Abstract

Light and atmospheric nitrogen (N) deposition are key environmental factors that significantly influence plant growth and forest regeneration. As a characteristic economic tree species in South China, Gleditsia sinensis Lam. has value for both commercial applications and ecological restoration; however, research on the effects of shading and nitrogen addition on its growth physiology has so far been limited. Therefore, this study examined the combined effects of different light environments (full light, S0; light shade, 70% light, S1; moderate shading, 40% light, S2; severe shading, 10% light, S3) and nitrogen addition levels (0 g/plant, N0; 1 g/plant, N1; 3 g/plant, N2; 5 g/plant, N3) on the leaf physiology and growth of different G. sinensis seedling families (Huishui1 and Huishui4). The results show that moderate shading positively affected the growth and development of G. sinensis, including producing increases in plant height, ground diameter, total biomass, and leaf area. At the same time, increased photosynthetic pigment content and antioxidant enzyme activity were found, indicating that G. sinensis optimizes its photosynthetic mechanisms and strengthens its antioxidant defenses under low-light conditions to cope with environmental stress. Specifically, under S2 conditions, nitrogen treatment increased the photochemical efficiency and electron transfer rate of both Huishui1 and Huishui4, suggesting that nitrogen addition could enhance the conversion efficiency of light energy. Nitrogen supplementation also significantly increased the photosynthetic pigment content, antioxidant enzyme (superoxide dismutase, SOD; peroxidase, POD; and catalase) activities, and carbon and nitrogen metabolizing substances (proline, Pro and soluble sugars, SS) in G. sinensis seedlings under low-light conditions, while reducing the chlorophyll ratio and malondialdehyde (MDA) content. Furthermore, based on a random forest model, it was determined that Pro content and SOD activity under shade and nitrogen addition treatment were the key factors affecting the growth of Huishui1. In Huishui4, photosynthetic pigment content, POD activity, SS content, and MDA content emerged as the key factors regulating seedling growth. The study revealed the physiological differences and distinct regulatory mechanisms employed by different G. sinensis families to adapt to low-light environments. Overall, the S2N2 treatment yielded the most significant physiological effects, improving the adaptation of G. sinensis to varying light environments by increasing photosynthetic pigment content, strengthening antioxidant defense mechanisms, maintaining carbon and nitrogen metabolic homeostasis, and improving light energy conversion efficiency and photoprotection. In addition, Huishui4 exhibited better shade tolerance than Huishui1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global nitrogen emission and deposition rates are projected to quadruple by 2050 due to factors such as the burning of fossil fuels, extensive use of nitrogen fertilizers, and rapid advancements in agriculture1,2. This substantial and ongoing increase in nitrogen content significantly exceeds the amounts typically generated via the natural ecological cycle, making nitrogen deposition a phenomenon of great importance in the context of global environmental change3. Anthropogenic emissions of active nitrogen enter the ecosystem through the atmosphere, causing significant disruption to the natural nitrogen cycle. This disruption results in changes in nitrogen availability, ultimately impacting plant growth and photosynthetic physiology4. The outcomes of this include harmful effects on vulnerable species, increased vulnerability of plants to additional pressures, and changes in the development and physiological traits of plants5. While moderate increases in nitrogen can enhance vegetation growth, soil fertility, and forest productivity, excessive nitrogen deposition can reduce the resilience of plants to stress, disrupt nutrient balance, impede growth, and potentially lead to severe ecological issues, such as ecosystem dysfunction6,7,8. Therefore, understanding these reaction mechanisms is crucial for evaluating the impacts of nitrogen deposition on plants.

Light is a crucial ecological factor influencing plant growth9. It affects leaf traits, regulates plant growth, and is a key factor determining plant survival10; however, in natural settings, plants must adapt to various light environments such as open forests, forest windows, forest edges, and forest understories, as well as other intricate ecological niches. These differentiated light conditions, along with their seasonal and weather-dependent dynamic characteristics, profoundly impact plant survival strategies, interspecific competition, and species succession patterns. Furthermore, due to natural disasters and human interventions, light heterogeneity in afforested and cultivated areas has increased, playing a vital role in modulating plant trait expression11. Excessively low or high light intensities can disrupt normal plant physiological processes12. Previous studies have indicated that excessive shade can hinder plant growth, as low light intensity leads to insufficient absorption of light energy by leaves, impeding the provision of the materials and energy necessary for normal growth13,14. This growth inhibition is not only manifested as a decrease in growth rate; it may also affect the morphogenesis and physiological functions of plants. Conversely, excessive light stress can directly impact the structure and activity of photosynthetic organs, causing chloroplast damage, reduced chlorophyll (Chl) a/b ratio and dark reaction enzyme activity, and decreased leaf carbon assimilation capacity, ultimately stunting seedling growth15. Moreover, when seedling plants are subjected to full-light stress, they show diminished levels of photosystem II (PSII) activity and a decrease in electron transfer, leading to irreversible damage to PSII and inhibition of photosynthesis16,17. In summary, changes in light intensity significantly impact plant growth and development, morphogenesis, photosynthesis, and other physiological processes18.

Nitrogen is crucial for plant ecological and physiological functions, playing a significant role in plant diversity19. It is involved in a wide range of physiological processes, such as regulating osmotic substances, clearing reactive oxygen species, and modulating photosynthesis20. Previous studies have explored the combined effects of nitrogen deposition and shade on plant growth and physiology. For instance, nitrogen addition has been found to positively impact the growth of five tropical dry forest tree species when they are subjected to heavy shade conditions21. These findings highlight the potential benefits of nitrogen addition for promoting plant growth and development. Similarly, Ji et al.22 and Luo et al.23 showed that the addition of nitrogen can improve the growth of Japanese larch and Robinia pseudoacacia L. seedlings under light shade conditions. In addition, nitrogen plays an important role in photosynthesis, light-trapping pigments, and the production of ribulose diphosphate carboxylase24; it influences the photosynthetic rate by affecting the concentration and activity of chlorophyll and photosynthesis-related enzymes25. Guo et al.26 and Shi et al.27 found that in low-light environments, nitrogen addition can enhance the physiological metabolic capacity and light energy utilization rate of plants, thus promoting photosynthesis. Fu et al.28 also observed that nitrogen addition mitigated the negative effects of shading by increasing the photosynthetic rate and leaf area of Lactuca sativa L. Var. youmaicai. Xu et al.29 further noted that fertilization was beneficial for increasing the ecological adaptability of Quercus acutissima and Phoebe bournei seedlings under low-light conditions. Nonetheless, Li et al.30 and Liu et al.4 established that nitrogen deposition does not mitigate the adverse effects of shade on Camellia japonica (Naidong) and Quercus acutissima. This difference may be closely related to individual species characteristics, the intensity and duration of light exposure, and the level of nitrogen addition. Therefore, further empirical investigations are needed to explore the complex mechanisms involved in the interaction between nitrogen addition and shading on plant physiology.

Gleditsia sinensis Lam. is a wild tree species found throughout China, which is widely cultivated and used in China due to its unique multifunctionality and economic value. For millennia, the thorns of G. sinensis have been believed to be useful in traditional medicine, and some research has confirmed their pharmacological properties31,32,33. Furthermore, the pods, wood, and outer endosperm of G. sinensis seeds have distinct physicochemical features, giving them broad application potential as industrial raw materials, construction materials, and food resources34. In recent years, the G. sinensis industry has grown significantly in southern China, and it has been established as a major new type of economic forest plant; its planting area has also grown rapidly. Nonetheless, in actual planting, G. sinensis pod and seed yields have generally been unstable and relatively low, and this has become a key factor limiting its widespread promotion and application; it also poses a serious challenge for the industry’s long-term development35,36.

There are many factors that may cause fluctuations in the growth and yield of G. sinensis, and environmental change is undoubtedly one of the most important. Subtle changes in environmental conditions such as light and nutrients can have profound effects on the growth and development of G. sinensis. Previous studies have shown that the seedlings of G. sinensis can maintain normal growth and development by adjusting their own growth and physiological characteristics under shade conditions37. It has also been found that nitrogen application could effectively improve the chlorophyll content, PSII reaction center system activity, and light energy conversion rate of G. sinensis seedlings, thereby increasing their photosynthetic intensity and providing more energy and material basis for their growth38. Nonetheless, there have been relatively few studies considering the effects of nitrogen addition on the growth physiology of G. sinensis under shade conditions.

