Abstract

Job stress by effort-reward imbalance (ERI) is a predictor of burnout. It is associated with inflammation and is a forerunner of distal outcomes, including mortality. Sleep quality, an important association between job stress and inflammation, has not been extensively studied. A cross-sectional study was conducted to examine the relationship between job stress, subjective sleep quality, and inflammation among female nurses. As the primary outcome measure, a composite inflammation score was constructed from five interleukins (IL-6, 8, 10, 1β, TNF-α). Among fifty participants (mean age 32 ± 7 years, work experience 105 ± 8 months), there was poor sleep quality among the high ERI group (p = 0.021). Overcommitment (OC), an intrinsic component of the ERI, was related to poor sleep quality (β = 0.21, p = 0.025). High OC (β = 2.4, p = 0.025) and increased sleep latency (β = 8.3, p = 0.027) were associated with elevated inflammation. There was a significant interaction between ERI and OC on inflammation (β = 5.186, p = 0.017) and conditional effects of ERI on OC to inflammation only in the high ERI group (p = 0.002), not in the low ERI group (p = 0.839). Composite inflammation scores from inflammatory markers may be potential indicators of adverse outcomes in burnout studies among healthcare workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Job stress is a predictor of burnout, is associated with adverse physical health, and increases the risk for stress-related mental disorders1,2,3,4. The effort-reward imbalance theory of job stress has two components, an extrinsic effort-reward imbalance (ERI) and an intrinsic overcommitment (OC) component5. ERI manifests when social reciprocity is breached at work. That is, when the efforts expended are perceived to be high as opposed to the low rewards reaped at work, strong negative emotions are evoked along with stress reactions. Healthcare workers are more prone to ERI owing to intrinsic job demands, which were only heightened during the COVID pandemic6,7. Importantly, high job stress from ERI among nurses is associated with depression propensity and found to be associated with burnout8,9. Both ERI and OC are considered high risk for cardiovascular diseases and heightened hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal activity10,11. Despite these consistent associations, biological correlates linking job stress to these distal outcomes are mainly lacking. To develop effective targeted interventions that will help disengage the progression of job stress to disease states and premature deaths, we need a better understanding of biological objective correlates of job stress.

Inflammation is a potential biological objective correlate to both job stress and distal outcomes, including death. Job stress is a crucial antecedent to heightened inflammatory states12. Acute and chronic job stress is associated with low immunity and specific cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-83,13,14,15. This relationship among ERI, OC, and cytokines is highlighted by recent meta-analytic evidence16. On the other hand, studies assessing healthcare workers’ health and patient outcomes have revealed that increased cytokines are associated with medical errors17. Importantly, inflammation is found to be a forerunner of mortality18. Thus, inflammation is an essential and modifiable link between job stress and the health outcomes of healthcare professionals and their care. However, inflammation can be a more complex correlate, challenging to tamed by a reductionist view. Thus, we need additional related factors to explain the variance in job stress-associated inflammation.

Sleep quality is related to job stress, and inflammation and sex differences play an important role in these interrelationships. A recent study suggested poor sleep quality among nurses and increased insomnia risk in healthcare workers during the COVID outbreak19. On the other end, poor sleep quality is associated with biological aging, and depression risks. Poor health outcomes related to sleep disturbances are hypothesized to be contribute by activating inflammation20. Hence, identifying specific sleep components related to inflammation can provide insights into developing interventions. Such interventions can target malleable sleep regions, thus delinking job stress and distal outcomes related to stress. Recently, poor sleep among females has been reported to be negatively associated with reproductive outcomes21. Additionally, the interrelation among stress, sleep, and inflammation is understood to be more robust in females20. As nurses are more prone to ERI than doctors and more than 80% of nurses in India are females, we chose to conduct this study in female nurses22,23. Sleep was assessed using self-reported measures, which reflect participants’ perceived rather than objectively measured sleep quality.

