitating readers to understand the objectives, variables, constraints/assumptions, and approach of the research done in the work.

Task and VM Constraints/Assumptions:

-

The model takes the low task heterogeneity benchmark.

-

The task size ranges from 1 to 100 million instructions.

\(1MI~ \leqslant ~Size{\text{ }}({t_i}) \leqslant 100MI\)

-

The model takes the low machine heterogeneity benchmark.

-

The machine speed ranges from 1 to 10 MIPS.

\(1MIPS~ \leqslant ~Speed{\text{ }}({v_j}) \leqslant 100MIPS\)

Objectives of the model: Minimize makespan while maximizing resource utilization and reliability.

Allocation Variables: STij, FTij, Rj, P(ti,vj).

Fault Tolerance Variables: AR, ARM, Status.

The allocation and fault tolerance variables are calculated in the problem formulation section later. The task allocation problem is modelled mathematically as a mapping of every arriving task to the suitable VM cluster to optimize reliability. The proposed model works in five phases:

Phase 1: task clustering

This phase is responsible for organizing the tasks in three clusters, namely, Low task Cluster, Medium task Cluster, and High task Cluster.

Phase 2: VM clustering

This phase is responsible for organizing the VMs in three clusters, namely, Low VM Cluster, Medium VM Cluster, and High VM Cluster.

Phase 3: task to Vm mapping without reservation

In each cluster, the VMs and tasks may be placed in random order because the task and VM clusters are created based on task size and VM speed, respectively, and not based on the number. Mathematically, the mapping (µ) can be represented as follows:

µ: T → V

Every task has its Start time and Finish time, which are computed in Eqs. (1) and (2). To reserve the VM, the task execution time slot, i.e., the AR slot for every task on a suitable VM, is estimated. The AR slot for each task is calculated by taking the difference between ST and FT as computed in Eq. (3). The ST is the time when the task starts executing on the allocated VM. The FT is the time when the task completes its execution on that VM. The execution time of the task is added to the ST of that task to compute the FT. Additionally, each VM has a load history (Rj) that is used to determine when it is ready to execute the new task. Whenever any ti will begin to execute on any vj after mapping according to the allocation procedure. The time at which the allocation of ti begins or starts on vj is known as STij. Rj is first assumed to be STij as seen in Eq. (1)

Once ti has completed its execution on vj, the processing time of ti on vj (p(ti, vj)) is added to the STij as indicated in Eq. (2) to determine the FTij.

Here, p(ti,vj) is computed by dividing the size of ti by the speed of vj.

Phase 4: failure modelling and detection via heartbeat mechanism

The model enables every VM to send a heartbeat signal at certain instances (Hj).

Parameters defined for enabling the heartbeat mechanism:

δ: Heartbeat interval (VM sends the heartbeat every δ units of time), Hj: Last heartbeat timestamp from VM.

T: Current time, Δ: Timeout threshold.

The heartbeat mechanism works in two steps:

Step 1: Heartbeat Sending

The phase initially tracks the time of sending the heartbeat by using the δ as:

\(T{\text{ }}\bmod {\text{ }}\,\delta =\,0\)

If the heartbeat sending time is detected, then VM sends the heartbeat time stamp to the heartbeat controller. After receiving a heartbeat, the controller updates Hj of the corresponding VM with the current time (τ).

\(H\left( {{v_j}} \right){\text{ }}=\tau\)

Step 2: Heartbeat Scanning

The heartbeat controller performs this phase, and it periodically scans the heartbeat of VMs. If the heartbeat of any VM is not found within the time, then it is declared as faulty and ejected from the cluster. The controller measures the past time since the most recent heartbeat was acknowledged from the VM and uses this interval as a pointer for detecting VM failure as:

\(Last\_Breath\,=\,\tau --H\left( {{v_j}} \right)\)

If the Last_Breath exceeds the timeout threshold, then the controller declares the VM as failed by indicating the following:

\(H\left( {VM} \right) = \left\{ \begin{gathered} 1,~~\,\,if~heartbeat~received~from\,~VM~within~Timeout \hfill \\ 0,\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\,\,\,Otherwise \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right.\)

Phase 5: fault tolerance via reservation

In this phase, Task VM mapping is performed, and simultaneously, VMs are monitored for faults using the heartbeat mechanism. In case of faults, advance reservation is enabled and an alternative VM is provided to the affected task. If any VM leaves the system or fails at any point in time, and fault tolerance is not there, the associated tasks may suffer premature termination. The problem is addressed by accompanying the scheduling with a proactive, advance reservation fault tolerance technique. Let’s suppose ‘f’ VMs are failing and these ‘f’ VMs are taken as a separate set of failed VMs (Vf) and are defined as:

\({V_f}={\text{ }}\{ {v_f}:{\text{ }}{v_f} \in V{\text{ }}and{\text{ }}\left| {{V_f}} \right|{\text{ }}=f\}\)

