Abstract

Improving adherence enhances therapeutic outcomes in hemodialysis patients; several approaches, including behavioral interventions, were utilized to improve adherence. Examine the effect of a pharmacist-led behavioral change technique (PL-BCT) intervention on hemodialysis patients’ adherence to their complex therapeutic regimen and physical indices. Parallel-group, cluster-randomized, controlled trial, in which the patients were divided into usual care and PL-BCT groups. The intervention was developed based on the Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1). Adherence was assessed using the End-Stage Renal Disease Adherence Questionnaire (ESRD-AQ). After one month of intervention, the PL-BCT significantly increased the total adherence score compared to usual care (950.0 vs. 825.0). Good adherence rate was higher in the PL-BCT group (42.1% vs. 14.7%). The serum phosphate level (5.83 ± 0.90 vs. 5.84 ± 1.04 mEq/L) and interdialytic weight gain (2.0 vs. 2.9 kg) significantly declined in the PL-BCT compared to usual care. In the unadjusted analysis of the relationship between the intervention of good adherence, there was a 4.592-fold increase in the odds of achieving good adherence in the PL-BCT group compared to usual care OR (95%CI): 4.592 (1.662–12.686), p-value = 0.003; this strong association was maintained in the multivariate analysis. The findings of this study suggest that BCTs support adherence among hemodialysis patients and improve certain clinical indices.

Trial Registration The clinical trial registration number is NCT06744738, and the registration date is December 20, 2024.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease is a progressive, worldwide chronic disorder with substantial mortality risks and morbidity burdens1. End-stage chronic kidney disease (ESRD) is a life-threatening condition that requires renal replacement therapy with either renal transplantation or dialysis2. Dialysis is the core of managing ESRD patients, with hemodialysis (HD) being the most common type of dialysis worldwide3.

Patients’ adherence to their dialysis program is essential to their survival4. Patients must adhere to hemodialysis sessions and a complex therapeutic regimen covering several dimensions5. In general, hemodialysis therapeutic regimen adherence is evaluated across four aspects: attending hemodialysis sessions for the prescribed frequency and time, taking medications as prescribed, following dietary recommendations, and fluid restriction6. Non-adherent behavior is a widespread problem with significant clinical relevance among dialysis patients, contributing to morbidity, avoidable hospitalization, and death7,8. Missed or shortened hemodialysis sessions can increase hospital admissions and mortality risk among hemodialysis patients by 13–30%8,9,10. Non-adherence to prescribed medications can lead to rapid deterioration of cardiovascular diseases, which are a major cause of high mortality rates in hemodialysis patients11. Fluid restriction is another important dimension where non-adherence to fluid restriction can lead to serious clinical outcomes such as hypertension, congestive heart failure, pulmonary edema, and increased incidence of muscle cramps, vomiting, nausea, anxiety, panic, and hypotension during dialysis12. Non-adherence to dietary recommendations can lead to several problems that can be an important indicator of morbidity and mortality13. Non-adherence is a global concern, and Iraq is no exception, with hemodialysis patients in Iraq showing less than optimal adherence to various treatment modalities, with an average adherence score indicating moderate adherence14. Another study also showed poor adherence behaviors toward hemodialysis attendance, medications, fluid restrictions, and dietary restrictions among Iraqi hemodialysis patients15.

Many interventions have been developed to enhance the adherence and patient outcomes of renal dialysis patients, and many approaches have been adopted, mainly educational and behavioral interventions16. Behaviorally informed interventions aimed to change the adherence behavior using particular theory-based techniques or combinations of techniques (e.g., motivational interviewing, self-affirmation theory, etc.). However, these theories-based interventions often offered fixed packages of behavioral change approaches without the flexibility of tailoring to the individual patient’s needs with a lack of a common language to define the context of an effective intervention clearly; this is supported by a recent study showing the inadequacy of one-size-fits-all approaches to improving adherence among patients on hemodialysis17.

An Intervention Mapping taxonomy of behavior change method offers the flexibility to customize the behavioral intervention according to the individual patient’s condition and needs and a precise description of the intervention. This behavioral change techniques (BCTs) taxonomy was developed by 54 experts in delivering and/or designing behavior change interventions18. One-size-fits-all approaches to improving adherence among patients on hemodialysis are inadequate. The BCTs taxonomy v1 is an extensive taxonomy comprising an extensive hierarchical classification of clearly labeled, well-defined 93 BCTs, developed as a method for specifying, evaluating, and implementing behavior change interventions that can be applied to various settings, including organizational and community settings18.

Pharmacists are particularly well-placed to utilize BCTs within their practice and have the potential to reduce the effects of chronic disease on mortality19,20,21,22 as well as to reduce the demand on hospital emergency departments and general practice clinics23. However, very few studies have explored the impact of pharmacist-led interventions on the adherence of hemodialysis patients24,25,26,27.

To our knowledge, no randomized controlled studies have employed the behavioral change technique as an Intervention Mapping tool to evaluate the effectiveness of a pharmacist-led intervention in improving adherence among hemodialysis patients. We hypothesize that adherence scores will be higher in the intervention group, to which the BCTs were applied, than in the usual-care group. At the same time, we hypothesized that the clinical indices (Phosphate, potassium, calcium, interdialytic weight gain (IDWG), and hemoglobin) would be better in the intervention group than in the usual-care group. The current study aimed to examine the effect of a pharmacist-led intervention on the adherence of renal hemodialysis patients to their complex therapeutic regimen and clinical indices, using behavior change techniques (BCTs) as an intervention.