In view of the above, for this work, the hypothesis was proposesd that nitrogen fertilizer and light intensity will have complementary effects, enhancing the adaptability of G. sinensis to low-light environments. To test this hypothesis, two representative G. sinensis families, Huishui1 and Huishui4, were selected as plant materials for this study. These two families show different adaptive potential based on their growth characteristics, yield performance, and response to environmental conditions. The aim of comparing the effects of nitrogen addition on the morphology and physiology of G. sinensis in these two families under shade conditions is to reveal the adaptation mechanisms in these families under low-light environments and establish how nitrogen fertilizer interacts with light intensity to jointly regulate their growth and development. Further screen out the light and nitrogen conditions suitable for the growth of soap pod seedlings, improve the utilization rate of nitrogen fertilizer, and provide measures for seedling propagation management.

The results of this study not only provide a theoretical basis for the fine cultivation management of economic forests but also lay a scientific foundation for further exploration of the nutrient-utilization strategies of G. sinensis. More importantly, through in-depth exploration of the adaptability and response strategies of different families of G. sinensis to environmental changes, we expect to be able to screen out more adaptable and high-yielding varieties for promotion, providing strong support for the sustainable development of the G. sinensis industry.

Results

Differences in growth characteristics and leaf area

Different light intensities and levels of nitrogen supplementation significantly affected the plant height, total biomass, and leaf area in the two families (Table 1, \(p < 0.05\)). Compared with full light (S0), the plant height, ground diameter, and total biomass of the two families showed a trend of first increasing and then decreasing with increasing level of shade, and all of them increased overall, reaching maximum values under the S2 treatment. The S2 treatment increased the plant height, ground diameter, and total biomass for Huishui1 and Huishui4 by 58.80% and 52.30%, 40.06% and 16.35%, and 1.38 and 1.35 times, respectively (\(p < 0.05\)). The leaf areas of Huishui1 and Huishui4 showed their maximum values under the S3 and S2 treatments, respectively. There were no significant differences in plant height or leaf area between the two families. Nevertheless, significant N \(\times\) F and S \(\times\) F interaction terms indicate that the responses of these traits to particular light or N treatments differed depending on the family considered. In addition, under all light conditions, the plant height, total biomass, and leaf area of both families increased with increasing nitrogen addition, reaching their maxima under the N3 treatment.

Differences of chlorophyll fluorescence parameters

The chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of the two families of G. sinensis seedlings were affected by different light intensities and levels of nitrogen addition (Fig. 1). With decreasing light intensity, the maximum potential quantum efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm value) first decreased and then increased. In Huishui1, the N2 and N3 treatments increased Fv/Fm values by 2.41% and 1.20%, respectively, compared with N0 under full-light conditions (\(p < 0.05\)). Under the S1 condition, compared with N0, both the N2 and N3 treatments significantly increased the Fv/Fm value by 3.70% (\(p < 0.05\)). In Huishui4, compared with N0, N1, N2, and N3 significantly increased the Fv/Fm value by 3.75%, 5.00%, and 6.25%, respectively, under S2 conditions (\(p < 0.05\)); however, there were no significant differences among other treatments.

With decreasing light intensity, the photochemical efficiency (\(\Phi _{\textrm{PSII}}\)) values of the two families showed a downward trend, but there were no significant differences in the \(\Phi _{\textrm{PSII}}\) values of Huishui4 under different shade treatments. In Huishui1, the \(\Phi _{\textrm{PSII}}\) value was the highest under the S2N3 treatment, which was significantly increased by 14.54% compared with S2N0 (\(p < 0.05\)). The maximum \(\Phi _{\textrm{PSII}}\) value for Huishui4 was obtained in the S1N3 combination, and this was 14.51% higher than that in the S1N0 combination. In addition, compared with N2, the N3 treatment significantly increased the \(\Phi _{\textrm{PSII}}\) value of Huishui1, by 15.56% and 13.89% (\(p < 0.05\)), under the S2 and S3 conditions, respectively; the corresponding increases for Huishui4 were 37.50% and 3.12%.

The ETR values for Huishui1 and Huishui4 were the highest under the S2N3 and S1N3 treatments, being 10.76% and 17.85% higher than S2N0 and S1N0, respectively. In Huishui1, the coefficient of NON photochemical quenching (NPQ) value increased with decreasing light intensity (excluding S2). The NPQ values for Huishui4 under the shade treatments were significantly lower than those of the control treatment (S0). The N1, N2, and N3 treatments significantly increased the NPQ value for Huishui1, by 29.72%, 94.37%, and 35.53%, respectively, compared with N0 (\(p < 0.05\)); the corresponding increments for Huishui4 were 74.19%, 59.46%, and 1.07 times (\(p < 0.05\)). In general, the Fv/Fm values of G. sinensis seedlings under shade and nitrogen addition were between 0.80 and 0.85. In addition, the interaction effects of family, shade, and nitrogen supplementation on Fv/Fm, \(\Phi _{\textrm{PSII}}\), NPQ, and ETR were significant (\(p < 0.05\)).

Effect of nitrogen addition on chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of G. sinensis under shading conditions. S0, S1, S2 and S3 represent 100% light, 70% light, 40% light and 10% light, respectively. N0, N1, N2 and N3 denote the nitrogen levels of 0 g/plant, 1 g/plant, 3 g/plant and 5 g/plant, respectively. Different capital letters indicate statistically significant differences for nitrogen addition treatments at the same shade level (p < 0.05). Separate lowercase letters indicate significant changes between shade treatments at the same level of nitrogen addition (p < 0.05). A single asterisk (*) denotes a significant difference at the 0.05 probability level, whereas two asterisks (**) signifies a significant difference at the 0.01 probability level. NS indicates that no noteworthy difference was discovered. The reported values are shown as means ± standard error.

Differences in photosynthetic pigment content

The photosynthetic pigment content of G. sinensis leaves was significantly affected by both light intensity and nitrogen addition (Fig. 2). Specifically, family, light condition, and nitrogen treatment, along with their interactions, had significant effects on Chl a, Chl b, and Chl \(a+b\) (\(p < 0.05\)). The photosynthetic pigment content of Huishui1 was significantly lower than that of Huishui4 (\(p < 0.05\)). With decreasing light intensity, the Chl a, Chl b, and Chl \(a+b\) contents of the two families increased, and they were the highest under the S3 treatment. Under low-light conditions, the Chl a/b ratios of both families were lower than those of the full-light (S0) treatment, and the Chl a/b ratios of Huishui4 under the S2 and S3 treatments were higher than those of Huishui1.

Nitrogen addition significantly increased the photosynthetic pigment content. Under all light conditions, the Chl a, Chl b, and Chl \(a+b\) contents of Huishui1 and Huishui4 showed increasing trends with increasing nitrogen addition (excluding the N3 treatment of Huishui4). Compared with S0N0, the S0N3 condition increased the Chl a, Chl b, and Chl \(a+b\) contents in Huishui1 by 38.22%, 79.70%, and 46.42% (\(p < 0.05\)), respectively, and the corresponding increases in Huishui4 were 64.57%, 1.67 times, and 86.24% (\(p < 0.05\)). Similarly, under other light conditions, the N3 treatment also significantly increased the photosynthetic pigment content of G. sinensis in the two families. Notably, nitrogen treatment reduced Chl a/b under all lighting conditions. In conclusion, nitrogen treatment significantly increased the Chl a, Chl b, and Chl \(a+b\) contents in the leaves of G. sinensis under all light conditions with the exception of Hinshui4 plants when exposed to heavy shade; it also decreased Chl a/b, and the increase in the Chl b content was more significant.

Effects of nitrogen addition on photosynthetic pigments of G. sinensis under shading conditions. S0, S1, S2 and S3 represent 100% light, 70% light, 40 % light and 10 % light, respectively. N0, N1, N2 and N3 denote the nitrogen levels of 0 g/plant, 1 g/plant, 3 g/plant and 5 g/plant, respectively. Different capital letters indicate statistically significant differences for nitrogen addition treatments at the same shade level (p < 0.05). Separate lowercase letters indicate significant changes between shade treatments at the same level of nitrogen addition (p < 0.05). A single asterisk (*) denotes a significant difference at the 0.05 probability level, whereas two asterisks (**) signifies a significant difference at the 0.01 probability level. NS indicates that no noteworthy difference was discovered. The reported values are shown as means ± standard error.