This failure of VMs will affect the corresponding tasks and cause them to fail. Let ‘u’ be the number of unsuccessful tasks. Similarly, these ‘u’ unsuccessful tasks are taken as a separate set of unsuccessful tasks (Tu) and are defined as:

\({T_u}={\text{ }}\{ {t_u}:{\text{ }}{t_u} \in T{\text{ }}and{\text{ }}\left| {{T_u}} \right|{\text{ }}={\text{ }}u{\text{ }}\& {\text{ }}u<=\left| T \right|\}\)

Now, these unexecuted tasks need to be reassigned to some alternative VM to complete their execution, which is done by the advance reservation technique. All tasks in Tu are migrated to another VM (Vj) having the least RT from (Vf) for the calculated AR slot such that Vj ∉ Vf as discussed in Algorithm 5.

The proposed clustering approach allocates tasks in three ways. First, sorting helps the model to achieve a one-to-one suitable order. Thereafter, clustering before allocation restricts the domain of allocation, which allows the model to assign the most appropriate VM to the task. Lastly, the task from each cluster is allocated to the corresponding VM clusters only, which helps the model to avoid under- and overutilization of the VM up to a certain degree. However, there are still chances of over- and underutilization of VMs, which will be handled by integrating the proposed approach with an efficient load-balancing technique that is under consideration for future work, which continuously monitors the under- and over-utilizing VMs and shifts the load between them.

Performance metrics

After the successful task execution, the reliability of the system is checked. Additionally, the makespan is taken as the highest or maximum among all TETj and can be expressed as Eq. (4)32.

Progress percentage of makespan (Ppm): It is the percentage of progress in makespan offered in proposed CRFTS over the other existing approaches, i.e., HEFT, E-HEFT, and LB-HEFT approaches, and is calculated in the Eq. (5)33.

Average of (Ppm): To calculate the deviation from the desired rate in percentage, divide the sum of every Ppi for each tested VM by their respective tested numbers, as shown in the Eq. (6)34.

The Average VM utilization of the system is calculated in the Eq. (7) as35.

Progress percentage of UT (Ppu): It is the ratio defining the progress percentage of average utilization of the proposed CRFTS and other compared approaches and is calculated in the Eq. (8) as36.

Average of (Ppm): To calculate the deviation from the desired rate in percentage, divide the sum of every Ppu for each tested VM by the respective number of tests, as shown in the Eq. (9)37.

Finally, reliability is computed by the Eq. (10)

The Model readily provides the reserved VM as an alternative VM for the impacted task to ensure the successful execution of every task. Thereby, confirming maximum reliability in the event of more than 50% of faulty VMs.

Pseudocode and algorithm

The proposed pseudocode works by taking some assumptions and parameters listed as follows:

-

Firstly, the system’s input parameters, such as the task number, task size, number of VMs, processing speed, and the times at which each resource is available, i.e., ready time, were established.

-

Initially, the ready time of the VM is determined as the total execution time.

-

The selected tasks, early start time, and actual finish time with calculated time slots are initialized in the ARM matrix with the status flag.

-

As per the heterogeneity considered in the model, i.e., low task and low machine heterogeneity, the task size ranges from 1 million instructions to 100 million instructions, and the machine heterogeneity ranges from 1 MIPS to 10 MIPS.

The steps of pseudocode followed by the proposed algorithm for generating the schedule are as follows:

Proposed pseudocode for CRFTS

Let T and V be the set of tasks and VMs, respectively.

-

1.

Sort tasks and VMs:

-

T= {t1, t2, t3, …tn} such that S(ti) in T is in ascending order.

-

V= {v1, v2, v3, …vm} such that Sp(vm) in V is in ascending order.

-

-

2.

Task Clustering:

-

Calculate mid, low_mid, and high_mid for task set (T).

-

Set the boundaries of three task clusters as shown in the algorithm below.

-

-

3.

VM Clustering:

-

Calculate mid, low_mid, and high_mid for VM set (V).

-

Set the boundaries of three VM clusters as shown in the algorithm below.

-

-

4.

Task to VM mapping:

-

5.

Detecting failed VMs and failed tasks.

-

6.

Remove failed VMs from the list of VMs.

-

7.

VM Reservation:

-

If (fault occurs)

Reserve VM for the corresponding AR slot.

-

Update ARM with recent task information.

-

Turn the Status of the corresponding task to 1, implying VM is reserved for the AR slot.

-

Repeat steps 4 and 5 for all tasks in T.

After the task set is empty, check the parameters of the model as in Eqs. 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10.

