Abstract

Periodontitis, a prevalent inflammatory disease, leads to the progressive destruction of periodontal tissues and poses significant systemic health risks. Despite its widespread impact, the molecular mechanisms driving periodontitis remain poorly understood. This study integrates advanced ensemble machine learning models and bioinformatics approaches to elucidate the genetic basis of periodontitis. Using transcriptomic data from the gene expression omnibus (GEO) repository (GSE10334), we identified 21 common genes from bagging and boosting models, underscoring their critical role in disease pathophysiology. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis revealed hub genes (HNRNPC, TSR1, PLRG1, GOPC) with central roles in key biological pathways. Functional enrichment highlighted their involvement in actin filament regulation, immune response modulation, and RNA processing. Furthermore, mutation and copy number alteration (CNA) analyses revealed significant genetic diversity in these hub genes, particularly in diploid samples, with a high prevalence of missense and splice variants. Together, these findings advance our understanding of the molecular landscape of periodontitis, paving the way for novel biomarker discovery and targeted therapeutic strategies potentially leading to improved diagnostic and treatment approaches in periodontal care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Periodontitis, a complex and multifactorial inflammatory disease, is a leading cause of tooth loss globally, affecting approximately 20–50% of the adult population1. The disease is characterized by the progressive destruction of periodontal tissues, including alveolar bone and connective tissue, and is driven by a dysregulated host immune response to microbial biofilms. It is strongly associated with several modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors, including poor oral hygiene, smoking, genetic predisposition, systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, and aging. Beyond its oral manifestations, periodontitis has been implicated in systemic conditions such as diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and adverse pregnancy outcomes, underscoring its public health significance2. Despite significant advancements, periodontitis diagnosis primarily relies on clinical and radiographic assessments, which detect disease at relatively advanced stages3,4. Current treatments often adopt a generalized approach without accounting for individual molecular variability, leading to variable therapeutic success. Therefore, there is a pressing need for molecular markers that can facilitate early diagnosis and support personalized therapeutic interventions. Statistically, the global prevalence of severe periodontitis is estimated to be around 11.2%, making it the sixth most common human disease5. Periodontitis also accounts for significant healthcare costs and impacts the quality of life, highlighting the urgency of understanding its molecular underpinnings. In addition, chronic periodontitis has been increasingly recognized as a potential risk factor for systemic inflammation, contributing to the pathogenesis of diseases beyond the oral cavity.

Despite its prevalence and far-reaching health implications, the molecular mechanisms underlying periodontitis remain incompletely understood, necessitating further research into its genetic and molecular basis. Traditional clinical and microbiological assessments are limited in their ability to capture the complexity of host–pathogen interactions and inter-individual variability. Therefore, data-driven approaches are essential to unravel the biological mechanisms at play. Recent advances in high-throughput genomic technologies and bioinformatics have enabled comprehensive analysis of gene expression changes associated with periodontitis. Transcriptomic studies have revealed differential expression of genes involved in immune modulation, inflammatory response, and tissue remodeling6. For instance, studies have implicated pathways such as NF-κB signaling, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, and leukocyte transendothelial migration in the progression of periodontal inflammation7. In parallel, Machine Learning (ML) approaches have emerged as powerful tools for mining complex biological data. But Ensemble Learning Model (ELM) such as bagging and boosting are particularly effective in enhancing predictive performance and mitigating overfitting in heterogeneous datasets8. This study aims to harness the power of ELM to identify disease-associated genes from a transcriptomic dataset of periodontitis. Unlike traditional statistical approaches, ELM models can automatically learn from data patterns and interactions among a large number of variables, making them ideal for handling high-dimensional genomic datasets. Ensemble methods such as bagging and boosting were selected for their robustness, ability to reduce model variance, and strong performance in high-dimensional data scenarios typical of gene expression datasets. Their combined use enhances model generalizability and improves confidence in gene selection. The primary objective of this study is to identify genetic markers significantly associated with periodontitis through an integrative bioinformatics and ELM framework.

In this study, we utilized publicly available transcriptomic data from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (accession number GSE10334) to identify significant genetic markers associated with periodontitis. By leveraging bagging and boosting ensemble learning models, we systematically identified genes that exhibit significant relevance to disease phenotypes. These ELM, known for their robustness and accuracy in handling complex datasets, provided insights into critical gene sets associated with the pathophysiology of periodontitis. Specifically, bagging (implemented using a Decision Tree-based Bagging Classifier) and boosting (employing a similar ensemble learning strategy) were applied to classify healthy and diseased gingival tissue samples.

