Abstract

The Stress Hyperglycemia Ratio (SHR) has emerged as a prognostic indicator associated with adverse outcomes in a variety of diseases. Nevertheless, the relationship between SHR and the prognosis of individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) has yet to be clarified. This research examines the association between SHR and outcomes in COPD patients. This study employed the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC-IV) database to identify patients with COPD requiring admission to the intensive care unit, categorizing them into quartiles according to SHR levels. The outcomes assessed encompassed in-hospital mortality and ICU mortality. The analysis utilized Cox proportional hazards regression, enhanced by restricted cubic splines, to explore the association between SHR and the clinical manifestations present in patients diagnosed with COPD. The study included 1157 COPD patients. The mortality rates were 10.11% for in-hospital, and 7.09% for ICU, respectively. The analysis of Kaplan-Meier (K-M) curves revealed a noteworthy correlation between elevated SHR levels and an augmented risk of mortality in both hospital and ICU environments. Patients with COPD who were in the highest SHR index quartile were at the highest risk of dying, according to a Cox proportional hazards regression analysis (hospital, HR: 1.88,95%CI:1.09–3.25, P = 0.002; ICU: HR: 3.64, 95%CI:1.79–7.42, P < 0.001). Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis revealed a U-shaped association between the SHR index and both in-hospital and ICU mortality rates. Elevated SHR levels in COPD patients are significantly linked to a higher mortality risk in both hospitalized and ICU settings. The SHR index serves as a valuable tool for assessing in-hospital outcomes in COPD patients and holds potential to aid in screening high mortality risk COPD patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

COPD ranks among the prevalent chronic respiratory conditions1. Airway obstruction, inflammation, and alveolar destruction lead to symptoms like dyspnea, cough, and sputum production2. Currently, COPD ranks as the fourth most significant cause of mortality worldwide, affecting over 350 million people worldwide, with more than 35 million deaths annually3,4. Thus, COPD has become a significant public health issue. COPD not only causes direct human suffering but also escalates the risk of lung cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and other prominent causes of death by a factor of two to four, thereby imposing a considerable burden on both individuals and society5,6,7. As a result, poor prognosis of COPD patients is frequently encountered in intensive care units (ICUs). A study indicates that critically ill COPD patients have a markedly increased mortality risk compared to non-COPD patients8. This finding emphasizes the significant mortality risk that COPD poses to individuals who are in severe condition. The incidence of hospitalized acute exacerbations of COPD among ICU admissions ranges from 2–19%9,10. The importance of metabolism in chronic lung disorders has been highlighted by recent research, which connects it to the higher incidence, prevalence, or severity of COPD11. This link has prompted speculation that glycemic factors might directly influence lung function and disease progression.

Studies have found that hyperglycemia can lead to a significant increase in inflammatory factors in the serum of COPD patients, associated with a marked decline in pulmonary function. In certain acute clinical situations, patients may experience stress hyperglycemia, marked by a temporary rise in blood glucose levels due to physiological stress, often indicating disease severity12,13. According to research, critically ill patients often have stress-induced hyperglycemia, which is linked to a higher risk of death. Stress hyperglycemia indicates the initial blood glucose level, but plasma glucose is influenced by various factors, including prior blood glucose levels. Therefore, to better reflect the actual blood glucose state of patients, the SHR has been proposed14,15. This indicator assesses an individual’s stress-induced blood glucose level relative to their prior glucose management. It indirectly indicates disease severity and the body’s stress response capability. Accurate SHR calculation enables doctors to effectively manage patients’ blood glucose levels, minimizing adverse effects and enhancing the prognosis for critically ill COPD patients.

Research on the SHR in COPD patients, particularly those critically ill with poor prognosis, remains incomplete. Using information from the MIMIC-IV database, the aim of this study is to investigate the independent influence of the SHR ratio on mortality rates in both the hospital and ICU environments.

Method

Source of data

Data sourced from the publicly available MIMIC-IV database is examined in this retrospective analysis. This dataset covers 450,000 hospital admissions at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts, from 2008 to 2019. Comprehensive records including patient demographics, lab results, prescription drugs, vital signs, surgery, illness diagnosis, medication administration, and follow-up survival status are available in the database.

We obtained access to the data by completing the NIH training on human research participant protection and passing the CITI exam (ID:12899457). The requirement for informed consent was deemed unnecessary due to the absence of protected health information within the database, as all patient data have been anonymized.