Proposed algorithm (Task allocation and fault tolerance)

Phase 1: task clustering

The set of tasks (T) is taken as input by the Task Clustering algorithm and separates T into three different clusters as presented in Algorithm 1 below:

Phase 2: VM clustering

The set of VMs (V) is taken as input by the VM Clustering algorithm and separates V into three different clusters as presented in Algorithm 2 below:

Phase 3: task to VM mapping

The algorithm maps the tasks to the suitable VMs in the corresponding task and VM cluster. The algorithm works in two steps. In step 1, fresh VMs are allocated, and in step 2, the VMs with the minimum ready time are allocated to the next tasks. Algorithm 3 is presented below:

Note 1: The Initial task to the VM mapping algorithm maps tasks to VMs without reservation. The algorithm considers all available VMs for allocation created in clustering.

Phase 4: failure modelling and detection via heartbeat mechanism

The set of VMs is taken, and this algorithm tracks every VM for its breaths to detect faulty VMs and is presented in Algorithm 4 below:

Phase 5: fault tolerance via reservation

The model uses this algorithm in case of a fault in any of the VMs. If any VM fails, the fault tolerance algorithm provides an alternative VM for the affected task based on the reservation. The model uses a structured data structure known as ARM (Advanced Reservation Matrix), used to keep track of the advance reservation task status in the fault tolerance phase. Each row of ARM indicates a particular task to VM reservation and includes the following:

T_ID(\(\:{t}_{i}\)): Unique identifier of the task

VM_ID \(\:{(v}_{f})\): The initially mapped failed VM

VM_ID \(\:{(v}_{j}\)): The reserved VM.

AR_Slot: The advance reservation slot

Status: A flag signifying the state of the reservation

This algorithm is shown below:

Note 2: When a failed VM and corresponding failed tasks are detected by Algorithm 3, CRFTS reserves the VM with the least ready time entirely for the failed task. This VM is then not considered for general task allocations until the failed task is executed completely.

Figure 3 presents the proposed CRFTS algorithm’s flowchart to aid in understanding the model more clearly. The flowchart includes a detailed representation of the entire procedure.

Computational time complexity of CRFTS

CRFTS involves the following Steps:

-

1.

Initialization and Input Parsing

This typically consists of getting the task and VM information. The complexity is O(1) for each input.

Task to VM Mapping

-

2.

Sorting Tasks or VMs:

The algorithm involves sorting tasks or VMs based on Task size and VM Speed. Sorting can be done with the complexity of O(nlogn) and O(klogk), respectively, where n and k are the number of tasks and number of VMs, respectively.

-

3.

Clustering:

Task and VM clusters are obtained with the complexity of O(n) and O(k), respectively. Therefore, the overall complexity of the clustering phase will be O(n+k).

-

4.

Allocating Tasks to VMs within Clusters:

We need to analyze the phases involved in the allocation process. Mapping each task to the VM in the corresponding VM cluster, the complexity can be computed as follows:

Reading the task and VM data:

The complexity will be O(1)

Iterating through task and VM clusters:

We need to iterate through each task cluster to assign tasks to VMs within the corresponding VM cluster. Since there are 3 clusters, let each cluster contain a maximum of m tasks and v VMs, respectively. The complexity of this phase will be O(m+v).

Allocating Tasks to VMs within Clusters:

For each task in a cluster, we allocate it to a VM in the corresponding VM cluster. This typically involves:

-

Iterating through each task in a task cluster: O(m).

-

Iterating through each VM in VM cluster: O(v).

-

Since allocation is performed on two conditions. Therefore, as per the algorithm, the complexity of allocation will be O(1) for the first condition. O(v) for the second condition.

-

The combined complexity will be computed as: O(m) + O(v)+ O(1) +O (v) = O(m+v).

Fault Tolerance Algorithm

The fault tolerance mechanism involves the following steps:

-

-

5.

Detection of faulty VMs:

Checking the status of each VM to detect faults. This step involves iterating through all VMs and can be done in O(k).

-

6.

Redistributing tasks from faulty VMs to healthy VMs:

For f faulty VMs with a maximum of t tasks, the complexity will be O(f⋅t). In the worst case, f⋅t will be equal to n, so the complexity will be O(n).

-

7.

Updating execution times:

Updating the total execution times for VMs. The worst-case complexity will be O(f.t)= O(n).

Combined Total Complexity

Combining these complexities, the overall complexity of CRFTS is dominated by the sorting phase. Thus, the overall time complexity can be expressed as:

O(1) + O(nlogn) + O(klogk) + O(n+k) + O(1) + O(m+v) + O(m) + O(v) + O(1) + O(v) + O(m+v) + O(k) + O(n) + O(n).

=(nlogn) + O(klogk)

Since n will always be greater than k, the final complexity of CRFTS will be O(nlogn).

Results and observations

The model was evaluated on an MSI GF 65 (2021 Model) computer, equipped with a 4 GHz hexa-core Intel Core i5 processor with Windows 11. Python 3.7 is the preferred language for implementation, including the following tools.

-

The Python script’s input for a spreadsheet containing the sizes of tasks and capacity for resources was created and managed in Excel.

-

Jupyter Notebook for implementation in Python.