Methods

Trial design

This parallel-group, cluster-randomized, controlled trial is designed to evaluate whether BCT benefits hemodialysis patients. The patients were divided into (1) a usual care group and (2) a pharmacist-led behavioral change technique (PL-BCT) group. Clinical trial registration (date: 20/12/2024): NCT06744738.

Setting

The study was conducted at the Dialysis Center of Baghdad Medical City in Baghdad, Iraq. This facility offers hemodialysis services to patients at no cost, with a total capacity of 81 beds at a time, and can cover three shifts daily. The study commenced on February 2, 2024, and was completed on June 25, 2024.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were adults (≥ 18 years of age), chronic kidney disease patients on standard in-center hemodialysis for at least three months, patients receiving 4 h per session, and moderate to poor adherence to their therapeutic regimen according to the End Stage Renal Disease Adherence Questionnaire (ESRD-AQ) at the time of inclusion28.

Exclusion criteria include switching from hemodialysis to peritoneal dialysis, receiving transplantation during the research period, inability to communicate for any reason (cognitive impairment, hearing, and visual loss, etc.), hemodialysis patients with viral hepatitis, and patient refusal to participate.

Patient recruitment

Based on the center workflow, we used dialysis sessions (shifts) as a cluster (by grouping the patients as they attend the center naturally). We assigned each cluster a unique identifier (A, B, C) reflecting the three shifts in the center. Then we used a computer-generated random sequence (via software, specifically Excel’s RAND function) to allocate clusters to either the intervention (PL-BCT) or the usual care group. This way, every patient within a given cluster will receive the same treatment, thereby preserving the integrity of the cluster design. Once clusters were randomized to their respective arms, the patients were approached within each cluster; we chose to enroll all eligible patients within the randomized clusters.

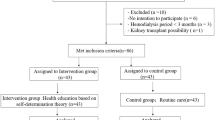

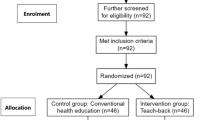

Initially, the authors screened 152 dialysis patients; 63 did not meet the inclusion criteria, and nine declined participation. The remaining 80 patients were allocated using a 1:1 ratio for both groups (40 patients per group). During the trial, six patients from the usual care group did not complete the study (one patient received peritoneal dialysis, two patients received a renal transplant, one patient died, and two patients were transferred to another dialysis center). Thus, 34 patients in the usual care group completed the study.

Two patients in the intervention group did not complete the study (one patient was lost to follow-up, and one was transferred to another dialysis center). Thus, 38 patients in the intervention group completed the study, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

As part of the inclusion criteria, the authors required that patients demonstrate moderate to poor adherence to their therapeutic regimen. This adherence status was determined using the End-Stage Renal Disease Adherence Questionnaire (ESRD-AQ). The ESRD-AQ was administered at baseline—before the initiation of any intervention sessions—to screen the patients and confirm that they met the adherence criteria for inclusion. This baseline measurement ensured that only those with less-than-optimal adherence were enrolled in the trial.

Interventions

Development of intervention

The intervention was developed using the behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) (BCTTv1)18. This intervention was designed to improve adherence to all therapeutic aspects of hemodialysis for patients, including the dialysis program, medications, diet, and fluid management. Additionally, the effect of the pharmacist intervention on clinical indices (serum potassium, total calcium, phosphate, IDWG, and hemoglobin) was examined.

The program was explicitly designed for implementation in a real-world setting, ensuring that the time allocation for participants and facilitators (the party responsible for conducting the PL-BCT) remained reasonable in most contexts.

The BCT components were developed after identifying and coding the BCTs from previous interventional studies that contain behavioral components and result in positive effects on one or more adherence domains of hemodialysis patients toward their therapeutic regimen (dialysis program, medications, diet, and fluid)29,30,31,32.

A team consisting of one experienced senior nephrologist from the center, one experienced senior nurse from the same center, and two clinical pharmacists (authors) was formed. The team has undergone two rounds of discussion to finalize the list of BCTs, and 13 BCTs were utilized. The consensus process was an integral part of finalizing the intervention:

-

1.

Formation of the expert group The team was composed of a senior nephrologist, a seasoned nurse from the center, and two clinical pharmacists (the authors). This diverse group was deliberately selected to combine clinical expertise with practical experience in patient care and medication management within a hemodialysis setting.

-

2.

Round one—initial identification and review The first round involved a comprehensive review of the literature on behavioral interventions in hemodialysis care. The authors contributed potential behavior change techniques (BCTs) that had been previously used in related studies. Then the team debated the relevance and feasibility of each candidate BCT, considering factors such as the specific adherence challenges in hemodialysis patients (for example, issues related to attending dialysis sessions, medication, dietary, and fluid regimes) and the practical aspects of delivering the intervention in a busy clinical environment. Furthermore, the team reviewed the Behavior Change Technique (BCT) taxonomy version 1 for potential BCTs that could be beneficial for hemodialysis patients, which may have been used but not precisely prescribed in the context of previous literature.

-

3.

Round two – refinement and consensus In the second round, the initial list of BCTs was refined based on group discussions. The experts critically evaluated which BCTs could be most effectively delivered within the study’s context. The discussion focused on:

-

Relevance Ensuring that each selected BCT addressed at least one key domain of adherence relevant to hemodialysis patients.

-

Feasibility Confirming that the techniques could be easily administered (mostly verbally) during routine dialysis sessions without major disruption.

