Abstract

Corrosion of mild steel in acidic environments, particularly hydrochloric acid, presents major challenges in industrial applications, resulting in significant economic losses. This study investigates the corrosion inhibition potential of ethyl 4-[(E)-(2-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)methyleneamino]benzoate (EMAB), a Schiff base, and its pyrrole derivative in HCl solutions. Using Density Functional Theory (DFT), Monte Carlo (MC), and Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, we assess their adsorption behavior, inhibition efficiency, and mechanistic pathways. Quantum chemical calculations at the B3LYP/6-311 + + G** and CAM-B3LYP-D3/Def2TZVP levels reveal that both inhibitors adopt planar geometries favorable for adsorption on metal surfaces. Proton affinity analysis indicates their ability to bind protons in acidic media, potentially mitigating corrosion. MD simulations employing the COMPASS forcefield show stronger adsorption of EMAB onto the Fe(110) surface, characterized by a shorter adsorption distance (~ 1.1 Å) compared to the pyrrole derivative (~ 1.4 Å). Radial distribution function (g(r)) analysis further supports this, with EMAB exhibiting a higher interaction peak (g(r) = 489.56). MC simulations confirm EMAB’s stronger adsorption through a highly negative adsorption energy (-312.78 kcal/mol), suggestive of a chemisorption mechanism. Global reactivity descriptors and Fukui function analyses (first and second order) identify key nucleophilic centers in both molecules that contribute to their inhibition efficiency. Overall, EMAB demonstrates superior anticorrosion performance and eco-friendly characteristics, making it a promising candidate for sustainable corrosion protection of mild steel in industrial settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In our metal-based society, metals play a crucial role in our daily lives. However, these metals are often vulnerable to corrosion1. Corrosion is defined as the deterioration or destruction of metallic materials through chemical, electrochemical, and/or metallurgical interactions with the environment. This natural process transforms metals back into their native oxide forms or other combined states, such as the minerals from which they were originally extracted1,2. Mild steel is widely used in both commercial and residential structures—such as bridges, cars, and railroads—due to its advantageous mechanical properties and affordability1,3. Mild steel typically contains C (0.3%), Mn (0.7%), Si (0.5%), Ni, Mo, Cu, P, S (0.05%) and Fe and due to its unique physical properties, it is widely used in industrial applications4. Due to the harsh conditions metals are in, corrosion is sometimes inevitable5. It equates to a global loss according to the National Association of Corrosion Engineers (NACE) of US$ 2.5 trillion, around 3.5% of global GDP4,5.

Hydrochloric and sulfuric acid solutions are often used to clean internal surfaces of pipes in industries. Hydrochloric acid finds wide applications in pickling of metals, removal of scale and acidizing of oil wells because it is more economical and trouble-free4. In a hydrochloric acid medium, mild steel easily corrodes due to the dissolution of the cementite phase (Fe3C) usually present in steel. The application of corrosion inhibitors is the most economical and practical method to mitigate electrochemical corrosion. These corrosion inhibitors are usually mixed with acids when cleaning the internal surfaces of pipes in the industry, to trap protons that initiate the corrosion process. Over the years, inorganic compounds such as nitrites, chromates etc. (anodic inhibitors), were used to reduce corrosion. From the standpoint of safety, the development of non-toxic and effective inhibitors is very important and desirable6. The most efficient and cost-effective corrosion protection technique is the use of natural and/or synthetic organic molecules as inhibitors. Many heterocyclic compounds containing N, O, P and S have been reported to be effective inhibitors (cathodic inhibitors) of steel corrosion in acid media3,5. Generally, the tendency to form stronger coordination bonds and thus the inhibition efficiency follows the trend: P < S < N < O. A broad range of organic adsorption inhibitors presently applied in the corrosion domain are expensive. This has urged the search for cheaper alternatives, such as Schiff bases. Schiff bases act as effective corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in an acidic medium due to the presence of the azomethine group \(\:(=C=N-\)). Schiff bases inhibit corrosion by getting adsorbed on the metal surface via the oxygen and nitrogen atoms7. Recently, Schiff bases have gained much importance as corrosion inhibitors because of their good inhibition activity, low cost, ease of synthesis, high synthetic yield and eco-friendly or less toxic nature34,35,36.

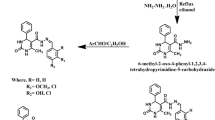

Evaluating the effectiveness of EMAB and its pyrrole derivative as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel is crucial. Mild steel is the most used construction material and is frequently found in fuel systems exposed to varying concentrations of corrosive solutions. Additionally, EMAB is an eco-friendly molecule, making it a promising candidate for sustainable corrosion protection. It is well known that species with heteroatoms and/or unsaturated rings serve as good corrosion inhibitors and therefore, the pyrrole substituent of EMAB was selected herein because it has been reported in our previous studies to be reactive and a better electron donor than EMAB8. The structure of EMAB is presented in Fig. 1.

The effectiveness of a molecule as a corrosion inhibitor hinges on its capacity to strongly adhere to the metal surface it aims to protect, which consequently reduces the molecule’s reactivity9. To evaluate the reactivity of EMAB, several electronic properties—known as global reactivity descriptors are important to consider. This includes calculations of ionization potential, electron affinity, hardness, softness, electrophilicity index, and chemical potential, based on the following relationships.

where \(\:I\) and \(\:EA\) respectively represent the vertical ionization potential and the electron affinity9,46.

where \(\:\chi\:\) is the electronegativity.

Using the finite difference approximation, the chemical potential is defined as

Considering the Koopmans’ theorem which states that \(\:{\upmu\:}\approx\:\frac{1}{2}\left({E}_{LUMO}-{E}_{HOMO}\right)\:\:\:\:\:\),

the global hardness, defined as the resistance to charge transfer, is expressed as:

while the global softness, naturally defined as the inverse of the global hardness, is expressed as:

Electrophilicity and nucleophilicity concepts are very important concepts especially in organic reactions, as they have been used in predicting reaction mechanisms10,11. The global electrophilicity index is defined as

Hirshfeld population analysis (HPA) along with the finite difference (FD) approximation method introduced by Yang and Mortier12 were used to determine the ionization potential and electron affinity. The vertical ionization potential (I) and electron affinity (EA) were calculated as follows:

where \(\:{E}_{N},\:{E}_{N-1}\) and \(\:{E}_{N+1}\) are the total (single point) energies of neutral, cationic, and anionic systems of the optimized molecular configuration respectively.

