Abstract

Salinity stress is a devastating environmental issue among abiotic stresses. It has severely affected global crop production. It has become crucial for scientists to unearth new strategies for mitigating salinity stress. In this study, a completely randomized experimental design was formulated. Two cultivars (Super and Sandal) of Brassica napus L. were utilized in this work. The treatments applied in this study included NaCl (100 mM), nitric oxide (NO; 150 µM) and arginine (Arg; 0.5 mM). The results revealed that, compared with those of the control plants, the growth, chlorophyll content, relative water content, total soluble protein, K+ and Ca2+ contents of the shoots and roots, and yield parameters were lower under salt stress. The membrane permeability, malondialdehyde, H2O2, total phenolics, free proline, catalase, peroxidase and ascorbate peroxidase activities, and sodic level were increased under salinity. In contrast, foliar sprays of NO and Arg and their combined application significantly increased the plant growth, chlorophyll content, RWC, total soluble protein, K+ and Ca2+ contents and yield parameters of canola in stressed and control plants. These supplements reduced the membrane permeability and MDA, H2O2, Na+ and Cl− contents but increased the total phenolics, free proline, and antioxidant enzymes activities in stressed plants. The findings of this study demonstrated that NO and Arg have potential roles in mitigating the toxic effects of salinity and can increase plant growth and yield.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Salinity affects the production of crops and has become a global issue1. Salinity causes water stress, oxidative stress and the imbalance of ions/minerals, thus decreasing plant growth2. With the global population projected to reach approximately 9 billion by 2050, alongside a rising demand for resource-intensive foods, it is imperative to determine how food production and distribution can be sustained on a shrinking area of arable land3. Salinity increases daily due to poor irrigation practices, seepage, silting, and rising water tables4. One 3rd of the farmland has been affected by soil salinity and is now the most severe challenge. After 28 years, according to an estimation, half of the irrigated land would be affected by salinity5. Low annual rainfall is also a cause of salt spreading and affects soil6. The soluble salts that accumulate in soils that affect agriculture and ecology are termed salinity7. Soil salinity is a threat to agriculture because it limits the productivity of crop and plant growth8.

The activity of plants is strongly affected by salt stress, and the morphological and physiological characteristics, biochemical parameters, and metabolic and molecular characteristics of almost all plants are altered in response to salt stress9. The deleterious effects of salt stress on plants include limited nutrient uptake, ionic imbalance, and a reduction in growth10. Salt is highly absorbed by the cytoplasm or chloroplasts of mesophyll cells, which reduces the activity of photosynthesis-related enzymes under high salt stress11. The ionic tolerance of plants is caused by the activation of various signals triggered by salt entry into the root system, the net influx of Na+ in the roots and the translocation of Na+ toward the shoot12. Many metabolic activities, such as photosynthesis, respiration and transpiration, are disrupted by salt stress13. Salinity stress further alters oxidative and osmotic stress. Indirect changes in the concentration of salt affect the osmotic balance, which in turn obstructs the mechanism of water uptake in plants14.

Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) is an important oilseed crop throughout the world. Canola is a bright yellow flowering plant also known as crucifer and belongs to the Brassicaceae family. After soybean and palm oil, canola is one of the healthiest crops and was introduced as the third most important source of vegetable oil, since Pakistan’s largest food import, edible oil, ranks third on the import list, with more than 80% of the country’s needs dependent on imports15. Among vegetable oils, the lowest content of saturated fatty acids is present in canola oil, and due to low fatty acid contents, there is a growing demand for diet consumers16.

Canolas contain 40% high-quality oil, which is a significant part of human meal. Proteins in canola oil contain amino acids, including lysine, methionine and cystine. Canola oil has protein contents in large quantities, including napin and cruciferin, and contains less than 2% erucic acid and less glucosinolate17. Canola is cultivated globally, with major production regions located in Asia, Europe, North America, and Oceania18.

Sodium nitroprusside (SNP) is generally used as a donor of nitric oxide (NO) in plant experiments and requires a reduction in electrons and irradiation with light to liberate NO in plants19. NO is a vital biomolecule involved in the tolerance of plants to salt stress. NO also plays an important role in many plant development processes20. NO in plants plays different roles under normal or stressed conditions to improve the growth and productivity of plants21. NO prevents direct oxidative damage by decreasing the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS). NO has been shown to function as a phytohormone. NO is also involved as a signal in the hormonal response, and NO is involved in defense reactions in the majority of plants22. NO is a potent antioxidant and redox activator because it has a signaling function. NO promotes defense gene expression and activates signaling under stress. The antioxidant defense mechanism is activated by the exogenous use of NO under stress conditions23. Furthermore, the concentration of NO in plants increased under salt stress, which helps to regulate various physiological processes. Seed germination, photosynthesis, nutrient uptake, oxidative stress, osmotic balance, respiration, and gene expression are included in these physiological processes24.

Arginine (Arg) is used for the biosynthesis of polyamines, and Arg produces cell signaling molecules for the synthesis of NO25. The plants are exposed to stressful environments for this reason; stress inhibits most processes in plants, and this effect is alleviated by the positive role of Arg. Polyamines of Arg and their precursors have been used as important modulators of various processes related to growth characteristics, physiological characteristics and development processes in higher plants26,27. It is a vital component of proteins and serves as a precursor for the synthesis of a variety of biomolecules, proline and polyamines28. Arg reduces the inhibitory effects of salt stress on plant growth13.

Studies have reported the ameliorative role of Arg and NO against abiotic stresses. Hussein et al.29 found that T. estivum grains primed with 1 mM Arg showed improved growth under drought conditions. In another study, Sun et al.30 revealed that Arg treatment (150 µmol L− 1) improved growth of maize plants under drought stress. Similarly, NO root application in the form of sodium nitroprusside (100 µM) remarkably improved yield of chili plants given 100 mM of NaCl stress31. Hamurcu et al.20 revealed that addition of 100 µM sodium nitroprusside (donor of NO) modulated antioxidative activities in C. lanatus plants to improve drought stress tolerance. Despite this all none of the studies have reported synergistic application of Arg and NO to ameliorate salt stress in B. napus plants. Abiotic stresses adversely affect the growth and physiochemical characteristics of B. napus32.

It is hypothesized that foliar application of Arg and NO, individually and synergistically, will mitigate the adverse effects of salinity stress in B. napus cultivars by enhancing growth, photosynthetic efficiency, antioxidant defense mechanisms, membrane stability, and ionic homeostasis. The exogenous application of Arg, as a precursor of both polyamines and NO, is expected to promote osmotic adjustment and secondary metabolite production, while NO, as a key signaling molecule, is anticipated to modulate antioxidant enzyme activities and nutrient uptake. Their combined application is hypothesized to exhibit a crosstalk, leading to synergistic effects that provide superior protection against salt-induced oxidative damage, thereby improving plant vigor, physiological performance, and yield components under saline conditions. The objectives of this research were to observe the morphological, biochemical and physiological attributes of B. napus plants under salinity stress and to assess the potential role of Arg and NO in mitigating salt stress.