-

Standardization Deciding on the mode of delivery for each BCT. For instance, while most BCTs were delivered verbally, the self-monitoring of behavior component was provided as a paper-based chart, and instructions for performing the behavior were given as printed materials augmented with verbal explanations.

-

-

4.

Through these rounds of discussion, the team reached a unanimous consensus on incorporating 13 BCTs into the intervention.

-

5.

Outcome of the consensus exercise This consensus exercise ensured that the final list of techniques was carefully curated and contextually appropriate for the target population. It also added credibility to the intervention design by documenting a structured and systematic process that combined evidence-based insights with practical clinical experience.

Most of the BCTs were administered verbally, except for self-monitoring of behavior BCT, which was given in the format of a paper-based chart to be used by the patients, and instructions on how to perform the behavioral BCT, which were given in the form of printed materials with verbal instructions, as seen in Table 1.

A preliminary trial involving 12 participants was conducted prior to the main study to refine processes, enhance feasibility, and ensure the researchers’ competence and adherence. The patients involved in this preliminary trial were not part of the main randomized controlled trial. They were a separate group used solely for the purpose of refining the study protocol.

Implementation

The intervention was conducted in Arabic for all patients; the first author was responsible for conducting the behavioral sessions (a clinical pharmacist trained to use BCTTv1 taxonomy, with at least 5 years of experience).

The intervention was integrated into the patients’ regular dialysis sessions and delivered as a weekly session over two weeks. The first session lasted approximately 30–45 mins, while the second session lasted about 20–30 mins.

In the study, the usual care (UC) group did not receive any contact or behavioral intervention from the clinical pharmacist who delivered the PL-BCT intervention. Instead, they received the standard care provided at the dialysis center.

Usual care

The usual care group received the usual care offered by the center to all patients, which included printed, paper-based, and verbal instructions. The written material included knowledge about diet recommendations for dialysis patients based on the National Kidney Foundation recommendations45. The physician provided Verbal instructions, including information regarding their medications, dialysis, diet, and fluid intake based on their condition and monthly lab results. Medications are provided to all patients at no cost, and pharmacists offer instructions on their use.

Outcomes

Measurements were taken at baseline (before the first intervention session) and then four weeks after the intervention was completed.

The primary outcome was self-reported adherence using ESRD-AQ scores28. The Arabic version of the ESRD-AQ was used in the current study46, and this Arabic version was used effectively in a cross-sectional study performed previously in Iraq (Supplementary file 1)14. In the current study, we reported only the adherence aspect of the ESRD-AQ score, which involved questions numbers: 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 26, 27, 28, 31, and 46. Secondary outcomes included clinical indices, such as serum potassium level (K), serum phosphate level (PO4), hemoglobin (Hb), and IDWG.

The ESRD-AQ is a comprehensive tool that records critical elements of patients’ treatment histories, including self-reported treatment adherence (such as HD attendance, prescriptions, fluid restrictions, and dietary recommendations), perceptions regarding adherence behaviors, and justifications for non-adherence. ESRD-AQ consists of 46 questions, with scores ranging from 0 to 1200, with higher scores indicating better adherence. Scores are divided into three ranges to identify adherence behavior (good adherence scores range between 1000 and 1200, moderate adherence scores range between 700 and 999, and poor adherence scores are less than 700). The scores were distributed over the four dimensions as follows: adherence to HD sessions (scores 0–600), adherence to dietary recommendations (scores 0–200), adherence to medications (scores 0–200), and adherence to fluid restriction (scores 0–200)28.

Patients’ demographic data was retrieved from patients’ medical charts and directly from the patients. The data included patients’ age, sex, dialysis duration, educational level, cause of kidney disease, frequency of dialysis sessions per week, number of medications, and presence of other chronic diseases.

The IDWG is a measure of adherence to fluid restrictions in hemodialysis40. The IDWG was calculated as the pre-dialysis weight before HD treatment, minus the prior session post-dialysis weight; the IDWG was averaged for measurement of the number of hemodialysis sessions per week for four weeks47. Biochemical data were collected through regularly scheduled blood tests offered by the center.

Randomization and blinding

To minimize contamination (interaction among members of the study groups), a cluster randomization design was adopted; the unit of randomization was the dialysis shift, using computerized randomization (1:1 allocation ratio) using the online software Research Randomize. Allocation of randomization was concealed from study participants until baseline assessment was completed34. Each shift was randomly assigned to a PL-BCT (intervention group) or a usual care group.

Due to the behavioral nature of the intervention, neither the researcher conducting the intervention nor the participants could be blinded to their assignment to either the intervention group or the usual care group.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the College of Pharmacy, University of Baghdad, with approval number RECAUCP8720246, dated July 8, 2023. Written informed consent was obtained from study participants. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The authors adhere to the CONSORT 2010 statement in reporting the study48.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was calculated using GPower 3.1.9.449,50. Using a t-test family with a power of 80%, an alpha of 0.05, and an effect size of 0.6, the calculated sample size was 72 total participants, with 36 patients in each group.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10.3 and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 21.0. The Anderson–Darling test of normality was used to assess the adherence of continuous variables to normality. An Independent t-test was used to assess the differences in means between interventions (the Mann–Whitney U test was used instead if data did not follow normal distribution). A paired t-test was used to assess the change between baseline and after one month of follow-up for each group (the Wilcoxon rank test was used if data did not follow normal distribution). Ordinal logistic regression analysis was used to assess the effect of the intervention on adherence levels (dependent parameters, which have three levels: good, moderate, and poor adherence).

