Abstract

To improve the image quality of active-matrix organic light-emitting diode (AMOLED) displays at low luminance levels, a novel power structure is proposed. Its effectiveness was validated by fabricating a 13-inch AMOLED panel with a tandem OLED and evaluating its optical performance. Compared to the conventional structure, the proposed structure reduced panel luminance deviation by 12% and color deviation by 41%, while also achieving a 41% reduction in hysteresis-induced color shift. As the temperature compensation capability was enhanced, luminance and color inconsistencies were minimized. By achieving these improvements, the proposed structure effectively addresses a key commercialization challenge for high-efficiency AMOLED technologies. While high-efficiency technologies enable high brightness and low power consumption, they also increase the sensitivity of luminance to small current deviations, making it more difficult to maintain image quality at low luminance. The proposed structure addresses this issue by applying individually optimized anode initialization voltages to each color subpixel, enabling more precise control of the OLED driving conditions and demonstrating substantial improvements in low-luminance image quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Active-matrix organic light-emitting diode (AMOLED) displays have gained widespread adoption owing to their remarkable characteristics, including high contrast, thinness, lightweight design, flexibility, and fast response times. Previously, the AMOLED technology was primarily applied to small mobile devices such as smartwatches and smartphones. Recently, their applications have expanded to medium-sized devices, such as tablets and notebooks1,2. This expansion is not merely scale in size; it is accompanied by the integration of advanced technologies such as tandem organic light-emitting diode (OLED) structures and color filters on encapsulation (COE), which enhance visibility, enable compact designs, and extend the lifespan of OLED device. These technological advancements contribute to higher display brightness and reduced power consumption by improving the external quantum efficiency (EQE)3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12.

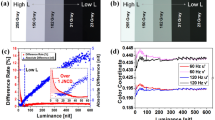

As the EQE increases, the same luminance can be achieved at a lower current. However, as shown in Fig. 1(a), this results in larger luminance variations in response to the same fluctuations in the driving current, thereby posing critical challenges for stable image quality, particularly at low luminance levels. This increased sensitivity of luminance to small current deviations can exacerbate pre-existing uniformity and stability issues at low luminance levels13,14,15,16,17,18. In addition, accurate control of low luminance becomes more challenging when high bit resolution and high color depth rendering are required19,20,21. Although this issue is less pronounced under bright ambient conditions, as shown in Fig. 1(b), it becomes more severe in dark environments, as illustrated in Fig. 1(c), where users typically lower the display brightness to reduce eye fatigue22,23,24,25,26. These challenges can act as a significant bottleneck to the commercialization of high-efficiency AMOLED technologies.

To address these challenges, we propose a novel method that utilizes the voltage for anode initialization (VAI). Anode initialization is a driving sequence that removes residual charges from the previous frame and resets the OLED anode voltage before charging it to the required level. VAI refers to the voltage applied to the anode during this initialization process. The sequence is performed during the non-emission period prior to each emission phase. This concept can be more intuitively understood with the driving sequence and simplified pixel circuit illustrated in Fig. S1. At low luminance levels, the small driving current causes the capacitance of OLED (COLED) charging process to have a greater influence on determining overall luminance. Therefore, VAI, the starting voltage of this charging process, plays a crucial role in achieving stable image quality at low luminance levels27,28. In light of the above, studies were conducted on compensation techniques to mitigate luminance fluctuations during variable refresh rate (VRR) operation and correct brightness variations caused by temperature changes29,30,31,32. Previous studies have primarily focused on feedback-based, reactive approaches, where the VAI level is adjusted via compensation algorithms in response to sensed variations in conditions such as refresh rate or temperature. In contrast, this study proposes a structure-based, proactive approach that redesigns the VAI power delivery architecture to enable more effective utilization of the VAI. By enabling more effective utilization of the VAI, the proposed structure establishes a foundation for ensuring more optimized initial conditions and minimizing image variation at low luminance levels. Furthermore, this structure offers the potential to enhance the compensation performance of existing dynamic compensation schemes under low luminance conditions. To support this explanation, a comparative summary is provided in Table S1.