The Fukui function serves as a reactivity index within the framework of conceptual Density Functional Theory (DFT), reflecting how the electron density of a molecule shifts with changes in the number of electrons. Atom-condensed Fukui functions offer insights into the electrophilic and nucleophilic active sites of organic inhibitors49. This function aids in predicting which atoms in a molecule are more susceptible to nucleophilic or electrophilic attacks. The first order Fukui functions \(\:{f}_{k}^{+}\) and \(\:{f}_{k}^{-}\) respectively correspond to nucleophilic and electrophilic attacks and are determined using Eqs. 8 and 9.

where \(\:{q}_{k}\left(N+1\right)\) represents the charges on atoms of the molecules in their anionic state, \(\:{q}_{k}\left(N\right)\) is the charges on atoms of the molecules in their neutral state and \(\:{q}_{k}(N-1)\) is the charges on atoms in the molecules in the cationic state.

The second-order Fukui function quantifies molecular reactivity by identifying sites prone to nucleophilic and electrophilic attacks, reflecting how electron density changes with variations in electron count. This information is essential for predicting chemical behavior and guiding the design of inhibitors and catalysts49,50.

It is estimated using the following relationships:

where \(\:E\left(N\right)\) is the single point energy of the neutral species, \(\:E(N+1)\) is the energy of the species containing one electron more than the neutral species i.e. the anion and \(\:E(N-1)\) is the energy of the cation. For the calculation of second-order Fukui functions in this study, energy-based derivatives are favored over direct electron density analysis due to their grounding in Density Functional Theory (DFT). DFT fundamentally relates the ground state energy of a system to its electron density, making energy derivatives a natural and theoretically consistent starting point for defining reactivity descriptors like Fukui functions51. Furthermore, using energy helps address challenges associated with integer discontinuities in the number of electrons and avoids the arbitrariness introduced by density partitioning schemes. This approach aligns with conceptual DFT, where chemical concepts are linked to the electronic structure through energy derivatives, providing a robust framework for analyzing chemical reactivity52.

Equally, the \(\:\varDelta\:\)N value which shows an inhibitor’s efficiency to donate electrons to the metal surface (if < 3.6), is determined from

where.

\(\:{\chi\:}_{Fe}\) is often considered to be \(\:7\:\text{e}\text{V}/\text{m}\text{o}\text{l}\) while \(\:{\eta\:}_{Fe}\) is \(\:0\:eV/mol\). According to Pauling’s electrophilicity scale5,28,45. Therefore,

To identify the reactive sites of a molecule, its electrostatic potential map is usually determined. Electrostatic potential \(\:\varvec{V}\left(\varvec{r}\right)\) is an effective guide to a molecule’s reactive behavior. In atomic units, the \(\:V\left(\varvec{r}\right)\) around a molecule at any point \(\:\varvec{r}\) is the sum of nuclear and electronic contributions13.

where \(\:{Z}_{A}\:\)is the charge on the nucleus \(\:A\) located at \(\:{\text{R}}_{A}\) and \(\:\rho\:\left(\varvec{r}\right)\) is the molecule’s electronic density. On the color-coded surface MEP maps, nucleophilic centers are colored in red/orange and those prone to nucleophilic attack are colored blue. The red/orange and blue regions of a molecule’s MEP map correspond to its most negative and positive sites respectively. The regions colored in green indicate neutral sites in the molecule. Generally, V(r) increases in the order: red < orange < yellow < green < blue.

Usually, molecular electrostatic potential maps indicate charge distribution in a molecule. Indeed, the unsymmetrical distribution of charge in a molecule indicates charge transfer14.

Monte Carlo and molecular dynamics simulations

Monte Carlo (MC) and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are vital computational techniques for investigating the anticorrosion properties of organic molecules on steel surfaces. These methods are useful in modeling atomic-level interactions between corrosion inhibitors and metal surfaces, providing insights that are often difficult to obtain through experimental approaches. Research indicates that these simulations can effectively explore the adsorption mechanisms of corrosion inhibitors, revealing how molecular structure impacts their efficiency33,37,38. Three key parameters in this analysis are: Adsorption Energy values, which reflect the strength of the interaction between an inhibitor and a metal surface. Higher adsorption energies correlate with more stable protective layers, crucial for effective corrosion prevention, radial distribution functions RDFs which analyze how particle density varies with distance from a reference particle, offering insights into the spatial arrangement of inhibitors around the metal surface. This helps assess the orientation and effectiveness of the protective layer, and lastly the binding energy which indicates the energy required to detach an inhibitor from the surface. Elevated binding energies suggest a more stable attachment, which enhances the inhibitor’s corrosion prevention capabilities39,41,42.

Computational details

All quantum chemical calculations were performed using the Gaussian 09 Rev. D.01 software package15. Input files were generated with Gauss View 6.0.1616. The results were processed using Multiwfn17 and Chemcraft18. To identify the most stable conformer of EMAB, a conformational analysis was conducted through relaxed potential energy surface (PES) scans of the dihedral angles. 1(C2-C3-C17-H19) and 2(C17-N18-C20-C22) at the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6–31 + G** level of theory from 0 to 3600 in 18 steps of 200 each. The structure corresponding to minima on the PES scan was selected as the most stable conformer of EMAB. This conformer was further optimized, and frequency calculations performed at the B3LYP/6-311 + + G** and M06-2X/6-311 + + G** levels of theory and compared with the experimental parameters from Pahontu and co-workers19. Furthermore, EMAB’s derivative was optimized at the B3LYP/6-311 + + G** level of theory. Analysis of the harmonic vibrational frequencies in all cases indicated the absence of imaginary frequencies and this ascertained that the structures were true minima on the Potential Energy Surface.

All calculations related to reactivity descriptors were done at the CAM-B3LYP-(D3)/Def2TZVP and ωB97-XD/Def2TZVP levels of theory in the gas phase and in HCl solvent for comparison. These functionals were used owing to their ability to model long-range interactions effectively43,44. Hydrochloric acid, with dielectric constant (ε \(\:=\:78.3\)) was incorporated as a solvent since it is always used in cleaning the internal surfaces of pipes in industries20.

Monte Carlo and molecular dynamics simulations

Monte Carlo and Molecular Dynamics simulations were conducted to elucidate the adsorption mechanisms of inhibitors on the metal surface21. These simulations aimed to identify the most probable adsorption configurations as the temperature decreased22,23. For the Monte Carlo simulations, the Adsorption Locator module from the Material Studio MS 2017 suite by Biovia Accelrys, USA, was utilized24. Additionally, the Forcite module was employed for the geometry optimization of the adsorbate, adsorbent, and water molecules24. The optimization of the adsorbate molecules (EMAB and its pyrrole derivative) was performed using the Forcite module, applying the Smart algorithm with a specified energy cut-off of\(\:{\:1.0\:x10}^{-4}\) kcal/mol The Fe (110) crystal surface was generated by cleaving the crystal structure of iron along the (110) planes. This orientation was selected for the simulation study due to its inherent stability and is recognized as the most likely exposed face of iron25. The Fe (110) surface was optimized to achieve minimum energy using the COMPASS force field. The Fe (110) surface was chosen due to its well-defined crystallographic structure and its common use in both experimental and computational corrosion studies. This allows for a direct investigation of the interactions between the organic molecules and the iron surface, facilitating comparison with existing literature and enabling detailed computational modeling. The Fe (110) has also been reported to be the most stable form of iron, with low miller index53,54. The COMPASS (Condensed Phase Optimized Molecular Potentials for Atomistic Simulation Studies) field was employed for the simulations of all molecules and systems. COMPASS is a robust force field developed through fitting to a diverse array of experimental data for both organic and inorganic compounds. It facilitates atomistic simulations of condensed phase materials, allowing for accurate and simultaneous predictions of structural, conformational, vibrational, and thermophysical properties across a wide range of temperatures and pressures.