For the multivariate analysis, we evaluated the intervention effect using three successive models:

-

Model 1: Adjusted for sociodemographic variables including age, sex, marital status, education, and weight.

-

Model 2: In addition to the adjustments in Model 1, this model also controlled dialysis-related factors such as co-morbid disease presence, dialysis duration, number of sessions per week, and the number of medications.

-

Model 3: Further adjustment was made by controlling baseline clinical indicators, namely electrolytes, IDWG (intradialytic weight gain), and hemoglobin levels, in addition to the factors already excluded in Models 1 and 2.

The effect of the intervention was presented as an odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI), and all p-values were two-tailed with a significance level set at 0.05.

Results

Patient’s characteristics

There were no significant differences between the intervention and control groups at baseline in terms of demographic data, the number of prescribed medications, and patients’ clinical characteristics, as shown in Table 2.

Effect of intervention on adherence scores

At baseline, ESRD-AQ total scores exhibited no significant differences between the two groups. Regarding the domains of the ESRD-AQ score, all the domains showed no significant differences at baseline, except for the fluid restriction domain, which displayed a significant difference between groups at baseline, with the usual-care group showing significantly higher adherence to fluid restriction than the intervention group, as seen in Fig. 2 and Table 2.

Violin plot of the total adherence score and adherence domains classified according to the study groups. A Absence of dialysis sessions, B Shortening of dialysis sessions, C Time of shortening, D Adherence to dialysis program, E Adherence to medications, F Adherence to fluid restriction, G Adherence to dietary restrictions, H Total adherence.

After one month, the intervention significantly increased the adherence score, with total adherence increasing compared to usual care. Regarding ESRD-AQ domains, a significant improvement was observed in dietary recommendations and fluid restriction domains. Meanwhile, the dialysis program adherence domain, including absence from dialysis, frequency of shortening of the dialysis session, and shortening of the dialysis session, showed no statistically significant differences. In addition, the medication adherence domain showed no significant difference, as seen in Fig. 2 and Table 2.

At baseline, there was no significant difference in adherence levels between the groups with poor and moderate adherence. After one month of follow-up, there was a significant increase in the rate of good adherence levels in the PL-BCT group compared to usual care (42.1% vs. 14.7%), as seen in Table 3. There were no adverse events or side effects associated with the intervention.

Clinical indices

At baseline, Table 3 shows no significant differences between groups in clinical indices, including serum potassium, total calcium, phosphate, hemoglobin levels, and IDWG.

After one month, serum phosphate levels and IDWG in the intervention group significantly declined compared to the usual-care group. Meanwhile, serum potassium and total calcium levels did not exhibit significant differences, as seen in Table 4.

The change in clinical indices after a month of follow-up was assessed to examine the effect of the intervention. Figure 3 shows that both serum phosphate levels and the IDWG value significantly declined in the PL-BCT compared to usual care, while the other parameters did not show significant differences.

Relationship between intervention and adherence level using multivariate analysis

In the unadjusted analysis of the relationship between good adherence and the intervention, there was a 4.592-fold increase in the odds of achieving good adherence in the PL-BCT group compared to usual care. This strong association was maintained in the multivariate analysis, in which the model was adjusted for patients’ sociodemographic characteristics, disease characteristics, dialysis-related factors, and clinical indices; this indicates that PL-BCT interventions independently predict good adherence after adjusting for all possible confounders, as shown in Table 5.

Discussion

This study reported the results of a cluster-randomized controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of pharmacist-led behavioral interventions in enhancing adherence among hemodialysis patients. It demonstrated that a pharmacist-led behavioral intervention using clearly identified BCTs based on the BCTTv1 could substantially improve total adherence to the complex therapeutic regimen recommended for hemodialysis patients. In the current study, the utilized PL-BCT intervention improved dialysis patients’ adherence by 4.5-fold compared to usual care.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the positive impact of behavior-based interventions on the adherence of hemodialysis patients26,30,51. In one study, the authors examined the impact of the health contract intervention based on the goal attainment theory to enhance hemodialysis patients’ diet, fluid, and medication adherence29. The intervention included a formal introduction to the program, mutual goal setting, contracting, and re-contracting to support self-care behavior reinforced through praise, encouragement, and support, resulting in a partially positive result on the self-care behavior and clinical indices of renal dialysis patients in Korea29.

Similarly, a previous study employed an interactive and targeted self-management training program based on problem-solving principles and social learning theory to enhance fluid, dietary, and medication adherence, as well as clinical markers, among patients undergoing hemodialysis. It reported a significant improvement in self-reported adherence, IDWG, phosphate, and potassium concentration at different follow-up points34. Another study reported significant differences in dietary and fluid adherence and some biomedical markers among Iranian hemodialysis patients after two months of using Benson’s relaxation technique31.

In the Griva et al. (2018) study, the study demonstrated that structured self-management interventions, based on behavioral strategies similar to our BCTs, significantly improved adherence and clinical outcomes among hemodialysis patients30. A meta-analysis, which included several international studies, found that adherence enhancement programs significantly improved patient outcomes. The review highlights the effectiveness of interventions incorporating BCT elements, despite variations in geographical and clinical contexts51. Another study confirmed that pharmacist-led interventions that include elements of behavioral change—such as structured counselling and personalized education—can significantly improve adherence in hemodialysis settings26. These positive results reported in previous studies and the current research may stem from the presence of several mutual BCTs underlying the earlier interventions. These BCTs were identified, successfully implemented, and assessed in the current study, providing a precise context for an intervention model that can be re-implemented effectively.