Materials and methods

Experimental design and plant material

This experiment was conducted under natural conditions at the Botanical Garden, University of Education, Lahore. Throughout the experimental period, the average day/night temperatures were 28.5°C and 18°C, respectively, with a relative humidity of 60% and total precipitation of 24 mm. The study followed a four-factorial completely randomized design (CRD). Seeds of B. napus cultivars, namely ‘Super’ and ‘Sandal’, were procured from the Ayub Agricultural Research Institute, Faisalabad. Plastic pots (20 × 25 cm) were filled with 6.5 kg of pre-washed sand. To meet the nutrient requirements of the plants, half-strength Hoagland’s nutrient solution was supplied at one-week intervals, following the method of Hoagland and Arnon (1938). Approximately ten healthy seeds were sown per pot at uniform spacing. After germination, seedlings were thinned to retain four to five uniformly vigorous plants per pot, ensuring even distribution. Two weeks after germination, the following treatments were initiated: foliar application of arginine (Arg; 0.5 mM) and sodium nitroprusside (NO; 150 µM), individually and in combination, to both control (unstressed) and salt-stressed (100 mM NaCl) plants. The concentrations of Arg and NO were selected partially based on previous literature13,33. Salinity stress was imposed by irrigating the plants with a 100 mM NaCl solution at the rate of 1 L per pot, along with Hoagland’s solution, according to the method of Usman et al.13. Foliar sprays of Arg and NO were prepared with 0.1% Tween-20 as a surfactant and applied manually using a hand sprayer until complete wetting of the foliage was achieved. Control plants received an equivalent volume of distilled water containing 0.1% Tween-20. Treatments were applied three times at weekly intervals. Two weeks after the final foliar application, data were collected for growth parameters and various physiological and biochemical attributes to assess the effects of treatments under salt stress conditions.

Estimation of chlorophyll contents

The protocol of Arnon34, was used to determine the chlorophyll and carotenoid contents. Fresh leaves were collected from each pot, 0.5 g were weighed via an electronic balance, and the samples were ground with a mortar and pestle in 10 mM 80% acetone. The crushed material was filtered with Whatman filter paper, the filtrate was stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C overnight, and the extracts were exposed at wavelengths of 480, 645 and 663 nm. A UV‒visible spectrophotometer was used to determine the absorbances.

Estimation of malondialdehyde (MDA)

The MDA content present in the canola plants was determined via the method of Cakmak & Horst et al.35. For this experiment, fresh and clean leaves were collected from each pot, and 1.0 g of plant material was crushed into 3 millilitres of 1% (TCA) at 4°C with the help of a mortar and pestle. The resulting grinding mixture was subsequently transferred to conical tubes, and the process of centrifugation was performed at 20,000 × g for 15 min. For further experiments (TBA), a 0.5% thiobarbituric acid solution was prepared in a 1000 mL glass beaker by adding 0.5 g of thiobarbituric acid to 100 mL of distilled water. In test tubes, 3 mL of 0.5% (v/v) TBA and 20% TCA were added to half of the supernatant, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The samples were then heated in a shaking water bath for 15 min at 95°C, and the reaction was stopped by placing the samples in an ice water bath. When the samples were cooled, centrifugation was performed at 10,000 ×g for 10 min. Then, the absorbance of the samples was recorded at 532 and 600 nm, and the readings were recorded via a UV‒visible spectrophotometer.

Determination of H2O2

For the determination of H2O2 content, the method of Velikova et al.36 was used. Fresh plant leaves were taken from each pot, and 0.5 g of each leaf was weighed. The weighed leaves were ground with a cooled mortar and pestle by adding 5 millilitres of 0.1% (w/v) TCA. Then, the crushed material was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min, and the resulting supernatant from the extract was isolated and transferred to test tubes. For further analysis, 0.5 mL of the supernatant was mixed with 1 mL of potassium iodide (KI) and 0.5 mL of potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) in test tubes, after which the mixture was vortexed for 30 min at room temperature. The absorbance of each sample was measured at a wavelength of 390 nm by keeping the mixture in a UV‒visible spectrophotometer.

Determination of membrane permeability (%)

The relative permeability of the membrane was calculated using the protocol of Yang et al.37. The youngest expanded leaves of uniform size were separated from all the tested plants. For mixture preparation, all the leaves of all the samples were chopped and then placed in test tubes, each containing 20 mL of distilled water. All test tubes were correctly labeled and vortexed for almost 5 s, and the EC0 of the mixture was recorded via a pH meter. The test tubes were subsequently incubated at 4°C for 24 h, after which the value of EC1 was calculated. All the samples were kept in an autoclave at 120 °C for 20 min, after which the final value, i.e., EC2, was determined.

Analysis of relative water content (RWC)

To calculate the relative water content, the method of Jones & Turner38, was used. Fresh leaves of uniform size were pooled from each replicate, and the fresh weight was noted. Leaves were placed directly on distilled water in a Petri dish and left for 3 h in the dark at room temperature. The turgid weight of the leaves was subsequently recorded. Finally, the samples were dried in an oven for 24 h at 80 °C, and the leaf dry weights were measured.

Estimation of total soluble protein

The protein contents of the canola cultivars were determined via the Bradford39, protocol. Approximately 1000 mL of Bradford reagent was prepared by dissolving 50 mL of 95% ethanol, 100 mL of 85% phosphoric acid and 0.1 g of Coomassie brilliant blue in 850 mL of distilled water.

For the extraction of protein from leaves, 0.5 g of fresh leaves was weighed, and the samples were ground with 10 mL of 50 mM cold phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) in a cooled mortar and pestle. The extract was subsequently transferred to conical tubes and centrifuged at 6000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, after which the resulting supernatant was separated from the residue and stored in test tubes for protein calculation. The absorbance of the total soluble protein content in the supernatant extract (0.1 ml) was calculated by adding 2 ml of Bradford reagent at 595 nm via a UV‒visible spectrophotometer.

Analysis of catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POD) and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity

The activities of catalase and peroxidase were observed in the plant extracts according to the methods of Chance & Maehly40with slight modifications. The reaction mixture for the CAT enzyme (3 mL) contained 1 ml of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and 1.9 ml of 5.9 mM H2O2. Then, 0.1 mL of the enzyme extract was added to the cuvette, and the reaction progressed. The sample absorbance was determined at 240 nanometers by using a UV‒visible spectrophotometer at intervals of 20 s for 2 min. One unit activity of the CAT enzyme was defined as the change in absorbance at a rate of 0.01 units per min.

Similarly, for POD, the sample for the reaction (3 mL) was prepared in test tubes by adding and mixing 0.6 mL (20 mM) guaiacol, 0.6 mL (40 mM) H2O2 and 0.7 mL of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 5.0). The reaction was initiated by the addition of the enzyme extract (0.1 mL) to a cuvette. A UV‒visible spectrophotometer was used to calculate the readings of all the samples every 20 s at 470 nanometers. The method of Nakano & Asada41 was used to measure the APX activity. The reaction mixture for APX activity (total volume of 3 ml) contained 2.7 ml of phosphate buffer solution, 0.1 ml of enzyme extract, ascorbic acid (0.1 ml) and H2O2 (0.1 ml). The samples were observed at 290 nm, and the time range was 0–60 s, as determined via a UV‒visible spectrophotometer.