Differences in antioxidant enzyme activity and MDA content

Shading and nitrogen supplementation caused differences in the activity of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, POD, and CAT) and MDA content in G. sinensis leaves (Fig. 3). Under low light (S1, S2, and S3), the SOD, POD, and CAT activities in the two families were significantly higher than those under full light (S0). Under low-light conditions, the MDA content of Huishui1 was higher than that under the S0 treatment, while the MDA content of Huishui4 was significantly lower than under the S0 treatment (\(p < 0.05\)); the MDA content was the lowest under the S2 treatment. In particular, under the S2 and S3 treatments, the SOD activity of Huishui4 was significantly higher than that of Huishui1, and the increases in antioxidant enzyme activity were significantly higher than the increase in the MDA content.

Nitrogen treatment also significantly increased the antioxidant enzyme activity of G. sinensis seedlings under different light conditions. Specifically, under all light conditions, the SOD, POD, and CAT activities of the two families treated with N1, N2, and N3 were significantly higher than those treated with N0. The SOD activities of Huishui1 and Huishui4 were the highest under the S3N3 treatment, reaching 236.51 and 300.57 U g\(^{-1}\), respectively. The POD activities of Huishui1 and Huishui4 were the highest under the S2N2 treatment, reaching 93.79 and 95.24 U g\(^{-1}\), respectively, representing significant corresponding increases of 20.83% and 45.50% compared with the S2N0 treatment (\(p < 0.05\)). Notably, nitrogen supplementation decreased MDA levels in both families under all light conditions. The S0N3, S1N3, S2N3, and S3N3 treatments reduced the MDA content of Huishui1 and Huishui4 by 15.05% and 39.55%, 21.27% and 31.89%, 19.60% and 15.07%, and 18.57% and 30.27%, respectively. In general, nitrogen addition effectively enhanced the antioxidant system (SOD, POD, and CAT) of G. sinensis leaves under shade conditions, while it decreased the MDA content. This indicates that the antioxidant defense mechanism was significantly improved by nitrogen addition, reflecting the positive effect of nitrogen on the plant’s adaptation to low-light environments.

Effects of nitrogen addition on SOD, POD and CAT activities and MDA content of G. sinensis under shading treatment. S0, S1, S2 and S3 represent 100% light, 70% light, 40% light and 10% light, respectively. N0, N1, N2 and N3 denote the nitrogen levels of 0 g/plant, 1 g/plant, 3 g/plant and 5 g/plant, respectively. Different capital letters indicate statistically significant differences for nitrogen addition treatments at the same shade level (p < 0.05). Separate lowercase letters indicate significant changes between shade treatments at the same level of nitrogen addition (p < 0.05). A single asterisk (*) denotes a significant difference at the 0.05 probability level, whereas two asterisks (**) signifies a significant difference at the 0.01 probability level. NS indicates that no noteworthy difference was discovered. The reported values are shown as means ± standard error.

Differences in the content of soluble sugar and proline

Different light intensities and nitrogen supplementation levels significantly influenced the Pro and SS levels in the two families (Fig. 4, \(p < 0.05\)). The influence of shade, nitrogen fertilizer, and their interaction on the content of osmotic regulators in G. sinensis was very significant (\(p < 0.01\)). Specifically, the Pro content of Huishui4 was significantly lower than that of Huishui1 (\(p < 0.05\)). The Pro contents of the two families were significantly higher under low-light environments than under full light (excluding the S1 treatment of Huishui4, \(p < 0.05\)). Under the S2 and S3 treatments, the Pro content of Huishui1 was significantly increased, by 1.60 and 1.51 times, respectively. The Pro content of Huishui4 was also significantly increased, by 1.81 times, under the S2 treatment, reaching its maximum under this treatment. However, the SS contents of Huishui1 and Huishui4 under low light were significantly lower than under full light; the SS contents were the lowest under the S3 and S2 treatments, with significant decreases of 58.48% and 75.83%, respectively (\(p < 0.05\)). Under the same lighting conditions, the Pro and SS contents of the two families increased with increasing nitrogen addition, and the Pro and SS contents were the highest under the N3 treatment. It is worth noting that compared with the S3N2 treatment, the rate of increase in the SS content in the S3N3 treatment was slower. Huishui1 and Huishui4 had their highest Pro contents under the S3N3 and S2N3 treatments, respectively, with values of 256.01 and 175.09 \(\upmu\)g g\(^{-1}\), respectively. In conclusion, nitrogen treatment effectively increased the content of osmoregulatory substances (Pro and SS) in G. sinensis under all light conditions.

Effects of nitrogen addition on Pro and SS contents of G. sinensis under shading treatment. S0, S1, S2 and S3 represent 100% light, 70% light, 40% light and 10% light, respectively. N0, N1, N2 and N3 denote the nitrogen levels of 0 g/plant, 1 g/plant, 3 g/plant and 5 g/plant, respectively. Different capital letters indicate statistically significant differences for nitrogen addition treatments at the same shade level (p < 0.05). Separate lowercase letters indicate significant changes between shade treatments at the same level of nitrogen addition (p < 0.05). A single asterisk (*) denotes a significant difference at the 0.05 probability level, whereas two asterisks (**) signifies a significant difference at the 0.01 probability level. NS indicates that no noteworthy difference was discovered. The reported values are shown as means ± standard error.

Principal component analysis and correlation analysis of biochemical parameters

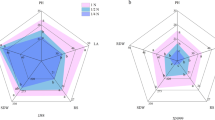

The results of principal component analysis of the physiological parameters of the two families under different light conditions and nitrogen treatments are shown in Fig. 5. The differences among the treatments under different light conditions were significant. The principal components PC1 and PC2 accounted for 50.5% and 17.6% of the total variance among treatments for Huishui1, and for 43.2% and 21.1% of the total variance among treatments for Huishui4, respectively. In Huishui1, the loadings of Chl a, Chl b, Chl \(a+b\), SOD, POD, and Pro for PC1, and of SS, Fv/Fm, and ETR for PC2 were all greater than 0.28. In Huishui4, the loadings of Chl a, Chl b, Chl \(a+b\), SOD, POD, and Pro for PC1, and of Chl a/b, \(\Phi _{\textrm{PSII}}\), and ETR for PC2 were all greater than 0.28. As shown in Fig. 6, plant height, ground diameter, total biomass and leaf area were significantly and positively correlated with Chl a, Chl b, Chl \(a+b\), SOD, POD, and Pro in Huishui1, while ground diameter, total biomass and leaf area were negatively correlated with Chl a/b, \(\Phi _{\textrm{PSII}}\) and ETR; in Huishui4, plant height, ground diameter, total biomass, and leaf area were significantly negatively correlated with MDA (\(p < 0.05\)). Overall, various factors played a role in regulating the physiological characteristics of G. sinensis leaves.

The physiological parameters of G. sinensis through principal component analysis after nitrogen addition under shading conditions. S0, S1, S2 and S3 represent 100% light, 70% light, 40% light and 10% light, respectively. N0, N1, N2 and N3 denote the nitrogen levels of 0 g/plant, 1 g/plant, 3 g/plant and 5 g/plant, respectively.

Key factors regulating the growth of G. sinensis seedlings

A random forest model was used to evaluate the key factors affecting the growth of G. sinensis seedlings under different levels of shading and nitrogen addition (Fig. 7). In Huishui1, the variable importance modeling showed that seven indicators had significant effects on plant growth, and their order of significance was: Pro > SOD > CAT > Chl \(a+b\) > Chl a > Chl b > SS. This suggests that the adaptation strategy of Huishui1 to shading and nitrogen addition primarily relies on carbon-nitrogen metabolites (such as proline, Pro) and the antioxidant enzyme system (SOD and CAT) to maintain cellular physiological homeostasis.

In contrast, for the Huishui4 family, nine significant indicators were identified, ordered as: Chl \(a+b\) > Chl b > POD > Chl a > MDA > SS > Pro > CAT > SOD. This indicates that Huishui 4’s core mechanism centers on the accumulation of photosynthetic pigments (Chl a + b and Chl b) and enhanced peroxidase (POD) activity to optimize light energy utilization under these conditions.

The significant differences in trait importance order between Huishui1 and Huishui4 are likely attributable to their genetic heterogeneity. In summary, under conditions of nitrogen addition and shading, G. sinensis seedlings exhibit family-specific physiological responses to regulate growth: Huishui1 prioritizes enhancing carbon and nitrogen metabolite content (Pro and SS) and antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD and CAT), whereas Huishui4 focuses on increasing photosynthetic pigment content (Chl a, Chl b, and Chl a + b) and relies on POD activity (Fig. 8). These distinct strategies not only validate the critical role of genetic background in shaping seedling physiological responses but also imply that future breeding efforts should employ family-specific strategies to optimize environmental adaptation.