A \(\:10\times\:10\) supercell of the Fe (110) surface was constructed from the optimized crystal structure, and a vacuum slab of 20 Å was added above the plane to mitigate the influence of periodic boundary conditions on the system. To ensure that the selected atoms did not interact with their periodic images, six layers were included in the structure25. The Fe (110) surface was then optimized with the lower layers fixed in place. The simulation methodology employed an atom-based approach for electrostatic interactions and a group-based approach for Van der Waals interactions.

Using the Adsorption Locator module, simulated annealing was performed to identify the ten most favorable configurations for the adsorption of molecules onto the metal surface. The Smart algorithm was utilized in conjunction with the COMPASS force field for this process. The top layer of the slab was designated as the target for adsorption, with a maximum distance of 5 Å for interactions. Atoms were categorized into groups (adsorbate, adsorbent, and target atoms), and the atom volumes along with solvent surfaces were generated with a solvent radius of 1.4 Å. Water molecules were subsequently incorporated using the Amorphous Cell module in BIOVIA Materials Studio, with a specified packing density of \(\:{1\:g\:cm}^{-3}\). A total of \(\:250\) water molecules were incorporated.

A simulation of corrosion inhibitor molecules on the Fe (110) surface was conducted to identify low-energy adsorption sites for these molecules22. To investigate the adsorption behavior of EMAB and its pyrrole derivative on a mild steel surface in the presence of water, Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using the Forcite Module within BIOVIA Materials Studio 2017. The simulations employed quench dynamics, with optimization occurring every 10,000 steps. Interatomic interactions were represented using the COMPASS force field, and the MD simulations were executed in the canonical (NVT) ensemble at 298 K, utilizing the Nose thermostat to maintain the thermodynamic temperature. The time step was set to 1 fs, with initial velocities assigned randomly. The total simulation time was 200 ps, and energy coordinates and velocities were recorded every 10,000 steps throughout the simulation26. This process yielded a total of 41 optimized structures.

Proton affinity

Proton affinity is defined as the negative of the enthalpy change associated with a real or hypothetical gas-phase reaction between a neutral chemical species and a proton, resulting in the formation of the conjugate acid of the original species27,28. Since these molecules possess multiple donor sites with varying basicities, calculations were performed on their protonated forms to investigate the potential for protonation in an acidic environment and its effect on inhibiting steel corrosion. Metal corrosion primarily occurs when an electron lost by a metal atom is replaced by a proton from the surrounding medium, such as HCl or H2SO4 during pickling, leading to the generation of hydrogen gas. Additionally, acidic gases like CO2, NO2, and SO2 can exacerbate corrosion by producing acids when dissolved in water. Thus, if the inhibitor molecule captures a proton, the corrosion rate may be reduced.

The inhibitors EMAB and its pyrrole derivative contain several nucleophilic active sites that enhance their adsorption onto mild steel surfaces. In both EMAB and its pyrrole derivative, the atoms act as electrophilic sites, while the nucleophilic sites include the carbonyl oxygen atoms, the methoxy oxygen atom, the hydroxyl oxygen, and the nitrogen atoms within the azomethine group and the pyrrole ring. For EMAB, the compounds were singly protonated at N18, O15, O10, O31, and O32, while for its derivative, protonation occurred at O27, O26, N13, O10, and N42. Gas-phase geometry optimizations and frequency calculations were performed for each mono-protonated species using the B3LYP/6-311 + + g** level of theory. This method has been utilized in anticorrosion studies27.

A neutral molecule is typically protonated as follows:

Gas phase proton affinities for the species were calculated as the negative of the difference between the enthalpies of the product and the reactants as follows.

Since energies of species are calculated based on electron density and \(\:{H}^{+}\) contains no electron, its energy was calculated as follows

Proton affinities (PA) and proton dissociation enthalpies (PDE) have a close relationship with site acidity, that is, the ease of deprotonation. Substituting \(\:14\) in \(\:13\) results to

where \(\:E\left({BH}^{+}\right)\) is the energy of the protonated species, \(\:E\left(B\right)\) is the energy of the neutral molecule,\(\:\:{E(H}_{3}{O}^{+})\) is the energy of the hydroxonium ion and \(\:{E(\text{H}}_{2}\text{O})\) is the energy of the water molecule respectively46. Experimental determination of proton affinities is challenging and requires specialized experimental techniques. As a result, many proton affinities are determined using computational chemistry methods especially the Density Functional Theory (Albrakaty et al., 2018).

Results and discussion

Geometrical analysis

The optimized geometries for EMAB and its substituted pyrrole derivative are shown in Fig. 2, along with their respective numbering schemes. These structures were optimized at the B3LYP/6-311 + + g** level of theory. The XYZ coordinates for the optimized structures of EMAB and its pyrrole derivative are presented on Table S1 of the supplementary information. Equally, some selected geometrical parameters of EMAB and its derivative are presented in Table 1, alongside its existing geometrical parameters for EMAB. It is important to note that in Table 1, the parameters in EMAB that correspond to those of the derivatives are indicated in brackets for comparative purposes.

Results from Fig. 2; Table 1 indicate that the geometrical parameters, including bond angles, bond lengths, and dihedral angles, exhibit remarkable similarity between EMAB and its pyrrole derivative. This suggests that the substitution of the methoxy group in EMAB with the pyrrole group leads to minimal alterations in the molecular geometry. Additionally, our findings indicate that most dihedral angles in both molecules are close to 180 degrees, reinforcing the notion that these compounds are highly planar. This planarity is advantageous for their function as corrosion inhibitors, as planar molecules tend to align parallel to the metal surface they inhibit, thereby enhancing the efficacy of the inhibition process. Furthermore, our theoretical values for EMAB closely align with the experimental results reported by Pahontu and colleagues19. This correspondence suggests that the level of theory employed in our calculations was appropriate, as it effectively predicts the geometrical parameters in close agreement with the experimental data.