Study design

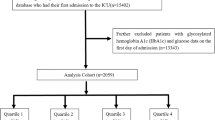

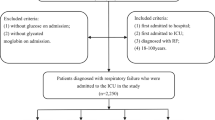

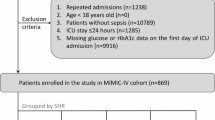

Of the 23,818 COPD patients (utilizing ICD9 codes: 49120, 49121, 49122, 496 and ICD10 codes: J44, J440, J441, J449) from the MIMIC-IV database were included in our research. ICD codes for the diseases are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Patients were excluded if they: (1) had previous ICU admissions; (2) lacked HbA1c and blood glucose data post-admission; (3) stayed in the ICU for under 24 h. After meeting the inclusion requirements, 1,157 patients were split up into four groups based on their SHR quartiles (Fig. 1).

Data extraction

R was used to extract the data (version 4.4.2). The study analyzed variables grouped into demographics, Age, sex, and body mass index (BMI) are among the characteristics taken into account, BMI was calculated using the standard formula: body weight (kg)/height2(m). Myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure (HF), cerebrovascular illness, liver disease, diabetes mellitus (DM), cancerous tumors, and hypertension were among the patients’ prior medical conditions. Heart rate (HR), mean blood pressure (MBP), systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP, respectively), and body temperature are all considered vital indicators. Laboratory parameters encompass mean glucose levels, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), platelet count, white blood cell count (WBC), Prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), creatinine levels, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and international normalized ratio (INR). All vital signs and laboratory parameters were measured within 24 h of admission. Furthermore, hospital and intensive care unit death rates, length of stay (LOS). The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II), Oxford Acute Severity of Illness Score (OASIS), Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS), and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) were among the scores used to evaluate the severity of the disease. Upon admission, prior to any therapeutic interventions, blood biochemical variables were initially assessed. Variables having more than 20% missing data were not included in the study. The random forest approach was used to do data imputation for those with missing values less than 20%.

Outcome

ICU all-cause mortality was the study’s main endpoint, while in-hospital all-cause mortality was its secondary.

SHR

The SHR was determined using the formula: SHR = admission blood glucose (mg/dl)/(28.7 × HbA1c (%) − 46.7)16.

Statistical analysis

The incidence of both main and secondary outcomes, stratified by SHR, was assessed using K-M curves. The association between the SHR index and both in-hospital and ICU mortality was evaluated using univariate Cox analysis, univariate Cox regression results are presented in Supplementary Table 2. Clinically relevant variables or variables with univariate relationships to the outcomes were included in multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models. The proportional hazards hypothesis in multivariate Cox regression analysis was evaluated using Schoenfeld residual test (Supplementary Fig. 1). The number of available events was carefully taken into consideration when choosing the final model variables.

Only the SHR index was used in Model 1. Model 2 included adjustments for age, sex, HR, MBP, MI, Cerebrovascular disease, plt, and WBC. Model 3 further adjusted for age, sex, HR, MBP, MI, Cerebrovascular disease, plt, WBC, INR, SOFA, and CCI. In all models, the reference group was the SHR index’s Q2 group.

To get a better understanding of the SHR index’s dose-response connection to the risks of main and secondary outcomes, we further analyzed the SHR index as a continuous variable, employing RCS. The non-linear association between the SHR index and the rates of in-hospital and intensive care unit mortality was examined for inflection points using a recursive algorithm. Leveraging the inflection point identified via stratified Cox regression, we employed a two-segment Cox proportional-hazards model to examine the association between the SHR index and mortality. Stratified analyses were performed considering gender, age, HR, MI, DM, and cerebrovascular disease history.

Statistical analyses were done using R software (version 4.4.2), with a significance threshold set at P < 0.05.

Results

Clinical profiles of participants

In this research, 1,157 COPD patients who met the inclusion criteria were found by looking through data from 94,458 individuals in the MIMIC-IV database. 49.01% of the participants were female, and their average age was 68.84 years. Upon admission, participants were divided into four groups according on their SHR index quartiles: Q1 (0.307–0.927), Q2 (0.928–1.103), Q3 (1.104–1.334), and Q4 (1.335–4.242). Individuals in the group with the highest SHR score (Q4) were older and had greater MI prevalence rates, HF, liver disease, DM, hypertension, and malignant tumors. Their vital signs, including weight and heart rate, along with laboratory indicators like creatinine, BUN, WBC, INR, PT, and PTT, were significantly elevated compared to other groups (Table 1).

