Abstract

Two-stage surgeries are increasingly used to minimize complications in adult spinal deformity (ASD) correction, yet the specific contributions of lateral lumbar interbody fusion (LLIF) and posterior column osteotomy/posterior spinal fusion (PCO/PSF) remain underexplored. This study evaluates their roles in deformity correction and establishes predictive thresholds for optimizing surgical planning. A total of 151 ASD patients (mean age 69.5 years) underwent staged LLIF and PCO/PSF surgeries one week apart. Radiographic parameters were analyzed preoperatively (Pre-), post- 1st LLIF (M-), post- 2nd PCO/PSF (Post-), and at two-year follow-up (F-). Correction rates were 80.9% for PI-LL mismatch (35.5% LLIF, 64.5% PCO/PSF), 40.5% for pelvic tilt (39.4% LLIF, 60.6% PCO/PSF), and 69.1% for C7 SVA (45.7% LLIF, 54.3% PCO/PSF). Coronal correction of the Cobb angle reached 76.7% (33.1% LLIF, 66.9% PCO/PSF). Significant ODI and SRS-22 score improvements were noted at two years. Predictive thresholds for imbalance were M-SVA 75.3 mm, M-PI-LL 32.5°, and M-PT 35.5°. The 2nd PCO/PSF contributes more to correction, and predictive thresholds aid surgical planning, reducing postoperative imbalance for better outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adult spinal deformity (ASD) encompasses a wide spectrum of spinal malalignment patterns, ranging from simple biplanar and segmental deformities to complex three-dimensional global deformities characterized by significant disruptions in coronal and sagittal alignment1,2. Surgical management for ASD offers both superior radiographic and HRQOL outcomes compared with nonoperative care3,4,5. However, these procedures are often complex and may be associated with high rates of perioperative complications6,7,8,9.

Although a two-stage surgical strategy has been proposed to reduce complications in adult spinal deformity (ASD) surgeries10,11,12planning for the second-stage procedure is traditionally based on the preoperative parameters established before the first surgery. Most related studies also use these initial preoperative parameters as the basis for research13,14. However, due to varying degrees of improvement after the first surgery, the original plan for the second procedure may need modification. Based on previous research findings15we hypothesize that the contribution of the first lateral lumbar interbody fusion (LLIF) procedure is limited. Therefore, the preoperative imaging parameters obtained before the second stage surgery hold greater clinical significance in guiding surgical decision-making. This study aims to identify the critical threshold values of these parameters to serve as a reference for clinical surgical planning.

Materials and methods

Study population

Consecutive patients who underwent a week interval of two-stage corrective spinal fusion surgery for ASD at our institution over a 6-year interval between March 2017 and December 2023 were included in this study. ASD was defined as the presence of at least one of the following indicators: adult degenerative(de novo scoliosis) or degenerative kyphosis (degenerative kyphosis with scoliosis of a less than 10 degree Cobb angle) or adult idiopathic scoliosis (continuation of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis) or iatrogenic spinal deformity without instrumentation but with spinal curvature greater than 20 degrees in the coronal plane, C7 sagittal vertical axis greater than 50 mm, pelvic tilt greater than 25 degrees, and/or thoracic kyphosis greater than 60 degrees.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age over 40 years, (2) availability of a complete set of preoperative full-length standing radiographs, and (3) number of fused vertebrae totaling five or more segments. Standardized data collection forms were used to collect patient demographic variables, including age, sex, gender, body mass index (BMI) and etiology.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with neuromuscular disorders diagnosed preoperatively or postoperatively; (2) a history of infection or tumors affecting the pelvis or spine; (3) patients in whom distal fixation was not achieved using S2 alar-iliac (S2AI) screws for pelvic stabilization; and (4) incomplete imaging or clinical assessment data till the 2 years follow-up periods.