Traditionally, studies have tested the main and interactive effects of ERI and OC. Less is known about whether stress moderates the relation between OC and related outcomes. This notion stems from recent findings on OC responsive to different work contexts and is a potential antecedent and a known predictor of ERI24,25. Thus, we aimed to explore the conditional effects of ERI on OC and inflammation. Also, to understand to what extent job stress correlated with inflammation, we combined select inflammatory markers, IL6, IL8, IL10, IL1 beta, and TNF-alpha, known to be associated with ERI and OC and constructed a composite score16,26. The composite scoring approach reduces the burden of multiple testing, and importantly, composite inflammatory scores are predictive of mortality as evidenced by meta-analyses18.

For this study, we had two specific objectives.

-

1.

To what extent do job stress and sleep quality explain the variance in inflammation?

-

2.

Considering the antecedent effects of OC, what are the conditional effects of ERI in the relation between OC and inflammation?

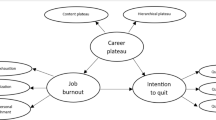

By understanding these interrelations, we can design better-targeted interventions to improve nurses’ health and, thus, indirectly improve patient safety. The conceptual depiction of the study is provided in Fig. 1.

Results

To understand the interrelationships between job stress along with an intrinsic overcommitment (OC) component, sleep quality, and inflammation, we first examined to what extent job stress (Effort-Reward Imbalance (ERI) and OC) is related to sleep quality. Then we examined to what extent job stress and sleep quality explained the variance in inflammation. Finally, we explored whether there are any conditional effects of ERI on the relationship between OC and inflammation.

Our study group comprised 50 participants, who were female nurses with a mean age of 32 (± 7) years and a mean of 14.98 (± 0.5) years of education. The average work experience of the sample was 105 (± 77) months, that is approximately 9 years. The participants worked approximately 45 h a week (± 5) and had 2-night duties (± 3) on average in the past month. This significantly differed among ERI groups; those with high ERI had a higher number of night duties. All descriptive statistics are depicted in Table 1. Those who had a low ERI had better recovery and better wellbeing. No significant differences among the ERI groups were observed for interleukin levels or composite inflammation scores.

Supplementary Table 1 describes the obesity and overweight parameters of this sample, namely body mass index (BMI), waist-hip ratio (WHR), and percentage body fat (PBF). About 14% were overweight, and 60% were obese, based on the Indian Consensus Group27. Only 38% indulged in some physical activity regularly. Of those engaged, the mean exercise minutes per week was 66 min. No significant relationship was observed between BMI, PBF, or WHR and inflammation or ERI.

To understand whether job stress affected sleep, we looked for differential distributions among sleep quality and ERI groups. We observed a significant association between sleep quality and stress groups,\(\:{\chi\:}^{2}\)(1) = 4.08, p = 0.043. From Table 1, we can infer that the majority of the low-stress group had good quality sleep, and a majority of the highly-stressed group had poorer sleep quality. We ran correlations among job stress, sleep, and inflammation scores to examine the intercorrelations among the studied variables (Supplementary Fig. 1). On exploration of the correlation matrix, sleep quality was positively associated with OC scores and negatively associated with wellbeing. OC was negatively associated with recovery scores and the psychological detachment facet of recovery scores, suggesting that high OC was associated with poor recovery especially poor psychological detachment from work.

High ERI and high OC were associated with poor sleep quality

To understand how much OC and wellbeing explain variance in sleep quality, we performed regression analysis with these two variables as predictors. We found that approximately 22% of the variance in sleep quality was explained (Supplementary Table 2). High OC was associated with higher sleep scores, indicating poorer sleep quality. In contrast, wellbeing had a negative relationship with sleep, suggesting that increased wellbeing was associated with good sleep quality.

High overcommitment and increased sleep latency were associated with high inflammation

To understand how much ERI, sleep, and OC explain variance in inflammation, we ran regression models with ERI, OC, global sleep quality, and sleep latency as predictors and composite inflammation score as the outcome. We chose latency because of the significant relationship between latency and inflammation, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1.

We found that the model with sleep latency and OC explained 20% of the variance in inflammation scores. Both sleep latency and OC were positively associated with inflammation, meaning that increased sleep latency and high OC were associated with elevated inflammation. This is tabulated in Table 2. To test the robustness of our findings, we included age, work experience, BMI, and night duties as covariates in supplementary regression models (see Supplementary Table 3). These adjustments did not change the strength or significance of the main predictors.