Key factors affecting plant growth and the relative importance value of random forest. A single asterisk (*) denotes a significant difference at the 0.05 probability level, whereas two asterisks (**) signifies a significant difference at the 0.01 probability level. NS indicates that no noteworthy difference was discovered.

Discussion

Effects of shading and nitrogen addition on growth characteristics of G. sinensis

Morphological traits are influenced by the interaction of growth characteristics and environmental factors, and they are the most direct way to assess plant health39. Plants can actively respond to dynamic changes in light intensity by adjusting their biomass-allocation strategies and morphological structures, thus achieving optimal allocation and efficient utilization of environmental resources40,41. Previous research has shown that shading reduces the growth and biomass accumulation of Acacia koa (Gray) and Tetrastigma hemsleyanum Diels et Gilg42,43; however, in this study, the plant height, ground diameter, and total biomass of G. sinensis first increased and then decreased with decreasing light intensity, reaching peak values under the S2 treatment (Table 1), indicating that moderate shade has a positive effect on its growth. This is consistent with the results of Li et al.44, under moderate shading (S2), seedlings perceive competition for light resources and strategically allocate more homoides to vertical growth to maximize the utilization of light resources. This difference in results for different species may be due to the different shade tolerances and stress responses of different plants to low-light environments.

It was also found that nitrogen addition increased the plant height, ground diameter, and total biomass of G. sinensis plants under all light conditions (Table 1). This reveals the significant position of nitrogen as a key limiting factor for plant growth and development. Nitrogen is an important component of proteins, nucleic acids, chlorophyll, phospholipids, hormones (such as auxin, cytokinin), etc. Increasing nitrogen is equal to directly providing raw materials for the synthesis of these basic substances, thereby promoting cell division, elongation and tissue differentiation. In addition, nitrogen addition can enhance plant photosynthesis and the synthesis and transport of photosynthetic products, thus promoting growth and biomass accumulation45. In general, the interacting effects of nitrogen addition and shade treatment on plant height, ground diameter, and total biomass of G. sinensis seedlings were significantly different (Table 1), indicating that their growth was jointly affected by nitrogen fertilizer and shade conditions.

Effects of shading and nitrogen addition on chlorophyll fluorescence parameters

As an important index for evaluating the photosynthetic performance of plants, changes in chlorophyll fluorescence parameters can profoundly reflect the physiological state of plants in terms of light energy absorption, transfer, and distribution; they provide a key way to explore the growth status of plants and their adaptation mechanisms to the environment46. In this study, the dark-adaptive fluorescence data (Fig. 1) showed that the Fv/Fm of PSII for the two families was greater than 0.80, indicating that G. sinensis was in a healthy state under the light and nutrient conditions set in the experiments. The photosynthetic pigment organs of the leaves maintained good structural and functional integrity.

As a key environmental factor of photosynthesis, Light intensity not only directly regulates the efficiency of photochemical reactions, but also profoundly affects the structure and function of the Light-Harvesting Complex (LHC), thereby achieving efficient optimization of light energy Harvesting and light protection mechanisms47. Under saturated light intensity conditions, excess light energy flows into the photosynthetic system. To avoid light damage, the LHC undergoes conformational changes to make the arrangement of its antenna pigment protein complex more compact, thereby reducing the area of light energy capture. Meanwhile, some LHCS dissociate from the reaction centers of Photosystem II (PSII). In a low-light environment,, to enhance the efficiency of light energy absorption and transmission, the LHC drives an increase in the number of antenna pigment protein complexes and optimizes the arrangement of pigment molecules to expand the range of light energy capture.

Under low light environment (S1 and S3), the NPQ of Huishui1 increased, probably because the phosphorylation status of LHCII protein was changed, which led to structural dissociation of PSII-LHCII supercomplex in the thylakoid membrane. Thereby enhancing the non-radiative energy dissipation mediated by the violaxanthin de-epoxidation. This adaptive change is accompanied by an increase in the degree of plastiquinone (PQ) cell reduction, triggering a state transition through the STN7 kinase pathway, and transferring part of the LHCII to PSI to optimize light energy distribution. It is worth noting that the increase in NPQ of Huishui1 May also imply stress signals. It may identify low light as a potential stress (environmental) signal that requires high regulation, prioritize the activation of heat dissipation to protect the photochemical reaction center, and dynamically adjust the composition of the light energy capture device through state transition to enhance the potential for light energy utilization. This strategy has a survival advantage in dynamic shading, but it becomes a burden in stable low light due to continuous energy consumption (ATP is needed to maintain NPQ).

The high NPQ maintained by Huishui4 under full light and low NPQ under low light may be related to the internal characteristics of PSII reaction center D1 protein turnover rate and PsbS protein expression level, etc. The actual photosynthetic rate of PSII (\(\Phi _{\textrm{PSII}}\)) in Huishui4 remained relatively stable under different lighting conditions indicates that this family has a more efficient plastiquinone (PQ) library REDOX buffering capacity, which can effectively alleviate the electron transfer pressure on the PSII receptor side under different light conditions (especially weak light), ensuring the coordinated progress of photochemical reactions and carbon assimilation, and ultimately achieving the steady-state maintenance of light energy utilization efficiency.Therefore, optimizing the NPQ regulation process, achieving light protection through rapid energy dissipation under high light, and maintaining a low level of NPQ under low light may be one of the most important ways to improve photosynthetic efficiency at present48. This dynamic equilibrium mechanism enables Huishui4 to maintain a high photochemical efficiency under different light intensities, demonstrating the molecular basis of its shade tolerance. This difference in response between families fully reflects the difference in the perception and regulatory network of environmental signals between different genotypes.

This study also found that nitrogen addition significantly improved the photosynthetic performance of G. sinensis seedlings. Compared with the non-nitrogen treatments S2N0 and S1N0, the nitrogen treatments S2N3 and S1N3 significantly improved the \(\Phi _{\textrm{PSII}}\) and ETR values of both Huishui1 and Huishui4; this is similar to the results of Song and Jin49. This indicates that nitrogen addition effectively promotes the efficient capture, transfer, and transformation of light energy, and provides a more abundant energy basis for the growth of G. sinensis seedlings. On the one hand, nitrogen is an important element for the synthesis of LHC-related proteins and pigment molecules. Increasing nitrogen supply may promote the synthesis and assembly of LHC-related proteins, optimize the structure of LHCS, and enable them to capture and transfer light energy more efficiently, thereby enhancing photochemical efficiency. On the other hand, the addition of nitrogen may affect the activity or expression of enzymes related to the REDOX regulation of the PQ cell, maintaining an appropriate REDOX state in the PQ cell, ensuring the smooth operation of the electron transport chain, stabilizing the kinetics of the PSII reaction center, and thereby enhancing the photochemical electron transfer efficiency, providing more sufficient energy for the growth of G. sinensis seedlings.

In addition, nitrogen addition may affect the aggregation status of LHCII by regulating the expression or modification of LHCII aggregation-related proteins. This study revealed the positive effects of nitrogen treatment on NPQ in the two families under specific light conditions (S2). Compared with N0, the nitrogen treatments significantly increased the NPQ values, consistent with the results of Li et al.50. It may be that the protein content of PsbS increased with increasing nitrogen levels under S2 conditions, which promoted proper aggregation of LHCII and enhanced the ability of Acacia pod seedlings to dissipate excess light energy in the form of heat, leading to a significant increase in NPQ values. Furthermore, the increase of nitrogen level can enhance the antioxidant capacity of cells, reduce the damage of PSII reaction center and LHC photosynthetic components, and ensure the integrity and functional stability of photosynthetic apparatus, which is conducive to the regulation of NPQ and the effective dissipation of light energy.

In general, in low-light environments, nitrogen addition not only fine-tunes the light energy conversion efficiency of the plants and improves the economy of light energy utilization but also provides strong physiological support for their survival and reproduction under adverse conditions by enhancing their ability to protect against excess light. Furthermore,, the differential response patterns of the two families essentially reflect the differentiation in the expression regulation of LHC polygenic families, as well as the genetic basis differences in PSII repair cycles and photoinhibition tolerance. These molecular-level adaptation strategies jointly determine the niche differentiation of shade tolerance among G. sinensis families.

The chlorophyll content and leaf area of plants are the main factors affecting their light energy capture potential51. Chlorophyll is responsible for the absorption, transmission, and transformation of light energy in plants; the increase or decrease in its content is not only a direct reflection of the physiological state of the plant but also an adaptive strategy to environmental changes52. In this study, it was found that the chlorophyll contents and leaf area of G. sinensis leaves under low-light conditions were significantly higher than those under the full-light (S0) treatment (Fig. 2 and Table 1, \(p < 0.05\)); this is similar to the results of Wu et al.53. In a low-light environment, carbon assimilation and the formation of photosynthetic products are limited, and plants can improve the efficiency of light capture and light energy absorption by increasing the leaf area and chlorophyll content.