In contrast, previous work found no significant impact of self-regulation theory on improving fluid restriction adherence in patients with severe chronic kidney disease undergoing hemodialysis52. This difference may be due to the adopted framework, which focused on self-monitoring, self-evaluation, and self-reinforcement. Another possible reason could be the variations in patient characteristics and the number of weekly dialysis sessions.

We also believe that our study provides privileged effectiveness due to the following features: Enhanced Tailoring of the Intervention: Unlike previous studies that may have implemented more generic or “one-size-fits-all” approaches, our intervention was specifically designed using the BCT taxonomy tailored to the unique needs of our hemodialysis patients. For instance, several interventional behavioral change theory-based interventions were developed based on a theory designed for general patients, rather than for specific conditions such as hemodialysis patients. Meanwhile, the use of a flexible method, such as the BCT Taxonomy, to build the intervention allows for the review of BCTs and the decision on which BCTs would benefit the dialysis population more, as done in this study. This customization has likely contributed to improved effectiveness. Methodological Rigor and Multi-Faceted Adjustments: We applied robust multivariate models that controlled sociodemographic, dialysis-related, and clinical factors. This sequential adjustment enhances the validity of our findings, even when compared to earlier studies that may not have comprehensively accounted for potential confounders.

Effect of the BCT intervention on individual adherence domains

This trial reported a remarkable improvement in adherence to fluid and dietary restrictions. These results align with the findings of several studies29,53,54,55. However, in a before-after pilot study32 comprising rational emotive therapy, no significant improvements were reported in fluid restriction after three months of follow-up, with a substantial rise in other adherence parameters, including dialysis attendance, shortening of dialysis, and serum phosphate. This variation may stem from the differences in study design and sample size.

This study observed a baseline between-groups gap in fluid restriction adherence scores, reporting significantly higher baseline scores in the usual care group than the PL-BCT group, highlighting a pre-existing challenge. Despite this, the PL-BCT group showed a significant improvement in this domain compared to the usual care group at follow-up, suggesting that the PL-BCT intervention effectively addressed this initial gap and facilitated better adherence to this behavior.

Notably, there were no significant changes in medication adherence and dialysis program scores, likely because both groups started with high baseline adherence; this may be explained by the fact that medications are provided free of charge—overcoming the financial burden that typically hinders adherence—and by the immediate sense of well-being patients experience after a dialysis session, which reinforces their adherence. A study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, demonstrated that the economic burden is a significant barrier to medication adherence among patients undergoing hemodialysis. This study found that financial constraints negatively impact adherence, and overcoming them, for example, by providing free medication, contributes to higher adherence levels56. Similar findings were reported in a previous study conducted in China, which noted no significant differences in dialysis adherence between groups after a disease-management program led by a healthcare professional to support hemodialysis patients’ health and adherence57. This may warrant further studies to identify barriers and facilitators for dialysis program adherence.

Effect of the BCT intervention on clinical indices

The study results indicate a substantial decline in serum phosphate levels and IDWG. This finding is relevant to improving ESRD-AQ scores regarding fluid and dietary management. In a world where more patients achieve better control over serum phosphate and IDWG, we would expect to see a significant reduction in hospitalization rates, improved quality of life, and potentially lower healthcare costs due to fewer complications. This is particularly relevant in settings with high rates of cardiovascular disease among dialysis patients, where improved adherence to dietary and fluid restrictions can have a direct impact on survival and overall health. These findings align with other researchers’ work, who found that behavioral interventions led to a significant decline in IDWG and/or serum phosphate levels in hemodialysis patients36,37,53,58. However, this result is incompatible with another study, observing no improvement in phosphorus levels or IDWG after a self-monitoring behavioral intervention59. Similarly, another study reported no significant changes in serum phosphate levels using a self-efficacy behavioral intervention60. This difference may be attributed to the theoretical models of interventions, which might include a limited set of BCTs. A reduction in serum phosphate is critically important because hyperphosphatemia in hemodialysis patients is associated with severe complications, including vascular calcification, bone mineral disorders, and an increased risk of cardiovascular events61,62,63,64. Similarly, lowering IDWG helps reduce fluid overload, which improves cardiovascular stability, minimizes intradialytic complications, and generally enhances patient well-being. In essence, these improvements contribute to a decrease in morbidity and mortality, key outcomes sought in dialysis care65,66,67.

Meanwhile, serum potassium levels exhibited a modest decline between the two groups, suggesting that dietary adherence to phosphate restrictions is higher than adherence to potassium restrictions. This result is in line with the findings of a previous study, which observed no improvement in potassium levels when utilizing self-efficacy theory. However, this finding is incompatible with another study, which found that the proportion of Chinese dialysis patients who are compliant with potassium restriction is higher than that with phosphate restrictions68. This observed difference may be attributable to the nature of Arabian cuisine, particularly Iraqi dishes, in which some beans (e.g., white beans, fava beans, and lentils), vegetables (potatoes, tomatoes), and fruits (dates) are highly consumed, and all contain considerable amounts of potassium.

The study results showed no remarkable differences in serum total calcium between the two groups. In distinction, the usual-care group demonstrated a significant increase in calcium levels compared to baseline, which may warrant further investigations. Similar findings were reported in a previous study assessing the effectiveness of motivational interviewing in promoting adherence and well-being among Spanish hemodialysis patients. It reported a significant decline in phosphate levels, while no substantial changes were noted in calcium and potassium concentrations69.