Group Q4 exhibited significantly higher disease severity scores, including CCI, APSIII, and SOFA, at ICU admission and during hospitalization compared to the other three groups, and also experienced the longest hospital stay. Group Q4 exhibited significantly higher in-hospital and ICU mortality rates compared to other groups (12.33% vs. 5.15%, 3.83%, and 6.99%, P < 0.001).

Study outcomes

The K-M curves depicted in Fig. 2 revealed disparities in 30-day and 90-day mortality across the four SHR quartile groups, both within hospital and ICU settings. Interestingly, compared to patients in the lower SHR quartiles, those in the highest SHR quartile (Q4) had substantially decreased survival probability at the 30- and 90-day points (P < 0.05).

We utilized two Cox regression models for analysis (Table 2). After adjusting for age, sex, HR, MBP, MI, Cerebrovascular disease, plt, and WBC, the hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for ICU mortality were calculated. SHR was categorized into quartiles Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4, with Q2 serving as the reference group (HR = 1.00). The hazard ratios for the other quartiles were Q1: 2.46 (95% CI: 1.12, 5.44), Q3: 2.04 (95% CI: 0.96, 4.33), and Q4: 3.79 (95% CI: 1.87, 7.68). After controlling for age, sex, HR, MBP, MI, Cerebrovascular disease, plt, WBC, INR, SOFA, and CCI, the HR and 95% CI for different SHR index categories, using HR = 1.00 as the reference for ICU mortality, were 2.33 (1.05, 5.16), 2.09 (0.98, 4.47), and 3.64 (1.79, 7.42).The findings suggest that SHR indices above 1.103 and at or below 0.927 elevate the mortality risk in hospitalized and ICU patients.

Nonlinear relationship detection

The analysis of RCS has revealed a nonlinear association between the SHR index and mortality risk in both hospitalized patients and those in the ICU. More precisely, The SHR index demonstrated a U-shaped relationship in its correlation with ICU and hospital mortality, which remained the same after adjusting for the aforementioned covariates (Fig. 3B). A similar relationship was observed in the analysis of hospitalized patients (Fig. 3A).

In the model for ICU mortality risk, after adjusting for the aforementioned covariates, we found that the P for Log-likelihood ratio was < 0.05 for all three models, with an inflection point of 0.976.A similar phenomenon was also observed in the model for in-hospital mortality risk (Tables 3 and 4).

Upon reaching or surpassing a SHR value of 0.976, each one-unit increase in the SHR level corresponded to a 257.5% rise in the risk of mortality in the ICU (P < 0.001; 95% CI: 2.230 to 5.729). In a comparable manner, an increase of one unit in SHR was associated with a 182% heightened risk of in-hospital mortality (P < 0.0001; 95% CI: 1.803 to 4.411).

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses were performed to evaluate the consistency of the relationship between SHR levels and all-cause mortality among patients in the ICU and those hospitalized under various conditions, including gender, age, HR, DM, CI, MI, and cerebrovascular disease. In females and individuals over 65, the HR for mortality in hospitalized and ICU patients were significantly higher in Q4 compared to Q1 (P < 0.05). In ICU patients with elevated SHR levels, significant hazard ratios for mortality were observed, regardless of the presence of cerebrovascular disease (P < 0.05). In hospitalized patients, irrespective of their diabetes or cerebrovascular disease status, the mortality hazard ratios were found to be significant (P < 0.05). Nonetheless, no statistical significance was detected among the hospitalized and ICU patients in the Q2 and Q3 groups (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Previous studies have reported an association between SHR and COPD patients17, here, we applied the internationally validated SHR formula to investigate its relationship with outcomes in hospitalized and ICU patients. The results indicate a U-shaped relationship between SHR and mortality rates in these contexts, suggesting that beyond a specific threshold, higher SHR levels correlate with increased mortality in these settings. In our cohort, the Q2 group (SHR ≈ 0.928–1.103) exhibited the lowest mortality risk, suggesting this range represents a metabolically optimal state. These findings support the use of SHR within this interval to identify and stratify high-risk patients, but prospective validation is required.

