Abstract

Perinatal mental health disorders (PMHD) remain underdiagnosed and undertreated in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Limited mental health literacy (MHL) among perinatal patients contributes significantly to poor help-seeking behavior and delayed interventions. Valid, culturally adapted measures are necessary to assess MHL in this population. This study aimed to translate and examine the Mental Health Literacy Scale’s (MHLS) content validity for Emirati perinatal patients. A cross-sectional validation study was conducted at a tertiary hospital in the UAE using the Mutaba’ah cohort. The study followed the World Health Organization and COSMIN translation and content validity guidelines. The Arabic version, named MHLS-Emirate (MHLS-E), was evaluated by 20 healthcare professionals (10 perinatal clinical experts, 10 mental health experts) and 10 Emirati perinatal patients. Ratings for relevance, clarity, and comprehensiveness were analyzed using the Content Validity Index (CVI) and Kappa statistics. Expert reviewers determined that the majority of the items in the adapted Arabic scale were relevant to the concept of mental health and suitable to Emirati perinatal patients. Initially, perinatal patients regarded the items as generally clear and understandable, however some of the content was less relevant to their personal experiences. The scale was revised in response to this feedback by culturally adapting items and adding a new attribute to myths related to mental disorders. Post-revision, all items were considered clear, relevant, and appropriate for the target population by both experts and patients following these modifications.The MHLS-E demonstrated excellent content validity following cultural and contextual adaptation. Incorporating expert and patient perspectives ensured the measure’s relevance and clarity for Emirati perinatal patients. Future psychometric testing is recommended to evaluate reliability and construct validity within this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Perinatal mental health disorders (PMHD) remain underdiagnosed and undertreated, particularly in countries with developing mental health systems like the United Arab Emirates (UAE)1,2. PMHD relates to ordinary women’s mental health problems during pregnancy and up to one year after childbirth and includes a wide variety of conditions, such as depression, anxiety, and somatic disorders3,4,5,6. Perinatal patients with mental disorders frequently encounter delayed diagnosis and treatment, resulting in severe and lasting effects on women’s general health, child health and development, partner relationships, and society as a whole7,8. Undoubtedly, the limited awareness of mental health among perinatal patients hinders their ability to receive adequate mental healthcare9,10.

Literature on mental health wellbeing has demonstrated that low mental health literacy (MHL) is a considerable cause of mental health service underutilization among mental health patients11. Jorm et al. defined MHL as the “knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders, which aid their recognition, management or prevention”12 (p.182). Later, the concept became “understanding how to obtain and maintain positive mental health; understanding mental disorders and their treatments; decreasing stigma related to mental disorders; and enhancing help-seeking efficacy”13. In 2021, the UAE has only five psychiatrists per 100,000 population1. The current workforce is inadequate to deliver services comparable to Western countries such as the US, which has 10.5 psychiatrists per 100,000 population. The health authority of Abu Dhabi, the largest Emirate in UAE, predicts that the demand for mental health services will rise by more than 100% by 2030 2. The mental health services, which are already overwhelmed, face additional strain due to low MHL14,15. This necessitates incorporating mental health awareness into individual and community care, including perinatal care, at both the practical and policy levels16.

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are standardized questionnaires that capture patient-reported health outcomes, such as symptoms, quality of life, and functional status17. Content validity is “the degree to which the content of a PROM is an adequate reflection of the construct to be measured”18. In addition, it is the initial stage in the validation process of a PROM19. The process of content validity evaluation addresses PROMs’ relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility to the construct, target audience, and context20. PROMs must also undergo validation and adaptation to guarantee cultural and language appropriateness. This process entails translating and adapting a PROM to suit the target audience and evaluating the measures’ psychometric properties21,22. According to O’Connor et al.23no PROMs have been assessed in all areas of MHL. Therefore, to address this MHL gap in measurement tools, O’Connor and Casey24 created the Mental Health Literacy Scale (MHLS). The scale has exhibited a significant quality of methodology and is recognized as one of the most reliable and validated masure for evaluating MHL25. Hence, it is imperative to validate and adapt the MHLS content before its utilization to ensure accurate outcomes, facilitate cross-cultural comparisons, and enhance the quality of healthcare interventions26. Instead of creating a screening measure for perinatal mental disorders, which is currently regarded as under-recognized3we focused on validating a mental health literacy (MHL) measure.Low MHL has been shown to hinder help-seeking, delay diagnosis, and impair the effectiveness of screening programmes10,24. Consequently, the early identification and treatment of perinatal mental disorders can be indirectly supported by the enhancement of MHL10,11. The MHLS-E has the potential to be used as a measure for evaluating baseline literacy, informing public awareness campaigns, and customizing educational interventions. Accordingly, this study aimed to translate and examine the MHLS’s content validity for Emirati perinatal patients. The study has two main objectives:

-

1.

Translate the English version of O’Conner and Casey’s (2015) MHLS into Arabic.

-

2.

Assess the translated masure’s content validity by asking a heterogeneous expert panel and Emirati perinatal patients about the MHLS items’ relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility.

Methods

Study design

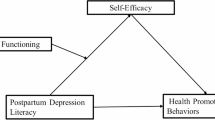

ÖThis cross-sectional validation study was conducted at a tertiary hospital in the UAE, utilizing data from the Mutaba’ah cohort27. The Mutaba’ah Mother and Child Health Study is a longitudinal birth cohort study led by researchers from the Institute of Public Health (IPH) at the United Arab Emirates University (UAEU). The study consists of two phases: translation and content validation, involving professionals and patients (Fig. 1). The version of the Mental Health Literacy Scale used in this study will be referred to as the Mental Health Literacy Scale-Emirate (MHLS-E).

The Arabic translation of the MHLS adhered to the World Health Organization’s and the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) translation guidelines28,29. The MHLS’s content validity was evaluated among healthcare professionals from May 1 to November 15, 2023, following COSMIN content validity guidelines20 and utilizing a heterogeneous expert panel method30. Subsequently, perinatal Emirati patients participated in content validation via individual cognitive debriefing interviews conducted from November 17 to December 1, 2023. Between December 15, 2023, and January 30, 2024, healthcare professionals and, subsequently, perinatal Emirati patients re-evaluated the content validity of the adapted MHLS-E. Additionally, we adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines to ensure accurate and comprehensive reporting of this cross-sectional study31.

Study population

The healthcare professionals comprised two expert panels divided into 10 Perinatal Clinical Experts (CEs) and 10 Mental Health Experts (MHEs). CEs offered cultural perspectives on maternal mental health in the UAE, while MHEs ensured a solid theoretical basis for mental health literacy (MHL). Using a purposive sampling method, the research team recruited currently practicing mental and perinatal health experts at clinics, hospitals, and academia in the UAE. In addition, 10 Emirati perinatal patients were recruited using a convenient sampling method during their maternity clinic visit to a private hospital in Alain City, UAE. Pregnant or less than one year postpartum aged 18 or older registered in the Mutaba’ah cohort who were eligible for the study were included.

Translation procedure

The Arabic translation of the MHLS involved several key steps: forward translation, synthesis, backward translation, committee review, cognitive interviews, content validation, and pilot testing. Two bilingual researchers independently translated the 35-item MHLS from English to Modern Written Arabic (MWA)32,33which is widely taught in the Arab world. The two translated versions were then collaboratively reviewed and combined into a single unified Arabic version. One translator was an expert in mental health literacy (MHL), while the other was inexperienced. A third bilingual researcher back-translated the Arabic version to English, remaining unfamiliar with the MHL construct and the MHLS. A committee of translators and mental health professionals reviewed this version to ensure the translation accurately conveyed the necessary themes and expressions. Minor discrepancies were resolved in group discussions. A translation report was written. Cognitive interviews with 10 Emirati prenatal patients further refined the translation and study materials, preparing a finalized version for content validation.