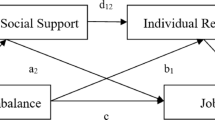

ERI moderated the relationship between OC and inflammation

Finally, we ran a moderation analysis to identify if there are any conditional effects of ERI on the relation between OC and inflammation. We conducted moderation analysis using the PROCESS function in R with model 128. OC was set as a predictor (X), inflammation score was set as the outcome (Y), and ERI was considered as the moderator (W). Moderator ERI was considered with two levels; high and low ERI, based on a median cutoff (median ERI = 0.833). We observed significant conditional effects of stress on the relation between OC and inflammation; that is, only among those with a high ERI, increasing OC was associated with a steep increase in inflammation. There was a significant main effect found between ERI and composite inflammation score, b= −85.88, 95% CI [−150.78, −20.98], t=−2.669, p = 0.010, and a nonsignificant main effect of OC on inflammation score b = 0.276, 95% CI [−2.46,3.01], t = 0.204, p = 0.839. There was a significant interaction found by ERI on OC and inflammation, b = 5.186, 95% CI [0.97,9.39], t = 2.482, p = 0.017. It was found that participants who reported higher than median levels of ERI experienced a more significant effect of OC on inflammation (b = 5.462, 95% CI [2.158,8.765], t = 3.334, p = 0.002) when compared to median or lower than median levels of ERI (b = 0.276, 95% CI [−2.457,3.009], t = 0.204, p = 0.839). From these results, it can be deduced that ERI moderates the effect of OC on inflammation. The moderation analysis is depicted in Table 3; Fig. 2.

Discussion

We examined to what extent inflammation is a biological correlate of sleep quality and job stress components; effort-reward imbalance (ERI) and overcommitment (OC). We hypothesized that high ERI, OC, and poor sleep quality would be associated with high inflammation. We constructed a composite inflammation score from five interleukins – IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-1beta, and TNF-alpha - and studied its association with ERI, OC, and sleep quality in female nurses working in a tertiary care hospital. We found that ERI and OC were associated with poor sleep quality and that OC and sleep latency were associated with increased inflammation. In particular, those experiencing a high ERI had more pronounced inflammation associated with OC characteristics.

We observed that OC and sleep latency explained the maximum variance in our primary outcome of interest, inflammation. This is evidenced by the R squared values in the regression models describing inflammation composite scores. Recent work highlighted that OC is highly similar to work-related rumination and that OC and psychological detachment are closely related29. Thus, we hypothesize that individuals who overcommit to work may find it difficult to detach from work and ruminate about work, thus affecting sleep latency. This notion is asserted by our finding in this study that OC was negatively associated with psychological detachment, a facet of recovery from work. However, this hypothesis needs to be tested by mediation models in longitudinal and intensive longitudinal designs for temporal effects. It was recently noted that sleep helps reset inflammatory activity from the stress and threats encountered during the day30. In these lines, we speculate that increased sleep latency may be a barrier to resetting inflammation associated with job stress. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to find an association between sleep latency and inflammation while assessing job stress models. This facet of global sleep quality can be a potential area for intervention while targeting job stress. Future studies can test interventions targeting reduced sleep latency to explore whether job stress-associated inflammation can be decoupled.

We observed that the association between OC and inflammation was more pronounced in those with a high ERI. This is evidenced by the moderation analysis, where the relation between OC and inflammation is significant only when there is a high ERI. Holding this notion, those with high ERI can be targeted for mitigating OC-associated inflammation in low-resource settings instead of blanket interventions for all those with high OC. However, this is limited by high and low ERI levels being drawn for this specific sample. Future studies should develop cutoff scores when exploring potential outcomes of interest. The finding that OC is associated with inflammation risk in those with high ERI also needs to be tested in other healthcare workers and occupations where ERI may be encountered.