Stress hyperglycemia is a frequent temporary physiological reaction in patients with acute or critical conditions, typically engaging the hypothalamic-pituitary and sympathetic nervous systems, resulting in insulin resistance, inflammation, and significant glucose metabolic disturbances18,19. However, relying solely on the blood glucose levels at admission to assess the stress-induced hyperglycemic response is insufficient for a comprehensive evaluation, as it overlooks the blood glucose fluctuations in patients with long-term chronic diabetes. Therefore, we introduced SHR to assess the hyperglycemia induced by stress responses. Studies have found that SHR has significant predictive power for mortality risk in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), coronary heart disease, severe infections, and critical conditions caused by surgery or trauma14,20,21,22. In critically ill coronary heart disease patients, SHR exhibits a J-shaped correlation with both in-hospital and ICU mortality rates22. Furthermore, SHR also shows a nonlinear relationship with critically ill patients with severe infections14. Thus, SHR is linked to certain infectious and cardiovascular factors.

Studies have found that infusing glucose into animals for 3 h significantly impairs their immune function and activates cytokines. During hyperglycemia, glucose non-enzymatically glycates proteins, leading to the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs)23. AGEs have the capacity to bind to receptors located on the surface of lung cells, thereby activating inflammatory signaling pathways and releasing more inflammatory factors, such as TNF-α and IL-624,25. Elevated blood sugar levels prompt monocytes to increase IL-6 production and release. Increased serum IL-6 levels can worsen insulin resistance, inducing the liver to secrete glucose, thereby leading to hyperglycemia26. It can worsen lung inflammation, resulting in heightened airway hyperresponsiveness and restricted airflow27. Furthermore, studies have shown that hyperglycemia may suppress the body’s immune function, reducing the phagocytic and bactericidal capabilities of white blood cells, making COPD patients more susceptible to respiratory infections28,29. Respiratory infections are an important trigger for the acute exacerbation of COPD, and infections can worsen airway inflammation and airflow limitation, creating a vicious cycle30,31. Numerous studies have shown that high blood sugar levels may have pro-inflammatory effects. The study reveals that a SHR of 0.987 corresponds to the lowest mortality risk for COPD patients. Therefore, lower blood sugar levels are beneficial for reducing the mortality risk in COPD patients, while too low or too high blood sugar levels can increase the mortality risk.

Additionally, COPD patients may also develop a state of hyperglycemia32. COPD is characterized by systemic inflammation, characterized by heightened levels of inflammatory mediators including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and C-reactive protein (CRP)33. These factors can disruption in the insulin signaling pathway can lead to insulin resistance and consequently, increased blood glucose levels34. Secondly, hypoxemia is a common complication in COPD patients. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) is activated under hypoxic conditions, promoting glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, thereby increasing glucose production35. Lastly, under hypoxic conditions, there is a decrease in the absorption and utilization of glucose by peripheral tissues, such as muscles. Additionally, in patients with acute exacerbation and critical conditions of COPD, glucocorticoids are commonly used. Glucocorticoids also reduce tissue glucose uptake and utilization, while promoting glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, further increasing blood glucose levels36.

In summary, our study demonstrates that SHR can aid clinicians in identifying patients at higher risk of adverse outcomes and thereby facilitating better glycemic control in clinical practice. Compared to other prognostic tools, SHR is characterized by its ease of calculation and accessibility, requiring only routine laboratory tests at admission, making it a rapid and cost-effective tool for prognostic assessment in clinical practice37. Additionally, we found that both elevated and low SHR levels are associated with increased mortality risk in COPD patients. First, elevated SHR increases mortality risk in COPD patients, possibly due to underlying pathological mechanisms such as oxidative stress and immune dysfunction38. However, we also found that low SHR levels increase mortality risk in COPD patients. Low SHR may be associated with hypoglycemia, which typically activates the sympathetic-adrenal system, increasing the risk of cardiovascular diseases and thereby potentially increasing mortality risk in COPD patients39. Second, low SHR may also be associated with high HbA1c, indicating poor glycemic control before admission. Poor glycemic control significantly reduces lung function and increases infection risk40,41, both of which can increase mortality risk in COPD patients, consistent with our findings.

This study has several limitations. First, the analysis relied on the single-center, retrospective MIMIC-IV database, and the cohort was predominantly composed of US patients with limited racial diversity, which may restrict the generalizability of our findings to the global COPD population. Second, the database lacks detailed information on inpatient glycaemic management—such as insulin dosage, protocols, and dynamic adjustments—that could directly modify SHR values and their clinical implications. Third, SHR was calculated using only admission glucose and HbA1c, introducing potential measurement error; future studies should incorporate serial glucose measurements and dynamic SHR to capture its temporal variability. Despite extensive covariate adjustment and subgroup analyses, residual confounding cannot be completely excluded. In addition, because our study is observational, the U-shaped association between SHR and mortality cannot be interpreted as causal, and prospective cohorts are needed to confirm directionality. Finally, the underlying biological mechanisms that might explain this non-linear pattern remain speculative, and dedicated mechanistic experiments are required to elucidate how both low and high SHR values could influence patient outcomes.