To express enzyme activities as true specific activities (µmol substrate converted·min⁻¹·mg⁻¹ protein), U·mg⁻¹ values were converted using multipliers derived from the Beer–Lambert relation and the fixed assay geometry (total reaction volume 3.0 mL; sample volume 0.1 mL; path length 1.0 cm). The molar extinction coefficients used were: CAT (H₂O₂ at 240 nm), ε = 39.4 L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹; POD (guaiacol at 470 nm), ε = 26,600 L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹; APX (ascorbate at 290 nm), ε = 2,800 L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹.

Determination of phenolic content

The total phenolic compounds from the plant extracts were determined via the protocol of Julkunen-Tiitto42, . Folin-Ciocalteu reagent was used for this purpose. Fresh leaf samples (0.05 g) were homogenized in 5 mL of 80% acetone solution, and the ground extract was transferred to Falcon tubes. The samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 ×g. The samples were diluted in two mL of water and 1 ml of Folin-Ciocalteu phenol reagent, and the mixture was strongly shaken. Moreover, 5 ml of sodium carbonate (20%) was added to the mixture, and the volume was adjusted to 10 ml with distilled water. The mixture samples were vortexed, and the absorbance was calculated at a wavelength of 750 nm by using a UV‒visible spectrophotometer.

Estimation of proline

For the calculation of proline contents in canola cultivars, the method of Bates et al.43 was followed. For this experiment, fresh leaves were taken from each replicate, weighed to 0.5 g and ground in 3% sulfo-salicylic acid (10 ml). The crushed material was filtered with Whatman No. 2 filter paper. Then, 2 ml of acid ninhydrin was mixed with filtrate (2 ml), and 2 ml of glacial acetic acid was subsequently added to a test tube. The mixture was subsequently incubated in an incubator at 100 °C for 60 min. The mixture was vigorously mixed for two minutes by passing through a steam of air while adding 4 ml of toluene to the solution. The chromophore containing toluene was aspirated, and at room temperature, it was warmed. The absorbance of the solution was subsequently measured at 520 nm via a spectrophotometer, and toluene was used as a blank.

Determination of nutritional ions

To determine the ion contents of Na+, Cl−, K+ and Ca2+ ions in the leaf digest, first, the plant samples were dried in an oven at 70°C for one day. The oven-dried samples (0.1 g) of leaves were subsequently digested with 2 mL of concentrated acid H2SO4, and the solution was left for 24 h. The digestion test tubes were heated by using a hot plate. The process of heating was continued after regular intervals by adding 0.5 mL H2O2 to the digestion test tubes, which were then incubated for 30 min on a hot plate until the digestion solution was colorless. The readings were calculated by using a flame photometer for ionic content such as sodium, potassium and calcium ions44.

Mohr’s titration method was used to calculate the Cl− ion content with silver nitrate; slowly, a solution of silver nitrate was added, and a precipitate of silver chloride was produced. All the chloride ions were precipitated. Silver ions reacted with chromate ions of the indicator; potassium chromate formed a red brown precipitate of silver chromate. A silver nitrate solution (0.1 mol L− 1) was made, and 5 g of AgNO3 was allowed to dry for 2 h. at 100°C and then cooled. The solid AgNO3 (4.25 g) was weighed accurately and dissolved in 250 ml of distilled water. A brown bottle was used to store the solution. The solution was prepared by adding a potassium chromate indicator solution (0.25 mol L− 1) with one gram of K2CrO4 to 20 mL of distilled water.

Statistical analysis

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) for all attributes was performed using R software (RStudio 2024.12.0 + 467, developed by Posit Software, PBC). Graphs were made on R software. The values presented in the graphs are averages of three replicates ± standard errors. Bars sharing similar letters, obtained after Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT) are not significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Effects of ARG and NO treatment on the morphological characteristics of B. napus under salt stress

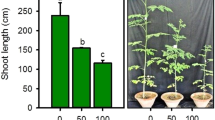

Under non-stress conditions, Arg treatment enhanced all measured growth parameters, with maximum increases in RDW (41%) and RFW (21%). NO foliar spray induced even greater improvements in RL (29%), SL (22%), and RDW (55%). Synergistic application of Arg and NO exhibited pronounced enhancements, especially in SL (28%) and SFW (60%). Exposure to 100 mM NaCl stress alone caused substantial reductions in all morphological traits, with the most marked decreases observed in SFW (26%) and RDW (23%). However, when salinity-stressed plants were supplemented with Arg or NO, significant mitigation of stress effects was observed. Arg application under stress led to notable increases in RL (41%), SL (51%), and RDW (82%) compared to NaCl-only plants. NO application under stress further elevated growth, particularly in RDW (120%) and SFW (107%). The combined application of Arg and NO under salinity stress proved most effective, enhancing RFW (76%), RDW (118%), and SDW (80%) over the NaCl-only group. In the absence of salinity stress, Arg application improved RL (26%), RFW (34%), and RDW (39%). NO treatment under non-stress conditions was more effective in increasing RFW (53%) and RDW (54%). The combined application of Arg and NO further augmented RDW (57%) and SDW (40%). NaCl stress alone led to significant suppression in growth parameters, particularly RFW (21%), SL (20%), and RDW (24%). Under salinity, Arg application improved RL (59%), RFW (65%), and RDW (72%) relative to stressed controls. NO treatment under salt stress significantly improved RL (71%), RDW (82%), and SDW (59%). The most notable improvements were seen with the combined Arg + NO treatment, with marked increases in RL (66%), RFW (69%), and SFW (69%), see Fig. 1A–F.

Synergistic effect of nitric oxide and arginine on growth and biomass of B. napus grown in salt stress. (A) Root length, (B) Shoot length, (C) Root fresh weight, (D) Root dry weight, (E) Shoot fresh weight and (F) Shoot dry weight. Graph bars presented mean of three replicates ± standard errors in error bars. Different alphabets above graph bars obtained after Duncan’s multiple range test presented mean values are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Effects of Arg and NO treatment on photosynthetic pigments of B. napus under salt stress

Chlorophyll and carotenoid contents were significantly influenced by exogenous treatments of Arg, NO and their combination under both normal and saline conditions in Super and Sandal cultivars of B. napus. Under non-stressed conditions, Arg and NO alone or together modestly enhanced pigment levels. In Super, Arg increased Chl a (25%), Chl b (11%), total chlorophyll (25%), and carotenoids (32%), while NO showed notable increases in carotenoids (43%) but minimal improvement in total chlorophyll (15%). The synergistic Arg + NO treatment resulted in a slight boost in Chl a (8%) and total chlorophyll (8%), though Chl b slightly declined (-1%). In Sandal, these treatments showed greater effectiveness: Arg led to a 18% increase in total chlorophyll and 39% in carotenoids, while NO elevated carotenoids up to 44%. Salt stress alone (NaCl 100 mM) led to significant pigment degradation, particularly in Super (Chl a: -20%, carotenoids: -30%) and Sandal (Chl a: -18%, carotenoids: -20%), confirming stress-induced chlorophyll breakdown. However, foliar application of Arg and NO under salt stress effectively reversed this decline. In Super, NaCl + NO enhanced Chl a (54%), total chlorophyll (53%), and carotenoids (106%), the highest among all treatments. NaCl + Arg also improved pigment levels substantially, while their combined application (NaCl + Arg + NO) maintained elevated levels of all pigments, notably 26% in total chlorophyll and 40% in carotenoids. Similarly, Sandal showed strong pigment recovery under combined treatments, with NaCl + Arg + NO enhancing total chlorophyll (26%) and carotenoids (39%). The NaCl + Arg and NaCl + NO treatments alone were particularly effective in Sandal, improving total chlorophyll by 43% and 37%, and carotenoids by 97% and 87%, respectively (Fig. 2A-D).