Content validation procedure

Participation in the expert panel was voluntary, with participants recruited during educational programs and workplace visits. They received a demographic survey link, information sheet, and consent form via email. After giving informed consent, participants evaluated 35 MHLS-E items individually to rate the scale’s relevancy, clarity, and comprehensiveness on a 4-point scale using a feedback survey26,34. After collecting all feedback, a summary was created. Participants then joined recorded online focus group discussions (FGDs), the first with MHEs in September 2023 and the second with CEs in November 2023. This approach aimed to mitigate expertise bias among professionals.

Emirati perinatal patients were recruited and provided with an information sheet, consent form, and demographic survey. In a private area of the maternity clinic, each patient evaluated the scale’s items using a 4-point scale on relevancy, clarity, and comprehensiveness. A visual guide assisted their rating decisions, while interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. The scale was adapted and re-evaluated based on insights gained from the initial evaluation by experts and patients. This process mirrored the original regarding recruitment, sampling, and data collection. The re-evaluation included ten professional experts and ten perinatal patients, each of whom reviewed the revised MHLS-E items for relevance, clarity, and comprehensiveness to ensure improved content validity.

Two researchers conducted narrative and thematic analyses of FGD and interview transcripts. Participants self-reported their gender and provided signed informed consent after receiving thorough information. The study adhered to ethical principles, including human dignity, confidentiality, justice, and beneficence, following applicable legal guidelines in the UAE35.

Data analysis

Responses were analyzed in a Microsoft Excel 365® spreadsheet. Incomplete surveys were sent to expert participants for input; incomplete ones were omitted from the final synthesis. The item-level Content Validity Index (I-CVI), scale average CVIs (S-CVI/Ave), and Kappa statistics were used to assess the ratings of MHLS-E items36. Items with I-CVI ≤ 0.78 were reviewed during FGDs34. Decisions to retain, eliminate, or modify items were based on expert survey results and panel discussions, with MHEs’ recommendations leading the final decisions.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted following the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The UAEU Social Sciences Ethics Committee approved this study (ERSC_2023_2749). Additionally, the Mutaba’ah study received ethical approval from the UAE University Human Research Ethics Committee (ERH-2017-5512) and the Abu Dhabi Health Research and Technology Ethics Committee (DOH/CVDC/2022/72).

Results

Demographic characteristics

Twenty healthcare professionals participated in the study (Table 1). Most were female, comprising 70% of the participants, while males comprised 30%. Regarding educational qualifications, 85% held postgraduate degrees, with the remaining 15% possessing Bachelor’s degrees. Furthermore, 55% of the healthcare professionals reported having more than 15 years of working experience.

For the Emirati perinatal patients included in the study (Table 2), 10 participants were all female, with a significant 80% holding Bachelor’s degrees. Among these patients, 80% were pregnant, while 20% were postpartum. Additionally, 90% were employed, and 80% belonged to a lower-middle economic status.

MHLS content validation results

The analysis of item ratings from healthcare professional groups (Table 3) showed that 32 out of 35 items (91%) were relevant to the construct, and 29 items (83%) were pertinent to Emirati perinatal patients. Most items were deemed relevant, except for three: item 4 (personality disorders), item 10 (risks and causes of mental disorders), and item 34 (voting for politicians with mental disorders). Six items were also not relevant to the population, including social phobia and agoraphobia. Kappa values indicated good agreement, except for items 4 and 34, which had fair agreement. The average scale content validity index (S-CVI/Ave) scored 0.95 for the mental health literacy construct and 0.91 for the Emirati perinatal population, reflecting excellent content validity. Clarity scores ranged from 0.7 to 1.0, with 74% of items considered very clear. Although the overall S-CVI/Ave was 0.87, below the ideal threshold of 0.8, it still surpassed the acceptable limit. The scale’s comprehensiveness received a perfect S-CVI of 1.0.

In contrast, all items evaluated by perinatal patients achieved an I-CVI score for clarity exceeding 0.8, resulting in an average scale clarity (S-CVI/Ave) of 0.98 (Table 4). The average score for scale comprehensiveness (S-CVI/Ave) was 0.80. Perinatal patients were assigned a rating of 1.00 for the scale’s relevance to the construct, with each item receiving a score of 1.00 on the I-CVI rating. However, the relevance of the scale CVI to the Emirati perinatal population was moderately low, yielding a score of 0.89. Of the 35 scale items, 22 (62.8%) had an I-CVI above 0.78, indicating that most items were relevant to the population’s needs. Nonetheless, 13 items related to specific mental disorders, causes and risks of mental disorders, self-treatment knowledge, cognitive behavioral therapy, and voting for politicians with mental health disorders were deemed less relevant. All Kappa values were above 0.60, indicating a good level of agreement.