The Chl a/b ratio is an important index for evaluating the shade tolerance of a plant, and the leaves of plants with strong shade tolerance usually show higher Chl a/b ratios54,55. In this study, under the S2 and S3 treatments, the Chl a/b ratio of Huishui4 was greater than that of Huishui1, indicating that Huishui4 had stronger shade tolerance; it also suggests that Huishui4 has a better light energy utilization strategy under low-light environments.

Nitrogen is an essential element for the synthesis of chlorophyll, and it thus plays a vital role in plant photosynthesis56,57. Similar to the results of Tian et al.58 and Wang59, this study also found that nitrogen addition can increase chlorophyll content (including Chl a, Chl b, and Chl \(a+b\)), further confirming that nitrogen is a key nutrient for plant growth. It plays a crucial role in enhancing the efficiency of plant photosynthesis, promoting the synthesis and transport of photosynthetic products, and ultimately promoting plant growth and biomass accumulation.

Photosynthetic pigment content was found to be positively correlated with leaf area (Figs. 2 and 5). When sufficient nitrogen was present, plants could synthesize more proteins to promote cell division and growth60; for example, in this study, leaf expansion increased and leaf size increased, and Fv/Fm was positively correlated with leaf area (Fig. 5). This change improves the canopy structure of the plant and enhances the transport of carbohydrates and the production of dry matter. The reduction of the content of membrane lipid peroxidation products in the leaves of G. sinensis also verified these results (Fig. 8).

It is particularly worth noting that, consistent with the results of Yin and Shen61, in this study, nitrogen addition reduced Chl a/b, and the increase in the proportion of Chl b was greater than that of Chl a. This suggests that plants can maintain the physiological homeostasis of their leaves by increasing the proportion of Chl b to adapt to scattered light in low-light environments and capture more light energy62.

In conclusion, after nitrogen addition, G. sinensis can optimize light capture and absorption by adjusting photosynthetic pigments and increasing leaf area, reduce light energy loss, and improve its adaptability to low-light environments.

Evaluating the combined effects of shading and nitrogen addition on antioxidant enzyme activity and malondialdehyde content

As a product of membrane lipid peroxidation, MDA is a reliable indicator of oxidative stress63. An excessive MDA level can cause metabolic disorders in plants, interfere with the normal physiological regulation of cells, and may even damage plant cells, thereby accelerating aging and potentially leading to plant death64. The antioxidant enzyme system can effectively remove accumulated active peroxide free radicals from cells and inhibit the generation of MDA, thus delaying premature aging of plants65. In this study, it was found that the activities of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, POD, and CAT) in the two families under low light were higher than those in full-light treatment (Fig. 3). This is similar to the findings of Wu et al.66. Under low-light conditions, membrane lipid peroxidation in plant leaves is intensified, while the protective enzyme system exhibits a high degree of environmental adaptability. By upregulating its activity, this system can eliminate harmful substances such as superoxide anion free radicals, thereby minimizing cell damage.

Notably, although low-light conditions were generally found to promote an increase in antioxidant enzyme activity, the response varied significantly among different families. The MDA content of Huishui1 increased under low light compared to full light, whereas the MDA content of Huishui4 significantly decreased under low light (\(p < 0.05\)). This difference was particularly prominent under the S2 and S3 treatments. Not only was the antioxidant enzyme activity of Huishui4 significantly higher than that of Huishui1, but the rate of increase in its enzyme activity far exceeded the rate of increase in the MDA content (Fig. 3), which strongly indicates that Huishui4 has greater shade tolerance, and its antioxidant defense mechanism is more efficient in low-light environments.

The MDA content was also found to be negatively correlated with Fv/Fm (Fig. 5), highlighting an important adaptive adjustment strategy of the active oxygen scavenging system in G. sinensis under low-light conditions. This mechanism helps plants enhance their adaptability to low-light environments by optimizing their energy distribution, reducing oxidative damage, and maintaining photosynthetic efficiency under light-limiting conditions67. In addition, nitrogen plays a crucial role in the plant antioxidant defense system, contributing to cellular health by enhancing stress resistance and promoting the clearance of reactive oxygen species68. Previous studies have shown that the addition of nitrogen stimulates plant growth to a certain extent and induces a series of physiological changes, including reducing MDA accumulation and improving photosynthetic efficiency69,70,71. This is consistent with the results of the present study, where nitrogen addition was found to enhance the antioxidant defense mechanism of G. sinensis under low-light conditions. Nitrogen addition not only provides plants with essential raw materials for cell-structure formation and biomolecule synthesis but also optimizes the efficiency of resource utilization by regulating physiological metabolic pathways, thereby promoting overall plant growth. Future studies should further investigate the regulatory mechanisms of antioxidant enzyme gene expression and the interactions between nitrogen and other environmental factors, offering new insights into the molecular basis of plant adaptation to environmental changes.

Effects of shading and nitrogen addition on the content of carbon and nitrogen metabolizing substances

The metabolic adjustment of plants under the interaction of shading and nitrogen, through the response mode of soluble sugar and proline, realizes the dynamic optimization of the coupling relationship between photosynthetic carbon fixation and nitrogen assimilation. Pro and SS play significant roles in eliminating reactive oxygen species, stabilizing the structure of cell membranes, and protecting intracellular macromolecules72. Among these, Pro can be used as a plant protective agent to obtain a potential source of nitrogen and carbon, and plays an important role in plant development73. In this study, it was found that the Pro content in the leaves of soapberry seedlings increased under weak light conditions (Fig. 4), indicating that the accumulation of Pro enhanced the adaptability of soapberry seedlings to weak light environments. In a low-light environment, proline may stabilize the actual photosynthetic efficiency of PSII by stabilizing chloroplast structures (such as thylakoid membranes) and protecting the reaction centers of photosystem II (PSII), thereby alleviating the damage to photosynthetic mechanisms. In this study, the proline content was positively correlated with the maximum photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm) of PSII (Fig. 6), which also confirmed this point. On the other hand, the synthesis process of Pro consumes NADPH, while its degradation generates ATP and NADH. This makes Pro play an important role as a cytoplasmic NAD(P)+/NAD(P)H and energy buffer pool in the context of carbon limitation and energy dissipation requirements. It helps maintain the basic REDOX homeostasis required for key metabolic cycles (such as the Calvin cycle and the GS/GOGAT nitrogen assimilation pathway) under low light conditions.

SS are important energy storage substances and metabolic intermediates in plants, playing an indispensable regulatory role in the synthesis of organic compounds74. In this study, it was observed that under weak light conditions, the SS content of G. sinensis seedlings showed a downward trend. On the one hand, this is directly related to the sensitivity of photosynthesis to light intensity. Light intensity regulates the carboxylation activity of Rubisco enzyme and the \(\textrm{CO}_2\) fixation efficiency in dark reactions by influencing the electron transfer efficiency of photosystem II (PSII) and the generation rates of ATP and NADPH in the light reaction75. Under shading conditions, the reduction of light quantum flux density (PPFD) leads to insufficient supply of photoreaction products, the suppression of Rubisco activity, and the decrease in \(\textrm{CO}_2\) assimilation rate, directly restricting the synthesis of photosynthetic products (such as propyl phosphate), and thereby reducing the accumulation of soluble sugars76. For instance, in this study, the \(\Phi _{\textrm{PSII}}\) and ETR of Huishui1 G. sinensis seedlings decreased under shade conditions, which also confirmed this point. On the other hand, under shading conditions, to adapt to the low-light environment, the carbon demand for structural growth increases. The limited SS should prioritize ensuring the basic metabolic activities and energy supply necessary for the basic survival of cells, rather than accumulating in large quantities as osmotic solutes77. Furthermore, nitrogen assimilation itself is also a carbon-consuming process. Both nitrogen reduction and the glutamine synthase/glutamate synthase (GS/GOGAT) cycle that assimilates it into amino acids require the consumption of carbon skeletons and energy78. In conclusion, under low light conditions, G. sinensis seedlings prioritize the most essential respiratory energy supply and infrastructure growth (SS decreased), and play multiple protective roles by enhancing Pro biosynthesis to maintain minimum physiological function and survival resilience.