Proposed structure

A key consideration in selecting the optimal VAI is ensuring a quality black level33. Even if the off-current of the driving thin-film transistor (TFT) is effectively controlled, charges accumulate on COLED during the emission period, leading to a gradual increase in the OLED voltage. If this voltage exceeds the OLED threshold voltage (Vth), unintended light emission occurs, rendering it impossible to maintain the black state. Hence, if the VAI is set too high, the OLED may turn on during the emission period, thereby preventing an accurate representation of the black state. Thus, an upper limit must be considered when selecting the appropriate VAI value.

The upper limit of VAI differs among the red, green, and blue subpixels owing to differences in OLED efficiency, emission wavelength, and Vth. Differences in efficiency and wavelength affect the emitting area and the layer thickness optimized for the microcavity effect, respectively34,35. This leads to differences in the COLED, affecting the rate of voltage increase under the same off-current conditions.

The difference in Vth between the OLEDs is attributed to the bandgap energy of the emissive material and color-specific charge-transport characteristics36,37,38. As the rate of voltage increase during the emission period and the Vth required for light emission are color-dependent, the upper limit of VAI also varies with color.

In the conventional single-VAI structure, as shown in Fig. 2(a), the VAI power is supplied through a power integrated circuit (IC) with a single VAI output, which is uniformly applied to all subpixels, as illustrated in Fig. 2(c). However, since the upper VAI limits differ among the red, green, and blue subpixels, this structure imposes a constraint: the VAI level must be set according to the color with the lowest upper limit, even though the other colors could achieve better performance at higher VAI levels. To overcome this limitation, we propose a multi-VAI structure that allows the application of color-specific optimal VAI values. As shown in Fig. 2(b), the proposed power structure enables the power IC to independently generate and supply VAI for the red, green, and blue subpixels. Within the panel, these voltages are delivered separately to each subpixel, allowing individual VAI to be applied to the anodes of each color subpixel. Through this structure, each color channel obtains its own voltage setting range based on its respective VAI upper limit, allowing for a wider voltage tuning window and enabling VAI optimization tailored to each color’s characteristics. As a result, the proposed scheme not only resolves the voltage range limitation inherent in the conventional structure, but also enables fine-tuned control over color-specific image quality characteristics. These structural and operational advantages are summarized in Table S2 and Fig. S2.

To enable independent generation of initialization voltages, as illustrated in Fig. S3 and Fig. S4, the single VAI block must be expanded to three, requiring the addition of sub-blocks such as digital-to-analog converters (DACs), amplifiers (amps), and digital registers. Each color VAI block is configured with an independent DAC and amplifier and is controlled via a separate digital register. Each DAC operates based on a stable reference voltage supplied by a low-dropout regulator (LDO), and its output is applied to the panel through the corresponding amplifier. Each amplifier block benefits from a reduced capacitive load, as the total COLED is distributed across the three VAI channels, allowing each amplifier to be designed more compactly than in the original single-VAI configuration. These components are relatively compact and simple compared to major power domains such as ELVDD/ELVSS and VGH/VGL, and thus the increase in component count has only a limited impact on IC area, design complexity, and implementation cost.

As shown in Fig. 2(b), the interconnection between the power IC and the panel, as well as the VAI lines within the panel, must be separated by color. In addition, as illustrated in Fig. 2(d), the subpixel structure must be routed to ensure that the anode initialization line for each color is accurately connected to the T4 TFT of the corresponding subpixel. While this increases the number of routing lines, the total COLED load to be initialized is distributed across the three VAI lines, allowing the width of each line to be reduced. This segmentation introduces some additional layout complexity, but the impact remains limited due to the line width reduction. Moreover, since no additional photomasks or fabrication steps are required, the increase in cost and the burden on the panel manufacturing process remain minimal.

As shown in the comparison between Fig. 2(c) and Fig. 2(d), the driving and compensation part, which includes the driving TFT and compensation circuitry, remains unchanged, while only the circuitry responsible for initializing the anode is modified. Applying the proposed multi-VAI structure requires modifying only this circuitry, allowing the driving and compensation part to remain intact. Consequently, this structure ensures broad compatibility, enabling seamless integration with various compensation pixel circuits without specific constraints.

