Abstract

The risk of acquiring a sexually transmitted infection, such as herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), is shaped by sexual risk behavior—an aggregate measure influenced not only by an individual’s sexual behavior but also by the broader sexual network. This study quantified the temporal and age-specific variations in sexual risk behavior for HSV-2 infection in the United States population between 1950 and 2020. A population-level mathematical model was used to describe HSV-2 transmission and was calibrated with ten rounds of nationally representative, population-based data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The model produced robust fits to the age-specific, sex-specific, and temporal HSV-2 seroprevalence data across the NHANES rounds. Sexual risk behavior gradually increased starting in the early 1960s, peaked in the early 1980s, and then steadily declined through 2020. The decline was particularly pronounced in the 1990s, when sexual risk behavior dropped sharply compared to the elevated levels of the early 1980s. Sexual risk behavior was highest among individuals aged 15–24 years and steadily declined with increasing age. The analysis identified a distinct wave of sexual risk behavior that began in the early 1960s, peaked in the early 1980s, and subsequently declined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) comprise a diverse group of pathogens that can cause disease and death, with implications for individuals, communities, and healthcare systems1,2,3,4,5. These pathogens propagate within sexual networks, defined as groups of individuals connected through sexual relationships, and are transmitted during sexual acts when individuals form partnerships1,6,7,8,9,10.

The risk of acquiring an STI within a sexual network is commonly described by the concept of “sexual risk behavior”11. However, this concept is poorly defined, as no single behavior exclusively determines the risk of STI acquisition11. STI risk is influenced not only by an individual’s sexual behavior but also by the “ecology” surrounding the individual within the sexual network, including the behaviors of direct partners, their partners, and their partners’ partners1,7,10,12. An individual with multiple recent sexual partners may remain uninfected, while another with only one partner may acquire an STI, depending on their position within the network and the dynamics of infection transmission within the network.

Since the discovery of the HIV pandemic, extensive research has focused on understanding sexual risk behavior13,14. This research identified specific behaviors, such as having multiple sexual partners or engaging in sex with female sex workers, as factors that increase the risk of acquiring STIs1,14,15,16,17,18,19. Additionally, properties of sexual networks, including concurrency, clustering, and degree correlation, have been shown to influence STI transmission risk1,12,20,21,22. Yet, it remains that no single sexual behavior or sexual network metric can exclusively capture the risk of acquiring an STI.

Complicating this matter further is the difficulty of accurately measuring sexual behavior13,22. Although substantial data have been collected over the past decades, most of these data rely on self-reports13,23. The sensitive nature of sexual behavior, along with non-random social desirability and recall biases, can compromise their accuracy20,24,25,26. Biomarker studies have also revealed discrepancies between self-reported sexual behavior and biological evidence, highlighting the limitations of self-reported data27,28.

In this study, a novel perspective is proposed to functionally define and quantify sexual risk behavior within a population by leveraging its direct consequence—STI acquisition. This is achieved through mathematical modeling, which provides a mechanistic framework for understanding how STIs propagate within sexual contact networks, directly linking sexual behavior to STI acquisition and transmission29,30,31.

The approach is applied to herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection32, which serves as a suitable proxy biomarker for sexual risk behavior due to its incurable, lifelong nature, rendering it largely unaffected by treatment patterns23,33,34,35. HSV-2 antibody prevalence (seroprevalence) also provides a reliable measure of lifetime exposure to the infection32,33. The analysis focuses on the United States (U.S.), where robust, standardized, population-based, sex- and age-stratified HSV-2 data have been collected over several decades through the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES)36,37,38,39,40, facilitating the application of this approach.

Fundamentally, this approach resembles reverse engineering, as it deconstructs observed HSV-2 infection patterns in the population to infer the underlying aggregate population-level sexual risk behavior that produced these patterns. This approach is demonstrated by addressing a specific question: How has population-level sexual risk behavior evolved in the U.S. over the past few decades?

Materials and methods

Mathematical model

This study employed a deterministic, compartmental, population-level dynamical model previously developed to characterize HSV-2 transmission dynamics in the U.S. population41. A detailed description of the model structure, governing equations, and parameterization is provided in Section S1 of the Supplementary Material, while a brief overview is presented here.

The model is based on current knowledge of the natural history and epidemiology of HSV-2 infection41,42,43,44,45. It consists of a system of coupled nonlinear differential equations that stratify the population by HSV-2 status, stage of infection, sex, age group, and sexual risk group41. The model was implemented and analyzed using MATLAB R2019a (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA).

The population was divided into 20 age groups, each representing a five-year interval (0–4, 5–9, …, 95–99 years)41. The model incorporated two stages of viral shedding—primary infection and reactivation—along with latent periods without viral shedding between reactivation episodes41. Individuals who acquired HSV-2 for the first time progressed from the primary infection stage to a lifelong latent phase marked by episodic reactivations41,42,43,44,45.