Synergistic effect of nitric oxide and arginine on photosynthetic pigments of Brassica napus grown in salt stress. (A) Chlorophyll a, (B) Chlorophyll b, (C) Total chlorophyll and (D) Carotenoids. Graph bars presented mean of three replicates ± standard errors in error bars. Different alphabets above graph bars obtained after Duncan’s multiple range test presented mean values are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Effects of ARG and NO treatment on the malondialdehyde (MDA), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content, relative membrane permeability (RMP) and water relation of B. napus under salt stress

In both Super and Sandal cultivars of B. napus, exogenous application of Arg (0.5 mM), NO (150 µM), and their combination influenced oxidative stress markers and water relations under control and salt stress (NaCl 100 mM) conditions. Under normal conditions, treatment with Arg and NO alone or in combination reduced H₂O₂ levels (up to -36% in Super and − 42% in Sandal) and RMP (up to -22% in Super and − 23% in Sandal), while enhancing RWC (13–23% in Super and 6–29% in Sandal). However, a slight increase in MDA was observed (up to 28% in Super and 26% in Sandal), possibly due to mild oxidative responses. Salt stress drastically increased MDA (87% in Super and 60% in Sandal), H₂O₂ (18% and 30%), and RMP (20% and 14%), while RWC dropped (-15% and − 26%), indicating substantial oxidative damage and impaired water balance. Application of Arg, NO and their synergistic treatment under salt stress markedly alleviated these effects. In Super, NaCl + Arg + NO reduced MDA (-17%), H₂O₂ (-44%), and RMP (-13%), while improving RWC (17%). Similarly, in Sandal, NaCl + Arg + NO lowered MDA (-20%) and H₂O₂ (-15%), with RMP decreasing (-9%) and RWC recovering substantially (53%). Notably, the highest RWC recovery was observed under NaCl + Arg (82% in Sandal) and NaCl + NO (38% in Super and 69% in Sandal), indicating a strong protective effect. These results suggest that Arg and NO, particularly in combination, play a key role in mitigating oxidative damage and maintaining cellular water status under salinity stress (Fig. 3A–D).

Synergistic effect of nitric oxide and arginine on stress markers and yield attributes of B. napus grown in salt stress. (A) Malondialdehyde (MDA), (B) Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), (C) Relative membrane permeability (RMP) and (D) Relative water content (RWC). Graph bars presented mean of three replicates ± standard errors in error bars. Different alphabets above graph bars obtained after Duncan’s multiple range test presented mean values are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Effects of ARG and NO treatment on total soluble proteins and antioxidant enzymes in B. napus under salt stress

The effects of foliar applications of Arg (0.5 mM), NO (150 µM), and their combination on oxidative enzyme activities and total soluble proteins (TSP) were evaluated in B. napus cultivars Super and Sandal under both control and NaCl-induced salinity (100 mM). In Super, Arg and NO treatments under control conditions significantly enhanced TSP (28–33%), CAT (62–74%), POD (35–57%), and APX (52–64%), while their combination (Arg + NO) showed synergistic effects with maximum increases in TSP (44%) and CAT (80%). NaCl stress alone led to a marked reduction in TSP (19%) but strongly upregulated antioxidant enzymes (CAT: 147%, POD: 111%, APX: 93%). However, under salinity, Arg, NO and their combination improved TSP (51–86%) while partially restoring enzymatic activities. The synergistic treatment was particularly effective in enhancing TSP (86%) and APX (27%) despite a modest reduction in CAT and POD activities. In Sandal, similar trends were observed where Arg and NO increased TSP (20–51%), CAT (50–54%), POD (34–56%), and APX (29–38%) under non-stressed conditions, with the Arg + NO combination moderately boosting all parameters. Salinity stress in Sandal reduced TSP (15%) but upregulated CAT (85%), POD (116%), and APX (63%). Post-stress treatments with Arg, NO and their combination significantly recovered TSP levels (75–86%), with the NO application resulting in the highest TSP increase (86%). However, CAT, POD, and APX activities declined under these treatments compared to NaCl alone, indicating a protective role of Arg and NO in stress alleviation through protein stabilization and partial modulation of the antioxidant system (Fig. 4A–D).

Synergistic effect of nitric oxide and arginine on total soluble proteins and enzymatic antioxidants of Brassica napus grown in salt stress. (A) Total soluble proteins, (B) Catalase, (C) Peroxidase and (D) Ascorbate peroxidase. Graph bars presented mean of three replicates ± standard errors in error bars. Different alphabets above graph bars obtained after Duncan’s multiple range test presented mean values are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Effects of ARG and NO treatment on total phenolics and proline content in B. napus under salt stress

In both B. napus cultivars, Super and Sandal, the foliar application of Arg (0.5 mM), NO (150 µM), and their combination influenced phenolic accumulation and proline content under normal and salt stress conditions. Under control conditions, Super showed notable increases in proline content (59%) with Arg and NO alone, and slightly lower values (50%) with their combination, while phenolics also rose significantly (21–46%). Salinity stress (NaCl 100 mM) induced a sharp rise in both phenolics (70%) and proline (88%) in Super. However, when Arg, NO and their combination were applied under salt stress, both phenolics and proline were suppressed, indicating a stress-alleviating effect of the treatments, with the most substantial recovery seen under NaCl + Arg + NO (15% phenolics, 12% proline). In Sandal, Arg, NO and their synergistic application led to enhanced phenolics (23–32%) and moderate proline accumulation (13–18%) under non-stress conditions. Salt stress alone significantly increased phenolics (48%) and proline (40%) in Sandal. Post-salinity treatments showed varied responses, where NaCl + NO and NaCl + Arg + NO maintained relatively higher phenolic levels (25–28%), while proline remained moderately elevated (13–16%) compared to the stressed control. Overall, both cultivars demonstrated stress-induced elevations in phenolics and proline, which were partially mitigated by exogenous application of Arg and NO, particularly in their combined form, suggesting a protective role in osmotic and oxidative stress regulation (Fig. 5A,B).

Synergistic effect of nitric oxide and arginine on non-enzymatic antioxidants in Brassica napus grown in salt stress. (A) Total phenolics and (B) Proline content. Graph bars presented mean of three replicates ± standard errors in error bars. Different alphabets above graph bars obtained after Duncan’s multiple range test presented mean values are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Effects of ARG and NO treatment on Na+, K+, Ca2+ and Cl− ions in the roots of B. napus under salt stress

Root ion balance in B. napus cultivars Super and Sandal exhibited significant modulation in response to foliar application of Arg, NO and their synergistic combination under normal and saline conditions. In non-stressed plants, Arg and NO treatments markedly enhanced potassium (K) and calcium (Ca) accumulation while reducing sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl) contents. In Super, Arg treatment led to increases of 13% in K and 25% in Ca, while NO elevated K and Ca by 16% and 38%, respectively, with concurrent reductions in Na and Cl levels. The combined Arg + NO application further improved K and Ca concentrations, though the reduction in Na was slightly less pronounced compared to individual treatments. Sandal followed similar trends, with Arg and NO treatments boosting root K by up to 28% and Ca by 21%, while effectively lowering Na and Cl accumulation. Salt stress (NaCl 100 mM) alone severely disrupted ion homeostasis, causing significant declines in root K and Ca contents (up to -33% and − 25%) and increases in Na and Cl accumulation. However, under salt stress, the application of Arg and NO—particularly their combination—remarkably restored ion balance. In Super, NaCl + Arg + NO treatment enhanced root K by 110% and Ca by 49%, while substantially decreasing Na (-28%) and Cl (-27%) levels. Similarly, in Sandal, NaCl + Arg + NO increased root K by 32% and Ca by 34%, along with pronounced reductions in Na (-37%) and Cl (-24%). Overall, Arg and NO foliar applications, individually and synergistically, demonstrated strong potential to enhance nutrient ion uptake and alleviate toxic ion accumulation in roots under saline stress, contributing to improved plant stress resilience (Fig. 6A–D).