Monte Carlo simulation

Monte Carlo simulation for EMAB and its derivative indicated that both inhibitors have the potential of being adsorbed on the Fe (110) surface. The adsorption energy refers to the energy released when the inhibitor adsorbs onto the Fe(110) surface in its stable configuration (also known as the geometric optimization step), while the deformation energy is the energy released when the adsorbed inhibitor is detached from the Fe(110) surface. The negative values of the adsorption energies would indicate spontaneous adsorption on the Fe(110) surface, while a positive value would indicate non-spontaneous adsorption33. The adsorption energies for EMAB and its derivative are presented in Table 1. The total energy and adsorption energies for EMAB were generally lower than those of the pyrrole derivative. This indicates the ability of EMAB to spend more time closer to the iron surface than its derivative and therefore, EMAB exhibits stronger adsorption on the metal surface due to its more negative adsorption energy.

Rigid adsorption energy and deformation energies

Adsorption energy is the energy released when the unrelaxed inhibitor molecules (i.e. before the geometry optimization step) are adsorbed on a metal surface, while the deformation energy represents the energy released when the adsorbed inhibitor molecules are relaxed on the substrate surface1. Both adsorption and deformation energies were negative, indicating the stability of the adsorbed species on the metal surface. Generally, the inhibitors under study had parallel or flat orientations with respect to metal surface, thus covering more surface area and providing better corrosion inhibition protection. Inhibitors which have vertical orientation will not have this property29. The total energy, adsorption and deformation energies for the studied species are depicted in Table 2.

Based on the results in Table 2, the individual contributions to the total energy for EMAB are lower than those for the derivative, yet the total energy for EMAB is higher. Despite the individual energies being less negative, the highly negative total adsorption energy indicates that additional stabilization mechanisms are at play. This could involve:

Cooperative Effects: Interactions between the adsorbate and the surface, or among multiple adsorbates, may lead to enhanced stability that is not fully captured by rigid adsorption or deformation energy alone.

Solvation or Environmental Effects: The presence of solvent molecules or other environmental factors could contribute to the overall stability after adsorption, resulting in a more favorable total energy. The various views of the stable configurations from the Monte Carlo simulation are presented in Fig. 3.

The most stable configuration was obtained from among the best 10 configurations sampled during the simulation. From Fig. 3.

Top and side views of MC simulation of EMAB and its derivative adsorbed on Fe (110) surface, obtained from output files from Material Studio MS 2017 suite24.

Specifically, it has been noted that the orientation of inhibitors, such as organic molecules, plays a crucial role in their effectiveness. Inhibitors that align parallel to the metal surface can enhance their protective capabilities by maximizing the interaction area and forming a stable protective layer38. Both EMAB and the pyrrole derivative align parallel to the iron (110) surface, which is a characteristic feature of effective inhibitors. This orientation typically enhances their ability to interact with the surface, promoting stronger adsorption and potentially improving their performance in preventing corrosion or degradation.

Molecular dynamics simulation

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations conducted on the species under study provided valuable insights into their behavior and interactions at the molecular level. The simulations revealed the following key findings:

Radial Distribution Functions or pair correlation functions.

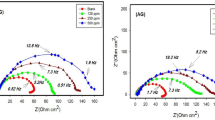

The radial distribution function is the probability distribution to find the center of a particle in each position at a radial distance \(\:r\) from the the center of a reference sphere. In other words, it is a measure of average density around atoms, which indicates the average distance where an inhibitor molecule spends most of its time during simulation. The Radial Distribution Functions for EMAB and its pyrrole derivative were determined using the total trajectory33 and are presented in Fig. 4.

The details regarding the radial distribution function data used to generate the graphs are provided in the Supplementary information Table S2.

From the results, both EMAB and the derivative have high probabilities of being adsorbed at very close distances to the surface of iron (\(\:\:110\)) i.e. at about \(\:1.1\) Å, indicating a high level of adsorption, due to the presence of the heteroatoms. The peak (g(r)) value for EMAB at this radius is 489.56, and 437.6 for the derivative. This further indicates that EMAB is a better inhibitor than its pyrrole counterpart. In addition, the next highest peak is around 1.4 Å, with a higher value for the derivative (\(\:326.2\)) than for EMAB (\(\:303.1\)). Therefore, the derivative is adsorbed at a greater distance from the iron surface compared to EMAB. Based on these findings, it can be inferred, though not with absolute certainty, that EMAB and its derivative were chemosorbed at 1.1 Å from the metal surface, and at 1.4 Å. This aligns with literature indicating that chemisorption typically occurs at distances of approximately 1.5 to 3 Å, involving the formation of strong chemical bonds (either covalent or ionic) and exhibiting higher adsorption energies, generally exceeding 40 kJ/mol40. In contrast, the effective range for physisorption is usually observed within several angstroms (typically 3–5 Å) from the surface, characterized by the interaction range of van der Waals forces. In radial distribution function (RDF) plots, distinct peaks can indicate preferred distances where the density of adsorbed particles is heightened, suggesting stable adsorption sites. Although the ranges of 3–5 Å for physisorption and less than 2 Å for chemisorption provide useful benchmarks, they should not be considered absolute limits. Careful analysis and consideration of the specific system are essential for accurately determining the nature of adsorption.

Adsorption and Binding Energies.

Adsorption energy refers to the energy released when the relaxed inhibitor molecules are adsorbed onto the metal surface. It can also be defined as the sum of the rigid adsorption energy and the deformation energy associated with the adsorbate components. The adsorption energy is mathematically expressed as:

Binding energy

It is defined to be the negative of the adsorption energy22,28.

The more negative the adsorption energy, the more affinity the adsorbate will have for the adsorbent. In the like manner, the larger (more positive) the binding energy, the more easily and tightly an inhibitor interacts with a metal surface, hence, the higher its inhibition efficiency. Results for adsorption and binding energies for EMAB and the derivative are presented in Table 3.

Our results have shown a larger negative value for adsorption energy for EMAB. An adsorption energy of −312.78 kcal/mol strongly supports chemisorption. This value indicates that the inhibitor (EMAB) forms a very stable and strong interaction with the metal surface, likely through the formation of covalent or ionic bonds. It is important to note that the adsorption energies determined from both Monte Carlo and Molecular Dynamics simulations for EMAB and its derivative agree closely, with minimal discrepancies. This consistency affirms that EMAB, exhibiting a higher adsorption energy, is more stable on the metal surface compared to its derivative. Therefore, based on this adsorption energy, and adsorption distance, it is reasonable to conclude that the adsorption mechanism is indeed chemisorption and thus a more positive value for binding energy. EMAB is therefore a better corrosion inhibitor for mild steel than its pyrrole derivative based on MC and MD studies. This is promising because EMAB has already been synthesized, allowing its anticorrosion properties to be utilized immediately, unlike its pyrrole derivative, which requires further synthesis.

The most stable frames (those with the lowest energies) during the MD simulation have been isolated and their side and top views are presented in Fig. 5.