We also observed that both ERI and OC were associated with poor sleep quality. This inference was drawn from differential distributions of ERI and sleep quality groups and regression with OC and wellbeing, explaining significant variance in sleep quality. This is consistent with previous findings that job stress is associated with poor sleep quality in nurses and healthcare workers31. This finding is significant because poor sleep can drive many downstream ill effects on physical and mental health. Future intervention studies should plan to target sleep quality and assess whether it reduces ERI and OC-associated consequences. Alternatively, helping participants to balance their efforts and rewards and providing secondary interventions for those with high OC can be beneficial. Promoting recovery activities to improve sleep can be tried, as it is known to combat the effects of poor sleep on depression, as noted by Ding et al.32. In practice, nurses can be provided a simple OC assessment during recruitment, and those overcommitted to work can be screened for sleep quality periodically. As OC, sleep quality, and quality of life are intertwined in our findings, nurses can benefit in their quality of life as well if sleep quality can be addressed at the right times. This may help to prevent transitioning to burnout when encountering ERI during work. As burnout is identified as a potential factor for intention to leave work33, targeting the transition to burnout can positively boost employee retention.

We noted that the prevalence of obesity and overweight was higher in this sample than in the Indian females in the general population34. This likely reflects broader demographic trends, including the increasing burden of obesity among urban women from higher socioeconomic strata in India35,36. Additionally, in this study, those who were indulging in physical activity did not meet the WHO guidelines of physical activity (150 min per week), as the average was 66 min of activity per week. Although we did not find any significant associations among obesity/overweight parameters such as BMI, percentage body fat, or waist-hip ratio with inflammation, one cannot undermine the significant association between obesity, inflammation, and cardiovascular risks. Hence larger samples may be needed to test whether physical activity will reduce job stress-associated inflammation. Furthermore, one study showed that resistance training reduced sleep latency and improved anti-inflammatory cytokines37. This can be leveraged in future interventions targeting obesity and sleep latency to see changes in inflammation associated with job stress. Studies have mentioned that women with health-promoting lifestyles can achieve health-enhancing physical activity levels and improve sleep38. Hence, an overall improvement in a healthy lifestyle, including physical activity, can benefit nurses with both obesity and sleep problems.

This pilot study has several limitations that warrant consideration. The small sample size limits generalizability. However, as a pilot study, our goal was to explore patterns and feasibility, which this sample size supports. Future studies with larger cohorts can validate and extend these findings. We restricted the sample to pre-menopausal women to reduce hormonal variability in inflammatory and sleep-related outcomes. While this enhances internal consistency, it limits applicability to older nurses. Future research should include menopausal status as a covariate to improve representativeness. The high prevalence of overweight and obesity in our sample could have influenced sleep and inflammation associations. Although this reflects broader demographic trends among Indian women, we did not stratify analyses by weight category. Future studies should examine obesity-related moderators and physical activity in more depth. Sleep quality was assessed through self-reported measures, which may introduce cognitive bias, especially under stress. To partly address this, validated subjective instruments and their subscales to understand relationships among studied variables. Future studies, if complemented with objective assessments such as actigraphy, may provide more nuanced insights into sleep quality. While we collected the number of night duties, we did not capture detailed shift classifications (e.g., early morning, rotating). This limits our ability to differentiate shift work effects. Future work using finer-grained shift categorization can shed more light of these effects. Sleep disorders such as apnea or cumulative stress history were not assessed and may influence inflammation and can be incorporated in future designs. Finally, although the composite inflammation score was constructed from within-sample distributions, limiting direct comparability across cohorts, this approach reduced multiple testing and provided a robust summary of systemic inflammation. Future longitudinal studies with larger, more diverse samples and objective physiological measurements will be critical to validate and build upon these initial findings. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study attempting to correlate job stress and sleep quality with inflammation composite scores, which is a potential forerunner to mortality.

In conclusion, our study provides a foundational step toward understanding how occupational stress and sleep disturbances interact to influence inflammation in nurses. It highlights subjective sleep quality as a potential modifiable target, particularly among individuals experiencing high ERI and overcommitment, and underscores the need for integrated interventions to mitigate overcommitment-associated inflammation in job stress and burnout.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (ICMR-National Institute of Occupational Health) and followed the Declaration of Helsinki (1975). Flyers inviting potential participants to attend induction meetings were displayed at a nearby tertiary care hospital. The induction meetings were structured to inform the attendees about the need for the study and the significance of this research. We invited female nurses involved in clinical work for at least six months to participate in the study. To reduce physiological variability associated with menopausal transition, which is known to influence both inflammatory markers and sleep, we restricted our sample to pre-menopausal women. We also excluded any participant involved in night duties for more than 15 days in the past month. We also excluded participants with any history of untreated major physical and psychiatric comorbidities. Considering the ubiquity of COVID infections and their potential to affect inflammation, we inquired about the COVID infection status for all the participants. None of our participants reported COVID-19 in the past six months. The flow of participants is shown in Fig. 3.

