Abstract

To address the challenges of low efficiency and high safety risks in manual steel arch installation during Tunnel Boring Machine (TBM) construction, this study proposes an innovative steel arch splicing mechanism. By employing power-concentrated joint analysis and closed-loop reinforcement design, the mechanism demonstrates significantly enhanced dynamic performance and load-bearing capacity. The research first introduces a novel bolt-free steel arch joint structure that enables rapid automatic splicing through a self-locking mechanism. Subsequently, two power-concentrated joints in the mechanism are identified using unit power concentration metrics, and optimized through hydraulic-driven closed-loop structural designs, effectively improving both structural stiffness and power transmission efficiency. Prototype testing results show that the optimized mechanism achieves an impressive load-to-weight ratio of 1.19, with splicing efficiency 4-8 times higher than manual operations, while maintaining stable and reliable grasping and docking performance. This work presents an efficient and reliable solution for automated steel arch splicing in heavy-duty construction environments, offering substantial engineering application value.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The tunnel boring machine (TBM) is a large-scale equipment specifically designed for hard rock tunnel construction, widely employed in railway, hydropower, and transportation projects1,2,3,4,5. During TBM operations, surrounding rock deformation frequently occurs, potentially leading to tunnel collapse6,7,8,9,10. To ensure construction safety, steel arch supports have become essential reinforcement elements in tunneling operations11,12,13. Currently, steel arch installation predominantly relies on manual labor under extremely hazardous conditions - involving intense vibration, heavy dust, poor lighting, high humidity, potential toxic gas exposure, and collapse risks14,15. This manual installation method exhibits low efficiency while imposing excessive physical demands on workers and creating significant safety hazards. Consequently, developing an automated steel arch splicing mechanism to replace manual handling in grasping and docking operations has become imperative.

The conventional steel arch installation process comprises four key operations: transportation, splicing, expansion, and sealing. Initially, steel arches are sequentially transported to the installation equipment. Workers then manually adjust adjacent arches to align their bolt holes before making bolted connections. Subsequently, expansion arms deploy the assembled circular arches against the tunnel walls, followed by welding at the final opening position. Given each steel arch segment weighs up to 200 kg (standard weight for 7-meter diameter tunnels), manual handling proves particularly challenging - requiring multiple workers to coordinate gripping and positioning operations, significantly compromising construction efficiency. Recent years have seen academic proposals for automated TBM steel arch installation systems, with emerging research on supporting mechanisms. However, these investigations remain in nascent stages, primarily focusing on configuration synthesis and control methodologies. He et al.16,17 designed 12 configuration types for steel arch splicing mechanisms and 12 for looping mechanisms, respectively, to address different input constraints and output requirements in the steel arch installation process. Chen et al.18 proposed a backstepping-based cascade control strategy for steel arch splicing manipulators to enhance trajectory tracking performance. Nevertheless, the heavy-load operational environment demands particular attention to structural rigidity and power transmission efficiency19,20,21. A critical research gap exists in analyzing power distribution characteristics of steel arch splicing mechanisms, particularly regarding modifications to joints with concentrated unit power - an area that currently receives limited scholarly attention.

Regarding the power distribution characteristics of mechanisms, scholars have conducted several important studies. Wu et al.22 proposed an energy consumption index based on wrenches and analyzed the power requirements of each actuated joint. Laus et al.23 combined graph theory and screw theory to develop a new universal method for determining the efficiency of complex mechanical systems, which can be used to evaluate the energy transmission efficiency of mechanisms. Yuan et al.24 introduced a unit power concentration index and recommended replacing joints with high unit power concentration coefficients with high-power-density spatial closed-chain mechanisms to improve the load-to-weight ratio of robots. He et al.17 investigated the power distribution characteristics of tree-type open-chain mechanisms and redesigned the power-concentrated joints as low-complexity single-degree-of-freedom closed-chain structures. These studies provide a theoretical foundation for analyzing power-concentrated joints and reinforcement design in steel arch splicing mechanisms.

This paper conducts research on the analysis and reinforcement design of power-concentrated joints in steel arch splicing mechanisms. For the new steel arch splicing configuration, design requirements are proposed and the mechanism configuration is designed. The unit power concentration index of the steel arch splicing mechanism is analyzed, power-concentrated joints are improved with closed-chain designs, and the feasibility of the method is verified through prototype testing.