Following modifications to the scale, a group of professionals, followed by patients, re-evaluated and documented strong and consistent results (Tables 3 and 4). Item-Level Content Validity Index (I-CVI) for item relevance to the construct and population was notably high among professionals and patients, with all items, including newly added ones, receiving a perfect score of 1.0. This is further reflected in the Scale-Level Content Validity Index (S-CVI) average, which also recorded a score of 1.0 for relevance to both construct and population across both groups (Tables 3 and 4). Interestingly, while the I-CVI for item clarity among professionals was 1.0 for most items, items 4, 5, and 6 received somewhat lower scores of 0.8 (Table 3). Nevertheless, the overall S-CVI average for item clarity among professionals remained high at 0.98, indicating a strong level of consensus. After the research team reviewed the scale, patients’ I-CVI for item clarity reached 1.0, while items 1, 6, and 7 scored 0.9, resulting in an overall S-CVI average of 0.99 (Table 4). At the time of re-evaluation, the Kappa value for all items exceeded 0.74, demonstrating robust inter-rater reliability among professional and patient evaluators.

MHLS scale modification

The MHLS underwent modifications for scale refinement to better resonate with Emirati perinatal patients (Table 5). This included adding three culturally relevant items classified under a new attribute, “Knowledge and Awareness of Myths Related to Mental Disorders,” based on cognitive debriefing interviews with patients. These new items will be reverse-scored to ensure higher scores reflect greater mental health literacy. Original items were revised to include references to pregnancy and childbirth, prompted by low S-CVI/Ave relevance ratings of 0.89. Several items were also changed from questions to statements, yielding a clarity rating (S-CVI/Ave) of 0.87 and an item-level content validity index (I-CVI) of 0.70 for items 29–35. The term “mental illness” was replaced with “mental disorder” as per DSM-5 guidance, and response options were standardized to a 5-point Likert scale for improved consistency and statistical analysis.

Discussion

The study culturally adapted the MHLS-E to be more appropriate for the Emirati perinatal population. It is important to emphasize that the study’s professional and patient groups were all related directly to the perinatal context: Emirati perinatal patients, perinatal clinical experts, and mental health professionals with perinatal expertise. This ensures that the MHLS-E has been tailored for and evaluated by the target population. Given the importance of validity in measure selection37the adapted MHLS-E would be highly appropriate for the UAE context, particularly for the perinatal population. The culturally adapted scale guarantees accurate assessments and enhances the usefulness and significance of the scale in dealing with mental health disorders within this population. The study results showed excellent content validity after the adaptation to suit the Emirati perinatal context. The primary findings indicated that both professional and patient groups rated item relevance to the construct higher than item relevance to the population. The patient group gave lower evaluations for scale comprehensiveness and population relevance than the professional group. However, the CE group assigned lower item scores than the MHE group for relevance and clarity assessments. Professional and patient groups evaluated MHLS-E item relevance to the construct higher than population relevance. It appears that the items properly reflected the mental health construct but were less customized to Emirati prenatal patients’ cultural and contextual needs. The findings emphasized ensuring that MHLS-E is culturally and contextually pertinent and conceptually accurate to facilitate effective patient engagement and comprehension. These findings necessitated the scale modification to reflect Emirati perinatal culture and experiences better and improve its validity and utility. The re-evaluation ratings show improvement in the CVI values after these adjustments.