-

The following libraries of Python are used:

-

Pandas 1.1.2 is used to handle CSV files while applying vector algebra in Numpy 1.19.2.

-

An operator is used to sort a dictionary.

-

Random was used to generate random numbers.

-

To reduce the influence of random variations, we conducted each experiment for 10 iterations and represent results in average standards across these iterations.

-

Experimental setup

An analysis of the performance of the proposed CRFTS algorithm has been conducted in small and large task scales. The proposed model was compared based on makespan and average resource utilization while competing with HEFT, E-HEFT, LB-HEFT, BDHEFT, HO-SSA, and MOTSWAO algorithm on a small task scale. The Montage benchmark42,43 has been used to mimic the Bag of Tasks (BoT) by flattening the dependencies and implementing the suggested CRFTS algorithm in a heterogeneous environment, evaluated on 5, 10, 20, and 40 VMs for varying the tasks from 25 to 1000. However, for large task scales, the task ranges are taken from 512 to 4096, and the model was cultivated with the existing HEFT, FTSA-1, DBSA, BDHEFT, HO-SSA, and MOTSWAO algorithms in terms of makespan and average resource utilization in the case of 100 VMs. Furthermore, the model was evaluated in terms of reliability while comparing with HEFT, FTSA-1, DBSA, BDHEFT, HO-SSA, and MOTSWAO on a small task scale. Additionally, the size of task heterogeneity ranges from 1 to 100 MI, while the speed of VM heterogeneity ranges from 1 to 10 MIPS. Table 4 presents the experimental environment for better understanding. The results show that the recommended model performs better than the comparison techniques. Recent advancements in low-latency service orchestration44 and adaptive fault-tolerant mechanisms45 further validate the relevance and applicability of CRFTS in dynamic and heterogeneous cloud infrastructures, where minimizing delay and ensuring high reliability are critical.

Makespan

Concerning the makespan, the proposed CRFTS is evaluated for both small and large task scales.

Makespan for small task scale

In Fig. 4a–d, the implementation results of our suggested CRFTS are shown in comparison to other similar approaches concerning makespan using Montages of 25, 50,100, 500, and 1000 by considering 5, 10, 20, and 40 VMs. As the number of VMs exceeds 10, the CRFTS surpasses the other compared algorithms in terms of task completion time for any number of VMs, according to the comparative results in Fig. 4a–d. This is because, while mapping, the CRFTS utilizes a clustering approach that restricts the mapping domain of both tasks and VMs and thereby selects an appropriate VM for the task.

Observations

It is observed that HEFT, E-HEFT, and LB-HEFT perform well in the case of a small number of VMS. Out of all methods, the E-HEFT algorithm offers the highest makespan as the number of VMs increases. This may be due to the Matching Game theory that is used in E-HEFT to assign tasks to the appropriate VMs. However, the matching game theory selections take all tasks and VMs into consideration, which requires a lengthy selection process and reduces the makespan. It is also observed that MOTSWAO and BDHEFT offer more makespan when the number of VMs are 5 but as the number of VMs crosses 20, the makespan gets optimised. The results demonstrate that the proposed CRFTS algorithm outperforms the other algorithms. Specifically, as the quantity of VMs increases to 40, the laid-out algorithm outperforms the HEFT, E-HEFT, and LB-HEFT algorithms in terms of makespan for any number of tasks and VMs, as seen in Fig. 4c and d.

Ppm over other compared approaches

Further, the results of comparing the proposed CRFTS algorithm’s average enhancements (average progress percentage (Ppm)) to the compared approaches with respect to the makespan in percentage computed as in Eqs. 4 and 5 employing 5, 10, 20, and 40 VMs using various task sizes with the existing algorithms are shown in Table 5 for comparison.

Makespan for large task scale

Furthermore, Fig. 5 displays the implementation outcomes of our suggested CRFTS in comparison with HEFT, FTSA-1, DBSA, BDHEFT, HO-SSA, and MOTSWAO algorithms concerning makespan on varying the number of tasks from 512 to 4096. The CRFTS model improves over other comparison algorithms in terms of makespan to complete the workflow for any range of task numbers, according to the comparative results in Fig. 5.

Observations

Out of all the approaches, HEFT offers an optimized makespan after the proposed CRFTS. However, FTSA-1 provides the highest makespan among all the approaches. It may be because FTSA-1 is focusing more on reliability than on makespan. According to the results related to makespan, CRFTS shows 40%, 6.32%, 9.358%, and 25.870% improvements over HEFT in 512, 1024, 2048, and 4096 tasks, respectively. Comparing CRFTS with DBSA and FTSA-1, the proposed CRFTS shows more than 40% improvements across different task numbers. Finally, compared to BDHEFT, HO-SSA, and MOTSWAO, the proposed CRFTS shows 3%, 3.2%, and 4.1% improvements, respectively.