A key aspect of our approach involved addressing the challenges of data imbalance inherent to clinical datasets. Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) was used to ensure balanced representation of classes, enhancing model performance and reliability. After model training and evaluation, feature importance analysis revealed a list of top genes associated with periodontitis. By comparing significant genes identified by both bagging and boosting models, we identified a subset of common genes that are likely to play pivotal roles in the disease mechanism.

Further, the identified genes were annotated using expression platform data (GPL570), followed by functional analysis to elucidate their biological roles. This included constructing protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks, gene ontology (GO) enrichment, and pathway analysis. Such integrative approaches provide insights into the molecular landscape of periodontitis, offering a foundation for potential biomarker development and therapeutic interventions.

We hypothesize that combining machine learning models with transcriptomic analysis can identify a robust set of genes that not only differentiate healthy from diseased tissue but also provide mechanistic insights into the disease process and also holds direct translational potential. These genes may serve as the foundation for developing rapid, chair-side diagnostic assays that could facilitate early detection and intervention. Moreover, profiling gene expression in patients could eventually support personalized therapeutic strategies, optimizing treatment efficacy based on individual molecular signatures.

Our findings contribute to the growing body of knowledge on periodontitis, providing a foundation for future functional studies and biomarker development. The use of advanced computational methods in conjunction with bioinformatics analysis underscores the potential of integrating machine learning into biomedical research for uncovering novel insights into complex diseases.

Methodology

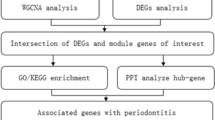

The overall method has been demonstrated in (Fig. 1).

The methodology process for the investigation is presented in a workflow. Gene expression data from the GSE10334 dataset was obtained from the GEO repository and preprocessed using various machine learning techniques. Ensemble machine learning models, including boosting and bagging approaches, were employed to classify the data and extract feature importance through cross-validation. Identified features were subjected to bioinformatics analyses such as PPI network construction, GO and pathway analysis, hub gene identification, and CNA analysis. This comprehensive pipeline offers insights into gene expression, biological pathways, and functional mechanisms.

Data acquisition and preprocessing

The dataset (GSE10334)9 was retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository, containing transcriptomic data of gingival tissue samples from periodontitis patients and healthy controls. This dataset was selected due to its relatively large sample size (247 samples), well-defined phenotypic groups (64 healthy and 183 diseased), and relevance to human periodontal tissue, making it highly suitable for supervised machine learning classification tasks. After removing duplicate entries, missing values were imputed using the mean of the column values:

where \(\:{X}_{ij}\) is the imputed value for sample \(\:i\) in gene \(\:j\).

To ensure consistent gene expression scales and eliminate bias from magnitude differences, normalization was performed using z-score transformation across each gene feature:

where \(\:{\mu\:}_{j}\) and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{j}\) are the mean and standard deviation of gene \(\:j\).

The dataset was transposed to align samples as rows and genes as columns for subsequent machine learning tasks.

Ensemble machine learning model development and analysis

Ensemble machine learning models (EMLM) were evaluated using stratified train-test splits (80:20 ratio) and cross-validation, with metrics including accuracy, ROC-AUC, and confusion matrix analysis. We employed ensemble machine learning models bagging and boosting which combine multiple weak learners to improve prediction accuracy and reduce overfitting. Feature importance rankings were extracted from each model to identify significant genes contributing to the classification. Two ensemble learning methods were employed:

Bagging classifier

The Bagging model combines multiple Decision Tree classifiers to reduce overfitting and variance. Each classifier is trained on a random subset of the training data with replacement (bootstrap sampling)10. Bagging was chosen for its stability and robustness in high-dimensional, noisy biological data.

Boosting model

Boosting iteratively trains classifiers on misclassified samples, assigning higher weights to difficult cases to minimize classification errors11. It was selected for its ability to improve prediction accuracy by focusing on the most informative and challenging samples.

Performance metrics

The models were evaluated using the following metrics:

Accuracy

The proportion of correctly classified samples among all samples. It provides an overall measure of the model’s correctness but may be less reliable in the presence of class imbalance. In this study, accuracy was computed as:

Precision

The proportion of true positive predictions out of all predicted positives. Precision reflects the model’s ability to avoid false positives and is particularly useful when the cost of false positives is high:

Recall (sensitivity)

The proportion of true positive predictions out of all predicted positives. Precision reflects the model’s ability to avoid false positives and is particularly useful when the cost of false positives is high:

F1 score

The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single score that balances the trade-off between them. It is especially useful when the dataset is imbalanced:

ROC-AUC score

The Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC-AUC) measures the model’s ability to distinguish between classes across all classification thresholds. It is computed as:

where TPR is the true positive rate, and FPR is the false positive rate.