Design requirements for steel arch splicing mechanism

Bolt-free steel arch structure

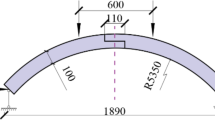

TBM steel arches are typically fabricated using I-beams or H-shaped steel sections. The conventional splicing method involves manual bolted connections between adjacent arch segments at their end sections, as shown in Fig. 1.

The bolted connection method of steel arches is inconvenient for robotic operation, making it necessary to design a new bolt-free splicing configuration as shown in Fig. 2. One end features a shaft with a boss, while the other end has a matching hole with a tapered inner wall that is narrow externally and wide internally. Sliding blocks are arranged above and below the taper, connected to the steel arch via springs. During assembly, when the shaft is inserted into the hole, the sliding blocks are pushed backward by the shaft while expanding outward along the taper. When the shaft is fully inserted, the sliding blocks are pushed forward by the springs, securely fixing the shaft within the hole and completing the automatic locking of the steel arch connection. The tapered interface design and permanent locking feature are particularly advantageous for tunneling applications as they naturally resist loosening from vibrations and maintain connection integrity even with minor alignment variations.

Motion requirements for steel arch splicing mechanism

To achieve automated steel arch splicing, a dedicated splicing mechanism must be designed. The steel arch splicing mechanism shall possess three core functions: grasping adjacent steel arches, posture adjustment, and forced docking. During operation, the mechanism must ensure precise alignment between the shaft of one steel arch and the mating hole of the adjacent arch, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

The steel arch splicing mechanism must perform grasping, adjustment and docking operations, requiring left and right jaws to grasp the steel arches separately and then execute coordinated spatial movements. According to the motion requirements of the splicing process, the mechanism is divided into grasping and docking modules.

The grasping module consists of upper and lower jaws that perform corresponding movements within their working spaces. To ensure grasping quality, the lower jaw is initially positioned directly below the steel arch and approaches it from bottom to top. During grasping, the upper and lower jaws must open and close - separating to a certain distance when approaching the arch to avoid collision, then closing (upper jaw moving downward toward lower jaw) when fully engaged to clamp the steel arch.

The grasping module requires positional adjustment within the vertical plane of the steel arch to reach the grasping point. After grasping, it must perform lateral movements within this plane to achieve arch docking. These movements are driven by the docking module.

Configuration design of steel arch splicing mechanism

Based on the I-beam cross-section of steel arches, the upper and lower jaws of the steel arch splicing mechanism are designed with an “L” shape configuration. To meet the motion requirements of the grasping module, both jaws are mounted on separate prismatic joints, with their guide rails interconnected through a revolute joint to enable the opening and closing functions of the grasping module. The designed structure of the grasping module is shown in Fig. 4.

According to the motion requirements of the docking module, it can be designed as either a 2R or 1R1P structure, as shown in Fig. 5. In the figure, R represents a revolute joint and P represents a prismatic joint. The 1R1P configuration was chosen over 2R because it better suits steel arch splicing operations. The revolute joint adjusts grasping orientation while the prismatic joint handles docking motions separately, avoiding the complex coupled control and interference risks of coordinating two rotating joints in 2R configurations. This simpler, more reliable design aligns with engineering machinery principles.

By combining the grasping module shown in Fig. 4 with the docking module (1R1P configuration) shown in Fig. 5b, the configuration of the steel arch splicing mechanism can be obtained as illustrated in Fig. 6. The grasping module is fixed to the sliding block of the docking module, and the motion of the docking module drives the grasping module to complete both position/orientation adjustment and docking operations of the steel arches.

Analysis of power-concentrated joints and closed-chain design

Analysis of power-concentrated joints

During the steel arch splicing operation, all mechanism joints must meet power output requirements. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the power demand of each actuated joint in the steel arch splicing mechanism. Yuan et al.24 provided comprehensive mathematical derivations of the unit power concentration index, including detailed examples. This index proves particularly well-suited for addressing this category of engineering challenges.

The power of the \(\textit{i}\)-th kinematic chain under unit mass load can be expressed as

where \(\varvec{1}_{1 \times (n+1)}\) and \(\varvec{1}_{(n+1) \times 1}\) are row and column vectors composed of (n+1) unity elements, respectively; \(\textit{n}\) is the number of joints in the i-th kinematic chain; \(\dot{\varvec{g}}_{\text{ index } }\) is the maximum velocity vector specified by task requirements (defaulting to \(\dot{\varvec{g}}_{\text{ index } }= \varvec{1}_{n \times 1}\)); \(\varvec{K}_{\varvec{T} i}\) represents the power topology matrix; \(\otimes\) is the Kronecker product25; \(*\) is the Hadamard product26.