The current study observed no substantial change in serum hemoglobin levels. This result may be attributed to the center’s depletion of the anemia medication (erythropoietin injections) during the study period and its limited availability in community pharmacies due to new medication registration policies implemented by the Ministry of Health at that time.

Although our research was conducted in a specific context, the underlying principles of behavioral change and adherence improvement are broadly applicable. Many dialysis centers worldwide face similar challenges with non-adherence to complex regimens. Our intervention model—based on tailored behavior change techniques that address specific adherence barriers—could be adapted to different healthcare systems, especially those in low-resource settings or where free medication programs alleviate financial burdens70,71,72. The improvements observed in our clinical indices support the idea that structured, personalized interventions can yield tangible health benefits across diverse settings.

By demonstrating that targeted behavioral interventions can lead to measurable improvements in both objective clinical markers and self-reported adherence, our study reinforces the importance of integrating such approaches into routine patient management. Enhanced adherence not only improves clinical outcomes but also contributes to long-term changes in patient behavior that could alleviate the burden on healthcare systems.

Conclusion

Hemodialysis patients worldwide face a substantial burden in their adherence to a complex therapeutic regimen. In developing countries, this population is weighed more by their disease due to inherent healthcare insufficiencies, financial costs, and inadequacies in social support and services73. Therefore, any step to maximize the disease-related needs and experiences of hemodialysis patients might positively impact their overall well-being and health. This study provides potential evidence that a specific identified BCT-based intervention can significantly enhance adherence to the complex therapeutic regimens of hemodialysis patients, particularly in terms of dietary and fluid restrictions. This study’s findings suggest that BCTs are valuable to patient care. These findings contribute to a growing body of literature supporting the effectiveness of behavioral interventions in managing chronic conditions, such as ESRD.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/14548056, reference number 14548056.

References

Lv, J. C. & Zhang, L. X. Prevalence and disease burden of chronic kidney disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1165, 3–15 (2019).

Rodger, R. S. C. Approach to the management of end-stage renal disease. Clin. Med. 12(5), 472–475 (2012).

De Rosa, S., Samoni, S., Villa, G. & Ronco, C. Management of chronic kidney disease patients in the intensive care unit: Mixing acute and chronic illness. Blood Purif. 43(1–3), 151–162 (2017).

Levey, A. S. et al. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 39, i-ii+S1-S266 (2002).

Fleming, G. M. Renal replacement therapy review: Past, present and future. Organogenesis 7(1), 2–12 (2011).

Sultan, B. O., Fouad, A. M. & Zaki, H. M. Adherence to hemodialysis and medical regimens among patients with end-stage renal disease during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 23(1), 138 (2022).

Leggat, J. E. Jr. et al. Noncompliance in hemodialysis: Predictors and survival analysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 32(1), 139–145 (1998).

Denhaerynck, K. et al. Prevalence and consequences of nonadherence to hemodialysis regimens. Am. J. Crit. Care. 16(3), 222–235 (2007).

Obialo, C. I., Hunt, W. C., Bashir, K. & Zager, P. G. Relationship of missed and shortened hemodialysis treatments to hospitalization and mortality: Observations from a US dialysis network. Clin. Kidney J. 5(4), 315–319 (2012).

Saran, R. et al. Nonadherence in hemodialysis: Associations with mortality, hospitalization, and practice patterns in the DOPPS. Kidney Int. 64(1), 254–262 (2003).

Schmid, H., Hartmann, B. & Schiffl, H. Adherence to prescribed oral medication in adult patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis: A critical review of the literature. Eur. J. Med. Res. 14(5), 185–190 (2009).

Vaiciuniene, R., Kuzminskis, V., Ziginskiene, E., Skarupskiene, I. & Bumblyte, I. A. Adherence to treatment and hospitalization risk in hemodialysis patients. J. Nephrol. 25(5), 672–678 (2012).

Magnard, J., Deschamps, T., Cornu, C., Paris, A. & Hristea, D. Effects of a six-month intradialytic physical ACTIvity program and adequate NUTritional support on protein-energy wasting, physical functioning and quality of life in chronic hemodialysis patients: ACTINUT study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Nephrol. 14, 259 (2013).

Abdul-Jabbar, M. A. & Kadhim, D. J. Adherence to different treatment modalities among patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Iraqi J. Pharm. Sci. 31(1), 95–101 (2022).

Athbi, H. Compliance behaviors among patients undergoing hemodialysis therapy in Holy Kerbala/Iraq. Kerbala J. Pharm. Sci. 9(1), 78–90 (2015).

Murali, K. M. et al. Strategies to improve dietary, fluid, dialysis or medication adherence in patients with end stage kidney disease on dialysis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized intervention trials. PLoS ONE 14(1), e0211479 (2019).

Taylor, K. S. et al. Material need insecurities among people on hemodialysis: Burden, sociodemographic risk factors, and associations with substance use. Kidney360 4(11), 1590–1597 (2023).

Michie, S. et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 46(1), 81–95 (2013).

Rahayu, S. A., Widianto, S., Defi, I. R. & Abdulah, R. Role of pharmacists in the interprofessional care team for patients with chronic diseases. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 14, 1701–1710 (2021).

Abed, T. S., Rasheed, J. I. & Fawzi, H. A. Dosing of erythropoietin stimulating agents in patients on hemodialysis: A single-center study. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 10(11), 2778–2783 (2019).