Cross validation and analysis

Cross-validation is a statistical technique used to evaluate the performance of machine learning models by splitting the dataset into multiple subsets or folds12. The model is trained on a subset of the data (training set) and validated on the remaining fold (test set). This process is repeated several times, and the results are averaged to obtain a reliable performance estimate. In this study, 5-fold cross-validation was selected as a balance between computational efficiency and generalization performance. For both the Bagging and Boosting models, 5-fold cross-validation was implemented to validate their performance. The dataset was divided into five equal parts, and the models were trained and tested iteratively. This approach mitigated potential biases due to random splits and ensured that the models were evaluated comprehensively on different subsets of the data.

Identification of common genes

The top 200 genes ranked by feature importance from both bagging and boosting models were compared. The intersection of these sets provided the common genes of interest, annotated using the GPL570 platform. The GPL570 platform annotation file was used to map probe IDs to gene symbols and eliminate redundant entries.

PPI network construction and analysis

A PPI network represents the interactions between proteins within a biological system13,14. These interactions are crucial for understanding cellular functions, as proteins rarely act alone and often form complexes or signaling cascades to execute biological processes. In the network, nodes represent proteins, while edges represent interactions between them, which can include physical binding, co-expression, or functional associations. A minimum interaction score of 0.4 was selected (medium confidence) based on STRING guidelines to include biologically meaningful yet sufficiently broad interaction profiles. Only interactions supported by experimental evidence, curated databases, or co-expression data were considered. The resulting PPI network was visualized and analyzed using an open-source software for network analysis and visualization.

Functional enrichment analysis

The gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed using the ClueGO plugin tool of Cytoscape to explore the Biological Process (BP), Molecular Function (MF), and Cellular Component (CC) associated with the significant common genes. Three databases (KEGG, Reactome, and Wikipathways) were utilized to reveal the important pathways that associate with the genes using the same plugin tool ClueGo of Cytoscape15. Default settings were used for kappa statistics score (≥ 0.4) and two-sided hypergeometric test with Bonferroni step-down correction for significance (p < 0.05).

The mutation and copy number alteration (CNA) analysis of hub genes

The mutation and copy number alteration (CNA) analysis for HNRNPC, TSR1, PLRG1, GOPC were conducted using publicly available genomic datasets. Data was retrieved from cBioPortal and other large-scale genomics repositories such as TCGA, where applicable. Mutation types, including splice variants, missense variants, truncating variants, inframe variants, and structural variants, were categorized and visualized along with their CNA status. The copy number states were classified into five categories: Deep Deletion, Shallow Deletion, Diploid, Gain, and Amplification. The analysis was visualized to show the distribution of mutation counts across these categories, with the y-axis representing the mutation frequency and the x-axis depicting CNA categories. Each sample was color-coded based on its mutation type and CNA state. This integrative approach provided a comprehensive view of the genetic and structural alterations in the hub genes, highlighting its potential role in disease-related pathways16,17.

Result

Data acquisition and preprocessing

The microarray dataset GSE10334 has been considered for this study which consists of 247 samples. There were a total of 183 diseased and 64 healthy samples (Fig. 2). The dataset was prepared by addressing missing values through imputation and normalizing all features using z-score transformation to ensure uniform scaling. This preprocessing facilitated a consistent range of values, enhancing the models’ ability to learn meaningful patterns. Since the original dataset was imbalanced, with more samples in one class than the other, SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique) was employed to address this issue. SMOTE creates synthetic samples for the minority class, thereby balancing the dataset and preventing the models from being biased toward the majority class. Balancing the dataset resulted in an equal number of samples for both classes, ensuring unbiased model training. This step was crucial in improving the generalizability of the models for real-world scenarios, where data imbalance is a common challenge.

Machine learning model development and analysis

Bagging model

The Bagging model, which combines predictions from multiple Decision Trees, achieved impressive classification performance:

Confusion matrix

The confusion matrix for the Bagging model indicates that one healthy sample was misclassified as diseased, and two diseased samples were misclassified as healthy (Fig. 3A).

Performance evaluation of bagging model: confusion matrix and ROC curve with AUC = 0.98: (A) heatmap of the confusion matrix. The confusion matrices were computed using the confusion_matrix function from the sklearn.metrics module, based on the encoded test labels (y_test_encoded) and the model predictions (y_pred). The heatmaps were then plotted using the seaborn library’s heatmap function with annotation and a blue color scheme for clarity. Python (Version 3.10.12), Seaborn (Version 0.11.2), Matplotlib (Version 3.5.1), scikit-learn (Version 1.0.2) were used to generate the Heatmap. (B) ROC curve of the Bagging model.