The patient group’s ratings on the scale’s comprehensiveness were lower than the professional group’s, justifying the inclusion of three additional items derived from the transcribed patient interview responses. The newly introduced items addressed common myths and misconceptions in the Emirati perinatal population, such as the belief that magic and the evil eye are the causes of mental disorders and that religious healing is a form of treatment. These items were grouped under a newly created attribute titled “Knowledge and Awareness of Myths Related to Mental Disorders,” which aligns with an MHL construct attribute identified in the mental health literacy literature13. Furthermore, to address the patients’ group observed reduced scale relevance to the public, we contextualized questions by including terms referring to “pregnancy and postpartum” to increase engagement and establish personal connections. Linking the text to the reader’s personal experiences is the basis of this strategy, referred to as a text-to-self connection38. Many earlier MHLS validation studies did not thoroughly assess all content validation aspects, including construct relevance, population relevance, item clarity, and scale comprehensiveness30,39,40,41,42,43,44. Instead, they focused mainly on validating the content by assessing its comprehensibility to patients and its relevance to professionals. These studies did not clarify whether “relevance” refers to the construct, the population, or both. In addition, in these studies, comprehensibility was usually the primary focus when gathering patient input for content validity studies on the MHLS40,43,44. According to the COSMIN content validity guideline20patients must assess the relevance, comprehensibility, and comprehensiveness. At the beginning of this study, the feasibility of collecting relevant data and soliciting patient viewpoints on these complex topics was doubtful. However, with clear expectations and a well-defined approach, patients provided highly relevant and constructive comments, contributing significantly to the study.

The ratings by the two professional groups varied slightly, with a few items rating lower on relevance to the population in the CEs group. A study on content validity for primary healthcare workers in South Africa and Zambia showed similar findings where the CEs were unfamiliar with this method or lacked the necessary skills to evaluate the MHLS-E compared to MHEs30. Our study attributed the difference to CEs being frontline professionals who worked closely with the perinatal patient group. Although the CEs in this study were younger and less experienced than the recruited MHEs, we assume they deeply understand the population’s needs and culture. Despite early concerns that they may have less MHL, this group had a more prolonged recruitment procedure and a higher participation decline than MHEs. Therefore, it can be inferred that the perinatal-related professionals who agreed to participate in the CE group possessed enough confidence in their knowledge of mental health to be considered experts for this study.

While this study offers valuable insights into Mental Health Literacy, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. Initially, the study adhered to WHO translation guidelines; however, we modified and adopted the COSMIN checklist guidelines for assessing translation quality. Unfortunately, we could not perform the two backward translations recommended by COSMIN, as making such adjustments at that stage proved impractical. Consequently, the quality rating of our translation process fell from “Very Good” to “Adequate.” Nevertheless, it is essential to note that the translation process remains high quality despite this rating change. Another limitation involves the absence of a specific evaluation of subscale comprehensiveness within our assessment. Participants were directed to evaluate the entirety of the MHLS-E for key MHL concepts, with recommendations to include any missing concepts. Given that the scale was initially presented as unidimensional, comprising six attributes, one might argue that this unidimensional framework inherently addresses the comprehensiveness of the subscales.

The MHLS-E is intended to be a measure for healthcare researchers and policymakers to evaluate the mental health literacy levels of Emirati perinatal patients. The findings of this measure can be used to inform the development of culturally appropriate awareness campaigns, educational content for antenatal programs, and targeted training for healthcare providers. Furthermore, this study advocates for improved perinatal mental health education to enhance the understanding and attitudes of professionals toward women with mental health disorders. It recommends that nursing, midwifery, and medical educational institutions incorporate relevant modules into their curricula. Researchers are encouraged to employ the COSMIN Study Design checklist to ensure methodological rigor in Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. The adapted Mental Health Literacy Scale reveals low mental health literacy among perinatal patients, which may hinder help-seeking behavior and delay diagnoses. Furthermore, it assists clinicians in developing tailored educational interventions and gathering data to inform policymakers about the mental health needs of the Emirati perinatal population, ultimately leading to targeted awareness campaigns and culturally appropriate health programs. The study’s thorough content validation enhances the measure’s reliability in assessing mental health literacy among Arabic-speaking populations. Key strengths include adherence to COSMIN guidelines, systematic patient involvement in content validity assessment, and a re-evaluation phase to refine the MHLS-E. Further psychometric testing of the validated MHLS-E within the UAE’s perinatal context will be conducted. The future validation plan includes reliability, structural, convergent, and known-group validity.