Al-Radeef, M. Y., Fawzi, H. A. & Allawi, A. A. ACE gene polymorphism and its association with serum erythropoietin and hemoglobin in Iraqi hemodialysis patients. Appl. Clin. Genet. 12, 107–112 (2019).

Al-Radeef, M. Y., Allawi, A. A. D. & Fawzi, H. A. Interleukin-6 gene polymorphisms and serum erythropoietin and hemoglobin in hemodialysis Iraqi patients. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transpl. 29(5), 1042–1049 (2018).

Liddelow, C., Mullan, B. A., Breare, H., Sim, T. F. & Haywood, D. A call for action: Educating pharmacists and pharmacy students in behaviour change techniques. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 11, 100287 (2023).

Skoutakis, V. A., Acchiardo, S. R., Martinez, D. R., Lorisch, D. & Wood, G. C. Role-effectiveness of the pharmacist in the treatment of hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Hosp. Pharm. 35(1), 62–65 (1978).

Ismail, S. et al. Patient-centered pharmacist care in the hemodialysis unit: A quasi-experimental interrupted time series study. BMC Nephrol. 20(1), 408 (2019).

Alshogran, O. Y., Hajjar, M. H., Muflih, S. M. & Alzoubi, K. H. The role of clinical pharmacist in enhancing hemodialysis patients’ adherence and clinical outcomes: A randomized-controlled study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 44(5), 1169–1178 (2022).

Daifi, C., Feldpausch, B., Roa, P.-A. & Yee, J. Implementation of a clinical pharmacist in a hemodialysis facility: A quality improvement report. Kidney Med. 3(2), 241-247.e241 (2021).

Kim, Y., Evangelista, L. S., Phillips, L. R., Pavlish, C. & Kopple, J. D. The end-stage renal disease adherence questionnaire (ESRD-AQ): Testing the psychometric properties in patients receiving in-center hemodialysis. Nephrol. Nurs. J. 37(4), 377–393 (2010).

Cho, M.-K. Effect of health contract intervention on renal dialysis patients in Korea. Nurs. Health Sci. 15(1), 86–93 (2013).

Griva, K. et al. Hemodialysis self-management intervention randomized trial (HED-SMART): A practical low-intensity intervention to improve adherence and clinical markers in patients receiving hemodialysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 71(3), 371–381 (2018).

Pasyar, N., Rambod, M., Sharif, F., Rafii, F. & Pourali-Mohammadi, N. Improving adherence and biomedical markers in hemodialysis patients: The effects of relaxation therapy. Complement. Ther. Med. 23(1), 38–45 (2015).

Russell, C. L. et al. Motivational interviewing in dialysis adherence study (MIDAS). Nephrol. Nurs. J.: J. Am. Nephrol. Nurses’ Assoc. 38(3), 229–236 (2011).

Cummings, K. M., Becker, M. H., Kirscht, J. P. & Levin, N. W. Intervention strategies to improve compliance with medical regimens by ambulatory hemodialysis patients. J. Behav. Med. 4(1), 111–127 (1981).

Griva, K. et al. Hemodialysis self-management intervention randomized trial (HED-SMART): A practical low-intensity intervention to improve adherence and clinical markers in patients receiving hemodialysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 71(3), 371–381 (2018).

Forni Ogna, V. et al. Clinical benefits of an adherence monitoring program in the management of secondary hyperparathyroidism with cinacalcet: Results of a prospective randomized controlled study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 104892 (2013).

Karavetian, M. & Ghaddar, S. Nutritional education for the management of osteodystrophy (nemo) in patients on haemodialysis: A randomised controlled trial. J. Ren. Care. 39(1), 19–30 (2013).

Tsay, S. L. Self-efficacy training for patients with end-stage renal disease. J. Adv. Nurs. 43(4), 370–375 (2003).

Kauric-Klein, Z. Improving blood pressure control in end stage renal disease through a supportive educative nursing intervention. Nephrol. Nurs. J. 39(3), 217–228 (2012).

Park, O. L. & Kim, S. R. Integrated self-management program effects on hemodialysis patients: A quasi-experimental study. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 16(4), 396–406 (2019).

Cukor, D. et al. Psychosocial intervention improves depression, quality of life, and fluid adherence in hemodialysis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 25(1), 196–206 (2014).

Sullivan, C. et al. Effect of food additives on hyperphosphatemia among patients with end-stage renal disease: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 301(6), 629–635 (2009).

Rodrigues, P. A., Saji, A., Raj, P. & Sony, S. Impact of pharmacist intervention on medication knowledge and adherence in hemodialysis patients. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 11, 131–133 (2019).

Zhianfar, L., Nadrian, H., Asghari Jafarabadi, M., Espahbodi, F. & Shaghaghi, A. Effectiveness of a multifaceted educational intervention to enhance therapeutic regimen adherence and quality of life amongst Iranian hemodialysis patients: A randomized controlled trial (MEITRA study). J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 13, 361–372 (2020).

Wileman, V. et al. Evidence of improved fluid management in patients receiving haemodialysis following a self-affirmation theory-based intervention: A randomised controlled trial. Psychol. Health 31(1), 100–114 (2016).

National Kidney Foundation. Nutrition and Kidney Failure. https://www.kidney.org/kidney-topics/nutrition-and-kidney-failure. [Accessed January 2024]. (2024).

Naalweh, K. S. et al. Treatment adherence and perception in patients on maintenance hemodialysis: A cross - sectional study from Palestine. BMC Nephrol. 18(1), 178 (2017).