In terms of power consumption, no significant increase is expected. In the single-VAI structure, a single VAI power source charges the total COLED of all subpixels, whereas in the multi-VAI structure, separate VAI power sources for each color charge only the COLED of their corresponding color subpixels. However, since the total capacitive load remains the same from the perspective of VAI, the overall energy consumption during initialization is essentially equivalent. Furthermore, the proposed structure offers broad applicability regardless of compensation pixel circuits or layer stack design, making it suitable for various AMOLED form factors that adopt an anode initialization sequence, including flexible and foldable displays.

Figure 2(e) shows the operation timing diagram. Because the T4 TFTs in the red, green, and blue subpixels of a pixel share the same gate line, Scan4, the VAI is simultaneously applied to the anodes of each subpixel, regardless of whether a single VAI source or multiple VAI sources are used. This timing can thus be identically applied to both the conventional single-VAI structure and the proposed multi-VAI structure. Anode initialization is performed during the emission (EM) off period, which refers to a non-emission interval when the T5 and T6 TFTs are turned off, thereby blocking current flow to the OLED. As the proposed structure was verified using low-temperature polycrystalline silicon and oxide (LTPO) pixels, the driving timing was comprised of refresh and skip frames to enable VRR operation39,40. During skip frames, anode initialization is carried out in the same manner as in refresh frames, as illustrated in the skip frame timing of Fig. 2(e), enabling consistent initialization across all VRR conditions and thereby ensuring stable black level maintenance.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed multi-VAI structure, simulations were conducted to analyze the effect of Vth variations in T1 and T3 TFTs on the performance of the pixel circuit. These simulations were performed using SmartSpice (Version 4.45.13.R, Silvaco Inc.)41.

The Vth variation range was set from − 1 V to + 1 V, and the simulation was performed with a reference white luminance of 0.5 nit. Figure 3(a) and Fig. 3(b) illustrate the luminance variations induced by the Vth shifts in T1 and T3, respectively, with Fig. 3(c) and Fig. 3(d) depicting the corresponding color variations. In these figures, ΔL represents the luminance variation, normalized to the reference luminance, and Δu′v′ denotes the color variation, expressed as the chromaticity distance in the International Commission on Illumination (CIE) 1976 u′v′ color space. The CIE 1976 u′v′ color space offers improved perceptual uniformity and is widely used for evaluating chromaticity shifts in emissive displays.

The simulation results show that the multi-VAI structure effectively reduces luminance variation when Vth shifts occur. Specifically, when Vth shifts by −1 V in T1 and T3, the luminance variation decreases from 53 to 40% and from 150 to 120%, respectively. These correspond to reductions of 25% and 20% compared to the single-VAI structure. In terms of color variations, the multi-VAI structure also shows significant improvement. When Vth shifts by + 1 V in T1, the color variation is reduced from 0.018 to 0.010. In T3, it is reduced from 0.128 to 0.048. These correspond to reductions of 47% and 62%, respectively, compared to the single-VAI structure. This is because, in the single-VAI structure, optimization is possible for only one of the colors: red, green, or blue, whereas the multi-VAI structure enables the VAIs to be individually optimized for each color. As a result, not only is the overall luminance variation reduced, but the color variation is also improved.

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed structure, the multi-VAI structure was applied to a 13-inch LTPO AMOLED panel with a tandem OLED, featuring a resolution of 2752 × 2064 and a pixel density of 264 pixels per inch (PPI). The OLEDs in this panel adopt a top-emission RGB two-stack tandem structure, as illustrated in Fig. S5 and Fig. S6, which also outline their fabrication process, and their spectral characteristics are summarized in Table S3.

The power IC used for panel verification supported only two independent VAI outputs, as available. Accordingly, independent VAIs were assigned to the red and green subpixels, while the blue subpixel shared the same VAI as green. Given that the upper limit of the VAI is highest for blue, and the difference between blue and green is smaller than that between blue and red, the blue subpixel was paired with green. Although this configuration imposed limitations on the independent optimization of the blue subpixel, separate VAIs were assigned to red and green—which contribute most significantly to white luminance—in order to enable meaningful evaluation of the proposed structure under the available conditions.