As a component of amino acids, proteins and nucleic acids, nitrogen is one of the most important elements in plant growth and development, which is widely involved in the regulation of various physiological processes79. In this study, under all light conditions, nitrogen treatment significantly increased the Pro and SS contents in the leaves of G. sinensis seedlings compared with N0, with the highest Pro content observed under the N3 treatment. This may be attributed to nitrogen addition enhancing the activity of P5C synthetase during Pro synthesis, thereby promoting Pro accumulation80. The increase in SS stems from the fact that appropriate nitrogen addition may promote the conversion of propyl phosphate to sucrose by up-regulating the activities of sucrose phosphate synthase (SPS) and sucrose synthase (SUS). Meanwhile, the upregulation of the SPS gene expression may enhance the sucrose synthesis ability, thereby increasing the accumulation of SS in leaves81.

It is noteworthy that, compared with the S3N2 treatment, the rate of increase of SS in the leaves of G. sinensis seedlings under the S3N3 treatment decreased. This may be attributed to a combination of factors. When the addition of nitrogen reaches a certain threshold, the enhancement of nitrogen assimilation may stimulate the activities of sucrose phosphate synthase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase, thereby inhibiting the sugar synthesis pathway58. Furthermore, under weak light conditions (S3 treatment), light availability may become the main factor restricting the growth of G. sinensis seedlings. Even with an adequate supply of nitrogen, the limited photosynthetic capacity may still hinder the further increase of SS content.

Overall, these findings collectively reveal the physiological strategies by which G. sinensis seedlings achieve a balance between light and nitrogen resources by regulating SS and Pro. The differences in the responses of different families to the interaction between light and nitrogen (the different trends and amplations of Pro/SS changes) may stem from the inherent differences in carbon and nitrogen utilization efficiency and the genetic basis of resource allocation strategies. For instance, the activity or expression differences of chloroplast ATPase or enzymes involved in key nitrogen assimilation/re-assimilation processes (such as glutamine synthase GS and glutamate synthase GOGAT) need to be verified through subsequent proteomics.

Combined effects of shading and nitrogen addition on G. sinensis

In this study, the interaction between shade and the addition of nitrogen on the growth and physiological characteristics of G. sinensis was investigated, revealing a significant cross-effect between the two factors. Plant height, ground diameter, biomass, leaf area, and antioxidant enzyme activity in both families exhibited increasing trends with the addition of increasing levels of nitrogen (Table 1 and Fig. 3).

In Huishui1, the combined effects of shade and nitrogen supplementation significantly influenced the growth strategy of G. sinensis seedlings, with Pro content and SOD activity identified as key physiological factors, and they played an indispensable and synergistic important role in adjusting the physiological strategy of G. sinensis seedlings to adapt to environmental changes. Proline can stabilize macromolecules and maintain osmotic balance. The accumulation of Pro may trigger a series of signal transduction processes, regulate the expression of related genes in plants, and enhance the stress resistance of plants.The increased activity of SOD can protect macromolecules from oxidative damage, and both of them together ensure the normal metabolism and physiological activities of plant cells under environmental stress. Furthermore, Pro can store nitrogen sources, while SOD protects enzymes and structures related to nitrogen metabolism (such as chloroplasts), jointly adapting to the changes in nutritional status brought about by nitrogen addition and the energy limitations caused by shading, thereby promoting the growth of G. sinensis seedlings in weak light environments.

In contrast, Huishui4 exhibited a different physiological adjustment strategy. Chlorophyll content is regarded as the most crucial factor influencing the growth of Huishui4. The increase in chlorophyll content directly optimizes the efficiency of light energy capture, enabling Huishui4 to maintain a relatively high photochemical efficiency even in low-light conditions. This is an adaptive strategy of plants to adapt to weak light environments by increasing light-capturing substances, thereby enhancing the leaf absorption per unit leaf mass and making the mesophyll cells have a higher light utilization rate for a given incident light82. Additionally, increased POD activity and soluble SS content collectively contributed to a more effective antioxidant defense system and energy storage mechanism, while a reduced MDA content directly reflected lower levels of cell membrane damage (Figs. 7 and 8). These findings provide intuitive evidence of the distinct physiological responses of different G. sinensis families to environmental challenges.

It is worth noting that the differential responses of the two families to nitrogen were not only evident in their growth and physiological traits but may also reflect deeper genetic diversity at the molecular level, such as variations in gene expression patterns and proteomic characteristics. These differences are likely the result of long-term natural selection and evolutionary adaptation, forming an essential theoretical basis for future genetic engineering or selective breeding efforts aimed at developing G. sinensis varieties optimized for specific environmental conditions; however, to fully reveal the molecular mechanisms underlying these variations, further research using systems biology approaches—such as high-throughput sequencing, transcriptomics, metabolomics and proteomics—is required. Exploring these approaches will be an important direction for future research in this field.

Conclusions

In this study, the combined effects of shading and nitrogen addition on the morphology and photosynthetic physiological characteristics of G. sinensis were analyzed. Moderate shading was found to promote the growth of G. sinensis plants by enhancing light capture and absorption. This was achieved through increased chlorophyll content and leaf area, which collectively improved the plant’s survival competitiveness.

Differences in shade tolerance were observed between the two G. sinensis seed families (Huishui1 and Huishui4). Huishui4 exhibited stronger shade tolerance than Huishui1, providing a theoretical foundation for its potential use in forest planting or wetland environments. The addition of nitrogen effectively promoted the capture, transfer, and transformation of light energy, enhanced antioxidant enzyme activity, increased the content of carbon and nitrogen metabolizing substances, and reduced the MDA levels in the leaves; these effects collectively improved the adaptability of G. sinensis seedlings to low-light environments.

A comprehensive analysis of the interaction between shade and nitrogen addition revealed that the S2N2 treatment produced the most significant morphological and physiological effects. This treatment optimized the photosynthetic system, strengthened the antioxidant enzyme defense mechanism, and regulated carbon and nitrogen metabolism, thereby establishing an efficient, stable, and coordinated physiological and metabolic network. These findings provide both a theoretical basis and practical guidance for the cultivation, ecological restoration, and germplasm resource improvement of G. sinensis in forest environments.

Materials and methods

Sample selection and preparation

The experiments were conducted from April to September 2022 at the experimental base of the College of Biological Science, Guizhou Education University (\(26^\circ 38^\prime 33.69^\prime \prime\) N, \(106^\circ 47^\prime 51.18^\prime \prime\) E). This lies in an area with an average annual rainfall of 1271 mm and an altitude of 1242 m. During the period of the experiments, this region experienced an average temperature of \(28^{\circ }\)C, a highest temperature of \(31^{\circ }\)C, and a lowest temperature of \(13^{\circ }\)C. The plant materials for these experiments were chosen from excellent single plants of the Huishui1 and Huishui4 families, which are different families from Huishui, Guizhou, and were artificially cultivated. Seedlings of G. sinensis with good growth and consistent development (6 months old) were transplanted into pots, with one plant per pot (upper diameter 30 cm, lower diameter 19 cm, height 21 cm). The soil used for potting was collected from local forest land that had not been disturbed by recent fertilization, aiming to simulate the natural site conditions of G. sinensis seedlings. Before the experiment, the soil was thoroughly mixed to ensure that the initial conditions of each treatment were consistent. The soil weight in each pot was \(7.21 \pm 0.33\) kg, which corresponds to about 80% of the pot’s volume. Prior to the experiments, the soil nutrient status was as follows: 91.11 g kg\(^{-1}\) organic matter, 3.67 g kg\(^{-1}\) total nitrogen, 0.86 g kg\(^{-1}\) total phosphorus, 43.48 mg kg\(^{-1}\) available phosphorus, 8.83 g kg\(^{-1}\) total potassium, 1.29 mg kg\(^{-1}\) available potassium, and pH 8.02.

Experimental design

The experiments were conducted using a completely randomized block design with shading, nitrogen addition, and family treatments. Fixed sunshades are adopted, and gradient shading treatment is achieved through three types of black polyethylene (PE) sunshade nets with different shading rates (covering the four sides of the canopy).Ventilation gaps were set at the bottom of the shading net 20 cm from the ground to reduce temperature and relative humidity differences between treatments. Meanwhile, the shading net should be 1.5 meters away from the top of the G. sinensis seedlings to reduce the impact of heat radiation.

The shading levels were as follows: light shade (S1, 70% light, calculated as the ratio of the actual light intensity under the shade net to the total natural light), medium shade (S2, 40% light), and heavy shade (S3, 10% light). Full light was used as the control (S0, 100% light). The photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) was measured using a quantum sensor (Model LI-190R; LI-COR, USA). The light transmittance of each shading net (70%, 40%, 10% natural light) is calculated as the ratio of the PPFD under the net to the PPFD of the adjacent open control area. Throughout the entire experimental process, the average daily transmittance value was within \(\pm 5\%\) of the design target.