Performance evaluation of boosting model: confusion matrix and ROC curve with AUC = 0.98: (A) Heatmap of the confusion matrix. The confusion matrices were computed using the confusion_matrix function from the sklearn.metrics module, based on the encoded test labels (y_test_encoded) and the model predictions (y_pred). The heatmaps were then plotted using the seaborn library’s heatmap function with annotation and a blue color scheme for clarity. Python (Version 3.10.12), Seaborn (Version 0.11.2), Matplotlib (Version 3.5.1), scikit-learn (Version 1.0.2) were used to generate the Heatmap. (B) ROC curve of the Boosting model.

ROC-AUC score

The model achieved an ROC-AUC score of 0.98, reflecting excellent discrimination between the classes. The near-perfect AUC suggests that the Bagging model effectively distinguishes between healthy and diseased samples across all thresholds (Fig. 3B).

Boosting model performance

Boosting, an ensemble method that builds strong learners iteratively, showed slightly superior performance compared to the Bagging model. The Boosting model achieved a higher accuracy than the Bagging model, indicating better overall performance.

Confusion matrix

The Boosting model misclassified only two samples, one healthy as diseased and one diseased as healthy highlighting its superior performance in comparison to the Bagging model (Fig. 4A).

ROC-AUC score

The Boosting model achieved a perfect ROC-AUC score of 1.00, indicating flawless separation of the two classes (Fig. 4B).

Cross validation and analysis

For both the Bagging and Boosting models, 5-fold cross-validation was implemented to validate their performance. The dataset was divided into five equal parts, and the models were trained and tested iteratively. This approach mitigated potential biases due to random splits and ensured that the models were evaluated comprehensively on different subsets of the data.

The Bagging model exhibited consistent performance across five cross-validation folds, with a mean accuracy of 91%: Cross-Validation Scores: [0.9189, 0.8904, 0.8904, 0.8630, 0.9726]. This result demonstrates the model’s reliability and robustness across different subsets of data. While the mean cross-validation accuracy of 92% across five folds confirms the Boosting model’s robustness: Cross-Validation Scores: [0.9324, 0.8904, 0.9452, 0.8630, 0.9863]. These results confirm that both models are robust and capable of generalizing effectively beyond the training data.

Common gene identification using EMLM

Feature importance analysis from the Bagging and Boosting models identified 200 significant genes each. An intersection method revealed 21 common genes (Fig. 5), underscoring their consistent contribution to classification. These genes could be potential biomarkers for periodontitis.

PPI network construction and analysis

The feature importance analysis using Bagging and Boosting models identified 200 significant genes from each approach, with 21 genes shared between the two methods, highlighting their consistent contribution to classification. These common genes were used to construct the PPI network through the STRING database. Where the minimum confidence score was 0.4. This network has 318 nodes and 344 edges (Fig. 6A). Afterward the CytoHubba plugin in Cytoscape utilized to identify hub genes within the PPI network (Table 1). Hub genes in a protein-protein interaction network are those with the highest number of connections (interactions), suggesting they play central regulatory roles. Their disruption is more likely to perturb biological pathways significantly, making them critical nodes in disease pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets. The analysis revealed key hub genes, including HNRNPC, TSR1, PLRG1, and GOPC, which exhibited important connections, underscoring their roles in pathways associated with periodontitis (Fig. 6B). HNRNPC has been implicated in RNA metabolism and splicing, processes critical for cellular stress responses and inflammation18. Similarly, PLRG1, a component of the spliceosome, is involved in RNA processing and has been linked to immune regulation and cell cycle control, both of which are dysregulated in periodontitis19,20. GOPC, a key player in vesicle trafficking, has been associated with Golgi apparatus integrity, which is essential for protein processing and immune signaling21. Lastly, TSR1, implicated in ribosomal biogenesis, may influence protein synthesis pathways that are disrupted during chronic inflammation22.

The figure illustrates two aspects of a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network: (A) PPI Network Visualization: A broad representation of the interactions between multiple proteins, highlighting key hub proteins such as HNRNPC and TSR1, which display dense connectivity within their respective clusters. (B) Subnetwork of hub proteins: Focuses on a smaller set of highly interconnected hub proteins, such as HNRNPC, TSR1, PLRG1 and GOPC, emphasizing their central roles. The color gradient represents varying levels of significance or connectivity, with red indicating the most influential hubs.