Top and side views of MD simulation of EMAB and its derivative adsorbed on Fe (110) surface, generated from Material Studio MS 2017 suite by Biovia Accelrys, USA24.

The results from Fig. 5 confirm the fact that EMAB and its pyrrole derivative are good species to be used for the protection of iron and steel.

Quantum chemistry studies

Quantum chemistry studies are frequently employed to correlate the corrosion inhibitor properties of molecules with their predicted molecular orbital (MO) energy levels, allowing for significant savings in time and costs by reducing the need for laboratory experiments30. The energies of the frontier molecular orbitals (E-HOMO and E-LUMO), and consequently the energy gap between them, are crucial in this context. These parameters serve as valuable descriptors for reactivity.

DFT results

The inhibitory effectiveness of EMAB and its derivatives have been examined by assessing local parameters and quantifying global parameters, including chemical hardness (η), softness (σ), electronegativity (χ), and electrophilicity (ω).

Global reactivity descriptors

The HOMO energy reflects a molecule’s capacity to donate a lone pair of electrons; higher HOMO energy levels correspond to a greater ability to donate electrons to electrophilic species. Similarly, the LUMO energy indicates a molecule’s ability to accept a lone pair of electrons, with lower LUMO energy levels enhancing the molecule’s capacity to receive electrons from nucleophilic agents. Table 4 presents the various reactivity descriptors for EMAB and its pyrrole substituent, calculated using the CAM-B3LYP-(D3)/def2TZVP and ωB97-XD levels of theory in both the gas phase and HCl solvent (using the SCRF solvation model).

The results show that a smaller difference between HOMO and LUMO energies facilitates easier electron transfer from the donor molecular orbital to the acceptor molecular orbital. EMAB exhibits a significant energy gap, which decreases when the methoxy group is replaced by the pyrrole group. Additionally, global hardness values are generally higher for EMAB compared to its pyrrole substituent, while global softness values display the opposite trend. This suggests that the parent compound is less reactive than the substituted derivative, indicating that these molecules, particularly the pyrrole substitute, have the potential to adhere to surfaces and protect mild steel due to their chemical reactivity.

Both levels of theory employed to calculate the reactivity descriptors yield consistent results, reinforcing their validity. Furthermore, Table 3 illustrates that solvent effects have minimal impact on the global reactivity descriptors, as the values in gas phase and solvent are quite similar. Notably, the number of electrons transferred from the inhibitor to the mild steel surface is significantly below the threshold value of 3.6. The ΔN values do not accurately reflect the precise number of electrons transferred, leading to the recommendation that “electron-donating ability” is a more suitable term than “number of electrons transferred.” It is widely recognized that a ΔN value of less than 3.6 indicates good electron transfer capability22. In conclusion, the global reactivity descriptors indicate that both EMAB and its substituted derivative are promising candidates as anti-corrosion materials for mild steel.

Mulliken atomic charges

Mulliken charges are commonly used to assess atomic charges within a molecule and identify inhibitor adsorption centers. The propensity of a heteroatom to adsorb onto a metallic substrate through donor-acceptor interactions increases with a higher negative charge. Table 4 presents the Mulliken atomic charges for EMAB and its pyrrole derivative, calculated at the ωB97-XD/def2tzvpp level of theory.

From Table 5, the heteroatoms N and O are likely responsible for the ligand’s adsorption onto the metal surface due to their relatively high electronegativity values: O15 (−0.65126), N18 (−0.50445), O31 (−0.60214), and O10 (−0.4524) for EMAB, and O10 (−0.65442), N13 (−0.5002), O26 (−0.60138), and N42 (−0.48096) for the derivative. Therefore, EMAB and its pyrrole derivative are expected to serve as effective inhibitors, owing to the presence of heteroatoms with significant negative charges.

Proton affinity

Proton affinity is a critical parameter in anticorrosion studies, defined as the negative difference between the enthalpies of the products and reactants in reactions where a base acquires a proton and becomes protonated28. Research on Mulliken atomic charges indicates that heteroatoms, such as oxygen and nitrogen, demonstrate high proton affinity due to their elevated electronegativity. In this context, proton affinities were calculated for the protonated forms of EMAB and its pyrrole derivative.

Molecules with high electronegativity are expected to adhere strongly to metal surfaces, enhancing their adsorption. These high-affinity molecules tend to form dative bonds with protons from acids in their environment, thereby inhibiting corrosion through a dual mechanism: they adsorb onto the metal surface while also capturing protons from the medium. Consequently, H⁺ ions become less available to react with the metal, preventing the formation of H₂, a key step in the corrosion process. The findings related to proton affinity are summarized in Table 6.

Based on the results presented in Table 6, the proton affinity for the studied species is generally high. This property peaks in the oxygen atom of the hydroxyl group (–O–H), which exhibits the greatest electron affinity in both scenarios. High proton affinities suggest that these molecules can effectively attract protons from their environment, thereby inhibiting the corrosion process, which involves protons capturing electrons.

In particular, the proton affinity of EMAB is consistently higher than that of its derivative. Although global reactivity descriptors indicate that the pyrrole substituent may exhibit greater reactivity, its proton affinity values are lower. This discrepancy can be attributed to the differences in electronegativity between the nitrogen in the pyrrole substituent and the oxygen in the methoxy group. Oxygen, with its two lone pairs of electrons, has a greater capacity to hold protons compared to the nitrogen in pyrrole, which is also less electronegative.

The proton affinity values for O31 and O15 in EMAB are notably high, likely due to the low steric hindrance at these sites combined with the high electronegativity of oxygen. Conversely, N42 shows the lowest proton affinity, despite nitrogen typically exhibiting higher affinity when isolated. This is due to the aromatic stabilization in pyrrole, which reduces the nitrogen atom’s basicity and its ability to attract and bind protons, resulting in a lower proton affinity compared to that of isolated oxygen in the methoxy group.

These observations suggest that reactivity and energy gaps may not align with trends in proton affinity. Oxygen, having higher electronegativity, demonstrates a correspondingly higher proton affinity28. Substituting the methoxy group in EMAB with a pyrrole group enhances reactivity but decreases the overall proton affinity.

Molecular electrostatic surface potential (MESP) maps

The ESP map is related to nucleophilic and electrophilic activity sites in molecules; the red refers to the negative region and the green and blue ones refer to the positive regions33. In EMAB, high electron density areas include the ester end of the molecule, likely due to the presence of two oxygen atoms in that vicinity, as well as the oxygen-bearing –O–H group. To a lesser extent, the methoxy oxygen also contributes to this electron density. The nitrogen-hydrogen environment in the pyrrole ring shows blue regions, indicating some degree of positive charge. Consequently, the potential for attracting a proton in this area is low, as reflected in the proton affinity results. Figure 6 presents the molecular electrostatic surface potential maps for A (EMAB) and B (pyrrole derivative).