Average resource utilization

In analysing the Average Resource Utilisation, again the evaluation is made into two task scales, the small task scale and the large task scale.

Average resource utilization for small task scale

The performance of CRFTS has improved resource utilization per VM compared to other methods, as shown by the findings in Fig. 6a–d. As the number of virtual computers rises, this tendency continues. However, as the number of tasks rises, the utilization shown by the CRFTS increases dramatically. Besides, with an increase in task number, the utilization of the other three models decreases. As can be seen from Fig. 6b, the proposed CRFTS offers optimal utilization, especially in the case of high task numbers, and all three other comparison models perform very low utilization of resources. Moreover, all the comparison approaches work well for the low range of task numbers. However, as the task number increases, the utilization of the comparison models decreases. Unlike the proposed model, which shows a constant growth in the utilization with an increase in task number.

Observation

CRFTS was shown to be heavily utilized across all VM ranges, particularly for more than 100 tasks. Furthermore, the utilization of CRFTS is found to be approximately constant on varying tasks or VMs. This is because of the sorting and clustering done before allocation. Moreover, CRFTS is found to be more optimal than the compared approaches in all three considered parameters. Additionally, HEFT was shown to have the lowest average utilization among the other techniques. Moreover, LB-HEFT was found to be the second-best model in the case of utilization after CRFTS. However, when the number of tasks is less than 50, LB-HEFT performs somewhat better than CRFTS. It was also observed that as the number of VMs increases, HO-SSA and BDHEFT perform well after CRFTS. Additionally, as compared with HEFT, the proposed approach shows improvements in utilization from 3 to 33%. CRFTS shows improvements of 2–30% as compared to E-HEFT. This may be because, in this approach, the maximum number of servings per machine must be considered when selecting a machine for each job. While comparing CRFTS with LB-HEFT, the suggested model has shown improvements of 0–30%.

Ppu over other compared approaches

Additionally, the results of comparing the proposed CRFTS algorithm’s average enhancements (Ppu) to the compared approaches concerning the average resource utilization in percentage computed as in Eqs. 7 and 8 employing 5, 10, 20, and 40 VMs using various task sizes with the HEFT, E-HEFT, and LB-HEFT existing algorithms are shown in Table 6 for comparison.

Average resource utilisation for large task scale

Figure 7 displays the implementation outcomes of our suggested CRFTS in comparison with HEFT, FTSA-1, and DBSA algorithms concerning average resource utilization as the number of jobs varies from 512 to 4096. The CRFTS offers improved average resource utilization compared to other algorithms to complete the workflow for any range of task numbers, according to the comparative results in Fig. 7.

Observations

The average resource utilization provided by FTSA-1 was found to be very low compared to the other approaches. The utilization offered by HEFT is second optimal after CRFTS. CRFTS was found to be optimum as compared to other methods. Further, the performance of HO-SSA, BDHEFT, and MOTSWAO degrades in this case. According to the results concerning average resource utilization, CRFTS shows 14.38624%, 2.415644%, 3.169663%, and 2.083104% improvements over HEFT, 36.55696%, 37.33824%, 30.07273%, and 19.15755% improvements DBSA and 19.05063%, 7.11148%, 8.54854%, and 8.130822% improvements over FTSA-1 in 512, 1024, 2048, and 4096 number of tasks respectively.

Reliability

The model is compared with HEFT, DBSA, and FTSA-1 and was evaluated based on reliability, where the number of tasks varied from 25 to 1000. The minimum reliability of HEFT, FTSA-1, and DBSA is 58.71%, 96.10%, and 93.34% respectively. At the same time, the reliability of the proposed CRFTS ranges from 99.3 to 99.9% on varying task numbers.

The model is compared with other fault-tolerant models like HEFT, DBSA, and FTSA-1, and was evaluated based on reliability, where the number of tasks varied from 25 to 1000, as can be seen in Fig. 5.13. The performance of CRFTS has improved reliability as compared to other methods, as shown by the findings in Fig. 8a–d. As the number of virtual computers rises, the reliability increases. However, as the number of tasks rises, reliability typically decreases. As can be seen from Fig. 5.13a–d, the proposed CRFTS offers increased reliability. However, when the number of VMs is 40, FTSA-1, DBSA, and the proposed CRFTS performed optimally. Besides, the tendency of increased reliability offered by CRFTS continues as shown in Fig. 5.13d.

Observations

Additionally, with the increase in task number, the reliability of all the approaches decreases, as can be seen in Fig. 8. However, CRFTS shows constant reliability specifically for 20 and 40 VMs. It is discovered that HEFT has extremely low reliability as compared to other approaches. It may be because HEFT does not offer any fault handling mechanism and thereby does not provide guaranteed task completion in case of failure. Moreover, HEFT always assigns tasks to the processor with the Earliest Finish time (EFT) without considering load balancing across processors. CRFTS, DBSA, FTSA-1, and MOTSWAO are in a race, in which CRFTS outperforms and MOTSWAO shows less reliability. Furthermore, the CRFTS shows an increase of 12.71–71.06%, 1.12–3.95%, and 1.31–6.54% for HEFT, FTSA-1, and DBSA, respectively. The improvements in the reliability of the proposed CRFTS are because of the advance reservation employed for handling the faults.