The force of infection was determined by the sexual contact rate and the probability of HSV-2 transmission per partnership between a susceptible and an infected individual of the opposite sex41. This probability depended on the transmission probability per coital act during each stage of infection, the frequency of sexual acts within the partnership, and the duration of the partnership41.

Sexual risk behavior

Sexual risk behavior for men at a given time t was expressed using the function \(\rho \left( {t;a,i} \right)\) that estimates the sexual contact rate, representing the risk of acquiring HSV-2 infection for a specific age group a and risk group i.

This function serves as a summary measure of sexual risk behavior in the population, capturing both the distribution and intensity of exposure risk to infection. It reflects not only partner change rates but also sexual network factors that influence exposure risk, such as variability in partner change patterns, concurrency, clustering, and degree correlation1,10,12,46,47,48. \(\rho \left( {t;a,i} \right)\) was parametrized as the product of three functions: one time-dependent, one age-dependent, and one risk group-dependent:

Here, \(\eta \left( t \right)\) describes the risk of exposure to HSV-2 infection over time, and \(\psi \left( a \right)\) captures how this risk varies by age. \(\eta \left( t \right)\) was modeled non-parametrically as a piecewise function with five-year intervals to quantify population-level sexual risk behavior across successive five-year calendar periods. Similarly, \(\psi \left( a \right)\) was modeled as a piecewise function with five-year intervals to capture variations in sexual risk behavior across different five-year age groups.

Meanwhile, \(f\left( i \right)\) is a power-law function that characterizes how the risk of exposure varies across different risk groups within the population. Its form was informed by sexual behavior data50, the structure of sexual networks as scale-free networks50, and findings from network and modeling analyses46,51,52,53,54. It is defined as:

where \(\theta\) is the exponent parameter that determines the degree of variation in exposure risk across risk groups11,41,55,56.

The population was stratified into five sexual risk groups to capture the variation in sexual risk behavior, ranging from the general population to high-risk groups41. The proportion of individuals in each risk group was informed by NHANES data on the reported number of sexual partners in the past 12 months40.

Sexual partner mixing across different age and sexual risk groups was modeled using mixing matrices that accounted for both assortative mixing (preferential partner selection within the same age or risk group) and proportionate mixing (random partner selection without preference for age or risk group)41,57.

Sexual risk behavior among women was derived by balancing sexual contact rates, ensuring that the number of contacts formed by women in any specific subpopulation (defined by age and risk group) with men in another subpopulation equals the number of contacts formed by men in the latter subpopulation with women in the former subpopulation41,57. Further details on this balancing procedure are provided in Section S1 of the Supplementary Material.

Data sources and model parameters

Model parameter values were sourced from primary studies on the natural history and epidemiology of HSV-2 infection, with detailed descriptions of the parameters, their justifications, and sources provided elsewhere41. Demographic data, including population size by age and sex, along with historical trends and future projections, were obtained from the Population Division database of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs58.

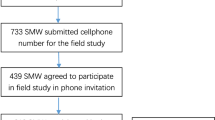

HSV-2 seroprevalence data by age and sex were extracted from ten publicly available biennial rounds of the nationally representative, population-based NHANES surveys, conducted between 1988 and 201636,37,38,39,40. The 1976–1980 round was excluded due to survey procedural differences and previously identified limitation related to its measures41.

Each survey round followed standardized methodologies for both analytical and laboratory procedures36,37,38,39,40. Data on demographics, sexual behavior, and HSV-2 laboratory testing from each round were extracted, merged, and analyzed following NHANES standardized guidelines59. Sampling weights were applied to all NHANES-derived estimates to ensure representativeness of the U.S. population.

Model calibration

The demographic part of the model was first fitted to reproduce the sex-specific and age-specific demographic projections for the U.S., as provided by the Population Division of the United Nations58. Following this, the epidemiological part of the model was fitted to NHANES time-series, sex-specific, and age-specific HSV-2 seroprevalence data from 1988 to 201640.

Model fitting was conducted using a non-linear least-squares method60,61. This calibration process enabled the estimation of the \(\eta \left( t \right)\) and \(\psi \left( a \right)\) functions, which quantify the population-level sexual risk behavior across successive five-year calendar periods and adult age groups, respectively.

Fitting parameters were varied to minimize an objective function defined as the sum of squared differences between model-predicted and observed HSV-2 seroprevalence among women and men for each age group and survey round, following established approaches41,56,62. Model fit was assessed using formal goodness-of-fit metrics, including the root mean square error. This calibration process produced a uniquely identifiable parameter set. The optimization was conducted using the Nelder-Mead simplex algorithm60, a widely used, derivative-free numerical method for minimizing multidimensional functions.