In the case of the derivative, the high electron density still prevails on the ester oxygen and the hydroxyl oxygen. We also note that the pyrrole nitrogen does not seem to attract electrons. Thus, the oxygen atoms (ester) in both species according to MEP maps will easily pick up protons and become protonated. Equally, the hydroxyl and methoxy groups in EMAB have indicated a high degree of proton affinity and therefore, globally considering these aspects, EMAB would demonstrate a greater affinity for protons than its pyrrole substituent.

Local reactivity descriptors LRD-Fukui functions

In EMAB, regions of high electron density are predominantly located at the ester end of the molecule, likely attributable to the presence of two adjacent oxygen atoms, as well as the –O–H group. Additionally, the methoxy oxygen contributes to the electron density, albeit to a lesser extent. The nitrogen-hydrogen environment within the pyrrole ring displays blue regions, indicative of a partial positive charge. As a result, the capacity of this area to attract protons is diminished, as evidenced by the proton affinity data. Figure 6 illustrates the molecular electrostatic surface potential maps for both EMAB and its derivative.

The value of \(\:{f}_{k}^{+}-{f}_{k}^{-}\:\)condensed to the \(\:{k}^{th}\) atom in a molecule is calculated from atomic charges or Fukui functions. Table 7 depicts Fukui functions for the electrophilic and nucleophilic centers for atoms in EMAB and its derivative, calculated at the CAM-B3LYP(D3)/Def2-TZVP level of theory. The LRDs were calculated based on Hirshfeld population analysis as implemented in Gaussian 09 Rev. D01 program15.

The Hirshfeld population analysis scheme was used herein because it provides accurate and all-positive Fukui function values and because it is not basis set dependent48. In all cases under study, the values of the Fukui functions are non-negative and those of the dual descriptor \(\:{\varDelta\:f}_{k}\left(r\right)\) lie between − 1 and 1, the normal range47. This confirms that the LRDs computed in this work are valid. When \(\:{\varDelta\:f}_{k}\left(r\right)\) > 0, atom \(\:k\) acts as an electrophile or is favorable for nucleophilic attack. Conversely, if \(\:{\varDelta\:f}_{k}\left(r\right)\) < 0, atom \(\:k\) is susceptible to electrophilic attack or would act as a nucleophile32,47. It should be noted that although the dual descriptor is used to determine local reactivity, it is suitable for comparing only the reactivity of molecules of the same sizes or with the same number of electrons. In such cases where electron number or atom number changes for molecules to be compared, it is replaced with the local hyper softness \(\:\left(\varDelta\:S\right(r\left)\right)\) as follows:

The interpretations of \(\:{\varDelta\:f}_{k}\left(r\right)\) and \(\:\left(\varDelta\:S\right(r\left)\right)\)are similar; they are positive in electrophilic regions and negative in nucleophilic regions31,32. For EMAB, O10, O15 and N18 are nucleophilic and therefore will readily pick up protons from the surrounding medium, based on their \(\:\:{\Delta\:}\text{f}\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:{\Delta\:}\text{s}\:\) values (negative for electron-rich centers).

i.e. 10 O −0.011768 and −0.00143746, for 15 O −0.002769 and 0.00033823, for 18 N. −0.015699 and − 0.00191763 respectively.

This indicates the ability of many atoms to have affinity for the protons in the surrounding medium. For the case of EMAB’s substituent, the only heteroatom with a negative value for \(\:\varDelta\:f\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:\varDelta\:s\) is \(\:42\) N, with values \(\:-0.01176\) and\(\:\:-0.00034424\). Thus, this is the only nucleophilic heteroatom. These results again agree with those obtained for proton affinity and molecular electrostatic surface potential maps, indicating that EMAB, based on its ability to attract protons, can be used as a good corrosion inhibitor for mild steel. Based on the results obtained from DFT and molecular mechanics methods, we conclude that EMAB, the parent molecule in this study, is a better corrosion inhibitor for mild steel, given that majority of the methods agree with this fact.

Second order Fukui functions

The second order Fukui Functions were calculated to determine the change in electron density of each molecule when an electron is added or removed from the neutral molecule. These calculations were based on the energies of the neutral, the anionic and cationic species, as earlier depicted in Eqs. 10 and 11. The energies of the various species (in Hartree) and the corresponding values for the second order Fukui functions for nucleophilic and electrophilic attacks (in Hartree/electron) for the molecules are presented in Table 8.

The second-order Fukui functions of EMAB and its pyrrole derivative offer important insights into their potential as corrosion inhibitors, particularly regarding their nucleophilic and electrophilic properties. EMAB has a nucleophilic Fukui function of 0.243 H, indicating a stronger ability to donate electrons (through the methoxy group) compared to its derivative’s value of 0.221 H, (donating through a weaker pyrrole group). This suggests that EMAB may be more effective in stabilizing metal surfaces. In contrast, the pyrrole derivative has a less negative electrophilic Fukui function of −0.565 H, while EMAB’s is −0.594 H, indicating that the pyrrole derivative has a slightly better capacity to accept electrons and could potentially adsorb onto negatively charged sites.

Furthermore, the ability of these molecules to accept protons enhances their corrosion inhibition mechanisms. EMAB’s stronger nucleophilic character facilitates interactions with acidic environments, allowing it to capture protons that typically initiate corrosion processes in such conditions. As a result, EMAB is identified as a superior corrosion inhibitor, particularly in proton-rich environments, due to its higher nucleophilic Fukui function that enables more effective engagement, ultimately mitigating corrosion.

In conclusion, the results suggest that EMAB is particularly well-suited for use as a corrosion inhibitor especially in acidic or proton-rich environments, reinforcing its potential for practical applications in corrosion prevention.

Conclusion

Monte Carlo simulations indicate that both EMAB and its pyrrole derivative can effectively adsorb on the Fe(110) surface. The total and adsorption energies for EMAB are generally lower than those for the pyrrole derivative, suggesting greater stability for EMAB when adsorbed. Both inhibitors exhibit negative adsorption and deformation energies, indicating stability on the metal surface. Their parallel orientations enhance surface coverage and corrosion inhibition efficacy. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations reveal a high probability of adsorption at approximately 1.1 Å from the iron (110) surface, attributed to the presence of heteroatoms. The peak radial distribution function (RDF) value for EMAB (489.56) surpasses that of the derivative (437.6), confirming that EMAB is a more effective inhibitor. Additionally, higher proton affinity values and more pronounced electrostatic potential around nucleophilic atoms in EMAB further support its superior inhibition capability. While global reactivity descriptors suggest the pyrrole derivative might be a better inhibitor due to a lower energy gap, solvent effects appear minimal, as both in-solution and out-of-solution results are similar. Our findings demonstrate that MD simulations, which capture dynamic processes over longer time scales, complement density functional theory (DFT) results, particularly in understanding transient states relevant to inhibition. In summary, local reactivity descriptors effectively elucidate the anti-corrosion properties of molecules by detailing interactions with the substrate, while global descriptors serve as a useful preliminary screening tool.