Synergistic effect of nitric oxide and arginine on nutritional and inorganic ions in root of B. napus grown in salt stress. (A) Sodium, (B) Potassium, (C) Calcium and (D) Chlorine. Graph bars presented mean of three replicates ± standard errors in error bars. Different alphabets above graph bars obtained after Duncan’s multiple range test presented mean values are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Effects of ARG and NO treatment on Na+, K+, Ca2+ and Cl− ions in the shoots of B. napus under salt stress

The shoot ion homeostasis of B. napus cultivars Super and Sandal was markedly influenced by foliar applications of Arg, NO and their synergistic combination under both non-stressed and salt-stressed conditions. In non-stressed plants, exogenous Arg and NO treatments enhanced essential nutrient uptake while suppressing toxic ion accumulation. In Super, Arg increased shoot potassium (K) by 27% and calcium (Ca) by 15%, while reducing sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl) by 14% and 22%, respectively. NO treatment further improved Ca uptake (25%) and reduced Na accumulation (-21%). A similar trend was observed with the Arg + NO combination, improving K and Ca contents while minimizing Na and Cl levels. In Sandal, comparable patterns were recorded, with Arg and NO enhancing K and Ca by up to 21% and 28%, respectively, while reducing Na and Cl concentrations. Salinity stress alone (NaCl 100 mM) drastically disrupted ion balance, with increased Na and Cl accumulation (up to 19% and 9% in Super, and 10% and 14% in Sandal) and reduced K and Ca uptake. However, foliar applications of Arg and NO under saline conditions significantly restored ion homeostasis. In Super, NaCl + NO treatment enhanced shoot K (44%) and Ca (35%) while reducing Na and Cl by 25% and 29%, respectively. Similarly, in Sandal, NaCl + NO improved shoot K by 51% and Ca by 40%, while decreasing Na and Cl contents. The combined application of NaCl + Arg + NO further strengthened these effects, particularly increasing Ca content by 52% in Sandal. Overall, Arg and NO, especially in combination, effectively enhanced nutrient uptake (K and Ca) and mitigated Na and Cl toxicity under salt stress, promoting better ionic balance essential for plant growth and stress tolerance (Fig. 7A–D).

Synergistic effect of nitric oxide and arginine on nutritional and inorganic ions in shoot of B. napus grown in salt stress. (A) Sodium, (B) Potassium, (C) Calcium and (D) Chlorine. Graph bars presented mean of three replicates ± standard errors in error bars. Different alphabets above graph bars obtained after Duncan’s multiple range test presented mean values are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Effects of ARG and NO treatment on yield attributes of B. napus under salt stress

Salinity stress significantly impaired the reproductive performance of B. napus, as indicated by reductions in the number of pods per plant, seeds per pod, and 100-seed weight. In cultivar Super, NaCl stress alone decreased these parameters by 18–22%. However, foliar application of Arg, NO and their synergistic combination considerably improved yield attributes. Under non-stressed conditions, NO treatment resulted in the highest increases in pod number (34%), seeds per pod (36%), and 100-seed weight (24%) in Super, while Arg + NO yielded a 26% improvement in seed weight. Under saline stress, combined applications were even more effective. Notably, Super plants treated with NaCl + NO exhibited the highest yield improvements: 67% more pods, 63% more seeds per pod, and 54% higher 100-seed weight, while the Arg + NO combination also enhanced yield by 45–56%. Similarly, in Sandal, salinity stress caused notable yield reductions, which were substantially mitigated by Arg, NO or their combination. NO treatment under salinity resulted in a 54% increase in pod number and a 51% increase in seed weight, while the Arg + NO combination improved seed weight by 55%. These findings underscore the role of Arg and NO, particularly their combined application, in enhancing the reproductive success of B. napus under salinity stress by counteracting yield losses and promoting pod and seed development (Fig. 8A–C).

Synergistic effect of nitric oxide and arginine on stress markers and yield attributes of B. napus grown in salt stress. (A) Number of pods per plant, (B) Number of seeds per pod and (C) Weight of hundred seeds. Graph bars presented mean of three replicates ± standard errors in error bars. Different alphabets above graph bars obtained after Duncan’s multiple range test presented mean values are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Pearson’s correlation and principal component analysis (PCA)

The Pearson correlation for the Super (upper triangle) and Sandal (lower triangle) cultivars shown in Fig. 9 revealed that the Na and Cl ions in the roots and their successive concentrations in the shoots were highly negatively correlated with growth and physiological and ultimately yield attributes. These findings suggested that NaCl stress resulted in elevated levels of Na and Cl ions in B. napus plants. These changes not only reduce growth but also hamper photosynthesis, ultimately resulting in lower yields. The PCA results for the Super and Sandal cultivars are shown in Fig. 10. Figure 10A,B show the percentages of all principal components (PCs) for Super and Sandal cultivars, respectively. PC1 and PC2 contributed the most to both Super (67.5 and 19.2%) and Sandal (66.7 and 19.9%) cultivars. The PCA biplot for both cultivars, shown in Fig. 10C,D, revealed that NaCl (100 mM) stress (5) is separated well from the other treatments (1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7 and 8). These findings confirmed that NaCl stress had significant effects on all the studied parameters. Furthermore, the PCA results for both cultivars revealed that stress markers (MDA, H2O2 and RMP) were positively correlated with Na and Cl ions in the roots and shoots of the plants. Additionally, these attributes were aligned with PC2. However, these attributes were negatively correlated with other attributes aligned with PC1. This included growth parameters, nutritional ions and physiological and yield attributes.

Pearson’s correlation for various attributes of B. napus cultivars (Super; upper triangle and Sandal; lower triangle) under the effects of nitric oxide and arginine along with salt stress. (Various abbreviations used are as follows; RL; Root length, SL; Shoot length, RFW; root fresh weight, RDW; root dry weight, SFW; shoot fresh weight, SDW; shoot dry weight, nL; number of leaves, CAT; catalase, POD; peroxidase, APX; ascorbate peroxidase, MDA; malondialdehyde, H2O2; hydrogen peroxide, RMP; relative membrane permeability, RWC; relative water content, Chl; chlorophyll, K; potassium, Ca; calcium, Na; sodium, Cl; chlorine, TSP; total soluble proteins).