Conclusion and future directions

To get around the overheads of the compared approaches, the work in this article introduces the novel clustering approach for task scheduling, namely CRFTS. The proposed CRFTS allocates the tasks in such a way that makespan is minimized and utilization is maximized. Among all the compared approaches, the optimal makespan is provided by the proposed CRFTS due to its clustering-based task allocation approach. However, the longest makespan is supplied by the E-HEFT method. This is because each task is mapped by the E-HEFT algorithm table using the optimal VM rules over the matching game theory. Additionally, CRFTS shows the increased resource utilization as the number of tasks increases. Conversely, the utilization of all other compared approaches decreases as the number of tasks increases. On the other hand, the LB-HEFT method performs better than HEFT in terms of resource utilization for the considered VMs, as shown by the comparative findings in Fig. 6a–d. This is because, in contrast to the HEFT algorithm, which always selects the device with the earliest finish time without taking the number of tasks on the machine into account, the LB-HEFT algorithm depends on the number of tasks assigned to each machine, which influences consumption of the devices at a rate close to one another. Furthermore, the progress percentage of both makespan (Ppm) and utilization (Ppu) revealed by LB-HEFT is significantly related to the other compared algorithms and was also computed. The model is also enhanced in terms of different parameters, such as reliability and average resource utilization. The reliability of the model was improved by making the proposed scheduling approach fault-tolerant. The fault tolerance is incorporated in the model by using the reservation technique, where the VM is bound to the task for the pre-estimated time slot known as the reservation slot. This binding of VMs to the task manages the failure of any cloud-based VM. The model was compared with 7 existing models, i.e., HEFT, E-HEFT, LB-HEFT, FTSA-1, DBSA, HO-SSA, BDHEFT, and MOTSWAO, by varying the number of VMs and tasks. The evaluations are carried out for small and large task scales on a varying number of VMs from 5 to 40. The outcomes demonstrate that the suggested model outperforms all the considered methods. More particularly, as the number of tasks is increasing, the model shows a constant growth in the considered parameters.

Future directions

In the future, an efficient load-balancing algorithm will be developed, and the model will be evaluated on the large variations of both tasks and VMs. Besides, predicting the behaviour of VMs can be used to extend this technique and produce more optimal outcomes by incorporating intelligent ML approaches. In transient failure cases, recovery from failures could be endeavoured on the same VM after a short-term wait or revision. In contrast, in permanent failure, reallocation should be done immediately to another VM. Further, the cluster-wise allocation avoids over-and underutilization of VMs to a certain degree. However, it is possible to enhance the model by using some load-balancing approaches to monitor further over- and underutilization of VMs. Additionally, it can be taken as a multi-objective model that has several objectives, including flowtime, energy, and dependability. The work can be extended by exploring and incorporating security measures to enhance the robustness of the model. We also plan to include a configurable fault injection mechanism grounded on MTBF, failure prospect, or workload outlines as part of our future work, which is the main limitation of the CRFTS. This allows us to satisfy user needs while conserving system resources. The work can also be replicated by extending the model to priority-based reservation. High-priority tasks are immediately reallocated, while low-priority tasks are placed in a recovery queue. This confirms fair and efficient recovery without overloading the system, especially in cases where the number of failed tasks exceeds the number of healthy VMs.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Goutam, S. & Yadav, A. K. Preemptable priority based dynamic resource allocation in cloud computing with fault tolerance. In: International Conference on Communication Networks (ICCN) 278–285. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCN.2015.54 (IEEE, 2015).

Laxkar, N. K. R. & Pradeep load balancing algorithm in distributed network. Solid State Technol. 6633–6645. (2020).

Mushtaq, S. U. & Sheikh, S. A fault-tolerant resource reservation model in cloud computing. In Recent Advances in Computing Sciences 295–301 (CRC, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003405573-53.

Burchard, J. S. L. O. & Linnert, B. A distributed load-based failure recovery mechanism for advance reservation environments. In: Fifth IEEE International Symposium on Cluster Computing and the Grid (CCGrid’05) 1071–1078. (2005).

Zhao, M. & Figueiredo, R. J. Experimental study of virtual machine migration in support of reservation of cluster resources. In: 2nd International Workshop on Virtualization Technology in Distributed Computing (2007).

Foster, I., Kesselman, C. & Tuecke, S. The anatomy of the grid: enabling scalable virtual organizations. Int. J. High Perform. Comput. Appl. 15(3), 200–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/109434200101500302 (2001).

Haider, S. & Nazir, B. Fault tolerance in computational grids: perspectives, challenges, and issues. Springerplus https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-3669-0 (2016).