Results and discussion

Luminance and color uniformity

The uniformity of an in-plane image quality was evaluated using the fabricated panel. Under the white 0.5 nit condition, luminance and color coordinates were measured at 168 points arranged in a 14 × 12 array. In the single-VAI structure, the optimal voltage was determined based on the same VAI being applied to the red, green, and blue subpixels. In the multi-VAI structure, the optimal voltage was derived by independently applying different VAIs to the red and green/blue subpixels.

Figure 4(a) presents a comparison of the maximum color-difference values among the 168 measurement points relative to the panel center for each structure. The color difference, denoted as Δu′v′, was calculated based on the CIE 1976 u′v′ chromaticity space. The application of the multi-VAI structure reduced the maximum Δu′v′ from 0.047 to 0.028, corresponding to a 41% reduction compared to the single-VAI structure.

Figure 4(b) shows a histogram of the color differences at 168 measurement points. When the multi-VAI structure was applied, the mode decreased from 0.0125 to 0.0075 based on the bin center, while the standard deviation of Δu’v’ was reduced from 0.009 to 0.006. This indicates that the overall dispersion of the color coordinates decreased, leading to an improvement in the color uniformity. Figure 4(c) and 4(d) are heatmaps generated based on the Δu’v’ values calculated from the color coordinate measurements of the single-VAI and multi-VAI structures, respectively. Heatmap analysis also confirmed that the application of the multi-VAI structure led to an overall improvement in color difference levels. To validate this improvement statistically, a one-sided paired t-test was conducted on 168 measurement points, revealing that the multi-VAI condition exhibited better color uniformity than the single-VAI condition, with a p-value less than 10−25.

The luminance difference, denoted as ΔL, was calculated by normalizing the luminance variation at each position with respect to the luminance at the center of the panel. Figure 5(a) shows a graph comparing the largest luminance difference among the 168 measurement points relative to the panel center. The maximum luminance difference was reduced from 49 to 43% with the application of the multi-VAI structure, corresponding to a 12% reduction. Figure 5(b) presents a histogram of the luminance differences at the 168 measurement points. With the application of the multi-VAI structure, the mode decreased from 12.5 to 2.5% based on the bin center, while the standard deviation of the luminance difference was reduced from 12 to 11%. This indicates that the luminance difference across the panel has decreased, leading to improved luminance uniformity. Figure 5(c) and 5(d) show heatmaps generated based on the luminance differences calculated from the luminance measurements of the VAI structure. Heatmap analysis also confirmed that the application of the multi-VAI structure led to enhanced luminance uniformity. To support this result statistically, a one-sided paired t-test was conducted on 168 measurement points, confirming that the multi-VAI condition improved luminance uniformity over the single-VAI condition, with a p-value less than 10−45.

Initial frame luminance ratio

In AMOLED displays, the hysteresis of the driving TFT causes the previous frame’s image to influence the current frame42,43,44. In a still frame, there is no difference from the previous frame, allowing the target luminance to be stably achieved. However, when transitioning to the target luminance from a different luminance level, the variation in Vth due to the hysteresis of the driving TFT prevents accurate achievement of the target luminance. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in the first frame after an image transition. One method to quantitatively evaluate this effect is to measure the extent to which the luminance of the first frame, when transitioning from black to the target luminance, reaches the intended luminance level. The initial frame luminance ratio (IFLR) is defined as the post-transition luminance of the first frame normalized by the luminance of the corresponding static screen. This ratio serves as a quantitative metric for evaluating the extent to which the first frame reaches the target luminance.

To evaluate the low-luminance IFLR performance based on the VAI power structure, the luminance and color coordinates of white, red, green, and blue were measured for each structure in a still image and in the first frame after the transition from black to white. The measurements were conducted under a white luminance condition of 0.5 nit, and the IFLR was then calculated based on the results.

As shown in Fig. 6(a), the red, green, and blue IFLRs appeared at different levels, as evaluated across five panels. This led to changes in the relative color ratios, causing not only luminance variation but also color variation in white. Notably, the IFLRs of red and blue were consistently higher than those of green, resulting in a color shift toward a magenta tint in the first frame. From the perspective of the VAI power structure, the single-VAI structure allows optimization only under the constraint that the same VAI is applied to all colors. In contrast, the multi-VAI structure enables additional degrees of freedom by maintaining the optimized VAI for red while allowing separate control of the VAI for the other colors. In the present implementation, green and blue share the same VAI due to hardware limitations. Although green and blue share the same VAI due to hardware limitations, this partial separation enabled further refinement of the IFLRs for green and blue subpixels. By reducing the IFLR differences between colors, the color variation—quantified as the average Δu′v′—was improved from 0.028 under the single-VAI condition to 0.016 under the multi-VAI condition, corresponding to a relative reduction of approximately 41.2%. The standard deviations across the five panels were 0.0013 and 0.0014, respectively, and error bars indicating panel-to-panel variation have been included in Fig. 6(b).