Jalalzadeh, M. et al. Consequences of interdialytic weight gain among hemodialysis patients. Cureus 13(5), e15013 (2021).

Boutron, I., Altman, D. G., Moher, D., Schulz, K. F. & Ravaud, P. CONSORT statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: A 2017 update and a CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic trial abstracts. Ann. Intern. Med. 167(1), 40–47 (2017).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39(2), 175–191 (2007).

Charan, J. & Kantharia, N. D. How to calculate sample size in animal studies?. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 4(4), 303–306 (2013).

Kim, H., Jeong, I. S. & Cho, M.-K. Effect of treatment adherence improvement program in hemodialysis patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(18), 11657 (2022).

Howren, M. B. et al. Effect of a behavioral self-regulation intervention on patient adherence to fluid-intake restrictions in hemodialysis: A randomized controlled trial. Ann. Behav. Med. 50(2), 167–176 (2016).

Wileman, V. et al. Evidence of improved fluid management in patients receiving haemodialysis following a self-affirmation theory-based intervention: A randomised controlled trial. Psychol. Health. 31(1), 100–114 (2016).

Molaison, E. F. & Yadrick, M. K. Stages of change and fluid intake in dialysis patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 49(1), 5–12 (2003).

Sagawa, M., Oka, M., Chaboyer, W., Satoh, W. & Yamaguchi, M. Cognitive behavioral therapy for fluid control in hemodialysis patients. Nephrol. Nurs. J. 28(1), 37–40 (2001).

Baye, T. A. et al. The economic burden of hemodialysis and associated factors among patients in private and public health facilities: A cross-sectional study in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 22(1), 25 (2024).

Wong, F. K. Y., Chow, S. K. Y. & Chan, T. M. F. Evaluation of a nurse-led disease management programme for chronic kidney disease: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 47(3), 268–278 (2010).

Wileman, V. et al. Evidence that self-affirmation improves phosphate control in hemodialysis patients: A pilot cluster randomized controlled trial. Ann. Behav. Med. 48(2), 275–281 (2014).

Tanner, J. L. et al. The effect of a self-monitoring tool on self-efficacy, health beliefs, and adherence in patients receiving hemodialysis. J. Ren. Nutr. 8(4), 203–211 (1998).

Yun, K. S. & Choi, J. Y. Effects of dietary program based on self-efficacy theory on dietary adherence, physical indices and quality of life for hemodialysis patients. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 46(4), 598–609 (2016).

Goodman, W. G. et al. Coronary-artery calcification in young adults with end-stage renal disease who are undergoing dialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 342(20), 1478–1483 (2000).

KDIGO 2017. Clinical practice guideline update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int. Suppl. 7(1), 1–59 (2017).

Block, G. A., Hulbert-Shearon, T. E., Levin, N. W. & Port, F. K. Association of serum phosphorus and calcium x phosphate product with mortality risk in chronic hemodialysis patients: A national study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 31(4), 607–617 (1998).

Kestenbaum, B. et al. Serum phosphate levels and mortality risk among people with chronic kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 16(2), 520–528 (2005).

Bossola, M., Mariani, I., Strizzi, C. T., Piccinni, C. P. & Di Stasio, E. How to limit interdialytic weight gain in patients on maintenance hemodialysis: State of the art and perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 14(6), 1846 (2025).

Lew, S. Q. et al. The role of intra- and interdialytic sodium balance and restriction in dialysis therapies. Front. Med. 10, 1268319 (2023).

Choi, S. H. et al. Prognostic implication of interdialytic fluid retention during the beginning period in incident hemodialysis patients. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 226(2), 109–115 (2012).

Lee, S. H. & Molassiotis, A. Dietary and fluid compliance in Chinese hemodialysis patients. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 39(7), 695–704 (2002).

García-Llana, H., Remor, E., del Peso, G., Celadilla, O. & Selgas, R. Motivational interviewing promotes adherence and improves wellbeing in pre-dialysis patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 21(1), 103–115 (2014).

Mirzaei-Alavijeh, M. et al. Determinants of medication adherence in hemodialysis patients: A cross-sectional study based on capability-opportunity-motivation and behavior model. BMC Nephrol. 24(1), 174 (2023).

Ekholm, M. et al. Behavioral interventions targeting treatment adherence in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 366, 117594 (2025).

Murali, K. M. & Lonergan, M. Breaking the adherence barriers: Strategies to improve treatment adherence in dialysis patients. Semin. Dial. 33(6), 475–485 (2020).

Wetmore, J. B. & Collins, A. J. Meeting the world’s need for maintenance dialysis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26(11), 2601–2603 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors are extremely grateful to the participants of the study and the College of Pharmacy, University of Baghdad, for all their support.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding in any form.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, Manuscript preparation, Al-Hamadani FY, Brown S, Delyth H., James DH, and Ansaf TS. Supervision, Al-Hamadani FY. Statistical analysis and review of final results, Ansaf TS. Manuscript review and editing, Al-Hamadani FY, Brown S, Delyth H., James DH, and Ansaf TS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors of this work have nothing to disclose.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval has been obtained from the College of Pharmacy, University of Baghdad, Research Ethics Committee (RECAUCP8720246, 08/07/2023).

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ansaf, T.S., Al-Hamadani, F.Y., Brown, S. et al. Pharmacist-led behavioral change intervention improves adherence and clinical outcomes among hemodialysis patients. Sci Rep 15, 33661 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18082-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18082-y