Olteanu, A., Pop, F., Dobre, C. & Cristea, V. A dynamic rescheduling algorithm for resource management in large scale dependable distributed systems. Comput. Math. Appl. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.camwa.2012.02.066 (2012).

Liu, X. & Buyya, R. Resource management and scheduling in distributed stream processing systems. ACM Comput. Surv. 53(3), 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1145/3355399 (2021).

Topcuoglu, H., Hariri, S. & Wu, M. Y. Performance-effective and low-complexity task scheduling for heterogeneous computing. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 13(3), 260–274. https://doi.org/10.1109/71.993206 (2002).

Benoit, A., Hakem, M. & Robert, Y. Fault tolerant scheduling of precedence task graphs on heterogeneous platforms. In 2008 IEEE International Symposium on Parallel and Distributed Processing 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1109/IPDPS.2008.4536133 (IEEE, 2008).

Liu, J., Wei, M., Hu, W., Xu, X. & Ouyang, A. Task scheduling with fault-tolerance in real-time heterogeneous systems. J. Syst. Archit. 90, 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sysarc.2018.08.007 (2018).

Benkaouha, H., Badache, N., Abdelli, A., Mokdad, L. & Ben Othman, J. A novel hybrid protocol of checkpointing and rollback recovery for flat MANETs. Int. J. Auton. Adapt. Commun. Syst. 10 (1), 114. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJAACS.2017.082745 (2017).

Samadi, Y., Zbakh, M. & Tadonki, C. E-HEFT: Enhancement heterogeneous earliest finish time algorithm for task scheduling based on load balancing in cloud computing. In International Conference on High Performance Computing & Simulation (HPCS) 601–609. https://doi.org/10.1109/HPCS.2018.00100 (IEEE, 2018).

Mahmoud, H., Thabet, M., Khafagy, M. H. & Omara, F. A. An efficient load balancing technique for task scheduling in heterogeneous cloud environment. Cluster Comput. 24, 3405–3419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10586-021-03334-z (2021).

Ye, K., Jiang, X., Huang, D., Chen, J. & Wang, B. Live migration of multiple virtual machines with resource reservation in cloud computing environments. In IEEE 4th International Conference on Cloud Computing 267–274. https://doi.org/10.1109/CLOUD.2011.69 (IEEE, 2011).

Shiekh, S., Shahid, M., Sambare, M., Haidri, R. A. & Yadav, D. K. A load-balanced hybrid heuristic for allocation of batch of tasks in cloud computing environment. Int. J. Pervasive Comput. Commun. 19(5), 756–781. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPCC-06-2022-0220 (2023).

Sheikh, S., Shahid, M. & Nagaraju, A. A novel dynamic task scheduling strategy for computational grid. In 2017 International Conference on Intelligent Communication and Computational Techniques (ICCT) (2017).

He, H. Virtual resource provision based on elastic reservation in cloud computing. Int. J. Netw. Virtual Organ. 15 (1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJNVO.2015.069295 (2015).

Tian, W. et al. On minimizing total energy consumption in the scheduling of virtual machine reservations. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 113, 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnca.2018.03.033 (2018).

Sheikh, S., Nagaraju, A. & Shahid, M. A fault-tolerant hybrid resource allocation model for dynamic computational grid. J. Comput. Sci. 48, 101268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocs.2020.101268 (2021).

Abedpour, K., Hosseini Shirvani, M. & Abedpour, E. A genetic-based clustering algorithm for efficient resource allocating of IoT applications in layered fog heterogeneous platforms. Cluster Comput. 27(2), 1313–1331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10586-023-04005-x (2024).

Malla, S. S. & Ahmad, P. Analysis of QoS aware energy-efficient resource provisioning techniques in cloud computing. Int J. Commun. Syst. 36 1. (2023).

Park, J. & Deadlock, A. Livelock free protocol for decentralized internet resource coallocation. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part A Syst. Hum. 34(1), 123–131. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSMCA.2003.820571 (2004).

J MacLaren. Advance Reservations: State of the Art, Ggf graap-wg. http://www.fz-juelich.de/zam/RD/coop/ggf/graap/graap-wg.html (2003).

Buyya, R. A. S. and A grid simulation infrastructure supporting advance reservation. In 16th International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Computing and Systems (PDCS 2004) 9–11. (2004).

Depoorter, W., Vanmechelen, K. & Broeckhove, J. Advance reservation, co-allocation and pricing of network and computational resources in grids. Futur Gener Comput. Syst. 41, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2014.07.004 (2014).

Zhao, B., Aydin, H. & Zhu, D. Shared recovery for energy efficiency and reliability enhancements in real-time applications with precedence constraints. ACM Trans. Des. Autom. Electron. Syst. 18(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1145/2442087.2442094 (2013).