Prior to statistical testing, the normality of the paired differences was confirmed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, with a p-value of 0.752. Based on this result, a one-sided paired t-test was conducted, yielding a p-value of 8.43 × 10⁻⁶. This confirms that the observed improvement in color variation was statistically significant.

Figure 6(c) presents the corresponding evaluation results in the CIE 1976 u′v′ chromaticity space, reflecting the data from five panels. Upon luminance transition, the color coordinates of the first frame tended to shift toward the lower-right region relative to the still image. Compared with the single-VAI configuration, the multi-VAI structure reduced the color shift and positioned the initial-frame coordinates more closely to those of the still image across all panels. These results demonstrate that the proposed structure effectively mitigates hysteresis-induced color deviation during luminance transitions and enhances the color accuracy of the initial frame.

Variation of luminance and color by temperature

For AMOLED displays, luminance fluctuations occur due to variations in the characteristics of both the OLED and TFT as temperature changes. In the OLED, as the temperature increases, the Vth shifts in the negative direction, resulting in increased luminance45,46. In the oxide TFT used as T3 in LTPO pixels, Vth shifts in the negative direction as the temperature increases, which further amplifies the increase in luminance47,48. To compensate for luminance fluctuations caused by temperature variations, a previous study30 employed a dynamic compensation method using VAI, in which temperature-optimized VAI values were applied. Through measurements conducted at 5 °C intervals from 0 °C to 50 °C, this approach was shown to effectively suppress luminance deviations within ± 1% across the entire temperature range. Based on previous findings, this study aimed to evaluate the dynamic compensation performance with respect to the VAI power structure. In particular, to enable a more effective comparison of compensation performance, the evaluation scope was expanded beyond the white luminance assessed in the previous study to include color coordinate variations of white and luminance variations of individual red, green, and blue pixels, allowing for a more detailed assessment of color compensation capability. Instead, the temperature conditions were simplified by selecting only two representative points—25 °C as the reference and 50 °C as the varied-temperature case.

The changes in luminance and color were analyzed by measuring them at room temperature (25 °C) and high temperature (50 °C). Figure 7(a) presents the results of luminance variations for white, red, green, and blue, as well as the color variations of white when the temperature increases from 25 °C to 50 °C. As the temperature increases, the luminance of red, green, and blue increases at different rates, resulting in a shift in the color coordinates of white.

Measured results of luminance and color variation at 50 °C: (a) without compensation, (b) compensation focused on minimizing luminance variation with single-VAI, (c) compensation focused on minimizing color variation with single-VAI, and (d) simultaneous compensation of luminance and color variations with multi-VAI.

For the single-VAI structure, in which the same VAI is applied to red, green, and blue for compensation, the optimal compensation point differs between the luminance and color-variation perspectives. Figure 7(b) shows the result of optimizing the VAI to minimize the luminance variation with respect to temperature changes. In this case, the luminance variation of white could be reduced to 0.1%; however, the color variation could not be compensated for. A closer examination of each color reveals that the luminance of red remained high due to insufficient compensation even after VAI adjustment, while green and blue were overcompensated, resulting in decreased luminance. Consequently, the color variation was not effectively compensated owing to the imbalance in luminance ratios among the colors. Figure 7(c) shows the result of optimizing the VAI to minimize color variations due to temperature changes. To achieve this, the luminance variation rates of red, green, and blue were adjusted to similar levels during the optimization process. Consequently, the color variation was reduced from 0.012 to 0.004; however, the luminance variation was reduced only by 18%. Thus, the single-VAI structure was unable to minimize luminance and color variations simultaneously.