Nitrogen addition levels (pure nitrogen) were 0 g/plant (N0), 1 g/plant (N1), 3 g/plant (N2), and 5 g/plant (N3). Urea (\(\textrm{N}\ge 46.0\%\)) was selected as the source of nitrogen addition. It is evenly distributed in the circular grooves on the surface of each pot of soil in solid form and mixed with the soil through covering water. It is applied in two batches, with an average application of half of the total nitrogen fertilizer each time, to reduce leaching loss. The nitrogen levels used in the experiment were in reference to the shading and nitrogen addition experiment conducted by Guo et al.83 on Cyclobalanopsis glauca seedlings. Combined with the nitrogen level gradient set in the pre-experiment conducted by the research group on the effect of nitrogen addition on the growth of G. sinensis seedlings (the growth rate of 6-month-old G. sinensis seedlings slowed down at 5 g nitrogen level), the aim is to simulate the common fertilization levels in nursery cultivation or field improvement. To evaluate the response efficiency of G. sinensis seedlings to nitrogen fertilizer input under different light conditions and the differences in physiological strategies adopted by different families, thereby screening out the most suitable light and nitrogen environment for the growth of G. sinensis seedlings and providing a reference basis for the propagation and light management of G. sinensis seedlings.

The experimental site was divided into three groups. Within each group, 32 treatment combinations of \(\times\) 4 light \(\times\) 4 nitrogen levels for all two families were randomly arranged. Five repeat POTS were set for each combination, that is, there were 160 POTS in each group, totaling 480 POTS. All the seedlings in the blocks underwent shading experiments on May 15, 2022. Nitrogen was applied to the seedlings on May 24 and June 24 respectively, and the shading continued until the end of the experiment (September 30, 2022). During the experiment, routine management was carried out to prevent pests, diseases and weeds. To avoid the possible influence of light intensity gradients at the edges of the shading shed and ensure a 100cm distance between POTS to prevent mutual shading, the positions of all treatment POTS within their respective shading areas were randomly arranged, and the specific positions of all potted plants within the shed were systematically rotated weekly to maximize the averaging of the spatial position effect of each treatment within the shed.

Sampling and determination

Measurement of chlorophyll fluorescence parameters

At the end of August 2022, a MONI-PAM fluorometer (Heinz Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany) was used for the determination of chlorophyll fluorescence parameters in the late night (dark adaptation 35–40 min) on a clear day, according to the methods described by Wang84. Three seedlings from each treatment were randomly selected, and each was measured three times. The instrument directly provided readings for Fv/Fm, NPQ, and ETR of PSII. The actual photochemical efficiency of PSII (\(\Phi _{\textrm{PSII}}\)) was subsequently calculated using the formula:

where qP represents the photochemical quenching coefficient.

Measurement of photosynthetic pigment contents

The photosynthetic pigment content of each treated G. sinensis plant was determined according to the method of Tariq85. Fresh leaves, obtained from three independent seedlings, were promptly sealed in resealable airtight bags, placed into an ice box to maintain their freshness, and subsequently transported to the laboratory for analysis. There, 2 g fresh leaves were cut into thin filaments and placed into a graduated test tubes containing 5 ml of 80% acetone solution. The tubes were sealed and kept in the dark until the leaves were completely decolorized (overnight), with occasional gentle shaking to expedite extraction. Photosynthetic pigment content was quantified using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (UV-5500PC, Shanghai Yuanxi Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at wavelengths of 662 and 645 nm. Each treatment was independently repeated three times. Chlorophyll (Chl) a, Chl b, and total chlorophyll (Chl \(a+b\)) contents were calculated according to the following formula:

where A662 and A645 represent the light absorption measurements at wavelengths of 662 and 645 nm, respectively; C (mg mL\(^{-1}\)) denotes the concentration of the pigment; V (ml) signifies the volume of the extract; and W (g) indicates the weight of fresh leaves.

Determination of antioxidant enzyme activity and malondialdehyde, proline, and soluble sugar content

At the end of August 2022, fresh leaves from three seedlings from each treatment group were collected to assess SOD, POD, and CAT activities, as well as MDA, Pro, and SS content. Weigh approximately 0.1 g of frozen G. sinensis seedling leaves and add 3 mL of pre-cooled (placed on ice) 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) containing 2% (w/v) polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) and 0.2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) for homogenization. The homogenate was centrifuged (12,000g, 4\(^\circ\)C, 8 min), and the supernatant was collected for subsequent analysis. The activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), and catalase (CAT) were determined using commercial kits (Suzhou Michy Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd) and detected using the Sunrise microplate reader (TECAN, Crailsheim, Germany). The lipid peroxidation in the leaves was estimated by measuring the malondialdehyde (MDA) content of leaf homogenates with 2-thiobarbituric acid (TBA) as described by Li et al.86.

The soluble sugar (SS) content was determined according to Li and Wang87. Fresh G. sinensis seedling leaves (0.10 g) were cut into small pieces, combined with 5 ml of distilled water, sealed with parafilm, and extracted in a boiling water bath for 30 min. The extraction was repeated once. The combined extracts were filtered and the filtrate was diluted to 25 ml with distilled water. An aliquot of 0.5 ml of this solution was mixed with 1.5 ml distilled water, 1 ml of 9% phenol solution, and 5 ml concentrated sulfuric acid. After mixing, the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min, and the absorbance was measured at 485 nm. Proline (Pro) content was determined following Li and Wang87. Fresh G. sinensis seedling leaves (0.10 g) were added to 3 ml of 5% sulfosalicylic acid and extracted in a boiling water bath for 10 min. After cooling, the extract was filtered and the filtrate was collected. A 2 ml aliquot of the filtrate was transferred to a glass-stoppered test tube, mixed with 2 ml glacial acetic acid and 2 ml of the “acidic ninhydrin” reagent, and incubated in a boiling water bath for 30 min. After cooling, 4 ml toluene was added and the mixture was vortexed for 30 s. The mixture was left to stand to allow phase separation. The toluene (upper) layer was transferred to a cuvette, and its absorbance was measured at 520 nm. All the samples were conducted in three independent biological replicates.

Analysis of growth and biomass

Three plants were selected from each treatment group to measure growth characteristics. The height of each plant was measured using a straight ruler (±0.1 cm), while their ground diameters were determined using a vernier caliper (±0.01 mm). Leaf area was measured using a YMJ-CH plant leaf area meter (Wanshen Detection Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China), and three pinnated compound leaves were selected from each treatment for the determination of leaf area. After these measurements, the above-ground and underground parts of the plants were harvested. The samples were first heat-killed at 105\(^{\circ }\)C for 30 min and then dried at 80\(^{\circ }\)C until a constant weight was reached. The dry weights of the roots, stems, and leaves were recorded using an electronic balance with 0.001 g precision.

Statistical analysis

All measurements were repeated three times, and the data were collated in Microsoft Excel (2019) and expressed as means ± standard errors. The normality of all data was checked with the Shapiro–Wilk test using R v.4.4.1 (R Development Core Team, 2024), and logarithmic transformations were performed if necessary. A random forest model was constructed using the randomForest package in R, and the key factors influencing plant growth and their relative importance were determined according to the feature importance scores. To facilitate analysis and interpretation, principal component analysis of plant height, ground diameter, total biomass, and leaf area was performed before running the random forest algorithm, and the first principal component (PC1) was extracted. The PC1 interpretation of Huishui1 was 86.50%, while the PC1 interpretation of Huishui4 was 88.17%. IBM SPSS Statistics 27 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to investigate the effects of light intensity and nitrogen supplementation on the growth and physiology of G. sinensis. Using Duncan multiple comparisons, the confidence interval was found to be within 95%. Origin 2021 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) was used to construct relevant plots and charts.

Data availability

Reasonable requests for the data presented in this study can be made to the corresponding author for access.

References

Li, M. et al. Nitrogen deposition does not reduce water deficit in Ailanthus altissima seedlings. Flora 233, 171–178 (2017).

Wang, C., Liu, J., Xiao, H., Zhou, J. & Du, D. nitrogen deposition influences the allelopathic effect of an invasive plant on the reproduction of a native plant: Solidago canadensis versus Pterocypsela laciniata. PJOE. 65, 87–96 (2017).

Qiao, Y. et al. Eco-physiological adaptation strategies of dominant tree species in response to canopy and understory simulated nitrogen deposition in a warm temperate forest. Environ. Exp. Bot. 222, 105773 (2024).