We used convenience sampling to recruit 50 participants from September to November 2022. The primary aim of the pilot study was to evaluate the feasibility of the research design, and a sample size of 50 was deemed sufficient to gather enough information to inform the design of future studies. Approximately 80% of those who attended the meetings expressed interest in participating in the study. After considering inclusion and exclusion criteria, written informed consent was obtained. We interviewed and sampled 50 participants who were included in the analysis. All interviews were conducted at the workplace.

Demographics and work-related measures

Information on the participants’ age, marital status, work hours, months of work experience, and number of night duties in the past three months were captured. We inquired about both current and past smoking and alcohol use, and none of the participants reported a history of either. We assessed physical activity by inquiring whether participants engaged in any physical activity consistently; if physically active, the type of exercise, its frequency in a week and intensity of exercise were further probed. From this information, we calculated physically active minutes in the past week by multiplying activity minutes and the number of days in a week undertaking activity.

The following questionnaires were administered.

Job stress assessment

Job stress was assessed by the effort-reward imbalance8 questionnaire, which captures self-reported scales of effort and reward from 16 questions marked on a 4-point Likert scale(strongly disagree, disagree, agree, and strongly agree). ERI also has six separate questions to assess overcommitment graded similarly. The effort and reward scores obtained from the 16-item questionnaire were used to compute the effort-reward ratio. For this, the E/R*c formula was used, where E is the total effort score, R is the total reward score, and c is a correction factor for an unequal number of effort and reward items. We used a 16-item questionnaire where effort was assessed by six questions and reward by 10, and the correction factor was 0.6. Though many studies report effort-reward imbalance as ER ratio greater than 1, we treated ER-ratio as a continuous score. For categorical comparisons, we categorized the ER-ratio score by median to derive low and high stress groups. This is because ER = 1 is not representative of a clinically validated threshold and using it as a continuous or quantile-based categorization is preferred39. High scores in the ER-ratio mean greater effort-reward imbalance, considered job stress in this study. Overcommitment scores capture the personal coping pattern from work; higher scores indicate high overcommitment to work. The coefficient omega of reliability was 0.87 for ERI and 0.7 for OC.

Recovery from work

Recovery was assessed by the Recovery Experience Questionnaire (REQ)40. This is a 16-item questionnaire that assesses how participants recover in their free time after work. REQ is a self-report scale marked in a 5-item Likert scale response (strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree). High scores indicate better recovery. The REQ has four facets: control, mastery, psychological detachment, and relaxation. The coefficient omega of reliability was 0.8 for the REQ.

Sleep quality

Sleep for the past month was assessed by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)41, which is a 9-item questionnaire. The responses were coded from a 0–3 scale, and the cumulative scores ranged from 0 to 21. High scores indicate poor sleep quality. A cutoff of 5 was considered above which the sleep quality was graded to be poor per instructions in the questionnaire. The PSQI assesses sleep in the following seven domains: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, sleep medication aids, and daytime dysfunction.

Well-being

Well-being for the past two weeks was assessed by the WHO-5 Well-being Index, a 5-item questionnaire42. This captures the experience of positive emotions graded from 0 to 5, with 0 meaning felt at no time and 5 meaning experienced at all times. Higher scores indicate better well-being. The total scores range from 0 to 25 multiplied by 4 to yield scores ranging from 0 to 100; 0% is the worst quality of life, and 100% is the best possible quality of life. A cutoff of 50% was considered below, which the quality of life was graded poor. The coefficient omega of reliability was 0.85 for the WHO-wellbeing 5 index.