While computational descriptors indicate promising characteristics for the pyrrole derivative, the final assessment of corrosion inhibition effectiveness may be influenced by various factors, including molecular interactions with the steel surface, solubility, and environmental conditions.

To validate our findings, we will conduct the following experiments in our next study:

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): This will allow us to measure the transfer resistance and provide insights into the protective layer formed by both compounds.

Potentiodynamic Polarization Studies: These will help evaluate the corrosion rates and inhibition efficiencies of EMAB and the pyrrole derivative under standardized conditions.

Surface Analysis Techniques: Techniques such as Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) will be employed to visualize the surface morphology and monolayer formation of the inhibitors on the mild steel surface.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Obot, I., Haruna, K. & Saleh, T. Atomistic simulation: a unique and powerful computational tool for corrosion Inhibition research. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 44, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-018-3605-4 (2019).

Nassar, A., Hassan, A., Shoeib, M., Kmash, E. & A Synthesis, characterization and anticorrosion studies of new homobimetallic Co (II), Ni (II), Cu (II), and Zn (II) schiff base complexes. J. Bio-and Tribo-Corrosion. 1, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40735-015-0019-7 (2015).

Olasunkanmi, L. O., Obot, I. B., Kabanda, M. M. & Ebenso, E. E. Some quinoxalin-6-yl derivatives as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in hydrochloric acid: experimental and theoretical studies. J. Phys. Chem. C. 119 (28), 16004–16019. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b03285 (2015).

Shetty, P. Schiff bases: an overview of their corrosion Inhibition activity in acid media against mild steel. Chem. Eng. Commun. 207 (7), 985–1029. https://doi.org/10.1080/00986445.2019.1630387 (2020).

Betti, N., Al-Amiery, A. A. & Al-Azzawi, W. K. Experimental and quantum chemical investigations on the anticorrosion efficiency of a nicotinehydrazide derivative for mild steel in HCl. Molecules 27 (19), 6254. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27196254 (2022).

Njong, R. N., Ndosiri, B. N., Nfor, E. N. & Offiong, O. E. Corrosion inhibitory studies of novel schiff bases derived from hydralazine hydrochloride on mild steel in acidic media. Open. J. Phys. Chem. 8 (01), 15–32. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojpc.2018.81002 (2018).

Gupta, S. R., Mourya, P., Singh, M. & Singh, V. P. Synthesis, structural, electrochemical and corrosion Inhibition properties of two new ferrocene schiff bases derived from Hydrazides. J. Organomet. Chem. 767, 136–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JORGANCHEM.2014.05.038 (2014).

Kiven, D. E., Nkungli, N. K., Tasheh, S. N. & Ghogomu, J. N. In Silico screening of Ethyl 4-[(E)-(2-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl) methyleneamino] benzoate and some of its derivatives for their NLO activities using DFT. Royal Soc. Open. Sci. 10 (1), 220430. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.220430 (2023).

Labet, V. et al. Characterization of the chemical reactivity and selectivity of DNA bases through the use of DFT-based descriptors. Structure, bonding and reactivity of heterocyclic compounds, 35–70. (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-45149-2_2

Kaya, S., Banerjee, P., Saha, S. K., Tüzün, B. & Kaya, C. Theoretical evaluation of some benzotriazole and Phospono derivatives as aluminum corrosion inhibitors: DFT and molecular dynamics simulation approaches. RSC Adv. 6 (78), 74550–74559. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6RA14548E (2016). Article information.

Sarkar, U. et al. A conceptual DFT approach towards analysing toxicity. J. Chem. Sci. 117, 599–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02708367 (2005).

Yang, W. & Mortier, W. J. The use of global and local molecular parameters for the analysis of the gas-phase basicity of amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 108 (19), 5708–5711. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00279a008 (1986).

Politzer, P. & Murray, J. S. The fundamental nature and role of the electrostatic potential in atoms and molecules. Theor. Chem. Acc. 108, 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00214-002-0363-9 (2002).

Odewole, O. A. et al. Synthesis and anti-corrosive potential of schiff bases derived 4-nitrocinnamaldehyde for mild steel in HCl medium: experimental and DFT studies. J. Mol. Struct. 1223, 129214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129214 (2021).

Frisch, M. et al. Gaussian 09, Revision D. 01; Gaussian, Inc: Wallingford, C (2015). https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21615

Dennington, R., Keith, T. A. & Millam, J. M. Gauss View 6.0. 16. Semi Chem Inc143–150 (Shawnee Mission, KS, 2016).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wave function analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33 (5), 580–592. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.22885 (2012).

Zhurko, G. & Zhurko, D. ChemCraft, version 1.6. URL: (2009). http://www.chemcraftprog.com

Pahonțu, E. et al. Synthesis, characterization, crystal structure and antimicrobial activity of copper (II) complexes with the schiff base derived from 2-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde. Molécules 20 (4), 5771–5792. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules20045771 (2015).

Sathiyanarayanan, S., Marikkannu, C. & Palaniswamy, N. Corrosion Inhibition effect of tetramines for mild steel in 1 M HCl. Appl. Surf. Sci. 241 (3–4), 477–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2004.07.050 (2005).

John, S., Joseph, A., Sajini, T. & Jose, A. J. Corrosion Inhibition properties of 1, 2, 4-hetrocyclic systems: electrochemical, theoretical and Monte Carlo simulation studies. Egypt. J. Petroleum. 26 (3), 721–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpe.2016.10.005 (2017).

Albrakaty, R. H., Wazzan, N. A. & Obot, I. Theoretical study of the mechanism of corrosion Inhibition of carbon steel in acidic solution by 2-aminobenzothaizole and 2-mercatobenzothiazole. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 13 (4), 3535–3554. https://doi.org/10.20964/2018.04.50 (2018).

Amin, M. A., Khaled, K., Mohsen, Q. & Arida, H. A study of the Inhibition of iron corrosion in HCl solutions by some amino acids. Corros. Sci. 52 (5), 1684–1695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2010.01.019 (2010).

Akkermans, R. L., Spenley, N. A. & Robertson, S. H. Monte Carlo methods in materials studio. Mol. Simul. 39 (14–15), 1153–1164. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927022.2013.843775 (2013).

Fu, J. et al. Experimental and theoretical study on the Inhibition performances of Quinoxaline and its derivatives for the corrosion of mild steel in hydrochloric acid. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 51 (18), 6377–6386. https://doi.org/10.1021/IE202832E (2012).

Nwankwo, H. U., Olasunkanmi, L. O. & Ebenso, E. E. Experimental, quantum chemical and molecular dynamic simulations studies on the corrosion Inhibition of mild steel by some carbazole derivatives. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 2436. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-02446-0 (2017).