The power topology matrix \(\varvec{K}_{\varvec{T} i}\) can be expressed as

where \(\varvec{T}_{i\_ u}\) is the twist of the u-th joint in the i-th kinematic chain; \(\varvec{W}_{i\_v}\) is the direction screw of the gravity load on the wrench, and \(v=n+1\) represents the terminal external load; \(\circ\) is the reciprocity product.

The unit power concentration index \(\varvec{SK_{T}}\) of the steel arch splicing mechanism is expressed as

where \(\varvec{P_{T}}\) represents the power of the steel arch splicing mechanism under unit mass load, expressed as the superposition of power \(\varvec{P_{T}}_i\) from all kinematic chains.

The power concentration analysis based on unit mass load enables the identification of power-concentrated joints during the configuration synthesis stage and guides the design of closed-chain structures.

Due to the completely bilateral symmetry in both the structural design and working load conditions of the steel arch splicing mechanism, only the left-half section was analyzed. Based on screw theory, the kinematic model of the left-half section of the steel arch splicing mechanism is established as shown in Fig. 7.

The screw system of kinematic chain A-B-C in the steel arch splicing mechanism can be expressed as

The direction screw of the gravity load on the wrench can be expressed as

Given the end-effector load characteristics of the lower jaw in the steel arch splicing mechanism (with \({{\varvec{W}}_{1\_n + 1}} = - 9.8 \times \left[ {1,0,0;0,0, - 2.5} \right]\)), the power topology matrix for kinematic chain A-B-C is derived as

The unit power \({\varvec{P}_{{\varvec{{T}}}1}}\) of kinematic chain A-B-C is calculated as

Similarly, based on the end-effector load characteristics of the upper jaw (with \({{\varvec{W}}_{2\_n + 1}} = - 9.8 \times \left[ {1,0,0;0,4.35, - 2.5} \right]\)), the unit power \({\varvec{P}_{{\varvec{{T}}}2}}\) of kinematic chain A-B-D-E in the steel arch splicing mechanism is derived as

The unit power \({\varvec{P}_{\varvec{{T}}}}\) for the left-half mechanism can be expressed as

In the equation, the elements of matrix \({\varvec{P}_{\varvec{{T}}}}\) correspond to joints A, B, C, D, and E, respectively.

The unit power concentration index \(\varvec{SK_T}\) of the steel arch splicing mechanism is expressed as

The analysis concludes that joints A and D in the steel arch splicing mechanism are power-concentrated joints, necessitating closed-chain reinforcement.

Closed-chain design for power-concentrated joints

Joint A is responsible for adjusting the grasping angle of the steel arch splicing mechanism, bearing external loads in a cantilever beam configuration with suboptimal power transmission performance. Hydraulic actuation offers advantages including high power-to-weight ratio, superior load capacity, and rapid response, making it better suited for tunnel construction environments. Therefore, a hydraulic cylinder is installed at the end of the guide rail connected to joint A, forming a single-degree-of-freedom planar closed-chain structure as shown in Fig. 8. The linear motion of the hydraulic cylinder drives the rotation of joint A, thereby improving both its power transmission performance and structural stiffness.

For the closed-chain redesign of joint D, the compact structure of the grasping module makes it impractical to incorporate additional drive components. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the motion synchronization of each joint in the grasping module during operation and design its closed-chain structure by leveraging the existing joint arrangement and drive control system.

During the steel arch clamping operation of the grasping module, simultaneous control of the upper jaw movement, lower jaw movement, and rotation of link DE is required. When the mechanism approaches the steel arch, to prevent collision between the jaws and the arch, the upper jaw is controlled to move upward while the lower jaw moves downward, with link DE swinging downward to open the V-shaped opening. After the grasping module reaches the target position, the upper jaw moves downward while the lower jaw moves upward, with link DE swinging upward to close the V-shaped opening during the clamping operation.

The movements of these three components demonstrate inherent synchronization. To enhance grasping flexibility for different steel arch profiles, independent control of the upper and lower jaws is necessary. A mechanical linkage between the lower jaw motion and link DE’s rotation can be implemented to maintain grasping functionality while reducing control inputs and optimizing mechanism performance.

The lower jaw follows a linear motion path, while link DE rotates about point D. Therefore, a linkage mechanism must be designed to convert the lower jaw’s linear displacement into rotational motion of link DE. Based on the mechanism’s actual requirements, the following three linkage configurations (gear-rack, crank-slider, and slider-pivot) were selected as they represent the most widely adopted and thoroughly validated closed-chain mechanisms in heavy-duty engineering applications, particularly suited to the demanding requirements of tunnel construction.