Uncertainty analysis

An uncertainty analysis was conducted to quantify uncertainty in the estimated population-level trends in sexual risk behavior, following an established validation strategy widely applied in similar modeling studies and cost-effectiveness analyses, and consistent with recommended practices for such applications41,55,56,63,64,65,66,67,68. In the absence of established empirical uncertainty bounds for HSV-2 biological parameters and other inputs, this approach provided a practical and accepted means to capture uncertainty in this study.

This approach involved 500 model runs using Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) from a multidimensional distribution of model parameters, applying ± 30% uncertainty to the point estimates of these parameters41. LHS is a stratified sampling technique that efficiently captures variability across the full parameter space while requiring fewer simulations compared to simple random sampling69,70.

Each parameter range was divided into 500 equally probable intervals, with one value randomly selected from each interval without replacement. These values were then randomly combined across parameters to generate 500 unique parameter sets. For each set, the model was refitted to the data. The resulting distributions of estimates were used to derive the mean estimates and corresponding 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs), reflecting the uncertainty in projections driven by joint variation in biological and behavioral parameters.

Sensitivity analyses

To further assess the robustness of the estimated population-level trends in sexual risk behavior, sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine the impact of extreme variations in key model parameters. Specifically, each parameter was varied independently by ± 80% from its baseline value. These parameters included the per-coital-act probability of HSV-2 transmission, the frequency of HSV-2 shedding, the degree of assortative mixing by sexual risk group, and the degree of assortative mixing by age group. These analyses provided an additional assessment of the model’s capacity to reliably reproduce estimated sexual risk behavior trends across a broad range of parameter assumptions.

Results

The model demonstrated robust fits to the U.S. population size (Fig. S1 of Supplementary Material), age-specific HSV-2 seroprevalence data across NHANES rounds for women (Fig. 1) and men (Fig. 2) aged 15–49 years, temporal trends in HSV-2 seroprevalence among all individuals aged 15–49 years (Fig. 3a), and sex-specific temporal trends in HSV-2 seroprevalence among individuals aged 15–49 years (Fig. 3b). The root mean square error was 1.3% points, indicating a low average deviation between model-predicted and observed HSV-2 seroprevalence across age groups, sexes, and survey rounds.

Model fitting of age-specific HSV-2 seroprevalence among women in the United States. Comparison of model-estimated age-specific HSV-2 seroprevalence with NHANES data for women aged 15–49 years across survey rounds from 1988 to 2016. HSV-2 denotes herpes simplex virus type 2, and NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys.

Model fitting of age-specific HSV-2 seroprevalence among men in the United States. Comparison of model-estimated age-specific HSV-2 seroprevalence with NHANES data for men aged 15–49 years across survey rounds from 1988 to 2016. HSV-2 denotes herpes simplex virus type 2, and NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys.

Model fitting of HSV-2 seroprevalence over time in the United States. (a) Comparison of model-fitted temporal trends in HSV-2 seroprevalence among all individuals aged 15–49 years with NHANES data. (b) Comparison of model-fitted sex- specific temporal trends in HSV-2 seroprevalence among individuals aged 15–49 years with NHANES data. HSV-2 denotes herpes simplex virus type 2, and NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys.

Figure 4 shows the model-estimated temporal trend in population-level sexual risk behavior in the U.S. from 1950 to 2020. The results indicate a gradual increase in sexual risk behavior beginning in the early 1960 s, peaking in the early 1980 s, followed by a steady decline through 2020. Notably, the 1990 s exhibited a sharp decline in sexual risk behavior compared to the levels observed in the 1980s.

Figure 5 shows the model-estimated age-specific variation in population-level sexual risk behavior in the U.S. The results indicate that sexual risk behavior is highest among individuals aged 15–24 years, followed by a gradual decline with increasing age.

Figure S3 in the Supplementary Material presents the results of the sensitivity analyses assessing the impact of extreme variations in key model parameters. Across all four analyses, the model produced consistent estimates for the temporal evolution of population-level sexual risk behavior, reinforcing the robustness of the study’s findings and conclusions.

Discussion

This study presented an approach to defining and quantifying sexual risk behavior at the population level. The approach leverages the fact that HSV-2 infection, which results from sexual behavior and an individual’s position within a sexual network, leaves a permanent biological marker—detectable antibodies in the blood. This serological marker serves as an objective, measurable indicator of sexual risk, enabling the evaluation of aggregate sexual risk behavior within the population over time through the use of mathematical modeling.

By applying this approach to the U.S. population, the analysis revealed a distinct wave of sexual risk behavior that began in the early 1960 s, peaked in the early 1980 s, and declined thereafter, with a particularly sharp decrease observed during the 1990s. These trends align with socio-cultural shifts in the U.S. over the past several decades, including the “sexual revolution” of the 1960 s and changes in sexual behavior following the introduction of oral contraceptives71,72. Oral contraceptives facilitated greater sexual freedom by decoupling sex from the risk of pregnancy. The decline in sexual risk behavior observed from the late 1980 s onward also aligns with the widespread concern and behavioral changes triggered by the discovery of the HIV/AIDS pandemic73.