Figure 7(d) shows the compensation results obtained for the multi-VAI structure. By minimizing the luminance variations of red, green, and blue individually, both the luminance and color variations were minimized simultaneously. This approach effectively addressed the imbalance between luminance and color variations that occurred under the single-VAI structure, demonstrating that the multi-VAI structure is an effective solution for simultaneously compensating for both luminance and color variations. And this result provides evidence that the multi-VAI structure can serve as a structural foundation for enhancing the performance of existing dynamic compensation methods by resolving the structural limitations that constrained them.

Conclusion

In this study, a novel multi-VAI power structure was proposed to enhance image quality at low luminance levels in AMOLED displays by utilizing anode initialization. The proposed configuration enables independent VAI adjustment for each color, overcoming the inherent limitations of conventional approaches where the VAI upper bound of a specific color restricts the optimal application for other OLEDs. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed structure, a 13-inch LTPO-based AMOLED panel with tandem OLEDs was fabricated. The available power IC supported only two independent VAI outputs, which inevitably imposed certain limitations on the optimization of the blue subpixel. Nevertheless, as summarized in Table 1, optical performance measurements confirmed that the proposed approach effectively mitigates variations caused by panel non-uniformity, TFT hysteresis, and temperature fluctuations, ensuring stable and high image quality at low luminance levels. Notably, both the color non-uniformity and the hysteresis-induced color deviation were reduced by about 41%, significantly improving the color accuracy. The results demonstrated that the independent VAI adjustment strategy successfully enhances visual consistency across different operating conditions. As AMOLED efficiency continues to improve, ensuring superior image quality at low luminance levels will become an increasingly critical challenge. The color-specific multi-VAI power structure proposed in this study not only addresses this issue but also offers high compatibility, making it applicable to various AMOLED-based products, including tablets, laptops, automotive displays, and emerging form factors. Considering these aspects, this technology is expected to serve as a core foundational technology for power architecture that enables the stable commercialization of high-efficiency AMOLED technologies.

Data availability

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The raw data used are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Verified Market Research. AMOLED display market size by display type (conventional, flexible, transparent), by material (polymer, glass, & glass substrate), by application (consumer electronics, retail), by geographic scope and forecast. (2024). https://www.verifiedmarketresearch.com/product/amoled-display-market/

OLED-info. Foldable OLEDs: introduction and market status. https://www.oled-info.com/foldable-oleds (accessed 20 Feb 2025).

Hung, W. Y. et al. The first tandem, all-exciplex-based WOLED. Sci. Rep. 4, 5161. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05161 (2014).

Dickson, G. The steady evolution of OLED displays. Inf. Disp. 39, 21–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/msid.1438 (2023).

Danyliv, I. et al. Derivatives of 2-pyridone exhibiting hot-exciton TADF for sky-blue and white OLEDs. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 5, 4174–4186. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaelm.3c00443 (2023).

Jouaiti, A. et al. True- to sky-blue emitters bearing the thiazolo[5,4-d]thiazole electron acceptor for single and tandem organic light-emitting diodes. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 5, 2781–2792. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaelm.3c00234 (2023).

Park, B. J., Kim, K. J. & Kim, T. Quantitative analysis of exciton dynamics: investigating the role of the efficiency-enhancement layer for blue fluorescent organic light-emitting diodes. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 6, 5190–5200. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaelm.4c00695 (2024).

Kandasamy, N., Keerthi, N. & Jeyasekaran, J. Mixed ligand copper(I) complexes as emitters enable higher OLED device performance for energy-harvesting applications. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 5, 4805–4815. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaelm.3c00604 (2023).

Shi, S., Luo, X., Zhu, W., Chu, S. C. & Wang, T. Rollable AMOLED displays: making larger displays more portable. Inf. Disp. 40, 14–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/msid.1478 (2024).

Chung, W. J. & Lee, J. Y. The role of the bulky blocking unit of the fluorescent emitter in efficient green hyper-fluorescent organic light-emitting diodes. J. Inf. Disp. 22, 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/15980316.2020.1846089 (2021).

Kim, K. et al. Highly efficient tandem organic light-emitting diodes using p-type metal halide copper iodide (CuI). J. Inf. Disp. 25, 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/15980316.2023.2272561 (2024).