(1) Gear-Rack Connection: Utilizing the principle of converting linear displacement to angular motion via gear-rack mechanism, the linkage is designed as shown in Fig. 9. A rack is fixed to the lower jaw, while a gear is installed at joint D and rigidly connected to link DE. The meshing engagement between the gear and rack ensures that the downward motion of the lower jaw drives the downward swing of link DE, achieving the opening of the V-shaped gap.

(2) Crank-Slider Connection: Based on the displacement-to-rotation conversion principle of crank-slider mechanisms, the linkage is designed as shown in Fig. 10. A connecting rod is hinged between the lower jaw position and an intermediate point on link DE, forming a crank-slider structure. The linear motion of lower jaw slider C is converted into rotational motion of link DE through this closed-chain configuration, achieving synchronized movement between the lower jaw and link DE.

(3) Slider-Pivot Connection: Leveraging the characteristics of revolute joints and sliders while incorporating the grasping module’s intrinsic features, the linkage is designed as shown in Fig. 11. The revolute joint on slider F enables its co-rotation with link DE, and the closed-chain structure converts the linear displacement of lower jaw slider C into rotational motion of link DE.

Through comparative analysis of the three linkage configurations, the following conclusions are drawn: The gear-rack transmission in Option 1 requires high installation precision, generates significant noise, has complex structure and manufacturing challenges, and exhibits limited load capacity and transmission accuracy due to its higher-pair mechanism. Given that steel arch splicing is a high-load operation, Option 1 is excluded. For Option 2’s crank-slider mechanism applied to the grasping module, the connecting rod must maintain sufficient length to ensure link DE reaches its target position, while the pressure angle must remain within (\(0^{\circ }\), \(90^{\circ }\)). The extended connecting rod may interfere with the lower jaw’s base during splicing operations, leading to rejection of Option 2. Option 3’s design directly connects the lower jaw’s end position to link DE through combined sliding and revolute joints, demonstrating superior performance through comprehensive kinematic analysis. The mechanism successfully completes all prescribed motion tasks without encountering singularities or collisions with steel arches, while maintaining transmission angles within the optimal [\(45^{\circ }\),\(90^{\circ }\)] range throughout the operational cycle. In addition, the institution also has the advantages of simple and reliable structure, easy manufacturing, and strong bearing capacity. The analysis confirms Option 3 as the optimal choice for structural optimization of the grasping module.

By applying the closed-chain design solutions for joint A and joint D to the steel arch splicing mechanism configuration shown in Fig. 6, the optimized mechanism structure is obtained as illustrated in Fig. 12. To ensure reliable grasping performance, a nylon block is installed on each jaw to establish direct contact with the steel arch, thereby providing effective anti-slip functionality. The upper jaw can be controlled independently. Through the active displacement compensation of the upper jaw, the system not only solves the grasping accuracy problems caused by wear of nylon blocks and manufacturing precision errors in steel arches, but also enables automatic adaptation to various steel arch profiles.

Optimized structure of the steel arch splicing mechanism (Fig. 12(b) was designed and rendered using SOLIDWORKS 2015; https://www.3ds.com/products-services/solidworks/).

Prototype experiment

To validate the design feasibility, a prototype of the steel arch splicing mechanism was manufactured as shown in Fig. 13. This prototype is deployed on the TBM to replace manual steel arch splicing operations. Closed-chain designs were implemented for Joints A and D to enhance the mechanism’s power transmission performance. The cylinder 1 is responsible for fine-tuning the grasping orientation, the cylinder 2 controls the docking operation of steel arches, the cylinder 3 drives the movement of the upper jaw, the cylinder 4 actuates the lower jaw.

The steel arch splicing mechanism prototype was used to perform grasping and docking operations on steel arches, as shown in Fig. 14. The steel arch splicing test consists of five sequential phases: During 0-10 seconds, hydraulic cylinder 3 retracts while hydraulic cylinder 4 extends to open the grasping module for preparation; from 10 to 30 seconds, the grasping module approaches the steel arch with hydraulic cylinder 1 making fine orientation adjustments; between 30 and 50 seconds, hydraulic cylinder 3 extends to raise the lower jaw while closing the grasping module; from 50 to 70 seconds, hydraulic cylinder 4 retracts to firmly secure the steel arch with the upper jaw; finally, during 70-90 seconds, hydraulic cylinder 2 extends to drive the grasping module, pulling the steel arch into docking position. The detailed control parameters for each hydraulic cylinder throughout the experiment are provided in Table 1.