These findings are consistent with evidence from self-reported sexual behavior data in the U.S., which indicate that, starting in the 1960 s, there was a decrease in the age of sexual debut, an increase in premarital sex, and a rise in the number of sexual partners74,75. For example, the proportion of women reporting premarital sex before age 15 increased from 1% among those born in the early 1900 s to 12% among those born between 1968 and 1973, while premarital sex before age 18 rose from less than 10% to over 50%75,76. Women born in the 1950 s were three to four times more likely than earlier cohorts to report five or more sexual partners. Among men, the proportion rose from 34 to 50%, then remained stable in later cohorts74,75. These behavioral trends are consistent with the model-inferred patterns (Fig. 4), which indicate a substantial rise in sexual risk behavior beginning in the 1960 s and continuing through the 1980s.

Similarly, studies have documented declines in various sexual behaviors following the recognition of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, including reductions in the number of sexual partners, an increase in monogamous partnerships, decreased sex with female sex workers, and greater use of condoms76,77. Moreover, the observed trend aligns with evidence from other regions indicating declines in HSV-2 seroprevalence following the recognition of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, including in Africa78, the Americas79, Asia80, and Europe81.

Sexual risk behavior was found to vary with age, peaking in young adulthood, specifically among individuals aged 15–24 years. This pattern aligns with NHANES data, which shows a similar distribution in the reported number of sexual partners in the U.S. (Fig. S2 in Supplementary Material). Moreover, this trend is consistent with patterns of sexual behavior observed in other regions82.

The findings should be interpreted in the context of two caveats. First, the observed changes in sexual risk behavior may lag behind actual changes in sexual behavior by few years. This delay occurs because the measure reflects the risk of exposure to infection, which only becomes evident after individual-level behavioral changes aggregate across the population, leading to appreciable alterations in the structure of sexual networks that influence infection transmission dynamics.

Second, the study specifically quantified sexual risk behavior associated with the acquisition of HSV-2 infection. Since different sexual behaviors and network statistics can affect the transmission dynamics of various STIs in distinct ways1,12,18,83, the patterns of sexual risk behavior identified in this study may not be directly applicable to other STIs. However, because sexual behavior is ultimately the driver of STI transmission, the findings are likely to remain qualitatively valid for other STIs.

This study has limitations. HSV-2 shedding was assumed to occur at a constant frequency regardless of the duration of infection, but evidence suggests that shedding declines over time84. HSV-2 infectiousness was assumed to be invariable regardless of symptoms, although this likely has a limited impact, as most viral shedding is asymptomatic42,85.

To maintain a streamlined model structure, the model did not explicitly differentiate between modes of sexual transmission, and transmission among men who have sex with men (MSM) was not modeled separately. While HSV-2 transmission among MSM is intense due to higher contact rates86,87, the majority of transmissions at the population level occur through heterosexual contact, given the substantially larger size of the heterosexual population88,89. Broader behavioral shifts—such as those triggered by the AIDS pandemic—also affected both MSM and heterosexual populations, shaping HSV-2 transmission dynamics across groups. Moreover, HSV-2 acquisition among MSM is indirectly captured, as the model is calibrated separately to sex-stratified population-level data. With these considerations, the absence of explicit MSM modeling is not likely to have an appreciable influence on the findings or conclusions.

The model did not account for concurrent HIV transmission within the population, which could influence HSV-2 dynamics due to the epidemiological interaction between these two infections12,44,90,91 and the differential impact of AIDS-related mortality11,44. However, HIV prevalence in the U.S. has never been high enough to appreciably affect the derived estimates.

The study has strengths. It utilized standardized, high-quality, population-based data from NHANES spanning three decades, providing reliable and representative estimates for the U.S. population36,37,38,39,40. A sophisticated mathematical model was employed to capture the complex dynamics of HSV-2 transmission41, grounded in quality data on the natural history and transmission parameters of the infection41,42,43,44,45. The model demonstrated robust fits to empirical data, with predicted trends closely aligning with observed patterns. Furthermore, the uncertainty and sensitivity analyses reinforced the validity of the point estimates and demonstrated the robustness of the model projections across a wide range of parameter assumptions. Lastly, the consistency between model outputs and real-world data provides additional confidence in the study’s findings.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated an approach to functionally define and quantify sexual risk behavior at the population level by leveraging its direct consequence—STI acquisition. The analysis identified age-specific variations in sexual risk behavior in the U.S. population and revealed a distinct wave of sexual risk behavior that began in the early 1960 s, peaked in the early 1980 s, and declined thereafter, with a particularly sharp decrease during the 1990s. This approach offers a framework that can be applied to other populations and extended to different STIs, providing deeper insights into the dynamics of sexual risk behavior and its variation across age groups and over time.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are provided in the main text and supplementary material. The MATLAB source code for the model is publicly available at: https://github.com/BechirNaffeti/Sexual_behavior1950_2020.