Functional enrichment analysis

The functional enrichment analysis performed using the ClueGO plugin in Cytoscape revealed critical insights into the biological significance of the dataset. Among the enriched biological processes, the negative regulation of actin filament depolymerization (23.85%) emerged as the most prominent, highlighting its role in maintaining cytoskeletal stability, alongside processes such as regulation of Golgi-to-plasma membrane CFTR protein transport (17.43%) and negative regulation of DNA biosynthetic processes (10.09%), which underscore mechanisms of protein trafficking and genomic stability. Cellular component analysis revealed a strong association with the classical complement pathway C3/C5 convertase complex (56%), indicating immune system involvement, while other components such as the GARP complex, pinosome, and PcG protein complex (each 8%) reflected roles in transcriptional regulation and intracellular trafficking. In molecular functions, glycolipid transfer activity (27.5%) was most enriched, implicating lipid metabolism, followed by snRNA binding (22.5%) and vitamin D3 25-hydroxylase activity (15%), which point to RNA processing and metabolic regulation (Table 2, Fig. 7). KEGG pathway analysis identified spliceosome and steroid biosynthesis pathways (each 50%), emphasizing the interplay between RNA splicing and hormonal biosynthesis, while Reactome pathways included defective C1GAL1C1 causing TNPS (27.78%), defective CYP27B1 causing VDDR1B (22.2%), and SUMOylation of RNA-binding proteins (22.2%), reflecting potential disease and regulatory mechanisms. Wikipathways analysis further linked the dataset to non-classical roles of vitamin D (33.33%), neural crest cell migration in cancer (33.33%), and genes associated with rheumatoid arthritis development (16.67%), indicating its relevance to both physiological and pathological contexts. Together, these results highlight the complex interplay of cytoskeletal regulation, immune modulation, metabolic pathways, and disease-associated mechanisms, offering a comprehensive foundation for further investigation23 (Table 3; Fig. 8).

The mutation and copy number alteration (CNA) analysis of hub genes

The mutation and CNA analysis revealed a diverse profile of genetic alterations in the hub genes including HNRNPC, TSR1, PLRG1, and GOPC underscoring its potential role as a key regulatory gene in disease processes. The majority of samples of each hub gene fell into the Diploid category, indicating no copy number changes; however, these samples exhibited the highest mutation diversity, with some reaching mutation counts almost 20,000 (Fig. 9). This suggests that mutations in diploid samples might play a predominant role in modulating in the hub genes function. Conversely, samples with Deep Deletion and Shallow Deletion exhibited relatively low mutation counts, likely reflecting reduced gene activity due to loss of copy numbers. Samples with Gain and Amplification demonstrated intermediate to high mutation counts, suggesting that increased gene dosage might exacerbate the mutational burden and contribute to dysregulation of the hub genes. Structural variants and specific mutations, such as missense and splice variants, were observed across all CNA categories but were predominantly enriched in diploid samples. These findings highlight the multifaceted genetic regulation of the hub genes and support its potential as a biomarker and therapeutic target in the context of disease.

Discussion

The present study leverages machine learning and integrative bioinformatics to uncover critical genetic contributors to periodontitis, shedding light on the molecular mechanisms underlying this complex disease. The identification of 21 common genes using ensemble machine learning models demonstrates the utility of computational tools in prioritizing disease-relevant genes from high-dimensional transcriptomic datasets. By combining bagging and boosting methods, we ensured robust gene selection, minimizing bias and maximizing the biological relevance of the findings.