The total splicing time was measured at 90 seconds, demonstrating high efficiency with a 4-8 times improvement over manual operations. During grasping, no collisions between the mechanism and steel arches or arch slippage occurred, confirming excellent grasping performance. The docking process achieved successful alignment and automatic locking between adjacent arches, proving effective splicing functionality. These results validate the feasibility of the designed steel arch splicing mechanism.

The load-to-weight ratio serves as a critical performance metric for mechanisms operating in heavy-load environments27. With an external load of 400 kg (combined weight of bilateral steel arches) acting on the splicing mechanism and the mechanism’s own weight of 335 kg, the calculated load-to-weight ratio reaches 1.19. All prototype components were manufactured by TBM production partner using their standard tunnel machinery parts, ensuring the reported 1.19 load-to-weight ratio reflects achievable performance in actual tunneling applications. Comparative data against conventional engineering mechanisms are presented in Table 2.

The steel arch splicing mechanism demonstrates superior load-to-weight ratio performance, significantly exceeding that of hybrid force-position robots, electric driven clamping mechanisms, and single-rod hydraulic systems. The higher ratio of the 5-DOF hybrid mechanism results from its jack-like structure which substantially increases load capacity, but simultaneously introduces structural complexity, elevated manufacturing costs, and reduced workspace - characteristics incompatible with steel arch splicing operations. Thus, the steel arch splicing mechanism proves well-suited for heavy-load tunneling applications, indirectly validating the accuracy of its power-concentrated joint analysis and closed-chain design research.

Conclusions

To address the heavy-load requirements of steel arch splicing tasks, this study proposes an automated steel arch splicing mechanism to replace manual operations, incorporating power-concentrated joint analysis and closed-chain improvements. The main conclusions are as follow.

(1) A novel bolt-free steel arch structure was developed, enabling rapid self-locking connections. This design facilitates robotic manipulation and automated arch splicing.

(2) The motion requirements of the splicing mechanism were established, guiding its configuration design.

(3) The unit power concentration index was employed to identify power-concentrated joints, which were then optimized through closed-chain designs to enhance the load-to-weight ratio.

(4) Prototype testing confirmed successful grasping and docking operations, achieving 4–8 times higher efficiency than manual methods and a 1.19 load-to-weight ratio, demonstrating suitability for heavy-duty tunneling applications.

This work presents a topological optimization methodology for structural enhancement, focusing on structural innovation rather than geometric details. Future work will develop dimensional optimization and control systems for steel splicing mechanisms, while extending the approach to parallel/hybrid applications.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Zhang, Y., Gong, G., Yang, H., Li, J. & Jing, L. From tunnel boring machine to tunnel boring robot: perspectives on intelligent shield machine and its smart operation. J. Zhejiang Univ. A 25, 357–381 (2024).

Zhou, Z., Li, Z., Tan, Z., Lei, K. & Zhang, L. Optimized decision-making for tunnel boring machine control parameters. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 1–21 (2025).

Li, X., Li, H., Du, S., Jing, L. & Li, P. Cross-project utilisation of tunnel boring machine (tbm) construction data: A case study using big data from yin-song diversion project in china. Georisk: Assess. Manag. Risk for Eng. Syst. Geohazards 17, 127–147 (2023).

Lyu, X., Chen, Y., Liao, S. & Fernandez-Steeger, T. M. Wear prediction and mechanism study of tunnel boring machine disc cutter breaking in hard soft rock considering thermal effect. Appl. Sci. 15 (2025).

Jia, L. et al. Kinematics and spatial structure analysis of tbm gunite robot based on d-h parameter method. Sci. Reports 14, 13649 (2024).

Yang, T. Investigation on disaster mechanism of diversion tunnel induced by gripper tbm in hydrokarst erosion stratum and engineering measures. Buildings 14, 625 (2024).

Li, X. et al. A data driven real-time perception method of rock condition in tbm construction. Can. Geotech. J. 61, 1018–1034 (2023).

Ji, M. et al. Stability analysis of tunnel surrounding rock when tbm passes through fracture zones with different deterioration levels and dip angles. Sustainability 15, 5243 (2023).

Liang, F., Pei, C., Luo, W., You, M. & Tan, F. Numerical simulation analysis of different excavation parameters for tbm 3d disc cutters based on the discrete element method. Appl. Sci. 15 (2025).