References

Omori, R., Chemaitelly, H. & Abu-Raddad, L. J. Understanding dynamics and overlapping epidemiologies of HIV, HSV-2, chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis in sexual networks of men who have sex with men. Front. Public. Health. 12, 1335693. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1335693 (2024).

Unemo, M. et al. Sexually transmitted infections: challenges ahead. Lancet Infect. Dis. 17, e235–e279. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30310-9 (2017).

Gottlieb, S. L. et al. WHO global research priorities for sexually transmitted infections. Lancet Glob Health. 12, e1544–e1551. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(24)00266-3 (2024).

Holmes, K. K. Human ecology and behavior and sexually transmitted bacterial infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 91, 2448–2455. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.91.7.2448 (1994).

Low, N. et al. Global control of sexually transmitted infections. Lancet 368, 2001–2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69482-8 (2006).

Day, S., Ward, H., Ison, C., Bell, G. & Weber, J. Sexual networks: the integration of social and genetic data. Soc. Sci. Med. 47, 1981–1992. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00306-2 (1998).

Ghani, A. C., Swinton, J. & Garnett, G. P. The role of sexual partnership networks in the epidemiology of gonorrhea. Sex. Transm Dis. 24, 45–56 (1997).

Potterat, J. J., Rothenberg, R. B. & Muth, S. Q. Network structural dynamics and infectious disease propagation. Int. J. STD AIDS. 10, 182–185. https://doi.org/10.1258/0956462991913853 (1999).

Nagelkerke, N., Seedat, S. & Abu-Raddad, L. J. Sexual behavior surveys should ask more: covering the diversity of sexual behaviors that May contribute to the transmission of pathogens. Sex. Transm Dis. 48, e119–e121. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001347 (2021).

Morris, M. Sexual networks and HIV. Aids 11, S209-S216 (1997).

Awad, S. F. & Abu-Raddad, L. J. Could there have been substantial declines in sexual risk behavior across sub-Saharan Africa in the mid-1990s? Epidemics 8, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epidem.2014.06.001 (2014).

Omori, R. & Abu-Raddad, L. J. Sexual network drivers of HIV and herpes simplex virus type 2 transmission. Aids 31, 1721–1732. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001542 (2017).

Abu-Raddad, L. J. & Nagelkerke, N. Biomarkers for sexual behaviour change: a role for nonpaternity studies? Aids 28, 1243–1245 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000217

Coates, T. J., Richter, L. & Caceres, C. Behavioural strategies to reduce HIV transmission: how to make them work better. Lancet 372, 669–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60886-7 (2008).

Neslon, K. & Williams, C. M. E., Infectious disease Epidemiology: Theory and Practice, Second Edition (Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2007).

Rogers, S. M., Miller, H. G., Miller, W. C., Zenilman, J. M. & Turner, C. F. NAAT-identified and self-reported gonorrhea and chlamydial infections: different at-risk population subgroups? Sex. Transm Dis. 29, 588–596. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007435-200210000-00005 (2002).

Turner, C. F. et al. Untreated gonococcal and chlamydial infection in a probability sample of adults. JAMA 287, 726–733. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.6.726 (2002).

Ayoub, H. H. et al. Dynamics of neisseria gonorrhoeae transmission among female sex workers and clients: A mathematical modeling study. Epidemics 48, 100785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epidem.2024.100785 (2024).

Chemaitelly, H., Weiss, H. A., Calvert, C., Harfouche, M. & Abu-Raddad, L. J. HIV epidemiology among female sex workers and their clients in the middle East and North africa: systematic review, meta-analyses, and meta-regressions. BMC Med. 17, 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1349-y (2019).

Morris, M. Telling Tails explain the discrepancy in sexual partner reports. Nature 365, 437–440. https://doi.org/10.1038/365437a0 (1993).

Manhart, L. E., Aral, S. O., Holmes, K. K. & Foxman, B. Sex partner concurrency: measurement, prevalence, and correlates among urban 18-39-year-olds. Sex. Transm Dis. 29, 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007435-200203000-00003 (2002).

Omori, R., Nagelkerke, N. & Abu-Raddad, L. J. Nonpaternity and Half-Siblingships as Objective Measures of Extramarital Sex: Mathematical Modeling and Simulations. Biomed Res Int 2017, 3564861. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3564861 (2017).

Obasi, A. et al. Antibody to herpes simplex virus type 2 as a marker of sexual risk behavior in rural Tanzania. J. Infect. Dis. 179, 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1086/314555 (1999).

LEE, R. M. & RENZETTI, C. M. The problems of researching sensitive topics:an overview and introduction. Am. Behav. Sci. 33, 510–528. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764290033005002 (1990).