Surgical procedure

All patients underwent staged spinal corrective fusion surgeries spaced one week apart (Fig. 1). The first stage (1st ) involved a lateral position and multilevel lateral lumbar interbody fusion (LLIF) via an anterior approach from L2/3 to L5/S1. The second stage (2nd ) was performed in the prone position and consisted of multilevel posterior column osteotomy (PCO) and posterior spinal fusion (PSF) surgery with a pedicle screw-based system from the upper or lower thoracic spine to the pelvis. Spinal osteotomies were classified according to the Schwab spinal osteotomy classification as follows: grade 2: multiple Ponte osteotomies16. Except for the uppermost three instrumented levels, osteotomies are performed at each vertebral level. The perioperative surgical data collected included estimated blood loss (EBL), operative time (OPT), surgical approach, number of instrumented vertebrae, and levels of LLIF.

Schema describing the correction in the two-stage surgery in ASD. (a) preoperative to the 1st stage LLIF surgery (Pre); (b) postoperative following the 1st stage LLIF surgery (M); (c) postoperative following the 2nd stage PCO/PSF surgery (Post); LLIF lateral lumbar interbody fusion, PCO posterior column osteotomy, PSF posterior spinal fusion.

Radiographic measurements

All radiographic measurements were performed using a picture archiving and communications system (PACS) workstation. The following parameters were measured on full-length standing radiography (Fig. 2). (1) sagittal parameters: thoracic kyphosis (TK), lumbar lordosis (LL), pelvic tilt (PT), sacral slope (SS), pelvic incidence (PI), T1 pelvic angle (TPA), PI minus LL mismatch (PI-LL), C7 sagittal vertical axis (C7 SVA); (2) coronal parameters:

Illustration of measurements of spinal and pelvic parameters in sagittal and coronal radiograph, including TK: thoracic kyphosis; LL: lumbar lordosis; TPA: T1 pelvic angle; PI: pelvic incidence; PT: pelvic tilt; SS: sacral slope; C7 SVA: C7 sagittal vertical axis; TCC: total coronal Cobb angle; UCC: upper coronal Cobb angle; LCC: lower coronal Cobb angle; C7PL-CSVL: C7 coronal plumb line to central sacral vertical axis; AVT: apical vertebra translation.

-

UCC (Cobb angle of upper coronal curve): the Cobb angle of scoliotic curve over thoracolumbar junction or upper lumbar area.

-

LCC (Cobb angle of lower coronal curve): the Cobb angle of scoliotic curve over lumbosacral junction or lower lumbar area.

-

TCC (Cobb angle of total coronal curve): the Cobb angle of scoliotic curve from thoracolumbar junction (T12/L1) to L5 or sacrum.

C7 coronal plumb line to the central sacral vertical axis (C7PL-CSVL), and apical vertebra translation (AVT).

The measurement time points for all imaging parameters were as follows: preoperative to the 1st LLIF surgery (Pre-), postoperative following the 1st LLIF surgery (M-), postoperative following the 2nd PCO/PSF surgery (Post-), and the two-year postoperative follow-up (F-). Standardized radiographic parameter collection forms were used to record patient values at each preoperative, postoperative, and follow-up time point.

All collected data were utilized to calculate the total correction rate after the operation, as well as the contributions of each 1st LLIF and 2nd PCO/PSF surgery. The total correction rate refers to the proportion of overall correction achieved compared to the initial deformity on standing upright radiographs. The contribution of 1st LLIF or 2nd PCO/PSF surgery was defined as the proportion of correction achieved by either intervention. These values were calculated using the following formula:

Clinical assessments

Quality of life was assessed during the preoperative assessment (Pre) and the two-year postoperative follow-up visit (F) using the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) score and Scoliosis Research Society-22 (SRS-22) questionnaire. Standardized questionnaire forms were used to record patient values at each preoperative and final follow-up time point.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as case numbers and percentages, and intergroup differences were assessed using the chi-square test. Continuous variables following a normal distribution are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Paired-sample t-tests were used to compare differences within groups for preoperative and postoperative parameters as well as postoperative and final follow-up radiographic parameters. Independent-sample t-tests were used to compare the differences between the sagittal C7SVA, PI-LL, PT, and coronal C7PL-CSVL parameters in the postoperative balanced and imbalanced correction groups.