Percentage of explained variables in principal component analysis, (A) Super, (B) Sandal and principal component analysis for various attributes of B. napus cultivars (C) Super, (D) Sandal under the effects of nitric oxide and arginine along with salt stress. (Various abbreviations used are same as given in Fig. 9. Numeric 1, 2, 3 up to 8 corresponds to treatments applied in this research such as 1 = control, 2 = 150 µM nitric oxide, 3 = 0.5 mM Arginine, 4 = 2 + 3, 5 = 100 mM NaCl, 6 = 2 + 5, 7 = 3 + 5, 8 = 4 + 5).

Discussion

Soil salinization is an escalating global problem, especially in arid and semi-arid regions where evapotranspiration surpasses precipitation, resulting in salt deposition in the rhizosphere. Low rainfall, unsustainable irrigation practices using saline water, and excessive or imbalanced fertilizer use accelerate this phenomenon45. Mechanistically, salinity stress initially triggers osmotic stress, which rapidly restricts water availability and decreases turgor pressure, thereby limiting cell expansion and early vegetative growth46. Prolonged exposure leads to ionic stress, primarily through toxic Na⁺ accumulation, and oxidative stress due to excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation47. In this study, salt stress impaired the growth of both B. napus cultivars by reducing shoot biomass, leaf area, and overall plant vigor. These effects can be mechanistically traced to osmotic restriction of water uptake and reduced cell expansion, as well as ion toxicity interfering with metabolic activities48.

Foliar supplementation with Arg and NO counteracted these effects by reprogramming stress response pathways that regulate osmotic adjustment, nutrient uptake, photosynthetic efficiency, and ROS detoxification. Consistent with this, Arg and NO supplementation improved growth of sunflower and canola under salinity in previous studies19,49. Arg, as a precursor for polyamines, proline, and NO, exerts a multifaceted role in stress defense. It enhances nitrogen assimilation and polyamine biosynthesis, which stabilize membranes and proteins under dehydration50,51. Conversion of Arg into proline and NO adds an additional layer of osmoprotection and signaling, respectively52. NO, in turn, modulates root elongation, nutrient uptake, and phytohormone cross-talk, while activating plasma membrane H⁺-ATPases and ion transporters to maintain ion balance53. By regulating stomatal aperture and promoting water-use efficiency, NO directly mitigates osmotic stress and sustains growth under saline conditions54.

Salinity strongly suppressed photosynthetic pigments in this study, reflecting oxidative degradation of chlorophyll molecules and impaired biosynthetic machinery55. Arg and NO restored pigment levels, suggesting a mechanistic involvement in both preventing ROS-mediated pigment loss and stimulating pigment biosynthesis. NO achieves this by scavenging ROS and protecting thylakoid membranes56while Arg contributes via polyamine-mediated stabilization of pigment–protein complexes52. Moreover, NO signaling integrates with phytohormones (auxin, cytokinin) to activate photosynthetic gene expression and repress chlorophyllase activity, sustaining photosynthetic capacity under stress53.

Membrane destabilization, evident from elevated MDA, H₂O₂, and relative membrane permeability (RMP), highlights oxidative lipid peroxidation as a key salinity-induced injury57,58. Arg and NO minimized these effects by bolstering antioxidant capacity and reinforcing membrane stability. NO directly interacts with antioxidant enzymes, reducing lipid peroxidation56while Arg-derived polyamines form electrostatic associations with membrane phospholipids, protecting bilayer integrity59.

Relative water content (RWC) declined under salinity, indicating impaired water acquisition. Arg and NO restored RWC, likely by enhancing root growth, activating aquaporins, and strengthening osmotic adjustment. Their combined effect may be attributed to Arg-driven NO biosynthesis, which amplifies NO-mediated signaling for water conservation60. Similarly, total soluble protein content declined under salt stress due to protein degradation and suppressed synthesis61,62. Arg enhanced protein stability through improved nitrogen metabolism and amino acid biosynthesis25NO supported protein synthesis by sustaining photosynthesis and energy availability63. Both also modulated expression of stress-related chaperones and folding enzymes, protecting functional proteins52.

ROS accumulation under salinity activated antioxidant enzymes (CAT, POD, APX), a typical defense response64,65. Arg and NO treatments further elevated their activities, mechanistically reflecting their ability to activate redox-sensitive transcription factors and gene expression programs for antioxidant enzymes66,67. Arg also supported antioxidant defense via polyamine and proline biosynthesis, while NO directly activated enzymatic and non-enzymatic ROS detoxification pathways30,65,68. This reinforced ROS homeostasis and prevented oxidative cellular damage. Phenolics and proline, which increased under salinity, functioned as secondary antioxidant and osmo-protectant metabolites69,70,71. Arg and NO application slightly reduced their accumulation, indicating that external alleviation of stress reduced the need for their overproduction72.

Salinity also disrupted ion balance, with excessive Na⁺ accumulation suppressing K⁺ and Ca²⁺ uptake, thereby impairing enzyme function and signaling73. Arg and NO supplementation reduced Na⁺ and enhanced K⁺ and Ca²⁺ accumulation, consistent with their role in activating ion transporters such as SOS1, NHX1, and HKT174. Arg indirectly supports these processes via NO and polyamines, maintaining ion homeostasis essential for cellular functioning under stress. These mechanistic improvements including restored photosynthesis, stabilized proteins, reduced oxidative injury, and balanced ion fluxes, cumulatively translated into improved yield components such as pod number, seeds per pod, and seed weight. Importantly, Arg serves as a biochemical precursor of NO, linking its supplementation to enhanced endogenous NO synthesis via NOS-like activity75. This Arg–NO interaction creates a synergistic signaling network regulating antioxidant defenses, polyamine metabolism, osmotic balance, and phytohormone crosstalk, thereby fine-tuning stress responses. Collectively, these mechanisms culminated in substantial improvements in growth and yield, highlighting Arg and NO supplementation as a promising and cost-effective strategy for enhancing salinity tolerance in B. napus. Field-scale validations under diverse agro-ecological conditions are necessary to assess scalability and long-term agricultural benefits.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that NaCl-induced salinity stress significantly impaired the growth, physiological integrity, and biochemical stability of two B. napus cultivars, Super and Sandal. Salt stress induced pronounced osmotic imbalance and ionic toxicity, leading to reduced water uptake, disrupted ion homeostasis, and severe membrane damage evidenced by elevated malondialdehyde (MDA) and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) contents. Exogenous foliar application of Arg and NO enhanced the antioxidative defense system by upregulating key antioxidant enzymes (CAT, POD, and APX), which effectively mitigated oxidative damage through ROS scavenging. These treatments improved the accumulation of secondary metabolites such as total phenolics and proline, contributing to osmo-protection and oxidative stress reduction. These supplements also enhanced nutrient assimilation, regulated ion homeostasis and water relation under salinity stress. Arg and NO supplementation maintained the integrity of photosynthetic machinery, stabilized total soluble protein contents, and reduced membrane lipid peroxidation, collectively leading to substantial improvements in growth performance and yield-related traits of both B. napus cultivars under salinity stress. These findings underscore the promising potential of foliar application of Arg and NO as an effective economical strategy to enhance salt tolerance in B. napus. Nevertheless, future field trials under varied agro-ecological conditions are imperative to validate the practical applicability and long-term benefits of this approach for sustainable crop production under salinity-affected environments.