Kang, S. W. et al. Green phosphorescent organic light-emitting diode exhibiting highest external quantum efficiency with ultra-thin undoped emission layer. Sci. Rep. 11, 8436. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86333-9 (2021).

Zhang, K., Zheng, Y., Dang, P. & Peng, G. The challenge of OLED display quality in low Gray scale. Proc. Int. Disp. Worksh. 26, 914–917. https://doi.org/10.36463/idw.2019.0914 (2019).

Ni, S. et al. The new method to solve low-gray Mura by optimizing oven structure. SID Symp. Dig. Tech. Pap. 54, 1459–1461. https://doi.org/10.1002/sdtp.16863 (2023).

Tang, J. et al. AMOLED display sandy Mura study and improvement. SID Symp. Dig. Tech. Pap. 54, 619–622. https://doi.org/10.1002/sdtp.16634 (2023).

Pang, H. et al. Investigation into OLED response time within pixel drive circuits. SID Symp. Dig. Tech. Pap. 55(S1), 1484–1486. https://doi.org/10.1002/sdtp.17403 (2024).

Wang, Y., Tan, Z., Wang, Y. & Qu, K. A novel over drive technique in OLED driver IC for mobile phone. SID Symp. Dig. Tech. Pap. 55, 1208–1211. https://doi.org/10.1002/sdtp.17323 (2024).

Zhao, X. et al. 62 – 3: The effect of OLED Device Capacitance on Low Gray Levels Motion Blur. SID Symposium Digest of Technical Papers, 55: 539–541. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1002/sdtp.17133

Lim, G. W., Kang, G. G., Ma, H., Jeong, M. & Kim, H. S. An area-efficient 10-bit source-driver IC with LSB-stacked LV-to-HV-amplify DAC for mobile OLED displays. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits. 58, 3164–3175. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSSC.2023.3289503 (2023).

Park, Y. et al. A 10-bit source-driver IC with charge-modulation DAC for enhanced frame-rate mobile OLED displays. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits. 59, 3511–3523. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSSC.2024.3442248 (2024).

Kim, J. S., Yoon, J. O. & Choi, B. D. A low-area and fully nonlinear 10-bit column driver with low-voltage DAC and switched-capacitor amplifier for active-matrix displays. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits. 56, 488–499. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSSC.2020.3024704 (2021).

Mantiuk, R., Rempel, A. G. & Heidrich, W. Display considerations for night and low-illumination viewing. In Proc. 6th Symp. Appl. Percept. Graph. Vis. (APGV), 53–58; (2009). https://doi.org/10.1145/1620993.1621005

Soneira, R. M. Watching displays at night. DisplayMate https://www.displaymate.com/Displays_At_Night_1.htm (accessed 20 Mar 2025).

Soneira, R. M. iPhone 14 Pro Max OLED display technology shoot-out. DisplayMate https://displaymate.com/iPhone_14Pro_ShootOut_1P.htm (accessed 20 Mar 2025).

Soneira, R. M. & Galaxy, S. 20 Ultra OLED display technology shoot-out. DisplayMate https://www.displaymate.com/Galaxy_S20_ShootOut_1U.htm#Super_Dimming_Mode (accessed 20 Mar 2025).

Oh, J., Yoo, H., Park, H. & Do, Y. R. Analysis of circadian properties and healthy levels of blue light from smartphones at night. Sci. Rep. 5, 11325. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11325 (2015).

Dawson, R. M. A. et al. The impact of the transient response of organic light emitting diodes on the design of active matrix OLED displays. IEDM Tech. Dig. 875–878. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.1998.746494 (1998).

Na, S. H. et al. Enhancement of picture quality on ultra-low brightness by optimizing the electrical potential required for OLED charging in the AMOLED displays. J. Inf. Disp. 22, 275–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/15980316.2021.1923581 (2021).

Kim, L. J. et al. Image quality enhancement in variable-refresh-rate AMOLED displays using a variable initial voltage compensation scheme. Sci. Rep. 12, ; (5977). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09892-5 (2022).

Kim, N. Y. et al. An active-matrix organic light-emitting diode display with consistent low-luminance levels regardless of temperature. IEEE Access. 12, 105346–105353. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3435442 (2024).