Radiographic parameters showing statistically significant differences were further analyzed using binary logistic regression to identify risk factors for incomplete correction, both preoperatively and after the 1st stage LLIF. Critical thresholds were determined using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. A p-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and forest plots and ROC curves were generated using GraphPad Prism version 10.

Results

Demographics, operative parameters, and etiologies

138 patients were excluded for the following reasons (Fig. 3.): distal fixation was not achieved using S2AI screws for pelvic stabilization (50 patients), incomplete radiographic data (43 patients), neuromuscular disease (30 patients), spinal infection or tumor (15 patients). Finally, 151 patients were included in the final analysis. Among the patients (Table 1), 134 were female (88.7%), with a mean age of 69.5 ± 8.3 years. The mean BMI was 22.9 ± 3.9 kg/m². The preoperative T-score averaged − 1.5 ± 1.1. The etiologies of spinal deformities were as follows: adult degenerative scoliosis in 129 cases, adult degenerative kyphosis in 18 cases, adult idiopathic scoliosis in 2 cases, and iatrogenic spinal deformity in 2 cases.

In 2nd stage, the mean operative time had a mean of 313.5 ± 56.6 min. The estimated blood loss averaged 823.1 ± 493.3 mL The mean number of segments treated was 9.8 ± 2.1.

Radiographic outcomes

Sagittal plane parameters

Preoperatively, the average PI-LL mismatch (Table 2) was 39.3 ± 18°, which significantly decreased to 28.0 ± 17.6° after the 1st LLIF and further improved to 7.5 ± 12.2° after the 2nd PCO/PSF. Similarly, the average PT was 35.1 ± 10.7° preoperatively, significantly decreasing to 29.5 ± 10.2°and further to 20.9 ± 9.4°.

Significant improvements were also observed in C7 SVA, LL, TK, SS, and TPA throughout the two-stage surgical procedure. A significant loss of correction was observed in all sagittal imaging parameters at the two-year follow-up compared to the immediate postoperative values.

Coronal plane parameters

For the coronal plane, the average TCC was 18.9 ± 12.5° at the initial assessment, significantly decreasing to 14.1 ± 10.3° after the 1st LLIF and further to 4.4 ± 5.1° following the 2nd PCO/PSF. Similarly, the UCC and LCC angles averaged 36.1 ± 17.6° and 18.0 ± 10.9°, respectively, at baseline, then improved to 29.7 ± 15.4° and 16.3 ± 10.1°and further to 8.6 ± 8.4° and 5.7 ± 6.1°.

Notable enhancements were observed in coronal alignment metrics, including the C7PL-CSVL and AVT, compared to the preoperative values. No significant loss of correction was noted during the last follow-up for the coronal parameters.

Analysis of predictive thresholds for postoperative imbalance

Based on the ideal sagittal correction goals proposed by Schwab et al.17 and the coronal balance criterion proposed by Bao et al.18we categorized the immediate postoperative standing radiographic parameters into two groups: immediate postoperative balance and immediate postoperative imbalance.

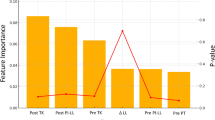

Comparing spinopelvic parameters between the two stages and the two groups (Table 3), significant differences were observed for Pre-PI-LL, Pre-TK, Pre-SVA, and M-PI-LL, M-LL, M-PT, M-PI, M-SVA, M-TPA after the 1st LLIF. Binary logistic regression analysis (Fig. 4), with postoperative SVA ≥ 50 mm as the dependent variable and the aforementioned parameters as independent variables, identified M-SVA as a significant risk factor for postoperative SVA ≥ 50 mm (OR: 1.017). ROC revealed a cut-off value of M-SVA of 75.3 mm (sensitivity 73.5%, specificity 64.4%) for predicting postoperative imbalance.