In conclusion, this study aimed to translate and evaluate the content validity of the MHLS for perinatal Emirati patients in the UAE. A practical approach for culturally and contextually validating a measure involves incorporating the insights of both experts and patients. The MHLS-E demonstrates strong content validity in perinatal settings within the UAE. However, additional data is needed to assess the psychometric properties, including reliability, structural validity, and construct validity, of the MHLS-E among the perinatal population in the UAE context. There is a lack of comprehensive studies in the UAE that thoroughly explore all aspects of mental health literacy, particularly among perinatal individuals. Therefore, further research is necessary to address this gap.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization. Mental Health ATLAS 2020 1–136. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240036703 (2021).

Abdel Aziz, K. et al. Pattern of psychiatric in-patient admissions in Al Ain, United Arab Emirates. BJPsych Int. 18, 46–50 (2021).

McNab, S. E. et al. The silent burden: A landscape analysis of common perinatal mental disorders in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22, 342 (2022).

National Health Service England. Perinatal mental health. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health/perinatal/ (2019).

O’Hara, M. W. & Wisner, K. L. Perinatal mental illness: Definition, description and aetiology. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 28, 3–12 (2014).

Paschetta, E. et al. Perinatal psychiatric disorders: An overview. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 210, 501–509 (2014).

Milosavljević, M. & Vuković, O. Mental disorders in the peripartum period. Psihijatr Danas 52, 131–140 (2020).

Singla, D. R., Meltzer-Brody, S., Savel, K. & Silver, R. K. Scaling up patient-centered psychological treatments for perinatal depression in the wake of a global pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 12, 826019 (2021).

Ayres, A. et al. Engagement with perinatal mental health services: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 170 (2019).

Daehn, D., Rudolf, S., Pawils, S. & Renneberg, B. Perinatal mental health literacy: Knowledge, attitudes, and help-seeking among perinatal women and the public—a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22, 574 (2022).

Jorm, A. Mental health literacy: Empowering the community to take action for better mental health. Am. Psychol. 67, 231–243 (2012).

Jorm, A. et al. Mental health literacy: A survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med. J. Aust. 166, 182–186 (1997).

Kutcher, S., Wei, Y. & Coniglio, C. Mental health literacy: Past, present, and future. Can. J. Psychiatry 61, 154–158 (2016).

Andrade, G. et al. Attitudes towards mental health problems in a sample of united Arab emirates’ residents. Middle East. Curr. Psychiatry Ain Shams Univ. 29, 88 (2022).

Ganasen, K. A. et al. Mental health literacy: Focus on developing countries. Afr. J. Psychiatry 11, 23–28 (2008).

Suwalska, J. et al. Perinatal mental health during COVID-19 pandemic: An integrative review and implications for clinical practice. J. Clin. Med. 10, 2406 (2021).

Churruca, K. et al. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs): A review of generic and condition‐specific measures and a discussion of trends and issues. Health Expect. Int. J. Public Particip. Health Care Health Policy 24, 1015–1024 (2021).

Mokkink, L. B. et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 63, 737–745 (2010).

Patrick, D. L., Wild, D. J., Johnson, E. S., Wagner, T. H. & Martin, M. A. Cross-cultural validation of quality of life measures. In Quality of Life Assessment: International Perspectives (eds Orley, J. & Kuyken, W.) 19–32 (Springer, 1994). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-79123-9_2.

Terwee, C. et al. COSMIN methodology for assessing the content validity of PROMs User manual (2018).

Cazorla-Calderón, S., Romero-Sánchez, J. M., Fernández-García, E. & Paloma-Castro, O. Cross-Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the educational content validation instrument in health. Inq. J. Med. Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 59, 469580211060143 (2022).

Roberts, G. et al. Enhancing rigour in the validation of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs): Bridging linguistic and psychometric testing. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 10, 64 (2012).

O’Connor, M., Casey, L. & Clough, B. Measuring mental health literacy–a review of scale-based measures. J. Ment. Health Abingdon Engl. 23, 197–204 (2014).