Liu, C. et al. Nitrogen deposition does not alleviate the adverse effects of shade on Camellia japonica (Naidong) seedlings. PLoS One 13, e0201896 (2018).

Atlas of Ecosystem Services: Drivers, Risks, and Societal Responses (Springer International Publishing, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96229-0.

Luo, Y. et al. Increased nitrogen deposition alleviated the competitive effects of the introduced invasive plant Robinia pseudoacacia on the native tree Quercus acutissima. Plant Soil 385, 63–75 (2014).

Saberi Riseh, R., Hassanisaadi, M., Vatankhah, M. & Kennedy, J. F. Encapsulating biocontrol bacteria with starch as a safe and edible biopolymer to alleviate plant diseases: A review. Carbohyd. Polym. 302, 120384 (2023).

Savy, D. & Cozzolino, V. Novel fertilising products from lignin and its derivatives to enhance plant development and increase the sustainability of crop production. J. Clean. Prod. 366, 132832 (2022).

Kuehne, C., Nosko, P., Horwath, T. & Bauhus, J. A comparative study of physiological and morphological seedling traits associated with shade tolerance in introduced red oak (Quercus rubra) and native hardwood tree species in southwestern Germany. Tree Physiol. 34, 184–193 (2014).

Wang, L. et al. Moderate nitrogen application improved salt tolerance by enhancing photosynthesis, antioxidants, and osmotic adjustment in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1196319 (2023).

del Pino, G. A., Brandt, A. J. & Burns, J. H. Light heterogeneity interacts with plant-induced soil heterogeneity to affect plant trait expression. Plant Ecol. 216, 439–450 (2015).

Duan, R., Huang, M., Kong, X., Wang, Z. & Fan, W. Ecophysiological responses to different forest patch type of two codominant tree seedlings. Ecol. Evol. 5, 265–274 (2015).

Shi, Y., Ke, X., Yang, X., Liu, Y. & Hou, X. Plants response to light stress. J. Genet. Genomics 49, 735–747 (2022).

Zhou, Y., Huang, L., Wei, X., Zhou, H. & Chen, X. Physiological, morphological, and anatomical changes in Rhododendron agastum in response to shading. Plant Growth Regul. 81, 23–30 (2017).

Gong, W. Z. et al. Tolerance vs. avoidance: two strategies of soybean (Glycine max) seedlings in response to shade in intercropping. Photosynthetica. 53, 259–268 (2015).

Bassi, R. & Dall’Osto, L. Dissipation of light energy absorbed in excess: The molecular mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 72, 47–76 (2021).

Zhang, J., Xie, S., Yan, S., Xu, W. & Chen, J. Light energy partitioning and photoprotection from excess light energy in shade-tolerant plant Amorphophallus xiei under steady-state and fluctuating high light. Acta Physiol. Plant. 43, 125 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Changes in light environment, morphology, growth and yield of soybean in maize-soybean intercropping systems. Field Crop Res 200, 38–46 (2017).

McDonnell, T. C. et al. Vegetation dynamics associated with changes in atmospheric nitrogen deposition and climate in hardwood forests of Shenandoah and Great Smoky Mountains National Parks, USA. Environ. Pollut. 237, 662–674 (2018).

Sikder, R. K. et al. Nitrogen enhances salt tolerance by modulating the antioxidant defense system and osmoregulation substance content in Gossypium hirsutum. Plants (Basel). 9, 450 (2020).

Tripathi, S. N. & Raghubanshi, A. S. Seedling growth of five tropical dry forest tree species in relation to light and nitrogen gradients. J. Plant Ecol. 7, 250–263 (2014).

Ji, D. H., Mao, Q., Watanabe, Y., Kitao, M. & Kitaoka, S. Effect of nitrogen loading on the growth and photosynthetic responses of Japanese larch seedlings grown under different light regimes. J. Agric. Meteorol. 71, 232–238 (2015).

Luo, Y. et al. Functional traits contributed to the superior performance of the exotic species Robinia pseudoacacia: a comparison with the native tree Sophora japonica. Tree Physiol. 36, 345–355 (2016).

Wu, F. Z., Bao, W. K., Li, F. L. & Wu, N. Effects of water stress and nitrogen supply on leaf gas exchange and fluorescence parameters of Sophora davidii seedlings. Photosynthetica 46, 40–48 (2008).

Pei, H.-F. et al. Effects of simulated nitrogen deposition on growth and photosynthetic characteristics of one-year-old Toona sinensis seedlings. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. (in Chinese and English) 27, 1546–1552 (2019).

Guo, X. et al. Effects of nitrogen addition on growth and photosynthetic characteristics of Acer truncatum seedlings. Dendrobiology 72, 151–161 (2014).

Shi, F. J. et al. Effects of light and nitrogen interaction on photosynthetic physiological characteristics in leaves of Phoebe bournei seedlings. Acta Botan. Boreali-Occiden. Sin. 40, 667–675 (2020).

Fu, Y. et al. Interaction effects of light intensity and nitrogen concentration on growth, photosynthetic characteristics and quality of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. Var. youmaicai). Scientia Horticulturae 214, 51–57 (2017).

Xu, H. D. et al. Responses of leaf functional traits and biomass of Quercus acutissima and Phoebe bournei seedlings to light and fertilization. Acta Ecol. Sin. 41, 2129–2139 (2021).

Li, M., Guo, W., Du, N., Xu, Z. & Guo, X. Nitrogen deposition does not affect the impact of shade on Quercus acutissima seedlings. PLoS One 13, e0194261 (2018).

Jung, M.-A. et al. Gleditsia sinensis Lam. aqueous extract attenuates nasal inflammation in allergic rhinitis by inhibiting MUC5AC production through suppression of the STAT3/STAT6 pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 161, 114482 (2023).

Lee, J. et al. Cytochalasin H, an active anti-angiogenic constituent of the ethanol extract of Gleditsia sinensis thorns. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 37, 6–12 (2014).

Zhang, Z. et al. Triterpenoidal saponins from Gleditsia sinensis. Phytochemistry 52, 715–722 (1999).

Zhang, J.-P. et all. Gleditsia species: An ethnomedical, phytochemical and pharmacological review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 178, 155–171 (2016).

Li, L.H. Analysis of economic utilization value, market prospect, development problems and strategies of Gleditsia sinensis. Mod. Hortic. 22–23 (2018).

Li, T. Z., Liu, H. Y., Liu, Y. X., Zhou, D. F. & Dong, G. T. Occurrence characteristics and key points of green prevention and control technology for main pests of Gleditsia sinensis. Southern Agric. 14, 58–60 (2020).

Xiao, M. et al. Effects of shading on the growth and biochemical characteristics of Gleditsia sinensis seedlings. J. Cent. S. Univ. For. Technol. 44, 73–83 (2024).

Li, J. Q. et al. Effects of different nitrogen application rates on the growth and photosynthetic characteristics of Gleditsia sinensis seedlings. For. Ecol. Sci. 39, 28–33 (2024).

Shi, G., Xia, S., Liu, C. & Zhang, Z. Cadmium accumulation and growth response to cadmium stress of eighteen plant species. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 23, 23071–23080 (2016).

Huante, P. & Rincón, E. Responses to light changes in tropical deciduous woody seedlings with contrasting growth rates. Oecologia 113, 53–66 (1997).

Luo, C., Guo, Z., Xiao, J., Dong, K. & Dong, Y. Effects of applied ratio of nitrogen on the light environment in the canopy and growth, development and yield of wheat when intercropped. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 719850 (2021).

Dai, Y. et al. Effects of shade treatments on the photosynthetic capacity, chlorophyll fluorescence, and chlorophyll content of Tetrastigma hemsleyanum Diels et Gilg. Environ. Exp. Bot. 65, 177–182 (2009).

Craven, D., Gulamhussein, S. & Berlyn, G. P. Physiological and anatomical responses of Acacia koa (Gray) seedlings to varying light and drought conditions. Environ. Exp. Bot. 69, 205–213 (2010).

Li, X. et al. Growth, physiological, and transcriptome analyses reveal mongolian oak seedling responses to shading. Forests 15, 538 (2024).

Guo, X. et al. Effects of nitrogen addition on growth and photosynthetic characteristics of Acer truncatum seedlings. https://doi.org/10.12657/denbio.072.013.

Ren, C. et al. Seasonal changes in photosynthetic energy utilization in a desert shrub (Artemisia ordosica Krasch.) during its different phenophases. (2018).

Horton, P. Optimization of light harvesting and photoprotection: Molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 367, 3455–3465 (2012).