Data availability

The data sets associated with present work are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Negrão, S., Schmöckel, S. M. & Tester, M. Evaluating physiological responses of plants to salinity stress. Ann. Bot. 119, 1–11 (2017).

Isayenkov, S. V. & Maathuis, F. J. M. Plant salinity stress: many unanswered questions remain. Front. Plant. Sci. 10, 80 (2019).

Ranjithkumar, A. Assessing the impact of agricultural land reduction on future global food security: challenges and sustainable solutions. Indian J. Nat. Sci. 15, 89066–89083 (2025).

Naorem, A. et al. Soil constraints in an arid Environment—Challenges, prospects, and implications. Agronomy 13, 220 (2023).

Yan, F. et al. Exogenous melatonin alleviates salt stress by improving leaf photosynthesis in rice seedlings. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 163, 367–375 (2021).

Shahid, S. A., Zaman, M. & Heng, L. Soil salinity: historical perspectives and a world overview of the problem. Guidel. Sal. Assess. Mitigation Adapt. Nuclear Relat. Tech. 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96190-3_2 (2018).

Polash, M. A. S., Sakil, M. A. & Hossain, M. A. Plants responses and their physiological and biochemical defense mechanisms against salinity: A review. Trop. Plant. Res. 6, 250–274 (2019).

Habib, S. H., Kausar, H. & Saud, H. M. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria enhance salinity stress tolerance in okra through ROS-scavenging enzymes. BioMed. Res. Int. 2016 (2016).

Ahmad, P. et al. Mitigation of sodium chloride toxicity in solanum lycopersicum l. By supplementation of jasmonic acid and nitric oxide. J. Plant. Interact. 13, 64–72 (2018).

Hussain, S., Khaliq, A., Tanveer, M., Matloob, A. & Hussain, H. A. Aspirin priming circumvents the salinity-induced effects on wheat emergence and seedling growth by regulating starch metabolism and antioxidant enzyme activities. Acta Physiol. Plant. 40, 1–12 (2018).

Dubey, R. S. Photosynthesis in plants under stressful conditions. Handbook of Photosynthesis, Third Edition https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315372136-34 (CRC Press, 2016).

Munns, R. et al. Energy costs of salt tolerance in crop plants. New Phytol. 225, 1072–1090 (2020).

Usman, S. et al. Melatonin and arginine combined supplementation alleviate salt stress through physiochemical adjustments and improved antioxidant enzymes activity in capsicum annuum L. Sci. Hortic. 321, 112270 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Silica nanoparticles promote the germination of salt-stressed pepper seeds and improve growth and yield of field pepper. Sci. Hortic. 337, 113570 (2024).

Shokri-Gharelo, R. & Noparvar, P. M. Molecular response of canola to salt stress: Insights on tolerance mechanisms. PeerJ 2018 e4822 (2018).

Dekamin, M., Barmaki, M., Kanooni, A. & Meshkini, S. R. M. Cradle to farm gate life cycle assessment of oilseed crops production in Iran. Eng. Agric. Environ. Food. 11, 178–185 (2018).

Din, J., Khan, S. U., Ali, I. & Gurmani, A. R. Physiological and agronomic response of Canola varieties to drought stress. J. Anim. Plant. Sci. 21, 78–82 (2011).

Markie, E., Khoddami, A., Liu, S. Y., Chen, S. & Tan, D. K. Y. The impact of heat stress on Canola (Brassica Napus L.) yield, oil, and fatty acid profile. Agronomy 15, 1511 (2025).

Farouk, S. & Arafa, S. A. Mitigation of salinity stress in Canola plants by sodium Nitroprusside application. Span. J. Agricultural Res. 16, 16 (2018).

Hamurcu, M. et al. Nitric oxide regulates watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) responses to drought stress. 3 Biotech. 10, 1–14 (2020).

Akladious, S. A. & Mohamed, H. I. Physiological role of exogenous nitric oxide in improving performance, yield and some biochemical aspects of sunflower plant under zinc stress. Acta Biol. Hung. 68, 101–114 (2017).

Bano, A. et al. Induction of salt tolerance in brassica Rapa by nitric oxide treatment. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 1462–1664 (2022).

Tahjib-Ul-Arif, M. et al. Exogenous nitric oxide promotes salinity tolerance in plants: A meta-analysis. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 957735 (2022).

Ahmad, P. et al. Nitric oxide mitigates salt stress by regulating levels of osmolytes and antioxidant enzymes in Chickpea. Front. Plant. Sci. 7, 347 (2016).

Chen, Q. et al. Arginine increases tolerance to nitrogen deficiency in Malus hupehensis via alterations in photosynthetic capacity and amino acids metabolism. Front. Plant. Sci. 12, 772086 (2022).

Pakkish, Z. Quality characteristics and antioxidant activity of the Mango (Mangifera indica) fruit under arginine treatment. J. Plant. 11, 63–74 (2021).

Shakhsi-Dastgahian, F., Valizadeh, J., Cheniany, M. & Einali, A. Exogenous arginine treatment additively enhances growth and tolerance of salicornia Europaea seedlings under salinity. Acta Bot. Croat. 81, 213–220 (2022).

Chen, D., Shao, Q., Yin, L., Younis, A. & Zheng, B. Polyamine function in plants: metabolism, regulation on development, and roles in abiotic stress responses. Front. Plant. Sci. 9, 1945 (2019).

Hussein, H. A. A., Alshammari, S. O., Kenawy, S. K. M., Elkady, F. M. & Badawy, A. A. Grain-Priming with L-Arginine improves the growth performance of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under drought stress. Plants 11, 1219 (2022).

Sun, Y. et al. L-Arginine alleviates the reduction in photosynthesis and antioxidant activity induced by drought stress in maize seedlings. Antioxidants 12, 482 (2023).

Badem, A. & Söylemez, S. Effects of nitric oxide and silicon application on growth and productivity of pepper under salinity stress. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 34, 102189 (2022).

Jung, H. et al. Ascorbate-mediated modulation of cadmium stress responses: reactive oxygen species and redox status in brassica Napus. Front. Plant. Sci. 11, 586547 (2020).

Yasir, T. A. et al. Exogenous sodium Nitroprusside mitigates salt stress in lentil (Lens culinaris medik.) by affecting the growth, yield, and biochemical properties. Molecules 26, 2576 (2021).

Arnon, D. I. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in beta vulgaris. Plant. Physiol. 24, 1–15 (1949).

Cakmak, I. & Horst, W. J. Effect of aluminium on lipid peroxidation, superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidase activities in root tips of soybean (Glycine max). Physiol. Plant. 83, 463–468 (1991).

Velikova, V., Yordanov, I. & Edreva, A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Sci. 151, 59–66 (2000).

Yang, G., Rhodes, D. & Joly, R. J. Effects of high temperature on membrane stability and chlorophyll fluorescence in glycinebetaine-deficient and glycinebetaine- containing maize lines. Aust J. Plant. Physiol. 23, 437–443 (1996).

Jones, M. M. & Turner, N. C. Osmotic adjustment in leaves of sorghum in response to water deficits. Plant. Physiol. 61, 122–126 (1978).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976).

Chance, B. & Maehly, A. C. Assay of Catalases and Peroxidases. {black Small Square} Methods Enzymol. 2 (1955).

Nakano, Y. & Asada, K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant. Cell. Physiol. 22, 867–880 (1981).