Kim, Y., Chung, K., Lim, J. & Kwon, O. K. A highly uniform luminance and low-flicker pixel circuit and its driving methods for variable frame rate AMOLED displays. IEEE Access. 11, 74301–74311. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3296787 (2023).

Sim, D. S. et al. Improvement of flicker phenomenon at low frequencies in AMOLED displays by applying compensation scheme of variable reset voltage. Sci. Rep. 15, 12181. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96847-1 (2025).

Park, Y. J., Jung, M. H., Park, S. H. & Kim, O. Voltage-programming-based pixel circuit to compensate for threshold voltage and mobility using natural capacitance of organic light-emitting diode. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 49, 03CD01. https://doi.org/10.1143/JJAP.49.03CD01 (2010).

Xiang, C., Koo, W., So, F., Sasabe, H. & Kido, J. A systematic study on efficiency enhancements in phosphorescent green, red and blue microcavity organic light emitting devices. Light Sci. Appl. 2, e74. https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2013.30 (2013).

Chakaroun, M. et al. Experimental and theoretical study of the optical properties optimization of an OLED in a microcavity. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 65, 4897–4904. https://doi.org/10.1109/TED.2018.2870070 (2018).

Satoh, C. et al. Bandgap engineering for ultralow-voltage operation of organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Opt. Mater. 11, 2300683. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202300683 (2023).

Chen, J. et al. Extremely low turn-on voltage and negligible efficiency roll-off in OLEDs by controlling the penetration of cathode magnesium atoms into electron transport layer. Adv. Funct. Mater. (early access). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202501863 (2025).

Wu, I. W. et al. Correlation of energy band alignment and turn-on voltage in organic light emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 013301. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3282682 (2010).

Kim, J. C. et al. A novel LTPO AMOLED pixel circuit and driving scheme for variable refresh rate. J. Inf. Disp. 24, 283–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/15980316.2023.2213848 (2023).

Kim, L. J. et al. Image quality enhancement in variable refresh rate LTPO-based AMOLED displays using a gate in panel voltage compensation scheme. J. Inf. Disp. 24, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/15980316.2024.2424187 (2024).

Silvaco Inc. SmartSpice Circuit Simulator. https://silvaco.com/spice-simulation/parallel-spice-simulator/ (accessed 21 Jun 2025).

Chung, H., Kim, D. & Kim, B. Hysteresis characteristics in low temperature poly-Si thin film transistors. J. Inf. Disp. 6, 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/15980316.2005.9651984 (2010).

Hwang, H. W. et al. Analysis of recoverable residual image characteristics of flexible organic light-emitting diode displays using polyimide substrates. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 40, 1108–1111. https://doi.org/10.1109/LED.2019.2914142 (2019).

Kim, B. K., Kim, O., Chung, H. J., Chang, J. W. & Ha, Y. M. Recoverable residual image induced by hysteresis of thin film transistors in active matrix organic light emitting diode displays. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 43, L482. https://doi.org/10.1143/JJAP.43.L482 (2004).

Park, J. & Kawakami, Y. Temperature-dependent dynamic behaviors of organic light-emitting diode. J. Disp. Technol. 2, 333–340. https://doi.org/10.1109/JDT.2006.885144 (2006).

Yang, L., Chen, W., Wei, B. & Zhang, J. Temperature and emitting area dependence of red organic light-emitting diode performance. Phys. Status Solidi A. 211, 1488–1492. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssa.201330437 (2014).

Billah, M. M., Rabbi, M. H., Park, C. & Jang, J. Highly sensitive temperature sensor using low-temperature polysilicon oxide thin-film transistors. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 42, 1864–1867. https://doi.org/10.1109/LED.2021.3121478 (2021).

Shin, K. Y., Tak, Y. J., Kim, W. G., Hong, S. & Kim, H. J. Improvement of electrical characteristics and stability of amorphous indium gallium zinc oxide thin film transistors using nitrocellulose passivation layer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 9, 13278–13285. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b00257 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by LG Display Co., Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D. J. Kim organized the data, drew figures, and wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript at all stages. The project was guided by H. J. Kim (corresponding author).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, D.J., Lee, I.S., Lee, H.K. et al. Advanced power structure for enhanced optical performance of AMOLED displays at low luminance levels. Sci Rep 15, 32319 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17973-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17973-4