The construction of the PPI network revealed four hub genes (HNRNPC, TSR1, PLRG1, and GOPC) with important roles in periodontitis. Although direct associations between HNRNPC, TSR1, PLRG1, and GOPC with periodontitis have not been firmly established, their known biological functions suggest potential relevance in the disease’s pathophysiology. HNRNPC is an RNA-binding protein involved in pre-mRNA splicing and transcript stability. It plays a critical role in regulating the expression of inflammatory cytokines and immune regulators. Dysregulation of HNRNPC can disrupt immune homeostasis, a hallmark of periodontitis. Modulating HNRNPC activity may allow for selective suppression of pro-inflammatory gene expression, potentially mitigating tissue destruction24. HNRNPC could be targeted to modulate inflammation-related gene expression via RNA-based therapies. TSR1 plays a crucial role in ribosome biogenesis and cellular protein synthesis; disruption in these processes can impair tissue regeneration and promote inflammatory responses in gingival tissues25. TSR1, through its role in ribosome biogenesis, might support gingival regeneration and tissue repair. PLRG1 (Pleiotropic Regulator 1), a component of the spliceosome complex, regulates alternative splicing events critical for immune signaling and epithelial cell maintenance, both of which are impacted during periodontal inflammation26. PLRG1 could serve as a novel target for splicing modulators aimed at controlling immune dysregulation. GOPC, known for its role in protein trafficking and autophagy, has been shown to modulate receptor recycling and degradation pathways, which could affect host-pathogen interactions and epithelial barrier integrity in periodontal tissues27. Autophagy-mediated regulation patterns contribute to alterations in the immune microenvironment in periodontitis, indicating the importance of autophagy-related proteins like GOPC in disease pathogenesis28. GOPC’s function in autophagy and receptor recycling may be leveraged to reinforce epithelial barrier integrity and microbial defense. These findings are consistent with prior research highlighting the roles of RNA regulation, immune signaling, and barrier function in periodontal disease, strengthening the connection between our findings and previously reported biological processes relevant to periodontal pathology. These genes, once validated in clinical cohorts, could be integrated into chairside diagnostic assays to stratify patients based on their molecular risk profiles. Moreover, targeted therapeutics such as antisense oligonucleotides, splicing modulators, or autophagy enhancers could be developed to modulate their activity in vivo. These interventions could complement existing mechanical therapies (e.g., scaling and root planning) by addressing the underlying molecular drivers of inflammation and tissue breakdown.

Functional enrichment analysis further contextualized these findings, revealing enrichment in pathways such as the regulation of actin filament depolymerization, immune system components like the classical complement pathway, and metabolic processes including glycolipid transfer activity. These pathways with the known pathophysiology of periodontitis, where cytoskeletal remodeling, immune dysregulation, and metabolic disturbances contribute to tissue destruction and disease progression29,30. Interestingly, enriched pathways such as steroid biosynthesis and vitamin D-related functions suggest potential links between periodontitis and systemic metabolic processes. There is some evidence to suggest that vitamin D might be associated with periodontal disease progression and tooth loss31,32,33. In addition, there is some more evidence suggesting that vitamin D might have more of an impact on the non-skeletal clinical parameters such as gingival bleeding34.

The mutation and CNA analysis of hub genes provided additional insights into their genetic regulation. Notably, the predominance of mutations in diploid samples highlights the role of mutational burden in modulating gene function, independent of copy number changes. The observed enrichment of missense and splice variants in these genes suggests their contribution to functional alterations in RNA splicing and protein synthesis, processes critical in inflammatory diseases35. Samples with copy number gains or amplifications showed increased mutation frequency, potentially exacerbating dysregulation, while those with deletions exhibited reduced mutation counts, indicating loss-of-function effects. This interplay between CNAs and mutations emphasizes the complexity of genetic regulation in periodontitis and highlights these hub genes as potential biomarkers.

Despite the strength of our findings, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the study relies on a single publicly available microarray dataset (GSE10334), which may limit the generalizability of the results. Factors such as sample heterogeneity, experimental variability, or batch effects could introduce bias in gene expression measurements and influence downstream analyses. Although ELM like bagging and boosting reduce overfitting and improve robustness, external validation using independent datasets or next-generation sequencing data is essential to confirm the reproducibility of the identified biomarkers. Furthermore, while machine learning excels at identifying statistical associations, it does not establish causal relationships, warranting experimental validation of the hub genes functional roles in periodontitis.

The implications of our findings are significant. The identified hub genes could serve as potential biomarkers for early diagnosis, disease stratification, or treatment monitoring in periodontitis. Their roles in key biological pathways such as immune modulation, RNA processing, and protein trafficking also present new avenues for therapeutic intervention. Moreover, their associations with systemic metabolic and inflammatory pathways support the growing view of periodontitis as a disease with systemic repercussions, reinforcing the importance of integrated, whole-body approaches in periodontal care.

While previous studies have applied machine learning algorithms such as Support Vector Machines36, Random Forests37, or basic neural networks to classify periodontitis samples or identify biomarkers, these efforts often relied on single-model predictions or limited gene panels. In contrast, our approach utilizes a dual ensemble strategy (bagging and boosting), which enhances robustness in gene selection. Furthermore, by integrating machine learning with protein-protein interaction networks and mutation/CNA analysis, our study provides a multi-dimensional characterization of hub genes, something not commonly addressed in earlier ML-based periodontal studies. This integrative framework represents a novel contribution to the molecular study of periodontitis.

Future research should prioritize the experimental validation of the identified hub genes and associated pathways in both in vitro and in vivo settings, including the use of murine periodontitis models and patient-derived samples. Validation in larger, independent cohorts using qPCR, proteomic, and functional assays will be essential to confirm their relevance and reproducibility.