Using the same analytical model for parameter differences (Table 3). Binary logistic regression analysis (Fig. 5), with postoperative PI-LL > 10° as the dependent variable, identified M-PI-LL as a significant risk factor (OR: 1.086). ROC demonstrated a cut-off value of M-PI-LL of 32.5° (sensitivity 57.5%, specificity 73.1%) for predicting postoperative imbalance.

Binary logistic regression analysis (Fig. 6), with postoperative PT ≥ 25° as the dependent variable, identified Pre-PT, Pre-PI, and M-PT, M-PI as significant risk factors, with OR of 1.13, 1.057, 1.1, and 1.055, respectively. ROC revealed cut-off values of 41.5° for Pre-PT (sensitivity 53.2%, specificity 86.5%), 50.5° for Pre-PI (sensitivity 78.7%, specificity 59.6%), 35.5 ° for M-PT (sensitivity 57.4%, specificity 78.8%), and 52.5 °for M-PI (sensitivity 83.0%, specificity 61.5%) for predicting postoperative imbalance.

Radiographic correction rate and contribution

For the sagittal plane (Table 4), the total correction percentage for PI-LL was 80.9%, with contributions of 64.5% from the 2nd stage. Similarly, for PT, the total correction percentage was 40.5%, with contributions of 60.6% from the 2nd stage. For C7 SVA, the mean total correction percentage was 69.1%, with contributions of 54.3% from the 2nd stage. Other sagittal parameters, such as LL, TK, SS, and TPA, indicated that the 2nd PCO/PSF procedure contributed more significantly to the overall correction.

Consistent with the findings for sagittal parameters, the results of coronal plane demonstrated that the 2nd stage procedure had a greater impact on correction.

Clinical outcomes

Significant improvement was found between the preoperatively and two-year last follow up in ODI scores and each domain of SRS-22 questionnaire (Table 5).

Discussion

As summarized in Table 4, the 2nd stage procedure consistently provided a more significant contribution to overall correction in both the sagittal and coronal planes in two-stage corrective surgeries for ASD. Akihiko Hiyama et al.15 evaluated the efficacy of stand-alone LLIF in improving spinal alignment in patients with ASD using computed tomography (CT). Their findings suggest that achieving more than 10 degrees of lordosis in the lower lumbar spine through stand-alone LLIF for ASD correction is challenging. Consequently, additional corrective procedures, such as osteotomy or posterior fusion with compression techniques, may be necessary during the second-stage surgery. Furthermore, they observed that patients with Obeid type 2 coronal malalignment may require supplementary posterior correction techniques, such as the kickstand rod technique, to optimize coronal balance distance (CBD)19. Similarly, Frank L. Acosta Jr. et al.20 concluded that while LLIF increases the segmental sagittal Cobb angle, these changes do not necessarily translate into improvements in regional or global sagittal alignment. Therefore, LLIF alone may not be a sufficient strategy for addressing sagittal plane abnormalities, and a combined approach incorporating LLIF with open posterior osteotomies may be required for adequate sagittal correction. Nakashima H. et al.21 further demonstrated that LLIF could restore sagittal alignment in ASD patients; however, the extent of correction was significantly influenced by the presence of Schwab grade 2 osteotomy and the occurrence of anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL) rupture. Furthermore, Dingli Xu et al.22 proposed that modifying the Lenke-Silva classification by performing an initial LLIF may help prevent the need for osteotomies and facilitate the determination of optimal fusion levels during the second-stage surgery. Consequently, preoperative planning for the 2nd stage should be conducted with heightened precision and should serve as a critical framework to achieve optimal staged correction goals postoperatively.