Wadsworth, J., Field, J., Johnson, A. M., Bradshaw, S. & Wellings, K. Methodology of the National survey of sexual attitudes and lifestyles. J. Royal Stat. Soc. Ser. A: Stat. Soc. 156, 407–421. https://doi.org/10.2307/2983066 (2018).

Caldwell, J. C., Caldwell, P. & Quiggin, P. The social context of AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Popul. Dev. Rev. 15, 185–234. https://doi.org/10.2307/1973703 (1989).

Gallo, M. F. et al. Prostate-specific antigen to ascertain reliability of self-reported coital exposure to semen. Sex. Transm Dis. 33, 476–479. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.olq.0000231960.92850.75 (2006).

Minnis, A. M. et al. Biomarker validation of reports of recent sexual activity: results of a randomized controlled study in Zimbabwe. Am. J. Epidemiol. 170, 918–924. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwp219 (2009).

Boily, M. C. & Masse, B. Mathematical models of disease transmission: a precious tool for the study of sexually transmitted diseases. Can. J. Public. Health. 88, 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03404793 (1997).

Brunham, R. C. & Plummer, F. A. A general model of sexually transmitted disease epidemiology and its implications for control. Med. Clin. North. Am. 74, 1339–1352. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30484-9 (1990).

Yorke, J. A., Hethcote, H. W. & Nold, A. Dynamics and control of the transmission of gonorrhea. Sex. Transm Dis. 5, 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007435-197804000-00003 (1978).

Harfouche, M. et al. Estimated global and regional incidence and prevalence of herpes simplex virus infections and genital ulcer disease in 2020: mathematical modelling analyses. Sex. Transm Infect. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2024-056307 (2024).

Abu-Raddad, L. J. et al. HSV-2 serology can be predictive of HIV epidemic potential and hidden sexual risk behavior in the middle East and North Africa. Epidemics 2, 173–182 (2010).

Chemaitelly, H., Weiss, H. A. & Abu-Raddad, L. J. HSV-2 as a biomarker of HIV epidemic potential in female sex workers: meta-analysis, global epidemiology and implications. Sci. Rep. 10, 19293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76380-z (2020).

Kouyoumjian, S. P. et al. Global population-level association between herpes simplex virus 2 prevalence and HIV prevalence. Aids 32, 1343–1352. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001828 (2018).

Xu, F. et al. Trends in herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 Seroprevalence in the united States. JAMA 296, 964–973. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.8.964 (2006).

McQuillan, G., Kruszon-Moran, D., Flagg, E. W. & Paulose-Ram, R. Prevalence of herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in persons aged 14–49: United states, 2015–2016. NCHS Data Brief, 1–8 (2018).

Bradley, H., Markowitz, L. E., Gibson, T. & McQuillan, G. M. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2–United states, 1999–2010. J. Infect. Dis. 209, 325–333. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jit458 (2014).

Chemaitelly, H., Nagelkerke, N., Omori, R. & Abu-Raddad, L. J. Characterizing herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 Seroprevalence declines and epidemiological association in the united States. PloS One. 14, e0214151. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214151 (2019).

NHANES. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes_questionnaires.htm. 1988–2016.

Ayoub, H. H. et al. Analytic characterization of the herpes simplex virus type 2 epidemic in the united states, 1950–2050. Open. Forum Infect. Dis. 8, ofab218. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofab218 (2021).

Mark, K. E. et al. Rapidly cleared episodes of herpes simplex virus reactivation in immunocompetent adults. J. Infect. Dis. 198, 1141–1149. https://doi.org/10.1086/591913 (2008).

Phipps, W. et al. Persistent genital herpes simplex Virus-2 shedding years following the first clinical episode. J. Infect. Dis. 203, 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiq035 (2011).

Abu-Raddad, L. J. et al. Genital herpes has played a more important role than any other sexually transmitted infection in driving HIV prevalence in Africa. PloS One. 3, e2230. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0002230 (2008).

Schiffer, J. T., Mayer, B. T., Fong, Y., Swan, D. A. & Wald, A. Herpes simplex virus-2 transmission probability estimates based on quantity of viral shedding. J. R Soc. Interface. 11, 20140160. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2014.0160 (2014).

Watts, C. H. & May, R. M. The influence of concurrent partnerships on the dynamics of HIV/AIDS. Math. Biosci. 108, 89–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-5564(92)90006-i (1992).

Abu-Raddad, L. J. & Longini, I. M. Jr. No HIV stage is dominant in driving the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa. Aids 22, 1055–1061. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f8af84 (2008).

Kretzschmar, M. & Morris, M. Measures of concurrency in networks and the spread of infectious disease. Math. Biosci. 133, 165–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-5564(95)00093-3 (1996).

May, R. M. & Anderson, R. M. The transmission dynamics of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 321, 565–607. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1988.0108 (1988).