Furthermore, incorporating multi-omics data such as proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics could offer a more comprehensive understanding of the molecular landscape of periodontitis and reveal novel layers of disease regulation. These integrative and translational approaches are critical for moving from computational discovery to clinically actionable insights. Ultimately, clinical trials evaluating the diagnostic and therapeutic potential of these biomarkers will be essential to realize the vision of precision periodontics and improve strategies for early diagnosis, individualized treatment, and disease prevention.

Conclusion

The superior performance of both models highlights the efficacy of ensemble methods in high-dimensional gene expression data. The slight edge of the Boosting model can be attributed to its iterative learning process, which minimizes error from previous iterations. The identified significant genes provide a robust foundation for further bioinformatics analyses, including pathway enrichment and protein-protein interaction network construction. These findings can lead to improved understanding and potential therapeutic strategies for periodontitis. To bridge the gap between computational findings and clinical impact, future studies should validate these biomarkers in patient cohorts and assess their utility in guiding prognosis or therapeutic response. Incorporating these insights into clinical workflows may support earlier diagnosis, risk stratification, and the development of targeted interventions.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. The complete code used for data processing and analysis is publicly available at: https://github.com/MTHasan0/periodontitis_microarray_analysis/tree/main.

References

Kassebaum, N. J. et al. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990–2010: a systematic review and meta-regression. J. Dent. Res. 93 (11), 1045–1053. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034514552491 (2014).

Nazir, M. A. Prevalence of periodontal disease, its association with systemic diseases and prevention. Int. J. Health Sci. (Qassim). 11 (2), 72–80 (2017).

Jacobs, R., Fontenele, R. C., Lahoud, P., Shujaat, S. & Bornstein, M. M. Radiographic diagnosis of periodontal diseases - Current evidence versus innovations. Periodontol. 2000 95 (1), 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12580 (2024).

Mallya, S. M., Tetradis, S. & Dwarakanath, C. D. Radiographic Aids in the Diagnosis. Newman and Carranza’s Clinical Periodontology: 4th South Asia Edition-E-Book. 313 (2024).

Tonetti, M. S., Greenwell, H. & Kornman, K. S. Staging and grading of periodontitis: framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J. Periodontol. 89 (Suppl 1), S159–S172. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.18-0006 (2018).

Jiang, N. et al. Comprehensive transcriptomic analysis of immune-related genes in diabetic foot ulcers: new insights into mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Int. Immunopharmacol. 139, 112638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2024.112638 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. Identification of key genes and pathways associated with oxidative stress in periodontitis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 9728172. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9728172 (2022).

Ammar Mohammed, R. & Kora A comprehensive review on ensemble deep learning: Opportunities and challenges. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Informat. Sci. 35 (2), 757–774 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2023.01.014 (2023).

Demmer, R. T. et al. Transcriptomes in healthy and diseased gingival tissues. J. Periodontol. 79 (11), 2112–2124. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2008.080139 (2008).

Alsakar, Y. M. et al. Multi-label dental disorder diagnosis based on MobileNetV2 and Swin transformer using bagging ensemble classifier. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 25193. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73297-9 (2024).

De Bin, R. & Stikbakke, V. G. A boosting first-hitting-time model for survival analysis in high-dimensional settings. Lifetime Data Anal. 29 (2), 420–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10985-022-09553-9 (2023).

Charilaou, P. & Battat, R. Machine learning models and over-fitting considerations. World J. Gastroenterol. 28 (5), 605–607. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v28.i5.605 (2022).

Liu, Y., Yu, J., Li, J., Li, W. & Ma, H. Bioinformatics-based analysis of potential therapeutic target genes for polycystic ovary syndrome. Cell. Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand). 70 (4), 169–175. https://doi.org/10.14715/cmb/2024.70.4.27 (2024).

Xiang, C. et al. Network Pharmacology and molecular Docking to elucidate the potential mechanism of ligusticum Chuanxiong against osteoarthritis. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 854215. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.854215 (2022).

Du, A., Xu, R., Yang, Q., Lu, Y. & Luo, X. Exploration of shared gene signatures and molecular mechanisms between type 2 diabetes and osteoporosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 28 (9), e18141. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.18141 (2024).

Steele, C. D. et al. Signatures of copy number alterations in human cancer. Nature 606 (7916), 984–991. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04738-6 (2022).