Based on the aforementioned parameters for postoperative balance (Fig. 7): (1) C7 SVA < 50 mm: A total of 102 cases were classified as having immediate postoperative balance. At the final follow-up, 58.8% maintained balance, while 41.2% progressed to imbalance. Of the 49 cases classified as immediate postoperative imbalance, 83.7% remained imbalanced and 16.3% improved to a balanced state; (2) PI-LL ≤ 10°: A total of 78 cases were categorized as having immediate postoperative balance. Of these, 67.9% maintained balance at the final follow-up, while 32.1% progressed to imbalance. Among the 73 cases classified as immediate postoperative imbalance, 80.8% remained imbalanced and 19.2% improved to balance; (3) PT < 25°: A total of 104 patients were classified as having immediate postoperative balance. Of these, 41.3% maintained balance at the final follow-up, whereas 58.7% progressed to imbalance. Among the 47 cases classified as immediate postoperative imbalance, 93.6% remained imbalanced and 6.4% improved to balance; (4) C7PL-CSVL < 30 mm: 123 patients were classified as having immediate postoperative balance. At the final follow-up, 87.8% maintained balance, while 15 12.2% progressed to imbalance. Among the 28 cases classified as immediate postoperative imbalance, 50.0% remained imbalanced and 50.0% improved to balance. The relationship between immediate postoperative imbalance and the rate of compensatory self-correction at the two-year follow-up revealed that compensatory capacity in the sagittal plane is lower than that in the coronal plane.

Additionally, sagittal plane balance achieved immediately postoperatively tends to deteriorate over time (Table 2), leading to progressive imbalance during follow-up23,24,25. The study by Lo et al.25 demonstrated that postoperative reciprocal sagittal imbalance following staged correction surgery for ASD adversely affects quality of life. The compensatory mechanisms responsible for maintaining sagittal alignment in adults weaken with aging, resulting in gradual postural deterioration and negatively impacting clinical outcomes25,26,27,28,29.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the preoperative sagittal correction strategy employed in the 2nd stage plays a critical role in determining postoperative spinal balance. The staged correction strategy for ASD, originally proposed by Yoshida et al.11was primarily intended to reduce surgical complications. However, it also offers an additional opportunity for preoperative planning, allowing for more detailed analysis and refinement of surgical strategies through the evaluation of interim preoperative imaging. Therefore, utilizing predictive thresholds derived from the 2nd preoperative imaging to guide the subsequent surgical intervention may help prevent postoperative sagittal malalignment.

This study compared balanced and imbalanced groups following staged corrective surgery for ASD, employing regression analysis and ROC curve analysis to identify predictive thresholds prior to the 2nd surgery. For instance, if a patient’s radiographic parameters after the 1st LLIF surgery exceed the threshold values (M-SVA: 75.3 mm; M-PI-LL: 32.5°; M-PT: 35.5°), the 2nd surgical plan should incorporate more advanced osteotomy techniques, such as pedicle subtraction osteotomy (PSO) or vertebral column resection (VCR) to achieve the immediate postoperative radiographic balance29,30.

This study has several limitations. First, it lacks a one-stage surgery control group. Without this comparator, it remains uncertain whether the two-stage surgical strategy guided by imaging-based thresholds yields superior, equivalent, or inferior outcomes. Second, although the proposed threshold values were statistically derived, their external validity has not been confirmed. Without independent validation, their clinical applicability is limited, and there is a risk of overfitting to the specific dataset used. Third, the retrospective, single-center design introduces potential biases, as surgical planning and outcomes in ASD may be significantly influenced by institutional protocols and individual surgeon experience. Fourth, the study design excluded a substantial number of cases. Although this was intended to ensure a more homogeneous study population under well-defined surgical and neuromuscular conditions, such extensive exclusions may compromise the clinical applicability of the statistical results.

In conclusion, using these predictive thresholds as reference guidelines for the preoperative planning of the 2nd stage surgery can effectively reduce the risk of immediate postoperative imbalance following two-stage surgery.

Data availability

The author confirms that all data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. Considering patient privacy, the patient’s name has been concealed. The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from Dr. Yuan-Shun Lo.