Blood sampling and ELISA for cytokines

All participants were sampled for 5 ml of venous blood samples under strict aseptic precautions. Blood was collected in serum separation tubes. After collection, the samples were centrifuged to separate serum, and serum samples were stored at −80 degrees Celsius until further analysis. Serum was tested for IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL1 beta, and TNF-alpha obtained from Invitrogen (Thermofisher Scientific), USA per the manufacturer’s instructions. All the samples were run in duplicates by a trained technician. Raw data for all five cytokines were tabulated to construct a composite inflammation score.

Construction of composite scores

All the raw values of five interleukins were converted to z scores by subtracting individual scores from the mean values and dividing them by the standard deviation of cytokines. Only for IL-10 with anti-inflammatory activity, inverse sign of z-scores were considered, that is, those who were 2 SD more than the mean scores of IL-10 were scored (−2). All the z scores were summed up for all the participants to arrive at one single value. These summed-up z scores were converted to t-scores for better interpretation. For this, we multiplied the sum value by ten and added 50. This is a valid method of calculating the composite scores described earlier43,44.

Anthropometry and body composition

Anthropometry measurements and body composition measures such as BMI, WHR and PBF were analyzed using an InBody 270 analyzer (Cerritos, CA, USA)45. This is a non-invasive and highly accurate device using bioelectrical impedance analysis to measure the body composition. The body composition analysis was performed according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Statistical analysis

Outliers were considered true values and were included in the analysis. All results are tabulated as the mean and SD values unless mentioned otherwise. Assumptions of normality were tested with Shapiro’s test. We tested group differences for high (n = 25) and low (n = 25) ERI groups on all demographics, work-related and sleep, recovery and scores, and inflammation scores with the Wilcoxon rank sum test and Fisher’s exact tests for continuous and nominal variables, respectively. All variables were run to test Spearman correlation and to construct a correlation matrix. Linear regression was used to test to what extent predictor variables explain variance in the dependent variables. Only variables that showed significant or near-significant differences between ERI groups in univariate comparisons were considered for inclusion in the regression models. R-squared values were used to denote percentage variance in the outcome variable. Moderator analysis was conducted by the PROCESS function in R28. Conditional effects were considered significant if the upper and lower confidence intervals did not include zero. Statistical tests were considered significant if p values were < 0.05. All analyses were conducted in R46 and plots and figures were generated with ggplot2 package47.

Conceptual diagram of the study. Panel (a) represents the concept and overview of research questions. The shaded area encompasses the interlinks investigated in this study. The dotted dash line from inflammation to distal outcomes depicts the potential link described in the literature. Panel (b) depicts the moderator role of ERI to be tested in the relation between OC and inflammation (conceptual model). ERI = Effort-reward imbalance; OC = Overcommitment from ERI theory of job stress.

Conditional effects of ERI on overcommitment and inflammation. This figure is a visual representation of the moderator effects of ERI in the relation between OC and composite inflammation scores. The blue line represents the high ERI group, and the orange represents the low ERI group. High and low ERI groups were derived from the median cutoff of ERI (0.833). OC scores on the X-axis range from 6–30, and inflammation scores on the Y-axis range from 0-100. ERI = Effort-Reward Imbalance; OC = Overcommitment.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article can be made available by requests directly to the corresponding authors.

References

Zhou, S. et al. The relationship between occupational stress and job burnout among female manufacturing workers in guangdong, china: a cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 20208 (2022).

van der Molen, H. F., Nieuwenhuijsen, K., Frings-Dresen, M. H. W. & de Groene, G. Work-related psychosocial risk factors for stress-related mental disorders: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 10 (7), e034849 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Chronic insomnia is associated with higher Circulating Interleukin-8 in patients with atherosclerotic cerebral small vessel disease. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 12, 93–99 (2020).

Yang, B. et al. Association between insomnia and job stress: a meta-analysis. Sleep. Breath. 22 (4), 1221–1231 (2018).

Siegrist, J. The Effort–Reward Imbalance Model. The Handbook of Stress and Healthp. 24–35 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2017).

Ge, J. et al. Effects of effort-reward imbalance, job satisfaction, and work engagement on self-rated health among healthcare workers. BMC Public. Health. 21 (1), 195 (2021).

Jensen, N., Lund, C. & Abrahams, Z. Exploring effort–reward imbalance and professional quality of life among health workers in cape town, South africa: a mixed-methods study. Global Health Res. Policy. 7 (1), 7 (2022).