Hallermayr, A. et al. Somatic copy number alteration and fragmentation analysis in Circulating tumor DNA for cancer screening and treatment monitoring in colorectal cancer patients. J. Hematol. Oncol. 15 (1), 125. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-022-01342-z (2022).

Low, Y. H., Asi, Y., Foti, S. C. & Lashley, T. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins: implications in neurological diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 58 (2), 631–646. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-020-02137-4 (2021).

Kleinridders, A. et al. PLRG1 is an essential regulator of cell proliferation and apoptosis during vertebrate development and tissue homeostasis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29 (11), 3173–3185. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01807-08 (2009).

Ajuh, P., Sleeman, J., Chusainow, J. & Lamond, A. I. A direct interaction between the carboxyl-terminal region of CDC5L and the WD40 domain of PLRG1 is essential for pre-mRNA splicing. J. Biol. Chem. 276 (45), 42370–42381. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M105453200 (2001).

Koliwer, J., Park, M., Bauch, C., von Zastrow, M. & Kreienkamp, H. J. The golgi-associated PDZ domain protein PIST/GOPC stabilizes the β1-adrenergic receptor in intracellular compartments after internalization. J. Biol. Chem. 290 (10), 6120–6129. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.605725 (2015).

Turi, Z., Lacey, M., Mistrik, M. & Moudry, P. Impaired ribosome biogenesis: mechanisms and relevance to cancer and aging. Aging (Albany NY). 11 (8), 2512–2540. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.101922 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53 (D1), D672–D677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Mo, L. et al. An analysis of the role of HnRNP C dysregulation in cancers. Biomark. Res. 10 (1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40364-022-00366-4 (2022).

Thomson, E., Ferreira-Cerca, S. & Hurt, E. Eukaryotic ribosome biogenesis at a glance. J. Cell. Sci. 126 (Pt 21), 4815–4821. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.111948 (2013).

Zhang, X. et al. Autophagy-mediated regulation patterns contribute to the alterations of the immune microenvironment in periodontitis. Aging (Albany NY). 13 (1), 555–577. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.202165 (2020).

Papasaikas, P. & Valcárcel, J. The spliceosome: the ultimate RNA chaperone and sculptor. Trends Biochem. Sci. 41 (1), 33–45 (2016).

Kang, S., Dai, A., Wang, H. & Ding, P. H. Interaction between autophagy and Porphyromonas gingivalis-Induced inflammation. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 892610. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.892610 (2022).

Van Dyke, T. E. Inflammation and periodontal diseases: a reappraisal. J. Periodontol. 79 (8 Suppl), 1501–1502. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2008.080279 (2008).

Cekici, A., Kantarci, A., Hasturk, H. & Van Dyke, T. E. Inflammatory and immune pathways in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 64 (1), 57–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12002 (2014).

Botelho, J., Machado, V., Proença, L., Delgado, A. S. & Mendes, J. J. Vitamin D deficiency and oral health: A comprehensive review. Nutrients 12 (5), 1471. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12051471 (2020).

Alshouibi, E. N., Kaye, E. K., Cabral, H. J., Leone, C. W. & Garcia, R. I. Vitamin D and periodontal health in older men. J. Dent. Res. 92 (8), 689–693. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034513495239 (2013).

Jimenez, M., Giovannucci, E., Krall Kaye, E., Joshipura, K. J. & Dietrich, T. Predicted vitamin D status and incidence of tooth loss and periodontitis. Public. Health Nutr. 17 (4), 844–852. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980013000177 (2014).

Hiremath, V. P., Rao, C. B., Naik, V. & Prasad, K. V. Anti-inflammatory effect of vitamin D on gingivitis: a dose-response randomised control trial. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 11 (1), 61–69. https://doi.org/10.3290/j.ohpd.a29377 (2013).

You, N. et al. SpliceTransformer predicts tissue-specific splicing linked to human diseases. Nat. Commun. 15 (1), 9129. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53088-6 (2024).

Kausalya, R. & Ruth, J. A. Two Stage Machine Learning Framework to Identify Periodontitis and Dental Caries. 4th International Conference on Mobile Networks and Wireless Communications (ICMNWC) 1–6 https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMNWC63764.2024.10872001 (2024).

Feher, B. et al. Machine learning-assisted prediction of clinical responses to periodontal treatment. J. Periodontol. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.24-0737 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported via funding from Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University project number (PSAU/2025/R/1446).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author ContributionAll authors participated in concept, design and investigation of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hasan, M.T., Islam, M.R., Alqhtani, N.R. et al. Discovering periodontitis biomarkers and therapeutic targets through bioinformatics and ensemble learning analysis. Sci Rep 15, 34572 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18017-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18017-7