Abbreviations

- ASD:

-

Adult spinal deformity

- LLIF:

-

Lateral lumbar interbody fusion

- PCO:

-

Posterior column osteotomy

- PSF:

-

Posterior spinal fusion

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- TK:

-

Thoracic kyphosis

- LL:

-

Lumbar lordosis

- PT:

-

Pelvic tilt

- SS:

-

Sacral slope

- PI:

-

Pelvic incidence

- TPA:

-

T1 pelvic angle

- PI-LL:

-

PI minus LL mismatch

- C7 SVA:

-

C7 sagittal vertical axis

- UCC:

-

Cobb angle of upper coronal curve

- LCC:

-

Cobb angle of lower coronal curve

- TCC:

-

Cobb angle of total coronal curve

- C7PL-CSVL:

-

C7 coronal plumb line to the central sacral vertical axis

- AVT:

-

Apical vertebral translation

- Pre-:

-

Preoperative to the 1st stage LLIF surgery

- M-:

-

Postoperative following the 1st stage LLIF surgery

- Post-:

-

Postoperative following the 2nd stage PCO/PSF surgery

- F-:

-

Two-year postoperative follow-up

- ODI:

-

Oswestry Disability Index

- SRS-22:

-

Scoliosis Research Society-22 questionnaire

- ROC:

-

Teceiver operating characteristic

References

Takemoto, M. et al. Sagittal malalignment has a significant association with postoperative leg pain in adult spinal deformity patients. Eur. Spine J. 25, 2868–2875 (2016).

Häkkinen, A. et al. Spinopelvic changes based on the simplified SRS-Schwab adult spinal deformity classification: relationships with disability and health-related quality of life in adult patients with prolonged degenerative spinal disorders. Spine 42, E304–E310 (2017).

Li, G. et al. Adult scoliosis in patients over sixty-five years of age: outcomes of operative versus nonoperative treatment at a minimum two-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 34, 2165–2170 (2009).

Smith, J. S. et al. Risk-benefit assessment of surgery for adult scoliosis: an analysis based on patient age. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 36, 817–824 (2011).

Bridwell, K. H. et al. Does treatment (nonoperative and operative) improve the two-year quality of life in patients with adult symptomatic lumbar scoliosis: a prospective multicenter evidence-based medicine study. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 34, 2171–2178 (2009).

Schwab, F. J. et al. Risk factors for major perioperative complications in adult spinal deformity surgery: a multi-center review of 953 consecutive patients. Eur. Spine J. 21, 2603–2610 (2012).

Glassman, S. D. et al. The impact of perioperative complications on clinical outcome in adult deformity surgery. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 32, 2764–2770 (2007).

La Maida, G. A. et al. Complication rate in adult deformity surgical treatment: safety of the posterior osteotomies. Eur. Spine J. 24, 7879–7886 (2015).

Sansur, C. A. et al. Scoliosis research society morbidity and mortality of adult scoliosis surgery. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 36, E593–E597 (2011).

Yamato, Y. et al. Planned two-stage surgery using lateral lumbar interbody fusion and posterior corrective fusion: a retrospective study of perioperative complications. Eur. Spine J. 30, 2368–2376 (2021).

Yoshida, G. et al. Predicting perioperative complications in adult spinal deformity surgery using a simple sliding scale. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 43, 562–570 (2018).

Ramieri, A., Miscusi, M., Domenicucci, M., Raco, A. & Martini, M. Surgical management of coronal and sagittal imbalance of the spine without PSO: a multicentric cohort study on compensated adult degenerative deformities. Eur. Spine J. 26, 442–449 (2017).

Murray, G. et al. Complications and neurological deficits following minimally invasive anterior column release for adult spinal deformity: a retrospective study. Eur. Spine J. 24, 397–404 (2015).

Anand, N. & Baron, E. M. Minimally invasive approaches for the correction of adult spinal deformity. Eur. Spine J. 22, S232–S241 (2013).