Li, X., Wu, L.-J., Wang, Y.-J. & Li, J.-H. Rock fragmentation indexes reflecting rock mass quality based on real-time data of tbm tunnelling. Sci. Reports 13, 10420 (2023).

Lu, W. et al. Study on mechanical properties of composite support structures in tbm tunnel under squeezing soft rock conditions. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 144, (2024).

Lin, P., Kang, J. & Xu, Z. A new optimization method of initial support for tbm tunnel crossing fault zone based on deformation control contribution. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 84, 90 (2025).

Yang, Y. et al. Research on prevention and control technology of classified rockburst in tbm construction of deeply buried tunnels. Sci. reports 14, 333 (2024).

Kang, J., Xie, H., Lin, P. & Xu, Z. An integrated determination method of optimal supporting time against tbm jamming. Eng. Fail. Analysis 162, (2024).

Chen, Y., Gong, G., Zhang, Y. & Wu, W. Development of a novel muck removal hydraulic manipulator for automated steel arch assembly of tunnel boring machine. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 46, 403 (2024).

He, Y. et al. A \(\phi\) 6-m tunnel boring machine steel arch splicing manipulator. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 35, 31 (2022).

He, Y., Liu, F., Xu, Z. & Yang, M. Tree-type hybrid mechanism configuration synthesis based on modular decomposition and power-concentrated joint closed-loop design. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 52, 10539–10554 (2024).

Chen, Y., Gong, G., Zhou, X., Zhang, Y. & Wu, W. Backstepping based trajectory tracking control of a tbm steel arch splicing manipulator. Int. J. Control. Autom. Syst. 22, 648–660 (2024).

Chan, T.-C., Ullah, A., Roy, B. & Chang, S. Finite element analysis and structure optimization of a gantry-type high-precision machine tool. Sci. Reports 13, 13006 (2023).

Chan, T.-C., Reddy, S. V. V. S., Ullah, A. & Roy, B. Effect of spatial moving structure and topology optimization of the cnc turning machine tools. The Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 129, 2969–2987 (2023).

Ullah, A., Chan, T.-C. & Chang, S.-L. Enhancing five-axis machine tool performance through esg-based design optimization. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. Technol. 12, 245–262 (2025).

Wu, J., Zhang, B. & Wang, L. Optimum design and performance comparison of a redundantly actuated solar tracker and its nonredundant counterpart. Sol. Energy 127, 36–47 (2016).

Laus, L., Simas, H. & Martins, D. Machine efficiency determined using graph and screw theories with application in robotics. Mech. Mach. Theory 148, (2020).

Yuan, B., Wang, H., Yuan, H., Dai, J. & Pan, X. Mobility and applied load-oriented mechanism configuration design method. Mech. Mach. Theory 182, (2023).

Van, L. C. F. The ubiquitous kronecker product. J. computational applied mathematics 13, 85–100 (2000).

Hadamard products and binomial ideals. J. Pure Appl. Algebr. 228, 107568 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Type synthesis of a novel 4-degrees-of-freedom parallel bipedal mechanism for walking robot. Adv. Intell. Syst. 6, 2300384 (2024).

Han, M., Lian, W., Liu, J., Yang, D. & Li, T. Hybrid force-position coordinated control of a parallel mechanism with the number of redundant actuators equal to its dof. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C: J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 238, 11081–11096 (2024).

Tang, M., Wang, S., Gu, Y. & Liang, Q. Operation safety analysis and protection of hot-line working robot in strong electric field. In 2019 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Renewable Energy and Power Engineering (REPE), 15–20 (IEEE, 2019).

Banthia, V. Haptic-enabled teleoperation of single-rod hydraulic manipulators. Ph.D. thesis, The University of Manitoba (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (Grant Nos. 2025J08277, 2025J08221), Department of Education, Fujian Province (Grant Nos. JAT241113, JAT241066), Minjiang University (Grant Nos. 30804332, MFK25013), Fujian University of Technology (Grant No. GY-Z24008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

He designed the study and wrote the manuscript, Yu reviewed and edited the manuscript, Xu performed the experiments, Zheng analyzed the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all human participants. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All experimental protocols were approved by the National Construction and Urban Construction Machinery Quality Supervision and Inspection Center (China).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, X., He, Y., Xu, Z. et al. Analysis and reinforcement design of power concentrated joints in steel arch splicing mechanisms for tunnel boring machines. Sci Rep 15, 39401 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17696-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17696-6