Bakker, A. B., Killmer, C. H., Siegrist, J. & Schaufeli, W. B. Effort-reward imbalance and burnout among nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 31 (4), 884–891 (2000).

Kikuchi, Y. et al. Effort-reward imbalance and depressive state in nurses. Occup. Med. 60 (3), 231–233 (2009).

Eddy, P., Wertheim, E. H., Kingsley, M. & Wright, B. J. Associations between the effort-reward imbalance model of workplace stress and indices of cardiovascular health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 83, 252–266 (2017).

Bellingrath, S. & Kudielka, B. M. Effort-reward-imbalance and overcommitment are associated with hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis responses to acute psychosocial stress in healthy working schoolteachers. Psychoneuroendocrinology 33 (10), 1335–1343 (2008).

Duchaine, C. S. et al. Psychosocial stressors at work and inflammatory biomarkers: prospective Quebec study on work and health. Psychoneuroendocrinology 133, 105400 (2021).

Bellingrath, S., Rohleder, N. & Kudielka, B. M. Healthy working school teachers with high effort-reward-imbalance and overcommitment show increased pro-inflammatory immune activity and a dampened innate immune defence. Brain. Behav. Immun. 24 (8), 1332–1339 (2010).

Arnetz, J., Sudan, S., Goetz, C., Counts, S. & Arnetz, B. Nurse work environment and stress biomarkers: possible implications for patient outcomes. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 61 (8), 676 (2019).

Dutheil, F. et al. Urinary Interleukin-8 is a biomarker of stress in emergency physicians, especially with advancing Age — The JOBSTRESS* randomized trial. PLoS One. 8 (8), e71658 (2013).

Eddy, P., Heckenberg, R., Wertheim, E. H., Kent, S. & Wright, B. J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effort-reward imbalance model of workplace stress with indicators of immune function. J. Psychosom. Res. 91, 1–8 (2016).

Arnetz, B. B., Lewalski, P., Arnetz, J., Breejen, K. & Przyklenk, K. Examining self-reported and biological stress and near misses among emergency medicine residents: a single-centre cross-sectional assessment in the USA. BMJ Open. 7 (8), e016479 (2017).

Bonaccio, M. et al. A score of low-grade inflammation and risk of mortality: prospective findings from the Moli-sani study. Haematologica 101 (11), 1434–1441 (2016).

Gao, C., Wang, L., Tian, X. & Song, G. M. Sleep quality and the associated factors among in-hospital nursing assistants in general hospital: A cross-sectional study. Heliyon 8 (5), e09393 (2022).

Irwin, M. R. Sleep and inflammation: partners in sickness and in health. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 19 (11), 702–715 (2019).

Reschini, M. et al. Women’s quality of sleep and in vitro fertilization success. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 17477 (2022).

Birgit, E., Gunnevi, S. & Ann, O. Work experiences among nurses and physicians in the beginning of their professional careers - analyses using the effort-reward imbalance model. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 27 (1), 36–43 (2012).

Karan, A. et al. Size, composition and distribution of health workforce in india: why, and where to invest? Hum. Resour. Health. 19 (1), 39 (2021).

Feldt, T. et al. Overcommitment as a predictor of effort–reward imbalance: evidence from an 8-year follow-up study. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health. 42 (4), 309–319 (2016).

du Prel, J. B. et al. Work-Related overcommitment: is it a state or a Trait? – Results from the Swedish WOLF-Study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44 (suppl_1), i263 (2015).

Furman, D. et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat. Med. 25 (12), 1822–1832 (2019).

Misra, A. Ethnic-Specific criteria for classification of body mass index: A perspective for Asian Indians and American diabetes association position statement. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 17 (9), 667–671 (2015).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction To Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis, Second Edition: A Regression-Based Approach, 713 (Guilford, 2017).

Weigelt, O. et al. Too Committed To Switch off – Capturing and Organizing the Full Range of Work-Related Rumination from Detachment To Overcommitment (Preprints, 2023).

Besedovsky, L., Lange, T. & Haack, M. The Sleep-Immune crosstalk in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 99 (3), 1325–1380 (2019).