Hiyama, A. et al. Changes in spinal alignment following eXtreme lateral interbody fusion alone in patients with adult spinal deformity using computed tomography. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–8 (2019).

Schwab, F. et al. The comprehensive anatomical spinal osteotomy classification. Neurosurgery 76, S33–S41 (2015).

Schwab, F. et al. Scoliosis research Society-Schwab adult spinal deformity classification: a validation study. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 37, 1077–1082 (2012).

Bao, H. et al. Coronal imbalance in degenerative lumbar scoliosis. Bone Joint J. 98-B, 1227–1233 (2016).

Hiyama, A., Sakai, D., Katoh, H., Sato, M. & Watanabe, M. Postoperative radiological improvement after staged surgery using lateral lumbar interbody fusion for preoperative coronal malalignment in patients with adult spinal deformity. J. Clin. Med. 12, 2389 (2023).

Acosta, F. L. Jr et al. Changes in coronal and sagittal plane alignment following minimally invasive direct lateral interbody fusion for the treatment of degenerative lumbar disease in adults: a radiographic study. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 15, 92–96 (2011).

Nakashima, H. et al. Factors affecting postoperative sagittal alignment after lateral lumbar interbody fusion in adult spinal deformity: posterior osteotomy, anterior longitudinal ligament rupture, and endplate injury. Asian Spine J. 13, 738–745 (2019).

Xu, D. et al. Comparison of staged lateral lumbar interbody fusion combined two-stage posterior screw fixation and two osteotomy strategies for adult degeneration scoliosis: a retrospective comparative study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 24, 387 (2023).

Barrey, C., Roussouly, P., Le Huec, J. C., D’Acunzi, G. & Perrin, G. Compensatory mechanisms contributing to keep the sagittal balance of the spine. Eur. Spine J. 22, S834–S841 (2013).

Hasegawa, K. et al. Normative values of spino-pelvic sagittal alignment, balance, age, and health-related quality of life in a cohort of healthy adult subjects. Eur. Spine J. 25, 3675–3686 (2016).

Lo, Y. S. et al. Unveiling the impact of reciprocal changes in thoracic kyphosis after staged corrective surgery in adult deformity. Glob Spine J. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568225 (2025).

Diebo, B. G. et al. Sagittal alignment of the spine: what do you need to know? Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 139 , 295–301 (2015).

Cheung, J. P. Y. The importance of sagittal balance in adult scoliosis surgery. Ann. Transl. Med. 8 , 35 (2020).

Makhni, M. C. et al. Restoration of sagittal balance in spinal deformity surgery. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 61, 167–179 (2018).

Ha, K. Y. et al. Surgical strategy for revisional lumbar pedicle subtraction osteotomy to correct fixed sagittal imbalance. J. Orthop. Sci. 26, 750–755 (2021).

Cecchinato, R., Berjano, P., Aguirre, M. F. & Lamartina, C. Asymmetrical pedicle subtraction osteotomy in the lumbar spine in combined coronal and sagittal imbalance. Eur. Spine J. 24, S66–S71 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the help of Professor Hsien-Te Chen’s supervision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xue-Peng Wei, and Chen-Wei Yeh contributed equally to this study and are co-first authors. X.-P. X., Y.-S. L. designed and performed the experiments, Y.-S. L. developed the algorithm. X.-P. X. assisted in data analysis and figures, X.-P. X., Y.-S. L., and C.-W. Y. prepared the manuscript. All authors have contributed to the manuscript and approved the submitted version. We declare that AI-assisted technologies were not used to generate scientific or interpreted data. AI technologies were only used to perform grammar checks on completed manuscripts to improve linguistic accuracy under the supervision of all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital (Approval Number CMUH111-REC1-128) and performed in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, XP., Yeh, CW., Lin, ET.E. et al. Predicting postoperative imbalance in adult spinal deformity staged surgery using predictive thresholds. Sci Rep 15, 32002 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18031-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18031-9