St°ahl, P. J. B. Dynamic Fault Tolerance and Task Scheduling in Distributed Systems. (2016).

Grzonka, D., Kołodziej, J., Tao, J. & Khan, S. U. Artificial Neural Network support to monitoring of the evolutionary driven security aware scheduling in computational distributed environments. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 51, 72–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2014.10.031 (2015).

Aron, R., Chana, I. & Abraham, A. A hyper-heuristic approach for resource provisioning-based scheduling in grid environment. J. Supercomput 71(4), 1427–1450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-014-1373-9 (2015).

Poola, D., Salehi, M. A., Ramamohanarao, K. & Buyya, R. A Taxonomy and Survey of Fault-Tolerant Workflow Management Systems in Cloud and Distributed Computing Environments. In Software Architecture for Big Data and the Cloud 285–320 (Elsevier, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-805467-3.00015-6.

Elliott, J., Hoemmen, M. & Mueller, F. Exploiting data representation for fault tolerance. J. Comput. Sci. 14, 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocs.2015.12.002 (2016).

Walia, G. K., Kumar, M. & Gill, S. S. AI-Empowered fog/edge resource management for IoT applications: A comprehensive review, research challenges, and future perspectives. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials. 26 (1), 619–669. https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2023.3338015 (2024).

Hosseini Shirvani, M. & Ramzanpoor, Y. Multi-objective QoS-aware optimization for deployment of IoT applications on cloud and fog computing infrastructure. Neural Comput. Appl. 35(26), 19581–19626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-023-08759-8 (2023).

Yakubu, I. Z. & Murali, M. An efficient meta-heuristic resource allocation with load balancing in IoT-Fog-cloud computing environment. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 14(3), 2981–2992. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-023-04544-6 (2023).

Zahraddeen Yakubu, I. & Murali, M. An efficient IoT-Fog-Cloud resource allocation framework based on Two-Stage approach. IEEE Access. 12, 75384–75395. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3405581 (2024).

Khademi Dehnavi M, Broumandnia A, Hosseini Shirvani M, Ahanian I (2024) A hybrid genetic-based task scheduling algorithm for cost-efficient workflow execution in heterogeneous cloud computing environment. Cluster Comput 27 (8):10833–10858. doi: 10.1007/s10586-024-04468-6.

Mushtaq, S. U., Sheikh, S. & Nain, A. The response rank based fault-tolerant task scheduling for cloud system. 37–48. https://doi.org/10.2991/978-94-6463-366-5_5 (2024).

Umar Mushtaq, S., Sheikh, S. & Idrees, S. M. Next-Gen cloud efficiency: Fault-Tolerant task scheduling with neighboring reservations for improved resource utilization. IEEE Access. 12, 75920–75940. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3404643 (2024).

Mangalampalli, S., Karri, G. R. & Kumar, M. Multi objective task scheduling algorithm in cloud computing using grey wolf optimization. Cluster Comput. 26(6), 3803–3822. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10586-022-03786-x (2023).

Montage. An astronomical image engine. http://montage.ipac.caltech.edu. (Accessed May 2021).

Montage. Caltech IPAC Software. https://github.com/Caltech- IPAC/MontageMosaics. (Accessed May 2021).

Sun, G. et al. Cost-efficient service function chain orchestration for low-latency applications in NFV networks. IEEE Syst. J. 13(4), 3877–3888 (2019).

Zeng, Z., Zhu, C. & Goetz, S. M. Fault-Tolerant multiparallel Three-Phase Two-Level converters with adaptive hardware reconfiguration. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 39 (4), 3925–3930. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPEL.2024.3350186 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R138), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sheikh Umar Mushtaq: Conceived the core idea of the study, contributed to the development of the Clustering and Reservation Fault-tolerant Scheduling (CRFTS) model, and led the simulation and evaluation processes. Sophiya Sheikh: Assisted in algorithm design, conducted performance analysis, and contributed significantly to the writing and technical refinement of the manuscript. Ajay Nain: Supported literature review, comparative analysis with existing methods (HEFT, FTSA-1, DBSA, E-HEFT, LB-HEFT), and helped validate simulation outcomes. Salil Bharany: Provided critical revisions, enhanced the methodological framework, and contributed to the interpretation of QoS evaluation metrics. Rania M. Ghoniem: Participated in reviewing the fault-tolerant mechanisms, enriched the paper with theoretical background, and helped align the study with current research standards. Belayneh Matebie Taye (Corresponding Author): Supervised the overall research activity, ensured academic and technical quality, managed the correspondence, and finalized the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mushtaq, S.U., Sheikh, S., Nain, A. et al. CRFTS: a cluster-centric and reservation-based fault-tolerant scheduling strategy to enhance QoS in cloud computing. Sci Rep 15, 32233 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17609-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17609-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Data repair optimization method for geo-distributed fault-tolerant storage systems based on whale optimization algorithm

Journal of Cloud Computing (2025)