Conclusion

This study concludes that SHR exhibits a U-shaped relationship with in-hospital and ICU mortality in COPD patients, where elevated SHR is significantly linked to a higher mortality risk. Our findings provide a foundation for future prospective studies and clinical trials.

Data availability

The data in the study was provided by the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV 3.0), and the following licenses/restrictions apply: To obtain access to these files, you are required to be a credentialed user, finish necessary training as well as sign the project data use agreement. The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lareau, S. C., Fahy, B., Meek, P. & Wang, A. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 199 (1), P1–p2 (2019).

Kahnert, K., Jörres, R. A., Behr, J. & Welte, T. The diagnosis and treatment of COPD and its comorbidities. Dtsch. Arztebl Int. 120 (25), 434–444 (2023).

López-Campos, J. L., Tan, W. & Soriano, J. B. Global burden of COPD. Respirology 21 (1), 14–23 (2016).

Raherison, C. & Girodet, P. O. Epidemiology of COPD. Eur. Respir Rev. 18 (114), 213–221 (2009).

Forder, A. et al. Mechanisms contributing to the comorbidity of COPD and lung cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. ;24(3). (2023).

Rabe, K. F., Hurst, J. R. & Suissa, S. Cardiovascular disease and COPD: dangerous liaisons? Eur. Respir Rev. ;27(149). (2018).

Yang, H. M. et al. Differential association of COPD subtypes with cardiovascular events and COPD exacerbations. Chest 166 (6), 1360–1370 (2024).

Funk, G. C. et al. Prevalence and prognosis of COPD in critically ill patients between 1998 and 2008. Eur. Respir J. 41 (4), 792–799 (2013).

Dixit, D. et al. Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: diagnosis, management, and prevention in critically ill patients. Pharmacotherapy 35 (6), 631–648 (2015).

Messer, B., Griffiths, J. & Baudouin, S. V. The prognostic variables predictive of mortality in patients with an exacerbation of COPD admitted to the ICU: an integrative review. Qjm 105 (2), 115–126 (2012).

Nambiar, S., Bong How, S., Gummer, J., Trengove, R. & Moodley, Y. Metabolomics in chronic lung diseases. Respirology 25 (2), 139–148 (2020).

Chen, G., Lin, Q., Zhuo, D. & Cui, J. Elevated blood glucose is associated with severe exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 17, 2453–2459 (2022).

Nkhumeleni, Z., Phoswa, W. N. & Mokgalaboni, K. Purslane ameliorates inflammation and oxidative stress in diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 22 (2024).

Yan, F. et al. Association between the stress hyperglycemia ratio and 28-day all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis: a retrospective cohort study and predictive model establishment based on machine learning. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23 (1), 163 (2024).

Zhang, C. et al. Relationship between stress hyperglycemia ratio and allcause mortality in critically ill patients: results from the MIMIC-IV database. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1111026 (2023).

Roberts, G. W. et al. Relative hyperglycemia, a marker of critical illness: introducing the stress hyperglycemia ratio. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 100 (12), 4490–4497 (2015).

Qiao, M., Yang, H., Qin, M., Li, Y. & Wang, H. Increased Stress Hyperglycemia Ratio Predicts Poor Clinical Outcome in Critically Ill COPD Patients: A Retrospective Study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. ;20:1203 – 15.10.2147/copd.S520418. (2025).

Dungan, K. M., Braithwaite, S. S. & Preiser, J. C. Stress hyperglycaemia. Lancet 373 (9677), 1798–1807 (2009).

Bellis, A. et al. Stress-Induced hyperglycaemia in Non-Diabetic patients with acute coronary syndrome: from molecular mechanisms to new therapeutic perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. ;22(2). (2021).

Cheng, S., Shen, H., Han, Y., Han, S. & Lu, Y. Association between stress hyperglycemia ratio index and all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with atrial fibrillation: a retrospective study using the MIMIC-IV database. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23 (1), 363 (2024).