Huang, Q., Tian, C. & Zeng, X. T. Poor sleep quality in nurses working or having worked night shifts: A Cross-Sectional study. Front. Neurosci. 15, 638973 (2021).

Ding, J. et al. Recovery experience as the mediating factor in the relationship between sleep disturbance and depressive symptoms among female nurses in Chinese public hospitals: A structural equation modeling analysis. PRBM 13, 303–311 (2020).

Hazeen Fathima, M. & Umarani, C. A study on the impact of role stress on engineer intention to leave in Indian construction firms. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 17576 (2022).

Kumar, P., Mangla, S. & Kundu, S. Inequalities in overweight and obesity among reproductive age group women in india: evidence from National family health survey (2015–16). BMC Women’s Health. 22 (1), 205 (2022).

Kumar, R., Kumar, A., Rajpal, S. & Joe, W. Underweight and overweight prevalence among Indian women. In Atlas of Gender and Health Inequalities in India Vol. 16 (ed. Guilmoto, C. Z.) 17–27 (Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023).

Verma, M., Das, M., Sharma, P., Kapoor, N. & Kalra, S. Epidemiology of overweight and obesity in Indian adults - A secondary data analysis of the National family health surveys. Diabetes Metabolic Syndrome: Clin. Res. Reviews. 15, 102166 (2021).

de Sá Souza, H. et al. Resistance training improves sleep and Anti-Inflammatory parameters in sarcopenic older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19 (23), 16322 (2022).

Al-Sharif, F. M. & El-Kader, S. M. A. Inflammatory cytokines and sleep parameters response to life style intervention in subjects with obese chronic insomnia syndrome. Afr. Health Sci. 21 (3), 1223–1229 (2021).

Siegrist, J., Li, J. & Montano, D. Psychometric properties of the Effort-Reward Imbalance Questionnaire.

Sonnentag, S. & Fritz, C. The recovery experience questionnaire: development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 12 (3), 204–221 (2007).

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R. & Kupfer, D. J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28 (2), 193–213 (1989).

Wellbeing measures in. primary health care/the DEPCARE project.

Soundararajan, S., Narayanan, G., Agrawal, A. & Murthy, P. P. Profile and Short-term treatment outcome in patients with alcohol dependence: A study from South India. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 39 (2), 169–175 (2017).

Ward, S. E. et al. A randomized trial of a representational intervention for cancer pain: does targeting the dyad make a difference?? Health Psychol. 28 (5), 588–597 (2009).

Böhm, A. & Heitmann, B. L. The use of bioelectrical impedance analysis for body composition in epidemiological studies. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 67 (Suppl 1), S79–85 (2013).

Team, R. C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 4.2.2 Ed (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2022).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis: (Springer, 2016).

Acknowledgements

We deeply acknowledge all the participants who generously provided their time and enthusiastically participated in this study. We also acknowledge our technical staff, Mr. Vishal, Mr. Praveen, Mr. Sanjay, Ms. Dharti, Mr. Mehul, Mr. Mansuri, Mr. Bhavesh, Mr. Vikki, and Mr. Umesh for assisting with data collection and laboratory work and ensuring data quality. We acknowledge the support from Dr. Neel Desai and residents of GCS Medical College during data collection. We acknowledge scientists and staff, Dr. Rakshit, Dr. Swati, Dr. Bela, Mr. Mehul, Mr. Sanjay, Mr. Vishal, and Mr. Umesh, who assisted in translating and back-translating the questionnaires to and from the local languages.

Funding

This project was funded by the institute’s intramural funds (ICMR-National National Institute of Occupational Health, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS conceived the study and led the overall design and planning, with input from GS, AV, and VD. SS and BM conducted the interviews, while VD and TP facilitated institutional support and access to participants. Data collection was supervised by SS, AV, and VD, and laboratory procedures were overseen by GS. SS conducted the data analysis and interpreted the results with input from GS, SM, AV, and VD. SS and GS co-wrote the initial manuscript draft. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, G., Viramgami, A., Makwana, B. et al. Effort-reward imbalance, subjective sleep quality, and inflammation in female nurses at a tertiary hospital: a pilot study. Sci Rep 15, 31650 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17717-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17717-4