Galano, A. & Raúl Alvarez-Idaboy, J. Computational strategies for predicting free radical scavengers’ protection against oxidative stress: where are we and what might follow? Int. J. Quantum Chem. 119 (2), e25665. https://doi.org/10.1002/qua.25665 (2019).

Saha, S. K., Hens, A., Murmu, N. C. & Banerjee, P. A comparative density functional theory and molecular dynamics simulation studies of the corrosion inhibitory action of two novel N-heterocyclic organic compounds along with a few others over steel surface. J. Mol. Liq. 215, 486–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2016.01.024 (2016).

Verma, P. & Truhlar, D. G. Status and challenges of density functional theory. Trends Chem. 2 (4), 302–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trechm.2020.02.005 (2020).

Tan, T. et al. Passiflora Edulia sims leaves extract as renewable and degradable inhibitor for copper in sulfuric acid solution. Colloids Surf. 645 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.128892 (2022).

Cárdenas, C. et al. Chemical reactivity descriptors for ambiphilic reagents: dual descriptor, local hypersoftness, and electrostatic potential. J. Phys. Chem. A. 113 (30), 8660–8667. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp902792n (2009).

Guégan, F., Mignon, P., Tognetti, V., Joubert, L. & Morell, C. Dual descriptor and molecular electrostatic potential: complementary tools for the study of the coordination chemistry of ambiphilic ligands. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16 (29), 15558–15569. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CP01613K (2014).

Oukhrib, R. et al. DFT, Monte Carlo and molecular dynamics simulations for the prediction of corrosion Inhibition efficiency of novel Pyrazolyl nucleosides on Cu(111) surface in acidic media. Sci. Rep. 11, 3771. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-82927-5 (2021).

Gupta, S. K. et al. Electrochemical, surface morphological and computational evaluation on carbohydrazide schiff bases as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in acidic medium. Sci. Rep. 13, 15108. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41975-9 (2023).

Valbon, A. et al. The Corrosion Inhibition Performance of Eco-Friendly bis-Schiff Bases on Carbon Steel in a Hydrochloric Solution. Surfaces, 6(4), 509–532. Doi.10.3390/surfaces6040034 (2023).

Hosny, S., Abdelfatah, A. & Gaber, G. A. Synthesis, characterization, synergistic inhibition, and biological evaluation of novel schiff base on 304 stainless steel in acid solution. Sci. Rep. 14 (470). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-51044-w (2024).

Berisha, A. Experimental, Monte Carlo and molecular dynamic study on corrosion Inhibition of mild steel by pyridine derivatives in aqueous perchloric acid. Electrochem 1 (2), 188–199. https://doi.org/10.3390/electrochem1020013 (2020).

Castillo-Robles, J. M. et al. Molecular modeling applied to corrosion inhibition: a critical review. Mater. Degrad. 8, 72. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-024-00478-2 (2024).

Ahmad, F. et al. Discovery of Potential Antiviral Compounds against Hendra Virus by Targeting Its Receptor-Binding Protein Using Computational Approaches. Molecules. 16;27(2):554. (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27020554

Khabazi, E. M. & Chermahini, A. N. DFT study on corrosion Inhibition by tetrazole derivatives: investigation of the substitution effect. ACS Omega. 8 (11), 9978–9994. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c07185 (2023).

Matine, A. et al. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of a pyrazole-based corrosion inhibitor: a computational and experimental study. Sci. Rep. 14, 25238. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76300-5 (2024).

Khamis, E. et al. Innovative application of green surfactants as eco-friendly scale inhibitors in industrial water systems. Sci. Rep. 14, 28073. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78879-1 (2024).

Sun, Y., Hu, L. & Chen, H. Comparative assessment of DFT performances in Ru- and Rh-Promoted σ-Bond activations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 14;11 (4), 1428–1438. https://doi.org/10.1021/ct5009119 (2015).

Ahn, D. H. & Song, J. W. Assessment of long-range corrected density functional theory on the absorption and vibrationally resolved fluorescence spectrum of carbon nanobelts. J. Comput. Chem. 15 (7), 505–515. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.26473 (2021).

Martinez, S. Inhibitory mechanism of mimosa tannin using molecular modeling and substitutional adsorption isotherms. Mater. Chem. Phys. 77, 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0254-0584(01)00569-7 (2003).

Obot, I. B., Kaya, S., Kaya, C. & Tüzün., B. Density functional theory (DFT) modeling and Monte Carlo simulation assessment of Inhibition performance of some carbohydrazide schiff bases for steel corrosion. Phys. E: Low-dimensional Syst. Nanostruct. 80, 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physe.2016.01.024 (2016).

Morell, C., Grand, A. & Toro-Labbé, A. New dual descriptor for chemical reactivity. J. Phys. Chem. 109, 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp046577a (2005).

Hirshfeld, F. L. Bonded-Atom fragments for describing molecular charge densities. Theoret. Chim. Acta. 44, 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00549096 (1977).

Fradera, X. & Sola, M. Second order Fukui indices from the electron pair density in the framework of the atoms in molecules theory. J. Comput. Chem. 25 (3), 439–446. Doi.org/10.002/jcc10396 (2004).

Wang, B., Gerlings, P., Liu, S. & De Proft, F. Extending the scope of conceptual density functional theory with second order analytical methodologies. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 20 (3), 1169–1184. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.3c01184 (2024).

Parr, R. & Yang, W. Density Functional Theory of Atoms and Molecules (Oxford University Press, 1999).

Liu, S. & Parr, R. G. Second-Order Density-Functional description of molecules and chemical changes. J. Chem. Phys. 106 (13), 5578–5586. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.473580 (1997).

Guo, L. et al. Toward Understanding the adsorption mechanism of large size organic corrosion inhibitors on an Fe(110) surface using the DFTB method. Royal Soc. Chem. Adv. 7, 29042–29050. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7RA04120A (2017).

Satoh, S., Fujimoto, H. & Kobayashi, H. Theoretical study of NH3 adsorption on Fe(110) and Fe(111) surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. 110, 4846–4852. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp055097w (2006).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the research modernization grants to lecturers of tertiary education by the Cameroonian Ministry of Higher Education, which served as a support for this project.

Funding

We received no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.E.K.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; N.K.N.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, writing—review and editing; S.N.T.: investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing; F.K Bine: methodology, validation, writing—review; J.N.G.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision and validation. All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kiven, D.E., Nkungli, N.K., Tasheh, S.N. et al. Computational investigation of anticorrosion properties in Ethyl 4-[(E)-(2-Hydroxy-4-Methoxyphenyl)Methyleneamino]Benzoate and its pyrrole substituted variant on mild steel. Sci Rep 15, 40420 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17836-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17836-y