O’Connor, M. & Casey, L. The mental health literacy scale (MHLS): A new scale-based measure of mental health literacy. Psychiatry Res. 229, 511–516 (2015).

Chaves, C. et al. Mental health literacy: A systematic review of the measurement instruments. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. Rev. INFAD Psicol. 3, 181–194 (2022).

Zamanzadeh, V. et al. Design and implementation content validity study: Development of an instrument for measuring Patient-Centered communication. J. Caring Sci. 4, 165–178 (2015).

Mutabaah. Mutabaah; Mother and Child Health Study. Mutabaah. https://mutabaah.uaeu.ac.ae/ (2022).

World Health Organisation. Process of translation and adaptation of instruments (2010).

Mokkink, L. B. et al. COSMIN study design checklist for Patient-reported outcome measurement instruments 1–32 (2019).

Korhonen, J., Axelin, A., Grobler, G. & Lahti, M. Content validation of mental health literacy scale (MHLS) for primary health care workers in South Africa and Zambia a heterogeneous expert panel method. Glob. Health Action 12, 1668215 (2019).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 12, 1495–1499 (2014).

Badawi, E. S. M., Carter, M. G. & Gully, A. Modern Written Arabic: A Comprehensive Grammar (Routledge, 2016).

Kamusella, T. The Arabic language: A Latin of modernity? J. Natl. Mem. Lang. Polit. 11, 117–145 (2017).

Yusoff, M. S. B. ABC of content validation and content validity index calculation. Educ. Med. J. 11, 49–54 (2019).

Department of Health. DOH Standard on Human Subject Research 1–82. https://doh.gov.ae/-/media/C07A10ADB6504312A601E3A514D43084.ashx (2020).

Cicchetti, D. V. & Sparrow, S. A. Developing criteria for establishing interrater reliability of specific items: applications to assessment of adaptive behavior. Am. J. Ment. Defic. 86, 127–137 (1981).

Messick, S. Test validity and the ethics of assessment. Am. Psychol. 35, 1012–1027 (1980).

The Ohio State University College of Education and Human Ecology. Making Connections - Beyond Weather & The Water Cycle. Beyond Weather & The Water Cycle - Just another Sites.EHE site. https://beyondweather.ehe.osu.edu/issue/we-change-earths-climate/making-connections (2011).

Akhtar, I. N. Mental health literacy scale: Translation and validation in Pakistani context. Pak. Soc. Sci. Rev. 4, 722–735 (2020).

Alshehri, E., Alosaimi, D., Rufaidi, E., Alsomali, N. & Tumala, R. Mental health literacy scale Arabic version: A validation study among Saudi university students. Front. Psychiatry 12, 741146 (2021).

BinDhim, N. F. et al. Validation and psychometric testing of the Arabic version of the mental health literacy scale among the Saudi Arabian general population. Int. J. Ment Health Syst. 17, 42 (2023).

Dang, H. M., Weiss, B., Trung, L. & Ho, H. Mental health literacy and intervention program adaptation in the internationalization of school psychology for Vietnam. Psychol. Sch. 55, 941–954 (2018).

Montagni, I. & González Caballero, J. L. Validation of the mental health literacy scale in French university students. Behav. Sci. 12, 259 (2022).

Sittironnarit, G., Sripen, R. & Phattharayuttawat, S. Psychometric properties of the Thai mental health literacy scale in sixth-year medical students. Siriraj Med. J. 74, 100–107 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all mental health and maternity clinical experts for contributing to this study, especially Dr. Matt O’Connor’s insightful feedback and support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: R.E., E.M., I.E. Data collection: R.E., R.B., M.A., L.A.A., R.H.A. Data analysis and interpretation: R.E., E.M., R.B., M.A., L.A.A., R.H.A., I.E. Drafting of the article: R.E. Critical revision of the article: R.E., E.M., R.B., M.A., L.A.A., R.H.A., I.E. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

ElKhalil, R., Masuadi, E., Bayoumi, R. et al. Content validity of the Mental Health Literacy Scale for perinatal use based on expert and patient input. Sci Rep 15, 32759 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17964-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17964-5