He, H. M. et al. Simultaneous assessment of stress hyperglycemia ratio and glycemic variability to predict mortality in patients with coronary artery disease: a retrospective cohort study from the MIMIC-IV database. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23 (1), 61 (2024).

Chen, X., Yang, Z., Shi, R., Wang, X. & Li, X. Stress hyperglycemia ratio association with all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with coronary heart disease: an analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 29110 (2024).

Kwoun, M. O. et al. Immunologic effects of acute hyperglycemia in nondiabetic rats. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 21 (2), 91–95 (1997).

Kellow, N. J. & Savige, G. S. Dietary advanced glycation end-product restriction for the Attenuation of insulin resistance, oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction: a systematic review. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 67 (3), 239–248 (2013).

Van Puyvelde, K., Mets, T., Njemini, R., Beyer, I. & Bautmans, I. Effect of advanced glycation end product intake on inflammation and aging: a systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 72 (10), 638–650 (2014).

Heesen, M., Bloemeke, B., Heussen, N. & Kunz, D. Can the interleukin-6 response to endotoxin be predicted? Studies of the influence of a promoter polymorphism of the interleukin-6 gene, gender, the density of the endotoxin receptor CD14, and inflammatory cytokines. Crit. Care Med. 30 (3), 664–669 (2002).

Papanicolaou, D. A., Wilder, R. L., Manolagas, S. C. & Chrousos, G. P. The pathophysiologic roles of interleukin-6 in human disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 128 (2), 127–137 (1998).

Turina, M., Fry, D. E. & Polk, H. C. Jr. Acute hyperglycemia and the innate immune system: clinical, cellular, and molecular aspects. Crit. Care Med. 33 (7), 1624–1633 (2005).

Andersen, S. K., Gjedsted, J., Christiansen, C. & Tønnesen, E. The roles of insulin and hyperglycemia in sepsis pathogenesis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 75 (3), 413–421 (2004).

Leung, J. M. et al. The role of acute and chronic respiratory colonization and infections in the pathogenesis of COPD. Respirology 22 (4), 634–650 (2017).

Whittaker, H. et al. Frequency and severity of respiratory infections prior to COPD diagnosis and risk of subsequent postdiagnosis COPD exacerbations and mortality: EXACOS-UK health care data study. Thorax 78 (8), 760–766 (2023).

Pu, X., Liu, L., Feng, B., Zhang, Z. & Wang, G. Association between ICS use and risk of hyperglycemia in COPD patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res. 22 (1), 201 (2021).

Christenson, S. A., Smith, B. M., Bafadhel, M. & Putcha, N. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 399 (10342), 2227–2242 (2022).

Wu, T. D. et al. Association of Triglyceride-Glucose index and lung health: A Population-Based study. Chest 160 (3), 1026–1034 (2021).

Taylor, C. T. & Scholz, C. C. The effect of HIF on metabolism and immunity. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 18 (9), 573–587 (2022).

Heo, Y. A. Budesonide/Glycopyrronium/Formoterol: A review in COPD. Drugs 81 (12), 1411–1422 (2021).

Li, L. et al. Prognostic significance of the stress hyperglycemia ratio in critically ill patients. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22 (1), 275 (2023).

González, P., Lozano, P., Ros, G. & Solano, F. Hyperglycemia and oxidative stress: an integral, updated and critical overview of their metabolic interconnections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. ;24(11). (2023).

Amiel, S. A. The consequences of hypoglycaemia. Diabetologia 64 (5), 963–970 (2021).

Chang, C. H. et al. Glycemic control, and risk of infection morbidity and mortality: A cohort study. Open. Forum Infect. Dis. 6 (10), ofz358 (2019).

Zhang, R. H. et al. Non-linear association between diabetes mellitus and pulmonary function: a population-based study. Respir Res. 21 (1), 292 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the MIMIC-IV database for providing publicly available data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design and conception: ZGS, JJ; data collection and analysis: YXC and ABL; manuscript drafting: YXC and ABL; data interpretation: LPZ and XLW. substantive revision: YXC, ABL and LPZ. All authors have reviewed and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The utilization of the MIMIC-IV database was sanctioned by the review boards of both the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Centre. Given the public availability of the data within the MIMIC-IV database, the study was exempt from the need for an ethics approval statement and informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Liu, A., Zhang, L. et al. Association between stress hyperglycemia ratio and all-cause mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Sci Rep 15, 32892 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18058-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18058-y