Liljeros, F., Edling, C. R., Amaral, L. A., Stanley, H. E. & Aberg, Y. The web of human sexual contacts. Nature 411, 907–908. https://doi.org/10.1038/35082140 (2001).

Barrat, A., Barthelemy, M., Pastor-Satorras, R. & Vespignani, A. The architecture of complex weighted networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 101, 3747–3752. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0400087101 (2004).

Boccaletti, S., Latora, V., Moreno, Y., Chavez, M. & Hwang, D. U. Complex networks: structure and dynamics. Phys. Rep. 424, 175–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2005.10.009 (2006).

Watts, D. J. & Strogatz, S. H. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature 393, 440–442. https://doi.org/10.1038/30918 (1998).

Barabasi, A. L. Linked: How Everything Is Connected to Everything Else and What It Means (Plume, 2003).

Awad, S. F. et al. Investigating voluntary medical male circumcision program efficiency gains through subpopulation prioritization: insights from application to Zambia. PloS One. 10, e0145729. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145729 (2015).

Ayoub, H. H., Chemaitelly, H. & Abu-Raddad, L. J. Characterizing the transitioning epidemiology of herpes simplex virus type 1 in the USA: model-based predictions. BMC Med. 17, 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1285-x (2019).

Garnett, G. P. & Anderson, R. M. Balancing sexual partnerships in an age and activity stratified model of HIV transmission in heterosexual populations. IMA J. Math. Appl. Med. Biol. 11, 161–192. https://doi.org/10.1093/imammb/11.3.161 (1994).

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects, the 2024 Revision (2024).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/analyticguidelines.aspx.

Lagarias, J. C., Reeds, J. A., Wright, M. H. & Wright, P. E. Convergence properties of the Nelder–Mead simplex method in low dimensions. SIAM J. Optim. 9, 112–147 (1998).

Naffeti, B., Ammar, H. & Aribi, W. B. A branch and bound algorithm for multidimensional holder optimization: Estimation of the age-dependent viral hepatitis A infection force. Math. Comput. Simul. 217, 311–326 (2024).

Makhoul, M., Ayoub, H. H., Awad, S. F., Chemaitelly, H. & Abu-Raddad, L. J. Impact of a potential chlamydia vaccine in the USA: mathematical modelling analyses. BMJ Public. Health. 2, e000345. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjph-2023-000345 (2024).

Brisson, M., Van de Velde, N. & Boily, M. C. Economic evaluation of human papillomavirus vaccination in developed countries. Public. Health Genomics. 12, 343–351. https://doi.org/10.1159/000214924 (2009).

Mangen, M. J. et al. Cost-effectiveness of adult Pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in the Netherlands. Eur. Respir J. 46, 1407–1416. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00325-2015 (2015).

Verguet, S. et al. Health gains and financial risk protection afforded by public financing of selected interventions in ethiopia: an extended cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 3, e288–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70346-8 (2015).

Awad, S. F. et al. Type 2 diabetes epidemic and key risk factors in qatar: a mathematical modeling analysis. BMJ Open. Diabetes Res. Care. 10. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2021-002704 (2022).

Awad, S. F. et al. Forecasting the impact of diabetes mellitus on tuberculosis disease incidence and mortality in India. J. Glob Health. 9, 020415. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.09.020415 (2019).

Ayoub, H. H., Chemaitelly, H., Kouyoumjian, S. P. & Abu-Raddad, L. J. Characterizing the historical role of parenteral antischistosomal therapy in hepatitis C virus transmission in Egypt. Int. J. Epidemiol. 49, 798–809. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyaa052 (2020).

Huntington, D. E. & Lyrintzis, C. S. Improvements to and limitations of Latin hypercube sampling. Probab. Eng. Mech. 13, 245–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0266-8920(97)00013-1 (1998).

Blower, S. M. & Dowlatabadi, H. Sensitivity and uncertainty analysis of complex models of disease transmission: an HIV model, as an example. Int. Stat. Rev. / Revue Int. De Statistique. 62, 229–243. https://doi.org/10.2307/1403510 (1994).

Allyn, D. Make Love, Not War: the Sexual Revolution: an Unfettered History (Routledge, 2016).

Chadwick, K. D., Burkman, R. T., Tornesi, B. M. & Mahadevan, B. Fifty years of the pill: risk reduction and discovery of benefits beyond contraception, reflections, and forecast. Toxicol. Sci. 125, 2–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfr242 (2012).

Greene, W. C. A history of AIDS: Looking back to see ahead. Eur. J. Immunol. 37, S94–S102. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.200737441 (2007).

Turner, C. F., Danella, R. D. & Rogers, S. M. Sexual behavior in the united States 1930–1990: trends and methodological problems. Sex. Transm Dis. 22, 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007435-199505000-00009 (1995).

Davis, J. A. & Smith, T. W. General Social Surveys, 1972–1996. (Conducted for the National Data Program for the Social Sciences at National at National Opinion Research Center (University of Chicago, 1996).