Julkunen-Tiitto, R. Phenolic constituents in the leaves of Northern willows: methods for the analysis of certain phenolics. J. Agric. Food Chem. 33, 213–217 (1985).

Bates, L. S., Waldren, R. P. & Teare, I. D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant. Soil. 39, 205–207 (1973).

Wolf, B. A comprehensive system of leaf analyses and its use for diagnosing crop nutrient status. Commun. Soil. Sci. Plant. Anal. 13, 1035–1059 (1982).

Singh, A. Soil salinity: A global threat to sustainable development. Soil. Use Manag. 38, 39–67 (2022).

Zafar, F., Noreen, Z., Shah, A. A. & Usman, S. Co-application of humic acid, potassium dihydrogen phosphate, and melatonin to ameliorate the effects of drought stress on barley (Hordeum vulgare L). J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr. 24, 618–634 (2024).

Balasubramaniam, T., Shen, G., Esmaeili, N. & Zhang, H. Plants’ response mechanisms to salinity stress. Plants 12, 2253 (2023).

Yu, B., Chao, D. Y. & Zhao, Y. How plants sense and respond to osmotic stress. J. Integr. Plant. Biol. 66, 394–423 (2024).

Ramadan, A. A., Abd Elhamid, E. M. & Sadak, M. Sh. Comparative study for the effect of arginine and sodium Nitroprusside on sunflower plants grown under salinity stress conditions. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 43, 1–12 (2019).

Wang, D. et al. Exogenous nitric oxide induces pathogenicity of alternaria alternata on Huangguan Pear fruit by regulating reactive oxygen species metabolism and cell wall modification. J. Fungi. 10, 801 (2024).

Badawy, A. A., Alshammari, W. K., Salem, N. F. G., Alshammari, W. S. & Hussein, H. A. Arginine and spermine ameliorate water deficit stress in Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) by enhancing growth and Physio-Biochemical processes. Antioxidants 14, 329 (2025).

Ragaey, M. M. et al. Role of signaling molecules sodium Nitroprusside and arginine in alleviating Salt-Induced oxidative stress in wheat. Plants 11, 1786 (2022).

Ahmad, B. et al. Adaptive responses of nitric oxide (NO) and its intricate dialogue with phytohormones during salinity stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 208, 108504 (2024).

Bhardwaj, S. et al. Nitric oxide: A ubiquitous signal molecule for enhancing plant tolerance to salinity stress and their molecular mechanisms. J. Plant. Growth Regul. 40, 2329–2341 (2021).

Li, X., Zhang, W., Niu, D. & Liu, X. Effects of abiotic stress on chlorophyll metabolism. Plant Sci. 342, 112030 (2024).

Mariyam, S. & Seth, C. S. Nitric oxide: a key player in reinforcement of photosynthetic efficiency under abiotic stress. In Nitric Oxide in Developing Plant Stress Resilience. 157–171. (Elsevier, 2023).

Liu, J., Zhang, W., Long, S. & Zhao, C. Maintenance of cell wall integrity under high salinity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 3260 (2021).

Valgimigli, L. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant protection. Biomolecules 13, 1291 (2023).

Amiri, H. & Banakar, M. H. Hemmati Hassan gavyar, P. Polyamines: new plant growth regulators promoting salt stress tolerance in plants. J. Plant. Growth Regul. 1–18 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-024-11447-z (2024).

Lau, S. E., Hamdan, M. F., Pua, T. L., Saidi, N. B. & Tan, B. C. Plant nitric oxide signaling under drought stress. Plants 10, 1–30 (2021).

Bahrololomi, S. M. J., Raeini Sarjaz, M. & Pirdashti, H. The effect of drought stress on the activity of antioxidant enzymes, malondialdehyde, soluble protein and leaf total nitrogen contents of soybean (Glycine max L). Environ. Stresses Crop Sci. 12, 17–28 (2019).

Mirrani, H. M. et al. Magnesium nanoparticles extirpate salt stress in carrots (Daucus Carota L.) through metabolomics regulations. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 207, 108383 (2024).

Sami, F., Siddiqui, H. & Hayat, S. Nitric Oxide-Mediated enhancement in photosynthetic efficiency, ion uptake and carbohydrate metabolism that boosts overall photosynthetic machinery in mustard plants. J. Plant. Growth Regul. 40, 1088–1110 (2021).

Hasanuzzaman, M. et al. Regulation of reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under salinity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 9326 (2021).

Hasanuzzaman, M. et al. Exogenous nitric oxide donor and arginine provide protection against short-term drought stress in wheat seedlings. Physiol. Mol. Biology Plants. 24, 993–1004 (2018).

Iqbal, N. et al. Nitric oxide and abscisic acid mediate heat stress tolerance through regulation of osmolytes and antioxidants to protect photosynthesis and growth in wheat plants. Antioxidants 11, 372 (2022).

Liu, S., Jing, G. & Zhu, S. Nitric oxide (NO) involved in antioxidant enzyme gene regulation to delay mitochondrial damage in Peach fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 192, 111993 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Physiological and transcriptome analysis of exogenous L-Arginine in the alleviation of High-Temperature stress in Gracilariopsis lemaneiformis. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 784586 (2021).

Kumar, K., Debnath, P., Singh, S. & Kumar, N. An overview of plant phenolics and their involvement in abiotic stress tolerance. Stresses 3, 570–585 (2023).

Hosseinifard, M. et al. Contribution of exogenous proline to abiotic stresses tolerance in plants: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 5186 (2022).

Khan, N. Exploring plant resilience through secondary metabolite profiling: advances in stress response and crop improvement. Plant. Cell. Environ. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.15473 (2025).

Youusef, S., Adawy, A., EXOGENOUS APPLICATION OF ARGININE ALLEVIATES & THE ADVERSE EFFECTS OF NaCl-SALT STRESS ON CALENDULA OFFICINALIS L. PLANTS. Sci. J. Flowers Ornam. Plants 10, 191–215 (2023).

Hussain, S. et al. Recent progress in Understanding salinity tolerance in plants: story of Na+/K + balance and beyond. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 160, 239–256 (2021).

Joshi, S., Nath, J., Singh, A. K., Pareek, A. & Joshi, R. Ion transporters and their regulatory signal transduction mechanisms for salinity tolerance in plants. Physiol. Plant. 174, e13702 (2022).

Meng, Y., Jing, H., Huang, J., Shen, R. & Zhu, X. The role of nitric oxide signaling in plant responses to cadmium stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 6167 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their deep appreciation to Ongoing Research Funding Program, (ORF-2025-952), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

Ongoing Research Funding Program, (ORF-2025-952), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MR; Experimentation and Methodology, ZN; Supervision and Validation, SU; Statistical analysis, AAS; Investigation, writing SU, FZ & SA; writing-original draft preparation, AAS & SS; Data curation and Formal analysis, EAM & KME; Resource acquisition and Conceptualization and HOE; writing-revised draft preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

We declare that the manuscript reporting studies do not involve any human participants, human data or human tissues. So, it is not applicable. Our experiment follows with the relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Riaz, M., Noreen, Z., Usman, S. et al. Nitric oxide and arginine mitigate salt stress through physio-biochemical modulations and ions regulation in Brassica napus L.. Sci Rep 15, 33204 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17887-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17887-1