Finer, L. B., Darroch, J. E. & Singh, S. Sexual partnership patterns as a behavioral risk factor for sexually transmitted diseases. Fam. Plan. Perspect. 31, 228–236. https://doi.org/10.2307/2991570 (1999).

Bankole, A., Darroch, J. E. & Singh, S. Determinants of trends in condom use in the united states, 1988–1995. Fam Plann. Perspect. 31, 264–271 (1999).

Harfouche, M., Abu-Hijleh, F. M., James, C., Looker, K. J. & Abu-Raddad, L. J. Epidemiology of herpes simplex virus type 2 in sub-Saharan africa: systematic review, meta-analyses, and meta-regressions. EClinicalMedicine 35, 100876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100876 (2021).

Harfouche, M., Maalmi, H. & Abu-Raddad, L. J. Epidemiology of herpes simplex virus type 2 in Latin America and the caribbean: systematic review, meta-analyses and metaregressions. Sex. Transm Infect. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2021-054972 (2021).

AlMukdad, S., Harfouche, M., Wettstein, A. & Abu-Raddad, L. J. Epidemiology of herpes simplex virus type 2 in asia: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Lancet Reg. Health - Western Pac. 12, 100176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100176 (2021).

Alareeki, A. et al. Epidemiology of herpes simplex virus type 2 in europe: systematic review, meta-analyses, and meta-regressions. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 25, 100558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100558 (2023).

Wilson, C. M., Wright, P. F., Safrit, J. T. & Rudy, B. Epidemiology of HIV infection and risk in adolescents and youth. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 54 (Suppl 1), 5–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e243a1 (2010).

Omori, R., Chemaitelly, H. & Abu-Raddad, L. J. Can the prevalence of one STI serve as a predictor for another? A mathematical modeling analysis. Infect. Dis. Model. 10, 423–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idm.2024.12.008 (2025).

Ramchandani, M. et al. Prospective cohort study showing persistent HSV-2 shedding in women with genital herpes 2 years after acquisition. Sex. Transm Infect. 94, 568–570. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2017-053244 (2018).

Tronstein, E. et al. Genital shedding of herpes simplex virus among symptomatic and asymptomatic persons with HSV-2 infection. JAMA 305, 1441–1449. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.420 (2011).

Xu, F., Sternberg, M. R. & Markowitz, L. E. Men who have sex with men in the united states: demographic and behavioral characteristics and prevalence of HIV and HSV-2 infection: results from National health and nutrition examination survey 2001–2006. Sex. Transm. Dis. 37 (2010).

Zhang, X. et al. Prevalence and correlates of kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and herpes simplex virus type 2 infections among adults: evidence from the NHANES III data. Virol. J. 19, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-021-01731-9 (2022).

Copen, C. E., Chandra, A., Febo-Vazquez, I. & Sexual Behavior Sexual attraction, and sexual orientation among adults aged 18–44 in the united states: data from the 2011–2013 National survey of family growth. Natl Health Stat. Rep. 1–14 (2016).

Purcell, D. W. et al. Estimating the population size of men who have sex with men in the united States to obtain HIV and syphilis rates. Open. AIDS J. 6, 98–107. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874613601206010098 (2012).

Looker, K. J. et al. Effect of HSV-2 infection on subsequent HIV acquisition: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 17, 1303–1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30405-X (2017).

Omori, R., Nagelkerke, N. & Abu-Raddad, L. J. HIV and herpes simplex virus type 2 epidemiological synergy: misguided observational evidence? A modelling study. Sex. Transm Infect. 94, 372–376. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2017-053336 (2018).

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Qatar Research Development and Innovation Council [ARG01-0524-230321]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Qatar Research Development and Innovation Council. The authors also acknowledge the infrastructure support provided by the Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Biomathematics Research Core at Weill Cornell Medicine–Qatar. The authors are further grateful for the administrative support of Ms. Adona Canlas. ChatGPT was exclusively utilized to verify grammar and refine the English phrasing in our text. No other functionalities or applications of ChatGPT were employed beyond this specific scope. Following the use of this tool, the authors thoroughly reviewed and edited the content as necessary and take full responsibility for the accuracy and quality of the publication.

Funding

Qatar Research Development and Innovation Council [ARG01-0524-230321].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.S.N., H.H.A., and L.J.A. designed and parameterized the mathematical model. B.S.N. coded the model, conducted the analyses, and generated the results. H.H.A. contributed to model coding, result generation, and writing the article, and supervised the implementation of the study. B.S.N. and L.J.A. prepared the first draft of the article. L.J.A. conceived the study and led the design of the model and analyses. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Naffeti, B.S., Ayoub, H.H. & Abu-Raddad, L.J. Quantifying population-level sexual risk behavior through HSV-2 transmission dynamics in the United States, 1950–2020. Sci Rep 15, 34521 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17719-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17719-2